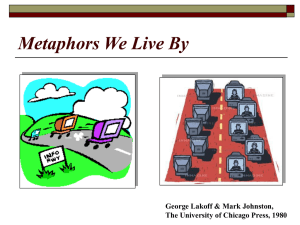

Chapter 1-2 Concepts We Live By The chapter delves into the pervasive nature of metaphor in everyday life, extending beyond language to influence thought and actions. It highlights how our ordinary conceptual system is fundamentally metaphorical, shaping not just our intellect but also our daily functions. By analyzing language, the study reveals how metaphors, like ARGUMENT IS WAR, structure how we perceive, think, and behave, illustrating how metaphorical concepts profoundly impact our everyday realities. This exploration sheds light on the profound influence of metaphorical thinking on our cognition and behavior. The Systematicity of Metaphorical Concepts Arguments often follow predictable patterns, influenced by how we conceptualize them in terms of battle. This systematic influence shapes the structure of arguments and the language used to describe them. Patterns in arguments are partially shaped by the systematic way in which we view arguments as battles. The language we use in arguments reflects this systematic conceptualization of arguments as battles. Expressions like "attack a position," "strategy," and "win" form a systematic way of discussing arguing. These expressions have specific meanings in the context of arguments because of the underlying conceptualization of arguments as battles. Given this systematic relationship between metaphorical expressions and concepts, studying linguistic expressions can help uncover the metaphorical nature of our everyday activities. Metaphorical expressions in language are intricately linked to metaphorical concepts in a systematic manner. By analyzing metaphorical linguistic expressions, we can better understand the metaphorical concepts that underpin our daily activities. For a deeper insight into how metaphorical language reveals our conceptualizations, consider the Metaphor "time is money" as seen in contemporary English. In our culture, time is perceived as a precious resource, closely associated with money and productivity. This metaphorical association stems from the modern association of work with time and the quantification of time. We see this metaphor reflected in various aspects of our lives, from hourly wages to yearly budgets and interest on loans. Such metaphors have emerged in industrialized societies and greatly influence how we engage in everyday tasks. The systematicity of metaphorical concepts is evident in how we treat time as a valuable commodity that can be spent, budgeted, or saved. Concepts like "time is money", "time is a limited resource", and "time is a valuable commodity" are all metaphorical. These metaphors are rooted in our cultural experiences with money and resources. While this conceptualization of time is specific to certain cultures, in our society, time is thought of in terms of money, limited resources, and valuable commodities. The metaphorical concepts form a coherent system based on relationships of entailment, where one concept leads to another in a structured manner. Metaphorical Systematicity: Highlighting and Hiding The authors explain how metaphorical concepts can both highlight and hide aspects of our understanding by focusing on one aspect while obscuring others: Metaphors allow us to grasp one facet of a concept by likening it to another, such as understanding arguing through the lens of battle. However, this emphasis on one aspect (like the competitive nature of arguing) can lead us to overlook other dimensions of the concept that do not align with the metaphor. In the heat of an argument, the cooperative elements can be overshadowed by the confrontational nature, missing the collaborative essence of debating. The "conduit metaphor" in language, where ideas are treated as objects to be encased in words and transmitted, can mask the nuanced interpersonal and contextual complexities of communication. Despite being pervasive in language, these metaphors may conceal subtle layers of meaning and context, such as in unconventional expressions like "apple-juice seat" that are clear only within a specific context. The systematicity of metaphors in shaping our understanding has implications: The metaphorical structuring offers a partial, rather than complete, view of concepts; if it were total, one concept would be synonymous with the other. Metaphorical concepts extend beyond literal interpretations into figurative and fanciful realms, allowing creative and colorful expressions. While metaphors partially shape concepts, they can be creatively extended within certain bounds, enabling diverse and imaginative ways of thinking and communicating. Orientational Metaphors The section introduces orientational metaphors, which differ from structural metaphors by organizing a system of concepts rather than structuring one concept in terms of another. These metaphors, often related to spatial orientation like up-down, in-out, and front-back, emerge from the physical functioning of our bodies in the environment. Definition: Orientational metaphors provide concepts with spatial orientation, for instance, associating "HAPPY" with "UP," leading to expressions like "I'm feeling up today." Basis: These metaphorical orientations are rooted in our physical and cultural experiences. While the physical oppositions are universal, cultural variations can alter the orientation metaphors. Cultural Variances: Different cultures may place the future in front or behind individuals, showcasing how cultural factors can influence spatial metaphors. Illustration: The section discusses up-down spatialization metaphors, notably studied by William Nagy, presenting examples like "His income fell last year" or "Turn the heat down." The explanations provided hint at how each metaphorical concept could have originated from a blend of physical and cultural encounters, offering plausible interpretations rather than definitive explanations. These metaphors often draw on everyday experiences such as increasing levels being equated with going up, exemplifying how our physical interactions shape metaphorical reasoning. FORESEEABLE FUTURE EVENTS ARE UP (and AHEAD) The discussion revolves around how events in the foreseeable future are perceived in terms of spatial metaphors. Here are the key points included: Spatial Metaphors: The metaphor of "UP (and AHEAD)" is used to depict future events. Directional Perception: The concept is explained through physical basis, where our eyes typically look in the direction of our movement, associating forward movement with events in the future. Object Perception: As an object approaches a person or vice versa, the object's perceived size changes. Due to the perception of the ground as stationary, the top part of the object seems to move upwards in the observer's field of vision, reinforcing the spatial metaphor of events moving "UP (and AHEAD)" in relation to time. HIGH STATUS IS UP; LOW STATUS IS DOWN The concept of status is metaphorically linked to spatial orientation - high status is associated with up, while low status is connected to down. This metaphor is reflected in everyday language expressions: "He has a lofty position." "She'll rise to the top." "He's climbing the ladder." "She fell in status." Social and Physical Basis: Status aligns with power - social power is likened to being up. Physical power is also correlated with up in this metaphorical conceptualization. GOOD IS UP; BAD IS DOWN Another metaphorical concept links positivity with up and negativity with down in our everyday language: "Things are looking up." "We hit a peak last year, but it's been downhill ever since." "Things are at an all-time low." "He does high-quality work." Physical Basis for Personal Well-being: Happiness, health, life, and control, which constitute well-being, are metaphorically associated with up. This conceptual metaphor suggests that what is good for a person is perceived as up. VIRTUE IS UP; DEPRAVITY IS DOWN In everyday language and thought, the metaphorical concept of VIRTUE IS UP; DEPRAVITY IS DOWN is commonly expressed through phrases like "high-minded," "upright," "low trick," or "falling into the abyss of depravity." The use of spatial metaphors to describe moral concepts is prevalent, where being virtuous is associated with being "up" and acting deceptively or immorally is linked to being "down." Key points included: Spatial Basis: Goodness and virtue are metaphorically linked to being "up," while depravity and immoral actions are associated with being "down." Social Aspect: The metaphor extends to a social level where acting virtuously aligns with the standards set by society or a person representing society. This alignment is crucial for maintaining social well-being. Cultural Influence: Since these metaphors are ingrained in culture, the perspective of the society or person in the metaphor holds significance in defining what is considered virtuous or depraved behavior. RATIONAL IS UP; EMOTIONAL IS DOWN The section discusses the metaphorical concept where rationality is associated with being "up" and emotions with being "down." Here are the key points included: The text describes scenarios where discussions are elevated or lowered based on the perceived level of rationality or emotion: "The discussion fell to the emotional level, but I raised it back up to the rational plane." "He couldn't rise above his emotions," indicating a hierarchy where rationality is superior to emotions. The cultural and physical basis for this metaphor is explained: In Western culture, humans see themselves as having control over nature based on their unique reasoning ability. This belief in control over the physical environment and other living beings contributes to the notion of "control is up," supporting the idea that humans are superior (man is up) and rationality is elevated. By portraying rationality as up and emotions as down, this metaphorical framework influences how individuals perceive, discuss, and navigate intellectual and emotional aspects of various situations. Conclusions The authors draw several key conclusions regarding metaphorical concepts based on spatialization: Fundamental concepts are predominantly organized using spatialization metaphors. Each spatialization metaphor exhibits internal systematicity, providing a coherent system of understanding. For instance, "happy is up" forms a cohesive system rather than isolated instances. Overall, there is external systematicity among various spatialization metaphors, ensuring coherence among them. Spatialization metaphors are not randomly assigned but rooted in physical and cultural experiences, forming the basis for understanding concepts. Multiple physical and social bases exist for metaphors, with coherence contributing to the selection of one over another. Some concepts are so inherently linked to spatialization that alternatives seem challenging to envision, such as the notion of "high status." Certain metaphors, like "happy is up," form part of conceptual systems and contribute to the meaning of the concept. Even seemingly purely intellectual concepts in scientific theories are often metaphorically based on physical or cultural references. The choice of spatialization metaphors is influenced by cultural coherence, making it challenging to separate the physical from the cultural basis of a metaphor. Experiential Bases of Metaphors The section highlights the importance of the experiential basis of metaphors in understanding their significance: Metaphors have distinct experiential foundations that shape their meanings differently. Different metaphors using the same concept, such as "up," can stem from varied experiential sources. The relationship between different metaphors and their experiential bases is crucial for understanding their intended meanings. Representations should ideally incorporate the experiential bases to better convey the connection between the metaphorical concepts. The authors stress the inseparability of metaphors from their experiential origins. Despite the significance of experiential bases, limited knowledge in this area hinders deeper exploration. The experiential basis is key in reconciling metaphors that may seem mismatched due to their diverse experiential origins. For instance, the metaphor "UNKNOWN IS UP; KNOWN IS DOWN" aligns with the experiential basis of "UNDERSTANDING IS GRASPING," where grasping and understanding are metaphorically linked. The coherence of certain metaphors, like "UNKNOWN IS UP," with specific experiential concepts may differ from other traditional metaphors like "GOOD IS UP" or "FINISHED IS UP." Metaphor and Cultural Coherence The section explores how fundamental cultural values align with metaphorical structures within a society: Cultural Values and Metaphors: Fundamental cultural values are coherent with metaphorical concepts within a culture. Values like "more is better," "bigger is better," and "the future will be better" align with the metaphorical structure where "more is up" and "good is up." Conversely, values like "less is better," "smaller is better," or "the future will be worse" are not coherent with these spatial metaphors. Embedded Values in Culture: Values like progress ("the future will be better") and careerism ("your status should be higher in the future") are deeply ingrained in society. These values correspond to spatialization metaphors like "the future is up" and "high status is up." Conflicts and Priorities: Conflicts may arise when different values prioritize aspects differently. Subcultures within a society may give varying priorities to values based on their beliefs and preferences. For example, conflicts can arise between purchasing decisions like buying a big car now or a smaller car with future implications. Cultural Variations: Different subcultures may prioritize values in unique ways, leading to contrasting behaviors and priorities. Groups like monastic orders may redefine mainstream values according to their beliefs, while still aligning with broader cultural metaphors. Individual and Group Coherence: Individual and group value systems are usually coherent with the major cultural metaphors. Personal priorities and definitions of virtues may vary but often align with overarching cultural orientations. Cultural Orientation Variability: Not all cultures prioritize spatial orientations like up-down equally. Different cultures may emphasize balance, centrality, activity, or passivity over traditional spatial metaphors. The section highlights how cultural values, priorities, and conflicts are intertwined with the metaphorical structures that shape societal norms and behaviors.