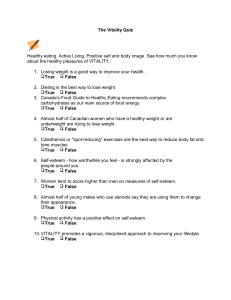

Journal of Organizational Behavior J. Organiz. Behav. 30, 785–804 (2009) Published online 11 November 2008 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com) DOI: 10.1002/job.571 Alive and creating: the mediating role of vitality and aliveness in the relationship between psychological safety and creative work involvement RONIT KARK1*,y AND ABRAHAM CARMELI2y 1 2 Summary Departments of Psychology and Sociology, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel Graduate School of Business Administration, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan, Israel Individual involvement in creative work is of crucial importance for organizations in a knowledge-based economy. This study examined how psychological safety induces feelings of vitality and how feelings of vitality impact one’s involvement in creative work. We examined these relationships among 128 part-time graduate students who held managerial and nonmanagerial position in their work organizations. The results suggest that employees’ sense of psychological safety is significantly associated with feelings of vitality (both collected at time 1), which, in turn, result in involvement in creative work (collected at time 2). We discuss the implications of these findings for both theory and practice. Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Introduction Research evidence suggests that employee creativity makes an important contribution to organizational innovation, effectiveness, and survival (Amabile, Conti, Coon, Lazenby, & Herron, 1996). Since creativity and creative involvement are valuable to organizations and often sought after, researchers have become increasingly interested in identifying conditions at both the organization and individual levels that influence employee creative behaviors (e.g., Oldham & Cummings, 1996; Perry-Smith, 2006; Tierney, Farmer, & Graen, 1999). One of these conditions is the work environment, which has mostly been studied in terms of support for creativity, the extent to which individuals are encouraged to engage in creative work or display creative behaviors (Amabile et al., 1996; Madjar, Oldham, & Pratt, 2002), or in terms of social networks (Perry-Smith, 2006; Perry-Smith & Shalley, 2003). Despite these inquiries into the role of social climate in fostering or impeding involvement in creative work or creative behaviors at work, we ‘‘know little about how the social context affects individual thinking when it comes to the generation of creative ideas or solutions as evidenced by the * Correspondence to: Ronit Kark, Departments of Psychology and Sociology, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel, 52900. E-mail: karkro@mail.biu.ac.il y The authors contributed equally to this paper. Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Received 20 February 2007 Revised 10 September 2008 Accepted 16 September 2008 R. KARK AND A. CARMELI relative creativity of work outputs’’ (Perry-Smith, 2006, p. 86). There is also limited knowledge on how the social context affects creative work involvement, which is defined as ‘‘as the extent to which an employee engages his or her time and effort resources in creative processes associated with work’’ (Carmeli & Schaubroeck, 2007, p. 36). In the current study, we focus on a specific aspect of the social context, psychological safety, defined as individuals’ perceptions of the consequences of taking interpersonal risks in their work environment (Edmondson, 1999, 2004; Kahn, 1990). We aim to understand how psychological safety facilitates employee involvement in creative work. This is of importance, since psychological safety is a fundamental characteristic of the work environment, which can influence individuals’ ability to feel secure and thus capable of learning, changing their behavior, and being engaged in their work (Edmondson, 2004). We argue that an individual’s perception of psychological safety can augment feelings of vitality, which, in turn, may result in involvement in creative work. In doing so, we expand our knowledge by linking psychological safety to affective experiences (i.e., vitality), and creative work involvement. In addition, emerging research on positive psychology (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000), positive organizational scholarship (Cameron, Dutton, & Quinn, 2003) and positive organizational behavior (Luthans, 2002a,b, 2003; Wright, 2003) has shifted the focus from studying conditions that account for deficiencies to better characterizing the conditions that account for positive experiences and states. A work environment that emphasizes positive work relationships is a central source of positive states and experiences such as satisfaction, enrichment, development, and growth (Dutton, 2003; Dutton & Heaphy, 2003, Quinn & Dutton, 2005). Quinn (2007) contends that ‘‘the higher quality of the connection between two people, . . .the more energy those people will feel’’ (p. 74). As such, work environments can be energizing and enriching and foster human thriving, development, and growth in the workplace (Spreitzer, Sutcliffe, Dutton, Sonenshein, & Grant, 2005). Despite this promising line of research, employee vitality, which is conceptualized as ‘‘a dynamic phenomenon, pertinent to both mental and physical aspects of functioning and thus refers to a person who is vital as energetic, feeling alive, and fully functioning’’ (Ryan & Bernstein, 2004, p. 274), has been the subject of limited studies in organizational settings. Furthermore, despite the considerable attention to the ways in which affect is related to creativity, there has only been meager progress in understanding the role of affect on creative involvement in the workplace (Amabile, Barsade, Mueller, & Staw, 2005). Our study addresses these theoretical and empirical issues by exploring the role of the affective state of vitality on creative work involvement. We propose and test a model in which vitality mediates the relationship between psychological safety and employees’ tendency to become involved in creative work. This study is a first attempt to examine the relationship between psychological safety, employees’ feelings of vitality, and creative work involvement. By analyzing the role of psychological safety in inducing feelings of vitality and enhancing the extent to which an individual is involved in creative work, we hope to contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the underlying processes of psychological safety and emotional influence (vitality), in order to promote employees’ emotional well-being and to improve the creative process and output at work. Theory and Hypotheses Individual involvement in creative work Creativity is generally defined as the production of novel, useful ideas or problem solutions (Amabile, 1983, 1996). This suggests that creativity may encompass the invention of new technologies or job Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 30, 785–804 (2009) DOI: 10.1002/job 10991379, 2009, 6, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/job.571 by Feng Chia University, Wiley Online Library on [16/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 786 787 procedures, creative directions in the process of decision making, creative solutions to business problems, and creative changes. Following Amabile’s (1983, 1996) definition, we conceptualize employee creativity as the production of ideas, products, or procedures that are novel or original, and potentially useful to the employing organization. This notion thus encompasses the process of idea generation, problem solving and the actual idea or solution (Amabile, 1983; Sternberg, 1988; Weisberg, 1988). Individual creative behaviors at work are essential for addressing new and changing demands in the workplace. Carmeli and Schaubroeck (2007) argued that although outcomes of the creative process are often studied (Amabile, 1988; Oldham & Cummings, 1996; Tierney et al., 1999), one of the key questions in creativity research relates to individuals’ motivation to become and remain creatively engaged at work (Amabile, 1998; Janssen, van de Vliert, & West, 2004; Scott & Bruce, 1994). In an attempt to expand this line of research, we focus on individual involvement in the creative process at work. Creative work involvement is distinct from creative performance. Creative work involvement refers to an employee’s engagement (in terms of time and effort) in creative processes associated with work (Carmeli & Schaubroeck, 2007, p. 36). As such, involvement manifests a person’s subjective assessment of the degree to which he or she is engaged in creative tasks. In contrast, creative performance refers to the outcome of this involvement. This distinction is consistent with research on work and job involvement where both are considered as forms of work commitment with specific implications for work outcomes (Morrow, 1993). Research on creativity has drawn on a variety of schools and fields (e.g., psychology, sociology) to understand why some individuals are more creative than others. Creativity research at the individual level of analysis has concentrated on individual differences and social context in such areas as personality (Feist, 1999; Gough, 1979), intellectual or cognitive abilities (Ford, 1996), creative selfefficacy (Carmeli & Schaubroeck, 2007; Tierney & Farmer, 2002, 2004), affective states and traits (Amabile et al., 2005; Madjar et al., 2002), creative role identity (e.g., Farmer, Tierney, & Kung-McIntyre, 2003), social support and expectations for creativity (e.g., Carmeli & Schaubroeck, 2007; Madjar et al., 2002), and the role of social networks in the creative process (e.g., Perry-Smith, 2006). The study of creativity is related to creative work involvement, since involvement in the creative process is a predictor of creativity at work. Individuals who contribute time and effort to creative processes associated with work are likely to behave in a creative manner. Although creative work involvement is likely to have an important role in predicting creative behavior, it should be noted that creative work involvement is only one predictor of creativity at work. Furthermore, an individual could engage time and effort resources in the creative processes and still not achieve outcomes of creativity. The study of individual involvement in creative work is still in its infancy (Atwater & Carmeli, in press). In this study we draw on the creativity literature and research to enhance our understanding of the role of specific aspects of the interpersonal context and the emotional experience of employees in enhancing individual involvement in creative work. We focus on two fairly new constructs that may have an effect on individual involvement in creative work—psychological safety and feelings of vitality. Psychological safety and creative work involvement Psychological safety refers to individuals’ perceptions of the consequences of taking interpersonal risks in their work environment (Edmondson, 1999, 2004). A belief that an individual is psychologically safe means that he or she feels able to show and employ his or herself without fear of negative consequences to self-image, status, or career (Kahn, 1990, p. 708). In the workplace it consists of basic beliefs about how others will respond when an individual employee chooses to act in a way that may be risky (e.g., Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 30, 785–804 (2009) DOI: 10.1002/job 10991379, 2009, 6, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/job.571 by Feng Chia University, Wiley Online Library on [16/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License VITALITY AND CREATIVITY R. KARK AND A. CARMELI asking a question, seeking feedback, reporting a mistake, or proposing a new idea) (Cannon & Edmondson, 2001; Edmondson, 2004). Edmondson (2003) argues that individuals engage in a cognitive process in which they weigh their decision whether to take a potential action or proceed in a given direction by assessing the interpersonal risk associated with that given action or behavior in the particular interpersonal work climate characterizing their organization or work group. If they believe that there is a chance that they might be hurt (e.g., embarrassed, criticized, ridiculed) they may chose to refrain from acting. Thus, an action that might be unthinkable in one work group can be readily taken in another, due to different beliefs about probable interpersonal consequences. In a classic study on organizational change, Schein and Bennis (1965) argued that a work environment characterized by psychological safety is necessary for individuals to feel safe and be able to change their behavior. This is because psychological safety is likely to help employees overcome defensiveness and learning anxiety. For example, when individuals encounter new ideas and information that disconfirm their prior knowledge, expectations, or hopes, they may experience a sense of anxiety that will hinder their ability to learn. A sense of psychological safety is likely to enable them to overcome their anxiety and make good use of new input (Schein, 1985). Various works have shown that group brainstorming is not as productive as nominal group brainstorming, since individuals experience social anxiousness in the group and are concerned about the presence of others and their evaluation. This can limit their creative contribution to the group process (Camacho & Paulus, 1995; Goncalo & Staw, 2006; Mullen, Johnson, & Salas, 1991). Nevertheless, research evidence suggests that psychological safety is positively related to team learning behaviors (Edmondson, 1999) and experimenting with creative ideas (Gilson & Shalley, 2004). For example, in a study that examined learning in interdisciplinary action teams, Edmondson (2003) found that effective team leaders were able to facilitate learning and promote innovation by creating a climate of psychological safety. Willingness to think of new ideas, explore novel directions, and behave creatively may require a safety net provided by a climate of psychological safety, since the process of exploration may be risky. For instance, Baer and Frese (2003) found a positive relationship between a climate of psychological safety and process innovativeness. Although these authors did not discuss psychological climate at the individual level and referred to process innovativeness rather than individual creativity, this evidence is suggestive of the importance of psychological safety for involvement in creative work processes. This is because novel ideas and creative inventions may seem at a first glance to be ridiculous or unrealistic, and in the process of development and exploration of such novel directions there is a high level of uncertainty, ambiguity, and the risk of making mistakes and arriving at impractical solutions. Thus, in a climate of low psychological safety, creative work involvement may lead to negative personal outcomes (e.g., decrease in respect, being seen as foolish, or even being sanctioned at times). Individual involvement in creative work will be hindered in climates in which employees feel that there is a low level of psychological safety, since creative individuals will be reluctant to become involved in the creative process and experiment with ideas. However, we posit that the relationship between psychological safety and creative work involvement is better understood through the intervening role of another affective factor, namely, feelings of vitality. The relationship between psychological safety and feelings of vitality is discussed below. Psychological safety and vitality at work Vitality refers to the positive feeling marked by the subjective experience of having energy (Nix, Ryan, Manly, & Deci, 1999), feeling alive, (Christianson, Spreitzer, Sutcliffe, & Grant, 2005; Spreitzer et al., Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 30, 785–804 (2009) DOI: 10.1002/job 10991379, 2009, 6, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/job.571 by Feng Chia University, Wiley Online Library on [16/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 788 789 2005) and fully functioning (Ryan & Bernstein, 2004). Vitality is an affective experience (Ryan & Frederick, 1997), described variously as positive energetic arousal (Thayer, 1989), vigor (Ryan & Bernstein, 2004), and zest (Miller & Stiver, 1997). It encompasses approaching life with excitement, energy, enthusiasm, and vigor and not doing things halfway or halfheartedly, living life as an adventure, feeling alive, and activated. In both the physical and mental sense, vitality refers to a feeling of aliveness. The word itself is derived from vita or ‘‘life’’ such that one who is vital feels alive, enthusiastic, and spirited. In the physical sense, vitality refers to feeling healthy, capable, and energetic. Psychologically, this state of aliveness makes a person feel that his or her actions have meaning and purpose (Ryan & Bernstein, 2004). It is important to note that vitality is more than mere arousal (Ryan & Bernstein, 2004). Vitality implies an infusion of positive energy (Ryan & Frederick, 1997). Although vitality is related to energy, vitality entails only energy experienced as positive and available to the self (Nix et al., 1999). Someone who is jittery, tense, furious, or angry is energized but not necessarily vital. Negative affectivity with high arousal (i.e., nervousness) has been found to negatively associate with subjective vitality in empirical studies (Ryan & Frederick, 1997). Negative energy, due to over-arousal, tenseness, or stimulants like caffeine, has been distinguished from vitality (Peterson & Seligman, 2004; Thayer, 1996). Furthermore, although vitality is a positive emotional state, it is a more discrete emotion than happiness and pleasure and have distinct determinants and correlates (Nix et al., 1999). Vitality is characterized by a high level of activation and thus differs from other non-activated or low activation positive emotions (Peterson & Seligman, 2003). Thus, according to the Circumplex Model of Affect formulated by Russell (1980), vitality is a positive affect emotion, which is characterized by a high level of arousal and is distinct from other emotions of positive affect with lower arousal levels (relaxed, pleased, serene, at ease, and satisfied). Vitality is a reinforcing experience in that people try to enhance, prolong, or reenact the circumstances they perceive as increasing their vital energy, and they try to diminish or avoid the circumstances that they perceive as decreasing their vitality (Collins, 1993). People who feel high levels of vitality tend to view events positively and expect that positive events will reoccur (Arkes, Herren, & Isen, 1988). Vitality affects the effort that people invest in activities, and can indicate how positive an experience people are having and their personal well-being (Ryan & Frederick, 1997). Researchers have linked positive social climates and a context of high-quality connections with increased vitality (Ryan & Frederick, 1997). A positive social climate, which is manifested by highquality connections among individuals, is likely to be perceived by employees as a context of psychological safety. Dutton and Heaphy (2003) in their theory of high-quality connections proposed that a major psychological effect of high-quality connections at work is a feeling of vitality. Dutton (2003) claimed that interpersonal connections are a key mechanism to energizing people at work, because it gives them a ‘‘sense of being eager to act and capable of action’’ (p. 6). A sense of psychological safety is at the root of high-quality connections or bonds between individuals. In a climate of high-quality connections, people feel safe to speak up, report mistakes and errors, and take risks without fearing a loss of status, power, respect, or confidence and without feeling humiliated or embarrassed. In a similar vein, Spreitzer et al. (2005) proposed that specific work environments are more likely to provide the requisite conditions for individuals to thrive. The major premise of their model is that various contextual features and relational resources enhance the sense of agency experienced by individual employees, which ultimately results in individual growth, learning, and vitality. Consistent with this line of thinking, in the current study we focus on psychological safety, contending that employee perceptions of psychological safety in the work group will be related to their sense of vitality. Work relationships that are endowed with psychological safety can be construed as a set of social resources (Losada & Heaphy, 2004; Miller & Stiver, 1997) that fuel individual vitality and thriving Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 30, 785–804 (2009) DOI: 10.1002/job 10991379, 2009, 6, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/job.571 by Feng Chia University, Wiley Online Library on [16/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License VITALITY AND CREATIVITY R. KARK AND A. CARMELI (Christianson et al., 2005). These social resources are endogenously produced through supportive interactions between an individual and others, and emerge in the organizational climate through repeated exposure to such interactions (Feldman, 2004; Worline, Dutton, Frost, Lilius, & Kanov, 2005). These kinds of social resources have been found to be associated with physiological changes in the neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and immune systems that contribute to openness to experience and to enhanced capacity to act (Reis & Gable, 2003). Thus, although not yet tested empirically, according to the theory developed by Spreitzer et al. (2005) positive interpersonal relationships at work are likely to contribute to a sense of vitality. Furthermore, in a recent conceptual paper Heaphy and Dutton (2008) suggest that positive relationships, which can be experienced in environments which are psychologically safe, contribute to physiological resources, and lead to physical strength and health. This sense of physical and mental strength has been defined as a component of the feeling of aliveness and vitality. Similarly, a recent empirical study showed that psychological safety promotes work engagement (May, Gilson, & Harter, 2004). Furthermore, in their theoretical model of coordination as energy-in-conversation, Quinn and Dutton (2005) explain how conversations among individuals in the workplace can increase or deplete energy, and how energy and vitality enhance individual efforts, which, in turn, lead to improved engagement and performance. According to Quinn and Dutton (2005) communication among individuals in an organizational setting is at the root of feeling energized. They contend that people’s perceived energy (vitality) is affected by the course of an interaction and is shaped through conversation. Drawing on self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000), they propose that energy and vitality increase when people interpret interpersonal interaction and conversation as increasing their autonomy, competence, or relatedness. Thus, a context in which individuals feel psychologically safe during interpersonal interactions is likely to contribute to their sense of vitality. Therefore, we propose that a work climate of psychological safety will enhance employees’ sense of vitality. Hypothesis 1: Psychological safety will be positively associated with individuals’ feelings of vitality at work Vitality and creative work involvement Interest in understanding the implications of workplace affect and emotions has grown in recent years, leading to increased interest in exploring the impact of affect on workplace creativity (e.g., James, Brodersen, & Eisenberg, 2004; Zhou, 1998). One of the major research directions has focused on the role of positive and negative affectivity on employees’ creativity (Amabile et al., 2005; James et al., 2004). Although there are some theories and findings suggesting that negative affect enhances creativity while positive affect reduces it (e.g., Feist, 1999; Kaufmann & Vosburg, 1997), most theories and findings indicate that creativity may be particularly susceptible to and promoted by positive affect (e.g., Amabile et al., 2005), mainly because positive affect leads to the sort of cognitive variation that contributes to creativity (Clore, Schwarz, & Conway, 1994). The current study explored the positive effect of vitality on individual creative work involvement. Researchers have noted, for example, that employees’ cognitive or motivational processes are enhanced by positive mood in such a way that they exhibit creative behaviors (Hirt, Levine, McDonald, & Melton, 1997). The broaden-and-build model of positive emotion suggests that when a person experiences positive emotions such as joy and love, his or her available repertoire of cognitions and actions is enhanced (Frederickson, 1998, 2003). Frederickson posits that experiences of various positive emotions prompt individuals to discard automatic everyday behavioral scripts and possibly pursue unscripted directions of cognition and action, which are likely to result in novel and creative Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 30, 785–804 (2009) DOI: 10.1002/job 10991379, 2009, 6, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/job.571 by Feng Chia University, Wiley Online Library on [16/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 790 791 ideas (Frederickson, 1998, 2001). When considering various aspects of engagement and involvement in the creative process, it is reasonable to suggest that vitality, which is a positive affect characterized by high levels of arousal, is likely to contribute to the active process of creative work involvement. Research findings from laboratory-based studies (e.g., Isen, 1999a; Madjar & Oldham, 2002) and organizational settings (e.g., Amabile et al., 2005; Madjar et al., 2002), generally support the proposed link between positive affect and creativity. For example, in a set of laboratory studies Isen and colleagues provide substantial evidence that positive affect can induce changes in cognitive processing that facilitate creative activity. Their studies showed that induced positive mood leads to higher levels of performance on dimensions relating to creativity, such as the number of associations generated, the level of ingenuity, the ability to group objects, and the ability to perform well on exercises requiring flexible problem solving (e.g., Estrada, Isen, & Young, 1994; Isen, 1999a,b; Isen & Daubman, 1984; Isen, Daubman, & Nowicki, 1987; Isen, Johnson, Mertz, & Robinson, 1985). Other studies have shown that participants in happy moods display greater fluency, and generate more responses and more divergent responses than participants in neutral or sad moods (Abele-Brehm, 1992; Hirt, Melton, McDonald, & Harackiewicz, 1996; Vosburg, 1998). A study conducted in an organizational setting (Madjar et al., 2002) showed that positive mood made a positive, significant contribution to creativity and that negative mood failed to make a significant contribution to creativity. Similarly, a more recent study by Amabile et al. (2005), also undertaken in an organizational setting, provides further support for the link between positive affect and creativity. Although the relationship between vitality and creativity has not been empirically studied before, the theoretical frameworks presented above, as well as the related empirical findings, lead us to expect that employees who are vital at work are likely to be highly involved in creative behavior at work, thus contributing to their creative performance. This is because vitality is not only experienced as positive affectivity, but is also a state of emotional arousal and a physical as well as a psychological sensation of aliveness. It seems reasonable to suggest that when individuals are positively aroused and are feeling healthy, capable, and energetic they will be more actively involved in creative behavior, seek ideas, make suggestions, engage in thought-provoking conversations, and will playfully approach novel directions. Consistent with the Circumplex Model of Affect (Russell, 1980), it is not likely that mere positive affect, which can be low in arousal and energy (e.g., relaxed, pleased, serene, at ease, and satisfied) will lead to high levels of engagement and involvement in creative work behavior. However, vitality, which is characterized by a high level of arousal, is more likely to lead to active engagement and involvement in creative work. Barron and Harrington’s (1981) review of personality characteristics leading to creativity suggests that creative individuals have core characteristics including high energy. Furthermore, their review shows that the creative personality scale, which predicts creativity, includes characteristics such as active, alert, energetic, and enthusiastic. All these characteristics capture the notion that energy and high levels of arousal are related to creativity. In line with Barron and Harrington’s (1981) focus on personality characteristics, we would like to further suggest that individuals whose sense of vitality is aroused at work, and who have a sense of aliveness and positive energy should tend to become active and involved in creative work showing engagement in terms of time and effort allocated to the creative process. Consistent with this idea, Quinn (2007, p. 81) recently contended with regards to work contexts that ‘‘people who feel energy (vitality) tend to . . .approach the world in new and different ways, they learn and develop new ways of getting things done. They can use their broadened thought and action repertoires to discover and create new means for getting work done.’’ Spreitzer et al. (2005) also suggest that when individuals are thriving at work and have a sense of vitality, they behave in ways which are likely to fuel sustained thriving. This implies that ‘‘when thriving, individuals are likely to engage in continued exploration behaviors’’ (Spreitzer et al., 2005, p. 545). These exploration Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 30, 785–804 (2009) DOI: 10.1002/job 10991379, 2009, 6, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/job.571 by Feng Chia University, Wiley Online Library on [16/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License VITALITY AND CREATIVITY R. KARK AND A. CARMELI behaviors might include seeking out new ideas, thinking of new inventions, or novel ways to do things. Thus, the following hypothesis is suggested: Hypothesis 2: Individuals’ feelings of vitality are positively related to creative work involvement. Psychological safety, vitality, and creative work involvement In the current study we further argue that a sense of vitality should mediate the relationship between a climate of psychological safety and employees’ creative involvement. As proposed above, psychological safety should enhance employees’ vitality, and this in turn is likely to effect employees’ creativity involvement. We suggest that one of the mechanisms that underlies the ability of employees who feel psychologically safe to become involved in creative work is their sense of vitality. Employees’ psychological safety fuels their ability to experience emotional and affective levels of arousal and energy, which is likely to further arouse their arouse creative work involvement. Various characteristics of the workgroup setting, relationships, and climate which enable employees to feel psychologically safe form a platform for employees to experience high levels of positive arousal, energy, engagement, and aliveness. This affective experience of vitality is likely to contribute to employees’ active involvement in exploration behaviors (e.g., seeking out novel ideas, thoughts, inventions, or new ways to do things). A recent extensive review of the literature on the influence of affect in organizations shows that emotions affect employees’ performance, behavior, decision making processes, and creativity in organizations (Barsade & Gibson, 2007). This suggests that emotions play a major role in affecting employees’ cognitions and actions at work. Specifically, it is reasonable to expect that psychological safety will affect employees’ cognitions and actions of involvement in creative work behaviors, through the arousal of emotions of vitality. Previous investigations have provided results that are generally consistent with these arguments. For example, Madjar et al. (2002) showed that supportive behavior and encouragement from coworkers and family members influence the moods of employees, which in turn, affected their creativity. Carmeli and Spreitzer (in press) have documented the how trust and connectivity augment a sense of thriving, which, in turn, results in engagement in innovative behaviors at work. This suggests that support for creativity may lead employees to experience such positive moods as excitement, enthusiasm, and vitality, which can result in creative behavior. Alternatively, when support from others is absent, individuals may experience negative mood states and their creativity will decrease. According to Dutton and Heaphy (2003) a work climate that is characterized by high-quality connections is likely to be life-enhancing and energizing and to foster human development and growth. We contend that a work context characterized by a high level of connections and psychological safety will induce a sense of vitality and energy and that this state will enable individuals to lower their defenses and unleash their motivation to explore and become involved in creativity. Furthermore, a recent theoretical work (Heaphy & Dutton, 2008) suggested that the physiological resourcefulness generated in positive social interactions contributes to higher levels of physiological resources for engagement in a work role. This suggests that an environment characterized by psychological safety can contribute to a sense of physical and mental strength (i.e., vitality), and this in turn will effect individuals’ ability to become engaged in work behavior, and more specifically be involved in creative work. Hence, we suggest the following hypothesis: Hypothesis 3: Employees’ vitality will mediate the relationship between psychological safety and employees’ creative work involvement. Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 30, 785–804 (2009) DOI: 10.1002/job 10991379, 2009, 6, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/job.571 by Feng Chia University, Wiley Online Library on [16/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 792 793 Methods Respondents and data collection One hundred eighty part-time graduate students, studying social sciences at a large university in Israel were asked to participate in this study and complete a structured survey at two points in time, with a lag of two weeks. We briefly introduced the participants to the goals of the study and promised full confidentiality and the delivery of the findings upon request. All respondents held employment positions in a relatively wide variety of organizations operating in such industries as banking and insurance, communication, electronics, food and beverages, and pharmaceutical and medical equipment. One hundred twenty-nine respondents completed the two surveys, representing a response rate of 71.66 per cent. Forty-one per cent of the respondents were female. The respondents’ average age was 30.87 years (s.d. 6.38), and their average tenure within the organization was 3.35 years (s.d. 2.62). Seven per cent of the respondents held a senior-level managerial position, 25.6 per cent held a middlelevel managerial position, and the others held non-managerial positions. Measures Appendix A presents all measurement items for the research variables. Data about the control variables, independent and mediating variables (psychological safety and feelings of vitality) were collected at time 1, and data about creative work involvement were collected at time 2. Creative work involvement We used Carmeli and Schaubroeck’s (2007) scale for assessing employee involvement in creative work. This scale is based on a nine-item measure of employee creativity developed and used by Tierney et al. (1999) that exhibits high reliability (a ¼ 0.95) and validity. Respondents were asked to indicate the extent to which they regularly exhibit various behaviors that are indicative of creative work involvement. Sample items include ‘‘demonstrating originality at work’’ and ‘‘generating novel, but operable work-related ideas’’ characterize their creative behaviors. Responses were made on a sixpoint Likert-type scale ranging from 1 ¼ strongly disagree to 6 ¼ strongly agree. Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was 0.95, similar to the reliability of 0.93 reported in Carmeli and Schaubroeck’s (2007) study. Feelings of vitality This measure indicates the degree to which an individual feels positive arousal and energy in her or his connection with others at work (Dutton & Heaphy, 2003) and was measured using five items of the scale developed by Carmeli (in press). This scale was validated using a factor analytic procedure and had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89. Sample items are: ‘‘I am full of positive energy when I am at work’’ and ‘‘I am most vital when I am at work.’’ Responses were made on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 ¼ strongly disagree to 5 ¼ strongly agree. Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was 0.92. Psychological safety assesses the extent to which members of an organization feel psychologically safe to take risks, speak up, and discuss issues openly. We adapted six items from Edmondson’s (1999) psychological safety scale. Sample items are: ‘‘Members of this organization are able to bring up problems and tough issues’’ and ‘‘It is safe to take a risk in this organization.’’ Items were all anchored Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 30, 785–804 (2009) DOI: 10.1002/job 10991379, 2009, 6, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/job.571 by Feng Chia University, Wiley Online Library on [16/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License VITALITY AND CREATIVITY R. KARK AND A. CARMELI Psychological Safety .44*** Time 1 Vitality R2 = .20 Time 1 .48*** Creative Work Involvement R2 = .23 Time 2 Figure 1. The research model. Note: Standardized parameter estimates. N ¼ 128. p < .001; p < .01; p < .05. This is a simplified version of the actual model. It does not show indicators, error terms, covariances or exogenous factor variances on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 ¼ strongly disagree to 7 ¼ strongly agree. Cronbach’s alpha for psychological safety was 0.76. Control variables We controlled for educational level, which may influence creative behavior (Amabile, 1988; Tierney & Farmer, 2004). We also controlled for tenure in the organization, as this reflects work domain expertise (Oldham & Cummings, 1996; Tierney & Farmer, 2004). In addition, we controlled for respondents’ gender, age, and role (senior, mid-level, and non-managerial roles). Data analysis To test the research model presented in Figure 1, we performed structural equation modeling (SEM) (Bollen, 1989) using AMOS 5 (Arbuckle & Wothke, 2003). In order to assess the fit of the research model in Figure 1, we used several goodness-of-fit indices as suggested in SEM (Joreskog & Sorbom, 1993; Kline, 1998) such as Chi-Square statistics divided by the degree of freedom (x2/df); relative fit index (RFI), normed fit index (NFI), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis coefficient (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). As suggested in the SEM literature (Joreskog & Sorbom, 1993; Kline, 1998), we used the following criteria for goodness-of-fit indices to assess the model-fit: x2/df ratio is recommended to be less than 3; the values of RFI, NFI, CFI, and TLI are recommended to be greater than 0.90; RMSEA is recommended to be up to 0.05, and acceptable up to 0.08. Results The means, standard deviations, and correlations for the research variables are presented in Table 1. The bivariate correlations indicate that psychological safety is significantly associated with vitality and creative work involvement (r ¼ .40, p < .001; r ¼ .42, p < .001, respectively). We also found that vitality is significantly related to creative work involvement (r ¼ .45, p < .001). The research model was analyzed utilizing the two-step approach to SEM (Bollen, 1989) as outlined in Anderson and Gerbing (1988), and recommended by others (e.g., Hoyle & Panter, 1995; Medsker, Williams, & Holahan, 1994). We first tested the fit of a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model to the observed data. Next, we tested a nested structural model that yields information concerning the structural model that best accounts for the co-variances observed between the model’s exogenous and endogenous constructs (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 30, 785–804 (2009) DOI: 10.1002/job 10991379, 2009, 6, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/job.571 by Feng Chia University, Wiley Online Library on [16/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 794 795 4 9 Table 1. Means, standard deviations (s.d.), and correlations Mean s.d. 1 2 3 5 6 7 8 1. Gender (1 ¼ female) — — — 2. Respondent age 30.87 6.38 .40 — .37 — 3. Organizational tenure 3.35 2.62 .17 4. Education 3.83 0.53 .14 .05 .05 — 5. Position type (1 ¼ non-managerial) — — .18 .22 .16 .05 — 6. Position type (1 ¼ senior executive) — — .22 .33 .24 .03 .24 — 7. Psychological safety 4.54 0.75 .11 .08 .16 .16 .11 .10 — 8. Feelings of vitality 3.53 0.95 .03 .10 .18 .13 .29 .13 .40 — 9. Creative work involvement 4.39 0.85 .18 .23 .24 .10 .40 .12 .42 .45 — N ¼ 129, Two-tailed test;p < .05; p < .01; p < .001. Preliminary analyses Using CFA, a measurement model was tested in order to assess whether each of the measurement items would load significantly onto the scales with which they were associated. The results of the overall CFA and the goodness-of-fit statistics showed acceptable fit with the data (x2 of 311.5 on 152 degrees of freedom; CFI ¼ 0.90; IFI ¼ 0.90; TLI ¼ 0.88; RMSEA ¼ 0.09) were achieved. Standardized parameter estimates from items to factors ranged from 0.51 to 0.91. In addition, the results for the CFA indicated that the relationship between each indicator variable and its respective variable was statistically significant ( p < .01), establishing the posited relationships among indicators and constructs, and thus, convergent validity (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1998). We also examined two alternative measurement models: (1) a one-factor model and (2) a two-factor model where items measuring psychological safety and vitality were loaded onto one factor and the items measuring creative work involvement loaded onto another factor. The results of a one-factor model produced the following goodness-of-fit statistics (x2 of 807.7 on 155 degrees of freedom; CFI ¼ 0.61; IFI ¼ 0.62; TLI ¼ 0.52; RMSEA ¼ 0.18) were achieved. The goodness-of-fit statistics (x2 of 431.6 on 154 degrees of freedom; CFI ¼ 0.83; IFI ¼ 0.83; TLI ¼ 0.79; RMSEA ¼ 0.12) for a two-factor model were achieved. There were significant differences between the two nested models (one- and two-factor models) and the baseline model (three-factor model). Chi-square difference between the baseline model and the one factor model (496.2, df differences ¼ 3, p < .01), as well against the two-factor model (120.1, df differences ¼ 2, p < .01), further supported the preference of the three-factor model. Thus, these findings indicate that the hypothesized three-factor model had better fit with the data and therefore we accepted this measurement model. Test of the model The research model was tested based on the results of a confirmatory analysis on all the items of the independent, mediating, and dependent research variables. In this model, which is shown in Figure 1, the ovals represent latent variables. For clarity, the latent indicators are not shown in Figure 1, but it does present the standardized parameter estimates. Since the research variables are multi-item latent constructs we used maximum likelihood SEM to test our model’s hypotheses. As noted above, we evaluated model fit using various fit indices and the significance of the completely standardized path estimates (Bollen, 1989). Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 30, 785–804 (2009) DOI: 10.1002/job 10991379, 2009, 6, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/job.571 by Feng Chia University, Wiley Online Library on [16/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License VITALITY AND CREATIVITY R. KARK AND A. CARMELI The SEM in Figure 1 summarizes our hypothesized fully mediated model. A x2 of 264.2 on 150 degrees of freedom, and other goodness-of-fit statistics (CFI ¼ 0.93; IFI ¼ 0.93; TLI ¼ 0.91; NFI ¼ 0.86; RMSEA ¼ 0.07) indicate that the model fits the data well. The multiple squared correlation coefficients (R2s) for vitality and creative work involvement were 0.20 and 0.23, respectively. The findings in Figure 1 support Hypothesis 1 which predicted that there would be a positive relationship between psychological safety and feelings of vitality (0.44, p < .001). The results also provide support for Hypothesis 2 which posited that feelings of vitality would be positively and significantly associated with creative work involvement (0.48, p < .001). Following the procedure outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986) as well as revisions in mediation procedures as discussed in Kenny, Kashy, and Bolger’s (1998) work for testing full mediation, we used SEM to test the mediating effect of vitality in the relationship between psychological safety and creative work involvement. When vitality (the mediator) was specified, we found that the relationship between psychological safety and creative work involvement remained significant, though the effect was reduced (0.37, p < .001. vs. 0.21, p < .05). The relationships between both (1) psychological safety and vitality and (2) vitality and creative work involvement remained significant (0.44, p < .001; 0.38, p < .001, respectively). These findings indicate partial mediation; there is both a direct and an indirect (through vitality) significant relationship between psychological safety and creative work involvement, which thus fails to confirm Hypothesis 3 that posited a full mediating relationship between psychological safety, feelings of vitality and creative work involvement. The multiple squared correlation coefficients (R2s) for vitality and creative work involvement were 0.20 and 0.26, respectively. The results of this partially mediated model are shown in Figure 2. A x2 of 260.3 on 149 degrees of freedom, and other goodness-of-fit statistics (CFI ¼ 0.93; IFI ¼ 0.93; TLI ¼ 0.91; NFI ¼ 0.86; RMSEA ¼ 0.07) indicate that this alternative partial mediation model is not significantly different (x2 difference ¼ 3.9, df difference ¼ 1, p < .05) from the hypothesized mediation model and generally fits the data well. Discussion The main goal of this study was to examine the role of psychological safety in individual involvement in creative work, and the role of vitality as a possible intervening mechanism that mediates the relationship between psychological safety and individual involvement in creative work. The findings of this study, as predicted, show that psychological safety is positively related to individuals’ sense of vitality, and to individual involvement in creative work, and that vitality partially mediates the relationship between psychological safety and in turn, results in enhanced individual involvement in creative work (i.e., creative work involvement). .44*** / .21* Psychological Safety .44*** Time 1 Vitality R2 = .20 Time 1 .48*** / 38*** Creative Work Involvement R2 = .26 Time 2 Figure 2. The research model. Note: Standardized parameter estimates. N ¼ 128. p < .001; p < .01; p < .05. Estimates in bold are from an SEM model which includes the connectedness mediator. This is a simplified version of the actual model. It does not show indicators, error terms, covariances or exogenous factor variances Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 30, 785–804 (2009) DOI: 10.1002/job 10991379, 2009, 6, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/job.571 by Feng Chia University, Wiley Online Library on [16/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 796 797 Our findings suggest that the interpersonal work context is of importance in enabling individuals to be involved in creative tasks. Although previous research has shown that characteristics of the social and behavioral context play a central role in employees’ creative behavior (e.g., Carmeli & Schaubroeck, 2007; Madjar et al., 2002) as well as in individuals’ innovative behaviors (Carmeli & Spreitzer, in press) they have focused on direct expectations from co-workers, managers and/or family for creativity. However, the importance of the more general interpersonal characteristics of work contexts, which are not focused specifically on support for creativity, have hardly ever been studied empirically. The present study sheds light on the role of psychological safety as a key enabler of employee involvement in creative work. In addition, much research has been directed toward the antecedents of work and job involvement (e.g., Carmeli, 2005; Dubin, 1956; Kanungo, 1982; Rabinowitz & Hall, 1977). These studies have not considered various types of job involvement. This study thus contributes to a unique line of research (Carmeli & Schaubroeck, 2007) in examining a special type of work involvement: engaging in creative tasks. Furthermore, we examined how a sense of vitality influences employees’ creativity. Drawing on the recent literature on POS with regards to energy (e.g., Quinn & Dutton, 2005), vitality and thriving (e.g., Spreitzer et al., 2005) our findings support the notion that employee feelings of vitality are likely to enhance creativity at work. These findings are in line with previous studies that have shown the effect of positive affectivity on creative behavior (e.g., Amabile et al., 2005; Isen, 1999a,b; James et al., 2004; Madjar et al., 2002). Our findings elaborate on an emerging stream of research that emphasizes the importance of affect in creative processes (Amabile et al., 2005). The results of our study, which target the discrete positive emotion of vitality, suggest that affective states of high positive arousal such as excitement, energy, enthusiasm, and vigor are key mechanisms for fostering creative thoughts and behavior. For instance, recent research has shown that thriving is key for facilitating one’s engagement in innovative tasks at work (Carmeli & Spreitzer, in press). This, along with the findings of a few other recent studies (Amabile et al., 2005; George & Zhou, 2002; Madjar et al., 2002), further demonstrates the importance of integrating affect into theories of creativity. In our research model we propose that vitality enhances creative involvement. However, it is also possible that creative involvement can enhance a sense of vitality in employees. According to Spreitzer et al. (2005) vitality and thriving may be sustained through creativity. They contend that having an artistic mode and being free to think more freely and creatively, may in turn create additional resources to fuel a sense of vitality and contribute to sustained thriving. Thus, it is possible that being creative or engaging in creative work will further lead to higher levels of vitality, subsequently fostering further creativity. This cyclic process is in line with the findings of Amabile et al. (2005) and their model of the affect–creativity linkage in organizations, which suggests a more dynamic view of the relationship between affect and creativity. Amabile et al. (2005) propose that the feelings of enjoyment that arise while doing an activity creatively may set up an affect–creativity cycle of enhanced creativity and enhanced intrinsic enjoyment. The affect–creativity cycle suggests that affective states that follow from the invention of a novel idea and its reception by others in the organization may give rise to subsequent changes in cognition and creativity. When individuals experience positive inner affect stemming from the creative act (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996; Sandelands, 1988) or encouraging responses to their ideas, a cycle may be established in which cognitive variation and creativity are subsequently increased (Amabile et al., 2005). Limitations and future research directions Several limitations in the current study warrant caution in interpreting the findings. Although our data were collected at two points in time, one cannot claim causal relationships. The research data and Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 30, 785–804 (2009) DOI: 10.1002/job 10991379, 2009, 6, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/job.571 by Feng Chia University, Wiley Online Library on [16/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License VITALITY AND CREATIVITY R. KARK AND A. CARMELI design did not allow us to test the causal direction between vitality and creativity. Future studies should use experimental and longitudinal designs to better explore the casual vitality–creative relationship. In addition, using single source data may be associated with common method errors. However, we attempted to mitigate this limitation by collecting data about the independent and dependent variables at two different points in time. Our measurement model and results of confirmatory analysis suggest that common method bias, though it may exist, may not be severe. The participants in this study were employed graduate students at the university. Although they were part-time students (all students held employment positions in work organizations), future research could replicate this findings using real-world work settings. It is also possible that some of the students may not have been highly involved in their work organizations. However, most of the students in our sample and in Israel in general are relatively older (the average respondent’s age was over 30, and the mean tenure in the organizations was over 3 years). Thus, the respondents had enough experience and acquaintance with a work organization to report about the interpersonal climate and their sense of vitality and creativity at work. Future research might also examine other manifestations of the work context, apart from psychological safety, which may arouse a sense of vitality among employees and enhance their creativity. Further research is also needed to determine under which conditions feelings of vitality can be sustained and how this impacts creativity at work over a long period of time. According to temporal analyses of the data from Amabile et al. (2005) the impact of creativity on affect is fairly immediate and not particularly long-lived. Furthermore, vitality may result in various positive work outcomes (e.g., performance, satisfaction, affective commitment). Future studies should examine possible moderators which may enhance or undermine the relationship between vitality and creative work involvement (e.g., organizational setting, supervisors’ support in creative work involvement, etc.). In the current study we focus on vitality, which in the Russell (1980) Circumplex Model of Affect represents a positive affect emotion characterized by a high level of arousal. It would be of interest in future studies to explore how other emotions of positive affect with lower levels of arousal (e.g., relaxed and serene) as well as negative emotions with high levels of arousal (e.g. anger, jittery and tense) or even over-arousal affect employees’ creative work involvement. It would also be of interest to explore not only the relationship between vitality and creative work involvement, but vitality and actual creative outcomes. Finally, Fredrickson (2003) suggests that the positive emotions expressed in work teams may be contagious. Several recent empirical studies have examined the mood contagion process in work groups, documenting the spread of emotions among group members (e.g., Barsade, 2002; Cherulnik, Donley, Wiewel, & Miller, 2001). This may imply that individuals’ sense of vitality in the workplace may transfer to other team members, arousing collective creative behavior. Thus, it would be worthwhile to explore vitality at the group level, to enhance our understanding of the extent to which group vitality generates a higher level of creativity. Conclusion Our study suggests that feelings of psychological safety directly affect employees’ individual involvement in creative work and that vitality partially mediates the relationship between employees’ psychological safety and their involvement in creative work. These findings highlight the fact that researchers and managers need to consider how the interpersonal work context can foster feelings of vitality and creative behaviors at work. We encourage future research examining the effects of positive interpersonal work contexts on psychological experiences and creative work outcomes. Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 30, 785–804 (2009) DOI: 10.1002/job 10991379, 2009, 6, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/job.571 by Feng Chia University, Wiley Online Library on [16/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 798 799 Acknowledgements We thank Ray Noe and three anonymous JOB reviewers for their constructive and helpful feedback and appreciate the comments of Heike Bruch, Jane Dutton, Gretchen Spreitzer, and Ryan Quinn. Author biographies Ronit Kark is a faculty member of the organizational studies in the Departments of Psychology and Sociology at Bar-Ilan University. She received her PhD from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Her current research interests include leadership, mentoring relationships, identity and identification processes, emotions, and gender in organizations. Abraham Carmeli is a faculty member of the Graduate School of Business Administration at Bar-Ilan University. He received his PhD from the University of Haifa. His current research interests include complementarities and fit, top management teams, organizational identification, learning from failures, interpersonal relationships, and individual behaviors at work. References Abele-Brehm, A. (1992). Positive and negative mood influences on creativity: Evidence for asymmetrical effects. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 23, 203–221. Amabile, T. M. (1983). The social psychology of creativity. New York: Springer-Verlag. Amabile, T. M. (1988). A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 10, pp. 123–167). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Amabile, T. M. (1998). How to kill creativity. Harvard Business Review, 76, 77–88. Amabile, T. M., Barsade, S. G., Mueller, J. S., & Staw, B. M. (2005). Affect and creativity at work. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50, 367–403. Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 1154–1184. Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411–423. Arbuckle, J. L., & Wothke, W. (2003). Amos 5.0 Update to the Amos User’s Guide. Chicago, IL: Smallwaters Corporation. Arkes, H. R., Herren, L. T., & Isen, A. M. (1988). The role of potential loss in the influence of affect on risk-taking behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 42, 181–193. Atwater, L., & Carmeli, A. (in press). Leader-member exchange, feelings of energy and involvement in creative work. The Leadership Quarterly, in press. Baer, M., & Frese, M. (2003). Innovation is not enough: Climates for initiative and psychological safety, process innovations, and firm performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24, 45–68. Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality Psychology, 51, 1173– 1182. Barron, F., & Harrington, D. M. (1981). Creativity, intelligence, and personality. Annual Review of Psychology, 32, 439–476. Barsade, S. G. (2002). The ripple effect: Emotional contagion and its influence on group behavior. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47, 644–675. Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 30, 785–804 (2009) DOI: 10.1002/job 10991379, 2009, 6, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/job.571 by Feng Chia University, Wiley Online Library on [16/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License VITALITY AND CREATIVITY R. KARK AND A. CARMELI Barsade, S. G., & Gibson, D. E. (2007). Why does affect matter in organizations? Academy of Management Perspectives, 21, 36–59. Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley. Camacho, L. M., & Paulus, P. B. (1995). The role of social anxiousness in group brainstorming. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 1071–1080. Cameron, K. S., Dutton, J. E., & Quinn, R. E. (Eds.). (2003). Positive organizational scholarship. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers. Cannon, M. D., & Edmondson, A. C. (2001). Confronting failure: Antecedents and consequences of shared beliefs about failure in organizational work groups. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22, 161–177. Carmeli, A. (2005). Exploring determinants of job involvement: An empirical test among senior executives. International Journal of Manpower, 26, 457–472. Carmeli, A. (in press). High-quality relationships, vitality, and job performance. In Ashkanasy, N. Zerbe, W. J. & Härtel, C. E. J. (Eds.). Research on emotion in organizations (Vol. 5). Oxford, UK: Elsevier. Carmeli, A., & Schaubroeck, J. (2007). The influence of leaders’ and other referents’ normative expectations on individual involvement in creative work. The Leadership Quarterly, 18, 35–48. Carmeli, A., & Spreitzer, G. M. (in press). Trust, connectivity, and thriving: Implications for innovative behaviors at work. Journal of Creative Behavior. Cherulnik, P. D., Donley, K. A., Wiewel, T. S., & Miller, S. R. (2001). Charisma is contagious: The effects of leader’s charisma on observers’ affect. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31, 2149–2159. Christianson, M. K., Spreitzer, G. M., Sutcliffe, K. M., & Grant, A. M. (2005). An empirical examination of thriving at work. Working paper, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Clore, G. L., Schwarz, N., & Conway, M. (1994). Cognitive causes and consequences of emotion. In R. S. Wyer, & T. K. Srull (Eds.), Handbook of social cognition (pp. 323–417). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Collins, R. (1993). Emotional energy as the common denominator of rational action. Rationality and Society, 5, 203–230. Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and innovation. New York: Harper Collins. Dubin, R. (1956). Industrial workers’ world: A study of the ‘‘central life interests’’ of industrial workers. Social Problems, 3, 131–142. Dutton, J. E. (2003). Energize your workplace: How to build and sustain high-quality connections at work. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. Dutton, J. E., & Heaphy, E. D. (2003). The power of high-quality connections at work. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship (pp. 263–278). San Francisco: BerrettKoehler Publishers. Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 350–383. Edmondson, A. C. (2003). Speaking up in the operating room: How team leaders promote learning in interdisciplinary action teams. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 1419–1452. Edmondson, A. C. (2004). Psychological safety, trust, and learning in organizations: A group-level lens. In R. M. Kramer, & K. S. Cook (Eds.), Trust and distrust in organizations: Dilemmas and approaches (pp. 239–272). New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Estrada, C. A., Isen, A., & Young, M. J. (1994). Positive affect improves creative problem solving and influences reported source of practice satisfaction in physicians. Motivation and Emotion, 18, 285–299. Farmer, S. M., Tierney, P., & Kung-McIntyre, K. (2003). Employee creativity in Taiwan: An application of role identity theory. Academy of Management Journal, 46, 618–630. Feist, G. J. (1999). Affect in artistic and scientific creativity. In S. W. Russ (Ed.), Affect, creative experience, and psychological adjustment (pp. 93–109). Philadelphia: Brunner/Mazel. Feldman, M. S. (2004). Resources in emerging structures and processes of change. Organization Science, 15, 295– 309. Ford, C. (1996). A theory of individual creative action in multiple social domains. Academy of Management Review, 21, 1112–1142. Frederickson, B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology, 2, 300–319. Frederickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. American Psychologist, 56, 218– 226. Fredrickson, B. L. (2003). Positive emotions and upward spirals in organizations. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship (pp. 163–175). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler. Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 30, 785–804 (2009) DOI: 10.1002/job 10991379, 2009, 6, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/job.571 by Feng Chia University, Wiley Online Library on [16/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 800 801 George, J. M., & Zhou, J. (2002). Understanding when bad moods foster creativity and good ones don’t: The role of context and clarity of feelings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 687–697. Gilson, L. L., & Shalley, C. E. (2004). A little creativity goes a long way: An examination of teams’ engagement in creative processes. Journal of Management, 30, 453–470. Goncalo, J. A., & Staw, B. M. (2006). Individualism–collectivism and group creativity. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 100, 96–109. Gough, H. G. (1979). A creative personality scale for the adjective check list. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 1398–1405. Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Heaphy, E. D., & Dutton, J. E. (2008). Positive social interactions and the human body at work: Linking organizations and physiology. Academy of Management Review, 33, 137–162. Hirt, E. R., Melton, R. J., McDonald, H. E., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (1996). Processing goals, task interest, and the mood-performance relationship: A mediational analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 245–261. Hirt, E. R., Levine, G. M., McDonald, H. E., & Melton, R. J. (1997). The role of mood in quantitative and qualitative aspects of performance: Single or multiple mechanisms? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 33, 602–629. Hoyle, R. H., & Panter, A. T. (1995). Writing about structural equation models. In Hoyle R. H. (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues and applications (pp. 158–176). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Isen, A. (1999a). On the relationship between affect and creative problem solving. In S. W. Russ (Ed.), Affect, creative experience and psychological adjustment (pp. 3–18). Philadelphia: Brunner/Mazel. Isen, A. (1999b). Positive affect. In T. Dagleish, & M. Power (Eds.), Handbook of cognition and emotion (pp. 521– 539). New York: Wiley. Isen, A. M., & Daubman, K. A. (1984). The influence of affect on categorization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 1206–1217. Isen, A. M., Daubman, K. A., & Nowicki, G. P. (1987). Positive affect facilitates creative problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 1122–1131. Isen, A. M., Johnson, M. S., Mertz, E., & Robinson, G. F. (1985). The influence of positive affect on the unusualness of word associations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 1413–1426. James, K., Brodersen, M., & Eisenberg, J. (2004). Workplace affect and workplace creativity: A review and preliminary model. Human Performance, 17, 169–194. Janssen, O., van de Vliert, E., & West, M. (2004). The bright and dark sides of individual and group innovation: a Special Issue introduction. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 129–145. Joreskog, K. G., & Sorbom, D. (1993). LISREL 8: Structural equation modeling with the SIMPLIS command language. Chicago: Scientific International Software. Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 692–724. Kanungo, R. N. (1982). Measurement of job and work involvement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67, 341–349. Kaufmann, G., & Vosburg, S. K. (1997). Paradoxical mood effects on creative problem-solving. Cognition and Emotion, 11, 151–170. Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D., & Bolger, N. (1998). Data analysis in social psychology. In D. Gilbert, S. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (pp. 233–265). New York: McGraw-Hill. Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: The Guilford Press. Losada, M., & Heaphy, E. (2004). The role of positivity and connectivity in the performance of business teams: A nonlinear dynamics model. American Behavioral Scientist, 47, 740–765. Luthans, F. (2002a). Positive organizational behavior: Developing and maintaining psychological strengths. Academy of Management Executive, 16, 57–72. Luthans, F. (2002b). The need for and meaning of positive organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 695–706. Luthans, F. (2003). Positive organizational behavior (POB): Implications for leadership and HR development and motivation. In R. M. Steers, L. W. Porter, & G. A. Bigley (Eds.), Motivation and leadership at work (pp. 178– 195). New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. Madjar, N., & Oldham, G. R. J. (2002). Preliminary tasks and creative performance on a subsequent task: Effects of time on preliminary tasks and amount of information about the subsequent task. Creativity Research Journal, 14, 239–251. Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 30, 785–804 (2009) DOI: 10.1002/job 10991379, 2009, 6, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/job.571 by Feng Chia University, Wiley Online Library on [16/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License VITALITY AND CREATIVITY R. KARK AND A. CARMELI Madjar, N., Oldham, G., & Pratt, M. (2002). There’s no place like home? The contributions of work and non-work sources of creativity support to employees’ creative performance. Academy of Management Journal, 4, 757– 767. May, D. R., Gilson, R. L., & Harter, L. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety, and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77, 11–38. Medsker, G. J., Williams, L. J., & Holahan, P. J. (1994). A review of current practices for evaluating causal models in organizational behavior and human resources management research. Journal of Management, 20, 239–264. Miller, J. B., & Stiver, I. P. (1997). The healing connection: Therapy and in life. Boston: Beacon Press. Morrow, P. C. (1993). The theory and measurement of work commitment. Greenwich, Connecticut: JAI Press Inc. Mullen, B., Johnson, C., & Salas, E. (1991). Productivity loss in brainstorming groups: A meta analytic integration. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 12, 3–23. Nix, G., Ryan, R. M., Manly, J. B., & Deci, E. L. (1999). Revitalization through self-regulation: The effects of autonomous and controlled motivation on happiness and vitality. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 266–284. Oldham, G. R., & Cummings, A. (1996). Employee creativity: Personal and climateual factors at work. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 607–634. Perry-Smith, J. E. (2006). Social yet creative: The role of Social relationships in facilitating individual creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 49, 85–101. Perry-Smith, J. E., & Shalley, C. E. (2003). The social side of creativity: A static and dynamic social network perspective. Academy of Management Review, 28, 89–106. Peterson, C. M., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2003). Positive organizational studies: Lessons from positive psychology. In K. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship (pp. 14–27). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers. Peterson, C. M., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Quinn, R. W. (2007). Energizing others in work connections. In J. E. Dutton, & B. R. Ragins (Eds.), Exploring positive relationships at work: Building a theoretical and research foundation (pp. 73–90). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Quinn, R. W., & Dutton, J. E. (2005). Coordination as energy-in-conversation. Academy of Management Review, 30, 36–57. Rabinowitz, S., & Hall, D. T. (1977). Organizational research on job involvement. Psychological Bulletin, 84, 265– 288. Reis, H. T., & Gable, S. L. (2003). Toward a positive psychology of relationships. In C. L. M. Keyes (Ed.), Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived (pp. 129–159). Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association. Russell, J. A. (1980). A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 1161–1178. Ryan, R. M., & Bernstein, J. H. (2004). Vitality. In C. Peterson, & M. E. P. Seligman (Eds.), Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification (pp. 273–290). New York: Oxford University Press. Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78. Ryan, R. M., & Frederick, C. (1997). On energy, personality, and health: Subjective vitality as a dynamic reflection of well-being. Journal of Personality, 65, 529–566. Sandelands, L. E. (1988). The concept of work feeling. Journal of the Theory of Social Behavior, 18, 437–457. Schein, E. (1985). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Schein, E., & Bennis, W. (1965). Personal and organizational change through group methods. New York: Wiley. Scott, S. G., & Bruce, R. A. (1994). Determinants of innovative behavior: A path model of individual innovation in the workplace. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 580–607. Seligman, M., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An Introduction. American Psychologist, 55, 5–14. Spreitzer, G., Sutcliffe, K., Dutton, J., Sonenshein, S., & Grant, A. M. (2005). A. socially embedded model of thriving at work. Organization Science, 16, 537–549. Sternberg, R. J. (1988). The nature of creativity: Contemporary psychological perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Thayer, R. E. (1989). The biopsychology of mood and arousal. New York: Oxford University Press. Thayer, R. E. (1996). The origin of everyday moods. New York: Oxford University Press. Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 30, 785–804 (2009) DOI: 10.1002/job 10991379, 2009, 6, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/job.571 by Feng Chia University, Wiley Online Library on [16/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 802 803 Tierney, P., & Farmer, S. M. (2002). Creative self-efficacy: Its potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Academy of Management Journal, 45, 1137–1148. Tierney, P., & Farmer, S. M. (2004). The Pygmalion process and employee creativity. Journal of Management, 30, 413–432. Tierney, P., Farmer, S. M., & Graen, G. B. (1999). An examination of leadership and employee creativity: The relevance of traits and relations. Personnel Psychology, 52, 591–620. Vosburg, S. K. (1998). The effects of positive and negative mood on divergent thinking performance. Creativity Research Journal, 11, 165–172. Weisberg, R. W. (1988). Problem solving and creativity. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), The nature of creativity: Contemporary psychological perspectives (pp. 148–176). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Worline, M., Dutton, J. E., Frost, P., Lilius, J., & Kanov, J. (2005). Fertile soil: The organizing dynamics of resilience in work organizations. Working paper, University of Michigan. Wright, T. A. (2003). Positive organizational behavior: An idea whose time has truly come. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24, 437–442. Zhou, J. (1998). Feedback style, task autonomy, and achievement orientation: Interactive effects on creative performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 261–276. Appendix A: Measurement Items Items measuring creative work involvement (Source: Carmeli & Schaubroeck, 2007; Tierney et al., 1999) I demonstrated originality in my work I took risks in terms of producing new ideas in doing my job I found new uses for existing methods or equipment I solved problems that had caused others difficulty I tried out new ideas and approaches to problems I identified opportunities for new products/processes I generated novel, but operable work-related ideas I generated ideas revolutionary to our field I served as a good role model for creativity Psychological Safety (Source: Edmondson, 1999) Members of this organization are able to bring up problems and tough issues People in this organization sometimes reject others for being different (reverse item) It is safe to take a risk in this organization It is difficult to ask other members of this organization for help (reverse item) No one in this organization would deliberately act in a way that undermines my efforts Working with members of this organization, my unique skills and talents are valued and utilized Vitality (Source: Carmeli, in press) I am most vital when I am at work I am full of positive energy when I am at work My organization makes me feel good When I am at work, I feel a sense of physical strength When I am at work, I feel mentally strong Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 30, 785–804 (2009) DOI: 10.1002/job 10991379, 2009, 6, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/job.571 by Feng Chia University, Wiley Online Library on [16/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License VITALITY AND CREATIVITY R. KARK AND A. CARMELI Appendix B: Additional Analyses We also carried out regression analyses to analyze the effect of the control variables on both the mediator (vitality) and dependent variable (creative work involvement). We first regressed the dependent variable (creative work involvement) on all the control variables. The results of this procedure indicated that there was a negative relationship between non-managerial employees and creative work involvement (b ¼ .36, p < .001) and a non-significant relationship between senior-level managers’ creative work involvement (b ¼ .05, p ¼ n.s.), namely that middle-level managers exhibit higher involvement in creative work than either non-managerial employees or senior-level executives. The other control variables (gender, age, tenure, and education) had no significant effect on creative work involvement (b ¼ .06, p ¼ n.s.; b ¼ .08, p ¼ n.s.; b ¼ .16, p ¼ n.s.; b ¼ .12, p ¼ n.s.). Second, we regressed the mediator (vitality) on all the control variables. The results of this procedure indicated that there was a negative relationship between non-managerial employees and vitality (b ¼ .27, p < .01) and a non-significant relationship between senior-level managers’ vitality (b ¼ 05, p ¼ n.s.), namely that middle-level managers reported a higher level of vitality than either non-managerial employees or senior-level executives. The other control variables (gender, age, tenure, and education) had no significant effect on vitality (b ¼ .10, p ¼ n.s.; b ¼ .03, p ¼ n.s.; b ¼ .12, p ¼ n.s.; b ¼ .10, p ¼ n.s.). In addition, we tested a mediation model using regression analyses following Baron and Kenny’s approach. This procedure allowed us to include the control variables in the mediation model. When vitality (the mediator) was specified, we found that the relationship between psychological safety and creative work involvement, though reduced, remained significant (b ¼ .28, p < .01 vs. b ¼ .18, p < .05). In addition, the results indicated that the relationship between vitality and creative work involvement remained significant (b ¼ .37, p < .001. vs. .31, p < .001). The relationship between psychological safety and vitality was also significant (.33, p < .001). Thus, the results indicate a partial mediation model according to which there is both a direct relationship and an indirect relationship (through vitality) between psychological safety and creative work involvement. None of the control variables had a significant effect on creative work involvement ( p > .05). Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 30, 785–804 (2009) DOI: 10.1002/job 10991379, 2009, 6, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/job.571 by Feng Chia University, Wiley Online Library on [16/02/2025]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 804