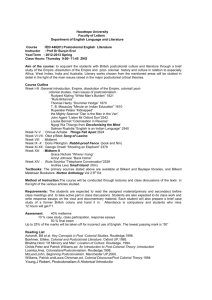

Postcolonial Cold War in Southeast Asia: A Literary Analysis

advertisement