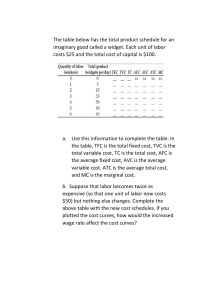

Microeconomics Part 3 – Part 5 Xuebing Yang, PhD ECON 102 AUG-2022 PENN STATE ALTOONA Table of Contents Part 3: Production and Production Costs...................................................................................................... 3 3.1. Introduction to Production ........................................................................................................... 3 3.2. Production-Possibility Frontier ..................................................................................................... 7 3.3. Returns to Scale ............................................................................................................................ 7 3.4. Measuring Costs............................................................................................................................ 9 3.5. Costs in the Short Run ................................................................................................................. 13 3.6. Long-Run Cost Curves ................................................................................................................. 21 Part 4: Market Structures ........................................................................................................................... 23 4.1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 23 4.2. Perfect Competition .................................................................................................................... 25 4.3. Monopoly .................................................................................................................................... 31 4.4. Monopolistic Competition .......................................................................................................... 37 4.5. Oligopoly ..................................................................................................................................... 38 Part 5: Special Topics .................................................................................................................................. 40 5. International Trade ......................................................................................................................... 40 5.1. International Trade Theory ......................................................................................................... 40 5.2. Trade Restrictions ....................................................................................................................... 41 5.3. Overview of Trade in the World ................................................................................................. 43 6. Market Failure ................................................................................................................................. 45 6.1. Non-competitive Markets ........................................................................................................... 45 6.2. Externalities ................................................................................................................................ 46 6.3. Public Goods ............................................................................................................................... 47 6.4. Asymmetric Information ............................................................................................................. 48 2 Part 3: Production and Production Costs 3.1. Introduction to Production §1. In this chapter, we are going to shift our focus to firms. Although it is not our main interest here, we would like to mention that the modern theory assumes that a firm's goal is to maximize its profit. §2. In economics, production refers to the process through which input(s) are transformed into output(s). Production may take the usual form of manufacturing or the form of farming, hunting, writing, teaching, coding, and consulting. In economics, production inputs refer to something necessary for the production process, and production units typically pay to procure. For example, flour is an input for a pizza shop. However, in economics, we would not say “guests are inputs of a hotel,” since the hotel does not pay anyone to buy guests, nor do we say “customers are inputs of a salon” since the salon does not pay anyone to buy customers. On the other hand, production output usually refers to goods or services that a production unit sells to customers to generate revenue. For example, computers produced by Dell are an example of the output. However, we shall avoid saying “Wal-Mart produces jobs” since Wal-Mart does not sell jobs to generate revenue, nor do we say “Intel produces profit” in economics since Intel does not sell profit. §3. Input(s), sometimes referred to as factors of production, are goods or services needed for the production process. Most of the time, we divide inputs into broad categories of labor, intermediate goods, and capital. Labor refers to the time and efforts of workers. In other words, it refers to the service workers provide to the firms. Intermediate goods refer to materials that will be converted to final goods or things that will be consumed during the production process. After the production process, the intermediate goods do not exist in their initial form. For example, after dying, clean water becomes wastewater. Capital refers to land, buildings, machines, etc., which are necessary for production but do not become part of the final goods. An essential feature of capital goods is that they are usually subject to wear and tear (and thus depreciation). Here are two remarks on inputs. First, unlike most intermediate goods, labor and capital are best viewed as services, in the sense that workers and machines “help” the production process, but they do not disappear after the production process. Second, we may hear the term “human capital” from time to time, which usually refers to important abilities that constitute a firm’s core competence. In economics, however, all human efforts are categorized as labor, not capital. Intermediate good suppliers, ordinary employees (i.e., suppliers of ordinary labor), and creditors that supply capital in the form of debts will receive fixed payments specified in their contracts with the firm. Suppliers of equity and entrepreneurship (special labor) usually take what is left over after everyone else is paid. These factor suppliers are called residual claimants, and they are usually owners of the firms. The residual claimants are the bearers of business risks and are typically rewarded for the risk-bearing function. They are willing to be residual claimants either because they have the financial ability to bear the risks, their assets are more firm-specific than other inputs, or because they have a better knowledge of the risks. §4. In economics, technology refers to how input(s) are transformed into output(s), or in other words, the techniques that we use to finish a task. A technology is simply a method to complete a task. It does not have to be complicated or advanced. Actually, many times, a simpler technology may be a better technology since it requires less training of workers. Now we know that any production activity involves three aspects: input(s), production technology, and output(s). §5. A production technology has many aspects. In economics, we are most interested in the maximum amount of output that a technology can produce with the given inputs. We use a production function to describe this relationship. Take the production of mixed concrete as an example. Let 𝑄 denote the output, measured in pounds. Let 𝐶 denote the weight of cement and 𝑊 denote the weight of water, then 𝑄 = 𝐶 + 𝑊 can be used as the production function to describe the production process of mixed concrete. Remember that the production function abstracts from plenty of details and can only be viewed as an approximation of the actual production process. A production function represents a production technology. It describes what is technically feasible when the firm operates efficiently. 3 Question-1. According to the text, are students a production input for Penn State Altoona? Why or why not? Question-2. What is (are) the output(s) of the following organizations? • Intel • A hospital • Penn State Altoona • Wal-Mart Question-3. Consider the inputs of a typical automotive repair shop. a. Name some inputs of it. Identify the category it belongs to. b. Is a wrench an intermediate good or a capital good? Why? Question-4. What is the technology that you use to make sure that you remember deadlines and important events? 4 §6. Productivity is a measure of the efficiency of the production process. It is a ratio of output to a single input or all inputs. When productivity is computed as the ratio of output to a single input, it is partial productivity. The most popular partial productivity is labor productivity. 𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑜𝑢𝑡𝑝𝑢𝑡 𝐿𝑎𝑏𝑜𝑟 𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑑𝑢𝑐𝑡𝑖𝑣𝑖𝑡𝑦 = 𝐿𝑎𝑏𝑜𝑟 𝑖𝑛𝑝𝑢𝑡 Labor productivity is also the average product of labor. Suppose the Total output of a plant is 45 units when the labor input is 9 units, then the average output (Q) output of labor is 45/9=5 units. On a graph of total output, the average product of an input is the slope of the line that connects a point on the total output 46.4 curve and the origin. MPPL=slope 45 Labor productivity will increase when the firm uses more capital per unit =(46.4-45)/0.2=7 of labor (e.g., better equipment), gives employees more training, or adopts better management practices and technologies. APL=45/9=5 When productivity is computed as the ratio of output to all inputs, it is total productivity. For example, suppose the production function of a firm is 9 9.2 L 𝑄 = 𝑎𝐿0.5 𝐾 0.5 , where 𝐿 is labor input and 𝐾 is capital input. The parameter 𝑎 indicates the firm’s total productivity. Suppose parameter 𝑎 equals 1 initially. When 𝑎 increases to 1.1, a given combination of labor and capital will produce an output that is 1.1 times the initial output. The total productivity of the firm increases by 10%. §7. A production process usually takes many inputs. It takes very little time to get more of some inputs, such as water and electricity if the firm has the money. However, it takes much longer to get other inputs, such as big machines and buildings. If it is impossible for a firm to change the amounts of all inputs within a given period, then the period is said to be the short run. If the quantity of an input can be changed in the short run, then it is a variable input. Otherwise, it is a fixed input. The quantity of variable input changes as the output changes; the amount of fixed input does not vary with the output level. If a period is long enough so that a firm can change the quantities of all inputs, then we say it is the long run. §8. Suppose the output of a plant is 45 units when the labor input is 9 units. Suppose the output will increase to 46.4 if the labor input increases by 0.2, then we see that at the current output level, an additional unit of labor 46.4−45 will increase the physical output by = 7 units. We refer to this measure as an input's marginal physical 0.2 product or marginal product. It measures the increase in the physical output when an additional unit of the Δ𝑄 input is used, and it is calculated as 𝑀𝑃𝑃𝑋 = . Note that the average product is not necessarily equal to its Δ𝑋 marginal product. §9. In the real world, most of the time, a factor will eventually exhibit diminishing marginal physical product. In other words, we say that a factor has decreasing returns (or diminishing marginal returns). Note that when we say a factor has decreasing returns, we are referring to cases in which we only change one input while keeping all other inputs constant. Therefore we are talking about the short run. A related observation is that the marginal product of an input increases initially. This is often explained as the effect of learning by doing, or synergy. However, as the input increases, these beneficial effects will be dissipated, and the K diminishing marginal returns will dominate. §10. Firms can usually use different input bundles to achieve the same 12 output level. For example, a farm can choose to hire a lot of workers to harvest the crops by hand (large L, small K), but it can also choose 8 to hire just a few workers and use a very advanced combine harvester (small L, large K) to finish the same job. The collection of all input 6 bundles that produce the same output from an isoquant. For example, let us consider a not-very-realistic but 4 mathematically easy production function 𝑄 = 𝐿 ∙ 𝐾. Suppose the 2 firm’s current input bundle is (𝐿 = 4, 𝐾 = 3). If we find a few other bundles that give the same output and connect them with a smooth curve, we get an isoquant that passes the input bundle (𝐿 = 4, 𝐾 = 3). 0 5 2 4 6 8 10 12 L Question-5. The period in which there are no fixed costs is the: A: Short run. B: Implicit run. C: Long run. Question-6. In economics, the long run is: A: More than two years. B: Six to nine months. D: A variable time depending on the nature of business. Question-7. The slope of the total product curve is the A: slope of a line from the origin to the point. C: marginal rate of technical substitution. D: Production run. C: One year. B: marginal product. D: average product. Question-8. A firm’s output is 60 when it employs 15 units of labor. If it increases its labor input by 0.1, its output level will increase to 62. a. Find the average product of labor at the current output level (i.e., before it increases its labor input). b. Find the marginal physical product of labor at the current output level. Explain what the answer means. Question-9. The law of diminishing returns refers to diminishing A: total returns. B: marginal returns. C: average returns. Question-10. Please fill out the following table. Capital Number Total output of workers An unknown amount. Kept constant in this example 1 2 3 4 5 6 D: profit of the firm Marginal product of Labor Average product of labor 8 20 36 48 55 60 Question-11. An isoquant A: must be linear. B: cannot have a negative slope. C: is a curve that shows all the combinations of inputs that yield the same total output. D: is a curve that shows the maximum total output as a function of the level of labor input. E: is a curve that shows all possible output levels that can be produced at the same cost. Question-12. A straight-line isoquant indicates that A: two inputs must be used in a fixed proportion B: the firm can only have one output level C: the firm should use more capital and less labor D: two inputs are perfect substitutes in production. 6 3.2. Production-Possibility Frontier §11. Between 1936 and 1942, Hermann Göring (1893-1946) was charged by Hitler with the task of preparing Germany for the Nazi’s imperial ambitions. During this period, Göring adopted the wellGuns Butter known but disastrous policy proposed by Rudolf Hess, “guns before butter.” In other words, 0 5 Göring chose to produce more guns and less butter. Why did Germany have to produce less 1 4.9 butter when it decided to produce more guns? The answer is that its resources were limited. If Germany produced a given amount of guns, then there would be a limit on the amount of 2 4.6 butter it could make. 3 4.2 Let us make up some numbers to better describe the possible output combinations given 4 3.2 the resources. The table shows the maximum amount of butter that Germany can produce 5 0 when it chooses to produce different amounts of guns. These numbers may not be very realistic, but they describe a pattern: if more resources are allocated to one good, then fewer resources can be allocated to the other good. Butter If we plot these numbers on a graph, we get the following curve, which we refer to as a production possibility frontier with the 5 standard acronym PPF. A production-possibility frontier shows the 4 possible output combinations of two goods given the resources, provided that the economy is operating efficiently. You can also say 3 that it shows the maximum output of one good given different output 2 levels of the other good when the amount of resources is fixed. 1 §12. Here are some remarks on the PPF: • If an economy is on its PPF, it is operating efficiently. 0 1 2 3 4 5 Guns • A point on the PPF is efficient, but it is not necessarily optimal. For example, in the above example, the output combination (5 guns, 0 butter) is very unlikely to be an optimal choice for Germany. • Output combinations within the PPF are possible, although they do not represent the most efficient output. For example, the combination (1 gun, 3 butter) is possible, but it is inefficient compared with the output combination (1 gun, 4.9 butter). • The butter that must be given up to produce additional guns is called the opportunity cost of the additional guns. Likewise, we can define the opportunity cost of butter. • In the real world, most PPFs are bowed outward (i.e., concave). In other words, as more guns are produced, each additional gun requires the economy to give up more butter; as more butter is produced, each additional unit of butter requires the economy to give up more guns. This pattern is called the law of increasing opportunity cost. 3.3. Returns to Scale §13. Suppose financing is not an issue, then how large should a firm be? Should it choose to be a small firm or a large firm? This is a question about the scale of a firm. To discuss questions concerning optimal scales, we first need to discuss returns to scale. Suppose a firm doubles all of its inputs, which means that it doubles its amount of machines, buildings, workers, and intermediate goods. In other words, the firm simply duplicates itself, or the scale of the firm doubles. If the new output is more than double the initial output, the production technology exhibits increasing returns to scale. It means that the output is sensitive to the changes in the amount of input. A one-percent change will lead to more than one percent of change in the output. Analogously, if the new output level is less than twice the initial output, the production technology exhibits decreasing returns to scale. If the new output level is exactly twice the initial one, then we say there are constant returns to scale. Suppose a production technology is represented by the production 𝑄 = 𝑥1 + 𝑥2 , where 𝑄 is the output, 𝑥1 and 𝑥2 are the amounts of two inputs. Suppose we want to find out whether the production technology exhibits increasing, decreasing, or constant returns to scale. Consider an arbitrary input bundle (1, 1). This bundle will result in an output level of 𝑄𝑂𝑙𝑑 = 𝑥1 + 𝑥2 = 1 + 1 = 2. If we double the inputs, we have a new bundle (1,1) × 2 = (2,2). Given the new input bundle, the output would be 𝑄𝑁𝑒𝑤 = 2 + 2 = 4. 𝑄 4 Since the new output is 𝑁𝑒𝑤 = = 2 times the initial one, the technology exhibits constant returns to scale. 𝑄𝑂𝑙𝑑 2 7 Question-13. Let us define our output in each class as the examples we discuss and the exercise questions we finish. The following table gives the highest possible combinations of these two outputs for a typical class of this course (average quantities). a. Use them to draw a PPF. b. Find the opportunity cost for each example. For example, how many exercises do we need to give up if we increase the number of examples from 0 to 1? Examples Exercises 0 5.0 1 4.6 2 4.0 3 3.2 4 1.8 5 0.0 Opportunity Cost of each example Exercises 5 * 4 3 2 1 0 1 2 3 4 5 Examples Question-14. The production possibilities curve illustrates that: A: Society can always produce more of all goods simultaneously. B: Constant opportunity costs always exist. C: There are no opportunity costs in a wealthy economy. D: If society is efficient, it can produce more of one good only if it reduces the output of another good. Question-15. According to the law of increasing opportunity costs: A: Greater production leads to greater inefficiency. B: Greater production means factor prices rise. C: Greater production of one good requires increasingly larger sacrifices of other goods. D: Higher opportunity costs induce higher output per unit of input. Question-16. (Mini-essay) A production technology is represented by the production function 𝑄 = 𝑥1 × 𝑥2 . Find out whether the production technology exhibits increasing, decreasing, or constant returns to scale. • Refer to §13 for help. 8 §14. You may have heard of the term economies of scale. It refers to the decrease in average cost when the output level increases. Economies of scale are closely related to returns to scale, but some differences exist. The economies of scale are about how the average costs vary with the output level, while returns to scale are about how the output level changes when all inputs change by the same percentage. The economies of scale could be referring to either a short-run or long-run phenomenon, but the returns to scale are always about the long-run relation since it requires all inputs to change. Economies of scale can arise from sharing fixed costs by more units of output (short-run). Economies of scale can also arise from increasing returns to scale when a firm increases all inputs (long-run). 3.4. Measuring Costs §15. In economics, we assume a firm’s goal is to maximize its profit. The profit of a firm is the difference between its revenue and costs, i.e., 𝜋 = 𝑅 − 𝑇𝐶, where 𝜋, 𝑅, and 𝑇𝐶 are its profit, the revenue, and the total costs (sometimes we use 𝐶 to denote the total cost). Since 𝜋 = 𝑅 − 𝑇𝐶, managers are always thinking about how to maximize their revenue while minimizing their costs. In this chapter, we will focus on the cost of a firm. §16. Here is a very basic and yet important question: What counts as a cost? Economists think that a cost is incurred whenever an input is used in a production activity because the input probably cannot be used for other purposes now (unless the input is non-exclusive). In other words, the firm costs the owner of the input the opportunity to use the input for other purposes. Here is a simple example that will hopefully give us a rough idea of what constitutes a cost. Spring House Grille is a restaurant that serves traditional American food. The owner bought it for $3 million and hired a manager to run it. The restaurant owns the building, the cooking equipment, and the furniture. Last year, it spent $2 million on labor (including the manager’s labor), food ingredients, utilities, office supplies, insurance, and all other goods and services that the restaurant purchased for its operation during last year. Last year, Spring House Grille’s total revenue was $2 million. Few of us would feel that the restaurant’s performance was satisfactory last year. The $2 million revenue took care of all the inputs that the restaurant bought from other parties, but there is nothing left to compensate for the inputs owned by the restaurant, such as the building, the cooking equipment, and the furniture. When Spring House Grille was using these inputs, they could not be used for other purposes, so they constituted a cost. We need to include them in our calculations when we evaluate the restaurant’s profitability. §17. In economics, an explicit cost refers to a direct payment made to others for using an input. Examples of explicit costs include wages paid to hired workers, rents paid to landlords, and expenditures on materials paid to suppliers. Explicit costs are also called accounting costs because they are usually the only costs that will be recognized by accounts in their reports. Accountants only recognize explicit costs because their reports must be objective and verifiable, and explicit costs can be backed up back evidence like receipts. The account costs may not be all-inclusive, but for the part they are meant to gauge, they are appropriate measures. Sometimes, an input is used without any explicit payments being made. The opportunity cost of using this input is called the implicit cost. For example, in the above example about Spring House Grille, the business was using its own building, cooking equipment, and furniture. Had it needed to rent these inputs from someone else, the restaurant would have to pay rent for them. The market price of using these inputs is the magnitude of the associated implicit cost. The sum of explicit costs and implicit costs is referred to as the economic cost. Ideally, we should use the economic cost as the cost measure since it includes all costs, but it is difficult to measure or verify the implicit cost. Due to the elusiveness of implicit costs, accounting reports usually do not include them. The difference between the revenue and the account cost is called the accounting profit. The accounting profit is the reward for the owner’s inputs. The difference between the revenue and the economic cost is the economic profit. §18. Here are a few formulas that summarize what we learned: 𝐸𝑥𝑝𝑙𝑖𝑐𝑖𝑡 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡𝑠 = 𝐶𝑜𝑠𝑡𝑠 𝑤𝑖𝑡ℎ 𝑑𝑖𝑟𝑒𝑐𝑡 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑒𝑥𝑝𝑙𝑖𝑐𝑖𝑡 𝑝𝑎𝑦𝑚𝑒𝑛𝑡𝑠 𝐼𝑚𝑝𝑙𝑖𝑐𝑖𝑡 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡𝑠 = 𝐶𝑜𝑠𝑡𝑠 𝑡ℎ𝑎𝑡 𝑎𝑟𝑒 𝑛𝑜𝑡 𝑎𝑐𝑐𝑜𝑚𝑝𝑎𝑛𝑖𝑒𝑑 𝑏𝑦 𝑑𝑖𝑟𝑒𝑐𝑡 𝑝𝑎𝑦𝑚𝑒𝑛𝑡 𝐴𝑐𝑐𝑜𝑢𝑛𝑡𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡𝑠 = 𝐸𝑥𝑝𝑙𝑖𝑐𝑖𝑡 𝐶𝑜𝑠𝑡𝑠 𝐸𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑜𝑚𝑖𝑐 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡𝑠 = 𝐸𝑥𝑝𝑙𝑖𝑐𝑖𝑡 𝐶𝑜𝑠𝑡𝑠 + 𝐼𝑚𝑝𝑙𝑖𝑐𝑖𝑡 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡𝑠 𝐴𝑐𝑐𝑜𝑢𝑛𝑡𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑓𝑖𝑡 = 𝑅𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑛𝑢𝑒 − 𝐴𝑐𝑐𝑜𝑢𝑛𝑡𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡𝑠 𝐸𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑜𝑚𝑖𝑐 𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑓𝑖𝑡 = 𝑅𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑛𝑢𝑒 − 𝐸𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑜𝑚𝑖𝑐 𝐶𝑜𝑠𝑡𝑠 9 Question-17. Oscorp is a company that manufactures bearings. It owns $100 million of assets, which includes plants, patents, vehicles, etc. Had Oscorp rented these assets, it would need to pay $7 million a year. Oscorp pays its employees $10 million of wages and salaries a year. Each year, it uses $20 million dollars of intermediate goods. It also pays $1 million of yearly interest for the loans it takes out (principal: $10 million). It has an annual revenue of $36 million. a. Fill out the table on the right. Explicit cost or Inputs Yearly cost b. Please find the accounting profit of Oscorp. Use implicit cost? the result to evaluate Oscorp’s profitability. Oscorp’s own capital External capital (loans) Labor of employees Intermediate goods c. Please find the economic profit of Oscorp. Use the result to evaluate Oscorp’s profitability. d. Who receives the accounting profit in this case? What is their contribution to the production process that justifies their claim of the accounting profit? Question-18. Joe owns a firm with a large capital stock, such as machines and facilities. People would pay $3 million annually to use these machines and facilities. Joe himself is a good manager. People would pay $0.5 million a year to hire him to manage a firm. Joe decides to run the firm himself. It turns out that each year the firm needs to pay $4 million of wages to the employees (not including Joe himself) and $2 million for intermediate goods. The yearly revenue of the firm would be $10.2 million. Joe will not make explicit payments to himself for using his own capital and labor used for the business. a. Fill out the table on the right. Explicit cost or b. Please find the accounting profit of Joe’s firm. Use the Inputs Yearly cost implicit cost? result to explain whether Joe should run the firm Capital himself or rent it out and work elsewhere. Joe’s labor Labor of employees Intermediate inputs c. Please find the economic profit of Joe’s firm. Use the result to explain whether Joe should run the firm himself or rent it out and work somewhere else. Economic profit Question-19. Use the new terms we learned to fill the following blanks. a. Accounting costs = ________________________. b. Economic costs = _____________ + ____________. c. Accounting profit = ___________ – ____________. d. Economic profit = ____________ – _____________ = __________ – ( _____________ + ____________) e. Accounting costs are ______ Economic costs (>,=,or<). f. Accounting profit is ______ Economic profit (>,=,or<). g. Economic costs – Accounting costs = ___________. h. Accounting profit – Economic profit = __________. 10 E C O N O M I C C O S T S Accounting profit Implicit costs Revenue Accounting costs Accounting costs AKA, explicit costs AKA, explicit costs §20. Some of us may be a little confused with the concept of economic profit, most likely because we are used to the view that takes profit as the total reward for the owner’s inputs. For these students, maybe it helps to view economic profit as “abnormal profit” or “supernormal profit.” Consider a “pizza-buying” project. Let us take money as the “input” for this project. On the market, we can get a slice of pizza for $1. In other words, the market return to $1 is a slice of pizza. Steve would like to have just one slice of pizza, but the pizza shop says that one must If each of us gets a piece, there Why should we worry buy at least eight slices at a time. Steve talks to seven people will be no pizza left. I feel that as long as each of us and asks each of them to chip in $1 and promises each of them will be a problem. gets what we are supposed to get? a slice of pizza. This is similar to the case when a boss asks people to contribute labor to her firm and promises to pay them some wages. After Steve gets the eight-slice pizza, he gives each of the seven partners a slice. There is a slice left for him, which is the return to the dollar he contributes. In this case, Steve is the last person to get his returns for his input (the dollar he chips in), so he is called the residual claimant. We find that after everyone gets what they could get with their input (money) on the market, there is nothing left. Therefore the “economic profit” of this pizza-buying project is zero. The concept of “zero economic profit” would not raise any alarm in this case because it simply means every input owner gets what they could get on the market. When a firm has zero economic profit, we say the firm is earning a normal profit. §21. In economics, sunk costs are costs that have already been incurred and cannot be recovered. For example, suppose Joe decided to run a farm. To do that, he paid $2000 to attend some workshops and spent $3000 on traveling to look for a suitable farm. These costs are necessary and useful, but there is no way that Joe can reverse the process or resell the inputs to get the money back. Therefore, they are sunk costs. Suppose he paid $500K to buy a farm that he liked best. Since he could sell the land and get the money (or at least part of the money) back, this $500K should not be counted as a sunk cost. §22. It is necessary to clarify the relation between sunk costs, fixed costs, and variable Don’t cry over spilt milk, costs. A sunk cost might be part of the fixed cost or variable cost. Consider an because it’s a sunk cost. automobile factory. The costs spent on machines and plant blueprints are both fixed costs, but the former can be partially recovered by reselling the furniture (not sunk costs) while the latter cannot be recovered (a sunk cost). The electricity and the steel used to make cars are both part of the variable costs, but the former is a sunk cost while the latter can be partially recovered. §23. When we are halfway through a project, there is nothing we can do about the sunk cost, so we can simply ignore the sunk cost and only compare the future benefit and the future cost to decide whether to continue the project. If the future benefit is greater than the future cost, then we should continue the project, and vice versa (the future benefit of abandoning the project = the cost of abandoning the project = $0). Of course, some of us may be curious about how we should make a decision if we insist on taking sunk costs into consideration. Well, we can definitely do that, but we should incorporate the sunk in our calculations in the right way. To do so, we can calculate the economic profit of continuing and abandoning the project, respectively, and then see which decision yields a better outcome. 11 Question-20. (Mini-essay) Consider Steve mentioned in §20. Suppose he spent a few minutes online and found a deal: an eight-slice pizza for $7 dollars. He asked seven people to chip in $1 each and used that money to buy pizza. He used the $7 he raised to buy an eight-slice pizza. After he gave each partner a slice, a slice was left for him. This time, he got a slice of pizza without contributing any money. a. What is Steve’s input in this pizza-buying project? b. What are the returns to his input? • No close example. • The solution is supposed to be a mini-essay. It should be at least as detailed as the sample solution, if there is one. Please relegate long calculations to scratch paper. Please try to use your own words. Question-21. The following diagram shows the supply of factors and the costs associated with them from a macroeconomic view. a. Which party in the diagram receives Firm A’s accounting profit? b. Suppose Firm A’s annual economic profit is $1 million. If the firm is shut down, how would that affect the total value created in the economy in a year? Assume the released inputs will instantly be used for other production activities without reallocation costs. Capital (money used to get buildings and machines, though stocks markets or banks) Final goods Labor Wages Revenue for Firm A Immediate goods Other firms Firm A Payments Question-22. Tim heard about a massive sale for used tools in another town, so he drove an hour to get there. He got a ticket for speeding because he was so excited about the sale. When he finally got to the sale, however, he found all the used tools were overpriced. In fact, they were all twice the prices of new ones that Tim could readily purchase at a store near his house. a. What are the sunk costs for Tim in this case? b. Should Tim buy some of the overpriced used tools? How should the sunk cost(s) affect his decision? c. Supposedly, Tim may buy some over-priced used tools. What are the possible reasons? 12 Are you throwing good money after bad? §24. Let us use an example to illustrate the above theory. After spending $1 billion to prospect an oil field, a petroleum company finds that it can extract $2 billion of crude oil from the field if it spends another $1.5 billion on drilling costs. Now the company needs to decide whether to go ahead and continue the project or to abandon it. Suppose the firm cannot sell the information it gathered during the prospecting process. a. Find the sunk cost of the project. The sunk cost of the firm is the $1 billion spent on prospecting since there is no way the firm can recover it. b. Discuss if the firm should continue the project by ignoring the sunk costs. When deciding whether to continue the project, we can simply compare the future benefit and the future cost. In this case, the future benefit ($2 billion of revenue) is greater than the future cost ($1.5 billion of drilling cost), so the project should be continued. c. Some people doubt the above conclusion drawn by ignoring the sunk costs. They insist on considering the sunk costs. So please find the economic profit of continuing and abandoning the project, and then identify the best decision. If the firm continues the project, the economic profit would be 𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑏𝑒𝑛𝑒𝑓𝑖𝑡 𝑜𝑓 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑗𝑒𝑐𝑡 − 𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡 = $2𝑏 𝑜𝑓 𝑟𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑛𝑢𝑒 − ($1𝑏 𝑓𝑜𝑟 𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑠𝑝𝑒𝑐𝑡𝑖𝑛𝑔 + $1.5𝑏 𝑓𝑜𝑟 𝑑𝑟𝑖𝑙𝑙𝑖𝑛𝑔) = $ − 0.5 𝑏. If the firm abandons the project, the economic profit would be 𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑏𝑒𝑛𝑒𝑓𝑖𝑡 𝑜𝑓 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑗𝑒𝑐𝑡 − 𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡 = $0 − $1𝑏 𝑓𝑜𝑟 𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑠𝑝𝑒𝑐𝑡𝑖𝑛𝑔 = $ − 1𝑏. Since the economic profit of continuing the project is higher, the firm indeed should continue the project. $1.5b of drilling $1b of prospecting Note that if the company could go back in time, it would avoid the project in the first place ($2.5b of cost vs. $2b of $2b of revenue revenue), which involves avoiding the $1b prospecting cost. However, the problem is that no one can go back in time and Past Future recover the sunk cost. Time to decide whether to continue the project 3.5. Costs in the Short Run 3.5.1. Costs in the Short Run §25. When we analyze a firm’s cost structure in the short run, it is helpful to divide the total cost into fixed and variable costs. Fixed costs (denoted with FC) are the costs that remain invariant to the output. Consider a restaurant. Its fixed costs include the rent it pays for the building, and the expenditure on furniture and cooking appliances. Fixed costs may be taken as the costs to get a firm ready for production. The variable costs (denoted with VC) are the costs that vary with the output. If the restaurant sells more food, it will need to hire more employees, buy more raw materials, and use more water and Q FC VC TC MC AFC AVC ATC electricity. These expenditures are the variable costs of the restaurant. 0 6 0 6 * * * * TC = FC + VC 1 6 3 9 3 6 3 9 If we divide FC, VC, and TC by the output level, we will have the 2 6 5 11 2 3 2.5 5.5 average fixed cost (AFC), average variable cost (AVC), and average total 3 6 6 12 1 2 2 4 cost (ATC): 4 6 8 14 2 1.5 2 3.5 5 6 11 17 3 1.2 2.2 3.4 ATC = TC/Q AFC=FC/Q AVC=FC/Q 6 6 15 21 4 1 2.5 3.5 The table on the right shows the various costs of a firm. The fixed 7 5 cost is the total cost when the firm has not produced anything yet. The TC column equals the sum of the FC column and the VC column. §26. We often use a cost function to show the minimum cost that a firm takes to produce a given amount of output. For example, a firm’s cost function may be 𝑇𝐶(𝑄) = 3.5𝑄2 + 2𝑄 + 12. It means that if the firm wants to produce 𝑄 units of output, it will take 3.5𝑄2 + 2𝑄 + 12 dollars. Note that 𝑇𝐶(𝑄) reads “the total cost when the output level is 𝑄.” It does not stand for 𝑇𝐶 × 𝑄. If we know the cost function of a firm, we can find its fixed and variable costs at a given output level. Its fixed cost is simply its total cost when the output is zero since its FC is the cost to get it ready to produce. For the firm mentioned above, its FC is 𝐹𝐶 = 𝑇𝐶(0) = 3.5 ∗ 02 + 2 ∗ 0 + 12 = 12. Its variable cost is the rest of the cost function, which is 𝑉𝐶(𝑄) = 3.5𝑄2 + 2𝑄. If we know the current output level, we can plug it in 𝑉𝐶(𝑄) = 3.5𝑄2 + 2𝑄 and find the exact value of the variable costs. For example, suppose we know that the firm’s current output is 10, then 𝑉𝐶 = 3.5𝑄2 + 2𝑄 = 3.5 ∗ 102 + 2 ∗ 10 = 375. 13 Question-23. (Mini-essay) Ben just finished his second year of college. He wants to know if he should quit college. His college education has costed him $40k so far. He needs another $45k to graduate. If he gets a college degree, his lifetime income would be $80k higher than otherwise (i.e., that’s the future benefit of finishing the college education). For simplicity, we assume that he would not work if he is not going to college. a. Find the sunk cost of Ben’s college education project. b. Discuss if he should continue his college education by ignoring sunk costs. c. Some people may doubt the above conclusion drawn by ignoring the sunk costs. They insist on considering the sunk costs. So please find the economic profit of continuing and abandoning the project, respectively, and then identify the best decision. • • See §24 for help. The solution is supposed to be a mini-essay. It should be at least as detailed as the sample solution, if there is one. Please relegate long calculations to scratch paper. Please try to use your own words. Question-24. Use the new terms we just learned to finish the following identities. TC= ___________________ + _____________________ FC=____________________ − _____________________ VC=____________________ − _____________________ ATC= ___________________ + _____________________ AFC=____________________ − _____________________=_____________ / _______________ Question-25. Firm A’s cost function is 𝑇𝐶(𝑄) = 2𝑄2 + 3𝑄 + 40. The output level is 𝑄 = 10. Find the follows costs at this output level (10 in the following parentheses indicates the output level). (a) 𝑇𝐶(10) (b) 𝐴𝑇𝐶(10) (c) 𝐴𝐹𝐶(10) (d) 𝐴𝑉𝐶(10) 14 §27. The marginal cost measures how fast the cost increases as the output increases. In symbols, it is defined as 𝑀𝐶 = Δ𝑇𝐶/Δ𝑄. Although the change in 𝑄 is supposed to be infinitely small, in introductory economic classes, we usually relax this requirement. Suppose it took Taylor Swift $2,000,000 to get her new album ready (her own labor, her manager’s labor, background singers, recording, editing, etc.). Let us call this the fixed cost of the new album. It took $250,000 to make the first million discs of the new album, which we call the variable cost. Consequently, the total cost of producing 1 million copies of CD’s is TC(1,000,000)=FC+VC= $2,000,000+$250,000=$2,250,000. If she decides to make an additional thousand discs, the variable cost will increase by $250. That is, TC(1,001,000)=$2,250,250. At the output of 1 million discs, the marginal cost is Δ𝑇𝐶 $2,250,250 − $2,250,000 $250 𝑀𝐶 = = = = $0.25/𝑑𝑖𝑠𝑐. Δ𝑄 1,001,000 − 1,000,000 1000 The result means that at the current output level, it takes another $0.25 to produce an additional copy of the album. TC §28. We need to keep in mind that MC is different from ATC. Roughly speaking, MC tells us how much it takes to produce the next unit of output, while ATC tells us how much it takes to produce each of the units that have been produced on average. These two numbers are not necessarily the same. For example, in Taylor Swift’s example, the ATC is $2,250,000/1,000,000 = $2.25/disc, while the MC is $0.25/disc. In this case, the main reason for the big difference is that the fixed cost does not enter the calculation of the MC at all. Even if the fixed cost is zero, however, the variation in the marginal cost can still cause a divergence between ATC and MC. Cost 𝑀𝐶 = Δ𝑇𝐶 Δ𝑄 TC1 FC ATC=TC1/Q1 Output Q1 §29. On a graph, the average cost is the slope of the line that connects the origin and a point on the total cost curve; the marginal cost is the slope of the total curve at the output level in question. The flattest point on the TC curve corresponds to the output level with the lowest MC. §30. The marginal cost curve usually takes a U shape in the real world. The marginal cost first decreases then increases. It falls at first because of learning by doing and specialization of labor. Eventually, it becomes progressively challenging to produce each additional unit, so the marginal cost increases. The increase in marginal cost is due to diminishing marginal return. Cost MC Output §31. When a firm is producing 9 units of product, its ATC is 15. It would take another 20 dollars to produce an additional unit (i.e., the 10th unit). Find the firm’s new average total cost (i.e., ATC(10) after it makes the additional unit. To find ATC(10), we just need TC(10) since ATC(10)=TC(10)/10. How do we find TC(10)? Well, if we can find TC(9) and add it to the marginal cost of producing the 10th unit, we get TC(10). Here is a sample solution: When producing 9 units of output, the firm’s total cost is 𝑇𝐶(9) = 𝐴𝑇𝐶(9) ∗ 𝑄 = 15 ∗ 9 = 135. If the firm produces another unit, i.e., Q=9+1=10, the total cost would be 𝑇𝐶(10) = 𝑇𝐶(9) + 𝑀𝐶 = 135 + 20 = 155. Since ATC(Q)=TC(Q)/Q, the new ATC becomes 𝐴𝑇𝐶(10) = 𝑇𝐶(10)/10 = 155/10 = 15.5. 15 Question-26. The following table shows some information about the costs of a firm. Please fill out the table. Output Variable Cost Fixed Cost 0 0 10 1 10 2 17 3 25 4 40 5 60 6 110 Total Cost Marginal Cost AVC AFC ATC Question-27. (Mini-essay) When a firm is producing 7 units of product, its ATC is 15. It would take another 10 dollars to produce an additional unit (i.e., the 8th unit). Find the firm’s new average total cost after it produces the additional unit. • See §31 for help. 16 3.5.2. Short-run Cost Curves §32. Here are the properties of short-run cost curves. Cost TC and VC: TC o These two curves are both upward sloping and have the same shape, except that the TC curve is above the VC curve. The TC curve is above the VC curve since VC TC=FC+VC. o The vertical distance between the TC curve and the VC curve equals the fixed cost since 𝐹𝐶 = 𝑇𝐶 − 𝑉𝐶. o The vertical distance between the TC and VC curves remains invariant to the output level. o The TC and the VC curves will eventually be increasingly steep since it takes additional costs to FC AFC produce another unit as the output level increases. AFC: Since AFC=FC/Q, the AFC decreases with Q, and the Output corresponding curve is downward-sloping. ATC and AVC: o The ATC and the AVC curves are both U-shaped curves. Cost o The ATC curve is above the AVC curve since 𝐴𝑇𝐶 = MC 𝐴𝑉𝐶 + 𝐴𝐹𝐶. The vertical distance between these two ATC Lowest point curves equals the AFC, since 𝐴𝐹𝐶 = 𝐴𝑇𝐶 − 𝐴𝑉𝐶. of ATC o Note that AFC decreases with Q, so the distance between the ATC and the AVC curve should get smaller as Q AVC increases. o However, the ATC curve and the AVC curve shall never be concurrent since ATC is always greater than AVC. o In other words, the ATC curve and the AVC Lowest point asymptotically approach each other, meaning they get of AVC infinitely closer to each other but never intersect. MC: o The marginal cost curve should eventually be upward Output sloping because it will ultimately become more and more difficult to produce an additional unit of product (if some inputs are fixed). o Another feature of the MC curve is that it crosses the ATC and the AVC curves at their respective lowest point. 3.5.3. The Average-Marginal Relationship §33. Suppose your quiz grade for a class is the average of all the quizzes that you take. You have taken 3 quizzes, and your grades are 8, 9, 10 (out of 10). Your current average quiz grade is thus (8+9+10)/3=9. Now suppose you take the 4th quiz, and your grade turns out to be 10, i.e., the marginal value is 10. If we calculate the new average, we will find that it increases (9.25). Our intuition tells us that if the marginal value is greater/less than the average value, the additional unit causes the average value to increase/decrease. This rule is called the average-marginal rule. The rule applies to any situation. It does not matter if we are talking about grades, costs, wealth, or anything else. The above rule applies as long as we can calculate the average value. We said that the average-marginal rule applies to anything for which we can define an average value and a marginal value. Therefore, we can apply it to costs. To be specific, if MC>ATC, then the additional output will cause ATC to increase; if MC<ATC, then the additional output would cause ATC to decrease. 17 Question-28. The following table shows the fixed cost and the marginal cost of a firm given various output levels. a. Fill out the table. b. Use the data to draw the FC, TV, and VC curves on the first graph. c. Use the data to draw the MC, ATC, AVC curves on the second graph. Output 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 FC 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 MC * 5 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 TC 3 8 10 11 13 16 20 25 31 38 46 55 VC 0 5 7 8 10 13 17 22 28 35 43 52 ATC * 8.00 5.00 3.67 3.25 3.20 3.33 3.57 3.88 4.22 4.60 5.00 AVC * 5.00 3.50 2.67 2.50 2.60 2.83 3.14 3.50 3.89 4.30 4.73 10 60 9 50 8 7 40 6 5 30 4 20 3 2 10 1 0 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 11 2 3 4 5 FC TC 6 7 Output Output MC VC 18 ATC AVC 8 9 10 11 §34. Consider the following scenario: Suppose a firm’s current output level is 𝑄 = 4 and the ATC is 𝐴𝑇𝐶(4) = $10/𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑡. It would take another $8 to produce an additional unit of output, i.e., 𝑀𝐶 = 8. a. Use the average-marginal rule to predict how the ATC would change when another unit is produced on top of the Cost current 4 units. Here is a sample solution: MC The marginal cost is 8, while the ATC(4) is 10, so ATC 𝑀𝐶 < 𝐴𝑇𝐶. According to the average-marginal rule, ATC(4)=10 producing another unit will decrease the ATC. ATC(5)=9.6 b. Find ATC(5) and compare it with ATC(4). Does the ATC increase or decrease when another unit is produced? Is the result consistent with the prediction of the average MC(4)=8 marginal rule? Here is a sample solution: When producing 4 units of output, the total cost is 𝑇𝐶(4) = 𝐴𝑇𝐶(4) ∗ 𝑄 = 10 ∗ 4 = 40. 4 5 Output If the firm produces another unit, the total cost would be 𝑇𝐶(5) = 𝑇𝐶(4) + 𝑀𝐶 = 40 + 8 = 48. Cost MC Now the ATC becomes 𝐴𝑇𝐶(5) = 𝑇𝐶(5)/5 = 48/5 = 9.6, which is lower than 𝐴𝑇𝐶(4) = 10. Therefore the prediction ATC MC(5)=47 made with the average-marginal rule in question a is correct. ATC(5)=36.5 §35. Suppose the total cost of a firm is 𝑇𝐶(𝑄) = 4.5𝑄2 + 2𝑄 + 60. Its marginal cost is 𝑀𝐶(𝑄) = 9𝑄 + 2. When Q=5, does ATC increase or decrease when the output increases little? Please use the average-marginal rule to answer this question (do not figure out the answer by calculating ATC(5) and ATC(6)). Remember to draw a Output graph to illustrate it. Here is a sample solution. 5 The MC at 𝑄 = 5 is 9 ∗ 5 + 2 = 47. The ATC at 𝑄 = 5 is 𝐴𝑇𝐶 = 𝑇𝐶 𝑄 = 4.5𝑄2 +2𝑄+60 𝑄 = 4.5∗52 +2∗5+60 5 = 36.5. Since MC>ATC, according to the average-marginal rule, ATC increases as Q increases by a little. The ATC curve is upward sloping at 𝑄 = 5. §36. Now we know that if MC<ATC, the ATC curve is downward sloping (producing another unit will decrease the ATC); if MC> ATC, the ATC curve is upward sloping (producing another unit will increase the ATC). The following graph illustrates these trends. At Q0, MC0<ATC0. At this point, the ATC curve is downward sloping. At output level 𝑄1 , 𝑀𝐶1 > 𝐴𝑇𝐶1 , and we see that the ATC curve at this point is upward sloping. From the above analysis, we can see that the lowest point on the ATC curve is where ATC=MC. §37. Suppose the total cost of a firm is 𝑇𝐶(𝑄) = 3.5𝑄2 + 4𝑄 + 63. Accordingly, its marginal cost is 𝑀𝐶(𝑄) = 7𝑄 + 4. We want to find the output level that gives the lowest ATC. The ATC of the firm is: 𝐴𝑇𝐶 = MC, so we have 3.5𝑄2 +4𝑄+63 𝑄 𝑇𝐶 𝑄 = 3.5𝑄2 +4𝑄+63 𝑄 MC Cost ATC Lowest point of ATC MC1 M ATC0 ATC1 MC0 Output Q0 Q1 . At the lowest point on the ATC curve, 𝐴𝑇𝐶 is equal to = 7𝑄 + 4. Solving the above equation (math help in the footnote1), we know that 𝑄 = √18 ≈ 4.24. So when the output level is 4.24, the ATC is minimized. 1 Multiply both sides by Q : (7𝑄 + 4) ∙ 𝑄 = 3.5𝑄2 +4𝑄+63 𝑄 ∙ 𝑄 ⇒ 7𝑄 2 + 4𝑄 = 3.5𝑄 2 + 4𝑄 + 63 ⇒ 7𝑄 2 = 3.5𝑄 2 + 63 ⇒ (7 − 3.5)𝑄 2 = 63 ⇒ 3.5𝑄 2 = 63 ⇒ 𝑄 2 = 18 => 𝑄 = √18 ≈ 4.24. 19 Question-30. (Mini-essay) A firm is currently producing 3 units of goods, and the average cost per unit (i.e., ATC) is $9. It would take another $10 to make the next unit of product. How would the ATC change if the firm decides to produce the next unit of product? Question-31. (Mini-essay) A firm’s current output level is 𝑄 = 9. Its ATC is $20/unit. It will take another 30 dollars to produce an additional unit of output. a. Use the average-marginal rule to predict how the ATC would change when another unit is produced on top of the current 9 units. b. Find ATC(10) and compare it with ATC(9). Does the ATC increase or decrease when another unit is produced? Is the result consistent with the prediction of the average marginal rule? • Refer to §34 for help. Question-32. (Mini-essay) A firm’s current output level is 𝑄 = 7. Its ATC is $20/unit. It will take another 10 dollars to produce an additional unit of output. a. Use the average-marginal rule to predict how the ATC would change when another unit is produced on top of the current 7 units. b. Find ATC(8) and compare it with ATC(7). Does the ATC increase or decrease when another unit is produced? Is the result consistent with the prediction of the average marginal rule? • Refer to §34 for help. Question-33. (Mini-essay) The total cost of a firm is 𝑇𝐶(𝑄) = 𝑄2 + 2𝑄 + 80. Its marginal cost is 𝑀𝐶(𝑄) = 2𝑄 + 2. When Q=4, does ATC increase or decrease when the output rises little? Please use the average-marginal rule to answer this question. • Refer to §35 for help. Question-34. (Mini-essay) The total cost of a firm is 𝑇𝐶(𝑄) = 3𝑄2 + 4𝑄 + 100. Its marginal cost is 𝑀𝐶(𝑄) = 6𝑄 + 4When Q=4, does ATC increase or decrease when the output increases by a little? Please use the averagemarginal rule to answer this question. • Refer to §35 for help. Question-35. (Mini-essay) The total cost of a firm is 𝑇𝐶(𝑄) = 4𝑄2 + 7𝑄 + 54. Its marginal cost is 𝑀𝐶(𝑄) = 8𝑄 + 7. Find the output level where the ATC reaches its minimum. • Refer to §37 for help. 20 3.6. Long-Run Cost Curves §38. So far, we have focused on the short-run costs. In the short run, part of the inputs is fixed, and the corresponding cost is the LRTC fixed cost. In the long run, however, there are no fixed inputs and Cost fixed costs. This creates some important differences when we are LRMC LRATC discussing the long-run cost curves: In the long run, the total cost equals the variable cost, so the variable cost curve coincides with the total cost curve. We will call the curve the long-run total cost curve and label it with LRTC. There are no fixed costs in the long run, so the LRTC starts from the origin (When Q=0, TC=0). Since there are no fixed costs in the long run, we do not have an AFC curve for the long run. In the long run, the AVC equals ATC, so we only have one average cost curve. We will label it with LRATC. We will still have a marginal cost curve for the long run, but it will be different from the one for the short Q run. We will label it with LMC. Long-run Cost Curves §39. We are most interested in the relation between short-run ATC curves and the long-run average cost curve (LRATC) because the relation best illustrates the difference between the short-run cost and the long-run cost. Consider a small plant that produces faucets. Suppose the faucets are produced with machine tools and labor. Machine tools are major investments for a plant, and it takes a long time to install them. Therefore, in the short run, they are fixed inputs. The three ATC curves in the following graph represent the ATC given different numbers of machine tools. Suppose the manager knows that the output levels are going to be 𝑄1 . Now she needs to determine how many machine tools to buy. Since the output level is fixed, the total cost of each plan is proportional to the ATC given that plan. Therefore, the manager will choose to buy one machine tool since its ATC is lower than that of buying two machine tools (15<20). If you insist on comparing the total cost of the two plans, you will find that the total cost of having one machine tool is 15𝑄1 and that of having two machine tools is 20𝑄1 . What if the firm plans to produce 𝑄2 units? You will see that having 3 machine tools will result in a lower ATC than having two machine tools, so the manager will buy 3 machine tools. Consequently, the ATC is given by point A on 𝐴𝑇𝐶3. The long-run ATC at each output level is the lowest of all possible ATC curves at that output level. For the firm in question, the LRATC is shown in the following graph. We say that it is the envelope of short-run ATC curves. Cost Cost 𝐴𝑇𝐶1 𝐴𝑇𝐶2 20 𝐴𝑇𝐶3 𝐿𝑅𝐴𝑇𝐶 Q Q 15 A 𝑄1 𝑄2 §40. Suppose there are many plant sizes that a firm can choose, then the LRATC of the firm looks like a smooth curve as follows. Note that the LRATC is not the collection of the minimum point of each short-run ATC. For example, in the following graph, the lowest point on 𝐴𝑇𝐶0, which is labeled with B, is not on LRATC. The downward-sloping region of the LRATC exhibits increasing returns to scale, and the upward-sloping region of it exhibits decreasing returns to scale. The technology shows constant returns to scale in a region if it is flat there. The minimum efficient scale is the lowest output level at which the average cost is minimized. 21 Cost 𝐴𝑇𝐶1 𝐴𝑇𝐶2 𝐴𝑇𝐶3 𝐴𝑇𝐶4 𝐴𝑇𝐶5 𝐴𝑇𝐶6 𝐿𝑅𝐴𝑇𝐶 B Minimum efficient scale Q Decreasing Increasing returns Constant returns to scale returns to scale to scale 22 Part 4: Market Structures 4.1. Introduction §41. So far, we have studied producers and consumers in isolation. From this chapter on, we will put them together and study their interactions. §42. When products from different suppliers have identical characteristics, we say that the products in the market are homogeneous. Finding a market with perfectly homogeneous products is difficult, but we can think of some close examples. Raw materials of industries are usually considered homogeneous. For instance, iron ores of the same grade produced by different mines can be regarded as homogeneous: they are essentially the same things to the buyers. Copper, steel, and gas may also be considered homogeneous. Agricultural products (sold to food processing companies) are also considered homogeneous: buyers do not see any difference between the corn produced by different farms if the corn is all of the same grade (quality). When products from different suppliers provide similar functions but have different styles and secondary characteristics, we say the products are differentiated or heterogeneous. Consider pens produced by different firms. They serve similar purposes, but they come in various styles, and people are aware of the difference between them. Therefore, pens are differentiated goods. Another example of heterogeneous goods is movies. They all serve the function of recreation, but very few people would think two movies are pretty much the same: different films have different plots, casts, music, etc. §43. If the products of an industry are perfectly homogeneous, then all that matters for consumers’ purchase decisions is the product's price. If the price of one firm is lower than other firms, then all consumers will buy from it. On the other hand, if its price is higher than other firms, then no consumers will buy from it. §44. The interactions between participants of a market (consumers, producers) depend on the characteristics of the market. We refer to these market characteristics as the market structure. The market structure consists of at least the following aspects: • The number of buyers in the market. • The number of sellers in the market. • Product homogeneity. • The information structure: who knows what. §45. There is a continuum of market structures, but most of the time we categorize them into five groups as shown in the following table. Like there is no clear criterion for “hot” and “cold” for temperatures, we do not have strict and clear-cut rules to decide to which category an industry in the real world belong. Monopsony Many suppliers What we see in the One buyer market One product Monopoly One supplier Many buyers One product Who can affect the market price The buyer decides the market price. The seller decides the market price. Do firms react to competitor’s decisions N/A N/A Where to look for examples Oligopoly A few suppliers Many buyers Homogeneous or differentiated goods Each supplier can greatly affect the market price. Monopolistic competition Many suppliers Many buyers Differentiated products Perfect competition Infinite suppliers Many buyers Homogeneous product Individual suppliers have little influence on the market price. No individual firms or consumers can affect the market price at all. Yes No No Industries that produces small consumption goods, which do not need the firms to be large Does not exist in the real world, but the financial market and the agricultural market are close examples Example: Industries that Industries that market for require large sum of require large sum of heavy weapons entry costs or entry costs or in each country regulated industries regulated industries 23 Question-36. Answer the following questions. a. Which good is more homogeneous for most people, A: copy paper or B: birthday cards? b. Which good is more homogeneous for most people, A: bottled water or B: soda? Question-37. Find an example of each of the following market structures, and provide related information. Market Structure Industry Name of one of the firms Monopoly Oligopoly Monopolistic competition 24 Location of the market Number of sellers (rough number) 4.2. Perfect Competition 4.2.1. Perfectly Competitive Markets §46. In economics, perfect competition means no individual participants have the market power to affect the market price. This is the nature of perfect competition. To have a perfectly competitive market, we need at least four conditions: • Homogeneous products: The products of different producers are highly similar. • Individual firms are small relative to the market: Sometimes, economists state this assumption by saying there are infinite firms in the market. • Free entry and exit: It is relatively easy to enter or exit the market. • Perfect information: Prices and quality of products are known to all consumers and producers. A perfectly competitive market is a conceptual tool that economists make up to help us understand economic activities. No truly perfectly competitive markets exist in the real world, though agricultural markets and financial markets may approximate the concept. §47. In a perfectly competitive market, all firms sell the same product by definition, so no consumers will purchase from a firm that charges a higher price. A firm in the real world wants to cut its price to attract more customers, but a firm in a perfectly competitive does not need to do so: by definition, it is infinitely small relative to the market, so it can always sell all it produces if it adopts the market price. Since a competitive firm has no incentive to charge a price greater or lower than the market price, it finds the market price the best price it should charge. If an agent finds it optimal to accept the market price, we say it is a price taker. P §48. In a perfectly competitive market, an individual firm is infinitely small relative to the market, and an increase in its sales will not affect the market price. Therefore, the demand curve of a competitive firm is a horizontal line. The industrial demand curve will still be downward sloping. Demand curve faced by an individual competitive firm 𝑑 $5 0 10 20 30 4.2.2. Short-Run Optimal Output Level: No shut-down §49. We have established that a competitive firm is a price taker, so it always charges the market price. A competitive firm chooses its output level in order to maximize its profit. As a firm sells an additional unit of output, its total revenue will most likely change. We refer to the change Δ𝑅𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑛𝑢𝑒 in the revenue as the marginal revenue. In symbols, it is 𝑀𝑅 = . A competitive firm always receives Δ𝑄 another $𝑃 if it sells another unit ($𝑃 is the market price), so 𝑀𝑅 = 𝑃 in a competitive market. Graphically, a competitive firm’s MR is a horizontal line. §50. Sometimes, firms may find that they had better stop producing and leave the industry. For competitive firms, this is because the market price is too low. In this section, we assume that the market price is sufficiently high, so the firm would like to produce a positive amount of output or that firms are not allowed to shut down. §51. In economics, we model a firm's decision-making as follows: The manager considers the additional cost that another unit of output will incur and the additional benefit (marginal revenue) that the unit of output will bring, then decides whether to produce that unit. For example, suppose a firm currently produces 4 boats a month. The manager is thinking about whether to build an additional boat each month. If the firm produces another boat each month, the monthly cost will increase by $30,000. Meanwhile, each boat sells for $25,000. Since the marginal cost is greater than the marginal benefit, the manager decides not to produce the 5 th boat. In this case, the marginal profit of producing the 5th boat is MR-MC= $25,000-$30,000=$-5000. In other words, the 5th boat causes the total profit to decrease by $5000 (or the 5th boat contributes $-5000 to the total profit). The process of deciding whether to take an action based on the comparison of the marginal cost and the marginal benefit of the activity is called marginal analysis. It means we first compare the marginal cost and the marginal benefit of an action and then decide whether to take that action. 25 Q Question-38. Use a few sentences to prove why a competitive firm finds it best to charge the market price. Hint: Prove that it is not desirable to charge a price greater than the market price, and it is not desirable to set a price below the market price. Question-39. Now let us consider how to find a competitive firm’s optimal output level. a. Use marginal analysis to determine the optimal output level of the following firm. Additional benefit brought Should the Additional cost by the unit (i.e., marginal Marginal firm produce Product incurred by the revenue, which equals Profit this unit? unit (i.e., MC) market price) Why? 1st unit $1 $8 nd $3 $8 rd 3 unit $5 $8 4th unit 2 unit $7 $8 th $9 $8 th $11 $8 5 unit 6 unit b. Draw a bar graph of the MC and then put the market price line on the graph. Can you tell from the graph which units the firm should produce? $ 10 c. From the above example, we can see that if the marginal cost is less than the marginal revenue (the market price), the firm ____________ (should/shouldn’t) produce that unit of output, and if the marginal cost is greater than the marginal revenue, then the firm _________ (should/shouldn’t) produce that unit.2 8 6 4 2 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 Output 2 For expositional purposes, let us assume that if MC=MR for a unit of output, the firm always produces that unit of output. 26 §52. The following graph shows some curves concerning a competitive firm. a. Suppose the current output level is 4. Would the firm like to increase or decrease its output level? At 𝑄 = 4, the MR is 9 (MR=P for competitive $ firms). According to the MC curve, MC ≈ 4.9 when Q=4. Since MR>MC the firm would like to produce MC more. b. Suppose the current output level is 10. Would the MR firm like to increase or decrease its output level? At 𝑄 = 10, the MR is 9 (MR=P for competitive firms). According to the MC curve, MC ≈ 10.3 when MC=10.3 MR=9 Q=10. Since MR<MC, the firm would like to MR=9 produce less. c. According to the graph, what is the optimal output MC=4.9 level of the firm? (It doesn’t have to be a whole number.) Why is it the optimal output level? Q The optimal output level is 8.5. For each unit up to Q*=8.5 𝑄 = 8.5, 𝑀𝐶 < 𝑀𝑅, so the firm finds it profitable to produce all these units. For any unit after 𝑄 = 8.5, 𝑀𝐶 > 𝑀𝑅, so the firm finds it unprofitable to produce any of those units. d. At the optimal output level, the marginal profit is ______. At the optimal output level, MR=9, and MC=9, so the marginal profit is MR-MC=0. (Note: If MC and MR change continuously, the marginal profit should always be zero at the optimal output level.) §53. Now we can make an important conclusion: a firm’s optimal output level is where 𝑴𝑹 = 𝑴𝑪 if it finds it optimal to stay in business. This is true for all firms in all market structures, given our assumptions in this chapter. For a competitive firm, its MR is simply equal to the market price 𝑃, so the condition simplifies to 𝑃 = 𝑀𝐶. The practice of charging a price equal to the marginal cost is called marginal cost pricing. §54. The following graph shows the MC curve of a competitive MC firm. Suppose the market prices are sufficiently high so the firm $ would like to keep operating. Let us find the optimal output levels of the firm when the prices are 4, 6, 8, and 10, respectively. 10 To find the optimal output level at a given price, we just need to find the intersection of that price and the MC curve. The graph 8 shows that the optimal output levels are 3.9, 7.8, 10.1, and 12 at 6 the above prices. §55. A competitive firm’s fixed cost is 150. When it is producing 4 and selling 𝑄 units, its variable cost is 𝑄2 + 10𝑄 and its marginal cost is 𝑀𝐶(𝑄) = 2𝑄 + 10, which means that its MC is 2𝑄 + 10 2 when its output is Q. Suppose the current market price is 𝑃 = 30. Note: When we say a firm is a competitive firm, we imply that 0 3.9 7.8 10.1 12 Q the market is a perfectly competitive market. a. You are told that the firm will find it optimal to keep running. Please find the optimal output of the firm. For a competitive firm, 𝑀𝑅 = 𝑃, so 𝑀𝑅 = 30 in this case. At the optimal output level (the output that maximizes the profit or minimizes the loss), we have 2𝑄 + 10 = 30. Solving this equation, we know the optimal output is Q= 10. b. Use marginal analysis to explain why the above quantity is optimal. For each unit up to 𝑄 = 10, 𝑀𝐶 < 𝑀𝑅, so the firm finds it profitable to produce all these units. For any unit after 𝑄 = 10, 𝑀𝐶 > 𝑀𝑅, so the firm finds it unprofitable to produce any of those units. c. Find the firm’s profit when it chooses the optimal output level. At 𝑄 = 10, the revenue is 𝑅 = 𝑃𝑄 = 30 ∗ 10 = 300, and the total cost is 𝑇𝐶(10) = 𝑉𝐶 + 𝐹𝐶 = (𝑄2 + 10𝑄) + 150 = 102 + 10 ∗ 10 + 150 = 350. The firm’s profit is 𝜋(10) = 𝑅𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑛𝑢𝑒 − 𝐶𝑜𝑠𝑡 = 𝑅 − 𝑇𝐶 = 300 − 350 = −50. 27 Question-40. (Mini-essay) The following graph shows a firm's MR and MC curves in a perfectly competitive market. a. Suppose the current output level is 3. Would the firm like to increase or decrease its output level? Please illustrate your answers on the figure (i.e., show MR and MC like in §52). b. Suppose the current output level is 8. Would the firm like to increase or decrease its output level? Please illustrate your answers on the figure (i.e., show MR and MC like in §52). c. Find the optimal output level of the firm. Why is it the optimal output level? d. Find the marginal profit at the optimal output level. • Refer to §52 for help. MC $ MR Output Question-41. Refer to §54. It seems that the MC curve can help us find the output level of a competitive firm. Then can we say that the MC curve is the supply curve? Why or why now? Question-42. (Mini-essay) A competitive firm’s fixed cost is 50. When it is when producing 𝑄 unit, its variable cost is 5𝑄2 and its marginal cost is 10𝑄, meaning its MC is 10𝑄 when its output is Q. Suppose the current market price is 𝑃 = 40. a. Find the optimal output of the firm. You are told that the firm will find it optimal to keep running. b. Use the marginal analysis to explain why the above quantity is optimal. c. Find the firm’s profit when it chooses the optimal output level. • Refer to §55 for help. 28 4.2.3. Three Stages of Decisions of All Firms §56. The figure on the right shows the three decisions that firms need to make during different stages: • • Entry decision: Enter the industry or not. In this stage, decision-makers only have a rough idea about the cost structure and the demand conditions. The calculations are based on expected numbers (e.g., “This is a busy boulevard. The demand for food should be high.”) Based on the expected numbers, if R>TC, then enter. R>TC means P*Q>ATC*Q, so the entry decision boils down to whether 𝑃 > 𝐴𝑇𝐶. Note that the potential entrant is making long-run decisions. The ATC here is the long-run ATC. • Enter the industry? At this point, investors only have some vague ideas about how the demand and its own productivity. If P >ATC, then profit= R-TC=P*Q-ATC*Q>0 Yes. Enter. If P <ATC, then profit= R-TC=P*Q-ATC*Q<0 No. Do not enter. Invest on other projects • • Enter and pay fixed costs Fixed cost is sunk in the short run. Cost and demand are revealed. The firm observes P and AVC Shutdown decision: Shut down or not after starting operating. There are two typical scenarios in which a firm has to consider shutting down in the short turn. The first scenario is that the market is cyclical, roughly meaning that the Decision: Shut down? profitability fluctuates substantially over time. A restaurant • FC is sunk. Only need to compare R and VC nearby a college campus may decide to shut down during the summer, for example. A second scenario is that a firm finds the cost is too high and the demand is too low after they enter If P<AVC, then R-VC If P>AVC, then R-VC the industry. Remember that the entry decision is based on = P*Q-P*AVC<0 = P*Q-P*AVC>0 expected numbers. The firm will find out the actual cost structure and the demand condition only when it starts Shut down Operate operating (e.g., “This is a busy boulevard. The demand for food is high. But the customers don’t like the food of my restaurant.”). Choose optimal output level In the short run, the fixed cost is sunk. For example, a • It is where MR=MC. business usually must sign a lease for multiple years. Suppose it is challenging to sublease, then the rent is sunk. In making shut-down decisions, we can forget the fixed cost. If the firm keeps operating, the future benefit is the revenue, and the future cost is the variable cost. The firm should keep operating as long as 𝑅 > 𝑉𝐶, which means 𝑃 ∗ 𝑄 > 𝐴𝑉𝐶 ∗ 𝑄. Therefore, the shutdown condition boils down to whether 𝑃 > 𝐴𝑉𝐶. • Output decision: If it keeps operating, decide the optimal output level. The optimal output is where MR=MC. §57. The three decisions are straightforward by themselves. The questions can be complicated when they are placed in the context of cost curves. Here are two conclusions with which you should get familiar. a. If a competitive firm is operating on the upward-sloping part of its ATC curve (read “P=MC>ATC”), it is making money; otherwise, it is taking a loss. b. If a competitive firm is operating on the upward-sloping part of its AVC curve (read “P=MC>AVC”), it should not shut down; otherwise, it should. 29 $ MC ATC P AVC 𝐴𝑇𝐶 𝐴𝑉𝐶 𝑄 Output Question-43. Now we will use short-run cost curves to analyze a competitive firm’s shut-down decision. In the following graph, the market price is P, which is represented by the thick dashed horizontal line. $ a. Illustrate how to find the optimal output level with marginal cost pricing. Explain how you find it. MC ATC The optimal output 𝑄 ∗ is where the price line crosses the MC curve (remember to draw a vertical line that passes the intersection of MC and P). AVC B C b. Show the total cost of the firm on the graph and explain why it Loss P=MR is equal to TC. A D ∗ ∗ We know that 𝑇𝐶 = 𝐴𝑇𝐶 × 𝑄 . In this question, at 𝑄 , the ATC is the height of 𝐵𝑄 ∗ , and the length of OQ represents the output F E level Q*. Therefore, 𝑇𝐶 = 𝐵𝑄 ∗ × 𝑂𝑄 ∗ = 𝐴𝑟𝑒𝑎 𝑜𝑓 𝑂𝑄 ∗ 𝐵𝐶. Output 𝑄∗ O Show the revenue of the firm on the graph and explain why it equals the revenue. We know that 𝑅 = 𝑃 × 𝑄 ∗ . In this question, at 𝑄 ∗ , the price is the height of 𝐴𝑄 ∗ . Therefore, 𝑅 = 𝐴𝑄∗ × 𝑂𝑄 ∗ = 𝐴𝑟𝑒𝑎 𝑜𝑓 𝑂𝑄 ∗ 𝐴𝐷. c. d. Show the profit of the firm on the graph and explain why it equals the profit. We know that 𝜋 = 𝑅 − 𝑇𝐶 = 𝐴𝑟𝑒𝑎 𝑜𝑓 𝑂𝑄∗ 𝐴𝐷 − 𝐴𝑟𝑒𝑎 𝑜𝑓 𝑂𝑄 ∗ 𝐵𝐶. We can see that the firm is losing money, so the loss is 𝐴𝑟𝑒𝑎 𝑜𝑓 𝐴𝐵𝐶𝐷 e. Should the firm be shut down? Answer it in three different ways. i. Please answer this question by comparing revenue and variable cost. The variable cost of the firm is 𝑉𝐶 = 𝐴𝑉𝐶 × 𝑄 ∗ = 𝐸𝑄 ∗ × 𝑂𝑄 ∗ = 𝐴𝑟𝑒𝑎 𝑜𝑓 𝑂𝑄 ∗ 𝐸𝐹. Since 𝑉𝐶 = 𝐴𝑟𝑒𝑎 𝑜𝑓 𝑂𝑄 ∗ 𝐸𝐹 < 𝑅 = 𝐴𝑟𝑒𝑎 𝑜𝑓 𝑂𝑄 ∗ 𝐴𝐷, the firm should not shut down (the firm is making money if we forget the fixed cost). ii. Now answer this question by comparing the loss of keeping operating with the fixed cost (FC would be the total loss if the firm decides to shut down in the short run). The fixed cost of the firm is 𝐹𝐶 = 𝐴𝐹𝐶 ∗ 𝑄 ∗ = (𝐴𝑇𝐶 − 𝐴𝑉𝐶) ∗ 𝑄 ∗ = 𝐵𝐸 × 𝑄∗ = 𝑎𝑟𝑒𝑎 𝑜𝑓 𝐹𝐸𝐵𝐶. If the firm shuts down, its loss equals FC. If it keeps running, its loss is ABCD. We can see that the loss is smaller if the firm keeps running. iii. Now answer this question by comparing AVC and P. Since 𝑃 < 𝐴𝑉𝐶, the firm is earning profit from each unit of output. Since there is nothing the firm can do about the fixed cost, it might as keep the firm running. 30 4.2.4. Short-Run Supply Curve §58. Section 4.2.2 shows that a competitive firm’s optimal output level is where P equals MC if the price is high enough. In other words, when the market price is sufficiently high, the supply curve of the firm and its marginal cost curve coincide. Section 4.2.3 shows that a competitive firm would shut down when the market price is below the AVC. Therefore, a competitive firm’s short-run supply curve is the portion of its MC curve above the AVC curve. $ MC ATC AVC Q 4.2.5. Long-Run Competitive Equilibrium §59. When a firm operates in the long run, its optimal output level is where the market price equals its longrun marginal cost. In the following exhibit, the market price is at point D. It crosses the firm’s long-run marginal cost curve at C. The firm’s long-run optimal ∗ output level is 𝑄𝐿𝑅 . The firm’s long-run profit is the area of the rectangle ABCD. Had the firm been operating in the short-run, its fixed inputs may not be at the long-run level. As a result, its short-run marginal cost curve may be MC, and its average cost curve may be ATC. Its short-run ∗ output level will be 𝑄𝑆𝑅 . Its short-run profit will be EFGD, which is smaller than its long-run profit. Cost MC ATC LMC LATC D E A G F Long run market price C B 𝑄∗𝑆𝑅 𝑄∗𝐿𝑅 Output §60. In the long-run equilibrium of a competitive industry, the expected profit of a firm is zero. Suppose firms in the industry are making a profit. More firms will enter the industry driven by the expectation of positive profit. As new firms enter the industry, the market supply curve of the industry shifts right. Consequently, the market price in the industry will decrease. As a result, the profit of individual firms will fall. The entry of new firms will continue until firms make zero economic profit in the industry. 4.3. Monopoly §61. In the previous chapter, we studied the perfectly competitive market, where there are numerous small companies and consumers, none of which can affect the market price. In this chapter, we will study the antithesis of perfect competition — monopoly, which refers to a market structure with only one seller without close substitutes to the firm’s product. §62. The main reason for the existence of the monopoly is barriers to entry, which make it illegal or unprofitable to enter the market. There are two primary types of entry barriers: • Legal barriers: Sometimes, only one firm has the legal right to supply the goods or services. For example, the U.S. Postal Service is the only legal supplier for first-class mail service. A firm designated by the government as the only legal provider of a good or service is a public franchise. Another example of legal barriers is patents. If a firm has a patent on a product, then it is illegal for any other firm to produce the product without permission (the term of the patent is 20 years in the U.S.). • Economic barriers: Economic barriers are factors that make it difficult for an entrant to make a profit. For example, if a small market can only sustain one firm, then the small market size is an economic barrier to the second entrant. A monopoly due to a small market size (relative to the fixed cost) is called a natural monopoly. Let us consider another example. Suppose a firm’s technology is much superior to others, then the firm may charge a price that is so low that no potential entrants can make a profit given that price. Other entry barriers that may result in monopoly include ownership of a necessary resource, such as a metal company that owns all the mines needed for producing the metal. 31 Question-44. (Mini-essay) The graph on the right shows the short-run cost curves of a competitive firm and the market price. Please make sure you do not make mistakes when copying the graph. Please label each point with the same letter used in the example so that it would be easier for members of a group to discuss. a. Illustrate how to find the optimal output level with marginal cost pricing. Explain how you find it. $ MC b. ATC Show the firm's total cost on the graph and explain why it is equal to TC. AVC c. Show the firm's revenue on the graph and explain why it equals the revenue. A Price MR=P Output O d. Show the firm's profit on the graph and explain why it equals the profit. e. Should the firm be shut down? Answer it in 3 ways. 1. Please answer this question by comparing revenue and variable cost. 2. Now answer this question by comparing the loss of keeping operating with the fixed cost. 3. Now answer this question by comparing AVC and P. Refer to Question-43 for help. • Question-45. The following graph shows the MC curve of a competitive firm. Use it to find the optimal output level for each price level. Suppose the following prices are all above the AVC at the corresponding output level. • 𝑃=3, 𝑄 ∗ =_____ • 𝑃=4, 𝑄 ∗ =_____ • ∗ 𝑃=5, 𝑄 =_____ • 𝑃=6, 𝑄 ∗ =_____ $ MC 10 8 6 4 2 0 32 2 4 6 8 10 12 Q 4.3.1. Marginal Revenue of a Monopolist §63. In a perfectly competitive market, the market price 𝑃 is given. A firm receives another 𝑃 dollars of revenue when it sells an additional unit of its good. We say that the marginal revenue of a competitive firm equals the market price, which is constant: 𝑀𝑅𝑐𝑜𝑚𝑝𝑒𝑡𝑖𝑡𝑖𝑣𝑒 = Δ𝑅/Δ𝑄 = 𝑃. A competitive firm does not need to lower its price to sell another unit, which is the key to the result that its marginal revenue is constant. For a monopolist, however, things are a little different: she must lower their price to sell another unit. Therefore, a monopolist’s marginal revenue differs from a competitive firm's. §64. Now let us consider a monopolist in a market. Suppose if she wants to sell 20 units of products, she will need to charge a price of $30/unit. If she wants to sell another unit of product, she will need to decrease the price by $0.5/unit. Note that the monopolist needs Price to charge all the 21 units at a price of $29.5/unit if she decides to lower the Demand price. curve P=30 a. Let us call the additional unit the marginal unit. How much revenue --------------0.5 -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -does the firm receive for the marginal unit? - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - +++ The new price is $30/unit-$0.5/unit=$29.5/unit, so the monopolist P'=29.5 --------------receives another $29.5 for the marginal unit. +++ b. c. d. Let us call the first 20 units the infra-marginal units. When the monopolist sells the additional unit, she receives $0.5 less for each infra-marginal unit. In total, the revenue for the infra-marginal units decreases by how much? The monopolist receives $0.5 less for each of the 20 infra-marginal units, so she loses 20*0.5=$10 in total for these units. O +++ +++ +++ +++ Q'=21 Q=20 1 How much is the net change in revenue due to the selling of the marginal unit (i.e., the MR)? The marginal revenue is $29.5-$10=$19.5. The answer means that at the current output level, when an additional unit is sold, the revenue increases by $19.5. Compare the MR with the new price. Why is it less than the new price? When the monopolist sells the marginal unit, she receives an additional amount of revenue equal to the new price. However, she also loses some revenue on the infra-marginal units. Consequently, the marginal revenue (the net change in revenue) is less than the new price. §65. When the monopolist sells the marginal unit, she receives an additional amount of revenue equal to the new price. However, she also loses some revenue on the infra-marginal units. Consequently, the marginal revenue (the net change in revenue) is less than the new price. Under some circumstances, the marginal revenue could even be negative. P D P1 Decrease in the revenue for inframarginal units. P1 (Money received for the marginal unit) MR (Net change in the revenue). 𝑄1 33 MR 𝑄 Question-46. (Mini-essay) A monopolist’s current output is 100, and the price is $10/unit. To sell another unit of her product, the monopolist needs to decrease the price by $0.2. a. Find the revenue that the firm receives for the marginal unit. b. Find the decrease in the revenue of the inframarginal units if the firm decides to sell the marginal unit. Price c. Find the net change in the revenue caused by the marginal unit (i.e., the MR). Please explain what the answer means. d. Explain why the MR is less than the new price. • Refer to 4.3.1 for help. O Demand curve 𝑃 --------------------------------------------------------------------𝑃′ - - - - - - - - - - - - - -𝑀 +++ +++ +++ +++ +++ 𝑄 +++ 𝑄′ Quantity 1 Question-47. (Mini-essay) A monopolist’s current output is 150, and the price is $20/unit. To sell another unit of output, the monopolist needs to decrease the price by $0.3. Find the marginal revenue at the current output level and explain why it is less than the new price. • Refer to 4.3.1 for help. Question-48. Refer to §65. Use the lengths of line segments to represent the following variables at 𝑄1 on the figure • Money received for the marginal unit • Decrease in the revenue for infra-marginal units. • Marginal revenue P D P1 𝑄1 MR 34 𝑄 4.3.2. The Monopolist’s Output Decision P §66. The following graph shows the MR and the MC of a monopolist. We want to find the output level that maximizes the profit, i.e., the optimal quantity located. Suppose the current output level is 𝑄1 . How would the monopolist change her output level? At this output level, the additional cost of producing another MC unit is 𝑀𝐶1 and the additional revenue of doing so is 𝑀𝑅1 . Since 𝑀𝑅1 > 𝑀𝐶1 , the monopolist would like to produce more (as long as MR>MC). Suppose the current output level is 𝑄2 . At this output level, the additional D cost of producing another unit is 𝑀𝐶2 and the additional revenue of doing so is 𝑀𝑅2 . Since 𝑀𝑅2 < 𝑀𝐶2 , the monopolist would like to cut back her output level 𝑀𝑅1 (as long as MR<MC). 𝑀𝐶2 Therefore, the optimal output level of a monopolist is where MR=MC. 𝑀𝐶1 §67. Suppose the inverse demand of a monopolist is 𝑃 = 40 − 2.5𝑄. An inverse MR 𝑀𝑅2 demand function tells us the price that a firm should adopt, given the quantity 𝑄 𝑄1 𝑄∗ 𝑄2 it wants to sell. For example, suppose the inverse demand function of a monopolist is 𝑃 = 40 − 2.5𝑄, then if the firm wants to sell 𝑄 units, it needs to set its price to 40 − 2.5𝑄. Given her inverse demand function, her marginal revenue would be 40 − 5𝑄 when her output level is Q.3 Her total cost is 𝑇𝐶(𝑄) = 0.5𝑄2 + 10𝑄 + 5. You are told that the marginal revenue is 40 − 5𝑄, and its MC is 𝑄 + 10 when the output level is 𝑄. Find the profit of the monopolist. The optimal output level is where 𝑀𝑅 = 𝑀𝐶, so we have 40 − 5𝑄 = 𝑄 + 10. Solving the above question, we know that the optimal output level is 5. The price of the firm is 𝑃 = 40 − 2.5𝑄 = 40 − 2.5 × 5 = 27.5. Its revenue is 𝑅 = 𝑃 × 𝑄 = 27.5 × 5 = $137.5. The total cost of the firm is 𝑇𝐶 = 0.5𝑄2 + 10𝑄 + 5 = 0.5 × 52 + 10 × 5 + 5 = $67.5. The firm’s profit is 𝑅 − 𝑇𝐶 = $137.5 − $67.5 = $70. 4.3.3. Social Costs of Monopoly Power §68. Monopoly power will cause at least two social costs: exacerbate income inequality and decrease the total social welfare. Let us examine how monopoly power exacerbates income inequality. In the graph on the right, the monopolistic price will be B. Had the monopolist practiced marginalcost pricing, the price level would be C. Consider the consumers who A buy the units 𝑂𝑄𝑀 . With marginal-cost pricing, their consumer P Deadweight surplus would be CDFA. Under monopolistic pricing, their consumer MC loss F surplus decreases to BFA. The surplus represented by area CDFB is B transferred to the monopolist as part of their profit when we move D from marginal-cost pricing to monopolistic pricing. C E Demand §69. The second social cost of monopoly power is deadweight loss. G Deadweight loss is a potential benefit that no one in the economy MR receives. For each unit between 𝑄𝑀 and 𝑄𝐶 , consumer’s reservation value is greater than the marginal cost. In other words, its marginal social benefit is greater than its marginal social cost, so it should be O 𝑄𝑀 𝑄𝐶 Q produced. The total social surplus of making these units is the area GEF. Unfortunately, these units will not be produced. Hence, no one in the economy will receive the social surplus GEF. The unrealized social surplus GEF is the deadweight loss caused by monopoly power. Since P = 40 − 2.5Q, we have R = P × Q = (40 − 2.5Q) × Q = 40Q − 2.5Q2 . MR = ΔR/ΔQ, so MR = Δ(40Q − 2.5Q2 )/ΔQ = 40 − 5Q. The last step is an application of a calculas formula. 3 35 Question-49. (Mini-essay) The total cost of a firm is 𝑇𝐶(𝑄) = 4𝑄2 + 5𝑄 + 50. The (inverse) demand for a monopolist is 𝑃 = 80 − 𝑄. You are told that the marginal revenue is 80 − 2𝑄, and its MC is 8𝑄 + 5 when the output level is 𝑄. You are told that the firm will not shut down. Please find the profit of the monopolist. • See §67 for help. Question-50. Do you notice any monopoly in our economic life that needs to be better managed to enhance social welfare? Question-51. Draw a graph and use it to (1) explain why a monopoly causes welfare loss to the economy, (2) illustrate the total deadweight loss on the graph. 36 4.3.4. Limiting Market Power §70. We can see that monopoly leads to higher prices and lower output, which causes deadweight loss. It can also exacerbate the problem of income equality: the owners of the monopoly firm may become richer at the expense of consumers. Therefore, economists and policymakers have been thinking of ways to limit the downside of monopoly. Trivia: In the U.S., the antitrust law is the Sherman Antitrust Act • First, the government can try to lower the entry barriers so that (1890). The act “prohibits 4 more firms can enter a market if that is economical . contracts, combinations, or • The government can regulate a monopoly if the competition conspiracies in restraint of cannot break it. For example, in Pennsylvania, FirstEnergy is the trade.” (Pyndick and Rubinfel, company that supplies the electricity. However, its prices are 2009) It was the first US Federal subject to heavy regulations by the government. statute to contain cartels and • The government can also directly run a monopoly if regulation is monopolies. not the best solution. For example, the USPS is the only firm that • • provides first-class mail service. Altoona Water Authority is the John Sherman, the principal only producer of water in Altoona. author of the Sherman Antitrust The government can fragment a big monopoly into smaller firms Act was the republican senator if appropriate. AT&T was viewed as a monopolist in the of Ohio. telephone service industry. On January 1, 1984, AT&T's local operations were split into seven independent Regional Holding Companies. Finally, there are anti-trust laws that prevent firms from acting as a monopolist collusively. 4.4. Monopolistic Competition §71. A market characterized by monopolistic competition is a market in which firms can enter freely, each producing its own version of a differentiated product. Markets of most of the consumption goods feature monopolistic competition. §72. Consider a firm in a monopolistic competitive market. The figure on the right shows the firm's profile in the short run. P MC The firm’s short-run demand, 𝐷𝑆𝑅 , is determined by the market demand and the number of competitors. When there 𝐴𝑇𝐶 are more firms in the market, the demand for the firm’s 𝑃𝑆𝑅 product decreases, and curve 𝐷𝑆𝑅 shifts leftward. 𝐴𝑇𝐶0 The optimal output of the first is where the MC curve 𝐷𝑆𝑅 and the short-run marginal revenue curve, 𝑀𝑅𝑆𝑅 , intersects. The optimal output is labeled as 𝑄𝑆𝑅 . 𝑀𝑅𝑆𝑅 Suppose the average cost is 𝐴𝑇𝐶0 when the output level is 𝑄𝑆𝑅 . The short-run profit of the firm is 𝜋𝑆𝑅 = (𝑃𝑆𝑅 − 𝐴𝑇𝐶0 ) × 𝑄𝑆𝑅 . The firm's short-run profit equals the area of the shaded rectangle in the figure. 𝑄𝑆𝑅 𝑄 Note that a firm in a monopolistic competitive market could be making a loss in the short turn. Suppose the ATC curve is above its current position in the figure and the ATC is greater than 𝑃𝑆𝑅 . Then the profit of the firm would be negative. §73. If a representative firm in a monopolistic competitive market is making a profit, the industry will attract more firms to enter. As new firms enter the market, the individual demand of each firm will decrease. As a result, the profit of each firm decreases. The adjustment will continue until each firm earns zero economic profit. When no more firms enter or exit the industry, the market is in long-run equality. The following figure shows the longrun profile of the firm. 4 For example, the government can prevent some firms from controlling all the resources needed in the industry. 37 P MC 𝐴𝑇𝐶 𝑃𝐿𝑅 𝐷𝐿𝑅 𝑀𝑅𝐿𝑅 𝑄𝐿𝑅 𝑄 If a representative firm loses money, some firms will exit the industry. The demand for individual firms will increase. Eventually, firms make zero economic profit, and the industry reaches long-run equilibrium. §74. Had a monopolistic competitive firm behaved as a competitive firm, it would produce until its marginal cost equal the price. In the following figure, its competitive output would be 𝑄𝐶 . However, the firm will only produce 𝑄𝐿𝑅 . This will lead to a deadweight loss, represented by the shaded triangle in the figure. In a monopolistic competitive market, consumers will benefit from the diversity of products produced by different firms. The gains of product diversity balance the deadweight loss. P MC 𝐴𝑇𝐶 𝑃𝐿𝑅 𝐷𝐿𝑅 𝑀𝑅𝐿𝑅 Deadweight loss 𝑄𝐿𝑅 𝑄𝐶 𝑄 4.5. Oligopoly §75. An oligopoly is a market with only a few firms, where entry by new firms is difficult. In an oligopoly, the products sold by different firms may be homogeneous or differentiated. An oligopoly with two firms is called a duopoly. Examples of oligopolistic industries include automobiles, steel, aluminum, petrochemicals, electrical equipment, and computers. §76. In an oligopoly, firms react to their rivals’ actions. The strategic interactions between firms are the unique feature of the oligopoly. It also makes it challenging to analyze the market structure. To study an oligopoly, we need to turn to game theory. Game theory is a subject that studies the outcome when multiple agents are maximizing their own outcome, while each agent’s outcome depends on the actions of others. 38 §77. When each agent selects their best action based on the actions of other agents, we say the game is in Nash equilibrium. It is named after mathematician John Nash, who pioneered the study of game theory. The prisoners’ dilemma is a classic example to demonstrate Nash equilibrium. Suppose two prisoners must decide separately whether to confess to a crime. The DA would like both prisoners to confess and receive a fair sentence. He sets up the plead deal as follows. If a prisoner confesses, he will receive a lighter sentence, and his accomplice will receive a heavier one. But if neither confesses, sentences will be lighter than if both confess. The following table shows the detailed payoffs of each prisoner in different situations. The first number is the sentence of Prisoner A, the second Prisoner B. If both prisoners choose to confess, they both receive five years. If Prisoner A confesses and Prisoner B does not, then Prisoner A receives one year, and Prisoner B receives 10 years. Prisoner B Confess Don’t confess Confess -5, -5 -1, -10 Prisoner A Don’t confess -10,-1 -2, -2 Given the setup, a prisoner’s best reaction is always to confess no matter what the other prisoner decides to do. Therefore, the combination (Confess, Confess) is the Nash equilibrium of this game. §78. There are three well-known models of oligopoly. They explain why we see the oligopoly equilibria that exist in the world. The three models are the Cournot model, the Stackelberg model, and the Bertrand model. §79. The Cournot model assumes that firms in an oligopoly produce a homogeneous good. Each firm treats the output of its competitors as fixed, and all firms decide simultaneously how much to produce. In this model, when other firms produce more, the best reaction of a firm is to produce less. The equilibrium is where no firms want to change their output. 𝑄1 Firm 2’s reaction curve given 𝑄1 Cournot equilibrium 𝑄1∗ Firm 1’s reaction curve given 𝑄2 𝑄2∗ 𝑄2 §80. The Stackelberg model is similar to the Cournot model. In the Stackelberg model, however, one firm sets its output before other firms do. The firm that sets its output first is called the first mover. The first mover can anticipate how its competitors will react to its action and choose the most advantageous output level. Therefore, it has the first-mover advantage. §81. Bertrand model is an oligopoly model in which firms produce a homogeneous good, each firm treats the price of its competitors as fixed, and all firms decide simultaneously what price to charge. This model predicts that the market price equals the second-lowest marginal cost of all firms in equilibrium. §82. A cartel is a market in which some or all firms explicitly collude, coordinating prices and output levels to maximize joint profits. Examples of cartels include the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) oil cartel and the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) for intercollegiate athletics. 39 Part 5: Special Topics 5. International Trade 5.1. International Trade Theory §83. Trade is ubiquitous in our lives. Every day, we consume all kinds of goods and services. Most of us, however, do not produce the goods and services we consume if we are producing anything. For example, few of us grow wheat and bake bread ourselves; almost none of us grow cotton and use it to make our clothes by ourselves. Often, we specialize in a very narrow range of production activities and use our output to trade for the goods and services we want. For example, person A may be specialized in making coffee; person B may focus on plumbing work; person C may be an engineer who designs new computer chips. Each of them trades what they produce for what they consume. Trade is essential to the high living standards of the modern world. If we must produce everything by ourselves, it is hard to imagine how we will be able to have all the goods and services that we enjoy every day. In the hypothetical world, our lives will not differ from those of our ancestors' thousands of years ago. §84. Trade is an integral part of our economy because it can significantly increase the amount and the variety of goods and services available to us. It does so by allocating resources to suitable production activities, stimulating competition and improving efficiency, and providing larger markets for producers to exploit economies of scale. §85. International trade is trade between different economies. It is the exchange of goods and services across international borders or territories. The traded goods and services may be used for production or consumption. International trade takes place for the same reason intra-national trade exists, but it has two distinct characteristics. First, different countries may be good at producing very different products and services. For example, many Mideast countries can produce large quantities of petroleum at low costs; Brazil has the suitable climate and farmland to produce soybeans; Honduras is where bananas flourish; the US excels in financial services due to the legal environment and other factors. Second, international trade is usually subject to more restrictive trade barriers. Trade barriers are factors that make trade costly or even impossible to happen. The most significant trade barriers are geography (e.g., distance), restrictive trade policies (e.g., tariffs), and differences in language, culture, and laws. §86. The most well-known explanation for the benefits of international trade is comparative advantage. The comparative advantage in producing a good is that a country has a lower opportunity cost for the good than another country. Comparative advantage may arise from differences in labor productivity, a relative abundance of resources, and differences in policies. Economist David Ricardo first developed the theory of comparative advantage. Ricardo assumed that the international differences in labor productivity are the sole source of comparative advantage. This approach is modeling international trade is called the Ricardian model. §87. Let us use an imaginary economy to illustrate the workings of the Ricardian model. Suppose there are only two countries in the world, the Home country (H) and the Foreign country (F). People in both countries produce and consume food and clothing. The following table shows each country's labor endowments and the amount of labor it takes to produce a unit of good in each country. Labor Unit Labor Requirement Unit Labor Requirement for Endowment for Food Clothing Home 1200 3 labor → 1 unit of food 4 labor → 1 unit of clothing Foreign 600 5 labor → 1 unit of food 8 labor → 1 unit of clothing According to the data in the table, it takes less labor for the Home country to produce a unit of either of the two goods. In other words, the Home country is more efficient in producing both goods. You can also say the Home country has an absolute advantage in both goods. 40 Here comes the very important question: does the Home country want to try with a country that is less efficient in both industries? To answer the question, we need to check the opportunity costs of goods in two countries. Let us consider the opportunity cost of food. To produce another unit of food in the Home country, it takes 3 units of labor. The Home country will have to give up 3/4= 0.75 units of clothing to have the additional unit of food. Therefore, the opportunity cost of a unit of food is 0.75 units of clothing. Likewise, we can find that the opportunity cost of a unit of food in the Foreign country is 5/8=0.625 units of clothing. We say the foreign country has a comparative advantage in food production because it has a lower opportunity cost for clothing. We can also show that the home country has a comparative advantage in food production. A country cannot have a comparative advantage in both goods. The comparative advantage of the two countries is the opposite. Now we can show that there is an opportunity for both countries to benefit from the differences in the opportunity costs. In terms of clothing, it is relatively more costly for the Home country to produce a unit of food because it has to give up 0.75 units of clothing, vis-à-vis 0.625 units of clothing given up by the foreign country. The Home country can cut a deal with the Foreign country: it gives the Foreign country 0.7 units of clothing and gets a unit of food in return. You will find that both countries will be happy with the deal: the Home country no longer needs to give up 0.75 units of clothing for a unit of food; the Foreign country gets more clothing than what it could produce with the 5 units of labor, which is the resource it uses to produce the unit of food it exports to the Home country. The above example shows that if each country exports the good in which it has a comparative advantage, both countries can benefit from trade. The conclusion holds when one country is more efficient in the production of both goods. §88. In the above example, we assume two countries adopt the relative price “0.7 units of clothing for 1 unit of food” for their trade. The relative price is called the terms of trade. When a unit of a country’s good can trade for more units of imported goods than before, we say the country’s terms of trade improve. In the above example, the feasible relative price of a unit of food can be anywhere between 0.625 units of clothing and 0.75 units of clothing. The actual relative price is determined by the relative sizes of the two countries and consumers’ preferences. 5.2. Trade Restrictions §89. Despite the potential benefits of trade, there are numerous trade restrictions in the real world. This is usually because other concerns outweigh the gains from trade. Here are a few reasons why national sometimes restrict trade. a. National security argument. Many countries believe they must rely on themselves in industries vital to national security. These industries include weapons, chemicals, petroleum, and aircraft. However, the national defense argument has been invoked in industries of pens, pottery, peanuts, paper, etc. b. Infant industry argument. Many people believe that new industries in a country should be protected for a while before they have a chance to compete with established foreign competitors. c. Antidumping argument. When a country's firms sell their products at a price lower than their cost and below the price they charge on the domestic market, these firms are dumping. Dumping is unfair for the producers in the export market. Critics argue that dumpers are only trying to drive out local competitors and then charge a higher price. d. Foreign export subsidies argument. e. Low foreign wage argument. f. Saving domestic jobs argument. g. Differences in environmental standards. §90. The usual trade policies to restrict trade flows include tariffs, quotas, and voluntary export restrictions. Tariffs are taxes on imported goods and services. Quotas are quantity limits of goods and services that may be imported during a given period. Voluntary export restrictions are essentially quotas, but they are self-imposed by the exporting country. In addition to tariffs and quotas, measures such as safety standards, labeling requirements, pollution controls, and quality restrictions may have been used by governments to restrict trade flows. 41 §91. The following figure shows the world average tariff level in the last few decades (weighted mean of all products).5 The average tariff level was 2.59% in 2017. 0.09 0.08 0.07 0.06 0.05 0.04 0.03 0.02 0.01 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 0 The following table shows the average tariff level of selected countries in 2017. Argentina Australia Austria Belgium Brazil Canada China Denmark Egypt, Arab Rep. Finland France 7.93 0.89 1.96 1.96 8.59 1.52 3.83 1.96 7.41 1.96 1.96 Germany Greece Hong Kong SAR, China India Ireland Japan Korea, Rep. Lao PDR Mexico New Zealand 1.96 1.96 0 5.78 1.96 2.51 5.05 1.48 1.24 1.35 Norway Singapore South Africa Spain Sweden Turkey Ukraine United Kingdom United States Vietnam 3.13 0.07 4.61 1.96 1.96 3.45 1.9 1.96 1.66 2.69 §92. Now let us consider the effects of a tariff on domestic welfare. We assume the home country is a small country whose actions will not affect the price in the world market. The price of a good in the world market is determined by world demand, 𝐷𝑤 , and world supply, 𝑆𝑊 . Suppose the world price is 𝑃𝑊 . Absent a tariff, the price on the domestic market will be 𝑃𝑊 . At this price, the domestic quantity supplied, 𝑄𝑆0 , is less than the domestic quantity demanded, 𝑄𝐷0 . The imports of the good is 𝑄𝐷0 − 𝑄𝑆0 . The total domestic producer surplus is F. The total consumer surplus is A+B+C+D+E. Now suppose the home country levies a tariff of $T per unit on the good. The domestic effective price increases to 𝑃𝑊 + 𝑇. The domestic quantity supplied increases to 𝑄𝑆1 . The domestic quantity supplied decreases to 𝑄𝐷1 . The imports of the good decrease to 𝑄𝐷1 − 𝑄𝑆1 . In the presence of the tariff, the domestic producer surplus becomes B+F. The consumer surplus is 5 Source: World Bank 42 represented by area A. Area D represents the amount of tariffs collected by the government. The net decrease in social welfare is C+E. 𝑃 𝑃 𝐷𝑊 𝐷 𝑆 𝑆𝑊 A 𝑃𝑊 + 𝑇 𝑃𝑊 𝑃𝑊 B D C E F 𝑄𝑆0 𝑄𝑊 World market 𝑄𝐷1 𝑄𝑆1 𝑄𝐷0 𝑄 Home country market 5.3. Overview of Trade in the World §93. The following exhibit shows trade as a percentage of GDP for the world. The trade is measured as the sum of imports and exports. Over the last fifty years, this share has more than doubled, increasing to 52.83% in 2020. 6 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 2020 2018 2016 2014 2012 2010 2008 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996 1994 1992 1990 1988 1986 1984 1982 1980 1978 1976 1974 1972 1970 0 §94. In 2020, the five largest trading partners with the U.S. in 2020 were China, Mexico, Canada, Japan, and Germany (merchandise only).7 The following table shows more details of the largest trading partners of the US. 6 7 Source: World Bank Source: US Census Bureau 43 All the monetary values are in billion dollars. Rank Country Exports Imports Total Trade ----1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Total, All Countries Total, Top 15 Countries China Mexico Canada Japan Germany Korea, South United Kingdom Switzerland Taiwan Vietnam India Ireland Netherlands France Italy 1,431.6 1,013.1 124.6 212.7 255.4 64.1 57.8 51.2 59.0 18.0 30.5 10.0 27.4 9.6 45.5 27.4 19.9 2,336.6 1,843.5 435.4 325.4 270.4 119.5 115.1 76.0 50.2 74.8 60.4 79.6 51.2 65.5 27.5 43.0 49.5 3,768.2 2,856.7 560.1 538.1 525.8 183.6 172.9 127.2 109.2 92.8 90.9 89.6 78.6 75.0 73.0 70.4 69.4 Percent of Total Trade 100.0% 75.8% 14.9% 14.3% 14.0% 4.9% 4.6% 3.4% 2.9% 2.5% 2.4% 2.4% 2.1% 2.0% 1.9% 1.9% 1.8% §95. In 2019, the US imports $2.38 trillion of goods, which makes it the number one importer in the world. In the same year, the US exports were $1.51 trillion, ranked the second-largest exporter in the world.8 According to the OEC statistics: “The top exports of United States are Refined Petroleum ($84.9B), Crude Petroleum ($61.9B), Cars ($56.9B), Integrated Circuits ($41.4B), and Vehicle Parts ($41.2B), exporting mostly to Canada ($252B), Mexico ($235B), China ($103B), Japan ($70.1B), and Germany ($59.8B).” “The top imports of United States are Cars ($178B), Crude Petroleum ($123B), Computers ($81.9B), Broadcasting Equipment ($81.8B), and Packaged Medicaments ($79.5B), importing mostly from China ($429B), Mexico ($361B), Canada ($314B), Japan ($134B), and Germany ($131B).” 8 Source: OEC 44 6. Market Failure §96. When we were discussing supply and demand at the beginning of this semester, we showed that social welfare reaches its maximum level in equilibrium. The conclusion supports the market mechanism, but we must keep in mind that it is only valid under certain conditions. When these conditions are not satisfied, the market mechanism will not result in the maximum level of social welfare. When the market is not producing the ideal amount of goods and services, there is a market failure, leading to a net loss of social welfare. The nature of market failure is that an individual’s pursuit of self-interest leads to results that are not optimal from the social point of view. §97. When economists discuss an economy's efficiency, they usually check if the economy is Pareto efficient. An economy is Pareto efficient if it is impossible to let some party get better off without making others worse off. For example, suppose Adam has a banana and Bob has an apple. Adam loves apples and does not care about bananas. Bob feels an apple is just as good as a banana. If they trade with each other, Adam will be better off, and Bob is just as happy as before. In this case, the initial allocation is not Pareto efficient since it is possible to let Adam be better off without making Bob worse off. After the exchange, the allocation is Pareto efficient if there are only an apple and a banana and two consumers in the economy. When a reallocation of goods harms no one and makes someone better off, a Pareto improvement occurs in the economy. In the above example, when Adam and Bob trade with each other, Adam is better off, and Bob is not worse off. Therefore there is a Pareto improvement. §98. Pareto efficiency is related to maximum social welfare, but there are differences between them. When we are calculating social welfare, we assign weights to different people’s utility and sum them up. To maximize social welfare, we may need to decrease the welfare level of some parties (e.g., collect taxes from the rich and subsidize the poor). This is different from achieving Pareto efficiency. §99. Market failure may arise from non-competitive markets, externalities, public goods, and asymmetry in information. We will discuss how the market will deviate from the socially optimal equilibrium in each case. 6.1. Non-competitive Markets §100. Let us consider perfect competition, where there is no market $ failure. In a perfectly competitive market, the marginal revenue of a firm is the market price, P. The market price is how much consumers value each unit of the good, so it is the marginal social benefit of a unit of good (SMB). The marginal cost of the firm is the marginal social cost (SMC). P Suppose the competitive firm’s output is 𝑄 ∗ , where P equals MC. At this output level, the marginal social benefit (SMB) equals the marginal social cost. Therefore, social welfare reaches its maximum level at 𝑄 ∗ . MC 𝑄∗ O §101. In non-competitive markets, a firm does not adopt marginal-cost pricing, so the price will be different from the marginal cost. Since the price is the marginal social benefit, the marginal social benefit is not equal to the marginal social cost at the firm’s profit-maximizing output level. Therefore, social welfare is not maximized. Consider a monopoly. The monopolistic output level is 𝑄𝑀 , where MR=MC. The marginal social benefit is the price of the good, which is the height of 𝑀𝑄𝑀 in the graph. The marginal social benefit, P, is greater than the marginal social cost, MC, so more units of goods should be produced to increase social welfare. In fact, the economy should continue to produce until P and MC are equalized at point F. However, the monopolist would not want to do that. As a result, there is market failure, and the deadweight loss equals the area of the triangle GFM. 45 Output Price M Deadweight MC loss MR F Marginal social G benefit Marginal social cost MC=$0.25 P=$12 O D 𝑄𝑀 MR 𝑄𝐶 Quantity 6.2. Externalities §102. Externalities are the positive or negative side effects that actions of one party have on other parties. Here are some examples of positive externalities: • Mary’s beautiful garden benefits the entire neighborhood. • A beekeeper’s bees increase the output of a farm nearby. • A new film company in Hollywood may increase the opportunities for actors to learn from each other and decrease the MC of other film companies. Positive externality: SMB>PMB $ $ Positive externality: SMC<PMC SMB PMB O PMC Marginal externality Marginal externality Hours of Mary’s gardening work O SMC # of films produced by the firm Here are some examples of negative externalities: • Driving a car in an already congested city, which makes it more difficult for others to drive. • Playing loud music in public. • Standing up in a stadium to get a better view of the game, which blocks the view of the people behind the person. When one’s actions have negative externalities, they either cause the SMB to be lower than PMB or cause the SMC to be greater than the PMC. §103. When an individual person or firm is making decisions, they compare PMC and PMB. They choose the number of actions that result in PMC=PMB. Let us take the beekeeper’s choice of bee population as an example. In the following graph, his private optimal bee population will be 𝑄𝑃 . The beekeeper’s activity has positive externalities. Let us assume that raises SMB above PMB. The socially optimal bee population of the beekeeper should be 𝑄 𝑆 . The free market does not result in the socially optimal bee population, so there is a market failure. SMB PMC=SMC $ PMB O 𝑄𝑃 𝑄𝑆 Quantity In general, when private activities have positive externalities, the private output level is less than the socially optimal level; when private activities have negative externalities, the private output level is greater than the socially optimal level. 46 §104. There are a few remedies when the market fails due to externalities. Most of these remedies center on internalizing externalities, which means letting the private party take into consideration the side effects of their actions. To internalize externalities, the government can step in to impose a tax on undesirable actions or subsidize desirable actions with positive externalities. In some cases, Private solutions may work too. Nobel prize laureate Ronald Coase argued that if transaction costs are low, private bargaining will solve the externality problem efficiently. His conclusion is called the Coase theorem. For example, in the case of the optimal bee population, farmers can give beekeepers some benefits to encourage them to keep more bees than they otherwise would. 6.3. Public Goods §105. Depending on its rivalry, a good or service can be a rival good or a non-rival good. A rival good can only be consumed by one person or one group. For example, a chair is a rival good. When one person sits on the chair, others cannot sit on it. A non-rival good can be consumed by multiple people without their consumption experience being affected. For example, national defense is a non-rival good. The fact that Citizen A is being protected by national defense does not affect its protection of Citizen B. §106. Depending on the excludability, a good or service can be an excludable or non-excludable good. A good or service is excludable if the provider can prevent people from consuming it. For example, cable TV is an excludable good. If a consumer does not pay, the cable company can cut the signals to the consumer’s home. A good or service is non-excludable if the provider cannot prevent people from consuming it. Consider lighthouses. Suppose a private company builds a lighthouse that marks some reefs and rocks nearby on the public sea. Since ships have a right to sail on the public sea, the owner of the lighthouse cannot stop the ships and collect a fee for using the lighthouse as a guide. This makes lighthouses a non-excludable good. §107. Goods can be divided into four categories: private goods, common resources, quasi-public goods, and public goods. We will focus on public goods in this chapter. A public good is a nonrival and non-excludable good. National defense is an example of public goods. We know that national defense is nonrival. Now let us consider its excludability with a thought experiment. Suppose a private company plans to provide defense from foreign attacks to residents. Suppose the service needs to ensure that no enemy personnel or attacking assets enter the country. It is difficult for the company to exclude non-paying residents from the protection. Therefore, the company’s service is non-excludable. This makes national defense a public good. Some textbooks refer to quasi-public goods and public goods both as public goods. Rival Nonrival Excludable Nonexcludable Private goods • Grocery • Houses Quasi-Public Goods • Cable TV • Toll road Common resources • Tuna in the ocean • Public pastureland Public Goods • National defense • Police protection • Lighthouses §108. It is more appropriate to call the supply of a public good the quality of good. When the quality of the public good changes, all the people who consume it experience a difference in utility. For example, when a country gets another missile defense system, all citizens feel safer. Now consider a rival good, say, cars. When another car is produced, only the person who gets to use the car experience the difference in utility. Note that it is expensive to improve the quality of most of the non-rival goods that we are familiar with, such as TV programs, operation systems, toll roads, and national defense. §109. There are two problems related to the supply of public goods: the free-riding problem and the drop-in-thebucket problem. Public goods are non-excludable, so some parties can consume the goods without paying. These people are called free riders. They create a free-riding problem. When there is a possibility of free-riding, private firms 47 will not want to supply the good because they will not be able to collect any payments. The discussion about the free-riding problem assumes that people will refuse payment whenever possible. Now let us assume that people are willing to pay as long as the benefit is greater than their payment. Let us conduct a wild thought experiment. Suppose it only takes $10 to solve the mosquito problem. If someone pays $10, nobody will ever be bothered by the mosquitoes, and nobody will ever need to put on pungent and toxic mosquito repellent. It is reasonable to assume that someone will be willing to pay the $10 and be free of the mosquitos forever. This person could free-ride, but her incentive to free-ride is not too strong when the benefit is greater than the payment. The problem with the above thought experiment is that it assumes an unbelievably low cost for a public good. In reality, the amount of payment that individuals can afford will not bring any appreciable changes in the quality of public goods. For example, if a citizen donates $1000 national defense, there will be any noticeable difference in the quality of national defense. This will discourage people from paying for public goods even if they do not play to free-ride. This problem is called the drop-in-the-bucket problem. §110. Given the free-riding problem and the drop-in-the-bucket problem, private firms will not supply public goods or at least enough public goods. It is natural to let the government oversee the public provision of public goods. Note that we are talking about public provision, not public production. The government may contract with private parties to produce the goods. For example, some prisons are run Resident A by private companies. Private reservation §111. We mentioned that there is a single supply level for a value $20 public good. At each level of supply, different consumers have O different reservation values. The social reservation value of the marginal unit is the sum of individual reservation values. Resident B On the graph on the right, we show the decision regarding th Private reservation the 11 aircraft of the US. If this aircraft carrier is $40 value commissioned, US citizens will feel safer. For Citizen A, the increase in safety is worth $20; for Citizen B, $40. Suppose the sum of individual reservation values of the 11 th aircraft is $15 O … 11 Q billion. The social reservation value is shown in the bottom panel. The social reservation value curve is also the demand Economy MC curve of aircraft carriers. $20+$40 The upward-sloping curve in the bottom panel is the +…=$15b Social marginal cost of aircraft carriers. Suppose it is $13 billion for reservation the 11th aircraft carrier. For this aircraft carrier, the social value 13b reservation value is greater than the marginal cost, so it should 11 O 12 Q be produced. national defense We can use this framework to explain why the US does not (measured by carriers) build the 12th aircraft carrier. The actual decision process about building an aircraft carrier is much more complicated than this, but this framework provides a starting point for analysis. This theory of optimal supply of public goods is the Samuelson-Musgrave theory. 6.4. Asymmetric Information §112. Information asymmetry exists when one party knows something that another party does not know. Information asymmetry can lead to at least two problems: adverse selection and moral hazard. They both cause the market to fail to yield the socially optimal outcome. §113. In cases of adverse selection, participants with an information advantage selectively participate in transactions at the expense of the party with a disadvantage in information. In cases of adverse selection, information asymmetry exists prior to the transaction. Here is an example of adverse selection. Suppose you want to buy a used car for $10,000. You post your ad 48 online. Sellers usually have better information about their cars. Only sellers who value their cars below $10,000 will try to sell them. Your reservation value of some of these cars may still turn out to be above $10,000, but the fact that only sellers of lower-quality cars select to do business with you make you think twice before you buy used cars. §114. In cases of moral hazard, after entering a transaction, participants with an advantage in information select actions that may be detrimental to the benefits of the other party. In cases of moral hazard, information asymmetry exists after the transaction. The disadvantaged party may be able to observe the result of the actions of the advantageous party, but it is difficult for them to verify the change in actions selected by the advantageous party. Consider the comprehensive coverage of car insurance policies. It covers damages from theft, fire, hail, or vandalism. When a driver does not have comprehensive coverage, she is likely to try to remember to lock her car and park her car in a safe place. Suppose she feels these considerations are too much. She decides to add comprehensive coverage to her car. After the change in her insurance policy, likely, she will not be careful as before, which increases the probability that her car will be stolen or damaged. Due to the existence of moral hazard, the insurance company has to set the premium high. 49