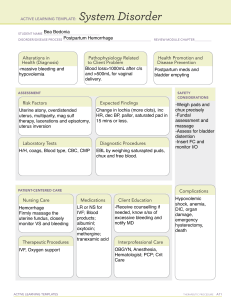

Expert Review ajog.org Intrauterine devices in the management of postpartum hemorrhage Eve Overton, MD; Mary D’Alton, MD; Dena Goffman, MD Obstetrical hemorrhage is a relatively frequent obstetrical complication and a common cause of maternal morbidity and mortality worldwide. The majority of maternal deaths attributable to hemorrhage are preventable, thus, developing rapid and effective means of treating postpartum hemorrhage is of critical public health importance. Intrauterine devices are one option for managing refractory hemorrhage, with rapid expansion of available devices in recent years. Intrauterine packing was historically used for this purpose, with historical cohorts documenting high rates of success. Modern packing materials, including chitosan-covered gauze, have recently been explored with success rates comparable to uterine balloon tamponade in small trials. There are a variety of balloon tamponade devices, both commercial and improvised, available for use. Efficacy of 85.9% was cited in a recent meta-analysis in resolution of hemorrhage with the use of uterine balloon devices, with greatest success in the setting of atony. However, recent randomized trials have demonstrated potential harm associated with improvised balloon tamponade use In low resource settings and the World Health Organization recommends use be restricted to settings where monitoring is available and care escalation is possible. Recently, intrauterine vacuum devices have been introduced, which offer a new mechanism for achieving hemorrhage control by mechanically restoring uterine tone via vacuum suction. The Jada device, which is is FDA-cleared and commercially available in the US, found successful bleeding control in 94% of cases in an initial single-arm trial, with recent post marketing registry study described treatment success following hemorrhage in 95.8% of vaginal and 88.2% of cesarean births. Successful use of improvised vacuum devices has been described in several studies, including suction tube uterine tamponade via Levin tubing, and use of a modified Bakri balloon. Further research is needed with head-to-head comparisons of efficacy of devices and assessment of cost within the context of both device pricing and overall healthcare resource utilization. Key words: antihemorrhagic intervention, blood loss, intrauterine vacuum device, maternal morbidity, obstetrical hemorrhage, obstetrics, postpartum hemorrhage, pregnancy complication, uterine atony, uterine balloon tamponade, Intrauterine packing, Bakri, Jada, Ellavi, ebb, BT-Cath, Suction tube uterine tamponade From the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Columbia University, New York, NY. Received May 31, 2023; revised July 28, 2023; accepted Aug. 10, 2023. M.D. reports serving in a leadership role in the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists II’s Safe Motherhood Initiative, which has received unrestricted funding from Merck for Mothers, and serving on the board of March for Moms. D.G. reports serving on the scientific advisory board for the Jada device through Organon and serving as a principal investigator for the PEARLE and RUBY Jada trials. D.G. also reports participating in the Cooper Surgical Obstetrical Safety Council, creating postpartum hemorrhage education with Laborie, Haymarket, and PRIME, and serving as an editor for UpToDate. E.O. reports no conflict of interest. Corresponding author: Eve Overton, MD. eo2393@cumc.columbia.edu 0002-9378/$36.00 ª 2023 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2023.08.015 S1076 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MARCH 2024 Background Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is a common complication, affecting up to 5% of births, and is a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality worldwide.1e4 In low- and middleincome nations where the majority of maternal deaths occur, more than 30% of maternal deaths are attributable to hemorrhage.4 However, PPH also remains problematic in high-resource settings, including the United States, where hemorrhage accounted for 12.1% of maternal deaths from 2017 to 2019.5 Furthermore, the rate of PPH is increasing and the majority of deaths caused by PPH are considered to be preventable.6,7 Thus, ensuring mechanisms to rapidly and effectively treat PPH is a critically important public health priority. Although there are multiple potential PPH etiologies, 70% to 80% are associated with uterine atony.8 Second-line therapies for refractory hemorrhage caused by atony traditionally include a uterine balloon tamponade (UBT), manual compression maneuvers, interventional radiology procedures, and nonpneumatic antishock garments before operative intervention methods are considered.1,9,10 There has been a recent expansion of UBT devices, and the new development of intrauterine vacuum devices present an alternative (Table). Given the recent change in technology available to manage refractory PPH, the purpose of this review was to provide a summary of the existing devices and their supporting data. Rationale for tamponade techniques Tamponade techniques have been used as second-line therapy for atony-related PPH before surgical intervention, typically with packing or a balloon completely filling the atonic uterine cavity to apply pressure to the bleeding myometrium. There are two theories ajog.org TABLE Summary of selected intrauterine devices for postpartum hemorrhage management Device description Indications assessed in previous studies Plain gauze sponges Standard sterile cloth gauze and sponges Chitosancovered gauze Sterile gauze or packing coated in chitosan or standard gauze with chitosan powder applied Mini-sponge tamponade device Atony Mini-sponges secured within a strong, porous pouch to facilitate manual vaginal removal Device Maximum filling volume Suction level Duration of use Atony, placental pathology N/A N/A 24 h Low cost, readily Concerns available regarding infection risk, inadequate tamponade Atony, placental pathology N/A N/A Maximum described indwelling of 48 h Cost availability, N/A Chitosan limited available granules swell to form plug that data on outcomes aids hemostasis, works in hypothermic conditions and independently of body’s clotting mechanism. N/A N/A 0.5e24 h Rapid use, ease of placement, no fixed shape, thus may conform to irregular uterine cavity 500 mL N/A Max 24 h Rapid instillation Vaginal packing may be needed, from an IV or syringe, drainage intrauterine port allows efflux, drainage port protrudes past latex free, best balloon surface studied UBT Features Limitations Manufacturer reported contraindications Selected outcomes data N/A Maier13, Rezk et al15, Guo et al16 Packing devices Mueller et al18, Rodriguez et al20 Purpose-driven uterine balloon tamponade Bakri Cook Medical Single silicone balloon with central lumen catheter Atony, placental pathology Overton. Intrauterine devices for postpartum hemorrhage management. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2024. Bakri et al22, Said Arterial bleeding requiring surgical exploration or et al23 Embolization, hysterectomy indicated, ongoing pregnancy, cervical cancer, purulent infection, untreated uterine anomaly, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, surgical site that would prohibit device from effectively controlling bleeding (continued) S1077 Expert Review MARCH 2024 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology N/A Availability, limited outcomes data reported following vaginal birth only Dueckelmann et al17; Carles et al19 Summary of selected intrauterine devices for postpartum hemorrhage management (continued) Device Device description Indications assessed in previous studies Maximum filling volume Suction level Duration of use Features Limitations Manufacturer reported contraindications Selected outcomes data Uygur et al24 Arterial bleeding requiring surgical exploration or embolization, hysterectomy indicated, ongoing pregnancy, cervical cancer, purulent infection, untreated uterine anomaly, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, surgical site that would prohibit the device from effectively controlling bleeding, postpartum, vaginal bleeding unaccompanied by uterine bleeding Atony, Single, soft silicone balloon placental pathology with lumen allowing intrauterine blood drainage that allows timely confirmation of the tamponade effectiveness 500 mL N/A Max 24 h Vaginal packing Intrauterine may be required, drainage port limited available flush with balloon surface, outcomes data rapid instillation with IV or syringe, drainage port allows efflux, latex free ebb Complete Tamponade System Atony Double polyurethane balloon system with intrauterine and vaginal balloon components. Separate lumens fill the balloons individually N/A 300 mL (vaginal balloon) 750 mL (intrauterine balloon) Max 24 h Arterial bleeding requiring Two ports Larger max surgical exploration or required for intrauterine embolization, cases with volume, reports inflation, hysterectomy indicated, placement in better ability to open hysterotomy ongoing pregnancy, cervical conform to cancer, purulent infection, discouraged, cavity because limited available untreated uterine anomaly, of balloon disseminated intravascular material, optional outcomes data coagulation, surgical site that use of vaginal would prohibit device from balloon may effective bleeding control, reduce expulsion, postpartum vaginal bleeding rapid inflation unaccompanied by uterine from IV or syringe, bleeding drainage port allows efflux McQuivey et al25 Ellavi Atony Single silicone balloon connected to tubing with IV bag 1000 mL Max 24 h Limited available Low cost, outcomes data preassembled, rapid deployment from IV tubing allows for egress of balloon fluid with resolution of atony while maintaining constant pressure Theron and Mpumlwana31; Parker et al32 N/A Overton. Intrauterine devices for postpartum hemorrhage management. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2024. Bleeding as a result of a perineal, vaginal, or cervical tear, congenital uterine anomaly, uterine rupture, cases of retained placenta (continued) ajog.org BT-Cath Utah Medical Expert Review S1078 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MARCH 2024 TABLE ajog.org TABLE Summary of selected intrauterine devices for postpartum hemorrhage management (continued) Device Device description Indications assessed in previous studies Maximum filling volume Suction level Duration of use Features Limitations Manufacturer reported contraindications Selected outcomes data N/A Keriakos and Mukhopadhyay26 Improvised uterine balloon tamponade Natural latex single balloon Atony, placental pathology 500 e1500 mL N/A Max 24 h Potential for large Off-label use, vaginal packing volume of may be required inflation SengstakenBlakemore Tube Natural latex dual balloon Atony, placental pathology 250 mL (gastric N/A balloon) Max 24 h Two-balloon catheter may aid with placement, drainage port allow efflux Off-label use, Long tip on catheter must be trimmed to aid proper placement N/A Seror et al27 Condom catheter Latex, plastic, lambskin Condom affixed to a straight urinary catheter kit Atony, placental pathology 500 mL N/A Max 24 h Designed for and tested in resource-poor settings, may assemble out of available local resources, low cost N/A Improvised device requiring assembly, need to clamp catheter to avoid efflux of fluid filling balloon, single lumen catheter may not allow drainage of blood from uterus Anger et al36 N/A 8010 mm Hg 1.5e24 h FDA-cleared, purpose-driven, ease of use Cost, availability, <3 cm of cervical dilation, requires 3 cm ongoing intrauterine pregnancy, abnormal uterine anatomy, of cervical active cervical cancer, dilation, unresolved uterine inversion, hysterotomy untreated uterine rupture, must be closed before placement, purulent infection less data for uterine size <34 weeks’ gestation Purwosunu et al47, D’Alton et al43, Gulersen et al49, Goffman et al48 Intrauterine Vacuum Devicesa Jada System Atony Elliptical intrauterine loop made of medical grade silicone lined with vacuum pores oriented inward along the loop covered by a soft shield, balloon-occlusion cervical seal external tubing Overton. Intrauterine devices for postpartum hemorrhage management. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2024. (continued) S1079 Expert Review MARCH 2024 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology Rusch urologic hydrostatic balloon Summary of selected intrauterine devices for postpartum hemorrhage management (continued) Device Device description Indications assessed in previous studies Maximum filling volume Suction level Duration of use Features Limitations Manufacturer reported contraindications Selected outcomes data Rigid uterine retraction cannulas Atony 25 cm length and 12e18 mm in width stainless steel cannula, perforations on uterine portion. The perforations on fundal portion are large and longitudinal and round and small on cervical portion N/A 650 mm Hg Reusable, 10 min on purpose driven suction repeated every h for 3 h Limited outcomes N/A data, unavailable in the United States Samartha Ram et al50, Panicker51 Suction tube uterine tamponade (STUT) Wide-bore (FG24 Atony to FG36) Levin suction tube is connected by suction tubing to an adjustable electronic suction pump or wall suction source. N/A Low cost, 100e200 mm 1 h with a readily available Hg used 20-minute components period of monitoring without suction before removal. N/A Improvised device, requires manual stabilization while initiating vacuum Hofmeyr et al53, Hofmeyr and Singata-Madliki52 Modified Bakri Atony, Single silicone placental balloon filled to pathology 50e100 mL fluid and catheter attached to external nonsterile suction 100 mL 60e70 kPa (450e525 mm Hg) N/A Haslinger et al55 1e24 h Commercially available device, lower device cost than Jada Off-label use, outcomes restricted to single study Expert Review S1080 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MARCH 2024 TABLE FDA, US Food and Drug Adminsitration; IV, intavenous; UBT, uterine balloon tamponade. a All vacuum devices require settings with access to reliable vacuum suction source or suction cannister. Overton. Intrauterine devices for postpartum hemorrhage management. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2024. ajog.org Expert Review ajog.org on how a tamponade achieves hemostasis. The first is that the intrauterine tamponade device exerts direct inwardto-outward pressure greater than systemic arterial pressure, thus inhibiting bleeding from the spiral arteries.11 A more recent theory posits that hydrostatic pressure from the tamponade device directly compresses the uterine arteries, which is similar to the mechanical effect of uterine artery ligation.12 Intrauterine packing The earliest method of uterine tamponade, described in the 19th century, was uterine packing with plain gauze.13,14 Although rates of hemorrhage control reached 100% in some reports, concerns regarding infection risk and inadequate tamponade led to the abandonment of this practice in the 1950s.13 There has been a resurgence in the use of uterine packing with modern materials with results and complication rates similar to a balloon tamponade.15,16 Small studies have described the feasibility of gauze impregnated with hemostatic agents, theoretically providing local procoagulant effects in addition to tamponade.15,17e19 One retrospective cohort study evaluated 78 patients with refractory PPH, and 47 (60.3%) received a chitosan-covered gauze tamponade, whereas 31 (39.7%) received a UBT according to provider discretion. There was no significant difference in the clinical outcomes between groups, including in the mean estimated blood loss (EBL) (2017 mL gauze; 1756 mL UBT; P¼.225), average units of red blood cell (RBC) transfusion received (1.9 units gauze; 1.5 units UBT; P¼.66), intensive care unit admission (44.5% gauze; 61.3% UBT), or hysterectomy (0% gauze vs 9% UBT). This study was, however, limited by sample size and its nonrandomized, retrospective design.17 In addition to impregnated gauze options, a mini-sponge tamponade device made from a trauma dressing has been described. An initial feasibility study of 9 patients has been published with successful placement and control of hemorrhage in all.20 Further data are needed to assess the safety and efficacy of these techniques. Uterine balloon tamponade devices The majority of modern uterine tamponade techniques are balloon devices. The first and best studied of these devices is the Bakri balloon, initially described in the literature in 1999 (Figure 1).21e23 Multiple alternative UBTs specifically designed for obstetrical hemorrhage are commercially available, including the BT-Cath Balloon Tamponade Catheter and the ebb Complete Tamponade System.24,25 Use of a variety of improvised devices has also been described, including modified Foley catheters, the Rusch balloon, condom catheters, and Sengstaken-Blakemore tubes.26e28 With these techniques, an examination is first performed to assess for lacerations, retained products of conception, or other bleeding sources, followed by a sweep of the uterine cavity with removal of any tissue or clot. A balloon is placed manually into the uterus with proper placement above the cervix confirmed manually or via ultrasound. The balloon is then inflated with warm saline until resistance is encountered and the device is securely affixed to the patient’s leg to maintain tamponade.22 All uterinespecific devices offer the option of rapid intravenous- or syringe-based inflation, although data on comparative device deployment times are limited.22,24e26,29 Maximum recommended volumes for the intrauterine balloon vary among devices with the lowest volume Sengstaken-Blakemore balloon at 250 mL and the largest volume Rusch balloon at 1500 mL.25,26 The tamponade test can be performed to confirm successful placement. A positive test is defined by a rapid reduction in bleeding with partial or full inflation of the balloon. A negative test , defined by continued bleeding despite proper UBT placement, should be followed by device removal and timely transition to other inteventions.11 A subset of UBTs include a catheter lumen that allow for drainage and quantification of ongoing blood loss, including the Bakri, ebb, BT-Cath balloon system, and SengstakenBlakemore tube.22,24,25,27 Vaginal packing is often required to maintain appropriate placement, and patients are closely monitored during FIGURE 1 Bakri postpartum balloon tamponade device Image Courtesy of Cook Medical. Used with permission. Overton. Intrauterine devices for postpartum hemorrhage management. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2024. device use. Balloon displacement occurs in approximately 10% of cases.23 Of note, the Sengstaken-Blakemore and ebb devices contain an additional vaginal balloon that may reduce expulsion and the need for vaginal packing.25,27 Deflation and removal may occur up to 24 hours after placement. In one retrospective study, 75% of participants underwent UBT removal more than 12 hours after placement.30 Novel UBTs continue to be developed. The Ellavi System intrauterine balloon is a gravity-fed, free-flow balloon system that maintains constant pressure while allowing fluid to be expelled from the balloon as the uterus contracts, responding to the theoretical criticism that fixed-volume balloons obstruct physiologic uterine contraction (Figure 2).31,32 In addition, this device has a lower cost than other purposedriven UBTs with a current reported cost of 15 USD.33 Uterine balloon tamponade outcomes A recent meta-analysis, including 4791 patients from 91 studies, indicated 85.9% efficacy in resolution of hemorrhage with the use of UBT devices with the greatest success in the setting of atony (87.1%). Success was greater following vaginal birth (87.0%) as MARCH 2024 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology S1081 Expert Review ajog.org FIGURE 2 Ellavi uterine balloon tamponade device and quick setup reference instructions Images courtesy of Sinapi Biomedical. Used with permission. Overton. Intrauterine devices for postpartum hemorrhage management. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2024. opposed to cesarean birth (81.7%).28 However, the evidence on UBT efficacy and safety from randomized and nonrandomized studies is conflicting.34 Observational, nonrandomized, and retrospective trials have generally shown benefit of UBT with good safety profiles and reported complication rates of 6.5%.23,28 However, these study structures carry a risk for reporting bias. In contrast, 2 recent randomized trials have demonstrated potential harm associated with UBT use. A randomized controlled trial compared the use of a condomcatheter UBT and misoprostol with misoprostol alone for PPH following vaginal birth in a low-resource setting. The results of this study were notable for a significantly increased proportion of patients with an EBL >1000 mL (relative risk [RR], 1.52; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.15e2.00; P¼.01) and a higher case fatality rate group (10%; 6/57 compared with 2%; 1/59) in the UBT with misoprostol arm when compared with the misoprostol only arm.35 Similarly, a cluster-randomized trial on the use of a condom catheter UBT performed in low- and middleincome settings showed an association with the increase in the combined incidence of hemorrhage-related surgery and maternal death, with 6.7 events/10,000 deliveries during the control period and 11.6 events/10,000 deliveries during the intervention period (adjusted incidence rate ratio, 4.08; 95% CI, 1.07e15.58).36 It has not been determined whether the disparity in study findings reflects differing research designs, device types, or differential access to other essential components of PPH care. As of 2021, the World Health Organization recommendations for hemorrhage management specify that UBTs should be used only in contexts with access to monitoring for patient clinical status after placement and access to immediate surgical intervention and blood products.37 There are several additional potential drawbacks of UBT techniques. The risk for concealed bleeding above the balloon is a safety concern, particularly with those devices that do not include a drainage port.14 The risk for infection associated with an indwelling foreign body is a concern, although assessment of device-related infection risk is challenging because patients with refractory hemorrhage have high baseline infection rates of 4.6% to 12.2%.23,38e40 The use of UBTs may also extend maternal care in higher S1082 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MARCH 2024 acuity settings during their indwelling time. This care may impact healthcare costs and contribute to known downstream effects of PPH, including delayed patient mobilization, longer parent-child dyad separation, and reduced early lactation success.41,42 Rationale for uterine vacuum devices Recently, intrauterine vacuum-induced hemorrhage control devices have been developed with the goal of rapid and effective control of PPH. The rationale for such devices is to use negative pressure within the uterine cavity to promote contraction, thus allowing coiling of the spiral arteries and reduced blood flow.43 Jada system The only commercially available device in the United States is the Jada System, which was US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)ecleared in August 2020.43e46 This device is made of soft silicone and consists of an elliptical intrauterine loop on the distal end of a tube intended for 1-time use. The intrauterine loop is lined with vacuum pores oriented inward along the loop. A soft shield covers the outside of the loop. A balloon providing a cervical seal is Expert Review ajog.org FIGURE 3 The Jada System intrauterine vacuum-induced hemorrhage-control device The Jada System intrauterine vacuum induced hemorrhage-control device. The device consists of a soft silicone intrauterine loop lined with vacuum pores and covered with a protective shield, a cervical seal, and in-line tubing for inflation of the seal valve and connection to tubing for an external vacuum source. Image courtesy of Organon Health. Used with permission. Overton. Intrauterine devices for postpartum hemorrhage management. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2024. located proximal to this loop with separate tubing. The device connects to sterile vacuum tubing with an inline canister and a regulated vacuum source (Figure 3).44 The device is placed transvaginally and manually for all modes of delivery with placement following hysterotomy closure in the setting of a cesarean delivery. The internal loop is placed to the fundus, oriented in the frontal plane of the body by confirming the seal valve is oriented at either the 3- or 9-o’clock position. After placement, the cervical seal is inflated with 60 to 120 mL of sterile water. The device tubing is then connected to a vacuum at 8010 mm Hg. Bleeding is quantified by the volume drawn into the canister and external tubing (Figure 4). The uterine fundus may be palpated externally or visualized using ultrasound. Device failure is indicated by inability to place the device, failure of the vacuum seal, or ongoing bleeding despite evidence of an effective seal. If device failure is recognized, use should be discontinued promptly and other interventions should be pursued in a timely fashion. Use of the Jada System may be concurrent with uterotonic medications. Removal after successful use may occur 1.5 to 24 hours after placement at the discretion of the provider. Discontinuation of vacuum suction may first be considered at 60 minutes of device use. The device should FIGURE 4 Placement of intrauterine vacuum-induced hemorrhage-control device Placement of intrauterine vacuum-induced hemorrhage-control device after placement with the intrauterine ring within the uterine cavity and the cervical seal prior to inflation with a syringe (1), with low-level vacuum connected to wall suction at 80mm HG þ/- 10 mm Hg (2) and uterine contraction following initiation of suction with blood draining to a wall canister (3). Images courtesy of Organon Health. Used with permission. Overton. Intrauterine devices for postpartum hemorrhage management. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2024. MARCH 2024 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology S1083 Expert Review remain in place for 30 minutes without suction with a deflated cervical seal before removal.44,46 There are several limitations to use of the Jada system. The Jada device should not be considered for the management of retained products of conception or placenta accreta spectrum disorder. Appropriate placement cannot be achieved with less than 3 cm of cervical dilation or via an open hysterotomy. Abnormal uterine anatomy and intrauterine infection are contraindications to its use.44 There are less data on Jada’s use in cesarean deliveries than in vaginal deliveries, and there are minimal data on its use in uterine cavities less the 34 weeks’ gestational age in size.43,47 First-in-humans use of Jada was described in 2016. An initial proof-ofconcept study enrolled 10 patients in Indonesia from 2014 to 2015 who failed first-line PPH medical therapy following vaginal birth. Patients had an EBL of 600 to 1000 mL before device use. In all cases, the device was successfully placed with evacuation of 50 to 250 mL of blood during use and with bleeding control achieved in <2 minutes. No significant safety events were described.47 This preliminary study was followed by an industry-sponsored, prospective, multicenter, single-arm treatment study performed at 12 sites in the United States. The primary efficacy endpoint was control of bleeding not requiring further escalation of treatment. The primary safety endpoint was incidence, severity, and seriousness of device-related adverse events. Patients were included if they failed first-line uterotonics and had atony-related hemorrhage with an EBL of 1000 to 1500 mL before device placement. Of 107 enrolled patients, 106 received treatment. Of these, 85% had vaginal births. A total of 94% of cases had successful bleeding control at a median of 3 minutes and a median EBL during treatment of 110 mL (interquartile range, 75e200 mL). A total of 40 patients (38%) required transfusion of any blood product, whereas 5 patients (5%) received 4 or more units of RBCs. Eight adverse events were reported, which resolved without serious sequelae. Among providers, 98% considered the ajog.org device easy to use, and 97% would recommend its use to others.43 The RUBY trial provides the first post-market registry of real-world use of the Jada. This was an observational study at 16 US centers from October 2020 through April 2022 including 800 patients who were treated with the device (n¼530 vaginal, n¼270 cesarean). Of these, 94.3% had uterine atony. Treatment success was defined as no escalation of care following device utilization and no rebleeding following device removal. Treatment success was observed in 95.8% of vaginal and 88.2% of cesarean births. Mean indwelling time was 4.6 hours and 6.3 hours following vaginal and cesarean birth respectively. In the 49% of patients where time to bleeding control was available, bleeding control was achieved in 5 minutes for 73.8% post vaginal and 62.2% post cesarean. Bleeding recurred after removal in 2.8% of vaginal and 4.1% of cesarean births. Serious adverse events possibly related to the device were cited in 0.4% of cases in both settings.48 There is only 1 study that directly compared outcomes between a UBT and the Jada device. An analysis was conducted of a retrospective cohort of 124 patients across 2 centers who underwent device placement with either a Bakri UBT or the Jada System for refractory PPH owing to atony from 2019 to 2021. The use of Jada was associated with a lower proportion of patients receiving 4 units of RBCs (2.8% vs 20.5%; P.01) and a lower median EBL when compared with the UBT (1500 mL; range, 1175e2000 vs 1850 mL; range, 1400e2200; P<.02). However, this study was limited by its small sample size and nonrandomized, retrospective structure.49 Alternative uterine vacuum devices Although the Jada System is the only purpose-driven uterine vacuum device available in the United States, alternative methods have been described in which novel devices and modifications of existing technology are used. Rigid uterine retraction cannulas The use of reusable, rigid uterine retraction cannulas has been described S1084 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MARCH 2024 in international literature. These are steel or plastic with a length of 25 cm and a width of 12 to 18 mm and contain perforations to establish suction using a bottle or vacuum extraction pump up to 650 mm Hg. In an initial study, 20 patients (16 following vaginal delivery and 4 following cesarean delivery) were enrolled for PPH that did not respond to oxytocin and 1 additional uterotonic. In all cases, bleeding was reportedly controlled within 3 minutes. Detailed safety data were not available for this study.50 A subsequent study of 55 patients (40 vaginal and 15 cesarean deliveries) with PPH were treated with rigid uterine cannulas. This study described 5 cases for which lacerations were the cause of bleeds, 2 cases of clogged devices, and 2 cases for which the attached suction canister required replacement. The author otherwise reported successful hemorrhage control, but outcome details were limited.51 Suction tube uterine tamponade A suction tube uterine tamponade (STUT) is a novel approach described in several feasibility studies. Levin stomach tubing was selected because of its physical characteristics (round tip, flexibility, large pore size) and pricing (<1 USD). In this method, a wide-bore (FG24 to FG36) Levin suction tube is introduced manually into the uterine cavity until the proximal side hole is at least 5 cm beyond the cervix and is held in place while connected to external suction tubing. Suction is then initiated with pressures of 100 to 200 mm Hg. If successful, STUT is continued for 1 hour with a 20minute period of monitoring without suction before removal. An initial, randomized, single-center, double-blind feasibility study enrolled 45 patients who underwent cesarean delivery in 2018 in South Africa. In this study, a 36FG Levin Stomach tube was inserted during cesarean delivery and placed during hysterotomy closure and then attached to suction transvaginally, and patients were randomized to early suction initiated after hysterotomy closure or to late suction initiated after skin closure. The EBL was similar between the groups with a mean EBL of Expert Review ajog.org 149 mL (range, 13e466 mL) in the early suction group and 126 mL (range, 24e462 mL) in the late suction group and a mean difference of 7.3 mL (95% CI, 61 to 75; P¼.433). There were no complications. A subsequent case report described the use of STUT in 3 cases of refractory PPH in which STUT was used successfully to avoid a laparotomy. Most recently, a pilot randomized control trial was published that described the performance of the STUT in comparison with the Ellavi UBT in primary PPH management at 10 centers in South Africa. Participants were allocated in a 1:1 ratio, 12 to STUT and 12 to UBT. Insertion failed in 1 participant in each group and was recorded as difficult in 3 of 10 STUT insertions and 4 of 9 Ellavi insertions. There were 2 laparotomies and 1 intensive care unit admission in the UBT group. Modified Bakri balloon Use of a modified Bakri balloon for uterine vacuum was described in a single study. In a single-center, observational cohort study, 66 patients with primary refractory PPH of any etiology were enrolled between 2017 and 2020. The Bakri balloon was inserted in the same manner as a traditional UBTand inflated with 50 to 100 mL of saline, and the proximal end of the drainage catheter was connected via tubing to a vacuum device with 450 to 525 mm Hg of suction applied. Balloons remained in place on suction for 1 to 24 hours with frequent ultrasound assessment of positioning. All devices achieved adequate suction without equipment failure. The device success rate was 86% in women with uterine atony (n¼44) and 73% in women with placental pathology (n¼22). No adverse events were observed. Local use at authors’ institution At the authors’ institution, we employ both the Bakri intrauterine balloon and Jada System for PPH management within the setting of an algorithm based on hemorrhage stage (Figure 5). As defined by the Safe Motherhood Initiative (SMI) obstetric hemorrhage checklist, hemorrhage is staged by blood FIGURE 5 Example of postpartum hemorrhage stageebased treatment algorithm CBC, complete blood count; CD, cesarean delivery; D&C, dilation and curettage; FFP, fresh frozen plasma; IM, intramuscular; IR, interventional radiology; IV, intravenous; IVH, intravenous hydration; MTP, massive transfusion protocol; OR, operating room; Plt, platelets; POC, products of conception; PPH, postpartum hemorrhage; RBC, red blood cell; T&S, type & screen; T&C, type & cross; TXA, tranexamic acid; VD, vaginal delivery. Overton. Intrauterine devices for postpartum hemorrhage management. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2024. loss and clinical status. Stage 1 hemorrhage reflects blood loss of 1000 mL, while stage 2 hemorrhage is classified as 1000- 1500 mL. Stage 3 hemorrhage reflects an estimated blood loss greater than 1500 mL or hemorrhage accompanied by vital sign abnormalities, evidence of coagulopathy, occult bleeding risk, or transfusion of greater than two units of red blood cells. Finally, cases are categorized as stage 4 hemorrhage when cardiovascular collapse occurs.56 We first consider intrauterine device placement for a stage I PPH, particularly for those patients with contraindications to uterotonics, based on the protocol used in MARCH 2024 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology S1085 Expert Review the premarket trial for Jada FDA clearance.43 We again consider intrauterine device placement with ongoing bleeding in stage II hemorrhage if not previously attempted during stage I. For uterine atony with ongoing bleeding despite fundal massage and the appropriate first-line uterotonics in vaginal deliveries, we prefer Jada, although the Bakri remains acceptable. Jada’s rapid onset of action, ease of identifying device success or failure, and short indwelling time drive this recommendation.43 However, for those cases in which cervical dilation is <3 cm, uterine size less than 34 weeks’ gestation, or a device needs to be employed during a cesarean delivery via a hysterotomy, the Bakri remains preferred.22,44 For other nonuterine atony causes, such as focal placental bed bleeding at the time of cesarean delivery, the Bakri is used.57 For any intrauterine device, continuous evaluation of the device efficacy and ongoing management of hemodynamic status is critically important. If device failure is identified, prompt removal and continuation of other interventions is pursued. We advise assessment in the operating room and consideration of surgical exploration for ongoing blood loss >1500 mL or in the setting of hemodynamic instability.1,10 Future questions Intrauterine devices in the management of PPH are a common and important component of PPH algorithms, however, additional, large-scale, prospective data are needed to establish the safety and efficacy of these devices both in direct comparison with one another and with alternative methods. This is a particular concern in the use of intrauterine vacuum devices when compared with traditional UBTs. Furthermore, details of intrauterine device optimization have also not been established fully. This includes studies on whether device success is affected by manual vs ultrasound-guided placement and device efficacy in combination with other techniques, including uterotonics and compressive sutures. Additional prospective studies are also needed to determine the use of intrauterine ajog.org devices in middle- and low-resource settings. Differential outcomes have been described for traditional UBTs based on the context of use, which may reflect disparities in resources for patient care or variable efficacy of improvised vs purpose-driven devices.28,35,36 Although emerging literature on the use of intrauterine vacuum devices shows promise, there remain significant questions regarding their role in the management of PPH. Most published research to date has included patients with EBLS of 1500 mL.43,47e55 The use of intrauterine vacuums at higher blood loss or in the setting of coagulopathy has yet to be determined. In addition, they do not have established use in the absence of atony. Conversely, there may be a role for vacuum devices early in hemorrhage management algorithms as an alternative to uterotonic medications. However, there is concern that the use of such devices early within PPH treatment algorithms may lead to overuse.58 In addition, there are no current standardized recommendations for antibiotic use during the indwelling time of uterine vacuum devices. Although low rates of puerperal infection have been described to date, significant infection has been noted in rare cases and vacuum devices carry those risks that are inherent to an indwelling foreign body.43 The cost of intrauterine vacuum devices in comparison with alternative methods is an important consideration. Currently, the individual device cost of the Jada System, a single use item, exceeds that of all other available methods at an estimated 1000 USD, which may be prohibitively expensive in lowerresource settings.44 The Bakri, in comparison, has reported costs of 150 to 400 USD in different markets.59 Those improvised vacuum devices and UBTs may cost significantly less with cited costs as low as 1 USD. However, a full analysis of the cost effectiveness of vacuum devices will require assessment of the comparative success of devices in reducing healthcare costs associated with PPH. A recent retrospective study of 1127 patients at a single health system demonstrated increasing healthcare S1086 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MARCH 2024 costs with increasing severity of hemorrhage. The publication describes variable direct costs of $9311 for cases of hemorrhage requiring UBT without transfusion, rising to $27,156 for those cases that required either a transfusion of 4 or more units of RBCs or a hysterectomy.60 Lowering overall costs while optimizing patient outcomes should be a goal of future research. REFERENCES 1. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:e168–86. 2. Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2014;2:e323–33. 3. Maternal mortality. World Health Organization. 2023. Available at: https://www.who.int/ news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality. Accessed May 8, 2023. 4. Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, Gülmezoglu AM, Van Look PF. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet 2006;367:1066–74. 5. Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2021. Published March 16, 2023. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternalmortality/2021/maternal-mortality-rates-2021. htm. Accessed September 1, 2023. 6. Reale SC, Easter SR, Xu X, Bateman BT, Farber MK. Trends in postpartum hemorrhage in the United States from 2010 to 2014. Anesth Analg 2020;130:e119–22. 7. Callaghan WM, Creanga AA, Kuklina EV. Severe maternal morbidity among delivery and postpartum hospitalizations in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:1029–36. 8. Widmer M, Piaggio G, Hofmeyr GJ, et al. Maternal characteristics and causes associated with refractory postpartum haemorrhage after vaginal birth: a secondary analysis of the WHO CHAMPION trial data. BJOG 2020;127: 628–34. 9. Main EK, Goffman D, Scavone BM, et al. National partnership for maternal safety: consensus bundle on obstetric hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:155–62. 10. Althabe F, Therrien MNS, Pingray V, et al. Postpartum hemorrhage care bundles to improve adherence to guidelines: a WHO technical consultation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2020;148:290–9. 11. Condous GS, Arulkumaran S, Symonds I, Chapman R, Sinha A, Razvi K. The “tamponade test” in the management of massive postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol 2003;101: 767–72. 12. Cho Y, Rizvi C, Uppal T, Condous G. Ultrasonographic visualization of balloon placement for uterine tamponade in massive primary postpartum hemorrhage. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2008;32:711–3. Expert Review ajog.org 13. Maier RC. Control of postpartum hemorrhage with uterine packing. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1993;169:317–21. discussion 321e3. 14. Georgiou C. Balloon tamponade in the management of postpartum haemorrhage: a review. BJOG 2009;116:748–57. 15. Rezk M, Saleh S, Shaheen A, Fakhry T. Uterine packing versus Foley’s catheter for the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage secondary to bleeding tendency in low-resource setting: a four-year observational study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2017;30: 2747–51. 16. Guo YN, Ma J, Wang XJ, Wang BS. Does uterine gauze packing increase the risk of puerperal morbidity in the management of postpartum hemorrhage during caesarean section: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015;8:13740–7. 17. Dueckelmann AM, Hinkson L, Nonnenmacher A, et al. Uterine packing with chitosan-covered gauze compared to balloon tamponade for managing postpartum hemorrhage. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2019;240:151–5. 18. Mueller GR, Pineda TJ, Xie HX, et al. A novel sponge-based wound stasis dressing to treat lethal noncompressible hemorrhage. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;73(2Suppl1):S134–9. 19. Carles G, Dabiri C, Mchirgui A, et al. Uses of chitosan for treating different forms of serious obstetrics hemorrhages. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod 2017;46:693–5. 20. Rodriguez MI, Bullard M, Jensen JT, et al. Management of postpartum hemorrhage with a mini-sponge tamponade device. Obstet Gynecol 2020;136:876–81. 21. Bakri YN. Balloon device for control of obstetrical bleeding. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1999;86:S84. 22. Bakri YN, Amri A, Abdul Jabbar F. Tamponade-balloon for obstetrical bleeding. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2001;74:139–42. 23. Said Ali A, Faraag E, Mohammed M, et al. The safety and effectiveness of Bakri balloon in the management of postpartum hemorrhage: a systematic review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2021;34:300–7. 24. Uygur D, Altun Ensari T, Ozgu-Erdinc AS, Dede H, Erkaya S, Danisman AN. Successful use of BT-Cath() balloon tamponade in the management of postpartum haemorrhage due to placenta previa. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2014;181:223–8. 25. McQuivey RW, Block JE, Massaro RA. ebb Complete Tamponade System: effective hemostasis for postpartum hemorrhage. Med Devices (Auckl) 2018;11:57–63. 26. Keriakos R, Mukhopadhyay A. The use of the Rusch balloon for management of severe postpartum haemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol 2006;26:335–8. 27. Seror J, Allouche C, Elhaik S. Use of Sengstaken-Blakemore tube in massive postpartum hemorrhage: a series of 17 cases. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2005;84:660–4. 28. Suarez S, Conde-Agudelo A, BorovacPinheiro A, et al. Uterine balloon tamponade for the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020;222:293.e1–52. 29. Antony KM, Racusin DA, Belfort MA, Dildy GA 3rd. Under pressure: intraluminal filling pressures of postpartum hemorrhage tamponade balloons. AJP Rep 2017;7:e86–92. 30. Einerson BD, Son M, Schneider P, Fields I, Miller ES. The association between intrauterine balloon tamponade duration and postpartum hemorrhage outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216:300.e1–5. 31. Theron GB, Mpumlwana V. A case series of post-partum haemorrhage managed using Ellavi uterine balloon tamponade in a rural regional hospital. S Afr Fam Pract (2004) 2021;63:e1–4. 32. Parker ME, Qureshi Z, Deganus S, et al. Introduction of the Ellavi uterine balloon tamponade into the Kenyan and Ghanaian maternal healthcare package for improved postpartum haemorrhage management: an implementation research study. BMJ Open 2023;13:e066907. 33. Ellavi: A Maternal Health Solution. 2018. Available at: https://ellavi.com/. Accessed July 18, 2023. 34. Kellie FJ, Wandabwa JN, Mousa HA, Weeks AD. Mechanical and surgical interventions for treating primary postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;7:CD013663. 35. Dumont A, Bodin C, Hounkpatin B, et al. Uterine balloon tamponade as an adjunct to misoprostol for the treatment of uncontrolled postpartum haemorrhage: a randomised controlled trial in Benin and Mali. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016590. 36. Anger HA, Dabash R, Durocher J, et al. The effectiveness and safety of introducing condomcatheter uterine balloon tamponade for postpartum haemorrhage at secondary level hospitals in Uganda, Egypt and Senegal: a stepped wedge, cluster-randomised trial. BJOG 2019;126:1612–21. 37. World Health Organization. WHO recommendation on uterine balloon tamponade for the treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2021. 38. Anger HA, Durocher J, Dabash R, et al. Postpartum infection, pain and experiences with care among women treated for postpartum hemorrhage in three African countries: a cohort study of women managed with and without condom-catheter uterine balloon tamponade. PLoS One 2021;16:e0245988. 39. Nagase Y, Matsuzaki S, Kawanishi Y, et al. Efficacy of prophylactic antibiotics in Bakri intrauterine balloon placement: a single-center retrospective analysis and literature review. AJP Rep 2020;10:e106–12. 40. Rani PR, Begum J. Recent advances in the management of major postpartum haemorrhage - a review. J Clin Diagn Res 2017;11: QE01–5. 41. Cohen SS, Alexander DD, Krebs NF, et al. Factors associated with breastfeeding initiation and continuation: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr 2018;203:190–6.e21. 42. Thompson JF, Heal LJ, Roberts CL, Ellwood DA. Women’s breastfeeding experiences following a significant primary postpartum haemorrhage: a multicentre cohort study. Int Breastfeed J 2010;5:5. 43. D’Alton ME, Rood KM, Smid MC, et al. Intrauterine vacuum-induced hemorrhage-control device for rapid treatment of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol 2020;136:882–91. 44. Jada System instructions for use. Organon Health. 2022. Available at: https://www.organ on.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/j/jada/jada_syst em_ifu_blue_seal.pdf. Accessed April 24, 2023. 45. Center for Devices, and Radiological Health. Device approvals, denials and clearances. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Available at: 2022. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/ products-and-medical-procedures/deviceapprovals-denials-and-clearances. Accessed June 14, 2022. 46. D’Alton M, Rood K, Simhan H, Goffman D. Profile of the Jada System: the vacuuminduced hemorrhage control device for treating abnormal postpartum uterine bleeding and postpartum hemorrhage. Expert Rev Med Devices 2021;18:849–53. 47. Purwosunu Y, Sarkoen W, Arulkumaran S, Segnitz J. Control of postpartum hemorrhage using vacuum-induced uterine tamponade. Obstet Gynecol 2016;128:33–6. 48. Goffman D, Rood KM, Bianco A, et al. RealWorld Utilization of an Intrauterine, VacuumInduced, Hemorrhage-Control Device. Obstet Gynecol 2023;142(5):1006–16. 49. Gulersen M, Gerber RP, Rochelson B, Nimaroff M, Jones MDF. Vacuum-induced hemorrhage control versus uterine balloon tamponade for postpartum hemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2023;45:267–72. 50. Samartha Ram H, Shankar Ram HS, Panicker V. Vacuum retraction of uterus for the management of atonic postpartum hemorrhage. IOSR J Dent Med Sci 2014;13:15–9. 51. Panicker TNV. Panicker’s vacuum suction haemostatic device for treating post-partum haemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol India 2017;67:150–1. 52. Hofmeyr GJ, Singata-Madliki M. Novel suction tube uterine tamponade for treating intractable postpartum haemorrhage: description of technique and report of three cases. BJOG 2020;127:1280–3. 53. Hofmeyr GJ, Middleton K, Singata-Madliki M. Randomized feasibility study of suction-tube uterine tamponade for postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2019;146:339–43. 54. Cebekhulu SN, Abdul H, Batting J, et al. “Suction Tube Uterine Tamponade” for treatment of refractory postpartum hemorrhage: internal feasibility and acceptability pilot of a randomized clinical trial. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2022;158:79–85. MARCH 2024 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology S1087 Expert Review 55. Haslinger C, Weber K, Zimmermann R. Vacuum-induced tamponade for treatment of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol 2021;138:361–5. 56. Goffman D, Ananth CV, Fleischer A, et al. Safe Motherhood Initiative Obstetric Hemorrhage Work Group. The new york state safe motherhood initiative: early impact of obstetric hemorrhage bundle implementation. Am J Perinatol 2019;36(13):1344–50. ajog.org 57. Cho HY, Park YW, Kim YH, Jung I, Kwon JY. Efficacy of intrauterine Bakri balloon tamponade in Cesarean section for placenta previa patients. PLoS One 2015;10: e0134282. 58. Madar H, Mattuizzi A, Froeliger A, Sentilhes L. Intrauterine vacuum-induced hemorrhage-control device for rapid treatment of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol 2021;137:1127. S1088 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MARCH 2024 59. Vogel JP, Wilson AN, Scott N, Widmer M, Althabe F, Oladapo OT. Cost-effectiveness of uterine tamponade devices for the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage: a systematic review. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2020;151: 333–40. 60. Hruby G, Oberhardt M, Sutton D, et al. Costs associated with postpartum hemorrhage care based on severity. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2023 [Epub ahead of print].