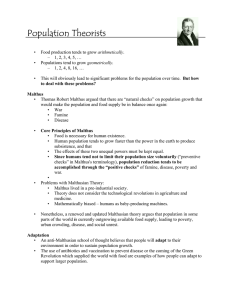

Unit 2: Technology, Population and Growth • The economy is very complex: • What happens in the economy depends on the interdependent behaviours and decisions of millions of individuals (our decisions affect the behaviours of others, and others’ decision affect our own behaviour). • It is impossible to understand the economy by describing every detail of our interactions • We use models to see the big picture. Economic models Models (and theories) abstract from reality to focus attention on the key determinants of an outcome. Equilibrium In economics, many models show how interactions generate an equilibrium, and how a change in conditions affects this equilibrium. What is an equilibrium? • It is a situation that is self-perpetuating • capable of continuing indefinitely. • An equilibrium does not change unless an outside/external force for change is introduced that alters the model’s description of the situation. A new equilibrium A new equilibrium • The steel market is in equilibrium at price P1 and quantity Q1 • The supply of steel falls due to a rise in the price of iron (an input into steel production). • The steel market moves to a new equilibrium price (P2) and new equilibrium quantity (Q2). Abstraction By abstracting from some elements of reality, a (good) map is a useful tool for getting around. Abstraction By abstracting from some elements of reality, a (good) economic model is a useful tool for understanding an economic system. Economic models • Models can be presented verbally, mathematically, or graphically. • Good economic models are clear, accurate, and useful. • This helps us to test economic theories, infer causation, and forecast. Not all model simplifications are justified.. George E.P. Box All models are approximations. Assumptions, whether implied or clearly stated, are never exactly true. All models are wrong, but some models are useful. So, the question you need to ask is not "Is the model true?" (it never is) but "Is the model good enough for this particular application?" George E.P. Box "A theory that explains everything, explains nothing" - Karl Popper (1902 – 1994) History’s hockey stick • Before the 18th and 19th centuries, most people were at or near subsistence levels of income (earned just enough to stay alive). England, 1270 - 2016 History’s hockey stick • If incomes dropped any further, mortality increased (more people died at younger ages). England, 1550 - 2018 England, 1841 - 2018 History’s hockey stick • Population levels were constrained (held back) by the ability of families to provide for their basic necessities (food, shelter, clothing). England, 1270 - 2013 The sustained and dramatic increases in average incomes following the industrial revolution effectively removed the constraint on population growth. Other factors (e.g., scientific advances in medicine) were also important. Today and in the future, lower fertility, rather than mortality, will constrain population growth (peak world population expected at around 2100). Living standards stayed more or less the same for hundreds of years. Population levels were constant. Living standards stayed more or less the same for hundreds of years. Population levels grew very slowly. Living standards grew at an increasing rate. Population levels grew faster. Malthusian economics • Malthus 1798: “Misery for the human race” • Despite gains of technological advances — in particular rising income per capita — nations will never be able to sustain increasing incomes per capita. • Malthus proposed that as people’s income increased, they would have a desire to have more children as affordability within the household increased. • Eventually, population growth would outstrip resources (especially land) and living standards would decrease. • This would then lead to a halt in population growth. Thomas Malthus, 1766-1834 Malthusian economics "Elevated as man is above all other animals by his intellectual facilities, it is not to be supposed that the physical laws to which he is subjected should be essentially different from those which are observed to prevail in other parts of the animated nature.” ~ Thomas Robert Malthus, A Summary View on the Principle of Population (1830) Thomas Malthus, 1766-1834 Malthusian thinking “The power of population is so superior to the power of the earth to produce subsistence for man, that premature death must in some shape or other visit the human race.” Famine thought of as an “effective mechanism for reducing surplus population.” Charles Trevelyan (Assistant Secretary to the Treasury) Malthusian Model • Malthusian theory provides an explanation for why incomes remained around subsistence levels for hundreds of years • Equilibrium à self-perpetuating Hypothesis: o As people’s incomes increase, they will have a desire to have more children à population growth o Eventually, population growth will outstrip the available resources and living standards will decrease o Falling living standards will halt population growth Income levels and population are inversely related Malthusian Model Imagine an agricultural economy that produces just one good, grain. Suppose that the production of grain is very simple i.e. requires little if any capital. Labour and land are factors of production; i.e. they are inputs into the production process. We also suppose that the amount of land is fixed and all of the same quality. The Gleaners, by Jean-Francois (1857) Malthusian Model This model abstracts from most aspects of food production and makes two key assumptions: 1. The production function has a diminishing average product of labour. !"#$%&# '$()*+, (- .%/(*$ = ,(,%. '$()*+, 1*2/#$ (- -%$2#$3 2. Population increases when the average product exceeds subsistence. The Gleaners, by Jean-Francois (1857) Production functions Production functions can be precisely expressed in 3 ways: As an equation: !=# $ i.e. Y is a function of X. As a table: As a figure: Production functions With 800 farmers • The total product is 500,000 kg • The average product of labour is 500,000/800 = 625 kg. With 1600 farmers • The total product is 732,000 kg. • The average product of labour is 732,000/1,600 = 458 kg. This concave production function has a diminishing average product of labour. Kg of grain produced (thousands) 900 800 B 700 600 A 500 400 300 Slope = ∆y/ ∆x = (500,000 – 0)/(800– 0) = 625 200 100 Slope = ∆y/ ∆x = (732,000 – 0)/(1,600 – 0) = 458 0 0 400 800 1200 1600 2000 Number of farmers 2400 2800 Why does the average product diminish? More labour is devoted to a fixed quantity of land. Inferior land is brought into cultivation. Population rises Farmer’s incomes rise Average output per farmer rises Less land per farmer Average output per farmer falls Improvement in technology Farmers’ income fall Equilibrium Equilibrium Subsistence incomes prevail Subsistence incomes prevail Population constant Population constant at higher level “Malthus’ Law” or “the iron law of wages” Is there evidence to support Malthusian theory? Figure 2.1 depicts population and real wages from 1260 to 2001. Between 1260 and 1600, real wages remained constant. Between 1500 and 1600, there was some increase in the population — although it may have just been a return to pre-1350 levels (Black Death killed at least a third of people living in England). There was no sustained nor rapid growth in technology over this period. Is there evidence to support Malthusian theory? Figure 2.18 depicts the relationship between the population and real wages from 1280 to 1600. Negative relationship between real wages and the size of the population. Population growth à decrease in income (Population decline à increase in income) Supports Malthus’ theory Is there evidence to support Malthusian theory? From 1600 to 1800, real wages remained constant, but the population began to grow as technology improved. Britain was still stuck in a Malthusian trap. Escaping the Malthusian trap Britain was stuck in a Malthusian trap from 1280 to 1600 and again from 1740 to 1800. Escaping the Malthusian trap Britain escaped from the Malthusian trap around about 1800. Escaping the Malthusian trap This was because: • the average product of labor grew faster than the population. • improvements in sanitation and medicine improved health in the 19th century. • contraception and family planning slowed population growth in the 20th century. Revising Malthus’ Law 3 conditions are required to stay in the Malthusian trap: • Diminishing average product of labour • Rising population in response to increases in wages • An absence of a permanent improvements in technology to offset the diminishing average product of labour Revising Malthus’ Law 3 conditions are required to stay in the Malthusian trap: • Diminishing average product of labour • Rising population in response to increases in wages • An absence of a permanent improvements in technology to offset the diminishing average product of labour The permanent technological revolution meant that the third condition no longer held and explains why Britain was able to escape the Malthusian trap. Malthusian economics debunked • Ultimately, we know now that Malthus’s model was wrong: a sustained increase in living standards did occur (in Britain and later many/most other countries) • All economic models are wrong in some way. No economic model can explain everything • We need a different model to explain the escape from the “Malthusian trap” And so, seeing as the industrial revolution is the answer…why did it occur?