Muscle Function: Organisms to Molecules - Integrative Biology

advertisement

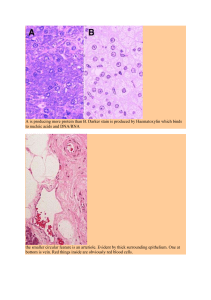

Integrative and Comparative Biology Integrative and Comparative Biology, pp. 1–13 doi:10.1093/icb/icy023 Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology SYMPOSIUM Muscle Function from Organisms to Molecules Kiisa C. Nishikawa,1,* Jenna A. Monroy† and Uzma Tahir* *Center for Bioengineering Innovation and Department of Biological Sciences, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ 86011-4185, USA; †W. M. Keck Science Center, The Claremont Colleges, Claremont, CA 91711-5916, USA From the symposium “Spatial Scale and Structural Heterogeneity in Skeletal Muscle Performance” presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology, January 3–7, 2018 at San Francisco, California. 1 E-mail: Kiisa.Nishikawa@nau.edu Synopsis Gaps in our understanding of muscle contraction at the molecular level limit the ability to predict in vivo muscle forces in humans and animals during natural movements. Because muscles function as motors, springs, brakes, or struts, it is not surprising that uncertainties remain as to how sarcomeres produce these different behaviors. Current theories fail to explain why a single extra stimulus, added shortly after the onset of a train of stimuli, doubles the rate of force development. When stretch and doublet stimulation are combined in a work loop, muscle force doubles and work increases by 50% per cycle, yet no theory explains why this occurs. Current theories also fail to predict persistent increases in force after stretch and decreases in force after shortening. Early studies suggested that all of the instantaneous elasticity of muscle resides in the cross-bridges. Subsequent cross-bridge models explained the increase in force during active stretch, but required ad hoc assumptions that are now thought to be unreasonable. Recent estimates suggest that cross-bridges account for only 12% of the energy stored by muscles during active stretch. The inability of cross-bridges to account for the increase in force that persists after active stretching led to development of the sarcomere inhomogeneity theory. Nearly all predictions of this theory fail, yet the theory persists. In stretch-shortening cycles, muscles with similar activation and contractile properties function as motors or brakes. A change in the phase of activation relative to the phase of length changes can convert a muscle from a motor into a spring or brake. Based on these considerations, it is apparent that the current paradigm of muscle mechanics is incomplete. Recent advances in our understanding of giant muscle proteins, including twitchin and titin, allow us to expand our vision beyond cross-bridges to understand how muscles contribute to the biomechanics and control of movement. Introduction Most biologists believe that muscle physiology is a mature field in which the general principles, comprising the sliding-filament and swinging crossbridge theories, have been adequately described. However, if we take our current ability to predict in vivo muscle forces in humans and animals as a measure of that understanding, then we are forced to accept the fact that we still understand relatively little about how muscles function during dynamic movements. Recent state-of-the-art attempts using Hill models explain only about half of the variation in muscle force during dynamic movements (Lee et al. 2013; Dick et al. 2017). This review seeks to critically evaluate the assumptions on which the current paradigm of muscle mechanics is based, toward the goal of improving the predictive value of muscle models beyond the current state of the art. Muscle models have important applications, not only for biomechanics and organismal biology, but also for human health—particularly for the development of assistive devices to ameliorate the often devastating physical and psychological effects of neuromuscular injury and disease. Therefore, it is imperative to critically evaluate progress in muscle research and to search for better models that not only increase the accuracy of predictions but also provide solutions for important clinical problems. By evaluating the assumptions on which current models and theories are based, and by offering potential alternative hypotheses, we seek to stimulate progress in understanding muscle function. At the outset, it is important to acknowledge that muscle ß The Author(s) 2018. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology. All rights reserved. For permissions please email: journals.permissions@oup.com. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icb/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/icb/icy023/5025086 by Universiteitsbibliotheek Utrecht user on 01 June 2018 2 is complex both structurally and functionally, and that its component parts must work together to produce complex responses to changes in activation and length. The thesis we present here is that there is currently a failure to appreciate the speculative and ad hoc nature of long-held assumptions about crossbridge properties, many of which are unsupported by experimental evidence (i.e., speculative) and historically were invoked to explain particular observations of muscle behavior rather than emerging from an evidence-based biophysical understanding of cross-bridge structure and function (i.e., ad hoc). To the extent that acceptance of speculation as fact prevents consideration of alternative hypotheses, examination of underlying assumptions is a useful exercise to stimulate progress. This review begins by describing Hill models typically used in biomechanics research and evaluating whether their assumptions about the force–length and force–velocity properties of muscle affect their ability to predict in vivo muscle force. Next, several aspects of muscle force production are discussed which have defied explanation by cross-bridge theories and thus have inspired speculative and ad hoc assumptions about cross-bridge properties. These include doublet potentiation, force enhancement, and force depression. Failure of current theories to account for these history-dependent properties is important because they play a significant role in control of dynamic movements (Nishikawa et al. 2013). Finally, the review ends with a discussion of how, in addition to cross-bridges, the giant titin protein may help to explain the activation-, length-, and history dependence of muscle force production; and the types of evidence that would be needed to definitively distinguish among alternative hypotheses to explain these muscle properties. Hill models In contrast to cross-bridge models (Zahalak 2000) that typically specify transition rates among a variable number of cross-bridge states, phenomenological Hill-type muscle models, popularized by Zajac (1989), predict muscle force based on the activation, force–length, and force–velocity properties of a contractile element, typically in series and/or in parallel with purely elastic elements. Although there are many variants (Thelen 2003; McGowan et al. 2013; Millard et al. 2013), the common theme is that muscle force is proportional to activation act(t), the muscle force–length relationship F(l) normalized to a maximum value of 1.0, and the force–velocity relationship F(v) also normalized to the maximum K. C. Nishikawa et al. isometric force Fmax of the muscle (Zajac 1989). An important limitation of these models is that both F–L and F–V relationships can only decrease muscle force for a given level of activation. Hill models with this basic structure are widely used in human and animal biomechanics, often because it is difficult or impossible to measure the model parameters directly—in which case, model validation is elusive if not impossible. Several recent studies have attempted to predict in vivo muscle forces in humans and animals during dynamic movements. In these studies, the forces produced by individual muscles were estimated in vivo using tendon buckles in animals (Lee et al. 2013) or ultrasonography in humans (Dick et al. 2017). Muscle fascicle length was measured using sonomicrometry or ultrasonography, along with electromyography (EMG) as a measure of muscle activation. Yet, even the most comprehensive Hill models, which take into account the different force–velocity properties of fast and slow fibers, performed surprisingly poorly at predicting in vivo muscle forces. In a study of the medial and lateral gastrocnemius muscles of goats during walking and running, Lee et al. (2013) found that Hill models explained only 26–51% of the variation in muscle force, with lower r-squared values for faster gaits. A similar study investigated in vivo forces of the gastrocnemius muscles in humans during cycling over a range of cadences and loads (Dick et al. 2017). In this study, the average r-squared value over all conditions was 0.54, but up to 0.80 at low speed and high muscle activation. Taken together, these studies demonstrate that the models capture only about half of the within- and between-cycle variation in muscle forces during natural movements. There are likely many reasons for the relatively poor performance of Hill models in predicting in vivo muscle force. Sensor noise cannot be excluded and may help to explain why Hill models have higher accuracy in predicting muscle forces in situ than in vivo (Dick et al. 2017). However, there are also some theoretical reasons why Hill models might not be expected to yield accurate predictions of muscle force, including problems associated with applying force–length (F–L) and force–velocity (F–V) relationships, derived under isometric and isotonic or isovelocity conditions, respectively, to dynamic movements in which these conditions do not occur. Force–length relationship With a characteristic plateau in force at intermediate sarcomere lengths and decreasing forces at both Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icb/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/icb/icy023/5025086 by Universiteitsbibliotheek Utrecht user on 01 June 2018 3 Muscle function from organisms to molecules shorter (ascending limb) and longer (descending limb) lengths, the F–L relationship of skeletal muscle is well established and highly consistent across different muscles and preparations (Rockenfeller and Gunther 2017). The standard procedure for producing a length–tension curve, whether in intact muscles, fiber bundles, single muscle fibers, or even single myofibrils or sarcomeres (Rockenfeller and Gunther 2017), is to move the passive preparation to a desired length, then stimulate with supramaximal voltage and frequency or high [Ca2þ] to produce maximum isometric force, and finally to allow relaxation before the procedure is repeated at a different length (Hakim et al. 2013). Therefore, the F–L relationship is a static, not a dynamic, property of muscle. It is important to understand the historical context of the early experiments that sought to determine the F–L relationship (Gordon et al. 1966). At the time, the goal was specifically to test the prediction of the sliding filament theory that the steadystate isometric force of a muscle fiber is proportional to the overlap between thick and thin filaments. In spite of the relatively imprecise methods used at the time for measuring sarcomere length and force (Gordon et al. 1966), the measurements on skeletal muscle sarcomeres corresponded well with predictions from sarcomere geometry (Herzog et al. 2010). Specifically, the results showed that force was proportional to filament overlap predicted based on the lengths of the thick and thin filaments, and that the width of the plateau in force corresponded to the length of the bare zone of thick filaments between adjacent half-sarcomeres where no crossbridges are found (Huxley 1963). It remains a mystery why cardiac sarcomeres, whose geometry is similar to that of skeletal muscles, fail to exhibit a similar F–L relationship (Allen and Kentish 1985). The F–L relationship applies strictly only to isometric contractions at maximal activation, although a similar relationship also holds for isotonic contractions (Gordon et al. 1966). It does not represent muscle force during dynamic length changes, nor was it intended to do so. When muscle length changes during activation, muscle forces depend not only on sarcomere length but also on contractile history (Herzog et al. 2010). When shortening actively, forces are lower than predicted by the isometric F–L relationship, and forces are higher than predicted during active lengthening. At a given sarcomere length, muscle forces can take on a wide range of values during dynamic length changes, from 0 to nearly twice the isometric value, depending on the contractile history. By applying the F–L relationship to dynamic contractions, Hill muscle models will consistently overestimate force during shortening and underestimate force during lengthening. In addition, the F–L relationship applies strictly only to maximum activation which seldom or never occurs during in vivo dynamic movements. The F–L relationship shifts leftward as activation increases (Rack and Westbury 1969; Rassier et al. 1999). The cause of this leftward shift is unknown. It has been suggested that the shift might be due to the lengthdependence of calcium activation (Rassier et al. 1999). However, a recent study suggested that force, rather than calcium concentration, may instead be responsible (Holt and Azizi 2014). The authors further stated that “the effect of absolute force is due to the varying effect of the internal mechanics of the muscle at different activation levels,” but what might constitute these internal mechanics remains unclear. Despite the submaximal activation of muscles during voluntary contractions, models seldom account for this activation-dependent shift in the F–L relationship, which is not predicted on the basis of the sliding filament or cross-bridge theories. Force–velocity relationship Hill’s (1938) original purpose in using isotonic afterloaded contractions to investigate the F–V relationship of muscle was to elucidate properties of the muscle motor under conditions in which contributions of series elastic elements could be excluded. Using Hill’s method, a force–velocity curve is constructed by activating a muscle until it reaches a predetermined (“after”) load. When a given load is reached, the muscle shortens in the absence of contributions from series elastic elements, which due to constant force must remain at a constant length (Caiozzo 2002). To construct a F–V curve, the load is varied systematically, and the initial relatively linear contraction velocity at that load is plotted against the load for which it was measured (Fig. 1). The method itself makes it obvious that the F–V relationship fails to describe the dynamic time-varying behavior of shortening muscles even when the load is constant (Fig. 1). Sandercock and Heckman (1997b) demonstrated that a similar F–V curve can be obtained from isovelocity experiments in maximally activated muscles by taking the average force and velocity of shortening near the muscle optimal length, although the methods give slightly different results in submaximally activated muscles (Holt et al. 2014b). Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icb/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/icb/icy023/5025086 by Universiteitsbibliotheek Utrecht user on 01 June 2018 4 K. C. Nishikawa et al. Fig. 1 After-loaded isotonic paradigm for generating the muscle force–velocity relationship. A muscle is stimulated and contracts isometrically until it reaches a predetermined force (A) at which it shortens (B). Note that the duration of stimulation prior to the onset of shortening increases with the after-load. Force (A) and change in length (B) records for six after-loaded contractions are shown. Numbers refer to corresponding length and force traces from which points on the force–velocity curve (C) were derived. Adapted from Caiozzo (2002). An important question is whether the F–V relationship measured under isotonic (Hill 1938) or isovelocity (Sandercock and Heckman 1997b) conditions applies during in vivo locomotion when neither the load nor the velocity of length changes is constant; several observations suggest not. The first observation comes from predictions of the Hill models themselves (Lee et al. 2013; Dick et al. 2017). Although Lee et al. (2013) and Dick et al. (2017) claim that their two-element Hill model captures general features of the estimated in vivo force, both studies show the same deviation of the models from the in vivo force estimates. In both studies, there is a valley in the force prediction when the in vivo force reaches its maximum value in each movement cycle, suggesting that in vivo force is systematically underestimated. The rates of force development and relaxation are also not well characterized by the model. Similar results were obtained in efforts to predict the force of ex vivo muscles during cyclical contractions (James et al. 1996; Askew and Marsh 1998). Both studies found that forces predicted on the basis of F–L and F–V relationships were lower than observed forces at higher cycle frequencies. Lastly, data from the human vastus lateralis muscles during exercises that involve stretch-shortening cycles (SSCs) also suggest that in vivo forces are larger at a given velocity than predicted by F–V relationships derived from isotonic or isovelocity contractions (Finni et al. 2003). A possible explanation for the discrepancy between the models and data is that during SSCs, elastic energy stored during lengthening can be recovered as kinetic energy to increase shortening speed at a given force, in contrast to isotonic and isovelocity contractions in which there can be no recovery of stored energy. Based on these considerations, it is clear that use of muscle models based on static F–L and F–V properties to predict muscle force production under dynamic conditions has serious limitations. History-dependence of muscle force In addition to fundamental problems with Hill models discussed above, it is also well known that they fail to predict the length- and history-dependence of muscle force (Herzog 1998; Perreault et al. 2003; McGowan et al. 2010, 2013), including both enhancement of force with stretch and depression of force with shortening. In the absence of biological mechanisms to account for these intrinsic muscle properties, phenomenological models have been developed to improve the accuracy of force predictions (Forcinito et al. 1998; Cheng et al. 2000; Lin and Crago 2002). However phenomenological models are no substitute for a deeper understanding, not only because they are unlikely to account for Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icb/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/icb/icy023/5025086 by Universiteitsbibliotheek Utrecht user on 01 June 2018 5 Muscle function from organisms to molecules observations beyond the cases they were developed to explain. The length and history-dependent properties of muscle play an important role in control of movement (Nishikawa et al. 2007, 2013). In elegant experiments, Daley et al. (2009) demonstrated that when naive guinea fowl step into an unexpected hole covered by tissue paper, the force of their muscles (estimated from tendon force buckles) changes tens of milliseconds before any change in muscle activation is observed. These and other observations (Daley and Biewener 2011) suggest that parameters in addition to activation, F–L and F–V relationships play an important role in force production during dynamic movements. In classic experiments, Nichols and Houk (1976) demonstrated that not only central nervous reflexes but also muscle intrinsic properties (“preflexes”) provide stabilization to perturbations. During perturbations, force and length feedback from muscle spindles and tendon organs are used to adjust muscle recruitment to match the altered load (Matthews 1959; Slager et al. 1998). Using surgery to eliminate feedback control from the spinal cord, Nichols and Houk (1976) demonstrated that load compensation is due not only to sensory feedback, but also to intrinsic muscle properties. Experiments using constant-velocity stretch and shortening illustrate the intrinsic adaptive properties, or “preflexes,” exhibited by active muscle (Sandercock and Heckman 1997b). When a muscle is stretched by an applied load, internal muscle stress increases to resist overstretch. Likewise, during unloading, muscles become more compliant. Muscle force adjusts instantaneously in response to changes in load without requiring input from the nervous system (Monroy et al. 2007; Nishikawa et al. 2007). These adjustments are thought to increase stability during the delay in onset of feedback control, and at the limits of muscle recruitment when muscle force is near its minimum or maximum and feedback is ineffective at modulating force output (Nichols and Houk 1976). These and other studies (Rack and Westbury 1974; Richardson et al. 2005) show that muscles behave like non-linear, selfstabilizing “springs” that adapt to perturbations long before reflex loops can exert feedback control. Here, we use the term “spring” to refer to any structure that stores elastic potential energy. These considerations imply that an understanding of motor control depends critically upon history-dependent properties of muscle. The function of muscles as motors has been studied extensively at levels ranging from single molecules (Finer et al. 1995; Howard 1997) to single sarcomeres (Leonard et al. 2010), myofibrils (Leonard and Herzog 2010), muscle fibers (Gordon et al. 1966; Huxley and Simmons 1971), and intact muscles (Abbott and Aubert 1952). The sliding filament theory (Huxley and Niedergerke 1954; Huxley and Hanson 1954) and later the cross-bridge theory (Huxley 1957) together account for the F–L (Gordon et al. 1966) and F–V (Hill 1938; Huxley 1957) properties of muscle. However, a critical evaluation of cross-bridge theories demonstrates that the historydependent properties of muscle continue to elude explanation. A major problem is that, due to the small size and large number of cross-bridges in muscle sarcomeres, it is difficult or impossible to measure their properties directly. While the goal of muscle research should be to predict the macroscopic behavior of muscle from known cross-bridge properties, these properties are instead deduced from the macroscopic behavior of muscle that they seek to explain (Marcucci and Yanagida 2012). Inductive models of muscle contraction are not currently feasible; ad hoc and mostly untestable assumptions about crossbridge properties are required to achieve “predictive” models (see below for numerous examples). This fact demonstrates the likelihood that the theory of muscle contraction is far from complete. In the following paragraphs, several muscle properties that have proved difficult to explain based on the sliding-filament, swinging cross-bridge theory are discussed, including doublet potentiation, force enhancement, and force depression. Testable alternative hypotheses based on a role for the giant titin protein are also considered. In the intervening years between the advent of the sliding filament and cross-bridge theories, numerous ad hoc assumptions about crossbridge function—unsupported by experimental evidence—became entrenched as dogma. Several examples are discussed below. By the time, decades later, that the giant titin protein was discovered (Maruyama 1976), there was little room left for titin in active muscle contraction. The giant size of titin, 1000 times larger than average-sized proteins, also hindered progress on understanding its role in muscle function (Lindstedt and Nishikawa 2017; Nishikawa et al. forthcoming 2018). Doublet potentiation When a single stimulus is added to a train of low frequency stimuli (Fig. 2), the added stimulus (doublet) dramatically and persistently potentiates isometric force (Sandercock and Heckman 1997a). Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icb/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/icb/icy023/5025086 by Universiteitsbibliotheek Utrecht user on 01 June 2018 6 K. C. Nishikawa et al. Fig. 2 Doublet potentiation in mouse soleus muscle at optimal length. The black solid line shows unfused muscle stress at 10 Hz stimulation with no doublet added. The gray dashed line shows potentiated stress when a single stimulus is added 10 ms after the first stimulus. Burke et al. (1970, 1976) referred to this property as “catch-like” due to its resemblance to the property, observed in invertebrate muscles, that tension is maintained for long periods after brief excitation with very little energy expenditure (Hoyle 1983). When doublet potentiation is combined with active stretch and shortening in a work loop experiment (Stevens 1996), muscle force doubles and work increases by 50% per cycle, yet no theory explains why this occurs (Fig. 3). Despite significant attention, the underlying mechanism(s) that produce doublet potentiation remain unexplained. Two primary mechanisms have been proposed: increased sarcoplasmic [Ca2þ] and increased stiffness of elastic elements (BinderMacleod and Kesar 2005). Abbate et al. (2002) demonstrated that an added stimulus transiently increases [Ca2þ] in mammalian muscle, but the increase in force persists for a much longer time than the transient increase in [Ca2þ]. The persistence of force at low [Ca2þ] is not predicted by cross-bridge theories and is also a property of invertebrate catch (Butler and Siegman 2010). An alternative mechanism, in which [Ca2þ] persistently increases the stiffness of an elastic element such as titin in muscle sarcomeres (Binder-Macleod and Kesar 2005), is consistent with observations that doublet potentiation is greatest at short muscle lengths, that shortening during stimulation decreases potentiation whereas stretch during stimulation increases potentiation (Sandercock and Heckman 1997a). Long after the development of the sliding filament and cross-bridge theories, giant elastic proteins were discovered in animal muscles from Caenorhabditis to vertebrates (Dos Remedios and Gilmour 2017; Lindstedt and Nishikawa 2017). It is now apparent that these giant proteins play important roles, not Fig. 3 A single stimulus added during a stretch-shortening cycle doubles muscle force and increases work per cycle by 50%. Force output of mouse soleus muscle stimulated at 30 Hz (black) and with a doublet added 10 ms after the first stimulus (gray). only in invertebrate catch (Yamada et al. 2001) but also in the Frank–Starling law of the heart (Ait-Mou et al. 2016)—the association between the volume of blood entering the ventricles and the force of ventricular contraction. A role for the giant titin protein in muscle passive force is also now well established (Prado et al. 2005). For titin to contribute to force in doublet potentiation, its force and stiffness should increase with calcium influx and remain high when [Ca2þ] decreases between stimuli. Several observations support the idea that titin could perform these functions. The static stiffness of muscle fibers increases during the early stages of muscle activation (Bagni et al. 2002, 2004) and recent studies demonstrate a role for titin (Nocella et al. 2014; Rassier et al. 2015; Cornachione et al. 2016). Furthermore, Leonard and Herzog (2010) demonstrated that titin stiffness increases in active muscle. When single myofibrils are activated by Ca2þ and stretched to a length beyond overlap of the thick and thin filaments (so that cross-bridges per se cannot contribute directly to active force), the force increases more rapidly with stretch than it does in passive myofibrils. When an activated muscle is stretched and then allowed to relax without shortening back to its original length, its titin-based passive tension (Joumaa et al. 2008) remains elevated for up to 3 min after cessation of stimulation (Herzog et al. 2003) perhaps because low levels of Ca2þ remain in the sarcoplasm long after a stimulus (Westerblad and Allen 1994). Recent studies further demonstrate that proteolytic digestion of titin significantly reduces isometric force (Li et al. 2018), Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icb/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/icb/icy023/5025086 by Universiteitsbibliotheek Utrecht user on 01 June 2018 7 Muscle function from organisms to molecules Fig. 4 Force (above) and length (below) of mouse soleus muscle during isovelocity stretch and shortening. The force increases during active stretch, and decreases when stretching stops, reaching a steady state force that is greater than the isometric force at the stretched length. The force decreases during active shortening and redevelops after shortening stops, reaching as steady-state force that is lower than the isometric force at the shorter length. Shades of gray indicate corresponding force and length traces. suggesting that titin force and stiffness increase upon muscle activation. Force enhancement with stretch When a muscle is stretched while active, its force first increases rapidly and then falls after stretching stops, eventually settling to a steady-state force after stretch that is greater than the isometric force at the stretched length (Fig. 3). Early studies understandably assumed that all of the instantaneous elasticity of muscle must reside in the cross-bridges (Huxley and Simmons 1971). Cross-bridge models were developed later that explained the increase in force during active stretch, but these required ad hoc assumptions about both the number of attached cross-bridges (77%; Lombardi and Piazzesi 1990) and the reattachment rates of forcibly attached cross-bridges (200 times higher than for crossbridges that complete a cycle without forcible detachment; Lombardi and Piazzesi 1990). These assumptions are now thought to be unreasonable (Linari et al. 2003), but were justified at the time based on x-ray diffraction and other evidence (Lombardi and Piazzesi 1990; Piazzesi and Lombardi 1995). Recent estimates based on fewer ad hoc assumptions and a much smaller number of attached cross-bridges (20%) suggest that crossbridges account for only 12% of the energy stored by muscles during active stretch (Linari et al. 2003). It was apparent much earlier (Harry et al. 1990) that cross-bridges were unable to account for the history-dependent increase in force that persists after active stretching, commonly referred to as “residual force enhancement” (Edman et al. 1982), leading to development of the sarcomere inhomogeneity theory (Morgan 1990, 1994). The basic idea is that sarcomeres in series vary in their relative strength, that lengthening of muscle on the descending limb of the F–L relationship takes place by rapid, uncontrolled lengthening of the weakest sarcomeres or half sarcomeres, with little or no lengthening of the strongest sarcomeres which, due to their shorter length, account for the increased force. Nearly every prediction of this theory fails (Herzog 2014a, 2014b; Hessel et al. 2017), yet the theory persists. Several studies have suggested that elastic elements in muscle sarcomeres play a role in residual force enhancement (Edman et al. 1982; Herzog and Leonard 2002; Lindstedt et al. 2002; Rode et al. 2009; Leonard and Herzog 2010; Nishikawa et al. 2012; Powers et al. 2014, 2016; Schappacher-Tilp et al. 2015). These observations led to the hypothesis that titin may bind to actin when Ca2þ is present, decreasing titin’s free length and increasing its stiffness (Lindstedt et al. 2002; Rode et al. 2009; Leonard and Herzog 2010; Nishikawa et al. 2012; Powers et al. 2014, 2016; Schappacher-Tilp et al. 2015). Models that incorporate calcium-dependent titin-actin binding perform well at predicting residual force enhancement (Rode et al. 2009; Nishikawa et al. 2012; Schappacher-Tilp et al. 2015), and are no more speculative than cross-bridge models that rely on untested assumptions to account for the same phenomena. Force depression with shortening When a muscle is shortened while active, its force first decreases rapidly and then redevelops, eventually settling to a steady-state force that is lower than the isometric force at the same length (Fig. 3). The amount of force depression increases with the amplitude of shortening, and decreases with the speed of shortening so that force depression is proportional to the work done during shortening (Edman 1975; Marechal and Plaghki 1979). Early hypotheses (Edman 1975; Marechal and Plaghki 1979) included the ideas that cross-bridges are inhibited in direct Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icb/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/icb/icy023/5025086 by Universiteitsbibliotheek Utrecht user on 01 June 2018 8 proportion to the work done during shortening, perhaps because cross-bridges that bind to actin in the new overlap region between myosin and actin that forms during shortening produce less force than those that form in regions of actin that were already in the overlap zone. Since 1979, many studies have added to our understanding of force depression. The hypothesis that force depression is caused by non-uniform shortening of sarcomeres (Edman et al. 1993) was rejected on the basis that force depression was observed even in length-clamped segments of muscle fibers in which shortening was compensated by a servo motor (Granzier and Pollack 1989). The hypothesis that the buildup of metabolic by-products, such as protons or phosphate ions, was rejected due to the relatively short duration of force depression (Herzog 1998) compared with the rate at which these by-products are metabolized. The observation in skinned muscle fibers, that the force after shortening from sarcomere lengths of 2.8–3.0 mm to 2.4 mm was lower than the force before shortening, suggested that not only cross-bridges in the newly formed overlap zone, but also in the old overlap zone are affected (Joumaa et al. 2012). Because fiber stiffness and the rate of ATP hydrolysis (Joumaa et al. 2017) were reduced after shortening, it was suggested that the number of cross-bridges that attach to actin is reduced during active shortening due to deformation of the thin filaments. However, the assumption that the number of attached cross-bridges can be inferred from muscle fiber stiffness (Ford et al. 1981) was later questioned (Howard 1997; Huxley 1998) by the demonstration that most of the muscle stiffness is due to compliance of the thick (Dobbie et al. 1998) and thin filaments (Wakabayashi et al. 1994). Despite the success of Marechal and Plaghki’s (1979) model of force depression at explaining many observations (Rassier and Herzog 2004), one consistent observation remains unexplained. Force depression is inversely proportional to shortening velocity, and is eliminated altogether at the fastest shortening velocities (Marechal and Plaghki 1979). Yet, it seems likely that deformation of thin filaments hypothesized to occur during shortening would depend on shortening amplitude rather than velocity. We note here that a recent X-ray diffraction study suggests that thin filament strain actually increases during shortening, rather than decreasing as might have been expected based on cross-bridge models (Joumaa et al. 2018). An alternative hypothesis is that force depression occurs because strain in titin that develops upon activation (Nishikawa et al. 2012) is reduced by K. C. Nishikawa et al. muscle shortening. Force depression is predicted by models in which an increase in titin stiffness upon activation results from calcium-dependent interactions with actin (Nishikawa et al. 2012; Schappacher-Tilp et al. 2015). This hypothesis is also supported by the observation that a stretch before shortening reduces or eliminates force depression (Fortuna et al. 2017). Work-loops and SSCs The “work loop” technique was introduced by Josephson (1985) in part to provide an experimental system for studying muscle function that more closely emulates in vivo dynamic conditions than the isometric, isotonic, and isovelocity tests that are typically used to investigate mechanisms of muscle contraction in ex vivo experiments. It is striking that force production by muscles is much more complex in work loops, which are difficult or impossible to perform in reduced preparations including skinned fibers or fiber bundles and single myofibrils or sarcomeres due to the requirement for calcium activation rather than electrical stimulation. Some examples are described below. Muscles are complex machines that function not only like motors, but also like brakes, struts, and springs (Dickinson et al. 2000). One of the main determinants of muscle function is the timing of stimulation relative to cyclical length changes (Ahn et al. 2003; Sponberg and Daniel 2012). When stimulated at the onset of shortening (25% phase), toad muscles function like motors, performing positive net work (Ahn et al. 2003). When stimulated at the onset of lengthening (75% phase), they function like brakes, performing negative work and absorbing energy (Hessel and Nishikawa 2017). When stimulated at intermediate phases, muscles function more like springs or struts, performing relatively little net work (Ahn et al. 2003). The results imply that the length at which muscles are activated plays an important role in force production. It is unclear how cross-bridges could contribute to the phase dependence of work, as their force should depend on the amplitude of activation and the F–L and F–V relationships, but not the phase of length changes per se. Although length-dependent activation and/or length-dependence of Ca2þ-sensitivity could modulate cross-bridge forces produced in response to muscle activation at different lengths, it has recently been suggested that titin plays a role in these phenomena as well (Irving et al. 2011; Mateja et al. 2013; Ait-Mou et al. 2016). An explanation for why muscle work and force differ among muscles even under the same Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icb/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/icb/icy023/5025086 by Universiteitsbibliotheek Utrecht user on 01 June 2018 9 Muscle function from organisms to molecules conditions of length and activation remains elusive (James et al. 1995). In cockroaches, one of a pair of leg extensor muscles functions like a motor and the other like a brake, even though these muscles experience similar length changes, are innervated by the same nerve, have the same activation pattern, and their twitch and force–velocity properties are similar (Ahn and Full 2002). On the grounds that muscle shortening is energetically expensive, it was long assumed that tendons provide energy savings in SSCs despite the lack of supporting evidence (Roberts et al. 1997). Yet, a recent study that measured heat production by muscle–tendon units in SSCs compared with isometric contractions (Holt et al. 2014a) found no difference in heat production. These results imply that the muscle itself is responsible for energy savings during SSCs, perhaps because energy stored in the muscle during stretch can be returned during shortening, reducing the energy cost compared with shortening alone (Schaeffer and Lindstedt 2013). Taken together, these examples strongly suggest that factors other than cross-bridges must play an important role in controlling muscle force production during SSCs. A role for titin in active muscle contraction A variety of mechanism for titin’s role in active muscle contraction have become widely accepted (Linke 2018), including maintenance of the axial alignment of thick filaments (Horowits et al. 1986) and rearrangement of thick and thin filaments associated with length dependent regulation of cardiac muscle (Ait-Mou et al. 2016). Yet, these functions require a much greater titin stiffness than has been measured in passive muscle. In fact, a recent study demonstrates that titin transmits most or all of the force in active muscle (Li et al. 2018). Li et al. (2018) created a transgenic mouse in which a specific proteolytic cleavage site from tobacco etch virus was inserted into the distal I-band region of the titin protein near the edge of the A-band. When titin was cleaved in fiber bundles from heterozygous transgenic mice, both the passive and active force was decreased by 50%. At present, it is unclear how titin stiffness can be high enough in active muscle to account for these high forces, although these new results are consistent with hypotheses that titin binds to actin in active muscle (Leonard and Herzog 2010; Nishikawa et al. 2012; Powers et al. 2014), or winds on actin due to rotation of thin filaments (Nishikawa et al. 2012). There is also some evidence that titin interacts with actin at low [Ca2þ]. Kellermayer and Granzier (1996) showed that titin fragments (T2) inhibit motility of actin and reconstituted thin filaments in an in vitro motility assay, and the inhibition depends on [Ca2þ]. A large decrease in actin motility occurred at [Ca2þ] 30 times lower than the [Ca2þ] at which cross-bridges are maximally activated (Kellermayer and Granzier 1996). Although these ideas are currently viewed as speculative (Linke 2018), speculation may be more useful in achieving progress in the field than adherence to ad hoc assumptions regarding cross-bridge properties that have become widely held as facts in the absence of any supporting evidence. The popularity of crossbridge explanations seems largely to be a historical accident, and if titin had been discovered earlier there would doubtless have been considerable speculation that it functions as a spring in active muscle and might contribute to the length- and activationdependent muscle properties that cross-bridges alone cannot explain without ad hoc assumptions. In contrast to cross-bridges which are very small (5.5 nm), titin is a giant molecule. Unlike many speculations about cross-bridge properties, speculations about titin’s role in active muscle are testable hypotheses that can be rejected using difficult but feasible techniques. Dynamic force spectroscopy (Bianco et al. 2007), cosedimentation (Linke et al. 2002), and in vitro motility assays (Kellermayer and Granzier 1996) can be used to measure rupture forces and binding constants of titin–actin interactions. Granzier (2010) suggested that, while difficult technically, stretching active and passive myofibrils labeled with fluorescent titin antibodies could potentially be used to test the hypothesis that interactions with actin reduce or prevent the elongation of titin upon activation, compared with purely passive stretch. In fact, DuVall et al. (2017) recently demonstrated, using an F146 antibody that binds to titin near the A-band, that elongation of titin segments changes upon activation in a manner consistent with a calcium-dependent, but not an actin-dependent increase, in titin stiffness. Recent studies have emphasized the absence of evidence supporting titin–actin interactions in active muscle (Linke 2018). However, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. The main problem with titin-based hypotheses is not their testability per se, but rather the extremely large size of the titin molecule. To definitively rule out a role for titin–actin interactions in eccentric muscle contraction will require investigations of the N2A–PEVK border region, overlooked in previous studies, as well as experiments using additional antibodies that bind Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icb/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/icb/icy023/5025086 by Universiteitsbibliotheek Utrecht user on 01 June 2018 10 to titin in the I-band. Until the critical tests have been performed and the results evaluated, the inquiry into titin’s role in active muscle contraction should be encouraged. Recent research on molluscan muscle shows that the mechanism of catch involves tethering of thick and thin filaments by twitchin, an invertebrate mini-titin (Funabara et al. 2007; Butler and Siegman 2010). In molluscan catch, Ca2þ-influx triggers dephosphorylation of twitchin and binding of twitchin to actin. The twitchin link responsible for molluscan catch adjusts its stiffness during shortening to maintain catch force at a shorter length (Butler and Siegman 2010). Theoretically, what set of properties would titin need in order to account for doublet potentiation, force enhancement, force depression, and the other length- and activation-dependent phenomena described above? To explain these properties would require a sarcomeric spring that (1) decreases its length upon muscle activation (Monroy et al. 2017); (2) increases its stiffness with force development (Leonard and Herzog 2010); and (3) retains a “memory” of the length at which it was activated. While currently viewed as speculative, the winding filament hypothesis was conceived to explain exactly these phenomena (Nishikawa et al. 2012). It seems likely that experiments to definitively test the predictions of the winding filament hypothesis will be completed within the next decade(s). Conclusion The complexity of force production by muscles under dynamic conditions remains largely unexplained by current models based on the sliding filament and cross-bridge theories. It is clear that Hill models are inadequate to predict in vivo, and even ex vivo muscle forces, under dynamic conditions when historydependent muscle properties contribute to muscle force production. In this review, we have attempted to identify factors that may have limited progress in understanding muscle contraction and motor control at molecular and organismal levels. The fields of biomechanics, movement science, and rehabilitation depend on the understanding of muscle properties during dynamic movements. Forward progress depends critically on recognizing the limitations of current theories and exploring testable alternative hypotheses, including a role for the giant titin protein in activated muscle. Acknowledgments We thank Anthony Hessel, Natalie Holt, and Stan Lindstedt, for helpful comments on earlier versions K. C. Nishikawa et al. of this manuscript, and Stan Lindstedt for kind assistance with manuscript preparation. Funding This work was supported by the National Science Foundation [IOS-0732949, IOS-1025806, IOS1456868, IIP-1237878, and IIP-1521231], the W.M. Keck Foundation, and the Technology Research Initiative Fund of Northern Arizona University. References Abbate F, De Ruiter CJ, Offringa C, Sargeant AJ, De Haan A. 2002. In situ rat fast skeletal muscle is more efficient at submaximal than at maximal activation levels. J Appl Physiol 92:2089–96. Abbott BC, Aubert XM. 1952. The force exerted by active striated muscle during and after change of length. J Physiol 117:77–86. Ahn AN, Full RJ. 2002. A motor and a brake: two leg extensor muscles acting at the same joint manage energy differently in a running insect. J Exp Biol 205:379–89. Ahn AN, Monti RJ, Biewener AA. 2003. In vivo and in vitro heterogeneity of segment length changes in the semimembranosus muscle of the toad. J Physiol 549:877–88. Ait-Mou Y, Hsu K, Farman GP, Kumar M, Greaser ML, Irving TC, de Tombe PP. 2016. Titin strain contributes to the Frank–Starling law of the heart by structural rearrangements of both thin- and thick-filament proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:2306–11. Allen DG, Kentish JC. 1985. The cellular basis of the length– tension relation in cardiac muscle. J Mol Cell Cardiol 17:821–40. Askew GN, Marsh RL. 1998. Optimal shortening velocity (V/ Vmax) of skeletal muscle during cyclical contractions: length–force effects and velocity-dependent activation and deactivation. J Exp Biol 201:1527–40. Bagni MA, Cecchi G, Colombini B, Colomo F. 2002. A noncross-bridge stiffness in activated frog muscle fibers. Biophys J 82:3118–27. Bagni MA, Colombini B, Geiger P, Berlinguer Palmini R, Cecchi G. 2004. Non-cross-bridge calcium-dependent stiffness in frog muscle fibers. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286:C1353–7. Bianco P, Nagy A, Kengyel A, Szatmari D, Martonfalvi Z, Huber T, Kellermayer MS. 2007. Interaction forces between F-actin and titin PEVK domain measured with optical tweezers. Biophys J 93:2102–9. Binder-Macleod S, Kesar T. 2005. Catchlike property of skeletal muscle: recent findings and clinical implications. Muscle Nerve 31:681–93. Burke RE, Rudomin P, Zajac FE 3rd. 1970. Catch property in single mammalian motor units. Science 168:122–4. Burke RE, Rudomin P, Zajac FE 3rd. 1976. The effect of activation history on tension production by individual muscle units. Brain Res 109:515–29. Butler TM, Siegman MJ. 2010. Mechanism of catch force: tethering of thick and thin filaments by twitchin. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010:725207. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icb/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/icb/icy023/5025086 by Universiteitsbibliotheek Utrecht user on 01 June 2018 11 Muscle function from organisms to molecules Caiozzo VJ. 2002. Plasticity of skeletal muscle phenotype: mechanical consequences. Muscle Nerve 26:740–68. Cheng EJ, Brown IE, Loeb GE. 2000. Virtual muscle: a computational approach to understanding the effects of muscle properties on motor control (vol 101, pg 117, 2000). J Neurosci Methods 101:117–30. Cornachione AS, Leite F, Bagni MA, Rassier DE. 2016. The increase in non-cross-bridge forces after stretch of activated striated muscle is related to titin isoforms. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 310:C19–26. Daley MA, Biewener AA. 2011. Leg muscles that mediate stability: mechanics and control of two distal extensor muscles during obstacle negotiation in the guinea fowl. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 366:1580–91. Daley MA, Voloshina A, Biewener AA. 2009. The role of intrinsic muscle mechanics in the neuromuscular control of stable running in the guinea fowl. J Physiol 587:2693–707. Dick TJM, Biewener AA, Wakeling JM. 2017. Comparison of human gastrocnemius forces predicted by Hill-type muscle models and estimated from ultrasound images. J Exp Biol 220:1643–53. Dickinson MH, Farley CT, Full RJ, Koehl MA, Kram R, Lehman S. 2000. How animals move: an integrative view. Science 288:100–6. Dobbie I, Linari M, Piazzesi G, Reconditi M, Koubassova N, Ferenczi MA, Lombardi V, Irving M. 1998. Elastic bending and active tilting of myosin heads during muscle contraction. Nature 396:383–7. Dos Remedios C, Gilmour D. 2017. An historical perspective of the discovery of titin filaments. Biophys Rev 9:179–88. DuVall MM, Jinha A, Schappacher-Tilp G, Leonard TR, Herzog W. 2017. Differences in titin segmental elongation between passive and active stretch in skeletal muscle. J Exp Biol 220:4418–25. Edman KA. 1975. Mechanical deactivation induced by active shortening in isolated muscle fibres of the frog. J Physiol 246:255–75. Edman KA, Caputo C, Lou F. 1993. Depression of tetanic force induced by loaded shortening of frog muscle fibres. J Physiol 466:535–52. Edman KA, Elzinga G, Noble MI. 1982. Residual force enhancement after stretch of contracting frog single muscle fibers. J Gen Physiol 80:769–84. Finer JT, Mehta AD, Spudich JA. 1995. Characterization of single actin–myosin interactions. Biophys J 68:291S–6S [discussion 296S–297S]. Finni T, Ikegawa S, Lepola V, Komi PV. 2003. Comparison of force–velocity relationships of vastus lateralis muscle in isokinetic and in stretch-shortening cycle exercises. Acta Physiol Scand 177:483–91. Forcinito M, Epstein M, Herzog W. 1998. Can a rheological muscle model predict force depression/enhancement? J Biomech 31:1093–9. Ford LE, Huxley AF, Simmons RM. 1981. The relation between stiffness and filament overlap in stimulated frog muscle fibres. J Physiol 311:219–49. Fortuna R, Groeber M, Seiberl W, Power GA, Herzog W. 2017. Shortening-induced force depression is modulated in a time- and speed-dependent manner following a stretch-shortening cycle. Physiol Rep 5:e13279. Funabara D, Hamamoto C, Yamamoto K, Inoue A, Ueda M, Osawa R, Kanoh S, Hartshorne DJ, Suzuki S, Watabe S. 2007. Unphosphorylated twitchin forms a complex with actin and myosin that may contribute to tension maintenance in catch. J Exp Biol 210:4399–410. Gordon AM, Huxley AF, Julian FJ. 1966. The variation in isometric tension with sarcomere length in vertebrate muscle fibres. J Physiol 184:170–92. Granzier HL. 2010. Activation and stretch-induced passive force enhancement—are you pulling my chain? Focus on “Regulation of muscle force in the absence of actinmyosin-based cross-bridge interaction”. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299:C11–3. Granzier HL, Pollack GH. 1989. Effect of active preshortening on isometric and isotonic performance of single frog muscle fibres. J Physiol 415:299–327. Hakim CH, Wasala NB, Duan D. 2013. Evaluation of muscle function of the extensor digitorum longus muscle ex vivo and tibialis anterior muscle in situ in mice. J Vis Exp 72:pii: 50183. Harry JD, Ward AW, Heglund NC, Morgan DL, McMahon TA. 1990. Cross-bridge cycling theories cannot explain high-speed lengthening behavior in frog muscle. Biophys J 57:201–8. Herzog W. 1998. History dependence of force production in skeletal muscle: a proposal for mechanisms. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 8:111–7. Herzog W. 2014a. Mechanisms of enhanced force production in lengthening (eccentric) muscle contractions. J Appl Physiol 116:1407–17. Herzog W. 2014b. The role of titin in eccentric muscle contraction. J Exp Biol 217:2825–33. Herzog W, Joumaa V, Leonard TR. 2010. The force–length relationship of mechanically isolated sarcomeres. Adv Exp Med Biol 682:141–61. Herzog W, Leonard TR. 2002. Force enhancement following stretching of skeletal muscle: a new mechanism. J Exp Biol 205:1275–83. Herzog W, Schachar R, Leonard TR. 2003. Characterization of the passive component of force enhancement following active stretching of skeletal muscle. J Exp Biol 206: 3635–43. Hessel AL, Lindstedt SL, Nishikawa KC. 2017. Physiological mechanisms of eccentric contraction and its applications: a role for the giant titin protein. Front Physiol 8:70. Hessel AL, Nishikawa KC. 2017. Effects of a titin mutation on negative work during stretch-shortening cycles in skeletal muscles. J Exp Biol 220:4177–85. Hill AV. 1938. The heat of shortening and the dynamic constants of muscle. Proc R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci 126:136–95. Holt NC, Azizi E. 2014. What drives activation-dependent shifts in the force–length curve? Biol Lett 10:20140651. Holt NC, Roberts TJ, Askew GN. 2014a. The energetic benefits of tendon springs in running: is the reduction of muscle work important? J Exp Biol 217:4365–71. Holt NC, Wakeling JM, Biewener AA. 2014b. The effect of fast and slow motor unit activation on whole-muscle mechanical performance: the size principle may not pose a mechanical paradox. Proc Biol Sci 281:20140002. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icb/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/icb/icy023/5025086 by Universiteitsbibliotheek Utrecht user on 01 June 2018 12 Horowits R, Kempner ES, Bisher ME, Podolsky RJ. 1986. A physiological role for titin and nebulin in skeletal muscle. Nature 323:160–4. Howard J. 1997. Molecular motors: structural adaptations to cellular functions. Nature 389:561–7. Hoyle G. 1983. Forms of modulatable tension in skeletal muscles. Comp Biochem Physiol A Comp Physiol 76:203–10. Huxley AF. 1957. Muscle structure and theories of contraction. Prog Biophys Biophys Chem 7:255–318. Huxley AF. 1998. How molecular motors work in muscle. Nature 391:239–40. Huxley AF, Niedergerke R. 1954. Structural changes in muscle during contraction; interference microscopy of living muscle fibres. Nature 173:971–3. Huxley AF, Simmons RM. 1971. Proposed mechanism of force generation in striated muscle. Nature 233:533–8. Huxley H, Hanson J. 1954. Changes in the cross-striations of muscle during contraction and stretch and their structural interpretation. Nature 173:973–6. Huxley HE. 1963. Electron microscope studies on the structure of natural and synthetic protein filaments from striated muscle. J Mol Biol 7:281–308. Irving T, Wu Y, Bekyarova T, Farman GP, Fukuda N, Granzier H. 2011. Thick-filament strain and interfilament spacing in passive muscle: effect of titin-based passive tension. Biophys J 100:1499–508. James RS, Altringham JD, Goldspink DF. 1995. The mechanical properties of fast and slow skeletal muscles of the mouse in relation to their locomotory function. J Exp Biol 198:491–502. James RS, Young IS, Cox VM, Goldspink DF, Altringham JD. 1996. Isometric and isotonic muscle properties as determinants of work loop power output. Pflugers Arch 432:767–74. Josephson RK. 1985. Mechanical power output from striated muscle during cyclic contractions. J Exp Biol 114:493–512. Joumaa V, Curtis Smith I, Fakutani A, Leonard T, Ma W, Irving T, Herzog W. 2018. Evidence for actin filament structural changes after active shortening in skinned muscle bundles. Biophys J 114:135a. Joumaa V, Fitzowich A, Herzog W. 2017. Energy cost of isometric force production after active shortening in skinned muscle fibres. J Exp Biol 220:1509–15. Joumaa V, MacIntosh BR, Herzog W. 2012. New insights into force depression in skeletal muscle. J Exp Biol 215: 2135–40. Joumaa V, Rassier DE, Leonard TR, Herzog W. 2008. The origin of passive force enhancement in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 294:C74–8. Kellermayer MS, Granzier HL. 1996. Calcium-dependent inhibition of in vitro thin-filament motility by native titin. FEBS Lett 380:281–6. Lee SSM, Arnold AS, de Boef Miara M, Biewener AA, Wakeling JM. 2013. Accuracy of gastrocnemius muscles forces in walking and running goats predicted by oneelement and two-element Hill-type models. J Biomech 46:2288–95. Leonard TR, DuVall M, Herzog W. 2010. Force enhancement following stretch in a single sarcomere. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299:C1398–401. K. C. Nishikawa et al. Leonard TR, Herzog W. 2010. Regulation of muscle force in the absence of actin–myosin-based cross-bridge interaction. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299:C14–20. Li Y, Unger A, von Frieling-Salewsky M, Rivas Pardo JA, Fernandez JM, Linke WA. 2018. Quantifying the titin contribution to muscle force generation using a novel method to specifically cleave the titin springs in situ. Biophys J 114:645a. Lin CC, Crago PE. 2002. Structural model of the muscle spindle. Ann Biomed Eng 30:68–83. Linari M, Woledge RC, Curtin NA. 2003. Energy storage during stretch of active single fibres from frog skeletal muscle. J Physiol 548:461–74. Lindstedt SL, Nishikawa K. 2017. Huxleys’ missing filament: form and function of titin in vertebrate skeletal muscle. Ann Rev Physiol 79:145. Lindstedt SL, Reich TE, Keim P, LaStayo PC. 2002. Do muscles function as adaptable locomotor springs? J Exp Biol 205:2211–6. Linke WA. 2018. Titin gene and protein functions in passive and active muscle. Annu Rev Physiol 80:389–411. Linke WA, Kulke M, Li H, Fujita-Becker S, Neagoe C, Manstein DJ, Gautel M, Fernandez JM. 2002. PEVK domain of titin: an entropic spring with actin-binding properties. J Struct Biol 137:194–205. Lombardi V, Piazzesi G. 1990. The contractile response during steady lengthening of stimulated frog muscle fibres. J Physiol 431:141–71. Marcucci L, Yanagida T. 2012. From single molecule fluctuations to muscle contraction: a Brownian model of A.F. Huxley’s hypotheses. PLoS One 7:e40042. Marechal G, Plaghki L. 1979. The deficit of the isometric tetanic tension redeveloped after a release of frog muscle at a constant velocity. J Gen Physiol 73:453–67. Maruyama K. 1976. Connectin, an elastic protein from myofibrils. J Biochem 80:405–7. Mateja RD, Greaser ML, de Tombe PP. 2013. Impact of titin isoform on length dependent activation and cross-bridge cycling kinetics in rat skeletal muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta 1833:804–11. Matthews PB. 1959. The dependence of tension upon extension in the stretch reflex of the soleus muscle of the decerebrate cat. J Physiol 147:521–46. McGowan CP, Neptune RR, Herzog W. 2010. A phenomenological model and validation of shortening-induced force depression during muscle contractions. J Biomech 43:449–54. McGowan CP, Neptune RR, Herzog W. 2013. A phenomenological muscle model to assess history dependent effects in human movement. J Biomech 46:151–7. Millard M, Uchida T, Seth A, Delp SL. 2013. Flexing computational muscle: modeling and simulation of musculotendon dynamics. J Biomech Eng 135:021005. Monroy JA, Lappin AK, Nishikawa KC. 2007. Elastic properties of active muscle—on the rebound? Exerc Sport Sci Rev 35:174–9. Monroy JA, Powers KL, Pace CM, Uyeno T, Nishikawa KC. 2017. Effects of activation on the elastic properties of intact soleus muscles with a deletion in titin. J Exp Biol 220:828–36. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icb/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/icb/icy023/5025086 by Universiteitsbibliotheek Utrecht user on 01 June 2018 13 Muscle function from organisms to molecules Morgan DL. 1990. New insights into the behavior of muscle during active lengthening. Biophys J 57:209–21. Morgan DL. 1994. An explanation for residual increased tension in striated muscle after stretch during contraction. Exp Physiol 79:831–8. Nichols TR, Houk JC. 1976. Improvement in linearity and regulation of stiffness that results from actions of stretch reflex. J Neurophysiol 39:119–42. Nishikawa K, Biewener AA, Aerts P, Ahn AN, Chiel HJ, Daley MA, Daniel TL, Full RJ, Hale ME, Hedrick TL, et al. 2007. Neuromechanics: an integrative approach for understanding motor control. Integr Comp Biol 47:16–54. Nishikawa KC, Lindstedt SL, LaStayo PC. Forthcoming 2018. Basic science and clinical use of eccentric contractions: history and uncertainties. J Sport Health Sci. Nishikawa KC, Monroy JA, Powers KL, Gilmore LA, Uyeno TA, Lindstedt SL. 2013. A molecular basis for intrinsic muscle properties: implications for motor control. Adv Exp Med Biol 782:111–25. Nishikawa KC, Monroy JA, Uyeno TE, Yeo SH, Pai DK, Lindstedt SL. 2012. Is titin a ‘winding filament’? A new twist on muscle contraction. Proc Biol Sci 279:981–90. Nocella M, Cecchi G, Bagni MA, Colombini B. 2014. Force enhancement after stretch in mammalian muscle fiber: no evidence of cross-bridge involvement. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 307:C1123–9. Perreault EJ, Heckman CJ, Sandercock TG. 2003. Hill muscle model errors during movement are greatest within the physiologically relevant range of motor unit firing rates. J Biomech 36:211–8. Piazzesi G, Lombardi V. 1995. A cross-bridge model that is able to explain mechanical and energetic properties of shortening muscle. Biophys J 68:1966–79. Powers K, Nishikawa K, Joumaa V, Herzog W. 2016. Decreased force enhancement in skeletal muscle sarcomeres with a deletion in titin. J Exp Biol 219(Pt 9):1311–6. Powers K, Schappacher-Tilp G, Jinha A, Leonard T, Nishikawa K, Herzog W. 2014. Titin force is enhanced in actively stretched skeletal muscle. J Exp Biol 217: 3629–36. Prado LG, Makarenko I, Andresen C, Krüger M, Opitz CA, Linke W.A. 2005. Isoform diversity of giant proteins in relation to passive and active contractile properties of rabbit skeletal muscles. J Gen Physiol 126:461–80. Rack PM, Westbury DR. 1969. The effects of length and stimulus rate on tension in the isometric cat soleus muscle. J Physiol 204:443–60. Rack PM, Westbury DR. 1974. The short range stiffness of active mammalian muscle and its effect on mechanical properties. J Physiol 240:331–50. Rassier DE, Herzog W. 2004. Considerations on the history dependence of muscle contraction. J Appl Physiol 96:419–27. Rassier DE, Leite FS, Nocella M, Cornachione AS, Colombini B, Bagni MA. 2015. Non-crossbridge forces in activated striated muscles: a titin dependent mechanism of regulation?. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 36:37–45. Rassier DE, MacIntosh BR, Herzog W. 1999. Length dependence of active force production in skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 86:1445–57. Richardson A, Tresch M, Bizzi E, Slotine JJ. 2005. Stability analysis of nonlinear muscle dynamics using contraction theory. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 5:4986–9. Roberts TJ, Marsh RL, Weyand PG, Taylor CR. 1997. Muscular force in running turkeys: the economy of minimizing work. Science 275:1113–5. Rockenfeller R, Gunther M. 2017. How to model a muscle’s active force–length relation: a comparative study. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 313:321–36. Rode C, Siebert T, Blickhan R. 2009. Titin-induced force enhancement and force depression: a ‘sticky-spring’ mechanism in muscle contractions? J Theor Biol 259:350–60. Sandercock TG, Heckman CJ. 1997a. Doublet potentiation during eccentric and concentric contractions of cat soleus muscle. J Appl Physiol 82:1219–28. Sandercock TG, Heckman CJ. 1997b. Force from cat soleus muscle during imposed locomotor-like movements: experimental data versus Hill-type model predictions. J Neurophysiol 77:1538–52. Schaeffer PJ, Lindstedt SL. 2013. How animals move: comparative lessons on animal locomotion. Compr Physiol 3:289–314. Schappacher-Tilp G, Leonard T, Desch G, Herzog W. 2015. A novel three-filament model of force generation in eccentric contraction of skeletal muscles. PLoS One 10:e0117634. Slager GE, Otten E, Nagashima T, van Willigen JD. 1998. The riddle of the large loss in bite force after fast jaw-closing movements. J Dent Res 77:1684–93. Sponberg S, Daniel TL. 2012. Abdicating power for control: a precision timing strategy to modulate function of flight power muscles. Proc Biol Sci 279:3958–66. Stevens ED. 1996. The pattern of stimulation influences the amount of oscillatory work done by frog muscle. J Physiol 494: 279–85. Thelen DG. 2003. Adjustment of muscle mechanics model parameters to simulate dynamic contractions in older adults. J Biomech Eng 125:70–7. Wakabayashi K, Sugimoto Y, Tanaka H, Ueno Y, Takezawa Y, Amemiya Y. 1994. X-ray diffraction evidence for the extensibility of actin and myosin filaments during muscle contraction. Biophys J 67:2422–35. Westerblad H, Allen DG. 1994. The role of sarcoplasmic reticulum in relaxation of mouse muscle; effects of 2,5di(tert-butyl)-1,4-benzohydroquinone. J Physiol 474:291–301. Yamada A, Yoshio M, Kojima H, Oiwa K. 2001. An in vitro assay reveals essential protein components for the “catch” state of invertebrate smooth muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:6635–40. Zahalak GI. 2000. The two-state cross-bridge model of muscle is an asymptotic limit of multi-state models. J Theor Biol 204:67–82. Zajac FE. 1989. Muscle and tendon: properties, models, scaling, and application to biomechanics and motor control. Crit Rev Biomed Eng 17:359–411. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icb/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/icb/icy023/5025086 by Universiteitsbibliotheek Utrecht user on 01 June 2018