Quantum Mechanics Lecture: Schrödinger Equation & Wave Properties

advertisement

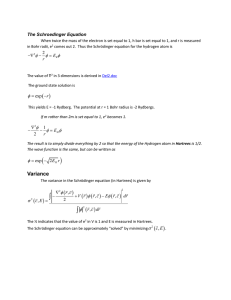

ENGPHYS 2QM3 INTRODUCTION TO QUANTUM MECHANICS Lecture 12 Subject Overview Particle Properties of Particles Wave Properties of Waves 1. Particle Properties of Light 2. Wave Properties of Particles 3. Quantum Mechanics a) Schrödinger Equation b) Potential wells and tunneling 4. Atomic Stability and Structure 5. Statistical Mechanics 6. Condensed Matter What is ‘waving’ in the wavelike behaviour of particles? Historical Footnote • Swiss physicist Felix Bloch recounted the story of how wave mechanics came to be: One day, Nobel laureate Peter Debye said, "Schrödinger, you are not working right now on very important problems anyway. Why don't you tell us some time about that thesis of de Broglie, which seems to have attracted some attention." • And so Schrödinger did. He gave a talk about how French physicist Louis de Broglie postulated that matter also has wave properties, but Debye dismissed the talk as "childish," pointing out that "to deal properly with waves, one had to have a wave equation." • Schrödinger thought about it and set to work on wave mechanics. • By the next talk, Schrödinger said, "My colleague Debye suggested that one should have a wave equation; well, I have found one!" • Years later, Bloch approached Debye and asked him about the encounter. Debye claimed that he had forgotten, but Bloch thought that he was regretful that he goaded Schrödinger into working out the formula rather than doing it himself. Regardless, Debye turned to Bloch and said, "Well, wasn't I right?" Schrödinger's Equation • One of the most unsatisfying aspects of any undergraduate quantum mechanics course is perhaps the introduction of the Schrödinger equation. • After several lectures motivating the need for quantum mechanics by illustrating the new observations at the turn of the twentieth century, usually the lecture begins with: “Here is the Schrödinger equation.” • Sometimes, similarities to the classical Hamiltonian are pointed out, but no effort is made to derive the Schrodinger equation in a physically meaningful way. • This shortcoming is not remedied in the standard quantum mechanics textbooks either. Schrödinger's Equation Here is the Schrödinger Equation: iħ∂Ψ/∂t = –(ħ2/2m)∂2Ψ/∂x2 + VΨ Linear 2nd order PDE Written as 1-d; can be 2- or 3-d Ψ is a function of x and t, i.e. Ψ(x,t) Ψ(x,t) is a scalar and is a complex number in general Schrödinger's Equation Schrödinger's equation cannot be derived from other basic principles of physics; it is a basic principle in itself. i.e. we assert it we test it (vs. experiment) we begin to trust it we look for flaws in it (via experiment) we don’t find any we begin to accept it. Related Quote "At first, people refuse to believe that a strange new thing can be done, and then they begin to hope it can be done, then they see it can be done- then it is done, and all the world wonders why it was not done centuries ago." -- Frances Hodgson Burnett Schrödinger's Equation Same is true for Newton’s Laws of Motion Classical Mechanics is the limiting theory of the more general Quantum Mechanics. Newton’s Laws of Motion can be derived from Schrödinger's equation with some simple assumptions (Ehrenfest theorem). Therefore Schrödinger's equation is the governing equation for particles (i.e. m≠0). Schrödinger's Equation Many ways to demonstrate plausibility of Schrödinger's equation. Easiest to start with a travelling wave in complex notation: Ψ(x,t) = A e– i(ωt – kx) Transform from (ω, k) to (E, p) Schrödinger's Equation Transform from (ω, k) to (E, p) E = hf = ħω [ħ≡h/2π] k = 2π/λ = 2π(p/h) = p/ħ ωt – kx = (E/ħ)t – (p/ħ)x = (Et – px)/ħ Ψ(x,t) = A e– i(ωt – kx) Ψ(x,t) = A e– (i/ħ)(Et – px) Schrödinger's Equation For the wavefunction: Ψ(x,t) = A e– (i/ħ)(Et – px) Can extract E and p via derivatives: ∂Ψ(x,t)/∂t = – (iE/ħ)A e– (i/ħ)(Et – px) ∂Ψ(x,t)/∂t = – (iE/ħ) Ψ(x,t) EΨ(x,t) = iħ∂Ψ(x,t)/∂t Recall: i2 = –1 i = –1/i Schrödinger Equation For the wavefunction: Ψ(x,t) = A e– (i/ħ)(Et – px) ∂Ψ(x,t)/∂x = (ip/ħ)A e– (i/ħ)(Et – px) ∂Ψ(x,t)/∂x = (ip/ħ) Ψ(x,t) pΨ(x,t) = (ħ/i) ∂Ψ(x,t)/∂x pΨ(x,t) = –iħ ∂Ψ(x,t)/∂x pΨ(x,t) = –iħ ∂/∂x Ψ(x,t) Don’t need this now, but save for later Schrödinger's Equation Repeating: ∂Ψ(x,t)/∂x = (ip/ħ)A e– (i/ħ)(Et – px) ∂2Ψ(x,t)/∂x2 = (ip/ħ)2A e– (i/ħ)(Et – px) ∂2Ψ(x,t)/∂x2 = –(p/ħ)2 Ψ(x,t) p2 Ψ(x,t) = –ħ2 ∂2Ψ(x,t)/∂x2 Schrödinger's Equation Ψ(x,t) = A e– (i/ħ)(Et – px) Classically for a particle, we expect a simple result like: E = K + V = p2/2m + V(x,t) So it is consistent to multiply by Ψ: EΨ = p2Ψ/2m + VΨ Schrödinger's Equation EΨ = p2Ψ/2m + VΨ EΨ(x,t) = iħ∂Ψ(x,t)/∂t p2 Ψ(x,t) = –ħ2 ∂2Ψ(x,t)/∂x2 iħ∂Ψ(x,t)/∂t = –(ħ2/2m) ∂2Ψ(x,t)/∂x2 + V(x,t)Ψ(x,t) iħ∂Ψ/∂t = –(ħ2/2m)∂2Ψ/∂x2 + VΨ iħ∂Ψ/∂t = –(ħ2/2m)∇2Ψ+ VΨ Question Why wasn’t this a proof? Schrödinger's Equation 1. We only demonstrated this for a travelling wave, which is particularly unlike a particle. 2. We are assuming validity for any potential V(x,t), i.e. for any force that leads to that potential. Schrödinger's Equation cannot be proven in general. Brief History 1926: Schrödinger introduces his equation. 1933: Schrödinger receives Nobel prize in Physics "for the discovery of new productive forms of atomic theory" Schrödinger's Equation iħ∂Ψ/∂t = –(ħ2/2m)∂2Ψ/∂x2 + VΨ Schrödinger's Equation is a linear, 2nd order partial differential equation, a function of Ψ(x,t) which is a complex scalar, though x can be a 3-d vector. Note that coefficients are not necessarily constant – i.e. V(x,t). Schrödinger's Equation is a wave equation – clear from the way we constructed it from plane waves. Schrödinger's Equation iħ∂Ψ/∂t = –(ħ2/2m)∂2Ψ/∂x2 + VΨ Other wave equations: ∂2P/∂x2 = (1/v2) ∂2P/∂t2 ∇2E = (1/c2)∂2E/∂t2 ∇2B = (1/c2)∂2B/∂t2 Schrödinger's Equation Some similarities to other wave equations, but differences too: • Leads to QM version of E = p2/2m + V • Does not directly lead to fλ = v • Depends on m, by construction – only for particles with mass, not photons • Gives complex wavefunctions, Ψ. Acceptable because we only measure |Ψ|2 Schrödinger's Equation iħ∂Ψ/∂t = –(ħ2/2m)∂2Ψ/∂x2 + VΨ Schrödinger's Equation is linear in Ψ. Therefore solutions obey the superposition principle, as do other wave phenomena. i.e. if Ψ1 and Ψ2 are solutions, then any linear combination is also a solution: Ψ = aΨ1 + bΨ2 Waves Water waves, on surface of water Sound waves, in air, liquid, solid Surface Acoustic Waves (SAW) on surface of a solid and many others… Electromagnetic waves in vacuum or in a medium. Waves of What? What is oscillating in a particle wave?? There is no field corresponding to Ψ like E and B. Next week will discuss the ‘probabilistic interpretation of the wavefunction’ Assume a wavefunction, Ψ(x,t), which is a complex scalar field. Ψ(x,t) is oscillating. But what is Ψ(x,t) ?? Probability Function Ψ(x,t) can be positive, negative, and even a complex number (which is not in itself measurable). But |Ψ(x,t)|2 is always a real positive number, like a wave intensity (which generally is measurable). Norm of a complex number Let Ψ = a + ib Ψ* = a – ib a, b real complex conjugate |Ψ|2 = Ψ*Ψ |Ψ|2 = (a – ib)(a + ib) |Ψ|2 = a2 + b2 Always a real positive number. Ψ(x,t) is a complex scalar field Return to Schrödinger’s equation: iħ∂Ψ/∂t = –(ħ2/2m)∂2Ψ/∂x2 + VΨ By construction, one solution is: Ψ(x,t) = A e– (i/ħ)(Et – px) Note that Ψ(x,t) = A sin((Et – px)/ħ) Ψ(x,t) = A cos((Et – px)/ħ) are not solutions to this wave equation! Ψ(x,t) is a complex scalar field Question: does Ψ(x,t) have to be a complex scalar field? Quite a hotly debated topic for a very long time. See “Quantum Mechanics Must Be Complex”, posted on Avenue Standard Argument (1/4) iħ∂Ψ/∂t = –(ħ2/2m)∂2Ψ/∂x2 + VΨ Let Ψ = Ψ1 + iΨ2, where Ψ1 and Ψ2 are real Substitute into Schrödinger's Equation Separate real and imaginary terms iħ∂Ψ/∂t = –(ħ2/2m)∂2Ψ/∂x2 + VΨ iħ∂(Ψ1+iΨ2)/∂t = –(ħ2/2m)∂2(Ψ1+iΨ2)/∂x2 + V(Ψ1+iΨ2) Standard Argument (2/4) Separate real and imaginary terms: -ħ∂Ψ2/∂t = –(ħ2/2m)∂2Ψ1/∂x2 + VΨ1 iħ∂Ψ1/∂t = –i(ħ2/2m)∂2Ψ2/∂x2 + iVΨ2 -ħ∂Ψ2/∂t = –(ħ2/2m)∂2Ψ1/∂x2 + VΨ1 ħ∂Ψ1/∂t = –(ħ2/2m)∂2Ψ2/∂x2 + VΨ2 What do we learn from this? Standard Argument (3/4) Schrödinger's Equation with a complex Ψ is equivalent to 2 coupled differential equations for Ψ1 and Ψ2 (similar to E and B in Maxwell’s equations) So Ψ did not need to be complex [in this argument]. It is just a convenient way to carry along 2 related variables. Standard Argument (4/4) Instead we could have worked with its real and imaginary parts, but they have no physical significance, unlike E and B. In the end we only care about Ψ*Ψ = (Ψ1 + iΨ2) (Ψ1 - iΨ2) = Ψ12 + Ψ22 and we do not need Ψ1 and Ψ2 separately. So, it is better to work with a complex Ψ What is ‘waving’ in the wavelike behaviour of particles? If you are still wondering, stay tuned for next week Conclusion Particle motions are as described by Newton, with relativistic corrections by Einstein. At the same time… Particles also have a wave-like property, described by Schrödinger's Equation. “Wave-particle duality”