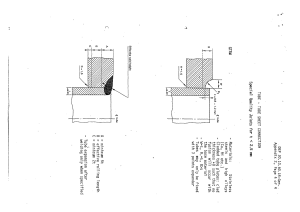

Nutrition Nutrition is a basic component of health and is essential for normal growth and development, tissue repair and maintenance, cellular metabolism, and organ function. The main focus of nutrition both oral and enteral or parenteral is on balancing the 6 basic nutrients, three that are energy giving (carbohydrates, protein, lipids) and three are needed to regulate body processes (vitamins, minerals, water). Refer to your nutrition class for the sources, functions, and significance of these nutrients (See posted sources). Emphasis should be on nutrient dense rather than energy dense foods. Factors affecting food habit Physiologic and physical factors: stage of development, state of health, medications Sociocultural, and psychosocial factors influencing food choices include culture, religion, tradition, education, politics, social status, food ideology Vegetarian diets Vegetarian diet consists predominantly of plant foods: Ovolactovegetarian (avoids meat, fish, and poultry, but eats eggs and milk) Lactovegetarian (drinks milk but avoids eggs) Vegan (consumes only plant foods) Vegans lack complete proteins in single foods, although they can use complementary proteins from two or more foods to get all the amino acids. Knowledge of complementary proteins is necessary. They are at risk for vitamin B12 deficiency because it is available only from animal sources. Encourage vegetarians to incorporate foods enriched with vitamin B 12 or and/or take vitamin B12 supplements. Nutritional Assessment 1 Nutrient needs change in relation to growth, development, activity, and agerelated changes in metabolism and body composition and influences growth and development throughout the life cycle. Nutritional requirements depend on many factors. Individual caloric and nutrient requirements vary by stage of development, body composition, activity levels, pregnancy and lactation, and the presence of disease. Nutritional assessment is a systematic approach used to identify the patient’s actual or potential needs, formulate a plan to meet those needs, initiate the plan, and evaluate the effectiveness of the plan. Combine multiple objective measures with subjective measures related to nutrition to adequately screen for nutritional problems. Identification of risk factors such as unintentional weight loss, presence of a modified diet, or the presence of altered nutritional symptoms (i.e., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation) requires nutritional consultation. Assess patients for malnutrition when they have conditions that interfere with their ability to ingest, digest, or absorb adequate nutrients. No single laboratory or biochemical test is diagnostic for malnutrition. Nurses can collect nutritional assessment data through history taking (diet recall, medical, socioeconomic data), physical assessments (inspection, palpation, auscultation, percussion), Anthropometric and laboratory data. Body Mass Index (BMI) is a reliable indicator of total body fat stores. Calculate body mass index (BMI) by dividing the patient’s weight in kilograms by height in meters squared: weight (kg) divided by height 2 (m2). Waist measurement is a good indicator of abdominal fat. Overweight and obesity is caused by multiple factors. A person with a BMI below 18.5 is underweight, a BMI of 18.5 to 24.9 is a healthy weight, a BMI of 25 to 29.9 indicates an overweight person, a BMI of 30 or greater indicates obesity, and a BMI of 40 or greater indicates extreme obesity. BMI also provides an estimation of relative risk for diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension. ***Note MyPlate, Food labels, & Dietary guidance of America. On food labels, note serving sizes and differentiate it from portion size. Daily values are based on percentages of a diet consisting of 2000 kcal/day for adults and 2 children 4 years or older. Diagnosis Nursing diagnoses may be related to actual nutrition problems (e.g., inadequate intake) or to problems that place the patient at risk for nutritional deficiencies such as oral trauma, severe burns, and infections. Risk for aspiration Diarrhea Constipation Deficient knowledge Readiness for enhanced nutrition Feeding self-care deficit Impaired swallowing Imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements Imbalanced nutrition: more than body requirements Goals/Outcomes: Explore patients’ feelings about their weight and diet and help them set realistic and achievable goals. ***Pause & Think Diagnosis: Risk for aspiration related to impaired swallowing Goal: will receive adequate nutrients through enteral tube feeding without aspiration by the time of discharge. Outcomes: Brainstorm 2 expected outcomes for the above goal Nursing Interventions Meeting nutritional goals requires input from the patient and the multidisciplinary team. Consult with an Speech therapists, Registered dietician, pharmacist, and/or occupational therapist about patients with dysphagia, as well as those who need ongoing nutritional assessment and interventions to meet their nutritional needs. When patients have difficulty feeding themselves, occupational therapists work with them and their families to identify assistive devices. Devices such as utensils with large 3 handles and plates with elevated sides help a patient with self-feeding. Types of Clinical or Therapeutic Diets Health care providers order a gradual progression of dietary intake or therapeutic diet to manage patients’ illness (see posted therapeutic diet) Providing an environment that promotes nutritional intake includes keeping a patient’s environment free of odors, providing oral hygiene as needed to remove unpleasant tastes, and maintaining patient comfort. Offering smaller, more frequent meals often helps. In addition, certain medications affect dietary intake and nutrient use. When a patient needs help with eating, it is important to protect his or her safety, independence, and dignity. Clear the table or over-bed tray of clutter. Assess his or her risk of aspiration. Patients with dysphagia are at risk for aspiration and need more assistance with feeding and swallowing. Before assisting the patient, confirm the type of diet that has been ordered for the patient. Also, it is important to assess for any food allergies and religious or cultural preferences. Check to make sure the patient does not have any scheduled laboratory or diagnostic studies that may impact whether he or she is able to eat a meal. Sit facing the patient at eye level. Allow enough time for the patient to chew and swallow the food. At the end of feeding for all patients both for feeders and those who can feed self, document the type and amount of food consumed. Document solids in percentages and liquid in mLs. Provide opportunities for patients to direct the order in which they want to eat the food items and how fast they wish to eat. Arrange food in the order of the clock for visually impaired patients who can feed themselves. Nutrition Support When oral feeding assistance is inadequate in providing appropriate nutrition, enteral or parental feeding is required. Enteral nutrition (EN) is the preferred method of meeting nutritional needs if a patient is unable to swallow or take in nutrients orally, yet has a functioning GI tract and are still able to digest 4 and absorb nutrients. Enteral nutrition (EN) administers nutrients directly into the stomach or intestine. Feeding tubes are inserted through the nose (nasogastric or nasointestinal), surgically (gastrostomy or jejunostomy), or endoscopically (percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy or jejunostomy [PEG or PEJ]). If EN therapy is for less than 4 weeks, nasogastric, or nasojejunal feeding tubes may be used. Surgical or endoscopically placed tubes are preferred for long-term feeding (more than 6 weeks) to reduce the discomfort of a nasal tube and provide a more secure, reliable access. Most health care settings use small-bore feeding tubes because they create less discomfort for a patient. For the adult, most of these tubes are 8- to 12-French and 36 to 44 inches (90 to 110 cm) long. Measure the distance to insert the tube by placing the tube tip at the patient’s nostril and extending it to the tip of the earlobe and then to tip of the xiphoid process. Add any extra length based on facility policy to ensure that the tube extends beyond the xiphoid process to reach the gastric body Mark the tube with an indelible marker. Measurement ensures that the tube will be long enough to enter the patient’s stomach. After selecting the appropriate nostril, ask the patient to extend the head slightly back against the pillow. Gently insert the tube into the nostril while directing the tube upward and backward along the floor of the nose. The patient may gag when the tube reaches the pharynx. When pharynx is reached, instruct the patient to touch chin to chest. Encourage the patient to sip water through a straw or swallow. Advance the tube in downward and backward direction when patient swallows. Stop when the patient breathes. If gagging and coughing persist, stop advancing the tube and check placement of the tube with a tongue blade and flashlight. If the tube is curled, straighten the tube and attempt to advance again. Keep advancing the tube until pen marking is reached. Do not use force. Rotate the tube if it meets resistance. Discontinue the procedure and remove the tube if there are signs of distress, such as gasping, coughing, cyanosis, and inability to speak or hum. Secure the tube loosely to the nose or cheek until it is determined that the 5 tube is in the patient’s stomach. Confirm placement of the NG tube in the patient’s stomach using at least two methods, based on the type of tube in place. Evidenced based best practice for verification of feeding tube placement includes radiographic confirmation of correct tube placement prior to initial use. The tube’s exit site from the nose or mouth should be marked and length documented immediately after radiographic confirmation of correct tube placement. The mark should be observed routinely and the external tube measured to assess for a change in length of the external portion of the tube. Bedside techniques to assess tube location should be used at regular intervals to determine if the tube has remained in its intended position. These bedside techniques include measuring the pH and observing the appearance of fluid withdrawn from the tube. A serious complication associated with enteral feedings is aspiration of formula into the tracheobronchial tree, which leads to infection. Improperly positioned tubes increase the risk for aspiration. Patients at low risk for gastric reflux receive gastric feedings; however, if risk of gastric reflux, which leads to aspiration, is present, jejunal feeding is preferred. Historically, nurses verified feeding tube placement by injecting air through the tube while auscultating the stomach for a gurgling or bubbling sound or asking the patient to speak. However, evidence-based research repeatedly demonstrates auscultation is ineffective in detecting tubes accidentally placed in the lung. ***Check tube placement before administering any fluids, medications, or feedings. Use multiple techniques: x-ray, external length marking/measurement, pH testing, and aspirate characteristics. Note that Radiographic (x-ray) examination of the tube after the initial insertion or when in doubt is the gold standard for checking placement. After establishing placement, introduce a small amount of fluid into the tube before feeding. Tube feeding is initiated at a low rate of infusion and is increased slowly to allow for maximum tolerance. 6 Aspiration precautions Check tube placement every 4 to 6 hours. Abdominal pain, large volume of gastric residuals, and diarrhea are signs of feeding intolerance and need to be evaluated promptly. Head of bed elevated a minimum of 30 to 40 degrees decreases the risk for aspiration. Check gastric residual volume every 4 hours. Gastric residual volume indicates whether gastric emptying is delayed. Delayed gastric emptying increases the risk for aspiration. Residual volume of more than 100-150 mLs is excessive. Remember that the 60 mLs syringe usually used is changed every 24 hrs. Regularly provided speech therapy will assist the patient in regaining the ability to swallow foods and liquids. Speech therapy includes trials of various consistencies of foods and liquids. Aspiration of food and liquids lead to chest congestion and pneumonia. Each part of the gastrointestinal (GI) system has an important digestive or absorptive function. Refer to your nutrition class for site of digestive processes, actions of enzymes and hormones with resultant end product of digestion of each of the energy giving nutrients. The longer the material stays in the large intestine, the more water is absorbed, causing the feces to become firmer. Exercise and fiber stimulate peristalsis, and water maintains consistency. Adequate water intake is 8-12 cups in a day. Absorption of carbohydrates, protein, minerals, and water-soluble vitamins occurs in the small intestine, then processed in the liver, and released into the portal vein circulation. Fatty acids are absorbed in the lymphatic circulatory systems through lacteal ducts at the center of each microvilli in the small intestine. Following absorption, metabolic processes are anabolic (building) or catabolic (breaking down). Through the chemical changes of metabolism, the body converts nutrients into a number of required substances. 7 ***Dysphagia refers to difficulty swallowing. The causes and complications of dysphagia vary. Be aware of warning signs for dysphagia. They include cough during eating; change in voice tone or quality after swallowing; abnormal movements of the mouth, tongue, or lips; and slow, weak, imprecise, or uncoordinated speech. Abnormal gag, delayed swallowing, incomplete oral clearance or pocketing, regurgitation, pharyngeal pooling, delayed or absent trigger of swallow, and inability to speak consistently are other signs of dysphagia. Educate your patients about the therapeutic diet prescribed, specifically, on how it controls their illnesses and if there are any implications. Parenteral Nutrition (PN) Parenteral nutrition (PN) is a solution consisting of glucose, amino acids, lipids, minerals, electrolytes, trace elements, and vitamins, through an indwelling peripheral (Peripheral Parenteral Nutrition (PPN) or central venous catheter (Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN). In some cases, TPN is a 2-in-1 formula in which administration of fat emulsions occurs separately from the protein and dextrose solution. Patients who have nonfunctional GI tracts, who are comatose, or who cannot consume a nutritionally adequate diet enterally may require parenteral nutrition. Safe administration depends on appropriate assessment of nutrition needs, meticulous management of the central venous catheter (CVC), and careful clinical and laboratory monitoring by a multidisciplinary team to prevent or treat metabolic complications. The goal is to move patients from PN to EN and/or oral feeding. Sometimes adding intravenous fat emulsions to PN supports the patient’s need for supplemental kilocalories, prevent essential fatty acid deficiencies, and help control hyperglycemia during periods of stress. Administer these emulsions through a separate peripheral line, through the central line by using Y-connector tubing. Insulin can be added to the PN bag due to the increased amount of glucose and the fat emulsion is the only thing that can be connected to the TPN. When using central line that has multiple lumens, use a port exclusively 8 dedicated for the TPN. Label the port for TPN and do not infuse other solutions or medications through it. A chest x-ray verifies catheter tip placement for a central line catheter before starting a PN infusion. Before beginning any PN infusion, verify the health care provider’s order and inspect the solution for particulate matter or a break in the fat emulsion. Two nurses usually confirm the order before administration. Both the bag, tubing, and syringe used for checking residual are changed every 24 hours. PN solutions contain most of the major electrolytes, vitamins, and minerals. Patients also need supplemental vitamin K as ordered throughout therapy. Synthesis of vitamin K occurs by the microflora found in the jejunum and ileum with normal use of the GI tract; however, because PN circumvents GI use, patients need to receive exogenous vitamin K. 9