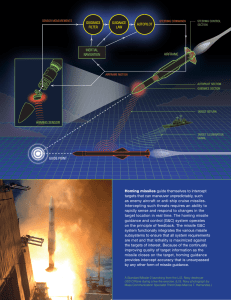

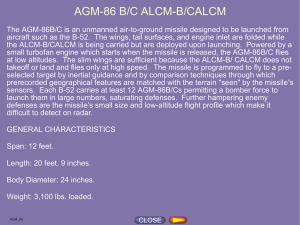

In the Name of Allah, the most Beneficent, Most Merciful Guidance and Navigation of Aerospace Vehicles Dr. Muhammad Wasim Fall 2023 Lecture 2 Guidance of Aerospace Vehicles Rocket and missile system Rocket (Unguided) Missiles (Guided) Tactical (Short Range) Strategic (Long Range) Ballistic Cruise Rocket and missile system: Rocket and missile system, any of a variety of weapons systems that deliver explosive warheads to their targets by means of rocket propulsion. Basic Principle of Rocketry: Rocket is a general term used broadly to describe a variety of jet-propelled missiles in which forward motion results from reaction to the rearward ejection of matter (usually hot gases) at high velocity. The propulsive jet of gases usually consists of the combustion products of solid or liquid propellants. Different Types of Propulsion systems in rocketry In a more restrictive sense, rocket propulsion is a unique member of the family of jetpropulsion engines that includes turbojet, ramjet, scramjet systems. Non-air breathing Engines (Rocket Propulsion): The rocket engine is different from these in that the elements of its propulsive jet (that is, the fuel and oxidizer) are self-contained within the vehicle. Therefore, the thrust produced is independent of the medium through which the vehicle travels, making the rocket engine capable of flight beyond the atmosphere or propulsion underwater. They are capable to speed up to any Mach number. Air-breathing Engines (Missile Propulsion): The turbojet, pulse-jet, and ramjet engines, on the other hand, carry only their fuel and depend on the oxygen content of the air for burning. For this reason, these varieties of jet engine are called air-breathing and are limited to operation within the Earth’s atmosphere. Non-air breathing Engines Air breathing Engines Ramjet Scramjet Guided Missiles A guided missile is broadly any military missile that is capable of being guided or directed to a target after having been launched. Tactical Missiles: Tactical guided missiles are shorter-ranged weapons designed for use in the immediate combat area. Strategic Missiles: Long-range, or strategic, guided missiles are of two types, cruise and ballistic. Strategic missiles usually carry nuclear warheads, while tactical missiles usually carry high explosives. Cruise Missiles: Cruise missiles are powered by air-breathing engines that provide almost continuous propulsion along a low, level flight path. Ballistic Missile: A ballistic missile is propelled by a rocket engine for only the first part of its flight; for the rest of the flight the unpowered missile follows an arcing trajectory, small adjustments being made by its guidance mechanism. History There is no reliable early history of the “invention” of rockets. Most historians of rocketry trace the development to China. 1232: When the Mongols laid siege to the city of K’ai-feng, capital of Honan province, the Chinese defenders used weapons that were described as “arrows of flying fire.” By 1232 the Chinese had discovered black powder (gunpowder) and had learned to use it to make explosive bombs as well as propulsive charges for rockets. 1241: In the same century rockets appeared in Europe. There is indication that their first use was by the Mongols in the Battle of Legnica in 1241. 1249: The Arabs are reported to have used rockets on the Iberian Peninsula in 1249. 1288: In 1288 Valencia was attacked by rockets. 1379: In Italy, rockets are said to have been used by the Paduans (1379) and by the Venetians (1380). History Propulsion mechanism: The propulsive charge was the basic black powder mixture of finely ground carbon (charcoal), potassium nitrate (saltpetre), and sulfur. 1668: By 1668, military rockets had increased in size and performance. In that year, a German colonel designed a rocket weighing 132 pounds (60 kilograms); it was constructed of wood and wrapped in glue-soaked sailcloth. It carried a gunpowder charge weighing 16 pounds. 1792: There Hyder Ali, prince of Mysore, developed war rockets with an important change: the use of metal cylinders to contain the combustion powder. Range was perhaps more than a kilometre. 1812: British have successfully used rockets against America and guarded Baltimore harbour World War I and after: Thrust and efficiency was greatly improved by advancement made in propulsion. They have shifted from black powder to double-base powder (40 percent nitroglycerin, 60 percent nitrocellulose). The improved rockets became the forerunners of the bazooka of World War II. 1931–32: Gasoline–oxygen-powered rockets were made by the German Rocket Society. 1931–32: The technology for a long-range ballistic missile was developed and tested in Germany. History World War II: World War II saw the expenditure of immense resources and talent for the development of rocket-propelled weapons. Rockets: 1) Barrage rockets (Germans) 2) The bazooka (US) Missile: 1) V2 (Germans) Barrage rockets: • The Germans began the war with a lead in this category of weapon, and their 150millimetre and 210-millimetre bombardment rockets were highly effective. The bazooka (US): The new rocket, about 20 inches (50 centimetres) long, 2.36 inches in diameter, and weighing 3.5 pounds, was fired from a steel tube that became popularly known as the bazooka. Designed chiefly for use against tanks and fortified positions at short ranges (up to 600 yards), the bazooka surprised the Germans when it was first used in the North African landings of 1942. V-2 missile or A-4, German ballistic missile • Developed by Germany. It was first successfully launched on October 3, 1942, and was fired against Paris on September 6, 1944. • Two days later the first of more than 1,100 V-2s was fired against Great Britain (the last on March 27, 1945). • Belgium was also heavily bombarded. About 5,000 people died in V-2 attacks, and it is estimated that at least 10,000 prisoners from the MittelbauDora concentration camp died when used as forced labour in building V-2s at the underground Mittelwerk factory. • After the war, both the United States and the Soviet Union captured large numbers of V-2s and used them in research that led to the development of their missile and space exploration programs. • The V-2 was 14 meters (47 feet) long, weighed 12,700–13,200 kg (28,000– 29,000 pounds) at launching, and developed about 60,000 pounds of thrust, burning alcohol and liquid oxygen. The payload was about 725 kg (1,600 pounds) of high explosive, horizontal range was about 320 km (200 miles), and the peak altitude usually reached was roughly 80 km (50 miles). However, on June 20, 1944, a V-2 reached an altitude of 175 km (109 miles), making it the first rocket to reach space. Guided missiles Missiles (Guided) Tactical (Short Range) Strategic (Long Range) Ballistic Cruise Tactical Missiles • Guided missiles were a product of post-World War II developments in electronics, computers, sensors, avionics, and to only a slightly lesser degree, rocket and turbojet propulsion and aerodynamics. • Although tactical, or battlefield, guided missiles were designed to perform many different roles, they were bound together as a class of weapon by similarities in sensor, guidance, and control systems. Control: Control over a missile’s direction was most commonly achieved by the deflection of aerodynamic surfaces such as tail fins; reaction jets or rockets and thrust-vectoring were also employed. But it was in their guidance systems that these missiles gained their distinction, since the ability to make down-course corrections. Ways of Guidance The earliest guided missiles used simple command guidance, but within 20 years of World War II virtually all guidance systems contained autopilots or auto stabilization systems, frequently in combination with memory circuits and sophisticated navigation sensors and computers. Five basic guidance methods came to be used, either alone or in combination: 1. command 2. Inertial 3. Active 4. semiactive 5. passive. Command Command guidance involved tracking the projectile from the launch site or platform and transmitting commands by radio, radar, or laser impulses. Tracking might be accomplished by radar or optical instruments from the launch site or by radar or television imagery relayed from the missile. The earliest command-guided air-to-surface and antitank munitions were tracked by eye and controlled by hand; later the naked eye gave way to enhanced optics and television tracking, which often operated in the infrared range and issued commands generated automatically by computerized fire-control systems. Another early command guidance method was beam riding, in which the missile sensed a radar beam pointed at the target and automatically corrected back to it. Laser beams were later used for the same purpose. Also using a form of command guidance were television-guided missiles, in which a small television camera mounted in the nose of the weapon beamed a picture of the target back to an operator who sent commands to keep the target centred in the tracking screen until impact. A form of command guidance used from the 1980s by the U.S. Patriot surface-to-air system was called track-via-missile. In this system a radar unit in the missile tracked the target and transmitted relative bearing and velocity information to the launch site, where control systems computed the optimal trajectory for intercepting the target and sent appropriate commands back to the missile. Inertial Inertial guidance was installed in long-range ballistic missiles in the 1950s, but, with advances in miniaturized circuitry, microcomputers, and inertial sensors, it became common in tactical weapons after the 1970s. Inertial systems involved the use of small, highly accurate gyroscopic platforms to continuously determine the position of the missile in space. These provided inputs to guidance computers, which used the position information in addition to inputs from accelerometers or integrating circuits to calculate velocity and direction. The guidance computer, which was programmed with the desired flight path, then generated commands to maintain the course. An advantage of inertial guidance was that it required no electronic emissions from the missile or launch platform that could be picked up by the enemy. Many antiship missiles and some long-range air-to-air missiles, therefore, used inertial guidance to reach the general vicinity of their targets and then active radar guidance for terminal homing. Passive-homing antiradiation missiles, designed to destroy radar installations, generally combined inertial guidance with memory-equipped autopilots to maintain their trajectory toward the target in case the radar stopped transmitting. Active With active guidance, the missile would track its target by means of emissions that it generated itself. Active guidance was commonly used for terminal homing. Examples were antiship, surface-to-air, and air-toair missiles that used self-contained radar systems to track their targets. Active guidance had the disadvantage of depending on emissions that could be tracked or jammed. Semiactive Semiactive guidance involved illuminating or designating the target with energy emitted from a source other than the missile; a seeker in the projectile that was sensitive to the reflected energy then homed onto the target. Like active guidance, semiactive guidance was commonly used for terminal homing. Example: In the U.S. Hawk and Soviet SA-6 Gainful antiaircraft systems. The missile homed in on radar emissions transmitted from the launch site and reflected off the target, measuring the Doppler shift in the reflected emissions to assist in computing the intercept trajectory. (SA-6 Gainful is a designation given by NATO to the Soviet missile system. The AIM-7 Sparrow air-to-air missile of the U.S. Air Force used a similar semiactive radar guidance method. With semiactive homing the designator or illuminator might be remote from the launch platform. The U.S. Hellfire antitank missile, for example, used laser designation by an air or ground observer who could be situated many miles from the launching helicopter. Passive Definition: Passive guidance systems neither emitted energy nor received commands from an external source; rather, they “locked” onto an electronic emission coming from the target itself. The earliest successful passive homing munitions were “heat-seeking” air-to-air missiles that homed onto the infrared emissions of jet engine exhausts. The first such missile to achieve wide success was the AIM-9 Sidewinder developed by the U.S. Navy in the 1950s. Many later passive homing air-to-air missiles homed onto ultraviolet radiation as well, using on-board guidance computers and accelerometers to compute optimal intercept trajectories. Among the most advanced passive homing systems were optically tracking munitions that could “see” a visual or infrared image in much the same way as the human eye does, memorize it by means of computer logic, and home onto it. Many passive homing systems required target identification and lock-on by a human operator prior to launch. With infrared antiaircraft missiles, a successful lock-on was indicated by an audible tone in the pilot’s or operator’s headset; with television or imaging infrared systems, the operator or pilot acquired the target on a screen, which relayed data from the missile’s seeker head, and then locked on manually. Passive guidance systems benefited enormously from a miniaturization of electronic components and from advances in seeker-head technology. Small, heat-seeking, shoulder-fired antiaircraft missiles first became a major factor in land warfare during the final stages of the Vietnam War, with the Soviet SA-7 Grail playing a major role in neutralizing the South Vietnamese Air Force in the final communist offensive in 1975. Ten years later the U.S. Stinger and British Blowpipe proved effective against Soviet aircraft and helicopters in Afghanistan, as did the U.S. Redeye in Central America. Tactical Missiles Antitank and antiarmor Air to surface Air to air Antiship Surface to Air (SAM) SS-10/SS-11 (French), TOW (US), UH-1, Swingfire, Milan, HOT AGM-12, AGM-45, AGM-78, AGM-88, AS-7, AS-8, AS-9 Firebird, AIM-4 Falcon, AIM-9 Sidewinder, AIM7 Sparrow, AIM-54 Phoenix, AA-1 Alkali (Soviet) Hs-293 (Germany), AS-1 Kennel (Soviet), Sea Skua (British), Harpoon (US), Tomahawk SA-1 Guild, SA-6 Gainful, SA-8 Gecko, SA7 Grail, SA-9 Gaskin, Nike Hercules Antitank and Antiarmor • One of the most important categories of guided missile to emerge after World War II was the antitank, or antiarmour, missile. A logical extension of unguided infantry antitank weapons carrying shaped-charge warheads for penetrating armour, guided antitank missiles acquired considerably more range and power than their shoulder-fired predecessors. The tactical flexibility and utility of guided antitank missiles led to their installation on light trucks, on armoured personnel carriers, and, most important, on antitank helicopters. • France S-10/S-11 MILAN & HOT (Equivalent in capability to TOW) • USA TOW equipped UH-1 Hellfire • British • Swingfire • Soviets • • • • AT-1 Snapper AT-2 Swatter AT-3 Sagger AT-6 Spiral, a Soviet version of TOW and Hellfire (became the principal antiarmour munition of Soviet attack helicopters) Guidance: • Electronic commands transmitted along extremely thin wires • later generations transmitted guidance commands by radio rather than by wire, and semiactive laser designation and passive infrared homing also became common. Wire Guided Missile HellFire Air-to-surface • The United States began to deploy tactical air-to-surface guided missiles as a standard aerial munition in the late 1950s. The first of these was the AGM-12 (for aerial guided munition) Bullpup, a rocket-powered weapon that employed visual tracking and radio-transmitted command guidance. The pilot controlled the missile by means of a small side-mounted joystick and guided it toward the target by observing a small flare in its tail. • USA AGM-45 Shrike (Passively homing onto their radar emissions, no memory circuits and required continuous emissions for homing, turning off the target radar) AGM-78 Standard ARM (incorporated memory circuits and could be tuned to any of several frequencies in flight) AGM-88 HARM (introduced into service in 1983) • Soviets • AS-7 Kerry (Radio-command-guided) • AS-8 and AS-9 • AS-10 Karen and AS-14 Kedge (television-guided, the last with a range of about 25 miles) These missiles were fired from tactical fighters such as the MiG-27 Flogger and attack helicopters such as the Mi-24 Hind and Mi-28 Havoc.AT-2 Swatter Air-to-Air • The radar-guided, subsonic Firebird was the first U.S. guided air-to-air missile. Early versions, which homed onto the infrared emissions from jet engine tailpipes, could approach only from the target’s rear quadrants. Later versions were fitted with more sophisticated seekers sensitive to a broader spectrum of radiation. These gave the missile the capability of sensing exhaust emissions from the side or front of the target aircraft. • USA AIM-4 Falcon AIM-9 Sidewinder AIM-7 Sparrow AIM-9L AIM-54 Phoenix • Soviets • AA-1 Alkali (a relatively primitive semiactive radar missile) • AA-2 Atoll (an infrared missile closely modeled after the Sidewinder) • AA-3 Anab (a long-range, semiactive radar-homing missile carried by air-defense fighters). • AA-5 Ash (was a large, medium-range radar-guided missile) • AA-6 Acrid (was similar to the Anab but larger and with greater range) • AA-7 Apex, (a Sparrow equivalent) • AA-8 Aphid (a relatively small missile for close-in use, were introduced during the 1970s) Antiship • Despite their different methods of delivery, antiship missiles formed a coherent class largely because they were designed to penetrate the heavy defenses of warships. • USA Tomahawk • Soviets • AS-3 Kangaroo, introduced in 1961 with a range exceeding 400 miles. • AS-4 Kitchen, a Mach-2 (twice the speed of sound) rocket-powered missile with a range of about 250 miles • Rocket-powered Mach-1.5 AS-5 Kelt was first deployed in 1966 • The Mach-3 AS-6 Kingfish, introduced in 1970, could travel 250 miles Surface-to-Air • The Guided surface-to-air missiles, or SAMs, were under development when World War II ended, notably by the Germans, but were not sufficiently perfected to be used in combat. This changed in the 1950s and ’60s with the rapid development of sophisticated SAM systems in the Soviet Union, the United States, Great Britain, and France. With other industrialized nations following suit, surface-to-air missiles of indigenous design, particularly in the smaller categories, were fielded by many armies and navies. • Soviets • SA-1 Guild • SA-3 Goa • SA-5 Gammon • SA-10 Grumble Strategic Missiles Ballistic Missiles • Ballistics, science of the propulsion, flight, and impact of projectiles. • Ballistic missile, a rocket-propelled self-guided strategicweapons system that follows a ballistic trajectory to deliver a payload from its launch site to a predetermined target. • Ballistic missiles can carry conventional high explosives as well as chemical, biological, or nuclear munitions. • They can be launched from aircraft, ships, and submarines in addition to mobile platforms Ballistic Missile Guidance Cruise Missile • Cruise missiles, on the other hand, are powered continuously by airbreathing jet engines and are sustained along a low, level flight path by aerodynamic lift. Missile defense system Israel Iron Dome Tactical Missile Guidance Collision Course Let Target T is moving with a constant velocity 𝑽𝑻 as it does not change direction and magnitude. Then we have a pursuer with a constant velocity 𝑽𝒑 A The line Between the Target T and Pursuer P is a Range vector From a range vector we establish a target heading angle A. Now the pursuer need a velocity to collide with target What will be the magnitude and direction of 𝑽𝒑 Let the pursuer is moving with a fixed velocity 𝑽𝒑 then there Will be lead angle between the range vector and velocity vector L P T Collision Course A L P T Collision Course A L P T Collision Course A L P T Collision Course A L P T Collision Course It requires Constant Target velocity 𝑽𝑻 Constant Pursuer Velocity 𝑽𝒑 A Lead angle and a geometric relationship At this point Differential equations are not required we can use simple geometry L P T • Because the velocities are constant so we can generate the collision triangle based on velocity vector • From the Law of Sines • Solving for target heading A 𝑻 T 𝑹 relative 𝑷 Look Angle velocity L P Look Angle: Lead Angle(when body is aligned with ,Look angle is reference to body axes) • Collision is geometric for non-maneuvering bodies with collision triangle similarity and the law of sines. • Collision for targets having greater heading or speed require the pursuer to go faster or lead more. • Greater velocity ratio require less pursuer lead for collision with a given target heading. • Greater lead and look pursuers require less velocity ratio for collision with a given target heading Qualitatively and Quantitatively Collision course in terms of Line-of-sight Direction In collision Triangle the range vector orientation does not A changes as time increases. It means that the line-of-sight direction remain Constant. L P T Qualitatively and Quantitatively Collision course in terms of Line-of-sight Direction In collision Triangle the range vector orientation does not A changes as time increases. It means that the line-of-sight direction remain Constant. Qualitatively parallel Line of sights at all instances of time L P T Qualitatively and Quantitatively Collision course in terms of Line-of-sight Direction In collision Triangle the range vector orientation does not A changes as time increases. It means that the line-of-sight direction remain Constant. Qualitatively parallel Line of sights at all instances of time Quantitatively the line-of-sight angle is constant and LOS rate is zero. (but zero with respect to what frame of reference?) L P T Qualitatively and Quantitatively Collision course in terms of Line-of-sight Direction In collision Triangle the range vector orientation does not changes as time increases. A It means that the line-of-sight direction remain T Constant. Qualitatively parallel Line of sights at all instances of time Quantitatively the line-of-sight angle is constant and LOS rate is zero. (but zero with respect to what frame of reference?) 𝜸 L Flight Path Angle Angle of the velocity vector 𝑉 with the horizon P (LOS angle) Inertial reference Qualitatively and Quantitatively Collision course in terms of Line-of-sight Direction In collision Triangle the range vector orientation does not changes as time increases. It means that the line-of-sight direction remain Constant. A T Qualitatively parallel Line of sights at all instances of time Quantitatively the line-of-sight angle is constant and LOS rate is zero. (but zero with respect to what frame of reference?) Collision is ensured when 𝝀 is constant or 𝝀̇ is zero L P (LOS angle) Inertial reference How the pursuer Knows that he is on the collision course? If the Line-of-sight rate is zero or Regulating the LOS rate is crucial in maintaining the collision course Proportional Navigation • When two bodies are not on a collision course then how we can enforce them? (Proportional Navigation is a law that enforce it). • It is implemented as a part of the Homing Loop. • It is the fundamental of advanced missile guidance. Therefore, its understanding ProNav is understanding missile guidance. T P Flight Path Angle Angle of the velocity vector 𝑉 with the horizon ProPortional navigation 2 1 ProPortional navigation 2 Altitude 1 downrange ProPortional navigation 𝑉 2 Altitude Target 1 downrange ProPortional navigation 𝑛 𝑉 2 Altitude Target 1 downrange ProPortional navigation 𝑛 𝑉 2 Altitude 𝛽 Target 1 downrange ProPortional navigation 𝑛 𝑉 𝛽 2 Target Altitude 𝑉 1 downrange ProPortional navigation 𝑛 𝑉 𝛽 2 Target Altitude 𝑉 1 downrange ProPortional navigation 𝑛 𝑉 𝛽 2 Target Altitude 𝑉 𝑛 𝑅 1 downrange From a guidance point of view, we desire to make the range between missile and target at the expected intercept time as small as possible (hopefully zero). The point of closest approach of the missile and target is known as the miss distance. ProPortional navigation 𝑛 𝑉 𝛽 2 Target Altitude 𝑉 𝑅 𝑛 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 1 downrange 𝐻𝐸 : This angle represents the initial deviation of the missile from the collision triangle. ProPortional navigation 𝑛 𝑉 𝛽 2 Target Altitude 𝑉 𝑅 𝑛 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 𝜆 1 downrange ProPortional navigation 𝑛 𝑉 𝛽 2 Target Altitude 𝑉 𝑅 𝑛 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 𝜆 1 downrange • The closing velocity is defined as the negative rate of change of the distance from the missile to the target • Therefore, at the end of the engagement, when the missile and target are in closest proximity, the sign of will change. • In the engagement model, the target can maneuver evasively with acceleration magnitude . • The angular velocity of the target: ComPonents of target veloCity 𝑛 𝑉 𝑉 2 = 𝑉 sin 𝛽 𝛽 𝑉 Altitude 𝑉 = −𝑉 cos 𝛽 Target 𝑅 𝑛 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 𝜆 1 downrange target Position ComPonents 𝑛 𝑉 𝑅̇ 2 =𝑉 = 𝑉 sin 𝛽 𝛽 𝑅̇ =𝑉 Altitude 𝑉 = −𝑉 cos 𝛽 Target 𝑅 𝑛 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 𝜆 1 downrange missile veloCity ComPonents 𝑛 𝑉 𝑅̇ 2 =𝑉 = 𝑉 sin 𝛽 𝛽 𝑅̇ =𝑉 Altitude 𝑉 = −𝑉 cos 𝛽 Target 𝑅 𝑛 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 𝑉 𝑉̇ = 𝑉 sin(𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 + 𝜆) =𝑎 𝜆 𝑉 𝑉̇ = −𝑉 cos 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 + 𝜆 =𝑎 1 downrange missile Position ComPonents 𝑛 𝑉 𝑅̇ 2 =𝑉 = 𝑉 sin 𝛽 𝛽 𝑅̇ =𝑉 Altitude 𝑉 = −𝑉 cos 𝛽 Target 𝑅 𝑛 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 𝑅̇ =𝑉 𝑉̇ = 𝑉 sin(𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 + 𝜆) =𝑎 𝜆 𝑅̇ =𝑉 𝑉̇ = −𝑉 cos 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 + 𝜆 =𝑎 1 downrange missile target seParation 𝑛 𝑉 𝑅̇ 2 =𝑉 = 𝑉 sin 𝛽 𝛽 𝑅̇ =𝑉 Altitude 𝑉 = −𝑉 cos 𝛽 Target 𝑅 𝑛 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 𝑅̇ =𝑉 𝑉̇ = 𝑉 sin(𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 + 𝜆) =𝑎 𝜆 𝑅̇ =𝑉 𝑉̇ = −𝑉 cos 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 + 𝜆 =𝑎 𝑹𝑻𝟏 1 downrange missile target seParation 𝑛 𝑉 𝑅̇ 2 =𝑉 = 𝑉 sin 𝛽 𝛽 𝑅̇ =𝑉 Altitude 𝑉 = −𝑉 cos 𝛽 Target 𝑹𝑻𝟐 𝑅 𝑛 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 𝑅̇ =𝑉 𝑉̇ = 𝑉 sin(𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 + 𝜆) =𝑎 𝜆 𝑅̇ =𝑉 𝑉̇ = −𝑉 cos 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 + 𝜆 =𝑎 𝑹𝑻𝟏 1 downrange missile target seParation 𝑛 𝑉 𝑅̇ 2 =𝑉 = 𝑉 sin 𝛽 𝛽 𝑅̇ =𝑉 Altitude 𝑉 = −𝑉 cos 𝛽 Target 𝑹𝑻𝟐 𝑅 𝑛 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 𝑅̇ =𝑉 𝑉̇ = 𝑉 sin(𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 + 𝜆) =𝑎 𝜆 𝑅̇ =𝑉 𝑉̇ = −𝑉 cos 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 + 𝜆 =𝑎 𝑹𝑴𝟏 𝑹𝑻𝟏 1 downrange missile target seParation 𝑛 𝑉 𝑅̇ 2 =𝑉 = 𝑉 sin 𝛽 𝛽 𝑅̇ =𝑉 Altitude 𝑉 = −𝑉 cos 𝛽 Target 𝑹𝑻𝟐 𝑅 𝑛 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 𝑅̇ =𝑉 𝑉̇ = 𝑉 sin(𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 + 𝜆) =𝑎 𝜆 𝑅̇ =𝑉 𝑉̇ = −𝑉 cos 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 + 𝜆 =𝑎 𝑹𝑴𝟏 𝑹𝑻𝟏 𝑹𝑴𝟐 1 downrange missile target seParation 𝑛 𝑉 𝑅̇ 2 =𝑉 = 𝑉 sin 𝛽 𝛽 𝑅̇ =𝑉 Altitude = −𝑉 cos 𝛽 Target 𝑹𝑻𝑴𝟐 = (𝑹𝑻𝟐 − 𝑹𝑴𝟐 ) 𝑉 𝑅 𝑛 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 𝑅̇ =𝑉 𝑉̇ = 𝑉 sin(𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 + 𝜆) =𝑎 𝜆 𝑅̇ =𝑉 𝑉̇ = −𝑉 cos 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 + 𝜆 =𝑎 𝑹𝑴𝟏 𝑹𝑻𝟏 𝑹𝑴𝟐 1 downrange 𝑹𝑻𝟐 missile target seParation 𝑛 𝑉 𝑅̇ 2 =𝑉 = 𝑉 sin 𝛽 𝛽 𝑅̇ =𝑉 Altitude = −𝑉 cos 𝛽 Target 𝑹𝑻𝑴𝟐 = (𝑹𝑻𝟐 − 𝑹𝑴𝟐 ) 𝑉 𝑅 𝑛 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 𝑅̇ =𝑉 𝑉̇ = 𝑉 sin(𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 + 𝜆) =𝑎 𝑅̇ 𝜆 𝑹𝑻𝑴𝟏 = (𝑹𝑻𝟏 − 𝑹𝑴𝟏 ) =𝑉 𝑉̇ = −𝑉 cos 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 + 𝜆 =𝑎 𝑹𝑴𝟏 𝑹𝑻𝟏 𝑹𝑴𝟐 1 downrange 𝑹𝑻𝟐 CalCulation of line-of-sight angle 𝑛 𝑉 𝑅̇ 2 =𝑉 = 𝑉 sin 𝛽 𝛽 𝑅̇ =𝑉 Altitude = −𝑉 cos 𝛽 𝑅 𝑉 Target 𝑹𝑻𝑴𝟐 = (𝑹𝑻𝟐 − 𝑹𝑴𝟐 ) 𝑛 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 𝑅̇ =𝑉 𝑉̇ = 𝑉 sin(𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 + 𝜆) =𝑎 𝑅̇ 𝜆 𝑹𝑻𝑴𝟏 = (𝑹𝑻𝟏 − 𝑹𝑴𝟏 ) =𝑉 𝑉̇ = −𝑉 cos 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 + 𝜆 =𝑎 𝑹𝑴𝟏 𝑹𝑻𝟏 𝑹𝑴𝟐 1 downrange 𝑹𝑻𝟐 • Relative Velocity Components • Line-of-sight angle 𝑑 𝑑 𝑑𝑥 tan 𝑥 = tan 𝑥 𝑑𝑡 𝑑𝑥 𝑑𝑡 𝑑 𝑑 tan 𝑥 = tan 𝑥 𝑥̇ 𝑑𝑡 𝑑𝑥 • Closing Velocity • Missile guidance law • Missile acceleration components in earth coordinates 𝑅 = 𝑅 +𝑅 • line-of-sight angle calculations Using law of sines Summary • • • • • • • • ( • ( ) ) TWO-DIMENSIONAL ENGAGEMENT SIMULATION • Initializing Parameters (0,10000) n=0; VM = 3000.; VT = 1000.; XNT = 0.; HEDEG = -20.; XNP = 5.; RM1 = 0.; RM2 = 10000.; RT1 = 40000.; RT2 = 10000.; BETA=0.; 2 Altitude 𝐻𝐸 = −20 (40000,10000) 𝑉 = 1000 𝛽=0 Target 1 downrange TWO-DIMENSIONAL ENGAGEMENT SIMULATION • Using formulas VT1=-VT*cos(BETA); VT2=VT*sin(BETA); HE=HEDEG/57.3; T=0.; S=0.; RTM1=RT1-RM1; RTM2=RT2-RM2; RTM=sqrt(RTM1*RTM1+RTM2*RTM2); XLAM=atan2(RTM2,RTM1); XLEAD=asin(VT*sin(BETA+XLAM)/VM); THET=XLAM+XLEAD; VM1=-VM*cos(THET+HE); VM2=VM*sin(THET+HE); VTM1 = VT1 - VM1; VTM2 = VT2 - VM2; VC=-(RTM1*VTM1 + RTM2*VTM2)/RTM; % Calculation of Line-of-sight angle % Calculation of lead angle % summation of Lead and line-of-sight angle % % Calculation of closing velocity TWO-DIMENSIONAL ENGAGEMENT SIMULATION while VC >= 0 if RTM <1000 H=.0002; else H=.01; end STEP=1; FLAG=0; while STEP <=1 if FLAG==1 STEP=2; BETA=BETA+H*BETAD; RT1=RT1+H*VT1; RT2=RT2+H*VT2; RM1=RM1+H*VM1; RM2=RM2+H*VM2; VM1=VM1+H*AM1; VM2=VM2+H*AM2; T=T+H; end RTM1=RT1-RM1; RTM2=RT2-RM2; RTM=sqrt(RTM1*RTM1+RTM2*RTM2); VTM1=VT1-VM1; VTM2=VT2-VM2; VC=-(RTM1*VTM1+RTM2*VTM2)/RTM; XLAM=atan2(RTM2,RTM1); XLAMD=(RTM1*VTM2RTM2*VTM1)/(RTM*RTM); XNC=XNP*VC*XLAMD; AM1=-XNC*sin(XLAM); AM2=XNC*cos(XLAM); VT1=-VT*cos(BETA); VT2=VT*sin(BETA); BETAD=XNT/VT; FLAG=1; end FLAG=0; S=S+H; if S >=.09999 S=0.; n=n+1; ArrayTN5(n)=T; ArrayRT1N5(n)=RT1; ArrayRT2N5(n)=RT2; ArrayRM1N5(n)=RM1; ArrayRM2N5(n)=RM2; ArrayXNCGN5(n)=XNC/32.2; ArrayRTMN5(n)=RTM; end end Proportional Navigation Acceleration Profile Maneuvering Target Maneuvering Target acceleration profile Linearization 2 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 𝜆 𝛽 Target 1 downrange CalCulation of line-of-sight angle 𝑛 𝑉 (180 − 90 − 𝛽) Target 𝛽 2 Altitude 𝑅 𝑉 𝒀 𝒀𝑻 𝑛 𝑛 𝑠𝑖𝑛(180 − 90 − λ) 𝑛 𝑠𝑖𝑛 90 − 𝜆 𝑛 𝑐𝑜𝑠 𝜆 𝐿 + 𝐻𝐸 𝜆 𝒀𝑴 (180 − 90 − 𝜆) 1 downrange 𝑛 𝑠𝑖𝑛(180 − 90 − 𝛽) 𝑛 𝑠𝑖𝑛 90 − 𝛽 𝑛 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝛽 • Relative Acceleration For small angles 𝑦̈ = 𝑛 cos 𝛽 − 𝑛 cos(𝜆) 𝑦̈ = 𝑛 − 𝑛 The expression of Line of sight angle can be linearized 𝑦 𝜆= 𝑅 For head on collision the closing velocity can be approximated as 𝑉 =𝑉 +𝑉 For Tail chase 𝑉 =𝑉 −𝑉 Range 𝑅 =𝑉 𝑡 −𝑡 Miss distance 𝑀𝑖𝑠𝑠 = 𝑦(𝑡 ) TWO-DIMENSIONAL ENGAGEMENT SIMULATION Linearized • Initializing Parameters (0,10000) • XNT=0.; • Y=0.; • VM=3000.; 2 Altitude 𝐻𝐸 = −20 (40000,10000) 𝑉 = 1000 𝛽=0 Target • VT=1000.; • HEDEG=-20.; • TF=10.; • XNP=4.; • YD=-VM*HEDEG/57.3; • T=0.; • H=.01; • S=0.; • n=0.; • VC=VM-VT; 1 downrange TWO-DIMENSIONAL ENGAGEMENT SIMULATION Linearized while T<=(TF-1e-5) % YOLD=Y; % YDOLD=YD; STEP=1; FLAG=0; while STEP<=1 if FLAG==1 STEP=2; Y=Y+H*YD; YD=YD+H*YDD; T=T+H; end TGO=TF-T+.00001; XLAMD=(Y+YD*TGO)/(VC*TGO); XNC=XNP*VC*XLAMD; YDD=XNT-XNC; FLAG=1; end FLAG=0; % Y=.5*(YOLD+Y+H*YD); % YD=.5*(YDOLD+YD+H*YDD); S=S+H; if S>=.0999 S=0.; n=n+1; ArrayTL(n)=T; ArrayY(n)=Y; ArrayYD(n)=YD; ArrayXNCG(n)=XNC/32.2; end . Acceleration Profile Maneuvering Target acceleration profile Homing Loop Airframe design Atmospheric model Autopilot Actuator Dynamics Dynamic model of missile Aerodynamic model Aerodynamic coefficients Guidance Seeker/Tracker Line of sight angle calculation Simulation results Results Assignment (Deadline: 15-11-2024) • Derive the equations for zero effort miss distance. • Design the augmented and optimal guidance law and implement it for engagement simulation. (CLO-02) • Book Textbook 1 chapter 8 (page 163- Page 185)