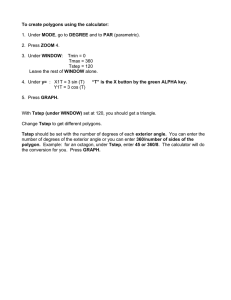

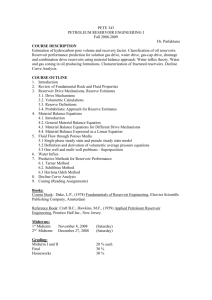

Louisiana State University LSU Scholarly Repository LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Mechanisms and control of water inflow to wells in gas reservoirs with bottom water drive Miguel Armenta Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Petroleum Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Armenta, Miguel, "Mechanisms and control of water inflow to wells in gas reservoirs with bottom water drive" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 232. https://repository.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/232 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Scholarly Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Scholarly Repository. For more information, please contactgradetd@lsu.edu. MECHANISMS AND CONTROL OF WATER INFLOW TO WELLS IN GAS RESERVOIRS WITH BOTTOM-WATER DRIVE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in Partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Craft & Hawkins Department of Petroleum Engineering by Miguel Armenta B.S. Petroleum Engineering, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Colombia, 1985 M. Environmental Development, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Colombia, 1996 December 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To God, my best and inseparable friend, for you are the glory, honor and recognition. To my wife, Chechy, and my children Andrea and Miguel, for giving me so much love and support. Without you, getting this important step in my life, my PhD, has no meaning. You are my inspiration and my strength. To my parents, El Viejo Migue and La Niña Dorita, you are my source of beliefs. You taught and gave me the determination and tools to reach my dreams with honesty and hard work. To my advisor, Dr. Andrew Wojtanowicz, for his guidance and challenging comments. Without that motivation, this research would have been poor; however, facing the challenges four different technical papers have been already published and presented from this research. To Dr. Christopher White for helping me with such honesty and unselfishness. You were my lifesaver at my hardest time during my research. I knew I could always count on you. To Dr. Zaki Bassiouni, chairman of the Craft & Hawking Petroleum Engineering Department, for giving me the right comments and advise at the right time. To the rest of Craft & Hawking Petroleum Engineering Department faculty members, Dr. John Smith, Dr. Julius Langlinais, Dr. Dandina Rao, and Dr. John McMullan, from each one of you I learned many important things not only for my professional life, but also for my personal life. I will always have you in my mind and heart. ii To my friends in Baton Rouge: Patricio & Maquica, Jose & Ericka, Juan & Joanne, Fernando & Sabina, Jaime & Luz Edith, Alvaro & Tonya, Doña Luz & Dr. Narses, Jorge & Ana Maria, Nicolas & Solange, and La Pili. All of you are angels sent by God to help me during my crisis-time; you, however, did not know your mission. God bless you. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS….…………………………………………………………ii LIST OF TABLES……………………………………………………………………..vii LIST OF FIGURES..…………………………………………………………………..viii NOMENCLATURE.…………….…………………………………………………….xiv ABSTRACT…………………….……………………………………………………..xvii CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………1 1.1 Background and Purpose……………………...…………………………………..1 1.2 Statement of Research Problem………………...…..……………………………..4 1.3 Significance and Contribution of this Research.…………………………………..5 1.4 Research Method and Approach……………....…………………………………..6 1.5 Work Program Logic………………………….…………………………………..8 CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW……………………………………………...11 2.1 Critical Velocity………………………………………………………………….11 2.2 Critical Rate for Water Coning………………………………….……………….13 2.3 Techniques Used in Solving Water Loading ……………………………………16 2.3.1 Tubing Lift Improvement..………………………………………………16 2.3.1.1. Chemical Injection….…………………………………………16 2.3.1.2. Physical Modification…..……………………………………..18 2.3.1.3. Thermal…………..……………………………………………19 2.3.1.4. Mechanical. ….…..……………………………………………20 2.3.2 Bottom Liquid Removal...………………………………………………21 2.3.2.1. Pumps………….………………………………………………22 2.3.2.2. Swabbing………………………………………………………23 2.3.2.3. Plungers…………………………………..……………………24 2.3.2.4. Downhole Gas Water Separation……………………….……..27 CHAPTER 3 MECHANISTIC COMPARISON OF WATER CONING IN OIL AND GAS WELLS…………..…………………………………………30 3.1 Vertical Equilibrium.………………………………...…………………………..30 3.2 Analytical Comparison of Water Coning in Oil and Gas Wells before Water Breakthrough ………………………………………...…………………………..31 3.3 Analytical Comparison of Water Coning in Oil and Gas Wells after Water Breakthrough ………………………………………...…………………………..32 3.4 Numerical Simulation Comparison of Water Coning in Oil and Gas Wells after Water Breakthrough …………….…………………...…………………………..37 3.5 Discussion about Water Coning in Oil-Water and Gas-Water Systems..………..41 CHAPTER 4 EFFECTS INCREASING BOTTOM WATER INFLOW TO GAS WELLS………....…………...…………………………………..………43 4.1 Effect of Vertical Permeability…………………...…………….………………..44 iv 4.2 Aquifer Size Effects..………………..…..………...………..…….……………..47 4.3 Non-Darcy Flow Effect..…………………………………………….…………..49 4.3.1 Analytical Model………………..…….………………….….…………..50 4.3.2 Numerical Model………………..…….………………….….…………..55 4.4 Effect of Perforation Density……………………..……...……………….……...57 4.5 Effect of Flow behind Casing …………………….……...……………….……..58 4.5.1 Cement Leak Model….…………..…….………………….……………..59 4.5.1.1 Effect of Leak Size and Length………………………………….64 4.5.1.2 Diagnosis of Gas Well with Leaking Cement…………..……….67 CHAPTER 5 EFFECT OF NON-DARCY FLOW ON WELL PRODUCTIVITY IN TIGHT GAS RESERVOIRS…….………………………..………69 5.1 Non-Darcy Flow Effect in Low-Rate Gas Wells……………….………………..70 5.2 Field Data Analysis…………………………….……………….………………..73 5.3 Numerical Simulator Model…..……………….……………….………………..76 5.3.1 Volumetric Gas Reservoir………..…….………………….……………..78 5.3.2 Water Drive Gas Reservoir………..…….………………….………..…..80 5.4 Results and Discussion………..……………….……………….………………..85 CHAPTER 6 WELL COMPLETION LENGTH OPTIMIZATION IN GAS RESERVOIRS WITH BOTTOM WATER ………..………..……….87 6.1 Problem Statement……………………….………………….….………………..87 6.2 Study Approach…..…….…………..……………………….….………………..88 6.2.1 Reservoir Simulation Model……………………………………………..88 6.2.1.1 Factors Considered…………………………………………………..89 6.2.1.2 Responses Considered…………………………………………….…90 6.2.2 Statistical Methods…………………………………………………….…91 6.2.2.1 Experimental Design…………………………………………………91 6.2.2.2 Statistical Analyses…………………………………………………..91 6.2.2.3 Linear Regression Models…………………………………………...92 6.2.2.4 Analysis of Variance…………………………………………………93 6.2.2.5 Monte Carlo Simulation……………………………………………..93 6.2.3 Optimization……………………………………………………………..94 6.2.4 Workflow………………………………………………………………...94 6.3 Results and Discussion…………………………………………………………..96 6.3.1 Linear Models……………………………………………………………96 6.3.2 Sensitivities (ANOVA)…………………………………………………..98 6.3.3 Monte Carlo Simulation………………………………………………...103 6.3.4 Optimization……………………………………………………………107 6.4 Implications For Water-Drive Gas Wells………………………………………108 CHAPTER 7 DOWNHOLE WATER SINK WELL COMPLETIONS IN GAS RESERVOIR WITH BOTTOM WATER….………………...……..110 7.1 Alternative Design of DWS for Gas Wells…………………….……………….110 7.1.1 Dual Completion without Packer..…….………………….…………….111 7.1.2 Dual Completion with Packer…...…….………………….…………….112 7.1.3 Dual Completion with a Packer and Gravity Gas-Water Separation………………………..…….………………….……………113 v 7.2 Comparison of Conventional Wells and DWS Wells.………….………………115 7.2.1 Reservoir Simulator Model……...…….………………….…………….115 7.2.2 Reservoir Parameters Selection…..…….………………….…………...117 7.2.3 Conventional Wells Completion Length…...…………….…………….118 7.2.4 Gas Recovery and Production Time Comparison..……….…………….122 7.2.5 Reservoir Candidates for DWS Application……..……….…………….124 7.3 Comparison of DWS and DGWS………………………..…….……………….126 7.3.1 DWS and DGWS Simulation Model….………………….…………….126 7.3.2 DWS vs. DGWS Comparison Results ..………………….…………….127 7.3.3 Discussion About the Packer for DWS Wells...………….…………….131 CHAPTER 8 DESIGN AND PRODUCTION OF DWS GAS WELLS.…..……...133 8.1 Effect of Top Completion Length………………………….….………………..134 8.2 Effect of Water-Drainage Rate from the Bottom Completion……..….………..137 8.3 Effect of Separation between the Two Completions.……….….………………139 8.4 Effect of Bottom Completion Length………………………….….…………....141 8.5 DWS Operational Conditions for Gas Wells…………….….………………….143 8.5.1 Effect of Bottom Hole Flowing Pressure at the Bottom Completion….………….………………………………….…………...149 8.6 When to Install DWS in Gas Wells…………….….……………..…………….153 8.7 Recommended DWS Operational Conditions in Gas Wells……….….……….156 CHAPTER 9 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS….………...……..158 9.1 Conclusions………………………..……………………….….………………..158 9.2 Recommendations..………………..……………………….….………………..161 REFERENCES……………………….………………………………………………..163 APPENDIX-A ANALYTICAL COMPARISON OF WATER CONING IN OIL AND GAS WELLS……….…………..……………………………..175 APPENDIX-B EXAMPLE ECLIPSE DATA DECK FOR COMPARISON OF WATER CONING IN OIL AND GAS WELLS AFTER WATER BREAKTHROUGH ………………………………………………..181 APPENDIX-C EXAMPLE ECLIPSE DATA DECK FOR EFFECT OF VERTICAL PERMEABILITY ON WATER CONING..………..190 APPENDIX-D ANALYTICAL MODEL FOR NON-DARCY EFFECT IN LOW PRODUCTIVITY GAS RESERVOIRS……………….....………..213 APPENDIX-E EXAMPLE IMEX DATA DECK FOR NON-DARCY FLOW IN LOW PRODUCTIVITY GAS RESERVOIRS..…..……..………..215 APPENDIX-F EXAMPLE ECLIPSE DATA DECK FOR COMPARISON OF CONVENTIONAL WELLS AND DWS WELLS..……..………...227 VITA…………………………………………………………….……..……..………..245 vi LIST OF TABLES Table 3.1 Gas, Water, and Oil Properties Used for the Numerical Simulator Model…...38 Table 5.1 Data Used for the Analytical Model…………………………………………..71 Table 5.2 Rock Properties and Flow Rates Data for Wells A-6, A-7, and A-8 from Brar & Aziz (1978)…………….……………………………………………………74 Table 5.3 Flow Rate and Values of a and b for Gas Wells with Multi-flow Tests….…...75 Table 5.4 Gas and Water Properties Used for the Numerical Simulator Model…………77 Table 6.1 Factor Descriptions……………………………………………………………89 Table 6.2 Factor Descriptions Including Box-Tidwell Power Coefficients……………..97 Table 6.3 Linear Sensitivity Estimates For Models Without Factors Interactions….…..99 Table 6.4 Transformed, Scaled Model for the Box-Cox Transform of Net Present Value………………………………………………………………….…….100 Table 6.5 Parameters for Beta Distributions of Factors………………………….……..104 Table 6.6 Monte Carlo Sensitivity Estimates…………………………………………..105 Table 8.1 Operation Conditions for Top Completion Length Evaluation….…………..136 Table 8.2 Operation Conditions for Water-Drained Rate Evaluation……….………….137 Table 8.3 Operation Conditions for Evaluation of Separation Between The Completions………………………………………………………….……..139 Table 8.4 Operation Conditions for Different Bottom Completion Length……….…...142 Table 8.5 Operation Conditions for Different Top Completion Length, Bottom Completion Length, and Water-Drained Rate…….……..…….…………...145 Table 8.6 Operation Conditions for Evaluation of Different Constant Bottomhole Flowing Pressure at The Bottom Completion………………………………149 Table 8.7 Operation Conditions for “When” to Install DWS in Low Productivity Gas Well…………..………………………………………….………………….153 vii LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1.1 Gas Rate and Water Rate History for an Actual Gas Well……………………2 Figure 1.2 Gas Recovery Factor and Water Rate History for an Actual Gas Well……….2 Figure 3.1 Theoretical Model Used to Compare Analytically Water Coning in Oil and Gas Wells before Breakthrough..………..…………………………………...31 Figure 3.2 Theoretical Model Used to Compare Analytically Water Coning in Oil and Gas Wells after Breakthrough….....…….……………………………….…...33 Figure 3.3 Shape of the Gas-Water and Oil-Water Contact for Total Perforation.……...36 Figure 3.4 Numerical Model Used for Comparison of Water Coning in Oil-Water and Gas-Water Systems……..…………………………………………….……...37 Figure 3.5 Numerical Comparison of Water Coning in Oil-Water and Gas-Water Systems after 395 Days of Production………….…………………….……...39 Figure 3.6 Zoom View around the Wellbore to Watch Cone Shape for the Numerical Model after 395 Days of Production….………..…………………….….…...40 Figure 4.1 Numerical Reservoir Model Used to Investigate Mechanisms Improving Water Coning/Production (Vertical Permeability and Aquifer Size)….….....44 Figure 4.2 Distribution of Water Saturation after 395 days of Gas Production…….…...45 Figure 4.3 Water Rate versus Time for Different Values of Permeability Anisotropy....46 Figure 4.4 Distribution of Water Saturation after 1124.8 days of Gas Production……..48 Figure 4.5 Water Rate versus Time for Different Values of Aquifer Size……………...49 Figure 4.6 Analytical Model Used to Investigate the Effect of Non-Darcy in Water Production…..………..……………………………………………………...50 Figure 4.7 Skin Components at the Well for a Single Perforation for the Analytical Model Used to Investigate Non-Darcy Flow Effect in Water Production…...52 Figure 4.8 Water-Gas Ratio versus Gas Recovery Factor for Total Penetration of Gas Column without Skin and Non-Darcy Effect………..………..….……….…53 Figure 4.9 Water-Gas Ratio versus Gas Recovery Factor for Total Penetration of Gas Column Including Mechanical Skin Only…………..…………..…………...53 viii Figure 4.10 Water-Gas Ratio versus Gas Recovery Factor for Total Penetration of Gas and Water Columns, Skin and Non-Darcy Effect Included……...…..……...54 Figure 4.11 Water-Gas Ratio versus Gas Recovery Factor for Wells Completed Only through Total Perforation the Gas Column with Combined Effects of Skin and Non-Darcy……..……………………..……..…………..……….……...55 Figure 4.12 Gas Rate versus Time for the Numerical Model Used to Evaluate the Effect of Non-Darcy Flow in Water Production……..……………………………...56 Figure 4.13 Water Rate versus Time for the Numerical Model Used to Evaluate the Effect of Non-Darcy Flow in Water Production……..……………………....57 Figure 4.14 Effect of Perforation Density on Water-Gas Ratio for a Well Perforating in the Gas Column, Skin and Non-Darcy Effect Included..…………….……....58 Figure 4.15 Cement Channeling as a Mechanism Enhancing Water Production in Gas Wells………..……………………………..………………………………....59 Figure 4.16 Modeling Cement Leak in Numerical Simulator ……..…………………....60 Figure 4.17 Relationship between Channel Diameter and Equivalent Permeability in the First Grid for the Leaking Cement Model……..………………………….....62 Figure 4.18 Values of Radial and Vertical Permeability in the Simulator’s First Grid to Represent a Channel in the Cemented Annulus.……..…………….….….....63 Figure 4.19 Effect of Leak Length: Behavior of Water Production Rate with and without a Channel in the Cemented Annulus.….……………………..….....64 Figure 4.20 Effect of Channel Size: Behavior of Water Production Rate for a Channel in the Cemented Annulus above the Initial Gas-Water Contact.……..…......65 Figure 4.21 Effect of Channel Size: Behavior of Water Production Rate for a Channel in the Cemented Annulus throughout the Gas Zone Ending in the Water Zone…………………………………………………………………………66 Figure 5.1 Fraction of Pressure Drop Generated by N-D Flow for a Gas Well Flowing from a Reservoir with Permeability 100 md.….…..………………….…..…71 Figure 5.2 Fraction of Pressure Drop Generated by N-D Flow for a Gas Well Flowing from a Reservoir with Permeability 10 md.…….………….………….…..…72 Figure 5.3 Fraction of Pressure Drop Generated by N-D Flow for a Gas Well Flowing from a Reservoir with Permeability 1 md.……....…………………….…..…73 ix Figure 5.4 Fraction of Pressure Drop Generated by N-D Flow for Wells A-6, A-7, and A-8; from Brar & Aziz (1978)….…………………………………….…..….74 Figure 5.5 Fraction of Pressure Drop Generated by N-D Flow for Gas Wells–Field Data..…………………………………………………………………………76 Figure 5.6 Sketch Illustrating the Simulator Model Used to Investigate N-D Flow….…77 Figure 5.7 Gas Rate Performance with and without N-D Flow for a Volumetric Gas Reservoir ………..………………………………………………………...…78 Figure 5.8 Cumulative Gas Recovery Performance with and without N-D Flow for a Volumetric Gas Reservoir..………..…………………………………….…..79 Figure 5.9 Fraction of Pressure Drop Generated by Non-Darcy Flow for Gas Wells – Simulator Model………..….………………………….………………...…...79 Figure 5.10 Gas Rate Performances with N-D (Distributed in the Reservoir and Assigned to the Wellbore) and without N-D Flow for a Gas Water-Drive Reservoir…………………………………………………………………..…80 Figure 5.11 Gas Recovery Performances with N-D (Distributed in the Reservoir and Assigned to the Wellbore) and without N-D Flow for a Gas Water-Drive Reservoir.…………………………………………………………………….81 Figure 5.12 Water Rate Performances With N-D (Distributed in the Reservoir and Assigned to the Wellbore) and without N-D Flow for a Gas Water-Drive Reservoir……………………………………………………………..………82 Figure 5.13 Flowing bottom hole pressure performances with N-D (distributed in the reservoir and assigned to the wellbore) and without N-D flow……………...82 Figure 5.14 Pressure performances in the first simulator grid (before completion) with ND (distributed in the reservoir and assigned to the wellbore) and without N-D flow.…..…………………………..….………………………………...83 Figure 5.15 Pressure distribution on the radial direction at the lower completion layer after 126 days of production (Wells produced at constant gas rate of 8.0 MMSCFD) with ND (distributed in the reservoir and assigned to the wellbore) and without N-D flow…………………………………………….84 Figure 6.1 Flow diagram for the workflow used for the study…………………….….…95 Figure 6.2 Effect of Permeability and Initial Reservoir Pressure on Net Present Value……………………………………………..……………………..…..101 Figure 6.3 Effect of Permeability and Completion Length on Net Present Value……..102 x Figure 6.4 Effect of Gas Price and Completion Length on Net Present Value……….102 Figure 6.5 Effect of Discount Rate and Gas Price on Net Present Value……………..103 Figure 6.6 Beta Distribution Used for Monte Carlo Simulation………………………104 Figure 6.7 Monte Carlo Simulation of the Net Present Value…………………………105 Figure 6.8 Optimization of Net Present Value Considering Uncertainty in Reservoir and Economic Factors (two cases) ……………………….………….…….106 Figure 6.9 Optimal Completion Length Calculated from the Transformed Model and a Response Model Computed from Local Optimization……..…………….108 Figure 6.10 Relative Loss of Net Present Values If Completion Length Is Not Optimized…………………………………………………………………...109 Figure 7.1 Dual Completion without Packer….………………………………………..111 Figure 7.2 Dual Completion with Packer…..…………………………………………..113 Figure 7.3 Dual Completion with a Packer and Gravity Gas-Water Separation...……..114 Figure 7.4 Simulation Model of Gas Reservoir for DWS Evaluation…….……………116 Figure 7.5 Gas Recovery for Different Completion Length in Gas Reservoirs with Subnormal Initial Pressure…………………………..……….……..………119 Figure 7.6 Gas Recovery for Different Completion Length in Gas Reservoirs with Normal Initial Pressure…..……………………….…..……………..……...119 Figure 7.7 Gas Recovery for Different Completion Length in Gas Reservoirs with Abnormal Initial Pressure…….………………..……..……………..……...120 Figure 7.8 Flowing Bottom Hole Pressure versus Time (Normal Initial Pressure; 50% Penetration)……………………….…………………..……………..……..120 Figure 7.9 Gas Rate versus Time (Normal Initial Pressure; 50% Penetration)………...121 Figure 7.10 Gas Recovery and Total Production Time for Conventional and DWS Wells for Different Initial Reservoir Pressure and Permeability 1 md……..122 Figure 7.11 Gas Recovery and Total Production Time for Conventional and DWS Wells for Different Initial Reservoir Pressure and Permeability 10 md…....123 Figure 7.12 Gas Recovery and Total Production Time for Conventional and DWS Wells for Different Initial Reservoir Pressure and Permeability 100 md…..124 xi Figure 7.13 Gas Rate History for Conventional and DWS Wells (Subnormal Reservoir Pressure and Permeability 1 md)…….……..………….…………………...125 Figure 7.14 Flowing Bottom Hole Pressure History for Conventional and DWS Wells (Subnormal Reservoir Pressure and Permeability 1 md)…..….……………125 Figure 7.15 Gas Recovery and Production Time Ratio (PTR) for Conventional, DWS, and DGWS Wells……….………………………………….……………….128 Figure 7.16 Gas Recovery versus Time for DWS, DGWS, and Conventional Wells….129 Figure 7.17 Gas Rate History for DWS-2, DGWS-1, and Conventional Wells…..……130 Figure 7.18 Water Rate History for DWS-2, DGWS-1, and Conventional Wells…..…130 Figure 7.19 Bottom hole flowing pressure history for DWS-2, DGWS-1, and conventional wells.…………………………………………………….…131 Figure 8.1 Factors Used to Evaluate DWS Performance ………...….…………..…….133 Figure 8.2 Gas Recovery Factor for Different Length ff The Top Completion..………134 Figure 8.3 Total Production Time for Different Length of The Top Completion. …….135 Figure 8.4 Gas Recovery Factor for Different Water-Drained Rate.……..……………138 Figure 8.5 Total Production Time for Different Water-Drained Rate………..………...138 Figure 8.6 Gas Recovery Factor for Different Separation Distance Between The Completions. ……………………………………………………………….140 Figure 8.7 Total Production Time for Different Separation Distance Between The Completions …………….………………………………………………….141 Figure 8.8 Gas Recovery Factor for Evaluation of Different Length at The Bottom Completion.………..….…………………………………………………….142 Figure 8.9 Total Production Time for Evaluation of Different Length at The Bottom Completion …………………………………………………………………143 Figure 8.10 Gas Recovery for Different Lengths of Top, and Bottom Completions and Maximum Water Drained. The Two Completions Are Together. Reservoir Permeability Is 1 md.……………………………………………………….146 Figure 8.11 Total Production Time for Different Lengths of Top and Bottom Completions and Maximum Water Drained. The Two Completions Are Together. Reservoir Permeability Is 1 md …………………………………146 xii Figure 8.12 Gas Recovery for Different Lengths of Top, and Bottom Completions and Maximum Water Drained. The Two Completions Are Together. Reservoir Permeability Is 10 md ……………………………………………………...147 Figure 8.13 Total Production Time for Different Lengths of Both Completions and Maximum Water Drained. The Two Completions Are Together. Reservoir Permeability Is 10 md …………….………………………………………..148 Figure 8.14 Gas Recovery for Different Constant BHP at The Bottom Completion.….150 Figure 8.15 Total Production Time for Evaluation of Different Constant BHP at The Bottom Completion …………………………….…………………………..150 Figure 8.16 Flowing Bottomhole Pressure History at The Top, and Bottom Completion for Two Different Constant BHP at The Bottom Completion (100 psia, and 200 psia). Permeability Is 1 md ………………………….………………...151 Figure 8.17 Average Reservoir for Two Different Constant BHP at The Bottom Completion (100 psia, and 200 psia). Permeability Is 1 md …….…………152 Figure 8.18 Gas Recovery for Different Times of Installing DWS.…….……………...154 Figure 8.19 Total Production Time for Different Times of Installing DWS.…………..154 Figure 8.20 Cumulative Gas Recovery for Different Times of Installing DWS. Reservoir Permeability Is 10 md.…….……………………..…………...156 xiii NOMENCLATURE a = Darcy flow coefficient, (psia2-cp)/(MMscf-D) for calculation in terms of pseudopressure or psia2/(MMscf-D) for calculations in terms of pressure squared A = drainage area of well, ft2 b = Non-Darcy flow coefficient, (psia2-cp)/(MMscf-D)2 for calculation in terms of pseudopressure or psia2/(MMscf-D)2 for calculations in terms of pressure squared Bw = water formation volume factor, reservoir barrels per surface barrels CA = factor of well drainage area D = Non-Darcy flow coefficient, day/Mscf dp = pressure derivative, psia dL = length derivative, ft F = fraction of pressure drop generated by Non-Darcy flow effect, dimensionless h = net formation thickness, ft hg = thickness of gas, ft hpre = perforated interval, ft hw = thickness of water, ft k = permeability, millidarcies kd = altered reservoir permeability, millidarcies kdp = crashed zone permeability, millidarcies xiv kH = horizontal permeability, millidarcies kg = gas permeability, millidarcies kV = vertical permeability, millidarcies kw = water permeability, millidarcies L = length, ft Lp = length of perforation, ft M = apparent molecular weight, lbm/lbm-mol np = number of perforations p = pressure, psia Pe = reservoir pressure at the boundary, psia pp( p ) = average reservoir pseudopressure, psia2/cp pp( p wf )= flowing bottom hole pseudopressure, psia2/cp ∆pp difference of average reservoir and flowing bottom hole pseudopressure, = psia2/cp Pw = flowing bottom hole pressure, psia q = gas rate, MMscfd Qg = gas flow rate, Mscfd Qw = water flow rate, barrel/day qg = gas flow rate, Mscfd qw = water flow rate, barrel/day rd = altered reservoir radius, ft rdp = crashed zone radius, ft re = outer radius, ft rp = radius of perforation, ft xv rw = wellbore radius, ft S = skin factor, dimensionless s = skin factor, dimensionless Sd = skin factor representing mud filtrate invasion Sdp = skin factor representing perforation density Spp = skin factor due to partial penetration T = temperature, oR Tsc = temperature at standard conditions, oR v = velocity, ft per second y = gas-water or oil-water interface thickness, ft ye = water thickness at the boundary, ft Z = gas deviation factor β = turbulent factor, 1/ ft βr = turbulent factor for reservoir, 1/ ft βdp = turbulent factor for crashed zone, 1/ ft ρ = density, lbm/ft3 ∂p = pressure derivative, psia ∂r = radius derivative, ft φ = porosity γg = specific gravity of gas (air = 1.0) µ = viscosity, centipoises µg = viscosity of gas, centipoises µw = viscosity of water, centipoises xvi ABSTRACT Water inflow may cease production of gas wells, leaving a significant amount of gas in the reservoir. Conventional technologies of gas well dewatering remove water from inside the wellbore without controlling water at its source. This study addresses mechanisms of water inflow to gas wells and a new completion method to control it. In a vertical oil well, the water cone top is horizontal, but in a gas well, the gas/water interface tends to bend downwards. It could be economically possible to produce gas-water systems without water breakthrough. Non-Darcy flow effect (NDFE), vertical permeability, aquifer size, density of well perforation, and flow behind casing increase water coning/inflow to wells in homogeneous gas reservoirs with bottom water. NDFE is important in low-productivity gas reservoirs with low porosity and permeability. Also, NDFE should be considered in the reservoir (outside the well) to describe properly gas wells performance. A particular pattern of water rate in a gas well with leaking cement is revealed. The pattern might be used to diagnose the leak. The pattern explanation considers cement leak flow hydraulics. Water production depends on leak properties. Advanced methods at parametric experimental design and statistical analysis of regression, variance, with uncertainty (Monte Carlo) were used building economic model at gas wells with bottom water. Completion length optimization reveled that penetrating 80% of the gas zone gets the maximum net present value. The most promising Downhole Water Sink (DWS) installation in gas wells includes dual completion with an isolating packer and gravity gas-water separation at the xvii bottom completion. In comparison to Downhole Gas/Water Separation wells, the DWS wells would recover about the same amount of gas but much sooner. The best DWS completion design should comprise a short top completion penetrating 20% - 40% of the gas zone, a long bottom completion penetrating the remaining gas zone, and vigorous pumping of water at the bottom completion. Being as close as practically possible the two completions are only separated by a packer. DWS should be installed early after water breakthrough. xviii CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background and Purpose Water production kills gas wells, leaving a significant amount of gas in the reservoir. One study of large sample gas wells revealed that the original reserves figures had to be reduced by 20% for water problems alone (National Energy Board of Canada, 1995). Gas demand in the US increased 16% during the last decade, but gas production increased only 4.5% during the same period (Energy Information Administration, 2001). The demand for natural gas is projected to increase at an average annual rate of 1.8% between 2001 and 2025 (Energy Information Administration, 2003). Water production is one of the two recurring problems of critical concern in the oil and gas industry (Inikori, 2002). Many gas reservoirs are water driven. Water supplies an extra mechanism to produce the gas reservoir, but it can create production problems in the wellbore. These water production problems are more critical in low productivity gas wells. More than 97% of the gas wells in the United Stated produce at low gas rates. Eight areas account for 81.7 % of the United States’ dry natural gas proved reserves: Texas, Gulf of Mexico Federal Offshore, Wyoming, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Colorado, Alaska, and Louisiana (EIA, 2001). These areas had 144,326 producing gas wells in 1996, but only 366 wells (0.25%) produced more than 12.8 MMscfd (EIA, 2000). Figures 1.1 and 1.2 show actual field data from a well located in a gas reservoir with bottom water drive where water production affected the well performance. 1 250 1500 200 1200 150 900 100 600 50 300 0 0 Gas Rate (Mscf/d) 1800 D ec Ja -97 Fen-9 8 M b-9 ar 8 Ap -98 M r-9 a 8 Ju y-98 n Ju -98 Au l-9 8 Seg-9 p 8 O -98 ct N -9 o 8 D v-9 ec 8 Ja -98 Fen-9 9 M b-9 ar 9 Ap -99 M r-9 ay 9 Ju -99 n Ju -99 Au l-9 9 Seg-9 9 p99 Water Rate (Stb/d) 300 Time (days) Water Rate Figure 1.1 Gas Rate Gas rate and water rate history for an actual gas well. Figure 1.1 shows the history of gas and water rate. Water production begins after eleven months of gas production. Water production increases rapidly, reducing gas rate 30 250 25 200 20 150 15 100 10 50 5 0 0 Recovery Factor (%) 300 D ec Ja -97 n Fe -9 b 8 M -98 a Apr-98 M r-9 ay 8 Ju -98 n Ju -98 Au l-9 8 Seg-9 p 8 O -98 c N t-9 ov 8 D -9 ec 8 Ja -98 n Fe -99 b M -99 ar Ap -99 M r-9 ay 9 Ju -99 n Ju -99 Au l-9 9 Seg-9 9 p99 Water Rate (Stb/d) and killing the well after seven months of water production. Time (days) Water Rate Figure 1.2 Gas Recovery Factor Gas recovery factor and water rate history for an actual gas well. 2 Figure 1.2 shows gas recovery factor and water rate history. The final recovery for the well is 28% at the moment when production stopped. This well died because of the liquid loading inside the wellbore. Liquid loading happens when the gas does not have enough energy to carry the water out of the wellbore. Water accumulates at the bottom of the well, generating backpressure in the reservoir and blocking gas inflow. It is well known that water coning occurs in oil and gas reservoirs, with the water drive mechanism, when the well is produced above the critical rate. Water coning is responsible for the early water breakthrough into the wellbore. Water coning has been studied extensively for oil reservoirs. However, only a few studies of water coning in gas wells have been reported in the literature. Most of the studies assume that water coning in gas and oil wells is the same phenomenon, and correlation developed for oil-water system could be used for gas-water systems. The obvious solution for water coning problems is to produce the well below the critical rate; this solution, however, has become uneconomical for oil wells because of the low value for the critical rate. A correlation for critical rate in gas wells has not been published, yet, to the author’s knowledge. Different well dewatering technologies have been used to control water loading problem in gas wells (pumping units, liquid diverters, gas lifts, soap injections, flow controllers, swabbing, coiled tubing/nitrogen, venting, plunger lift, and one small concentric tubing string). All of them would reduce liquid-loading without controlling water inflow. Recently, a new technology of Downhole Water Sink (DWS) has been develop and successfully used to control water production/coning in oil wells. DWS 3 controls water inflow to the well, by reversing water coning with a second bottom completion. That drains water from under the top completion. The purpose of this research is to evaluate the performance of the DWS technology controlling water production-problems in gas wells. Design and operation of DWS gas wells is also addressed. Moreover, Identification of unique mechanisms improving water production in gas reservoirs, and completion length optimization for conventional gas wells are also approached. 1.2 Statement of Research Problem In response to economic and environmental concerns, in-situ injection of water in the same gas well, without lifting the water to surface, has become a new technology knows as Downhole Gas-Water Separation (DGWS). Similarly to all the other technologies use to solve liquid-loading in gas wells, DGWS does not consider the wellreservoir interaction solving water production problem, either. Therefore, new technologies that consider both, the well and the reservoir, component of the water problem production in gas wells are needed. These technologies, not only have to improve gas production/recovery from the reservoir, but have to reduce the amount of water produced at the surface, too. In the past, water coning in gas wells has not received much attention from researcher in the petroleum industry. The reason for that probably is the general “feeling” that the problem is of minimal importance or even does not exist because of the high gas mobility compared with the water mobility. Therefore, few studies have been done addressing reservoir mechanisms increasing water coning/production in gas reservoir. The low gas price experienced during the last decade reduced the interest in gas well problems at the United States. This low gas price environment, however, has slowly 4 changed since the beginning of this century due to increases in gas demand and reduction in gas supply, pushing people trying to explain, understand and solve gas production/recovery problems. One such attempt includes the “pilot” work conducted for the research described herein. 1.3 Significance and Contribution of This Research The significance of this research stems from the following six studies: • First, the research presents analytical and numerical evidence that the water coning is different in gas wells than in oil wells. • Second, this research identifies vertical permeability, aquifer size, Non-Darcy flow effect (N-D), density of perforation, and flow behind casing as unique mechanisms improving water coning in gas wells. • Third, the research presents a new perspective for N-D flow in gas reservoirs, showing that very well accepted statements in the oil and gas industry about this phenomenon are not correct (Non Darcy flow is not important in gas wells flowing at low rates. Non-Darcy flow coefficient applied only to the well bore properly represents N-D flow throughout the reservoir). • Fourth, this research presents a new procedure to identify flow behind casing (channeling in the cemented annulus) in gas wells. • Fifth, the optimum completion length in gas wells for the maximum net present value is presented. Reservoir and economic parameters affecting water production in gas reservoir are prioritized. • Finally, the research presents an evaluation for DWS in gas reservoirs, identifying the reservoir conditions where the technology could be successful. The best way 5 to operate DWS in gas reservoirs, considering different completion/production parameters, is identified, too. 1.4 Research Method and Approach This research uses two existing commercial numerical simulators (Eclipse 100, and IMEX) and a radial grid model to study water coning mechanisms and DWS evaluation in gas reservoirs. Two commercial numerical simulators are used during the study because the first simulator used for this research (Eclipse 100) does not properly represent N-D in gas reservoirs. N-D flow is identified as an important phenomenon. Another simulator (IMEX) is also used. Analytical models are built to support procedures and results for different mechanisms that increase water coning in gas reservoirs. Field data are used to confirm analytical and numerical results from the N-D flow effect analysis. Statistical analyses are performed with the numerical simulation results from the analysis of mechanisms affecting water coning/production in gas wells. Because of the very nature of this first “pilot” research of DWS in gas reservoir, several different types of approaches, studies, and evaluations are performed. Analytical and numerical approaches are used to identify similarities and differences between water coning in gas and oil wells (Chapter 3). The analysis is focused on the amount of fluid produced, under the same production conditions, from the oil-water and gas-water system, and the shape of the interface (oil-water and gas-water) around the wellbore for both systems. One new analytical model, to investigate gas-water and oil-water interface shape, is developed following Muskat (1982) procedure. The results from the analytical model are compared with results from a numerical reservoir simulator model built with similar characteristics. Another analytical model is built to investigate the amount of fluid produced from both systems. 6 Qualitative studies identifying mechanisms increasing water coning/productions in gas wells are conducted using numerical and analytical models (Chapter 4). Vertical permeability, aquifer size, Non-Darcy flow effect, perforation density, and flow behind casing are evaluated. Analytical models are constructed to confirm the results from the numerical reservoir simulator models. Moreover, one analytical model is developed to enhance the capability of reservoir simulator representing the phenomena of flow behind casing in gas wells because the reservoir simulator does not include the annulus space between the casing and the wellbore wall in its modeling. A new procedure identifying flow behind casing in gas wells, using water production field data, is presented. Analytical and numerical models are used to identify and quantify the importance of Non Darcy flow effect in low productivity gas reservoirs. The results from the models are compared with actual field data (Chapter 5). Recommendations on the correct way of modeling Non Darcy flow in gas reservoir using numerical reservoir simulators are included. Feasibility studies of DWS in gas wells are done using reservoir numerical models (Chapter 6). The studies compare final gas recovery for conventional gas wells and DWS gas wells. Quantitative comparison of final gas recovery between two different technologies solving water production problems in gas wells is made, too [One technology solves the problem in the wellbore (DGWS), and the other one solves the problem in the reservoir (DWS)]. Modeling DWS, and DGWS wells in commercial numerical simulator brings several challenges because of the inability of the reservoir simulator to perform dual completed well with two-different bottom hole condition and two different tubing performance model at the same well. Model modifications (e.g., two 7 wells in the same location with different completion length, two tubing performance models for the same well, etc) are made to evaluate DWS and DGWS wells performance. Sensitivity studies of mechanisms increasing water coning/production in gas wells are conducted using analysis of variance. Three different linear regression models, without interaction among the factors, for ultimate cumulative gas production, net present value and peak gas rate are built and evaluated using numerical reservoir simulation results. One linear regression model for the discount cash flow, considering interaction among the eight factors, is built and evaluated (Chapter 7). Horizontal permeability, aquifer size, permeability anisotropy, initial reservoir pressure, length of completion, gas price, water disposal cost, and discount rate are the factors considered for the analysis. Optimization of Net Present Value with respect to completion length in gas reservoir with bottom-water drive, using the response model from the statistical model and the direct result from the simulator, was done, too. Qualification of the most important operational factors affecting DWS performance in gas reservoir is done using numerical reservoir simulator model (Chapter 8). The analysis includes length-of-top completion, length-of-bottom completion, drained-water rate, separation between the top-and the bottom-completion, and the time to install DWS technology. Recommendations on how to use DWS effectively in gas reservoirs are included. 1.5 Work Program Logic The dissertation is divided into nine chapters. The introduction chapter presents an overview of the problem of water production in gas wells explaining the necessity for new technologies to solve the problem. It also presents a concise statement about the lack 8 of attention about the problem and ends with a presentation of the relevance of this study and its approach. Chapter two presents a literature review of scientific research into water loading theory and different technologies used to solve water production problems in gas wells. Chapter three gives a comparison of water coning in oil and gas wells with specific focus on the interface oil-water and gas-water shape, and the amount of fluid produced in both system at the same operational conditions. Chapter four gives a qualitative analysis about different mechanisms increasing water coning/production in gas reservoir with bottom-water drive. Vertical permeability, aquifer size, Non-Darcy flow effect, perforation density, and flow behind casing were the mechanisms evaluated. Chapter four ends with a new procedure to identify flow behind casing in gas wells using water production data. Chapter five takes an overview of the Non-Darcy effect phenomena in low productivity gas wells. The well assumption that setting Non-Darcy flow at the wellbore properly represents the phenomena is revised. Chapter five ends with a recommendation about the correct way of modeling Non Darcy flow in gas reservoir using numerical reservoir simulators. Chapter six has the statistical evaluation of completion length optimization in gas wells for maximum net present value. The analysis includes sensitivity studies for reservoir and economical factors. Horizontal permeability, aquifer size, permeability anisotropy, initial reservoir pressure, length of completion, gas price, water disposal cost, and discount rate were the factor considered for the analysis. Chapter seven includes the feasibility study of DWS in gas reservoirs. Comparisons of final cumulative gas recovery in conventional and DWS wells are 9 performed. The study includes a comparison between two different technologies solving water production problems in gas wells for the same gas reservoir [one technology solves the problem in the wellbore (DGWS), and the other one solve the problem into the reservoir (DWS)]. Chapter eight reviews the operational parameters involved in DWS performance in gas reservoirs giving recommendation about the way to use the technology. Chapter nine provides conclusions from this research work, including recommendations for future research. 10 CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW Liquid loading or accumulation in gas wells occurs when the gas phase does not provide adequate energy for the continuous removal of liquids from the wellbore. The accumulation of liquid will impose an additional back pressure on the formation, which can restrict well productivity (Ikoku, 1984). The limited gas flow velocity for upward liquid-drop movement is the critical velocity. 2.1 Critical Velocity Turner, Hubbard, and Dukler (1969) analyzed two physical models for removal of gas well liquids: the liquid droplet and the liquid film models. A comparison of these two models with field data led to the conclusion that the onset of load up could be predicted adequately with the droplet model, but that a 20% adjustment of the equation upward was necessary. Equation 2.1 shows Turner et al. correlation. vt = 1.912σ 1 / 4 ( ρ L − ρ g ) 1 / 4 ρ 1g / 2 ………………………………………….(2.1) Where vt is critical velocity (ft/sec), σ is interfacial tension (dynes/cm), ρL is liquid-phase density (lbm/ft3), and ρg is gas phase density (lbm/ft3). Turner et al. equation (Eqn. 2.1) calculating gas critical velocity has gained widespread industry acceptance because of its close agreement with field data, and it is widely referenced in the literature (Hutlas & Granberry, 1972; Libson & Henry, 1980; Ikoku, 1984; Beggs, 1985; Upchurch, 1987; Bizanti & Moonesas, 1989; Smith, 1990; Elmer, 1995). 11 Coleman et al. (1991), using a different set of field data, conclude that the 20% adjustment of Turner’s equation is not needed. They found that the critical flow rate required to keep low pressure gas wells unloaded can be predicted adequately with the Turner et al. (1969) liquid-droplet model without the 20% upward adjustment. Equation 2.2 shows Coleman et al. (1991) correlation. vt = 1.593σ 1 / 4 ( ρ L − ρ g ) 1 / 4 ρ 1g / 2 ………………………………………….(2.2) Where vt is critical velocity (ft/sec), σ is interfacial tension (dynes/cm), ρL is liquid-phase density (lbm/ft3), and ρg is gas phase density (lbm/ft3). Nosseir et al. (2000) explained the difference between Turner et al. (1969) and Coleman et al. (1991) results because both of them ignored flow regime conditions for their data set. Flow regime considerations directly affect the shape of the drag coefficient and hence the critical velocity equation. They found that most of the Turner et al. (1969) data set fall in the highly turbulent region where NRE exceeds a value of 200,000, and the drag coefficient acquires a value of 0.2. Most of the Coleman et al. (1991) data set, however, falls in the region where 104< NRE <2*105 corresponding drag coefficient of 0.44. Nosseir et al. (2000) derived two analytical equations describing the flow regimes for each set of data. Equations 2.3 and 2.4 show Nosseir et al. (2000) correlations. For transition flow regime (104 < NRe < 2*105): vg = 14.6σ 0.35 ( ρ L − ρ g ) 0.21 µ 0.134 ρ g0.426 ……………………………………………(2.3) For highly turbulent flow regime (NRe > 2*105): vg = 21.3σ 0.25 ( ρ L − ρ g ) 0.25 ρ g0.5 ……………………………………………(2.4) 12 Where vg is gas critical velocity (ft/sec), σ is interfacial tension (dynes/cm), ρL is liquid-phase density (lbm/ft3), µ is gas viscosity (lbm/ft/sec), and ρg is gas phase density (lbm/ft3). Sutton et al. (2003) evaluates gas well performance at Subcritical rates. They evaluated six different models describing the presence of a static liquid column in the wellbore with field data from 15 wells. They concluded that the model proposed by Hasan and Kabir (1985) offers the best approach for simulating this phenomenon. 2.2 Critical Rate for Water Coning Water coning happens on the vicinity of the well when water moves up from the free water level in a vertical direction. Production from a well causes a pressure sink at the completion. If the wellbore pressure is higher than the gravitational forces resulting from the density difference between gas and water, then water coning occurs. Equation 2.5 shows the basic correlation between pressure in the wellbore and at the well vicinity for coning. p − p well = 0.433(γ w − γ g )h g − w ………………………………………………(2.5) Where p is average reservoir pressure (psi), pwell is the flowing bottom hole pressure (psi), γw is water specific gravity, γg is gas specific gravity, and hg-w is the vertical distance from the bottom of the well’s completion to the gas/water contact (ft). Critical rate is defined as the maximum rate at which oil/gas is produced without production of water (Joshi, 1991). The critical rate for oil-water systems has been discussed for several authors developing different correlations to calculate that rate. For gas-water system, however, no correlation has been published calculating critical rate, yet. One possible reason for the low interest in critical rate for gas-water system could be the general “feeling” that water coning in gas wells is less important than in oil wells. 13 Muskat (1982), for example, discussing about water coning problem said: “water coning will be much more readily suppressed and will involve less serious difficulties for wells producing from gas zones than for wells producing oil…the critical-pressure differential for water coning will be probably grater by a factor of at least four in gas wells than in oil wells.” Joshy (1991) presets an excellent discussion about critical rate in oil wells. He included analytical and empirical correlation to calculate critical rate. The correlations include: Craft and Hawking method (1959), Meyer, and Garder method (1954), Chaperon method (1986), Schols method (1972), and Hoyland, Papatzacos and Skjaeveland method (1986). Joshy presents equations and example calculation for each method, concluding that the critical rate calculated for each method is different. He said that there is no right or wrong critical correlation, and each one should make decision about which correlation could be used for specific field applications. Meyer, and Garder correlation (1954), and Schols correlation (1972) are shown here as examples of critical rate equations for oilwater system (Eqns. 2.6 and 2.7). Meyer and Garder correlation (1954): qc = 0.001535( ρ w − ρ o )k (h 2 − D 2 ) ……………………………………………(2.6) µ o Bo ln(re / rw ) Where: qc is critical oil rate (STB/D), ρw is water density (gm/cc), ρo is oil density (gm/cc), k is formation permeability (md), h is oil zone thickness (ft), D is completion interval thickness (ft), µo is oil viscosity (cp), Bo is oil formation volume factor (bbl/STB), re is external drainage radius (ft), and rw is wellbore radius (ft). Schols correlation (1972): qo = ( ρ w − ρ o )k o (h 2 − h p2 ) h π * 0.432 + 2049 µ o B o ln(re / rw ) re 14 0.14 ……………………………(2.7) Where: qo is critical oil rate (STB/D), ρw is water density (gm/cc), ρo is oil density (gm/cc), ko is effective oil permeability (md), h is oil zone thickness (ft), hp is completion interval thickness (ft), µo is oil viscosity (cp), Bo is oil formation volume factor (bbl/STB), re is external drainage radius (ft), and rw is wellbore radius (ft). Water coning supplies the liquid source for liquid loading in gas wells. Liquid loading begins when wells start producing gas flowing below the critical velocity in the wellbore. Different concepts and techniques have been used to solve water-loading problems in gas wells. Trimble and DeRose (1976) discussed that Mustak-Wyckoff (1935) theory for critical rates in oil wells could be modified to calculate critical rate for gas wells. The procedure could give an approximate idea about the gas critical rate for quick field calculations. The modified Muskat-Wyckoff (1935) equation presented by Trimble and DeRose (1976) is: 0.000703k g h( p e2 − p w2 ) b r πb 1 + 7 w cos ……………………..…….(2.8) qg = zT R µ g ln(re / rw ) 2b 2h h Where: qg is gas flow rate (Msc/d), kg is effective gas permeability (md), h is gas zone thickness (ft), pe is reservoir pressure at drainage radius (psia), pw is wellbore pressure at drainage radius (psia), µg is gas viscosity at reservoir conditions (cp), z is gas compressibility factor, TR is reservoir temperature (oR), re is external drainage radius (ft), rw is wellbore radius (ft), and b is footage perforated (ft). Equations 2.8 and 2.9 are combined, and solved graphically following MuskatWyckoff (1935) procedure, calculating minimum drawdown preventing water coning. φw −φD gh∆ρ D = 1− 1 − …………………………………………………..(2.9) − ∆p h φw φe 15 Where: φw is potential at well radius (psi), φD is potential at well radius and depth D (psi), φe is potential at drainage radius (psi), g∆ρ is difference in hydrostatic gradient at reservoir conditions between the gas and water (psi/ft), ∆p is pressure drawdown (psia), h is gas zone thickness (ft), and D is distance from formation to cone surface at r (ft). Trimble and DeRose (1976) procedure combined gas flow equation (Eqn. 2.8) with oil graphical solution for Eqn 2.9. Changes in oil density and viscosity with respect to pressure are negligible. Gas properties (density, and viscosity), however, strongly depend on pressure; therefore, the previous procedure should be used as a reference with limitations. 2.3 Techniques Used in Solving Water Loading Techniques used in solving water loading in gas wells could be classified as: • • Tubing lift improvement: - Chemical injection - Physical modification - Thermal - Mechanical Bottom liquid removal: - 2.3.1 Mechanical Tubing Lift Improvement 2.3.1.1 Chemical Injection Chemicals are injected in gas wells with liquid loading problems to prolong the extracting period and enhance wells’ productivity. Foam agents are used to carry the water out of the well. The objective of using foaming agents is to create a molecular bond between the gas and the liquid phases and to maintain its foam stability for a useful 16 period of time so that the accumulated liquid is transported to the surface in a foamed, slurry state (Neves & Brimhall, 1989). Chemical composition, concentration, temperature, water salinity, presence of condensate oil, and hydrogen sulfide are factors controlling foaming agent performance (Xu & Yang, 1995). Foam lift uses reservoir energy to carry out the water, reducing the critical velocity. The most common application of foam lift is in the form of a “soap stick.” The soap bar (1-inch diameter, 1-foot long) is dropped inside the tubing and foam is generated by fluid mixing and agitation with the surfactant dissolved from the soap bar (Saleh, and Al-Jamae’y, 1997). Surfactant concentrations are difficult to gauge and control when the surfactant is dumped into the annulus or the tubing (Lea, and Tighe, 1983). Other applications include injection of surfactant through the annulus from the wellhead, or downhole injection using a capillary string inside the tubing. Libson and Henry (1980) reported successful results injecting foaming agent into the casing annulus in very low permeability gas wells located in the Intermediate Shelf area of Southwest Texas. After 10 days of injecting a foaming agent to the wellhead, the gas rate increased from 142 Mscfd to 664 Mscfd, and water rate increased from 0.8 bwpd to 3.2 bwpd. Placing a capillary string through the producing tubing foam is injected downhole in front of the perforations. Vosika (1983) reported foam injection an economic success in four wells at the Great Green River Basing, Wyoming. Average gas rates increase more than doubled when the foam agent was injected in conjunction with the methanol used to solve traditional freezing problems. 17 Silverman et al. (1997), and Awadzi et al. (1999) reported liquid loading success in gas wells located in the Cotton Valley formation in East Texas using the capillary technique. Gas rate increments in four wells went from 28.2% to 676.3%. Surfactant injection could increase corrosion. Campbell et al. (2001) reported a chemical mixture between the foaming agent and corrosion inhibitor to improve liquid lifting without increasing corrosion in the wellbore. 2.3.1.2 Physical Modification Physical modification of the wellbore has been done to increase gas velocity. Gas velocity is increased, reducing the gas-flow area to improve gas carry capacity. A small concentric tubing string and tubing collar insert have been proposed to improve gas velocity. These methods of producing marginal gas wells are also viewed as a temporary solution to liquid loading. As time elapses and the reservoir pressure declines, the smaller diameter tubing string eventually loads up with liquids. At this point, another method must be employed to help combat the accumulation of liquid in the wellbore (Neves & Brimhall, 1989). Hutlas and Grandberry (1972) reported success using a 1-in tubing string in northwestern Oklahoma and the Texas Panhandle. Running a 1-in tubing string inside the production tubing increased gas rate more than 100% in four wells. Libson and Henry (1980) reported that gas rate increased by 50 Mscfd per installation in the Intermediate Shelf area of southwest Texas when a 1.90-in tubing was installed in a 2 3/8-in production tubing. One-in tubing string run inside 2 7/8-in production tubing increased gas rate, decreasing field annual decline, in seven wells, two sour gas fields, at the Edward Reef in Texas (Weeks, 1982). 18 Yamamoto & Christiansen (1999) and Putra & Christiansen (2001) reported laboratory data for tubing collar inserts increasing liquid lifting. The tubing collar inserts are restrictions installed inside the tubing string. The restrictions alter flow mechanisms and liquid could be lifted by gas flowing below the critical velocity; the effect could be reduced due to the pressure drop across the restriction (Yamamoto and Christiansen, 1999). Parameters affecting the tubing collars inserts include: insert geometric shape, size and spacing of the inserts, gas and liquid flow rates, and pressure drop across the insert (Putra and Christiansen, 2001). Installing concentric coiled tubing is another technique used to increase gas velocity. An estimated 15,000 wells have coiled tubing installed in them as velocity or siphon strings. The coiled string consists of either steel or plastic tubing (Scott and Hoffman, 1999). Adams and Marsili (1992) presented the design and installation for a 20,500-ft coiled tubing velocity string in the Gomez Field, Pecos County, Texas. One 1 ¼-in coiled tubing string was installed in a 4 ½-in production tubing, solving liquid loading problems and increasing gas production more than two-fold. Elmer (1995) discussed the combined application of small tubing string with some extra gas production through the casing/tubing annulus. The small tubing string always flowed above the critical velocity, and some gas, due to extra reservoir production capacity, was produced up to the annulus. Gas production increased 33% in two wells and 91% in another well when this production strategy was used. 2.3.1.3 Thermal Pigott et al. (2002) presented the first successful application of wellbore heating to prevent fluid condensation and eliminate liquid loading in low-pressure, low19 productivity gas wells. The application was in the Carthage Field. A heater cable installed around the tubing string increased wellbore temperature, avoiding liquid condensation. The heating technique alone increased gas production more than 100%. However, combination of the heating technique with a compressor increased gas production more than three-fold. Water-drive gas reservoirs are not good candidates to install the heating technique because of the high amount of energy needed to increase wellbore temperature. Gas wells with low liquid ratio (1 to 8 bbls/MMcf) and liquid loading problems due to condensations are good candidates to apply the heater technique. Currently the major limitation to widespread application of this technique is the comparatively high operating cost. The average cost to operate the well is $5,000/month. This compares to an average operating cost of $1,200/month in offset wells (Pigott et al., 2002). 2.3.1.4 Mechanical Gas lift has been used to improve tubing lifting capacity. Gas lift systems inject high-pressure gas from the casing tubing annulus through valves into liquids in the tubing to reduce their density and move them to the surface (Lea, Winkler, and Snyder, 2003). Gas lift may be used to removed water continuously or intermittently. Gas lift could be used in conjunction with plunger lift and surface liquid diverters to improve its overall efficiency (Neves & Brimhall; 1989). Gas lift could be combined with a small concentric string (siphon string), too (Lea, & Tigher; 1983). The main disadvantage of the gas lift method solving liquid loading is that it would not operate efficiently to the abandonment pressure of the well. The optimum operational efficiency is obtained when the water-lift ratio is in the range from 1.5 to 3 Mscf/bbl of water lifted. The efficiency of the gas lift technique declines in low- 20 productivity gas wells producing in excess of 8 bwpd due to the large amount of gas needed (Melton & Cook, 1964). Hutlas & Granberry (1972) presented four gas wells where gas rate was increased from 50% to more than 100% when a combined gas lift liquid-diverter system was installed to solve liquid loading problems. The wells were located in north-western Oklahoma and the Texas Panhandle in high-pressure fields at depths ranging from 5,100 to 8,600 ft. Stephenson et al. (2000) presented successful installation of gas lift for dewatering gas wells at the Box Church Field – a high water-cut gas reservoir located in Texas. Soap sticks, swabbing, and coiled tubing/nitrogen had been used at the field try to solve liquid loading, but these techniques provided only a short-term solution to the problem. A 50% increase in the average gas rate of the field was reported after the combined mechanism of gas-lift with compressor was installed in four high water-cut (more than 200 bbl/MMscf) wells. Gas lift had been used for dewatering gas wells down-dip increasing and accelerating gas recovery in wells located up-dip in the same reservoir (Girardi et al, 2001; Aguilera et al 2002) using a co-production strategy (Arcaro & Bassiouni, 1987). Some field tests have been done to use Coproduction of gas and water as a secondary gas recovery technique for abandoned water-out wells with limited success (Rogers, 1984; Randolph et al, 1991). 2.3.2 Bottom Liquid Removal Pumps, plunger, swabbing, and gas injection using coiled tubing have been used to remove liquid from the bottom of the well after the gas is flowing below the critical rate. 21 2.3.2.1 Pumps Pumping systems used to solve liquid loading in gas wells include: beam pumping, progressive-cavity pumping, and jet pumping. The main advantage of pumping is that they do not depend on the reservoir energy or on the gas velocity for liquid lifting (Hutlas & Granberry, 1972). Down-hole pumps do have application in gas wells producing high liquid rateover 30 bwdp (Lea & Tigher, 1983). Beam pumping comprises a motor-driven surface system lifting sucker rods within the tubing string to operate a downhole-reciprocating pump. The liquid is pumped up the tubing and the gas is produced out the annulus (Libson & Henry, 1980). Melton & Cook (1964) reported that beam units were the most efficient as well as economical method of solving liquid loading problems in low-pressure shallow gas wells producing between 12 and 15 bwpd on the Panhandle in the Hugton and Greenwood fields. Hutlas & Granberry (1972) presented a successful installation of beam units at the Hugoton field, Kansas solving water-loading problems in gas wells. Gas rate increased from 50% to more than 100% in four wells after the beam unit was installed. Libson & Henry (1980) explained that production increased when beam units were installed in low-gas rate wells (less than 40 Mscf/d) with liquid production between 10 to 40 bwpd at the intermediate Shelf area of southwest Texas, in Sutton County. Henderson (1984) described the technical challenge of installing a beam pump unit to solve liquid loading problems at 16,850 ft in the Pyote Gas Unit 14-1 well at the Block 16 (Ellengurger) field located in Ward Co., Texas. The pump removed 70 bfpd, increasing gas production at the well from 20 to 450 Mscfd. 22 Progressing-cavity pumping systems are based on a surface-driven rotating a rod string which, in turn, drives a downhole rotor operating within an elastomeric stator (Lea, Winkler & Snyder; 2003). Progressive Cavity pumps have been used extensively in the United States for the dewatering of methane coaled-bed wells (Mills & Gaymard, 1996). There are nearly one thousand methane pumps operating in coal basins across the United States (predominately in the Black Warrior, Appalachian, San Juan and Raton Basins) because of the pumps’ ability to adjust from high water rate, often encounter during initial production, as well as low water rates experienced as the coal seams begin to water out. Progressive Cavity pumps can lift water with high contents of coal fines, sand particles, and some gaseous fluid (Klein, 1991). Hebert (1989) discussed the technical limitation of rod pumps in dewatering coalbed wells. A current jet pump system utilizes concentric tubing string for power fluid and produced fluid in an open power fluid system. The gas is produced from the casing annulus. The system allows near complete drawdown since the jet suction pressure is claimed to be capable of being reduced to near the water vapor pressure at depth that is usually lower than the casing sales pressure (Lea & Tighe, 1983). 2.3.2.2 Swabbing Swabbing fluids from a well consists of lowering a swabbing tool down the tubing and physically lifting the fluids to the surface. The objective is merely to lift the liquids from the wellbore until the reservoir energy is able to overcome the remaining hydrostatic head and flow on its own. Swabbing is a very costly procedure that must be repeated every time the well loads up and with more frequency as the bottomhole pressure declines. For this reason, swabbing is viewed as only a temporary solution to 23 liquid loading problems and should only be used during the initial stage of liquid loading where the well will naturally flow for a long period of time. This method is also applicable in cases where a well is loaded up with kill fluid following a workover or when a well has loaded up because it was shut-in for an abnormal period of time (Neves & Brimhal, 1989; Stephenson et al., 2000). 2.3.2.3 Plungers The principle of the plunger is basically the use of a free piston acting as a mechanical interface between the formation and the produced liquids, greatly increasing the well’s lifting efficiency (Beauregard & Ferguson, 1982). Operation of the system is initialized by closing in the flowline and allowing formation gas to accumulate in the casing annulus through natural separation. The annulus acts primarily as a reservoir for storage of this gas. After pressure builds up in the casing to a certain value, the flowline is opened. The rapid transfer of gas from the formation creates a high, instantaneous velocity that causes pressure drop across the plunger and the liquid. The plunger then moves upward with all of the liquids in the tubing above it (Beauregard & Ferguson, 1982). The gas stored in the tubing-casing annulus expands, providing the energy required to lift the liquid. As the plunger approaches the surface, the liquid is produced into the flowline. Additional gas production is allowed after the plunger reaches the surface. After some time, the flowline is closed, the buildup stage starts again, and the plunger falls to the bottom of the well, starting a new cycle (Wiggins et al, 1999). Beeson et al. (1956) developed empirical correlations for 2-in and 2 ½-in plungers based on data from 145 wells at the Ventura field in California. The data correlated and 24 application charts are still used in the industry as feasibility criteria to select well applying plunger lift. Ferguson and Beauregard (1985) include some practical guidelines to the selection of plunger lift. Some static models for plunger lift installations have been proposed and are widely accepted for design due to their simplicity (Wiggins et al, 1999). Foss & Gaul (1965) made a force balance on the plunger to determine minimum casinghead pressure to drive a liquid slug up to the surface. They also worked out the volume of gas required in each cycle, and the minimum amount of time per cycle based on estimates for plunger rise and fall velocities. They used an 85 well data set for some parameters of the model. Hacksma (1972) used the Foss & Gaul (1965) model to show how to calculate the minimum gas-liquid ratio required for operation and the optimum gas-liquid ratio that yields maximum production. Abercrombie (1980) reworked the Foss & Gaul (1965) model, considering a smaller plunger fall velocity in the gas. Dynamic models have also been published to describe the phenomena of a plunger life cycle. Each dynamic model made different assumptions, and different experimental and field data were used to prove the validity of each one. Lea (1982) presented a dynamic model that predicts, at each step, casinghead pressure, plunger position, and plunger velocity until the slug surfaces. The results indicated lower operating pressure and lower gas requirement than the static models. 25 White (1982) experimentally evaluated liquid fallback in a reduced scale apparatus. He concluded that 10% of the initial liquid column fallback for each plunger run. He included some recommendations to design a hybrid plunger-gas lift system. Rosina (1983) developed a dynamic model similar to that of Lea (1982), but taking into account liquid fallback. He also conducted experiments to verify the prediction of his model. Mower et al. (1985) conducted a laboratory investigation on gas slippage and liquid fallback for commercial plungers. They proposed a modified Foss & Gaul (1965) model incorporating these effects. The model was then adjusted to fit field data from four wells. Avery and Evans (1988) proposed a dynamic model for the entire plunger cycle, incorporating the reservoir performance. They assumed that each cycle started as soon as the plunger arrived at the bottom. Marcano and Chacin (1992) presented another dynamic model for the full cycle. Liquid fallback through plunger was considered according to Mower et al.’s (1985) empirical data. Hernandez et al. (1993) conducted experiments to evaluate liquid fallback and plunger rise velocity. Gasbarri and Wiggins presented a dynamic model including a reservoir model. Their model incorporated frictional effect of the liquid slug and the expanding gas above and below the plunger and considered separator and flowline effect. Maggard et al. (2000) developed another dynamic model considering a transient reservoir performance. They concluded that assuming a stabilized reservoir model is a conservative assumption for plunger lift behavior. 26 Optimization of plunger has been presented based on experimental and simulator studies. Baruzzi & Alhanti (1995) recommend no perfect seal plunger during buildup because it obstructs the passage of liquid and gas above the plunger. Wiggins et al. (1999) suggested that optimum production rates would be achieved by allowing the well to produce as long as possible prior to shut in. Excessive gas production periods, however, run the risk of killing the well by building a liquid slug that is too long to be lifted by the remaining energy stored in the annulus. Schwall (1989) reported gas production increases of 50 to 100% after plunger lift installation on gas wells with gas-liquid ratio ranges from 3 Mscf/bbl to 20 Mscf/bbl, and gas rate between 15 Mscfd and 54 Mscfd located in the South Burns Chapel Field in northern West Virginia. Brady & Morrow (1994) evaluated the performance of plunger lift for 130 lowpressure, tight-sand gas wells located in Ochiltree County, Texas. They concluded that the total daily production rate increase attributed to the plunger lift was nearly 70 Mscfd per well, and an incremental 32 Bcf of gross gas reserves are directly attributable to plunger lift installation. Schneider and Mackey (2000) presented results in which initial gas production increased 85% after the wells located in the Eumont gas play at New Mexico were converted to plunger lift from beam pumps. 2.3.2.4 Downhole Gas Water Separation Downhole Gas Water Separation (DGWS) are devices that separate gas from water at the bottom of gas wells. The separated water is reinjected into a non-productive interval, while the gas is produced to the surface (Rudlop & Miller, 2001). 27 Nichols & Marsh (1997) explained that several available commercial configurations or devices have been reported to be suitable for re-injecting water into a lower zone within a gas producing well: • A conventional insert pump with a “bypass” sub • A specially designed insert pump with displaces on the downstroke • Progressive cavity pumps • Electrical submersible pumps Grubb and Duval (1992) presented a new water disposal tool called a “Seating Nipple Bypass.” The bypass tool allows liquid to be lifted up the tubing in the usual way; however, small drain holes permit the liquid to bypass down past the pump to a point in the tubing string below the pump intake. A packer provides hydraulic isolation between production and injection intervals. When the liquid head is sufficiently high, it will then flow into the disposal zone. The bypass tool was tested in seven well in the Oklahoma Panhandle and Southwest Kansas, some of which were temporarily abandoned before the installation. A conventional beam-pumping unit lifted the water. The tool proved successful in five wells. One well produced 348 Mscfd without water after the installation and 300 Mscfd and 300 bwpd before the installation. Klein & Thompson (1992) explained the design criteria and field installation results for a closed-loop downhole injection system used in a water flooding oil well. The pumping system consisted of a sucker rod driven progressing cavity pump installed below the bottom packer. Water from the water source zone entered the pump through a perforated sub in the tubing string above the pump and was pumped into the lower injection zone. The pump was able to inject water at its maximum rate-180 bpd- without 28 any mechanical problems. They concluded that the system could be used for dewatering gas wells. Nichols & Marsh (1997) presented the results for the DGWS installation in a well in central Alberta, Canada. A “bypass tool” with a conventional insert pump and gas powered beam pumping unit was used. With the DGWS system operating, surface production rates were 777 Mscfd gas and 195 bwpd; without the DGWS, production was 565 Mscfd gas and 440 bwpd. In this installation, wellbore diameter limited the pump size and its flow capacity. Rudolph and Miller (2001) reviewed 53 wells with various DGWS installations. Gas production increased in 29 wells, decreased in 13 wells, and did not change in 11 wells. They concluded that DGWS could work in a low rate water producing gas well with competent cement sheath, low pressure, and a high-injectivity disposal zone below the producing interval. Water rate at the surface was successfully cut from 32 bbls/d to zero while gas production increased from 300 Mscfd to 400 Mscfd when a DGWS system (Reverse flow injection pump) was installed in a well at Hugoton Field, Oklahoma (E&P Environment, 2001). 29 CHAPTER 3 MECHANISTIC COMPARISON OF WATER CONING IN OIL AND GAS WELLS Water coning in gas wells has been understood as a phenomenon similar to that in oil well. In contrast to oil wells, relatively few studies have been reported on aspects of water coning in gas wells. Muskat (1982) believed that the physical mechanism of water coning in gas wells is identical to that for oil wells; moreover, he said that water coning would cause less serious difficulties for wells producing from gas zones than for wells producing oil. Trimble and DeRose (1976) supported Muskat’s theory with water coning data and simulation for Todhunters Lake Gas field. They calculated water-free production rates using the Muskat-Wyckof (1935) model for oil wells in conjunction with the graph presented by Arthurs (1944) for coning in homogeneous oil sand. The results were compared with a field study with a commercial numerical simulator showing that the rates calculated with the Muskat-Wyckof theory were 0.7 to 0.8 those of the coning numerical model for a 1-year period. The objective of this study is to compare water coning in gas-water and oil-water systems. Analytical and numerical models are used to identify possible differences and similarities between both systems. 3.1 Vertical Equilibrium A hydrocarbon-water system is in vertical equilibrium when the pressure drawdown around the wellbore is smaller than the pressure gradient generated by the density contrast between the hydrocarbon and water at the hydrocarbon-water interface. Equation 3.1 shows the pressure gradient for gas-water system. 30 ∆p = 0.433(γ w − γ g )h g − w ………………………………………………(3.1) Where ∆p is pressure gradient (psia), γw is water specific gravity, γg is gas specific gravity, and hg-w is the vertical distance from the reference level to the gas-water interface, normally from the bottom of the well’s completion to the gas/water contact (ft). Vertical equilibrium concept is the base for critical rates calculations. Critical rate, in gas-water systems, is defined as the maximum rate at which gas wells are produced without production of water. 3.2 Analytical Comparison of Water Coning in Oil and Gas Wells before Water Breakthrough Two hydrocarbon systems, oil and gas, in vertical equilibrium with bottom water are considered to compare water coning in oil and gas wells before breakthrough. The two systems have the same reservoir properties and thickness, and are perforated at the top of the producing zone. well rw= 0.5 ft K= 100 md φ=0.2 P=2000 psi T= 112 oF 20 ft Oil µ= 1.0 cp ρ= 0.8 gr/cc 50 ft µw=0.56 cp ρw= 1.02 gr/cc Gas 0.017 cp 0.1 gr/cc water re= 1000 ft Figure 3.1 Theoretical model used to compare analytically water coning in oil and gas wells before breakthrough. 31 Figure 3.1 shows a sketch of the reservoir system including the properties and dimensions. The mathematical calculations are included in Appendix A. A pressure drawdown needed to generate the same static water cone below the penetrations, and the fluid rate for each system was calculated. For the system of oil and water and a cone height of 20 ft, a pressure drawdown equal to 2 psi is needed, and the oil production rate is 6.7 stb/d. In the case of a gas-water system, for the same 20 ft height of water cone 8 psi pressure drop is needed, and the gas production rate of 1.25 MMscfd. From this first simple analysis it is evident that it is possible to have a stable water cone of any given height in the two systems (oil-water and gas-water). For the same cone height in vertical equilibrium, pressure drop in the gas-water system is four times greater than the pressure drop in the oil-water system. There is a big difference in the fluids production rate for gas-water and oil-water system. On the basis of British Thermal Units (BTU), the energy content of one Mscf of natural gas is about 1/6 of the energy content of one barrel of oil (Economides, 2001). For this example, the 1.25 MMscf are equivalent to the BTU content of 208 barrels of oil. Therefore, for the same water cone height, it would be economically possible to produce gas-water systems at the gas rate below critical. However, in most cases it would not be not economically possible to produce oilwater systems without water breakthrough. 3.3 Analytical Comparison of Water Coning in Oil and Gas Wells after Water Breakthrough The objective is to compare the shape of oil-water and gas-water interfaces at the wellbore after water breakthrough. After the water breakthrough, there is a stratified inflow of oil or gas with the water covering the bottom section of the well completion. Again, two systems having the same reservoir properties and thickness are compared (oil32 water and gas-water). Both systems are totally penetrated. An equation describing interface shape was derived using the assumptions of Muskat (1982). Figure 2 shows a sketch of the theoretical model, and Appendix A gives the derivation and mathematical computations. In reality the resulting equations will not describe perfectly the inflow at the well. However, they are useful to compare the coning phenomenon in oil-water and gas-water systems. well oil / gas Pw h Pe ye y=? water r r Figure 3.2 Theoretical model used to compare analytically water coning in oil and gas wells after breakthrough. The resulting equations for the water coning analysis are: For the oil-water system the interface height is described as, y= h a + 1 b …………………………………………………………………(3.1) here a, and b are constants described as, a = Qo µ o 2πφkh b= Qw µ w . 2πφkh a h − ye …….………………………………………………………………(3.2) = b ye 33 For the gas-water system the interface height is represented as, y= hp ………………………………………………………………(3.3) [(a / b) + p ] here a, b, and p are calculated using: a = Qg µ g 2πφkh , b= Qw µ w , and 2πφkh a [1 − ( y e / h)] = * p e ………………………………………………………………(3.4) b ( y e / h) r a p + a / b 1 ………………………………………….(3.5) ln e = p e − p − ln e r b b p + a / b From Equation 3.1 it becomes obvious that when the well’s inflow of oil and water is stratified so the upper and bottom sections of completion produce oil and water respectively, under steady state flow conditions the interface between the two fluids is constant and perpendicular to the wellbore because the parameter describing the interface height are all constant and depends on the system geometry. For the gas-water system, nevertheless, the interface height depends on the geometry of the system, and the pressure distribution in the reservoir (Equation 3.3). In order to demonstrate the model for gas-water systems describing the interface between gas-water, one example was solved. The system data are as follow: pe = 2000 psi re = 2000 ft rw = 0.4 ft Bw = 1.0 h = 50 ft ye = 40 ft µw = 0.498 cp k = 100 md φ = 0.25 µg = 0.017 cp The procedure is as follows: 1. Assuming a value for the pressure drawdown (300 psi). 2. Calculating the flowing bottom hole pressure ( p w = p e − ∆p = 2000 − 300 = 1700) , assuming that pw is constant along the wellbore. 34 3. Computing the water flow rate (Qw) using Darcy’s law equation (Kraft and Hawkins, 1991): Qw = 0.00708khw ( p e − p w ) 0.00708 * 100 * 40 * (2000 − 1700) = = 2000 0.498 * 1.0 * ln(2000 / 0.4) µ w Bw ln(re / rw ) 4. Calculating a/b, using EquationA-16 in Appendix A: [1 − (40 / 50)]* 2000 = 500 , which is constant for the system a 1 − ( y e / h) = pe = b ( y e / h) (40 / 50) and independent for the gas rate. 5. Finding Qg, from Equation A-15 in Appendix A: a Qg µ g = b Qw µ w ⇒ 500 = Q g * 0.017 * 5.615 2000 * 0.498 Qg = 5.22 MMscf/d Note that WGR is constant for the system and depends only on the system geometry (ye, h) and pressure drive (pe). 6. Computing 1/b, using Equation A-17 in Appendix A: r ln e 1 rw = b a p e + ( a / b) ( p e − p w ) − ln b p w + ( a / b) 6000 ln 4 1 = = 0.031 b 2000 + 500 (2000 − 1700) − (500) ln 1700 + 500 7. Assuming pressure values between pe and pw, radii r and the gas-water profile y are calculated, using Equations A-14 and A-18 respectively in Appendix A. This is the gas-water interface profile. The equation used to calculate pressure distribution in the reservoir is: 35 r a p + a / b 1 ln e = p e − p − ln e r b b p + a / b ln 2000 + 500 6000 = 0.0312000 − p − 500 ln r p + 500 The equation used to calculate the gas-water interface profile (height) is: y= hp ⇒ [(a / b) + p ] y= 50 * p [500 + p] (Note that this pressure distribution does not depend on values of flow rate but only on their ratio.) Repeating the same procedure for the oil-water system: From Equation A-22 in Appendix A: a (h − y e ) (50 − 40) = = = 0.25 40 b ye Using Equation A-26 in Appendix A: y = h 50 = = 40 a (0.25 + 1) + 1 b For the oil-water system y remains constant ( y = 40) and independent from radius. Fluids Interface Height (ft) Fluids Interface Height (y) vs radii (r) 40.2 40.0 39.8 39.6 39.4 39.2 39.0 38.8 38.6 38.4 0 500 1000 1500 2000 2500 Radii (ft) gas-water system Figure 3.3 oil-water system Shape of the gas-water and oil-water contact for total perforation. 36 Figure 3.3 shows the resulting profiles of the fluid interface in gas-water and oilwater systems. After breakthrough, the oil-water interface at the well’s completion is horizontal, while the gas-water interface tends to cone into the water. For this example the total length of the gas cone is 1.4 ft. 3.4 Numerical Simulation Comparison of Water Coning in Oil and Gas Wells after Water Breakthrough One numerical simulator model was built to confirm the previous finding about the cone shape around the wellbore. Figure 3.4 shows the numerical model with its properties. Table 3.1 shows fluids properties used, and Appendix B contains Eclipse data deck for the models. k= 10 md φ=0.25 Pinitial=2300 psi SGgas= 0.6 APIoil= T= 110 oF Well, rw= 3.3 in Top: 5000 ft 100 layers of 0.5 ft thick 9 layers 5 ft thick, and one layer 550 ft thick. Gas or Oil 50 ft 600 ft Water (W) 5000 ft Figure 3.4 Numerical model used for comparison of water coning in oil-water and gas-water systems. 37 Table 3.1 Gas, water and oil properties used for the numerical simulator model Gas Deviation Factor and Viscosity (Gas-water model) Press Z Visc 100 0.989 0.0122 300 0.967 0.0124 500 0.947 0.0126 700 0.927 0.0129 900 0.908 0.0133 1100 0.891 0.0137 1300 0.876 0.0141 1500 0.863 0.0146 1700 0.853 0.0151 1900 0.845 0.0157 2100 0.840 0.0163 2300 0.837 0.0167 2500 0.837 0.0177 2700 0.839 0.0184 3200 0.844 0.0202 Gas and Water Relative Permeability (Gas-water model) Sg 0.00 0.10 0.20 0.30 0.40 0.50 0.60 0.70 Krg 0.000 0.000 0.020 0.030 0.081 0.183 0.325 0.900 Pc 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Sw 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1.0 Krw 0.000 0.035 0.076 0.126 0.193 0.288 0.422 1.000 Pc 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Oil and Water Relative Permeability (Oil-water model) Sw Krw Krow Pcow 0.27 0.000 0.900 0 0.35 0.012 0.596 0 0.40 0.032 0.438 0 0.45 0.061 0.304 0 0.50 0.099 0.195 0 0.55 0.147 0.110 0 0.60 0.204 0.049 0 0.65 0.271 0.012 0 0.70 0.347 0.000 0 38 Following similar procedures used for the analytical comparison, again, two systems having the same reservoir properties and thickness are compared (oil-water and gas-water). Both systems are totally penetrated and produced at the same water rate. The cone shape around the wellbore is investigated. Figures 3.5 and 3.6 show the results. Irreducible water Saturation Irreducible water Saturation Swept Zone Swept Zone Gas-Water Oil-Water Figure 3.5 Numerical comparison of water coning in oil-water and gas-water systems after 395 days of production. Figure 3.5 depicts water saturation in the reservoir after 392 days of production for gas-water and oil-water systems. The initial water-hydrocarbon contact was at 5050 ft. In both systems the cone is developed almost in the same shape and height. Figure 3.6 shows a zoom view at the top of the cone for both systems. For the oilwater system, the cone interface at the top is flat. For the gas-water system, however, the 39 cone interface is cone-down at the top. For this model the total length of the gas cone is 1.5 ft. One can see that the numerical model represents exactly the same behavior predicted for the analytical model used previously. Gas-Water System Oil-Water System Figure 3.6 Zoom view around the wellbore to watch cone shape for the numerical model after 395 days of production. From comparison of water coning after breakthrough in gas-water and oil-water systems, it is possible to conclude that in gas wells, water cone is generated in the same way as in the oil-water system. The shape at the top of the cone, however, is different in oil-water than in gas-water systems. For the oil-water system the top of the cone is flat. For the gas-water system a small inverse gas cone is generated locally around the 40 completion. This inverse cone restricts water inflow to the completions. Also, the inverse gas cone inhibits upward progress of the water cone. 3.5 Discussion About Water Coning in Oil-Water and Gas-water Systems The physical analysis of water coning in oil-water and gas-water systems is the same. In both systems, water coning is generated when the drawdown in the vicinity of the well is higher then the gravitational gradient due to the density contrast between the hydrocarbon and the water. The density difference between gas and water is grater than the density difference between oil and water by a factor of at least four (Muskat, 1982). Because of that, the drawdown needed to generate coning in the gas-water system is at least four-time grater than the one in oil-water system. Pressure distribution, however, is more concentrated around the wellbore for gas wells that for oil wells (gas flow equations have pressure square in them, but oil flow equations have liner pressure; inertial effect is important in gas well, and negligible in oil wells). This property makes water coning greater in gas wells than in oil wells. Gas mobility is higher that water mobility. Oil mobility, however, is lower than water mobility. This situation makes water coning more critical in oil-water system than in gas-water systems. Gas compressibility is higher than oil compressibility. Then, gas could expand larger in the well vicinity than oil. Because of this expansion, gas takes over some extra portion of the well-completion (the local reverse cone explained in the previous section) restricting water inflow. In short, there are factor increasing and decreasing water coning tendency in both system. The fact that oil-water systems appear more propitious for water coning 41 development should not create the appearance that the phenomena is not important is gaswater system. 42 CHAPTER 4 EFFECTS INCREASING BOTTOM WATER INFLOW TO GAS WELLS In contrast to oil wells, relatively few studies have been reported on aspects of mechanisms of water coning in gas wells. Kabir (1983) investigated water-coning performance in gas wells in bottom-water drive reservoirs. He built a numerical simulator model for a gas-water system and concluded that permeability and pay thickness are the most important variables governing coning phenomenon. Other variables such as penetration ratio, horizontal to vertical permeability, well spacing, producing rate, and the impermeable shale barrier have very little influence on both the water-gas ratio response and the ultimate recovery. Beattle and Roberts (1996) studied water-coning behavior in naturally fractured gas reservoirs using a simulator model. They concluded that coning is exacerbated by large aquifer, high vertical to horizontal permeability, high production rate, and a small vertical distance between perforations and the gas-water contact. Ultimate gas recovery, however, was not significantly affected. McMullan and Bassioni (2000), using a commercial numerical simulator, got similar results to Kabir (1983) for the insensitivity of ultimate gas recovery with variation of perforated interval and production rate. They demonstrated that a well in the bottom water-drive gas reservoir would produce with a small water-gas ratio until nearly its entire completion interval is surrounded by water. The objective of this study is to identify and evaluate specific mechanisms increasing water coning/production in gas wells. Analytical and numerical models are 43 used to identify the mechanisms. The mechanisms investigated are vertical permeability, aquifer size, Non-Darcy flow effect, density of perforation, and flow behind casing. 4.1 Effect of Vertical Permeability It is postulated here, in agreement with Beattle and Roberts (1996), that high vertical permeability should generate early water production in gas reservoirs with bottom water-drive. Vertical permeability accelerates water coning because high vertical permeability would reduce the time needed for a water cone to stabilize. A numerical reservoir model, shown in Figure 4.1, was adopted to evaluate the effect of vertical permeability in gas wells. Reservoir and fluid properties used in the model are shown on Figure 4.1 and Table 3.1, respectively. A sample data deck for the Eclipse reservoir model is contained in Appendix C. Well, rw = 3.3 in φ= 25% Sgr= 20% Pinitial= 2300 psia Swir= 30% S.G.gas=0.6 kr= 10 md 2500 ft 100 layers 1 ft thick 30 ft 100 ft Gas 9 layers 10 ft, and one layer 110 ft thick 200 ft Water 5000 ft Figure 4.1 Numerical reservoir model used to investigate mechanisms improving water coning/production (vertical permeability and aquifer size). Horizontal permeability is set at 10 md, and four different values of vertical permeability, 1, 3, 5, and 7 md, were considered (Permeability anisotropy, kv/kh, equal to 44 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, and 0.7 respectively). The wells are produced at constant tubing head pressure of 500 psia (maximum gas rate). The completion penetrates 30% of the gas zone at the top. The results are shown in Figures 4.2a,b,c, and d. Figure 4.2-a kv/kh = 0.1 Figure 4.2-b kv/kh = 0.3 Figure 4.2-c kv/kh = 0.5 Figure 4.2-d kv/kh = 0.7 Figure 4.2 Distribution of water saturation after 395 days of gas production. 45 Figure 4.2 depicts water saturation in the reservoir after 395 days of gas productions for the four values of vertical permeability. The initial water-gas contact was at 5100 ft. The top of the cone for kv/kh equal to 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, and 0.7 is at 5080 ft, 5038 ft, 5025 ft, and 5021 ft respectively after 760 days of production. For kv/kh equal to 0.1, and 0.3 the water cone is still below the completion and there is no water production. In short, Figure 4.2 shows that water coning increases with vertical permeability. 160 Water Rate (stb/d) 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 7000 Time (Days) Kv / Kh = 0.1 Figure 4.3 Kv / Kh = 0.3 Kv / Kh = 0.5 Kv / Kh = 0.7 Water rate versus time for different values of permeability anisotropy. Figure 4.3 shows water rate versus time for the four different values of vertical permeability. Figure 4.3 shows that water breakthrough time and water rate increase with permeability anisotropy. The shortest water breakthrough time and highest water rate is for kv/kh equal to 0.7. The longest water breakthrough and lowest water rate time is for kv/kh equal to 0.1. 46 From this study, one can say that vertical permeability increases water coning/production in gas wells. The higher the vertical permeability is, the higher the water coning/production of the well. 4.2 Aquifer Size Effects Textbook models of water inflow for material balance computations assume that the amount of water encroachment into the reservoir is related to the aquifer size (Craft & Hawkins, 1991). (For example, van Everdinger and Hurst used the term B’ to represent the volume of aquifer. Fetkovich’s model considers a factor called Wei defined as the initial encroachable water in place at the initial pressure.) Effect of aquifer size was investigated using the same numerical model used on the previous section. Vertical and horizontal permeability are set at 10 and 1 md respectively (kv/kh equal to 0.1). All parameters in the model were kept constant except for the aquifer size. VAD is defined as the ratio of the aquifer pore volume to the gas pore volume. VAD determines the amount of reservoir energy that can be provided by water drive. The aquifer is represented by setting porosity to 10 (a highly fictitious value for porosity), for the outermost gridblocks and the thickness of the lowermost gridblocks are varied from 110 to 710 ft to adjust aquifer volume. VAD is varied from 346 to 1383. A sample data deck for the Eclipse reservoir model is included in Appendix C. The results are shown in Figures 4.4-a,b,c, and d. Figure 4.4 depicts water saturation in the reservoir after 1124.8 days of gas productions for the four values of VAD. The initial water-gas contact was at 5100 ft. The top of the cone for VAD equal to 346, 519, 864, and 1383 is at 5046 ft, 5040 ft, 5034 ft, and 5030 ft respectively; after 760 days of production. Figure 4.4, consequently, shows that water coning increases with the aquifer size. 47 Figure 4.4-a VAD = 346 Figure 4.4-b VAD = 519 Figure 4.4-c VAD = 864 Figure 4.4-d VAD = 1383 Figure 4.4 Distribution of water saturation after 1124.8 days of gas production. Figure 4.5 shows water rate versus time for the four different values of vertical permeability. Figure 4.5 shows that water rate increase with aquifer size. Water breakthrough time, however, is not affected by aquifer size. 48 160 Water Rate (stb/d) 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 Time (Days) Vad = 346 Figure 4.5 Vad = 519 Vad = 864 Vad = 1383 Water rate versus time for different values of aquifer size. Figures 4.3 and 4.5 show that vertical permeability is more important than aquifer size in controlling the water breakthrough time. Both aquifer size and vertical permeability, however, play an important role in increasing water rate. From this study, one could conclude that aquifer size increases water coning/production in gas wells without affecting water breakthrough time. The higher the size of the aquifer is, the higher the water coning/production of the well. 4.3 Non-Darcy Flow Effects Non-Darcy flow generates an extra pressure drop around the well bore that could intensify water coning. Non-Darcy flow happens at high flow velocity, which is a characteristic of gas converging near the well perforations. The extra pressure drop is a kinetic energy component in the Forchheimer’s formula (Lee & Wattenbarger, 1996), − dp = βρv 2 ……………..………….………..…………………..(4.1) dL 49 The effect of Non-Darcy flow in water production was studied analytically for two cases of well completion: complete penetration of the gas and water zones, and penetration of the gas zone. In the second case the well perforated in only the gas zone. Figure 4.6 illustrates the completion schematic and the production system properties. rw= 0.5 ft rw= 0.5 Ga K= 100 md P=2500 40 µw=0.56 cp ρw= 1.02 gr/cc K= 100 md Bw= 1.0 rb/STB K= 100 md P=2500 psi o T= 120 F Kh / Kv = 40 µw=0.56 cp ρw= 1.02 gr/cc K= 100 md Bw= 1 0 rb/STB Wate re= 2500 Figure 4.6 production. 4.3.1 Gas 40 ft Kh / Kv = 10 40 ft Water re= 2500 ft Analytical model used to investigate the effect of Non-Darcy in water Analytical Model The analytical model of the well inflow comprises the following components: Gas inflow model (Beggs, H.D., 1984): Pe2 − Pw2 = 1.422Tµ g Zq g k g hg [ln(r / r ) + S + Dq ] .………..……………………...(4.2) e w g where: S = S d + S dp + S pp …………………………….………………….(4.3) and D = D r + D p …………………………………………………………(4.4) 50 Water inflow model (Beggs, H.D., 1984): qw = 0.00708k w hw ( Pe − Pw ) ……………………………………………..….(4.5) µ w Bw [ln(re / rw ) + S ] where: S = S d + S dp + S pp …………………..……………………………(4.6) Skin factor representing mud filtrate invasion (Jones & Watts, 1971): Sd = hg (rd − rw ) k g − 1 ln(rd / rw ) ………………………………...(4.7) 1 − 0.2 h per h per k d Skin factor representing perforation density (McLeod, 1983): k hg k ln(rdp / r p ) g − g …….……………………………………...(4.8) S dp = k dp k d Lpnp [ ] Skin factor due to partial penetration (Saidikowski, 1979): hg hg S pp = − 1 ln rw h per k H − 2 …………………………………………….…(4.9) kV Non-Darcy skin around the well (Beggs, H.D., 1984): Dr = βr = 2.22 *10 −15 γ g k g β r µ g h g rw ………………..……………………………..(4.10) 2.33 *1010 …………………….……..….……………………….(4.11) k 1g.2 Non-Darcy skin in the crashed rock around the perforation tunnels (McLeod, 1983): β dp k g h g γ g ……………………………………….…...(4.12) D p = 2.22 *10 −15 2 2 n p L p r p µ g β dp = 2.6 *10 10 ……………………………………………..…………(4.13) k dp Figure 4.7 shows a sketch for the skin component at the well for a single perforation. 51 Cement Mud cake Crashed zone kdp rdp rp kr Lp rw kd rd Filtrate invasion Casing Figure 4.7 Skin components at the well for a single perforation for the analytical model used to investigate Non-Darcy flow effect in water production. Computation procedure with the analytical model was as follows. 1. Assume constant value for the pressure the drawdown at 100 psia, 300 psia, 500 psia, 1000 psia, and 1500 psia. 2. Calculate gas and water production rates for the initial condition using Equations 4.2 and 4.5, respectively. 3. Compute the rates for water and gas for several intermediate steps of gas recovery 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 95%. (Note that the fraction of initial gas zone invaded by water represents the gas recovery factor.) The above procedure was repeated for three different scenarios. The scenarios were: without Non-Darcy and skin effects, including only skin effect, and including both skin and Non-Darcy effects. The results of the study are shown in Figures 4.8 to 4.11. 52 Water-Gas Ratio (BLS/MMSCF) 1,600 1,400 1,200 1,000 800 600 400 200 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1 Recovery Factor (%) Draw-Down = 100 psi Draw-Down = 300 psi Draw-Down = 1000 psi Draw-Down= 1500 psi Draw-Down = 500 psi Figure 4.8 Water-Gas ratio versus gas recovery factor for total penetration of gas column without skin and Non-Darcy effect. Figure 4.8 demonstrates the “delayed” effect of water in a gas well completed in the gas zone when Non-Darcy and skin are ignored. Not only does the problem occur after 80% of gas recovered but also Water-Gas ratio (WGR) is independent of pressure drawdown and production rates. Water-Gas Ratio (BLS/MMSCF) 1,600 1,400 1,200 1,000 800 600 400 200 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1 Recovery Factor (%) Draw-Down = 100 psi Draw-Down = 300 psi Draw-Down = 1000 psi Draw-Down = 1500 psi Draw-Down = 500 psi Figure 4.9 Water-Gas ratio versus gas recovery factor for total penetration of gas column including mechanical skin only. 53 Figure 4.9 indicates that mechanical skin alone slightly increases WGR. Water-Gas Ratio (BLS/MMSCF) 1,600 1,400 1,200 1,000 800 600 400 200 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1 Recovery Factor (%) Draw-Down = 100 psi Draw-Down = 300 psi Draw-Down = 1000 psi Draw-Down = 1500 psi Draw-Down = 500 psi Figure 4.10 Water-Gas ratio versus gas recovery factor for total penetration of gas and water columns, skin and Non-Darcy effect included. Figure 4.10 indicates that combined effects of skin and Non-Darcy flow would strongly increase water production in gas wells. Also, WGR increases with increasing pressure drawdown. Figure 4.11 shows WGR histories for a gas well penetrating only the gas column. Reducing well completion to the gas column does not change WGR development; the WGR history is similar to that of complete penetration. Interestingly, although the completion bottom is at gas-water contact, the production is practically water-free for almost half of the recovery. This finding is in agreement with the analytical analysis of gas-water interface and the inverse internal cone mechanism presented in previous sections. 54 Water-Gas Ratio (BLS/MMSCF) 1,600 1,400 1,200 1,000 800 600 400 200 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1 Recovery Factor (%) Draw-Down = 100 psi Draw-Down = 300 psi Draw-Down = 1000 psi Draw-Down = 1500 psi Draw-Down = 500 psi Figure 4.11 Water-Gas ratio versus gas recovery factor for wells completed only through total perforation of the gas column with combined effects of skin and NonDarcy. From this study it is evident that: • Non-Darcy and distributed mechanical skin increase water gas ratio (WGR) by reducing gas production rate and increasing water inflow, and the two effects accelerate water breakthrough to gas well. • It does not make much difference how much of the well completion is covered by water as long as the completion is in contact with water. 4.3.2 Numerical Model The above observations regarding mechanical skin and Non-Darcy (N-D) effects have been based on a simple analytical modeling. The analytical results are verified with a commercial numerical simulator for the well-reservoir model shown in Figure 4.1. The model’s characteristics are: The well totally perforates the gas zone. Mechanical skin is set equal to five. Horizontal permeability is 10 md. Vertical permeability is 10% of the 55 horizontal (1 md). Frederick and Graves’ (1994) second correlation was used to calculate N-D effect. The wells were run at constant gas rate of 10 MMscfd. Two scenarios were considered: one without skin and N-D, and the other one including both (skin and N-D). A sample data deck for IMEX reservoir model is included in Appendix C. Figures 4.12 and 4.13 show the results. 12 Gas Rate (MMscfd) 10 8 6 4 2 0 0 500 1000 1500 2000 2500 Time (Days) Without Skin and N-D Including Skin and N-D Figure 4.12 Gas rate versus time for the numerical model used to evaluate the effect of Non-Darcy flow in water production. Figure 4.12 shows that after 1071 day of production, the well (including skin and N-D) cannot produce at 10 MMscfd. At this point water production affects gas rate. The well without skin and N-D is able to produce at 10 MMscfd for 1420 days. 56 250 225 Water Rate (stb/d) 200 175 150 125 100 75 50 25 0 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 1000 1100 Time (Days) Without Skin and N-D Including Skin and N-D Figure 4.13 Water rate versus time for the numerical model used to evaluate the effect of Non-Darcy flow in water production. Figure 4.13 shows that water rate is always higher for the cases where skin and ND are included than when these two phenomenon are ignored. In short, skin and NonDarcy effect together increase water production in gas reservoirs with bottom waterdrive. These results are in general agreement with the outcomes from the analytical model evaluated in the previous section. 4.4 Effect of Perforation Density Perforations concentrate gas inflow around the well, increase flow velocity, and further amplify the effect of Non-Darcy flow. The effect is examined here using the modified analytical model utilized in section 4.3.1 (Figure 4.7). Similar calculation procedure described on section 4.3.1 was used including skin and Non-Darcy effect. Two different values of perforation density, four shoots per foot to 12 shoots per foot, were 57 employed. Behavior of the water-gas ratio was evaluated. The results are shown in Figure 4.14. Water-Gas Ratio (BLS/MMSCF) 1,400 1,200 1,000 800 600 400 200 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1 Recovery Factor (%) Drawdown = 100 psi (4 spf) Drawdown = 500 psi (4 spf) Drawdown = 1000 psi Drawdown = 100 psi (12 spf) Drawdown = 500 psi (12 spf) Drawdown = 1000 psi (12 spf) Figure 4.14 Effect of perforation density on water-gas ratio for a well perforating in the gas column, skin and Non-Darcy effect are included. There is a 40 % reduction in water-gas ratio resulting from a three-fold increase in perforation density. Figure 4.14 shows the effect of decreased pressure drawdown that significantly reduces WGR. Thus, well perforations increases water production due to Non-Darcy flow effect; the smaller the perforation density, the higher the water-gas ratio. 4.5 Effect of Flow behind Casing It is postulated here that a leak in the cemented annulus of the well could increase water coning in gas wells. Water rate and water breakthrough time with and without leaking cement (cement channel) were evaluated. Typically, cement channeling in wells would result from gas invasion to the annulus after cementing. Hydrostatic pressure of cement slurry is reduced due to the 58 cement changing from liquid to solid. Once developed, the channel would provide a conduit for water from gas-water contact to the perforations. Figure 4.15 shows the cement-channeling concept. It is assumed that the channel has a single entrance at its end. Cement channel Skin damage zone Skin damage zone Gas Gas Cement channel Gas-Water contact Water Figure 4.15-a A channel develops in the annulus during cementing and before perforating. The initial gaswater contact is below the channel bottom. Gas Water Figure 4.15-b The well starts producing only gas. A water cone develops, and its top reaches the channel. Water Figure 4.15-c Water is “sucked” into the channel and the well starts producing gas and water. Figure 4.15 Cement channeling as a mechanism enhancing water production in gas wells. 4.5.1 Cement Leak Model The channeling effect was simulated by assigning a high vertical permeability value to the first radial outside the well in the numerical simulator model. It is assumed that fluids could only enter the channel at the channel end. A relationship between the size of a channel and permeability in the first grid was developed. Figure 4.16 shows the modeling concept. 59 First grid with high vertical channel casing well Figure 4.16-a Well with a channel in the cemented annulus. Figure 4.16 Figure 4.16-b Simulator’s first grid with high vertical permeability. Modeling cement leak in numerical simulator. The relationship between flow in the channel and the simulator’s first grid was based on the same value of pressure gradient in both systems. A circular channel with a single entrance at its end and laminar single-phase flow of water were assumed. Flow equation for linear flow in both systems was used in the model. The linear flow equation describing laminar flow through pipe is (Bourgoyne et al, 1991): ∆p f ∆L = µv 1500d ch2 where: v = Thus, ………………………………………………………………(4.15) 17.16q d ch2 ……………………………………………………………(4.16) d4 q = 87.41 ch …………………………………………….……...(4.17) µ ∆p f ∆L 60 Darcy’s law for linear flow in the simulator’s first grid is (Amyx et al, 1960): q = 0.001127 A1 = π 4 *144 k v1 A1 ∆p µ ∆L ………………………………………………………(4.18) (d − d ) ………………………………………………………….(4.19) 2 1 2 w Including Eq. 4.19 in Eq. 4.18, then: ( ) k d 2 − d w2 q = 6.15 *10 − 6 v1 1 …………….……………………………….…(4.20) µ ∆p ∆L kv1 = vertical permeability on the first grid around the wellbore, md where: A1 = first grid’s area, in2 d1 = first grid’s diameter, in dch = channel’s diameter, in dw = well’s diameter, in Equations 4.17 and 4.20 should be equal to represent the same behavior in both systems, then: 87.41 d ch4 µ = 6.15 *10 16 Thus, k v1 = 1.42 *10 7 ( k v1 d 12 − d w2 ) µ d ch4 (d − d ) 2 1 2 w …………………………..……………………(4.21) From the numerical model: d w = 8 in d 1 = 10 in For the purpose of this study, the author will call flow capacity the ratio of flow rate to the pressure gradient expressed in barrels per day divided by pound per square inch per foot [(bbl/day)/ (psi/ft)]. 61 Flow Capacity [bbl/day]/[psi/ft] and First Grid Vertical Permeability [md] 100,000,000.00 10,000,000.00 1,000,000.00 100,000.00 10,000.00 1,000.00 100.00 10.00 1.00 0.10 0.01 0.01 0.1 1 10 Channel Diameter [in] First Grid Vertical Permeability [md] Flow Capacity [bbl/day/psi] Figure 4.17 Relationship between channel diameter and equivalent permeability in the first grid for the leaking cement model. Figure 4.17 shows the relationship between keq and dch, after the channel values and well diameter are included in Eq. 4.21. Values of cement leak’s flow capacity using Eq. 4.17 are also included in Figure 4.17. However, this flow capacity is over calculated with this equation because the hydrostatic head pressure is not included. The flow capacity values are included to have an idea about the daily water rate for any channel size. A channel with diameter equal to 1.3 inches was assumed. The flow area for this channel size equals to 4.7% of the total annulus area for 8-inch casing in a 10-inch hole. From Figure 4.17, the channel’s 1.3-inch diameter has equivalent permeability of 1,000,000 md and flow capacity of 110 [bbl/day]/[psi/ft]. Thus, in the simulator, vertical permeability of the first grid was set equal to 1,000,000 md. Three different scenarios, shown in Figure 4.18, were analyzed with the numerical simulator to investigate water breakthrough: without a channel, channel along the entire 62 gas zone (100 ft), and a channel over 80% (80 ft) of the gas zone. Wells are produced at a constant gas rate of 25 MMscfd. 50 ft 50 ft kr = 100 md kv = 10 md 100 ft 100 ft kv = 10E+6 md from 0 to 100 ft kr = 0 md from 50 to 100 ft kv = 10E+6 md from 0 to 80 ft 50 ft 100 ft kr = 0 md from 50 to 80 ft kv = 10E+6 md from 81 to 85 ft Gas-Water contact Gas-Water contact Gas-Water contact kv = 10E+6 md from 101 to 105 ft 300 ft 300 ft 300 ft 4.18-a No channel. 4.18-b Channel along the gas zone (100 ft). 4.18-c Channel in 80% of gas zone (80 ft). Figure 4.18 Values of radial and vertical permeability in the simulator’s first grid to represent a channel in the cemented annulus. The modeling concept is shown in Figure 4.18. Vertical permeability was set equal to 1,000,000 md in the first grid throughout the channel’s length (100 ft or 80 ft). Radial permeability in the first grid was set equal to zero from the bottom of the completion (50 ft) to the bottom of channel assuring no radial entrance to the channel. Also, vertical permeability was set equal to 1,000,000 md 5 ft below the channel end, without changing radial permeability value, for both cases. Sample data deck for Eclipse reservoir model is included in Appendix C. This model only partially represents the situation shown in Figure 4.15 because, in the numerical model, the pressure difference between the first and second grids is small, as the simulator models an open hole completion. (For perforated completion, one 63 would expect a large difference between the first and second grids representing the pressure drop due to the flow in perforations.) Thus, for open-hole completions we would expect smaller effect of water breakthrough and water production rate than that in the perforated completions. However, the simulation could give an idea about the phenomenon shown in Figure 4.15. 4.5.1.1 Effect of Leak Size and Length Results for the effect of leak length, from the simulation study, are plotted in Figure 4.19. Water Production Rate (stb/day) 160 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 1000 Time (days) Without Channel Channel 80 ft long Channel 100 ft long Figure 4.19 Effect of leak length: Behavior of water production rate with and without a channel in the cemented annulus. The results can be summarized as follows: When the channel taps the water zone, water production starts from the first day of production and increases rapidly until 40 bbl/day after 25 days of production. Then, water rate tends to stabilize at the value between 50 and 60 bbl/day. Finally, after 625 days of production, the water rate increases exponentially. At this time, the water cone enters the well completion. 64 For the scenario with the channel ending above the initial gas-water contact (80 ft long), water production starts after 90 days of production and increases to 30 bbl/day after 550 days. Next, the water rate tends to stabilize at 30 bbl/day. Finally the water rate increases following an exponential trend after 700 days of production. (At this time the water cone reaches the completion.) Without a channel, water production starts after 625 days of production and increases in an exponential trend. Effect of channel size in performance of water production was investigated, too. Channel diameters of 0.5-inch, 0.9-in, and 1.3-in were selected. The no-channel scenario was included in the analysis. From Figure 4.17, 25,000 md, 250,000 md, and 1,000,000 md were the equivalent vertical permeability values for the channel diameter selected. The two channel length-scenarios evaluated previously were considered. Figures 4.20 and 4.21 show the results for the channel in 80% of the gas zone and along the total gas zone, respectively. Water Production Rate (stb/day) 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 1000 Time (days) Without Channel Channel 80 ft long, channel size: 0.5 in Channel 80 ft long, channel size: 0.9 in Channel 80 ft long, channel size: 1.3 in Figure 4.20 Effect of channel size: Behavior of water production rate for a channel in the cemented annulus above the initial gas-water contact. 65 Water Production Rate (stb/day) 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 1000 Time (days) Without Channel Channel 100 ft long, channel size: 0.5 in Channel 100 ft long, channel size: 0.9 in Channel 100 ft long, channel size: 1.3 in Figure 4.21 Effect of channel size: Behavior of water production rate for a channel in the cemented annulus throughout the gas zone ending in the water zone. Figures 4.20 and 4.21 show similar behavior of water production rates for different channel sizes. The water rate increases, showing the same pattern described previously. First, water rate increases linearly; next it stabilizes; and finally it increases exponentially. However, the size of the channel controls the water rate. The smaller the channel, the lower the water production rate. The water breakthrough time is not affected by the channel size. From this first study, one could make the following comments: • A channel in the well cemented annulus reduces water breakthrough. This reduction is a function of the length of the channel: the longer the channel, the smaller the breakthrough time. • Channel size controls the amount of water produced without affecting the water breakthrough time. The smaller the channel size, the lower the water production rate. 66 • Another interesting observation is that there is a particular pattern for water production rate when a channel is considered. First, there is no water production. Next, water production begins and water rate increases almost linearly. This increment is more dramatic when the channel is originally into the water zone. Then, there is stabilization of the water rate. Finally, the water rate increases exponentially. • The water rate pattern in the presence of a channel is explained as follows: First, there is no water production, so single-phase gas flows throughout the channel. Second, water breaks through when the top of the water-cone reaches the bottom of the channel. Two-phase flow begins (gas and water) to occur in the channel. Third, the water rate increases because the cone continues its upward movement. However, an inverted gas cone is generated at the bottom of the channel (as it was explained in Chapter 2), so two-phase flow continues in the channel with water rate increasing and gas rate decreasing. Four, water rate stabilizes. At this point the water cone eliminates the local gas cone at the bottom of the channel, so singlephase flow (water) occurs in the channel. Finally, the water rate increases exponentially when the top of the water-cone reaches the completion. • The last (exponential) increase of water production is identical in all cases thus indicating the effect of water coning unrelated to the leak. 4.5.1.2 Diagnosis of Gas Well with Leaking Cement Based on the results shown in the previous section, one procedure to identify a gas well with leaking cement was developed: 67 i. Make a Cartesian plot of water production rate versus time and identify early (prior to exponential) inflow of water; ii. Analyze early water rate behavior after the breakthrough and before the exponential increase; iii. If you see an initial increase of water production followed by rate stabilization, chances are the well has leaking cement; iv. Confirm the diagnosis with cement evaluation logs; v. Verify with completion/production engineers a possibility of early water due to hydraulic fracturing or water injection wells; vi. Verify the leak by history matching with the numerical simulator model described above: Water breakthrough time with the channel length, and water rate with the channel size and length; vii. A graph similar to Figure 4.17 could be made for the specific well geometry evaluating channel size. 68 CHAPTER 5 EFFECT OF NON-DARCY FLOW ON WELL PRODUCTIVITY IN TIGHT GAS RESERVOIRS Eight areas account for 81.7 % of the United States’ dry natural gas proved reserves: Texas, Gulf of Mexico Federal Offshore, Wyoming, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Colorado, Alaska, and Louisiana (EIA, 2001). These areas had 144,326 producing gas wells in 1996, but only 366 wells (0.25%) produced more than 12.8 MMscfd (EIA, 2000). Non-Darcy effect was identified in the previous chapter as a mechanism for increasing water coning/production in gas reservoirs. Traditionally, the Non-Darcy (N-D) flow effect in a gas reservoir has been associated only with high gas flow rates. Moreover, all petroleum engineering’s publications claim that this phenomenon occurs only near the wellbore and is negligible far away from the wellbore. As a result, the N-D flow has not been considered in gas wells producing at rates below 10 MMscfd, or it has been assigned only to the wellbore skin area. Additional pressure drop generated by the N-D flow is associated with inertial effects of the fluid flow in porous media (Kats et al., 1959). Forchheimer presented a flow equation including the N-D flow effect as (Lee & Wattenbarger, 1996), − dp µ = v + 3.238 *10 −8 βρv 2 ………………………………………….(5.1) dL k where dp/dL= flowing pressure gradient; v= fluid velocity; µ = fluid viscosity; k= formation permeability; ρv2= inertia flow term; and β= inertia coefficient. 69 In deriving an analytical model for β, many authors considered permeability, porosity, and tortuosity the most important factors controlling β (Ergun & Orning, 1949; Irmay, 1958; Bear, 1972; Scheidegger, 1974). Empirical correlations (Janicek & Katz, 1955; Geertsman, 1974; Pascal et al, 1980; Jones, 1987; Liu et al, 1995; Thauvin & Mohanty, 1998) supported the analytical models and included rock type as another important factor. Also, liquid saturation was found to be another important factor affecting inertia coefficient from lab experiments. β increases with water (immobile) saturation (Evan et al, 1987; Lombard et al, 1999). Experimental studies provided data needed for inclusion of liquid saturation in the equation for inertia coefficient (Geertsman, 1974; Tiss & Evans, 1989). Frederic and Graves (1994) presented three empirical correlations for a wide range of permeability. In the actual wells, β can be calculated from the multi-flow rate tests using Houper’s procedure (Lee & Wattenbarger, 1996). The object of this study is to identify the effect of N-D in gas wells flowing at low rates (below 10 MMscfd) and to qualify the effect of N-D on the cumulative gas recovery. 5.1 Non-Darcy Flow Effect in Low-Rate Gas Wells Table 5.1 shows data used to evaluate the effect of N-D on the well’s flowing pressure using the analytical model of the N-D flow effect described in Appendix D. Three different permeability values were used for the study, 1, 10, and 100 md. Six porosity values were used, 1, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25%. Eight values of gas rates were included in the analysis, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 50, 100, and 1000 MMscfd. 70 Table 5.1 Data used for the analytical model A = 17,424,000 ft2 CA = 31.62 rw = 0.3 ft h = 50 ft M = 17.38 lb/lb-mol s=0 T = 580 oF Psc = 14.7 psia Tsc = 60 oF Pwf = 2500 psia µ = 0.018978 cp hper = 15 ft Using equations D-4 and D-5, included in Appendix D, a and b were calculated for the analytical model. F was calculated with equation D-8 in Appendix D. Figures 5.1 F (Fraction of Pressure Drop Generated by Non-Darcy Flow) to 5.3 show graphs of F versus gas rates for the three permeability values. 1.0 0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0.0 0.1 1 10 100 1000 Gas Rate (MMscf/D) Poro= 1% Poro= 5% Poro= 20% Poro= 25% Poro= 10% Poro= 15% Figure 5.1 Fraction of pressure drop generated by N-D flow for a gas well flowing from a reservoir with permeability 100 md. Figure 5.1 shows the results for permeability of 100 md. When porosity is 1%, the contribution to the total pressure drop generated by the inertial component is 50% for the 71 gas rate 6.0 MMscfd. For gas rates higher than 33 MMscfd (when porosity is 25%), the F (Fraction of Pressure Drop generated by Non-Darcy flow) N-D flow completely controls the total pressure drop. 1.0 0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0.0 0.1 1 10 100 1000 Gas Rate (MMscf/D) Poro= 1% Poro= 5% Poro= 20% Poro= 25% Poro= 10% Poro= 15% Figure 5.2 Fraction of pressure drop generated by N-D flow for a gas well flowing from a reservoir with permeability 10 md. Figure 5.2 shows the results for permeability of 10 md. Reducing permeability from 100 md to 10 md significantly increases the contribution of the N-D flow to the total pressure drop. N-D flow controls pressure-drop in the system for gas rates greater than 2.2 MMscfd when porosity is 1% and 11 MMscfd when porosity is 25%. Figure 5.3 shows the results for permeability of 1 md. The inertial component controls the pressure drop for gas rates higher than 0.7 MMscfd when porosity is 1% and 3.6 MMscfd for porosity 25%. 72 F (Fraction of Pressure Drop Generated by Non-Darcy Flow) 1.0 0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0.0 0.1 1 10 100 1000 Gas Rate (MMscf/D) Poro= 1% Poro= 5% Poro= 20% Poro= 25% Poro= 10% Poro= 15% Figure 5.3 Fraction of pressure drop generated by N-D flow for a gas well flowing from a reservoir with permeability 1 md. The results show that the N-D flow effect increases with decreasing porosity and permeability. This observation is physically correct because lower porosity and permeability somewhat increase flow velocity and the resulting inertial effect. From this analytical study, one could conclude that not only gas rate, but rock properties, permeability, and porosity control the contribution of N-D flow effect to the total pressure drop in gas reservoirs. Even for the low-gas rate, the N-D effect is still important for wells in low-porosity, low-permeability gas reservoirs. It is possible to have a gas well flowing less than 1 MMscfd, with the pressure drawdown resulting entirely from the N-D flow. 5.2 Field Data Analysis To support the previous observation, multi-rate test field data from three wells, described by Brar & Aziz (1978), were selected to calculate F. The data is shown in Table 5.2. 73 Table 5.2 Rock properties and flow rate data for well A-6, A-7, and A-8 from Brar & Aziz (1978) Well Name Porosity (%) Thickness (ft) kh (mdft) Permeability (md) a (psia2/(MMscfd)) b (psia2/(MMscfd)2) q1 (MMscfd) q2 (MMscfd) q3 (MMscfd) q4 (MMscfd) A-6 A-7 A-8 8.3 8 67.5 56 35 454 169 455 2392 3 13 5.3 107,720 1,158,690 30,150 24,470 68790 400 4.194 8.584 31.612 6.444 9.879 44.313 8.324 12.867 56.287 9.812 Using the a and b published values for each well, F was calculated again using equation D-8 from Appendix D, and the results are shown in Figure 5.4. No attempt has been made to revise the published values of a and b. The porosity value reported for Well A-8 seems too high. Although Brar & Aziz (1978) did not explain the high porosity value for Well A-8, the author believes the reservoir may comprise fractured chalk, or F (Fraction of Pressure Drop Generated by Non-Darcy Flow) diatomite. 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0.0 1 10 100 Gas Rate (MMscf/D) Well-A6 Well-A7 Well-A8 Figure 5.4 Fraction of pressure drop generated by Non-Darcy flow for wells A-6, A7, and A-8; from Brar & Aziz (1978). Figure 5.4 shows that N-D flow represents 48% of the total pressure drop when well A-8 flows at 70.2 MMscfd from a reservoir with 67.5% porosity and permeability 5.3 md. N-D, however, represents 69% of the total pressure drop when well A-6 is 74 70.265 flowing at 9.8 MMscfd from a reservoir with 8.3% porosity and permeability 3 md. This means that for one well flowing at a rate 7.1 times lower, the inertial effect contributes up to an additional 44% to the total pressure drop. Moreover, Non-Darcy flow represents 37% of the total pressure drop when well A-7 flows at 9.8 MMscfd from a reservoir with 8% porosity and permeability 13 md, but N-D represents 69% of the total pressure drop when well A-6 is flowing at 9.8 MMscfd from a reservoir with 8.3% porosity and permeability 3 md. These two wells have similar porosity, and they flowed at almost the same rate during the test, but N-D flow contributes less to the total pressure drop in well A-7 that has higher permeability. To evaluate actual field wells performance, additional multi-rate test data from various publications (Brar & Aziz, 1978; Lee & Wattenbarger, 1996; Lee, 1982; Energy Resources and Conservation Board, 1975) are included in Table 5.3 and Figure 5.5. Figure 5.5 shows exactly the same trend as the analytical model. Table 5.3 Flow rate and values of a and b for gas well with multi-flow tests. 1 Well Name Well A-1 (Brar & a 56.69 b 20.68 q1 (MMscfd) 0.248 q2 (MMscfd) 0.603 q3 (MMscfd) 0.864 q4 (MMscfd) 1.135 2 Well A-3 (Brar & 107.07 44.29 0.558 0.750 0.923 1.275 (Brar & 39.15 10.23 1.520 2.041 2.688 3.122 (Brar & 91.94 16.70 2.104 3.653 4.026 5.079 (Brar & 107.72 24.47 4.194 6.444 8.324 9.812 (Brar & 1158.69 68.79 8.584 9.879 12.867 (Brar 30.15 0.40 31.612 44.313 56.287 70.265 Aziz, 1978) Aziz, 1978) 3 Well A-4 Aziz, 1978) 4 Well A-5 Aziz, 1978) 5 Well A-6 Aziz, 1978) 6 Well A-7 Aziz, 1978) 7 Well A-8 & Aziz, 1978) 8 Example 7.1 (Lee & Wattenbarger, 1996) 7.75x104 5.00x103 4.288 9.265 15.552 20.177 9 Example 7.2 (Lee & 2.074x104 2.109x106 0.983 2.631 3.654 4.782 (Lee, 311700 17080 2.6 3.3 5.0 6.3 (Lee, 128300 19500 4.5 5.6 6.85 10.8 Example 3.1 (ERCB, 0.0625 0.00084 2.73 3.97 4.44 5.50 Wattenbarger, 1996) 10 Example 5.2 1982) 11 Example 5.3 1982) 12 1975) 75 F (Fraction of Pressure Drop Generated by Non-Darcy Flow) 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0.0 0.1 1 10 100 Gas Rate (MMscf/D) Figure 5.5 field data. 5.3 Well-A6 Well-A7 Well-A8 Well-A5 Well-A4 Well-A3 Well-A1 Example 7.1 Example 7.2 Example 5.2 Example 5.3 Example 3.1 Fraction of pressure drop generated by Non-Darcy flow for gas wells – Numerical Simulator Model A commercial numerical simulator with global and local N-D flow component was used to investigate Non-Darcy flow effect on gas recovery. The reservoir model has 26 radial grids and 110 vertical layers (Armenta, White, & Wojtanowicz, 2003) to assure adequate resolution for the near-well coning simulation. Reservoir parameters are constant throughout the model (porosity = 10%, permeability = 10 md, initial reservoir pressure = 2300 psia). The gas-water relative permeability curves are for a water-wet system reported from laboratory data (Cohen, 1989); Gas deviation factor (Dranchuck, 1974) and gas viscosity (Lee et al, 1966) were calculated using published correlations. Capillary pressure was neglected (set to zero), and relative permeability hysteresis was not considered (Table 5.4). Well performance was modeled using the Petalas and Aziz (1997) mechanistic model correlations (Schlumberger, 1998). Inertial coefficient, β, was calculated using Frederick and Grave’s (Computer Modelling Group Ltd, 2001) second 76 correlation (Equation 5.2). The well perforated 25% of the gas zone. The well is produced at a constant tubing head pressure of 300 psia. Figure 5.6 shows a sketch of the reservoir model. A sample data deck for IMEX reservoir model is contained in Appendix E. Well φ= 10% Sgr= 20% Pinitial= 2300 psia Swir= 30% S.G.gas=0.6 kr= 10 md 2500 ft 100 of 1 ft layers 25 ft 100 ft Gas 9 of 10 ft, and one 710 ft layers 800 ft Water 5000 ft Figure 5.6 Sketch illustrating the simulator model used to investigate N-D flow. Table 5.4 Gas and water properties used for the numerical simulator model Gas Deviation Factor and Viscosity Gas and Water Relative Permeability Press Z Visc 100 0.989 0.0122 300 0.967 0.0124 500 0.947 0.0126 700 0.927 0.0129 900 0.908 0.0133 1100 0.891 0.0137 1300 0.876 0.0141 1500 0.863 0.0146 1700 0.853 0.0151 1900 0.845 0.0157 2100 0.840 0.0163 2300 0.837 0.0167 2500 0.837 0.0177 2700 0.839 0.0184 3200 0.844 0.0202 77 Sg 0.00 0.10 0.20 0.30 0.40 0.50 0.60 0.70 Krg 0.000 0.000 0.020 0.030 0.081 0.183 0.325 0.900 Pc 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Sw 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1.0 Krw 0.000 0.035 0.076 0.126 0.193 0.288 0.422 1.000 Pc 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Frederick and Grave’s second correlation: β = 2.11*1010 ……..…………………(5.2) (k g ) 1.55 (φS g ) 1.0 Where β= inertia coefficient; kg= reservoir effective permeability to gas; φ= porosity, and Sg= gas saturation. 5.3.1 Volumetric Gas Reservoir Initially, the global N-D effect was simulated for a volumetric gas reservoir. Figures 5.7 and 5.8 are the forecast of gas rate and cumulative gas recovery versus time, respectively. 18 16 Gas Rate (MMscf/d) 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 7000 8000 9000 Time (Days) Without Non-Darcy Figure 5.7 reservoir. Including Non-Darcy Gas rate performance with and without N-D flow for a volumetric gas Figure 5.7 shows that at early time the gas rate is higher when N-D is ignored. After 1500 days, the situation reverses, and the gas rate becomes higher when N-D is included. At later times, gas rate is almost the same for both cases. The well life is slightly longer when N-D is included. This may result from N-D acting like a reservoir’s 78 choke restricting gas rate and delaying gas expansion. In other words, gas expansion happens faster when N-D is ignored. Figure 5.8 shows that the final recovery is not affected by the N-D. However, production time is longer, as was explained previously, when N-D is considered. 90 80 Gas Recovery (%) 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 7000 8000 9000 Time (Days) Without Non-Darcy Including Non-Darcy F (Fraction of Pressure Drop Generated by Non Darcy Flow) Figure 5.8 Cumulative gas recovery performance with and without N-D flow for a volumetric gas reservoir. 1 0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 1 10 100 Gas Rate (MMscf/D) Figure 5.9 Fraction of pressure drop generated by Non-Darcy flow for gas wells – simulator model. 79 The highest contribution of the Non-Darcy effect to the total pressure drop is 43%. It happens at the beginning of the gas production when the gas rate is 10.2 MMscfd (Figure 5.9). 5.3.2 Water Drive Gas Reservoir A gas reservoir with bottom water drive was considered in the analysis. Aquifer pore volume is 155 times greater than the gas pore volume. The analysis considered the N-D effect applied at the wellbore (typical for most reservoir simulators), distributed throughout the reservoir, and entirely disregarded. A sample data deck for IMEX reservoir model is included in Appendix E. 16 Gas Rate (MMscf/D) 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 0 500 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000 3500 4000 Time (days) Without N-D Setting N-D at the wellbore Including N-D through the reservoir Figure 5.10 Gas rate performances with N-D (distributed in the reservoir and assigned to the wellbore) and without N-D flow for a gas water-drive reservoir. Figure 5.10 shows the gas rate forecast for the three cases. At early times, all results are similar to the volumetric scenario. The well without N-D would produce for 3,663 days. The well with N-D distributed throughout the reservoir would stop producing after 1,882 days because it loads up with water. The well with N-D at the wellbore would 80 produce for 3,952 days. Note that for the cases when N-D is ignored or set at the wellbore, the gas rate pattern is exactly the same as for the volumetric gas reservoir. When N-D is at work throughout the reservoir, early liquid loading occurs. In short, setting N-D only at the wellbore would seriously overestimate well performance. 70 Gas Recovery (%) 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 0 500 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000 3500 4000 Time (Days) Without N-D Setting N-D at the wellbore Including N-D throughout the reservoir Figure 5.11 Gas recovery performances with N-D (distributed in the reservoir and assigned to the wellbore) and without N-D flow for a gas water-drive reservoir. Figure 5.11 shows gas recovery versus time. The final gas recovery is almost the same (61%) when N-D is ignored or set at the wellbore. However, when N-D is included throughout the reservoir, the recovery is significantly lower (42.9%), caused by early liquid loading of the well. The recovery reduction is 42.2%. Figure 5.12 shows water rate versus time. Water production is always higher when N-D is ignored or set at the wellbore than when it is considered globally in the reservoir. All three wells stopped production due to water loading. However, the well with N-D distributed in the reservoir is killed early with a lower water rate. 81 200 180 Water Rate (stb/d) 160 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 Time (Days) Without N-D Setting N-D at the wellbore Including N-D throughout the reservoir Figure 5.12 Water rate performances with ND (distributed in the reservoir and assigned to the wellbore) and without N-D flow for a gas water-drive reservoir. To explain the global N-D effect on well liquid loading, behavior of the flowing bottom hole pressure (FBHP) and pressure in the first grid of the simulator model (pressure before the completion) at the top of well completion were analyzed. Bottom Hole Flowing Pressure (psia) 1400 1200 1000 800 600 400 200 0 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 Time (Days) Without N-D Setting N-D at the wellbore Including N-D throughout the reservoir Figure 5.13 Flowing bottom hole pressure performances with N-D (distributed in the reservoir and assigned to the wellbore) and without N-D flow. 82 Figure 5.13 shows that FBHP is always higher when N-D is ignored, which makes physical sense. Also, FBHP is the same for N-D at the wellbore or distributed throughout the reservoir. After 1,882 days, however, the well with global N-D stops producing while the other wells continue with increasing flowing pressure due water Flowing Pressure at the Sandface at the Top of Completion (psia) inflow. 1800 1600 1400 1200 1000 800 600 400 200 0 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 Time (Days) Without N-D Setting N-D at the wellbore Including N-D throughout the reservoir Figure 5.14 Pressure performances in the first simulator grid (before completion) with ND (distributed in the reservoir and assigned to the wellbore) and without N-D flow. Analysis of pressure in the first grid of the simulator model (Figure 5.14) explains the reason for early termination of production in the gas well with global N-D. Pressure in the first simulator grid is the pressure before the well completion on the reservoir side. For the same completion length and gas flow rate, pressure at the first grid of the simulator should always be lower when N-D is considered. For this example, when N-D is considered globally, pressure at the first grid of the simulator is always lower than the non N-D scenario. This is in good agreement with the physical principle explained 83 previously. On the other hand, when N-D is set at the wellbore, pressure at the first grid of the simulator is always higher than the non N-D scenario. This is contrary to the physical principle explained previously. In short, setting N-D at the wellbore makes the reservoir gain pressure instead of losing it at the sandface. 2400 Pressure (psi) 2200 2000 1800 1600 1400 1200 0.01 0.1 1 10 100 1000 10000 Distance From the Wellbore (ft) Without N-D Setting N-D at the wellbore Including N-D trough the reservoir Figure 5.15 Pressure distribution on the radial direction at the lower completion layer after 126 days of production (Wells produced at constant gas rate of 8.0 MMSCFD) with ND (distributed in the reservoir and assigned to the wellbore) and without N-D flow. Figure 5.15 shows the pressure distribution on the radial direction at the lower completion layer after 126 days of constant gas rate (8.00 MMSCFD) when N-D is considered globally, assigned only at the wellbore, and without considering N-D. The effect of N-D extends 6 feet from the wellbore. The main effect, however, happens two feet around the wellbore. Again, pressure distribution around the wellbore is higher when N-D is assigned to the wellbore than the case when N-D is ignored showing the erroneous physical behavior for this condition (N-D set at the wellbore). Pressure at 0.01 ft from the wellbore is 500 psi lower when N-D is considered throughout the reservoir 84 than when N-D is ignored. This extra pressure drop in the reservoir makes gas wells extremely vulnerable to water loading reducing final gas recovery. From the previous analysis, it is evident that setting N-D at the wellbore to simulate gas wells’ performance does not properly represent the N-D flow physical principle. N-D should be distributed throughout the reservoir. 5.4 Results and Discussion The results of this study emphasize the important physical principle of considering N-D globally–throughout the reservoir. Not only gas rate but also porosity and permeability control N-D contribution to the total pressure drop in gas wells. Contribution of the pressure drop generated by N-D to the total pressure drop increases when gas rate is increased. Increasing gas rate increases interstitial gas velocity and the inertial component associated. Reducing porosity increases contribution of N-D to the total pressure drop. Reduction on porosity reduces rock-space for the gas to flow increasing, again, gas interstitial velocity. Reducing permeability increases contribution of N-D to the total pressure drop, also. Reduction on permeability reduces gas flow ability. At the same gas rate, gas interstitial velocity increases when permeability is reduced. The well-accepted assumption in petroleum engineering that assigning N-D at the wellbore represents this phenomenon is not precise. N-D should be considered globally throughout the gas reservoir to really evaluate its effect on gas rate and gas recovery. N-D effect could reduce gas recovery in water-drive gas reservoirs because it makes the well more sensitive to water loading. Liquid saturation may also increase the N-D effect (Geertsman, 1974; Evan et al., 1987; Tiss & Evans, 1989; Frederick & 85 Graves, 1994; Lombard et al., 1999). Thus, around the wellbore, the combined effect of high water saturation due to water coning and N-D could negatively affect gas rate and gas recovery. Completion length plays a role on the N-D flow effect. There is no analytical equation describing this interaction. Some authors (Dake, 1978; Golan, 1991) recommend changing h for hper in the second terms of the right side of Equation D-3 (Appendix D) to include the partial penetration effect in the N-D component of this equation. For the field data used in this research, the author could not include the completion length effect in the analysis. N-D effect significantly influences gas production performance in fractured well (Fligelman et al., 1989; Rangel-German, and Samaniego, 2000; Umnuayponwiwat et al., 2000). Flower et al. (2003) proved that gas rate increased 20% when N-D in the fracture is reduced. Alvarez et al (2002) explained that N-D should be considered in pressure transient analysis of hydraulic fractured gas wells. Ignoring N-D for the pressure analysis resulted on miscalculation of formation permeability, fracture conductivity and length. From this study it is possible to conclude as follows: • The Non-Darcy flow effect is important in low-rate gas wells producing from low-porosity, low-permeability gas reservoirs. • Setting the N-D flow component at the wellbore does not make reservoir simulators represent correctly the N-D flow effect in gas wells. N-D flow should be considered globally to predict correctly the gas rate and recovery. • Cumulative gas recovery could reduce up to 42.2% when N-D flow effect is considered throughout the reservoir in gas reservoirs with bottom water drive. 86 CHAPTER 6 WELL COMPLETION LENGTH OPTIMIZATION IN GAS RESERVOIRS WITH BOTTOM WATER There is a dilemma in the petroleum industry about the completion length to solve water production in gas wells. A normal practice is to make a short completion at the top of the gas zone to delay water coning/production. This short completion, however, reduces gas inflow and delays gas recovery. Recently, some researchers (McMullan & Bassiouni, 2000; Armenta, White, and Wojtanowicz, 2003) have proposed that a long completion should be used to increase gas rates and accelerate gas recovery. The previous analysis, however, did not include the economic implications of completions length in gas reservoir. The objective of this study is to examine the factors that control the value of water-drive gas wells and propose methods to analyze and optimize completion strategy. Due to the size of the experimental matrix (20,736 results), one committee member (Dr. Christopher D. White) helped the author building the statistical model and writing the computer code to run the statistical model. 6.1 Problem Statement The dependence of recovery on aquifer strength, reservoir properties and completion properties is complex. Although water influx traps gas, it sustains reservoir pressure; although limited completion lengths suppress coning, they lower well productivity. These tradeoffs can be assessed using numerical simulation and discounting to account for the desirability of higher gas rates. 87 6.2 Study Approach A base model for a single well is specified. Many of the properties of this model are varied over physically reasonable ranges to determine the ranges of relevant reservoir responses including ultimate cumulative gas production, maximum gas rate, and discounted net revenue. The responses are examined using analysis of variance, response surface models, and optimization. 6.2.1 Reservoir Simulation Model Numerical reservoir simulators can predict the behavior of complex reservoir-well systems even if the governing partial differential equations are nonlinear. The same model explained in section 5.3 was used for the study. The model chosen for this study used 26 cylinders in the radial direction by 110 layers in the vertical direction (McMullan & Bassiouni, 2000), providing adequate resolution of near-well coning behavior. The radius of the gas zone is 2,500 ft, and its thickness is 100 ft. The gas zone has 100 grids in the vertical direction (one foot per grid). The radius of the water zone is 5,000 ft, and its thickness is varied from 110 to 1410 ft. The water zone has 10 grids in the vertical direction. Nine of them have a thickness of 10 ft and the bottom grid is varied to represent the aquifer. The aquifer is represented by setting porosity to one for the outermost gridblocks and the thickness of the lowermost gridblocks are varied from 110 to 1410 ft to adjust aquifer volume. The gas-water relative permeability curves are for a water-wet system (Table 5.4) reported from laboratory data (Cohen, 1989). The gas deviation factor (Dranchuck et al., 1974) and gas viscosity (Lee et al., 1966) were calculated using published correlations (Table 5.4). Capillary pressure is neglected (set to zero), and relative permeability hysteresis is not considered. The well performance was modeled using the Petalas and Aziz (1997) mechanistic model correlations 88 (Schlumberger, 1998). Appendix F includes a sample data deck for the Eclipse reservoir model. Reservoir properties and economic parameter are the factors varied for the study. 6.2.1.1 Factors Considered Factors are the parameters that are varied. Five reservoir parameters (initial pressure, horizontal permeability, permeability anisotropy, aquifer size, and completion length) and three economic factors (gas price, water disposal cost, and discount rate) are selected for consideration; each factor is assigned a plausible range. Table 6.1 shows the factors and the range values for each one. Factor descriptions. Description Units # Levels Table 6.1 pi Initial Pressure psia 3 kh Horizontal Permeability md 3 1 10 100 VAD Aquifer Size ~ 4 100 400 800 1500 kzD Anisotropy Ration ~ 4 0.1 0.3 0.5 Cg Gas price $/Mscf 3 1 3.5 6 2 Factor Type Symbol Reservoir variables Economic variables Controllable Levels 1 2 3 4 1500 2300 3000 1 Cw Water cost $/bbl 3 0.5 1.25 d Discount rate annual 4 0 0.06 0.12 0.18 hpD Completion Fraction 0.2 0.5 ~ 4 0.8 1 Factors can be classified by our knowledge and our ability to change them. Controllable factors can be varied by process implementers. Observable factors can be measured relatively accurately, but cannot be controlled. Uncertain factors can neither be measured accurately nor controlled (White & Royer, 2003). For this study, there are four uncontrollable, uncertain reservoir parameters. Initial pressure (pi) affects the original gas in place and the absolute open flow potential of the well (Lee & Wattenbarger, 1996); it has a less important effect on density contrast. Horizontal permeability (kh) affects flow potential and influences coning behavior by altering the near-well pressure distribution 89 (Kabir, 1983). Permeability anisotropy (kzD = kz/kh) affects coning and crossflow behavior Battle & Roberts, 1996), and aquifer size (VAD = W/G) determines the amount of reservoir energy that can be provided by water drive. There are three economic parameters. Gas price (Cg) and water disposal cost (Cw) are used to compute the revenues and costs associated directly with production. No capital costs or other operating costs are considered in this analysis. The discount rate (d) is used to compute the present value of the gas production less the water disposal costs. The economic parameters may be difficult to predict, especially gas price. Therefore, it is reasonable to consider them uncertain and uncontrollable. The only controllable factor is the completion length (hpD = hp/h). Completion length should be chosen to minimize water production with acceptable reductions in flow potential. The completion is assumed to occur over a continuous interval beginning at the top of the reservoir. The completion length is optimized over the ranges of the uncertain and/or uncontrollable factors. 6.2.1.2 Responses Considered Decisions are based on responses obtained by measurement or modeling. Reservoir studies examine responses that affect project values, e.g., time of water breakthrough, cumulative recovery (White & Royer, 2003). Three responses were examined in this study. The ultimate cumulative gas production (GpU) is the total undiscounted value of a gas stream, whereas the peak rate (qg,max) is positively correlated to the discounted value. Discounted cash flow (N) measures the net present value of the production stream. The net present value ignores investments and all operating costs except for water handling. 90 6.2.2 Statistical Methods 6.2.2.1 Experimental Design Experimental design methods have found broad application in many disciplines. In fact, we may view experimentation as part of the scientific process and as one of the ways to learn about how systems or process work. Generally, we learn through a series of activities in which we make conjecture about a process, perform experiments to generate data from the process, and then use the information from the experiment to establish new conjectures, which lead to new experiments, and so on (Montgomery, 1997). The purpose of experimental design is to select experiments to provide unambiguous, accurate estimates of factor effects with a reasonable number of experiments. In the context of this study, an “experiment” is a numerical simulation. This correspondence has been widely used, although there are relevant differences between physical experiments (with nonrepeatable errors) and numerical simulations (Sacks et al., 1989). Because the simulations in this study are relatively inexpensive, a full multilevel factorial is used (Table 6.1). For the five reservoir and completion parameters, this design requires 576 simulations. The three economic factors increase the number of results for N 36-fold, to 20,736. 6.2.2.2 Statistical Analyses Although the number of factors is moderately large (8) and the number of economic responses to be considered is very large (20,736), this amount of data can be manipulated using public-domain statistical program ( R ) and commercial spreadsheet (Microsoft excel) software. 91 6.2.2.3 Linear Regression Models Regression analysis is a statistical technique for investigating and modeling the relationship between variables (Montgomery & Peck, 1982). The first step in the statistical analysis of the responses was to formulate a linear model without interaction among them. This linear model is described by the equation: r y = β 0 + ∑ β i xi ……………………………………………………(6.1) i =1 Where there are r=8 factors xi with coefficients βI; β0 is the intercept. This equation is often called a “response surface model” (RSM), or simply a “response model,” in the context of experimental design. This equation (Eqn. 6.1) was used as the basis for analysis of variance. Models with interactions are appropriate when the importance of a factor varies with the values of other factors (Myers & Montgomery, 2002); for example, the importance of aquifer size commonly depends on the permeability (White & Royer, 2003). A linear regression model with interaction was developed for the responses. The interaction terms in a linear model have the form βijxixj (Eqn. 6.1) where βij is the interaction coefficient between two factors, and xi, xj are factors. The coefficients of linear models are commonly computed using linear least squares method. The last-squares criterion is a minimization of the sum of the squared differences between the observed responses, and the predicted responses for each fixed value of the factor (Jensen et al., 2000). Two additional complications were encountered when the linear model with interactions was built. First, the response variance was not uniform. For example, a subsample of large aquifer will have a larger volume variance than a subsample of 92 smaller aquifer. Such heteroscedacity was eliminated with a variance-stabilizing BoxCox transform (Box & Cox, 1964). Second, the responses were not linear with respect to the factors (or independent variables). This tended to increase estimation error, and could partly treated using a Box-Tidwell transform on each of the independent variables (Box & Tidwell, 1962). The resulting form (for a first-order model in the transformed parameters) is r y a = β 0 '+ ∑ β i ' x ib ………………………………………..(6.2) i =1 Where a is the Box-Cox power and the bi are the Box-Tidwell powers for each factor. One must have a large number of experiments to estimate these parameters accurately. The Box-Cox and Box-Tidwell transforms create a more accurate model that better conforms to the assumptions of least-squares estimates. In general, untransformed equations are more useful for discussion and transformed equations are better for modeling. 6.2.2.4 Analysis of Variance Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to discern which factors are contributing to the variability of a response. The idea of an analysis of variance is to express a measure of the total variation of a set of data as a sum of terms, which can be attributed to specific source, or cause, of variation. ANOVA is an excellent procedure to use to screen variables and is a standard method for analysis of factorial designs (Myers & Montgomery, 2002). 6.2.2.5 Monte Carlo Simulation Monte Carlo is a powerful numerical technique for using and characterizing random variables in computer programs. If we know the cumulative distribution function 93 of the variables, the method enables us to examine the effects of randomness upon the predicted outcome of numerical models (Jensen et al., 2000). Monte Carlo simulation (MCS) is simply drawing randomly from the distribution functions for input functions to estimate an output via a transfer function; it has been widely used in reservoir simulation (Damsleth et. al., 1992). Although MCS is simple to implement, it is burdensomely expensive when the transfer function is difficult to evaluate, which is the case for reservoir simulations. (Typical MCS samples are much large than the 576-point simulation model sample in this study). Therefore, engineers may use a response surface model as a proxy for the reservoir simulation when performing MCS (Damsleth et. al., 1992; White et. al., 2001). 6.2.3 Optimization Optimization maximizes or minimizes an objective function subject to constraints. Usually, the factors not being optimized are known (or specified) so that the optimization can be carried out using standard gradient methods (Dejean & Blanc, 1999; Manceau et. al, 2001). If uncontrollable factors are uncertain, other approaches can be used to optimize, including seeking the maximum expected value of the objective function over the distributions of uncertain factors (Aanonsen et. al., 1995; White & Royer, 2003). Because the objective function is nonlinear, the optimum for the expected value of the factors does not optimize the expected value of the objective function. 6.2.4 Workflow The set of simulation models is specified using a factorial design. Simulation models are constructed for all design points, making frequent use of “INCLUDE” capabilities in simulator. A consistent naming convention ensures that all simulation runs can be uniquely associated with a particular design point (or factor combination). All 94 simulation results can then be parsed to extract production profiles and other relevant responses (Roman, 1999). The responses are scaled and formatted in the spreadsheet before being exported to a statistics package (R Core Team, 2000). Response models can be fit, significant terms identified, and appropriate transforms can be applied. The resulting linear models are then exported back to the spreadsheet for Monte Carlo simulation and optimization. Figure 6.1 shows a flow diagram for the workflow used for this study. 576 RSM files Result files Reservoir Simulator (Eclipse) Calculations: •Fit response models •Identify significant terms •Apply transforms Spreadsheet (Excel) Spreadsheet (Excel) Production profile Calculations: •Net Present Value Statistics Package (R) •Cumulative recovery Simulator Models 20,736 results Figure 6.1 Flow diagram for the workflow used for the study. 95 Calculations: •Monte Carlo Simulation •Optimization 6.3 Results and Discussion 6.3.1 Linear Models Equations 6.3, 6.4, and 6.5 show the linear regression models for the ultimate cumulative gas production (GpU), peak gas rate (qg,max), and discounted cash flow (N) without interactions. G pu = −8.98 E 6 + 2.03E 4 * pi + 1.15 E 3 * h pD + 1.04 E 5 * k h − 6.28 E 3 * V AD − 6.45 E 4 * k zD ………………………...(6.3) q g , max = −12750 + 8.425 * pi + 48.94 * h pD + 1670 * k h + 0.0269 * V AD + 0.6023 * k zD …………………………….(6.4) N = −83.54 + 0.0449 * pi + 0.1049 * h pD + 0.5265 * k h − 0.0112 * V AD − 0.157 * k zD + 0.2305 * C g − 0.867 * Cw − 0.0322 * d ...(6.5) GpU increases with initial reservoir pressure, length of completion and horizontal permeability. GpU decreases with aquifer size and permeability anisotropy (Eqn. 6.3). The maximum rate qg,max increases with the five reservoir factors included for the study (Eqn. 6.4). Finally, N increases with initial reservoir pressure, length of completion, horizontal permeability, and gas price. N decreases with aquifer size, permeability anisotropy, water disposal cost, and discount rate (Eqn. 6.5). The precision of the liner models without interactions is poor; R2 values average around 0.5 or 0.6. This is not accurate enough for optimization, and improved models with interactions among the factors are needed. A more accurate response model is needed to understand response variability and to optimize. An accurate model for net present value is built by (1) applying a Box-Cox transform to N, (2) computing maximum likelihood estimates of the Box-Tidwell transforms (Box & Cox, 1964; Box & Tidwell, 1962), (3) scaling all factors to cover a unit range, and (4) fitting a model with two-term interactions and quadratic terms. 96 Eqns. 6.6 to 6.12 (Table 6.2) show the relationship among the transformed to untransformed factors where the superscript t denotes the transformed, scaled factor values. pit = pi0.7013 − 168.90 ………………………………………………………(6.6) 105.7 k ht = k h−0.3362 − 0.2125 ………………………………………………………(6.7) 0.787 t k zD = 0.024 k zD − 1.0585 ………………………………………………………(6.8) 0.062 t VAD = −0.519 VAD − 0.0224 …………………………………………………….(6.9) 0.069 C gt = Cg − 1 5 ………………………………………………………………(6.10) Cwt = Cw − 0.5 ……………………………………………………………(6.11) 1.5 dt = d 0.5135 ………………………………………………………………(6.12) 0.415 Factor descriptions including Box-Tidwell power coefficients Factor Type Symbol Reservoir variables Economic variables Controllable # Levels Table 6.2 Levels 1 2 3 4 BoxTidwell Power Description Units pi Initial Pressure psia 3 kh Horizontal Permeability md 3 1 10 100 VAD Aquifer Size ~ 4 100 400 800 1500 -0.52 kzD Anisotropy Ration ~ 4 0.1 0.3 0.5 0.02 Cg Gas price $/Mscf 3 1 3.5 6 1500 2300 3000 0.70 -0.34 1 1.00 Cw Water cost $/bbl 3 0.5 1.25 2 1.00 d Discount rate annual 4 0 0.06 0.12 0.18 0.51 hpD Completion Fraction 0.2 0.5 1.39 ~ 4 97 0.8 1 Equation 6.13 shows the transformed (with Box-Cox and Box-Tidwell transforms) linear regression model with interactions. t t + 0.105 *V AD + 1.25 * C gt − 0.018 * C wt − 0.023 * d t − ... N t = 1.820 + 0.463 * p it − 0.07 * k ht − 0.072 * k zD t t − 0.065 * h tpD − 0.159( p it ) 2 − 0.184(k ht ) 2 − 0.03(k zD ) 2 − 0.006(V AD ) 2 − 0.471(C gt ) 2 + 0.0001(C wt ) 2 − ... t t − 0.095(d t ) 2 − 0.02(h tpD ) 2 + 0.142( p it * k ht ) + 0.02( p it * k zD ) + 0.016( p it *V AD ) + 0.14( p it * C gt ) − ... t t − 0.005( p it + C wt ) − 0.132( p it * d t ) + 0.051( p it * h tpD ) − 0.127(k ht * k zD ) − 0.025(k ht *V AD ) − ... t t − 0.188(k ht * C gt ) + 0.012(k ht * C wt ) − 0.351(k ht * d t ) + 0.101(k ht * h tpD ) + 0.087(k zD *V AD ) − ... t t t t t − 0.024(k zD * C gt ) − 0.007(k zD * C wt ) + 0.054(k zD * d t ) − 0.015(k zD * h tpD ) + 0.014(V AD * C gt ) + ... t t t + 0.01(V AD * C wt ) − 0.106(V AD * d t ) − 0.01(V AD * h tpD ) + 0.013(C gt * C wt ) − 0.12(C gt * d t ) + ... + 0.032(C gt * h tpD ) + 0.007(C wt * d t ) − 0.006(C wt * h tpD ) + 0.138(d t * h tpD )............................................................(6.13) Due to the complexity of the model shown on Eqn. 6.13 (44 terms), it is difficult to discern the relationship between N and each one of the factors directly, as it was done for the model without interactions. The Box-Cox transform stabilizes the variance of the response and makes the response more nearly normally distributed (Box & Cox, 1964). The Box-Tidwell transforms maximize the linear correlations between each factor and the response independently (table 6.2). Box-Tidwell exponents greater than one amplify the effect of the factor, whereas values between zero and one damp the effect. A power near zero (e.g., for anisotropy ratio) should be set to zero and the logarithmic transform used (Box & Tidwell, 1962). Values less than zero imply a reciprocal relation between the factor and the response. The linear model with interactions is quite accurate; R2 > 0.98. 6.3.2 Sensitivities (ANOVA) Table 6.3 shows the results for the analysis of variance of the linear model with out interactions (GpU, qg,max, and N ). The importance of a factor is related to the absolute 98 value of its effect. The effect is the change in the response across the range of the factor, averaged across all levels of other factors. Factor Table 6.3 Linear sensitivity estimates for models without factors interactions. Effects of factors across entire range. GpU qg,max N BCF S.C. MMCF/day S.C. MM$ S.C. pi 30.49 *** 12.64 *** 0.399 *** *** kh 10.33 *** 16.53 kzD -5.81 *** 0.05 VAD -8.80 *** 0.04 S.C. or Significance Codes (ANOVA) 0.353 *** Pr(|t|)> Pr(|t|)<= Symbol -0.101 *** 0 0.001 *** -0.074 *** 0.001 0.01 ** Cg 0.713 *** 0.01 0.05 * Cw -0.009 ** 0.05 0.1 o d -0.330 *** 0.1 1 blank 0.070 *** hpD -0.09 3.92 *** *** For cumulative gas production, all effects are highly significant except for completion length, which has a relatively small effect. This weak effect implies that varying the completion interval has little effect on cumulative production. For maximum gas rate, all factors have significant effects except for permeability anisotropy. For net present value, all factors are significant. The effects of gas price, initial pressure, horizontal permeability, and discount rate dominate other factors; water disposal cost has a relatively small effect. All effects were computed over the ranges given in table 6.1. Table 6.4 shows the results for the analysis of variance of the response model with interactions. The transformed linear model has a large number of terms. ANOVA shows that 42 of the 44 terms are retained at the 90% level of significance (Eqn. 6.13). This is a relatively complex response surface. Commercial spreadsheet (Microsoft excel) was used to evaluate the model. 99 Table 6.4 Transformed, scaled model for the Box-Cox transform of net present value. -0.026 0.000 Max 0.027 0.582 hpD Term 2 pi -0.065 Coeff. -0.159 0.006 Std. Err. 0.004 -11.56 *** T S.C. -43.32 *** kh kzD VAD Cg Cw d hpD Term 1 Term 2 pi kh -0.184 -0.030 -0.006 -0.471 0.000 -0.095 -0.020 Coeff. 0.142 0.004 0.004 0.005 0.004 0.004 0.004 0.004 Std. Err. 0.002 -43.14 *** -8.16 *** -1.32 -130.59 *** -0.07 -23.10 *** -4.93 *** T S.C. 56.88 *** Term 1 S.C. or Significance Codes (ANOVA) Pr(|t|)> 0 0.001 0.01 0.05 0.1 Pr(|t|)<= 0.001 0.01 0.05 0.1 1 Symbol *** ** * O Blank Quadratic Terms -0.474 Residuals Median 3Q 1Q Two-TermInteractions Min Linear Terms Summary Statistics D.F. 2 R 2 R adj F Pr(>F) Residual 44 20692 0.9805 0.9804 2.36E+04 0 Coefficients for Transformed, Scaled Factors Factor Coeff. Std. Err. T S.C. (Intercept) 1.820 0.004 442.85 *** pi 0.463 0.005 90.21 *** kh -0.070 0.006 -12.07 *** kzD -0.072 0.005 -13.35 *** VAD 0.105 0.007 16.05 *** Cg 1.250 0.005 242.33 *** Cw -0.018 0.005 -3.46 *** d -0.023 0.005 -4.16 *** Regress 100 pi kzD 0.020 0.003 7.01 *** pi VAD 0.016 0.003 5.92 *** pi Cg 0.140 0.003 55.09 *** pi Cw -0.005 0.003 -2.15 * pi d -0.132 0.003 -47.95 *** pi hpD 0.051 0.003 18.81 *** kh kzD -0.127 0.003 -45.45 *** kh VAD -0.025 0.003 -9.40 *** kh Cg -0.188 0.002 -75.15 *** kh Cw 0.012 0.002 4.91 *** kh d -0.351 0.003 -129.65 *** kh hpD 0.101 0.003 37.81 *** kzD VAD 0.087 0.003 28.77 *** kzD Cg -0.024 0.003 -8.48 *** kzD Cw -0.007 0.003 -2.53 * kzD d 0.054 0.003 17.47 *** kzD hpD -0.015 0.003 -4.82 *** VAD Cg 0.014 0.003 5.03 *** VAD Cw 0.010 0.003 3.69 *** VAD d -0.106 0.003 -36.32 *** VAD hpD -0.010 0.003 -3.49 *** Cg Cw 0.013 0.003 4.98 *** Cg d -0.120 0.003 -43.27 *** Cg hpD 0.032 0.003 11.65 *** Cw d 0.007 0.003 2.46 * Cw hpD -0.006 0.003 -2.18 * d hpD 0.138 0.003 46.50 *** First, the model was transformed back to the original factors, correcting it for bias introduced by the back transform from the transformed response N0.19 to the original response N (Jensen et. al., 1987); this correction ranges from about 5 percent at N = 1 MM$ to less than ½ percent at N = 350 MM$ . Next, graphs of the interaction of N with respect to the factors were built. Finally, the graphs were analyzed to establish the response model behavior. Figures 6.2 to 6.5 show the response model graphs. The combination of transformations, interactions and a second-order model yields surfaces that are far from planar (factors not varied are set to their center point value). Visualization of these surfaces contributes to understanding of the governing factors. Highly nonlinear functions can be modeled because of the use of the Box-Cox and Box-Tidwell transforms. 180 160 140 120 100 N (MM$) 80 60 40 2550 20 2025 pi (psia) 1 1500 11 31 21 51 41 70 60 90 80 100 0 kh (md) Figure 6.2 Effects of permeability and initial reservoir pressure on net present value. 101 Horizontal permeability is most influential when it is low, and its effect is comparable to the initial pressure (Figure 6.2). 180 160 140 120 100 N (MM$) 80 60 40 76 20 48 hpD (percent) 1 20 11 31 21 51 41 70 60 90 80 100 0 kh (md) Figure 6.3 Effects of permeability and completion length on net present value. The effect of completion length appears small compared with horizontal permeability (figure 6.3), and the permeability effect is largest at low permeability. Completion length effect is statistically significant. Although small, the completion length effect is not negligible (table 6.4). 180 160 140 120 100 N (MM$) 80 60 40 76 20 48 1.5 2.5 20 hpD (percent) 1.0 Cg ($/MCF) 2.0 3.5 3.0 4.0 6.0 5.5 5.0 4.5 0 Figure 6.4 Effects of gas price and completion length on net present value. 102 Gas price has a larger effect than the completion length (figure 6.4). The effect of completion length is greater at high gas price; this is a two-term interaction supporting the interacting, transformed linear model form. 225 200 175 150 125 N (MM$) 100 75 50 25 5 Figure 6.5 0.162 0.108 d (fraction) 0.135 0.054 3 0.081 0 0.027 0 Cg ($/MCF) 1 Effects of discount rate and gas price on net present value. Finally, the economic factors have large effects (figure 6.5; note change in Naxis). 6.3.3 Monte Carlo Simulation Monte Carlo simulation reveals the overall distribution of a response, helps analyze sensitivities, and guides optimization (Damsleth et. al., 1992, White & Royer, 2003; White et. al., 2001). To perform Monte Carlo simulation, distributions on all uncertain factors must be specified. In this study, beta distributions were used for all factors (figure 6.6, table 6.5). Beta distributions (Berry, 1996) are simple to manipulate and interpret: as a and b increase, the distribution gets narrower, if a is larger than b the distribution peak shifts to 103 the left. The distributions are easily scaled to fit any range. In the illustrative figure (figure 6.6), the uniform distributions (both parameters equal to 1) are appropriate for the controllable variables, whereas distributions with a long positive tail (a>b) are well suited to approximating factors like permeability. The distributions used in this study are reasonable, but do not have any verifiable physical meaning. Selection of reasonable factor distributions is discussed in texts on Bayesian statistics (Berry, 1996). Table 6.5 Parameters for beta distributions of factors Factor pi Design Beta Dist kzD kzD VAD Cg Cw d hpD Minimum 1500 1 10 100 1 0.5 0 0.2 Maximum 3000 100 100 1500 6 2 0.18 1 a 1 2 1 4 10 20 20 1 b 1 5 1 4 10 20 20 1 6 (aβ,bβ)=(20,20 Probability Density 5 4 3 (aβ,bβ)=(5,2) 2 (aβ,bβ)=(4,4) (aβ,bβ)=(1,1) 1 0 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1 Scaled value of parameter Figure 6.6 Beta distributions used for the Monte Carlo simulation. Using these factor distributions, the distribution of net present value can be visualized (figure 6.7). Compared to the base case where hpD is allowed to vary randomly over its entire range, the case with low hpD has a peak at lower N and fewer high N 104 values. Similarly, high hpD is associated with higher N. This shows that, on average, higher hpD yields higher N. 0.018 0.016 full range hpD minimum hpD 0.014 Proportion 0.012 0.01 0.008 0.006 maximum hpD 0.004 0.002 0 0 50 100 150 200 250 Net present value (MM$) Figure 6.7 Monte Carlo simulation of the net present value. The effects of all factors can be examined by setting each of the factors in to their P10, P50, and P90 values while allowing the other factors to vary according to their distributions (table 6.6). Unlike the linear sensitivity analysis (earlier), the Monte Carlo sensitivity (MCS) method incorporates factor value uncertainty in to the analysis. Table 6.6 shows the results. Table 6.6 Monte Carlo sensitivity estimates. Variations and Effects on Net Present Value (MM$) Effects Factor P10 P50 P90 Linear Quad. pi 69.1 99.3 122.9 53.79 -6.69 kh 95.0 98.5 100.1 5.16 -1.89 VAD 104.1 97.2 93.2 -10.93 2.83 kzD 100.4 97.5 95.9 -4.51 1.39 0.56 Cg 74.4 97.6 121.4 47.00 Cw 98.3 98.0 97.6 -0.66 0.00 d 101.4 97.8 94.5 -6.86 0.26 hpD 93.8 98.1 102.0 8.27 -0.32 105 These results (table 6.6) bear out the importance of initial pressure and gas price. Compared with the linear sensitivity analysis, MCS estimates lower sensitivity of net present value to horizontal permeability. The difference is computed from the P90 to the P10 values, which excludes the extremely low permeability values for which the permeability sensitivity is greatest (figure 6.2). In general, MCS results differ from linear sensitivity analyses because unlikely values are down-weighted in MCS. The completion effect from the MCS appears relatively small (but it is the fourth most important factor). However, increasing the completion length from 28 (P10) to 92 (P90) percent of the total interval length increases the average net present value from 93.8 to 102 MM$, a substantial change (figure 6.8, table 6.6). 140 Net present value (MM$) 135 low d, high pi, kh, and VAD 130 125 120 115 optima 110 105 100 base case 95 90 20 40 60 80 100 Completion length (percent) Figure 6.8 Optimization of net present considering uncertainty in reservoir and economic factors (two cases). 106 6.3.4 Optimization Development teams seek to choose the optimum well configuration for the prevailing reservoir properties and operating conditions. Response models can be used for this optimization. One approach is to differentiate the response model for the objective function with respect to the controllable parameter, set it equal to zero, and solve for the controllable parameter (White & Royer, 2003). Here, the model for net present value (Eq. 6.13) is differentiated with respect to the completion length hpD, the differenciate equation set equal to zero, and then solved for hpD. Eqn. 6.14 shows the resulting correlation to maximize net present value for any combination of the other parameters. This correlation is not a function of completion length. This is a mathematical equation resulting from the statistical function derived for Net Present Value. t t h tpD ,opt = 1,294 p it + 2.550k ht − 0.372k zD − 0.254V AD + 0.803C gt − 0.150C wt + 3.481d t − 1.635 …….(6.14) Where the superscript t denotes the transformed, scaled factor values. The effects of these factors are difficult to interpret because of the Box-Tidwell powers (table 6.2), but the function can be to evaluate to aid understanding (Roman, 1999). The equations relating transformed to untransformed factors are given in item 6.3.1 (Eqns. 6.6 to 6.12). Several observations can be made from Eqn. 6.14: as the initial pressure, permeability anisotropy and water cost increase, the optimal interval is decreased (These factors have positive Box-Tidwell power coefficient and negative coefficient in Eq. 6.14). As the gas price and discount rate increase, motivating higher rates, the optimal interval 107 increases (both factors have positive Box-Tidwell power coefficient and positive coefficient in Eq. 6.14). Comparison among optimum completion length calculated using Eqn. 6.14 and fitting responses directly from the data was done, getting good agreement among them (figure 6.9). Optimal completion length (percent) 120 100 80 60 40 Using Eqn. (3) 20 Directly fit response surface 0 0 20 40 60 80 100 Horizonal permeability (md) Figure 6.9 6.4 Optimal completion length calculated from the transformed model and a response model computed from local optimization. Implications for Water-Drive Gas Wells The statistical and optimization analyses shed light on the general problem of gas completions in the presence of water drives. Aquifer size is the third most important factor after initial pressure and gas price (table 6.6). Furthermore, the optimal completion length was often the full interval, even in the presence of large aquifers and higher-thanaverage water costs (figure 6.9). The optimization from the response model (Eqn. 6.14) is evaluated by comparison with directly simulated results (Figure 6.9), confirming that the optimum completion 108 length is often the full interval (for 55 percent of the cases examined), and the average optimum length is 80% of the gas zone. The relative loss of net present value caused by sub-optimal completion length can be calculated as: L =1− N (h pd ) N ( h pD ,opt ) ……………………………………………………..(6.15) 0.25 Loss relative to optimized case, fraction of NPV kh 0.2 hpD 0.15 pi Cg VAD d 0.1 kzD 0.05 0 1 2 3 4 Factor Level Figure 6.10 Relative loss of net present values if completion length is not optimized. The loss ranges from about 2 to over 20 percent, and the average loss is 10 percent (figure 6.10). The greatest losses due to sub-optimal completion length are for low pressure, low completion length, and low permeability; losses also increase as the discount rate increases. The response models and conclusions from this study can be applied to other water-drive gas reservoirs in a general sense. However, the statistical models are valid only over the ranges considered and if the other well and reservoir parameters are similar. 109 CHAPTER 7 DOWNHOLE WATER SINK WELL COMPLETIONS IN GAS RESERVOIR WITH BOTTOM WATER Water production reduces gas recovery by shortening the well’s life. Water loads up the gas well, killing it when a lot of gas remains in the reservoir. Various concepts and techniques have been used to solve water-loading problems in gas wells (Chapter 2). Some of them are: pumping units, liquid diverters, gas lifts, concentric dual-tubing strings, plunger lifts, soap injection, Downhole Gas Water Separation (DGWS), and flow controllers. All the above-mentioned solutions for water production in gas wells work inside the wellbore. Downhole Water Sink (DWS) technology has been successfully proved to control water coning in oil wells with bottom water drive increasing oil production rate and oil recovery (Swisher & Wojtanowicz, 1995; Shirman & Wojtanowicz, 1997, and 1998; Wojtanowicz et al., 1999). DWS works outside the wellbore to solve water production. The objective of this study is to evaluate DWS performance for different gas reservoir conditions and to compare DWS wells to the conventional gas wells with no water control and with water control (using DGWS technology). 7.1 Alternative Design of DWS for Gas Wells The most-promising configuration of dual (DWS) completion to improve performances of gas wells was identified qualitatively using several technical considerations as follows. DWS has proved successful in oil wells for a few particular designs of dualcompletion. However, Armenta and Wojtanowicz (2002) proved that the mechanism of 110 water coning in gas wells was different than that in oil wells. Therefore, a specific design of DWS for gas wells was to be different than for oil wells. Three different possible configurations were evaluated: 7.1.1 • Dual completion without a packer; • Dual completion with a packer; • Dual completion with a packer and gravity gas-water separation. Dual Completion without Packer Figure 7.1 depicts the DWS configuration including two completions without a packer. Gas Water Water Figure 7.1 Dual completion without packer. For this configuration, one completion is located at the top of the gas zone. Another is located in the water zone. Gas is produced from the top completion and water 111 from the bottom completion. A pump is located below the lower completion to drain the water zone and inject the water into a lower disposal zone. This pump generates an inverse gas cone. Also, the bottom hole pressure at the gas and water completion is the same. This configuration gives partial control over the water coning, although some water is still produced with the gas. The control efficiency, however, would be reduced with time because (as the gas-water contact moved upward) the amount of water produced from the top completion would increase and eventually kill the gas production. The solution here would be a bigger water pump. However, higher pump rate means the bottom-hole pressure is reduced with time while the amount of water produced from the top completion increases at the same time. This combination makes the well very sensitive to liquid loading. In short, this configuration could kill the well early. So, it would be better to have the two completions isolated to control the vertical movement of gas-water contact outside the well. 7.1.2 Dual Completion with Packer Figure 7.2 depicts the DWS configuration with two completions separated with a packer. The objective is to isolate the bottomhole pressure for the two completions. Isolating the bottomhole pressure would allow the pump rate to increase when the gaswater contact moves up without making the well too sensitive to water loading. Eventually, some water would be produced to the surface from the top completion at later times. This configuration allows for better control of water coning in gas wells with time because it allows two different values of the bottom hole flowing pressures. The top completion could keep producing gas longer with a small amount of water or even water112 free. However, the big disadvantage of this configuration is that some gas could be coned down to the lower completion. As the gas could not escape, it would create a high backpressure below the packer reducing the effectiveness of the system. Therefore, a “venting” system for the gas inflowing the bottom completion is needed to maintain control of water coning. Gas Water Water Figure 7.2 Dual completion with packer. 7.1.3 Dual Completion with a Packer and Gravity Gas-Water Separation Figure 7.3 shows the DWS configuration of two completions with a packer and gas-water separation at the bottom of the well. For this configuration, the two completions are separated only with the packer. This means that the bottom completion section begins close to the end of the top completion section. The top completion is produced through the annulus between the 113 tubing and the production casing. Also, water with some gas inflows the bottom completion due to the inverse gas coning. The production strategy ensures using a very long top completion ,producing water-free gas for most of the time. As water and gas separate in the well below the packer, gas is produced at the surface, and the water is injected into a disposal zone. Gas Water Water Figure 7.3 Dual completion with a packer and gravity gas-water separation. This configuration would control the water cone ascent outside the well and maximize the gas production rate at the top completion with no water loading. The gas production would be maximized due to the longer top completion and the extra gas production from the bottom completion – thus accelerating gas recovery. The disadvantage of this configuration is its complexity. However, the design could always be 114 made simple if the water from the bottom completion was lifted to the surface with the small amount of gas. From this qualitative analysis the author selected this design (dual completion with a packer and gravity gas-water separation) as the best configuration of DWS for gas wells. 7.2 Comparison of Conventional Wells and DWS Wells 7.2.1 Reservoir Simulator Model Numerical reservoir simulators can predict the behavior of complex reservoir-well systems even if the governing partial differential equations are nonlinear. This method was chosen for this study for several reasons. • Water production in gas reservoirs is a complex problem. • Water-drive gas reservoirs have two flowing phases, and it is difficult to analyze this behavior analytically. Actually, there is no analytical model for water coning in gas wells. • The gas-water contact location is dynamic, further complicating analysis. • Modern reservoir simulators (Schlumberger, 1997) integrate reservoir inflow and tubing outflow models, which is a vital component of gas well performance prediction (Lee & Wattenbarger, 1996). A comparison of gas recovery for conventional and DWS wells was performed using a gas reservoir model shown in Figure 7.4. The “layer cake-type” model consists of a gas reservoir on the top of an aquifer (McMullan & Bassiouni, 2000). The radius of the gas zone is 2,500 ft, and its thickness is 100 ft. The gas zone has 100 grids in the vertical direction (one foot per grid). The radius of the water zone is 5,000 ft, and its thickness is 800 ft. The water zone has 10 grids in the vertical direction. Nine of them have a 115 thickness of 10 ft and the bottom grid is 710 ft thick. The gas-water relative permeability curves are for a water-wet system (Table 5.4) reported from laboratory data (Cohen, 1989). The gas deviation factor (Dranchuck et al., 1974) and gas viscosity (Lee et al., 1966) were calculated using published correlations (Table 5.4). Capillary pressure is neglected (set to zero), and relative permeability hysteresis is not considered. The well performance was modeled using the Petalas and Aziz (1997) mechanistic model correlations (Schlumberger, 1998). Appendix F includes a sample data deck for the Eclipse reservoir model. Well, rw= 3.3 in Top: 5000 ft 100 layers 1 ft thick hp 100 ft Gas (G) 9 layers 1 ft thick, and one layer 710 ft thick. 800 ft Water (W) 5000 ft Figure 7.4 Simulation model of gas reservoir for DWS evaluation. 116 7.2.2 Reservoir Parameters Selection Vertical permeability and aquifer size were selected to create a well-reservoir system with severe water problems. Vertical permeability increases water coning in gas wells; the higher the vertical permeability is, the more severe the coning becomes (Beattle & Roberts,1996; Armenta & Wojtanowicz, 2002). A reasonable assumption in petroleum engineering is that vertical permeability is ten-fold smaller than horizontal permeability. To create a scenario of severe water coning, vertical permeability was assumed to be fifty percent of horizontal. Textbook models of water inflow for material balance computations assume that the amount of water encroachment into the reservoir is related to the aquifer size (Craft & Hawkins, 1991). (For example, van Everdinger and Hurst used the term B’ representing the volume of aquifer. The Fetkovich model considers a factor called Wei defined as the initial encroachable water in place at the initial pressure.) For this study, we assumed that the pore volume of the aquifer is 968–fold greater than the gas pore volume a condition of strong bottom water drive. The inflow gas rate depends on reservoir permeability, so the rate of recovery is controlled by the gas rate. Three values of permeability, 1, 10, and 100 md, were selected for this study. Water loading kills gas wells causing reduced gas recovery; initial reservoir pressure plays an important role in this process. To investigate this effect, three different initial reservoir pressures were considered: low (subnormal), normal, and high (abnormal). Typically, reservoirs with an initial pressure gradient between 0.43 and 0.5 psi/ft are considered normally pressured (Lee & Wattenbarger, 1996). For this study, the initial reservoir pressure was calculated assuming 0.3 psi/ft, 0.46 psi/ft, and 0.6 psi/ft 117 values of pore pressure gradients for the subnormal, normal, and abnormal reservoir, respectively. Gas recovery from certain water-drive gas reservoirs may be very sensitive to gas production rate. If practical, the field should be produced at as high a rate as possible. This may result in a significant increase in gas reserves by lowering the abandonment pressure (Agarwal et al., 1965). Simulations for conventional wells were run at constant tubing head pressure (THP) of 300 psi at a maximum gas rate for the THP. The DWS well was modeled assuming two wells at the same location; the topcompletion well was produced the same way as the conventional well. The bottom-well completion was also run at constant THP (300 psi) until there was no more gas inflow to the bottom completion. Then, the bottom-completion well was produced at a constant maximum water rate. The length of the bottom completion for the DWS well was set at 30% the length of the top completion. 7.2.3 Conventional Wells Completion Length The potential benefit of long completion length to increase net present value in gas wells was identified in Chapter 6. This result agrees with detailed studies of completion length in gas reservoirs (McMullan & Bassiouni, 2000). For this study, the well completion length of conventional wells was selected to maximize gas recovery. The selection was needed to provide an unbiased comparison of the single – and dual – completed wells and to investigate if DWS gives some extra recovery beyond the maximum recovery of conventional wells. The effect of completion length on recovery was simulated for different initial reservoir pressure and permeability. 118 80 70 Gas Recovery (%) 60 50 40 30 20 10 k = 100 md 0 5 k = 10 md 10 30 50 k = 1 md 70 100 Fraction of Gas Zone Perforated (%) Figure 7.5 Gas recovery for different completion length in gas reservoirs with subnormal initial pressure. Figure 7.5 shows the results for a gas reservoir with subnormal initial reservoir. Gas recovery increases with permeability. Also, for each permeability value, the maximum recovery occurs when the gas zone is totally perforated. 70 Gas Recovery (%) 60 50 40 30 20 10 k =100 md 0 5 k =10 md 10 30 50 k =1 md 70 100 Fraction of Gas Zone Perforated (%) Figure 7.6 Gas recovery for different completion length in gas reservoirs with normal initial pressure. 119 70 Gas Recovery (%) 60 50 40 30 20 10 k =100 md 0 5 k =10 md 10 30 k =1 md 50 70 100 Fraction of Gas Zone Perforated (%) Figure 7.7 Gas recovery for different completion length in gas reservoirs with abnormal initial pressure. Figures 7.6 and 7.7 confirm the results for normal and abnormal reservoir pressure; maximum recovery is reached for a totally perforated gas well. For permeability 100 md, however, completion length effect is very small. Flowing Bottom Hole Pressure (psia) 2,200 2,000 1,800 1,600 1,400 1,200 1,000 800 600 400 200 0 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 Time (days) k= 1 md k= 10 md k= 100 md Figure 7.8 Flowing bottom hole pressure versus time (Normal initial pressure; 50% penetration). 120 The finding can be explained as follows. Gas recovery increases with permeability because of the larger gas rate and higher flowing bottom hole pressure. The well can tolerate higher water rates before loading up with liquid. Moreover, gas recovery is faster at high gas rates. 30,000 Gas Rate (Mscf/D) 25,000 20,000 15,000 10,000 5,000 0 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 Time (days) k= 1 md Figure 7.9 k= 10 md k= 100 md Gas rate versus time (Normal initial pressure; 50% penetration). Figures 7.8, and 7.9 support these observations. (They show the results for the normal initial reservoir pressure with 50% gas zone penetration.) They show the highest flowing pressure and gas rate for permeability 100 md. Overall, shorter completion length gives longer production time for conventional wells. From this study, it is possible to conclude that the highest gas recovery is when the gas zone is totally perforated, particularly for permeability 1 and 10 md. For permeability 100 md, gas recovery is almost insensitive to length of perforation. 121 7.2.4 Gas Recovery and Production Time Comparison Gas recovery and production time were calculated for the DWS wells and compared with the maximum gas recovery for the conventional wells calculated in the previous section. Total Production Time (Days) 60 Gas Recovery (%) 50 40 30 20 10 16000 14000 12000 10000 8000 6000 4000 2000 0 0 k = 1md, Low Pressure k= 1 md, Normal Pressure Conventional Well k = 1md, Low Pressure k= 1 md, High Pressure k=1md, Normal Pressure Conventional Well DWS Well k= 1 md, High Pressure DWS Well Figure 7.10 Gas recovery and total production time for conventional and DWS wells for different initial reservoir pressure and permeability 1 md. Figure 7.10 shows the results for a reservoir with permeability 1 md. Gas recovery is always higher for DWS compared with the conventional well. (At low initial reservoir pressure, gas recovery increases from 11% to 28%; at normal initial reservoir pressure, the increase is from 30% to 48%; at high reservoir pressure the increase is from 37% to 54%.) Furthermore, production time is always longer for DWS compared with the conventional well. In short, for tight reservoirs, DWS increases gas recovery by extending the well life. 122 80 8000 Total Production Time (Days) Gas Recovery (%) 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 k= 10 md; Low Pressure k= 10 md; Normal Pressure Conventional Well 7000 6000 5000 4000 3000 2000 1000 0 k= 10 md; High Pressure k= 10 md; Low Pressure DWS Well k=10md; Normal Pressure Conventional Well k= 10 md; High Pressure DWS Well Figure 7.11 Gas recovery and total production time for conventional and DWS wells for different initial reservoir pressure and permeability 10 md. Figure 7.11 shows similar results when the reservoir permeability is 10 md. Gas recovery with DWS is higher for all initial reservoir pressures. (At low initial reservoir pressure, gas recovery increases from 42% to 54%; at normal initial reservoir pressure, the increase is from 62% to 68%; at high reservoir pressure the increase is from 65% to 69%.) Production time is longer for DWS only for low initial reservoir pressure. It becomes shorter for the normal and high initial reservoir pressure. Thus, DWS increases gas recovery by extending the well life only for low-pressure reservoirs. In the normal and high-pressure reservoir, the DWS advantage is two-fold: it stimulates and accelerates the recovery. Figure 7.12 confirms these results for a reservoir with permeability 100 md. Gas recovery is always higher with DWS, but the improvement is very small. (At low initial reservoir pressure, gas recovery increases from 65% to 68%; at normal initial reservoir pressure, the increase is from 68% to 70%; at high reservoir pressure, the increase is from 123 69% to 70%.) Figure 7.12 also shows that production time is always slightly shorter with DWS, but the difference becomes almost insignificant. 4000 Total Production Time (Days) 80 Gas Recovery (%) 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 3500 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 k = 100 md, Low k=100 md, Pressure Normal Pressure Conventional Well k= 100 md, High Pressure k = 100 md, Low k=100 md, k= 100 md, High Pressure Normal Pressure Pressure DWS Well Conventional Well DWS Well Figure 7.12 Gas recovery and total production time for conventional and DWS wells for different initial reservoir pressure and permeability 100 md. 7.2.5 Reservoir Candidates for DWS Application It is evident from the previous study that gas recovery is higher for DWS wells than conventional wells. DWS increases gas recovery up to 160% for low-pressure (subnormal), low-permeability (1 md) gas reservoirs. The advantage, however, reduces to 10% for reservoirs with normal pressure and permeability 10 md, and it almost disappears when permeability is 100 md for any initial reservoir pressure. There is also some reduction of production time for permeabilities 10 and 100 md. Analysis of the production mechanism shows that DWS extends the well life by preventing early water loading of the well. Figures 7.13 and 7.14 support this conclusion. (These two figures are for subnormal initial reservoir pressure and permeability 1 md.) 124 3,000 Gas Rate (Mscf/D) 2,500 2,000 1,500 1,000 500 0 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 7000 Time (Days) DWS-Top Completion Conventional Figure 7.13 Gas rate history for conventional and DWS wells (Subnormal reservoir pressure and permeability 1 md). Bottom Flowing Pressure (psia) 800 700 600 500 400 300 200 100 0 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 7000 Time (Days) DWS-Top Completion Conventional Figure 7.14 Flowing bottom hole pressure history for conventional and DWS wells (Subnormal reservoir pressure and permeability 1 md). 125 Figure 7.13 shows gas rate versus time for the conventional and DWS well. The gas rate is always higher for DWS because the top completion produces almost water free most of the time. Figure 7.14 shows flowing bottom hole pressure of the wells. It shows that the bottom hole flowing pressure increase is slower for DWS than for conventional wells. In short, removing the water inflow to the top completion delays liquid loading of the well and elevates production rate. From this study, one could conclude that the best reservoir conditions for DWS would be low-permeability low-pressure gas reservoirs. With conventional technology, such reservoirs necessitate the use of a lifting technology (i.e. DGWS) to produce gas and water. 7.3 Comparison of DWS and DGWS The comparison is made for a gas reservoir with low permeability (1 md) and subnormal initial pressure. This is the worst-case scenario for conventional gas recovery, identified in the previous section, where there is a need for DWS or other (DGWS) technology. 7.3.1 DWS and DGWS Simulation Model The reservoir simulator model described in section 7.2.1 was also used in this study. DWS was simulated using two different wells located at the same place, but with different completion length and depth. The wells represented the top and bottom completions of DWS wells. Also, two cases of completion length were considered. In the first case, the top DWS completion totally penetrates the gas zone (100 ft), and the bottom completion is 30 feet long with the top located one foot below the bottom of the 126 top completion (DWS-1). (The same configuration was used to compare DWS with conventional wells.) In the second case, the top and bottom completion length are 70 and 60 feet, respectively (DWS-2). The two wells representing DWS completions produce simultaneously at constant THP (300 psia). It is assumed that the tubing of the bottom completion would only produce gas liberated from water (The Tubing Performance Relationship curves were built for zero water cut condition, only. Bottomhole flowing pressure for the bottom conditions is controlled by the THP and the gas friction losses, only. Both, gas and water, are produced from the reservoir and separated at the wellbore). When the bottom completion stops producing gas, the well is switched to produce at a constant and maximum water rate. DGWS was simulated using two different wells at the same place, too. The two wells had the same completion length and location. One well represents the situation until the well loads up with water. At this time the first well is shut down and the second well takes over. The second well models removal of water by downhole separator (DGWS), i.e. water free production of gas. Both wells are produced at constant THP (300 psia). It is assumed that the DGWS well produces gas free of water all the time. This is the best operational performance of DGWS. Two cases with different completion length were also considered; totally penetrated gas zone (DGWS-1) and 70% penetration (DGWS-2). Finally, the economic limit of 400Mscfd was set for the DGWS and DWS wells. Appendix F includes a sample data deck for the Eclipse reservoir model. 7.3.2 DWS vs. DGWS–Comparison Results Figures 7.15, 7.16, 7.17, and 7.18 summarize the results of the comparison between DWS and DGWS. 127 PTR [(Production Time Conventional, DWS, or DGWS) / (Production Time Conventional)] 45 40 Gas Recovery (%) 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Gas Zone Totally Perforated Conventional Gas Zone 70% Perforated DWS 7.0 6.0 5.0 4.0 3.0 2.0 1.0 0.0 DGWS Gas Zone Totally Perforated Conventional Gas Zone 70% Perforated DWS DGWS Figure 7.15 Gas recovery and Production Time Ratio (PTR) for conventional, DWS, and DGWS wells. Figure 7.15 shows gas recovery and Production Time Ratio (PTR) for the two cases of well completion. PTR = (Tp ) DWS / DGWS …………………………………………………………..(7-1) (Tp ) conventional Where: PTR = Production time ratio, (Tp)DWS = Production time for DWS wells, (Tp)DGWS = Production time for DGWS wells, (Tp)conventional = Production time for conventional wells. Figure 7.15 shows that DGWS gives the highest gas recovery (41.5%) when the gas zone is totally penetrated, and DWS gives the highest recovery (40.7%) when 70% of the gas zone is penetrated. Thus, maximum recovery for DWS and DGWS is almost the 128 same. Moreover, the PTR are 7.4 and 3.5 for DGWS and DWS, respectively. This means that the same recovery with DGWS takes (6.4/3.5 = 1.83) 1.83 times longer than that with DWS. 45 DWS-2 DGWS-1 40 Gas Recovery (%) 35 DGWS-2 30 DWS-1 25 20 15 10 5 Conventional 0 0 3000 6000 9000 12000 15000 18000 21000 Time (Days) DWS-2 Figure 7.16 DWS-1 DGWS-2 DGWS-1 Conventional Well-1 Gas recovery versus time for DWS, DGWS, and conventional wells. Figure 7.16 gives gas recovery versus time for the wells in all the cases. The DGWS-1 and DWS-2 designs give maximum final recoveries that are almost equal. However, DGWS-1 produces 50% longer than DWS-2. Thus, DWS-2 accelerates gas recovery. One additional observation for DWS is that reducing the length of the top completion and increasing the length for the bottom completion would increase gas recovery by 49% (from 27.3% to 40.7%). This is an important observation because it shows that completion lengths for DWS should be optimized (Armenta & Wojtanowicz, 2003). 129 3,000 Gas Rate (Mscf/d) 2,500 2,000 Conventional 1,500 DWS-2 Top 1,000 500 DWS-2 Bottom DGWS-1 0 0 3000 6000 9000 12000 15000 18000 21000 Time (Days) Conventional Well-1 Figure 7.17 DGWS-1 DWS-2 Top DWS-2 Bottom Gas rate history for DWS-2, DGWS-1, and conventional wells. 90 80 DWS-2 Bottom Water Rate (stb/d) 70 60 50 DGWS-1 40 30 20 Conventional DWS-2 Top 10 0 0 3000 6000 9000 12000 15000 18000 Time (Days) Conventional Well-1 DGWS-1 DWS-2 Top DWS-2 Bottom Figure 7.18 Water rate history for DWS-2, DGWS-1, and conventional wells. 130 21000 The rate decline plots in Figure 7.17 show that the gas rate for DWS-2 is always higher than that for DGWS-1. Also, the bottom completion of DWS-2 only produces gas during the initial 28% of the total production time (first 3405 days). Figure 7.18 is the water production history for the two highest gas recovery cases (DWS-2 and DGWS-1) and the conventional well. It shows that the bottom completion of DWS-2 has the highest water rate, and the top completion has the lowest. It means the DWS-2 produces the lowest amount of water to the surface because most of the water is injected using the bottom completion. 7.3.3 Discussion about the Packer for DWS Wells Bottom Hole Flowing Pressure (psia) 500 DWS-2 Top Conventional 400 DGWS-1 300 200 100 DWS-2 Bottom 0 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 12000 14000 16000 18000 20000 Time (Days) Conventional Well-1 DGWS-1 DWS-2 Top DWS-2 Bottom Figure 7.19 Bottom hole flowing pressure history for DWS-2, DGWS-1, and conventional wells. Figure 7.19 shows bottomhole pressure history for the two highest gas recovery cases (DWS-2 and DGWS-1) and the conventional well. It shows that bottom hole pressure for the conventional well increases rapidly due to the water production. Bottom 131 hole pressure for the DWS well is always deferent for the two completions. This difference is dramatically bigger when the top completion is set to produce at the maximum water rate releasing the THP restriction for the bottom completion (after 4000 days). This situation would not be possible without a packer. Therefore, as it was mentioned in section 7.1.3, the packer is needed to guarantee isolation between the two completions. This isolation is still possible when the two completions are one after the other (this is the case) giving a better control on the water coning. From this study, one can say that for the reservoir model used here, DGWS and DWS could give almost the same final gas recovery, but DWS production time is 35 % shorter than that for the DGWS well. DWS well, however, would produce little water at the surface from the top completion, but DGWS well would not lift any water. A packer between the two completions for the DWS wells is very important giving insulations between the completions and improving control on the water coning. 132 CHAPTER 8 DESIGN AND PRODUCTION OF DWS GAS WELL The potential benefit of Downhole Water Sink (DWS) technology in gas wells was previously identified in Chapter 7. The analysis, however, did not address operating conditions of DWS in gas reservoir. The objective of this study is to find out how to produce DWS wells in low productivity gas reservoirs with bottom water. The operational principle is maximum final gas recovery. Six factors control DWS operation: water rate from the bottom completion; top completion length; bottom completion length; distance between the bottom and the top completion; bottomhole flowing pressure at the bottom completion, and time to install DWS in gas wells (Note that the variable are not independent as flowing pressure relates to the completion length, and fluids rates for a given well/reservoir system). Figure 8.1 depicts four factors considered for the analysis. Separation between the completions Top completion length Water rate at the bottom completion Gas Water Bottom completion length Water Figure 8.1 Factors used to evaluate DWS performance. 133 The evaluation is done for a low productivity gas reservoir with reservoir pressure: 1500 psia (Subnormal); depth: 5000 ft; and for two different permeabilities: 1 and 10 md. The well (top completion) is produced at a constant tubing head pressure, 300 psia. The bottom completion is produced even at constant water rate or constant Bottom Hole Pressure (BHP). The gas-water contact is located at 5100 ft. An identical model to the one described in section 7.2.1 was used for the study. Table 5.4 shows the fluid properties, and Appendix F includes a sample data deck for the Eclipse reservoir model. 8.1 Effect of Top Completion Length Gas Recovery Factor (%) 55 50 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 k= 10 md Perf.= 20% Figure 8.2 Perf.= 40% Perf.= 60% k= 1 md Perf.= 80% Perf.= 100% Gas recovery factor for different length of the top completion. Figures 8.2 and 8.3 show the results for the top completion length evaluation. Four different top completion lengths were evaluated (40%, 60%, 80%, and 100% penetration of the gas zone) for permeability 1 md. Five different top completion lengths were evaluated (20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100% penetration of the gas zone) for 134 permeability 10 md. Bottom completion is located at the top of the aquifer (at 5100 ft) penetrating 20 ft of the water zone. The bottom completion length (20 ft) was constant for each case. Constant water-drainage rate from the bottom completion was used (30 bpd for permeability 1 md, and 200 bpd for permeability 10 md) for each case (Table 8.1). Permeability= 1 md Permeability: 10 md 5,000 Total Production Time (Days) Total Production Time (Days) 15,000 12,000 9,000 6,000 3,000 0 3,000 2,000 1,000 0 Perf.= 40% Figure 8.3 4,000 Perf.= 60% Perf.= 80% Perf.= 20% Perf.= 100% Perf.= 40% Perf.= 60% Perf.= 80% Total production time for different length of the top completion. 135 Perf.= 100% Table 8.1 % of gas zone penetrated Operation conditions for top completion length evaluation Permeability 1 md Length / Length / Location Location Top Complet. Bottom (ft) Comp.(ft) Permeability 10 md Water % of gas zone Length / Length / Rate penetrated Location Location (STB/D) Top Complet. Bottom (ft) Comp.(ft) Water Rate (STB/D) Perf = 40% 40 / (50005040) 20 / (51005120 30 Perf = 20% 20 / (50005020) 20 / (51005120 300 Perf = 60% 60 / (50005060) 20 / (51005120 30 Perf = 40% 40 / (50005040) 20 / (51005120 300 Perf = 80% 80 / (50005080) 20 / (51005120 30 Perf = 60% 60 / (50005060) 20 / (51005120 300 Perf = 100% 100 / (50005100) 20 / (51005120 30 Perf = 80% 80 / (50005080) 20 / (51005120 300 Perf = 100% 100 / (50005100) 20 / (51005120 300 The highest gas recovery for both permeability values happens for the shortest top completion length (Figures 8.2). Also, the longest production time is for the shortest top completion (Figures 8.3). This means that the benefit of DWS is reduced for longer top completion. This effect was also noticed when a comparison of DWS and DGWS was done (Section 7.3.2.). The longer the top completion is, the closer to the gas-water contact is the completion. Then for long completions, water inflows the top completion early. Water rate at the top completion is higher for longer completion, also. Therefore, higher water-drained rates from the bottom completion are needed to maintain the top completion water free. In this case, however, to evaluate the effect of the top completion length alone, the water-drainage rate is constant. In short, DWS delays water loading longer when short top completion are used. The benefit of the highest gas recovery for the shortest top completion length is more evident for permeability 1 md than 10 md (Figure 8.2). This is because of the higher 136 gas mobility related to water. Low permeability delay vertical water movement to the top completion allowing longer water free production of the top completion. 8.2 Effect of Water-drainage Rate from the Bottom Completion Four different water-drainage rates were used to evaluate its effects on gas recovery and production time. Three of them were constant all the time, and the other one was varied to always produce at maximum water rate from the bottom completion (Table 8.2). Location (at the top of the water zone: 5100 ft), and length (20 ft) for the bottom completion is constant for all the cases (1 and 10 md). For permeability 1 md, top completion length was constant penetrating 40% of the gas zone, and the water rates were: 10 bpd, 20 bpd, 30 bpd, and the maximum water rate (from 32 to 39 bpd). For permeability 10 md, top completion length was constant penetrating 20% of the gas zone, and the water rates were: 100 bpd, 200 bpd, 300 bpd, and the maximum water rate (from 300 to 400 bpd). Table 8.2 Operation conditions for water-drained rate evaluation Permeability 1 md % of gas Length / zone Location penetrated Top Complet. (ft) 40% 40% 40% 40% 40 / (50005040) 40 / (50005040) 40 / (50005040) 40 / (50005040) Permeability 10 md Length / Location Bottom Comp.(ft) Water Rate (STB/D) % of gas Length / zone Location penetrated Top Complet. (ft) 20 / (51005120) 20 / (51005120) 20 / (51005120) 20 / (51005120) 10 20% 20 20% 30 20% Qw= Max (32-39) 20% 137 20 / (50005020) 20 / (50005020) 20 / (50005020) 20 / (50005020) Length / Location Bottom Comp.(ft) Water Rate (STB/D) 20 / (51005120) 20 / (51005120) 20 / (51005120) 20 / (51005120) 100 200 300 Qw= Max (300-400) Table 8.2 shows the operational conditions for the water-drained evaluation, and Gas Recovery Factor (%) Figures 8.4 and 8.5 show the results for this analysis. 60 55 50 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Qw= 10 Qw= 20 Qw= 30 bpd bpd bpd Figure 8.4 Qw= Qw= Qw= Max Qw= 100 bpd 200 bpd (32-39 300 bpd bpd) Qw= Max (300400 bpd) Gas recovery factor for different water-drained rate. Permeability: 1 md Permeability: 10 md 5,000 Total Production Time (Days) 16,000 Total Production Time (Days) k= 10 md k= 1 md 12,000 8,000 4,000 0 3,000 2,000 1,000 0 Qw= 10 bpd Figure 8.5 4,000 Qw= 20 bpd Qw= 30 bpd Qw= 100 Qw= 200 bpd Qw= 300 bpd bpd Qw= Max (32-39 bpd) Total production time for different water-drained rate. 138 Qw= Max (300-400 bpd) Gas recovery increases with water-drained rate. The maximum recovery occurs at the maximum water-drainage rate (Figure 8.4). The effect of water drained in gas recovery follows the same pattern on both permeabilities. Production time increases with water-drained rate, also. The longest production time happens at the maximum waterdrainage rate (Figure 8.5). Increasing water-drained rate for permeability 10 md extends the well life, however, the effect of water drained on total production time is small; It means that increasing water-drained rate has a dual effect on gas recovery: increases, and accelerates it at the same time. Removing water from the top completion delays liquid loading of the well. In short, the more water is removed from the top completion, the higher and faster/longer the gas recovery. 8.3 Effect of Separation between the Two Completions Table 8.3 Operation conditions for evaluation completions. of separation between the Permeability 1 md Permeability 10 md Separation % of gas Length / Length / Water Separation % of gas Length / Length / Water between the zone Location - Location - Rate between the zone Location - Location - Rate completions penetrated Top Bottom (STB/D) completions penetrated Top Bottom (STB/D) Comp. (ft) Comp.(ft) Comp. (ft) Comp.(ft) 0 ft 60% 20 ft 60% 40 ft 60% 60 ft 40% 40 / (50005040) 40 / (50005040) 40 / (50005040) 40 / (50005040) 20 / (50415060) 15 0 ft 40% 20 / (50605080) 15 20 ft 40% 20 / (50805100) 15 40 ft 40% 20 / (51005120) 15 60 ft 40% 80 ft 20% 139 20 / (50005020) 20 / (50005020) 20 / (50005020) 20 / (50005020) 20 / (50005020) 20 / (50215040) 150 20 / (50405060) 150 20 / (50605080) 150 20 / (50805100) 150 20 / (51005120) 150 Four (for permeability 1md) and five (for permeability 10 md) different separation distances between the two completions were evaluated. The top completion length was constant, perforating 40% (permeability 1 md) and 20% (permeability 10 md) of the gas zone. Top and bottom completion produced gas from day one. The waterdrainage rate was constant (15 bpd for permeability 1 md and 150 bpd for permeability 10 md) once the bottom completion started producing water (Table 8.3). Figures 8.6 and 8.7 show the results for the evaluation of separation distance between the two completions. 55 Gas Recovery Factor (%) 50 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 k= 10 md Separ.= 0 ft Figure 8.6 Separ.= 20 ft Separ.= 40 ft k= 1 md Separ.= 60 ft Separ.= 80 ft Gas recovery factor for different separation distance between the completions. Gas recovery reduces with the separation between the two completions (Figure 8.6). The highest recovery occurs when the two completions are one after the other. Both permeabilities values (1 md and 10 md) show the same pattern. Reducing separation between the completions increases gas recovery because the inverse gas-cone to the 140 bottom completion is more efficient. The reverse gas-cone is needed on the DWS completion to guarantee water-free production of the top completion. Permeability 1 md Permeability 10 md 6,000 14,000 Total Production Time (Days) Total Production Time (Days) 16,000 12,000 10,000 8,000 6,000 4,000 2,000 0 4,000 3,000 2,000 1,000 0 Separ.= 0 Separ.= ft 20 ft Figure 8.7 5,000 Separ.= 40 ft Separ.= Separ.= Separ.= 0 ft Separ.= 20 ft Separ.= 40 ft 60 ft 80 ft Separ.= 60 ft Total production time for different separation distance between the completions. DWS extends the well life longer when the two completions are together, also (Figure 8.7). Delaying water inflows to the top completion retards well liquid loading. At DWS wells, bottomhole flowing pressure is always different for the two completions (Section 7.3.3) particularly when the water-drained rate is maximized. The fact that the two completion are one the other does not change this situation (Figure 7.19). 8.4 Effect of Bottom Completion Length Four (for permeability 1md) and five (for permeability 10 md) different lengths for the bottom completion were evaluated. The top completion length was constant, perforating 40% (permeability 1 md) and 20% (permeability 10 md) of the gas zone. The 141 bottom completion starts at the end of the top completion. Top and bottom completion begins producing gas from day one. The water-drainage rate was constant (15 bpd for permeability 1 md and 150 bpd for permeability 10 md) once the bottom completion started producing water (Table 8.4). Figures 8.8 and 8.9 show the results for the bottom completion length evaluation. Table 8.4 Operation conditions for different bottom completion length. % of gas zone Perforat. Length / Water Rate % of gas zone penetrated Length - Top Location - (STB/D) penetrated Comp. (ft) Bottom Comp. (ft) Perforat. Length - Top Comp. (ft) Length / Water Rate Location - (STB/D) Bottom Comp. (ft) Perf = 60% 40 20 / (50415060) 15 Perf = 40% 20 20 / (50215040) 150 Perf = 80% 40 40 / (50415080) 15 Perf = 60% 20 40 / (50215060) 150 Perf = 100% 40 60 / (50415100) 15 Perf = 80% 20 60 / (50215080) 150 Perf = 100% plus 10 ft of aquifer 40 80 / (50415120) 15 Perf = 100% 20 80 / (50215100) 150 Perf = 100% plus 10 ft of aquifer 20 100 / (50215120) 150 Gas Recovery Factor (%) 55 50 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 k= 10 md Perf.= 20 ft Figure 8.8 Perf.= 40 ft Perf.= 60 ft k= 1 md Perf.= 80 ft Perf.= 100 ft Gas recovery factor for evaluation of different length at the bottom completion. 142 Permeability 1 md Permeability 10 md 6,000 14,000.0 Total Production Time (Days) Total Production Time (Days) 16,000.0 12,000.0 10,000.0 8,000.0 6,000.0 4,000.0 2,000.0 0.0 4,000 3,000 2,000 1,000 0 Perf.= 20 Perf.= 40 Perf.= 60 ft ft Perf.= 80 ft ft Figure 8.9 5,000 Perf.= 20 ft Perf.= 40 ft Perf.= 60 ft Perf.= 80 ft Perf.= 100 ft Total production time for evaluation of different length at the bottom completion. The highest recovery happens at the shortest bottom completion length. The longest production time occurs at the shortest completion, also. Long bottom completion moves the perforation closer to the gas-water contact, increasing water rate and accelerating the well water load-up. Water inflows the well early. There is a bias on this bottom completion length analysis because longer bottom completions allow higher water-drainage rates, also. For this analysis, however, the water-drainage rate was constant and equal for all the cases. This situation is corrected in the next item. 8.5 DWS Operational Conditions for Gas Wells Some generic guidelines to operate DWS in low productivity gas reservoir could be obtained from the previous study. More modeling, reservoir properties, and production 143 conditions should be done getting a more general idea about how to operate DWS completion in gas reservoir. Statistical procedure similar than the one used in Chapter 6 could be done getting DWS operational-understanding in gas reservoir. According to the previous study, DWS for low productivity gas wells with bottom-water should be operated as follows: • Water should be drained as much as possible with the bottom completion; • The top completion should be short, penetrating between 20% to 40% of the gas zone; • The two completions should be as close as possible; • The bottom completion should be short, penetrating between 20 to 40% of the gas zone, too. The same numerical reservoir model was used to investigate the maximum gas recovery for the optimum DWS operation described above. Separation between the two completions was constant. The two completions are together (The bottom completion begins when the top completion ends). The top completion is operated at constant tubing head pressure (300 psia). The bottom completion is operated at constant tubing head pressure (300 psia) until water production begins; Ones water inflows the bottom completion this completion is switched to produce at maximum water-drainage (Bottom hole flowing pressure is assumed constant and equal to 14.7 psia.). This last assumption could overestimate DWS performance, but in the next item this assumption is removed, and a more realistic bottom hole flowing pressure is assumed. Perforation length is varied for the two completions looking for the maximum gas recovery. Table 8.5 shows the operational conditions for each one of the cases evaluated, and Figures 8.10 to 8.13 shows the results for this evaluations. 144 Table 8.5 Operation conditions for different top completion length, bottom completion length, and water-drained rate. Permeability 1 md % of gas Length / Length / Water zone Location - Location drained penetrated Top Comp. Bottom Rate (ft) Comp. Maximum (ft) (STB/D) Permeability 10 md Separation % of gas Length / Length / Water Separation between zone Location - Location - drained between the two penetrated Top Comp. Bottom Rate the two complet. (ft) Comp. Maximu complet. (ft) (ft) (ft) m (STB/D) Perf = 60% 40 / (5000- 20 / (50415040) 5060) 1 - 19.2 0 Perf = 60% 30 / (5000- 30 / (5031- 7 - 267.3 5030) 5060) 0 Perf = 70% 40 / (5000- 30 / (50415040) 5070) 1 - 26.9 0 Perf = 70% 30 / (5000- 40 / (5031- 1 - 331.7 5030) 5070) 0 Perf = 80% 50 / (5000- 30 / (50515050) 5080) 1 - 26.2 0 Perf = 40% 20 / (5000- 20 / (5021- 1 - 177.3 5020) 5040) 0 Perf = 60% 30 / (5000- 30 / (50315030) 5060) 1 - 28.2 0 Perf = 50% 20 / (5000- 30 / (5021- 1 - 248.4 5020) 5050) 0 Perf = 70% 30 / (5000- 40 / (50315030) 5070) 1 - 36.3 0 Perf = 60% 20 / (5000- 40 / (5021- 1 - 322.7 5020) 5060) 0 Perf = 80% 30 / (5000- 50 / (50315030) 5080) 1 - 44.0 0 Perf = 70% 20 / (5000- 50 / (5021- 1 - 407.3 5020) 5070) 0 Perf = 90% 30 / (5000- 60 / (50315030) 5090) 1 - 51.6 0 Perf = 80% 20 / (5000- 60 / (50215020) 5080) 43.2 465.2 0 Perf = 100% 30 / (5000- 70 / (50315030) 5100) 8.1 - 61.3 0 Perf = 90% 20 / (5000- 70 / (50215020) 5090) 93.1 549.2 0 Perf = 100% plus 10 ft of aquifer 30 / (5000- 80 / (5031- 31.6 - 84.5 5030) 5110) 0 Perf = 100% 20 / (5000- 80 / (50215020) 5100) 167.9 658.4 0 Perf = 100% plus 10 ft of aquifer 20 / (5000- 90 / (50215020) 5110) 376.9 898.3 0 Figures 8.10 and 8.11 show the results for permeability 1 md. Top completion length was varied from 20 to 50 feet (20 to 50% gas zone penetration). Bottom completion length was varied from 20 to 80 feet. Together the two completions penetrate from 60% to 100% of the gas zone including a case where 10 feet of the aquifer was perforated, also. 145 65 60 55 Gas Recovery (%) 50 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Top= 40 ft, Bott.=20 ft Top=40 ft, Bott.=30ft Top=50ft, Bott.=30ft Top=30ft, Bott.=30ft Top=30ft, Bott.=40ft Top=30ft, Bott.=50ft Top=30ft, Bott.=60ft Top=30ft, Bott.=70ft Top=30ft, Bott.=80ft Figure 8.10 Gas recovery for different lengths of top, and bottom completions and maximum water drained. The two completions are together. Reservoir permeability is 1 md. 60,000 Total Production Time (Days) 50,000 40,000 30,000 20,000 10,000 0 Top= 40 ft, Bott.=20 ft Top=40 ft, Bott.=30ft Top=50ft, Bott.=30ft Top=30ft, Bott.=30ft Top=30ft, Bott.=40ft Top=30ft, Bott.=50ft Top=30ft, Bott.=60ft Top=30ft, Bott.=70ft Top=30ft, Bott.=80ft Figure 8.11 Total production time for different lengths of top and bottom completions and maximum water drained. The two completions are together. Reservoir permeability is 1 md. 146 The maximum recovery happens when the top completion penetrates 30 ft and the bottom completion penetrates 80 ft (Figure 8.10). This is the scenario where 10 ft of the aquifer were penetrated. Increasing top completion length more than 30 ft gives no extra recovery. Actually, the lowest recovery happens when the top completion penetrates 50% of the gas zone. In short, increasing bottom completion length increases gas recovery when the water-drainage rate is increased at the same time. For top completion penetration of 30% of the gas zone, the total production time (TPT) increases when bottom completion is increased from 30 to 50 ft. TPT, however, decreases when bottom completion length increases from 60 to 80 ft. In short, increasing bottom completion length and water-drainage rate at the same time increases and accelerates gas recovery. 70 65 60 55 Gas Recovery (%) 50 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Top=30ft, Bott.=30ft Figure 8.12 Top=30ft, Bott.=40ft Top=20ft, Bott.=20ft Top=20ft, Bott.=30ft Top=20ft, Bott.40ft Top=20ft, Bott.=50ft Top=20ft, Bott.=60ft Top=20ft, Bott.70ft Top=20ft, Bott.80ft Top=20ft, Bott.=90 Gas recovery for different lengths of top, and bottom completions and maximum water drained. The two completions are together. Reservoir permeability is 10 md. 147 Figures 8.12 and 8.13 confirm the previous finding. Figures 8.12 and 8.13 show the results for permeability 10 md. Top completion length was varied from 20 to 30 feet (20% to 30% gas zone penetration). Bottom completion length varied from 20 to 90 feet. Together the two completions penetrate from 40% to 100% of the gas zone including a case where 10 feet of the aquifer was perforated, too. Figure 8.12 shows gas recovery for the ten cases evaluated. The maximum recovery occurs when the top completion penetrates 20 ft and the bottom completion penetrates 90 ft. This is the scenario where 10 feet of the aquifer was penetrated. Increasing top completion length more than 20 ft gives no extra recovery. Actually, gas recovery is always lower when the top completion penetrates 30 feet instead of 20 feet of the gas zone. Again, increasing bottom completion length increases gas recovery when water-drainage rate is increased at the same time. 7,000 Total Production Time (days) 6,000 5,000 4,000 3,000 2,000 1,000 0 Top=30ft, Bott.=30ft Top=30ft, Bott.=40ft Top=20ft, Bott.=20ft Top=20ft, Bott.=30ft Top=20ft, Bott.40ft Top=20ft, Bott.=50ft Top=20ft, Bott.=60ft Top=20ft, Bott.70ft Top=20ft, Bott.80ft Top=20ft, Bott.=90 Figure 8.13 Total production time for different lengths of both completions and maximum water drained. The two completions are together. Reservoir permeability is 10 md. 148 Figure 8.13 shows Total Production Time (TPT) for the ten cases evaluated. For top completion penetration of 20% of the gas zone, TPT always decreases when bottom completion is increased from 20 to 90 ft. Therefore; Increasing bottom completion length, once more, accelerates gas recovery when water-drainage rate is increased at the same time. 8.5.1 Effect of Bottom Hole Flowing Pressure at the Bottom Completion The previous analysis was done assuming bottom hole flowing pressure (BHP) equal to atmospheric pressure (14.7 psia). This situation would overestimate DWS performance. Three different values for constant BHP were used to evaluate its effect on gas recovery and TPT. Table 8.5 shows the operational conditions used for this analysis, and Figures 8.14 and 8.15 show the results. Table 8.6 Operation conditions for evaluation of different constant bottomhole flowing pressure at the bottom completion. Permeability 1 md Permeability 10 md Bottomhole Flowing Pressure (psia) Length / Length / Water drained Bottomhole Length / Length / Water drained Location Location Rate Flowing Location Location Rate Top Comp. Bottom Maximum Pressure Top Comp. Bottom Maximum (ft) Comp. (ft) (STB/D) (psia) (ft) Comp. (ft) (STB/D) BHP= 14.7 30 / (50005030) 80 / (50315110) 31.6 - 84.5 BHP= 14.7 20 / (50005020) 90 / (50215110) 376.9 - 898.3 BHP= 100 30 / (50005030) 80 / (50315110) 30.2 - 80.3 BHP= 100 20 / (50005020) 90 / (50215110) 359.2 - 832.6 BHP= 200 30 / (50005030) 80 / (50315110) 28.2 - 74.8 BHP= 200 20 / (50005020) 90 / (50215110) 335.5 - 777.6 BHP= 300 30 / (50005030) 80 / (50315110) 26.2 - 68.46 BHP= 300 20 / (50005020) 90 / (50215110) 310.3 - 714.3 149 70 Gas Recovery (%) 60 50 40 30 20 10 k= 10 md 0 BHP= 14.7 psia BHP=100 psia k= 1 md BHP=200 psia BHP=300 psia Figure 8.14 Gas recovery for different constant BHP at the bottom completion. Figure 8.14 shows that increasing BHP at the bottom completion from 14.7 psia to 300 psia slightly reduces gas recovery (gas recovery reduces from 64.37% to 62.1% for permeability 1 md, and from 64.37% to 62.1% for permeability 10 md). Permeability 1 md Permeability 10 md 6,000 Total Production Time (Days) Total Production Time (Days) 60,000 50,000 40,000 30,000 20,000 10,000 0 5,000 4,000 3,000 2,000 1,000 0 BHP= 14.7 psia BHP=100 psia BHP=200 psia BHP= 14.7 psia BHP=300 psia BHP=100 psia BHP=200 psia BHP=300 psia Figure 8.15 Total Production Time for evaluation of different constant BHP at the bottom completion. 150 Increasing BHP at the bottom completion from 14.7 psia to 300 psia increases total production time, particularly for permeability 10 md (Figure 8.15). This is because less amount of water is drained from the bottom completion when the bottomhole pressure (BHP) is increased delaying well life. For permeability 1 md, however, the situation reverses when BHP is increased beyond 100 psia. Increasing BHP at the bottom completion from 100 psia to 200 psia reduces the amount of water drained increasing the aquifer effect on the reservoir. Bottom hole pressure at the top completion is higher for BHP=200 psia than for BHP=100 psia (Figure 8.16). Also, average reservoir pressure is higher for BHP=200 psia than for BHP=100psia (Figure 8.17). In short, for permeability 1 md, increasing BHP at the bottom completion beyond 100 psia increases aquifer effect on the reservoir pressure, reducing well life. Bottomhole Flowing Pressure (psia) 900 TopCompletion (BHP= 200 psia) 800 700 600 TopCompletion (BHP= 100 psia) 500 400 300 Bottom Completion (BHP= 200 psia) 200 Bottom Completion (BHP= 100 psia) 100 0 0 10000 20000 30000 40000 50000 Time (Days) Top Completion (BHP= 200 psia) Bottom Completion (BHP= 200 psia) Top Completion (BHP= 100 psia) Bottom Completion (BHP= 100 psia) Figure 8.16 Flowing Bottomhole Pressure history at the top, and bottom completion for two different constant BHP at the bottom completion (100 psia, and 200 psia). Permeability is 1 md. 151 60000 Average Reservoir Pressure (psia) 1200 1000 800 600 400 200 0 0 10000 20000 30000 40000 50000 60000 Time (Days) Reservoir Pressure (BHP= 200 psia) Reservoir Pressure (BHP= 100 psia) Figure 8.17 Average reservoir for two different constant BHP at the bottom completion (100 psia, and 200 psia). Permeability is 1 md. Another important observation is that the BHP at the top and bottom completion is always different (Figure 8.16). There is a drawdown of at least 150 psia (for BHP at the bottom completion equal to 200 psia), and 250 psia (for BHP at the bottom completion equal to 100 psia). It is not possible to have this drawdown for two close-completion without isolation. Therefore, the packer insulation between the two completions is needed for the DWS completion in low productivity gas wells to guarantee the drawdown between the completions. This observation is in general agreement with the discussion included on section 7.3.3 when DWS was compared with DGWS. 152 8.6 When to Install DWS in Gas Wells Four different scenarios for “when” DWS should be installed were evaluated: when water production begins in a top short completion (30% for permeability 1 md and 20% for permeability 10 md), at late time in a totally perforated well, from day one of production, and after the well die. Water-drainage is maximum all the time for the scenarios when DWS is installed. The top completion length is 30 feet for permeability 1 md and 20 feet for permeability 10 md. The bottom completion length is 70 feet for permeability 1 md and 80 feet for permeability 10 md. Table 8.7 includes the operation conditions for the cases used for this study, and Figures 8.18 and 8.19 show the results. Table 8.7 Water Drained Rate Operation conditions for “when” to install DWS in low productivity gas well. Permeability 1 md Length / Length / When Installing Location Location DWS Top Comp. Bottom (ft) Comp. (ft) Water Drained Rate Permeability 10 md Length / Length / Location Location Top Comp. Bottom (ft) Comp. (ft) When Installing DWS Qw = Max 30 (50005030) 70 (50315100) After well died Qw = Max 20 / (50005020) 80 / (50215100) After well died Qw = Max 30 (50005030) 70 (50315100) Late time in a Qw = Max totally perforated well 20 / (50005020) 80 / (50215100) Late time in a totally perforated well Qw = Max 30 (50005030) 70 (5031Water Qw = Max 5100) production starts in the top short completion 20 / (50005020) 80 / (50215100) Water production starts in the top short completion Qw = Max 30 (50005030) 70 (50315100) 20 / (50005020) 80 / (50215100) From day one From day one Qw = Max 153 Gas Recovery (%) 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 After the Late in a well die totally Perforated When From Day Water One Prod. begins in a 30% Perf. k = 10 md After the well die Late in a totally Perforated k = 1 md When From Day Water One Prod. begins in a 20% Perf. Figure 8.18 Gas recovery for different times of installing DWS. Permeability 10 md 60,000 6,000 50,000 5,000 Total Production Time (Days) Total Production Time (Days) Permeability 1 md 40,000 30,000 20,000 10,000 4,000 3,000 2,000 1,000 0 After the well die 0 Late in a When Water From Day totally Prod. begins One Perforated in a 30% Perf. After the well die Late in a When Water totally Prod. begins Perforated in a 30% Perf. From Day One Figure 8.19 Total production time for different times of installing DWS. 154 Figure 8.18 shows that: The lowest recovery occurs when DWS is installed after the well die (Actually, there is no extra recovery when DWS is installed after the well die); the highest recovery happens when DWS is installed from day one, and when water production begins (The final recovery is almost the same when DWS is installed from day one of production or at the beginning of water production in a short top perforated well); Installing DWS late in a totally perforated well reduces final gas recovery. Total production time slightly decreases when DWS is installed from day one than when water production begins; Total production time is shorter when DWS is installed late in a totally perforated well than when is installed from day one or when water production begins (Figure 8.19). Some comments can be made for DWS completion in a low productivity reservoir from the previous analysis: • DWS should not be installed after the well die. It is better to use another technology available solving water production problems such as: gas lift, pumping units, plunger, soap injection, etc. • There is no extra benefit installing DWS from day one of well production. • DWS should be installed early in the well life after water production begins. Figure 8.20 shows the gas recovery history for the scenarios considered when permeability is 10 md (the scenario “after the well died” is represented by the conventional 100% perforated well because there is no extra gas recovery when DWS is installed after the well has died). It is shown that the final gas recovery is the same when DWS is installed from day one and when it is installed after water production begins. 155 70 65 60 Gas Recovery Factor (%) 55 50 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 Time (Days) Late in a Totally Perf. Conv. 100% Perf. When Water Prod. Begins in a 20% Perf. From Day One Figure 8.20 Cumulative gas recovery for different times of installing DWS. Reservoir permeability is 10 md. 8.7 Recommended DWS Operational Conditions in Gas Wells According to this study, the best operational conditions for DWS in gas wells are: • Water should be drained with the bottom completion at the highest rate possible; • The top completion should be short, penetrating between 20% to 40% of the gas zone; • The two completions should be as close as possible; • A packer is needed to insolate the completions; • The bottom completion should be long, penetrating the rest of the gas zone and even the top of the aquifer; • DWS should be installed early in the well life after water production begins. 156 • Producing the drained-water at the surface together with the gas from the bottom completion, instead of injecting the water downhole, has little effect on the final gas recovery. Therefore, drained water can be lifted to the surface when there is no deeper injection-zone. 157 CHAPTER 9 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 9.1 Conclusions • In gas wells, a water cone is generated in the same way as in the oil-water system. The shape at the top of the cone, however, is different in oil-water than in gaswater systems. For the oil-water, the top of the cone is flat. For the gas-water system, a small inverse gas cone is generated locally around the completion. This inverse cone restricts water inflow to the completions. Also, the inverse gas cone inhibits upward progress of the water cone. • Vertical permeability, aquifer size, Non-Darcy flow effect, density of perforation, and flow behind casing are unique mechanisms improving water coning/production in gas reservoirs with bottom water drive. • There is a particular pattern for water production rate at a gas well located in a water drive reservoir with a channel in the cemented annuls—having a single entrance at its end-. First, there is no water production. Next, water production starts and water rate increases almost linearly. This increment is more dramatic when the channel is originally in the water zone. Then, water rate stabilizes. Finally, water rate increases exponentially. This pattern is explained because of the flowing phases (single of two phase flow) in the channel at different production steps of the well. • Non-Darcy flow effect is important in low-rate gas wells producing from lowporosity, low-permeability gas reservoirs. It is possible to have a gas well flowing 158 at 1 MMscfd with 60% of the pressure drop generated by the Non-Darcy flow effect (porosity 1%, permeability 1 md). • Setting the Non-Darcy flow component at the wellbore does not make reservoir simulators represent correctly the Non-Darcy flow effect in gas wells. Non-Darcy flow should be considered globally (distributed throughout the reservoir) to correctly predict the gas rate and recovery. • Cumulative gas recovery could be reduced up to 42.2% when Non-Darcy flow effect is considered throughout the reservoir in gas reservoirs with bottom water drive. This is because the well loads up early and is killed for water production. • The most promising design of Downhole Water Sink (DWS) installation in gas wells includes dual completion with isolated packer between them and gravity gas-water separation at the bottom completion. The design allows good control of water coning outside the well and increases coning of gas and maximum rate at the top completion with no water loading. • The highest recovery for a conventional gas well in the low-permeability reservoir (1-10 md) occurs when the gas zone is totally penetrated. For permeability 100 md, gas recovery becomes almost insensitive to the completion length for penetration greater than 30%. • Gas recovery increases with permeability for a gas reservoir with bottom water drive. In general, high permeability allows higher gas rates with smaller reservoir drawdown; therefore the well has more energy to produce gas with higher water cut. 159 • The optimum completion length can be calculated from the model developed here, for maximum net present value. A “rule of thumb” is to perforate 80% of the gas zone in a gas reservoir with bottom-water drive. • Gas recovery with DWS is always higher than recovery with conventional wells. The best reservoir conditions to apply DWS are when permeability is smaller than 10 md, and reservoir pressure is subnormal (or depleted). For reservoirs with lowpermeability (1 md) and subnormal pressure, gas recovery increases 160% for DWS completion. This advantage, however, reduces what to 10% for permeability 10 md and normal reservoir pressure. • For the reservoir model used here, Downhole Gas-Water Separation (DGWS) and DWS could give almost the same final gas recovery, but DWS production time is 35 % shorter than that of DGWS wells. Also, the DWS well would produce less water at the surface because most of the water would inflow the bottom completion and be injected downhole. • Packer insulation between the two completions is needed for the DWS configuration in low productivity gas wells. There should a drawdown between the completions to guarantee reverse gas cone inflows to the bottom completion improving control on the water coning. • The recommended operational conditions for DWS in gas wells located in bottom water drive reservoirs are: Water would be drained with the bottom completion at the highest rate possible. The top completion would be short, penetrating between 20% to 40% of the gas zone. The two completions should be as close as possible. A packer should insolate the two completions. The bottom completion would be long, penetrating the rest of the gas zone and even the top of the aquifer. DWS 160 would be installed early at the well life after water production begins. Producing the drained-water at the surface together with the gas from the bottom completion, instead of injecting the water downhole, has little effect on the final gas recovery. 9.2 Recommendations • The water rate pattern found in a gas well with leaking cement could be confirmed using field data. Production data for gas wells with leaking cement would be analyzed looking for the described pattern. • Effects of Non-Darcy flow in low-productivity gas wells should be studied considering a fracture in the well. A normal practice in the industry is to fracture gas wells with low productivity. Non-Darcy flow distributed in the reservoir and into the fracture should be considered. • Effects of a fracture and permeability heterogeneity in water production, and final gas recovery should be evaluated in water drive gas reservoirs using numerical simulators. • More possible configurations for DWS in gas wells should be evaluated. A single very long completion (totally perforating the gas zone and the top of the aquifer) without a packer could be one of the many new possibilities. • Economic evaluation of DWS in gas wells should be done. This evaluation should consider not only injecting drained-water into a lower zone but lifting water to the surface, also. • A combined mechanism of DWS and two fractures (one in the top completion and the other in the bottom completion) in a low productivity gas well should be evaluated. 161 • More in-depth study involving different modeling, reservoir properties, and production conditions should be done getting a better understanding of DWS operations in gas reservoir. • More in-depth study involving different modeling, reservoir properties, and production conditions should be done for comparison of DWS and DGWS identifying best opportunity for each technology. • A field pilot project installing DWS in low productivity gas reservoirs should be conducted. This project should refine the operational optimization performed in this research, giving new information about the possibilities of DWS in low productivity gas reservoirs. 162 REFERENCES Abercrombie, B., 1980, “Plunger Lift,” The Technology of Artificial Lift Methods,” Vol. 2b, K.E. Brown (ed), PennWell Publ. Co., Tulsa, OK (1980), p483-518. Adams, L.S., and Marsili, D.L., 1992, “Design and Installation of a 20,500-ft Coiled Tubing Velocity String in the Gomez Field, Pecos County, Texas,” paper SPE 24792, 67th Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Washington, D.C., October 4-7. Agarwal, R.G., Al-Hussainy, R., and Ramey, Jr. H.J., 1965, “The Importance of Water Influx in Gas Reservoir,” Journal of Petroleum Technology, November, 1965, p1336-42. Aguilera, R., Conti, J.J., Lagrenade E., 2002, “Reducing Gas Production Decline Through Dewatering: A Case History From the Naturally Fractured Aguarague Field, Salta, Argentina,” paper SPE 75512, SPE Gas Technology Symposium, Calgary, Canada, 30 April-2 May. Alvarez, C.H., Holditch, S.A, McVay, D.A., 2002, “Effects of Non-Darcy Flow on Pressure Transient Analysis of Hydraulically Fractured Gas Wells,” paper SPE 77468, Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, San Antonio, TX, 29 September-2 October. Amyx, J.W., Bass, D.M., Whitinig, R.L. 1960, “Petroleum Reservoir Engineering,” McGraw-Hill, New York, p 64-68. Arcaro, D. P. and Bassiouni, Z. A., 1987, “The Technical And Economic Feasibility of Enhanced Gas Recovery in The Eugene Island Field by Use a Coproduction Technique,” Journal of Petroleum Technology (May 1987), p585-90. Armenta, M., and Wojtanowicz, A.K., 2003, “Incremental Recovery Using DualCompleted Wells in Gas Reservoir with Bottom Water Drive: A Feasibility Study,” paper 2003-194 Canadian International Petroleum Conference-2003, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, June 10-12. Armenta, M., White, C., Wojtanowicz, A.K., 2003, “Completion Length Optimization in Gas Wells,” paper 2003-192 Canadian International Petroleum Conference-2003, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, June 10-12. Armenta, M., and Wojtanowicz, A., 2002, “Severity of Water Coning in Gas Wells,” paper SPE 75720 SPE Gas Technology Symposium, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, 30 April-2 May. Arthur, M.G., 1944, “Fingering and Coning of Water and Gas in Homogeneous Oil Sand,” AIME Transactions, Vol. 155, 184-199. 163 Avery, D.J. and Evans, R.D., 1988, “Design Optimization of Plunger Lift Systems,” paper SPE 17585, International Meeting on Petroleum Engineering of the SPE, Tianjin, China, Nov. 1-4. Awadzi, J., Babbitt, J., Holland, S., Snyder, K., Soucer, T., Latter, K., 1999, “Downhole Capillary Soap Injection Improves Production,” paper SPE 52153, Mid-Continent Operations Symposium, Oklahoma City, OK, March 28-31. Baruzzi, J.O.A., Alhanati, F.J.S., 1995, “Optimum Plunger Lift Operation,” paper SPE 29455, Production Operations Symposium, Oklahoma City, OK, April 2-4. Bear, J., 1972, “Dynamic of Fluids in Porous Media”, Dover Publications, INC., New York. Beauregard, E., and Ferguson, P.L., 1982, “Introduction to Plunger Lift: Applications, Advantages and Limitations,” paper SPE 10882, Rocky Mountain Regional Meeting of the SPE, Billings, MT, May 19-21. Beattle, D.R. and Roberts, B.E., 1996, “Water Coning in Naturally Fractured Gas Reservoirs,” Paper SPE 35643, Gas Technology Conference, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, 28 April – 1 May. Beeson, C.M., Knox, D.G., and Stoddard, J.H., 1958, “Short-Cut Design Calculations and Field Applications of the Plunger Lift Method of Oil Production,” The Petroleum Engineer, (June-Oct. 1958). Beggs H.D. 1984, “Gas Production Operation,” Oil and Gas Consultants International, Inc, Tulsa, Oklahoma, p53-59. Berry, D. A., 196, “Statistics: A Bayesian Perspective,” Wadsworth Publishing Co., Belmont, CA, 518 p. Bizanti, M.S., and Moonesan, A., 1989, “How to Determine Minimum Flow Rate for Liquid Removal,” World Oil, (September, 1989), p 71-73. Bourgoyne, A.T., Chenevert, M.E., Millheim, K.K., Young, F.S. 1991, “Applied Drilling Engineering,” Society of Petroleum Engineering Textbook Series Volume 2, Richardson, TX, p137-155. Box, G. E. P. and Cox D.R., 1964 “An Analysis of Transformations,” J. of the Royal Statistical Society, 26 No. 2, 211-252 Box, G. E. P. and Tidwell, P.W., 1962 “Transformation of the Independent Variables,” Technometrics, 4 No. x, 531-550. Brady, C.L., and Morrow, S.J., 1994, “An Economic Assessment of Artificial Lift in Low-Pressure Tight Gas Sands in Ochiltree County, Texas,” paper SPE 27932, SPE Mid-Continent Gas Symposium, Amarillo, TX, May 22-24. 164 Brar, S.G., Aziz, K., 1978, “Analysis of Modified Isochronal Test To Predict The Stabilized Deliverability Potential of Gas Well Without Using Stabilized Flow Data,” JPT (Feb.) 297-304; Trans. AIME, p297-304. Campbell, S., Ramachandran, S., and Bartrip, K., 2001, “Corrosion Inhibition/Foamer Combination Treatment to Enhance Gas Production,” paper SPE 67325, Production and Operations Symposium, Oklahoma City, OK, March 24-27. Chaperon, I., 1986, “Theoretical Study of Coning Toward Horizontal and Vertical Wells in Anisotropic Formations: Subcritical and Critical Rates,” paper SPE 15377, SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, New Orleans, Oct. 5-8. Cohen, M.F. 1989, “Recovery Optimization in a Bottom/Edge Water-Drive Gas Reservoir, Soehlingen Schneverdinge,” paper SPE 19068 SPE Gas Technology Symposium, Dallas, June 7-9. Coleman, S.B., Hartley, B.C., McCurdy, D.G., and Norris III, H.L., 1991, “A New Look at Predicting Gas-Well Load-up,” J. Pet. Tech. (Mar. 1991) p329-38. Computer Modelling Group Ltda, 2001, “User’s Guide, IMEX, Advanced Oil/Gas Reservoir Simulator,” CMG, p425-26. Craft B.C. and Hawkins M.F. 1959, “Applied Petroleum Reservoir Engineering,” Prentice Hall PTR, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, p300-01. Craft B.C. and Hawkins M.F. 1991, “Applied Petroleum Reservoir Engineering,” Prentice Hall PTR, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, p226-227; 280-299. Dake L.P., 1978, “Fundamentals of Reservoir Engineering,” Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company, New York, p255-258. Damsleth, E., Hage, A. and Volden, R., 1992: “Maximum Information at Minimum Cost: A North Sea Field Development Study with Experimental Design,” J. Pet. Tech (December 1992) 1350-1360. Dejean, J.-P., and Blanc, G., 1999, “Managing Uncertainties on Production Predictions Using Integrated Statistical Methods,” Paper SPE 56696, SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Houston, Texas, 3-6 October. Dranchuck, P.M., Purvis, R.A., and Robinson, D.B., 1974, “Computer Calculations of Natural Compressibility Factors Using the Standing and Katz Correlations,” Institute of Petroleum Technical Series. Economides, M.J., Oligney, R.E., Demarchos, A.S., and Lewis, P.E., 2001, “Natural Gas: Beyond All Expectations,” Paper SPE 71512, Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, New Orleans, 30 September- 3 October. 165 E&P Environment, 2001, “GTI Studies Gas Well Water Management,” J&E Communication, Inc, Vol. 12 No. 23, p1-4. Elmer, W.G., 1995, “Tubing Flow Rate Controller: Maximize Gas Well Production From Start To Finish,” paper SPE 30680, SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Dallas, September 22-25. Energy Information Administration, 2000, “Distribution of Gas Wells and Production,” http://www.eia.doe.gov/pub/poi_gas/petrosystem/natural_gas/petrosysgas.html Energy Information Administration, 2001, “U.S. Crude Oil, Natural Gas, and Natural Gas Liquids Reserves 2001 Annual Report,” http://www.eia.doe.gov/pub/oil_gas/natural_gas/data_publications/crude_oil_natu ral_gas_reserves/current/pdf/ch4.pdf Energy Information Administration, 2001, “U.S. Natural Gas Markets: Recent Trends and Prospects For the Future,” http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/FTPROOT/service/oiaf0102.pdf Energy Information Administration, 2003, “Annual Energy Outlook 2003 With Projection to 2025,” www.eia.doe.gov/oiaf/aeo, January. Energy Resources and Conservation Board, 1975, Theory and Practice of The Testing of Gas Wells, third edition, Pub. ERCB-75-34, ERCB, Calgary, Alberta, p3-18 to p321. Ergun, S. and Orning, A.A., 1949, “Fluid Flow Through Ramdomly Packed Collumns and Fluidized Beds.” Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 41, No 6, p11791184. Evan, R.D., Hudson, C.S., Greenlee, J.E., 1987, “The Effect of an Immobile Liquid Saturation on the Non-Darcy Flow Coefficient in Porous Media,” SPE Production Engineering (November ), p331-38. Ferguson, P.L., and Beauregard, E., 1985, “How to Tell if Plunger Lift Will Work in Your Well,” World Oil, August 1, p33-36. Fligelman, H., Cinco-Ley, H., Ramley Jr., Braester, C., Couri, F., 1989, “PressureDrawdown Test Analysis of a Gas Well Application of New Correlation,” paper SPE 17551 Facilities Engineering, September (1989) p409. Flowers, J.R., Hupp, M.T., and Ryan, J.D., 2003, “The Results of Increased Fracture Conductivity on Well Performance in a Mature East Texas Gas Field,” paper SPE 84307 Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Denver, Colorado, October 5-8. 166 Foss, D.L., and Gaul, R.B., 1965, “Plunger-Lift Performance Criteria with Operating Experience-Ventura Avenue Field,” Drilling and Production Practice, API (1965), p124-40. Frederick, D.C., Graves, R.M., 1994, “New Correlations To Predict Non-Darcy Flow Coefficients at Immobile and Mobile Water Saturation,” paper SPE 28451 Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, New Orleans, Sept. 25-28 Gasbarri, S. and Wiggins, M.L., 2002, “A Dynamic Plunger Lift Model for Gas Wells,” SPE Production and Facilities, May 2001, p89-96. Geertsma, J., 1974, “Estimating the Coefficient of Inertial Resistance in Fluid Flow through Porous Media,” SPEJ (Oct. 1974) p445-450. Girardi, F., Lagrenade, E., Mendoza, E., Marin, H. and Conti, J.J., 2001, “Improvement of Gas Recovery Factor Through the Application of Dewatering Methodology in the Huamampampa Sands of the Agurague Field,” paper SPE 69565, SPE Latin American and Caribbean Petroleum Engineering Conference, Buenos Aires, Argentina, March 25-28. Golan M. and Whitson C., 1991, “Well Performance,” Prentice-Hall Inc., New Jersey, p268-284. Grubb, A.D., and Duvall, D.K., 1992, “Disposal Tool Technology Extends Gas Well Life and Enhances Profits,” paper SPE 24796, 67th Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition of the SPE, Washington, D.C., October 4-7. Hacksma, J.D., 1972, “Users Guide to Predict Plunger Lift Performance,” Proceeding, Texas Tech. U. Southwestern Petroleum Short Course, Lubbock, TX. Hasan, A.R., and Kabir, C.S., 1985, “Determining Bottomhole Pressures in Pumping Wells,” SPEJ (Dec., 1985) 823-38. Hebert, D.W., 1989, “A Systematic Approach To Design of Rod Pumps in Coal Degasification Wells: San Juan Basin, New Mexico,” paper SPE 19011, SPE Joint Rocky Mountain Regional/Low Permeability Reservoirs Symposium and Exhibition, Denver, Colorado, March 6-8. Henderson L.J., 1984, “Deep Sucker Rod Pumping for Gas Well Unloading,” paper SPE 13199, 59th Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Houston, TX, September 16-19. Hernandez, A., Marcano, L., Caicedo, S., and Carbunaru, R., 1993, “Liquid Fall-back Measurements in Intermittent Gas Lift with Plunger,” paper SPE 26556, SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Houston, TX, October 3-6. 167 Hoyland, L.A., Papatzacos, P., and Skjaeveland, S.M., 1989, “Critical Rate for Water Coning: Correlation and Analytical Solution,” SPE Reservoir Engineering, p459502, November 1989. Houpeurt, A., 1959, “On the Flow of Gases in Porous Media,” Revue de L’Institut Français du Pétrole (1959) XIV (11), p1468-1684. Hutlas, E.J. and Granberry, W.R., 1972, “A Practical Approach to Removing Gas Well Liquids,” J. Pet. Tech., (August 1972) 916-22. Ikoku, C.I., 1984, “Natural Gas Production Engineering,” John Wiley & Sons, New York, p369. Inikori, S.O., 2002, “Numerical Study of Water Coning Control With Downhole Water Sink (DWS) Well Completions in Vertical and Horizontal Well,” PhD dissertation, Louisiana State University and A&M College, Baton Rouge, LA, August. Irmay, S, 1958, “On the Theoretical Derivation of Darcy and Forchheimer Formulas,” Trans., American Geophysical Union 39, No 4, p702-707. Janicek, J.D., and Katz, D.L., 1995, “Applications of Unsteady State Gas Flow Calculations,” Proc., U. of Michigan Research Conference, June 20. Jensen, J.L., Lake, L.W., Corbett, P.W.M., and Goggin, D.J., 2000, “Statistics for Petroleum Engineers and Geoscientists,” Elsevier, New York. Jones, S.C., 1987, “Using the Inertial Coefficient, β, To Characterize Heterogeneity in Reservoir Rock,” paper SPE 16949 SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Dallas, Sept. 27-30. Jones, L.G. and Watts, J.W., Feb. 1971, “Estimating Skin Effects in a Partially Completed Damaged Well,” JPT 249-52; AIME Transactions, 251. Joshi, S.D., 1991, “Horizontal Well Technology,” PennWell Books, Tulsa, Oklahoma, p251-267. Katz, D.L., Cornell, D., Kobayashi, R., Poettman, F.H., Vary, J.A., Elenbans, J.R., and Weinaug, C.F., 1959, “Handbook of Natural Gas Engineering,” McGraw-Hill Book Co., Inc., New York, p46-51. Kabir, C.S., 1983, “Predicting Gas Well Performance Coning Water in Bottom-Water Drive Reservoirs,” Paper SPE 12068, 58th Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, San Francisco, Oct 5-8. Klein, S.T., 1991, “The Progressing Cavity Pump in Coaled Methane Extraction,” paper SPE 23454, SPE Eastern Regional Meeting, Lexington, Kentucky, October 22-25. 168 Klein, S.T., Thompson, S., 1992, “Field Study: Utilizing a Progressing Cavity Pump for a Closed-Loop Downhole Injection System,” paper SPE 24795, 67th Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition of the SPE, Washington, D.C. October 4-7. Lea, J.F., 1982, “Dynamic Analysis of Plunger Lift Operations,” Journal of Petroleum Technology, (Nov. 1982), p2617-2629. Lea, J.F., Winkler, H.W., and Snyder, R.E., 2003, “What’s new in artificial lift,” World Oil, (April, 2003), p 59-75. Lea Jr., J.F., and Tighe, R.E., 1983, “Gas Well Operation With Liquid Production,” Paper SPE 11583, Production Operation Symposium, Oklahoma City, OK, February 27March 1. Lee J., 1982, Well Testing, Society of Petroleum Engineering of AIME Textbook Series Volume 1, New York, p82-84. Lee, A.L., Gonzales, M.H., and Eakin, B.E., 1966, “The Viscosity of Natural Gases,” Journal of Petroleum Technology, (August 1966). Lee J. and Wattenbarger R. 1996, “Gas Reservoir Engineering”, Society of Petroleum Engineering Textbook Series Volume 5, Richardson, Texas, p32; p170-174; p245. Libson, T.N., Henry, J.R., 1980, “Case Histories: Identification of and Remedial Action for Liquid Loading in Gas Wells –Intermediate Shelf Gas Play,” Journal of Petroleum Technology, (April, 1980), p685-93. Liu, X., Civan, F., and Evans, R.D., 1995, “Correlation of the Non-Darcy Flow Coefficient,” J. Cdn. Pet. Tech. (Dec. 1995) 34, No 10, p50-54. Lombard, J-M., Longeron, D., Kalaydjan, F., 1999, “Influence of Connate Water and Condensate Saturation on Inertia Effect in Gas Condensate Fields,” paper SPE 56485 SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Houston, October 3-6. Manceau, E., Mezghani M., Zabalza-Mezghani, I., and Roggero, F., 2001, “Combination of Experimental Design and Joint Modeling Methods for Quantifying the Risk Associated with Deterministic and Stochastic Uncertainties—An Integrated Test Study,” paper SPE 71620, SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, New Orleans, Louisiana, 30 September-3 October. Maggard, J.B., Wattenbarger, R.A., and Scott, S.L., 2000, “Modeling Plunger Lift for Water Removal From Tight Gas Wells,” paper SPE 59747, SPE/CERI Gas Technology Symposium, Calgary, Alberta Canada, April 3-5. 169 Marcano, L. and Chacin, J., 1992, “Mechanistic Design of Conventional Plunger Lift Installations,” paper SPE 23682, Second Latin American Petroleum Engineering Conference of the SPE, Caracas, Venezuela, March 8-11. McLeod, H.D. Jr. Jan. 1983, “The Effect of Perforating Conditions on Well Performance,” JPT, p31-39. McMullan, J.H., Bassiouni, Z., 2000, “Optimization of Gas-Well Completion and Production Practices,” Paper SPE 58983, International Petroleum Conference and Exhibition, Mexico, Feb 1-3. Melton, C.G., and Cook, R.L., 1964, “Water-Lift and Disposal Operations in LowPressure Shallow Gas Wells,” Journal of Petroleum Technology (June 1964), p619-22. Meyer, H.I. and Garder, A.O., 1954, “Mechanics of Two Immiscible Fluids in Porous Media,” Journal of Applied Physics, (November 1954) 25, No. 11, 1400. Mills, R.A.R., Gaymard, R., 1996, “New Application for Wellbore Progressing Cavity Pumps,” paper SPE 35541, Intl. Petroleum Conference & Exhibition of Mexico, Villahermosa, Mexico, March 5-7. Montgomery, D.C., 1997, “Design and Analysis of Experiments,” 4th ed., John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York City. Mower, L.N., Lea, J.F., Beauregard, E., and Ferguson, P. L., 1985, “Defining the Characteristics and Performance of Gas Lift Plungers,” paper SPE 14344, SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Las Vegas, NV, Sept. 22-25. Muskat, M.,1982, “Flow of Homogeneous Fluids,” International Human Resources Development, Boston, p687-692. Muskat, M. and Wyckoff, R.D., 1935, “An approximate Theory of Water Coning in Oil Production,” AIME Transactions, Vol. 114, 144-163. Myers, R. H. and Montgomery, D. C., 2002, “Response Surface Methodology: Process and Product optimization Using Designed Experiments,” 2nd ed., John Wiley & Sons, New York. National Energy Board of Canada, 1995, “Unconnected Gas Supply Study: Phase I – Evaluation of Unconnected Reserves in Alberta,” NEB Energy Resources Branch, January. Neves, T.R., and Brimhall, R.M., 1989, “Elimination of Liquid Loading in LowProductivity Gas Wells,” paper SPE 18833, SPE Production Operation Symposium, Oklahoma City, OK, March 13-14. 170 Nichol, J.R., and Marsh, J., 1997, “Downhole Gas/Water Separation: Engineering Assessment and Field Experience,” paper SPE 38828, SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, San Antonio, TX, October 5-8. Nosseir, M.A., Darwich, T.A., Sayyouh, M.H., and El Sallaly, M., 2000, “a New Approach for Accurate Prediction of Loading in Gas Wells Under Different Flowing Conditions,” SPE Prod. & Facilities 15 (4), November, p241-46. Pascal H., Quillian, R.G., Kingston, J., 1980, “Analysis of Vertical Fracture Length and Non-Darcy Flow Coefficient Using Variable Rate Tests,” paper SPE 9438 Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Dallas, Sept. 21-24. Petalas, N & Aziz, K, 1997, “A Mechanistic Model for Stabilized Multiphase Flow in Pipe,” Petroleum Engineering Department, Stanford University, August 1997. Pigott, M.J., Parker, M.H., Mazzanti, D.V., Dalrymple, L.V., Cox, D.C., and Coyle, R.A., 2002, “Wellbore Heating To Prevent Liquid Loading,” paper SPE 77649, SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, San Antonio, TX, 29 September-2 October. Putra, S.A., and Christiansen R.L., 2001, “Design of Tubing Collar Inserts for Producing Gas Wells Bellow Their Critical Rate,” paper SPE 71554, SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, New Orleans, Louisiana, September 30- October 3. R Core Team, 2000, “The R Reference Index: Version 1.1.1.” Rangel-German, E., and Samaniego V., F, 2000, “On the determination of the skin factor and the turbulence term coefficient through a single constant gas pressure test,” J. of Pet. Sci. & Eng., (2000) 26, p121. Randolph, P.L., Hayden, C.G., and Anhaiser, J.L., 1991, “Maximizing Gas Recovery From Strong Water Drive Reservoir,” paper SPE 21486, SPE Gas Technology Symposium, Houston, TX, January 23-25. Rogers, L.A., 1984, “Test of Secondary Gas Recovery by Coproduction of Gas and Water From Mt. Selman Field, TX,” paper SPE 12865, SPE/DOE/GRI Unconventional Gas Recovery Symposium, Pittsburgh, PA, May 13-15. Roman, S., 1999, “Writing Excel Macros,” O'Reilly and Associates, Sebastopol, California, p529. Rosina, L, 1983, “A Study of Plunger Lift Dynamics,” MS Thesis, The University of Tulsa, Tulsa, OK. Rudolph J., and Miller J., 2001 “Downhole Produced Water Disposal Improves Gas Rate,” GasTIPS, pp 21-24, Fall 2001. 171 Sacks, J., S. B. Schiller, and W. J. Welch, 1989, “Designs for Computer Experiments,” Technometrics (1989) 31 No. 1, 41-47. Saidikowski, R.M., 1979, “Numerical Simulations of the Combined Effects of Wellbore Damage and Partial Penetration,” Paper SPE 8204 Annual Fall Technical Conference and Exhibition, Nevada, Sep 23-26. Saleh, S., and Al-Jamae’y, M., 1997, “Foam-Assisted Liquid Lifting in Low Pressure Gas Wells,” paper SPE 37425, Production Operations Symposium, Oklahoma City, Marc 9-11. Scheidegger, A.E., 1974, “The Physics of Flow through Porous Media,” University of Toronto Press, Toronto. Schlumberger: VFPi User Guide 98A, 1998, Sclumberger GeoQuest, App. N, pN-1 to N8. Schlumberger Technology Co., 1997, Eclipse 100 Reference Manual, Sclumberger GeoQuest, unpaginated. Schneider, T.S., and Mackey, Jr. V., 2000, “Plunger Lift Beneficts Bottom Line for a Southeast New Mexico Operator,” paper SPE 59705, SPE Permian Basin Oil and Gas Recovery Conference, Midland, TX, March 21-23. Schols, R.S., 1972, “An Empirical Formula for the Critical Oil Production Rate,” Erdoel Erdgas, Z, Vol 88, No 1, p6-11, January 1972. Schwall, G.H., 1989, “Case Histories: Plunger Lift Boosts Production in Deep Appalachian Gas Wells,” paper SPE 18870, SPE Production Operations Symposium, Oklahoma City, OK, March 13-14. Scott, W.S., and Hoffman, C.E., 1999, “An Update On Use of Coiled Tubing for Completion and Recompletion Strings,” paper SPE 57447, SPE Eastern Regional Meeting, Charleston, West Virginia, October 21-22. Shirman, E.I., Wojtanowicz, A.K., 1997, “Water Coning Reversal Using Downhole Water Sink Theory and Experimental Study,” paper SPE 38792, SPE Annual Technical Conference & Exhibition, San Antonio, TX, Oct. Shirman, E.I., Wojtanowicz, A.K., 1998 “More Oil With Less Water Using Downhole Water Sink Technology: A Feasibility Study,” paper SPE 49052 73rd SPE Annual Technical Conference & Exhibition, New Orleans, LA, Oct. 27-30. Silverman, S.A., Butler, W., Ashby, T., and Snider, K., 1997, “Concentric Capillary Tubing Boosts Production of Low-Pressure Gas Wells,” Hart’s Petroleum Engineer International, Vol. 70, No 10, October 1997, p71-73. 172 Smith, R.V., 1990, “Practical Natural Gas Engineering,” 2nd Edition, PennWell Books, Tulsa, 1990. Stephenson G.B., Rouen R.P., Rosenzweig M.H., 2000, “Gas-Well Dewatering: A Coordinated Approach,” paper SPE 58984, 2000 SEP International Petroleum Conference and Exibition, Villahermosa, Mexico, February 1-3. Sutton, R.P., Cox, S. A., Williams Jr., E. G., Stoltz, R.P., and Gilbert, J.V., 2003, “Gas Well Performance at Subcritical Rates,” paper SPE 80887, SPE Production and Operations Symposium, Oklahoma City, OK, March 22-25. Swisher, M.D. and Wojtanowicz, A.K., 1995, “In Situ-Segregated Production of Oil and Water – A Production Method with Environmental Merit: Field Application,” paper SPE 29693 SPE/EPA Exploration & Production Environmental Conference, Houston, TX, March 27-29. Swisher, M.D. and Wojtanowicz, A.K., 1995, “New Dual Completion Method Eliminates Bottom Water Coning,” paper SPE 30697, SPE Annual Technical Conference & Exhibition, Dallas, TX, Oct. 22-25. Thauvin, F., and Mohanty, K.K., 1998, “Network Modeling of Non-Darcy Flow through Porous Media,” Transport in Porous Media, 31, p19-37. Timble, A.E., DeRose, W.E., 1976, “Field Application of Water-Conning Theory to Todhunters Lake Gas Field,” Paper SPE 5873, SPE-AIME 46th Annual California Regional Meeting, Long Beach, April 8-9. Tiss, M. and Evans, R.D., 1989, “Measurement and Correlation of Non-Darcy Flow Coefficient in Consolidated Porous Media,” J. Petroleum Science and Engineering, Vol. 3, Nos. 1-2, p19-33. Turner, R.G, Hubbard, M.G., and Dukler, A.E., 1969, “Analysis and Prediction of Minimum Flow Rates for the Continuous Removal of Liquid from Gas Wells,” J. Pet. Tech. (Nov., 1969) 1475-82. Umnuayponwiwat, S., Ozkan, E., Pearson, C.M., and Vincent, M., 2000, “Effect of nonDarcy flow on the interpretation of transient pressure responses of hydraulically fractured wells,” paper SPE 63176 presented at the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Dallas, October 1-4. Upchurch, E.R., 1987, “Expanding the Range for Predicting Critical Flowrates of Gas Well Producing From Normally Pressured Water Drive Reservoir,” paper SPE 16906, SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Dallas, September 2730. Vosika, J.L., 1983, “Use of Foaming Agents to Alleviate Loading in Great Green River TFG Wells,” paper SPE/DOE 11644, SPE/DOE Symposium on Low Permeability, Denver, Colorado, March 14-16. 173 Weeks, S., 1982, “Small-Diameter Concentric Tubing Extends Economic Life of High Water/Sour Gas Edwards Producers,” Journal of Petroleum Technology, (September, 1982), p1947-50. White, C., 2002, “PETE-4052 Well Testing,” Syllabus, Louisiana State University, Craft & Hawkins Petroleum Engineering Department. White, G.W., 1982, “Combine Gas Lift, Plunger to Increase Production Rate,” World Oil (Nov. 1982), p69-74. White, C.D., and Royer, S.A., 2003, “Experimental Design as a Framework for Reservoir Studies,” paper SPE 79676, SPE Reservoir Simulation Symposium, Houston, February 3-5. White, C.D., Willis, B.J., Narayanan, K., and Dutton, S.P., 2001, “Identifying and Estimating Significant Geologic Parameters with Experimental Design,” SPEJ (September 2001) 311-324. Wiggins, M. L., Nguyen, S.H., and Gasbarri, S., 1999, “Optimizing Plunger Lift Operations in Oil and Gas Wells,” paper SPE 52119, SPE Mid-Continent Operations Symposium, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, March 28-31. Wojtanowicz, A.K., Shirman, E.I., Kurban, H., 1999, “Downhole Water Sink (DWS) Completion Enhance Oil Recovery in Reservoir With Water Coning Problems,” paper SPE 56721, SPE Annual Technical Conference & Exhibition, Houston, TX, Oct. 3-6. Xu, R., Yang, L., 1995, “A New Binary Surfactant Mixture Improved Foam Performance in Gas Well Production,” paper SPE 29004, International Symposium on Oilfield Chemistry, San Antonio, TX, February 14-17. 174 APPENDIX A ANALYTICAL COMPARISON OF WATER CONING IN OIL AND GAS WELLS 1. Analytical comparison of water coning in oil and gas wells before water breakthrough The pressure drop to generate a stable cone height of 20 feet in the oil-water system is: ∆P = 0.052( ρ w − ρ o )h ∆P = 0.052(8.5 − 6.6) * 20 ∆P = 2 psi The oil production rate for this pressure drop assuming pseudo-steady-state conditions is: qo = 0.00708 * hko ( pe − p1 ) µBo * [ln(0.472re / rw ) + S ] Assuming that the skin effect (S) is generated only by the partial penetration (skin effects generated by drilling mud and perforation geometry are zero). After Saidikowski (1979), S can be estimated from the equation: h h S = t − 1 ln t h p rw kH − 2 kV Where: ht is the reservoir thickness, hp is the completed interval, rw is the wellbore radius, kH is the horizontal permeability, and kV is the vertical permeability. 50 50 For this example: S = − 1 ln − 2 = 3.9 20 0.5 The oil flow rate is: 175 0.00708 * 50 * 100(2000 − 1998) 0.9 *1.1 * [ln (0.472 *1000 / 0.5) + 3.9] q o = 6.7 STB / D qo = Next, it was assumed that the reservoir has gas instead of oil. Then, the value of the pressure drop and the gas production rate, necessary to generate the same stable cone height generated for oil-water systems (20 ft), was calculated. The pressure drop to generate a 20 ft high stable cone is: ∆P = 0.052( ρ w − ρ g )h ∆P = 0.052(8.5 − 0.8) * 20 ∆P = 8 psi The gas production rate for this pressure drop at pseudo-steady-state conditions, neglecting Non-Darcy flow term, is: qg = 6.88 * 10 −7 * hk g ( p e2 − p12 ) TZµ * [ln(0.472 * re / rw ) + S ] Assuming that the skin effect (S) is generated only by the partial penetration (skin effects generated by drilling mud and perforation geometry are zero). From the previous calculation, S = 3.9 The gas flow rate is: 6.88 * 10 −7 * 50 * 100 * (2000 2 − 1992 2 ) 572 * 0.84 * 0.017 * [ln(0.472 * 1000 / 0.5) + 3.9] q g = 1.25 MMSCF / D qg = 176 2. Analytical comparison of water coning in oil and gas wells after water breakthrough well oil / gas Pw h Pe ye y=? water r Figure A-1 r Theoretical model used to compare water coning in oil and gas wells after breakthrough. Assumptions: radial flow, isothermal conditions, porosity, and permeability are the same in the gas and water zone, and steady state conditions. For gas-water system: Qg = 2πr (h − y )kφp ∂p ………………………………………………………..(A-1) µg ∂r Qw = 2πrykφ ∂p …………………………………………………..…………(A-2) µ w ∂r R= Qg Qw = µ w (h − y ) p µg y At re ⇒ R = Qg Qw ……………………………………………………….(A-3) µ w Pe (1 − ( y e / h)) = µ g ( y e / h) …………………………….………...(A-4) Rearranging equation (A-1): 177 Qg µ g = rhp 2πφk ∂p ∂p − ryp …………………………………………………...…(A-6) ∂r ∂r Rearranging equation (A-2): Qw µ w ∂p = ry ………………………………..…………………………..…(A-7) 2πφk ∂r Substituting (A-7) in (A-6): Qg µ g = rhp 2πφk ∂p Q w µ w p …………………………………….……….…….(A-8) − ∂r 2πφk Defining some constants: a= b= Qg µ g 2πφkh ……………………………….….(A-9) Qw µ w ……………………………...….(A-10) 2πφkh Substituting (A-9) and (A-10) in (A-8): a = rp ∂p − bp ……………………………………………………..………(A-11) ∂r Rearranging equation (A-11) gives: 1 p ∂r b ∂p = r a + p b …………………………………………..…….……..(A-12) Integrating (A-12): pe r e p ∂r (1 / b) ∂p = ………………..………………………….…..(A-13) [(a / b) + p ] r r p ∫ ∫ The solution for (A-13) is: r 1 a p + a / b ……..……………………………….. (A-14) ln e = p e − p − ln e b p + a / b r b The ratio (a/b) may be found dividing equation (A-9) by equation (A-10): a Qg µ g = b Qw µ w …………………………………………………..………………(A-15) 178 From equation (A-4): Qg µ g Qw µ w = 1 − ( y e / h) a pe = b ( y e / h) ………………………………………..…………(A-16) The ratio (1/b) can be found from equation (A-14) at the wellbore (r = rw ⇒ p = pw): r ln e 1 rw = …………………………………………(A-17) b a p e + (a / b) ( p e − p w ) − ln b p w + (a / b) Finally, y may be solved from equation (A-3) and (A-15): Qg µ g Qw µ w = (h − y ) p a = y b ⇒ y= hp [(a / b) + p] ……………………………………..(A-18) Repeating the same analysis for the oil-water system: Qo = 2πr (h − y )kφ ∂p …………………………………………….……..…..(A-19) µo ∂r Qw = 2πrykφ ∂p ………………………………………………………..…..(A-20) µ w ∂r R= Qo µ w (h − y ) = ………………………………………………………...(A-21) Qw µo y If: a = Qo µ o Q µ (h − y e ) a Q µ , and b = w w , then = o o = ………….……..(A-22) 2πφkh 2πφkh b Qw µ w ye Rearranging Eq. A-19: Qo µ o ∂p ∂p = rh − ry ………………………...…..(A-23) ∂r 2πφk ∂r Integrating (A-23): a re ∂r 1 pe = ∂p …………………………………………………….(A-24) + 1 b p b r r ∫ ∫ 1 ( p e − p ) r b ln e = ……………………………………………….……..(A-25) a r + 1 b 179 Solving for y: y = h a + 1 b ……………………………………….……..(A-26) 180 APPENDIX B EXAMPLE ECLIPSE DATA DECK FOR COMPARISON OF WATER CONING IN OIL AND GAS WELLS AFTER WATER BREAKTHROUGH GAS-WATER MODEL Runspec Title Comparison of Water Coning in Oil and Gas Wells After Water Breakthrough Gas-Water Model MESSAGES 6* 3*5000 / Radial Dimens -NR Theta NZ 26 1 128 / Gas Water Field Regdims 2 / Welldims -- Wells Con Group Well in group 2 100 1 2 / VFPPDIMS 10 10 10 10 0 2 / Start 1 'Jan' 2002 / Nstack 300 / Unifout ------------------------------------------------------------Grid Tops 26*5000 / Inrad 0.333 / DRV 0.4170 0.3016 0.4229 0.5929 0.8313 1.166 1.634 2.292 3.213 4.505 6.317 8.857 12.42 17.41 24.41 34.23 48.00 67.30 94.36 132.3 185.5 260.1 364.7 511.4 717.0 2500 / DZ 3120*0.5 182*5 26*550 / Equals 'DTHETA' 360 / 'PERMR' 10 / 'PERMTHT' 100 / 'PERMZ' 5 / 'PORO' 0.25 / 'PORO' 0 26 26 1 1 1 100 / 'PORO' 10 26 26 1 1 101 128 / 181 / INIT --RPTGRID --1 / ------------------------------------------------------------PROPS DENSITY 45 64 0.046 / ROCK 2500 10E-6 / PVTW 2500 1 2.6E-6 0.68 0 / PVZG -- Temperature 120 / -- Press Z Visc 100 0.989 0.0122 300 0.967 0.0124 500 0.947 0.0126 700 0.927 0.0129 900 0.908 0.0133 1100 0.891 0.0137 1300 0.876 0.0141 1500 0.863 0.0146 1700 0.853 0.0151 1900 0.845 0.0157 2100 0.840 0.0163 2300 0.837 0.0167 2500 0.837 0.0177 2700 0.839 0.0184 3200 0.844 0.0202 / --Saturation Functions --Sgc = 0.20 --Krg @ Swir = 0.9 --Swir = 0.3 --Sorg = 0.0 SGFN --Using Honarpour Equation 71 -Sg Krg Pc 0.00 0.000 0.0 0.10 0.000 0.0 0.20 0.020 0.0 0.30 0.030 0.0 0.40 0.081 0.0 0.50 0.183 0.0 0.60 0.325 0.0 0.70 0.900 0.0 / SWFN --Using Honarpour Equation 67 -Sw Krw Pc 0.3 0.000 0.0 0.4 0.035 0.0 0.5 0.076 0.0 0.6 0.126 0.0 0.7 0.193 0.0 0.8 0.288 0.0 0.9 0.422 0.0 1.0 1.000 0.0 / 182 ------------------------------------------------------------REGIONS Fipnum 2600*1 728*2 / ------------------------------------------------------------SOLUTION EQUIL 5000 1500 5050 0 5050 0 / RPTSOL 6* 2 2 / ------------------------------------------------------------SUMMARY SEPARATE RPTONLY WGPR / WWPR / WBHP / WTHP / WGPT / WWPT / WBP / RGIP / RPR 1 2 / TCPU ------------------------------------------------------------SCHEDULE NOECHO INCLUDE 'WELL-5000-VI.VFP' / ECHO RPTSCHED 6* 2 / RPTRST 4 / restarts once a year TUNING 0.0007 30.4 0.0007 0.0007 1.2 / 3* 0.00001 3* 0.0001 / 2* 500 1* 100 / WELSPECS 'P' 'G' 1 1 5000 'GAS' 2* 'STOP' 'YES' / / COMPDAT 'P' 1 1 1 100 'OPEN' 2* 0.666 / / WCONPROD 'P' 'OPEN' 'THP' 6* 300 1 / / WECON 'P' 1* 1000 3* 'WELL' 'YES' / / 183 TSTEP 6*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 35*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 End / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / 184 ECLIPSE VFP INCLUDED FILE: WELL-5000-VI VFPPROD 1 5.00000E+003 'GAS' 'WGR' 'OGR' 'THP' '' 'FIELD' 'BHP'/ 5.00000E+002 1.00000E+004 3.00000E+002 0.00000E+000 4.00000E-001 0.00000E+000 0.00000E+000 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 3 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 3 2 1 1 1 3 1 1 2 3 1 1 3 3 1 1 1 4 1 1 2 4 1 1 3 4 1 1 1 5 1 1 2 5 1 1 3 5 1 1 1 6 1 1 2 6 1 1 3 6 1 1 1 7 1 1 2 7 1 1 3 7 1 1 1 8 1 1 2 8 1 1 3 8 1 1 1.00000E+003 1.50000E+004 5.00000E+002 5.00000E-002 6.00000E-001 / / 3.37024E+002 9.16800E+002 5.59849E+002 1.01422E+003 7.84870E+002 1.14823E+003 1.00767E+003 1.17821E+003 1.33083E+003 1.26153E+003 1.63681E+003 1.38041E+003 1.02840E+003 1.40325E+003 1.35532E+003 1.48036E+003 1.66413E+003 1.59380E+003 1.06877E+003 1.79136E+003 1.40292E+003 1.87547E+003 1.71647E+003 2.00566E+003 1.14745E+003 2.63140E+003 1.49259E+003 2.70978E+003 1.81241E+003 2.82769E+003 1.22282E+003 3.33657E+003 1.57486E+003 3.40719E+003 1.89758E+003 3.51185E+003 1.29426E+003 3.93384E+003 1.65009E+003 4.00224E+003 1.97324E+003 4.09229E+003 1.36153E+003 4.54574E+003 1.71853E+003 4.60380E+003 2.04060E+003 4.68526E+003 3.00000E+003 1.80000E+004 7.00000E+002 1.00000E-001 8.00000E-001 3.45916E+002 1.30649E+003 5.65127E+002 1.37324E+003 7.88564E+002 1.47144E+003 6.85715E+002 1.69683E+003 1.14235E+003 1.75038E+003 1.43549E+003 1.83132E+003 7.98358E+002 2.01561E+003 1.17999E+003 2.06380E+003 1.46993E+003 2.13846E+003 9.06174E+002 2.60038E+003 1.23965E+003 2.65034E+003 1.53687E+003 2.72983E+003 1.03248E+003 3.81908E+003 1.35495E+003 3.86469E+003 1.66240E+003 3.93860E+003 1.13624E+003 4.76408E+003 1.46356E+003 4.80311E+003 1.77592E+003 4.86696E+003 1.23434E+003 5.78065E+003 1.56415E+003 5.81806E+003 1.87771E+003 5.87715E+003 1.32752E+003 6.91460E+003 1.65684E+003 6.95034E+003 1.96914E+003 7.00651E+003 185 5.00000E+003 / / 2.00000E-001 1.00000E+000 4.25316E+002 1.53942E+003 6.15848E+002 1.59511E+003 8.24884E+002 1.67903E+003 5.26979E+002 2.00157E+003 7.95789E+002 2.04461E+003 1.08259E+003 2.11135E+003 6.46858E+002 2.37484E+003 9.33680E+002 2.41335E+003 1.24089E+003 2.47443E+003 8.40372E+002 3.08950E+003 1.14544E+003 3.12890E+003 1.43807E+003 3.19348E+003 1.14282E+003 4.60402E+003 1.42442E+003 4.64024E+003 1.68147E+003 4.70113E+003 1.39809E+003 5.69293E+003 1.65458E+003 5.72329E+003 1.89757E+003 5.77621E+003 1.62877E+003 7.03960E+003 1.86048E+003 7.06883E+003 2.09286E+003 7.11864E+003 1.83827E+003 8.57619E+003 2.04934E+003 8.60433E+003 2.27214E+003 8.65222E+003 / 5.47796E+002 / 7.04360E+002 / 8.91574E+002 / 6.66317E+002 / 8.23119E+002 / 1.05816E+003 / 7.92196E+002 / 9.70272E+002 / 1.22716E+003 / 1.03062E+003 / 1.22814E+003 / 1.50399E+003 / 1.50309E+003 / 1.68890E+003 / 1.92590E+003 / 1.90174E+003 / 2.07013E+003 / 2.26855E+003 / 2.24629E+003 / 2.39607E+003 / 2.57229E+003 / 2.56051E+003 / 2.69480E+003 / 2.85658E+003 / EXAMPLE ECLIPSE DATA DECK FOR COMPARISON OF WATER CONING IN OIL AND GAS WELLS AFTER WATER BREAKTHROUGH OIL-WATER MODEL Runspec Title Comparison of Water Coning in Oil and Gas Well After Water Breakthrough Oil-Water Model MESSAGES 6* 3*5000 / Radial Dimens -NR Theta NZ 26 1 128 / NONNC Oil --Gas --Disgas Water Field Regdims 2 / Welldims -- Wells Con Group Well in group 2 100 1 2 / VFPPDIMS 10 10 10 10 0 2 / Start 1 'Jan' 2002 / Nstack 300 / Unifout ------------------------------------------------------------Grid Tops 26*5000 / Inrad 0.333 / DRV 0.4170 0.3016 0.4229 0.5929 0.8313 1.166 1.634 2.292 3.213 4.505 6.317 8.857 12.42 17.41 24.41 34.23 48.00 67.30 94.36 132.3 185.5 260.1 364.7 511.4 717.0 2500 / DZ 3120*0.5 182*5 26*550 / Equals 'DTHETA' 360 / 'PERMR' 10 / 'PERMTHT' 100 / 'PERMZ' 5 / 'PORO' 0.25 / 'PORO' 0 26 26 1 1 1 100 / 186 'PORO' 10 26 26 1 1 101 128 / / INIT --RPTGRID --1 / ------------------------------------------------------------PROPS DENSITY 45 64 0.046 / ROCK 2500 10E-6 / PVTW 2500 1 2.6E-6 0.68 0 / SWOF -- Sw 0.27 0.35 0.40 0.45 0.50 0.55 0.60 0.65 0.70 Krw 0.000 0.012 0.032 0.061 0.099 0.147 0.204 0.271 0.347 Krow 0.900 0.596 0.438 0.304 0.195 0.110 0.049 0.012 0.000 Pcow 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 / PVCDO 2500 1.15 1.5E-5 0.5 0 / RSCONST 0.379 1000 / ------------------------------------------------------------REGIONS Fipnum 2600*1 728*2 / ------------------------------------------------------------SOLUTION EQUIL 5000 3000 5050 0 100 0 1 1 2* / RPTSOL 6* 2 2 / ------------------------------------------------------------SUMMARY SEPARATE RPTONLY WOPR / WWPR / WBHP / WTHP / WOPT / WWPT / WBP / 187 RGIP / RPR 1 2 / TCPU ------------------------------------------------------------SCHEDULE NOECHO --INCLUDE --'WELL-5000-VI.VFP' / ECHO RPTSCHED 6* 2 / RPTRST 4 / restarts once a year TUNING 0.0007 30.4 0.0007 0.0007 1.2 / 3* 0.00001 3* 0.0001 / 2* 500 1* 100 / WELSPECS 'P' 'G' 1 1 5000 'GAS' 2* 'STOP' 'YES' / / COMPDAT 'P' 1 1 1 100 'OPEN' 2* 0.666 / / WCONPROD 'P' 'OPEN' 'ORAT' 630 / / WECON 'P' 2* 1.0 2* 'WELL' 'YES' / / TSTEP 6*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 35*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / 188 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 End / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / 189 APPENDIX C EXAMPLE ECLIPSE DATA DECK FOR EFFECT OF VERTICAL PERMEABILITY ON WATER CONING Runspec Title Effect of Vertical Permeability on Water Coning Vertical Permeability equal to 30% Horizontal Permeability MESSAGES 6* 3*5000 / Radial Dimens -NR Theta NZ 26 1 110 / Gas Water Field Regdims 2 / Welldims -- Wells Con 1 100 / VFPPDIMS 10 10 10 10 0 1 / Start 1 'Jan' 1998 / Nstack 100 / Unifout ------------------------------------------------------------Grid Tops 26*5000 / Inrad 0.333 / DRV 0.4170 0.3016 0.4229 0.5929 0.8313 1.166 1.634 2.292 3.213 4.505 6.317 8.857 12.42 17.41 24.41 34.23 48.00 67.30 94.36 132.3 185.5 260.1 364.7 511.4 717.0 2500 / DZ 2600*1 234*10 26*110 / Equals 'DTHETA' 360 / 'PERMR' 10 / 'PERMTHT' 10 / 'PERMZ' 3 / 'PORO' 0.25 / 'PORO' 0 26 26 1 1 1 100 / 'PORO' 10 26 26 1 1 101 110 / / 190 INIT --RPTGRID --1 / ------------------------------------------------------------PROPS DENSITY 45 64 0.046 / ROCK 2500 10E-6 / PVTW 2500 1 2.6E-6 0.68 0 / PVZG -- Temperature 120 / -- Press Z Visc 100 0.989 0.0122 300 0.967 0.0124 500 0.947 0.0126 700 0.927 0.0129 900 0.908 0.0133 1100 0.891 0.0137 1300 0.876 0.0141 1500 0.863 0.0146 1700 0.853 0.0151 1900 0.845 0.0157 2100 0.840 0.0163 2300 0.837 0.0167 2500 0.837 0.0177 2700 0.839 0.0184 / --Saturation Functions --Sgc = 0.20 --Krg @ Swir = 0.9 --Swir = 0.3 --Sorg = 0.0 SGFN --Using Honarpour Equation 71 -Sg Krg Pc 0.00 0.000 0.0 0.20 0.000 0.0 0.30 0.020 0.0 0.40 0.081 0.0 0.50 0.183 0.0 0.60 0.325 0.0 0.70 0.900 0.0 / SWFN --Using Honarpour Equation 67 -Sw Krw Pc 0.3 0.000 0.0 0.4 0.035 0.0 0.5 0.076 0.0 0.6 0.126 0.0 0.7 0.193 0.0 0.8 0.288 0.0 0.9 0.422 0.0 1.0 1.000 0.0 / 191 ------------------------------------------------------------REGIONS Fipnum 2600*1 260*2 / ------------------------------------------------------------SOLUTION EQUIL 5000 2300 5100 0 5100 0 / RPTSOL 6* 2 2 / ------------------------------------------------------------SUMMARY SEPARATE RPTONLY WGPR / WWPR / WBHP / WTHP / WGPT / WWPT / WBP / RGIP / RPR 1 2 / TCPU ------------------------------------------------------------SCHEDULE NOECHO INCLUDE 'WELL-5000-VI.VFP' / ECHO RPTSCHED 6* 2 / RPTRST 4 / restarts once a year TUNING 0.0007 30.4 0.0007 0.0007 1.2 / 3* 0.00001 3* 0.0001 / 2* 100 / WELSPECS 'P' 'G' 1 1 5000 'GAS' 2* 'STOP' 'YES' / / COMPDAT 'P' 1 1 1 30 'OPEN' 2* 0.666 / / WCONPROD 'P' 'OPEN' 'THP' 5* 550 500 1 / / 192 WECON 'P' 1* / TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 End 1220 4* 'YES' / / / / / / / / / / / / / 193 EXAMPLE ECLIPSE DATA DECK FOR EFFECT OF AQUIFER SIZE ON WATER CONING Runspec Title Effect of Aquifer Size on Water Coning VAD equal to 519 MESSAGES 6* 3*5000 / Radial Dimens -NR Theta NZ 26 1 110 / Gas Water Field Regdims 2 / Welldims -- Wells Con 1 100 / VFPPDIMS 10 10 10 10 0 1 / Start 1 'Jan' 1998 / Nstack 100 / Unifout ------------------------------------------------------------Grid Tops 26*5000 / Inrad 0.333 / DRV 0.4170 0.3016 0.4229 0.5929 0.8313 1.166 1.634 2.292 3.213 4.505 6.317 8.857 12.42 17.41 24.41 34.23 48.00 67.30 94.36 132.3 185.5 260.1 364.7 511.4 717.0 2500 / DZ 2600*1 234*10 26*410 / Equals 'DTHETA' 360 / 'PERMR' 10 / 'PERMTHT' 10 / 'PERMZ' 1 / 'PORO' 0.25 / 'PORO' 0 26 26 1 1 1 100 / 'PORO' 10 26 26 1 1 101 110 / / INIT --RPTGRID --1 / 194 ------------------------------------------------------------PROPS DENSITY 45 64 0.046 / ROCK 2500 10E-6 / PVTW 2500 1 2.6E-6 0.68 0 / PVZG -- Temperature 120 / -- Press Z Visc 100 0.989 0.0122 300 0.967 0.0124 500 0.947 0.0126 700 0.927 0.0129 900 0.908 0.0133 1100 0.891 0.0137 1300 0.876 0.0141 1500 0.863 0.0146 1700 0.853 0.0151 1900 0.845 0.0157 2100 0.840 0.0163 2300 0.837 0.0167 2500 0.837 0.0177 2700 0.839 0.0184 / --Saturation Functions --Sgc = 0.20 --Krg @ Swir = 0.9 --Swir = 0.3 --Sorg = 0.0 SGFN --Using Honarpour Equation 71 -Sg Krg Pc 0.00 0.000 0.0 0.20 0.000 0.0 0.30 0.020 0.0 0.40 0.081 0.0 0.50 0.183 0.0 0.60 0.325 0.0 0.70 0.900 0.0 / SWFN --Using Honarpour Equation 67 -Sw Krw Pc 0.3 0.000 0.0 0.4 0.035 0.0 0.5 0.076 0.0 0.6 0.126 0.0 0.7 0.193 0.0 0.8 0.288 0.0 0.9 0.422 0.0 1.0 1.000 0.0 / ------------------------------------------------------------REGIONS Fipnum 195 2600*1 260*2 / ------------------------------------------------------------SOLUTION EQUIL 5000 2300 5100 0 5100 0 / RPTSOL 6* 2 2 / ------------------------------------------------------------SUMMARY SEPARATE RPTONLY WGPR / WWPR / WBHP / WTHP / WGPT / WWPT / WBP / RGIP / RPR 1 2 / TCPU ------------------------------------------------------------SCHEDULE NOECHO INCLUDE 'WELL-5000-VI.VFP' / ECHO RPTSCHED 6* 2 / RPTRST 4 / restarts once a year TUNING 0.0007 30.4 0.0007 0.0007 1.2 / 3* 0.00001 3* 0.0001 / 2* 100 / WELSPECS 'P' 'G' 1 1 5000 'GAS' 2* 'STOP' 'YES' / / COMPDAT 'P' 1 1 1 30 'OPEN' 2* 0.666 / / WCONPROD 'P' 'OPEN' 'THP' 5* 550 500 1 / / WECON 'P' 1* 1220 4* 'YES' / / 196 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 End / / / / / / / / / / / / 197 EXAMPLE ECLIPSE DATA DECK FOR EFFECT OF FLOW BEHIND CASING ON WATER CONING Runspec Title Effect of Flow Behind Casing Channel Size 1.3 inches (Permeability in the first grid 1,000,000 md) Channel Initially in the Water Zone 6* 3*5000 / Radial Dimens -NR Theta NZ 26 1 110 / Gas Water Field Regdims 2 / Welldims -- Wells Con 1 100 / VFPPDIMS 10 10 10 10 0 1 / Start 1 'Jan' 1998 / Nstack 100 / Unifout ------------------------------------------------------------Grid Tops 26*5000 / Inrad 0.333 / DRV 0.4170 0.3016 0.4229 0.5929 0.8313 1.166 1.634 2.292 3.213 4.505 6.317 8.857 12.42 17.41 24.41 34.23 48.00 67.30 94.36 132.3 185.5 260.1 364.7 511.4 717.0 2500 / DZ 2600*1 234*10 26*110 / Equals 'DTHETA' 360 / 'PERMR' 100 / 'PERMTHT' 100 / 'PERMZ' 10 / 'PORO' 0.25 / 'PORO' 0 26 26 1 1 1 100 / 'PORO' 10 26 26 1 1 101 110 / 'PERMZ' 1000000 1 1 1 1 1 101 / 'PERMR' 0 1 1 1 1 51 100 / 198 / INIT --RPTGRID --1 / ------------------------------------------------------------PROPS DENSITY 45 64 0.046 / ROCK 2500 10E-6 / PVTW 2500 1 2.6E-6 0.68 0 / PVZG -- Temperature 120 / -- Press Z Visc 100 0.989 0.0122 300 0.967 0.0124 500 0.947 0.0126 700 0.927 0.0129 900 0.908 0.0133 1100 0.891 0.0137 1300 0.876 0.0141 1500 0.863 0.0146 1700 0.853 0.0151 1900 0.845 0.0157 2100 0.840 0.0163 2300 0.837 0.0167 2500 0.837 0.0177 2700 0.839 0.0184 / --Saturation Functions --Sgc = 0.20 --Krg @ Swir = 0.9 --Swir = 0.3 --Sorg = 0.0 SGFN --Using Honarpour Equation 71 -Sg Krg Pc 0.00 0.000 0.0 0.20 0.000 0.0 0.30 0.020 0.0 0.40 0.081 0.0 0.50 0.183 0.0 0.60 0.325 0.0 0.70 0.900 0.0 / SWFN --Using Honarpour Equation 67 -Sw Krw Pc 0.3 0.000 0.0 0.4 0.035 0.0 0.5 0.076 0.0 0.6 0.126 0.0 0.7 0.193 0.0 0.8 0.288 0.0 0.9 0.422 0.0 199 1.0 1.000 0.0 / ------------------------------------------------------------REGIONS Fipnum 2600*1 260*2 / ------------------------------------------------------------SOLUTION EQUIL 5000 2500 5100 0 5100 0 / RPTSOL 6* 2 2 / ------------------------------------------------------------SUMMARY SEPARATE RPTONLY WGPR / WWPR / WBHP / WTHP / WGPT / WWPT / WBP / RGIP / RPR 1 2 / TCPU ------------------------------------------------------------SCHEDULE NOECHO INCLUDE 'GWVFP.VFP' / ECHO RPTSCHED 6* 2 / RPTRST 4 / restarts once a year TUNING 0.0007 30.4 0.0007 0.0007 1.2 / 3* 0.00001 3* 0.0001 / 2* 100 / WELSPECS 'P' 'G' 1 1 5000 'GAS' 2* 'STOP' 'YES' / / COMPDAT 'P' 1 1 1 50 'OPEN' 2* 0.666 / / WCONPROD 200 'P' 'OPEN' 'BHP' 2* 25000 / WECON 'P' 1* 1220 4* 'YES' / / TSTEP 12*30.4 / TSTEP 12*30.4 / TSTEP 6*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / End 2* 2000 201 1* 1 / EXAMPLE IMEX DATA DECK FOR EFFECT OF NON-DARCY FLOW ON WATER CONING Effect of Non-Darcy Effect on Water Coning Non-Darcy Flow Effect Distributed in the Reservoir RESULTS SIMULATOR IMEX RESULTS SECTION INOUT **SS-UNKNOWN ** REGDIMS ** 2 / **SS-ENDUNKNOWN **SS-UNKNOWN ** INIT ** --RPTGRID ** --1 / ** ------------------------------------------------------------**SS-ENDUNKNOWN *DIM *MAX_WELLS 1 *DIM *MAX_LAYERS 100 *********************************************************************** ***** ** ** *IO ** *********************************************************************** ***** *TITLE1 **Effect of Non-Darcy Effect on Water Coning **Non-Darcy Flow Effect Distributed in the Reservoir **-----------------------------------------------------------**SS-NOEFFECT ** MESSAGES ** 6* 3*5000 / **SS-ENDNOEFFECT **-----------------------------------------------------------*INUNIT *FIELD *OUTUNIT *FIELD GRID RADIAL 26 1 110 RW 3.33000000E-1 KDIR DOWN DI IVAR 0.417 0.3016 0.4229 0.5929 0.8313 1.166 1.634 2.292 3.213 4.505 6.317 8.857 12.42 17.41 24.41 34.23 48. 67.3 94.36 132.3 185.5 260.1 364.7 511.4 717. 2500. DJ CON 360. DK KVAR 100*1. 9*10. 210. 202 DTOP 26*5000. RESULTS SECTION GRID RESULTS SECTION NETPAY RESULTS SECTION NETGROSS RESULTS SECTION POR **$ RESULTS PROP POR Units: Dimensionless **$ RESULTS PROP Minimum Value: 0 Maximum Value: 1 POR ALL 2860*1. MOD 1:26 1:1 1:110 = 0.1 26:26 1:1 1:100 = 0 26:26 1:1 101:110 = 1 RESULTS SECTION PERMS **$ RESULTS PROP PERMI Units: md **$ RESULTS PROP Minimum Value: 10 PERMI ALL 2860*1. MOD 1:26 1:1 1:110 = 10 **$ RESULTS PROP PERMJ Units: md **$ RESULTS PROP Minimum Value: 10 PERMJ ALL 2860*1. MOD 1:26 1:1 1:110 = 10 **$ RESULTS PROP PERMK Units: md **$ RESULTS PROP Minimum Value: 1 PERMK ALL 2860*1. MOD 1:26 1:1 1:110 = 1 RESULTS SECTION TRANS RESULTS SECTION FRACS RESULTS SECTION GRIDNONARRAYS CPOR MATRIX 1.E-05 PRPOR MATRIX 2500. Maximum Value: 10 Maximum Value: 10 Maximum Value: 1 RESULTS SECTION VOLMOD RESULTS SECTION SECTORLEASE **$ SECTORARRAY 'SECTOR1' Definition. SECTORARRAY 'SECTOR1' ALL 2600*1 260*0 **$ SECTORARRAY 'SECTOR2' SECTORARRAY 'SECTOR2' ALL 2600*0 260*1 Definition. RESULTS SECTION ROCKCOMPACTION RESULTS SECTION GRIDOTHER RESULTS SECTION MODEL MODEL *BLACKOIL **$ OilGas Table 'Table A' 203 *TRES 120. *PVT *EG 1 ** P Rs Bo EG VisO VisG 14.7 5.51 1.0268 5.05973 1.2801 0.011983 213.72 47.23 1.0414 75.1695 1.0556 0.01216 412.74 97.95 1.0599 148.3052 0.8894 0.0124 611.76 153.78 1.0811 224.457 0.7705 0.01268 810.78 213.36 1.1045 303.5186 0.6824 0.012993 1009.8 275.94 1.1299 385.257 0.6146 0.013335 1208.82 341.06 1.1571 469.289 0.5609 0.013705 1407.84 408.36 1.1859 555.068 0.5173 0.014103 1606.86 477.62 1.2163 641.895 0.481 0.014528 1805.88 548.62 1.2481 728.959 0.4504 0.01498 2004.9 621.23 1.2813 815.4 0.4241 0.01546 2203.92 695.32 1.3158 900.389 0.4013 0.015969 2402.94 770.77 1.3515 983.192 0.3813 0.016508 2601.96 847.5 1.3885 1063.222 0.3636 0.017077 2800.98 925.44 1.4265 1140.054 0.3479 0.017678 3000. 1004.5 1.4657 1213.424 0.3337 0.018313 *DENSITY *OIL 50.0004 *DENSITY *GAS 0.046 *DENSITY *WATER 63.9098 *CO 1.777275E-05 *BWI 1.003357 *CW 2.934065E-06 *REFPW 2500. *VWI 0.658209 *CVW 0 RESULTS SECTION MODELARRAYS RESULTS SECTION ROCKFLUID *********************************************************************** ***** ** ** *ROCKFLUID ** *********************************************************************** ***** *ROCKFLUID *RPT 1 *SWT 0.300000 0.400000 0.500000 0.600000 0.700000 0.800000 0.900000 1.000000 0.000000 0.035000 0.076000 0.126000 0.193000 0.288000 0.422000 1.000000 1.000000 0.000000 0.857142857142857 0.000000 0.714285714285714 0.000000 0.571428571428572 0.000000 0.428571428571429 0.000000 0.285714285714286 0.000000 0.142857142857143 0.000000 0.000000 0.000000 *SGT *NOSWC 0.000000 0.000000 0.200000 0.000000 0.300000 0.020000 0.400000 0.081000 1.000000 0.000000 0.714285714285714 0.000000 0.571428571428572 0.000000 0.428571428571429 0.000000 204 0.500000 0.600000 0.700000 0.183000 0.325000 0.900000 0.285714285714286 0.000000 0.142857142857143 0.000000 0.000000 0.000000 *NONDARCY *FG2 *KROIL *SEGREGATED RESULTS SECTION ROCKARRAYS RESULTS SECTION INIT *********************************************************************** ***** ** ** *INITIAL ** *********************************************************************** ***** *INITIAL **-----------------------------------------------------------**SS-NOEFFECT ** RPTSOL ** 6* 2 2 / ** ------------------------------------------------------------**SS-ENDNOEFFECT **-----------------------------------------------------------*VERTICAL *DEPTH_AVE *WATER_GAS *TRANZONE *EQUIL **$ Data for PVT Region 1 **$ ------------------------------------*REFDEPTH 5000. *REFPRES 2300. *DWGC 5100. RESULTS SECTION INITARRAYS **$ RESULTS PROP PB Units: psi **$ RESULTS PROP Minimum Value: 0 PB CON 0 RESULTS SECTION NUMERICAL *NUMERICAL Maximum Value: 0 RESULTS SECTION NUMARRAYS RESULTS SECTION GBKEYWORDS RUN **SS-UNKNOWN ** RPTRST ** 4 / **SS-ENDUNKNOWN RESTARTS ONCE A YEAR DATE 2002 01 01. **-----------------------------------------------------------**SS-NOEFFECT 205 ** NOECHO **SS-ENDNOEFFECT **-----------------------------------------------------------PTUBE WATER_GAS 1 DEPTH 5000. QG 5.E+05 1.E+06 3.E+06 5.E+06 1.E+07 1.5E+07 1.8E+07 WGR 0 5.E-05 1.E-04 0.0002 0.0004 0.0006 0.0008 0.001 WHP 300. 500. 700. BHPTG 1 1 3.37024000E+02 5.59849000E+02 7.84870000E+02 2 1 1.00767000E+03 1.33083000E+03 1.63681000E+03 3 1 1.02840000E+03 1.35532000E+03 1.66413000E+03 4 1 1.06877000E+03 1.40292000E+03 1.71647000E+03 5 1 1.14745000E+03 1.49259000E+03 1.81241000E+03 6 1 1.22282000E+03 1.57486000E+03 1.89758000E+03 7 1 1.29426000E+03 1.65009000E+03 1.97324000E+03 8 1 1.36153000E+03 1.71853000E+03 2.04060000E+03 1 2 3.45916000E+02 5.65127000E+02 7.88564000E+02 2 2 6.85715000E+02 1.14235000E+03 1.43549000E+03 3 2 7.98357000E+02 1.17999000E+03 1.46993000E+03 4 2 9.06174000E+02 1.23965000E+03 1.53687000E+03 5 2 1.03248000E+03 1.35495000E+03 1.66240000E+03 6 2 1.13624000E+03 1.46356000E+03 1.77592000E+03 7 2 1.23434000E+03 1.56415000E+03 1.87771000E+03 8 2 1.32752000E+03 1.65684000E+03 1.96914000E+03 1 3 4.25316000E+02 6.15848000E+02 8.24883000E+02 2 3 5.26979000E+02 7.95789000E+02 1.08259000E+03 3 3 6.46858000E+02 9.33680000E+02 1.24089000E+03 4 3 8.40372000E+02 1.14544000E+03 1.43807000E+03 5 3 1.14282000E+03 1.42442000E+03 1.68147000E+03 6 3 1.39809000E+03 1.65458000E+03 1.89757000E+03 7 3 1.62877000E+03 1.86048000E+03 2.09286000E+03 8 3 1.83827000E+03 2.04934000E+03 2.27214000E+03 1 4 5.47796000E+02 7.04360000E+02 8.91575000E+02 2 4 6.66316000E+02 8.23118000E+02 1.05816000E+03 3 4 7.92196000E+02 9.70272000E+02 1.22716000E+03 4 4 1.03062000E+03 1.22814000E+03 1.50399000E+03 5 4 1.50309000E+03 1.68890000E+03 1.92590000E+03 6 4 1.90174000E+03 2.07013000E+03 2.26855000E+03 7 4 2.24629000E+03 2.39607000E+03 2.57229000E+03 8 4 2.56051000E+03 2.69480000E+03 2.85658000E+03 1 5 9.16800000E+02 1.01422000E+03 1.14823000E+03 2 5 1.17821000E+03 1.26153000E+03 1.38041000E+03 3 5 1.40325000E+03 1.48036000E+03 1.59380000E+03 4 5 1.79136000E+03 1.87547000E+03 2.00566000E+03 5 5 2.63140000E+03 2.70978000E+03 2.82769000E+03 6 5 3.33657000E+03 3.40719000E+03 3.51185000E+03 7 5 3.93384000E+03 4.00224000E+03 4.09229000E+03 8 5 4.54574000E+03 4.60380000E+03 4.68526000E+03 1 6 1.30649000E+03 1.37324000E+03 1.47144000E+03 2 6 1.69683000E+03 1.75038000E+03 1.83132000E+03 3 6 2.01561000E+03 2.06380000E+03 2.13846000E+03 4 6 2.60038000E+03 2.65034000E+03 2.72983000E+03 5 6 3.81908000E+03 3.86469000E+03 3.93860000E+03 6 6 4.76408000E+03 4.80311000E+03 4.86696000E+03 206 7 8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 6 6 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 GROUP 'G' ATTACHTO 5.78065000E+03 6.91460000E+03 1.53942000E+03 2.00157000E+03 2.37484000E+03 3.08950000E+03 4.60402000E+03 5.69293000E+03 7.03960000E+03 8.57618000E+03 5.81806000E+03 6.95034000E+03 1.59511000E+03 2.04461000E+03 2.41335000E+03 3.12890000E+03 4.64024000E+03 5.72329000E+03 7.06884000E+03 8.60434000E+03 'FIELD' WELL 1 'P' ATTACHTO 'G' PRODUCER 'P' PWELLBORE TABLE 5000. 1 OPERATE MAX STG 1.E+07 CONT OPERATE MIN BHP 14.7 CONT MONITOR MIN STG 1.2E+06 STOP GEOMETRY K 0.333 0.37 1. 5. PERF GEO 'P' 1 1 1 1. OPEN 1 1 2 1. OPEN 1 1 3 1. OPEN 1 1 4 1. OPEN 1 1 5 1. OPEN 1 1 6 1. OPEN 1 1 7 1. OPEN 1 1 8 1. OPEN 1 1 9 1. OPEN 1 1 10 1. OPEN 1 1 11 1. OPEN 1 1 12 1. OPEN 1 1 13 1. OPEN 1 1 14 1. OPEN 1 1 15 1. OPEN 1 1 16 1. OPEN 1 1 17 1. OPEN 1 1 18 1. OPEN 1 1 19 1. OPEN 1 1 20 1. OPEN 1 1 21 1. OPEN 1 1 22 1. OPEN 1 1 23 1. OPEN 1 1 24 1. OPEN 1 1 25 1. OPEN 1 1 26 1. OPEN 1 1 27 1. OPEN 1 1 28 1. OPEN 1 1 29 1. OPEN 1 1 30 1. OPEN 1 1 31 1. OPEN 1 1 32 1. OPEN 1 1 33 1. OPEN 1 1 34 1. OPEN 1 1 35 1. OPEN 207 5.87715000E+03 7.00651000E+03 1.67903000E+03 2.11135000E+03 2.47443000E+03 3.19348000E+03 4.70113000E+03 5.77622000E+03 7.11864000E+03 8.65223000E+03 1 1 36 1. OPEN 1 1 37 1. OPEN 1 1 38 1. OPEN 1 1 39 1. OPEN 1 1 40 1. OPEN 1 1 41 1. OPEN 1 1 42 1. OPEN 1 1 43 1. OPEN 1 1 44 1. OPEN 1 1 45 1. OPEN 1 1 46 1. OPEN 1 1 47 1. OPEN 1 1 48 1. OPEN 1 1 49 1. OPEN 1 1 50 1. OPEN 1 1 51 1. OPEN 1 1 52 1. OPEN 1 1 53 1. OPEN 1 1 54 1. OPEN 1 1 55 1. OPEN 1 1 56 1. OPEN 1 1 57 1. OPEN 1 1 58 1. OPEN 1 1 59 1. OPEN 1 1 60 1. OPEN 1 1 61 1. OPEN 1 1 62 1. OPEN 1 1 63 1. OPEN 1 1 64 1. OPEN 1 1 65 1. OPEN 1 1 66 1. OPEN 1 1 67 1. OPEN 1 1 68 1. OPEN 1 1 69 1. OPEN 1 1 70 1. OPEN 1 1 71 1. OPEN 1 1 72 1. OPEN 1 1 73 1. OPEN 1 1 74 1. OPEN 1 1 75 1. OPEN 1 1 76 1. OPEN 1 1 77 1. OPEN 1 1 78 1. OPEN 1 1 79 1. OPEN 1 1 80 1. OPEN 1 1 81 1. OPEN 1 1 82 1. OPEN 1 1 83 1. OPEN 1 1 84 1. OPEN 1 1 85 1. OPEN 1 1 86 1. OPEN 1 1 87 1. OPEN 1 1 88 1. OPEN 1 1 89 1. OPEN 1 1 90 1. OPEN 1 1 91 1. OPEN 1 1 92 1. OPEN 1 1 93 1. OPEN 208 1 1 94 1. OPEN 1 1 95 1. OPEN 1 1 96 1. OPEN 1 1 97 1. OPEN 1 1 98 1. OPEN 1 1 99 1. OPEN 1 1 100 1. OPEN XFLOW-MODEL 'P' FULLY-MIXED OPEN 'P' TIME 30.4 TIME 60.8 TIME 91.2 TIME 121.6 TIME 152 TIME 182.4 TIME 212.8 TIME 243.2 TIME 273.6 TIME 304 TIME 334.4 TIME 364.8 TIME 395.2 TIME 425.6 TIME 456 TIME 486.4 TIME 516.8 TIME 547.2 TIME 577.6 TIME 608 TIME 638.4 TIME 668.8 TIME 699.2 209 TIME 729.6 TIME 760 TIME 790.4 TIME 820.8 TIME 851.2 TIME 881.6 TIME 912 TIME 942.4 TIME 972.8 TIME 1003.2 TIME 1033.6 TIME 1064 TIME 1094.4 TIME 1124.8 TIME 1155.2 TIME 1185.6 TIME 1216 TIME 1246.4 TIME 1276.8 TIME 1307.2 TIME 1337.6 TIME 1368 TIME 1398.4 TIME 1428.8 TIME 1459.2 TIME 1489.6 TIME 1520 TIME 1550.4 TIME 1580.8 210 TIME 1611.2 TIME 1641.6 TIME 1672 TIME 1702.4 TIME 1732.8 TIME 1763.2 TIME 1793.6 TIME 1824 TIME 1854.4 TIME 1884.8 TIME 1915.2 TIME 1945.6 TIME 1976 TIME 2006.4 TIME 2036.8 TIME 2067.2 TIME 2097.6 TIME 2128 TIME 2158.4 TIME 2188.8 TIME 2219.2 TIME 2249.6 TIME 2280 TIME 2310.4 TIME 2340.8 TIME 2371.2 TIME 2401.6 TIME 2432 TIME 2462.4 211 TIME 2492.8 TIME 2523.2 TIME 2553.6 TIME 2584 TIME 2614.4 TIME 2644.8 TIME 2675.2 TIME 2705.6 TIME 2736 TIME 2766.4 TIME 2796.8 TIME 2827.2 TIME 2857.6 TIME 2888 TIME 2918.4 TIME 2948.8 TIME 2979.2 STOP ***************************** TERMINATE SIMULATION ***************************** RESULTS SECTION WELLDATA RESULTS SECTION PERFS 212 APPENDIX D ANALYTICAL MODEL FOR NON-DARCY EFFECT IN LOW PRODUCTIVITY GAS RESERVOIRS Analytical Model of Pressure Drawdown with N-D Flow Effect For constant-rate production from a well in a gas reservoir with closed outer boundaries, the late-time (stabilized) solution to the diffusivity equation is (Lee & Wattenbarger, 1996): ∆p p = p p ( p ) − p p ( p wf ) ………………………………………………………(D-1) ∆p p = 10.06 A 3 1.422 *10 6 qT − + s + Dq ……………………………(D-2) 1.151 log 2 kg h C A rw 4 Houpeurt (1959) wrote equation 2 in a simple form: ∆p p = p p ( p ) − p p ( p wf ) = aq + bq 2 ………………….………………………….(D-3) Where, a= 10.06 A 3 1.422 *10 6 T − + s ………….…………………………(D-4) 1.151 log 2 kgh C A rw 4 And, b= 1.422 *10 6 TD ..………………………………………………………..…(D-5) kgh Equation D-3 is the basis for Houpeurt’s procedure to analyze well deliverability tests in gas wells. The coefficient a represents the pressure drop generated by viscous forces, and b represents the inertial resistance. The N-D flow coefficient, D, is defined in terms of the inertia coefficient, β, D= 2.715 *10 −12 βk g Mp sc hµ g ( p wf )rw Tsc ……………………………………………………….(D-6) 213 This expression is based on an integration of Forchheimer’s equation assuming steady state flow (Dake, 1978). Lee and Wattenbarger (1996) recommend using the following correlation for β calculations (Jones, 1987): β = 1.88 *10 10 k −1.47 φ −0.53 ……………………………………………………….(D-7) One analytical model was built, using the equations shown above, to evaluate the effect of rock properties, porosity and permeability, and the gas flow rate on the N-D flow. For this model, following Dake (1978) and Golan (1991), h was replaced by hper in Eq. 5. A new variable, F, was defined (White, 2002). F is the fraction of the total pressure drop generated by the N-D flow when gas flows through porous media. Mathematically, F was defined using Eq. 3 as: F= bq ……………………………………………………………………(D-8) a + bq 214 APPENDIX E EXAMPLE IMEX DATA DECK FOR NON-DARCY FLOW IN LOW PRODUCTIVITY GAS RESERVOIRS RESULTS SIMULATOR IMEX RESULTS SECTION INOUT **SS-UNKNOWN ** REGDIMS ** 2 / **SS-ENDUNKNOWN **SS-UNKNOWN ** INIT ** --RPTGRID ** --1 / ** ------------------------------------------------------------**SS-ENDUNKNOWN *DIM *MAX_WELLS 1 *DIM *MAX_LAYERS 100 *********************************************************************** ***** ** ** *IO ** *********************************************************************** ***** *TITLE1 'Non-Darcy Flow Effect in Low-Productivity Gas Reservoir' **Non-Darcy Effect Distribute in the Reservoir **Water Drive Gas Reservoir **-----------------------------------------------------------**SS-NOEFFECT ** MESSAGES ** 6* 3*5000 / **SS-ENDNOEFFECT **-----------------------------------------------------------*INUNIT *FIELD *OUTUNIT *FIELD GRID RADIAL 26 1 110 RW 3.33000000E-1 KDIR DOWN DI IVAR 0.417 0.3016 0.4229 0.5929 0.8313 1.166 1.634 2.292 3.213 4.505 6.317 8.857 12.42 17.41 24.41 34.23 48. 67.3 94.36 132.3 185.5 260.1 364.7 511.4 717. 2500. DJ CON 360. DK KVAR 100*1. 9*10. 710. 215 DTOP 26*5000. RESULTS SECTION GRID RESULTS SECTION NETPAY RESULTS SECTION NETGROSS RESULTS SECTION POR **$ RESULTS PROP POR Units: Dimensionless **$ RESULTS PROP Minimum Value: 0 Maximum Value: 1 POR ALL 2860*1. MOD 1:26 1:1 1:110 = 0.1 26:26 1:1 1:100 = 0 RESULTS SECTION PERMS **$ RESULTS PROP PERMI Units: md **$ RESULTS PROP Minimum Value: 10 PERMI ALL 2860*1. MOD 1:26 1:1 1:110 = 10 **$ RESULTS PROP PERMJ Units: md **$ RESULTS PROP Minimum Value: 10 PERMJ ALL 2860*1. MOD 1:26 1:1 1:110 = 10 **$ RESULTS PROP PERMK Units: md **$ RESULTS PROP Minimum Value: 5 PERMK ALL 2860*1. MOD 1:26 1:1 1:110 = 5 RESULTS SECTION TRANS RESULTS SECTION FRACS RESULTS SECTION GRIDNONARRAYS CPOR MATRIX 1.E-05 PRPOR MATRIX 2500. Maximum Value: 10 Maximum Value: 10 Maximum Value: 5 RESULTS SECTION VOLMOD RESULTS SECTION SECTORLEASE **$ SECTORARRAY 'SECTOR1' Definition. SECTORARRAY 'SECTOR1' ALL 2600*1 260*0 **$ SECTORARRAY 'SECTOR2' SECTORARRAY 'SECTOR2' ALL 2600*0 260*1 Definition. RESULTS SECTION ROCKCOMPACTION RESULTS SECTION GRIDOTHER RESULTS SECTION MODEL MODEL *BLACKOIL 216 **$ OilGas Table 'Table A' *TRES 120. *PVT *EG 1 ** P Rs Bo EG VisO VisG 14.7 10.87 1.0289 5.05973 0.3034 0.011983 213.72 93.23 1.06 75.1695 0.2644 0.01216 412.74 193.36 1.1007 148.3052 0.2378 0.0124 611.76 303.58 1.1482 224.457 0.2184 0.01268 810.78 421.2 1.2014 303.5186 0.2034 0.012993 1009.8 544.75 1.2597 385.257 0.1911 0.013335 1208.82 673.28 1.3225 469.289 0.1809 0.013705 1407.84 806.15 1.3896 555.068 0.1722 0.014103 1606.86 942.87 1.4604 641.895 0.1647 0.014528 1805.88 1083.05 1.535 728.959 0.158 0.01498 2004.9 1226.39 1.6129 815.4 0.1521 0.01546 2203.92 1372.64 1.6942 900.389 0.1469 0.015969 2402.94 1521.59 1.7785 983.192 0.1421 0.016508 2601.96 1673.07 1.8658 1063.222 0.1377 0.017077 2800.98 1826.92 1.956 1140.054 0.1338 0.017678 3000. 1983. 2.0489 1213.424 0.1301 0.018313 *DENSITY *OIL 45. *DENSITY *GAS 0.046 *DENSITY *WATER 62.6263 *CO 3.E-05 *BWI 1.003357 *CW 2.934065E-06 *REFPW 2500. *VWI 0.62582 *CVW 0 RESULTS SECTION MODELARRAYS RESULTS SECTION ROCKFLUID *********************************************************************** ***** ** ** *ROCKFLUID ** *********************************************************************** ***** *ROCKFLUID *RPT 1 *SWT 0.300000 0.400000 0.500000 0.600000 0.700000 0.800000 0.900000 1.000000 0.000000 0.035000 0.076000 0.126000 0.193000 0.288000 0.422000 1.000000 1.000000 0.000000 0.857142857142857 0.000000 0.714285714285714 0.000000 0.571428571428572 0.000000 0.428571428571429 0.000000 0.285714285714286 0.000000 0.142857142857143 0.000000 0.000000 0.000000 *SGT *NOSWC 0.000000 0.000000 0.200000 0.000000 0.300000 0.020000 1.000000 0.000000 0.714285714285714 0.000000 0.571428571428572 0.000000 217 0.400000 0.500000 0.600000 0.700000 0.081000 0.183000 0.325000 0.900000 0.428571428571429 0.000000 0.285714285714286 0.000000 0.142857142857143 0.000000 0.000000 0.000000 *NONDARCY *FG1 *KROIL *SEGREGATED RESULTS SECTION ROCKARRAYS RESULTS SECTION INIT *********************************************************************** ***** ** ** *INITIAL ** *********************************************************************** ***** *INITIAL **-----------------------------------------------------------**SS-NOEFFECT ** RPTSOL ** 6* 2 2 / ** ------------------------------------------------------------**SS-ENDNOEFFECT **-----------------------------------------------------------*VERTICAL *DEPTH_AVE *WATER_GAS *TRANZONE *EQUIL **$ Data for PVT Region 1 **$ ------------------------------------*REFDEPTH 5000. *REFPRES 2300. *DWGC 5100. RESULTS SECTION INITARRAYS **$ RESULTS PROP PB Units: psi **$ RESULTS PROP Minimum Value: 0 PB CON 0 RESULTS SECTION NUMERICAL *NUMERICAL Maximum Value: 0 RESULTS SECTION NUMARRAYS RESULTS SECTION GBKEYWORDS RUN **SS-UNKNOWN ** RPTRST ** 4 / **SS-ENDUNKNOWN RESTARTS ONCE A YEAR DATE 2002 01 01. **------------------------------------------------------------ 218 **SS-NOEFFECT ** NOECHO **SS-ENDNOEFFECT **-----------------------------------------------------------PTUBE WATER_GAS 1 DEPTH 5000. QG 5.E+05 1.E+06 3.E+06 5.E+06 1.E+07 1.5E+07 1.8E+07 WGR 0 5.E-05 1.E-04 0.0002 0.0004 0.0006 0.0008 0.001 WHP 300. 500. 700. BHPTG 1 1 3.37024000E+02 5.59849000E+02 7.84870000E+02 2 1 1.00767000E+03 1.33083000E+03 1.63681000E+03 3 1 1.02840000E+03 1.35532000E+03 1.66413000E+03 4 1 1.06877000E+03 1.40292000E+03 1.71647000E+03 5 1 1.14745000E+03 1.49259000E+03 1.81241000E+03 6 1 1.22282000E+03 1.57486000E+03 1.89758000E+03 7 1 1.29426000E+03 1.65009000E+03 1.97324000E+03 8 1 1.36153000E+03 1.71853000E+03 2.04060000E+03 1 2 3.45916000E+02 5.65127000E+02 7.88564000E+02 2 2 6.85715000E+02 1.14235000E+03 1.43549000E+03 3 2 7.98357000E+02 1.17999000E+03 1.46993000E+03 4 2 9.06174000E+02 1.23965000E+03 1.53687000E+03 5 2 1.03248000E+03 1.35495000E+03 1.66240000E+03 6 2 1.13624000E+03 1.46356000E+03 1.77592000E+03 7 2 1.23434000E+03 1.56415000E+03 1.87771000E+03 8 2 1.32752000E+03 1.65684000E+03 1.96914000E+03 1 3 4.25316000E+02 6.15848000E+02 8.24883000E+02 2 3 5.26979000E+02 7.95789000E+02 1.08259000E+03 3 3 6.46858000E+02 9.33680000E+02 1.24089000E+03 4 3 8.40372000E+02 1.14544000E+03 1.43807000E+03 5 3 1.14282000E+03 1.42442000E+03 1.68147000E+03 6 3 1.39809000E+03 1.65458000E+03 1.89757000E+03 7 3 1.62877000E+03 1.86048000E+03 2.09286000E+03 8 3 1.83827000E+03 2.04934000E+03 2.27214000E+03 1 4 5.47796000E+02 7.04360000E+02 8.91575000E+02 2 4 6.66316000E+02 8.23118000E+02 1.05816000E+03 3 4 7.92196000E+02 9.70272000E+02 1.22716000E+03 4 4 1.03062000E+03 1.22814000E+03 1.50399000E+03 5 4 1.50309000E+03 1.68890000E+03 1.92590000E+03 6 4 1.90174000E+03 2.07013000E+03 2.26855000E+03 7 8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 2 3 4 4 4 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 6 6 6 6 2.24629000E+03 2.56051000E+03 9.16800000E+02 1.17821000E+03 1.40325000E+03 1.79136000E+03 2.63140000E+03 3.33657000E+03 3.93384000E+03 4.54574000E+03 1.30649000E+03 1.69683000E+03 2.01561000E+03 2.60038000E+03 2.39607000E+03 2.69480000E+03 1.01422000E+03 1.26153000E+03 1.48036000E+03 1.87547000E+03 2.70978000E+03 3.40719000E+03 4.00224000E+03 4.60380000E+03 1.37324000E+03 1.75038000E+03 2.06380000E+03 2.65034000E+03 219 2.57229000E+03 2.85658000E+03 1.14823000E+03 1.38041000E+03 1.59380000E+03 2.00566000E+03 2.82769000E+03 3.51185000E+03 4.09229000E+03 4.68526000E+03 1.47144000E+03 1.83132000E+03 2.13846000E+03 2.72983000E+03 5 6 7 8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 6 6 6 6 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 GROUP 'G' ATTACHTO 3.81908000E+03 4.76408000E+03 5.78065000E+03 6.91460000E+03 1.53942000E+03 2.00157000E+03 2.37484000E+03 3.08950000E+03 4.60402000E+03 5.69293000E+03 7.03960000E+03 8.57618000E+03 3.86469000E+03 4.80311000E+03 5.81806000E+03 6.95034000E+03 1.59511000E+03 2.04461000E+03 2.41335000E+03 3.12890000E+03 4.64024000E+03 5.72329000E+03 7.06884000E+03 8.60434000E+03 'FIELD' WELL 1 'P' ATTACHTO 'G' PRODUCER 'P' PWELLBORE TABLE 5000. 1 OPERATE MAX STW 3000. CONT OPERATE MIN WHP IMPLICIT 300. CONT OPERATE MIN BHP 14.7 CONT MONITOR MAX WGR 1. STOP MONITOR MIN STG 0 STOP GEOMETRY K 0.333 0.37 1. 0. PERF GEO 'P' 1 1 1 1. OPEN 1 1 2 1. OPEN 1 1 3 1. OPEN 1 1 4 1. OPEN 1 1 5 1. OPEN 1 1 6 1. OPEN 1 1 7 1. OPEN 1 1 8 1. OPEN 1 1 9 1. OPEN 1 1 10 1. OPEN 1 1 11 1. OPEN 1 1 12 1. OPEN 1 1 13 1. OPEN 1 1 14 1. OPEN 1 1 15 1. OPEN 1 1 16 1. OPEN 1 1 17 1. OPEN 1 1 18 1. OPEN 1 1 19 1. OPEN 1 1 20 1. OPEN 1 1 21 1. OPEN 1 1 22 1. OPEN 1 1 23 1. OPEN 1 1 24 1. OPEN 1 1 25 1. OPEN XFLOW-MODEL 'P' FULLY-MIXED OPEN 'P' TIME 30.4 220 3.93860000E+03 4.86696000E+03 5.87715000E+03 7.00651000E+03 1.67903000E+03 2.11135000E+03 2.47443000E+03 3.19348000E+03 4.70113000E+03 5.77622000E+03 7.11864000E+03 8.65223000E+03 TIME 60.8 TIME 91.2 TIME 121.6 TIME 152 TIME 182.4 TIME 212.8 TIME 243.2 TIME 273.6 TIME 304 TIME 334.4 TIME 364.8 TIME 395.2 TIME 425.6 TIME 456 TIME 486.4 TIME 516.8 TIME 547.2 TIME 577.6 TIME 608 TIME 638.4 TIME 668.8 TIME 699.2 TIME 729.6 TIME 760 TIME 790.4 TIME 820.8 TIME 851.2 TIME 881.6 TIME 912 221 TIME 942.4 TIME 972.8 TIME 1003.2 TIME 1033.6 TIME 1064 TIME 1094.4 TIME 1124.8 TIME 1155.2 TIME 1185.6 TIME 1216 TIME 1246.4 TIME 1276.8 TIME 1307.2 TIME 1337.6 TIME 1368 TIME 1398.4 TIME 1428.8 TIME 1459.2 TIME 1489.6 TIME 1520 TIME 1550.4 TIME 1580.8 TIME 1611.2 TIME 1641.6 TIME 1672 TIME 1702.4 TIME 1732.8 TIME 1763.2 TIME 1793.6 222 TIME 1824 TIME 1854.4 TIME 1884.8 TIME 1915.2 TIME 1945.6 TIME 1976 TIME 2006.4 TIME 2036.8 TIME 2067.2 TIME 2097.6 TIME 2128 TIME 2158.4 TIME 2188.8 TIME 2219.2 TIME 2249.6 TIME 2280 TIME 2310.4 TIME 2340.8 TIME 2371.2 TIME 2401.6 TIME 2432 TIME 2462.4 TIME 2492.8 TIME 2523.2 TIME 2553.6 TIME 2584 TIME 2614.4 TIME 2644.8 TIME 2675.2 223 TIME 2705.6 TIME 2736 TIME 2766.4 TIME 2796.8 TIME 2827.2 TIME 2857.6 TIME 2888 TIME 2918.4 TIME 2948.8 TIME 2979.2 TIME 3009.6 TIME 3040 TIME 3070.4 TIME 3100.8 TIME 3131.2 TIME 3161.6 TIME 3192 TIME 3222.4 TIME 3252.8 TIME 3283.2 TIME 3313.6 TIME 3344 TIME 3374.4 TIME 3404.8 TIME 3435.2 TIME 3465.6 TIME 3496 TIME 3526.4 TIME 3556.8 224 TIME 3587.2 TIME 3617.6 TIME 3648 TIME 3678.4 TIME 3708.8 TIME 3739.2 TIME 3769.6 TIME 3800 TIME 3830.4 TIME 3860.8 TIME 3891.2 TIME 3921.6 TIME 3952 TIME 3982.4 TIME 4012.8 TIME 4043.2 TIME 4073.6 TIME 4104 TIME 4134.4 TIME 4164.8 TIME 4195.2 TIME 4225.6 TIME 4256 TIME 4286.4 TIME 4316.8 TIME 4347.2 TIME 4377.6 TIME 4408 TIME 4438.4 225 TIME 4468.8 TIME 4499.2 TIME 4529.6 TIME 4560 TIME 4590.4 TIME 4620.8 TIME 4651.2 TIME 4681.6 TIME 4712 TIME 4742.4 TIME 4772.8 TIME 4803.2 STOP ***************************** TERMINATE SIMULATION ***************************** RESULTS SECTION WELLDATA RESULTS SECTION PERFS 226 APPENDIX F EXAMPLE ECLIPSE DATA DECK FOR COMPARISON OF CONVENTIONAL WELLS AND DWS WELLS Runspec Title Effect of Completion Length on Conventional Wells --Normal Reservoir Pressure (2300 psia), Horizontal Permeability 10 md, --Length of Perforations: 20 ft. MESSAGES 6* 3*5000 / Radial Dimens -NR Theta NZ 26 1 110 / Gas Water Field Regdims 2 / Welldims -- Wells Con 1 100 / VFPPDIMS 10 10 10 10 0 1 / Start 1 'Jan' 2002 / Nstack 100 / Unifout ------------------------------------------------------------Grid Tops 26*5000 / Inrad 0.333 / DRV 0.4170 0.3016 0.4229 0.5929 0.8313 1.166 1.634 2.292 3.213 4.505 6.317 8.857 12.42 17.41 24.41 34.23 48.00 67.30 94.36 132.3 185.5 260.1 364.7 511.4 717.0 2500 / DZ 2600*1 234*10 26*1410 / Equals 'DTHETA' 360 / 'PERMR' 10 / 'PERMTHT' 10 / 'PERMZ' 5 / 'PORO' 0.25 / 'PORO' 0 26 26 1 1 1 100 / 'PORO' 10 26 26 1 1 101 110 / / 227 INIT --RPTGRID --1 / ------------------------------------------------------------PROPS DENSITY 45 64 0.046 / ROCK 2500 10E-6 / PVTW 2500 1 2.6E-6 0.68 0 / PVZG -- Temperature 120 / -- Press Z Visc 100 0.989 0.0122 300 0.967 0.0124 500 0.947 0.0126 700 0.927 0.0129 900 0.908 0.0133 1100 0.891 0.0137 1300 0.876 0.0141 1500 0.863 0.0146 1700 0.853 0.0151 1900 0.845 0.0157 2100 0.840 0.0163 2300 0.837 0.0167 2500 0.837 0.0177 2700 0.839 0.0184 3200 0.844 0.0202 / --Saturation Functions --Sgc = 0.20 --Krg @ Swir = 0.9 --Swir = 0.3 --Sorg = 0.0 SGFN --Using Honarpour Equation 71 -Sg Krg Pc 0.00 0.000 0.0 0.20 0.000 0.0 0.30 0.020 0.0 0.40 0.081 0.0 0.50 0.183 0.0 0.60 0.325 0.0 0.70 0.900 0.0 / SWFN --Using Honarpour Equation 67 -Sw Krw Pc 0.3 0.000 0.0 0.4 0.035 0.0 0.5 0.076 0.0 0.6 0.126 0.0 0.7 0.193 0.0 0.8 0.288 0.0 0.9 0.422 0.0 1.0 1.000 0.0 228 / ------------------------------------------------------------REGIONS Fipnum 2600*1 260*2 / ------------------------------------------------------------SOLUTION EQUIL 5000 2300 5100 0 5100 0 / RPTSOL 6* 2 2 / ------------------------------------------------------------SUMMARY SEPARATE RPTONLY WGPR / WWPR / WBHP / WTHP / WGPT / WWPT / WBP / RGIP / RPR 1 2 / TCPU ------------------------------------------------------------SCHEDULE NOECHO INCLUDE 'WELL-5000-VI.VFP' / ECHO RPTSCHED 6* 2 / RPTRST 4 / restarts once a year TUNING 0.0007 30.4 0.0007 0.0007 1.2 / 3* 0.00001 3* 0.0001 / 2* 500 1* 50 / WELSPECS 'P' 'G' 1 1 5000 'GAS' 2* 'STOP' 'YES' / / COMPDAT 'P' 1 1 1 20 'OPEN' 2* 0.666 / / WCONPROD 'P' 'OPEN' 'THP' 1* 3000 40000 3* 300 1 / 229 / WECON 'P' 4* / TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 End 1.0 'WELL' 'YES' / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / 230 EXAMPLE ECLIPSE DATA DECK FOR COMPARISON OF DWS AND DGWS DWS MODEL Runspec Title Comparison of DWS and DGWS --DWS-2 Model: Top completion 70 ft; Bottom Completion 60 ft MESSAGES 6* 3*5000 / Radial Dimens -NR Theta NZ 26 1 110 / Gas Water Field Regdims 2 / Welldims -- Wells Con Group Well in group 2 100 1 2 / VFPPDIMS 10 10 10 10 0 2 / Start 1 'Jan' 2002 / Nstack 300 / Unifout ------------------------------------------------------------Grid Tops 26*5000 / Inrad 0.333 / DRV 0.4170 0.3016 0.4229 0.5929 0.8313 1.166 1.634 2.292 3.213 4.505 6.317 8.857 12.42 17.41 24.41 34.23 48.00 67.30 94.36 132.3 185.5 260.1 364.7 511.4 717.0 2500 / DZ 2600*1 234*10 26*1410 / Equals 'DTHETA' 360 / 'PERMR' 1 / 'PERMTHT' 1 / 'PERMZ' .5 / 'PORO' 0.25 / 'PORO' 0 26 26 1 1 1 100 / 'PORO' 10 26 26 1 1 101 110 / / INIT 231 --RPTGRID --1 / ------------------------------------------------------------PROPS DENSITY 45 64 0.046 / ROCK 2500 10E-6 / PVTW 2500 1 2.6E-6 0.68 0 / PVZG -- Temperature 120 / -- Press Z Visc 100 0.989 0.0122 300 0.967 0.0124 500 0.947 0.0126 700 0.927 0.0129 900 0.908 0.0133 1100 0.891 0.0137 1300 0.876 0.0141 1500 0.863 0.0146 1700 0.853 0.0151 1900 0.845 0.0157 2100 0.840 0.0163 2300 0.837 0.0167 2500 0.837 0.0177 2700 0.839 0.0184 3200 0.844 0.0202 / SGFN --Using Honarpour Equation 71 -Sg Krg Pc 0.00 0.000 0.0 0.20 0.000 0.0 0.30 0.020 0.0 0.40 0.081 0.0 0.50 0.183 0.0 0.60 0.325 0.0 0.70 0.900 0.0 / SWFN --Using Honarpour Equation 67 -Sw Krw Pc 0.3 0.000 0.0 0.4 0.035 0.0 0.5 0.076 0.0 0.6 0.126 0.0 0.7 0.193 0.0 0.8 0.288 0.0 0.9 0.422 0.0 1.0 1.000 0.0 / ------------------------------------------------------------REGIONS Fipnum 2600*1 232 260*2 / ------------------------------------------------------------SOLUTION EQUIL 5000 1500 5100 0 5100 0 / RPTSOL 6* 2 2 / ------------------------------------------------------------SUMMARY SEPARATE RPTONLY WGPR / WWPR / WBHP / WTHP / WGPT / WWPT / WBP / RGIP / RPR 1 2 / TCPU ------------------------------------------------------------SCHEDULE NOECHO INCLUDE 'WELL-5000-DGWS.VFP' / ECHO RPTSCHED 6* 2 / RPTRST 4 / restarts once a year TUNING 0.0007 30.4 0.0007 0.0007 1.2 / 3* 0.00001 3* 0.0001 / 2* 500 1* 100 / WELSPECS 'P' 'G' 1 1 5000 'GAS' 2* 'STOP' 'YES' / 'W' 'G' 1 1 5100 'WATER' 2* 'STOP' 'YES' / / COMPDAT 'P' 1 1 1 70 'OPEN' 2* 0.666 / 'W' 1 1 71 103 'OPEN' 2* 0.666 / / WCONPROD 'P' 'OPEN' 'THP' 6* 300 1 / 'W' 'OPEN' 'THP' 6* 300 2 / / WECON 233 'P' 1* 400 3* 'WELL' 'YES' / / TSTEP 35*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / / WCONPROD 'W' 'OPEN' 'THP' 6* 14.7 2 / / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / TSTEP 48*30.4 / 234 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / 235 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 End / / / / / / 236 EXAMPLE ECLIPSE DATA DECK FOR COMPARISON OF DWS AND DGWS DGWS MODEL Runspec Title Comparison of DWS and DGWS --DGWS-1 Model: Top completion 100 ft MESSAGES 6* 3*5000 / Radial Dimens -NR Theta NZ 26 1 110 / Gas Water Field Regdims 2 / Welldims -- Wells Con Group Well in group 2 100 1 2 / VFPPDIMS 10 10 10 10 0 2 / Start 1 'Jan' 2002 / Nstack 800 / Unifout ------------------------------------------------------------Grid Tops 26*5000 / Inrad 0.333 / DRV 0.4170 0.3016 0.4229 0.5929 0.8313 1.166 1.634 2.292 3.213 4.505 6.317 8.857 12.42 17.41 24.41 34.23 48.00 67.30 94.36 132.3 185.5 260.1 364.7 511.4 717.0 2500 / DZ 2600*1 234*10 26*1410 / Equals 'DTHETA' 360 / 'PERMR' 1 / 'PERMTHT' 1 / 'PERMZ' .5 / 'PORO' 0.25 / 'PORO' 0 26 26 1 1 1 100 / 'PORO' 10 26 26 1 1 101 110 / / INIT --RPTGRID --1 / 237 ------------------------------------------------------------PROPS DENSITY 45 64 0.046 / ROCK 2500 10E-6 / PVTW 2500 1 2.6E-6 0.68 0 / PVZG -- Temperature 120 / -- Press Z Visc 100 0.989 0.0122 300 0.967 0.0124 500 0.947 0.0126 700 0.927 0.0129 900 0.908 0.0133 1100 0.891 0.0137 1300 0.876 0.0141 1500 0.863 0.0146 1700 0.853 0.0151 1900 0.845 0.0157 2100 0.840 0.0163 2300 0.837 0.0167 2500 0.837 0.0177 2700 0.839 0.0184 3200 0.844 0.0202 / SGFN --Using Honarpour Equation 71 -Sg Krg Pc 0.00 0.000 0.0 0.20 0.000 0.0 0.30 0.020 0.0 0.40 0.081 0.0 0.50 0.183 0.0 0.60 0.325 0.0 0.70 0.900 0.0 / SWFN --Using Honarpour Equation 67 -Sw Krw Pc 0.3 0.000 0.0 0.4 0.035 0.0 0.5 0.076 0.0 0.6 0.126 0.0 0.7 0.193 0.0 0.8 0.288 0.0 0.9 0.422 0.0 1.0 1.000 0.0 / ------------------------------------------------------------REGIONS Fipnum 2600*1 260*2 / ------------------------------------------------------------- 238 SOLUTION EQUIL 5000 1500 5100 0 5100 0 / RPTSOL 6* 2 2 / ------------------------------------------------------------SUMMARY SEPARATE RPTONLY WGPR / WWPR / WBHP / WTHP / WGPT / WWPT / WBP / RGIP / RPR 1 2 / TCPU ------------------------------------------------------------SCHEDULE NOECHO INCLUDE 'WELL-5000-DGWS.VFP' / ECHO RPTSCHED 6* 2 / RPTRST 4 / restarts once a year TUNING 0.0007 30.4 0.0007 0.0007 1.2 / 3* 0.00001 3* 0.0001 / 2* 1000 1* 500 / WELSPECS 'P' 'G' 1 1 5000 'GAS' 2* 'STOP' 'YES' / 'W' 'G' 1 1 5000 'WATER' 2* 'STOP' 'YES' / / COMPDAT 'P' 1 1 1 100 'OPEN' 2* 0.666 / 'W' 1 1 1 100 'SHUT' 2* 0.666 / / WCONPROD 'P' 'OPEN' 'THP' 1* 3000 40000 2* 50 300 1 / 'W' 'SHUT' 'THP' 6* 300 2 / / WECON 'P' 1* 400 3* 'WELL' 'YES' / / TSTEP 239 48*30.4 / TSTEP 31*30.4 / / COMPDAT 'W' 1 1 1 100 / WCONPROD 'W' 'OPEN' 'THP' 'P' 'SHUT' 'THP' / TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 'OPEN' 2* 6* 6* 2 / 1 / 300 300 0.666 / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / 240 / TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / 241 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 TSTEP 48*30.4 End / / / / / / 242 ECLIPSE VFP INCLUDED FILE: WELL-5000-DGWS VFPPROD 1 5.00000E+003 'GAS' 'WGR' 'OGR' 'THP' '' 'FIELD' 'BHP'/ 5.00000E+002 1.00000E+004 3.00000E+002 0.00000E+000 4.00000E-001 0.00000E+000 0.00000E+000 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 3 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 3 2 1 1 1 3 1 1 2 3 1 1 3 3 1 1 1 4 1 1 2 4 1 1 3 4 1 1 1 5 1 1 2 5 1 1 3 5 1 1 1 6 1 1 2 6 1 1 3 6 1 1 1 7 1 1 2 7 1 1 3 7 1 1 1 8 1 1 1.00000E+003 1.50000E+004 5.00000E+002 5.00000E-002 6.00000E-001 / / 3.37024E+002 9.16800E+002 5.59849E+002 1.01422E+003 7.84870E+002 1.14823E+003 1.00767E+003 1.17821E+003 1.33083E+003 1.26153E+003 1.63681E+003 1.38041E+003 1.02840E+003 1.40325E+003 1.35532E+003 1.48036E+003 1.66413E+003 1.59380E+003 1.06877E+003 1.79136E+003 1.40292E+003 1.87547E+003 1.71647E+003 2.00566E+003 1.14745E+003 2.63140E+003 1.49259E+003 2.70978E+003 1.81241E+003 2.82769E+003 1.22282E+003 3.33657E+003 1.57486E+003 3.40719E+003 1.89758E+003 3.51185E+003 1.29426E+003 3.93384E+003 1.65009E+003 4.00224E+003 1.97324E+003 4.09229E+003 1.36153E+003 4.54574E+003 3.00000E+003 1.80000E+004 7.00000E+002 1.00000E-001 8.00000E-001 3.45916E+002 1.30649E+003 5.65127E+002 1.37324E+003 7.88564E+002 1.47144E+003 6.85715E+002 1.69683E+003 1.14235E+003 1.75038E+003 1.43549E+003 1.83132E+003 7.98358E+002 2.01561E+003 1.17999E+003 2.06380E+003 1.46993E+003 2.13846E+003 9.06174E+002 2.60038E+003 1.23965E+003 2.65034E+003 1.53687E+003 2.72983E+003 1.03248E+003 3.81908E+003 1.35495E+003 3.86469E+003 1.66240E+003 3.93860E+003 1.13624E+003 4.76408E+003 1.46356E+003 4.80311E+003 1.77592E+003 4.86696E+003 1.23434E+003 5.78065E+003 1.56415E+003 5.81806E+003 1.87771E+003 5.87715E+003 1.32752E+003 6.91460E+003 243 5.00000E+003 / / 2.00000E-001 1.00000E+000 4.25316E+002 1.53942E+003 6.15848E+002 1.59511E+003 8.24884E+002 1.67903E+003 5.26979E+002 2.00157E+003 7.95789E+002 2.04461E+003 1.08259E+003 2.11135E+003 6.46858E+002 2.37484E+003 9.33680E+002 2.41335E+003 1.24089E+003 2.47443E+003 8.40372E+002 3.08950E+003 1.14544E+003 3.12890E+003 1.43807E+003 3.19348E+003 1.14282E+003 4.60402E+003 1.42442E+003 4.64024E+003 1.68147E+003 4.70113E+003 1.39809E+003 5.69293E+003 1.65458E+003 5.72329E+003 1.89757E+003 5.77621E+003 1.62877E+003 7.03960E+003 1.86048E+003 7.06883E+003 2.09286E+003 7.11864E+003 1.83827E+003 8.57619E+003 / 5.47796E+002 / 7.04360E+002 / 8.91574E+002 / 6.66317E+002 / 8.23119E+002 / 1.05816E+003 / 7.92196E+002 / 9.70272E+002 / 1.22716E+003 / 1.03062E+003 / 1.22814E+003 / 1.50399E+003 / 1.50309E+003 / 1.68890E+003 / 1.92590E+003 / 1.90174E+003 / 2.07013E+003 / 2.26855E+003 / 2.24629E+003 / 2.39607E+003 / 2.57229E+003 / 2.56051E+003 / 2 8 1 1 3 8 1 1 1.71853E+003 4.60380E+003 2.04060E+003 4.68526E+003 1.65684E+003 6.95034E+003 1.96914E+003 7.00651E+003 2.04934E+003 8.60433E+003 2.27214E+003 8.65222E+003 2.69480E+003 / 2.85658E+003 / VFPPROD 2 5.00000E+003 'GAS' 'WGR' 'OGR' 'THP' '' 'FIELD' 'BHP'/ 5.00000E+002 1.00000E+004 1.00000E+002 0.00000E+000 0.00000E+000 0.00000E+000 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 3 1 1 1 4 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 3 2 1 1 4 2 1 1 1.00000E+003 1.50000E+004 3.00000E+002 1.20000E+000 / / 1.20764E+002 8.67338E+002 3.37024E+002 9.16800E+002 5.59849E+002 1.01422E+003 7.84870E+002 1.14823E+003 1.20764E+002 8.67338E+002 3.37024E+002 9.16800E+002 5.59849E+002 1.01422E+003 7.84870E+002 1.14823E+003 3.00000E+003 / 5.00000E+002 / 1.44218E+002 1.27581E+003 3.45916E+002 1.30649E+003 5.65127E+002 1.37324E+003 7.88564E+002 1.47144E+003 1.44218E+002 1.27581E+003 3.45916E+002 1.30649E+003 5.65127E+002 1.37324E+003 7.88564E+002 1.47144E+003 244 5.00000E+003 7.00000E+002 2.88734E+002 / 4.25316E+002 / 6.15848E+002 / 8.24884E+002 / 2.88734E+002 / 4.25316E+002 / 6.15848E+002 / 8.24884E+002 / / 4.52423E+002 5.47796E+002 7.04360E+002 8.91574E+002 4.52423E+002 5.47796E+002 7.04360E+002 8.91574E+002 VITA Miguel A. Armenta Sanchez, son of Miguel A. Armenta Van-Strahalen and Salvadora Sanchez de Armenta, was born on April 3, 1964, in Santa Marta, Magdalena, Colombia. He received the degree of Bachelor Engineering in Petroleum Engineering from the Universidad Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga, Colombia, in June 1986. In June 1996, he received his master’s degree in environmental development from the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia. He has over fourteen years of industry experience in petroleum engineering practice working for ECOPETROL (The State Oil Company of Colombia) on drilling projects. His job experience ranges from designing, supervising on site, and evaluating drilling operations to solving environmental problems of drilling projects in sensitive areas like the Amazon rain forest. He enrolled in the doctoral degree program in petroleum engineering at the Craft and Hawkins Department of Petroleum Engineering in August 2000. The doctoral degree is conferred on him at the December 2003 commencement. 245