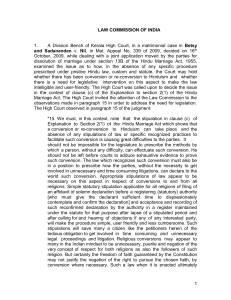

Rhetoric against Age of Consent: Resisting Colonial Reason and Death of a Child-Wife Author(s): Tanika Sarkar Source: Economic and Political Weekly , Sep. 4, 1993, Vol. 28, No. 36 (Sep. 4, 1993), pp. 1869-1878 Published by: Economic and Political Weekly Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4400113 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Economic and Political Weekly is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Economic and Political Weekly This content downloaded from 14.139.45.242 on Fri, 16 Aug 2024 08:40:01 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms SPECIAL ARTICLES Rhetoric againstAge of Consent Resisting Colonial Reason and Death of a Child-Wife Taiiika Sarkar The historian cannot afford to view the colonial past as an unproblematic retrospect wvhere allpower w side and allprotest on the other. Partisanship has to take into account a mullti-faceted nationalism, allaspe w4ere complicit withpowerand domination even when they critiqued western knowledgeand challenged co This article contends that colonial structures ofpower comprontised with-indeed learnt much fiom-ind patriarchy and upper caste norms and practices which, in certain areas of life, retained considerable Legislative activity on Hindu marriage issues in the lastfew decades of the centu ry forms the discursivef exercise. I forced a decisive break in their discourse.this It single source. Each and every kind of made it imperative for them to shift to an contestation, by the same token, is taken to AT the risk of provoking startled disbelief, be equally valid. Today, with a triumphalist entirely different terrain of arguments and I propose to place constructions of IHindu images, moving from the realm of reason growth of aggressively communal and/or conjugality at the very heart of the forma- and pleasure to that of discipline and pain. fundamentalistic indentity-politics in our tive moment for militant nationalism in The entire exercise, I hope, will widen the country, such a position comes close to Bengal.' Ilistorians have adequately noted context of early nationalist agitations and indigenism and acquires a near Fascistic the centrality of debates around colonial give them an unfamiliar genealogy. potential in its authoritarian insistence on laws on women and marriage in the disA few words are necessary to explain the purity of indigenous epistemological course of liberal reformers. No attempt, why, in the present juncture of cultural and autological conditions. however, has been made so far to locate studies on colonial India, it is important to It has weird implications for the feminist these themes within early IIindu nationalretrieve this specific history of revivalist- agenda as well. The assumption that coloism. nationalism, and to work with a concept of nialism had wiped out all past histories of Three interlocking themes will be taken nationalism that incorporates this history. patriarchal domination, replacing them up and elaborated simultaneously. In the Edward Said's Orientalism has fathered a neatly and exclusively with western forms last few decades of the 19th century, a fairly received wisdom on colonial studies that of gender relations, has naturally led on to. distinct political formation had emerged has proved to be as narrow and frozen in its an identification of patriarchy in modern that I shall clumsily designate as revivalistscope as it has been powerful in its impact. India with the project of liberal reform nationalist. It wasa mixed groupof newspaIt proceeds fromaconviction in the totalising alone. While liberalism is made to stand in per proprietors, orthodox urban estate holdnature of a western power knowledge that for the only vehicle of patriarchal ideology ers of considerable civic importance within gives to the entire Orient a single image since it is complicit with western knowlCalcutta and pundits as well as modern with absolute efficacy. Writings of the Sub-edge, its opponents-the revivalists, the intellectuals whom they patronised. They altern Studies pundits and of a group of orthodoxy-are vested with a rebellious, used an explicitlynationalistrhetoricagainst feminists, largely located in thc first worldeven emancipatory agenda, since they reany form of colonial intervention within the academia, have come to identify the strucfused colonisation of the domestic ideolHindu domestic sphere which marked them tures of colonial knowledge as the origi nary ogy. And since colonised knowledge is reoff from the broader category of revivalist moment for all possible kinds of power and garded as the exclusive source of all power, thinkers who would not necessarily oppose disciplinary formations, since, going by anything that contests it is supposed to have reformism in the name of resisting colonialSaid, Orientalism alone reserves for itself an emancipatory possibility for the women. knowledge. At the same time, their comthe whole range of hegemonistic capabiliBy easy degrees, then, we reach the position mitment to an unreformed Ilindu way of ties. This unproblematic and entirely non- that while opposition to widow immolation lifeseparated them from liberal nationalists historicised 'transfer of power' to strucwas complicit with colonial silencing of of the Indian Association or Indian National tures of colonial knowledge has three major non-colonised voicesand, consequently, was Congress variety. Needless to say, these consequences; it constructs a necessarily an exercise of power, the practice of widow groups were not irrevocably distinct or monolithic, non-stratified colonised subimmolation itself was a contestatory act mutually exclusive. Despite considerable ject who is, moreover, entirely powerless outside the realm of power reladtons since it shifts and overlaps, however, we do idenand entirely without an effective and opera- was not sanctioned by colonisation. In a tify a distinctive political formation of na- tive history of his/her own. The only historycountry, where people will still gather in tionalists who contributed to emerging nathat s/he is capable of generating is neces- lakhs to watch and celebrate the buming of tionalisma highly militant agitational rheto- sarily a derivative one. As a result, the a teen-aged girl assati, such cultural studies ric and mobilising techniques built around colonised subject is absolved of all comare heavy with grim political implications. the defence of l-indu patriarchy. plicity and culpability in the makings of the We will try tocontend that colonial struc. The second related theme would explore structures of exploitation in the last two tures of power compromised with, indeed as to why they chose to tie their nationalism hundred years of our history. The only learnt much from indigenous patriarchy to issues of conjugality which they defined culpability lies in the surrender to colonial and upper caste norms and practices which, as a system of non-consensual, i ndi ssol ubl e, knowledge. As a result, the lone political in certain areas of life, retained considerinfant marriage. And, finally, we need to agenda for a historiography of this period able hegemony. Tlhis opens up a new condwell upon the arguments they fabricated. shrinks to the contcstation ofcolohial knowl-text against which we may revaluate liberal We find that the Age of Consent issue edgc since all power supposedly flows fromreform. Above all, we need to remember Economic and Political Weekly September 4, 1993 1869 This content downloaded from 14.139.45.242 on Fri, 16 Aug 2024 08:40:01 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms the wife reaches her puberty. Since puberty oppressive and marginalised clerical existthat other sources of hegemony, far from ence, the household of the bhadralok inwas quite likely to occur before she was 12 becoming extinct, were reactivated under in the hot climate of Bengal, the new legis- creasingly appeared as the solitary sphere of colonialism and opposed the liberal rationalist agenda with considerable vigour and lation meant that the ritual would no longerautonomy, a site of formal knowledge where-and only here-education would success. The historian cannot afford to view remain compulsory. If the wife reaches yield practical, manipulateable, controllable the colonial past as an unproblematic retro- puberty before attaining the age of consent, results. The Permanent Settlement had genspect where all power was on one side and then garbhadhan could not be performed. erated a class- of parasitic landlords with all protest on the other. Partisanship has toThis, in turn, implied that the 'pinda' or take into account a multi-faceted national- ancestral offerings, served upby the sonsof fixed revenue obligation whose passivity was reinforced by uninhibited control over ism (and not simply its liberal variant), all such marriages, would become impure and that generations of ancestors would be their peasants' rent. The gap between a aspectsof which were complicitwith power fixed sum of revenue and a flexible rent starved of it. The argument provided the and domination even when they critiqued central ground for a highly organised mass procurement in a period of rising agriculwestern knowledge and challenged colotural prices, cushioned an existenceof fairly campaign in Bengal. The first open massnial power. comfortable tenure holding. The Rent Acts level anti-government protest in Calcutta of 1859 and 1885, however, breaches that and the official prosecution of a leading lI security. Organised tenant resistance of the newspaper were its direct consequences.6 late 19th century led to heightened anxiThe summary might be taken to suggest, A summary of the most controversial eties and uncertainties among the landed Cambridge School fashion,7that nationalist legislative activity on Hindu marriage isinitiative was actually a mere reflex action, gentry. The household, consequently, besues in the last few decades of the century came doubly precious and important as the following mechanically upon the legal iniwould help to map out our discursive field. tiatives of the colonial state. Far from being only zone where autonomy and self-rule The Native Marriage Act III of 1872 was, so, however, not only was colonial initiacould be preserved.'0 0 for its times, an extremely radical package tive itself generally a belated and forced In the massive corpus of household manwhich prohibited polygamy, legalised divorce and laid down a fairly high minimum surrender to Indian reformist pressure but agement manuals that came to occupy a Hindu revivalist reaction against both was dominant place in the total volume of printed age of marriage. It also ruled out caste or vernacular prose literature of these years, religious barriers to marriage. Predictably, ultimately constituted by a new political compulsion. It was coterminus with a rethe proposed bill raised a storm of controthe household was likened to an enterprise versy. Its jurisdiction was eventually nar- cently-acquired notion of the colonised self to be administered, an army to be led, a state that grew out of the'1857 uprising, postto be governed"-all metaphors, rather rowed down to people who would declare themselves to be not Hindus, not ChrisMutiny reprisals, Lyttonian discriminatory poignantly, derived from activities from which colonised Bengalis were excluded. tians, and not Jains, Buddhists or Sikhs. In policies in the 1870s and the Ilbert Bill short, its scope came to cover the Brahmos racist agitations in the 1880s. These experiUnlike Victorian middle class situations, alone, whose initiative had led to its incepences collectively and cumulatively modithen, the family was not a refuge after work tion in the first place.2 fied and cast into agonising doubt the ear- for the man. It was their real place of work. Furiousdebatesaroundthebill hadopened lier choice of loyalism that the Bengali Whether in the Kalighat bazaar paintings'2 up and problematised crucial areas of H indu intelligentsia had made fairly unambiguor in the Bengali fiction of the 19th century, workplace situations remain shadowy, conjugality-in particular the system of ously in 1857. Our understanding of renon-consensual, indissoluble infant marsponses to colonial legislation can make unsubstantial mostly absent. Domestic reriage whose ties were considered to remain only very limited and distorted sense unless lations constitute the axis around which binding for women even after the death of they are located within this larger context. plots are generated, in sharp contrast with their busbands. The polemic hardened in Whereas early 19th century male liberal for example, Dickensian novels.'3 1887 when Rukma Bai, an educated girl reformers had been deepl y sel f-critical about The new nationalist world-view, then, from the lowly carpenter caste, refused to the bondage of the women withi n the housereimaged the family as a contrast to and a live with her uneducated, consumptive hushold,8 the satirised literary self-representa-critique of alien rule. This was done primaband, claiming that since the marriage was tion of the Bengali 'baboo' of the later rily by contrasting two different versions of contracted in her infancy it could be repudi- decades recounted a very different order of subjection-that of the colonised Hindu ated by her decision as an adult. She was lapses for himself: his was a self that had male in the world outside and of the apparthreatened with imprisonment under Act lost its autonomy and that now willingly ently subordinated Hindu wife at home. T'he XV of 1877 for non-restitution of conjugal hugged its chains. Rethinking about the forced surrender and real dispossession of rights. The threat was removed only after burden of complicity with colonialism ham-the former was counterposed to the allegconsiderable reformist agitation and the mered out a reoriented self-critique as well edly loving, willed surrender and ultimate personal intervention of Victoria.3 The isas a heightened perception about the mean-self-fulfilment of the latter.'4 It was in the sue foregrounded very forcefully the prob-ingofsubjection. It is, perhaps, noaccident, interests of this intended contrast that conlems of consent and indissolubility within that even the economic critiques of drain, jugality was constituted as the centre of Ilindu marriage.4 In 1891 the Parsi redeindustrialisation and poverty would come gravity around which the discursive field on former Malabari's campaign bore fruit in to be developed by the post-1860s generathe family organised itself. All other relaTheCriminal LawAmendment Act l0which tions. tions, even the mother-child one (which revised Section 375 of the Penal Code of With the gradual dissolution of faith in thewould come to take up its place as the 1860, and raised the minimum age of conprogressive potential of colonialism that pivotal point in the later nationalist diss-ent for married and unmarried girls from accompanied political self-doubt and the course) remained subordinated to it up to 10 to 12.5 Under the earlier Penal Code failureof indigenouseconomic enterprises,9the end of the 19th century. It was the regulation a husband could legally cohabit there alsodeveloped a disenchantment about relationship between the husband and wife wvith a wife who was 10 years old. The the magical possibilities of western educathat mediated and rephrased within revivalrevivalist Hindu intelligentsia of Bengal, tion that had led the earlier reformers to lookist-nationalism, the political themeofdominow claimed that the new act violated a hopefully at the public shpere asan arena for nation-subordination, of subjection-refundamental ritual observance in the lifethe test of manhood, of genuine self-imsistance as the lyrical or existential problem cycle of the Ilindu houscholder-that is, provement. With the boundaries of activi- of love, of equal but different ways of the 'garbhadhan' ceremony, or the obligaties shrinking into the constrictive limits of loving. tory cohabitation between husband and wi fe parasitic petty landlordism or tenure-holdThe household generally, and conjugalwhich should take place immediately afterings andl to mechanical chores within anity specifically, came to mean the last inde- 1870 Economic and Political Weekly September 4, 1993 This content downloaded from 14.139.45.242 on Fri, 16 Aug 2024 08:40:01 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms pendent space left to the colonised HIindu. This was a conviction that was both shaped and reinforced by some of the premises of colonial law. English legislators and j udges clearly postulated a basic division within the legal domain. British and Anglo-Indian law had a 'territorial' scope and ruled over the 'public' world of land relations, criminal law, laws of contract and of evidence. into courts of law after due ritual purifica- often in conflict with cach other.2> In any tion of the space.2" Tlhe introduction of i case, the prolonged primacy of case law and limited jury system between the 1860s and- common law procedures within England the 1880s in Bengal further strengthened itself made English judges in India agree the voice of local Ilindu notables, and, with Indian legal and nationalist opinion consequently, of local usages and norms. that customs, usages and precedents were An official recommendation of 1890 curfar more valid sources of law than legislatailed the powers of the jury in many othertion.29 directions but left the powers of settling A general consensus about the differentiated nature of colonial law, then, postulated a fissure within the system wherein Hindus form a unified, internally coherent body ofcould insert their claims for a sectoral, but sonal', covering persons rather than areas, and ruling over the more intimate areas of opinion on proper Hindu norms and prac- complete autonomy, for a pure space. The tices which they would then try to freeze. specific A and concrete embodiment of this human existence-family relationships, substantial debate developed over a propurity seemed to lie more within the body of family property and religious life.'5 Early posal in 1873 to transfer the cognisance of the Hindu women, rather than of the mannationalists chose to read this as a gap between the territory or the land colonised cases connected with marriage offences, a conviction shaped, no doubt, by the growby an alien law, and the person, still ruled by especialy adultery, from criminal to civil ing self-doubt of the post-1857 Hindu male. one's own faith-a distinction that the courts. While Simson, the Dacca CommisIncreasingly, irony and satire, a kind of Queen's Proclamation of 1859, promising sioler, recommended the repeal of penal black humour, became the dominant form absolute non-interference in religious mat- provisions against adultery, Reynolds, the of educated middle class literary self-repreters, did much to bolster.'6 Even in sub- Magistrate of Mymensingh strongly desentation. There was an obsessive insisjected India, therefore, there could exist anmurred: "I have always observed with great tence or the physical manifestation of this interior space that was as yet inviolate. aversion the practice of the English law in weakness. The feeble Bengali male phyFar from trying tohegemonise this sphere giving damages in cases of adultery and sique became a metaphor for a larger condiseduction, and wanted it to remain a crimiand absolutising its control, colonial rule, tion. Simultaneously, it was a site of the especially in the post-1857 decades, tried to nal offence."' About cases of forfeiture of critique of the ravaging effects of colonial keep its distance from it, thus indirectly property rights by 'unchaste widows', there rule. "The term Bengali is a synonym for a adding to the nationalist conviction. The was a clear division between the high courts creature afflicted with inflammation of the earlier zeal for textualisation and codificaof Allahabad on the one hand and those of liver, enlargement of the spleen, acidity or tion of traditional laws was gradually reBombay, Madrasand Calcutta on the other.24 headache." Or, "Their bones are weak, placed by a recognition of the importance of The divisions reflected the absence of any their muscles are flabby, their nerves toneunwritten and varied custom, of the inadmonolithic or absolute consensus about the less."'" Or, "Bengal is ruined. There is not a visability of legislation on such matters, excellence of English legal practices as a single really healthy man in it. The digesand of urging judicial deference, even obemodel for Indian life. tive powers have been affected and we can dience, to local Hindu opinion.'7 Towards These decades in England had gone eat but a little. Wherever onc goes he sees a the end of the century, a strong body of through profound changesi n women's diseased rights people.32 Through the grind of Ihindulawyersand judgescame tobe formedin property holding, marriage, divorce, the western education, offic9routine33 and enwhose conformity to Ihindu practices rights of prostitutes to physical privacy.25 forced urbanisation, with the loss of tradi(Ilindutva) was often taken to be of decisiveEnglishmen in India were divided about tional sports and martial activities, it was importance in judicial decision-making, their direction and a significant section felt supposedly marked, maimed and completely even though their professional training was disturbed by the limited, though real, gainsremade by colonialism. It was the visible in western jurisprudence, and not in Hindu made by contemporary English feminists. site of surrender and loss, of defeat and law.'7, There was, moreover, an implicit They turned with relief to the so-called alien discipline. grey zone of unwritten law whose force was relative stability and strictness of l-lindu The woman's body, on the other hand, nevertheless quite substantial within law rules. The Hindu joint familysystem, whose was still held to be pure and unmarked, courts.'8 Take a Serampore Court case of collective aspects supposedly fully subloyal and subservient to the discipline of 1873, for instance, where a I-lindu widow merged and subordinated individual rights shastras alone. It was not a free body by any was suing her brothers-in-law for defraud- and interests, was generally described with means, but one ruled by 'our' scriptures, ing her of her share in her husband's pov- warm appreciation-2 They found here a our custom. The difference with the male erty by falsely charging her with system of relatively unquestioned patriarbody bestowed on it a redemptive, healing 'unchastity'. Her lawycr referred frequently chal absolutism which promised a more strength for the community as a whole. An to notions of kinship obligations, ritual comfortable state of affairs after the bitter interesting change now takes place in the expectations from a Hi ndu widow and moral struggleswith Victorian feminism at home. representation of the Hindu women in the norms and practices of high castc women.'9 The colonial experience itself mediated andnew nationalist discourse. Whereas for the Clearly, these arguments were thought toreoriented contemporary debates on conju-liberal reformers she used to be the archehave value in convincing the judge and the gal legislation in England. There were imtypal victim figure, for nationalists she had jury, even though, overtly they had little portant controversies, forinstance, between become a repository of power, the Kali legal significance. Far from laughing pecuJohn Stuart Mill and James Fitzjames rampant, a figure of range and strength.34 liarly Hindu susceptibilities out of court, Stephen on issues of consensus vs force and What were the precise sources of grace English judges, even the Privy Council, authority as the valid basis for social and for the Hindu women? Sheattained itthrough seriously rationalised them. Referring to human relations. Stephen, drawing on his a unique capacity for bearing pain and the existence of a flindu idol as a legal military-bureaucratic apprenticeship in In- discipline that were exercised upon her person in a different law suit, an English dia, questioned Mill's premise of body by the iron laws of absolute chastity judge commented: "Nothing impossible or complementarity and the notion of the extending beyond the death of the husband, absurd in it ...after all an idol is as much of companionate marriage.2' Nor was there through a an indissolube, non-consensual ina person as a corporation."' Legal as well stable legal or judicial model to import. fant form of marriage, through austere widas ritual niceties about the proper disposi- Prior to the Judicature Act of 1873 there owhood, and through a proved past papacity tion of idols were seriously and lengthily were four separate systems of courts in for self-immolation. All of them together debated and sacred objects were brought England, eachl applying its own form of lawimprinted an inexorable disciplinary regi- On the other hand, there were Ihindu andmarriage disputes intact in their hands.22 Nor did colonial legislators and judges Muslim laws which were defined as 'per- Economic and Pol'-:al Weekly September This content downloaded from 14.139.45.242 on Fri, 16 Aug 2024 08:40:01 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 4, 1993 1871 men upon her person that contained and the Hindu order, was a double-edged and organisingsilence lies at the heart of the defined her from infancy to death. Such weapon: once it was raised, sooner or later, projected image of desire and pleasure. discipline was not entirely confined to the the question of mutuality was bound to Even if the quality of Ilindu love was normative or conceptual sphere. Bengal, come. Was it equally binding on botb part- assumed to be a higher one, Hindu marriage with the exception of the Central Provinces ners? If it was not so, since hlindu males was still placed firmly within mainstream and Berar, and Bihar and Orissa,- had the were allowed to be polygamous, could its developments in the universal history of jurisdiction on the women be anything moremarriages which had supposedly trodden a highest rate of infant marriages-a custom that cut across caste and community lines than prescriptive? Particularly, if -marriageuniform path from the 'captive' stage to and did not markedly decrease even after was imposed on her at infancy without a fairly permanent, often sacramental systhe Act of 1891.31 Before it was banned, as question of her consent or choice? tems. Any consent-based alternative, we know, Bengal had also been the heartNothing in the Hindu shastras would con- whether in ancient Indian or in class-based land of the practice of sari. The Ilindu firm the possibility of mutually monoga- modem western traditions, were dismissed women'sdemonstrated capacity for acceptmous ties. To redeem the past absence, for as aberrations or minor variations.45 A long ing pain and harshi discipline thus became the first time in the history of Hindu mar- editorial, significantly entitled The Bogus the last measuate of hope and greatness for a riage, a wave of polemical literature apScience, questioned the sources and authendoomed people. BankimChandra linked up peared that valorised, inideed, insisted on ticity of reformist knowledge: the nature of sati with national regeneration: "I can see male monogamy: "We find tracts that adtheir evidence, of deduction, of arrangethe funeral pyre burning, the chaste wife vise widowers never to remarry."' Some ment, of proof.6 The powerful eugenicssitting at the heart of the blazing flames, manuals that advocate self-immolation for based argument against infant-marriage (inclasping the feet of her husband lovingly to the adult widow, simultaneously advise that fant marriages produce weak progenies) her breasts. Slowly the fire spreads, dechild widows should be remarried. They was countered by a climatic view of hisstroying one part of her body and entering could have no obligation towards a husband tory:47 irrespective of the age of parents, a another. tier face is joyful ...The flames whom they had not, as yet, come to love.4" tropical climate was bound to produce weak burn higher, life departs and the body is Not just sacred texts but custom, too alchildren. Reformers were accused of casuburint to ashes. ...When I think that only lowed a very wide spectrum of castes to istry or weak logic. Since the Penal Code some time back our women could die like make a second marriage for men possible if had earlier laid down 10 as the minimum this, then new hope rises up in me, then I the first wife was barren or bore no sons.42age of consent, how would raising it to 12 have faith that we, too, have the seeds of In the absence of a shastricor custom-based ensure genuine consent? "A girl of fourteen greatness within us. Women of Bengal You injuniction against polygamy and given theor sixteen is not capable of legally signing are the truejewels of this country ."3 Bankim reluctance among Hiindu revivalist-nationa note of hand for 5 rupees and she is ipso had plenty of reservations for other aspects alists to invite ref'ormist- legislation, male facto a great deal more incompetent to give of llindu conjugality,37 but he seemed to chasti ty was fated to remain normative ratherherconsent todefile her person at twelve."'8 identify with it at its most violent point of than obligatory, while the woman's chas- It was also considered to be more than a termination, through a highly sensualised tity was not a function of choice or willedlittle dishonest to place such importance on spectacle of pain and death, a barely disconsent. Tlhis was a compromise that be-the woman's consent in this one matter guised parallel between the actual flames came fundamentally difficult to sustain. since within post marital offences, "in the destroying a feminine body and the conThrough much of the 1880s we find acase of the wife the point does not turn on suming fires of desire. studied silence on such uncomfortable po-consent, for, if that had been the case, there tential within Hindu marriage and a self- would have no such offence as adultery in III mesmerising repetition of its innately.af-the Penal Code."49 A high premium was fective qualities. The infant-marriage ritualthus placed on the rule of rationality in the There were two equally strong compulis drenched in a warm, suffusing glow of defence of Hindu marriage. sions and possibilities of construction of loveability. "People in this country take a Hindu rationality was represented as a Ilindu womenhood-love and pain-which greatpleasure in infant-marriage. The littlemore supportive world view than reformist produced a deep anxiety within early nabit of a women, the infant bride, clad in redor colonial projects. Given the physical and tionalism. silk, her back turned towards her boy hus-economic weakness of women, an indisThe accent on love, had, from the begin- band... Drums are beating, and men, womensoluble marriage tie had to be her only ning, underlined acute discomfort about and children are running in order to have security-a a contention that once again conmutuality and equality. Pandit Sasadhar glimpse of that face... from time to time she veniently overlooked the fact, that, in a Tarkachuramani, the doyen of Hindu ortho- breaks forth into little ravishing smiles. Shepolygamousworld, indissolubilitywasbinddoxy, argued that a higher form of love looks like a littlelovely doll"' (italics mine).ing, in effect, on the women alone. A cleardistinguished between western and Hindu T'he key words here are little, lovely, ravish-eyed kulin brahmin widow haj remarked: marriages. While the former seeks social ing, pleasure, infant, doll." They are care-"People say that the seven ties that bind the stability and order through control over fully inserted at regular intervals to makeflindu wife to the husband do not snap as sexual morality, the latter apparently asthe general account of festivities draw itsthey do with Christians or Muslims. This is pires only towards "the unification of two warmth from this single major source-the not true. According to Ilindu law, the wife souls. "Mere temporal happiness, the bedelightful and delighted infant bride. Thecannot leave the husband but the husband getting of children are very minor and sub- community of "men, women and children"may leave her whenever he wants to."'' It ordinate considerations in Hiindu mar- formed round the occasion is bonded to- was also maintained that consent was imriage."" The revivalist-nationalist segment gether by a deeply sensuous experience, bymaterial since parents were better equipped of the vernacular press, polemical tracts great visual pleasurc, by happiness; happi- to handle the vital question of security than and manuals translated the notion of mar- ness is the operative word. We need to notean immature girl.5" Security also largely riage of souls as mutual love, ensured and that the radiant picture of innocent celebra-depended upon perfect integration with the proved by a lifetime of togetherness since tion is rounded off through the cleverlyhusband's family, so the sooner the process infancy such a uniquely Ilindu way of lov- casual insertion of one phrase: 'boy husbegan, the better it was for the girl.52 ing anchors the woman's absol ute chastity, band'. Infant marriage, however, was prelIindu marriage, in the rather defensive extending beyond the husband's death, in scriptive for the girl alone and the groom at discourse of the 1880s, tlhen, was more mutual desire alone." Yet the very empha-the side of the 'lovely doll' could be, and pleasurable and more beautiful, kinder and sis on love, so necessary as a critique of frequently was, a mature, even elderly man, safer, more rational and guaranteed by a alien oppression and misunderstanding ofpossibly muchz-marriedl already. A strategic sounder system of knowledge. In any case, 1872 Economic and Political Weekby September 4, 1993 This content downloaded from 14.139.45.242 on Fri, 16 Aug 2024 08:40:01 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms it was essentially a part of universal devIlopments in the history of civilisationrs. Differences in marriage system between the Hindu and the non-Hindu, therefore, were, so far played down, if not obliterated. unambiguous. "The Brahmin caste occupies the highest position and all laws and ordinances have been formed with special In 1890, Phulmonee, a girl of about 10 or 11, was raped to death by her husband, Hari Mati, a man of 35. Under existing reference to that. All the other castes con- Penal Code provisions, however, he was not guilty of rape since Phulmonee had duct themselves after the fashion of the been well within the statutory age limit of Brahminical castes."58 Or, "it is true that 10. The event, however, added enormous divorce obtains among some low caste The Rukma Bai episode of 1887 made it weight and urgency to Malabari's camimperative at last to rewrite the narrative of people and the government should be really paign for raising the age or consent from love and pleasure in the language of force. doing an important duty as a ruler if it 10 to 12. The reformist press began to should make laws fixing and negotiating The earlier lyricism had already been rupsystematically collect and publish acthe uncertain and unsettled marriage custured from time to time to underline and counts of similar incidents from all over toms of the people."'9 recuperate the basic logic of nonthe country. Forty-four women doctors consensuality. At a meeting convened at The the debate prised open the imagined brought out long lists of cases where childcommunity along the lines of caste and palace of the Shova Bazar Raj, Rajendralal Mitra had insisted: "in it [Hindu marriage] gender and delineated the specific contours wives had been maimed or killed because of the revivalist-nationalist agenda. It could of rape.62 From the possible effects of there is no selection, no self-choice, no child marriage on the health of future consent on the part of the bride. She is an no longer base its hegemonistic claims on its supposed leadership to the struggles of a generations the debate shifted to the life article of gift, she is given away even as a and safety of Hindu wives. cow or any other chattel." Laughter greeted whole subjected people for autonomy and Phulmonee was the daughter of late his exposition approvingly and he went on: self-rule in their 'private' lives. Its nationKunj Behari Maitee, a man from the 'Oriya "There is in Hinduism not the remotest idea alism became more precisely defined as the Kyast' caste, who had been a 'Bazar Sircar' ruie of brahmanical patriarchy. Its rationalof choice and whoever changed any small at Bow Bazar Market. It was a well paid ity was one of forced and absolute dominapart of it was no Hindu."53 Rukma Bai's tion of upper-caste, male standards, not one job and it seems that by claiming 'Oriya action violently foregrounded the sexual Kyast' status, the family was trying for a of universal reason leading towards freedouble standards and made a mockery of superior caste posi tion in consonance with dom and self-determination for the disposthe notion of the loving heart of hlindu their economic viability since Maitees are sessed. If it aspired to detach Hindus from conjugality. A lot of the debate centred otherwise categorised as a low sudra group. a colonised reason and lead them to selfaround the vexed question-whether a rule, it would only do so by substituting forThe ramily frequently referred to its spewomen could sue for separation from an it a brahmanical, patriarchal reason based cific caste practices in court with somne adulterous husband. 'Among the Hindus, pride. They said that while they adhered to on scripture-cum-custom, both of which unchastity on the part of the husband is were as disciplinary and deprivational for child marriage, they forbade cohabitation certainly a culpable offence but they set the ruled subjects as was the colonial rebefore the girl menstruates, and that in this much higher value upon female chastity": gime in the sphere of Indian political case, Phulmonee had not done so. Their its erosion would lead to the loss of family version was that the newly-married couple economy. Contestation of colonisation was honour, growth of half-castes and the deno simple, escape from or refusal of power: had been kept apart according to caste struction of ancestral rites.' Bare, stark nor had colonialism equally and entirely rules, and that Hari, on a visit to his inbones that formed the basic foundation of laws, had stolen into Phulmonee's room Hindu marriage nowbegan tosurface, threat- disempowered all Indians. Resistance was and had forced himself upon her, thereby ening to blow the edifice of love away. "A an agenda itself irrevocably tied to schemes causing her death. Hlari Maiti, however, for domination, an exercise of power that good Hindu wife should always serve her was nearly as absolute as that which it insisted that since the marriage she had husband as God even if that husband is illiterate, devoid of good qualities and atresisted. spent at least a fortnight at his house and tached to other women. And it is the duty of they had slept together all the time. He the govemment to make Hindu women IV made no mention of caste rules against conform to the injunctions of the Shastras."55 pre-menstrual cohabitation. It seems then The basis of conjugality now openly shifts Very curiously, one possibility within that caste customs remained loose and to prescription. Ilindu marriage had not occurred to reform-flexible, and that each family would allow istsor to Bengali ilindu militants-the pos- considerable manipulation within them. Rukma Bai had forced a choice upon her community-between the women's right to sibility of sexual abuse of infant wives. Even though Ilari Maiti had insisted that free will and the future of the pristine eson the last night they had not had interThere had been, from time to time, the sence of Hindu marriage. The two could no course, medical opinion was unanimous occasional stray report. TheDaccaPrakash longer be welded togetheras a perfect whole. of June 1875 reported that an 'elderly' manthat the girl had died of violent sexual Revivalist-nationalists had to treat the two had beaten his child wife to death when shepenetration. If the court accepted that Hlari as separate, conflicting units and indicate refused to go to bed with him. Neighbours was right and that Phulmonee had slept with their partisanship. had tried to cover it up as suicide but the him earlier, then it could go a long way to That came forth in no time at all. "It is murdercharge waseventually proved against show that since nothing untoward had hapvery strange that the whole of Hi ndu society him. The jury, however, let him off with a pened earlier, on the fatal night in question, will suffer for the sake of a very ordinary light sentence.60 The E(ucation Gazette of Ilari would not have any reasbn to suspect women."56 Or, "kindness to the female sex May 1873 had reported a similar incident that a more vigorous penetration might lead cannot be a good plea in favour of the when the 'mature' husband of a girl of 11 to violent consequences. lIe would, in fact, proposed alteration."57 Interestingly, the "dragged her out by the hair and beat hcr till have been convinced that intercourse was episode had shown up another fault in the he killed her" forsimilarreasons. Hewaslet perfectly safe. The English judge, Wilson, imageofthefHinducommunity. Rukma Bai off with a light sentence as well.6' Reportclearly indicated that he chose to accept belonged to the carpenter caste where diing remained sporadic and the accounts llari's version, thus exonerating him from vorce had been customary. Whose custom were not picked up and woven into any the charge of culpable homicide. The charge must colonial law recognise now? Was general discussion about Hlindu marriage as in any case, was not permissible of rape Hinduism a heterogeneous, indeed, selfyet. The controversy about the right age of since the Penal Code provisions ruled out divided, self-contradictory formation, or consent continued to hinge on eugenics, the existence of rape by the husband if the was it a unified monolithic one? The reviv- mortality, child rearing and family interwi fe was above the age of 10. Thejudge was alist-nationalist answer, once again, was ests. equally opposed to any extension of the Economic and Politic"' Weekly September 4, 1993 1873 This content downloaded from 14.139.45.242 on Fri, 16 Aug 2024 08:40:01 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms strict letters of the law in this case to devise should be ceremonially married. That, in the lute form of patriarchal domination evoKe a exemplary punishment for a palticularly constitution of Hlindu society, isa matter with measure of unconsciotus respect and fellow horrible death: "Neither judges nor Juries whlich no Government could meddle and no feeling among the usually conservative, have any right to do for themselves what the Government ought to meddle. male English authorities, rather than the law has not done." instinct for reform? As the Secretary to the They proceeded to review the considerable The judge, then, built up his case on the Public I-Health Society put it: "The history of medico-legal data on sexual injuries inhypothetical argument that the couple had British rule and the workings of British flicted on child wives and concluded that slept togetherearlier. lie chose to ignore the courts in India manifest a distinct tenderwhatever the weight of evidence on the version given by the women in the girl's ness towards...the customs and religious matter, the system of infant marriage must family-of Radhamonee, Bhondamonee and observances of the Indian people."' continue unabated. The age of commencing cohabitation could be raised otly if Hiindus There was still the mangled body of "that unhappy child, Phulmonee I)assee," a girl themselves expressed a great desire for I think it is my duty to say that I think there change (emphasis mine). of ten or eleven, sexually used by a man exists hardly such solid and satisfactory Contrary to received wisdom, then, there whom she had known only for a few weeks, ground as would make it safe to say that this is hardly a vision of remaking the Hindu as who was twenty-nine years her senior, and man must have had knowledge that he was a pale image of his master, of designs of who had already been married once (aunt likely tocause thedeath of the girl ... You will,total change and reform. Macaulay's notoBhondamonee's evidence in court). There of course, in these, as in all matters, give the rious plan of recasting the native as a brown was the deposition of her mother benefit of any doubt in favour of the prisoner.sahib was not necessarily a design that Radhamonee: "I saw my daughter lying remained uniformly dominant for the entirethe cot, weltering in blood... I-ler cloth an The weight of concern is, very blatantly, on Sonamonee, the mother, aunt and grandmother of the girl. the exoneration of the man rather than on the fate of the women. The law itself was spectrum of colonial rule. Even when domi- the bedcloth and lari 's cloth were wet with exonerate the system of marriage that had made this death possible. agitation over demands of constitutional nant, it had to make crucial negotiations blood."6' There was unanimous medical opinion that Hlari had caused the death of a shaped so as to preserve custom as well as with other imperatives and value prefergirl whose body was still immature and the male right to the enjoyment of an infan- ences and, above all, with the everlasting could not sustain penetration. She died after tile female body. What needs to be particu- calculation of political expediency. If, at 13 hoursof acute pain andcontinuousblecdthe time of Macaulay, the Anglicist vision larly noted here is that throughout the trial, of a westernised middle class had appeared ing. The dry medical terminology somehow the judge was saying -nothing about a husband who insisted on sleeping with a child, as the strongest reservoir of loyalism, soon accentuates the horror more than words of enough other al ternatives emerged and were censure: or about the custom which allowed him to do so with impunity. Above all, he was not partially accommodated, modifying the ear- A clot, measuring 3 i nches by one-and-a-half inches in the vagina... a longitudinal tear one lier formula and crucially mitigating its making any judgmental comparison bereformist thrust. Our moment of the 1890s and three quarters long by one inch broad at tween the ways of husbands, eastern or the upper end of the vagina... a haematoma western. In fact, he bent over backwards tocomes after a long spell of middle class three inches in diameter in the cellular tissue rights, of Indianisation of the services, of of the pelvis. Vagina, uterus and ovaries small and undeveloped. No sign of ovulasecurity against racial discrimination and Under no system of law with which Courts tion." abuse. It comes after the outburst of white have had to do in this country, whether Hindu Phulmonee's was by no means an isoracism over the Ilbert Bill issue when the or Mohammedan, or that formed under Britlated case. Dr Chever's investigations of educated middle class was temporarily ish rule, has it ever been the law that a vested with the possibility of standing in a1856 had mentioned at least 14 cases of husband has the absolute right to enjoy the premenstrual cohabitation that had come to position of judicial authority over Europerson of his wife without regard to the his notice, and the subsequent findings inpean. Empowering the Indian through question of safety to her.63 corporated in Dr McLeod's report on child westernisation, consequently, came to be Both the Hindu husband and the Hindu envisaged as the most threatening menace marriage amply corroborated his data .0 We marriage system are generously exempted to the colonial racial structures. It was a may presume that only such cases as would from blame and criticism. There is, in fact, have needed police intervention or urgent moment when the slightest concession to an assertion about the continuity in the medical attention would be entered into the Indian liberal reformism would be made spirit of the law from the time of the Ilindu most unwillingly and only on the belief that records. These were, then, cases of serious kingdoms to the time of British rule. damages that resulted from premature sexual it represented a majority opinion. A significant body of English medical activity. An Indian doctor reported in court The new legislation was conceived after opinion confirmed the clean bill of health the reformist agitation had convinced the that 13 per cent of the maternity cases that that the colonial judiciary had advanced to he had handled involved mothers below the authorities that the 'great majority' was thellindu marriagesystem. Eveninastrictly ready for change.65 Right after the age of thirteen. The defence lawyer threw a private communication, meant for the colo- Phulmonee episode, the revivalist-nationchallenge at the court: cohabiting with a nial officialdom alone, the secretary to the alists were maintaining a somewhat embarpre-pubertal wife might not have Shastric Public hlealth Society wrote to the govern- rassed silence which was broken only after sanction, yet so deep-rooted was the custom ment of Bengal: that he wondered how many men present in the proposed bill came along. During the interval, it was the reformist voice alone court were not in some way complicit with The council direct me to lay special stress the practice? 70 that could be audible. Since this, for the upon the point...that they base no charge The divisional commissioners of Dacca, moment, looked like the majority demand, against the native community. political expediency coincided temporarily Noakhali, Chittagong and Burdwan deposed They reverently cited the work on Ilindu with reformist impulse and the government that child marriage was widely prevalent law by Sir Thomas Strange to evoke, in committed itself to raising the age of con- among all castes, barring the tribals, in their near-mystical terms, the supreme impordivisions. The commissioner of Rajshahi sent. At the same time, official opinion in tance of his marriage rules to the llindu,,pnd division found that only in Jalpaiguri disBengal did not extend the terms of the the inadvisability of external interference specific reform to any larger plans for trict "Mechhes and other aboriginal tribes with them: invasive changes. On the contrary, if dis- do not favour child marriage... amongst the The council admit that our native fellow played a keenness to learn from the codes of Muhammadans and Rajbungshis, females subejects must be aallowed the fullest possible h-indu patriarchy. D)id a recognition thatbeing useful in field work, are not generally freedom in deciding when their children they were confronted with the most abso- marriedl until they are more advanced in 1874 Economic and Political Weekly This content downloaded from 14.139.45.242 on Fri, 16 Aug 2024 08:40:01 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms September 4, 1993 age". On the whole, it was more common they could not push the age too far back, more of a consciousness raising device, a since they hadnot opposed the earlier Penal among lower castes. The average age of foregrounding.of issues of domestic ideolCode ban on marital cohabitation before the marriage for upper caste girls was slowly ogy than pinning effective hopes of real moving up to 12 or 13 due to the relatively social change to acts. Norwas the minimalist girl was 10. If they now chose to construe large spread of the new liberal education the earlier ban as an oppressive intrusion programme of insisting on the woman's among them, and, ironically, to the growingthat had already interfered with Hindu mar- physical safety an.insignificant matter, under the circumstances. Revivalist-nationalpressurcs of dowry which forced parcnts to riage practices, then they could no longer keep daughters unmarried till they could sustain their present agitational rhctoric: istson theother hand, grounded theiragenda put togetheran adequate amount of dowry.7" that the currrent intervention was the first on the most violently authoritarian regime In fact, the compulsion to delay marriage of patriarchal absolutism. Their insistence fundamental violation of I Iindu conjugality till the dowrycould becollected would have and therefore spelt the beginning of the end on self-rule in the domestic sphere coinfound a convenient ally in the new liberalof the only frec space left to the Ilindu. cided with their insistence that the hIindu ism. Among the lower castes, on the other Without this sense of a new, momentous girl should sacrifice her physical safety, hand, emulation of brahmanical orthodoxy beginning of doom, the pitch of the highly and even her life, if necessary, to defend the rather than of liberal values would be a apocalyptic rhetoric would fall flat. If the community's claim to autonomy. more assured way of claiming a pure ritual As the reformist campaign gathered monew legislation were to be seen as merely a status. Wherever infant marriage prevailed, part of a long-drawn out process, then oppo- mentum and as the government, by the end there was no way of ensuring that cohabita-sition to it could hardly invest itself with a of 1890, seemed committed to Malabari's tion would be delayed till the onset of life or death mission. TIhey, therefore, in- prosals, I-lindu militants were faced with puberty. sisted that 'true puberty' only occurred two options. They could accept a radical While both scriptural and customary inbetween the ages 10 and 12. Even if menreorientation of their earlier emphasis: that junctions were too strongly weighted in struation occurred earlier, it would be a is, they could admit of a basic problem favour of early marriage to allow a raising fluke and not a regular flow. The earlier within present marriage practices and then of the age of marriage for girls, certain partsIPenal Code regulation had not therefore delink them from past, supposedly authenof the shastras did prescribe against preinterfered with the garbhadhan ceremony. tic norms. This way, they could still mainpubertal cohabitation among married Since in the hot climate of Bengal, mentain their distance from reformers by insistcouples. Nobin Chandra Sen, poet and disarche was sure to start between 10 and 12, ing on reform from within in place of alien trict magistrate of Chittagong, suggested the further raising of the age of consent legislation from outside. While this would that this injunction could be reinforced with would constitute the first real breach in have amounted to an honourable face-saving legislation. Official opinion tried to distin- ritual practice. device, it would still have implied an asguish between two distinct levels in marReformers argued that puberty sets in sault on the totality and inviolability of riage; the wedding ceremony itself was properly only after 12. In this, they used a what had so far been exalted as the essential interpreted as a sort of a betrothal, after different notion of puberty itself. While core of the system. Worse still, it would which girls remained in their parent's homes. revivalist-nationalists unequivocally have amounted to a surrender to missionIt was only after the onset of puberty that equated puberty with menarche, medicalary, reformist and rationalist critiques of they went through a 'second marriage' and reformers argued that puberty was a proHindu conjugality. On the other hand, it went off to live with their husbands. A longed process, and menarche was the sign could come to terms with the phenomenon group of 'medical reformers' (Indian as of its commencement, not of its culminaof violence and build its own counter camwell as European doctors who advocated tion. The beginning of menstruation did not paign around its presence. If difference was changes in marriage rules on strictly mediindicate the girl's 'sexual maturity' which found to lie not in superior rationality, cal grounds) as well as administrators admeant that her physical organs were develgreater humanism, pleasure or love, but, vised legislation to ban marital cohabitaoped enough to sustain sexual penetration rather, in pain and coercion, then these tion before the performance of the second without serious pain or damage. Until that constituents of difference should be admitmarriage. They hoped that there was suffi- capability had been attained, they argued, ted and celebrated. cient shastric as well as customary sanctionthe notion of her consent was meaningbehind the practice.72 less. V It was soon clear, however, that too much It is remarkable how all strands of opinwas being made of the 'second marriage'. It ion-colonial, revivalist-nationalist, mediThe Age of Consent Bill could have reawas not generally taken to constitute a cal-reformer-agreed on a definition of sonably been faulted on many counts. It was distinct separate stage within marriage as aconsent that pegged it to a purely physical an unbelievably messy and impractical meawhole. While there was a widespread rec- capability, divorcedentirely from freechoice sure. Reporting and verification of crime ognition that girls should begin regular of partner, from sexual, emotional or mcn-were generally impossible in familial situ-cohabitation only after they attained putal compatibility. Consent was made into a ations. Even if the girl (if she survived) and berty, the custom was customarily violated. biological category, a stage when the feher parents were willing to depose against Once the marriage had been performed, a lot of domestic, especially feminine, pres- male body was ready to accept sexual penetration without serious harm. The only the husband, neighbours, whose evidence was crucial in such cases, usually protected sure pulled the wife into the husband's difference lay in assessing when this stagethe man. Proving the girl's age was fairly family. In any case, itwasdifficult todecide was reached. impossible in a country where births are exactly at what age girls attained puberty It would be simplistic, however, to constill not registered. Medical examination and to make sure that no girl was sent off clude to that there was a complete identity in was often inconclusive. Where matters did her husband before that. Any viable piece of patriarchal values betwecn reformers and eventually reach the court, the jury, and legislation would have tospell out a di finite revivalists. Whatever their broader views, Bri tish judges, fearful of offending custom, age at which puberty starts rather than indi- reformers always had to struggle with a rarely took up a firm stand. In 1891, the cate a gceneral physical condition. minimalist programme since nothing else mother of a young girl had pressed for legal T he definition of puberty proved to be the would havc the remotest chance of acceptaction in such a case and the girl herself stumbling block. According to custom, it ability cither with the legislative authorigave very definite evidence in court. On the was cquated with the onset of regular menties, orwith Ilindu socicty. Wconly have to basis of a dental examination the English struation. And here, revivalist-nationalists remind ourselves about the explosive promagistrate, however, could not be absowere trcading delicate ground. While they tests that this legislation provoked. Rte- I utely certai n that she was not oover 12. The wantedl to oppose the proposed age of 12,formist campaigning for legislation was 11usbandl was consequently discharged.73 Economic and(i Political Weekly September 4, 1993 1875 This content downloaded from 14.139.45.242 on Fri, 16 Aug 2024 08:40:01 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Unnerved by the massive anti-bill agitations, the government itself hastened to undermine the scope of the act. Five days after its enactment, Lord Lansdowne sent circulars instructing that enquiries should be held by "native Magistrates" alone and in any case of doubt, prosecution should be operations. The claim is justified by breaking up and dispersing the sources of Hindu conjugal ity among numerous and ever-shifting points of location. Some could be based on written texts, some located in oral traditions, yet others in ritual practices, and- to commit the primal sin against Hinduisml, that an unprecedented attack was going to be mounted on the last pure space left to a conquered pcople, was necessary to relocate the beginnings of true colonisation here and now-so that a new chronology of resistance could also begin from this moment, redeeming the earlier choice of most problematic of all-a whole lot could be simply embedded in an undefinable, loyalism. amorphous, diffused Il-indu way of life, The nationalist press referred to thesc problems from time to time but used them accessible to Ihindu instincts alone. The The Indians have felt for the last two centuintention is to disperse the sources of Hindu ries that India is no longcr theirm, that it has as auxiliary arguments rather than as central ones. Certain other kinds of political Law and custom beyond condified texts, passed into the hands of the Yavanas. But the criticism found a stronger resonance. There however, authoritative or authentic those Indians have, up to this time, found solace in was a powerfully articulated fear about the might be. Even an ancient authority like the thought that though their country is not extension of police intrusion right into the Manu, who advocated 16 as the upper limit theirs, their religion is theirs.80 heart of the I-lindu household.75 There was of marriage age for girls, was dismissed as Or, even more forcefully and explicitly, alsostrong opposition on the ground that an someone who wrote for the colder northern "No, no, a hundred battles like that of unreformed and unrepresentative legislaregions where puberty came later. Charak Plassey, Assay, Multan could not in terture should not legislate on such controver- and Susruta weredismissed even more sumribleness of effect compare with the step sial matters 76- a criticism that sought to marily as near-Buddhists who had scant Lord ILandsowne has taken."' With the regard for true Ili ndu val ues. The process of link up the anti-Bill agitation with current possibility of protest in the near future, Moderate Congress-type constitutional dewide dispersal renders Hlindu customs apocalyptic descriptions of subjection beopaque and infinitely flexible, to the point mands. These protests too remained rather came common: "Tlhe day has at length marginal to the true core of the Ilindu of being eternally elusive to the colonial arrived when dogs and jackals, hares and revivalist-nationalist debate which wascarauthorities. goats will have it all their way. India is The crucial emphasis lay on the reiteraried on by hardliners like the newspapers going to be converted into a most unholy BaJtgabas hi,DainikOSamacharChafndrika tion that the proposed law was the first of itshell, swarming with hell worms and or the Amritabazar Patrika. kind to breach and violate the fundamentals hell insects. ...The hlindu family is IHindu nationalists started on a very faof Hlinduism. The argument could only be ruined.'' 82 miliar note that had been struck on all sorts clinched by derecognising the importance It was this language of resistance and of issues since the 1870s: a foreign governof earlier colonial interventions in Hindu repudiation that gave the Age of Consent ment was irrevocably alien to the meaning domestic practices. Sati, it was argued, was controversy such wide resonance among of Hindu practices. And, where knowledge never a compulsory ritual obligation and its the Bengali middle class. Tlhe Banigabaslii, does not exist, there power must not be abolition therefore mercly scratched the in particular, formulated a rhetoric in these exercised. A somewhat long illustration surfacc of Hlindu existence. The Widow years with phenomenal success,' becomfrom the Daintik 0 Samachar ChlantdrikaRemarriage Act had a highly restricted ing in the process, the leading Bengali sums up a number of typical statements onscope, simply dcclaring children born of daily, changingover from its weekly status, the matter. a second marriage to be legal heirs to their and pulling a whole lot of erstwhile reformThat a women should, from her childhood,fathers' properties.78 Reformers replied that ist paperswith itsorbit forsome time. Even the new bill was no unprecedented revision Vidyasagar, the ideal-typical reformer figremain near !ler husband, and think of her of custom either, since the Penal Code had husband and should not even think of or see ure, criticised the bill.' postponed.74 already banned cohabitation forgirls before the face of another man...are injunctions of the Hlindu Shastras, the significance whereof the age of 10. Since girls could attain puberty before that age, the sanctity of the The response of a fairly pro-reform journal, the Bengalee, epitomises the way in which the new agitational mood reacted on is understoodonlyby 'sasttvik' [pure] people like the Hindus. The Englislh look to thc garbhadhan ceremony had already been a potentially reform-minded, yet largely nationalist intelligentsia. It had supported purity of the body. But in Hindu opinion she threatened. flindu revivalist-nationalists retaliated with a reference to the elusive alone is chaste and pure who has never even the bill quite staunchly up to the end of sources of I-lindu custom and a notion of the January, 1891, after which there seemed to thought of one who is not her husband. No llindu 'normalising' order which could be one who does not see with a 1Hindu s eye will occur an abrupt change of line. In February, grasped by pure-born Ilindus alone. not be able to understand the secret meaning after reporting on "an enormous mass protest meeting, the largest that had ever been of Hiindu practices and observances.... Ac- It seems they [the reformers] do not know the held", it started to find problems with the cording to the Ihindu the childhood of a girl meaning of Adtya RitlJ [real menses]. Mere is to be determined by reference, to her first flow of blood is no sign of Adya Ritu. A girllegislation-albeit more of a constitutional never menstruates before she is 10 and even kind, with reflections upon the unrepresentamenses and not to her age...77 The first point made here is a methodological one that disputes the attempt to comprehend any foreign system of mean- ing through one's own cognitive categories (and immediately proceeds todoso itself by generalising on English attitudes about the body and the soul). The meaning of Hlindu if she does the event must be considered tive nature of the legislature.' In March it unnatural.79This took care of the 1860 Penal covered yet another mammoth protest meetCode provision againstcohabitingwith a girl ing and then redefined the grounds of its under 10. An 'authentic' [Iindu girl accordown opposition. "It is no longer the laning to revivalists does not reach puberty guage of appeal which opponents of the Bill before slhe is 10. The earlierban had thereforeaddress to the rulers of the land....U-owever not really tampered with H-findu practices.much we may differ from the opponents of Were the ceiling to be extended to 12, a the measure, we cannot but respect such female childhood is then made different serious interference would take place. IFhe sentiments."' through a different arrangement of medical,meaning of physicality itself is constituted We, therefore, turnr to the 'language' of sexual, moral and behavioural conditions. differentlyand uniform biological symptoms the opponents, to the Banzgabashli. I lere was While revivalist-nationalists do not, as yet, do not point to a universal bodily developa radical leap from mendicantappeals, from insist on complete autonomy in the actual mentall scheme, since Ilindus alone know oblique and qualified criticism and from formulation and application of personal what stands for the normal and the abnormal guilt and shame-ridden self-satirisation. in the bodly's growth. laws, they do claim the sole and ultimate Ilere was the birth of a powerful, self- right to determine their general field of 1876 Economic and T he i nsistence: that thc English were about confident nationalist rhetoric. "Who would Political Weekly This content downloaded from 14.139.45.242 on Fri, 16 Aug 2024 08:40:01 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms September 4, 1993 over Hindu marripge controversies. Even in translation the power of the voice comes through. The repetitive short Certain newspapers, especially the sentences joined by 'ands', the frequency Bangabashti, took the lead in mobilising protest, organising mass rallies and proof the word 'must', the use of vaster and voking official prosecution. That paryet vaster numbers to build up inexorably ticular group, however, soon withdrew, The Englishman now stands before us in all towards a sense of infinite doom-all add from the scene of confrontation. In the his grim and naked hideousness. What a grim up to an incantatory, mandatory, apocalyptic mode of speech that is the typical Swadeshi movement of 1905-08, the appearance. How dreadful the attitude... The Bangabashi would remain quiescent, even demons of cremation ground are laughing a vehicle for a fundamentalist millenarianism. All external reasoning has loyal to the authori ties. I owe this piece of wild, weird laugh. Is this the form of our information to Sumit Sarkar. For an exRuling power? Brahmaraksharh, Terror of been chipped away, just the bare mandate is repeated and emphasised through threats cellent study of the newspaper see Amiya the Universe; Englishmen... do you gnash your teeth, frown with your red eyes, laugh and warnings. This is an immensely powSen, 'Hindu Revivalism in Bengal' (unand yell, flinging aside your matted erful, dignified voice, aeons away from published thesis, Delhi University, 1980). locks...and keeping time to the clang of timid the mendicancy or morbid self-doubt. 2 Charles H Heimsath, Indian Nationalism sword and bayonet...do you engage yourandHindu SocialReform, Princeton UniThis is the proud voice of the community, selves in a wild dance ...and we...the twenty legislation on itself in total defiance of versity Press, pp 91-94; Ajit Kumar crores of Indians shall lose our fear and open foreign rule, of alien rationalism. It speaks Chakraborti, Maharshi Dabendranath our forty crores of eyes." the authoritative word in the appropriately Tagore, Allahabad, 1916, Calcutta, 1971, Very confidently, almost gleefully, every authoritarian voice. The Hindu woman's pp 406-35. former trapping of rationalisation was peeled body is the site of a struggle that for the 3 The act of 1877 was a colonial intervenaway from the core message. Admittedly first time declares war on the very fundation to tighten up the marriage bond which sanction for infant marriage came from mentals of an alien power-knowledge systhe Eindu orthodoxy strongly defended Raghunandan alone, who was a late and tem. Yet it is not merely a displaced site on the ground that it coincided with, and local authority. It might well lead to other for other arguments but remains, at this reinforced the true essence of Hindu condeaths.'9 It did, in all likelihood, weaken moment,the heart of the struggle. Bengali jugality. future progeny and lead to racial degenera- Hindu revivalist-nationalism, at this for4 See Dagmar Engels, 'The Limits of Gention; but "the Hindu prizes his religion mative moment, begins its career by deder Ideology: Bengali Women, the Coloabove his life and short-lived children".' fining itself as the realm of unfreedom. nial State and the Private Sphere, 1890Hindu shastras undoubtedly imposed harsh I would not like to end, howeyer, with this 1930, Women Studies', International Fosuffering on women. "This discipline is the speech, however, powerful. Its very contesrum, Vol 12, 1989. pride and glory of chaste women and it tation of alien reformism and rationalism, 5 Heimsath, op cit, pp 147-75. prevails only in Hindu society"'.9' There its defence of community custom, represses 6 See extracts from BangabashiandDainik were yet other practices that might bring onthe pain of its women whose protest was O Samachar Chandrika between 1889 her death. drowned to make way for an alleged conand 1891 in Report on Native Newspapers, Bengal (henceforth RNP, FastingonEkadashi(fortnightlyfasting with- sensus. It is no longer possible to resurrect Bengal). out even a drink of water that widows are the protest of Phulmonee and of many, 7 For this version of Cambridge historiogmeant to ritually maintain) is a cruel custommany other battered child wives who died or nearly died asa result of marital rape. We raphy on Indian nationalism see, and many weak-bodied widows very nearly Gallagher, Seal and Johnson, Locality, die of observing it...it is prescribed only in a have, however, several instanceswhen cases were lodged at the initiative of the girl's Province and Nation, Cambridge, 1973. small 'tatwa' of Raghunandan. Is it to be 8 I have discussed this in Hindu Household banned, too, for this reason, the guardian ofmothers, sometimes forcing the hands of the male guardians-a rare demonstration and Conjugality in Nineteenth Century the widow arraigned in front of the High of the woman's protest action for those Bengal, paper read at the Women's StudCourt and pronounced guilty by the Baboo times. We also have a court deposition left ies' Centre, Jadavpur University, Calcutta, jurors? 92 have thought that a dead body would rise up again? Whoever thought that millionsof corpses would again become instinct with life?" 8 There was an exhilarating sense of release in the naming of the enemy. There would be other Phulmonees who would die similar violent deaths through infant marriage. Yet, by a young girl who was severely wounded and violated by her elderly husband. 1989. 9 N K Sinha, Economic History of Bengal, Calcutta, n d. "I cannot say how old I am. I have not reached 10 N K Sinha (ed), The Iistory of Bengal. puberty. I was sleeping when my husband "the performance of the garbhadhan cer- seized my hand....I cried out. He stopped my 11 See for instance Prasad Das Goswami, emony is obligatory upon all. Garbhadhan Amader Sanmaj, Serampore 1896; mouth. I was insensible owing to his outrage must be after first menstruation. It means the on me. My htusband violated me against my Ishanchandra Basu, Stri Diger Prati first cohabitation enjoined by the shastras. It will. ...When I cried out he kicked me in the Upadeslh, Calcutta, n d; Kamakhya Charan is the injunction of the Hlindu shastras that abdomen. My husband does not support me. Bannerji, Stri Shiksha, Dacca, 1901; married girls must cohabit with their hus- He rebukes and beats me. I cannot live with Monomohan Basu, Hindur Achar bands on the first appearance of their menses him. VRYavahar, Calcutta 1872; Chandranath and all Hindus must implicitly obey the in- junction. And he is not a true Hindu who doesThe husband was discharged by the British not obey it...If one girl in a lakh or even a magistrate and the girl was restored to crore menstruates before the age of twelve it him.94 must be admitted that by raising the age of consent the ruler will be interfering with the Basu, Garlhast/iya Pat/i, Calcutta 1887; Bhubaneswar Misra, Hindu Viva/ha Samaloclhan, Calcutta 1875; Tarakhnath Biiswas Bangiya Mahila, Calcutta 1886; Anubicacliaran Gupta, Grilhastha Jivan, Notes Calcutta 1887; Narayan Roy, Bangamahila, n d, Calcutta; Chandrakumar religion of the Hindus. But everyone knows that hundred of girls menstruate before the age of twelve. And garbhas (wombs) of hundred of girls will be tainted and impurc. And the thousands of children who will be born of those impure garbhas will become impure 1 1 use the term 'militant nationalism' in a Bhattacliarya, Bangavivaha, Calcutta somewhat unconventional sense here: not 1881; Pratapchandra Majumdar, Stri as a part of a dcefinitc and continuous C/aritra, Calcutta n d; Purnachandra historical trend but as a moment of absoGupta, Banigali Bau, Calcutta 1885; and lute and violent criticism of foreign rule many others. and lose their rights to offer 'pindas' lanicesthat was developed by a group of Hindus 12 See the preponderance of this theme in tral offeringsj."94 the collection Of W C Archer, Bazaar in the late 1880s and e.rly 1890s, largcly Economic and Political Weekly September This content downloaded from 14.139.45.242 on Fri, 16 Aug 2024 08:40:01 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 4, 1993 1877 Paintings of Calcutta, London, 1953. 13 See, for instance, plots in the novels of Bankimchandra, Bankinm Rachanabali, Vol 1, Calcutta. 33 See SumitSarkar, 'The Kalki-Avatar of 57 Sanibad Prabhakar, June 30, 1887, RNP Bikrampur: A Village Scandal in Early Bcngal, 1887. 58 Bangabashti, June 25,1887, RNP Bengal, 20th Century Bengal' in Ranajit Guha (ed), Suibaltera Studies VI, Delhi, 1989. 1887. 59 Nababibhakar Sadhtarani, July 18,1887, RNP Bengal, 1887. 34 See Tanika Sarkar, Nationalist Iconogra15 See, for instancc, Sir William Markby, phy. 60 Dacca1Prakash, June 8, 1875, RNP BenFellow, Balliol College an(d erstwhile gal, 1A75. 35 Report of the Age of Consent Comimittee, judge in Calcutta HIigh Court, Ilindu and 61 Education Gazette, May 11, 1873, RNP 1928-29, Government of Bengal, Calcutta Mohamnmadant Law, 1906, Delhi, 1977, 1929. For some statistical observations Bengal, 1873. pp 2-3. on this matter, see pp 65-66. 62 Heimsath, op cit 16 See, frequent references to the Queen's 36 Kamlakanter Daptar. 63 Bengal Government Judicial J C/17/, Proclamation in the agitational writings 37 Tanika Sarkar, Bankimchandra and the Proceedings 96-102, 1892, Nos 101-02. in the nationalist press, RNP Bengal, Imipossibility of a Political Agenda: A 1887-91. File J C/17-5. Honourable justice Wilson's charge to jury in the case Predicament for 19th Century Bengal, 17 Markby, op cit, for a convergence of the views of -this Orientalist scholar-cumEmpress vs Main Mohan Maitee, CalNMML Occasional Papers, Second Secutta High Court. Report sent by Arcar, colonial judge with Hindu Legal opinion, ries, No XL, 1991 Clark of the Crown, High Court, Calcutta, compare him with Sripati Roy, Ctustonts38 Bangabashi, July 9, 1887, RNP Bengal 1887. For a critical discussion of such antd Cutstomary Law in Britislh India, to officiating chief secretary 90B, views see Rabindranath Tagore, Hindu No 6292-Calcutta, September 8, 1890. Tagore Law Lectures-, 1908-09, reprinted Vivaha, 1294. Rabindranath, himself, in 64 See Rajat Kanta Ray. in Delhi 1986, pp 2-6. this extremely involuted logical exer17a See J D N Derrett, Religioni, Law and the 65 Bengal Government Judicial NF J C/17/, State in India, London, 1968. cise, grants a practical purpose to infant Proceedings 104-17, June 1893. From 18 For a clarification of the notion of unwritmarriage purely for better breeding purSimmons, honorary secretary, Public poses but, in the process, Hindu conI-lealth Society of India to chief secreten law, see Robert M Ireland, TheLiberjugality is denied all effective orspiritine Mlust Die: Sexuial Dishonour and the tary, Government of Bengal, Calcutta tua l pretensions. RabindraRachanabali, September 1, 1890. Unwritten Law in thte 191/i Centur) United Vol 12, Calcutta, 1349. 66 Ibid, C C Stevens, officiating, chief secStates, Journal of Social History, Fall 1989. 39 Chandrakanta Basu, Hindui Patni and retary 90B, to secretary, home depart19 The Bengalee, March 7, 1873. Hindu Vivaha Bayas 0 Uddeshya, cited ment, Government of India, Darjeeling, 20 Markby, op cit, p 100. in Hindu Vivaha, op cit, also by the same November 8, 1890. 21 This relates to a case involving the disauthor, Hhinduttva, op cit. 67 Letter from Simmons, op cit. position of a Shalgram-shila in case of 40 See for instance Prasad Das Goswami, 68 Bengal Government Judicial, J C/17/, Surendranath Bannerjee vs the chief op cit, Bhubaneshwar Misra, op cit, op cit. justice and judges of the high court at Kalimoy Ghatok, Ami, Calcutta 1885. 69 Bengal Government Judicial, NF J/C/ Fort William, July 1883. See an account 41 Monomohan Basu, op cit. 171, op cit. in Subrata Choudhary, 'Ten Celebrated 42 Manmohan Basu, op cit. 70 McLeod'sMedicalReporton ChildWives Cases Tried by the Calcutta High Court' 4-3 Sulabh Samachar 0 Kushadahe, July 22, Bengal Government Judicial, ibid. in the High Coutrt at Calcutta, Centenary 1887, RNP Bengal, 1887. 71 Ibid. Souvenir 18Q.2-1962, Calcutta, 1962. 44 Far from invariably evoking a sense of 72 Ibid. 22 Sharmila Bannerjee, Studies in the Adsuperiority and disgust among English73 The Bengalee, March 21, 1891. ministrative History of Bengal, 1880men, the spectacle would very often 74 Dagmar Engels, op cit. 1989, New Delhi, 1978, pp 151-55. arouse similar sentiments. Compare a 75 Surabhi 0 Patrika, January 16, 1891, 23 Cited in The Bengalee, April 26, 1873. description of a marriage procession by RNP Bengal 1891. 24 See extracts from Murshidabad Patrika, an English tourist with our earlier ac76 The Bengalee, March 21, 1891. Dacca Prakash and the Education Gacount: 'It was the prettiest sight in the 77 Dainik 0 Saniachar Chandrika, January zette in April 1875, RNP Bengal. world to see those gorgeously dressed 14, 1891, RNP Bengal, 1891. 25 See Philippa Levine, VictorianFeminism, babies...passer-bys smiled and blessed 78 Nabayug, January 15,1891, RNP Bengal, 1850-1900, London 1987, pp 128-43. the little husband and the tiny wife'; John 1891. Also see Holcombe, Wives and PropLaw, Glimpses of hIidden India, Calcutta79 Dainik 0 Samnachar Chandrika, April 15, erty-Reform of tIhe Married Women's circa 1905. 1896, RNP Bengal, 1891. Property Law in 19th Century England, 45 The Hindoo Patriot, July 25, 1887. 80 Nabayug, op cit. Oxford 1983. 46 Ibid, August 16, 1887. 81 Bangabashti, March 21, 1891, RNP Ben26 Markby, op cit, p 100. 47 Ibid, September 12, 1887. gal, 1891. 27 Mendus and Rendall (eds),Sexuality and 48 Ibid, August 1, 1887. 82 Ibid. Subordination, Interdisciplinary Studies 49 Surabhi 0 Patrika, January 16, 1887, 83 See Amiya Sen, op cit. of Genders in the 19th Century, RKP, RNP Bengal, 1887. 84 Mentioned in The Bengalee, March 7, 1989, p 133. 1891. 50 Nistarini Devi, Sekaler Katha, first pub28 See also Holcombe, Victorian Wives and lished serially in Blharatbarsha between 85 Tlte Bengalee, February 28, 1891. Property: Reform of the Married 1913-14. Jana and Sanyal (eds), 86 Ibid, March 21, 1891. Wonmen's Property Law, 1857-82 in Atnmakatlla, Calcutta, 1982, p 87 11Bangabashi, March 28, 1891. Martha Vicinus, A Widening Sphere: 5 1 Chandrakanta Basu, op cit. 88 Ibid. Chtaniginig Roles of Victorian Womneni, 52 Tte IIinidooPatriot, Septenbe r 19, 1887. 89 Dainik 0 Santachar Chandrika, January London. 53 Cited in The IIintdoo Patr-iot, ibid. 15, 1891. 29 Markby and Sripati Roy, op ciL 54 Dainwik 0 Saniaclhar Chiandrika, June 22,90 Bangabashi, December 25, 1890. 30 The Amrita Bazar Patrika, February 4, 1857. Also Dacca Prakash. 91 Dainik 0 Sarnacliar Chlanidrika, January 14 Prasad Das Goswami, op cit. 1873. 55 Bardhawani Sanjiv'aii, July 5. 1887, RN II 14, 1891. 31 Thte Ilindoo Pafriot, August 16, 1887. Bengal, 1887. 92 Ibid, January J11, 1891. 32 Tfhe Amrita Ba-ar Patrika, January 28, .56 Dihrntkcu, July 4, 1887, RNP l3cngal.93 Ihid. 1887. 1875, RNP' Bengal, 1875. 94 ThXe Ben galee, Jully 25, 1891 . 1878 Economic and Political Weekly September 4, 1993 This content downloaded from 14.139.45.242 on Fri, 16 Aug 2024 08:40:01 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms