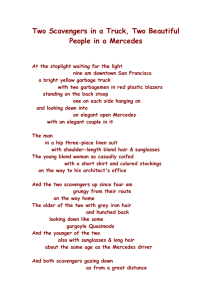

For the exclusive use of A. Ooi, 2024. KEL048 Revised May 12, 2011 DANIEL DIERMEIER Mercedes and the Moose Test (A) In October 1997 Mercedes-Benz launched the A-Class, the first-ever Mercedes car targeted to the middle-market segment. It combined the internal comfort and space of a minivan with the dimensions of a compact car. The project represented not only a breakthrough in innovative car design but also a major strategic and technological bet for Mercedes. Significant risks were involved in extending the luxury brand into a lower segment, targeting younger customers, employing a new development process, and initiating Mercedes-Benz’s first front-wheel-drive design. The product development and new production plant cost an estimated DM 2.5 billion ($1.4 billion) and lasted forty-seven months. In order to attract a new generation of customers to its showrooms, Mercedes ran an eighteenmonth, DM 200 million ($115 million) marketing campaign.1 It attracted more than half a million Europeans to its special public events in nineteen European cities—part of Mercedes-Benz’s “AMotion Tour.” The new car’s official launch on October 18, 1997, was highly anticipated. Mercedes had already recorded 100,000 pre-booked sales,2 and almost everyone knew about the new “Baby Benz.” On October 21, 1997, three days after the European launch of the A-Class, Swedish journalist Robert Collin experienced a rollover in the car while performing a so-called “moose test,” a safety assessment that was part of a review for the Swedish car and technology magazine Teknikens Värld. This test was supposed to simulate an emergency swerving maneuver to avoid a moose on the road, a problem common in Sweden but unheard of in Germany. In the following days, news of the crashed car spread rapidly through all the major European newspapers. The Mercedes top management team was attending the Japan Auto Show at the time and was not prepared to react or comment on the incident. As unfavorable news coverage quickly increased, the leadership at Mercedes recognized that the situation was quickly turning into a crisis. Daimler-Benz AG Mercedes-Benz is a division of Daimler-Benz AG, one of the largest industrial groups in Europe. In 1997 the Daimler-Benz conglomerate consisted of four main divisions: automotive (Mercedes-Benz), aerospace (DASA), financial services (debis), and an electronics division encompassing a number of segments. Total sales for Daimler-Benz in 1995 were DM 109 billion 1 2 Handelsblatt, November 11, 1997. Automotive News, November 17, 1997. ©2003 by the Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University. This case was prepared by Professor Daniel Diermeier and Astrid Marechal ’02. It is based on publicly available information including the book Die A-Klasse by Armin Töpfer (1999). Cases are developed solely as the basis for class discussion. Cases are not intended to serve as endorsements, sources of primary data, or illustrations of effective or ineffective management. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, call 800-545-7685 (or 617-783-7600 outside the United States or Canada) or e-mail custserv@hbsp.harvard.edu. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, used in a spreadsheet, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the permission of the Kellogg School of Management. This document is authorized for use only by Andrea Ooi in Ethics and Corporate Responsibility 2024-2025 taught by ABHIJEET K. VADERA, Singapore Management University from Aug 2024 to Jan 2025. For the exclusive use of A. Ooi, 2024. MERCEDES AND THE MOOSE TEST (A) KEL048 ($62 billion), 66 percent of which came from the automotive division. In 1997 the company was in the process of completing a heavy restructuring effort, led by Jürgen E. Schrempp, who had become chairman of Daimler’s management board (CEO) in 1995. This restructuring improved core competencies related to quality, development time, cost, and innovation; it also supported Daimler’s plans for an increased global presence.3 Daimler’s car operations were headed by Jürgen Hubbert, the truck division by Kurt Lauk, and the marketing division by Dieter Zetsche. All three were to become members of the DaimlerBenz board in 1998. P Mercedes-Benz had always been known for its luxury cars. During the mid-1990s Mercedes managed to secure a position as a premium brand in the competitive European market. Offering several models (see Exhibit 1) for different segments of the automotive market provided Mercedes with increased production and sales. Two-thirds of sales were made in Europe, and one-third occurred within Germany itself. Of the total luxury car market in Europe, representing 1.6 million vehicles, Mercedes had a 24.4 percent market share, followed by BMW and Audi with 20.7 percent and 20.5 percent respectively (see Exhibit 2). Mercedes also expanded its presence globally by opening its first foreign plant in the United States in 1995 with the purpose of assembling the M-Class. Worldwide, the Mercedes brand stood for superior technology, outstanding quality and service, and advanced safety standards. It attracted mostly middle-aged male customers. 4 T The prevailing trends in the industry favored more globalization and consolidation in order to take advantage of economies of scale and scope, as well as technological learning curves. Many manufacturers had also started to expand their product lines into upper or lower markets. For example, BMW had acquired the Rover group to gain access to lower- and middle-market segments. Mercedes was starting to feel the pressure from its competitors, who were also pushing down the margins of the luxury car segment through aggressive pricing. Jürgen Hubbert summarized the situation as follows: “We were in danger of falling into a positioning trap. If we had been content with the small number of sales for the S-Class (49,996 in 1996), we would end up in the same corner as Rolls Royce—an existential crisis for the corporation.”5 In order to remain competitive, Mercedes decided to apply a trade-down strategy and enter the compact-car market with the A-Class. The company’s goals were as follows: 1. Complete its product portfolio by entering the middle market and protecting the Mercedes brand against the activities of competitors. 2. Target new and younger customer groups, especially women, with the strong belief that once they had become Mercedes customers, brand loyalty would move them to higher-margin products in the future. (It was a common belief within the automobile industry that it was six times more expensive to acquire a customer than to retain him or her.) 3 Automotive News, January 20, 1997. Ninety percent of Mercedes customers were males between 40 and 60 years old (Automotive News Europe, February 2, 1998). 5 AutoForum 10 (1997): 126. 4 2 KELLOGG SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT This document is authorized for use only by Andrea Ooi in Ethics and Corporate Responsibility 2024-2025 taught by ABHIJEET K. VADERA, Singapore Management University from Aug 2024 to Jan 2025. For the exclusive use of A. Ooi, 2024. KEL048 MERCEDES AND THE MOOSE TEST (A) 3. Take advantage of economies of scale and scope in purchasing and distribution. Mercedes, however, would not apply a common platform strategy as used, for example, by Volkswagen. Rather, virtually all parts would be specifically designed for the smaller model. The A-Class was designed to compete in the European market against such popular models as the Volkswagen Golf, Renault Scenic, GM/Opel Astra, Ford Escort, and other European and Japanese models (see Exhibit 3). The first concept car, called “Vision A,” was initially shown in 1993 in Frankfurt. The launch of the A-Class was planned for October 1997, with the start of full production scheduled for July 1997 in a new plant in Rastatt, Germany. In order to ensure the success of the project, the company planned to leverage the strong brand image and technological capabilities of Mercedes, as well as to take advantage of economies of scope. It would limit the risk of diluting the brand and confusing existing customers by emphasizing the A-Class’s strong adherence to Mercedes core values. Targeting younger and less wealthy segments would limit the risk of cannibalizing existing sales. Completing the portfolio with a smaller car would also help Mercedes meet company-wide environmental regulations, and better position Mercedes in various global markets since the smaller car would fit in well with the needs of emerging countries in Asia and Latin America. Production in Brazil, for example, was planned to start in early 1999. In addition to introducing the A-Class and renewing existing models, Mercedes-Benz’s product strategy included the 1998 introduction of the Smart car. This revolutionary two-seater city car had been developed in partnership with Swatch, the Swiss watch company, but was not marketed as a Mercedes. On the high end of the portfolio, Mercedes planned to launch an ultraluxury car in 2002, reviving the Maybach name, a famous car brand from the past, in order to compete with Rolls Royce and Bentley (see Exhibit 4) . T T The A-Class Project Due to its concept and dimensions, the A-Class was a unique project for Mercedes and for the automotive industry. Moreover, the car’s launch campaign created unprecedented media resonance and potential customer interest. Concept/Target As part of the new A-Class concept, Mercedes wanted to offer a vehicle with small car size, middle-market car space and safety, and the versatility of a van, completely supported by Mercedes’s reputation for quality. The company projected that its product could appeal to 1.25 million people every year, and planned to sell 200,000 cars in 1998, the first full year of production. Mercedes expected that 80 to 90 percent of A-Class customers would be new to the franchise, and 50 percent of them would be women (compared to 10 to 20 percent of existing customers). The car would also appeal to young families and singles (“trendsetters”), as well as families and couples needing a second car. KELLOGG SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT 3 This document is authorized for use only by Andrea Ooi in Ethics and Corporate Responsibility 2024-2025 taught by ABHIJEET K. VADERA, Singapore Management University from Aug 2024 to Jan 2025. For the exclusive use of A. Ooi, 2024. MERCEDES AND THE MOOSE TEST (A) KEL048 Brand Mercedes considered launching the new car under a new brand name, following the approach used for the Smart car, but concluded that the benefits of sharing the Mercedes brand (reduced initial marketing costs and transfer of positive image associations) outweighed the risks (overextension of the brand and negative impact on quality image because of a lower-class product). The new car was designed to complement the Mercedes image in terms of customer enjoyment and innovation, as well as reinforce the brand’s core values. As Dieter Zetsche, the head of marketing, stated, “The A-Class is a symbol of departure and transformation of the whole company. Not only does it represent an unusually high level of innovation, but it also shows that potential for change resides in this brand and the company as a whole.”6 Product Development Process Increasing competition in the automotive industry required manufacturers to optimize quality, time, and cost in the development process. During the 1980s Japanese manufacturers (e.g., Toyota) had been successful in significantly reducing development and manufacturing time. However, while new Japanese cars usually involved the redesign of one-third of the parts compared to two-thirds for European cars, the A-Class’s share of new parts would be much larger. For a brand like Mercedes, known worldwide for its safety, quality, and technology, decreasing development time implied significant risks. At the same time Mercedes leadership maintained the belief that what mattered to the customer was the product’s end quality. Ultimately the A-Class was developed in a shorter time than any other Mercedes before it. The engineers took only forty-seven months to come up with the first version, compared to the usual fifty-nine months for other models. Also, for the first time in testing a new model, intensive computer simulations were used to complement the real-conditions driving tests. The design requirements for the A-Class specified that it offer the safety of a middle-market car, the space for five people, the flexibility and consumption of a small car, and the driving pleasure and comfort that typified Mercedes—all at an affordable price. Of course, some of these requirements were in conflict. The necessity for trade-offs was even more obvious because of the pressure to cut costs and the limited freedom in designing a small car. The A-Class team managed to solve some of these conflicts by introducing an innovation called the “sandwich concept” which greatly increased accident safety within the dimensional limitations of the car. The sandwich concept allowed the engine to slide under the driver and passenger seats in the event of a frontal crash, thus limiting direct impact. An additional advantage of this new design was the higher seating position, which could increase occupant comfort and overall visibility. However, one of the side effects of the concept was the A-Class’s higher center of gravity which could potentially reduce the stability of the vehicle on curves. In April 1993 Mercedes developed several chassis configurations in order to find the most promising for testing in real conditions. Tests such as steering for emergency avoidance, driving under heavy side winds, and double lane-changing at fast speed (as in the moose test) were conducted via computers. Computer simulations were seen as an important tool for reducing 6 Automobil-Produktion, special issue “Mercedes-Benz A-Klasse” (1997): 46. 4 KELLOGG SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT This document is authorized for use only by Andrea Ooi in Ethics and Corporate Responsibility 2024-2025 taught by ABHIJEET K. VADERA, Singapore Management University from Aug 2024 to Jan 2025. For the exclusive use of A. Ooi, 2024. KEL048 MERCEDES AND THE MOOSE TEST (A) development time and cost by helping to select the most promising designs. It was, however, impossible to completely account for real-life interactions among chassis, rims, tires, and road, as well as their impact on ergonomics and noise. In December 1993 the board accepted the decision to build the new car in a refurbished plant in Rastatt. From April 1995 until the launch, the first prototypes were driven all around the world, covering more than 5 million kilometers in addition to the 2.5 million kilometers in test drives by Daimler-Benz employees. In September 1995 the first crash tests were conducted; the success of the sandwich concept led to the November 1996 pre-series production start in Rastatt. In March 1997 the A-Class world premiere took place in Geneva. Finally, in July 1997 full production began in preparation for the official launch on October 18. Overall, an estimated total of DM 2.5 billion ($1.4 billion) had been invested in the development of the new car and its production. Launch and Marketing Campaign The launch and marketing campaign for the A-Class were of unprecedented scope for Mercedes and the industry; the eighteen-month pre-launch campaign cost about DM 200 million ($115 million). The main goal of the campaign was to position Mercedes as an innovative, futureoriented company. It was specifically targeted to new customer segments, consumers who usually would not have considered Mercedes (e.g., younger and female drivers). The length of the campaign was based on Mercedes-Benz’s belief that the typical delay between the first thought about buying a new car and the actual purchase was about two years. Thus new customers were encouraged to delay buying a competitive product and consider the new A-Class instead. Potential customers were also allowed time to gain trust in this new product, which did not look like any existing vehicle as it combined the look of a minivan with the size of a compact car. Pre-marketing started in 1993 with the presentation of the concept car at the Frankfurt Autoshow. In order to optimally reach the new target group and communicate the value of the new car, a four-stage communication strategy was designed, using TV, newspapers, and the Internet, along with direct mail:7 1. Big Bang. From May to November 1996 only pictures of schematic representations were published, along with the message, “A strong piece of the future.” 2. New Perspectives. From July 1996 to May 1997 Mercedes allowed disclosure of more details about the A-Class with the message, “A true Mercedes in 3.6 meters.” 3. New Choices. From May 1997 to October 1997 the company initiated the Europe-wide AMotion Tour with the message, “The A-Class comes to the people.” 4. New Experiences. From September 1997 until the product launch on October 18, 1997, the image campaign for Mercedes utilized extensive TV and newspaper advertising in order to communicate the messages, “Drive the future of the automobile,” and “We believe in the next 7 Armin Töpfer, Die A-Klasse (Neuwied, Germany: H. Luchterhand, 1999): 107. KELLOGG SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT 5 This document is authorized for use only by Andrea Ooi in Ethics and Corporate Responsibility 2024-2025 taught by ABHIJEET K. VADERA, Singapore Management University from Aug 2024 to Jan 2025. For the exclusive use of A. Ooi, 2024. MERCEDES AND THE MOOSE TEST (A) KEL048 generation.” The intention was to renew the image of Mercedes with a focus on change and continuous innovation. The advance campaign also included a gathering of 1,400 automotive journalists in Brussels over a six-week period of test drives. The purpose of the gathering was to communicate the novelty and innovative character of the new car, as well as its strong association with the Mercedes brand. Based on psychodemographic data, the advertising strategy was specifically aimed at three sub-segments of the target market, representing 46 percent of that overall group. It was believed that some of the existing customers would also consider the A-Class, either as a second “city car” or because they would appreciate some of the distinguishing features of the new vehicle such as the higher seating base. The two earliest phases of the campaign reached the new customer segments through ongoing communications. Via a survey, Mercedes had identified 400,000 interested people in Germany and regularly communicated with this group over the eighteen months by sending newsletters and price lists. The advance market introduction price for the A-Class had been fixed at DM 30,000 to DM 35,000 ($17,100 to $19,950). Six thousand interested respondents were intensively interviewed, with results showing that 80 percent of them were new to Mercedes. Most owned compact cars, predominantly VW Golfs, but also BMWs and Japanese cars. Also, compared with the typical Mercedes buyer, a higher percentage of the interested respondents were women.8 Another innovative marketing technique was Mercedes-Benz’s “A-Motion Tour,” which visited fourteen German and five other European cities. It included a large stage placed in the center of the cities where customers could obtain information and see the new models; it also featured workshops, talk shows, and debates about new driving concepts and cars of the future. In the evening, the setting was transformed into a show with music, lights, and fire/smoke effects. The A-Motion Tour attracted more than half a million people at an estimated cost of DM 50 million ($28.5 million). The Moose Test The A-Class was launched on October 18, 1997, and quickly generated more than 100,000 pre-orders. Three days later, on October 21, 1997, the A-Class failed the moose test conducted by journalists from Teknikens Värld. The test consisted of a quick, double-lane change within a specific distance. It took place at an approximate speed of 65 kilometers per hour without braking. Although the moose test was not required for vehicle certification in any European country, similar tests were compulsory, such as various avoidance maneuvers (which permitted braking). The A-Class had passed all of these mandatory tests. However, during the Sweden moose test, the “Baby Benz” became unstable, leading to a rollover. One of the passengers was slightly hurt and news of the incident quickly reached a wide European audience. Mercedes had received some prior warning signs about the possible instability of its new car. On September 23, 1997, an A-Class had lifted two wheels from the ground in an avoidance test. 8 P. Stippel, “Lasst uns zu den Menschen gehen,” Absatzwirtschaft 40, no. 6 (1997): 18–19. 6 KELLOGG SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT This document is authorized for use only by Andrea Ooi in Ethics and Corporate Responsibility 2024-2025 taught by ABHIJEET K. VADERA, Singapore Management University from Aug 2024 to Jan 2025. For the exclusive use of A. Ooi, 2024. KEL048 MERCEDES AND THE MOOSE TEST (A) Despite numerous attempts, the Mercedes experts had been unable to reproduce the same test results and concluded that the A-Class design was sound. After the test in Sweden, Mercedes conjectured that the moose test failure could be attributed to the tires supplied by Goodyear. Because the tires were believed to be too “sticky” in terms of grip to the road, they might have led to sliding when friction was suddenly lost. The tires were designed to be especially soft to enhance driving comfort but in extreme steering situations this softness could lead to the rim briefly touching the road, which could then cause the car to tilt. Goodyear had, however, supplied the tires precisely to Mercedes specifications and could thus be expected to contest a tire-based explanation. The testing conditions in Sweden were another concern for car operations chief Hubbert and Mercedes engineers. They suspected that almost any car would fail the test under the conditions that were used: a heavily loaded vehicle, a very sticky surface (airbase asphalt), uncontrolled settings, an unrealistic situation (avoiding objects without braking, an unnatural reaction for all but specially trained drivers), and a demanding steering wheel rotational speed (observed only by professional drivers).9 Their suspicions were supported by internal studies conducted by Mercedes since 1978. Finally, there were no standards for the moose test, even though manufacturers such as Opel and Saab conducted it regularly on all new cars, and Ford and Volkswagen performed a similar test. After investigating the issue, engineers at Mercedes were convinced that if a problem existed at all, it could be resolved with modified tires and perhaps some minor adjustment to the car’s driving position. Another option was a brand-new electronic stability program (ESP) system, which had recently been introduced as standard on Mercedes luxury cars.10 For the A-Class it was supposed to be offered only as an option starting in mid-1998 and at a price of about DM 2,250 ($1,300). ESP provided extra safety in crucial situations and significantly reduced the danger of skidding during turns. However, Mercedes engineers believed that with respect to the moose test, the additional benefits of adding ESP would be negligible, provided the above-mentioned adjustments were implemented. T Regardless of the decision about next steps, rising media coverage and public concern in late 1997 necessitated a response from Mercedes and a plan of action for moving forward with the AClass. T 9 Swedish test drivers frequently would cross their arms to improve rotational speed (Töpfer, 132). Like the antilock braking system that also made its world premiere in a Mercedes, the ESP was a milestone. The system helped to stabilize a car even in extreme driving situations. The ESP’s secret was an intelligent on-board computer that constantly received information about driving conditions through sensors. Whenever the danger of instability was detected, the system reacted by selectively braking the front and rear wheels and reducing or increasing engine torque, thus helping the car to stay on course. 10 KELLOGG SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT 7 This document is authorized for use only by Andrea Ooi in Ethics and Corporate Responsibility 2024-2025 taught by ABHIJEET K. VADERA, Singapore Management University from Aug 2024 to Jan 2025. For the exclusive use of A. Ooi, 2024. MERCEDES AND THE MOOSE TEST (A) KEL048 Exhibit 1: Mercedes Product Portfolio, September 1997 U Segment Mini-car Compact Lower luxury Mid-luxury Upper luxury Super luxury Roadster Coupe/Cabrio Van All-road Sports utility vehicle (SUV) Existing Planned Smart (1998) A-Class (1997) C-Class E-Class S-Class Maybach (2002) SL, SLK CL, CLK V-Class G-Class M-Class CLK – Cabrio (1999) Source: Armin Töpfer, Die A-Klasse (Neuwied, Germany: H. Luchterhand, 1999). Exhibit 2: Western European Car Sales, Luxury Market, 1997 Lower luxury segment Audi A4 Mercedes C-class BMW 3 series Volvo S40/V40 Rover 600 Saab 900 Alfa 155/156 Mazda Xedos 6 Total lower luxury Mid-luxury segment Mercedes E-class BMW 5 series Audi A6 Volvo S70/V70 GM Omega Volvo S90/V90 Renault Safrane Ford Scorpio Saab 9000 Lancia Kappa Total mid-luxury Upper luxury segment BMW 7 series Mercedes S-class Jaguar XJ series Audi A8 Lexus LS400 Rolls Royce (all) Honda Legend Daimler (all) Chrysler Vision Cadillac (all) Total upper luxury Grand total luxury Mercedes BMW Audi Volvo GM Saab Rover 1997 Unit Sales Market Share (%) 231,738 198,224 161,668 100,980 37,526 34,653 15,585 3,982 784,356 14.3 12.2 10.0 6.2 2.3 2.1 1.0 0.2 48.3 184,404 152,936 90,127 89,555 74,641 33,356 28,557 19,489 18,279 17,256 779,143 11.4 9.4 5.5 5.5 4.6 2.1 1.8 1.2 1.1 1.1 48.0 21,228 13,791 11,911 10,417 1,462 1,053 1,066 609 600 322 61,205 1,624,704 397,028 335,832 332,282 190,535 74,641 52,932 37,526 1.3 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 3.8 24.4 20.7 20.5 11.7 4.6 3.3 2.3 Source: Automotive News Europe 3, no. 3 (February 2, 1998): 15. 8 KELLOGG SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT This document is authorized for use only by Andrea Ooi in Ethics and Corporate Responsibility 2024-2025 taught by ABHIJEET K. VADERA, Singapore Management University from Aug 2024 to Jan 2025. For the exclusive use of A. Ooi, 2024. KEL048 MERCEDES AND THE MOOSE TEST (A) Exhibit 3: Western European Compact Car Sales, 1997 U 1997 Unit Sales Market Share (%) VW Golf 507,657 GM Astra 496,179 13.5 13.2 Renault Megane 478,655 12.7 Ford Escort 419,719 11.1 Peugeot 306 296,138 7.9 Fiat Bravo/Brava 145,134 3.9 Honda Civic 144,686 3.8 Rover 200 129,449 3.4 Citroen ZX 123,816 3.3 Toyota Corolla 123,353 3.3 Total 3,768,695 Source: Automotive News Europe 3, no. 3 (February 2, 1998): 15. Exhibit 4: The New Maybach and Smart Cars MAYBACH SMART KELLOGG SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT 9 This document is authorized for use only by Andrea Ooi in Ethics and Corporate Responsibility 2024-2025 taught by ABHIJEET K. VADERA, Singapore Management University from Aug 2024 to Jan 2025.