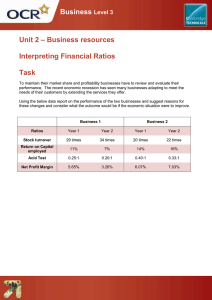

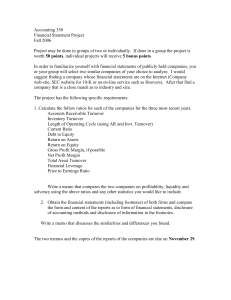

Interpreting Published Accounts What is ratio analysis? Analysing relationships between financial data to assess the performance of a business Ratios can help answer Q’s like… Profitability Financial efficiency Liquidity and gearing Shareholder return Is the business making a profit? Is it growing? How efficient is the business at turning revenues into profit? Is it enough to finance reinvestment? Is it sustainable (high quality)? How does it compare with the rest of the industry? Is the business making best use of its resources? Is it generating adequate returns from its investments? Is it managing its working capital properly? Is the business able to meet its short-term debts? Is the business generating enough cash? Does the business need to raise further finance? How risky is the finance structure of the business? What returns are owners gaining from their investment? How does this compare with alternative investments? Profitability ratios Gross Profit Margin * Operating Margin * ROCE * Covered in BUSS2 Return on Capital Employed ROCE (%) = Operating profit Capital employed x 100 Example Operating profit = £280,000 Capital employed = £1,400,000 ROCE = £280,000 / £1,400,000 = 20% Evaluating ROCE Higher % is better ROCE % Watch for trend over time Watch out for low quality profit which boosts ROCE Leased equipment will not be included in capital employed Financial efficiency ratios Assess how effectively a business is managing its assets Financial efficiency ratios Asset turnover Stock turnover Debtor days Creditor days * Covered in BUSS2 Asset turnover Asset turnover = Revenue (sales) Net assets Example Revenue = £21,450k Net assets = £4,455k Asset turnover = 4.8 times Evaluating asset turnover • A rough guide to how intensively a business uses its assets • Some limitations of the ratio: – Takes no account of how profitable the revenue is – Less relevant for labour-intensive businesses – Will vary widely from industry to industry – Can fluctuate from year to year (e.g. major investment in fixed assets in one year generates increased sales in following years) Stock turnover Stock turnover = Cost of sales Average stock held Example Cost of sales = £13,465k Average stock = £1,325k Stock turnover = 10.2 times Evaluating stock turnover • Interpreting the number – In general, a higher number is better – Low number (compared with previous period or competitors) suggests problem with stock control • Some issues to consider: – Stock turnover varies from industry to industry – Holding more stock may improve customer service & allow the business to meet demand – Seasonal fluctuations in demand during the year may not be reflected in the calculations – Stock turnover is irrelevant for many service sector businesses (but not retailers, distributors etc) Actions to improve stock turnover • Sell-off or dispose of slow-moving or obsolete stocks • Introduce lean production techniques to reduce stock holdings • Rationalise the product range made or sold to reduce stock-holding requirements • Negotiate sale or return arrangements with suppliers – so the stock is only paid for when a customer buys it Debtor days Debtor days = Trade debtors Revenue (sales) Example Revenue = £21,450k Trade receivables = £4,030k Debtor days = 68.6 days x 365 Evaluating debtor days • Interpreting the results: – Shows the average time customers take to pay – Each industry will have a “norm” – Need to take account of terms & conditions of sale – The important data is any significant change • Look out for – Comparisons (good or bad) v competitors – Balance sheet window-dressing Creditor days Creditor days = Trade payables Cost of sales Example Cost of sales = £13,465k Trade payables = £2,310k Creditor days = 62.6 days x 365 Evaluating creditor days • Interpreting the results – In general, a higher figure is better – Ideally, creditor days is higher than debtor days – Be careful: a high figure may suggest liquidity problems • Look out for: – Evidence from the current ratio or acid test ratio that business has problems paying creditors – Window-dressing: this is easiest figure to manipulate Liquidity ratios Assess whether a business has sufficient cash or equivalent current assets to be able to pay its debts as they fall due Current ratio Current ratio = Current assets Current liabilities Example Current assets = £6,945k Current liabilities = £3,750k Current ratio = 1.85 Evaluating the current ratio • Interpreting the results – Ratio of 1.5-2.0 would suggest efficient management of working capital – Low ratio (e.g. below 1) indicates cash problems – High ratio: too much working capital? • Look out for – Industry norms (e.g. supermarkets operate with low current ratios because they low debtors) – Trend (change in ratio) is perhaps most important Acid test ratio Acid test ratio = Current assets less stocks Current liabilities Example Current assets = £5,620k Current liabilities = £3,750k Acid test ratio = 1.50 Evaluating the Acid test ratio • Interpreting the results – A good warning sign of liquidity problems for businesses that usually hold stocks – Significantly less than 1 is often bad news • Look out for – Less relevant for business with high stock turnover – Trend: significant deterioration in the ratio can indicate a liquidity problem Gearing ratio Gearing (%) = Long-term liabilities Capital employed x 100 Example Long-term liabilities= £1,200k Capital Employed = £5,655k Gearing ratio = 21.2% Evaluating the gearing ratio • Interpreting the result – Focuses on long-term financial stability of business – High gearing (>50%) suggests potential problems in financing (interest & capital repayments) • Look out for – Increased gearing & deterioration in other liquidity and/or financial efficiency ratios Managing Gearing Reduce Gearing Increase Gearing Focus on profit improvement (e.g. cost minimisation Focus on growth – invest in revenue growth rather than profit Repay long-term loans Convert short-term debt into longterm loans Retain profits rather than pay dividends Buy-back ordinary shares Issue more shares Pay increased dividends out of retained earnings Shareholder ratios Measure the returns that shareholders gain from their investment Dividend per share Dividend per share (£) = Total dividends paid Number of ordinary shares in issue Example Dividends paid = £460,000 Number of shares = 500,000 Dividend per share = £0.92 Evaluating dividend per share • Interpreting the results – A basic calculation of the return per share • The problem with this ratio: we don’t know – How much the shareholder paid for the shares – i.e. what the dividend means in terms of a return on investment – How much profit per share was earned which might have been distributed as a dividend Dividend yield Dividend per share (pence) Dividend per share (£) = Share price (pence) Example Dividend paid in 2009 = 92 pence Average share price = 1,415 pence Dividend yield = 6.5% Evaluating dividend yield • Interpreting the results – Annual yield can be compared with: • Other companies in the same sector • Rates of return on alternative investments – Shareholders look at dividend yield in deciding whether to invest in the first place – Unusually high yield might suggest an undervalued share price of a possible dividend cut! Main limitations of ratio analysis • Ratios deal mainly in numbers – they don’t address issues like product quality, customer service, employee morale • Ratios largely look at the past, not the future • Ratios are most useful when they are used to compare performance over a long period or against comparable businesses and an industry – this information is not always available • Financial information can be “massaged” in several ways to make the figures used for ratios more attractive