DISPUTE RESOLUTION AND CATHARSIS: DO LAWYERS

HAVE A DUTY TO TRY TO RESTORE RELATIONSHIPS?

S. A. Benson

A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master of Laws (Dispute Resolution)

SUPERVISORS

Jonathon Rae & Cameron Holley

Faculty of Law

University of New South Wales

Sydney, Australia, 2017

DECLARATION

I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it

contains no materials previously published or written by another person, nor material which to a

substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or

any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any

contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere,

is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis.

I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to

the extent that assistance from others in the project’s design and conception or in style,

presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.

S. A. Benson

i

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank the following people for generously sharing their knowledge, technical

expertise and experience, and gracious support.

University of New South Wales:

Prof. Jonathon Rae, for his dedicated and patient supervision and valuable feedback

Prof. Rosemary Howell, for her enthusiasm for teaching the gentle art of negotiation

Gilbert & Tobin:

Allison Sadick, for her typing and format support and reality testing many of my ideas

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DECLARATION ....................................................................................................................... i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................... ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................ iii LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................. vi LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................. vii ABSTRACT............................................................................................................................ viii 1 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION................................................................................ 1 1.1 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF DISPUTE RESOLUTION............................... 1 1.2 ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION .............................................................. 2 1.3 CASE MANAGEMENT AND CIVIL LITIGATION ................................................ 5 1.4 DEFINING ‘ADR’ AND ‘MEDIATION’ ................................................................... 6 1.5 COMMON FORMS OF RELATIONAL DISPUTES ................................................. 7 1.6 A LEGAL DUTY ......................................................................................................... 8 1.7 LAWYER’S CURRENT DUTIES IN RESOLVING DISPUTES ............................... 9 1.8 LAWYERS’ DUTY TO THE COURT....................................................................... 10 1.9 OBJECTIVES............................................................................................................. 10 2 CHAPTER TWO: DISPUTE RESOLUTION.................................................................. 11 2.1 RISE OF ADR............................................................................................................ 11 2.2 BENEFITS OF ADR ................................................................................................. 13 iii

2.3 CURRENT APPROACH TO ADR IN AUSTRALIA ............................................... 14 2.4 USE OF ADR IN AUSTRALIA................................................................................. 15 2.5 ADVANTAGES OF ADR ......................................................................................... 15 2.6 CATHARSIS............................................................................................................... 16 2.7 THE IMPORTANCE OF ‘BEING HEARD’ ............................................................ 17 3 CHAPTER THREE: ADR ADVOCATES ....................................................................... 17 3.1 LAWYERS AS ADR ADVOCATES IN AUSTRALIA.............................................. 17 3.2 DUTY TO ENGAGE IN DISPUTE RESOLUTION ALTERNATIVES ................ 18 3.3 CONFLICTING DUTIES ......................................................................................... 19 4 CHAPTER FOUR: A DUTY TO MEDIATE OR RESTORE ......................................... 20 4.1 A DUTY TO TRY TO RESTORE RELATIONSHIPS IN AUSTRALIA................. 20 4.1.1 Express duty ......................................................................................................... 20 4.1.2 Implied duty ......................................................................................................... 22 4.2 A WORD OF WARNING – SOME DISPUTES SHOULD BE LITIGATED......... 23 5 CHAPTER FIVE: DISCUSSION ..................................................................................... 24 5.1 WORLDVIEW ........................................................................................................... 24 5.2 A CHANGE IN APPROACH OR ATTITUDE TO ADR ........................................ 26 5.3 THE CASE FOR A DUTY TO RESTORE ............................................................... 27 5.4 DEVELOPMENT OF THE DUTY: BASIS AND CONTENT................................ 29 5.5 CONCLUSION .......................................................................................................... 34 iv

6 CHAPTER SIX: REFERENCES ...................................................................................... 38 6.1 BIBLIOGRAPHY ...................................................................................................... 38 6.1.1 Articles/Books/Reports ....................................................................................... 38 6.1.2 Cases .................................................................................................................... 48 6.1.3 Legislation ............................................................................................................ 50 6.1.4 Delegated Legislation............................................................................................ 51 6.1.5 Other.................................................................................................................... 51 v

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1. The relationship between disputes and dispute resolution modes employed ................ 3 Figure 2. NSW District Court figures showing breakdown of civil outcomes for 2015 ............. 35 Figure 3. NSW District Court figures showing civil outcomes for years 2012-15...................... 36 Figure 4. NSW Supreme Court figures showing civil ADR outcomes for years 2011-15........... 37 vi

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ASCR

ADR

CLA

CM

CPA

DCNSW

FCA

FCR

FPA

LEADR

Med-Arb

NADRAC

SCNSW

UCPR

Australian Solicitors Conduct Rules

Alternative, Assisted or Appropriate Dispute Resolution

Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW)

Case Management

Civil Procedure Act

New South Wales District Court

Federal Court Act

Federal Court Rules

Family Provision Act

Leading Edge Alternative Dispute Resolvers

Mediation-Arbitration

National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council

New South Wales Supreme Court

Uniform Civil Procedure Rules

vii

ABSTRACT

In contentious matters, the practice of law has tended to focus on seeing a client’s ‘best interests’

as requiring them to be involved in a litigated scenario where ‘A wins; B loses.’1 There has

traditionally been less emphasis on the part of lawyers on trying to understand the underlying

causes and dynamics responsible for bringing people into conflict. Similarly, there has been little

concern to assist clients in any way other than solving the particular legal problem in which

lawyers are instructed. Lawyers have viewed such roles as the domain of the social worker or

counselor, not that of the lawyer. In this paper, I propose a new role for lawyers in which the

ground rules upon which litigation is played out nowadays have shifted and that these, in turn,

have brought about a cultural change in the worldview of lawyers with regard to their perceived

and actual duties when acting for clients beset by conflict. Alternative dispute resolution and

case management have driven this change. This cultural shift has led to lawyers being far more

involved in alternative dispute resolution, whether by compulsion or good practice, and this

uptake has brought about a revolution in how lawyers advise clients in the twenty-first century.

The ‘game theory’ of litigation is over. Case management and alternative dispute resolution,

along with changes in professional conduct rules, have cut such a swathe through how disputes

are resolved that parties and the lawyers who advise them have been forced to go back to the

strategic drawing board and consider afresh how the dispute arose, what can be done to settle it

and identify causal conduct and circumstances in order to avoid conflict in the future and restore

relationships, if possible. Lawyers’ roles have changed from a mentality of winning a court case

at all costs to assisting clients to explore where they went wrong and how they can learn from it,

and how they might empower clients to restore their relationship with their counterpart in the

instant transaction or with future parties with whom they may have to deal. Catharsis almost

always involves living through a negative experience out of which past mistakes and tensions are

in some way cauterized in the process. There are good reasons for dispute resolution to be seen

as a cathartic process and lawyers to be seen and in fact to play a central part in this process.

1

‘At the end of a trial, at the end of an appeal, the judge will be compelled to reduce a complex slice of human experience with all its

subtlety, to what is, in essence, a one line answer: "A wins; B loses."’ Keynote address by the Hon. Justice Kenneth M. Hayne at the

Judicial Conference of Australia, Melbourne, 13 November 1999, “Australian Law in the Twentieth Century”.

viii

1

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

1.1

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF DISPUTE RESOLUTION

Dispute resolution has roots in antiquity. The biblical command to ‘love another’ involves being

‘reconciled’ to one another, including one's enemies (Matthew 5:24). The Christian Gospel is one

of reconciliation (Matt 5:25, 44; 1 Corinthians 6:7). In the Old Testament, Jacob and Esau were

reconciled (Genesis 33:4) and Joseph made peace with his brothers who had sold him into

captivity after he realised that good had come from his suffering (Genesis 50:20). Nehemiah too,

whose enemies tried to oppose his wall rebuilding project in Jerusalem in the 5th century BC, was

invited to ‘confer’ with them (Nehemiah 6:1-2).2 Conversely, the overweening machinations of

humanity in Babel ended not in restoration, but scattering and inability to communicate (Genesis

11:8-9).3 The historian, Josephus, writing in the first century, regarded being able to ‘reconcile

enemies to one another’ as ‘the most excellent of our doctrines’.4 At the heart of dispute

resolution is the idea of forgiveness and reconciliation of some kind. Most ancient cultures valued

dispute resolution insofar as it restored disputing parties to one another.5 This same ethic

continues to undergird the approach to dispute resolution throughout many cultures today.6

Whereas the West became overly litigious, many Asian cultures regard litigation as a last resort.7

This thinking has slowly caught on in the common law world too. The therapeutic justice and

collaborative law movements argue that ADR should be applied in a holistic way to the

2

Albeit his opponents' intentions were sinister (Nehemiah 6:2b)

3

A picture of separation and confusion, that might be said to be the antithesis of ADR’s aims: effective communication and reconciliation.

4

Flavius Josephus, The Antiquities of the Jews, 15.136 (first published in around AD93).

5

‘There are references to dispute resolution practices by the Phoenicians, the Greeks, the Indians and the Irish’: Laurence Boulle, ‘A History

of Alternative Dispute Resolution’ (2005) 7 Alternative Dispute Resolution Bulletin 1; Bobby K Y Wong, ‘Traditional Chinese Philosophy

and Dispute Resolution’ (2000) 30 Hong Kong Law Journal 304; Bee Chen Goh, ‘Ideas of Peace and Cross-Cultural Dispute Resolution’

(2005) 17 Bond Law Review [i], 57; Justice Peter McClellan, ‘Dispute Resolution in the 21st Century; Mediate or Litigate?’ Paper given to

the National Australian Insurance Law Association, Hamilton Island, 17-19 September 2008 (Early communities tended to rely on primitive

forms of arbitration for the resolution of disputes).

6

It is not only common law jurisdictions, such as Australia, the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada where ADR has developed; a

number of civil law jurisdictions have also embraced ADR, including jurisdictions as far afield as Mexico, Italy, France, Malta and Russia:

Miryana Nesic, ‘Mediation - On the Rise in the United Kingdom’ (2001) 13 Bond Law Review [i], 2, 9; Daniel H Levine, Harmony, Law

and Anthropology (1991) 89 Michigan Law Review 1766.

7

Wong, above n 5; Goh above n 5. This phenomenon may be partly explained by the development in the West of the focus on action

stemming from Aristotle’s ‘account of action’ as the focal ‘unit of morality’ as distinct from the ancient Chinese (Confucian) view of

harmonious, aesthetic social discourse as ‘crucial’ to ‘guiding behaviour’: Laozi, Tao Te Ching on The Art of Harmony (Chad Hansen, trans,

Watkins, 2009) [first manuscript c 3rd century BC]. But the idea of ancient Chinese culture as somehow devoid of advanced strategies for war

would be a mistake: see Sun Tzu, The Art of War (Samuel B Griffith, trans, Watkins Publishing, 2005) [first manuscript c 4th century BC].

1

resolution of disputes.8 This has come to be known as the ‘harmony approach’ and is seen as a

way of handing back control of the management and resolution of disputes to the participants.9

This approach seeks to transform ADR by leveling-out any power imbalance between the

disputants so that those in the weaker position are equipped or ‘empowered’ so that their voice

may be heard.10 In this way, disputes become transformed and parties’ approach to resolution and

interaction shifts from being ‘destructive to constructive’.11 Through this process, parties

experience a change in the dynamic between them.12 ADR has a vital role as a restoration

process13 as it is an important ‘communication event’14 capable of bringing about radical change.15

1.2

ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION

Alternative dispute resolution (ADR) is ‘an umbrella term for processes’ by which disputes or

issues between disputants are resolved or managed with the assistance of a neutral party.16 ADR

is no longer ‘alternative’17 but ‘appropriate’ or ‘additional’.18 ADR is mainstream and now lies at

8

Michael S King, ‘Restorative Justice, Therapeutic Jurisprudence and the Rise of Emotionally Intelligent Justice’ (2008) 32 Melbourne

University Law Review 1096, 1123.

9

Some proponents of change envision the potential for a systemic shift from the "advocate-controlled, adversarial, formalized, rights-based,

lengthy and costly" to "client-controlled, cooperative, relational, informal, interest-based, flexible, early, expeditious and efficient": Thomas

J Stipanowich, ‘Managing Construction Conflict: Unfinished Revolution, Continuing Evolution’ (2014) 34 Construction Lawyer 13.

10

John Lande, ‘How Will Lawyering and Mediation Practices Transform Each Other?’ (1997) 24 Florida State University Law Review 839,

859; Forrest S Mosten, ‘Lawyer as Peacemaker: Building a Successful Law Practice without Ever Going to Court’ (2009) 43 Family Law

Quarterly 489, 500; Robert Mnookin and Lewis Kornhauser, 'Bargaining in the Shadow of the Law: The Case of Divorce' (1979) 88 Yale

Law Journal 950, 991; it should also be said that lawyers have played and will continue to play a vital role in this process of empowerment in

disputes where clients are, for example, in a perceived or actually weaker bargaining position than their counterpart.

11

Robert A Baruch Bush and Joseph P Folger, The Promise of Mediation: The Transformative Approach to Conflict (Jossey Bass, revised ed,

2005) 22–23 (When both [empowerment and recognition] are held central in the practice of mediation, parties are helped to transform their

conflict interaction – from destructive to constructive – and to experience the personal effects of such transformation.) cited in Thomas J

Stipanowich, ‘The International Evolution of Mediation: A Call for Dialogue and Deliberation’ (2015) 46 Victoria University of Wellington

Law Review 1191, 1193.

12

Sophia H Hall, ‘Restorative Justice: Restoring the Peace’ (2007) 21 Chicago Bar Association Record 30, 31.

13

Joshua D. Rosenberg, ‘Interpersonal Dynamics: Helping Lawyers Learn the Skills, and the Importance, of Human Relationships in the

Practice of Law’ (2004) 58 University of Miami Law Review 1225, 1249 (Participating in the process of giving and receiving feedback

provides incentives to learn as well as both new alternatives and a place to practice them).

14

ADR provides an informal, structured setting within which communication may be viewed as an ‘ongoing process’ Jonathan H Millen, ‘A

Communication Perspective for Mediation: Translating Theory into Practice’ (1984) 11 Mediation Quarterly 3; Periodicals Archive Online

275, 276.

15

As to the potential of ADR to bring about radical change in the practice of law in general, see Robert A. Baruch Bush, ‘Mediation and

Adjudication, Dispute Resolution and Ideology: An Imaginary Conversation’ (1989-1990) 3 Journal of Contemporary Legal Issues 1, 18.

16

Millen makes the point that even if a mediator, for example, is not truly neutral, ‘neutrality is the goal, even if it is not the starting point’:

Millen, above n 14, 280.

17

Justice Patricia Bergin quoted in Judge Joe Harman, ‘From Alternate to Primary Dispute Resolution: The pivotal role of mediation in (and

in avoiding) litigation’. Paper presented to the National Mediation Conference Melbourne, 2014.

18

D. Alan Rudlin, ‘Ethics: A Duty to Inform Clients about ADR?’ (1996) 11 Virginia Lawyers Weekly 342 (Alternative dispute resolution

has unquestionably evolved into much more than an "alternative" to litigation. Embraced and implemented by the courts, by corporate

counsel and increasingly by law firms, ADR has become a well established, integral part of the practice of law); Robyn Carroll, ‘Trends in

Mediation Legislation: All for One and One for All or One at All’ (2002) 30 University of Western Australia Law Review 167; see also

Dorne Boniface, Miiko Kumar and Michael Legg, Principles of Civil Procedure in New South Wales (Thompson Reuters, 2nd ed, 2012), Ch

4; Paul Coves, ‘Alternative or Mainstream? Is it time to take out the ‘A’ out of ADR?’ (2015) 20 Proctor 43.

2

the heart of the resolution of a wide range of civil disputes in society.19 ADR is the preferred way

of resolving civil disputes (see Figure 1)20. The prospect of civil cases going to trial and judgment

has receded.21

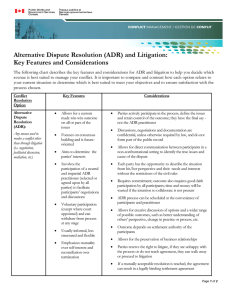

Figure 1. The relationship between disputes and dispute resolution modes employed22

ADR has not yet supplanted judicial determination in the sense that it still remains a vital adjunct

to the court system.23 ADR has, however, certainly supplemented litigation to such a degree that

the vast majority of civil disputes are resolved more by ADR nowadays than by trial and judicial

19

Susan Blake, Julie Browne and Stuart Sime, A Practical Approach to Alternative Dispute Resolution (Oxford University Press, Oxford,

2011), 204-5.

20

Blake et al, above n 19, 5 [1.13].

21

It should be remembered that negotiation in the context of pending litigation is not new and lawyers have been engaged in both for a long

time; long before ADR began. Litigation has always had a strong element of negotiation about it. ADR has ‘ratcheted-up’ the settlement rate.

Whilst parties are busy litigating, they are very often busy negotiating behind the scenes too, which is why so many cases settle out of court:

‘Settlement is the norm’: Carrie Menkel-Meadow, ‘Whose Dispute Is It Anyway: A Philosophical and Democratic Defense of Settlement (In

Some Cases)’ (1995) 83 Georgetown Law Journal 2663, 2664-5; McEwen and Wissler coined the term ‘litigotiation’ to describe this

interplay between litigation and negotiation: Craig A McEwen and Roselle L Wissler, ‘Finding out If It Is True: Comparing Mediation and

Negotiation through Research’ (2002) Journal of Dispute Resolution 131, 133.

22

Access to Justice Taskforce, A Strategic Framework for Access to Justice in the Federal Civil Justice System: Report by the Access to

Justice Taskforce (Attorney-General’s Department (Cth) 2009) available at:

<https://www.ag.gov.au/LegalSystem/Documents/A%20Strategic%20Framework%20for%20Access%20to%20Justice%20in%20the%20Fed

eral%20Civil%20Justice%20System.pdf> reproduced in Tania Sourdin, ‘Civil Dispute Resolution Obligations: What is Reasonable?’ (2012)

35 University of New South Wales Law Journal 889, 894.

23

Hall, above n 12, 31 (The adversarial process has its place and always will, but it is not necessarily the best way to approach every dispute

to obtain a lasting, satisfying and meaningful solution). Although ADR probably never will replace litigation, there is, however, a system that

has already been suggested, the 'multi-door courthouse', which, although it has not taken off in Australia, it will be argued later in this paper,

has a place such that cases may be placed into pre-filing and post-filing ADR and/or litigation tracks, where disputes are triaged even before

filing and for courts to play a role even at that early stage. Such a system would see ADR and litigation as operating hand in glove rather than

as alternatives, and are seen to be complementary and play complementary roles in the resolution of disputes. See Judith Resnik, ‘Many

Doors, Closing Doors? Alternative Dispute Resolution and Adjudication (1995) 10 Ohio State Journal on Dispute Resolution 211, 241-62.

3

determination (see Figures 2-4)24. Commentators have proffered many reasons for this positive

development. One view is that ‘early ADR proponents’ argued that courts were not ‘meeting

needs and underlying interests’ as ‘non-adversarial formats’ were, which ‘better met the interests

of the parties’, particularly area such as divorce and family law.25 The winds of change blew from

the academy, psychology, the 'therapeutic', 'transformative' or 'comprehensive' law movement,

the judiciary, the perennial mother of invention, necessity and the fact of ADR’s apparent

widespread success. The ‘quiet revolution’ of ADR26 came about largely as a result of ADR

offering more ‘holistic solutions’27 to people in dispute, and the role of lawyers, as ‘gatekeepers of

the justice system’28 has evolved as part of sweeping cultural and societal change in the way the

legal profession, the judiciary and the community began to embrace different forms of ADR.29 As

ADR has gained momentum, lawyers have had to adapt. ADR has brought about a unique and

still developing multi-dimensional30 role for lawyers in dispute resolution31 as ‘change agents’32

capable of ‘fostering communication and strengthening relational ties.’33 ADR is a ‘reaction

against the alienating and competitive style of dispute resolution fostered by the adversarial

system.’34 Rather than adopt a 'binary' approach with a 'limited remedial imagination'35 which 'may

24

Carrie Menkel-Meadow, ‘Ethics in Alternative Dispute Resolution: New Issues, No Answers from the Adversary Conception of Lawyers'

Responsibilities’ (1997) 38 Southern Texas Law Review 407, 426. One need only take a cursory glance at figures published by the NSW

District and Supreme Courts to see the low number of matters proceeding to trial and the percentage of cases settled by or discontinued after

some form of court-annexed or privately arranged ADR: see Annual Reviews of the NSW District Court and NSW Supreme Court for the

years 2014 to 2016, for example (Figure 2); Peter Cashman, ‘Civil Procedure, Politics and the Process of Reform’ in Miiko Kumar and

Michael Legg (eds), Ten Years of the Civil Procedure Act 2005 (NSW) (Thomson Reuters, 2015), 229-232.

25

Menkell-Meadow, ‘Whose Dispute?’, above n 21.

26

Stipanowich, ‘Dialogue’, above n 11, 1196-1197.

27

Evans and King, 741; based as 'holistic lawyering' is on 'spiritual growth for both client and lawyers': Mosten, 494.

28

Stipanowich, ‘Dialogue’ above n 11, 1209; Breger also helpfully observes that, as gatekeepers, lawyers have a duty to ‘spare the courts

from unnecessary litigation’ citing Jackson v. Philadelphia Housing Authority 858 F Supp. 464,472 (E.D. Pa. 1994): Marshall J. Breger,

‘Should an Attorney be Required to Advise Client of ADR Options?’ (2000) 13 Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics 427, 432-3. This

statement must be correct in light of the requirements now, in New South Wales, for example, under section 345(1) the Legal Profession Act

2004 (NSW) which provides that a lawyer is prohibited from acting in cases that lack ‘reasonable prospects of success.’

29

Carrie Menkel-Meadow, ‘Ethics in Alternative Dispute Resolution: New Issues, No Answers from the Adversary Conception of Lawyers'

Responsibilities’ (1997) 38 Southern Texas Law Review 407, 428-429, n 99.

30

Given the 'multidimensional nature of legal problems including their emotional dimensions', which require 'more comprehensive strategies

to promote their resolution': Michael King, above n 8, 1125.

31

Lehman skilfully paints a very accurate picture of the lawyer’s position, especially in the context of the anxious client, who is an ‘ordinary,

infrequent user of lawyers’ when he says: ‘The client does not know the substance of his problem or perhaps what even to expect from his

lawyer. It is in large measure up to the lawyer to define what the relation is going to be. It is his ethical responsibility’: Warren Lehman, ‘The

Pursuit of a Client’s Interests’ (1979) 77 Michigan Law Review 1078, 1084.

32

Perlin calls lawyers potential ‘healing agents’: Michael L Perlin, ‘A Law of Healing’ (2000) 68 University of Cincinnati Law Review 407-8.

In ADR and relationship restoration, people in disputes very often need help; people ‘do not have to tackle issues in their own…it is

impossible for us to do so…if we tackle them with others we will find the wisdom and the strength to do so. Alone they will prove too much;

together they are manageable…’ Robert Banks, All the Business of Life (Albatross, 1987), 92. Lawyers must start to see themselves as

serving others in this important area.

33

Stipanowich, ‘Dialogue’ above n 11, 1209-1210.

34

Margaret Thornton, ‘Mediation Policy and the State’ (1993) 4 Australian Dispute Resolution Journal 230, 235 cited in Laurence Boulle,

Mediation: Principles, Process and Practice (LexisNexis, 2011), 60.

35

Carrie Menkel-Meadow, ‘The Trouble with the Adversary System in a Postmodern, Multicultural World’ (1996) 38 William & Mary Law

Review 5, 7.

4

thwart essential goals'36 of the adversarial system, lawyers must uphold ADR’s vision37 as it

provides a ‘highly unique context for the resolution of conflict.’38

1.3

CASE MANAGEMENT AND CIVIL LITIGATION

Much has changed in the court system in the last 30 years. The way civil litigation is managed is

in response to greater awareness of increasingly scarce judicial resources. There are also different

discretionary factors at play when it comes to courts granting or refusing relief than there were 20

years ago. The ‘overriding’ or ‘overarching’ purpose of ensuring the ‘just, quick and cheap’

conduct and disposal of civil litigation, and compliance with, procedural rules, is a paramount

discretionary factor, which was almost foreign to courts before the 1990s.39 As a result of reports

into civil justice, particularly in the United Kingdom by Lord Woolf,40 law reform was influenced

in a number of jurisdictions, including Australia, leading to the widespread adoption of case

management.41 Case management has been the order of the day for the last 20 years in a number

of jurisdictions. ADR is case management’s beating heart. The need to reign in burgeoning court

lists had become critical. Case management has successfully cleared civil litigation backlogs.42

Case management owes its success to the increased use of mandated ADR and judicial alacrity

for making orders adverse to any party or lawyer who seeks to subvert its principal objectives.43

Legislative change has also contributed to reduced rates of civil litigation in Australia and

elsewhere.44 Civil case management in Australian and United Kingdom underpinned by ADR

(mediation; informal settlement conferences) has led to most civil cases settling before trial.45

36

Menkel-Meadow, The Trouble’, above n 35, 5.

37

Boulle, Mediation, above n 34, 293.

38

Millen, above n 14, 281.

39

A key objective of the case management reforms in Australia and enshrined in section 56(1) of the Civil Procedure Act 2005 (NSW) and

other State and Territory (and federal) equivalents.

40

H Woolf, Access to Justice, Interim Report to the Lord Chancellor on the Civil Justice System in England and Wales (1995); Access to

Justice, Final Report to the Lord Chancellor on the Civil Justice System in England and Wales (1996).

41

Ronald Sackville, 'Civil Justice Reform: The Third Phase' in Miiko Kumar and Michael Legg (eds), Ten Years of the Civil Procedure Act

2005 (NSW) (Thomson Reuters, 2015), 213.

42

Baruch Bush, Robert A, ‘Mediation and Adjudication, Dispute Resolution and Ideology: An Imaginary Conversation’ (1989-1990) 3

Journal of Contemporary Legal Issues 1, 2; Richard Birke, ‘Evaluation and Facilitation: Moving Past Either/Or’ (2000) Journal of Dispute

Resolution 309, 311; Stipanowich, above n 9, 11.

43

The figures speak for themselves: see Figures 2-4 below. With regard to the effect of the civil justice reforms in England and Wales, see

also Cashman, above n 23, 232; see State of Queensland v J L Holdings Pty Ltd (1997) 189 CLR 146; Aon Risk Services Australia Limited v

Australian National University [2009] HCA 27; 239 CLR 175 and Expense Reduction Analysts Group Pty Ltd v Armstrong Strategic

Management and Marketing Pty Limited [2013] HCA 46. 88 ALJR 76.

44

An example of this is the Civil Procedure Act 2002 (NSW), which brought about a sharp fall in civil filings, particularly in the NSW

District Court, which is reputedly the busiest civil trial court in Australia. The statistics published by the NSW Supreme Court and District

Court evidence this trend: see the statistics at Figures 2-4 below. These figures show that civil litigation filings spiked just before the Civil

Procedure Act came into force. There has been a consistent stark reduction in civil filings in both courts since. In the United Kingdom, the

5

The evidence of ADR's success in civil dispute resolution is unassailable. In New South Wales,

figures published by the District and Supreme Courts show that the proportion of cases resolved

by ADR vastly outweighed those that went to trial between 2014 and 2016.46 Part of ADR's

success has been a healthy judicial proclivity to 'fine' even a successful party for snubbing courtannexed ADR opportunities. Capolingua v Phylum Pty Ltd and Dunnett v Railtrack plc stand out as

landmark Australian and English authority, respectively, on point.47

Along with the changes to civil litigation, which case management and ADR have brought about,

there has been a line of authority in three important areas consistent with this new civil justice

regime. The categories of cases may be described as policy, costs and ADR enforcement

decisions.48 A sample of the authorities reflects growing corporate dissatisfaction by the courts

with lawyers and parties who are reluctant or unprepared to engage in ADR in good faith or at

all, and who regard litigation and the court process as a sort of ‘card game.’49 In summary, this

new environment that lawyers find themselves in, where the emphasis is on the resolution of

disputes by ADR, rather than fully contested judicial adjudication, raises questions about the

precise role and duties of a lawyer in this ever changing legal landscape. Community expectations

of lawyers’ roles and duties have changed too, as have those of the judiciary and lawyers’

professional bodies, cast in the dual role of promulgator of conduct standards and trade union.

Given ADR’s pre-eminence, it is time to consider whether lawyers have a duty to try to restore

relationships, where possible, and, if so, how such a duty may be said to arise and what it entails.50

1.4

DEFINING ‘ADR’ AND ‘MEDIATION’

There is a need to address some definitions before proceeding further. 'ADR' means processes by

which disputes are dealt with other than by judicial determination, such as mediation, arbitration,

drop in the number of cases filed in the Chancery and Queens Bench divisions of the High Court after the Woolf reforms were implemented

was even more stark (although the author notes that debt claims and enforcement were transferred to the County Court, the drastic reduction

in cases filed does coincide with the procedural reforms and the increased emphasis on ADR to achieve case management ends and legal

costs savings): Cashman, above n 23, 232.

45

See Cashman, above n 23, 232.

46

New South Wales District Court Annual Review 2016; New South Wales Supreme Court Annual Review for 2015.

47

(1991) 5 WAR 137; [2002] 2 All ER 850; it is important to bear in mind that the conduct complained of and judicially condemned in

Capolingua went beyond an ‘obstructive and uncooperative attitude’ at the mediation, which the Trial Judge said was ‘rendered nugatory by

the conduct’ (Ipp J, 6); the defendants, who succeeded at trial, were deprived of their costs as their conduct with regard to mediation was part

of a course of conduct designed to frustrate the ADR initiatives of the Expedition List for the speedy determination of disputes (per Ipp J, 4).

48

These authorities are dealt with throughout: see n

49

An approach eschewed in the strongest possible terms by the New South Wales Court of Appeal, especially vociferously by Heydon JA, as

he was then, in Nolan v Marson Transport (2001) 53 NSWLR 116; [2001] NSWCA 346.

50

In the sense of an actual duty, all things considered, as distinct from one ‘on first appearance’, other things being equal: Stephen Charles

Mott, Biblical Ethics and Social Change (Oxford University Press, 1982), 154-60; John Jefferson Davis, Evangelical Ethics (P&R

Publishing, 1985), 6.

6

conciliation and facilitation. NADRAC has a useful glossary of good working definitions for each

of these terms.51 'Mediation' where used throughout refers to a form of without prejudice,

facilitated negotiation where the mediator is the negotiation facilitator.52 Section 25 of the Civil

Procedure Act 2005 (NSW) provides that mediation is ‘a structured negotiation process in which

the mediator, as a neutral and independent party, assists the parties to a dispute to achieve their

own resolution of the dispute.’ The NADRAC definition is: 'Mediation is a process in which

participants to a dispute, with the assistance of a dispute resolution practitioner (a mediator),

identify the disputed issues, develop options, consider alternatives and endeavour to reach an

agreement.'53 A mediator has 'no advisory or determinative role'54 except where mediation takes a

more evaluative or expert form.55 Where reference is made to ‘restoration of relationships' or

'restoring relationships', this means, at a minimum, enabling or empowering parties to the instant

dispute as well as potential future disputes to live normal commercial or personal lives where they

have the capacity to engage on a normal footing with the other party or with future parties in a

non-combative, non-adversarial and co-operative manner.56 Finally, LEADR defines mediation as

‘a process in which the participants, with the support of a mediator, identify issues, develop

options, consider alternatives and make decisions about future actions and outcomes. The

mediator acts as a third party to support participants to reach their own decision.’57 These

definitions of mediation all emphasise process, party participation and the mediator’s neutrality.58

1.5

COMMON FORMS OF RELATIONAL DISPUTES

The three main areas where people find themselves in dispute are personal, vocational, and

commercial.59 Not all disputes involve parties who are in any relationship in the foregoing

51

The NADRAC Glossary of ADR Terms is available at

https://www.ag.gov.au/LegalSystem/AlternateDisputeResolution/Documents/NADRAC%20Publications/Dispute%20Resolution%20Terms.

PDF (last accessed 3 November 2017).

52

Brown v Rice [2007] EWHC 625 (Ch) 625 [13], [21] and Chris Guthrie, ‘The Lawyer's Philosophical Map and the Disputant's Perceptual

Map: Impediments to Facilitate Mediation and Lawyering’ (2001) 6 Harvard Negotiation Law Review 145.

53

NADRAC Glossary of ADR Terms.

54

In this regard, the NADRAC definition agrees with section 25 of the Civil Procedure Act 2005 (NSW).

55

Where, according to the NADRAC definitions of each of these forms, some kind of evaluative or industry or technical expertise is

regarded as an appropriate mediation mode for dealing with the unique issues peculiar to some disputes.

56

'A more complete and satisfactory resolution of the dispute is possible by restoring relationships through the collaborative process of

restorative justice': Hall, above n 12, 31.

57

The Australian National Mediator Standards: Approval Standards September 2007 reproduced in LEADR Mediation Workshop Materials,

Sydney, 28 April-2 May 2014.

58

William L F Felstiner, Richard L Abel and Austin Sarat, ‘The Emergence and Transformation of Disputes: Naming, Blaming, Claiming…’

(1980 - 1981) 15 Law & Society Review 631, 632 (studying the emergence and transformation of disputes means studying a social process).

59

Dwight Gollan, ‘Is Legal Mediation a Process of Repair or Separation – An Empirical Study and Its Implications’ (2002) 7 Harvard

Negotiation Law Review 301, 308 (‘marital, commercial and organisational’ relationships are the usual categories of relationship that end in

disputes).

7

categories. For example, the parties to a patent infringement dispute will invariably be unrelated

parties who may or may not be known to one another in a particular field or market. In the

context of disputes between unrelated parties, lawyers have no duty to ‘restore any relationship’

as there is no relationship to restore.60 There may though still be lessons to learn. In other

contexts, where parties have had a longstanding relationship and/or they are likely to have an

ongoing relationship irrespective of the outcome of the dispute, for example, in a family,

workplace or contractual setting, it is submitted that lawyers do have a duty to try to restore such

relationships as part and parcel of resolving or least managing the dispute. It is a narrow view of a

client’s ‘best interests’ to say that a client’s legal problem is the sole cause of a dispute and the

only impediment to resolution. There is a ‘back story’ lurking behind the most common disputes,

to which only the parties are privy. Often, hotly contested disputes seem trivial to outsiders, such

as lawyers. What someone perceives as a dispute is a dispute even if others do not understand it.61

A dispute is something ‘felt’.62 People reach a tipping point63 where the dispute ‘escalates’ into a

strongly perceived need to do something about it.64 Empathy matters then in all ADR contexts.65

1.6

A LEGAL DUTY

Legal duties of lawyers usually refer to what lawyers ‘should do’ or ‘ought to do’.66 A duty may be

moral,67 ethical,68 or contractual, arising by virtue of the lawyer/client retainer.69 The duty on

lawyers to endeavour to restore relationships where their clients are in dispute is something that

60

As Golann has argued, ‘repair assumes rupture’: Gollan, above n 60, 307-308.

61

Just as anything that is perceived as noise, is noise; it matters not that others do not or cannot also ‘hear’ it. It is the same with pain.

62

Felstiner et al, above n 58, 633 (a dispute is a perceived injurious experience or ‘PIE’); Bernard Mayer, The Dynamics of Conflict (JosseyBass, 2nd ed, 2012), 5 (conflict is something people feel on an emotional level).

63

Often due to underlying unresolved conflict.

64

Mayer, above n 62, 19-24.

65

Craig Smith, ‘Applying findings from neuroscience to inform and enhance mediator skills’ (2015) Australian Dispute Resolution Journal

249, 257-8 (developing an environment of trust can enable a neural shift for people towards approach patterns).

66

A legal obligation owed by one person to another, which may require the performance of, or refraining from, certain actions: P. Nygh and

P. Butt (eds), Butterworths Australian Legal Dictionary (Sydney: Butterworths, 1997), 396.

67

Moral ought-ness is difficult to discern in a relativistic post-modern world; relativistic in the sense that the concept of objective truth is

contested and post-modern discourse discloses a rejection of the idea of language being capable of describing reality to embracing the idea

that language creates reality. All thought is perspectival, interpretive and provisional. ‘Post modern philosophy … includes … an anti (or

post) epistemological standpoint; anti-essentialism; antirealism; anti-foundationalism; opposition to transcendental arguments and

transcendental standpoints; rejection of the picture of knowledge as accurate representation; rejection of truth as correspondence to

reality…’: Bernd Magnus “postmodern” in Robert Audi (ed) The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy (Cambridge University Press, 2nd

ed, 1999), 275-7 (emphasis added). How the acolytes of post-modernism advance their ideas, if truth is elusive, is a logical conundrum for

them and others to try to explain.

68

That is, practical rules. If the term ‘morals’ describes how humans act, then ‘ethics’ is the evaluation of morals: Andrew J B Cameron,

Joined-up Life (Inter-Varsity, 2011), 19. On this analysis, morality is descriptive, while ethics is proscriptive. Ethics helps us to understand

morality. Morality provides the map whereas ethics is the compass guiding and giving us a sense of ethical ‘ought-ness’.

69

‘The contract between legal practitioner and client for the provision of legal services’: Nygh and Butt, Butterworths Australian Legal

Dictionary, above n 65, 1024.

8

lawyers ‘ought to do’, where possible. If it is not an ethical duty (imposed by professional

conduct rules or in equity),70 it may be implied into a lawyer’s retainer in contentious matters.71

Making the case for such a duty involves a consideration of the lawyers’ existing obligations.

Stipanowich argues that seeing lawyers as only engaged in ‘back and forth distributive bargaining’

after parties ‘lawyer up’ is a tired approach.72 This model is a relic from another age when

litigation was still in the hands of lawyers and their clients. Negotiation in the context of disputes

is a ‘dance’ now, requiring familiarity with ADR alternatives.73 Lawyers ought not contribute to

‘mediation dysfunction’ mediation’s success is too important.74 It is time for relational restoration

to be seen as part of clients’ best interests. ADR has a unique potential to improve relationships.

1.7

LAWYER’S CURRENT DUTIES IN RESOLVING DISPUTES

There is an explicit duty on lawyers to make clients aware of alternatives to a fully contested

adjudication of disputes where, in the lawyer’s judgment, such alternatives are reasonably

available.75 Short of explicit duties, rules of court, contractual terms and the trend of authority

have created an environment in which lawyers have an implied duty with regard to trying to

resolve disputes.76 This duty arises in a number of ways. Firstly, there are costs consequences for

not engaging in ADR, not engaging in ADR in good faith, delay in participation or ‘pulling out.’77

An adverse costs order is usually made against a party to the litigation, but courts also have wide

70

As the relationship between lawyer and client is a fiduciary one: Nocton v Lord Ashburton [1919] AC 492; Phipps v Boardman [1967] 2

AC 46; [1966] 3 All ER 721; Clark Boyce v Mouat [1994] 1 AC 428; [1994] 4 All ER 268; Maguire v Makaronis (1997) 188 CLR 449.

71

Arising from a broad view of ‘best interests’ of the client, what may almost be called the duty to mediate even before the dispute escalates

into litigation (the reality is that most judges now will ask the parties at the first directions hearing why they have not been to mediation and

will send them anyway), the fiduciary nature of the lawyer/client relationship, a duty of care, an ‘ethic of care’ too in some situations driven

by demand for more of a voice in the process: as to ‘ethic of care’ and ‘demand for a voice’ see Susan Daicoff, ‘Lawyer, be Thyself: An

Empirical Investigation of the Relationship between the Ethic of Care, the Feeling Decision-Making Preference, and Lawyer Well-Being’

(2008) 16 Virginia Journal of Social Policy and the Law 87.

72

Stipanowich, ‘Dialogue’ above n 11, 1191.

73

Stipanowich, ‘Dialogue’ above n 11, 1210-1211; the American Bar Association first published a major study on ‘the skill of counselling a

client about litigation and alternative processes in other dispute resolution forums together with the ability to take part (sic) in them’: Archie

Zariski, ‘Lawyers and Dispute Resolution: What Do They Think And Know (And Think They Know)? Finding Out Through Survey

Research’ [1997] Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law 18, [4]. <http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/MurUEJL/1997/18.html>

74

Stipanowich, above n 11, 1211.

75

ACSR rule 7.2.

76

This argument will be developed further below where the implied term issue is said to support an existing duty on lawyers to try to restore

relationships, where possible.

77

The High Court is yet to define ‘good faith’ but there a number of authorities usefully gathered together by Tania Sourdin, "Good Faith,

Bad Faith? Making an Effort in Dispute Resolution" (2012) Good Faith Paper 1; see also Aiton Australia Pty Ltd v Transfield Pty Ltd [1999]

NSWSC 996. Boulle points to other authorities showing what he calls a ‘relatively benign judicial attitude’ towards lawyer conduct in a

mediation setting, but two of the four cases he cites were judgments of inferior courts of record (District Court of Queensland and Northern

Territory) and the other two, from 2002 (WA Supreme Court and Queens Bench), would not be persuasive now given that the prevailing

judicial attitude in Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States eschews a lawyer and a party failing to attend mediation or to attend

in good faith very seriously. These decisions are now out of step with later authority; see for example Dunnett v Railtrack plc [2002] 2 All

ER 850 and People’s Mortgage Corporation v Kan Bankers Surety Co 62 F App’x 232 (10th Cir 2003), respectively. For an extensive

review of the authorities and the situations in which courts have in effect fined a defaulting party with regard to their conduct concerning

participation in court-annexed ADR, see Blake et al, above n 19, Ch 8.

9

powers to make a personal order for costs against a third party, including lawyers.78 Secondly,

courts now expect litigants to have attempted ADR or their lawyers to inform the court of the

suitability of the dispute to ADR and the prospects of resolution using ADR. Thirdly, most

courts have rules requiring proceedings to be referred to ADR as a precondition to obtaining a

hearing date.79 Lawyers now routinely expect disputes to be mediated during the proceedings. In

most cases, mediation has been tried once before proceedings were filed.80 Many cases that do

not settle during mediation eventually settle as issues have been narrowed. This may explain why

courts take a justifiably adverse view of parties who do not take part, or subvert or pull out of it.81

1.8

LAWYERS’ DUTY TO THE COURT

In the common law system, lawyers have a paramount duty to the court and the administration

of justice. This duty is enshrined in lawyers’ conduct rules.82 Case management is an integral part

of the court system and underpinning case management is ADR. As officers of the court then,

lawyers have an inescapable duty to further and advance the interests of justice, an integral aim of

which for at least the last 30 years has been the non-judicial resolution of disputes (that is, dispute

resolution without the need for a trial and a court imposed judgment).

1.9

OBJECTIVES

This paper will examine this issue of lawyers' duty in the context of mediation in Australia,83 with

some analysis from elsewhere, and only where a lawyer is retained to act for a party to a dispute.

The duty on a lawyer acting as an ADR practitioner, that is, as a mediator, for example, will not

be the concern of this paper. Whilst lawyers acting as ADR practitioners are also subject to the

same professional duties as other lawyers, they are also subject to different ethical and

professional standards regimes and legislation, which are beyond the scope of this paper.

78

For example, section 99 of the Civil Procedure Act 2005 (NSW).

79

ADR serves the overriding purpose of case management. ADR referral is mandated in most courts. See Parts 4 and 5 of the Civil

Procedure Act 2005 (NSW); Part 20 of the Uniform Civil Procedure Rules; New South Wales Supreme Court Practice Note SC Gen 6;

court-annexed mediation has been ‘an integral part of the Court’s adjudicative processes’ since 2000: James Spigelman, ‘Mediation and the

Court’ (2001) 39 (2) Law Society Journal 63.

80

Campbell Bridge, ‘Comparative ADR In The Asia-Pacific – Developments in Mediation in Australia’. Paper presented at the 5Cs of ADR

Alternative Dispute Resolution Conference, Singapore, 4-5 October 2012 quoted in Harman, above n 17, 9.

81

Dunnett v Railtrack plc [2002] 2 All ER 850 is the prime example. The ADR session rejected was after trial but before appeal; Railtrack

succeeded on appeal, albeit on a technicality, but was deprived of its costs of the appeal for failing to participate in ADR. Other authorities

making good this proposition are referred to below.

82

83

ASCR rule 3.1.

Given that it is the main form of ADR, especially in the Australian State and Territory District and Supreme Courts.

10

2

CHAPTER TWO: DISPUTE RESOLUTION

2.1

RISE OF ADR

ADR’s roots lie in the well-tilled soils of ‘community and neighbourhood mediation schemes’

and family law conciliation initiatives in the United States in the 1970s.84 Lawyers can take no

credit for initiating it. ADR was not something lawyers taught, but caught.85 The main rationale

for ADR lay in the inability of the judicial system to deal with non-legal needs and issues.

Another rationale for ADR was harm people sustained which was caused by litigation.86 In ‘The

Litigant-Patient: Mental Health Consequences of Civil Litigation,’ Larry H. Strasburger addresses

the psychological consequences of litigation and refers to the term coined by Gutheil, 'critogenic

harm'.87 This term refers to the emotional harm resulting from the litigation process.88 The

‘trauma’ that their litigation clients experience throughout and after court cases is a topic that

most litigation lawyers would prefer to avoid. This is, then, an important area to get right and one

calling for an increased awareness by lawyers89 to ‘turn their thinking to being conciliators.’90

Like any other multidisciplinary professional practice, lawyers will increasingly need to use other

professionals, such as mental health practitioners, in order to get their clients through and survive

the process. There is little point in lawyers telling their clients that they will be ‘empowered’ by

litigation if all litigation is really doing is traumatizing them.91 As Strasburger rightly points out,

the legal process can be empowering and enable an individual to stand up for her or himself, and

hold those who have wronged them responsible.92 These are laudable aspects of the court system.

84

Specifically, juvenile justice. Cyril Glasser and Simon Roberts, ‘Dispute Resolution: Civil Justice and Its Alternatives’ (1993) 56 Modern

Law Review 277, 277-278; the same community trend may be seen in the mediation referral provisions of the Community Justice Centre Act

1983 (NSW); see also Nadia Alexander, ‘Global Trends in Mediation: Riding the Third Wave’ in Nadia Alexander (ed) Global Trends in

Mediation (2nd ed, 2006), Ch 1.

85

‘Lawyers did not generally take a leading part in these initiatives’: Glasser & Roberts, above n 85, 277-278.

86

Edward J. Hickling, Edward B. Blanchard & Matthew T. Hickling, ‘The Psychological Impact of Litigation: Compensation Neurosis,

Malingering, PTSD, Secondary Traumatization, and Other Lessons from MVAS’ (2006) 55 De Paul Law Review 617 (harm generally stems

from the individuality of litigants being stripped away with litigation’s rights focus); this is the thrust of Strasburger’s article, below n 87.

87

Larry H. Strasburger, ‘The Litigant-Patient: Mental Health Consequences of Civil Litigation,’ (1999) 27 Journal of American Academy of

Psychiatry Law 203.

88

Strasburger, above n 88, 206. See also Nsisong Anthony Udoh and Kudirat Bimbo Sanni, ‘Supplanting the venom of litigation with

alternative dispute resolution: the role of counsellors and guidance professionals’ (2015) 43 British Journal of Guidance & Counselling 518.

89

It is something that may help lawyers turn from what Menkel-Meadow calls the ‘culture of adversarialism’: Carrie Menkel-Meadow, ‘The

Lawyer as Problem Solver and Third-Party Neutral: Creativity and Non-partisanship in Lawyering’ (1999) 72 Temple Law Review 785, 788.

90

William R Ide III, ‘Summoning Our Resolve - Alternative Dispute Resolution Aims for Settlement without Litigation’ (1993) 79 American

Bar Association Journal 8.

91

Strasburger, above n 87, 205-7.

92

Strasburger, above n 87, 206.

11

But money, in the form of damages, is not always the ‘poultice’ that it is cracked-up to be.93

Damages can only ever achieve so much.94 This is not a failing of the common law system itself.

but recognition, as Sackville has argued over access to justice, that courts can only do so much.95

In a personal injuries context, for example, there is no getting around the fact that almost

invariably proceedings need to be filed in order to protect limitation periods. Strasburger points

out that this often results in a personal injuries litigant having to come to terms very quickly with

the fact that they are now a plaintiff in a civil lawsuit, which is often not only something beyond

which they could ever have imagined seeing themselves being, but they also need to come to

terms with the public nature of litigation and the lack of control over the boundaries and privacy

which most people accept as a given.96 Although Strasburger was writing in 1999, and was

justifiably doubtful that litigation rates would ever decrease, many of the issues Strasburger raises,

particularly about litigation as a process, are as relevant to fully contested litigation now as they

are to the ADR context as well97. ADR, with or without related litigation on foot, is just as much

a process.98 Most ADR practitioners will have protocols that will, quite properly, require the

exchange of information such as outlines of facts, chronologies and position statements.99 Most

ADR practitioners also require separate preliminary meetings with each disputant and their legal

team. Much needs to be done and much is required of people who are in dispute, even before

mediation, for example, gets underway. It is just as much a process for someone unused to this

kind of formal dispute resolution setting. Many of the comments Strasburger makes with regard

to litigation stress apply to ADR. Although almost all ADR is private, there is still the perceived

risk, despite confidentiality, non-disclosure and privilege obligations, of personal information

being disclosed and subjected to scrutiny.100

93

Strasburger, above n 87, 205.

94

As Goldman rightly says, there is a need 'to be cognizant of non-monetary considerations that might be important to the plaintiff, like an

apology from the laughing employee': William Goldman, 'The Lawyer's Philosophical Map' (2001) 6 Harvard Negotiation Law Review 145,

175. See also Tamara Relis, 'It's Not about the Money: A Theory of Misconceptions of Plaintiffs' Litigation Aims' (2007) 68 University of

Pittsburgh Law Review701: it may be something as simple as 'plaintiffs' desires to obtain acknowledgment of error': 701.

95

Sackville, above n 41, 209-223.

96

Strasburger, above n 87, 207.

97

Strasburger, above n 87, 210 (the ever increasing frequency of lawsuits has no end in sight).

98

The editors of Butterworths Australian Legal Dictionary agree that ADR is a ‘process’ but their description of it as a ‘decision making’

one ‘outside the usual court-based litigation model’, is not one I agree with: ‘ADR The decision making process by which matters are

resolved outside the usual court-based litigation model’: Nygh and Butt, Butterworths Australian Legal Dictionary, above n 65, 50. It may

not necessarily be a ‘decision making process’ and very often ADR takes place in the context of the ‘usual court-based litigation’ (case

management) framework, to which it is integral.

99

Boulle, Mediation, above n 33, 229-231.

100

Strasburger, above n 87, 207.

12

Strasburger makes an excellent point about ‘reality-testing’ whether the position held by a

disputant with regard to these matters is legitimate or groundless.101 Lawyers can help their clients

with this either by giving them advice on likely outcomes or referring their clients to a psychiatrist

or psychologist to reinforce the message that although anxiety is a natural response to dispute

resolution, the client will benefit from this process, even if a resolution is or cannot achieved.102

One crucial part of being a lawyer is to put clients in a crisis at ease.103

2.2

BENEFITS OF ADR

The main benefits of ADR are speed, low cost and a non-binary, private outcome.104 There is no

doubt that the commencement of legal proceedings has a deleterious effect on relationships.105

Conversely, ADR ‘takes the heat’ out of disputes before costs, emotions and positional posturing

get out of hand, and past the point of no return. When a dispute is referred to ADR, even if

underlying proceedings have been commenced, the dispute may not have escalated to a point

where the compulsive powers of the state need to be invoked and a third party adjudicator

allocated to hear evidence and submissions and determine the factual and legal issues between

them. ADR involves more wide-ranging exploration of underlying causes of a particular dispute.

ADR, therefore, encompasses legal and non-legal issues between the parties and can address nonlegal issues in a way that a judicial determination cannot.106 Because non-legal issues can be aired

as people feel heard, feelings having been expressed and narrative having been listened to, it is

possible for parties to ‘drill-down’ deeper into the pathology of their dispute.107 ADR leads to a

101

Strasburger, above n 87, 209.

102

Strasburger, above n 87, 209.

103

Michael King, above n 8, 1118 ('Therapeutic jurisprudence and restorative justice suggest that, in particular contexts of legal problemsolving, processes that take into account the problem's emotional dimensions and that involve professionals exercising skills in perceiving,

understanding and handling their own and the parties' emotions are important in promoting the problem's comprehensive resolution').

104

That is, not imposed nor in any sense is the dispute or the parties’ role in the events giving rise to them somehow ‘judged’.

105

Gollan, above n 60, 325-6 (citing a mediator’s response that litigation made repairing a ruptured relationship like ‘reattaching a limb’ and

a Boston study which found that where proceedings were commenced, the disputants were not interested in a repaired relationship: Marc

Galanter, ‘Reading the Landscape of Disputes: What We Know and Don’t Know (and Think We Know) About Our Allegedly Contentious

and Litigious Society’ (1983) 31 University of California Los Angeles Law Review 2).

106

It has been said that it is this focus on ‘emotional intelligence’ that is lacking in the court system: King, Michael, Freiberg, Arie and

Reinhardt, Greg, ‘Introduction’ (2011) 37 Monash University Law Review 1, 5.

107

‘…without narration there is no rational explanation of the past…’: John Patrick Diggins in Gordon S. Wood, The Purpose of the Past

(Penguin, 2008), 59. This is not to suggest that storytelling is merely ‘utilitarian’ in the sense that just because ‘uncovering underlying

patterns in history and human behaviour …might help in understanding the past and managing the future, or even the present’: Barbara W.

Tuchman, The March of Folly: From Troy to Vietnam (Knopf, 1984) cited in Wood, The Purpose of the Past, 63. When people are allowed

to tell their stories, it is cathartic and therapeutic, and, therefore, beneficial. There is a lot to people having the ‘freedom’ and the safety in

which to ‘say their piece’: King, ‘Justice and Harmony’, 95-96. As to whether such a narrative, conciliatory approach is utilitarian, see

Warren Lehman, ‘The Pursuit of a Client’s Interests’ (1979) 77 Michigan Law Review 1078, 1084.

13

deeper understanding of the causes of conflict and empowers the parties to take a far more

proactive role in the management and resolution of their dispute.108

Because of the way ADR and litigation seek to achieve the same objective are completely

different, parties who have been through an ADR process often feel that their voice has been

heard much more so than litigation, where lawyers translate the dispute into the evidence and the

issues that are only 'relevant', and into legal categories and relief which bear little or no relation to

the underlying and usually sidelined non-legal problems exercising the minds of the disputants.109

2.3

CURRENT APPROACH TO ADR IN AUSTRALIA

The current approach to ADR in Australia is a mix of court-annexed and private facilitation.110

Private ADR occurs where parties to a dispute share the cost of an independent facilitator to help

them identify issues, exchange positions and help the parties come to an accommodation. The

aim here is to reach a compromise without adjudicating on the merits of the dispute.111 It is

possible for private mediation to occur regardless of whether there is pending litigation. At times

the two work well together as the risk of a looming hearing date tends to focus the parties' minds.

This approach takes place both within and outside of the legal system and does not always

involve lawyers. The most common forms of ADR in Australia are mediation, facilitation,

arbitration, med-arb (so-called 'hybrid' or combined approaches) as well as forms of neutral

evaluation, non-binding evaluation and informal settlement conference.112 Of these, mediation is

the most common form of ADR in Australia and is used before litigation has commenced, where

litigation has been threatened as well as after proceedings have been commenced. Mediation is

often used pursuant to court and tribunal rules.113 In most Australian jurisdictions, the courts

(backed up by overwhelming judicial support) mandate referral to mediation, even where parties

108

Menkel-Meadow, above n 21, 2691.

109

It was Judge Learned Hand who said that it was a rare litigant who recognised their dispute in court; he also said that, ‘As a litigant, I

should dread a lawsuit beyond almost anything else short of sickness and death.’ In an observation in ‘Lawyer, Know Thyself: A Review of

Empirical Research on Attorney Attributes Bearing on Professionalism’ (1997) 46 American University Law Review 1337, Susan Daicoff

observed that lawyers' rational, unemotional personalities ‘might explain why lawyers and their clients at times have trouble interacting with

and relating to each other.’ How often clients must leave lawyer's offices and court rooms feeling like their lawyer did not listen and as

though the lawyer regarded all of the non-legal issues (what might be called 'heart issues') standing in the way of resolution as irrelevant

distractions.

110

Michael King, Arie Freiberg, Becky Batagol and Ross Hyams, Non-Adversarial Justice (Federation, 2014), 112.

111

King et al, above n 110, 112 (The role of the facilitative mediator is limited to process intervention).

112

The informal settlement conference has been particularly successful in the New South Wales Supreme Court, Equity Division in

Succession Act 2006 (NSW) [formerly the Family Provision Act 1982 (NSW)] claims with regard to contested deceased estates where the net

distributable estate is less than $500,000.00 which ‘reduced the number of cases going to the court-annexed mediation program’: see New

South Wales Supreme Court Annual Review 2015, 32, 54 (n 3).

113

So-called 'court-annexed' mediation: most Australian courts and tribunals have court-annexed ADR and mediation is the most common.

14

do not wish to mediate so that some kind of consensus might result.114 Leaving esoteric

objections aside, whatever may be said of compulsion, it works.115 Consensus often eventuates.116

2.4

USE OF ADR IN AUSTRALIA

It is difficult to say whether outcomes reached in ADR are better than a fully adjudicated one as

it depends on the nature of the dispute. For example, there is a public interest in test case

litigation and where members of a large class of people have suffered injury. In these situations,

there is a wider benefit from the public nature of a court judgment, where rights may be

vindicated and wrongdoers (such as tortfeasors) punished, compared to the private and

confidential nature of ADR, where public vindication and the precedential value of a judgment

are not possible.117 In general though, ADR encompasses legal and non-legal issues and it can,

therefore, address and resolve the non-legal aspects of a dispute more satisfactorily than courts.118

Industry specific mediation has also been a success with the major banks, the Australian Tax

Office and a number of Ombudsman schemes assisting their clients with ongoing

relationships.119

2.5

ADVANTAGES OF ADR

ADR is fraction of the cost of litigation, it saves time and it saves people the stress of preparation

and uncertainty of litigation. The cost of representation at a mediation session may be the only

114

Hooper Baillie Associated Ltd v Natcon Group Pty Ltd (1992) 28 NSWLR 194 at [206] per Giles J.

115

A number of commentators, led by Owen Fiss, criticise ADR for 'pressuring' parties into settling their cases, question ADR's underlying

assumptions, argue that ADR is just a way for courts to clear their dockets as poorer litigants are forced to accept a settlement as litigants

with deeper pockets can impose expenses on them, such as discovery: Owen M Fiss, ‘Against Settlement’ (1984) 93 Yale Law Journal 10731075. Fiss sees ADR as 'capitulation to the conditions of mass society and should be neither encouraged nor praised.' (1075); his point that

important cases concerning issues of wider social importance settling because of economic inequality in society has some force, but a

settlement on terms parties can live with - both parties - is far better than the uncertainty of a trial and judgment, and appeals: John Lande,

‘Using Dispute System Design Methods to Promote Good-Faith Participation in Court-Connected Mediation Programs’ (2002) 50 University

of California Los Angeles Law Review. 69, 86. Fiss rails against what he sees as the inherent unfairness of the civil justice system, but his

argument is more ideological than practical. At some points, Fiss' argument sounds like a Marxist critique of the common law system rather

an analysis of practicalities and realities of weighing the risks inherent in litigated outcomes against ‘buying the risk’ and achieving certainty

through ADR.

116

There is a compelling argument for compulsion as it addresses any power imbalance between disputants as well as obdurate refusal by

one party to litigation to participate in ADR which, in this era, is contrary to the ‘overriding purpose’ of case management: eg see section

56(1) of the Civil Procedure Act 2005 (NSW).

117

In representative actions, however, courts are taking an increasingly supervisory role in relation to settlements to ensure that they are

reasonable and fair to the class compared to say the return to the litigation funders and the lawyers: Darwalla Milling Co Pty Ltd v Hoffman

La Roche Ltd & Ors (2006) 236 ALR 322 [41]; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Rich [2009] NSWSC 1229; 236 FLR 1;

Peterson v Merck Sharpe& Dohme (Aust) Pty Ltd (No 6) [2013] FCA 447; Camilleri v The Trust Company (Nominees) Limited [2015] FCA

1468 (fairness between claimants as to how settlement money is shared); Earglow Pty Ltd v Newcrest Mining Ltd [2016] FCA 1433 (Murphy

J adopted a fixed percentage); see also Michael Legg, 'Judge's Role in Settlement of Representative Proceedings: Lessons From United States

Class Actions' (2004) 78 Australian Law Journal 58.

118

The overwhelming thrust of the collaborative or therapeutic ADR literature, with the only exception of Fiss, supports this proposition.

119

One example is the telecommunications industry Ombudsman. This reflects a trend elsewhere to mediate industry specific disputes

especially where they are low value, high volume disputes with customers. It should be pointed out that ODR and EDR are not suited to

relationship restoration. The sine qua non of restorative justice in the ADR context is face-to-face meetings to re-establish any lost trust.

15

expense where publicly funded ADR programs exist. Where a private ADR session is held, the

parties usually share the cost of the ADR practitioner and the hiring of a venue and facilities;

these costs can be prohibitively expensive. If the dispute is not settled using ADR and proceeds

to litigation, it has been argued that ADR is, on one view, an additional and unnecessary cost.

Depending on the nature of the dispute, there are some cases where ADR will not save time,

particularly in urgent matters where an injunction is required or a time bar under a statute of

limitations needs urgent protection (by the filing of proceedings) or proceedings need to be filed

because the statute provides strict time frames in which to do so (eg proceedings to set aside a

winding up notice or the extension of a caveat by court order). There is no question that if urgent

steps need to be taken to preserve rights or the status quo, such steps ought to be taken.120

2.6

CATHARSIS

In English, ‘catharsis’121 has come to mean some kind of experience, process or series of events,

usually involving some form of suffering, through and as a result of which personal growth

occurs which paves the way for positive future outcomes. Such personal growth might be

spiritual, for example. It may also be an awareness of an ability to compromise rather than living

and dealing with conflict combatively. ADR is about managing values and aligning expectations.

We can experience catharsis corporately and personally as societies and as individuals. Few come

through serious forms of conflict unscathed. There are, for example, few winners in family law,

irrespective of the outcome. Most people emerge from conflict with a sense of having been

crushed by it or having endured and ultimately conquered something. Regrettably, all too often,

many people have no choice other than to endure conflict until a solution or outside help

becomes available. Often in modern Western societies, that outside help comes in the shape of a

lawyer who can help to vindicate or prosecute a right or help manage conflict. The best solution

to conflict resolution has been to nip conflict in the bud through alternative dispute resolution.

With case management and dispute resolution now very much part of the furniture of the

Australian legal system, lawyers, as officers of the court, have duties to advance these twin means

120

Very often, obtaining an injunction may be the first step towards a dispute being resolved through ADR or, conversely, if an injunction is

not obtained, whatever rights a party thought they had to submit to ADR may be prejudiced beyond retrieval. Taking steps to maintain the

status quo is vital for ADR to be effective. At times, parties must simply act as not doing so may result in their rights being so prejudiced that

any bargaining strength they may have had in ADR evaporates along with them. I am not advocating some kind of ‘pacifist’ approach to

ADR. Rights need to be preserved, not sat on or ignored to a party’s legal peril.

121

The etymology of which is Greek from the verb, kαθαρίζω (transliteration: katharitzo) meaning to purify or to make clean: Warren C

Trenchard, A Concise Dictionary of New Testament Greek (Cambridge University Press, 2003) 79.

16

of achieving the interests of justice, namely the ‘just, quick and cheap’ mandate, which has

become the hallmark of what courts expect of those involved in litigation and those representing

them. But in a rapidly changing legal environment, it may be that lawyers now have wider duties

than this. Lawyers need to be mindful of the context in which their clients’ disputes occur. Very

often nowadays, clients’ disputes are not taking place in one-off, never-to-be-repeated

circumstances, but in the context of ongoing commercial, personal and/or regulatory

relationships where it is in both parties’ interests to resolve the instant and potential future

disputes. There is also a strong societal interest in disputants learning from conflict and gaining

insight into how to better manage conflict and avoid disputes in the future. The need to consider

whether a duty to help clients restore relationships ought to be imposed on lawyers might serve

to undergird a competent and engaging framework for opportunities to move relationships beset

by conflict forward. Such a duty may be said to be foundational for avoiding future disputes.

Everyone has an interest in restoring and re-establishing a relationship if it really matters to them.

2.7

THE IMPORTANCE OF ‘BEING HEARD’