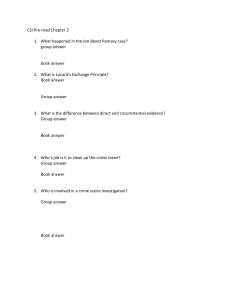

eBook An Introduction to Crime Scene Investigation 4th Edition Aric W. Dutelle

advertisement