eBook (EPUB) Willard and Spackmans Occupational Therapy 14e Glen Gillen; Catana Brown

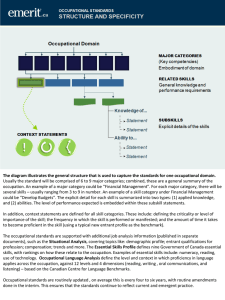

advertisement

Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Willard and Spackman's Occupational E FOURTEENTH EDITION ~i : i % ’ i P V ' a t 0‘, Wolters Kluwer * L * Glen Gillen Catana Brown Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com BRIEF CONTEN TS Unit Occupational Therapy: Profile of the Profession I Unit Occupational Nature of Humans II Unit Occupations in Context III Unit IV Occupational Therapy Process Unit Core Concepts and Skills V Unit VI Broad Conceptual Models for Occupational Therapy Practice Unit VII Evaluation, Intervention, and Outcomes for Occupations Unit VIII Evaluation, Interventions, and Outcomes for Performance Skills and Client Factors Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Unit IX The Practice Context: Therapists in Action Unit Occupational Therapy Education X Unit XI Occupational Therapy Management Introduction to Appendixes Glossary Index Appendixes (available on Lippincott Connect) Appendix Table of Interventions: Listed I Alphabetically by Title Appendix Table of Assessments: Listed II Alphabetically by Title Appendix First-Person Narratives III Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com CONTEN TS UNIT I Occupational Therapy: Profile of the Profession 1 What Is Occupation? Khalilah Robinson Johnson and Arameh Anvarizadeh 2 A Contextual History of Occupational Therapy Charles H. Christiansen and Kristine L. Haertl 3 A Philosophy of Occupational Therapy Barbara Hooper and Wendy Wood 4 Contemporary Occupational Therapy Practice and Future Directions Susan Coppola, Glen Gillen, and Barbara A. Boyt Schell 5 Occupational Therapy Professional Organizations Susan Coppola and Ritchard Ledgerd Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com 6 Scholarship in Occupational Therapy Catana Brown UNIT II Occupational Nature of Humans 7 Emergence, Development, and Transformation of Occupations Jennifer L. Womack and Nancy Bagatell 8 Contribution of Occupation to Health and WellBeing Clare Hocking and Daniel Sutton 9 Occupational Science: The Study of Occupation Clare Hocking and Margaret Jones 10 Occupational Justice Antoine Bailliard 11 Occupational Consciousness Elelwani Ramugondo UNIT III Occupations in Context 12 An Occupational Therapy Perspective on Families, Occupation, Health, and Disability Helen Bourke-Taylor, So Sin Sim, and Mehdi Rassafiani 13 Patterns of Occupation Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Kate Barrett and Kathleen Matuska 14 Culture, Equality, Inclusion, Diversity, and Culturally Effective Care Pablo A. Cantero Garlito, Daniel Emeric Meaulle, and Dahlia Castillo 15 Social, Economic, and Political Factors That Influence Occupational Performance Catherine L. Lysack, Diane E. Adamo, and Roshan Galvaan 16 Disability Rights in Action Aster (né Elizabeth) Harrison (Pronouns: They/Them) and Kimberly J. The (Pronouns: She/Her) 17 Physical and Virtual Environments: Meaning of Place and Space Noralyn D. Pickens and Cynthia L. Evetts UNIT IV Occupational Therapy Process 18 Overview of the Occupational Therapy Process and Outcomes Denise Chisholm and Barbara A. Boyt Schell 19 Evaluating Clients Inti Marazita, Thais K. Petrocelli, and Mary P. Shotwell 20 Critiquing Assessments Sherrilene Classen and Craig A. Velozo 21 Occupational Therapy Interventions for Individuals Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Glen Gillen 22 Occupational Therapy Evaluation and Intervention for Communities and Populations Bernard Austin Kigunda Muriithi 23 Best Practices for Health Education Leanne Yinusa-Nyahkoon and Sue Berger 24 Modifying Performance Contexts Leanne Leclair and Jacquie Ripat UNIT V Core Concepts and Skills 25 Professional Reasoning in Practice Barbara A. Boyt Schell and Angela M. Benfield 26 Evidence-Based Practice: Integrating Evidence to Inform Practice Nancy A. Baker, Linda Tickle-Degnen, and Elizabeth E. Marfeo 27 Ethical Practice Regina F. Doherty 28 Therapeutic Relationships and Person-Centered Collaboration: Applying the Intentional Relationship Model Carmen Gloria de las Heras de Pablo and Jaime Phillip Muñoz 29 Group Process and Group Intervention Moses N. Ikiugu Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com 30 Professionalism, Communication, and Teamwork Janet Falk-Kessler 31 Documentation in Practice Karen M. Sames 32 Safety, Infection Control, and Personal Protective Equipment Helene Smith-Gabai, Suzanne E. Holm, and John Lien Margetis UNIT VI Broad Conceptual Models for Occupational Therapy Practice 33 Examining How Theory Guides Practice: Theory and Practice in Occupational Therapy Ellen S. Cohn and Wendy J. Coster 34 The Model of Human Occupation Kirsty Forsyth and Catana Brown 35 Ecologic Models in Occupational Therapy Catana Brown 36 Theory of Occupational Adaptation Lenin C. Grajo and Angela K. Boisselle 37 The Kawa (River) Model Michael K. Iwama and Asako Matsubara Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com 38 The Model of Occupational Wholeness: An Emerging Theory in Occupational Therapy Farzaneh Yazdani 39 Recovery Model Skye Barbic and Krista Glowacki 40 Health Promotion Theories S. Maggie Reitz and Janet V. DeLany 41 Principles of Learning and Behavior Change Christine A. Helfrich UNIT VII Evaluation, Intervention, and Outcomes for Occupations 42 Introduction to Evaluation, Intervention, and Outcomes for Occupations Glen Gillen and Barbara A. Boyt Schell 43 Analyzing Occupations and Activities Barbara A. Boyt Schell, Glen Gillen, and Doris Pierce 44 Activities of Daily Living and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Jennifer S. Pitonyak and Kirsten L. Wilbur 45 Education in the United States Susan M. Cahill 46 Work Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Julie Dorsey, Holly Ehrenfried, Denise E. Finch, and Lisa A. Jaegers 47 Play and Leisure Anita C. Bundy and Sanetta Henrietta Johanna du Toit 48 Sleep and Rest Jo M. Solet 49 Social Participation Leanne Yinusa-Nyahkoon and Mary Alunkal Khetani 50 The Role of Occupational Therapy in Health Management: The Time to Act Is Now! Margaret Swarbrick and Laurie L. Knis-Matthews 51 Routines and Habits Elizabeth A. Pyatak UNIT VIII Evaluation, Interventions, and Outcomes for Performance Skills and Client Factors 52 Evaluating Quality of Occupational Performance: Performance Skills Anne G. Fisher and Lou Ann Griswold 53 Individual Variance: Body Structures and Functions Glen Gillen and Barbara A. Boyt Schell 54 Motor Function and Occupational Performance Dawn M. Nilsen and Glen Gillen Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com 55 Cognition, Perception, and Occupational Performance Joan Pascale Toglia and Yael Goverover 56 Sensory Processing in Everyday Life Evan E. Dean, Lauren M. Little, Anna Wallisch, Spencer Hunley, and Winnie Dunn 57 Emotion Regulation Jami E. Flick and Marjorie E. Scaffa 58 Social Interaction and Occupational Performance Lou Ann Griswold and C. Douglas Simmons 59 Personal Values, Beliefs, and Spirituality Christy Billock UNIT IX The Practice Context: Therapists in Action 60 Practice Settings for Occupational Therapy Pamela S. Roberts and Mary E. Evenson 61 Providing Occupational Therapy for Autistic Individuals Panagiotis (Panos) A. Rekoutis 62 Providing Occupational Therapy for Individuals With Traumatic Brain Injury: Intensive Care to Community Reentry Steven D. Wheeler, Amanda Acord-Vira, and Diana Davis Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com 63 Providing Wellness-Oriented Occupational Therapy Services for Persons With Mental Health Challenges Margaret Swarbrick 64 Providing Occupational Therapy for an Individual With a Hand Injury Marci L. Baptista and Maryam Farzad 65 Providing Occupational Therapy for Older Adults With Changing Needs Bette R. Bonder 66 Forced Migration and the Role of Occupational Therapy Mansha Mirza, Concettina Trimboli, Rawan AlHeresh, Md. Ariful Islam Arman, Mary Black, Theo Bogeas, Roshan Galvaan, Mohammad Monjurul Habib, and Yda J. Smith 67 Providing Occupational Therapy Services Through Telehealth Jana Cason and Ellen R. Cohn 68 Occupational Therapy Practice Through the Lens of Primary Health Care Sivuyisiwe Khokela Toto and Karen Ching 69 Providing Occupational Therapy Services for Persons With Childhood Trauma Erin Connor UNIT X Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Occupational Therapy Education 70 Fieldwork, Practice Education, and Professional Entry Emily Zeman Eddy, Amanda Mack, and Mary E. Evenson 71 Competence and Professional Development Winifred Schultz-Krohn 72 Preparation for Work in an Academic Setting Catana Brown, Tamara Turner, and Glen Gillen UNIT XI Occupational Therapy Management 73 Management of Occupational Therapy Services Brent Braveman 74 Supervision of Occupational Therapy Practice Patricia A. Gentile 75 Consultation as an Occupational Therapy Practitioner Paula Kramer 76 Payment for Healthcare Services Helene Lohman, Angela Patterson, and Angela M. Lampe Introduction to Appendixes Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Glossary Index Appendixes (available on Lippincott Connect) APPENDIX I Table of Interventions: Listed Alphabetically by Title Cheryl Lynne Trautman Boop APPENDIX II Table of Assessments: Listed Alphabetically by Title Cheryl Lynne Trautman Boop APPENDIX III First-Person Narratives • A: Narrative as a Key to Understanding, Ellen S. Cohn and Elizabeth Blesedell Crepeau • B: Who’s Driving the Bus? Laura S. Horowitz, Will S. Horowitz, and Craig W. Horowitz • C: Homelessness and Resilience: Paul Cabell’s Story, Paul Carrington Cabell III, Sharon A. Gutman, and Emily Raphael-Greenfield • D: While Focusing on Recovery, I Forgot to Get a Life, Gloria F. Dickerson (updated for the 14th edition) Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com • Mom’s Come to Stay, Jean Wilkins Westmacott E: • F: Journey to Ladakh, Beth Long • G: Experiences With Disability: Stories From Ecuador, Kate Barret • H: An Excerpt From The Book of Sorrows, Book of Dreams, Mary FeldhausWeber and Sally A. Schreiber-Cohn • He’s Not Broken—He’s Alex, Alexander McIntosh, Laurie McIntosh, and Lou I: McIntosh • J: The Privilege of Giving Care, Donald M. Murray Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com UNIT I Occupational Therapy: Profile of the Profession Media Related to Occupational Therapy: Profile of the Profession Readings Humans of New York: This blog and two books by Hugh Garry started out as a photography project and later included interviews of people on the streets of New York. Eventually, he added 20 additional countries. The intimate stories depict the varied human experience. (www.humansofnewyork.com) Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Movies Murderball: A documentary about the US wheelchair rugby team (mostly men with spinal cord injuries) who find purpose when they begin playing full-contact, and very competitive rugby. (2005) Inside: Bo Burnham created this comedy special that becomes more of a drama during COVID quarantine. It artistically depicts day-to-day life and Bo Burnham’s deteriorating mental health. (2021) Art Walter Anderson: An American artist known for his depictions of nature (1903–1965). He was diagnosed with schizophrenia and as a young adult, he spent time in psychiatric hospitals always managing to escape. Adolph Meyer was one of his psychiatrists. Although he was married and had four children, he led a reclusive life often alone creating artwork on a small island off the coast of Mississippi. (www.walterandersonmuseum.org) Music She Used to Be Mine: Sara Bareilles’s song about a woman who is disappointed in who she has become, but is still striving. (2015) Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com CHAPTER 1 What Is Occupation? Khalilah Robinson Johnson and Arameh Anvarizadeh OUTLINE KNOWING AND LEARNING ABOUT OCCUPATION THE NEED TO UNDERSTAND OCCUPATION Looking Inward to Know Occupation Looking Outward to Know Occupation Turning to Research and Scholarship to Understand Occupation DEFINING OCCUPATION CONTEXT AND OCCUPATION IS OCCUPATION ALWAYS GOOD? CATEGORIZING OCCUPATION REFERENCES LEARNING OBJECTIVES After reading this chapter, you will be able to: 1. Identify and evaluate ways of understanding occupation. 2. Articulate different ways of defining and classifying occupation. 3. Describe the relationship between occupation and context. Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Knowing and Learning About Occupation To be human is to be occupational. Occupation is a biological imperative, evident in the evolutionary history of humankind, the current behaviors of our primate relatives, and the survival needs that must be met through doing (Wilcock, 2006). Fromm (as cited by Reilly, 1962) asserted that people have a “physiologically conditioned need” to work as an act of self-preservation (p. 4). Humans also have occupational needs beyond survival. Addressing one type of occupation, Dissanayake (1992, 1995) argued that making art, or, as she describes it, “making special,” is a biological necessity of human existence. According to Molineux (2004), occupational therapists now understand humans, their function, and their therapeutic needs in an occupational manner in which occupation is life itself (emphasis added). Townsend (1997) described occupation as the “active process of living: from the beginning to the end of life, our occupations are all the active processes of looking after ourselves and others, enjoying life, and being socially and economically productive over the lifespan and in various contexts” (p. 19). In the myriad of activities people do every day, they engage in occupations all their lives, perhaps without ever knowing it. Many occupations are ordinary and become part of the context of daily living. Such occupations are generally taken for granted and most often are habitual (Gerlach et al., 2018; Hammell, 2009a; Wood et al., 2002). Listening to podcasts, laundering clothing, participating in religious activities, walking through a colorful market in a foreign country, and engaging with friends on social media platforms are occupations people do without ever thinking about them as being occupations. Occupations are ordinary, but they can also be special when they represent a new achievement, such as getting a driver’s license, or when they are part of celebrations and rites of passage. Preparing Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com and hosting a holiday dinner for the first time and baking pies for the annual family reunion for the 20th time are examples of special occupations. Occupations tend to be special when they happen infrequently and carry symbolic meanings, such as representing achievement of adulthood or one’s love for family. Occupations are also special when they form part of a treasured routine such as reading a bedtime story to one’s child, singing “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” and tucking the covers around the small, sleepy body. But even special occupations, although heavy with cultural nuances and tradition that transcend generations, change over time. Hocking et al. (2002) illustrated the complexity of traditional occupations in their study of holiday food preparation by older women in Thailand and New Zealand. The study identified many similarities between the groups (such as the activities the authors named “recipe work”), but the Thai women valued maintenance of an invariant tradition in what they prepared and how they did it, whereas the New Zealand women changed the foods they prepared over time and expected such changes to continue. Nevertheless, the doing of food-centered occupations around holidays was a tradition for both groups. The Need to Understand Occupation Occupational therapy (OT) practitioners need to base their work on a thorough understanding of occupation and its role in health and health behaviors, survival, and being in relation with others. That is, OT practitioners should understand what people need or are obligated to do individually and collectively to survive and achieve health and well-being. Wilcock (2007) affirmed that this level of understanding includes how people feel about occupation, how it affects their development, the societal mechanisms through which that development occurs, and how that process is understood. Achieving that understanding of occupation is more than having an easy definition (which is a daunting challenge in its own right). To Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com know what occupation is, it is necessary to examine what humans do with their time, how they come to choose and coordinate such activities, what purposes they serve, and what they mean for individuals and society. Personal experience of doing occupation, whether consciously attended to or not, provides a fundamental understanding of occupation—what it is, how it happens, what it means, what is good or harmful about it, and what is not. This way of knowing is both basic and extraordinarily rich. Looking Inward to Know Occupation To be useful to OT practitioners, knowledge of occupation based on personal experience demands examination and reflection. What do we do, how do we do it, when and where does it take place, and what does it mean? Who else is involved directly and indirectly? What capacities does it require in us? What does it cost? Is it challenging or uncomplicated? How has this occupation changed over time? What would it be like if we no longer had this occupation? To illustrate, Khalilah (first author) shares her experiences with cooking as she transitioned from home to college (OT Story 1.1). OT STORY 1.1 COOKING “SOUTHERN” AT COLLEGE My first real attempt at cooking a meal independently was my freshman year of college. My dorm had a full kitchen, and I, like many college students, loathed dining hall dinners. I had grown up in a home where my parents prepared dinner nightly and we ate together as a family. My grandparents cooked dinner for our extended family every Sunday, and as Southern culture would suggest, I learned the proper way to braise vegetables, season and smoke meat and fish, concoct gravies, and bake an array of casseroles prior to graduating high school. Meal preparation and meal execution generally adhere to rules and techniques according to the macro culture, local or home Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com culture of the person(s) performing it. Going to college required that I translate that cultural knowledge and adapt those rules to my new environment, understanding that the same products and tools to which I was accustomed would not be available. To build community, I began to cook traditional Southern meals in several kitchens around campus, taking up new ideas and techniques as I “broke bread” with other students. It was not until I received recognition from my peers that I considered myself a true Southern cook. Since that time, I have taken my love of cooking to international spaces, where I learn to prepare traditional meals of the native culture in a local person’s home (Figure 1.1). Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com FIGURE 1.1 Khalilah (on the right) preparing fish. Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Between college and the beginning of Khalilah’s postgraduate career, cooking took on a different form (the need to prepare meals for herself as an independent adult), function (family-style meals were no longer reserved for times with family and friends but became a means to forge relationships with strangers), and meaning (a way to bridge and create new cultural experiences with her family and friends). These elements—the form, function, and meaning of occupation—are the basic areas of focus for the science of occupation (Larson et al., 2003). Khalilah’s cooking and communal mealtime example described in OT Story 1.1 illustrates how occupation is a transaction with the environment or context of other people and cultures, places, and tools. It includes the temporal nature of occupation—seasonal travel to particular destinations and the availability of specific ingredients based on the season of travel. That she calls herself a cook exemplifies how occupation has become part of her identity and suggests that it might be difficult for her to give up cooking. Basic as it is, however, understanding derived from personal experience is insufficient as the basis for practice. Reliance solely on this source of knowledge has the risk of expecting everyone to experience occupation in the same manner as the therapist. So, although OT practitioners will profit in being attuned to their own occupations, they must also turn their view to the occupation around them and to understanding occupation through study and research. Looking Outward to Know Occupation As presented in this chapter and throughout this edition of Willard and Spackman, observation of the world through learning and observing others from differing backgrounds and experiences is another rich source of occupational knowledge. Connoisseurs of occupation can train themselves to new ways of seeing a world rich with occupations: the way a restaurant hostess manages a crowd when the wait for seating is long, the economy of movement of a Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com construction worker doing a repetitive task, the activities of musicians in the orchestra pit when they are not playing, the almost aimless social media scrolling on handheld devices as students take a break from class, and texting while engaging in social situations. Furthermore, people like to talk about what they do, and the scholar of occupation can learn a great deal by asking for information about people’s work and play. By being observant and asking questions, people increase their repertoire of occupational knowledge far beyond the boundaries of personal interests, practices, and capabilities. Observation of others’ occupations enriches the OT practitioner’s knowledge of the range of occupational possibilities (e.g., the types and ways of performing occupation that are deemed socially ideal) and of human responses to occupational opportunities (e.g., accessing and participating in occupation of one’s choosing) (Laliberte-Rudman, 2010). But although this sort of knowledge goes far beyond the limits of personal experience, it is still bounded by the world any one person is able to access, and it lacks the depth of knowledge that is developed through research and scholarship. Turning to Research and Scholarship to Understand Occupation Knowledge of occupation that comes from personal experience and observation must be augmented with the understanding of occupation drawn from research in OT and occupational science as well as other disciplines. Hocking (2000) developed a framework of needed knowledge for research in occupation, organized into the categories of the “essential elements of occupation … occupational processes … [and the] relationship of occupation to other phenomena” (p. 59). This research is being done within OT and occupational science, but there is also a wealth of information to be found in the work of other disciplines. For example, in sociology, Duneier (1999) studied the economy of work for poor Black men in Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com New York City neighborhoods; DeVault (1999) examined the dynamics of housework, in particular, family mealtimes; and Battle (2019) investigated the ways in which fathering is mediated through child support systems. Human geography researchers have studied the transactions between place, age, and care (Cutchin, 2005) and many other conceptualizations of home and community. Psychologists have studied habits (Aarts & Dijksterhuis, 2000; Wood et al., 2002) and a wealth of other topics that relate to how people engage in occupation. Understanding of occupation will benefit from more research within OT and occupational science and from accessing relevant works of scholars in other fields. Hocking (2009) has called for more occupational science research focused on occupations themselves rather than people’s experiences of occupations. Refer to Chapters 6 and 11. Defining Occupation For many years, the word occupation was not part of the daily language of occupational therapists, nor was it prominent in the profession’s literature (Hinojosa et al., 2003). According to Kielhofner and Burke (1977), the founding paradigm of OT was occupation, and the occupational perspective focused on people and their health “in the context of the culture of daily living and its activities” (p. 688). But beginning in the 1930s, the profession of OT entered into a paradigm of reductionism that lasted into the 1970s. One reason for the change was a desire to become more like the medical profession. During that time, occupation, both as a concept and as a means and/or outcome of intervention, was essentially absent from professional discourse. With time, a few professional leaders began to call for OT to return to its roots in occupation (Schwartz, 2003), and since the 1970s, acceptance of occupation as the foundation of OT has grown (Kielhofner, 2009). With that growth, professional debates about the definition and nature of occupation emerged and continue to this day. Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Defining occupation in OT is challenging because the word is part of common language with meanings that the profession cannot control. The term occupation and related concepts such as activity, task, employment, doing, and work are used in many ways within OT. It seems quite logical to think of a job, cleaning house, or bike riding as an occupation, but the concept is fuzzier when we think about the smaller components of these larger categories. Is dusting an occupation, or is it part of the occupation of house cleaning? Is riding a bike a skill that is part of some larger occupation such as physical conditioning or getting from home to school, or is it an occupation in its own right? Does this change over time? The founders of OT used the word occupation to describe a way of “properly” using time that included work and work-like activities and recreational activities (Meyer, 1922). Breines (1995) pointed out that the founders chose a term that was both ambiguous and comprehensive to name the profession, a choice, she argued, that was not accidental. The term was open to holistic interpretations that supported the diverse areas of practice of the time, encompassing the elements of occupation defined by Breines (1995) as “mind, body, time, space, and others” (p. 459). The term occupation spawned ongoing examination, controversy, and redefinition as the profession has matured. Nelson (1988, 1997) introduced the terms occupational form, “the preexisting structure that elicits, guides, or structures subsequent human performance,” and occupational performance, “the human actions taken in response to an occupational form” (Nelson, 1988, p. 633). This distinction separates individuals and their actual doing of occupations from the general notion of an occupation and what it requires of anyone who does it. Yerxa and colleagues (1989) defined occupation as “specific ‘chunks’ of activity within the ongoing stream of human behavior which are named in the lexicon of the culture…. These daily pursuits are self-initiated, goal-directed (purposeful), and socially sanctioned” (p. 5). Yerxa (1993) further elaborated this definition to incorporate an environmental perspective and a greater breadth of characteristics. She stated, Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Occupations are units of activity which are classified and named by the culture according to the purposes they serve in enabling people to meet environmental challenges successfully…. Some essential characteristics of occupation are that it is self-initiated, goal-directed (even if the goal is fun or pleasure), experiential as well as behavioral, socially valued or recognized, constituted of adaptive skills or repertoires, organized, essential to the quality of life experienced, and possesses the capacity to influence health. (Yerxa, 1993, p. 5) According to the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists (as cited in Law et al., 1998), occupation is “groups of activities and tasks of everyday life, named, organized and given value and meaning by individuals and a culture.” In a somewhat circular definition, they went on to state that “occupation is everything people do to occupy themselves, including looking after themselves (self-care), enjoying life (leisure), and contributing to the social and economic fabric of their communities (productivity)” (p. 83). Occupational scientists Larson et al. (2003) provided a simple definition of occupation as “the activities that comprise our life experience and can be named in the culture” (p. 16). Similarly, after referencing a number of different definitions of occupation, the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework affirmed the statement from the World Federation of Occupational Therapists (WFOT) that occupation refers “to the everyday activities that people do as individuals, in families, and with communities to occupy time and bring meaning and purpose to life. Occupations include things people need to, want to and are expected to do” (WFOT, 2012a, para. 2 as cited by American Occupational Therapy Association [AOTA], 2020, p. S7). The previous definitions of occupation from OT literature help in explaining why occupation is the profession’s focus (particularly in the context of therapy), yet they are open enough to allow continuing research on the nature of occupation. Despite, and perhaps because of, the ubiquity of occupation in human life, there is still much to learn about the nature of occupation through systematic research using an array of methodologies (e.g., Aldrich et al., 2017; Dickie, 2010; Johnson & Bagatell, 2017; Molke et al., 2004). Such research should include Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com examination of the premises that are built into the accepted definitions of occupation. At a more theoretical level, such an examination has begun. Several authors have challenged the unexamined assumptions and beliefs about occupation of Western occupational therapists (cf. Guajardo et al., 2015; Hammell, 2009a, 2009b; Iwama, 2006; Kantartzis & Molineux, 2011; Morrison et al., 2017; Ramugondo, 2015). These critiques center on the Western cultural bias in the definition and use of occupation across global contexts and the inadequacy of the conceptualization of occupation as it is used in OT in Western countries to describe the daily activities of most of the world’s population. Attention to these arguments will strengthen our knowledge of occupation. In this text, the following chapters, among others, will expand on these issues: Chapters 10, 11, and 37. Context and Occupation The photograph of four children using a magnifying glass to examine leaves on the ground evokes a sense of a mildly temperate day during a season when leaves begin to shed from trees (Figure 1.2). Exploring in a forest and looking at leaves has a context with temporal elements (possibly autumn on the east coast of the United States, the play of children, and the viewer’s memories of doing it in the past), a physical environment (wooded setting including pine straw, sticks, and leaves), and a social environment (four children and the likelihood of an indulgent parent or educator). The children looking at leaves cannot be described or understood—or even happen—without its context. It is difficult to imagine that any of the children would enjoy the activity as much doing it alone as the social context is part of the experience. This form of exploration might also be set up in an indoor or outdoor garden, but not in a simulated environment with inanimate objects. Parents or educators would be unlikely to allow the children to wander in an outdoor wooded area alone. The contexts of the people viewing the picture Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com are important, too; many will relate the picture to their own past experiences, but someone who lives in a place with less forestation might find the picture meaningless and/or confusing. In this example, occupation and context are enmeshed with one another. FIGURE 1.2 Children in forest looking at leaves together with the magnifying glass. It is generally accepted that the specific meaning of an occupation is fully known only to the individual engaged in the occupation (Larson et al., 2003; Pierce, 2001; Weinblatt et al., 2000). But it is also well accepted that occupations take place in context (sometimes referred to as the environment) (e.g., Baum & Christiansen, 2005; Kielhofner, 2002; Law et al., 1996; Schkade & Schultz, 2003; Yerxa et al., 1989) and thus have dimensions that consider other humans (in both social and cultural ways), temporality, the physical environment, and even virtual environments (AOTA, 2020). Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Description of occupation as taking place in or with the environment or context implies a separation of person and context that is problematic. In reality, person, occupation, and context are inseparable. Context is changeable but always present. Cutchin (2004) offered a critique of OT theories of adaptation-toenvironment that separate person from environment and proposed that John Dewey’s view of human experience as “always situated and contextualized” (p. 305) was a more useful perspective. According to Cutchin, “situations are always inclusive of us, and us of them” (p. 305). Occupation occurs at the level of the situation and thus is inclusive of the individual and context (Cutchin & Dickie, 2013; Dickie et al., 2006). OT interventions cannot be context free. Even when an OT practitioner is working with an individual, contextual element of other people, the culture of therapist and client, the physical space, and past experiences are present. Is Occupation Always Good? In OT, occupation is associated with health and well-being, both as a means and as an end. But occupation can also be unhealthy, dangerous, oppressive, maladaptive, or destructive to self or others and can contribute to societal problems and environmental degradation (Blakeney & Marshall, 2009; Hammell, 2009a, 2009b; Kiepek et al., 2019; Lavalley & Johnson, 2022; Twinley, 2013). Among many examples, scholars have described how notions of acceptable and unacceptable sexual activity for particular gender groups are reinforced through social norms, the tensions between experiencing pleasure as good or bad by individuals who engage in illicit activities, sedentary employment environments and their negative impact on health outcomes, accessibility of various recreational sports have historically excluded racially minoritized groups, and more. Further, the seemingly benign act of using a car to get to work, run errands, and pursue other occupations can limit one’s physical activity and risk injury to self and others. Americans’ reliance on the Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com automobile contributes to urban sprawl, the deterioration of neighborhoods, air pollution, and overuse of nonrenewable natural resources. Likewise, industry and the work that provides monetary support to individuals and families may cause serious air pollution in expanding economies such as that of China and Nigeria (Egbetokun et al., 2020; U.S. Department of State, 2020). Personal and societal occupational choices have consequences, good and bad. In coming to understand occupation, we need to acknowledge the breadth of occupational choices and their effects on individuals and society at large. Categorizing Occupation Categorization of occupations (e.g., into areas of activities of daily living [ADLs], work, and leisure) is often problematic. Attempts to define work and leisure demonstrate that distinctions between the two are not always clear (Snape et al., 2017). Work may be defined as something people have to do, an unpleasant necessity of life, but many people enjoy their work and describe it as “fun.” Indeed, Hochschild (1997) discovered that employees in the work setting she studied often preferred the homelike qualities of work to being in their actual homes and consequently spent more time at work than was necessary. The concept of leisure is problematic as well. Leisure might involve activities that are experienced as hard work, such as helping a friend to build a deck on a weekend. Take the two men plating salmon and vegetables (Figure 1.3) for example. Categorizing their activity presents a challenge. They are hovering over a kitchen counter, meticulously placing microgreens on top of the salmon using chef’s tweezers. Their activity may be categorized as engaging in work or other productive activity. However, what is not known is whether this is paid work, caregiving work (e.g., feeding others in the home), or leisure. Both men are dressed in a chef’s coat and an apron and utilizing tools that are not commonly used in home kitchens. This may give the appearance that they are engaging in paid work—chefs preparing a meal for Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com paying patrons. But only the gentleman on the left is a chef, which may lead you to interpret the situation as a leisure activity for the gentleman on the right. Categorizing the totality of this occupational situation is complicated. No simple designation of what is happening in the picture will suffice. FIGURE 1.3 Two men plating salmon and vegetables. Another problem with categories is that an individual may experience an occupation as something entirely different from what it appears to be to others. Weinblatt and colleagues (2000) described how an older woman used the supermarket for purposes quite different from provisioning (that would likely be called instrumental activities of daily living [IADLs]). Instead, this woman used her time in the store as a source of new knowledge and Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com interesting information about modern life. What should we call her occupation in this instance? The construct of occupation might very well defy efforts to reduce it to a single definition or a set of categories. Many examples of occupations can be found that challenge other theoretical approaches and definitions. Nevertheless, the richness and complexity of occupation will continue to challenge occupational therapists to know and value it through personal experience, observations, and scholarly work. The practice of OT depends on this knowledge. Lippincott© Connect For additional resources on the subjects discussed in this chapter, visit Lippincott Connect. EXPANDING OUR PERSPECTIVE The Value of Culture in Understanding Occupation Arameh Anvarizadeh Working in spaces that serve marginalized communities has been an enriching and humbling experience. One example of this is providing care to a child who recently immigrated to the United States from Iran to receive comprehensive rehabilitation services. He was a 7-year-old living with arthrogryposis and his parents were in dire need to have him engage in ageappropriate, meaningful occupations at home and in the school setting (e.g., playing with peers). Upon his arrival to the clinic, he was scheduled with occupational and physical therapists to complete his initial evaluation. However, there was one glaring issue—a language barrier. The therapists were having a difficult time identifying and understanding occupations that were important to the child and to his family. They were unable to define the context of the occupations his parents were describing to them. As an occupational therapist who strives to demonstrate cultural fluidity and humility at all times, I lent myself to assist in the evaluation because I was able to speak their language, Farsi. Once that barrier was removed, the family and child instantly felt the ability to connect in identity, in context, and in understanding occupation. I was able to dive deep in gathering a thorough occupational profile, while also collecting information about what he wants to Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com do, needs to do, but was unable to do because of physical limitations. We also were able to discuss his performance and satisfaction with the occupations that were important to him, such as dressing himself (donning socks and shoes specifically), playing with peers during recess (kicking a soccer ball), toileting, and feeding himself independently. Questions such as “tell me about your favorite meal” were compelling because I, too, understood the common meals served in Iranian culture—not just what the dishes were, but how they smelled, how they were served, how individuals engaged in mealtime together as a family unit. Taking all of these factors into consideration were important and guided me in writing very client-centered, culturally responsive goals. Attending Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) where I would observe educational staff and therapists speaking to the interpreter and not directly to the family, being in spaces where therapists would talk negatively about a client because they could not understand them, and watching clients experience frustration because of language barriers was difficult, yet a very valuable learning experience in advocating for all people, populations, and communities. More importantly, these experiences show why remaining grounded in cultural humility is critical in providing equitable care while maintaining client satisfaction. This child and family were ultimately added to my caseload. We built rapport, addressed all of his goals, and were creative in ensuring that he had access to the occupations that were meaningful to him. This experience along with similar stories demonstrates that understanding occupation is one factor; however, knowing that occupation serves multiple meanings based on the cultural implications is a significant part of our role as practitioners, leading the way in holistic and justice-based care. REFERENCES Aarts, H., & Dijksterhuis, A. (2000). Habits as knowledge structures: Automaticity in goal-directed behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.1.53 Aldrich, R., Rudman, D., & Dickie, V. (2017). Resource seeking as occupation: A critical and empirical exploration. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(3), 7103260010p1–7103260010p9. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2017.021782 American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process—fourth edition. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(Suppl 2), 7412410010p1–7412410010p87. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001 Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Battle, B. P. (2019). “They look at you like you’re nothing”: Stigma and shame in the child support system. Symbolic Interaction, 42(4), 640–668. https://doi.org/10.1002/symb.427 Baum, C. M., & Christiansen, C. H. (2005). Person-environment-occupationperformance: An occupation-based framework for practice. In C. H. Christiansen, C. M. Baum, & J. Bass-Haugen (Eds.), Occupational therapy: Performance, participation, and well-being (3rd ed., pp. 243–266). SLACK. Blakeney, A., & Marshall, A. (2009). Water quality, health, and human occupations. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(1), 46–57. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.63.1.46 Breines, E. B. (1995). Understanding “occupation” as the founders did. British 58(11), 458–460. Journal of Occupational Therapy, https://doi.org/10.1177/030802269505801102 Cutchin, M. P. (2004). Using Deweyan philosophy to rename and reframe adaptation-to-environment. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 58(3), 303–312. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.58.3.303 Cutchin, M. P. (2005). Spaces for inquiry into the role of place for older people’s Journal of Clinical Nursing, 14(s2), 121–129. care. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01280.x Cutchin, M. P., & Dickie, V. (2013). Transactional perspectives on occupation. Springer. DeVault, M. L. (1999). Comfort and struggle: Emotion work in family life. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 561(1), 52– 63. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271629956100104 Dickie, V. A. (2010). Are occupations “processes too complicated to explain”? What we can learn by trying. Journal of Occupational Science, 17(4), 195–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2010.9686696 Dickie, V., Cutchin, M., & Humphry, R. (2006). Occupation as transactional experience: A critique of individualism in occupational science. Journal of 13(1), 83–93. Occupational Science, https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2006.9686573 Dissanayake, E. (1992). Homo aestheticus: Where art comes from and why. University of Washington Press. Dissanayake, E. (1995). The pleasure and meaning of making. American Craft, 55(2), 40–45. Duneier, M. (1999). Sidewalk. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. Egbetokun, S., Osabuohien, E., Akinbobola, T., Onanuga, O. T., Gershon, O., & Okafor, V. (2020). Environmental pollution, economic growth and institutional quality: Exploring the nexus in Nigeria. Management of Environmental Quality, 31(1), 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEQ-02-2019-0050 Gerlach, A. J., Teachman, G., Laliberte-Rudman, D., Aldrich, R. M., & Huot, S. (2018). Expanding beyond individualism: Engaging critical perspectives on Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com occupation. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 25(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2017.1327616 Guajardo, A., Kronenberg, F., & Ramugondo, E. L. (2015). Southern occupational therapies: Emerging identities, epistemologies and practices. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.17159/23103833/2015/v45no1a2 Hammell, K. (2009a). Sacred texts: A sceptical exploration of the assumptions underpinning theories of occupation. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 76(1), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841740907600105 Hammell, K. (2009b). Self-care, productivity, and leisure, or dimensions of occupational experience? Rethinking occupational “categories.” Canadian 76(2), 107–114. Journal of Occupational Therapy, https://doi.org/10.1177/000841740907600208 Hinojosa, J., Kramer, P., Royeen, C. B., & Luebben, A. J. (2003). Core concept of occupation. In P. Kramer, J. Hinojosa, & C. B. Royeen (Eds.), Perspectives in human occupation: Participation in life (pp. 1–17). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Hochschild, A. R. (1997). The time bind: When work becomes home and home becomes work. Metropolitan Books. Hocking, C. (2000). Occupational science: A stock take of accumulated insights. Journal of Occupational Science, 7(2), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2000.9686466 Hocking, C. (2009). The challenge of occupation: Describing the things people Journal of Occupational Science, 16(3), 140–150. do. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2009.9686655 Hocking, C., Wright-St. Clair, V., & Bunrayong, W. (2002). The meaning of cooking and recipe work for older Thai and New Zealand women. Journal of 9(3), 117–127. Occupational Science, https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2002.9686499 Iwama, M. (2006). The Kawa model: Culturally relevant occupational therapy. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. Johnson, K., & Bagatell, N. (2017). Beyond custodial care: Mediating choice and participation for adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Occupational Science, 24(4), 546–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2017.1363078 Kantartzis, S., & Molineux, M. (2011). The influence of Western society’s construction of a healthy daily life on the conceptualisation of occupation. Journal of Occupational Science, 18(1), 62–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2011.566917 Kielhofner, G. (2002). Model of human occupation: Theory and application (3rd ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Kielhofner, G. (2009). Conceptual foundations of occupational therapy practice (4th ed.). F.A. Davis. Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Kielhofner, G., & Burke, J. P. (1977). Occupational therapy after 60 years: An account of changing identity and knowledge. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 31(10), 675–689. Kiepek, N., Beagan, B., Laliberte-Rudman, D., & Phelan, S. (2019). Silences around occupations framed as unhealthy, illegal, and deviant. Journal of 26(3), 341–353. Occupational Science, https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2018.1499123 Laliberte-Rudman, D. (2010). Occupational terminology: Occupational Journal of Occupational Science, 17(1), 55–59. possibilities. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2010.9686673 Larson, E., Wood, W., & Clark, F. (2003). Occupational science: Building the science and practice of occupation through an academic discipline. In E. B. Crepeau, E. Cohn, & B. Schell (Eds.), Willard & Spackman’s occupational therapy (10th ed., pp. 15–26). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Lavalley, R., & Johnson, K. R. (2022). Occupation, injustice, and anti-Black racism in the United States of America. Journal of Occupational Science, 29(4), 487– 499. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2020.1810111 Law, M., Cooper, B., Strong, S., Stewart, D., Rigby, P., & Letts, L. (1996). The person-environment-occupation model: A transactive approach to occupational performance. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(1), 9–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841749606300103 Law, M., Steinwender, S., & Leclair, L. (1998). Occupation, health and well-being. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65(2), 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841749806500204 Meyer, A. (1922). The philosophy of occupational therapy. Archives of Occupational Therapy, 1(1), 1–10. Molineux, M. (2004). Occupation in occupational therapy: A labour in vain? In M. Molineux (Ed.), Occupation for occupational therapists (pp. 1–14). Blackwell. Molke, D., Laliberte-Rudman, D., & Polatajko, H. J. (2004). The promise of occupational science: A developmental assessment of an emerging academic discipline. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(5), 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841740407100505 Morrison, R., Gómez, S., Henny, E., Tapia, M. J., & Rueda, L. (2017). Principal approaches to understanding occupation and occupational science found in the Chilean Journal of Occupational Therapy (2001–2012). Occupational Therapy International, 2017, 5413628. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/5413628 Nelson, D. L. (1988). Occupation: Form and performance. American Journal of 42(10), 633–641. Occupational Therapy, https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.42.10.633 Nelson, D. L. (1997). Why the profession of occupational therapy will flourish in the 21st century. The 1996 Eleanor Clarke Slagle Lecture. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 51(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.51.1.11 Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com Pierce, D. (2001). Untangling occupation and activity. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 55(2), 138–146. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.55.2.138 Ramugondo, E. (2015). Occupational consciousness. Journal of Occupational Science, 22(4), 488–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2015.1042516 Reilly, M. (1962). Occupational therapy can be one of the great ideas of 20th century medicine. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 16(1), 1–9. Schkade, J. K., & Schultz, S. (2003). Occupational adaptation. In P. Kramer, J. Hinojosa, & C. B. Royeen (Eds.), Perspectives in human occupation: Participation in life (pp. 181–221). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Schwartz, K. B. (2003). History of occupation. In P. Kramer, J. Hinojosa, & C. B. Royeen (Eds.), Perspectives in human occupation: Participation in life (pp. 18– 31). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Snape, R., Haworth, J., McHugh, S., & Carson, J. (2017). Leisure in a post-work World Leisure Journal, 59(3), 184–194. society. https://doi.org/10.1080/16078055.2017.1345483 Townsend, E. (1997). Occupation: Potential for personal and social transformation. Journal of Occupational Science: Australia, 4(1), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.1997.9686417 Twinley, R. (2013). The dark side of occupation: A concept for consideration. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 60(4), 301–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12026 U.S. Department of State. (2020). China’s air pollution harms its citizens and the https://ge.usembassy.gov/chinas-air-pollution-harms-its-citizens-andworld. the-world/ Weinblatt, N., Ziv, N., & Avrech-Bar, M. (2000). The old lady from the supermarket —Categorization of occupation according to performance areas: Is it relevant for the elderly? Journal of Occupational Science, 7(2), 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2000.9686468 Wilcock, A. A. (2006). An occupational perspective of health (2nd ed.). SLACK. Wilcock, A. A. (2007). Occupation and health: Are they one and the same? Journal of Occupational Science, 14(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2007.9686577 Wood, W., Quinn, J. M., & Kashy, D. A. (2002). Habits in everyday life: Thought, emotion, and action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1281– 1297. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.6.1281 Yerxa, E. J. (1993). Occupational science: A new source of power for participants in occupational therapy. Journal of Occupational Science: Australia, 1(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.1993.9686373 Yerxa, E. J., Clark, F., Frank, G., Jackson, J., Parham, D., Pierce, D., Stein, C., & Zemke, R. (1989). An introduction to occupational science, a foundation for occupational therapy in the 21st century. In J. A. Johnson & E. J. Yerxa (Eds.), Occupational science: The foundation for new models of practice (pp. 1–17). Haworth Press. Get complete eBook Order by email at goodsmtb@hotmail.com