Colombia's Foreign Policy: Respices & US Relations

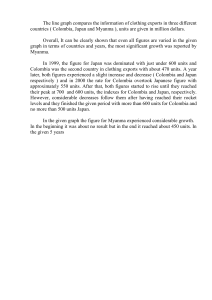

advertisement