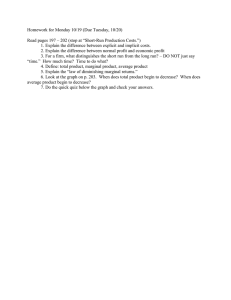

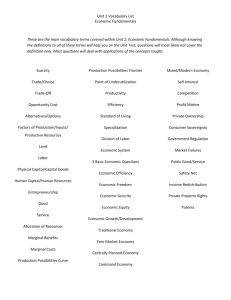

Chapter 1: Thinking Like An Economist 1. Scarcity Principle and the Scope and Nature of Economics 2. Main Topics in Microeconomics 3. Pitfalls in Economic Analysis (Cost-benefit analysis) A. Measuring costs & benefits as proportions instead of absolute amounts B. Ignoring implicit costs C. Failure to think at the margin 4. Normative economics vs positive economics 5. The Incentive Principle Economics is the study of how people, individually and collectively, make choices under the condition of scarcity and the implications of these choices for society (eg, in terms of the price and availability of goods and services and in terms of economic efficiency and social equality for society). Scarcity is a fundamental fact of life and the bane of our human existence. - resources to produce and consume goods and services are limited / finite - Limited / constrained / restricted by time, space and resources (resources are also known as factors of production and are broadly categorized as land, labor, capital and entrepreneurship in Economics) - Our human needs, wants and desires are unlimited / infinite (we are limited by time, resources, energy, health and other limitations, and we can never fully satisfy all our human needs, wants and desires, individually and collectively, all at the same time) - The Scarcity Principle is also informally known as the “no-free-lunch principle” (there is always a price to pay; a cost; a trade-off; a sacrifice for every choice we make; something has to give; you can’t “have your cake and still eat it”) Scarcity in Production and Consumption: - producing more of a good will result in less or even possibly no resources to produce other goods - consuming more of a good will result in less time, money, energy and other resources to consume other goods - scarcity affects us at all levels of human existence (individual, family, company, community, country and the world) and compels us to strive for efficiency (maximize benefits net of costs) - Cost-benefit principle helps us to make more efficient uses of scarce resources The choice to buy the keyboard downtown doesn't imply that you enjoy making the trip. It simply means that the trip is less unpleasant than the prospect of paying $10 extra for the keyboard (or that the value of the time and effort to make the trip is less than $10). You faced a trade-off and had to make a choice between the competing interests of a cheaper keyboard versus the free time gained if you avoided the trip. Economics is, in a sense, “the way” (道) of this present world that we are born into, the same “real world” we all will also depart from one day. MICROECONOMICS ▪ Microeconomics is the study of: ▪ individual choices (made by individual buyers and sellers of goods, services and resources); ▪ group behavior (all buyers and sellers of goods, services and resources) in specific markets; and ▪ the implications of these choices and behavior on: ▪ - the prices and quantities of specific goods and services produced and consumed in a market economy (with typically imperfect markets and subject to policy intervention by regulators) ▪ - economic efficiency & the welfare of society ▪ Microeconomic topics include ▪ - scarcity, efficiency; cost-benefit principle and economic welfare (total economic surplus) ▪ - demand and supply of goods and services in individual markets ▪ - price elasticity of demand and supply ▪ - cross-price and income elasticities of demand ▪ - consumer theory (utility-maximizing behavior of consumers) ▪ - production theory (profit-maximizing behavior of firms) ▪ - market failure: externalities and market power (barriers to entry); deadweight or efficiency loss THREE IMPORTANT PITFALLS IN COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS PITFALL 1: MEASURING COSTS AND BENEFITS AS PROPORTIONS RATHER THAN ABSOLUTE DOLLAR AMOUNTS Measuring costs and benefits as proportions instead of absolute amounts • A) Would you walk to town to save $10 on a $25 wireless keyboard? • B) Would you walk to town to save $10 on a $2,020 laptop? • Which one of the above-mentioned (A or B) yields higher marginal benefit to the person walking to town to purchase the item? • The economic surplus of an action is equal to its benefit minus its costs Total Costs Total Benefits Economic Surplus PITFALL 2: IGNORING IMPLICIT COSTS IN COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS The opportunity cost of a decision refers to the value of everything (in relation to the best alternative foregone) one must sacrifice that is related to that decision. For instance, if seeing a movie requires not only that you buy a $10 ticket, but also that you give up a $20 job that you could have done or would have been willing to do for free (meaning you derive value — “utility” — from this job), then the opportunity cost of watching the film is $30. Opportunity costs therefore comprise both implicit and explicit costs. Some more traditional economists and even textbooks use the term opportunity cost to refer only to the implicit value of opportunities forgone. Thus, in the example just discussed, these economists or textbooks wouldn't include the $10 ticket price when calculating the opportunity cost of seeing the film. Note that the opportunity cost of watching the movie is not the combined value of all possible activities you could have pursued, but only the value of your best alternative - the one you would have chosen had you not watched the movie. PITFALL 3: FAILING TO THINK AT THE MARGIN The Importance of Weighing Marginal Benefits Against Marginal Costs When deciding whether to take an action, the only relevant costs and benefits are those that would occur as a result of taking the action. The only costs that should influence a decision on whether to take an action are costs we can avoid by not taking the action. Similarly, the only benefits we should consider are the benefits that would not occur unless the action was taken. However, people are often influenced by sunk costs, which are costs that are beyond recovery at the moment a decision is made. For example, money spent on a buying a car is a sunk cost once you’ve paid for it. Sunk costs, such as the $100,000 you’ve paid for a car, cannot be recovered. As such, the price you paid for your car is irrelevant to a decision on whether it will be more cost-beneficial for you to drive to the city and park in the city to catch-up with friends, or to leave your car at home and take public transport instead. Famous College “Dropouts” PITFALL 3: FAILING TO THINK AT THE MARGIN The Importance of Weighing Marginal Benefits Against Marginal Costs and of Ignoring Sunk Costs in Decision-making When deciding whether to take an action, the only relevant costs and benefits are those that would occur as a result of taking the action. The only costs that should influence a decision on whether to take an action are costs we can avoid by not taking the action. Similarly, the only benefits we should consider are the benefits that would not occur unless the action was taken. However, people are often influenced by sunk costs, which are costs that are beyond recovery at the moment a decision is made. For example, money spent on a buying a car is a sunk cost once you’ve paid for it. Sunk costs, such as the $100,000 you’ve paid for a car, cannot be recovered. As such, the price you paid for your car is irrelevant to a decision on whether it will be more cost-beneficial for you to drive to the city and park in the city to catch-up with friends, or to leave your car at home and take public transport instead. COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS FOCUSES ON THE MARGINAL COST AND MARGINAL BENEFIT OF CHOICES AND DECISIONS • Marginal cost is the increase in total cost from one additional unit of an activity (eg: production or consumption activity) – Average cost is total cost divided by the number of units • Marginal benefit is the increase in total benefit from one additional unit of an activity – Average benefit is total benefit divided by the number of units The Cost Benefit Principle that states that an individual (or a firm or a society) should take an action (to allocate resources to produce and/or consume an additional unit of a good) if, and only if, the extra (marginal) benefits from taking the action are at least as great as the extra (marginal) costs. MC MB, MC ($) MC2 MB1 MB1 > MC1 MB2 < MC2 Equilibrium MB0 =MC0 MC1 MB2 MB Q1 Q0 Q2 Quantity of good/service Why does the MB curve slope downwards while the MC curve slopes upwards? - MB: Law of diminishing returns - MC: Law of increasing opportunity costs (“low hanging fruit” principle) MC MB, MC ($) MC2 MB1 MB1 > MC1 MB2 < MC2 Equilibrium MB0 =MC0 MC1 MB2 MB Q1 Q0 Q2 Quantity of good/service