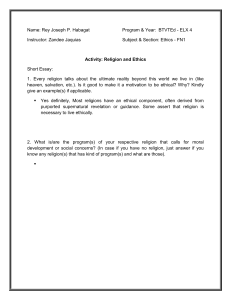

Andrew Ghillyer - Business Ethics Now-McGraw-Hill Education (2013)

advertisement