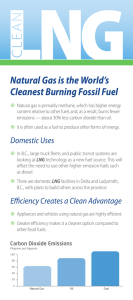

title transcript Baking apple pie? Discount orange warehouse has you covered! A fruit’s a fruit, right?It’s 1988, and scientist James Hansen has just testified to the United States Congress that global warming trends are caused by human activity, and will pose an increasing threat to humanity in the future.Well, well. That’s unusually prescient for a human.Looking for a wedding dress? Try a new take on a timeless classic. It’s sleek, flattering and modest— just like the traditional dress.Commercials. Could anything be more insufferable?It’s 1997, and the United States Senate has called a hearing about global warming. Some expert witnesses point out that past periods in Earth’s history were warmer than the 20th century. Because such variations existed long before humans, the witnesses claim the current warming trend is also the result of natural variation.Ah, there is something more insufferable than a commercial. Luckily for the humans, there’s one more expert witness.What are you looking at? We’re all dressed. At least we are by the logic you just used. It’s as if you were to say apples and oranges are both fruits, therefore they taste the same. Or that underwear, wedding dresses, and suits are all clothes, therefore, they’re all equally appropriate attire for a Senate hearing.The European wars of the 19th century and World War I were all wars, right?So World War I couldn’t be any more devastating than those other wars, could it?Let’s say two people have a fever. They must have the same disease that’s causing that fever, right?Of course not. One fever could be caused by chicken pox, the other by influenza, or any number of other infections. Like your claim about rising global temperatures, these claims make a false analogy. You're assuming that because two phenomena share a characteristic, in this case warming, they are analogous in Can other ways, like the cause of that warming.But there’s no evidence that that’s the you case. Yes, there have been other warm periods in Earth’s history— no one’s out disputing that the climate fluctuates. But let's take a closer look at some of those sma older examples of global warming, shall we?The Cretaceous Hot Greenhouse, rt 92 million years ago, was so warm, forests covered Antarctica. Volcanic activity the was likely responsible for boosting atmospheric carbon dioxide and creating a appl greenhouse effect.The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, 55 million years es ago, was so warm, crocodiles swam the waters of the Arctic Circle. This warming and may have been caused by the drying of inland seas and release of methane, a ora potent greenhouse gas, from ocean sediments,Even among these other warm nge periods, you’re making a false analogy. Yes, they had natural causes. But each s had a different cause, and involved a different amount and duration of warming. falla They’re as dissimilar as they are similar. Taking them together, all we can cy? reasonably conclude is that the Earth’s climate seems to change in response to conditions on the planet.Today, human activity is a dominant force shaping conditions on your planet, so the possibility that it’s driving global warming can’t be dismissed out of hand. I’ll grant that the more complicated something is, the easier it is to make a mistaken analogy. That’s especially true because there are many different types of false analogy: that similar symptoms must share a cause, that similar actions must lead to similar consequences, and countless others. Most false analogies you’ll come across are far less obvious than those comparing apples to oranges, and climate is notoriously complex. It requires careful, rigorous study and evidence collection— and making a false analogy like this only impedes that process.It’s 2013, and the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has found, aggregating decades of research, that there is more than a 95% chance the global warming trend since the mid-20th century has been driven by human activity, namely the burning of fossil fuels.You’re both pets, and he likes living in water, so you should, too. In college sports, American universities are exploiting, disproportionately, Black athletes for billions of dollars, while diminishing their education, health and safety. Let me start with a bit of history. In November 1984, an undersized quarterback from Boston College named Doug Flutie threw a game-winning touchdown pass against the defending national champions, University of Miami. As the Hail Mary pass floated through the fall air in front of a packed stadium, millions more watched with excitement on TV. After the dramatic win, undergraduate application rates at Boston College shot up by 30 percent, revealing to universities the enormous marketing value of building high-profile sports programs.That same year, the United States Supreme Court heard a case in which the Universities of Georgia and Oklahoma challenged rules that limited the number of football games they could play on TV. Those schools saw the opportunity to not only make money by televising their games, but to also market their universities to the world. The Supreme Court agreed that the broadcasting restrictions were illegal and schools began to negotiate TV deals The worth millions. That case opened the floodgates to money in college athletics, expl and with it, ever-growing conflicts of interest that prioritize sports over education, oita promote wins over health and safety and reinforce the disturbing racial and tion economic inequities in our country.Since then, the growth in college sports has of been extraordinary and schools have earned record revenues year after year. US The spending during that same time period has increased at almost the same coll dramatic pace, as universities engage in an arms race to the top of the rankings. ege Massive expenditures on new stadiums, bigger staffs and record salaries have athl made it appear, on the books at least, that athletic departments are losing etes money, while they build lavish facilities and make multimillionaires out of coaches and administrators. In fact, in 40 out of 50 states, the highest-paid public employee is now a college football or basketball coach. Meanwhile, college athletes, whose elite talents generate these massive revenues, are not only denied the ability to share in the riches they create, too many of them are not given the education they're promised, either.Today, college athletes are exploited to the tune of almost 15 billion dollars. That's how much money is generated by college sports each year. And I'm all too familiar with the exploitation, because I used to be responsible for enforcing it. Following my own college baseball career at the University of Dayton, I went on to law school before becoming an investigator at the National Collegiate Athletic Association. I traveled to college campuses across the country and helped enforce a 400-page rule book that denies athletes the right to get paid for their performance or even profit from their own name.For instance: unlike the music student who, in addition to their scholarship, can get paid to record a song, or the English student who, in addition to their scholarship, can get paid to write a book, college athletes cannot profit from their talents or even take a free meal without being ruled ineligible and risking their scholarship.During my time as an investigator, I questioned hundreds of athletes and their families about their financial transactions, dug through their personal bank and phone records and scrutinized their relationships to a humiliating degree, all for the possibility that someone gave them something beyond a scholarship, no matter how petty.In one case, I questioned Ohio State football players who received free tattoos and cash in exchange for memorabilia. The case received national attention and became known as "Tattoo Gate," as if it were a scandal on par with political espionage. The players were suspended and had to repay the cash as well as the value of the tattoos. In effect, unpaid athletes were fined by a billion-dollar organization that gets paid by sponsors to decorate the athletes in corporate logos. I was told my job was to promote fairness, but there was nothing fair about that. Shortly thereafter, I left the NCAA and started fighting for the athletes. It became increasingly clear to me that rules supposedly designed to prevent exploitation instead allow a collection of universities and their wealthy corporate sponsors to profit off the athletes, who are promised an education and lured by a chance at the pros but who too often end up with nothing.Now, some people believe college athletes get a free ride. However, there is nothing free about risking health and safety while working 40 to 50 hours per week as you fight to keep your scholarship. In football alone, there are over 20,000 injuries a year, including 4,000 knee injuries and 1,000 spinal injuries. Since 2000, forty players have died. Beyond football, a recent study revealed that an estimated 60 percent of Division 1 college athletes suffer a major injury in their career, and over half of them endure chronic conditions that last well beyond their playing days. There is nothing free about that, especially as the NCAA refuses to enforce health and safety standards and has denied in court it even has that responsibility.And about that education they're promised — according to the College Sports Research Institute, Black football and basketball players in the top five conferences graduate at 22 and 37 percent lower than the undergraduate population. Those who do graduate are often shuffled into majors with watereddown courses that conform to their athletic schedules to simply keep them eligible. The time demands and required focus on sports makes it challenging for even the most well-intentioned athlete to get a meaningful education. This is unacceptable for a 15 dollar billion industry run by institutions whose mission is to educate young people.Although plenty of athletes succeed, their achievements don't require rules that deny pay or a system that limits educational opportunities or neglects health and safety. The fact is, American universities oversee a multibillion-dollar entertainment industry that denies fundamental rights to its essential workers, a disproportionate number of whom are Black, while making millionaires of largely white coaches and administrators. This dynamic has not only deprived many young people of a meaningful education, it has shifted generations of wealth away from mostly Black families and represents the systemic inequities plaguing our society.The good news is that people are starting to see the truth. The NCAA's own public polling has revealed that a staggering 79 percent of the public believe that colleges put money ahead of their athletes. State and federal lawmakers, both Republican and Democrat, have also taken notice and started to act. Several US senators have rightly described the problems in college sports as a civil rights issue. Meanwhile, college athletes from across the country have started to stand up to demand greater health and safety protections, representation rights, attention to racial and social justice issues and economic fairness. Those who think the players should just stick to sports fail to recognize how rarely college athletes speak up and ignore the great personal risk they take in confronting a powerful industry, especially without any representation. More importantly, critics fail to acknowledge that college athletes are simply seeking rights that are afforded to virtually everyone else in this country and basic protections that shouldn't even be in question. I agree that college sports should be an enjoyable distraction, but not when they're distracting us from the very injustice they enable.In his retirement, the NCAA's first and longest-serving executive director, Walter Byers, described college sports as "the plantation mentality resurrected and blessed by today's campus executives." This is a telling quote from the man who designed this system and the one who knew it best. But you don't have to be an insider to recognize the exploitation of young people. You don't have to be a Republican or a Democrat to be troubled by the irresponsible spending or the disregard for values at our universities. You don't even have to be a sports fan. You just have to believe in basic ideas of fairness and the values of higher education.So let's require that all college athletes are given a chance at a meaningful education. Let's demand responsible spending by our universities and fairly allocate the billions of dollars being generated. Let's create robust health and safety standards to protect those who entertain us with their bodies and enforce those standards. Let's provide college athletes with a representative body so they have recourse when things go wrong and a voice about how to make things right. Finally, let's rise to the challenge of our time and once and for all correct the persistent racial and economic inequities that apply to college sports and beyond. Change is long overdue, but there has never been a better time than now. In a pitch-black cave, bats can’t see much. But even with their eyes shut, they can navigate rocky topography at incredible speeds. This is because a bat’s flight isn’t just guided by its eyes, but rather, by its ears. It may seem impossible to see with sound, but bats, naval officers, and doctors do it all the time, using the unique properties of ultrasound.All sound is created when molecules in the air, water, or any other medium vibrate in a pulsing wave. The distance between each peak determines the wave’s frequency, measured as cycles per second, or hertz. This means that over the same amount of time, a high frequency wave will complete more cycles than a low frequency one. This is especially true of ultrasound, which includes any sound wave exceeding 20,000 cycles per second.Humans can't hear or produce sounds with such high frequencies, but our flying friend can. When it’s too dark to see, he emits an ultrasound wave with tall peaks. Since the wave cycles are happening so quickly, wave after wave rapidly bounces off nearby surfaces. Each wave’s tall peak hits every nook and cranny, producing an echo that carries a lot of information. By sensing the nuances in this chain of echoes, our bat can create an internal map of its environment.This is how bats use sound to see, and the process inspired humans to try and do the same. In World War One, French scientists sent Ho ultrasound beams into the ocean to detect nearby enemy submarines. This early w form of SONAR was a huge success, in large part because sound waves travel doe even faster through mediums with more tightly packed molecules, like water. In s the 1950s, medical professionals began to experiment with this technique as a ultr non-invasive way to see inside a patient’s body. Today, ultrasound imaging is aso used to evaluate organ damage, measure tissue thickness, and detect und gallbladder stones, tumors, and blood clots. But to explore how this tool works in wor practice, let’s consider its most well-known use— the fetal ultrasound.First, the k? skin is covered with conductive gel. Since sound waves lose speed and clarity when traveling through air, this gooey substance ensures an airtight seal between the body and the wand emitting ultrasound waves. Then the machine operator begins sending ultrasound beams into the body. The waves pass through liquids like urine, blood, and amniotic fluid without creating any echoes. But when a wave encounters a solid structure, it bounces back. This echo is rendered as a dot on the imaging screen. Objects like bones reflect the most waves, appearing as tightly packed dots forming bright white shapes. Less dense objects appear in fainter shades of gray, slowly creating an image of the fetus’s internal organs.To get a complete picture, waves need to reach different depths in the patient’s body, bypassing some tissues while echoing off others. Since longer, low frequency waves actually penetrate deeper than short, high frequency ones, multiple frequencies are often used together and composited into a life-like image. The operator can then zoom in and focus on different areas. And since ultrasound machines send and receive cascades of waves in real time, the machine can even visualize movement.The waves used for medical ultrasound range from 2 million to 10 million hertz— over a hundred times higher than human ears can hear. These incredibly high frequencies create detailed images that allow doctors to diagnose the smallest developmental deviations in the brain, heart, spine, and more. Even outside of pre-natal care, medical ultrasound has huge advantages over similar technologies. Unlike radiation-based imaging or invasive surgical procedures, ultrasound has no known negative side effects when used properly. At very high levels, the heat caused by ultrasound waves can damage sensitive tissues, but technicians typically use the lowest levels possible. And since modern ultrasound machines can be small and portable, doctors can use them in the field— allowing them to see clearly in any medical emergency. First, a warning. As far as offensive words go, you are now entering a hard-hat An area. We're going to be unabashed in this, I am talking to you about a very hon particular word, a very powerful word, a very "see you next Tuesday" word. A est word that is still so offensive that the funders of this event would only let me talk hist about it if we censored it on the slides,(Laughter)which rather proves my point, ory don't you think? I love this word. Oh, my God, I love everything about this word, of not just what it signifies, but the actual sound of it, the fact that the C and the T an just cushion that "nnn" sound into this monosyllabic that you can just spit like a anci bullet or you can extend it out and roll it round your mouth, "cuuunt."I love its ent dexterity. I love the fact that in Scotland it’s a term of endearment, but in America and it's horrendously offensive. I love it means something different with your friends "na than it does if you said it to your boss, it would probably cost you your job. I do sty" not recommend it. I love this word.(Laughter)I love the fact that the first three wor letters are still the same chalice shape, all rolling through the word until they're d stopped in that plosive T at the end. I think the thing that I love most about it is its status as the nastiest of all the nasty words. Although that title is under some contention now. There are other obvious heavyweight contenders for the most offensive word. The N-word, for example. But here's what I would say to you. I know why that word is offensive. I can look at the history, that word enabled the brutalization and racial genocide of an entire group of people. It played its part in dehumanizing Black people. What did "cunt" do?(Laughter)Does it not strike anyone else as odd that a word that just means the vulva could even be regarded in the same league of offense as the N-word? Are we saying that vulvas are that offensive? Surely not.But what I want to talk to you today about is how did we get here? Has it always been this offensive and how did it come to be so? The answer is no, it was not. But let's look at the history of it first of all. Where in the cunt does "cunt" come from?(Laughter)It's one of those words that's so old, etymologists and linguists, they lose sight of it eventually. It's the oldest word for the vulva that we have in the English language. It might even be the oldest in the world. There are some theories. There are also similar cognitions in Germanic languages all across Europe. The Vikings would be talking about "kuntas," the Germans had “kuntō,” Dutch, “kont,” Germanic “kott,” and I think at one point we had "kott," which I think may be due for a revival.After that, it gets a bit confusing as to what this word actually means. One of the leading theories is that it shares this root, this Proto-Indo-European root with this “gen” sound, which you also see in "genetics," "gene," and that means "to create." Another theory is that it comes from this sound, "gune," which gives us “woman,” gynecology. "Create," "woman."But what really fascinates linguists is this sound, the “cuu” sound, because that gave us "cunt" also it gave us "cunning." "Cunning" originally didn't mean "sneaky." It meant you knew something. Cunning folk, cunning women were wise women. And in Scotland still today, if you can something, it means you know something. “I ken this.” It also gave us "queen" and "cow," slightly bizarre, which is slightly less highbrow, but — It turns up again in the Middle Ages in "quaint," which means "knowledge" and also means "cunt." It has a Latin variation as well, "cunnis," which also means "cunt," which turns up all over the Roman world, including in graffiti in Pompeii. Some of my favorite Roman graffiti from the city of Pompeii I won't try and do the Latin, but it's translated to be "A hairy cunt is better fucked than a smooth one."(Laughter)"It wants cock and holds in steam."(Laughter)There you go. However, I put it to you that the word "cunt," as offensive as it may be today, stems from a root that means "woman," "knowledge," "create," "cow." Has it always been this offensive? No.But we'll talk about this. So when we talk about these words, "vulva," "vagina," trying to offer more palatable alternatives to "cunt," "vagina," the word turns up in the 17th century. It's taken directly from Latin and it means a scabbard. It means something that a sword goes into. "Vulva" doesn't do much better. That appears in the 14th century, and it means "womb," but some people suggest it comes from the French and means "wrapper." Both these words derive their meaning and their import from the penis, basically. That's what a vagina is. It's something a sword goes into. I say that these words aren't as feminist as "cunt," which comes from a word that means "queen," "create," "wisdom," "cow."But when did it first start being used in English as we recognize it today? Gropecunte Lane, this is the first recorded incident in the Oxford English Dictionary, it turns up in 1230, a street name in London called Gropecunte Lane, which was exactly what it sounds like, this was in the red-light district of Southwark, it was a lane for groping cunts. And there wasn't just one in London, there was one in Bristol, there was one in York. It appears all over the British Isles. Here it is, the one in Bristol. Sorry, Oxford, there it is just in blue.But whereas Glaswegians might be calling each other and their friends "cunts," it seems that medieval people were calling their children "cunts" because it turns up in a number of names, bizarrely enough. Godwin Clawecunte is recorded in 1066, Gunoka Cuntles in 1219, John Fillecunt in 1246, Robert Clevecunt, 1302, and a Miss Bele Wydecunthe turns up in the Norfolk subsidiary role. We don't know if these are aliases or if they're jokes, but we do have a lot of fun with medieval names. In fact, originally the word "fuck" did not mean what it means today. It means to strike something to hit, which gives us the fabulous name of a dairy farmer in 1290 who’s known as Simon Fuckebotere.(Laughter)So was it this offensive to medieval people? No, it wasn't. "Cunts" turn up all over medieval culture and medieval literature. And they are certainly not offensive, it's just a descriptive term. Here's some examples. The "Proverbs of Hendyng" from 1325 advises women to "give your cunt cunningly and make your demands later," i.e. get a ring on it first before you give it up. There's a Welsh poet called Gwerful Mechain from the 15th century, and she advises male poets to celebrate the fine bright curtain of a cunt that flaps in place of greeting. It might surprise us that medieval culture was this open about cunts, but the truth was, they were more sexually liberated than we actually give them credit for. This idea of them being in a tower with a chastity belt on is largely a hatchet job on their reputation done by the Victorians. Now, it wasn't a sexually liberated utopia. They had their own hang-ups, but they weren't that offended by sex. What will get you in trouble, swearwords in the Middle Ages, was religious ones, blasphemous ones. If you said something like, "God's wounds" or "God's teeth," that’s what you’d say if you caught your soft and danglies in your fly.One medieval poet who dropped the C-bomb with the precision of a military drone is this chap, Geoffrey Chaucer, who turns up in GCSEs and A-levels syllabuses, although his cunt jokes are generally not dwelled upon. He doesn't use the word "cunt," he uses the word "queynte" here, which again means "knowledge" and it means "cunt." So this is his joke, “As the clerkes ben ful subtile and ful queynte, And prively he caughte hire by the queynte.” A rough translation means "the clerk was really cunning and he caught her by the cunt."Shakespeare. It's been suggestion that he uses that play, a quaint - queynte - cunt, in his Sonnet number 20. Here he is. It certainly turns up in a lot of his work. It's a lot ruder than we often give him credit for. In Hamlet, act three, scene two, Hamlet says to Ophelia, he says, "Shall I lie in your lap?" And she says, "Oh, no, my Lord." And then he says, "Do you think I meant country matters?" When David Tennant played that part, he paused "Do you think I meant count-ry matters?" to try and really drive it home. Another one, "Twelfth Night," Malvolio says of his mistress's handwriting, “There be her Cs, her Us, her Ts and thus she makes the very great Ps,” punning on "cunt" and "piss" simultaneously. The immortal Bard's status as a smut peddler is often swept under the cultural rug. In 1807, Thomas Bowdler published "The Family Shakespeare," where he edited out all of these jokes, all of the rude bits, and made it a completely cunt-free affair.It's no surprise that about this time we start to get the first libel laws in Britain, the first banning of seditious and offensive pamphlets with the rise of Puritanism. For Shakespeare to be veiling his cunt jokes in kind of cheeky double entendres suggests that it's not quite as free and open as Gunoka Cuntles and Gropecunte Lane would once have had.The Puritans repressed sexuality, we know this, and language is extremely important battleground for sexual liberation. How do you talk about your bodies if the very words you're trying to use are considered to be offensive? How do you do that? And by the time we get to the Restoration period, the early modern period, "cunt" is most certainly offensive. And this chap here, John Wilmot Earl of Rochester, is the absolute poster boy of "fuck you." If the Puritans tried to dam up sexuality, this guy surfed to notoriety on a wave of sexual repression that was unleashed when the plug was pulled on the Puritan rule. He uses "cunt" a lot and he's very naughty about it. He wrote this poem about his mistress and how jealous he was of her other lovers."When your lewd cunt came spewing home Drenched with the seed of half the town, My dram of sperm was supped up after For the digestive surfeit water. Full gorged at another time With a vast meal of slime Which your devouring cunt had drawn From porters’ backs and footmen’s brawn.”Sorry, everyone. He uses that word to shock, and it's easy to look at his work and think that he's sexually liberated, but he's actually quite angry at cunts and their owners and that goes all the way through it. From here on out, cunt is an offensive, naughty word.Georgian cunts, here we go.(Laughter)I'll just let that settle. So what happens about the 18th century is the print industry really explodes. And of course, we being humans, we didn't just want to publish nice books. We published porn, yay. There's a huge proliferation of porn that comes out of the 18th century. But oddly enough, most of it shies away from using that word "cunt." In 1785, Francis Grose published his book, "A Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue," which is basically a dictionary of slang. And he defined "cunt" as a "nasty name for a nasty thing." Such modesty from someone who also uses the word "buccaneer's boot," “lobster pot,” “skut” and “Mrs. Frub’s parlor” for the vulva.This book here, "Harris's List," this is an almanac, it's a directory of sex workers in London at the time, who were selling sex. And it lists not only their address and their prices, but very, very intimate descriptions of what they do and their vulvas. But it doesn't use "cunt" very much. This one here, this is an illustration, fabulous illustration from "Fanny Hill," what's often called the first pornographic novel, which was published in 1748 by John Cleland, who famously boasted that he did it without writing any rude words at all. These texts tend to use expressions like "mossy grot," "cupid's coal hole," “Venus’s mound,” but we shy away from "cunt."Victorians; so despite their reputation for being sexually prudish, pornography flowed underneath Victoria upper-crust society like a river of slime in "Ghostbusters II." They had pornography all over the place, visual and literary, and they had a lot of fun with "cunt."One of their pornographic magazines "The Pearl" was published from 1879 to 1880. and it published in it "nursery rhymes" every month. I've got some here for you to have a look at. "There was a young lady of Hitchin, Who was scrotching her cunt in the kitchen; Her father said, ‘Rose, It’s the crabs, I suppose.’ ‘You’re right, pa, the buggers are itching.’” “There was a young man of Bombay Who fashioned a cunt out of clay; But the heat of his prick Turned it into a brick, And (it) chafed all his foreskin away.”(Laughter)Yeah, well done, Victorians, well done. Interestingly, it's also in the 19th century that we get the first recorded use of "cunt" being used as an insult. As an actual, "You are a cunt." That's the first time that it's used in the 19th century. In the 17th century, it started being used as a kind of a derogatory collective noun for women. Samuel Pepys writes about this aphrodisiac that's going to make all the "cunts" chase after him. Charming. That's when they weren't stabbing him with pins for being too sexually aggressive.Anyway, the Victorians liked a well-placed "cunt." One of the most important "cunt" moments in history is this. Is the publication and the subsequent obscenity trial of “Lady Chatterley’s Lover.” This book contained 14 "cunts" and 40 "fucks," and it was banned and it had to go on trial in order to be published. And it was shocking, not just because of the graphic scenes of sex and the language used, but because it smashes down class boundaries. If you're not familiar with this, it's about Lady Constance Chatterley, a married woman who embarks on affair with with Sean Bean here but with Mellors the gamekeeper. And the idea is that it doesn't matter all her heirs and graces and titles, she’s got a cunt, she’s a sexual woman and that levels them. But one of the pivotal scenes is where Mellors tries to tell her what "cunt" means. I won't do the accent. “Nay nay! Fuck's only what animals do, but cunt's a lot more than that. It's thee, dost see: there's a lot more beside an animal, aren't ter? Even ter fuck? Cunt! Eh, that’s the beauty of thee lass!” "Cunt. That's the beauty of thee, lass!" I love that. Now, despite a jury that agreed a work stuffed full of cunts does have artistic merit and they allowed it to be published, and you can see the pictures of the people queuing around the streets to get their hands on this book once it was, "cunt" never really made it back into the mainstream.Feminists have maintained a rather uneasy relationship with "cunt." This is Judy Chicago. She led what was called The Cunt Art Movement of the 1970s. It first turned up in a film, a mainstream cinema in 1971 in "Carnal Knowledge" with Jack Nicholson, who screamed at a woman that she is a ball-busting son of a cunt bitch, or words to that effect. And in "The Exorcist" as well. It appears in "The Vagina Monologues," 1996, I think it was, with Eve Ensler when she talks about reclaiming "cunt." But it's still not off the linguistic naughty step, despite all of this work.Cunts today.(Laughter)It was it was finally admitted to the Oxford English Dictionary, despite having been around for thousands of years, in the '70s. And then in 2014, they relented a little bit more and they added “cunty,” “cuntish,” “cunted” and “cunting.” So we all know exactly what that means.The Ofcom, the regulator for UK TV censorship in 2016 released a poll of what they regarded to be the most offensive words and "cunt" was bang up there. It was on top. It is still regarded as a horrendously offensive word.But here's what I want to leave you with. What do you call yours? Because as far as I can see, words for vulva or cunts fall into a few categories. We've got child-like: a tuppence, a Twinkie, a foof, a minky, a Mary. Very medical: a vulva, pudendum, vagina. Slightly detached: down there, it's down there.(Laughter)Bits, special area. Violent: axe wound, penis flytrap, gash or a growler. The taxi driver on my way in told me that Glaswegian slang for cunnilingus is "growling at the badger," which — (Laughter)I'll leave that with you. Or they just tend to be unpleasant, horrible images of fish and meat and general putrescence, fish taco, bacon sandwich, badly stuffed kebab, bearded clam, etc. Are these better alternatives to "cunt?"But I think the reason that we're not prepared and we can't handle "cunt" is because we can't handle cunts generally. While it's been linguistically sanitized, culturally, the only cunts we seem to be OK with are the ones that have been plucked and buffed and waxed and glued and covered in glitter. So, vajazzled by the way. The vaginoplasty business is booming. You can have your labia cut off, you can have your hymen rebuilt, you can have your pelvic floor resprung. Are we this uncomfortable with the cunt actually as it is? It's a seat of enormous and awesome power. It can eat a penis and push out a baby, it's not a twinkle.(Laughter)It is an old word. It's an offensive word. But it's an ancient and honest one, and this is the thing. This is the original word, everything else came after. So welcome to Team Cunt.(Applause) Chris Anderson: Mike, welcome. It's good to see you. I'm excited for this conversation.Michael Levin: Thank you so much. I'm so happy to be here.CA: So, most of us have this mental model in biology that DNA is a property of every living thing, that it is kind of the software that builds the hardware of our body. That's how a lot of us think about this. That model leaves too many deep mysteries. Can you share with us some of those mysteries and also what tadpoles have to do with it?ML: Sure. Yeah. I'd like to give you another perspective on this problem. One of the things that DNA does is specify the hardware of each cell. So the DNA tells every cell what proteins it's supposed to have. And so when you have tadpoles, for example, you see the kind of thing that most people think is sort of a progressive unrolling of the genome. Specific genes turn on and off, and a tadpole, as it becomes a frog, has to rearrange its face. So the eyes, the nostrils, the jaws — everything has to move. And one way to think about it used to be that, well, you have a sort of hardwired set of movements where all of these things move around and then you get your frog. But actually, a few years ago, we found a pretty amazing phenomenon, which is that if you make so-called "Picasso frogs" — these are tadpoles where the jaws might be off to the side, the eyes are up here, the nostrils are moved, so everything is shifted — these tadpoles make largely normal frog faces. Now, this is amazing, because all of the organs start off in abnormal positions, and yet they still end up making a pretty good frog face. And so what it turns out is that this system, like many living systems, is not a hardwired set of movements, but actually works to reduce the error between what's going on now and what it The knows is a correct frog face configuration.This kind of decision-making that elec involves flexible responses to new circumstances, in other contexts, we would tric call this intelligence. And so what we need to understand now is not only the al mechanisms by which these cells execute their movements and gene blue expression and so on, but we really have to understand the information flow: prin How do these cells cooperate with each other to build something large and to ts stop building when that specific structure is created? And these kinds of that computations, not just the mechanisms, but the computations of anatomical orc control, are the future of biology.CA: And so I guess the traditional model is that hest somehow cells are sending biochemical signals to each other that allow that rate development to happen the smart way. But you think there is something else at life work. What is that?ML: Well, cells certainly do communicate biochemically and via physical forces, but there's something else going on that's extremely interesting, and it's basically called bioelectricity, non-neural bioelectricity. So it turns out that all cells — not just nerves, but all cells in your body — communicate with each other using electrical signals. And what you're seeing here is a time-lapse video. For the first time, we are now able to eavesdrop on all of the electrical conversations that the cells are having with each other. So think about this. We're now watching — This is an early frog embryo. This is about eight hours to 10 hours of development. And the colors are showing you actual electrical states that allow you to see all of the electrical software that's running on the genome-defined cellular hardware. And so these cells are basically communicating with each other who is going to be head, who is going to be tail, who is going to be left and right and make eyes and brain and so on. And so it is this software that allows these living systems to achieve specific goals, goals such as building an embryo or regenerating a limb for animals that do this, and the ability to see these electrical conversations gives us some really remarkable opportunities to target or to rewrite the goals towards which these living systems are operating.CA: OK, so this is pretty radical. Let me see if I understand this. What you're saying is that when an organism starts to develop, as soon as a cell divides, electrical signals are shared between them. But as you get to, what, a hundred, a few hundred cells, that somehow these signals end up forming essentially like a computer program, a program that somehow includes all the information needed to tell that organism what its destiny is? Is that the right way to think about it?ML: Yes, quite. Basically, what happens is that these cells, by forming electrical networks much like networks in the brain, they form electrical networks, and these networks process information including pattern memories. They include representation of large-scale anatomical structures where various organs will go, what the different axes of the animal — front and back, head and tail — are going to be, and these are literally held in the electrical circuits across large tissues in the same way that brains hold other kinds of memories and learning.CA: So is this the right way to think about it? Because this seems to be such a big shift. I mean, when I first got a computer, I was in awe of the people who could do so-called "machine code," like the direct programming of individual bits in the computer. That was impossible for most mortals. To have a chance of controlling that computer, you'd have to program in a language, which was a vastly simpler way of making big-picture things happen. And if I understand you right, what you're saying is that most of biology today has sort of taken place trying to do the equivalent of machine code programming, of understanding the biochemical signals between individual cells, when, wait a sec, holy crap, there's this language going on, this electrical language, which, if you could understand that, that would give us a completely different set of insights into how organisms are developing. Is that metaphor basically right?ML: Yeah, this is exactly right. So if you think about the way programming was done in the '40s, in order to get your computer to do something different, you would physically have to shift the wires around. So you'd have to go in there and rewire the hardware. You'd have to interact with the hardware directly, and all of your strategies for manipulating that machine would be at the level of the hardware. And the reason we have this now amazing technology revolution, information sciences and so on, is because computer science moved from a focus on the hardware on to understanding that if your hardware is good enough — and I'm going to tell you that biological hardware is absolutely good enough — then you can interact with your system not by tweaking or rewiring the hardware, but actually, you can take a step back and give it stimuli or inputs the way that you would give to a reprogrammable computer and cause the cellular network to do something completely different than it would otherwise have done. So the ability to see these bioelectrical signals is giving us an entry point directly into the software that guides largescale anatomy, which is a very different approach to medicine than to rewiring specific pathways inside of every cell.CA: And so in many ways, this is the amazingness of your work is that you're starting to crack the code of these electrical signals, and you've got an amazing demonstration of this in these flatworms. Tell us what's going on here.ML: So this is a creature known as a planarian. They're flatworms. They're actually quite a complex creature. They have a true brain, lots of different organs and so on. And the amazing thing about these planaria is that they are highly, highly regenerative. So if you cut it into pieces — in fact, over 200 pieces — every piece will rebuild exactly what's needed to make a perfect little worm. So think about that. This is a system where every single piece knows exactly what a correct planarian looks like and builds the right organs in the right places and then stops. And that's one of the most amazing things about regeneration. So what we discovered is that if you cut it into three pieces and amputate the head and the tail and you just take this middle fragment, which is what you see here, amazingly, there is an electrical gradient, head to tail, that's generated that tells the piece where the heads and the tails go and in fact, how many heads or tails you're supposed to have. So what we learned to do is to manipulate this electrical gradient, and the important thing is that we don't apply electricity. What we do instead was we turned on and off the little transistors — they're actual ion channel proteins — that every cell natively uses to set up this electrical state. So now we have ways to turn them on and off, and when you do this, one of the things you can do is you can shift that circuit to a state that says no, build two heads, or in fact, build no heads. And what you're seeing here are real worms that have either two or no heads that result from this, because that electrical map is what the cells are using to decide what to do.And so what you're seeing here are live two-headed worms. And, having generated these, we did a completely crazy experiment. You take one of these two-headed worms, and you chop off both heads, and you leave just the normal middle fragment. Now keep in mind, these animals have not been genomically edited. There's absolutely nothing different about their genomes. Their genome sequence is completely wild type. So you amputate the heads, you've got a nice normal fragment, and then you ask: In plain water, what is it going to do? And, of course, the standard paradigm would say, well, if you've gotten rid of this ectopic extra tissue, the genome is not edited so it should make a perfectly normal worm. And the amazing thing is that it is not what happens. These worms, when cut again and again, in the future, in plain water, they continue to regenerate as two-headed. Think about this. The pattern memory to which these animals will regenerate after damage has been permanently rewritten. And in fact, we can now write it back and send them back to being one-headed without any genomic editing. So this right here is telling you that the information structure that tells these worms how many heads they're supposed to have is not directly in the genome. It is in this additional bioelectric layer. Probably many other things are as well. And we now have the ability to rewrite it. And that, of course, is the key definition of memory. It has to be stable, long-term stable, and it has to be rewritable. And we are now beginning to crack this morphogenetic code to ask how is it that these tissues store a map of what to do and how we can go in and rewrite that map to new outcomes.CA: I mean, that seems incredibly compelling evidence that DNA is just not controlling the actual final shape of these organisms, that there's this whole other thing going on, and, boy, if you could crack that code, what else could that lead to. By the way, just looking at these ones. What is life like for a two-headed flatworm? I mean, it seems like it's kind of a trade-off. The good news is you have this amazing three-dimensional view of the world, but the bad news is you have to poop through both of your mouths?ML: So, the worms have these little tubes called pharynxes, and the tubes are sort of in the middle of the body, and they excrete through that. These animals are perfectly viable. They're completely happy, I think. The problem, however, is that the two heads don't cooperate all that well, and so they don't really eat very well. But if you manage to feed them by hand, they will go on forever, and in fact, you should know these worms are basically immortal. So these worms, because they are so highly regenerative, they have no age limit, and they're telling us that if we crack this secret of regeneration, which is not only growing new cells but knowing when to stop — you see, this is absolutely crucial — if you can continue to exert this really profound control over the three-dimensional structures that the cells are working towards, you could defeat aging as well as traumatic injury and things like this.So one thing to keep in mind is that this ability to rewrite the large-scale anatomical structure of the body is not just a weird planarian trick. It's not just something that works in flatworms. What you're seeing here is a tadpole with an eye and a gut, and what we've done is turned on a very specific ion channel. So we basically just manipulated these little electrical transistors that are inside of cells, and we've imposed a state on some of these gut cells that's normally associated with building an eye. And as a result, what the cells do is they build an eye. These eyes are complete. They have optic nerve, lens, retina, all the same stuff that an eye is supposed to have. They can see, by the way, out of these eyes. And what you're seeing here is that by triggering eye-building subroutines in the physiological software of the body, you can very easily tell it to build a complex organ. And this is important for our biomedicine, because we don't know how to micromanage the construction of an eye. I think it's going to be a really long time before we can really bottom-up build things like eyes or hands and so on. But we don't need to, because the body already knows how to do it, and there are these subroutines that can be triggered by specific electrical patterns that we can find. And this is what we call "cracking the bioelectric code." We can make eyes. We can make extra limbs. Here's one of our five-legged tadpoles. We can make extra hearts. We're starting to crack the code to understand where are the subroutines in this software that we can trigger and build these complex organs long before we actually know how to micromanage the process at the cellular level.CA: So as you've started to get to learn this electrical layer and what it can do, you've been able to create — is it fair to say it's almost like a new, a novel life-form, called a xenobot? Talk to me about xenobots.ML: Right. So if you think about this, this leads to a really strange prediction. If the cells are really willing to build towards a specific map, we could take genetically unaltered cells, and what you're seeing here is cells taken out of a frog body. They've coalesced in a way that asks them to re-envision their multicellularity. And what you see here is that when liberated from the rest of the body of the animal, they make these tiny little novel bodies that are, in terms of behavior, you can see they can move, they can run a maze. They are completely different from frogs or tadpoles. Frog cells, when asked to re-envision what kind of body they want to make, do something incredibly interesting. They use the hardware that their genetics gives them, for example, these little hairs, these little cilia that are normally used to redistribute mucus on the outside of a frog, those are genetically specified. But what these creatures did, because the cells are able to form novel kinds of bodies, they have figured out how to use these little cilia to instead row against the water, and now have locomotion. So not only can they move around, but they can, and here what you're seeing, is that these cells are coalescing together. Now they're starting to have conversations about what they are going to do. You can see here the flashes are these exchanges of information. Keep in mind, this is just skin. There is no nervous system. There is no brain. This is just skin. This is skin that has learned to make a new body and to explore its environment and move around. And they have spontaneous behaviors. You can see here where it's swimming down this maze. At this point, it decides to turn around and go back where it came from. So it has its own behavior, and this is a remarkable model system for several reasons. First of all, it shows us the amazing plasticity of cells that are genetically wild type. There is no genetic editing here. These are cells that are really prone to making some sort of functional body.The second thing, and this was done in collaboration with Josh Bongard's lab at UVM, they modeled the structure of these things and evolved it in a virtual world. So this is literally — on a computer, they modeled it on a computer. So this is literally the only organism that I know of on the face of this planet whose evolution took place not in the biosphere of the earth but inside a computer. So the individual cells have an evolutionary history, but this organism has never existed before. It was evolved in this virtual world, and then we went ahead and made it in the lab, and you can see this amazing plasticity. This is not only for making useful machines. You can imagine now programming these to go out into the environment and collect toxins and cleanup, or you could imagine ones made out of human cells that would go through your body and collect cancer cells or reshape arthritic joints, deliver pro-regenerative compounds, all kinds of things. But not only these useful applications — this is an amazing sandbox for learning to communicate morphogenetic signals to cell collectives. So once we crack this, once we understand how these cells decide what to do, and then we're going to, of course, learn to rewrite that information, the next steps are great improvements in regenerative medicine, because we will then be able to tell cells to build healthy organs. And so this is now a really critical opportunity to learn to communicate with cell groups, not to micromanage them, not to force the hardware, to communicate and rewrite the goals that these cells are trying to accomplish.CA: Well, it's mind-boggling stuff. Finally, Mike, give us just one other story about medicine that might be to come as you develop this understanding of how this bioelectric layer works.ML: Yeah, this is incredibly exciting because, if you think about it, most of the problems of biomedicine — birth defects, degenerative disease, aging, traumatic injury, even cancer — all boil down to one thing: cells are not building what you would like them to build. And so if we understood how to communicate with these collectives and really rewrite their target morphologies, we would be able to normalize tumors, we would be able to repair birth defects, induce regeneration of limbs and other organs, and these are things we have already done in frog models. And so now the next really exciting step is to take this into mammalian cells and to really turn this into the next generation of regenerative medicine where we learn to address all of these biomedical needs by communicating with the cell collectives and rewriting their bioelectric pattern memories. And the final thing I'd like to say is that the importance of this field is not only for biomedicine. You see, this, as I started out by saying, this ability of cells in novel environments to build all kinds of things besides what their genome tells them is an example of intelligence, and biology has been intelligently solving problems long before brains came on the scene. And so this is also the beginnings of a new inspiration for machine learning that mimics the artificial intelligence of body cells, not just brains, for applications in computer intelligence.CA: Mike Levin, thank you for your extraordinary work and for sharing it so compellingly with us. Thank you.ML: Thank you so much. Thank you, Chris. I am a linguist. Linguists study language. And we do this in a lot of different ways. Some linguists study how we pronounce certain sounds. Others look at how we build sentences. And some study how language varies from place to place, just to name a few. But what I'm really interested in is what people think and believe about language and how these beliefs affect the way we use it. All of us have deeply held beliefs about language such as the belief that some languages are more beautiful than others or that some ways of using language are more correct. And as most linguists know, these beliefs are often less about language itself and more about what we believe about the social world around Lan us.So I’m a linguist, and I'm also a nonbinary person, which means I don't gua identify as a man or a woman. I also identify as a member of a broader ge transgender community.When I first started getting connected to other aro transgender people, it was like learning a whole new language and the linguist und part of me was really excited. There was a whole new way of talking about my gen relationship with myself and a new clear way to communicate that to other der people. And then I started having conversations with my friends and family about and what it meant for me to be trans and nonbinary, what those words meant to me iden specifically, and why I would use both of them.I also clarified the correct words tity they could use when referring to me. For some of them, this meant some very evol specific changes. For example, some of my friends who are used to talking ves about our friend group as “ladies” or “girls” switched to nongendered terms like (an “friends” or “pals.” And my parents can now tell people that their three kids are d their son, their daughter and their child. And all of them would have to switch the alw pronouns they used to refer to me. My correct pronouns are “they” and “them,” ays also known as the singular they.And these people love me, but many of them has) told me that some of these language changes were too hard or too confusing or too ungrammatical for them to pick up. These responses led me to the focus of my research. There are commonly held, yet harmful and incorrect beliefs about language that for the people who hold these beliefs, act as barriers to building and strengthening relationships with the transgender people in their families and communities, even if they want to do so. Today, I'm going to walk you through some of these beliefs in the hope that we can embrace creativity in our language and allow language to bring us closer together. You might see your own beliefs reflected in these experiences in some way, but no matter what, I hope that I can share with you some linguistic insights that you can put into your back pocket and take with you out into the world. And I just want to be super clear. This can be fun. Learning about language brings me joy, and I hope that it can bring you more joy too.So do you remember how I said that for some of my friends and family learning how to use the singular they was really hard, and they said it was too confusing or too ungrammatical for them to pick up. Well, this brings us to the first belief about language that people have. Grammar rules don't change. As a linguist, I see this belief a lot out in the world. A lot of language users believe that grammar just is what it is. When it comes to language, what's grammatical is what matters. You can't change it.I want to tell you a story about English in the 1600s. Back then, as you might imagine, people spoke differently than we do today. In particular, they used "thou" when addressing a single other person, and "you" when addressing more than one other person, But for some complex historical reasons that we don't have time to get into today, so you'll just have to trust me as a linguist here, but people started using "you" to address someone, regardless of how many people they were talking to. And people had a lot to say about this. Take a look at what this guy, Thomas Elwood, had to say. He wrote, "The corrupt and unsound form of speaking in the plural number to a single person, ‘you’ to one instead of ‘thou,’ contrary to the pure, plain and single language of truth, ‘thou’ to one and ‘you’ to more than one.” And he goes on. Needless to say, this change in pronouns was a big deal in the 1600s.But actually, if you followed the debates about the singular they at all, these arguments might sound familiar to you. They're not that far off from the bickering we hear about the so-called grammaticality of pronouns used to talk about trans and nonbinary people. One of the most common complaints about the singular they is that if "they" is used to refer to people in the plural, it can't also be used to talk about people in the singular, which is exactly what they said about “thou” and “you.” But as we have seen, pronouns have changed. Our grammar rules do change and for a lot of different reasons. And we're living through one of these shifts right now. All living languages will continue to change, and the Thomas Elwoods of the world will eventually have to get with the program because hundreds of years later, it's considered right to use "you" when addressing another person. Not just allowable, but right.The second belief about language that people have is that dictionaries provide official, unchanging definitions for words. When you were in school, did you ever start an essay with a sentence like, "The dictionary defines history as ..." Well, if you did, which dictionary were you talking about? Was it the Oxford English Dictionary? Was it Merriam Webster? Was it Urban Dictionary? Did you even have a particular dictionary in mind? Which one of these is “the dictionary?” Dictionaries are often thought of as the authority on language. But dictionaries, in fact, are changing all the time. And here's where our minds are really blown. Dictionaries don't provide a single definition for words. Dictionaries are living documents that track how some people are using language. Language doesn't originate in dictionaries. Language originates with people and dictionaries are the documents that chronicle that language use.Here's one example. We currently use the word "awful" to talk about something that is bad or gross. But before the 19th century, "awful" meant just the opposite. People used "awful" to talk about something that was deserving of respect or full of awe. And in the mid-1900s, "awesome" was the word that took up these positive meanings and "awful" switched to the negative one we have today. And dictionaries over time reflected that. This is just one example of how definitions and meanings have changed over time. And to keep up with it, how dictionaries are updated all the time.So I hope you're starting to feel a little more comfortable with the idea of changing language. But of course, I'm not just talking about language in general. I'm talking about language as it is impactful for trans people. And pronouns are only one part of language, and they're only one part of language that's important for trans people. Also important are the identity terms that trans people use to talk about ourselves, such as trans man, trans woman, nonbinary or gender queer. And some of these words have been documented in dictionaries for decades now and others are still being added year after year. And that's because dictionaries are working to keep up with us, the people who are using language creatively.So at this point, you might be thinking, "But Archie, it seems like every trans person has a different word they want me to use for them. There are so many opportunities for me to mess up or to look ignorant or to hurt someone's feelings. What is something I can memorize and reliably employ when talking to the trans people in my life?" Well, that brings us to the third belief about language that people have. You can't just make up words.Folks, people do this all the time. Here's one of my favorite examples. The "official" term for your mother's mother or your father's mother is grandmother. I recently polled my friends and asked them what they call their grandmothers. We don't get frustrated if your friend's grandma goes by Meemaw and yours goes by Gigi. We just make rather short work of it and memorize it and move on getting to know her. In fact, we might even celebrate her by gifting her with a sweatshirt or an embroidered pillow that celebrates the name she has chosen for herself.And just like your Nana and your grandma, trans people have every right to choose their own identifying language. The process of determining self-identifying language is crucial for trans people. In my research, many trans people have shared that finding new vocabulary was an important part of understanding their own identities. As one person I interviewed put it, "Language is one of the most important personal things because using different words to describe myself and then finding something that feels good, feels right, is a very introspective and important process. With that process you can piece together, with the language that you find out works best for you, who am I?"Sometimes the words that feel good are already out there. For me, the words trans and nonbinary just feel right. But sometimes the common lexicon doesn’t yet hold the words that a person needs to feel properly understood. And it's necessary and exciting to get to create and redefine words that better reflect our experience of gender.So this is a very long answer, but, yes, I'm absolutely going to give you a magic word, something really easy you can memorize. And I want you to think of this word as the biggest piece of advice I could give you if you don't know what words to use for the trans people in your life. Ask. I might be a linguist and a trans person and a linguist who works with trans people, but I'm no substitute for the actual trans people in your life when it comes to what words to use for them. And you're more likely to hurt someone's feelings by not asking or assuming than you are by asking. And the words that a person uses might change. So just commit to asking and learning.Language is a powerful tool for explaining and claiming our own identities and for building relationships that affirm and support us. But language is just that, a tool. Language works for us, not the other way around. All of us, transgender and cisgender can use language to understand ourselves and to respect those around us. We're not bound by what words have meant before, what order they might have come in or what rules we have been taught. We can consider the beliefs that we might have had about how language works and recognize that language will continue to change. And we can creatively use language to build the identities and relationships that bring us joy. And that's not just allowable. It's right. Believe me. Non e A Satan, the beast crunching sinners’ bones in his subterranean lair. Lucifer, the brie fallen angel raging against the established order. Mephistopheles, the trickster f striking deals with unsuspecting humans.These three divergent devils are all hist based on Satan of the Old Testament, an angelic member of God’s court who ory torments Job in the Book of Job. But unlike any of these literary devils, the Satan of of the Bible was a relatively minor character, with scant information about his the deeds or appearance. So how did he become the ultimate antagonist, with so devi many different forms?In the New Testament, Satan saw a little more action: l tempting Jesus, using demons to possess people, and finally appearing as a giant dragon who is cast into hell. This last image particularly inspired medieval artists and writers, who depicted a scaled, shaggy-furred creature with overgrown toenails. In Michael Pacher’s painting of St. Augustine and the Devil, the devil appears as an upright lizard— with a second miniature face glinting on his rear and.The epitome of these monster Satans appeared in Italian poet Dante Alighieri’s “Inferno.” Encased in the ninth circle of hell, Dante’s Satan is a three-headed, bat-winged behemoth who feasts on sinners. But he’s also an object of pity: powerless as the panicked beating of his wings only encases him further in ice. The poem’s protagonist escapes from hell by clambering over Satan’s body, and feels both disgust and sympathy for the trapped beast— prompting the reader to consider the pain of doing evil.By the Renaissance, the devil started to assume a more human form. Artists painted him as a man with cloven hooves and curling horns inspired by Pan, the Greek god of the wild. In his 1667 masterpiece “Paradise Lost,” English poet John Milton depicted the devil as Lucifer, an angel who started a rebellion on the grounds that God is too powerful. Kicked out of heaven, this charismatic rebel becomes Satan, and declares that he’d rather rule in hell than serve in heaven.Milton’s take inspired numerous depictions of Lucifer as an ambiguous figure, rather than a purely evil one. Milton’s Lucifer later became an iconic character for the Romantics of the 1800s, who saw him as a hero who defied higher power in pursuit of essential truths, with tragic consequences.Meanwhile, in the German legend of Doctor Faust, which dates to the 16th century, we get a look at what happens when the devil comes to Earth. Faust, a dissatisfied scholar, pledges his soul to the devil in exchange for bottomless pleasure. With the help of the devil’s messenger Mephistopheles, Faust quickly seizes women, power, and money— only to fall into the eternal fires of hell.Later versions of the story show Mephistopheles in different lights. In Christopher Marlowe's account, a cynical Doctor Faustus is happy to strike a deal with Mephistopheles. In Johann Wolfgang van Goethe’s version, Mephistopheles tricks Faust into a grisly deal. Today, a Faustian bargain refers to a trade that sacrifices integrity for short-term gains.In stagings of Goethe’s play, Mephistopheles appeared in red tights and cape. This version of the devil was often played as a charming trickster— one that eventually paraded through comic books, advertising, and film in his red suit.These three takes on the devil are just the tip of the iceberg: the devil continues to stalk the public imagination to this day, tempting artists of all kinds to render him according to new and fantastical visions. (Voice-over) Andrew Youn: I have incredible belief in the strength and power of African farmers. The farmers I get to serve are incredibly inspiring, hardworking and confident, mostly women, that earn a better life for their families. They have an incredible amount of power. They're just not always equipped with the right tools. So my organization makes a few little tweaks and enables farm families to succeed at a whole nother level. At One Acre Fund, we like to say farmers stand at the center of the world.[Therese Niyonsaba, Farmer](Voice-over) (In Kinyarwanda) My name is Therese Niyonsaba. I started working with TUBURA in 2018.[In Rwanda, One Acre Fund operates under the name Tubura, which means “to grow exponentially.“](Voice-over) TN: I heard about TUBURA when the field officer came to meet farmers who had joined before me. I had seen how they were farming and I asked them, "Where do you get the fertilizer to yield such a good harvest?" They told me they get it from TUBURA.[Price Claudine, Field Officer ONE ACRE FUND / TUBURA](Voice-over) (In Kinyarwanda) PC: I first met Therese in 2018. She was eager to learn modern agricultural methods.(Women speaking)TN: My harvest was not enough to feed my family. I struggled to feed my children. I decided to expand my land to increase my harvest.AY: Most of the world's poor are farmers, and so when farmers become The more productive, then they earn more income, and mass numbers of people see move out of poverty. They produce more food for their communities and end ds hunger. From the farmer's perspective, basically, One Acre Fund provides a of small loan that makes these simple farm inputs affordable. So this is, for cha example, professional seed, which is 100 percent natural, locally produced; a nge tiny microdose of fertilizer, which is necessary for plant nutrients; and, for help example, tree seedlings. Then we provide physical delivery of these farm inputs ing and then training.(Voice-over) PC: With TUBURA, we improved planting Afri techniques. The skills the farmers learned include fertilizer application and using can selected seed to yield a good harvest. We also learned to plant in a line. That far helped us to get a better harvest.AY: We are an agricultural organization. mer Therefore, nearly all of our staff live in rural places near the farmers. And so it's s just so obvious to me that to provide effective service, we need to be as close as gro possible.PC: Before the inputs were close to the farmers, they had to travel long w distances and even pay for transport to pick them up. But today, they out immediately take their inputs home.(Voice-over) PC: When farmers are of harvesting, I visit them in their field to check if the crops are ready to be pov harvested. I advise them to wait until the crops are ready and are more useful to erty them.(Voice-over) TN: After joining TUBURA, my harvest remarkably increased. We can eat. We are so happy. And we sell the surplus of our harvest.AY: Today, we serve about a million families in our full-service program and a little more than a million families through our work with partners.(Voice-over) PC: My relationship with Therese is good. Every time I visit her, she is so happy.AY: In a nutshell, we have basically three goals with this Audacious proposal. One is to expand our direct full-service program to reach two and a half million families per year by 2026, which, more than 10 million children are living in those families. We can also hope by 2026 to serve an additional 4.3 million families per year, together with these kind of operational partners in the government and private sector. And then lastly, we want to help shape a more environmentally appropriate green revolution. There's an incredible opportunity for farmers to lead the way to lead to a more sustainable society, both in how we shape food systems and having more diverse food systems, but also, for example, planting tons and tons of trees. We can now realistically kick off a campaign to plant about a billion trees in the coming decade.(Voice-over) TN: After working with TUBURA, I was able to build my house. I was able to buy a solar light. I have light in my house! My children are eating. No problem. I'm so happy! Working with TUBURA gave me value. TUBURA is at my heart. I am so happy with TUBURA.(Music) After much debate, the fantasy realm you call home has decided dragon jousting may not be the best way to choose its leaders, and has begun transitioning to democracy. The candidates are a giant orange troll and an experienced tree statesman.An all-powerful eyebrow has hired your company— The Dormor Polling Agency— to survey the citizens of the land and predict who will win. There’s a lot riding on this: if you get it wrong, heads— well, your head— will quite literally roll. Your job is to go from door to door, asking voters whether they prefer the troll or the treefellow and to use the results to project how the election will go.Your fellow citizens want you to succeed and would tell you the truth... but Can there’s a problem. Few are willing to admit they support the troll on account of you his controversial life choices. If you were to ask a troll supporter who she'll vote solv for, there’s a good chance that she’ll claim to support the treeman, skewing your e results.You’re about to begin your rounds when a stranger offers you some the cryptic advice: “Here’s the question that will save your neck: what have you got fant in your pocket?”You reach into your pocket and pull out... a silver coin, which asy has the current king’s head on one side and his tail on the other. How can you elec use it to conduct an accurate poll?Pause here to figure it out yourself.Answer in tion 3Answer in 2Answer in 1The trick here is to use the coin to add random chance ridd to your interaction that will give troll supporters deniability. In other words, you’re le? looking for a system where when someone says “troll,” it could either be because the coin somehow told them to, or because they actually support the troll— and you’d have no way to tell the difference. You’ll also need to know how frequently the coin skewed the results, so you can account for it in your calculations.One solution is to have every pollee go into their house and flip the coin. If it lands heads, they should tell you “troll,” whether or not they actually support him. If it lands tails, they should tell you their actual preference.Here’s what happens: you pull 200 voters, and 130 say they’ll vote for the troll. For about 50%, or 100 of them, the coin will have landed heads. So you can subtract 100 troll votes off his total, and know the troll’s real support is 30 to 70, and he’s very likely to lose.The election comes around, but before the results can be certified a third party candidate swoops in and burns the treefellow to a crisp. The freshly signed and deeply flawed constitution mandates that this challenger gets to take his victim’s place in a new election.The Dormor Polling Agency sends you back out on the streets with your trusty coin. Only this time no one is comfortable admitting their preference: supporting the troll is still shameful, and nobody wants to express support of a dragon who murdered his way into the race.But your job is your job. How do you conduct an accurate poll now?Pause here to figure it out for yourself.Answer in 3Answer in 2Answer in 1This time, instead of masking just one candidate preference, you need some way to disguise both. At the same time, you also need to leave space for some portion of the people polled to express their true preference. But a coin toss only has two possible outcomes... right?Suppose you have everyone flip the coin twice— now there are four possible results. You can tell the people who flip heads twice in a row to report support for the troll; those who get tails twice in a row to report dragon; and those with any other combination to declare their true preference. The chances of getting either two heads or two tails in a row are 50% times 50%— or 25%. Subtracting that proportion of the total respondents from each candidate’s score should give you something close to the real distribution.This time, 105 respondents announced themselves in favor of the troll and 95 for the dragon. Out of the total, the coin will make 25% or 50 respond troll and another 50 respond dragon. Subtracting 50 from each result reveals that voters seem to prefer the troll by a margin of about 55 to 45.It’s close, but as predicted, the troll wins the election, and you live to poll another day. An Voting can be hard. It's been hard, sometimes painful, sometimes impossible, elec since the very beginning of our democracy. This year and years prior, we've tion seen voters wait in line for five, six and seven hours. And the issue hasn't been syst fixed. Now, some people may see these images and think, "How patriotic. How em impressive that someone would wait in line for seven hours just to vote." But to that me, it's not impressive at all. It's disrespectful to these voters. Making voting put difficult goes against the very core of our democracy. If we could redesign the s system to make it more convenient, more accessible and easier for voters, why vote wouldn't we?Now, the short answer is: political will. Many established politicians rs would not actually benefit personally from a reformed voting process that's (not inclusive for all voters. Politicians are the players in the game, but yet they set poli the rules for the game. Election policy must be about who votes, not who ticia wins.And the more complicated answer is that our voting system and election ns) system in the United States is highly decentralized and inconsistent. Over first 10,000 different local election officials administer this process in cities and towns and counties across the country. They might vary in size from 400 voters to 4.7 million. There's also 50 different state legislative bodies that set the rules of the game, and over 50 different chief election officials and entities that oversee those rules and how they're administered. So voting may vary greatly from state to state. Best-case scenario, you're in a state like Colorado, and a ballot is mailed to you proactively before each and every election. No bureaucracy, no extra paperwork. The ballot comes, and the government is responsible for delivering democracy to you. Worst-case scenario, you're in a state like Missouri, where your options are limited, you have overly restrictive voter registration deadlines. And if you can't get off work or you don't have childcare or you're sick, that's too bad. And most American voters don't fall into the best-case scenario.Now, in my career as an elections official for many years, and now leading the National Vote at Home Institute and our work to improve the voting process across the United States, I've talked to thousands of voters about their voting experience and thousands of election officials about the process. I also coauthored a book called "When Women Vote," that outlines a road map and a playbook for how to improve the process for all. And so I ask you: What would you choose? Which scenario would you choose?Now, the 2016 election was the most highly watched, most anticipated election in US history. And yet, only 60 percent of eligible Americans actually voted. Over 100 million people did not vote in 2016. And when they were surveyed as to why, over 40 percent indicated it was due to a barrier: missing a deadline, couldn't get off work, couldn't wait in line for hours. If "did not vote" was on the ballot in 2016, "did not vote" would have won in a landslide. What we end up with is a system where a minority of eligible Americans are choosing the politicians that make decisions for all of us collectively. Trust in the US government and politicians is at an all-time low, and the ballot box isn't helping. If we can't even cast a vote easily, why would we ever trust the process or trust politicians? We must put voters first. I'll say that again. We must put voters first in election policies and designing a system that serves them.Just ask any successful business. We live in an era of same-day shipping, free delivery, Lyft and Uber and take-home cocktails. And consumers, especially in the height of the pandemic, are choosing their experiences in the comfort of their home and on their schedules. So why can't we design a voting process that is as convenient as that?Luckily, we don't have to speculate. In Colorado, we've already designed that process, and Colorado is now one of the best states to vote in and also one of the most secure. In 2013, I worked with a group of dedicated leaders to redesign our voting process and pass legislation that put voters first. In Colorado, every voter receives a ballot ahead of each election. They're automatically registered to vote. There's no overly restrictive deadlines. And with BallotTRACE, voters can track their ballot just like they would a package, through the process, from the moment it's mailed to the moment the election official receives it for counting.That system was pioneered in Denver now 11 years ago. And when we designed it, we were able to reduce our call volume by 70 percent and infuse transparency and accountability into the process. Now, when you get that ballot at home, you can vote it and then mail it back in or drop it off in person. And if you want to vote in person, you can do that, too. And you're not confined to the government-assigned polling places on one day. You can go to any vote center — close to your kids' school, close to work, close to home — and you can do so over a few weeks prior to the election. It's been seven years since we passed that legislation and implemented that model. And the results are incredible.Colorado increased turnout significantly and now is one of the top states for voter turnout and also one of the most secure. We also saw a reduction in costs. So, because more people were voting at home, we didn't need as many poll workers, and we saw that reduce by over 70 percent. When we went to buy a new voting system, we no longer needed as much equipment. We also saw voters go farther down the ballot, to local races and ballot issues. And we saw turnout increase on those down-ballot races and issues. Those races include mayor and school board and city council. And they also include the really long legalese ballot issues that take forever to figure out. Voters now have a laptop in reach at their home, and they can research candidates and issues on their own time. We also have research now that shows that voting by mail and voting at home makes voters more informed because they have all of that extra time, as opposed to being in person and worrying about the long line of voters behind you while you're trying to rush through.And the final, most important aspect of the results that we've seen out of Colorado is about civics for future voters. And I want to share my story with my two elementary children. Every time my ballot comes before each election, one of my kids gets it, and they always start asking, "When are we going to fill out mom's ballot?" We sit down together, they read the instructions to me, they read the candidate names, and they ask me questions like, "Mom, what does governor do? What does the mayor do? Maybe I want to be a mayor someday." We research those issues together, we talk about it, and it takes me forever to complete my ballot. But I know that I have created lifelong, civically engaged voters and future voters that understand that the choices they make on that ballot impact their communities and their world. This is the type of voting experience that we want for every voter across the country.Many other states have taken notice, including California, Vermont, New Jersey, Hawaii. All have expanded options for voting at home this year, in 2020. Americans are resilient. We need a voting process that is also resilient — from a pandemic, from burdens and barriers, from inequities, from unfairness, from foreign adversaries and from administrative deficiencies. Across the country, voters are choosing to vote at home in record numbers. It is safe, it is secure, and we have built-in security measures to deter and detect bad actors who try to interfere with the process. Today, voting at home means paper ballots, but in the future, that might look very different.Voters deserve an awesome and safe voting experience, free from barriers and burdens. It's the politicians that serve us, not the other way around. You deserve excellence. Expect it, demand it and advocate for it.Thank you. You know those awkward icebreaker games, when everyone goes around and answers something like, "What's your favorite superpower?" When I was a kid, I loved those games. I believed I had the perfect answer. People would start sharing and I would wait, bouncing in my seat with excitement. And when it was my turn, I would proudly tell everyone, "The superpower I want most of all is to see people's emotions in color, hovering in the air around them." Wouldn't it be Wh cool if you could see how happy a friend was to see you, like they'd walk in and yI it would just fill with the color yellow. Or you could tell when a stranger needed pho help. You'd pass them on the street and you'd see this long trail of blue behind togr them. This was usually the moment where I would look around at the many aph blank faces telling me yet again, my cool superpower, it hadn't landed well with the my fellow fourth graders.I was an awkward child. That hasn't really changed. quie And neither has my deep appreciation for the emotional world around me or my t desire to both witness and capture the elusiveness of feelings. As I grew older, I mo started paying attention to the people and the stories I came across and I wrote men down what I saw. When writing didn't feel like enough, I learned photography ts and I began documenting the moments that felt most precious to me. With a of camera in hand, I learned the art of deciding what to include in the frame and grie what to let blur into the background. I graduated high school. I went to college. I f studied a combination of psychology and art. No shortage of feelings there, I can and assure you.And then ... I got sick. Not in a dramatic way. I didn't start screaming loss in agony or wake up unable to move or suddenly forget how to speak. Eventually, all those things would happen to some degree, but my path from wellness to illness was a slow, persistent movement towards deep sickness. I spent three years trying to identify the cause. I met with numerous doctors and the answer was always the same. There was nothing wrong with me. Over and over. Despite my persistent low-grade fever and joint pain and muscle aches, I was told, "Go see a therapist, practice more self-care." I started to believe they were right. Maybe nothing was wrong. Every test that came back normal had me falling further into a hole of self-doubt.I started grad school hoping that I would somehow get over this mysterious illness and I could return to life as it was before. Still there was a small, unwavering part of me that knew. Despite my symptoms not lining up with anything that made sense, I knew something was wrong. Eventually my cognitive symptoms worsened. Brain fog and memory loss and word-finding, and a doctor agreed to order an MRI. Assuring me they didn't think they'd find anything concerning. Instead ... they found a golf ball-sized mass in my right parietal lobe. And just like that, everything changed. I called my parents and I scheduled a date for brain surgery, and I dropped out of my grad program. They told me the tumor is probably benign and with its removal that I'd likely make a full recovery.I wish with all of my heart I could tell you they were right. I wish the story ended here. Six days after surgery, the pathology report came back telling us the tumor was not benign. It was something called an anaplastic astrocytoma and while the surgery had been successful and the tumor was gone, the microscopic cancerous cells it left behind remained, impossible to remove. In other words, I was officially diagnosed with a rare, aggressive, incurable brain cancer. Not my best day.My cancer is treatable, but it's highly recurrent. And when it does recur, it tends to return as terminal. The timeline of when, it's unpredictable. Some people get 15 years. Some people just get one. My doctors explained to me that while chemo and radiation would reduce the likelihood of recurrence, every three months for the rest of my life, I would need to return to the hospital to check for new tumor growth.As I listened, I met real grief for the first time. I thought of that superpower I'd once wanted and I imagined a deep dark purple filling the room around us. A cloak of color that I knew was going to stay with me. I'm 27. I thought to myself, how can this be happening? I was as determined as I was devastated. I wanted to fight and recover and I wanted as many years of life as possible. As I once again began to regain my strength, I started to pay attention to the people and the stories around me. In the hospital, I would push my walker down the hallway and I would steal glances into the rooms I'd passed and I would see these tiny worlds contained within them. Sometimes I could feel joy so big, I just wanted to stop and stand in it. Other times, the despair and the sadness made me want to run.About three months after I left the hospital I found out about an organization that offers free photo sessions to critically ill children and their families. Right away I called them. I set up a meeting and I signed up to volunteer. Despite my radiation-induced fatigue and my persistent grief, the idea of giving back in that way, it lit a spark within me that had been recently extinguished. For the first time in a while, I felt hope. It was as if a thin strand of gold had begun to weave its way through my coat of grief. And the color was blending slowly into something new.This organization offers their services to children at any stage of serious illness. And often they are joy-filled and they're celebratory. Other times a family asks for a photographer to document a child at the end of their life. Sometimes these are the only professional photos a family will ever have of their child. Often they're the last ones ever taken.The first call I got was for an end-of-life session for a three-year-old girl who'd been very sick for a long time. "She might pass while you're there," they warned me. "Are you sure you're up for it?" "Yes," I told them, completely unsure if I was. Now, I could tell you about this little girl's death, which happened a few days after I photographed her. I could, but I'm not going to. Instead, I want to show you the little girl's mother. How she kissed and stroked the hair of her daughter as she lay in that too big hospital bed. Even as the world as she knew it ended forever, she was there to give love to her daughter. I want you to see the dying girl's older brother. How he cried, but also how he took his yellow airplane and he flew it above her head. How I saw then a gesture of hope, colorful emotion, orange and gold. I want to bring you with me into the rooms where the mothers hold their babies and the families say goodbye. And I want to offer you the chance to see in frames, to choose the point of focus and blur the background, to see the details we so often miss, the moments of grace and beauty we assume don't exist in those desperate places. In the hardest moments imaginable, those families, they choose to love, despite and because of it all. I was not raised in religion and yet I can tell you, whatever you believe, those rooms are holy ground.When I was first diagnosed, I was certain grief would swallow me whole and some days I still think it might. I will never be at peace with the fact I might not get to be a mother. That I might not see my brothers get married, that I probably won't become old, like really old, the kind of old everyone else dreads and tries to fight against. I would've made a great old person. My grief — it's big. My fear of dying, of leaving behind the people I love. It's enormous. And my work photographing death has not erased that. Death itself is rarely beautiful and the images I capture reflect that too. The grief I have seen, the immensity of the loss — it's brutal.But when I walk into those rooms with that camera, my job is to do what I always wanted to do as a child. To capture the feeling and the connection and the emotion right there in front of me. And what I've learned from all these families and from my own wild terrain of grief is if I pay close enough attention, I don't need to see emotion in color after all. It's there and it's visible in the details. In the way our communities love each other through anything and everything. And with my camera, I can capture the evidence of that forever, and I can give it back to them to keep.Right now, my cancer is stable. I am so glad that for now, I get to keep living. Because that's the other side. My fear of dying, the pain of loss, it's only as strong as how much I love this life and the people in it with me. None of us are ever ready to say goodbye to the ones we love. Loss is devastating and try as we might, we can't avoid that shattering grief that follows in its wake. My guess is no matter who you are or what you've experienced so far, you already knew this. You too have grieved and all of us will grieve again. And when that happens, we will have a right to be angry. We can mourn as loudly as we want, and we should.But when the worst happens, we have a choice. You don't have to stay deep in the dark bitterness of loss and let that be the only thing that we see or feel. Because the one thing that's as strong and as powerful as our grief is our love for those who we have lost. And that love will remain like thousands of bright, colorful strands, woven forever through our cloak of grief, beautiful and awful, side by side, and ours to keep.Thank you. It’s 1481. In the city of Seville, devout Catholics are turning themselves in to the authorities. They’re confessing to heresy— failure to follow the beliefs of the Catholic Church. But why?The Spanish Inquisition has arrived in Seville. The Inquisition began in 1478, when Pope Sixtus IV issued a decree authorizing the Catholic monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, to root out heresy in the Spanish kingdoms— a confederacy of semi-independent kingdoms in the area that would become the modern country of Spain. Though the order came from the church, the monarchs had requested it. When the Inquisition began, the Spanish kingdoms were diverse both ethnically and religiously, with Jews, Muslims, and Christians living in the same regions. The Inquisition quickly turned its attention to ridding the region of people who were not part of the Catholic Church. It would last more than 350 years.On the ground, groups called tribunals ran the Inquisition in each region. Roles on a tribunal could include an arresting constable, a prosecuting attorney, inquisitors to question the accused, and a scribe. A “Grand Inquisitor,” a member of the clergy selected by the king and queen, almost always led a tribunal.The Inquisition marked its arrival in each new place with an “Edict of Grace.” Typically lasting 40 days, the Edict of Grace promised mercy to those who confess to heresy. After that, the inquisitors Ugl persecuted suspected heretics on the basis of anonymous accusations. So the y confessors in Seville probably didn’t see themselves as actual heretics— Hist instead, they were hedging their bets by reporting themselves when the ory consequences were low, rather than risking imprisonment or torture if someone else accused them later on.They were right to worry: once the authorities arrested someone, accusations were often vague, so the accused didn’t know the reasons for their arrest or the identity of their accuser. Victims were imprisoned for months or even years. Once arrested, their property was confiscated, often leaving their families on the street. Under these conditions, victims confessed to the most mundane forms of heresy— like hanging linen to dry on a Saturday.The Inquisition targeted different subsets of the population over time. In 1492, at the brutal Grand Inquisitor Tomás de Torquemada’s urging, the monarchs issued a decree giving Spanish Jews four months to either convert to Christianity or leave the kingdom. Thousands were expelled and those who stayed risked persecution. Converts to Christianity, known as conversos, weren’t even safe, because authorities suspected them of practicing Judaism in secret. The hatred directed at conversos was both religious and economic, as conversos made up a large portion of the upper middle class.The Inquisition eventually shifted its focus to the moriscos, converts to Christianity from Islam. In 1609, an edict passed forcing all moriscos to leave. An estimated 300,000 left. Those who remained became the Inquisition’s next targets.The inquisitors announced the punishments of those found guilty of heresy in public gatherings called autos de fé, or acts of faith. Hundreds of people gathered to watch the procession of sinners, mass, sermon, and finally the announcement of punishments. Most of the accused received punishments like imprisonment, exile, or having to wear a sanbenito, a garment that marked them as a sinner. The worst punishment was “relaxado en persona”— a euphemism for burning at the stake. This punishment was relatively uncommon— reserved for unrepentant and relapsed heretics.Over 350 years after Queen Isabella started the Inquisition, her namesake, Queen Isabella II, formally ended it on July 15th, 1834. The Spanish kingdoms’ dependence on the Catholic Church had isolated them while the rest of Europe experienced the Enlightenment and embraced the separation of church and state.Historians still debate the number of people killed during the Inquisition. Some suggest over 30,000 but most estimate between 1,000 and 2,000. The consequences of the Inquisition, however, reach far beyond fatalities. In some places, an estimated 1/3 of prisoners were tortured. Hundreds of thousands of members of religious minorities were forced to leave their homes, and those who remained faced discrimination and economic hardship. Smaller inquisitions in Spanish colonial territories in the Americas, especially Mexico, carried their own tolls.Friends turned in friends, neighbors accused neighbors, and even family members reported each other of heresy. Under the Inquisition, people were condemned to live in fear and paranoia for centuries. In 1998, my friends and I won a national art competition. The prize was a week in Disneyland Paris, with hundreds of other children from across the world, as delegates to UNESCO's International Children's Summit. Now this was no ordinary trip to Disneyland. Between running riot in the park and making friends, we workshopped the future of this planet. How could we overcome the problems of pollution and their threats to human and environmental health? How could we guarantee universal human rights of equality, justice and dignity?Towards the end of the summit, we created a 20-year time capsule, with each country planting a vision of the future they hoped for. But as I look around today, it's clear to me that those visions have not come true yet. We're confronted by the same crises, made infinitely worse through decades of geopolitical inaction. We now face global existential risks as a result of the climate emergency, with the world's least-resourced and most disenfranchised made more vulnerable despite having contributed least to the problem. That trip to Disneyland taught me that art and design had the power to imagine other possible futures. The question is: "How do we actually build them?"Today, I lead a design agency called Faber Futures, and my team and I design at the intersection of biology, technology and society. Through research and development collaborations, partnerships, and other strategies, we model a future in which both people and planet can thrive and where the role that biotechnology plays is shaped through plural visions.Our design work prototypes the future. We have developed toxin-free, water-efficient textile dye processes with a pigment-producing bacterium, pioneering new ways Pos of thinking about circular design for the textile and fashion industries.You've sibl probably already heard of data surveillance, but what if it was biological? Using e open-source data on the human microbiome, we’ve created experiential futu artworks that engage with the ethics of DNA mining. How can we embed a res culture of multidisciplinary codesign from within the industry of biotechnology? fro To find out, we designed the Ginkgo Creative Residency, which invites creative m practitioners to spend several months developing their own projects from within the the Ginkgo Bioworks foundry. We also generate and publish unique and inte expansive dialogues between people with different types of knowledges — rsec Afrofuturists with astrobiologists, food researchers with Indigenous campaigners. tion The stories that they and others tell give us the tools we need to imagine other of biological futures.Design deeply permeates all of our lives, and yet we tend to nat recognize things and not the complex systems that actually produce them. My ure, team and I explore these systems, connecting fields like culture and technology, tech ecology and economics. We identify problems, and where value and values can and be created. We like to think about a design brief as an instruction manual, soci mapping the context of the problem, and where we might find solutions.Getting ety there might involve establishing new networks, building new tools, and even infrastructure. How all of these pieces interact with one another can determine research and development, material specification, manufacturing and distribution. Who ultimately benefits, and at what environmental cost. So you can start to imagine the kinds of systems that might drive the design of your smartphone or even a rideshare service. But when it comes to the design of biology, things become a little bit more abstract.Organism engineers design microbes to do industrially useful things, like bioremediate toxic waste sites or replace petroleum-based textiles with renewable ones. To architect this level of biological precision and performance at scale, tools like DNA sequencing, automation and machine learning are essential. They allow the organism engineers to really zoom in on biology, asking scientific questions to solve deep technical challenges.Successful solutions designed at a molecular scale eventually interact with those at a planetary one. But if all of the research and development focuses on the technical question alone, then what do we risk by excluding the broader context? We've all spent over a year now living at an unprecedented intersection between biology, technology and society. We've witnessed, with the rapid development of the COVID-19 vaccine, that although techno-fixes offer us a critical remedy, they don't always provide a panaceum, and that’s because the real world is a complex social and economic one, where dominant systems determine the distribution of benefits.It will be another two years before hundreds of millions across the world receive their emergency vaccines, which, in a globalized world, risks undermining its efficacy on all our communities.Scientific endeavors have long been considered separate to realworld contexts, an idea that places profound limitations on the promises of biotechnology. By missing the full scope of design, we may think we’re solving problems and realize later that actually, not much has changed.And a similar logic is emerging in biotechnology for consumer goods and industry. So far, it offers innovations for commodities markets, drop-in replacements that change problematic ingredients, and yet sustain prevailing mindsets and dynamics of power. Again, technically sound solutions that unwittingly reinforce social and ecological inequities.Addressing these asymmetries requires us to take a more revolutionary approach, one that begins by asking "What kind of a world do we wish for?" So what if we could do both? What if we could design at the molecular scale, with the real world in mind? A more integrated approach to designing with biology requires us to ask more nuanced questions; not "What will people buy," but "What if we put communities, rather than commodities, first." "Could distributed biotechnology enable people to find local solutions to local problems?" "Can we move beyond a biotechnology that creates monocultures to one which, like nature itself, embraces a multiplicity of adaptations?" "How do we equip the next generation with the tools, spaces and communities they need to broaden their skills, knowledge and ideas?" An incredible amount of work that begins to address these questions is already underway.The Open Bioeconomy Lab, which has nodes in the UK, Ghana and Cameroon, designs open-source research tools to expand geographies of innovation into resource-constrained contexts. Over thousands of years, we've domesticated plants to make them edible, creating nutrient-rich, diverse and delicious food cultures. MicroByre wants to do the same, but for microbes. The San Francisco based start-up assembles diverse microbial libraries for a more resilient biological toolkit. Imagine the expanded color palettes and different applications, from different types of pigment-producing bacteria. And from London's famed art school, Central Saint Martins, students from different disciplines are generating new sustainable design practices from biological medium. You'll find them at work in a wet lab, nested between historic fashion textiles and architecture departments, a radical reunification of the arts and sciences in education. Many examples of this type of systemic design work in biotechnology exist — piece them together, and you start to glimpse different visions of our biological futures.I don't know what happened to the time capsule we left behind in Paris, but I do remember wishing for a more just and meaningful world, where all of nature can thrive. In their own significant ways, technology and design have played their role in denying us this, but it's in our power to change that. Fundamentally, this means recognizing that the design of, with and from biology is designing systems and not stuff, and that with a truly ambitious design proposition, one that’s based on values that center flourishing, caretaking and equity. We have the opportunity to build truly transformative systems, systems that open up holistic measures of value and impact, and how we think about scaling innovation and doing business for the futures we now need. Historically, most cars have run on gasoline, but that doesn’t have to be the case in the future: other liquid fuels and electricity can also power cars. So what are the differences between these options? And which one’s best?Gasoline is Wh refined from crude oil, a fossil fuel extracted from deep underground. The energy at's in gasoline comes from a class of molecules called hydrocarbons. There are the hundreds of different hydrocarbons in crude oil, and different ones are used to best make gasoline and diesel— which is why you can't use them fuel interchangeably.Fuels derived from crude oil are extremely energy dense, for bringing a lot of bang for your buck. Unfortunately, they have many drawbacks. you Oil spills cause environmental damage and cost billions of dollars to clean up. r Air pollution from burning fossil fuels like these kills 4.5 million people each year. car And transportation accounts for 16% of global greenhouse gas emissions, ? almost half of which comes from passenger cars burning fossil fuels. These emissions warm the planet and make weather more extreme. In the U.S. alone, storms caused by climate change caused $500 billion of damage in the last five years.So while gas is efficient, something so destructive can't be the best fuel. The most common alternative is electricity. Electric cars use a battery pack and electric motor instead of the internal combustion engine found in gas-powered cars, and must be charged at charging stations. With the right power infrastructure, they can be as efficient as gas-powered cars. If powered by electricity generated without fossil fuels, they can avoid greenhouse gas emissions entirely. They’re more expensive than gas-powered cars, but the cost difference has been shrinking rapidly since 2010.The other alternatives to gasoline are other liquid fuels. Many of these can be shipped and stored using the same infrastructure as gasoline, and used in the same cars. They can also be carbon-neutral if they’re made using carbon dioxide from the atmosphere— meaning when we burn them, we release that same carbon dioxide back into the air, and don't add to overall emissions.One approach to carbon-neutral fuel is to capture carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and combine its carbon with the hydrogen in water. This creates hydrocarbons, the source of energy in fossil fuels— but without any emissions if the fuels are made using clean electricity. These fuels take up more space than an energetically equivalent amount of gasoline— an obstacle to using them in cars.Another approach is to make carbon-neutral fuels from plants, which sequester carbon from the air through photosynthesis. But growing the plants also has to be carbon neutral— which rules out many crops that require fertilizer, a big contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. So the next generation of these fuels must be made from either plant waste or plants that don't require fertilizer to grow. Biofuels can be about as efficient as gasoline, though not all are.For a fuel to be the best option, people have to be able to afford it. Unfortunately, the high upfront costs of implementing new technologies and heavy subsidies for the producers of fossil fuels, mean that almost every green technology is more expensive than its fossil-fuel-based cousin. This cost difference is known as a green premium.Governments have already started subsidizing electric vehicles to help make up the difference. In some places, depending on the costs of electricity and gas, electric cars can already be cheaper overall, despite the higher cost of the car. The other alternatives are trickier, for now— zero-carbon liquid fuels can be double the price of gasoline or more. Innovators are doing everything they can to bring green premiums down, because in the end, the best fuel will be both affordable for consumers and sustainable for our planet. The Bruno Giussani: Hello. Bill Gates calls himself an imperfect messenger on inn climate because of his high carbon footprint and lifestyle. However, he has just ovat made a major contribution to our thinking about confronting climate change via a ions book, a book about decarbonising our economy and society. It's an optimistic we "can-do" kind of book with a strong focus on technological solutions. He nee discusses the things we have, such as wind and solar power, the things we need d to to develop, such as carbon-free cement or carbon-free steel, and long-term avoi energy storage. And he talks about the economics of it all, introducing the d a concept of green premium. The gist of the book, and really I'm simplifying here a clim lot, is that fighting climate change is going to be hard, but it's possible, we can ate do it. There is a pathway to a clean and prosperous future for all. So we want to disa unpack some of that with the author of the book. Bill Gates, welcome back to ster TED.Bill Gates: Thank you.Giussani: Bill, I would like to start where you start, from the title of the book. "How to Avoid a Climate Disaster," which, of course, presumes that we are heading towards a climate disaster if we don't act differently. So what is the single most important thing we must do to avoid a climate disaster?Gates: Well, the greenhouse gases we put into the atmosphere, particularly CO2, stay there for thousands of years. And so it's really the sum of all those emissions are forcing the temperature higher and higher, which will have disastrous effects. And so we have to take these emissions, which are presently over 51 billion tons per year and drive those all the way down to zero. And that's when the temperature will stop increasing and the disastrous weather events won't get worse and worse. So it's pretty demanding. It's not a 50 percent reduction. It's all the way down to zero.Giussani: Now, 51 billion is a big number. It's difficult to register, to understand. Help us visualize the scale of the problem.Gates: Well, the key is to understand all the different sources. And people are mostly aware of the production of electricity with natural gas and coal as being a big source. That's about 27 percent. And they're somewhat aware of transportation, including passenger cars. Passenger cars are seven percent and transportation overall is 16 percent. They have far less awareness of the other three segments. Agriculture, which is 19 percent, heating and cooling buildings, including using natural gas, are seven percent. And then, sadly, the biggest segment of all, manufacturing, including steel and cement. People are least aware of that one. And in fact, that one is the most difficult for us to solve. The size of all the steel plants, cement plants, paper, plastic, the industrial economy is gigantic. And we're asking that to be changed over in this 30-year period when we don't even know how to make that change right now.Giussani: So your core argument, and really, here I’m simplifying, is that basically we need to clean up all of that, right? The way we make things, we grow things, we get around and power our economy. And so to do that, we need to get to a point where green energy is as cheap as fossil fuels, and new materials, clean materials, are as cheap as current materials. And you call that "eliminating the green premium." So to start, tell us what you mean by green premium.Gates: Yeah, so the green premium varies from emission sources. It's the cost to buy that product where there's been no emissions versus the cost we have today. And so for an electric car, the green premium is reasonably modest. You pay a little more upfront, you save a bit on the maintenance and gasoline, you give up some range, you have a longer charging time. But over the next 15 years, because the volume is there and the R and D is being done, we can expect that the electric car will be preferable. It won't cost more. It will have a much higher range. And so that green premium that today is about 15 percent is headed to be zero even without any government subsidies. And so that's magic. That's exactly what we need to do for every other category.Now, an area like cement, where we haven't really gotten started yet, the green premium today is almost double the price. That is, you pay 125 dollars for a ton of cement today but it would be almost double that if you insisted that it be green cement. And so the way I think of this is in 2050 we'll be talking to India and saying to them, "Please use the green products as you're building basic shelter, you know, simple air conditioning," which they'll need because of the heat increase or lighting at night for students. And unless we're willing to subsidize it or the price is very low, they'll say, "No, this is a problem that the rich countries created, that India is suffering from and you need to take care of it." So only by bringing that green premium down very dramatically, about 95 percent across all categories, will that conversation go well so that India can make that shift.And so the key thing here is that the US's responsibility is not just to zero out its emissions. That's a very hard thing, but we're only 15 percent. Unless we, through our power of innovation, make it so cheap for all countries to switch all categories, then we simply aren't going to get there. And so the US really has to step up and use all of this innovative capacity every year for the next 30 years.Giussani: What what needs to happen in order for these breakthroughs to actually occur? Who are the players who need to come together?Gates: Well, innovation usually happens at a pace of its own. Here we have this deadline, 2050. And so we have to do everything we can to accelerate it. We need to raise the R and D budgets in these areas. In 2015 I organized, along with President Hollande and Obama, a side event to the Paris climate talks where what Prime Minister Modi had labeled "mission innovation" was a commitment to double R and D budgets over a five-year period. And all the big countries came in and made that pledge. Then we need lots of smart people, who, instead of working on other problems, are encouraged to work on these problems. So coming up with funding for them is very, very important. I'm doing some of that through what I call Breakthrough Energy Fellows. We need high-risk capital to invest in these companies, even though the risks are very, very high. And that's — There is now — Breakthrough Energy Ventures is one group doing that and drawing lots of other people in.But then the most difficult thing is we actually need markets for these products even when they start out being more expensive. And that's what I call Catalyst, organizing the buying power of consumers and companies and governments so that we get on the learning curve, get the scale going up, like we did with solar and wind across all these categories. So it's both supply of innovation and demand for the green products. That's the combination that can start us to make this change to the infrastructure of the entire physical economy.Giussani: In terms of funding all this, the financial system as a whole right now is essentially funding expansion of fossil fuels consistent with three degrees Celsius increase in global heating. What do you say to the Finance Committee, beyond the venture capital, about the need to think and act differently?Gates: Well, if you look at the interest rates for a solar field versus any other type of investments, it's not lower. You know, money is very fungible. It's going to, you know, different projects. But, there's no, sort of, special rate for climate-related projects. Now, you know, governments can decide through tax incentives to improve those things. But you know, this is not just about reporting numbers. It's good to report numbers. But the steel industry is providing a vital service. Even gasoline, for 98 percent of the cars being purchased today, allows people to get to their job. And so, you know, just divestment alone is not going to be the thing that creates the new alternative and brings the cost of that down. So the finance side will be important because the speed of deployment — Solar and wind needs to be accelerated dramatically beyond anything we've done today. In fact, you know, on average, we'll have to deploy three times as much every year as the peak year so far. And so those are a key part of the solution. They're not the whole solution. But you know, people sometimes think just by putting numbers, disclosing numbers, that somehow it all changes or by divesting that it all changes. The financial sector is important, but without the innovation, there's nothing they can do.Giussani: A lot of the current focus is on cutting emissions by half by 2030 and on the way to reaching that zero by 2050. And in the book, you write that there is danger in that kind of thinking, that we should keep our main focus on 2050. Can you explain that?Gates: Well, the only real measure of how well we’re doing is the green premium, because that's what determines whether India and other developing countries will choose to use the zero emission approach in 2050. The idea, you know — If you're focusing on short-term reductions, then you could say, oh, it's fantastic, we just put billions of dollars into natural-gas plants. And even ignoring that there's a lot of leakage that doesn't get properly measured, you know, give them full credit and say that's a 50 percent reduction. The lifetime of that plant is greater than 30 years. You financed it, assuming you're getting value out of it over a longer period of time. So to say, "Hey, hallelujah, we switched from coal to natural gas," that has nothing to do with reaching zero. It sets you back because of the capital spending involved there. And so it's not a path to zero if you're just working on the easy parts of the emission. That's not a path. The path is to take every source of emission and say, "Oh, my goodness, how am I going to get that green premium down? How am I going to get that green premium down?" Otherwise, getting to 50 percent does not stop the problems. This is very tough because the nature is zero. It's not just, you know, a small decrease.Giussani: So getting the green premium down, so you mentioned India. To make sure that the transition, the clean transition, is also an Indian story and an African story and not only a Western story, should rich countries adopt the expensive clean alternatives now, to kind of buy down the green premium and make technology, therefore, more accessible to low-income countries?Gates: Absolutely. You have to pick which product paths with scale will become low green-premium products. And so you don't want to just randomly pick things that are low-emission. You have to pick things that will come down. So like, you know, so far, hydrogen fuel cells have not done that. Now they might in the future. Solar, wind and lithium-ion, we've seen these incredible cost reductions. And so we have to duplicate that for other areas, things like offshore wind, heat pump, new ways of doing transmission. You know, we have to keep the electricity grid reliable, even in very bad weather conditions. And so that's where storage or nuclear and transmission will have to be scaled up in a very significant way, which we now have this open-source model to look at that. And so the buying of green products that demand signal, what I call Catalyst, we're going to have to orchestrate a lot of money, many tens of billions of dollars for that, that is one of the most expensive pieces so that the improvements come in these other areas and some of them we haven't even gotten started on.Giussani: Many people believe actually that the climate question is mostly a question of consuming less and particularly consuming less energy. And in the book, you actually write several times that we need to consume more energy. Why?Gates: Well, the basic living conditions that we take for granted should be made available to all humans. And the human population is growing. And so you're going — as you provide shelter, heating and air conditioning, which anywhere near the equator will be more in demand since you'll have many days where you can't go outdoors at all. So we're not going to stop making shelter. We're not going to stop making food. And so we need to be able to multiply those processes by zero. That is, you make shelter, but there's no emissions. You make food, but there's no emissions. That's how you get all the way down to zero. Now, it's made somewhat easier if rich countries are consuming less, but how far will that go?Giussani: So if I summarize in my head your book, you are basically suggesting that if we eliminate the green premium, the transition somehow can occur, the cost and technology, green premium and breakthroughs are the key drivers. But, you know, you think of climate and climate is kind of a wicked problem. It has implications that are social, political, behavioral. It requires significant citizen involvement. Are you focusing too much on tech and not enough on those other variables?Gates: Well, we need all these things. If you don't have a deep engagement, particularly by the younger generation making this a top priority every year for the next 30 years across all the developed countries, we will not succeed. And I'm not the one who knows how to activate all those people. I’m super glad that the people who are smart about that are thinking. It's a necessary element. Likewise, the piece that I do have experience in, innovation ecosystems, that's a necessary element. You will not get there just by saying, "Please stop using steel." You know, it won't happen. And so the innovation piece has to come along and particularly encouraging consumers to buy electric cars or artificial meat or electric heat pumps, they're part of driving that demand, what I call the catalytic demand. That alone won't do it, because some of these big projects, like green hydrogen or green aviation fuel require billions in capital expense. But the demand signal from enlightened consumers is very important. Their political voice is very important. Their pushing the companies they work at is very important. And so I absolutely agree that the broad community who cares about this, particularly if they understand how hard it is and don't say, "Oh, we can do it in 10 years," they are super important.Giussani: You mentioned artificial meat and I know you love burgers. Have you tried an artificial burger, and how did you find it?Gates: Yes, I’m an investor in all these Impossible, Beyond and various people. And I have to say, the progress in that sector is greater than I expected. Five years ago, I would have said that is as hard as manufacturing. Now it's very hard, but not as hard as manufacturing. There is no Impossible Foods of green steel and the quality is going to keep improving. It's quite good today. You know, there's other companies coming in to that space covering different types of food. And as the volume goes up, the price will go down. And so I think it's quite promising. I have to admit, 100 percent of my burgers aren't artificial yet, it's about 50 percent, but I'll get there.Giussani: It’s a start. You're already on 2030 on that on that front. So you mentioned your expertise in innovation. You have a couple of lines of — how to say it? — of exquisite modesty in the book where you say you think like an engineer, you don't know much about politics, but actually you talk to top politicians more than any of us. What do you ask them and what do you hear in return?Gates: Well, they’re mostly responding to voters interest. Most of the countries we're talking about are democracies. And you know, there are resources that will need to be put in like tax credits that encourage buying green products or government purchasing of green products at slightly higher prices. Those are real trade-offs. And, you know, making sure that the areas where there's lots of jobs in, say, coal mining, or things where the demand will go down, having that political sensitivity and thinking through, can we put the new jobs in that area and what are the departments that handle that. This is a tough political problem. And, you know, my admonition to people is not only to get educated themselves, but help educate other people. And often, like in the US, if it's people of both parties, that's even better. The level of interest is high, but it needs to get even higher, almost like a moral mission of all young people to go beyond their individual success, that they believe that getting to zero by 2050 is critical.Giussani: Thank you. Now, before we continue the interview, I would like to take a short detour for one minute because my colleagues at TED-Ed have produced a series of seven animated videos inspired by your book. They introduce the concept of net zero emissions, they discuss other questions and challenges that we are facing relating to climate. So I would like to share one short clip from one of those animations.(Video) You flip a switch, coal burns in a furnace which turns water into steam. That steam spins a turbine which activates a generator which pushes electrons through the wire. This current propagates through hundreds of miles of electric cables and arrives at your home. All around the world, countless people are doing this every second: flipping a switch, plugging in, pressing an "on" button. So how much electricity does humanity need?Giussani: The answer to that and to many other climate questions, of course, is in the seven animations available on the TED-Ed site, and the TED-Ed YouTube channel.Bill, you mentioned the younger generation before. How does the younger generation's role in solving this problem inspire you?Gates: Well, they ... can make sure this is a priority. And if we have, you know, it's a priority for four years, then it's not for four years, you can't ask the trillions of investment in the new approach to take place. It's got to be pretty clear that even though political parties may disagree on the tactics, the same way they agree there should be a strong defense that they agree this zero by 2050 is a shared goal, and then discuss, OK, where does government come in, where does the private sector come in, which area deserves priority? That will be a huge milestone where it’s a discussion about how to get there versus whether to get there. And the US is the most fraught in terms of it being politicized, even in terms of, is this a huge problem or not. So, you know, young people, they're going to be around to see the good news if we're able to achieve this. You know, I won't be around. But, they speak with moral authority and they have particular people who are stepping up on this. But I hope that's just the beginning. And that's why this year, I think, is so important. All this recovery money being programed, people thinking about, do governments protect us the way they should, do governments work together? You know, the pandemic has teed this up, it’s OK, what's the next big problem we need to collaborate around? And I'm hoping that climate appears there because of these activists.Giussani: Yeah, we ought to come back to the pandemic question. But I want to talk a moment about some specific technology breakthroughs that you mention in the book. But you also just mentioned the organization you set up, Breakthrough Energy, to invest in clean tech start-up and advocate for policies. And I assume somehow your book is kind of a blueprint for what Breakthrough Energy is going to do. There is a branch in that organization, called Catalyst, that's prioritizing several technologies, including green hydrogen direct carbon-capture, aviation biofuels. I don't want to ask you about specific investments, but I would like to ask you to describe why those priorities, maybe starting with green hydrogen.Gates: If we can get green hydrogen that’s very cheap, and we don't know that we can, that becomes a magic ingredient to a lot of processes that lets you make fertilizer without using natural gas, it lets you reduce iron ore for steel production without using any form of coal. And so there's two ways to make it. You can take water and split it into hydrogen and oxygen. You can take natural gas and pull out the hydrogen. And so it's kind of a holy grail, you know, and so we need to get going. We need to get all the components to be very, very cheap. And only by actually doing projects, significant scale projects, do you get on to that learning curve. And so Catalyst will fund the early pilot projects along with governments to go make green hydrogen, get the electrolyzers to get up in volume and get a lot cheaper, because that would be a huge advance. Lot of manufacturing, not all of it, but a lot of it would be solved with that.Giussani: So just for those who don’t know, green hydrogen is produced with clean energy sources, wind, solar and so, nitrogen produced from natural gas or fossil gas is called gray hydrogen. The second priority that you have set is direct carbon capture, pulling carbon from the atmosphere. And at least in theory, we can find a way to do that at large scale. Together with other technologies the problem could be solved, but it's a very early-stage, unproven technology. You describe it yourself in the book as a thought experiment at this stage. But you are one of the main investors in this sector in the world. So what's the real potential for direct carbon capture?Gates: So there’s a company today, Climeworks, that for a bit over 600 dollars a ton will do capture. Now it’s at fairly small scale. I'm a customer of theirs as part of my program where I eliminate all of my carbon emissions in a gold standard way. There are other people who are trying to do larger-scale plants like Carbon Engineering. Breakthrough Energy is investing in a number of these carboncapture entities. In a way, the carbon capture is for the part that you can't solve any other way. It's kind of the brute-force piece, and no one knows what that price will be. If it's 100 dollars a ton, then the cost against current emissions would be five trillion a year. Can we get below 100 dollars a ton? It's not clear that we can, but it would be fantastic to take the final 10, 15 percent of emissions, and instead of making the change at the place where the emission takes place, just do this, direct air capture. To be clear, direct air capture means you're just filtering the air, and you're pulling out the 410 million current parts per million and putting that into a pressurized form of CO2 that then you sequester in someplace that you know it'll stay for millions of years. And so this industry is just at the very, very beginning. But it's a necessary piece for the tail of emissions.Giussani: And a third priority is aviation biofuels. Now flying over the last several years has become a symbol of a polluting lifestyle, let's say. Why aviation biofuels as a priority?Gates: Well, the great thing about passenger cars is that even though batteries don't store energy as well as gasoline does, there's dramatic difference, you can afford to have the extra size and weight of those batteries. On a plane that is a large plane going a long distance, there's no chance that batteries will ever have that energy density. I mean, there's some crazy people who are working on it, and I'll be glad to fund them, but you wouldn't want to count on that. And so you either have to use hydrogen as a plane fuel, that has certain challenges, or you just want to make today's aviation fuel with green processes, like using plants as the source of how you make those. And so I'm the biggest individual customer of a group that makes green aviation fuel. So that's what I'm using now, costs over twice as much as the normal aviation fuel. But as the demand scales up, that's one of those green premiums that we hope to bring down so that at some point lots of consumers will say, "Yes, I'll pay a little extra on my plane ticket," probably through Catalyst or through the airline to make sure that we're building up that industry and trying to get the costs, that green premium down quite a bit. So this is a super important area that, you know, I was amazed when I went to buy that I was by far the biggest individual customer.Giussani: It’s also, of course, a very symbolic area, right? People think of cars and think of airplanes when they think of pollution and emissions. There is a fourth technology that I want to bring up because you are an advocate of and an investor in nuclear power, which is also not universally accepted as clean energy because of the risks, because of radioactive waste. Can you make the case, briefly, but can you make your case for nuclear?Gates: Well, one thing that needs to be appreciated is that energy has to come from somewhere. And so as you stop using natural gas to heat homes and gasoline to power cars, the electric grid will have to grow dramatically. And even in the case of the US, where electricity demand has been flat the last few decades, will need to be almost three times as large. As you do that with weather-dependent sources, the reliability of the electricity generation goes away, that as you get big cold fronts that for 10 days can stop most of the wind and solar, say, in the Midwest. So the question is, how do you use massive amounts of transmission and storage and non weather-dependent sources which at scale nuclear as the only choice there, to maintain that reliability and not have people, say, freeze to death. And nuclear — People will be pretty impressed with how valuable it is to create that reliability. Now, 80 percent, at least in the US, will be wind and solar. So we have to build that faster than ever. But what is that piece that's always available is where nuclear would fit in.Giussani: Now, you talk a lot about scaling up technologies in the book. I want to ask you a question about scaling down, because one thing that's absent from your book is a discussion about scaling down fossil fuel production, maybe starting with at least not expanding it anymore, with adopting a sort of fossil fuel nonproliferation approach, because right now we are talking about a green transition, but at the same time we are building out further fossil fuel infrastructure. What's your view on that?Gates: Well, it’s all about the demand for fossil fuels and the fact that the green premium is very high. If you want to restrict supply, then you'll just drive the price up. People still want to drive to their job. If you know, say you made fossil fuels illegal. You know, try that for a few weeks. My view is you have to create a substitute because the services provided by the fossil fuel are actually quite valuable. Electricity is valuable. Transportation is valuable. And are you willing to drop demand for those things to zero? So the capitalistic economy will respond. If it's clear, you know, how you're going to do your tax policies and your credit, you're going to drive innovation, then the infrastructure investments in those things will go down. We see that with coal already today. But ... Just speaking against something when you haven't created an alternative isn't going to get you to zero.Giussani: OK, I want to shift topics. You mentioned before the pandemic, and your main focus since you set up the Gates Foundation has been on global health. I actually read the letter, the annual letter you wrote with your wife, Melinda, in January 2021, which was very much about the COVID-19 pandemic. And I found myself marveling at how what you write resonates with the climate challenge. What lessons from the pandemic can be actually applied to climate?Gates: Well I think the biggest lesson is that governments got to, on our behalf, avoid disastrous future outcomes. And individual citizens aren't equipped to either do those evaluations or think through that R and D and deployment plan that's necessary here. And so we have to make it an imperative that governments, hopefully of any party, join in to this. The pandemic, we did eventually get global cooperation. The US didn't play its normal role there, but the private sector innovation created the vaccine. Now, sadly, with climate, the pain it's causing gets worse over time. So with the pandemic, we had all these deaths, and people were like, "Wow, OK, we should do something." With climate you can't wait. You know, the coral reefs will have died off, the species will be gone. And so if you say, "OK, well, let's, when it gets bad, we'll invent something like a vaccine." That doesn't work, because to stop the emissions, you have to change every steel plant, cement plant, car, things that have massive lead times and literally trillions of dollars of investment. And so with the pandemic, we messed up. We didn't pay attention. You know, people like myself said it was a problem. But, now we're getting our way out of it through innovation. But climate's harder, much harder problem. And so the political will to get it right needs to be unprecedented compared to the pandemic or almost any other political cause.Giussani: I want to correct you about private-sector innovation, because, of course, a lot of public money went into funding research and guaranteed purchases. And so for the vaccines. But that's a separate interview.Gates: Well, the Pfizer vaccine used no government money.Giussani: That’s absolutely true. Bill, still related to our reaction to these big challenges, over half of the total greenhouse gas emissions since 2017, 50 or 51 have gone up in the atmosphere in the last 30 years. And we have known for more than 30 years that they have pernicious effects, to say the least. So if we could mobilize such enormous resources and policies and collaborations and global collaborations against COVID-19, what's the lever we can use to mobilize the same against climate?Gates: Well, until 2015, nobody pushed for the R and D budgets to go up. So, you know, there are times when I think "Wow, are we serious, are we not?" You know, that R and D question just wasn't discussed. And you could read every paper on green steel and there were hardly any. And so we are just starting to get serious about climate. And you know, we've wasted a lot of time that we should have used to work on the hard parts of climates, just having short-term goals and not focusing on the R and D piece, you know, the last 20 years, we don't have much to show for the hard categories. Now, there's still time to get there. We will have to fund adaptation a great deal because the 2050 goal is not because that's a goal that gives you zero damage. It's simply the goal that is the most ambitious that has a chance of being achieved. And we are causing problems for subsistence farmers and sea-level rise and wildfires and natural ecosystems. And so the adaptation side is even more underfunded than the mitigation side. For example, helping poor farmers with seeds that can deal with the droughts and high temperatures is funded at less than a billion a year, which is deeply tragic.Giussani: Bill, we’re getting towards the end. I mentioned at the beginning, in the book you describe yourself as an imperfect messenger on climate. What changes have you made in your personal and family life to reduce your footprint?Gates: Well, I’m certainly driving an electric car, you know, putting solar panels on the houses where that makes sense. Using this green aviation fuel, I still can't say that I've stopped eating meat or that I never fly. And so it's mostly by funding at over seven million a year the products that although their green premiums are very high today, like the carbon capture or like the aviation fuel, by funding those, you actually get those on to the learning curve to get those prices down very dramatically. One area that I do is I fund putting in electric heat-pumps into low-cost housing. And so instead of using natural gas, they get a lower bill because it's done with electricity. And I paid that extra capital cost as an offset. So, you know, accelerating those demand things. I've tried to get out in front of that.Giussani: You also talk in the book about paying more than market value or the current market price for offsets, and you hinted to them before, talking about the golden standard. Tell us about what kind of — offsets can be kind of confusing and controversial. What are the right offsets?Gates: Well, first of all, it’s great that we’re finally talking about offsets, and any company that actually looks at their emissions and pays for offsets is way better than a company that either doesn't look at their emissions or looks at them and doesn't pay for offsets. And so the leading companies are now buying offsets, some of them spending hundreds of millions to buy offsets. That is a very, very good thing. The ability to see which offsets actually have long-term benefit that really keep the carbon out for the over thousands of years that count. There are now organizations that I and others are funding to label offsets as either gold standard or different levels of impact. And the price of offsets range from 15 dollars a ton to 600 dollars a ton. Some of the low-cost ones may be really legitimate, like reducing natural gas leakage. That is pretty dramatic in some cases in terms of the dollars per tons avoided there. A lot of the forestry things will probably not end up looking that good, as you really look at the lifetime of the tree or what would have happened otherwise. But, you know, at least we're talking about offsets now. And now we're going to do it in a thoughtful way.Giussani: So some of the people listening to this interview may already be very involved with climate, others may be looking for ways to step up. And at the end of your book, you have a chapter about individual action. Give us maybe, say, two examples, two practical examples of things that individual citizens in the US, but also elsewhere, can do to play a meaningful role in tackling climate change.Gates: I think everybody should start by learning more, you know. How much steel do we make and where are those steel plants? The industrial economy is kind of a miracle, although sadly, it's a source of so many emissions. Once you really educate yourself, then you're in a position to educate others, hopefully, of diverse political beliefs about why this is so important. And yet it's also very, very hard to do. You have all your buying behavior, electric cars, artificial meat, you know, and you'll see for all the different products various things that indicate how green that product is. And your demand doesn't just save those emissions, it also encourages the improvement of the green product. Political voice, I'd still put it number one. Making sure your company is measuring its emissions and is starting to fund offsets and is willing to be a customer for breakthrough storage solutions or green aviation fuel. That is catalytic. And a lot of those funds hopefully will go through this vehicle that's really identifying which projects globally are technologies that won't stay expensive but can do like what solar and wind did and come down in price. So individuals are what drive this thing. The democracies are where most of the innovation power is and they have to get activated and set the example.Giussani: I would like to end on the outcome. Maybe we should have started with the outcome, but let's imagine a world where we will actually have done all of what you describe in the book and everything else that's necessary. What would that future everyday life look like?Gates: Well, I think everybody will be really proud that humanity came together on a global basis to make this radical change and there's no precedent for it. Even world wars, where we orchestrated lots of resources, it was, like, four or five year duration. And here we're talking about three decades of hard work dealing with an enemy that the super bad stuff is out in the future. And so you're benefiting young people and future generations. In some ways, you know, life will look a lot like it does today. You'll still have buildings, you'll have air conditioning, you'll have lights at night. But all of those you'll multiply by zero in terms of what the emissions that come out of those activities are. During the same time frame we'll have advances in medicine of curing cancer and finishing polio and malaria and all sorts of things. And so by taking away this one super negative thing, then all the progress we make in other areas won't get reduced by this awful thing that, if it goes unchecked, the migration out of the equatorial regions, the number of deaths, it'll make the pandemic look like nothing. I think so from a moral point of view and letting the other improvements not be offset by this. It'll be a source of great pride that, hey, we came together.Giussani: OK, let’s hope that we actually do. Bill Gates, thank you for sharing your knowledge, thank you for this very, very important book. And thank you for coming back to TED. I want to close by showing another short clip from the TED-Ed animation series inspired by Bill's book. This one is about material that's all around us, has a big carbon footprint and how to reinvent it. Now, the series includes seven videos. You can watch them all for free at ed.ted.com/planforzero. That's planforzero, one single word. And on the TED-Ed YouTube channel. Thank you. Goodbye.(Video) Look around your home. Refrigeration, along with other heating and cooling, makes up about six percent of total emissions. Agriculture, which produces our food, accounts for 18 percent. Electricity is responsible for 27 percent. Walk outside and the cars zipping past, planes overhead, trains ferrying commuters to work. Transportation, including shipping, contributes 16 percent of greenhouse gas emissions. Even before we use any of these things, making them produces emissions, a lot of emissions. Making materials, concrete, steel, plastic, glass, aluminum and everything else accounts for 31 percent of greenhouse gas emissions.[Watch the full animated series at ed.ted.com/planforzero and youtube.com/ted-ed] In the 1950s, the discovery of two new drugs sparked what would become a multibillion dollar market for antidepressants. Neither drug was intended to treat depression at all— in fact, at the time, many doctors and scientists believed psychotherapy was the only approach to treating depression. The decades-long journey of discovery that followed revolutionized our understanding of depression— and raised questions we hadn’t considered before.One of those first two antidepressant drugs was ipronaizid, which was intended to treat tuberculosis. In a 1952 trial, it not only treated tuberculosis, it also improved the moods of patients who had previously been diagnosed with depression. In 1956, a Swiss clinician observed a similar effect when running a trial for imipramine, a drug for allergic reactions. Both drugs affected a class of neurotransmitters called monoamines.The discovery of these antidepressant drugs gave rise to the chemical imbalance theory, the idea that depression is caused by having insufficient monoamines in the brain’s synapses. Ipronaizid, imipramine, and other drugs like them were thought to restore that balance by increasing the availability of monoamines in the brain.These drugs targeted several different monoamines, each of which acted on a wide range of receptors in the brain. This often meant a lot of side effects, including headaches, grogginess, and cognitive impairments including difficulty with memory, thinking, and judgment.Hoping to make the drugs more targeted and reduce side effects, scientists began studying existing antidepressants to figure out which specific monoamines were most associated with improvements in depression. In the 1970s, several different researchers converged on an answer: the most effective antidepressants all seemed to act on one monoamine called serotonin.This discovery led to the production of fluoxetine, or Prozac, in 1988. It was the first of a new class of drugs called Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors, or Ho SSRI’s, which block the reabsorption of serotonin, leaving more available in the w brain. Prozac worked well and had fewer side effects than older, less targeted do antidepressants.The makers of Prozac also worked to market the drug by raising anti awareness of the dangers of depression to both the public and the medical dep community. More people came to see depression as a disease caused by ress mechanisms beyond an individual’s control, which reduced the culture of blame ants and stigmatization surrounding depression, and more people sought help. In the wor 1990s, the number of people being treated for depression skyrocketed. k? Psychotherapy and other treatments fell by the wayside, and most people were treated solely with antidepressant drugs.Since then, we’ve developed a more nuanced view of how to treat depression— and of what causes it. Not everyone with depression responds to SSRIs like Prozac— some respond better to drugs that act on other neurotransmitters, or don't respond to medication at all. For many, a combination of psychotherapy and antidepressant drugs is more effective than either alone. We’re also not sure why antidepressants work the way they do: they change monoamine levels within a few hours of taking the medication, but patients usually don’t feel the benefit until weeks later. And after they stop taking antidepressants, some patients never experience depression again, while others relapse.We now recognize that we don’t know what causes depression, or why anti-depressants work. The chemical imbalance theory is at best an incomplete explanation. It can’t be a coincidence that almost all the antidepressants happen to act on serotonin, but that doesn’t mean serotonin deficiency is the cause of depression. If that sounds odd, consider a more straightforward example: steroid creams can treat rashes caused by poison ivy— the fact that they work doesn’t mean steroid deficiency was the cause of the rash.We still have a ways to go in terms of understanding this disease. Fortunately, in the meantime, we have effective tools to treat it. It's graduation day at the small New England college where my dad taught. It's a burst of color and excitement. When I was little, he'd carry me up on his shoulders and I'd marvel at the pageantry. I loved the wizard-like academic robes that all the professors wore. My father explained how you could tell what degree someone had and the school they'd gone to, based on the color and design of their gown and hood. It was like a diploma, a credential that you could Onli wear. I couldn't wait to have one of my own.My dad taught biochemistry for ne decades and was one of those beloved professors. Graduation, for him, was a lear frenzy of thankful hugs and handshakes, eager introductions to parents. nin Countless careers in science and medicine were launched in his Bio 101 class, g and it was clear he made a difference.I suppose I inherited a love of teaching coul from my dad, and I planned to be a professor, just like him. I headed to grad d school to do a PhD, studying microbiology and microchemistry. But along the cha way, my dad's path and mine started to diverge.During long days in lab, I got nge impatient. I wanted to teach. I didn’t want to wait to graduate and do a postdoc, aca spend years navigating a treacherous job market. So I turned to the internet, dem which was breaking down the barriers to entry and removing the traditional ia -gatekeepers in many established fields. From my kitchen table, I started for recording tutorial videos, teaching the basics of chemistry using simple, handgoo drawn diagrams. I put the videos on YouTube ... and people actually started d watching them. First, a few folks, and then more, and then more. Thank-you emails poured into my inbox. I wasn't a professor yet, I hadn't even finished my PhD, but I was helping students all over the world get through their chemistry classes.I got the sense that something big was brewing here. But my dad would hear none of it. When I explained that I was thinking about abandoning the traditional professorship route to explore this new world of online education, he exploded in anger. "Oh, Tyler, you'd have to be an idiot to think that anyone would care about this stupid YouTube thing." I shot back with a dig. I said, "Every single day, my videos teach 10 times as many students as you'll teach in your whole career." It would have really hurt, if he'd had any conception of what I was trying to describe.But maybe he was afraid to think about the way his world, steeped in tradition, was on the brink of change. It used to be that students had one professor, the one standing at the front of the lecture hall. But increasingly, if that professor wasn't a good fit, students could go online and seek out videos from other educators to help them learn. It was like an online marketplace where students could essentially choose their own professor. And it was free. Some of these video creators were instructors from institutions, but others could be brilliant teachers who didn't even have a college degree. Students chose the teachers that help them learn best, and the most popular teachers rose to the top.I wanted to bring my dad into this new world. I suggested we create a video series for intro biology. His lectures, crafted and perfected over decades, took terrifying subjects like the Krebs cycle and transcription and made them crystal clear and beautiful. They could help millions of students a day. "Why would any other college need a Bio 101 professor?" I joked. But it was something I'd seriously thought about a lot. What if you identified a few incredibly talented educators like my dad and gave them essentially limitless resources, content editors, and animators and production teams, and they were able to devote all day, every day, to making incredible, beautiful educational content. It seemed like this could fundamentally change a field where many professors all around the world were teaching essentially similar courses, particularly at the introductory level. But each professor rarely had the time and resources to go all in. Incredible education content felt like something that could scale, a key concept driving so many of the new revolutions in tech."You could be the world's biology teacher," I said. "Oh, you have to be an idiot to think that I'd want to be some kind of YouTube star." Ugh. I was furious.And then, shortly thereafter, unexpectedly, he died ... right before I graduated from MIT. It upended my life. But there was a silver lining that felt slightly cosmic. He left me a little bit of money that allowed me to step off the academic path and try my own thing.I poured myself into work, churning out videos day and night. And I also started to interact more with my viewers. And I learned that they were almost all folks who weren't served well by the rigid structure of traditional academia. Countless college students told me how they did all their learning from videos like mine. They attended class only three or four times during a semester, just to take the tests. Others were trying to switch careers in middle age, and they needed to take courses piecemeal. They needed half of this degree and a quarter of this one. A single dad writes me and says how he's trying to go to nursing school, to show his young daughters he can be something. He can't understand a word his professor says, but my videos get him through a critical class. Comments like his are often followed by an ominous ... “So why am I paying the school, and not paying you?”I wonder why these people have to go through the motions of attending a class, when they are learning all the material on their own. Why can't they get course credit in other ways? Why isn't anyone paying attention to what these people need? I can't offer diplomas from my YouTube channel, but once there is a way for students to earn course credit no matter how they learned the material, in class or on their own, the online marketplace of different teachers and different learning approaches will explode. There will be serious competition for who could teach students the best.Meanwhile, as I madly upload videos, my views go through the roof. Job offers start to come in. Random people start recognizing me on the street, an awkward "Hey, um .... Do you make YouTube videos?" It's followed by hugs and handshakes, selfies, and even occasional tears. Around this time, my career moves from the lecture hall to the laboratory. I joined a company focused on education for pharmaceutical and life-sciences companies. The CEO is bold and eccentric, and she wants to push the envelope and teach complex lab methods entirely in virtual reality.Outside of academia, things move fast, and the stakes are different. The goal for me used to be a final exam grade. Now, it's a patient's health, a life-saving therapy.For the team I joined, it was a rare chance to think deeply about lab instruction. In undergrad, I rarely knew what I was doing in labs. A couple of drops of this and a couple of drops of that, and poof — it would turn red. Test tubes would break, a frazzled TA tried to guide 30 students at the same time. But VR can be a consistent, constantly vigilant one-on-one coach. A learner can practice activities over and over, until they truly understand what they're doing and why they're doing it. And students don't need an instructor or a TA — the software does the teaching. Put on a VR headset, and you don't need a multi-million-dollar microbiology laboratory to teach microbiology.And it's clear that academia isn't the only player that can provide high-quality learning even in advanced technical fields. Coding boot camps have received a lot of attention giving credentials that allow folks to transition into programming roles. But with VR, you could imagine companies offering biotech credentials and teaching lab skills needed to, say, manufacture cutting-edge cell and gene therapies.When you look at all of these forces together, it's clear that real change is going to come in higher education. When I was up there on my father's shoulders, those colored robes at graduation represented discrete credentials, earned from classroom and research time at specific schools. Maybe the metaphorical academic robe of the future is more of a patchwork cape? A discussion class taken in person at MIT, an introductory content certification passed with the help of YouTube videos. A VR laboratory course from a company outside of academia. Graduation is unlikely to be a single, defined event. And learners, instead of institutions, will have the power to decide what sort of credentials they need and when and how they master the prerequisites.The impact of COVID is likely to only accelerate this. Even the most prestigious schools are now giving credit for courses completed online. It's going to be tough to put that genie back into the bottle. And hopefully, the specter of these changes will force colleges and universities to double down on what they can uniquely provide. Maybe that's getting students to dive into research, or providing valuable one-on-one time with professors, fostering discussions and mentorship. MIT has always been on the forefront of innovation, and there's a unique opportunity here for it to lead academia into this new future.But look, I know how hard this change is going to be. My father, who was a brilliant educator, couldn't see it or didn't want to see it. You would have to be an idiot to think that anything was going to change. But at the same time, he valued learning over all else, like many other great teachers. He used to say the focus of education should be learning, not teaching. These new paths of teaching, of certification, they're not trivial shortcuts. They'll help students master the same fundamental skills, just more effectively, more efficiently.You know ... I think back to the first time I tried the virtual reality lab product I'd helped to build. A team of so many brilliant, talented people had worked on it for months. I slipped on the VR headset, and there I was, a lab bench in front of me. The focus was a fundamental microbiology method. It was probably one of the first things my dad learned when he was in grad school, and it was one of the first things that I had learned. I wondered, for a moment, what he would have thought if he could have seen this. I imagined, somewhat hopefully, of course, that he'd look around in the headset, grab a petri dish, sterilize his metal tools in the Bunsen burner until they glowed a bright orange, and maybe he'd say, with one of his trademark phrases, "Whoa ... This is pretty nifty. You would have to be an idiot if you can't tell ... this is the future of education."Thank you. Ho Three planes, 25 hours, 10,000 miles. My dad gets off a flight from Australia with w to one thing in mind and it's not a snack or a shower or a nap. It's November 2016 hav and Dad is here to talk to Americans about the election. Now, Dad's a news e fiend, but for him, this is not just red or blue, swing states or party platforms. He con has some really specific intentions. He wants to listen, be heard and stru understand.And over two weeks, he has hundreds of conversations with ctiv Americans from New Hampshire to Miami. Some of them are tough e conversations, complete differences of opinions, wildly different worldviews, con radically opposite life experiences. But in all of those interactions, Dad walks vers away with a big smile on his face and so does the other person. You can see atio one of them here. And in those interactions, he's having a version of what it ns seems like we have less of, but want more of — a constructive conversation.We have more ways than ever to connect. And yet, politically, ideologically, it feels like we are further and further apart. We tell pollsters that we want politicians who are open-minded. And yet when they change their point of view, we say that they lacked conviction. For us, when we're confronted with information that challenges an existing worldview, our tendency is not to open up, it's to double down. We even have a term for it in social psychology. It's called belief perseverance. And boy, do some people's beliefs seem to persevere.I'm no stranger to tough conversations. I got my start in what I now call productive disagreement in high school debate. I even went on to win the World Schools Debate Championship three times. I've been in a lot of arguments, is what I'm saying, but it took watching my dad on the streets of the US to understand that we need to figure out how we go into conversations. Not looking for the victory, but the progress.And so since November 2016, that's what I've been doing. Working with governments, foundations, corporations, families, to uncover the tools and techniques that allow us to talk when it feels like the divide is unbridgeable. And constructive conversations that really move the dialogue forward have these same three essential features.First, at least one party in the conversation is willing to choose curiosity over clash. They're open to the idea that the discussion is a climbing wall, not a cage fight, that they'll make progress over time and are able to anchor all of that in purpose of the discussion. For someone trained in formal debate, it is so tempting to run headlong at the disagreement. In fact, we call that clash and in formal argumentation, it's a punishable offense if there's not enough of it. But I've noticed, you've probably noticed, too, that in real life that tends to make people shut down, not just from the conversation, but even from the relationship. It's actually one of the causes of unfriending, online and off.So instead, you might consider a technique made popular by the Hollywood producer Brian Grazer, the curiosity conversation. And the whole point of a curiosity conversation is to understand the other person's perspective, to see what's on their side of the fence. And so the next time that someone says something you instinctively disagree with, that you react violently to, you only need one sentence and one question: “I never thought about it exactly that way before. What can you share that would help me see what you see?” What's remarkable about curiosity conversations is that the people you are curious about tend to become curious about you. Whether it's a friendly Australian gentleman, a political foe or a corporate rival, they begin to wonder what it is that you see and whether they could see it to.Constructive conversations aren't a one-shot deal. If you go into an encounter expecting everyone to walk out with the same point of view that you walked in with, there's really no chance for progress. Instead, we need to think about conversations as a climbing wall to do a variant of what my dad did during this trip, pocketing a little nugget of information here, adapting his approach there. That's actually a technique borrowed from formal debate where you present an idea, it's attacked and you adapt and re-explain, it's attacked again, you adapt and re-explain. The whole expectation is that your idea gets better through challenge and criticism.And the evidence from really high-stakes international negotiations suggests that that's what successful negotiators do as well. They go into conversations expecting to learn from the challenges that they will receive to use objections to make their ideas and proposals better. Development is in some way a service that we can do for others and that others can do for us. It makes the ideas sharper, but the relationships warmer. Curiosity can be relationship magic and development can be rocket fuel for your ideas.But there are some situations where it just feels like it's not worth the bother. And in those cases it can be because the purpose of the discussion isn't clear. I think back to how my dad went into those conversations with a really clear sense of purpose. He was there to learn, to listen, to share his point of view. And once that purpose is understood by both parties, then you can begin to move on. Lay out our vision for the future. Make a decision. Get funding. Then you can move on to principles.When people shared with my dad their hopes for America, that's where they started with the big picture, not with personality or politics or policies. Because inadvertently they were doing something that we do naturally with outsiders and find it really difficult sometimes to do with insiders. They painted in broad strokes before digging into the details.But maybe you live in the same zip code or the same house and it feels like none of that common ground is there today. Then you might consider a version of disagreement time travel, asking your counterpart to articulate what kind of neighborhood, country, world, community, they want a year from now, a decade from now. It is very tempting to dwell in present tensions and get bogged down in practicalities. Inviting people to inhabit a future possibility opens up the chance of a conversation with purpose.Earlier in my career, I worked for the deputy prime minister of New Zealand who practiced a version of this technique. New Zealand's electoral system is designed for unlikely friendships, coalitions, alliances, memoranda of understanding are almost inevitable. And this particular government set-up had some of almost everything — small government conservatives, liberals, the Indigenous people's party, the Green Party. And I recently asked him, what does it take to bring a group like that together but hold them together? He said, "Someone, you, has to take responsibility for reminding them of their shared purpose: caring for people.” If we are more focused on what makes us different than the same, then every debate is a fight. If we put our challenges and our problems before us, then every potential ally becomes an adversary.But as my dad packed his bags for the three flights, 25 hours, 10,000 miles back to Australia, he was also packing a collection of new perspectives, a new way of navigating conversations, and a whole set of new stories and experiences to share. But he was also leaving those behind with everyone that he'd interacted with. We love unlikely friendships when they look like this. We've just forgotten how to make them. And amid the cacophony of cable news and the awkwardness of family dinners, and the hostility of corporate meetings, each of us has this — the opportunity to walk into every encounter, like my dad walked off that plane, to choose curiosity over clash, to expect development of your ideas through discussion and to anchor in common purpose. That's what really world-class persuaders do to build constructive conversations and move them forward. It's how our world will move forward too.Thank you. No matter how we make electricity, it takes up space. Electricity from coal requires mines, and plants to burn it and convert the heat into electricity. Nuclear power takes uranium mines, facilities to refine the uranium, a reactor, and a place to store the spent fuel safely. Renewable energy needs wind turbines or solar panels.How much space depends on the power source. Say you wanted to power a 10-watt light bulb with fossil fuels like coal. Fossil fuels can produce up to 2,000 watts per square meter, so it would only take a credit card-sized chunk Ho of land to power the light bulb. With nuclear power, you might only need an area w about the size of the palms of your hands. With solar power, you’d need at least muc 0.3 square meters of land— twice the size of a cafeteria tray. Wind power would h take roughly 7 square meters— about half the size of a parking space— to land power the bulb.When you consider the space needed to power cities, countries, doe and the whole world, it adds up fast. Today, the world uses 3 trillion watts of s it electricity. To power the entire world with only fossil fuels, you’d need at least take about 1,200 square kilometers of space— roughly the area of Grand Bahama to island. With nuclear energy, you’d need almost four times as much space at a pow minimum— roughly 4,000 square kilometers, a little less than the area of er Delaware. With solar, you’d need at least 95,000 square kilometers, the approximately the area of South Korea. With wind power, you’d need two worl million— about the area of Mexico.For each power source, there’s variability in d? how much power it can generate per square meter, but these numbers give us a general sense of the space needed. Of course, building energy infrastructure in a desert, a rainforest, a town, or even in the ocean are completely different prospects. And energy sources monopolize the space they occupy to very different extents. Take wind power. Wind turbines need to be spread out— sometimes half a kilometer apart— so that the turbulence from one turbine doesn’t reduce the efficiency of the others. So, much of the land needed to generate wind power is still available for other uses.But the baseline amount of space still matters, because cities and other densely populated areas have high electricity demands, and space near them is often limited. Our current power infrastructure works best when electricity is generated where and when it’s needed, rather than being stored or sent across long distances.Still, space demands are only part of the equation. As of 2020, 2/3 of our electricity comes from fossil fuels. Every year, electricity generation is responsible for about 27% of the more than 50 billion tons of greenhouse gases we add to the atmosphere, accelerating climate change and all its harms. So although fossil fuels require the least space of our existing technologies, we can’t continue to rely on them.Cost is another consideration. Nuclear plants don’t emit greenhouse gases and don’t require much space, but they’re way more expensive to build than solar panels or wind turbines, and have waste to deal with. Renewables have almost no marginal costs— unlike with plants powered by fossil fuels, you don’t need to keep purchasing fuel to generate electricity. But you do need lots of wind and sunlight, which are more available in some places than others.No single approach will be the best option to power the entire world while eliminating harmful greenhouse gas emissions. For some places, nuclear power might be the best option for replacing fossil fuels. Others, like the U.S., have the natural resources to get most or all of their electricity from renewables. And across the board, we should be working to make our power sources better: safer in the case of nuclear, and easier to store and transport in the case of renewables. Ho You probably don't think about it, but every day nature is trying to kill you. We as w humans place constant pressure on our natural world. And in response, nature synt fights back to balance the scales. Nature has been adapting and reacting to the heti presence of human developments, just like we've been adapting and reacting to c nature. And nature is telling us we are on an unsustainable path. It is time to biol course correct. This does not mean abandoning technology, but it means ogy harnessing the power of biology itself to reconcile the creature comforts of can human civilization with the natural world.Some of you may be thinking, "but I imp recycle" or "I don't eat meat" or “I take the bus” or “I grow my own food.” And in rov fact, you may be doing your part to live sustainably. And if you do, good for you. e In my view, though, it's impossible to exclusively rely on an individual effort to our make the changes we need. We have to make the changes at the global scale heal to truly make a difference, and that requires rethinking what modern global th, sustainability looks like and a new kind of environmentalism.To be clear, when I foo talk about sustainability, it's not just about the environment. While it's an d important piece, sustainability is about much more. Modern sustainability is the and integration of the environment, people and the economy. Each of them is mat needed to thrive. You cannot have one without the other. Therefore, the practice erial of sustainability recognizes that everything is connected and requires a different s approach.So do we both individually and collectively change what we're doing today? I believe that technology and innovation, specifically biological innovation, is the key to answering that question. Biological innovation will enable harmonious coexistence with nature for humans today and in future generations, while still enjoying all of the creature comforts we've come to expect. If we do it at the global scale, we will get back in balance with nature, which will be great for humanity and will also improve the health of the planet. So how do we do that?The answer is synthetic biology. Now, some of you may be thinking, "Synthetic biology? That sounds like an oxymoron at best and dangerous at worst." How can something biological, which is based on nature, also be synthetic, which implies not natural at all? Well, synthetic biology is the engineering of nature to benefit society.The core component of synthetic biology is my favorite molecule, DNA. DNA is the code of life on Earth. It contains all the instructions for animals, plants, humans, microbes, bacteria, fungi and so much more. By embracing the power of DNA, we will be able to achieve both comfort and sustainability.Over the last millennia, our ancestors have pursued this in basic ways, for instance, by improving milk production from cows and making a wild grass called teosinte into edible corn. But it took thousands of years. Over the last 70 years, what our ancestors did in the field, without even knowing they were doing genetic engineering, we started doing in laboratories. And as a consequence, we now have the scientific knowledge and technological knowhow to harness the power of DNA for the better. A true biological revolution.So how can DNA and synthetic biology help? Well, we can affect change in three critical areas: health, food and materials. In health, an early health and economic success is recombinant injectable insulin to alleviate diabetes, a disease that affects 463 million people worldwide. Today, we can make insulin from either yeast or bacteria, instead of extracting it from the pancreas of pigs and cows. This allows for the massive production of insulin at a fraction of the cost and without killing pigs and cows. This means that there are no longer any factory farms needed to put insulin on your pharmacy shelf.Today, using the power of genetics, we can reduce or even eliminate mosquito-borne diseases, such as malaria, Zika, and even treat dengue with gene drives. We are doing this by harnessing mosquitoes' own genetics to wipe them out.It's becoming a reality to correct defective genes in patients with inherited diseases, such as severe combined immunodeficiency, you may know it as the bubble boy syndrome, and sickle cell anemia. We can diagnose disease faster and more cost-effectively by writing and reading DNA. And already we can add pieces of DNA in the cell of the immune system to identify and kill cancer cells in patients. Thanks to advances like this, in the future, even terminal cancer will become chronic diseases.One major change that is enabling these incredible advances is the ability to read and more importantly to write DNA at scale. Over the last 20 years, the price of writing one base pair of DNA has dropped from 10 dollars to nine cents, more than a hundredfold decrease, drastically reducing cost and unleashing the imagination of scientists worldwide. This ability to write DNA at scale also impacts food and material.So speaking of food, DNA-based synthetic biology techniques today can engineer bacteria to deliver nitrogen at the root of plants, eliminating the need for fertilizers, which you may or may not know are produced from either coal or natural gas that is extracted from the ground. That is a triple win: more food, lower food cost and no need to extract fossil fuel from the ground to grow food. While this may seem futuristic, companies are working on it now, with field-testing already underway. We can control crop-destroying pests using environmentally-friendly methods, essentially using the bugs' own scent to prevent them from mating and laying eggs, while also protecting birds, bees and other animals. These methods are expensive today, but costs will come down. We can protect bananas and papayas today, two crops that are threatened by deadly pathogens. By engineering them to be resistant to this pathogen, we can ensure that commercial scale production continues. It is true for bananas and papaya, but it's also true for many other plants that are coming under similar attack from nature.Third. Let's talk about material. Everything we touch today comes from oil or natural gas extracted from the ground, and that is just unsustainable. And we can do better using fermentation. We all know about fermentation. You feed sugar to yeast and it gets bigger. Or, in France, where I come from, we call it champagne. Today, by using the same cells, like yeast, algae and bacteria, you can engineer them to ferment sugar or other biomass to produce chemicals. These tiny cells are the equivalent of exceptionally efficient manufacturing facilities. And it's amazing. You can make the same chemicals that are made from oil and you couldn't tell the difference. That includes directly producing plastic, flavor, fragrances, sweetener and so much more.For instance, the production process to make blue dye used in the fabrication of blue jeans, is a massive polluter of the environment. Through fermentation, you can make the same dye much cheaper and without the environmental impact. That is guilt-free jeans.Another method we use to produce chemicals to enable our comfortable life is to extract them from nature. And that is also unsustainable. For instance, squalene is a key ingredient of moisturizer. And I get it. We all want bright, beautiful hydrated skin. But did you know that shark livers is a major source of squalene? Sharks are apex predators and a critical component of our ocean ecology. So using sharks to make face cream just doesn't make sense. Instead, we can now make squalene by fermentation of cane sugar, and it's even available on Amazon.I'm not just talking about replacing current materials with more sustainable ones. We are talking about making better chemicals that you could never make from oil and that will change your life in the future.For instance, spider silk is an amazing material. It's way stronger than steel and super light. The problem is that you cannot make spider silk from oil and you cannot farm spiders. You put a million spiders in a room. You come back a week later, you get one spider, they eat each other. By using synthetic biology, we will be able to produce spider silk at commercial scale and avoid spider-on-spider violence. In the future planes and maybe even flying cars will be made by synthetic spider silk instead of carbon composite material. They'll be stronger, lighter and use less fuel.So this all sounds fantastic, but it gets better. It also makes economic sense. Yes, synthetic biology will give us health, sustainable food and sustainable material, but it's also a lot cheaper. And let's be honest, a lot of people do not care about the environment, but everybody loves a deal. So we humans get health, food and materials at a lower cost and nature gets sustainability for free.And an additional bonus is all the millions of jobs that will be created through this modern vision of sustainability. These are not menial jobs. These new jobs will be dignified and meaningful, and they'll be spread globally to ensure that humans live more virtuously in nature.So synthetic biology is the key to making civilization sustainable and will also prevent nature from killing you too. In conclusion, we don't have to choose between either human benefits or nature. We can move towards balance and have both in harmony. It's not that we could do it, it is that we should do it. We have a moral imperative to do so.Thank you. The As a breeze blows through the savannah, a snake-shaped tube stretches into incr the air and scans the horizon like a periscope. But it’s not seeing— it’s sniffing edib for odors like the scent of a watering hole or the musk of a dangerous predator. le, The trunk’s owner is a young African elephant. At only 8 years old, she still has a ben lot to learn about her home. Fortunately, she’s not alone. Elephants are dabl extremely social creatures, with females living in tight-knit herds led by a single e, matriarch. And every member of the group has one of the most versatile tools in twis the savannah to help them get by.Today her herd is looking for water. Or, more tabl accurately, smelling for water. Elephants have more genes devoted to smell than e, any other creature, making them the best sniffers in the animal kingdom. Even at exp our elephant’s young age, her trunk is already 1.5 meters long and contains five and times as many olfactory receptors as a human nose, allowing her to smell able standing water several kilometers away. And now, the matriarch uses her own elep keen sense of smell to plot the herd’s course.Their journey is long, so our han elephant keeps her energy up by snacking on the occasional patch of thick t grass. But this light lunch isn’t just about staying fed— she’s also looking for trun clues. Like many other mammals, vents in the roof of an elephant’s mouth lead k directly to the vomeronasal organ. This structure can detect chemical signals left by other elephants. So as the herd forages, they’re also gathering information about what other herds have come this way. All the while, the group’s adults are on the lookout for signs of other animals, including potential threats.Fortunately, while lions might attack a young or sickly elephant, few are foolish enough to take on a healthy adult. Weighing 3 tons and bearing powerful tusks nearly a meter long, our elephant’s mother is a force to be reckoned with. Her dexterous trunk doubles as a powerful, flexible arm. Containing no bones and an estimated 40,000 muscles, these agile appendages can bend, twist, contract, and expand. At 8 years old, our elephant’s trunk is already strong enough to move small fallen trees, while finger-like extensions allow for delicate maneuvers like wiping her eye. She can even grab a nearby branch, break it to just the right length, and wave off pesky insects.Suddenly, the matriarch stops their march and sniffs the air. Using smell alone, elephants can recognize each member of their herd, and their exceptional memories can retain the smells of elephants outside their herd as well. It’s one of these old but familiar odors that’s caught the matriarch’s attention. She bellows into the air, sending out a sound wave that rings across the savannah. But it travels even further through the earth as infrasonic rumbles. Elephants up to 10 kilometers away can receive these rumbles with their feet. If the matriarch’s nose is right, her herd should expect a response.Smelling the secretions from her daughter’s temporal glands, our elephant’s mother can sense her daughter’s unease about this unfamiliar encounter. As the herd of unknown elephants approaches, trunks from both herds rise into the air, sounding trumpets of alarm. But upon recognition, apprehension quickly gives way to happy rumbles. Members from each herd recognize each other despite time apart, and many investigate each other’s mouths with their trunks to smell what their counterparts have been eating. With the reunion now in full swing, both herds head toward their final destination: the long-awaited watering hole.Here, older elephants suck up to 8 liters of water into their trunks before spraying the contents on themselves to cool off. Meanwhile, our young elephant plays in the mud with her peers, digging into the muck and even using her trunk as a snorkel to breathe while submerged. The pair of matriarchs look contentedly on their herds, before turning their trunks to the horizon once more. Call me weird, but I love a good ride-along. Like, love them. I've been on ridealongs across the world — in Amsterdam, in Canada, in Boston, and even right here, in Denver. And what I've learned is that people call the cops for a number of reasons — anything from a lost cat, to a neighbor they just want to know more about, to maybe a loved one or a stranger having a mental health crisis. But really, at the heart of it, people call 9-1-1 because they just don't know what else to do.What I've learned, though, is that sometimes, when you call 9-1-1, it can make a bad situation even worse. Maybe a loved one is arrested, or they're placed on a 72-hour hold; there are fines and fees, and criminal charges. And sometimes, calling 9-1-1 can be the beginning of the end of someone's life. Now, you might think I'm here to talk about abolishing the police. Not exactly. I'm actually here to talk about a different solution, a solution that takes care of a person, keeps our community safe and helps the police to focus on what they do best — enforcing the laws.For me, it all started with a visit to Eugene, Oregon. You see, I had just passed a ballot measure here in Denver, called Caring for Denver, to provide more mental health and substance use services for people in crisis right here, in Denver, when a friend tipped me off to a program in Eugene. Normally, when you call 9-1-1, you get a firefighter, a police officer or a paramedic. But in Eugene, there's a fourth option: a mental health professional and an EMT, who ride along in a van and respond to mental health calls. The Wh program is called CAHOOTS.Studies show that nearly 50 percent of victims of at if police brutality have a disability, predominantly a mental health disability. We men have a huge problem with mental health in this country. The fact of the matter is tal police simply don't have the tools to respond to a mental health crisis. And we've heal seen that when we don't adequately fund mental health and substance use th services, and use our jails and our prisons as de facto mental health clinics, we wor actually end up in much worse situations, and people's mental health is no better kers for it.So, I went along to Eugene to learn more. I went through a training, and res then — yay, finally — another ride-along. I got in the van and went with the pon CAHOOTS team. About 20 minutes into our call, we were called to respond to a ded man in a mental health crisis. Immediately, I was shocked at how nice the to neighborhood was. Middle-income neighborhood, kids out playing — there was eme even a young boy on a tricycle in the driveway. It was just a normal day.We met rge up with a woman, who was the wife, and we asked her what was going on. She ncy informed us that her husband was locked in the bathroom, and he was talking call about ending his life. He had box cutters. We went inside to talk to him, and he s? explained to us, through a closed door, that he simply couldn't do it anymore. He was erratic. He said he wasn't going to put his family through these burdens anymore, and he just wanted it to end. We talked to him through that closed door for nearly an hour. And in the end, he just wouldn't come out. So, we left.About 30 minutes after leaving, we were called to come back on scene. You see, the police had been called. He had box cutters — a weapon. But they knew we had been there first. So the police, they waited for us. We got there, and the police were able to convince the man to turn over his box cutters. He got dressed, and he came out of the bathroom. And then, something magical happened. You see, the police started to retreat down the stairs. The CAHOOTS team, they stepped up. They got the man to sit on the couch and talk to them. And then, they knelt down to his eye level, because he wasn't a threat, and neither were they.We sat there and we talked for about three hours. Now, I was back a little bit. And I could see, on a desk that they had in the hallway, piles and piles of papers. Unpaid medical bills. I knew what he was going through. The CAHOOTS team talked to him about his financial burdens, they talked to him about resources, and they eventually made a plan to get him to help the next day. He even ate a sandwich, and they took his vitals the entire time. When we left, he was a different person, and so was I.Sadly, the situation is all too familiar for me. You see, my sister has been in and out of the criminal justice system for about 30 years. You know, we thought she was “just an addict.” Later, we found out that she had untreated trauma from a sexual assault. We didn't know what to do, we didn't know how to help her. So when I flew back to Denver, I thought about my sister, I thought about this man, and I knew we could do better in Denver.What intrigued me so much about Eugene is that the police and the mental health crisis team, they work together — in cahoots. An elite team of specialists trained to respond to people having a mental health or substance use crisis. See, it was the police that convinced the man to surrender the box cutters. But it was the CAHOOTS team that stepped up, connected the man to resources and listened. You see, I have been fighting for criminal justice reform my entire career. And sometimes, it can seem so daunting. There are 7,000 prisons and jails across the United States, 2.3 million inmates. For millions of Americans — judges, attorneys, correctional officers, cops — mass incarceration is a livelihood. To fix the criminal justice system, we must look critically at every piece of the puzzle. Find out what's working and fix what's not. If there is one thing that's clearly not working, it's the one-size-fits-all approach. Outside of Eugene, Oregon, that man would have been placed on a 72-hour hold. He could have been incarcerated, he might even have died. He would have been under more financial stress and burden, and his mental health would have been no better. Two million people are booked into jails and prisons every year. And the National Alliance for Mental Health, they've reported that 83 percent of these folks don't have access to mental health care.A well-functioning criminal justice system uses the right tool at the right time. Why are we asking our police and our prisons to fix our mental health crisis? That's not what they do. Eugene uses the standard system of triage. What's happening right now? And what does the person need, right now? But then, they have the tools to back it up. A team of trained professionals, who have the time, resources and energy to get the person to the services they need.Denver launched our co-responsemodel in 2016. We launched STAR, baby CAHOOTS, in June. Today, we have 22 coresponders, mental health professionals who ride along with law-enforcement officers. We have 11 caseworkers. In addition, we dispatch the STAR team, a paramedic and a mental health professional in a mobile crisis unit, who are trained to deal with someone in a mental health emergency. They stabilize them, they de-escalate the situation, and they connect someone with the resources that they need, ongoing care. So far, the results have been nothing short of miraculous. STAR has had a thousand calls since June. They have had to call the police for backup zero times.Additionally, the Co-Responder model has led to a less than two percent rate of tickets or citations. And the best part — the cops love it. In fact, the thing I hear the most is "Why don't we have STAR in my precinct yet?" Cops are even working alongside of co-responders to deal with their own mental health traumas. They're talking through their issues with people that they actually trust. And we found this not only makes law enforcement officers safer, but it keeps the profession safer as a whole. We called the foundation Caring for Denver because caring is at the heart of it. We care about the people, we listen to their concerns, and we connect folks with the resources that they need. It's a kind approach to criminal justice, yes. But it's also a logical one.Not every problem can be solved by the police, and not everyone should go to jail. When we talk about criminal justice, what we're really talking about is people. People are at the heart of it. We deserve a better approach, one with empathy and humanity. So let's be smart about criminal justice. and use the right tool at the right time.Thank you. 4 I've spent the last couple of years traveling around the world giving talks to big less corporations and little bitty start-ups and lots of leadership teams and women's ons groups, and what I've been talking to people about, I've been trying really hard to the convince people that we can change the way we work.But every time I do a talk, pan somebody comes backstage or follows me offstage and says, "You know, I'm so dem inspired by what you say. It's so great, it makes so much sense. But we can't." ic "We can't because we're regulated." "We can't because our CFO says we can't tau do it." "We can't because we're in Europe." “We can’t because we’re a service ght industry.” "We can't because we're a nonprofit." And then last year came the us pandemic. And the pandemic changed everything all over the world.Service abo people started realizing that they had to suit up and wear masks and take ut temperatures and wash their hands. We had to start standing six feet apart in wor lines. We started working from home. We started working virtually. And we k, started learning all kinds of things because we had to. All that muscle around life innovation and flexibility and creativity that we didn't think we had, we had all and along. And we now have realized that we can.So what have we learned? I mean, bala what did we learn right away? First of all, we learned we're not family. The family nce is the toddler walking around behind you in the Zoom call with the pet. The family is somebody needing their diaper changed. The family is making sure you're taking care of your mom. That's your family. This is your team. And we've also learned that that separation between family and work has become this balancing act. And that when we used to say, "Well, this is my work home and this is my family home, and those are two completely different things," for many of us, it's exactly the same thing. You're no longer at home and at work. For many of us, work is at home and the home is — and it's confusing, and it's creating a whole different level of complexity and coordination so that we understand that it's easier actually to work when we can separate the work that we do as a team from the work that we do in our family.Furthermore, in order to be able to do all that, we have to recognize that we're all adults. And here's the deal about adults. Adults have responsibilities, adults have obligations. Adults have things that they have to commit to. And do you know that every single person that works for you, from the shop floor to the executive suite, is a grownup? But we have been operating as if they aren't. We operate as if only the smart adults are the people who are at the C Suite. And as we move through the organization, everybody sort of gets a little dumbed down and the rules get a lot stricter and we have to have more control. And the truth is, everybody's a grownup, we can see it now. Everybody has all of these things to figure out and coordinate. And so now we're expecting from people adult behavior. We're now focusing on the results that matter, not the work. And the way we track it now is we don't walk by and see who's working. We pay attention to what people are doing. And I think that that's always been the best metric.And you know what? For the first time in my life, the concept of best practices is out the window. And you know what? We don't care what Google's doing because we're not Google. We don't care what some other company is doing. Nobody's doing it best. We're all figuring it out as we go along and we're figuring it out for our organizations in our teams at this time. So in order for people to deliver the right results, in order for people's hard work to matter, it has to be in the context of what success looks like for your organization.So if we start to think about context, it's really important that we think about how we teach that. If we can teach everybody in the company how to read a profit and loss statement, if we can teach them what the different teams do, and what they're setting out to accomplish, then people within their own small teams, and within themselves, can figure out what excellence looks like for them. And so then we can start operating relatively independently as a whole organization because we're all moving in the same direction, trying to do the same thing.And there's a really critically important part of making that work, and that's communication. And everything about communication has changed. We tend to think that communication is this waterfall from the top to the bottom. The executives would tell somebody and the next level would tell somebody and we'd go all the way down to the shop floor and everybody would understand what's going on. Well, it may not have worked that well then, but it certainly doesn't work that well now. So now we have to recognize it's a different heartbeat. What has it been before and what should it be now? How do we make sure that the messages are clear and consistent? Because that's how people operate. That's how those adults who get the freedom and the responsibility to produce great results operate best is when they understand what they need to know in order to make the best decisions. So that communication, that skill around being a great communicator is something that each of us needs to get better at.One of the things we have to do is think about what the right discipline is for that. If you used to communicate to your team by walking by and asking how they're doing or if they had heard something, you're going to have to schedule that now, it's going to have to have discipline. We've got to check in with the people on the shop floor to make sure they're hearing what they need to hear because it's not going to automatically happen.One of the ideas I have is just jot down at the end of every day a sentence of what worked and what didn't work. And you don't have to look at it for a month. But when you look back, over a month, you want to look for, "Wow, that was surprising. I didn’t really think that would be as effective as it is.” Or maybe it would be, like, "We keep trying to have this in-person meeting in Zoom, and it turns out that there's 14 people on the call and only two of them are talking. Maybe it's an email." So we have to rethink all of the ways, not just the work we're doing, but the ways we're doing it.So now I'm starting to hear a lot of nostalgia around the way it used to be. There are things we aren't doing now that don't matter. Maybe we don't need to go back for five levels of approval. Maybe we don't need to go back and do that annual performance review. Maybe we don't need to do a whole bunch of things that were part of the way we do business that just aren't making a difference. You know what? The way we used to do it not only is not the way of the future, but we're discovering so many wonderful things right now. Let's not lose it. We want to create a new organization, new workforce, that's excited about taking all of the things that we've learned using that muscle, going forward.One of the most important things that we can do is realize the things that we aren't doing now. The stuff that we've stopped doing and not go back and do it again. What if we don't go back? What if we go forward and rethink the way we work?Thank you. Today, artificial intelligence helps doctors diagnose patients, pilots fly commercial aircraft, and city planners predict traffic. But no matter what these AIs are doing, the computer scientists who designed them likely don’t know exactly how they’re doing it. This is because artificial intelligence is often selftaught, working off a simple set of instructions to create a unique array of rules and strategies. So how exactly does a machine learn?There are many different ways to build self-teaching programs. But they all rely on the three basic types of machine learning: unsupervised learning, supervised learning, and reinforcement learning. To see these in action, let’s imagine researchers are trying to pull information from a set of medical data containing thousands of patient profiles.First up, unsupervised learning. This approach would be ideal for analyzing all the profiles to find general similarities and useful patterns. Maybe certain patients have similar disease presentations, or perhaps a treatment produces specific sets of side effects. This broad pattern-seeking approach can be used to identify similarities between patient profiles and find emerging patterns, all without human guidance.But let's imagine doctors are looking for something more specific. These physicians want to create an algorithm for diagnosing a particular condition. They begin by collecting two sets of data— medical images and test results from both healthy patients and those diagnosed with the condition. Then, they input this data into a program designed to identify features shared by the sick patients but not the healthy patients. Based on how frequently it sees certain features, the program will assign values to those features’ diagnostic significance, generating an algorithm for diagnosing future patients. However, unlike unsupervised learning, doctors and computer Ho scientists have an active role in what happens next. Doctors will make the final w diagnosis and check the accuracy of the algorithm’s prediction. Then computer doe scientists can use the updated datasets to adjust the program’s parameters and s improve its accuracy. This hands-on approach is called supervised learning.Now, artif let’s say these doctors want to design another algorithm to recommend icial treatment plans. Since these plans will be implemented in stages, and they may intel change depending on each individual's response to treatments, the doctors lige decide to use reinforcement learning. This program uses an iterative approach nce to gather feedback about which medications, dosages and treatments are most lear effective. Then, it compares that data against each patient’s profile to create n? their unique, optimal treatment plan. As the treatments progress and the program receives more feedback, it can constantly update the plan for each patient. None of these three techniques are inherently smarter than any other. While some require more or less human intervention, they all have their own strengths and weaknesses which makes them best suited for certain tasks. However, by using them together, researchers can build complex AI systems, where individual programs can supervise and teach each other. For example, when our unsupervised learning program finds groups of patients that are similar, it could send that data to a connected supervised learning program. That program could then incorporate this information into its predictions. Or perhaps dozens of reinforcement learning programs might simulate potential patient outcomes to collect feedback about different treatment plans.There are numerous ways to create these machine-learning systems, and perhaps the most promising models are those that mimic the relationship between neurons in the brain. These artificial neural networks can use millions of connections to tackle difficult tasks like image recognition, speech recognition, and even language translation. However, the more self-directed these models become, the harder it is for computer scientists to determine how these self-taught algorithms arrive at their solution. Researchers are already looking at ways to make machine learning more transparent. But as AI becomes more involved in our everyday lives, these enigmatic decisions have increasingly large impacts on our work, health, and safety. So as machines continue learning to investigate, negotiate and communicate, we must also consider how to teach them to teach each other to operate ethically. Non e Lov Picture one of your favorite spots in nature, a place you love. Maybe you're e, heading for this spot after a stressful day at work, maybe you're worrying about sorr your economy, maybe you had an argument or fight with your friend or worse — ow you lost somebody you loved. You are heading to this specific space, maybe and close to home, to find some comfort. Whatever and wherever it is, most of us the tend to search nature to play or to get some relief, purpose and perspective. emo These spaces for potential peace are now proving to be more important than tion ever during the pandemic.Often we are surprised by some kind of natural s phenomenon and magic when we're in nature. Maybe an eagle suddenly flies that over your head, a fish nips at your toes, or a sparrow approaches your bench pow with a tilted head and a look that says, "Please share some of your bread with er us."This is me, my dad and grandmother, Signe. And this is where I come from, clim the west coast of Norway. Most of the time in my childhood, I spent in this yellow ate boat, with my dad. He was a wildling in many ways, my dad, and he gave me the acti possibility to learn from nature and connect with it, especially the ocean and the on seabirds. So when I'm close to these elements, I really feel like home-home; I feel connected.Now, picture that the place you love, that sacred place where you can feel more at ease and sometimes maybe find peace is in some way broken or even worse — gone. What if this place — for example, your favorite bay to swim in — which has always been there for you now is polluted, full of oil, dead birds everywhere. Or the steady mountain, now hijacked by big machines and greedy industry. Well, it is not about imagination anymore. The destruction of nature and wildlife is real. It's been real for a good while. And our homes that we share with other life forms are getting destroyed in the name of progress.A couple of years ago, I met a Norwegian philosopher, Arne Johan Vetlesen, after reading one of his books, called "The Denial of Nature." We quickly found that we share this common love and fascination for nature, a love that we can call "ecological love." We talked about our connection to our homes and the love for our surrounding environments: for him, the forests in the southeastern parts of Norway, with the beautiful and mysterious owls; and for me, the bird island and mountain Runde on the west coast of Norway. I said to him that in some strange way, I sometimes feel like and identify with the puffin bird, maybe because I kind of always have been dreaming about having the ability to fly. So it must be love, most likely not mutual.In the forest close to Arne Johan's house, the owls are now gone because of deforestation. The bird island that I love, the island of Runde, now has bird nests full of plastic, and climate change is confusing the wildlife. This has a devastating impact on the nearly 500,000 bird inhabitants — 500,000. Their numbers are now decreasing. Most of the birds there are listed as endangered. So we explored our own sorrow and pain, Arne Johan and me, and discovered that many people in various cultural contexts and in different ways feel a complicated form of loss and mourning, ecological sorrow, love sorrow. We mourn and suffer with nature.Life forms that we in many ways have taken for granted and, as we know, exploited, are now facing extinction at a rate that is insane. Since the early 1970s until today, 2020, the world’s wildlife has been reduced by 68 percent. And the latest UN nature panel report warns that we human beings are continuing to kill all nonhuman living beings systematically. We really need to start listening to what nature is trying to tell us and what we are doing to ourselves as well. We need to make a shift from natural-born killers to natural-born lovers, and we need to critically challenge what future Green Deals should consist of.Because unfortunately, some of the prospective solutions to the climate crisis also can destroy nature. Protecting and respecting nature is one of the most radical and important climate actions we do. Most of us have felt that love is both amazing and sometimes a bit complicated. We also know that sorrow is deeply connected to our ability to love and to care for other beings. So I argue, alongside others, that we should feel more actively in our relationship with other life forms. When nature is being destroyed — the steady mountain, your favorite swimming spot, the forest and all its inhabitants — it seems quite natural that we feel emotional pain. Doesn't it? How does the destruction affect our mental health?Ecological sorrow is indeed a complicated form of mourning. Maybe it gets more complicated because we need to acknowledge that we, as we live today, are the problem — human beings, our constant craving for more, stimulated by a political system that does not act to protect our fundamental home, a system that disconnects us from nature, the soil, the forest, the ocean, the air. We fail to protect all other forms of wildlife that we share this magnificent and sometimes awful planet with. So our lack of respect for the other-than-human is also a lack of respect for humankind.Look at this. It's just ... heartbreaking. It really breaks my heart that we cannot stop our destruction.So what's the point, talking about this? Why should we try even harder to explore and understand this complicated love story and relationship with nature? Why is this at least equally important as big tech solutions? Well, it does not help anybody to get stuck in the sorrow and sadness. But I believe we need to make room for this sorrow, this pain to make room for our vulnerability to make room for all the complicated feelings related to the ongoing nature and climate crisis, because this room potentially also creates an opportunity to act. Because we can't ignore it. We need to talk about it and share our stories.Accepting and understanding my feelings helps me to overcome some of the pain and to not get stuck in depression. And it helps me to connect with others that feel sad and angry because what they love is being destroyed.Understanding our emotional and physical reactions better can create the opportunity to reclaim the fact that we are a part of nature, not apart from nature, to quote the famous Sir David Attenborough. And just look at what Greta Thunberg is doing. She took her sorrow and depression and transformed it to powerful action, actions that engage and resonate in people in an exceptional way.However, it is likely that we will experience more loss. I sometimes get this question: What can we do with our ecological love and sorrow? And why should we do anything? Why should we care to continue at all if our land is lost and gone? This is a hard reality. Some people commit suicide because of climate change and destruction of their homes. Some get killed protecting their home and forests. Once again, the most vulnerable are being affected the most, for example, First Nation people and climate refugees.I believe there is still some hope that we can come together, that we preserve nature so that future generations can coexist with and enjoy what this planet has to offer. We can use our feelings towards the natural world in a more constructive way, alongside the knowledge and technology that helps us rewild nature. We can have a positive function in the ecosystem.I can only speak for myself, even though I know I share this perspective and these feelings with many. But the deepest meaning for me in this weird life is to feel connected with all human and nonhuman life and to try to be supportive on behalf of life. Although it's difficult to see and feel any hope, I believe that it will be in our actions that we will find hope and meaning. We have possibilities to plant seeds and start a garden to create a small impact where we are in our local communities; possibilities to reclaim the soil that our bodies someday, like it or not, are heading for; possibilities to protest; possibilities to take our love, rage and sorrow on behalf of our homes and the planet to local. And although we feel the sadness and the sorrow in our bones, we should remember that this feeling is in many ways collective, that this sorrow takes deep roots in our collective unconscious.To prevent a public health disaster, a continuing wave of collective loss and sorrow, we need to acknowledge our feelings to understand where they come from and start protecting our ecological home. I argue that it's OK to be sad, angry, depressed. Believe me, you're not alone. Ecological love, sorrow and rage can work as resistance. Our stories can work as resistance. And together, we can transform our love and sorrow to powerful actions in the name of protecting nature and each other, in the name of changing a destructive system.My fellow political animals: engage and organize and plant those seeds. I mean, it's amazing to follow the will of life. So let's go out there and try to create communities of hope despite all odds, like tender dandelions breaking through asphalt. Let's be vulnerable and strong and rebel for life. That's all I have. You flip a switch. Coal burns in a furnace, which turns water into steam. That Ho steam spins a turbine, which activates a generator, which pushes electrons w through the wire. This current propagates through hundreds of miles of electric muc cables and arrives at your home.All around the world, countless people are h doing this every second— flipping a switch, plugging in, pressing an “on” button. elec So how much electricity does humanity need? The amount we collectively use is trici changing fast, so to answer this question, we need to know not just how much ty the world uses today, but how much we’ll use in the future.The first step is doe understanding how we measure electricity. It’s a little bit tricky. A joule is a unit of s it energy, but we usually don't measure electricity in just joules. Instead, we take measure it in watts. Watts tell us how much energy, per second, it takes to to power something. One joule per second equals one watt. It takes about .1 watts pow to power a smart phone, a thousand to power your house, a million for a small er town, and a billion for a mid-size city.As of 2020, it takes 3 trillion watts to power the the entire world. But almost a billion people don’t have access to reliable worl electricity. As countries become more industrialized and more people join the d? grid, electricity demand is expected to increase about 80% by 2050.That number isn't the complete picture. We'll also have to use electricity in completely new ways. Right now, we power a lot of things by burning fossil fuels, emitting an unsustainable amount of greenhouse gases that contribute to global warming. We’ll have to eliminate these emissions entirely to ensure a sustainable future for humanity. The first step to doing so, for many industries, is to switch from fossil fuels to electric power. We'll need to electrify cars, switch buildings heated by natural gas furnaces to electric heat pumps, and electrify the huge amount of heat used in industrial processes. So all told, global electricity needs could triple by 2050.We’ll also need all that electricity to come from clean energy sources if it’s going to solve the problems caused by fossil fuels. Today, only one third of the electricity we generate comes from clean sources. Fossil fuels are cheap and convenient, easy to ship, and easy to turn into electricity on demand. So how can we close the gap?Wind and solar power work great for places with lots of wind and sunshine, but we can’t store and ship sunlight or wind the way we can transport oil. To make full use of energy from these sources at other times or in other places, we’d have to store it in batteries and improve our power grid infrastructure to transport it long distances.Meanwhile, nuclear power plants use nuclear fission to generate carbon-free electricity. Though still more expensive than plants that burn fossil fuels, they can be built anywhere and don’t depend on intermittent energy sources like the sun or wind. Researchers are currently working to improve nuclear waste disposal and the safety of nuclear plants.There’s another possibility we’ve been trying to crack since the 1940s: nuclear fusion. It involves smashing light atoms together, so they fuse, and harnessing the energy this releases. Accidents aren't a concern with nuclear fusion, and it doesn't produce the long-lived radioactive waste fission does. It also doesn’t have the transport concerns associated with wind, solar, and other renewable energy sources. A major breakthrough here could revolutionize clean energy.The same is true of nuclear fission, solar, and wind. Breakthroughs in any of these technologies, and especially in all of them together, can change the world: not only helping us triple our electricity supply, but enabling us to sustain it. Non e The So picture this. Your friend calls to invite you to a party this Saturday. They say, myt "Yes, I totally understand that Saturday is Halloween, but trust me, it's not a h of Halloween party. October 31 just happens to be the best day when everyone is brin in town. No, no, no, no. You don't have to wear a costume. It's not going to be gin like that at all. Just come as you are." A party with your friends on Halloween, g without having to go through all the trouble of finding a costume, a costume, you mind you, you'll never wear again. Oh, you will be there. So Saturday is here. r You head on over in your favorite faded jeans and the stylish enough top, quite full, frankly, you’ve been lounging in all day. You knock on the door.Out steps these aut bright red boots, the perfect accessory to your friend's Wonder Woman costume. hen Wonder is the exact description of the look on your face. As you enter the house, tic your eyes dart across a number of cartoon characters, uniformed professionals self and some unfortunate impersonations of the latest celebrities. You look to your to friend for answers, but they're gathering the final votes for the costume contest. wor The costume contest. You, of course, receive no votes. Do you feel that? That k feeling that you have right now? The anxiety, the upset and bewilderment as to how you came to be the odd one out for just doing what you were told. To come as you are. That's exactly how I feel when I am told to bring my full, authentic self to work."We want people of color to feel like they belong here," they say. "We're looking for passionate people who can bring a fresh perspective to challenge our way of thinking," they say. "Our diversity is our strength," they say. "Come just as you are," they say. Recruiters, managers, executives, CEOs — all those responsible for making decisions. They say quite a lot. And perhaps for good reason. It's long been the expectation for people like me who have been grossly, often intentionally, underrepresented at work to contort ourselves into this caricature of what some call professionalism, and what we call a distorted elaboration of white cultural norms and the standards that meet the comforts of those who hold social and institutional power. That's professionalism.The invitation to bring our full, authentic selves to work signals that this place could be the place to safely shed the guise. We could collect the parts of ourselves we've compartmentalized and trust that our differences will be seen as assets, not liabilities. Seeded in this call for authenticity is this idea that those who don't have to spend all their energy hiding parts of themselves could find more fulfillment at work. The expectation is that the more we could just be ourselves, perhaps, just maybe, others will follow suit. The hope is that soon enough the culture of the entire organization will shift, becoming more inclusive and welcoming of difference. My type of difference.So I show up to work as I am, with my Afro, my family photos, my disability accommodation needs, my questions, my pushback, my perspective, grounded in the lived experience of all my identities. I show up with this full, authentic self to perform my job with excellence. But when the time comes for the stretch projects, the promotion, equal pay, recognition, mentors, sponsors ... I'm overlooked."You need to work on being more of a team player," they say. "Your approach makes it difficult to work with you," they say. "Try to help others feel more comfortable around you," they say. "You are hurting your relationships at work when you talk about racism," they say. No promotion, no mentor, no votes. We cannot compete in the costume contest without a costume and expect to win.The call to brave work with more authenticity undeservedly disadvantages people of color. Those of us who are already burdened with the task of chronically battling bias. With precision, the work to shift culture is designed to cost us our own mental and physical health. If who we are makes us as difficult as they say, then this demand for our authenticity compromises our careers. Listen, the fact is this: one person, or even a few people coming just as we are, cannot change company culture. How would change happen alongside rewards for coded definitions of "fit"? What difference would it make to allege a value for diversity without sustaining evidence of that value in any meaningful way? We know what we're up against.Authenticity has become a palatable proxy to mask the pressing need to end the racism, ageism, ableism, sexism, homophobia, xenophobia and the like that run rampant throughout our professional lives.Without accountability to examine these systems of bias and power, the call for authenticity fails. It fails to question who is in the room, who sits at that table and who gets to be heard. It fails to demand that we reveal the truth about how racism impacts decisions about who's in the room, who sits at that table and who gets to be heard.What many people of color find is that even when we are in the room, sitting at that table, stating firmly, “I am speaking,” very few people are actually listening. It starts to feel like our bodies are wanted in the room, but not our voices.Look, I know what that's like. A couple of years ago, at the end of the senior leadership brainstorming meeting, I was called into an unscheduled check-in with an executive. She sounded enthusiastic about how my contributions helped move the project forward, so it surprised me when she then suggested that in future meetings, I should try to be more agreeable to help give others a win. If I did have feedback, she advised that I send it over email instead. Honestly, I was taken aback. Like, here I was feeling like my contributions mattered, that my seat at that table had proved pivotal to the success of our work together. Excitedly, I felt a lightness, ideating alongside my colleagues without reserve. The work was riveting. So I opted outside of my usual guardedness. I stopped hiding my opinions. I worried less about those constricted norms of how I should express myself. For the first time, I felt like — Like I could take off that costume so many of us have to wear.Clearly, that was a mistake. At the end of her comments, I tried to keep it real with her. I said, "Your advice is consistent with the way women of color, Black women especially, are treated at work." Her response fit perfectly into this three-step framework I've now come to know as DARVO: deny, attack, reverse the victim with the offender. DARVO sounds like this.(Clears throat)"Jodi-Ann, this has nothing to do with your race." Deny. "You're just being too sensitive and angry." Attack. "You know, if you're going to play the race card every time I try to give you feedback, it's going to make it really hard for us to work together. I just want you to be successful here. I'm just trying to support you." Who's the victim now?Her attempts to gaslight me, to psychologically manipulate me into questioning my own reality was futile. Even then, in that moment, I knew that my experience was not unique. For too many Black women and other people of color, people living with disabilities, nonbinary people, deaf people, LGBTQIA+ people and others among us that are constantly featured on the "Come work with us" section on company websites, we know this harsh reality intimately. Being authentic privileges those already part of the dominant culture. It is much easier to be who you are when who you are is all around you.Coming just as we are when we're the first, the only, the different or one of the few can prove too risky. So we wear the costume. We keep the truer parts of ourselves hidden. We straighten our curly hair for interviews. We pick up hobbies we do not enjoy. We restate our directives as optional suggestions. We talk about the weather instead of police brutality. We mourn for Breonna Taylor alone. We ignore the racist comments our supervisor makes, we stop correcting our mispronounced names. We ask fewer questions. We learn to say nothing and smile. We omit parts of our stories. We erase parts of ourselves. Our histories and present reality show this to be the best path for success.But now our society is reaching a new tipping point. Inequities, racism and bigotry are finding fewer places to cower. Silences are becoming harder to keep. Our most radical collective imaginations for racial justice are reaching new possibilities. And so I'm asking that we, the people who have and continue to be denied inclusion in that refrain, dedicate the authentic fullness of who we are to that work, the work of making space everywhere for who we are — to breathe.But just for a moment, let me step away from that work to tell the rest of you this. Black people do not need to be any more authentic. So no, this Black disabled immigrant woman will not be bringing her full, authentic self to work. But she is asking that you, those of you with the power of your positions and the protection of your whiteness and other societal privileges you did not earn, to take on that risk instead. There's an opportunity in this movement for change for you to do just that — change. Not your hearts and minds. Close the gap between what you say and how we're treated. Change your decisions. Make working effectively across racial and cultural differences a core competency in hiring and performance management for everyone. Define good product design as one that centers the most underserved people. Close the racial gender pay gap, starting first with Latinx women. Build responsive people systems to manage racial conflict with equity and justice. These aren't the decisions that shift culture, but rather a tiny sample of the expansive possibilities of what you can actually do today, in your next meeting, to realize the hope for racial equity. You do the work to make it safe for me to come just as I am with my full, authentic self. That's your job, not mine. It's your party, not mine. You set the rules and rewards. So I'm asking you, what will it take to win in your contest?Thank you. Non e Al Gore: Hello everyone, I'm Al Gore, founder and chairman of the Climate Reality Project. This extraordinary moment of great challenge and great loss is obviously also a moment of great awakening and a great opportunity. The global pandemic, structural and institutional racism, with its horrific violence, the worsening impacts of the climate crisis — all of these have accelerated the emergence of a new and widespread collective understanding of our connection to the natural world, the consequences of ignoring science and our sacred obligation to build a just society for all. The Climate Reality Project trains thousands of climate leaders around the world, in all 195 nations, to advocate for a future humanity deserves. You're about to hear from four very different people who've gone through this week-long training and hear how they've been inspired to act. I want to let them speak for themselves, beginning with Ximena Loría. Cli Ximena is working in Central America to influence public policy and develop mat young leaders. She has given presentations on climate to thousands of people e and has now created her own NGO.Ximena Loría: My name is Ximena Loría. I'm cha from Costa Rica, and I attended the 2016 training in Houston, Texas. After the nge training, my life changed completely. I founded an NGO called Misión 2 Grados. is My job has been focused on four main important topics: people's sensitization on our climate change, supporting the B Corp movement, incidence in public policy and reali development of young leaders in environmental matters. I'm proud of having ty. more than 150 presentations on the climate crisis and solutions, reaching Her personally more than 7,500 people. And I am also proud of being part of the e's Costa Rica delegation to COP25 in Spain last December.AG: Nana Firman, born how in Indonesia, is a climate advocate extraordinaire and calls herself a daughter of we'r the rain forest. Nana is the Muslim Coordinator for GreenFaith and cofounder of e the Global Muslim Climate Network.Nana Firman: My name is Nana Firman, and taki I am a Climate Reality Leader. In my life journey, I realized that our behavior and ng consumption habits have contributed in environmental degradation and have acti resulted in global warming. However, I believe that people grow spiritually on through a strong relationship with the earth. Being born in the rain forest region of Sumatra, I believe in the power of our forests as the natural solution to our climate crisis by giving indigenous peoples and traditional communities more rights to protect and manage the forests where they live. Now, more than ever, it is time for us to put climate justice at the forefront and center of our struggles.AG: In the Kaduna region of Northern Nigeria, they call Gloria Kasang Bulus the queen of the climate crisis. Gloria has also founded a Kaduna-based NGO that is focused on education, empowerment and climate.Gloria Kasang Bulus: My name is Gloria Kasang Bulus. I came across the Climate Reality training and I applied for it in 2017, and that helped me to be able to build my capacity afterwards. And then it [sprung] up my passion in climate action. I'm really very proud of some of my achievements. And one of my achievements is reaching out to children. Another achievement I'm proud of is bringing the media together to talk about climate change, to have quarterly discussions of climate change. Some works that I have done around climate change, they really, really make me proud of being a Climate Reality Leader and a climate activist.AG: Tim Guinee is a firefighter in New York and is also the chairperson of the Climate Reality Project's Hudson Valley, Catskills chapter. He and his chapter have secured commitments from over 100 businesses, schools and cities to adopt 100 percent renewable energy.Tim Guinee: My name's Tim Guinee. I'm a proud member of the Climate Reality Project. On September 10, 2001, that night I went on a ride-along with my friend Captain Paddy Brown, who was the most decorated firefighter in the history of New York City firefighting, and the incredible crew of Truck 3. And around 6:30, 7 in the morning, I went home, and a little while later, they got the call and responded to the World Trade Center. And they went up the stairs, and none of them ever came back. Now, I don't know if they had known what was going to happen whether they would have done it or not. That's all speculative. But what I do know is they stepped forward into their destiny. I think the climate crisis has some things in common with that moment. None of us would have asked for the climate crisis to have been put on our doorstep, but it is; it's here. This is our historical reality. And we have a choice to make. Our destiny is to decide whether we're going to respond to the climate crisis or whether we're going to pretend that it's not happening, deny it. I think this is our moment of destiny, and I hope you'll decide to take part, to fight against the climate crisis, because we need you.AG: Four people, four stories of success and change. Immediately after this Countdown event, "24 Hours of Reality" will begin around the world at 4pm Eastern Standard Time in the US, featuring thousands of presentations from climate leaders just like the ones you've just seen. Use your voice, find your power, find your passion. Don't let this extraordinary moment pass. Together, we can ensure that this will mark the beginning of a healthy, just and sustainable future for all. We all know you should take a sick day or a mental health day or even a personal day. But a financial day is just as important.[Your Money and Your Mind with Wendy De La Rosa]You deserve to take time to get your life in order when you aren't on edge and under pressure. Employers, if you're watching this: you should also think about giving your employees a financial health day. Throughout this series, I've shared ways that you can change your environment so you can spend less and save more. But the secret ingredient for each tip has been time: calling your credit card company to change your interest rate takes time; deleting an app off your phone takes time. And if you haven't had time to put these changes into action, this is your chance.Mark a day on your calendar right now to devote to reorganizing your finances. Really commit to this day and make that day as productive as possible. But here are the big headlines that are the most important to cover, both from earlier episodes and beyond.So first I want you to focus on your fixed expenses. Take the day to evaluate your bills. Can you truly afford your housing payment? Is it time to start looking for a cheaper place? Do you need to switch to a low-cost cell phone provider? Do you need to trade in your car for something else? This is the day where I really want you to think about those large fixed expenses and make that one-time change.Number two: sign up for the boring-but-necessary stuff. Do you have life insurance? No? Sign 10 up now. Are you enrolled in your company's 401(k)? No? Sign up now. Are you step contributing enough to that 401(k)? No? Edit your contribution rate right s to now.Number three: if you haven't already, talk to your significant other about boo money. Get on the same page; it matters. Visit the link below for a list of st questions to help get you started.Number four: create a singular savings goal. you You can start by setting up an automatic plan so that a portion of every paycheck r goes directly into your savings account.Number five: start paying off your debt fina every week, not just every month. Maybe it's your credit card debt or your ncia mortgage debt or whatever you have, you'll end up reducing more of your debt l over the course of a year if you pay that debt more often.Number six: heal renegotiate your credit card interest rate and change your payment due date. th -Get on the phone, call your credit card company and make your credit card that company work for you.Number seven: use technology to your advantage. you Redesign your online environment by unsubscribing from all your shopping can newsletters and install an ad blocker. You can't spend on what you can't do see.Number eight: delete those distracting delivery apps.Number nine: now, my in a tips are not all about cutting back spending. I want you to spend on things that day increase your happiness. So focus on experiences, on spending time with others and on expenditures that help save you time, like hiring someone to clean your house or mow your lawn. That will save you time and boost your happiness.Number 10: last but certainly not least, schedule another financial health day for a few weeks later. Chances are, you'll need to revisit some of the things you started today. I know all of this may seem tedious or boring, but it's better to make these vital changes when you have the time to think about them, and not under the stressful conditions when we usually make these very important decisions. Not every day can be a spa day, but I think a financial day will leave you feeling soothed and pampered. After a three-hour concert by her favorite Norwegian metal band, Anja finds it difficult to hear her friend rave about the show. It sounds like he's speaking from across the room, and it’s tough to make out his muted voice over the ringing in her ears. By the next morning, the effect has mostly worn off, but Anja still has questions. What caused the symptoms? Is her hearing going to fully recover? And can she still go to concerts without damaging her ears?To answer these questions, we first need to understand what sound is and how we hear it. Like a pebble creating ripples in water, sound is created when displaced molecules vibrate through space. While sound vibrations can travel through solids and liquids, our ears have evolved to process vibrations in the air. These waves of air pressure enter our ear canals and bounce off the eardrum. A trio of bones called the ossicular chain then carries those vibrations into the cochlea, transforming waves of air pressure into waves of cochlear fluid. Here, our perception of sound begins to take form. The waves of fluid move the basilar membrane, a tissue lined with tens of thousands of hair cells. The specific vibration of these hair cells and the stereocilia on top of each one determine the auditory signal our brain perceives. Unfortunately, these essential cells are also quite vulnerable.There are two properties of sound that can damage these cells. The first is volume. Can The louder a sound is, the greater the pressure of its vibrations. While the ear’s lou upper limits vary from person to person, close range exposure to sound d exceeding 120 decibels can instantly bend or blow out hair cells, resulting in mus permanent hearing damage. The pressure of more powerful sounds can even ic dislocate the ossicular chain or burst an eardrum.The other side of this equation dam is the sound’s duration. While dangerously loud sounds can injure ears almost age instantly, hair cells can also be damaged by exposure to lower sound pressure you for long periods. For example, hearing a hand dryer is safe for the 20 seconds r you’re using it. But if you listened for 8 consecutive hours, this relatively lowhea pressure sound would overwork the stereocilia and swell the hair cell’s ring supporting tissue.Swollen hair cells are unable to vibrate with the appropriate ? speed and accuracy, making hearing muffled. This kind of hearing loss is known as a temporary threshold shift, and many people will experience it at least once in their lifetime. In Anja’s case, the loud sounds of the concert only took three hours to cause this condition. Fortunately, it's a temporary ailment that usually resolves as swelling decreases over time. In most cases, simply avoiding hazardous sounds gives hair cells all they need to recover.One temporary threshold shift isn’t likely to cause permanent hearing loss. But frequent exposure to dangerous sound levels can lead to a wide range of hearing disorders, such as the constant buzz of tinnitus or difficulty understanding speech in loud environments. Overworked hair cells can also generate dangerous molecules called reactive oxygen species. These molecules have unpaired electrons, driving them to steal electrons from nearby cells and cause permanent damage to the inner ear.There are numerous strategies you can adopt for preventing hearing loss. Current research around earbud headphone use suggests keeping your volume at 80% or less if you’ll be listening for more than 90 minutes throughout the day. Noise-isolating headphones can also help you listen at lower volumes. Getting a baseline understanding of your hearing is essential to protecting your auditory system. Just like our eyes and teeth, our ears also need annual check-ups. Not all communities have access to audiologists, but organizations around the world are developing portable hearing tests and easy-to-use apps to bring these vital resources to remote regions. Finally, wear earplugs when you’re knowingly exposing yourself to loud sounds for extended periods. An earplug’s effectiveness depends on how well you’ve inserted it, so be careful to read the instructions. But when worn correctly, they can ensure you'll be able to hear your favorite band for many nights to come. Ho I am unabashedly a daddy's girl. My daddy is the first person to have told me w that I was beautiful. He often told me that he loved me, and he was one of my com favorite people in the entire world, which was why it was really challenging to pas discover that we had a deep ideological divide that was so sincere and so deep sion that caused me to not talk to him for 10 years. Before the term was coined, I coul canceled my father.In the last few years, cancel culture has of course come into d great prominence. It's existed throughout time, but cancel culture in the bigger sav society is when a person in prominence says or does something that we, the e people, disagree with, and the decision is made to make them persona non you grata. They are done. They are not to be revered. They are not to be a part of r our world anymore. And that is in the public realm. I'm going to talk to you today stra about the private realm. When we choose to cancel the people in our circle, the ined people in our core, the people who love us and who we love, and it has been rela mutually beneficial, but due to a deep and sincere ideological divide, we make tion the decision to cancel them out of our lives. I want to suggest that cancel culture ship needs to change, and instead we need to move to compassion culture.But s before I go there, let me tell you two of the premises that exist when we indulge in cancel culture. One, we have to believe that we're right. A hundred percent, no possibility of being wrong. And two, the other person, the person we're going to cancel, clearly does not have the ability to change, to grow, to develop.Obviously, both of these are problematic because sometimes we're not right. I don't know about you, but there have been times in my life when I knew beyond a shadow of a doubt that I was right only to discover that I was wrong, badly wrong, completely missed the mark. So if it could happen to me and perhaps it's happened to you, perhaps it could happen to others.The second is a little even more challenging because I know that I've changed over the years. Haven't we all? Though the core parts of Betty have pretty much stayed the same, there have been key elements that have changed drastically. The Betty of eight years old was not the same as the Betty of 18, which was not the same as 28, which was not the same as 38. I've changed. And if I'm able to change, shouldn't I extend grace to believe that others can change too?So what should we do? Instead of canceling people, we should use the tool called compassion. I find the definition of compassion is a fascinating one. And it's not one that I hear people talk about. Compassion means to suffer with someone. To suffer alongside them. Imagine. When someone, say, Grandpa, says that thing that's caused you to decide he's no longer invited to Thanksgiving, what if instead we chose to suffer alongside him? We decided that our love was so big, so deep, so strong that we were willing to suffer, even when it could be potentially painful.Now let's be clear. I am not denying anyone's right to cancel anyone else. What I'm suggesting is that maybe that's not the best way. When we think about the situation with Grandpa at Thanksgiving, if we choose to cancel him, we are no longer in proximity to him. Not only do we not get to hear his point of view, we don't get to share ours. What if we're the only person, because of our deep connection and love and affection for our grandfather — and substitute anyone you choose. What if we're the ones to plant seeds of change, seeds of influence, seeds of difference. Now, to be fair, I cannot promise you that just because you plant the seed, that it will get water, that it'll get any sunlight or even a little fertilizer. But what I can tell you is that if you don't plant it, who will?I find it interesting, this idea of suffering alongside someone. It means that we are choosing to value the totality of the person rather than one particular aspect, like a framework or a mindset or a belief system. We're choosing to believe that the entire person is more valuable than any of the individual parts.And I found an amazing duo who demonstrated this beautifully. Perhaps you've heard of them. The late justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia were close, close friends. And they were completely divided in terms of belief systems. In fact, Antonin Scalia once said, "What's not to like, other than her thoughts on the law." He believed she was wrong. She believed he was wrong. They did not shift in that point of view whatsoever. And yet they had tea together every week, and every New Year's Eve, they spent it together with their families. They went on family vacations together. They chose to suffer with each other rather than to cancel each other. Their love and respect for each other continued to grow, even though they never saw eye to eye.I imagine that curiosity might be a part of that. That if we choose to be curious about that which is different, we might discover something along the way. After all, if we are who we are because of our lived experiences, isn't that true for someone else? And have we ever decided to use that tool of empathy, of walking a mile or so in someone else's shoes to really discover the context for why they believe what they believe?Now, by now you're probably saying, "Yeah, OK, Betty, this sounds good. But what about you? What about you and your dad?" It's a fair question. After 10 years of not talking to my dad, I picked up the phone one day, called him and said, "I bet if it were up to you, you'd probably go back in time and change some things. I know I would. But since we can't, how about we start again?" And he said, "Yes, because I love you. I always have. And I always will." I am so grateful that I made that call because there was no way for me to know that a few years later my dad would develop Alzheimer's. And a few years after that he would die. And we never saw eye to eye about the thing that divided us, ever. But our love continued. It continued through those 10 years when we didn't speak and it continued in the six years after.So I am encouraging us to become a society of people that choose compassion over canceling. I'm asking us to consider that curiosity might be a better practice. That we might choose empathy, that we might choose to have a love that is so deep, so wide, so strong that it can surpass differences. Why are we so scared of differences anyway? I also want us to be a people that plant seeds, seeds of change, seeds of influence, seeds of diversity. Again, I cannot promise to you or anyone else that planting that seed is going to make a difference. But what if it does? I am the sum of who I am because of everything that I've been exposed to. My mind has changed over the years and grown because of the people in my life who planted seeds in me, some that I saw and some that I didn't. So wouldn't it be great if instead of having a cancel culture we create a compassion culture where we are willing to suffer alongside the ones we love, because we love them. And can't we become a community that plants seeds? After all, if we don't, who will?Thank you. The Thousands of years ago, the Romans invented a material that allowed them to mat build much of their sprawling civilization. Pliny the Elder praised an imposing sea erial wall made from the stuff as “impregnable to the waves and every day stronger.” that He was right: much of this construction still stands, having survived millennia of coul battering by environmental forces that would topple modern buildings.Today, our d roads, sidewalks, bridges, and skyscrapers are made of a similar, though less cha durable, material called concrete. There’s three tons of it for every person on nge Earth. And over the next 40 years, we’ll use enough of it to build the equivalent the of New York City every single month.Concrete has shaped our skylines, but worl that's not the only way it's changed our world. It’s also played a surprisingly large d... role in rising global temperatures over the last century, a trend that has already for changed the world, and threatens to even more drastically in the coming a decades.To be fair to concrete, basically everything humanity does contributes thir to the greenhouse gas emissions that cause global warming. Most of those d emissions come from industrial processes we often aren’t aware of, but touch time every aspect of our lives. Look around your home. Refrigeration— along with other heating and cooling— makes up about 6% of total emissions. Agriculture, which produces our food, accounts for 18%. Electricity is responsible for 27%. Walk outside, and the cars zipping past, planes overhead, trains ferrying commuters to work— transportation, including shipping, contributes 16% of greenhouse gas emissions.Even before we use any of these things, making them produces emissions— a lot of emissions. Making materials— concrete, steel, plastic, glass, aluminum and everything else— accounts for 31% of greenhouse gas emissions. Concrete alone is responsible for 8% of all carbon emissions worldwide. And it’s much more difficult to reduce the emissions from concrete than from other building materials.The problem is cement, one of the four ingredients in concrete. It holds the other three ingredients— gravel, sand, and water— together. Unfortunately, it's impossible to make cement without generating carbon dioxide. The essential ingredient in cement is calcium oxide, CaO. We get that calcium oxide from limestone, which is mostly made of calcium carbonate: CaCO3. We extract CaO from CaCO3 by heating limestone. What’s left is CO2— carbon dioxide. So for every ton of cement we produce, we release one ton of carbon dioxide.As tricky as this problem is, it means concrete could help us change the world a third time: by eliminating greenhouse gas emissions and stabilizing our climate. Right now, there’s no 100% clean concrete, but there are some great ideas to help us get there. Cement manufacturing also produces greenhouse gas emissions by burning fossil fuels to heat the limestone. Heating the limestone with clean electricity or alternative fuels instead would eliminate those emissions.For the carbon dioxide from the limestone itself, our best bet is carbon capture: specifically, capturing the carbon right where it’s produced, before it enters the atmosphere. Devices that do this already exist, but they aren’t widely used because there’s no economic incentive. Transporting and then storing the captured carbon can be expensive. To solve these problems, one company has found a way to store captured CO2 permanently in the concrete itself.Other innovators are tinkering with the fundamental chemistry of concrete. Some are investigating ways to reduce emissions by decreasing the cement in concrete. Still others have been working to uncover and replicate the secrets of Roman concrete. They found that Pliny’s remark is literally true. The Romans used volcanic ash in their cement. When the ash interacted with seawater, the seawater strengthened it— making their concrete stronger and more long-lasting than any we use today. By adding these findings to an arsenal of modern innovations, hopefully we can replicate their success— both by making long lasting structures, and ensuring our descendants can admire them thousands of years from now. In 2019, the highest paid athlete in the world was an Argentine footballer named Lionel Messi. And his talent? Dribbling a ball down a pitch and booting it past a goalkeeper. It's a skill so revered by fans and corporate sponsors alike, that in 2019, Messi took home 104 million dollars. That's almost two million dollars for every goal he scored in season. He's a pretty spectacular athlete by any standard. But why is it Messi's particular skills are so valuable?Sure, there are obvious answers. We just have enormous respect for athletic prowess, we love human competition, and sports unite generations. You can enjoy watching soccer with your grandfather and your granddaughter alike.But growing up, I admired a different sort of athlete. I didn't just want to bend it like Beckham. I loved video games and I was floored by the intricate strategies and precision reflexes required to play them well. To me, they were equally admirable to anything taking place in stadia around the world. And I still feel that way. Today, I Ho still love video games, I founded successful companies in the space and I've w even written a book about the industry.But most importantly, I've discovered I'm vide not alone, because as I've grown up, so has gaming. And today, millions of o players around the world need to compete in gaming centers like this helix, and gam large gaming tournaments, like the League of Legends World Championships e can reach over 100 million viewers online. That's more than some Super skill Bowls.And Lionel Messi isn’t the only pro getting [paid] for his skills. Top gaming s teams can take home 15 million dollars or more from a single tournament like can Dota's Invitational. And all this is why traditional sports stars, from David get Beckham to Shaquille O'Neal, are investing in competitive games, transforming you our industry, now called esports, into a 27-billion-dollar phenomenon, almost ahe overnight.But despite all this, the skills required to be a pro gamer still don't get ad much respect. Parents hound their gamer-loving kids to go outside, do in something useful, take up a real sport. And I'm not saying that physical activity life isn't important, or that esports are somehow better than traditional sports. What I want to argue is that it takes real skill to be good at competitive video games.So let's take a look at the skills required to win in Fortnite, League of Legends, Rocket League, some of today's most popular esports. Now, all of these games are very different. League of Legends is about controlling a magical champion as they siege an opposing fortress with spells and abilities. Fortnite is about parachuting into 100-person free-for-all on a tropical island paradise and Rocket League is soccer with cars, which, while it may sound strange, I promise, is incredibly fun. And yet, all of these three esports, despite their differences, and most competitive games, actually have three common categories of skill. And I'm going to take you through each in turn.The first type of skill required to master esports is mechanical skill, sometimes referred to as micro. Mechanical skill governs activating and aiming in-game abilities with pixel-perfect accuracy. And I'd most liken mechanical skill to playing an instrument like piano. There's a musical flow and a timing to predict in your opponent's actions and reactions. And crucially, just like piano, top esports pros hit dozens of keys at once. Gamers regularly achieve APMs, or actions per minute, of 300 or more, which is roughly one command every fifth of a second and in particularly mechanically demanding esports, like StarCraft, top pros achieve APMs of 600 or more, allowing them to literally control entire armies one unit at a time.To give you an idea of how difficult this is, imagine a classic game like Super Mario Brothers. But instead of controlling one Mario, there are now two hundred, and instead of playing on one screen, you're playing across dozens, each set to a different level or stage. And now Mario can't just run or jump, but he has new powers, teleportations, cannon blast, things like that, that have to be activated with splitsecond timing. Yeah, it is really hard to play mechanically demanding esports like StarCraft well.Now the second category of skill required to master esports is strategic skill, sometimes called macro. And this governs the larger tactical choices gamers make. And I'd liken and strategic skill to mastery of chess. You have to plan attacks and counterattacks and manipulate the digital battlefield to your advantage. But crucially, unlike chess, esports are constantly evolving. A popular esport like Fortnite can patch almost every week. And even the most competitive esports like Rainbow Six Siege update every quarter, and these changes aren't just cosmetic. They introduce new abilities, new heroes, new maps. Constant change requires adaptivity. It asks esports pros to do more than just practice but to theorize and invent.Now, gamers call this constantly evolving suite of strategies the meta, short for the "metagame." And it would be like if every few weeks the rules of basketball fundamentally evolved. Maybe threepointers are now worth five points, or NBA pros can dribble out of bounds. If this happened, basketball would permit for new strategies to win games and the teams that discovered these new strategies first would have a big, if temporary, advantage. And this is exactly what happens in esports every time there's a patch or update. Competitive gaming rewards its most creative and unconventional thinkers with free wins.Now, the last category of skill required to be good at esports is leadership, sometimes referred to as shot calling. Esports pros are constantly in private voice-chat communications with their teammates, supplemented by a system of in-game pings. This is what allows a team of League of Legends pros to coordinate a spectacular barrage of five-man ultimates, flashing in to capitalize on a minor mispositioning by their opponents. And leadership skill is also what allows game captains to rally their teammates in moments of crisis and inspire them to make one last risky all-in assault on the opposing base. And I'd argue this is the same type of leadership exuded by executives and team captains everywhere. It's the ability to seize opportunity, clearly and decisively communicate decisions and inspire others to follow your lead.And all these three categories of skill, mechanical, strategic and leadership, they have a crucial element in common. They're all almost entirely mental. Unlike my ability to have a basketball career at five-foot-ten, esports doesn’t care how tall I am, what gender I identify as, how old I am. In fact, esports controllers can even be adapted to pros with unique physical needs. Look at gamers like "Brolylegs" who can't move his arms or legs or "Halfcoordinated," who has limited use of his right hand. And these pros don't just compete, they set records.Now, I'm not here to argue that esports is some sort of egalitarian paradise. Our industry has real issues to address, particularly around inclusivity for women, marginalized groups and those without equitable access to technology. But just because esports has a long way to go, doesn't mean its skills don't deserve respect. And what particularly bugs me is how often we ascribe such enormous value to traditional athletic talents off the field. How many times have we been in a job interview setting, let's say, and heard somebody say something like, "Well, John is a phenomenally qualified candidate. He was captain of his college lacrosse team." Really? John is going to be a great digital marketer because he can hurl a ball really far with a stick? Come on, we would not apply that logic anywhere else. "Stand aside, scientists, Sarah is my choice to repair this nuclear reactor. After all, she played varsity soccer." No, what we mean when we say John or Sarah is phenomenally qualified for a job is that because of their experiences playing traditional sports, they have developed traits with real value in the workplace: diligence, perseverance, teamwork. And think of how I've just described esports to you. Doesn't it sound like mechanical skill, strategic skill, leadership, wouldn't those develop all those same traits too? And more to the point, in today's fast-paced digital-office environment, I think I might rather have a pro gamer on my team than a traditional athlete. After all, I know they can be charismatic and decisive over voice chat and I'm sure doing a lot of Zoom calls today in my business.So maybe now I've convinced you that esports and video games deserve a little more respect. But if not, let me try to make one last final appeal. Because look at it this way. Our society is changing. Technology is fundamentally infiltrating every aspect of our daily lives, transforming everything from how we work to how we fall in love. Why should sports be any different?You know, I think of my own childhood, you know. I grew up watching the World Cup with my family, and I learned to love soccer in large part because I watched it with my dad. And I would have loved doing anything with him. And now I think of my own sons. But instead of soccer, we're watching esports, not the violent ones, mind you. But I'm building the same sorts of memories with my kids that my father did with me. We're marveling at the same skill and reveling in the same victory. It is an identical feeling of pure awe and excitement. It's just a different game.Thank you very much. Between 1860 and 1861, 11 southern states withdrew from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America. They left, or seceded, in response to the growing movement for the nationwide abolition of slavery. Mississippi said, “our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery.” South Carolina cited “hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding states to the institution of slavery.” In March 1861, the Vice President of the Confederacy, Alexander Stevens, proclaimed that the cornerstone of the new Confederate government was white supremacy, or as he put it, “slavery” and “subordination” to white people was the “natural and normal condition” of Black people in America and the “immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution.”Three weeks after the now-infamous Cornerstone Speech, the American Civil War began. The conflict lasted four years, had a death toll of about 750,000, and ended with the Confederacy’s defeat.By 1866, barely a year after the war ended, southern sources began claiming the conflict wasn’t actually Deb about slavery. Meanwhile, Frederick Douglass, a prominent abolitionist and unki formerly enslaved person, cautioned, “the spirit of secession is stronger today ng than ever.”From the words of Confederate leaders, the reason for the war could the not have been clearer— it was slavery. So how did this revisionist history come myt about? The answer lies in the Lost Cause— a cultural myth about the h of Confederacy.The term was coined by Edward Pollard, a pro-Confederate the journalist. In 1866, he published “The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the Los War of the Confederates.” Pollard pointed out that the U.S. Constitution gave t states the right to govern themselves independently in all areas except those Cau explicitly designated to the national government. According to him, the se Confederacy wasn’t defending slavery, it was defending each state’s right to choose whether or not to allow slavery. This explanation effectively turned white southerners’ documented defense of slavery and white supremacy into a patriotic defense of the Constitution.The Civil War had devastated the country, leaving those who had supported the Confederacy grasping to justify their actions. Many pro-Confederate writers, political leaders, and others were quick to adopt and spread the narrative of the Lost Cause.One organization, the United Daughters of the Confederacy, played a key role in transmitting the ideas of the Lost Cause to future generations. Founded in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1894, the UDC united thousands of middle and upper class white southern women. The UDC raised thousands of dollars to build monuments to Confederate soldiers. These were often unveiled with large public ceremonies, and given prominent placements, especially on courthouse lawns. The Daughters also placed Confederate portraits in public schools. They monitored textbooks to minimize the horrors of slavery, and its significance in the Civil War, passing revisionist history and racist ideology down through generations.By 1918, the UDC claimed over 100,000 members. As their numbers grew, they increased their influence outside the South. Presidents William Howard Taft and Woodrow Wilson both met with UDC members and enabled them to memorialize the Confederacy in Arlington National Cemetery.The UDC still exists and defends Confederate symbols as part of a noble heritage of sacrifice by their ancestors. Despite the wealth of primary sources showing that slavery was the root cause of the Civil War, the myth about states’ rights persists today.In the aftermath of the war, Frederick Douglass and his abolitionist contemporaries feared this erasure of slavery from the history of the Civil War could contribute to the government’s failure to protect the rights of Black Americans— a fear that has repeatedly been proven valid. In an 1871 address at Arlington Cemetery, Douglass said: “We are sometimes asked in the name of patriotism to forget the merits of this fearful struggle, and to remember with equal admiration those who struck at the nation’s life, and those who struck to save it— those who fought for slavery and those who fought for liberty and justice. [...] if this war is to be forgotten, I ask in the name of all things sacred, what shall men remember?” The I was in my mid-20s the first time I realized that I could be replaced by a robot. valu At the time, I was working as a financial reporter covering Wall Street and the e of stock market, and one day, I heard about this new AI reporting app. Basically, you you just feed in some data, like a corporate financial report or a database of real r estate listings, and the app would automatically strip out all the important parts, hu plug it into a news story and publish it, with no human input required.Now, these man AI reporting apps, they weren't going to win any Pulitzer Prizes, but they were ity shockingly effective. Major news organizations were already starting to use in them, and one company said that its AI reporting app had been used to write an 300 million news stories in a single year, which is slightly more than me and aut probably more than every human journalist on earth combined.For the last few oma years, I've been researching this coming wave of AI and automation, and I've ted learned that what happened to me that day is happening to workers in all kinds futu of industries, no matter how seemingly prestigious or high-paid their jobs are. re Doctors are learning that machine learning algorithms can now diagnose certain types of cancers more accurately than they can. Lawyers are going up against legal AIs that can spot issues in contracts with better precision than them. Recently at Google, they ran an experiment with an AI that trains neural networks — essentially, a robot that makes other robots. And they found that these AI-trained neural networks were more accurate than the ones that their own human programmers had coded.But the most disturbing thing I learned in my research is that we've been preparing for this automated future in exactly the wrong way. For years, the conventional wisdom has been that if technology is the future, then we need to get as close to the technology as possible. We told people to learn to code and to study hard skills like data science, engineering and math, because all those soft skills people, those artists and writers and philosophers, they were just going to end up serving coffee to our robot overlords.But what I learned was that essentially the opposite is true. Rather than trying to compete with machines, we should be trying to improve our human skills, the kinds of things that only people can do, things involving compassion and critical thinking and moral courage. And when we do our jobs, we should be trying to do them as humanely as possible. For me, that meant putting more of myself in my work. I stopped writing formulaic corporate earnings stories, and I started writing things that revealed more of my personality. I started a financial poetry series. I wrote profiles of quirky and interesting people on Wall Street like the barber who cuts people's hair at Goldman Sachs. I even convinced my editor to let me live like a billionaire for a day, wearing a 30,000 dollar watch and driving around in a Rolls Royce, flying in a private jet. Tough job, but someone's got to do it.And I found that this new human approach to my job made me feel much more optimistic about my own future, because you can teach a robot to summarize the news or to write a headline that's going to get a lot of clicks from Google or Facebook, but you can't automate making someone laugh with a dumb limerick about the bond market or explaining what a collateralized debt obligation is to them without making them fall asleep. And as I researched more, I found so many more examples of people who had succeeded this way by refusing to compete with machines and instead making themselves more human.Take Rus. Rus Garofalo is my accountant. He helps me with my taxes every year, and as you can probably tell from the photo, Rus is not a traditional accountant. He's a former standup comedian, and he brings his comedic sensibility to his work. I swear, I've had more fun talking about itemized deductions with Rus than at actual comedy shows that I've paid real money to see. Rus knows that in the age of TurboTax, the only way for human accountants to stay relevant is bringing something to the table other than tax expertise. So he started a company called Brass Taxes. Get it? He hired a bunch of other funny and personable accountants, and he started looking for clients in creative industries who would appreciate the value of having a human being walk them through their taxes.Now, technically, I should be very worried about Rus, because tax preparation is a highly automation-prone industry. In fact, according to an Oxford University study, it has a 99 percent chance of being automated. But I'm not worried about Rus, because he's figured out a way to turn tax preparation from a chore into an entertaining human experience that lots of people, including me, are willing to pay for.Or take Mitsuru Kawai. Sixty years ago, Mitsuru started as a junior trainee at a Toyota factory in Japan. He made car parts by hand. And this was the 1960s, an era where the auto industry was undergoing a huge technological transformation. The first factory robots had started coming onto the assembly lines, and a lot of people were worried that auto workers were going to become obsolete. Mitsuru decided to focus on what, in Japanese, is called "monozukuri" — basically, human craftsmanship. He studied all the nuanced, intricate details of auto design, and he developed these kind of sixth-sense skills that few of his other colleagues had. He could listen to a machine and tell when it was about to break or look at a piece of metal and figure out what temperature it was just by what shade of orange it was glowing. Eventually, Mitsuru's bosses noticed that he had all these skills that his coworkers didn't, and they made him really valuable, because he could work alongside the robots filling in the gaps, doing the things that they couldn't do. He kept getting promoted and promoted, and just this year, Mitsuru Kawai was named Toyota's first-ever Chief Monozukuri Officer, in recognition of the 60 years that he spent teaching Toyota workers that even in a highly automated industry, their human skills still matter.Or take Marcus Books. Marcus Books is a small, independent, Black-owned bookstore in my hometown of Oakland, California. It's a pretty amazing place. It's the oldest Black-owned bookstore in America, and for 60 years, it's been introducing Oaklanders to the work of people like Toni Morrison and Maya Angelou. But the most amazing thing about Marcus Books is that it's still here. So many independent bookstores have gone out of business in the last few decades because of Amazon or the internet.So how did Marcus Books do it? Well, it's not because they have the lowest prices or the slickest e-commerce setup or the most optimized supply chain. It's because Marcus Books is so much more than a bookstore. It's a community gathering place, where generations of Oaklanders have gone to learn and grow. It's a safe place where Black customers know that they're not going to be followed around or patted down by a security guard. As Blanche Richardson, one of the owners of Marcus Books, told me, "It just has good vibes."Earlier this year, Marcus Books temporarily closed, and like a lot of businesses, its future was uncertain. It was raising money through a GoFundMe page. And then George Floyd was killed. The streets filled with protests, and orders poured in to Marcus Books from all over the country — first, a hundred books a day, then 200, then 300. Today, they're selling five times as many books as they were before the pandemic, and their GoFundMe page has raised more than 250,000 dollars. And if you look at the comments on its GoFundMe page, you can see why Marcus Books has survived all these years. One person wrote that we have a duty to preserve gems like this in our community. Someone else said, "I've been going to Marcus Books since I was a child, and Blanche Richardson showed me many kindnesses." "Gems." "Kindnesses." Those aren't words about technology. They're not even words about books. They're words about people. The thing that saved Marcus Books was how they made their customers feel: an experience, not a transaction.If you, like me, sometimes worry about your own place in an automated future, you have a few options. You can try to compete with the machines. You can work long hours, you can turn yourself into a sleek, efficient productivity machine. Or you can focus on your humanity and doing the things that machines can't do, bringing all those human skills to bear on whatever your work is. If you're a doctor, you can work on your bedside manner so that your patients come to see you as their friend rather than just their medical provider. If you're a lawyer, you can work on your trial skills and your client interactions rather than just cranking out briefs and contracts all day. If you're a programmer, you can spend time with the people who actually use your products, figure out what their problems are and try to solve them, rather than just hitting next quarter's growth targets.That's how we become futureproof. Not by taking on the machines, but by excelling in the areas where humans have a natural advantage. By living and working more like humans, we can make ourselves impossible to replace. And the good news is that we don't have to learn a single line of code or deploy a single algorithm. In fact, you already have everything you need.Thank you. Wh Changing people's financial behavior is difficult, but it is possible.[Your Money y and Your Mind with Wendy De La Rosa]One company that was looking to talki reduce energy consumption in San Diego tried to change people's behaviors by ng using signs with one key sentence. What exactly was that sentence? Well, it to turns out that signs about protecting the environment or looking out for future you generations or signs that focus on the amount of money that people will save r were not effective in reducing consumers' energy consumption. Instead, the frie message that worked the best was a simple one that read, "The majority of your nds neighbors are undertaking energy-saving actions every day.”A similar message can focusing on what our neighbors are doing was used in the UK to incentivize help British taxpayers to pay their taxes on time. That simple change, pointing out you what other people are doing, led to an increase in collections of about 29 sav percent.Psychologist Robert Cialdini, who worked on both of these studies, calls e this phenomenon "social proof." He says people look to what others do in order mo to guide their own behavior. It's no wonder, then, that we base a lot of our own ney fiscal decisions on what other people do. And unfortunately, what we most easily observe are other people's spending behavior, not their savings behavior. It's easy to notice if your friend goes on vacation or buys a new car or a swanky pair of shoes. And with social media, you can even keep tabs on the shopping habits of the rich and the famous. Now, if someone wins the lottery,we'd expect them to spend more money — and they do. But what's really interesting is what happens to their neighbors. A recent study found that close neighbors of lottery winners are more likely to borrow money, spend more on goods and eventually declare bankruptcy. In fact, the larger the lottery winner, the higher the rate of bankruptcy among the neighbors of the lottery winners. Basically, the lottery winner's behavior is rubbing off on their neighbors.We are always aware of consumer spending, but what we are not aware of are other people's savings behavior. So let's lift that veil. You can start with just a couple of friends. Instead of asking where they bought their new bike or the best time of year to travel to France, ask them if they paid down their mortgage or if they have an emergency fund or if they've paid off their student loan. Tell them about your own financial situation.To really make this a social affair, I encourage you to start celebrating paying down your debts. Maybe you've seen the viral video of a happy dancing woman who paid off more than 200,000 dollars in student debt. She was able to achieve this incredible milestone because she was bold enough to ask her colleagues and her industry peers how much they earned, noting the thousands of dollars that she was missing out on, and finding a job that would pay her her fair market rate.I think that video gained notoriety because it's not often that we get to see what people have saved and how they're doing it. But it shouldn't be so rare. By having check-ins with your friends, you can help make a trend. I remember when I paid off my student loan, I wish I would have celebrated that milestone with friends. But at the time, I, too, was brainwashed into thinking that I shouldn't talk to my friends about money, that it was a scary taboo subject. Don't be like me. Start the conversation today.Research has shown that our social bonds make us healthier. It's time to harness your social ties to boost your financial fitness, too. Your future self will thank you. Once each year, thousands of logicians descend into the desert for Learning Man, a week-long event they attend to share their ideas, think through tough problems... and mostly to party. And at the center of that gathering is the world’s most exclusive club, where under the full moon, the annual logician’s rave takes place. The entry is guarded by the Demon of Reason, and the only way to get in is to solve one of his dastardly challenges.You’re attending with 23 of your closest logician friends, but you got lost on the way to the rave and arrived late. They're already inside, so you must face down the demon alone. He poses you the following question:When your friends arrived, the demon put masks on their faces and forbade them from communicating in any way. No one at any point could see their own masks, but they stood in a circle where they could see everyone else’s. The demon told the logicians that he distributed the masks in such a way that each person would eventually be able to figure out their mask’s color using logic alone. Then, once every two minutes, he rang a bell. At that point, anyone who could come to him and tell him the color of their mask would be admitted.Here’s what happened: Four logicians got in at the first bell. Some number of logicians, all in red masks, got in at the second bell. Nobody got in when the third bell rang. Logicians wearing at least two different colors got in at the fourth bell. All 23 of your friends played the game perfectly logically and eventually got inside. Your challenge, the demon explains, is to tell him how many people gained entry when the fifth bell rang.Can you get into the rave?Pause here to figure it out yourself.Answer in 3Answer in 2Answer in 1It’s initially difficult to imagine how anyone could, using just logic and the colors they see on the other masks, deduce their own mask color. But even before the first bell, everyone will realize something critical. Let’s imagine a single logician with a silver mask. When she looks around, she’d see multiple colors, but no silver. Can So she couldn’t ever know that silver is an option, making it impossible for her to you logically deduce that she must be silver. That contradicts rule five, so there must solv be at least two masks of each color.Now, let’s think about what happens when e there are exactly two people wearing the same color mask. Each of them sees the only one mask of that color. But because they already know that it can’t be the logi only one, they immediately know that their own mask is the other. This must be cian what happened before the first bell: two pairs of logicians each realized their 's own mask colors when they saw a unique color in the room.What happens if rave there are three people wearing the same color? Each of them—A, B and C— ridd sees two people with that color. From A’s perspective, B and C would be le? expected to behave the same way that the orange and purple pairs did, leaving at the first bell. When that doesn’t happen, each of the three realizes that they are the third person with that color, and all three leave at the next bell. That was what the people with red masks did— so there must have been three of them. We’ve now established a basis for inductive reasoning. Induction is where we can solve the simplest case, then find a pattern that will allow the same reasoning to apply to successively larger sets. The pattern here is that everyone will know what group they’re in as soon as the previously sized group has the opportunity to leave.After the second bell, there were 16 people. No one left on the third bell, so everyone then knew there weren’t any groups of four. Multiple groups, which must have been of five, left on the fourth bell. Three groups would leave a solitary mask wearer, which isn’t possible, so it must’ve been two groups. And that leaves six logicians outside when the fifth bell rings: the answer to the demon’s riddle. Nothing left to do but join your friends and dance. In the next few minutes, I hope to change the way you think about the very nature of reality itself. I'm not a physicist, and I'm not a philosopher. I'm a historian. And after studying the ancient Greeks and many other premodern peoples for more than 20 years as a professional, I've become convinced that they all lived in real worlds very different from our own.Now, of course, you and I here today, we take it for granted that there's just one ultimate reality out there — our reality, a fixed universal world of experience ruled by timeless laws of science and nature. But I want you to see things differently. I want you to see that humans have always lived in a pluriverse of many different worlds, not in a universe of just one. And if you're willing to see this pluriverse of many worlds, it will fundamentally change, I hope, the way you think about the human past and hopefully the present and the future as well.Now, let's get started by asking three Wh basic questions about the contents of our reality, the real world that you and I y share right here, right now. First of all: What is it that makes something real in ther our real world? Well, for us, real things are material things, things made of e's matter that we can somehow see, like atoms, people, trees, mountains, no planets ... By the same token, invisible, immaterial things — like gods and suc demons, heavens and hells — these are considered unreal. They're simply h beliefs, subjective ideas that exist only in the realm of the mind. To be real, a thin thing must exist objectively, in some visible material form, whether our minds can g as perceive it or not.Second: What are the most important things in our real world? obje Answer: human things — people, cities, societies, cultures, government, ctiv economies. Why is this? Well, because we humans think we're special. We think e we're the only creatures on the planet who have things like language, reason, reali free will. By contrast, nonhuman things, to us, are just part of nature, a mere ty backdrop to human culture, a mere environment of things that we feel entitled to use however we want.And third: What does it mean to be a human in our real world? Well, it means being an individual, a person who lives ultimately for oneself. We think nature has made us this way, giving each and every one of us all of the reason, the right, the freedom and the self-interest to thrive and compete with other individuals for all of life's important resources.But I'm suggesting to you that this real world of ours is neither timeless nor universal. It's just one of countless different real worlds that humans have experienced in history. What, then, would another world look like? Well, let's look at one, the real world of the classical Athenians in ancient Greece.Now, of course, we usually know the Athenians as our cultural ancestors, pioneers of our Western traditions, philosophy, democracy, drama and so forth. But their real world was nothing like our own. The real world of the Athenians was alive with things that we would consider immaterial and thus unreal. It pulsated with things like gods, spirits, nymphs, Fates, curses, oaths, souls and all kinds of mysterious energies and magical forces. Indeed the most important things in their real world were not humans at all, but gods. Why? Because gods were awesome — literally. They controlled all the things that made life possible: sunshine, rainfall, crop harvests, childbirth, personal health, family wealth, sea voyages, battlefield victories. There were over 200 gods in Athens, and they were not remote, detached divinities watching over human affairs from afar. They were really there, immediately there in experience, living in temples, attending sacrifices, mingling with the Athenians at their festivals, banquets and dances.And in the real world of the Athenians, humans did not live apart from nature. Their lives were dictated by the rhythms of the seasons and by the life cycles of crops and animals. Indeed the land of the Athenians itself was not just a piece of property or territory. It was a goddess, a living goddess that had once given birth to the first Athenians and had nurtured and cared for all of their descendants ever since, with her precious gifts of soils, water, stone and crops. Indeed, if anything should pollute her soils with unlawful bloodshed, it had to be expelled immediately, beyond her boundaries, whether it was a man, an animal or just a fallen roof tile.And in the real world of the Athenians, there were no individuals. All Athenians were inseparable from their families, and all Athenian families were expected to live together and work together as a single body, like cells of a living organism. They called this social body simply "demos," the people, and they called their way of life "demokratia," but it was nothing like our modern democracy, because Athenians were not born to be individuals living for themselves. They were born to serve and preserve the families and the social body that had given them life in the first place.In sum, the whole Athenian way of being human was radically different from our own. Nature had programmed them to live as one, as a unitary social body, and it had designed them expressly to coexist and collaborate with all manner of nonhuman beings, especially their 200 gods and their divine earth mother. Life in Athens was thus sustained by what we can call a "cosmic ecology," a symbiotic ecology of gods, motherland and people.Now, of course, to us today in our real world, we look at their real world and, well, it looks strange, weird, bizarre, exotic and, of course, unreal. But it has many major things in common with the real world experienced by numerous other premodern peoples, including, for example, the ancient Egyptians, ancient Chinese and the peoples of precolonial Peru, Mexico, India, Bali, Hawaii. In all of those premodern real worlds, gods controlled all of the conditions of existence. Nonhumans were always expected to collaborate with humans and vice versa. And humans were expected to serve their communities, not to live for themselves as individuals.Indeed, in the grand scheme of history, it's our real world, our reality, that is the great exception to the rule — the exotic one, the strange one. Only in our real world is reality itself a purely material order. Only in our real world are nonhumans always subordinate to humans. And only in our real world are humans born to be individuals. Why this uniqueness? Well, because our real world was shaped and forged in a unique environment, a historically unprecedented environment in early modern Europe, with its scientific revolution, its enlightenment, its novel, experimental, capitalist way of life.Yet, despite this uniqueness, we just take it for granted that our reality is the one true reality, that all humans in history have lived in only our real world, whether they knew it or not. And just think for a moment of the colossal arrogance of this assumption. Basically, we're saying, "We modern Westerners are right about reality, and everybody else in all of history is wrong." Basically, we're saying that all of those extraordinary civilizations of the past were really just lucky accidents, because they were all founded on nothing more than myths, illusions and false ideas about reality.Why are we so certain that we're right? Why do we just take it for granted that we know more? Why do we struggle to take seriously the real worlds of premodern peoples? Well, because we think our modern sciences provide the only truly objective knowledge of reality. But do they?For more than a hundred years now, the very idea of an objective reality has been seriously and continually questioned by experts in many different fields, from physics and biology to philosophy. Basically, these experts would suggest that reality is not simply a material order given to us by nature. It is something that humans actively participate in producing when their minds interact with their environment.Here's a way to think about it. In order to make sense of experience, every people in the past, in effect, had to devise a model of the real world. They would then use that model as the basis for their whole way of life, all of its practices, its norms, its values. And if that way of life proved to be successful in practice, sustainable, then the truth of the model would be confirmed by the evidence of everyday experience: "It works!" And thus, once the model became internalized in mind and baked into the environment, the effect of a stable real world would be generated by ongoing interactions between the two, between minds on the one hand, environments on the other.Let's take a quick example. Why are we so convinced in our modern world that we're all, ultimately, natural individuals? Well, because a bunch of social scientists in early modern Europe decided that we were, and because their model of a world full of natural competitive individuals became the basis for a new, capitalist way of life that generated unprecedented levels of wealth — at least for the lucky few — and because all of us who've been raised in capitalist nations ever since have been continually socialized to be individuals by our families, our schools and our societies, and because we are treated precisely as individuals almost every day of our lives by the structures which control those lives, like our liberal democracy and our capitalist economy. In other words, our minds and our environment continually conspire to make our individuality seem entirely natural.In sum: no human being has ever experienced a truly objective reality. Different peoples have always experienced different realities, each one shaped by whatever model of the world happened to be embedded in minds and environment at the time. In other words, humans have always lived in a pluriverse of many different real worlds, not in a universe of just one. Let me close with three thoughts that follow from this conclusion.First of all, we modern Westerners need to stop thinking that all premodern peoples are somehow more primitive or less enlightened than ourselves. Their real world, with all their gods and magical forces, were just as real as our own. Indeed, those real worlds anchored ways of life that sustained the lives of multitudes for hundreds, sometimes thousands, of years. Their real worlds were different; they were not wrong.Second: we modern Westerners need to get over ourselves.(Laughter)We need to be a little more humble. For all of its extraordinary technological accomplishments, our brave new modern real world has imperiled the whole future of the planet in barely 300 years. It's made possible all manner of historical horrors: genocides across entire continents, mass exploitation of colonized peoples, industrial servitude, two disastrous world wars, the Holocaust, nuclear warfare, species extinctions, environmental degradation, factory farming and, of course, global warming. The evidence is there if you want to see it. Our model of reality has failed catastrophically in practice.Third: other models and other real worlds are possible. Other worlds are being lived right now, as we speak, in what remains of history's pluriverse, in places like Amazonia, the Andes, Southern Mexico, Northern Canada, Australia and all the other places where Indigenous peoples are struggling to preserve their highly sustainable ancestral ways of life to prevent them being destroyed by modernity's ever-expanding universe. I suggest that all of these nonmodern peoples past and present have so much to teach us about living more sustainable lives in other possible worlds.So let's start right now to try to learn from them before it's too late. Let's try to magnify our imaginations. Let's start to imagine other possible ways of being human in other possible worlds.Thank you.(Applause and cheers) As of 2020, the world’s biggest lithium-ion battery is hooked up to the Southern California power grid and can provide 250 million watts of power, or enough to power about 250,000 homes. But it’s actually not the biggest battery in the world: these lakes are.Wait— how can a pair of lakes be a battery? To answer that question, it helps to define a battery: it’s simply something that stores energy and releases it on demand. The lithium-ion batteries that power our phones, laptops, and cars are just one type. They store energy in lithium ions. To release the energy, the ions are separated from their electrons, then rejoined at the other end of the battery as a new molecule with lower energy.How do the two lakes store and release energy? First, one is 300 meters higher than the other. Electricity powers pumps that move billions of liters of water from the lower lake to the higher one. This stores the energy by giving the water extra gravitational potential energy. Then, when there’s high demand for electricity, valves open, releasing the stored energy by letting water flow downhill to power 6 giant turbines that can generate 3 billion watts of power for 10 hours.We’re going to need more and more giant batteries. That’s because right now, generating enough electricity to power the world produces an unsustainable amount of greenhouse gas: 14 billion tons per year. We’ll need to get that The number down to net-zero. But many clean energy sources can’t produce worl electricity 24/7. So to make the switch, we need a way to store the electricity d's until it's needed. That means we need grid-scale batteries: batteries big enough big to power multiple cities.Unfortunately, neither of the giant batteries we’ve talked gest about so far can solve this problem. The two lakes setup requires specific batt geography, takes up a lot of land, and has high upfront costs to build. The giant ery lithium-ion battery in California, meanwhile, can power about 250,000 homes, look yes, but only for an hour. Lithium-ion batteries are great for things that don’t use s a lot of power. But to store a lot of energy, they have to be huge and heavy. not That’s why electric planes aren’t a thing: the best electric plane can only carry hin two people for about 1,000 kilometers on one charge, or its batteries would be g too heavy to fly. A typical commercial jet can carry 300 people over 14,000 km like before refueling. Lithium-ion batteries also require certain heavy metals to make. a These resources are limited, and mining them often causes environmental batt damage.Inventors all over the world are rising to the challenge of making ery batteries that can meet our needs— many of them even weirder than the two lakes.One company is building a skyscraper battery. When the sun is shining, a crane powered by solar energy piles blocks on top of each other in a tower. At night, the cranes let gravity pull the blocks down and use the resulting power to spin generators.Though there have been some early setbacks, another promising approach involves heating up salts until they melt. The molten salt can be stored until there’s a high demand for electricity, then used to boil water. The steam can power turbines that generate electricity.Another idea: bio-batteries made from paper, powered by bacteria, and activated by spit. Bacteria release energy in the form of electrons when they metabolize glucose, and at least one species of bacteria can transfer those electrons outside its cells, completing a circuit. While these batteries won’t power a city, or even a house, they don't have the waste and cost concerns of traditional batteries.From vast mountain lakes to microscopic bacteria, from seawater batteries that bypass the need for heavy metals to nuclear batteries that power deep space missions, we're constantly rethinking what a battery can be. The next unlikely battery could be hiding in plain sight— just waiting to be discovered and help us achieve a sustainable future. "Ali A few years ago, a stranger sitting next to me on a plane, asked what I did for a ens living. I told him that I'm an archeologist and I study the ancient Maya. He said, buil "Wow, I love archeology," and told me how excited he gets when hearing about t new finds. Then he told me how amazing it is that aliens from the planet Nibiru the had come to Earth and established the ancient Sumerian culture in pyr Mesopotamia. I have these conversations a lot on planes, in bookstores and in ami bars. People want to talk with me about pseudoarcheology, something that ds" seems like archeology, but isn't. It involves making wild and unproven claims and about the human past, things like aliens built the pyramids or survivors from the oth lost continent of Atlantis invented hieroglyphic writing.Now, most of us know that er claims like these are unfounded and frankly absurd. Yet they're everywhere. abs They're on TV shows, in movies and in books. Think of the History Channel urdi series "Ancient Aliens," currently in its 15th season, or of the most recent Indiana ties Jones movie about the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, or Erich von Däniken’s of classic book “Chariots of the Gods?” Here's the crucial question. Who cares? It's pse just entertainment, right? Isn't it a nice escape from reality and a fun way to think udo about the world? It's not. Most pseudoarcheology is racist and xenophobic and like other forms of entertainment, it influences our culture in real ways. Let me arc give you an example.It's common to hear pseudoarcheologists claim that groups hae like the ancient Egyptians or the ancient Maya accomplished incredible things, olo but only with the help of outside groups, like aliens or people from Atlantis. What gy you rarely hear is pseudoarcheologists claiming that, say, Romans had help building the Colosseum or that Greeks had help building the Parthenon. Why is that? For pseudoarcheologists Europeans could have accomplished their feats on their own, but non-Europeans must have had outside guidance. Claims like these are not just outrageous. They are offensive. Here and in so many other instances, pseudoarcheology sustains myths of white supremacy, disparages non-Europeans and discredits their ancestors' achievements.I've spent the last 12 summers doing archeological fieldwork in the Maya area. Several years back, I was staying in a small village along the Belize–Guatemala border. I spent day after day in the lab, staring at tiny, brown, eroded pieces of ceramics. The Maya man who lived across the street made slate carvings to sell to tourists. He'd stop by every once in a while to chat. And one day he brought over a slate carving, and it was this image. The image carved into the sarcophagus lid of the Maya king Pakal around his death in 683 AD. This image is incredible and it's complex. It shows the deceased king rising from the jaws of the underworld to be reborn as a deity. In the center is a stylized world tree that extends from the underworld through the realm of the living into the upper world. Around the edges is a sky band with symbols for the sun, moon and stars.I was so excited to talk with my neighbor about ancient Maya religion, cosmology and iconography. Instead, he wanted to talk about an "Ancient Aliens" episode he had seen. The one about the Maya. And he told me that this image was of an astronaut at the controls of a rocket ship. I was shocked. Instead of marveling at his own ancestors, he was in awe of a fictional alien. He even told me that one day, he hoped to give this carving to Erich von Däniken, father of the ancient aliens phenomenon.Pseudoarcheology undoubtedly harms its subjects, often Indigenous people, like the Maya, but it also harms its viewers. It harms all of us. Like other forms of racism, it exacerbates inequality and prevents us from appreciating and benefiting from human diversity.What's really scary is that pseudoarcheology is a small part of a much bigger problem. It's just one example of people getting history wrong on purpose, of people knowingly changing historical and archeological facts. Why would anybody do that? Often, the past is knowingly changed either to justify racism in the present or to present a nicer version of history, a version of history that we can all take pride in.Six years ago, Jefferson County, Colorado became a battleground over how to teach American history to high school students. The Advanced Placement curriculum had been expanded to include things like the removal of Native Americans to reservations and the rise of extreme economic inequality. Members of the local school board were upset. They vigorously protested the changes, arguing that the new curriculum didn't do enough to promote capitalism or American exceptionalism.Right now we are in the midst of a heated debate over public monuments to controversial figures. People like Robert E. Lee and Christopher Columbus. Should these monuments be left as they are, destroyed or put in museums and what should happen to the protestors who deface these monuments? Should they be praised for helping debunk myths of white supremacy? Or should they be punished for vigilantism and lawlessness? What do we make of scenes like this?For me, debates about history curricula and public monuments suggest similar messages. First, the past is political. What we choose to remember and forget relates directly to current political concerns. Second, we need to consider who presents the past, who chooses the content of history textbooks and the subject matter of public monuments. Imagine how our understanding of history might be different if it was told by the marginalized, rather than the powerful. We can help combat racism and xenophobia today by changing how we think about the past. Archeologists need to do two things. First, we need to make our discipline more inclusive. We need to work with and for the descendants of the people we study.Richard Leventhal's work at Tihosuco, Mexico is groundbreaking, pun intended. For over a century, foreign archeologists have traveled to the Maya area to excavate the things they thought were interesting. Mostly temples and pyramids. Leventhal took a different approach. Instead he asks the contemporary Maya of Tihosuco what they thought was interesting, and it turns out they didn't particularly care about temples or pyramids. They were interested in the Caste War, a major but understudied colonial period Maya rebellion.Second, we need to make archeology more accessible. The last time I walked into a bookstore, I asked where I could find the archeology books. The clerk took me to a section labeled "Ancient Mysteries and Lost Knowledge." It had books with titles like "Extraplanetary Experiences." And what is absolutely absurd about this is that real archeology, archeology based in scientific facts and historical context, is fascinating. You don't need aliens to make it interesting. It's up to us archeologists to find new ways to share our work with the public.And this used to be the norm. In the 1950s, there was a game show on CBS called "What in the World?" The host would present an object, an artifact, and the archeologist contestants would try to figure out what this thing was and where it was from. The show was funny and interesting and exposed viewers to the diversity of human cultures.Beginning in the mid-to-late 1960s, archeology changed focus. Instead of concentrating on public engagement, archeologists began working together to professionalize the discipline. On the plus side, we now have things like Bayesian analysis of radiocarbon dates and theoretical approaches, like the new materialisms. But in the process, archeology left the public behind. Shows like “What in the World?” became less common and pseudoarcheology emerged to fill the void.But we can all contribute to changing how we think about the past. When you see a pseudoarcheological claim, be skeptical and know that if you post about Atlantis, tweet about ancient aliens or forward a clip from a pseudoarcheology TV show, even if it's not your intention, you may be promoting racism and xenophobia. Also know that the past is alive. It is political, it is everchanging and it influences our daily lives in meaningful ways. So the next time that you watch the History Channel, read an archeology book or view a public monument, remember that every statement about the past is a powerful statement about the present.Thank you. Christiana Figueres: Today, February 19, 2021, at the beginning of a crucial year and a crucial decade for confronting the climate crisis, the United States rejoins the Paris Climate Agreement after four years of absence. Unanimously adopted by 195 nations, the Paris Agreement came into force in 2016, establishing targets and mechanisms to lead the global economy to a zero-emissions future. It was one of the most extraordinary examples of multilateralism ever, and one which I had the privilege to coordinate. One year later, the United States withdrew.The Biden-Harris administration is now bringing the United States back and has expressed strong commitment to responsible climate action. The two men you are about to see both played essential roles in birthing the Paris Agreement in 2015. Former Vice President Al Gore, a lifelong climate expert, made key contributions to the diplomatic process. John Kerry was the US Secretary of State and head of the US delegation. With his granddaughter sitting on his lap, he signed the Paris Agreement on behalf of the United States. He is now the US Special Envoy for Climate.TED Countdown has invited Al Gore to interview John Kerry as he begins his new role. Over to both of them.Al Gore: Well, thank you, Christiana, and John Kerry, thank you so much for doing this The interview. I have to say on a personal basis, I was just absolutely thrilled when US President Biden, then president-elect, announced you were going to be taking is on this incredibly important role. And thank you for doing it. Let me just start by bac welcoming you to TED Countdown and asking you, how are you feeling as you k in step back into the middle of this issue that has been close to your heart for so the long?John Kerry: Well, I feel safer being here with you. I honestly, I feel very Pari energized, very focused. I think it's a privilege to be able to take on this task. And s as you know better than anybody, it's going to take everybody coming together. Agr There's going to have to be a massive movement of people to do what we have eem to do. So I feel privileged to be part of it, and I’m honored to be here with you on ent. this important day.AG: Well, it's been a privilege to be able to work with a dear Wh friend for so long on this crisis. And, of course, on this historic day, when the at's United States now formally and legally rejoins the Paris Agreement, we have to next acknowledge that the world is lagging behind the pace of change needed to ? successfully confront the climate crisis, because even if all countries kept the commitments made under the Paris Agreement — and I watched you sign it, you had your grandchild with you — I was there at the U.N, that was an inspiring moment, you signed on behalf of the United States, but even if all of those pledges were kept they're not strong enough to keep the global temperature increase well below two degrees or below 1.5 degrees, and emissions are still rising. So what needs to happen here in the US and globally in order to accelerate the pace of change?JK: Well, Al, you're absolutely correct. It's a very significant day, a day that never had to happen, America returning to this agreement. It is so sad that our previous president, without any scientific basis, without any legitimate economic rationale, decided to pull America out. And it hurt us and it hurt the world. Now we have an opportunity to try to make that up. And I approach that job with a lot of humility for the agony of the last four years of not moving faster.But we have to simply up our ambition on a global basis. United States is 15 percent of all the emissions. China is 30 percent. EU is somewhere around 14, 11, depends who you talk to. And India is about seven. So you add all those together, just four entities, and you've got well over 60 percent of all the emissions in the world. And yet none of those nations are at this moment doing enough to be able to get done what has to be done, let alone many others, at lower levels of emission. It's going to take all of us. Even if tomorrow China went to zero, or the United States went to zero, you know full well, Al, we're still not going to get there. We all have to be reducing greenhouse gas emissions. We have to do it much more rapidly.So the meeting in Glasgow rises in its importance. You and I, we've been to these meetings since way back in the beginning of the '90s with Rio and even before, some of them parliamentary meetings. And we’re at this most critical moment where we have a capacity to define the decade of the '20s, which will really make or break us in our ability to get to a 2050 net zero carbon economy. And so we all have to raise our ambition. That means coal has got to phase down faster. It means we've got to deploy renewables, all forms of alternative, renewable, sustainable energy. We've got to push the curve of discovery intensely. Whether we get to hydrogen economy or battery storage or any number of technologies, we are going to have to have an all-of-the-above approach to getting where we need to go to meet the target in this next 10 years.And I think Glasgow has to not only have countries come and raise ambition, but those countries are going to have to define in real terms, what their road map is for the next 10 years, then the next 30 years, so that we're really talking a reality that we've never been able to completely assemble at any of these meetings thus far.AG: Well, hearing you talk, John, just highlights how painful it's been for the US to be absent from the international effort for the last four years, and again, it makes me so happy President Biden has brought us back into the Paris Agreement. After this four year hiatus, how are you personally, as our Climate Envoy, planning to approach re-entry into the conversation? I know you've already started it, but is there anything tricky about that? Or I guess everything is tricky about it, but how are you planning to do it?JK: Well, I'm planning, first of all, to do it with humility, because I think it's not appropriate for the United States to leap back in and start telling everybody what has to happen. We have to listen. We have to work very, very closely with other countries, many of whom have been carrying the load for the last four years in the absence of the United States. I don't think we come in, Al, I want to emphasize this — I don't believe we come to the table with our heads hanging down on behalf of many of our own efforts, because, as you know, President Obama worked very hard and we all did, together with you and others, to get the Paris Agreement. And we also have 38 states in America that have passed renewable portfolio laws. And during the four years of Trump being out, the governors of those 38 states, Republican and Democrat alike, continued to push forward and we're still in movement. And more than a thousand mayors, the mayors of our biggest cities in America, all have forged ahead. So it's not a totally, abjectly miserable story by the United States. I think we can come back and earn our credibility by stepping up in the next month or two with a strong national determined contribution.We’re going to have a summit on April, 22. That summit will bring together the major emitting nations of the world again. And because, as you recall in Paris, a number of nations felt left out of the conversation. The island states, some of the poorer nations, Bangladesh, others. And so we're going to bring those stakeholders to the table, as well as the big emitters and developed countries, so that they can be heard from the get-go. And as we head on into Glasgow, hopefully we'll be building a bigger momentum and we'll have a larger consensus. And that's our goal — have the summit, raise ambition, announce our national determined contribution, begin to break ground on entirely new initiatives, build towards the biodiversity convention in China, even though we're not a party, we want to be helpful, and then go into the G7, the G20, the UNGA, the meeting of the United Nations in the fall, reconvene and reenergize, going for the last six weeks into Glasgow.In my judgment, Glasgow, and you'd know this full well, I think Glasgow is the last, best hope we have for our nations to really set us on that path. And so, you know, one key is, as I said, raising ambition. The other is defining how you're going to get there, and then the third is finance. We've got to bring an unprecedented global finance plan to the table. And I think we're already working with private sector entities. I believe there's a way to do that in a very exciting way.AG: Well, that's encouraging, and I'm going to come back to that in just a moment. But I'm glad you made those points about state and local governments actually moving forward during the last four years. A lot of US private companies have as well. And already I'm extremely encouraged by the suite of executive actions that President Biden has already taken during his first weeks in office. And there's more to come. There's also a push for legislative action to invest in the fantastic new opportunities in clean energy, electric vehicles and more. Yet you and I have both seen the difficulties of this approach in the past. How can we use all of this activity to well and truly convince the world that America is genuinely back to being part of the solution? I know we are. You know we are, but we've got to really restore that confidence. I think your appointment went a long way to doing that. But what else can we do to gain back the world's confidence?JK: Well, we have to be honest and forthright and direct about the things that we're prepared to do. And they have to be things we're really going to do. We just held a meeting a few days ago with all of the domestic entities that President Biden has ordered to come to the table and be part of this effort. This is an all-of-government effort now. So we will have the Energy Department, the Homeland Security Department, the Defense Department, the Treasury. I mean, Janet Yellen was there talking about how she's going to work and we're going to work together to try to mobilize some of the finance. So I think, you know, we're not going to convince anybody by just saying it. Nor should we. We have to do it. And I think the actions that we put together shortly after President Biden achieves the COVID legislation here, he will almost immediately introduce the rebuild effort, the infrastructure components, and those will be very much engaged in building out America's grid capacity, doing things that we should have done years ago to facilitate the transmission of electricity from one part of the country to another, whether it's renewable or otherwise. We just don't have that ability now. We have a queue of backed up projects sitting in one of our regulatory agencies which have got to be broken free. And by creating this all-of-government effort, Al, our hope is we're really going to be able to do that.The other thing that we're doing is I'm reaching out, very rapidly, to colleagues all around the world. We've had meetings already, discussions with India, with Latin American countries, with European countries, with the European Commission and others. And we're going to try to build as much energy and momentum as possible towards these various benchmarks that I've talked about. And I mean, the proof will be in the pudding. We're going to have to show people that we've got a strong NDC, we're actually implementing, we're passing legislation, and we're moving forward in a collegiate manner with other countries around the world.For instance, I've talked to Australia, we had a very good conversation. Australia has had some differences with us. We've not been able to get on the same page completely. That was one of the problems in Madrid, as you recall, together with Brazil. Well, I've reached out to Brazil already, we're starting to work on that. My hope is that we can build some new coalitions and approach this, hopefully in a new way.AG: Well, that's exciting, and I do agree with your statement earlier that the COP26 conference in Glasgow this fall may be the world's last, best chance, I like your phrase there. From your perspective, what would you list as the priorities for ensuring that this Glasgow conference is a success?JK: I think that perhaps one of the single most important things, which is why we're focused on this summit of ours, is to get the 17 nations, that produced the vast majority of emissions, on the same page of committing to 2050 net zero, committing to this decade, having a road map that is going to lay down how they are going to accelerate the reduction of emissions in a way that keeps 1.5 degrees as a floor alive and also in a way that guarantees that we are seeing the road map to get to net zero.I will personally be dissatisfied, disappointed if for our children's sake and our grandkids sake we can't say that when these adults came together to make this kind of a decision, we didn't actually make it. We've got to make it. And I think if we can show people we're actually on the road, I think you believe this as much as I do, that — I mean, you're far more knowledgeable than I am about some of the technologies and you've helped break ground on some of them. The pace at which we are now beginning to accelerate, I mean, the reduction in cost of solar, the movement in storage and other kinds of things, I'm convinced we're going to find one breakthrough or another. I don't know what it's going to be, but I do know that when we push the curve and we put the resources to work, the innovative creative capacity of humankind is such that we have an ability to surprise ourselves.We've always done it. When we went to the Moon in this incredible backdrop behind you. And that's exactly what we did. And people today use products in everyday household use that came out of that quest that you never would have anticipated. That's what's going to happen now. We can move faster to electric vehicles. No question in my mind, we could absolutely phase down coal-fired emissions faster than we are in a plan to do it. So the available choices are there. The test is going to be whether we create the energy and momentum necessary to actually get those choices made.AG: One of the big challenges is one you referred to earlier on finance. Wealthy countries have promised financial assistance to the less wealthy countries to help them out with cutting emissions and to help them cope with the impacts of the climate crisis. But of course, we need to continue to work to meet this commitment, especially as countries around the world rebuild their economies in the wake of this pandemic. What are some of the most effective ways in which the wealthier countries can help those that don't have as many resources, and why is this so important for the world to move forward?JK: Let me answer the last part first. It's so important because it's the only way we're going to get there. I don't believe that any government has either the money or the inclination to be able to do what's necessary here. I believe the private sector, particularly driven by venture capital investment, by the quest to be able to create a product that then can help create wealth and actually provide a benefit to humankind drives a lot of things that we've done all through history. And I don't think it'll be any different now.I think the question is, can we pull together enough nations to leverage a uniform approach to the judgment about the kinds of investments that are being made. And I believe that if we can standardize to some degree, with disclosure requirements, which Janet Yellen is now seized of that issue, and Europe, there are folks working on that and European Commission elsewhere, if we could actually find a way to come together and harmonize some of those definitions and the marketplace begins to make those judgments as they qualify risk, looking way out, risk, because of climate crisis for investing is very, very real. And we all understand that. We spent 265 billion dollars in America two years ago just cleaning up after three storms, Maria, Harvey and Irma. And it's crazy. You spend 265 billion to clean up after the storms, but we can't put 100 billion together for the Green Climate Fund. That's what this year has to be about. We've got to break that cycle. And I think business, I'm convinced of this, a lot of people will doubt me and say, have I lost my mind, but I'm convinced the private sector is going to be critical, if not the key to helping to make this happen. And that will leverage other money.I've talked to the IMF, we'll be talking with the World Bank, we're going to try to bring our own Finance Development Corporation in America. All of these things can help leverage investment into the sectors that can make the greatest difference to the rapid reduction of greenhouse gases. And I think people are going to get very excited about where this money is going to go and how much it is going to be. And my hope is in a matter of weeks to be in a position to make a couple of announcements with respect to that that could be helpful in building some of this momentum.AG: Well, that's great. It sounds like some major news coming in a couple of weeks and just one example you used, the point about businessmen. I have a friend in Australia, Mike Cannon-Brookes, building a long undersea cable from the northern territories of Australia to take renewable electricity to Singapore. You have made the point about the need for the US to approach this with humility a number of times. In that spirit, what lessons can a country like ours learn from some of the lower income nations that are already beginning to tackle climate change?JK: Well, I think one of the most important things, Al, is to make sure that central to this transformation, to this transition to the new energy economy, central to it is environmental justice, is that we don't leave people behind, that we're not making whole communities the recipients of the downside of some particular choice, that the diesel trucks, for instance, aren't all being routed through a particular low income community that doesn't have the ability to make a different political decision. I think it is vital for the developed world to recognize that there are nations, 138 nations or more, way below one percent in terms of emissions. And they're looking around some of them, like Tommy Remengesau, the president of Palau, who no longer can consider adaptation, he's got to figure out where his people are going to go live, as do other very low-lying areas in the ocean. So that impact on people is really not known by the vast majority of people who live pretty good lives in a lot of countries in the world. And we have a responsibility to make sure that we're learning the lesson of their lives and of their hopes and aspirations here.AG: Couldn't agree more. And here in the US, if we had paid more attention to the differential impact on Black, Brown and Indigenous communities, we would have had a better early warning of what the whole country was facing. But let me shift subjects and ask you about China. I know that you, as you are close friends with Xie Zhenhua, as I have been over the years, and I was very happy when he was brought out of retirement to play the lead role for them. But the US is now in the middle of a somewhat contentious relationship with China. But successfully solving the climate crisis is going to require collaboration between the US and China, we're the two biggest emitters and the two biggest economies. How can this collaboration be shaped, in your view? I know you played a role, as Joe Biden did before the Paris Agreement, in getting our two countries together. Can we do that again?JK: I hope so. I really do hope so, Al. As you just said, if we can — if we don't get China to be cooperating and partnering with the rest of the world on this, we don't solve the problem. And we unfortunately, we see too much investment in China right now in coal still. We've had some conversations about it. I was on a panel with Xie Zhenhua several months before the election by the University of California, and we had a very constructive conversation. My hope is that that will continue and can continue and that China will be just as constructive, if not more so, in this endeavor than they were in 2013 as we began the process to build up to Paris.AG: Well, that relationship is absolutely crucial. But in order to cover all the ground I want to cover here, let me shift again and ask you, what role do you expect that big corporations and also smaller businesses will play in moving this green transition forward?JK: I think they're the biggest single players in it. I mean, governments are important and governments can and have made a difference with tax credits. For instance, our solar tax credit made an enormous difference and it will make one going forward. And even in the middle of COVID, we've been able to hold on to that. But we need to grow those kinds of efforts. But in the end, it's not going to be government cash that makes this happen. It's going to be the private sector investment that is coming in because it's the right thing to do, because it's also smart investing. And the truth is, you can talk to many — and you have, you're one of the investors actually, Al — you and others have proven that you can invest in this sector of dealing with climate or environment or sustainability, whether it's ESG or it's pure climate. There are ways to have a good return on money. And during the last couple of years, we had something like, 13 to 17 trillion dollars sitting in parked banking situations around the world in net negative interest. In other words, they were paying for the privilege of sitting there, not invested in something. And so I think there's just a massive opportunity here. And most of the CEOs I am talking to, at least now, are increasingly aware of the potential of these alternatives. And you were in early, I don't know if you invested in it or not, but I know you're involved with Tesla or have been. Tesla is the most highly valued automobile company in the world. And it only makes one thing: electric car. If that isn't a message to people, I don't know what is.AG: I wish I had invested in Tesla, John, but I'm a huge fan of Elon Musk and what he's doing. I'm also a huge fan of Greta Thunberg. And I'm just curious what you think in practical terms is the real impact for change coming from these youth movements like Fridays for the Future?JK: I think it's been gigantic and spectacular and in the best traditions of what young people do and have done historically. I mean, as you recall, in America, at least in the 1960s, it was young people who drove the environment movement, the peace movement, the women's movement, the civil rights movement, and they were willing to put their lives on the line. And Greta has been just unbelievable. And in the way in which she has held adults accountable and it has created this wonderful movement. I've met so many young people, many of whom have worked in one fashion or another with me in the last few years, who were brought to it from Fridays for the Future, from the Sunrise Movement, or, you know, it's all that focused youthful idealism and energy and it demands to be heard. And I think all of us, I mean, we should be ashamed of ourselves that we have to have people who were then 16 or 15 not going to school to get our attention. I mean, what the hell is the matter with adult leadership? That's not leadership at all. So I salute her and all the young people who put themselves on the line.But I invite them, you know, it's not enough. You've got to then — and I said this during the course of the election where I hope we created a lot of new voters. And I think environment, specifically climate crisis, became a real voting issue this year, just as it was back in 1970 when we created the EPA and the Clean Air Act and a host of things. And it proves that that kind of activism is necessary. And I hope we're going to keep young people at the table here and finish the job, that's the key now.AG: Yeah, I couldn't agree more. And another big movement that's having an impact is the environmental justice movement. You referred to it earlier. And I'm so glad that President Biden is putting environmental justice at the heart of his climate agenda. It might be good if I could ask you to just take a moment and tell people why that is such an important part of this issue.JK: Well, I think it's important part of this issue for many reasons, the most basic is just moral, you know, what is morally right. And how do you redress a wrong that has for too many years held people back, killed people by virtue of disease or other things, and resulted in a basic inequality and unfairness in society. And I think you share a feeling, as I do, Al, that the fabric of a nation is built around certain organizational principles. And if you're holding yourselves out as a nation to be one thing, i.e. equal opportunity and fairness and all people created equal, and equal rights and so forth, if that's what you hold out there and it isn't there, eventually you get such a cynicism and such a backlash built up into your society that it doesn't hold together. To some degree, that is what we're seeing around the world today, is this nationalistic populism that is driven by this heightened inequality that has come through globalization that has mostly enriched already fairly well-off folks. And so if it's the upper one percent that's getting all the benefits and the rest of the world struggling to survive and they also have COVID, and then you tell them we've got to do this or that in terms of climate, you're walking on very thin ice in terms of that sacred relationship between government and the people who are governed.It's not just an American phenomenon. You see it in Europe. You see it in alternative movements in various countries. And I think it is the great task of our generation not only to deal with climate, but to restore a sense of fairness to our economies, to our societies, to our world. And that is part of this battle, I think.AG: Yeah, I agree. And another common source of opposition to what governments are doing now has to do with the fear, both in the US and elsewhere, on the part of some, that jobs might be lost in this transition toward a green economy. You and I both know that there are a lot of jobs that can be created. But let me put the question to you. How can we approach this green transition in a way that lifts everyone up?JK: That is one of the most important things that we need to do, Al. And we can't lie to people. We can't say that some of the dislocation doesn't mean that a job that exists today might not be the same job in the future and that that person has to go through a process of getting there. And we need to make certain that nobody's abandoned. We need to make certain that there are real mechanisms in place to help folks be able to transition. And I just spoke the other day with Richie Trumka, the head of the American Federation of Labor, and he's been very focused on this. And we agreed to try to work through how do we integrate that into this transitional process so that we're guaranteeing that you don't abandon people.Now, one of the things we need to do is go to the places where there have been changes and there will be change. Southeastern Ohio, Kentucky, West Virginia. You know, if the marketplace is making the decision and it's — by the way, it's not government policy, it is the marketplace that has decided, in America at least, not to be building a new coal-fired plant. So where does that miner, or where does that person who worked in that supply chain go? We have to make sure that the new companies, that the new jobs are actually going into those communities that the coal community, the coal country, as we call it, in America, is actually being immediately and directly and realistically addressed in this to make sure that people are not abandoned and left behind. That is possible. That is doable. Historically, unfortunately, there have been too many words and not enough actual — not enough actually implementation and process. I think that can change. And I'm going to do everything possible in my ability to make sure that we do change it.AG: Well, that's great. And another part of the context within which you are taking on this enormous challenge is the COVID pandemic, which has exposed the cost of ignoring pre-existing systemic risks, inequalities and sustainability. And now as we start to come out of this pandemic, how can we avoid sleepwalking back into old habits?JK: Boy, that's probably the toughest of all. I mean, there's a natural proclivity for people sometimes to just choose the easiest way. And clearly, some people already have and will resort to that. I think the key will be in President Biden's proposal for the build back, which will actually fight hard to direct funds to the investments and to the sectors where we want to see a responsible build back. There’s another aspect, and I think that can be done, Al, I really feel that.For instance, someone who's making a car today in South Carolina, where BMW has plants, and just to pick one place or Detroit, GM is obviously going to make this shift, they just announced it. The people building the car today are still going to have to put wheels on a car, build the car, put the seats in, do everything else. It's just that instead of an internal combustion engine, they can be quickly trained to be able to put the platform in for the batteries and the engines themselves, etc, that will drive the car, the motors, that's one way of dealing.Others are that there's new work in some ways. We have to lay transmission lines in America. We do not have a grid in the United States, as you know. We have at east coast, west coast. Texas has its own grid, north part of America, but there's a huge hole in the country. You can't send energy efficiently from one place to another. We could lower prices for people and create more jobs in the build-out of all of that kind of new infrastructure. Not to mention the things that you and I, you know, there are going to be things that we can't name today, some negative-emissions technology that's going to grab CO2 out of the atmosphere and do something with it, like in Iceland, where they put it into the rock, mix it with liquid and it turns into stone. I mean, there are all kinds of different things people are exploring. Those are new jobs.AG: I just want to say, since we've come to the end of our time for this conversation, thank you again for taking on this crucial challenge on behalf of the United States of America and enabling the US to restore its traditional role in trying to bring the world together. And I know that everybody watching and listening to this conversation sends you their best wishes and hopes for all the success possible in this new work, John. Thank you so much for joining TED Countdown, and we wish you the very best.JK: Can I reciprocate for a minute? First of all, I want to thank you for your extraordinary leadership for years, I can remember when you were leading us in the Senate on this, and you've done so much since. And I am personally delighted to be working with you on this again and look forward to the next months and together with a lot of other folks. Let's get this done. For as long as we’ve had language, some people have tried to control it. And some of the most frequent targets of this communication regulation are the ums, ers, and likes that pepper our conversations. Ancient Greek and Latin texts warned against speaking with hesitation, modern schools have tried to ban the offending terms, and renowned linguist Noam Chomsky dismissed these expressions as “errors” irrelevant to language. Historically, these speech components had been lumped into the broader bucket of “disfluencies”— linguistic fillers which distract from useful speech. However, none of this controversy has made these so-called disfluencies less common. They continue to occur roughly 2 to 3 times per minute in natural speech. And different versions of them can be found in almost every language, including sign language. So are ums and uhs just a habit we can’t break? Or is there more to them than meets the ear?To answer this question, it helps to compare these speech components to other words we use in everyday life. While a written word might have multiple definitions, we can usually determine its intended meaning through context. In speech however, a word can take on additional layers of meaning. Tone of voice, the relationship between speakers, and expectations of where a conversation will go can imbue even words that seem like filler with vital information.This is where “um” and “uh” come in. Or “eh” and “ehm,” “tutoa” and “öö,” “eto” and “ano.” Linguists call these filled pauses, which are a kind of hesitation Wh phenomenon. And these seemingly insignificant interruptions are actually quite y do meaningful in spoken communication. For example, while a silent pause might we, be interpreted as a sign for others to start speaking, a filled pause can signal like, that you’re not finished yet. Hesitation phenomena can buy time for your speech hesi to catch up with your thoughts, or to fish out the right word for a situation. And tate they don’t just benefit the speaker— a filled pause lets your listeners know an whe important word is on the way. Linguists have even found that people are more n likely to remember a word if it comes after a hesitation.Hesitation phenomena we, aren’t the only parts of speech that take on new meaning during dialogue. Words um, and phrases such as “like,” “well” or “you know” function as discourse markers, spe ignoring their literal meaning to convey something about the sentence in which ak? they appear. Discourse markers direct the flow of conversation, and some studies suggest that conscientious speakers use more of these phrases to ensure everyone is being heard and understood. For example, starting a sentence with “Look...” can indicate your attitude and help you gauge the listener’s agreement. “I mean” can signal that you’re about to elaborate on something. And the dreaded “like” can perform many functions, such as establishing a loose connection between thoughts, or introducing someone else's words or actions. These markers give people a real-time view into your thought process and help listeners follow, interpret, and predict what you’re trying to say.Discourse markers and hesitation phenomena aren’t just useful for understanding language— they help us learn it too. In 2011, a study showed toddlers common and uncommon objects alongside a recording referring to one of the items. When a later recording asked them to identify the uncommon object, toddlers performed better if that instruction contained a filled pause. This may mean that filled pauses cue toddlers to expect novel words, and help them connect new words to new objects. For adolescents and adults learning a second language, filled pauses smooth out awkward early conversations. And once they’re more confident, the second-language learner can signal their newfound fluency by using the appropriate hesitation phenomenon. Because, contrary to popular belief, the use of filled pauses doesn't decrease with mastery of a language.Just because hesitation phenomena and discourse markers are a natural part of communication doesn’t mean they’re always appropriate. Outside of writing dialogue, they serve no purpose in most formal writing. And in some contexts, the stigma these social cues carry can work against the speaker. But in most conversations, these seemingly senseless sounds can convey a world of meaning. Med Like many people who have been fortunate enough to be more or less healthy, I itati spent most of my life never thinking much about my body. Something that I ons relied on to get me around, not to mind the occasional bash and not to complain on too much if I wasn't getting enough rest.But that all changed for me when I the became pregnant. Suddenly, my body was this machine performing an inte incredible task. That was something that I had to take notice of and look after, so rsec that it could do its job.I've been a documentary photographer for nearly 20 years tion now but I never turned the camera on myself until that time. And then suddenly, I of found myself fascinated by how we feel about our bodies and how we express hu strength or fear, courage or shyness in the way we carry ourselves. I spent man several years making work that examined the relationship that we have to our ity bodies as humans. More recently, though, I've been exploring a new frontier in and the human body. A transformation of bodies with technology.As humans evolve tech along with technology, and the lines between the two become increasingly nol blurred, I set out to document our evolution into a new kind of human and to play ogy with that age-old question: Can we ever see a real humanness in machines?Sight is perhaps the most personal and intimate of our senses. Classically called the window to the soul. We connect with each other, recognize each other and communicate with each other through our eyes. If we lose an eye, we might wear a dummy replacement so that our face resembles what it did before. Filmmaker Rob Spence took that a step further when he installed a video camera in his replacement eye so that he could record his vision. Rob is part of a known network of cyborgs and he told me that he found it curious when he started to receive hate mail from people who felt threatened by him having this extra ability. Was his right to change his body less important than their right to their privacy?So as I photographed Rob, he filmed me using the camera in his eye, and we recorded it on a special receiver. But perhaps in response to the speed with which we all move and make images these days I wanted to make this work in a way that was slow and purposeful. Most of these images are shot on a large-format camera. These are big and cumbersome, taking only one frame at a time before you have to change the film. To check the focus, you have to put your head under a black cloth and use a magnifying glass. So as I photographed Rob using this very old technology, he filmed me using the camera in his eye, somewhat the opposite end of the technology spectrum.But I wanted to delve deeper and explore more of what it could mean to lose a part of ourselves and replace it with technology. At MIT Media Lab they are doing some of the most cutting-edge work in biomechatronics, developing motorized limbs for amputees. Originally set up by Hugh Herr, a double amputee who was able to develop and test the equipment on himself. He went on to create a set of legs that can walk, run and even jump without seeming to be mechanical at all. The gait more closely resembles that of a human foot and leg because the motor gives the wearer a push off the floor to move the foot forwards from the ankle.The technology here, continuing to be developed by Matt Carney and his colleagues at MIT, is really quite impressive, with the prosthesis connecting directly into the amputee's bone for stability, and sensors reading pulses from the amputee's muscles to tell the limb how to move. Ultimately, the wearer should be able to think about moving their foot and the foot would move. They're impressive to look at by themselves. But of course, the prostheses don't move on their own.In order to show their relationship to humans, I wanted to show how they enable amputees to move with ease and fluidity. But how do you photograph gait? At this point, I was inspired by the work and photographs of Eadweard Muybridge, who is famous for his series of images of a running horse, made in 1878, to prove that there's a moment when all four of the horse's feet are off the ground at the same time. He went on to make hundreds of series of images of animals and humans in motion. It was groundbreaking work and gave us one of the first opportunities to study the anatomy of motion. So I wanted to try and create similar kinds of motion studies of amputees walking, running, jumping, using this technology, and to think of them as motion studies of an enhanced human motion.One of the things I learned at MIT was the incredible importance of balance and the complex system of reactions and muscles that enable us to stand on two feet. Those of us with children will remember with fond nostalgia the moment our kids take their first steps. But what we think of as endearing is actually an incredible feat of balance and counterbalance. It can be quite daunting. This is my daughter Lorelei standing for the first time without any support. It lasted only a few seconds.Dance, in particular, is all about balance and mastering the fluidity of movement. Pollyanna here lost her leg in an accident when she was just two years old. She's learned to dance with the aid of a blade prosthesis and she now competes in a class alongside nonamputees. But the skill of moving around on two legs and navigating often uneven ground is incredibly difficult to replicate.Over at Munich's technical university they've developed LOLA, a biped humanoid robot that can move on two legs and make her way around a series of obstacles. As she strides along, she looks powerful and impressive. But her movement is also somewhat clunky and mechanical and not as spontaneous or unpredictable as that of humans. At the end of it all, when she switched off, she hung down on her cables and looked kind of forlorn. And in that moment, I saw her as more human than I had done when she was walking along. I felt almost sorry that she had been switched off. Her exterior might be cold and mechanical, but when vulnerable, she looked more real to me.Alex Lewis is a quadruple amputee who lost his limbs and part of his face when he fell ill with strep A. One of the most inspiring people I have ever met. His journey to recovery has been an incredibly tough one. He now has a chip in his arm to open his front door, a set of mechanical arms, and a handcycle to get around. Depending on what he is doing, be it throwing a ball for the dog, riding his handcycle, or even canoeing, he has a different set of hands that he attach to the end of his arms.It's been a very tough journey, but the hardships he's faced have given Alex a superhuman ambition. He genuinely told me that his ordeal is the best thing that ever happened to him. He now goes on expeditions, climbing mountains in Africa, he's planning to cycle across Mongolia, and he works with London’s Imperial College, helping to develop a motorized hand, much like the legs they are developing at MIT. He may be less physically able than before, but understanding his weaknesses has made Alex emotionally very strong and opened up a world of opportunity for him. It made me realize that our emotions and understanding the limits of our physicality are also a huge part of what makes us strong.In Osaka I meet professor Ishiguro, who makes robots with uncannily human faces and expressions. First, I meet Geminoid, the robot he created in his own likeness. On the grid here you can see three pictures of the robot, one of the professor. Can you tell which is which?One of his more recent creations is Ibuki, a robot made to look like a ten-year-old boy, who can wave and show a range of facial expressions. In those expressions, I saw a certain vulnerability that made Ibuki feel very real to me. When he was angry or sad, it resonated. And when he smiled, I wanted to smile back. I feel I was drawn to Ibuki as I might have been to a real child. And at the end of it all, I felt I wanted to thank him or reach out and shake his hand. So if understanding the limits of our physicality can help to make us stronger, then seeing the vulnerability in Ibuki's expressions made him feel more human to me.So where do we go from here? In Tokyo, I meet professor Takeuchi who's developed a form of synthetic muscle that can respond to an electric pulse and expand or contract just like a real muscle. As it does so, the little limb here moves back and forth. Now this sample is only tiny, but imagine the possibilities if synthetic limbs could be made out of this. And what if that could be combined with the technology that reads nerve pulses from the end of an amputee's limb? Perhaps it could respond to touch and feel something hot or sharp, sending a message back up to our brains, just like it does in our body. Understanding those vulnerabilities would make the technology stronger too.Throughout the course of making this work, I've met some incredible people, both using and creating technology. I've seen crazy possibilities for how we'll mend and enhance our bodies. But I've also smiled at a robot, seen a young girl leap through the air on a blade and shaken the hand of a man with no hands who towers emotionally above us all. I'm left in awe of the complexity of the human body.But I also feel that it's not just our bodies, bionics or not, that make us strong, but our emotions and understanding our weaknesses. But I'd like to think of these works as studies, something that we can come back to and carefully observe. A point in our evolution before time runs away with us all.Thank you. Ho "O for a Muse of fire, that would ascend the brightest heaven of invention, a w kingdom for a stage, princes to act and monarchs to behold the swelling scene!” thea Though, to be totally honest, right now, I'd settle for a real school day, a night out ter and a hug from a friend. I do have to admit that Wrigley Field does make a pretty wea awesome stage, though.The words that I spoke at the beginning, "O for a Muse ther of fire," et cetera, are Shakespeare's. He wrote them as the opening to his play s "Henry V," and they're are also quite likely the first words ever spoken on the war stage of the Globe Theater in London, when it opened in 1599. The Globe would s, go on to become the home for most of Shakespeare's work, and from what I outl hear, that Shakespeare guy was pretty popular. But despite his popularity, just asts four years later, in 1603, The Globe would close for an extended period of time emp in order to prevent the spreading and resurgence of the bubonic plague. In fact, ires from 1603 to 1613, all of the theaters in London were closed on and off again for and an astonishing 78 months.Here in Chicago, in 2016, new theaters were opening sur as well. The Steppenwolf had just opened its 1,700 theater space. The vive Goodman, down in the Loop, had just opened its new Center for Education and s Engagement. And the Chicago Shakespeare Theater had just started pan construction on its newest theater space, The Yard. Today, all of those theaters, dem as well as the homes of over 250 other theater companies across Chicago, are ics closed due to COVID-19. From Broadway to LA, theaters are dark, and we don't know when or if the lights are ever going to come on again. That means that tens of thousands of theater artists are out of work, from actors and directors to stage managers, set builders, costume designers ... It's not like it's an easy time to go wait tables. It's a hard time for the theater, and it's a hard time for the world.But while theaters may be dark, theater as an art form has the potential to shine a light on how we can process and use this time apart to build a brighter, more equitable, healthier future together. Theater is the oldest art form we humans have. We know that the Greeks were writing plays as early as the fifth century BC, but theater goes back before that. It goes back before we learned to write, to call-and-response around fires. and — who knows? — maybe before we learn to build fire itself. Theater has outlasted empires, weathered wars and survived plagues. In the early 1600s, theaters were closed over 60 percent of the time in London, and that's still looked at as one of the most fertile and innovative periods of time in Western theater history. The plays that were written then are still performed today over 400 years later.Unfortunately, in the early 1600s, a different plague was making its way across the ocean, and it hit the shores of what would be called "America" in 1619, when the first slave ships landed in Jamestown, Virginia. Racism is an ongoing plague in America. But many of us in the theater like to think we're not infected or that we are at worst asymptomatic. But the truth is, our symptoms have been glaring onstage and off. We have the opportunity to use this intermission caused by one plague to work to cure another. We can champion a theater that marches, protests, burns, builds. We can reimagine the way our theaters and institutions work to make them more reflective and just. We can make this one of the most innovative and transformative periods of time in Western theater history, one that we are still learning about and celebrating 400 years from now.What we embody in the theater can be embodied in the world. Why? Because theater is an essential service. And what I mean by that is that theater is in service to that which is essential about ourselves: love, anger, rage, joy, despair, hope. Theater not only shows us the breadth and depth of human emotions, it allows us to experience catharsis, to feel our feelings and rather than ignore or compartmentalize them, move through them to discover what's on the other side.Now, many art forms connect us to our emotions, but what makes the theater unique is that it reveals us to ourselves onstage so that we can see that our lives are about our relationships and our connections to others — to our parents, to our children, to our teachers, to our tormentors, to our lovers, to our friends. What we do when we engage with theater is we experience in real time, in real space, those relationships and connections changing in the present — the relationships between characters onstage, yes, but also the relationships between characters and the audience and the relationships between audience members themselves.We go to the theater because we seek connection. And when we're in the theater, our hearts beat as one. That's not a metaphor. Our hearts race together, they're soothed together, we breathe together. Ay, there's the rub. Who knows when we're going to be able to be together again in the same space, breathing in the same air, breathing in the same experience? Who knows when we're going to want to be? We are holding our breath.Luckily, theater doesn't just have to happen in theaters. As theater practitioners, we know some of the most important work we do happens offstage, in rehearsal spaces, garage spaces, studio apartments. At the beginning of this talk, I wished for a kingdom for a stage, princes to act and monarchs to watch the show. But the truth is, none of that is necessary. In fact, some of the most important theater I make happens on Monday mornings in an empty hospital meeting room with just a handful of folks, and only two of us are theater artists. The Memory Ensemble, as we call ourselves, is a collaboration between the Lookingglass Theatre and Northwestern's Center for Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer's Disease Research.We begin each session with a mantra: "I am a creative person. When I feel anxious or uncertain, I can stop, breathe, observe and use my imagination." Anyone else feeling anxious or uncertain right now? Let's say it together. I am a creative person. When I feel anxious or uncertain, I can stop, breathe, observe and use my imagination.Let's look at the first part of that statement: I am a creative person. Many of us have been taught that creativity is a talent only some of us have, a skill reserved for artists, inventors, big thinkers, that it's not something for regular people with quote, unquote real jobs. But that's not true. All humans are innately creative. It's part of what makes us human. And if there was ever a time for us to exercise our creativity, it's now — not to solve or fix our anxiety and uncertainty, but to learn from it and to move through it. So the first step is to stop. That's harder than it sounds; busy is a coping mechanism that we use to deal with our anxiety and uncertainty, and our society is addicted to it. So we find ourselves making all the TikToks, baking all the bread, taking all the Zoom meetings. Maybe you've even seen that meme about how Shakespeare wrote "King Lear" during his pandemic, which I think is supposed to inspire us, but instead just makes us feel guilty that we're not creating our own masterpieces right now, you know, in addition to taking care of our children or our parents or our students, our patients, our clients, our customers, our friends, ourselves. So A, screw that guilt; and B, that's, like, the opposite of what "King Lear" is actually about. Towards the end of Lear, one of the main characters, Edgar, says, "The weight of this sad time we must obey; speak what we feel, not what we ought to say." The lesson of Lear is not about pushing or producing or doing what you think you should do. The lesson of Lear is about stopping and taking the time to appreciate who and what you have in your life and discover who you want to be while you have it.We're at an intermission, and intermissions are important, because they give ourselves the opportunity to take care of ourselves physically and emotionally: go to the bathroom, get a snack, get a drink and also take a moment to feel the weight of what just happened onstage, maybe begin to process any emotions that that brought up. I reached out to my community of artists, and I asked them what plays were speaking to them and helping them process this time. Many of the characters in the plays they sent don't share my lived experience. And I think their words are important to hear.My friend Jeremy sent me a monologue by Sarah Ruhl from her "Melancholy Play." In it, the character is talking about how she's feeling, and she says, "It's this feeling that you want to love strangers, that you want to kiss the man at the post office or the woman at the dry cleaners. You want to wrap your arms around life, life itself, but you can't. And so this feeling wells up in you, and there's nowhere to put this great happiness, and you're floating, and then you fall. And you, you feel unbearably sad, and you have to go lie down on the couch." I've felt that monologue a lot during this pandemic. Sometimes I feel this great happiness, and sometimes I have to go lie down on the couch. My theater practice teaches me that both are OK. We stop so that we can feel our feelings instead of covering them.Next, we breathe. When we inhale, we give ourselves the opportunity to breathe in the present moment and be aware of what's happening right now inside of us, as well as outside of us. When we exhale, we allow ourselves to release the moment so that we can be present for the next one and the next one and the next one. When we feel anxious or uncertain, we tend to hold our breath. We're scared about what's going to happen next, and so we hold onto what's happening right now, which prevents movement, which keeps us stuck. Far from helping us, holding our breath holds us back. So we stop. We breathe.And then we observe: What's happening around us? How do we feel about that? My friends Greg and Kanisha told me that I should watch the play "Pipeline" by Dominique Morisseau. At the beginning of the play, maybe the character has been onstage for a minute. Omari turns to his girlfriend, and he says that he’s just, like modestly, without intentions, just observing. And his girlfriend says, "What you gotta be observing for?" And Omari says, "To take in my surroundings, learn the world, not be just tied up in my own existence and nothing else." That observation is the key to unlocking our empathy and our curiosity about the world and igniting our imagination about how we can make it even better.My friend Jazmin introduced me to the play "Marisol" by José Rivera. And in it, the guardian angel is talking to Marisol, and she says, "I don't expect you to understand the political ins and outs of what's going on. But you have eyes. You've asked me questions about children and water and war and the moon, questions I've been asking myself for a thousand years. The universal body is sick, Marisol. The constellations are wasting away. The nauseous stars are full of blisters and sores. The infected earth is running a temperature and everywhere, the universal mind is wracked with amnesia, boredom and neurotic obsessions." Sound familiar? We stop. We breathe. We observe. And we use our observations to imagine a world that is fiercer, braver, more beautiful. We use our imaginations to create something new based on our connections to the world and ourselves.One of the things that I know is this: there's always been a certain amount of uncertainty in the theater, but this is the most anxious and uncertain we've ever been in my lifetime. In order to move forward, there's going to have to be a lot of change. Luckily, all great theater provides the opportunity for transformation. We can use this intermission to stop, breathe, observe, and use our imaginations to create a more beautiful world onstage and off, one that is more equitable, more reflective and more just. As Prior says at the end of Tony Kushner’s masterpiece about the AIDS epidemic, "Angels in America," "I'm almost done. The fountain's not flowing now, they turn it off in the winter, ice in the pipes. But in the summer, it is a sight to see. I want to be here to see it. I plan to be. I hope to be. This disease will be the end of many of us, but not nearly all, and the dead will be commemorated, and they will struggle on with the living, and we are not going away. We won't die secret deaths anymore. The world only spins forward. We will be citizens. The time has come. Bye, now. You are fabulous creatures, each and every one. And I bless you: more life. The great work begins."The theater has weathered wars, outlasted empires and survived plagues. It'll continue. I don't know how or when or what it'll look like, but it will. And so will we, as long as we do the essential work of staying connected to that which is essential about ourselves, our communities and our world. The great work begins.Thank you. 3 Worldwide, online retail has been on the rise. In 2019 alone, shoppers spent sne nearly 3.8 trillion dollars online. And to keep those figures climbing, some aky companies are pulling out all of the stops to hold your attention and to keep you tacti spending. To help you regain control of your shopping environment, I'll identify cs three of their tactics and share three tips to counteract them.[Your Money and that Your Mind with Wendy De La Rosa]One online gimmick that sites use is web gamification, and this is where websites use game design elements to get you to site spend more time and more money on their sites. Now, some sites have a virtual s wheel for you to spin to get a chance at that day's discounts. Others, they let you use accrue loyalty points based on how you interact with the site. And that kind of to gamification, in my mind, is really dangerous.In one classic experiment, lab rats mak were more captivated by the random chance of pushing a lever and receiving a e food pellet than by the certainty of a fixed food schedule. And we as humans are you just the same.We're enticed by the chance to win. Just like at a slot machine in spe Vegas, you increase your dopamine levels every time you try your luck. So my nd tip here is to avoid temptation altogether by unsubscribing from online shopping emails. You can't buy what you can't see, and these emails are constant reminders that are intended to lure us back to the site with its gamifications and its gimmick, when you'd otherwise not be thinking about them.A second tactic online retailers use is scarcity. Many sites now tell you how many other customers are also viewing the same item, making it seem like that item is very popular, and it's likely to go quickly. Similarly, websites will use a timer for your basket, pushing and pushing the message that these potential items won't be available for long. Research shows that the perceptions of a product's scarcity can increase its value in the eye of the shopper and increase a shopper's willingness to buy. Scarcity can also make people feel more competitive and selfish as well.So here's my tip to help you combat scarcity: when scarcity is tempting you, back away from the website, back away from the car and sleep on it. That can help you decide whether or not you really need whatever it is that you were planning on buying. Leave the site for at least an entire day and see if you're still itching for the item. This approach works best if you use an incognito browser so you won't be haunted by the ads for the product everywhere you go.The third tactic that companies use is to allow you to pay in installments. A number of e-commerce sites have adopted payment schemes that will let you order an item and pay for it later. Now, installment plans are useful if you're replacing a large, expensive item, like a broken refrigerator. But I think these installment plans veer towards predatory when you're purchasing less urgent, less important items. Looking at small monthly payments psychologically decreases the cost of those new sneakers or new pair of jeans. And that mental trickery means that you're more likely to buy additional items. And while it may feel different from a credit card, you still owe these companies money. So at the end of the day, you're still taking on debt and potentially adding late fees and interest, and you may find yourself owing a lot more than the original sticker value for those jeans.So here's my third and final tip: above all else, do not use these payment installment plans. If you want an actual discount, there are browser plug-ins you can use that will help you find the best deals.Online retail has made shopping incredibly convenient, but not every day needs to feel as overwhelming as Black Friday. By putting these tips into practice, you can tune out some of the tricks and the gimmicks, and once again, regain control of your shopping environment. Two frogs are minding their own business in the swamp when WHAM— they’re kidnapped.They come to in a kitchen, captives of a menacing chef. He boils up a pot of water and lobs one of the frogs in. But it’s having none of this. The second its toes hit the scalding water it jumps right out the window.The chef refills the pot, but this time he doesn’t turn on the heat. He plops the second frog in, and this frog’s okay with that. The chef turns the heat on, very low, and the temperature of water slowly rises. So slowly that the frog doesn’t notice. In fact, it basks in the balmy water. Only when the surface begins to bubble does the frog realize: it’s toast.What’s funny about this parable is that it’s not scientifically true... for frogs. In reality, a frog will detect slowly heating water and leap to safety. Humans, on the other hand, are a different story. We’re perfectly happy to sit in the pot and slowly turn up the heat, all the while insisting it isn’t our hand on the dial, arguing about whether we can trust thermometers, and questioning— even if they’re right, does it matter?It does.Since 1850, global average temperatures have risen by 1 degree Celsius. That may not sound like a lot, but it is.Why? 1 degree is an average. Many places have already gotten much warmer than that. Some places in the Arctic have already warmed 4 degrees. If global average temperatures increase 1 more degree, the coldest nights in the Arctic might get 10 degrees warmer. The warmest days in Mumbai might get 5 degrees hotter.So how did we get here?Almost everything that makes modern life possible relies on fossil fuels: coal, oil, and gas full of carbon from ancient organic matter. When we burn fossil fuels, we release carbon dioxide that builds up in our atmosphere, where it remains for hundreds or even thousands of years, letting heat in, but not out.The heat comes from sunlight, The which passes through the atmosphere to Earth, where it gets absorbed and "my warms everything up. Warm objects emit infrared radiation, which should pass th" back out into space, because most atmospheric gases don’t absorb it. But of greenhouse gases— carbon dioxide and methane— do absorb infrared the wavelengths. So when we add more of those gases to the atmosphere, less boili heat makes it back out to space, and our planet warms up.If we keep emitting ng greenhouse gases at our current pace, scientists predict temperatures will rise 4 frog degrees from their pre-industrial levels by 2100. They’ve identified 1.5 degrees of warming— global averages half a degree warmer than today’s— as a threshold beyond which the negative impacts of climate change will become increasingly severe. To keep from crossing that threshold, we need to get our greenhouse gas emissions down to zero as fast as possible.Or rather, we have to get emissions down to what's called net zero, meaning we may still be putting some greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, but we take out as much as we put in.This doesn’t mean we can just keep emitting and sequester all that carbon— we couldn’t keep up with our emissions through natural methods, and technological solutions would be prohibitively expensive and require huge amounts of permanent storage. Instead, while we switch from coal, oil, and natural gas to clean energy and fuels, which will take time, we can mitigate the damage by removing carbon from the atmosphere.Jumping out of the proverbial pot isn’t an option, but we can do something the frogs can’t: reach over, and turn down the heat. I used to love waking up at exactly 7:00am. When I lived in San Francisco, I would wake up right at 7:00am and immediately go to my favorite coffee shop. It was my favorite coffee shop, because it was the best coffee shop. I had done the research, it was five stars, it was great. And I would drink my coffee and get onto my bicycle and ride into work. And I had optimized my schedule to be perfect. I was constantly, like, shaving off one or two seconds making it slightly faster so I could get into work faster.I was working as a software engineer at Google, and in a lot of ways, this was my dream job. It felt like this was the thing that the rest of my life was leading up towards. I'd always wanted to work in software and I was finally doing it. And I was living in San Francisco, which is a city that I love, surrounded by people who were like me. And every part of my life I let was perfectly tailored to my interests, the things that I wanted to do. And I loved algo it.So one day I was at work and I started to read this paper, a computer science rith research paper about predictive analytics. And the gist of the paper was that if ms you take someone's GPS trace, like the listing of all the places that they've been ran in the past month or so, and you feed it into a machine-learning algorithm, you do can predict with fairly high accuracy where they're going to be on the following miz day. And I thought this was kind of cool. And I was thinking, like, what would e happen if you put my GPS trace into the algorithm? What would come out the my other end?So I was talking with my friend Kelly, and we were planning life something to do after work that day. And I got onto Yelp and found this really for great bar that had just opened up. And I was about to suggest that we go to this two bar when I stopped. And I started thinking about that algorithm again. And I year started thinking, wait a second, isn't this bar exactly where that algorithm would s guess that I was going to go this evening? And that was kind of weird. Because I thought that I ... where was I in that? I know that I was the one making the choice, right? But how did the computer know about that? So that was a little disturbing.And since I'm an engineer, whenever I have a problem like this, my instinct is to fix it, to make something that solves the problem. And so I decided to make an app that would help me choose where to go on this evening. And so the way that it works is that the app looks at all the places that are on Google maps in the city of San Francisco, and then chooses one at random. And then it calls an Uber. And that car shows up at your location and takes you to that random place. It tells the Uber driver where the random place is, but tells you nothing. And so it's a big surprise when you arrive.(Laughter)And so I texted Kelly and I said, "We should do this." We met up and pressed the button. And suddenly, miraculously, there was an Uber driver at my apartment door. So we got in and very quickly started heading to a part of San Francisco that neither of us really knew. It was a part of town that we just had never been in before. And when the driver told us we had reached our destination, we thought it must have been a joke. We showed up in front of this austere brick building with a wrought iron fence in front of it, and a sign that said the words San Francisco General Hospital, Psychiatric Emergency Center.(Laughter)Which, maybe that's pretty appropriate, I don't know.(Laughter)But we thought it was funny. But it was also exhilarating because here we were, in this place that we never would have gone to otherwise, doing something really different on a Friday night.(Laughter)And I was hooked, I started using this app to go to all different places in San Francisco. I went to museums randomly, random grocery stores, random bars, random bowling alleys, random florists. And I started discovering that there was an entire side to San Francisco that I had been ignoring because of my preference.And then I started thinking, how else can I apply this concept to my life? And so I started building other experiments that involved randomness. I made a random YouTube video generator, a random schedule generator, a random diet club that would randomly eliminate a food from my diet each week.(Laughter)And it's cumulative, so eventually you just can't eat.(Laughter)Random tattoo generator, a random Spotify playlist, random podcast, a printer that prints out random suggestions of things to do.(Laughter)A random Facebook event generator. And the way that this one works is that in a city like Vienna on a given day, there are hundreds of Facebook events — public Facebook events — that are going on. So it would choose one at random and say, this is your plan for tonight. And so I ended up showing —(Laughter)And so I'd show up at events like Joe's birthday, the eighth grade band recital, chess club, truck drivers school. And it was really interesting because these were communities that I knew nothing about but were having amazing events to talk about things that they cared about. And there I was.After a while, I had the opportunity to transition my work into freelance, which gave me a lot more flexibility about where I lived. And so I decided, you know, what if I could let the computer decide what part of the world I lived in? And so I wrote a program that figured out every city that it was possible for me to live in, given my budget, and then chose one at random. And I started living this way and it sent me all over the world. Taipei, Taiwan, Mumbai, India, Dubai. Even places that for an American are really off the beaten path, like Essen, Germany and Gortina, Slovenia. And every time I would go to a new city, I would do the same sort of stuff I was doing in San Francisco, go to random events, meet random people. And I'd live there for two to three months and then ask the computer again for the next location. I did this for two years.Paradoxically, giving up control to this machine actually made me feel more free than when I was making choices, because I discovered that ... My preference had blinded me from the complexity and the richness of the world. And following the computer gave me the courage to live outside of my comfort zone, to discover parts of the human experience that I ignored because they were too different or not for me.I ended up in Mumbai, India for a while, and I was going to a lot of Facebook events when I was there. And one day, the computer sent me to this yoga class and I'm really bad at yoga, but I went anyway. I found myself descending into a downward dog when I had a revelation. Because I was thinking about, you know, this random stuff is really freeing, it's sort of putting me outside of my bubble, my comfort zone. But really how random is it? Because this was not my first yoga event in Mumbai. In fact, it was my third that week.(Laughter)And if you think about it, it's not surprising that you see patterns like this. Because I was choosing randomly from a list of things that was decidedly not random. The list of Facebook events that are happening in a city is very influenced by the things that are going on in a city like that. And if you think about it, every time you make a choice, you're not just making it on your own. You're selecting from a list, a menu of choices that was designed by someone or something else. And whatever freedom that you have in that choice is necessarily constrained by social structures, customs and history that provide the context for that selection.So initially, I thought of this as a way of getting outside of my bubble. As, you know, transcending myself, my preference. But eventually I started to think about it differently. I started to think about it as a way of taking a photograph. When I was in a place like Mumbai, it was more likely that I would show up at a yoga event. But if I was in Vienna, maybe a music event would be more likely. Every time that I was choosing randomly in a city, what I was doing was making an inquiry, asking, "Mumbai, tell me what you're about." And then the answer would tell me something about the structure of that city and my relationship to it and its relationship with the rest of the world.And so I ... I had, like, a really tidy ending for this previously. And as I was coming up here, I decided to scrap it, because ... You know, I think that, like, a problem with TED Talks often is that they wrap up in a tidy bow and then you can go away without really thinking about it. You can sort of just — It feels like everything is OK at the end. And I think ... In the world that we're living in, there are a lot of real problems. And I think that these questions of algorithmic control play a lot into them. We're talking right now about the role that Facebook had in the American election. There are a lot of questions about the ways that these algorithms are controlling our lives. And so, I don't know, I don't know what I'm saying and I don't have, like, a very clear conclusion. But I would just encourage you to try to be experimental when it comes to interacting with these algorithms. Because if you just do the defaults, follow your preference, go in the direction that everything else is going, it's really easy to get caught in a place where you can be controlled. And I think that's it.Thank you.(Applause) As the space telescope prepares to snap a photo, the light of the nearby star blocks its view. But the telescope has a trick up its sleeve: a massive shield to block the glare. This starshade has a diameter of about 35 meters— that folds down to just under 2.5 meters, small enough to carry on the end of a rocket. Its compact design is based on an ancient art form.Origami, which literally translates to “folding paper,” is a Japanese practice dating back to at least the 17th century. In origami, the same simple concepts yield everything from a paper crane with about 20 steps, to this dragon with over 1,000 steps, to a starshade. A single, traditionally square sheet of paper can be transformed into almost any shape, purely by folding. Unfold that sheet, and there’s a pattern of lines, each of which represents a concave valley fold or a convex mountain fold.Origami artists arrange these folds to create crease patterns, which serve as blueprints for their designs. Though most origami models are three dimensional, their crease patterns are usually designed to fold flat without introducing any new creases or cutting the paper. The mathematical rules behind flat-foldable crease patterns are much simpler than those behind 3D crease patterns— it’s easier to create an abstract 2D design and then shape it into a 3D form.There are four rules that any flat-foldable crease pattern must obey.First, the crease pattern must be twoThe colorable— meaning the areas between creases can be filled with two colors so une that areas of the same color never touch.Add another crease here, and the xpe crease pattern no longer displays two-colorability.Second, the number of cted mountain and valley folds at any interior vertex must differ by exactly two— like mat the three valley folds and one mountain fold that meet here.Here’s a closer look h of at what happens when we make the falls at this vertex.If we add a mountain fold orig at this vertex, there are three valleys and two mountains. If it’s a valley, there are ami four valleys and one mountain.Either way, the model doesn't fall flat.The third rule is that if we number all the angles at an interior vertex moving clockwise or counterclockwise, the even-numbered angles must add up to 180 degrees, as must the odd-numbered angles.Looking closer at the folds, we can see why.If we add a crease and number the new angles at this vertex, the even and odd angles no longer add up to 180 degrees, and the model doesn’t fold flat. Finally, a layer cannot penetrate a fold.A 2D, flat-foldable base is often an abstract representation of a final 3D shape.Understanding the relationship between crease patterns, 2D bases, and the final 3D form allows origami artists to design incredibly complex shapes. Take this crease pattern by origami artist Robert J. Lang. The crease pattern allocates areas for a creature's legs, tail, and other appendages. When we fold the crease pattern into this flat base, each of these allocated areas becomes a separate flap. By narrowing, bending, and sculpting these flaps, the 2D base becomes a 3D scorpion.Now, what if we wanted to fold 7 of these flowers from the same sheet of paper?If we can duplicate the flower’s crease pattern and connect each of them in such a way that all four laws are satisfied, we can create a tessellation, or a repeating pattern of shapes that covers a plane without any gaps or overlaps.The ability to fold a large surface into a compact shape has applications from the vastness of space to the microscopic world of our cells. Using principles of origami, medical engineers have re-imagined the traditional stent graft, a tube used to open and support damaged blood vessels. Through tessellation, the rigid tubular structure folds into a compact sheet about half its expanded size. Origami principles have been used in airbags, solar arrays, self-folding robots, and even DNA nanostructures— who knows what possibilities will unfold next. Hello, everyone. I'm here to help you design your life. We're going to use the technique of design thinking. Design thinking is something we've been working on at the d.School and in the School of Engineering for over 50 years, and it's an innovation methodology, works on products, works on services. But I think the 5 most interesting design problem is your life! So that's what we're going to talk step about. I want to just make sure everybody knows: this is my buddy Dave Evans, s to his face. Dave and I are the co-authors of the book, and he is the guy who desi helped me co-found the Life Design Lab at Stanford. So what do we do in the gni Life Design Lab? Well, we teach the class that helps to figure out what you want ng to be when you grow up. Now, I'm going to give you the first reframe. Designers the love reframes. How many of you hope you never grow up and lose that child-like life curiosity that drives everything you do? Raise your hand. Right! Who wants to you grow up? I mean, we've been talking about curiosity in almost every one of these wan talks. And so I'd like to reframe this as: we say we teach the class that helps you t figure out what you want to grow into next, as this life of yours, this amazing design of yours, unfolds. So, design thinking is what we teach and it's a set of mindsets, it's how designers think. You know, we've been taught probably in the university to be so skeptical realists, rationalists, but that's not very useful as a mindset when you're trying to do something new, something no one's ever done before. So we say you start with curiosity and you lean into what you're curious about. We say you reframe problems because most of the time we find people are working on the wrong problems and they have a wonderful solution to something that doesn't work anyway. So, what's the point of working on the wrong thing? We say radical collaboration because the answer's out in the world with other people. That's where your experience of your life will be. We want to be mindful of our process. There are times in the design process when you want lots of ideas, and there are times when you really want to converge test some things, prototype some things, you want to be good at that. And the other is biased action. Now, you know, I'll say that we think no plan for your life will survive first contact with reality. (Laughter) Reality has the tendency to throw little things at us that we weren't expecting, sometimes good things, sometimes bad. So we say: just have a biased action, try stuff. Why? Why did we start this class? I've been in office hours for a long, long time with my students. I've been teaching here for a while. Dave as well. He was teaching over that community college, in Berkeley, for a while. (Laughter) And - I'm sorry, I'm sorry, it's a Stanford TEDx. But we notice that people get stuck. People really get stuck and then they don't know what to do and they don't seem to have any tools for getting unstuck. Designers get stuck all the time. I signed up to be a designer, which means I'm going to work on something I've never done, every day, and I get stuck and unstuck, stuck and unstuck, all the time. We also noticed as we went out and talked to folks who are not just our students, but people in midcareer and encore careers, that people have a bunch of beliefs which psychologists label "dysfunctional beliefs," things they believe that are true that actually aren't true, and it holds them back. I'll give you three. First one is: "What's your passion? Tell me your passion and I'll tell you what you need to do." Now, if you actually have one of these things, these passions - you knew at two you wanted to be a doctor, you knew at seven you wanted to be a clown at Cirque du Soleil, and now you are one, that's awesome. But we're a sort of research space here at Stanford, so we went over to the Center for the Study of Adolescence, which by the way now goes up to 27 - (Laughter) and met with Bill Damon, one of our colleagues, a fantastic guy. He studied this question and it turns out less than 20% of the people have any one single identifiable passion in their lives. We hate a methodology which says, "OK, come to the front of the line. You have a passion? Oh, you don't? Oh, I'm sorry. When you have one, come on back and we'll help you with that." It's terrible, eight out of 10 people say, "I have lots of things I'm interested in." So this is not an organizing principle for your search or your design. The second one is, "Well, you should know by now, right? Don't you know where you're going? If you don't know, you're late." (Laughter) Now, what are you late for, exactly? I'm not quite sure. But you know, there's a meta-narrative in the culture and when I was growing up: by 25, you're supposed to maybe have a relationship, maybe have gotten married and started to get the family together. When I talk to my millennial students, they'll say, "Oh, that's got to be like 30 or something," because they can't imagine, anything past, like, 22, but 30 is a long way out. But we know that now these people are forming their lives much more fluidly, they are staying in a lot more dynamic motion between about 22 and 35, and so this notion that you're late is really kind of like, "Well, you should have figured this out by now." Dave and I don't "should" on anybody. In the book or in the class, we don't believe in "should." We just think, "Alright, you are whatever you are. Let's start from where you are. You're not late for anything." But the one we really don't like is: "Are you being the best possible version of you?" (Laughter) "I mean, because you're not settling for something that's less than the best, because this is Stanford. Obviously we all are going to be the best." Well, this implies that, one, there's a singular best; two, that it's a linear thing, and life is anything but linear; and three, it kind of comes from this business notion, there's an old business saying, "Good is the enemy of better, better is the enemy of best," and you always want to do your best in business. But if there isn't one singular best, then our reframe is, "The unattainable best is the enemy of all the available betters, because there are many, many versions of you that you could play out, all of which would result in a well-designed life." So I'm going to give you three ideas from design thinking five ideas, excuse me - That says five, doesn't it? Yeah. Five ideas from design thinking. And people who've read the book or taken the class have written back to us and said, "Hey, these were the most useful, these were the most doable, they were the most helpful." And we're human-centered designers, so we want to be helpful. The first one is this notion of connecting the dots. The number one reason people take our class and we hear read the book is they say, "You know, I want my life to be meaningful, I want it to be purposeful, I want it to add up to something." So, we looked in the positive psychology literature and in the design literature, and it turns out that there's who you are, there's what you believe and there's what you do in the world, and if you can make a connection between these three things, if you can make that a coherent story, you will experience your life as meaningful. The increase in meaning-making comes from connecting the dots. So we do two things. We ask people: "Write a work view. What's your theory of work? Not the job you want, but why do you work? What's it for? What's work in service of?" Once you have that, 250 words, then - this one's a little harder to get short, "What's the meaning of life? What's the big picture? Why are you here? What is your faith or your view of the world?" When you can connect your life view and your work view together, in a coherent way, you start to experience your life as meaningful. That's the idea number one. Idea number two: people get stuck and you've got to be careful because we can reframe almost anything, but there's a class of problems that people get stuck on that are really, really bad problems. We call them gravity problems. Essentially, they're something you cannot change. Now, I know you have a friend and you've been having coffee with this friend for a while, and they're stuck. They don't like their boss, their partner, their job, there's something that they don't like. But nothing's happening, right? Nothing's happening with them. If Dave were here he'd say, "Look, you can't solve a problem you're not willing to have." You can't solve a problem you're not willing to have, so if you've got a gravity problem and you're simply not willing to work on it, then it's just a circumstance in your life. And the only thing we know to do with gravity problems is to accept. In the design thinking chart, you start with empathy, then you redefine the problem, you come up with lots of ideas, then you prototype and test things, but that only works if it's a problem you're willing to work on. The first thing to do is accept and once you've accepted this as gravity problem - "I can't change it. You know, this is a company, the company is a family-run company and the name of the founder is on the door and if you're not in the family, you can't be the president." You're right, you can't! So, now you have to decide what you want to do. Is that a circumstance that you can reframe and work in, or do you need to do something else? So be really careful about gravity problems because they're pernicious and they really get in the way. But back to this idea of multiples, I do a little thought experiment with my students, and I say, you know, "The physicists up in SLAC have kind of demonstrated this multiverse thing might be real." You've heard of this, that there are multiple parallel universes, one right next to each other. And say, "We'll do a thought experiment. Let's say you could live in all the multiverses simultaneously, and not only that, but you'd know about your life in each one of these instances. So, you could go back and be the ballerina, and the scientist, and the CPA, and whatever else you wanted to be. You could have all these lives in parallel." When I ask them, "How many lives are you? How many lives would you want?", I get answers from three to 10,000. But, you know, we've sort of done the average: it's about 7,5. Most people think they have about 7,5 really good lives that they could live. And here's the deal: you only get one. But it turns out it's not what you don't choose, it's what you choose in life that makes you happy. Nevertheless, we reframed this and we say, "Great, there's more lives than one in you. So let's go on an odyssey, and let's really figure out those lives!" And we ask people to do some design. And the "ideate" bubble, it's about having lot's of ideas. So we say, "Let's have some ideas. We'll ideate your future, but you can't ideate just one. You have to ideate three." Now, there's some research from the School of Education that says if you start with three ideas and you brainstorm from there, you've got a much wider range of ideas, the ideas are more generative and they lead to better solutions to the problem rather than just starting with one and then brainstorming forward. So we always do threes; there's something magical about threes. We have people do three lives, and it's transformational. We give them this little rubric. One: "The thing you're doing, the thing you're doing right now, whatever your career is, just do it. And you're going to do it for five years and it's going to come out great." I mean, in design, we're sort of values-neutral, except for one thing: we never design anything to make it worse, right? I have been on some teams that made some pretty bad products, but we weren't trying to, we were trying to make it better. So, thing one: your life, make it better. And also put in the bucket list stuff: you want to go to Paris, to the Galapagos - the guy with the ice thing - before it's all under water and we can't see it anymore. So, that's plan one: your life goes great. Plan two: I'm really sorry to tell you, but the robots and the AI stuff - that job doesn't exist anymore, the robots are doing it. We don't need you to do that anymore. Now, what are going to do? So what do you do if the thing that you've got goes away? And you know, everybody's got a side hustle or something they can do to make that work. And three is: what's your wild-card plan? What would you do if you didn't have to worry about money? You've got enough. You're not fabulously wealthy, but you've got enough. And what would you do if you knew no one would laugh? My students come in for my office hours a lot of times, and they'll say something like, "Well, what I really want to do is this, but I can't just hear people saying, 'You didn't go to Stanford to do that, did you?'" (Laughter) Because somehow, if you went to Stanford, you have to do some of the amazing things the past speakers have been doing. "But what would you do if you had enough money and you didn't care what people thought? Anything from, 'I'm going to go study butterflies' to, 'I want to be a bartender, you know, in Belize.' What would you do?" And people have those three plans. Now what happens when they do this is, one, they realize, "Oh my gosh, I could actually have imagined my three completely parallel lives are all pretty interesting." Two, they rarely go become a bartender, you know, in Belize. But a lot of times, the things that come up in the other plans were things that they left behind somehow. In the business of life, they forgot about those things. And so they bring them back and put them in plan one, then they make their lives even better. Sometimes they do pivot, but mostly they just use this as a method of ideating all the possible wonderful ways they could have a life. Now, you could start executing that, but in our model, the thing you do after you have ideas is you build a prototype. We have met people who've quit their job and suddenly done something else, It hardly ever works. You kind of have to sneak up on it, because in our model, we want to set the bar really low, try stuff, have some success, do it again. So when we say "prototype," in our language, what we mean is a way to ask an interesting question, "What would it be like if I tried this?", a way to expose the assumptions, "Is this even the thing I want or is that just something I remember I wanted when I was 20?" I've got to go out in the world and do this, so I'm going to get others involved in prototyping my life, and I'm going to sneak up on the future, because I don't if this is exactly what I want. There's two kinds of life-design prototypes and what we call prototype conversation. You know, William Gibson, the science-fiction writer has a famous quote: "The future is already here. It's just unevenly distributed." So, there is someone who's a bartender in Ibiza. He's been doing it for years, I could go meet him and have a conversation, he or she. Somebody else is doing something else I'm interested in. All of these people are out there, they're living in my future, today. They're doing what I want to do, today. And if I have a conversation with them, I just ask for their story and everybody will tell you their story. If you buy them a cup of coffee, they tell you the story. If I hear something in the story that rings in me - We have this thing we call narrative resonance: when I hear a story that's kind of like my story, something happens, and I can identify that as a potential way of moving forward. The other one is a prototype experience. Dave and I were working with a woman, sort of mid-career in her 40s and a very successful tech executive, but wanted to move from money-making to meaning-making, to do something more meaningful, thinking of going back to school, getting an MA in education, working with kids. But she's like, "You know, I don't know, I'm 45, going back to school. It's not going to work. And then I heard about these millennials. They're kind of mean and they don't like old people." (Laughter) What am I going to do, Bill?" I said, "Well, you just have to go try this, you know. It turns out we sent her to a seminar class and to a large lecture-hall class, and by the way, you just put on a T-shirt that says "Stanford" and you walk into a class, nobody knows. She wasn't registered, but you know, she went and she went to the classes and she came back and said, "You know what? It was fantastic! I walked into the lecture hall, I sat down, my body was on fire! It was interesting, I was so interested in the way the lecture was going. And then I met these millennials. It turned out they're pretty interesting people! I've set up three prototype conversations. And they think I'm interesting because I'm coming back to school and I'm 45." So she had a felt experience, because we are more than just our brains. She had a felt experience that this might work for her. So these are two ways you can prototype your way forward. The last idea: you want to make a good decision well. So many people make choices and they're not happy with their choices because they don't really know how do they know what they know, right? It's a hard thing, particularly in our days when we have so many choices. So we have a process. Again it comes from the positive psychology guys. Gather and create options. Once you get good at design you're really good at coming up with options. You've got narrow those down to a working list that you can work with. Then, you make the choice to make a good choice, and then of course you agonize that you did the wrong thing. (Laughter) All my students have what is called FOMO, fear missing out, "What if I didn't pick the right thing." Someone came into my office and said, "I'll declare three majors and two minors" and I said, "Do you plan on being here for a few years? It's not going to happen, right?" So we don't say that; we say you want to let go and move on, and all these have some psychological basis in them. Let me tell you about it. Once you get good at gathering and creating ideas, you also want to make sure you leave room for the lucky ideas, the serendipitous ideas. This is a guy named Tony Hsieh. He was the CEO at Zappos, he sold it to Amazon. But before you became an employee at Zappos you had to take a test, and the test was, "Are you lucky?" One, two or three: "I'm not very lucky, and I'm not sure why." Seven, eight, nine, ten, "I'm very lucky, great things happen to me all the time, I'm not sure why." He wouldn't hire anybody who was not lucky. (Laughter) I think it's probably illegal, but it was based on - (Laughter) but it was based on a piece of research where psychologists did the same thing, "Rate yourself from lucky to unlucky." And then they had people read the front section of the New York Times, 30 pages, lots of articles. And the graduate students said, "Please count the number of -" either headlines or photographs, depending on the test. "And when you get the whole thing read and you count the number of photographs, just tell the person at the end." And if you got the right number, you'd get $100. Of course you all know when a graduate student tells you what the experiment is that's not the experiment. So, inside this thing that looked like the New York Times, 30 pages, front page, inside all the stories were little pieces of text that said, "If you read this, the experiment's over. Collect an extra $ 150." People who rated themselves as unlucky by and large got the right answer, 36 headlines, whatever it was, got the $ 100. People who rated themselves as lucky - seven, eight, nine or ten - 80% of the time noticed the text and got the extra $150. It's not about being lucky. It's about paying attention to what you're doing and keeping your peripheral vision open because it's in your peripheral vision that those interesting opportunities show up, right, that you were not expecting. So you want to get good at being lucky. Narrowing down. This is quite simple. If you have too many choices, you go into what psychologists call choice overload, and then you have essentially no choices. Here's the experiment. This was done at Stanford. You walk into a grocery store and there's a nice lady. She's got a table and on the table, she has six jams, and you come over try the jams to have a sample, buy some jam. Six jams; about 30 people who would go by pick a jam, or stop and test something, and about a third of those actually buy a jam. That's the baseline. Next week, you walk in, 24 jams: jalapeño, strawberry, banana, whatever; all sorts of jams. Well, guess what happens? Twice as many people stop, look at all these jams, it's so interesting. Three percent of the people buy them. (Laughter) When you have too many choices, you have no choice. What do you do when you have too many choices? Just cross off a bunch of choices. Psychologists tells us we can't handle more than five to seven. I'd say it's five. If you've got a bunch of choices, cross them all off, just pick the five and then make your decision there. "Oh my God! What if I pick the wrong ones? What if I cross off the wrong ones?" Right? Well, you won't, because it's the pizza or Chinese food thing. You're at the office and everybody says, "Let's go out to lunch today." "Sounds great. What do you want to do? Pizza or Chinese food?" "I don't care." In the elevator on their way down, someone says, "Let's get Chinese food." Then you go, "No, I want pizza." (Laughter) You won't decide how you feel about the decision till the decision's made. That's a piece of research that's been done again and again and again. So just cross them off. If you cross off the wrong one, you'll have a feeling somewhere in your stomach that you did the wrong thing. Choosing - this is about that feeling in your stomach. You cannot choose well if you choose only from your rational mind. This is Dan Goleman, who wrote the book on emotional intelligence. He does a lot of research on this, a lot of brain science. There's a part of your brain, way down in the base brain, the basal ganglia, that summarizes emotional decisions for you. I did something, got good emotional response from that: good, check. I did something and had a little bad emotional response to that. It summarizes all of the emotions that you have felt and how your decisions were valenced positive or negative an emotion. The problem with that part of your brain is that it's so early in the brain it doesn't talk to the part of your brain that talks. There's no connection to the prefrontal cortex or anything else. It's only connected to your GI tract and your limbic system. So, it gives you information through felt sensations, a "gut feeling." Without that, you can't make good decisions. And then the letting go and moving on. This was the hardest part for me, but this is also the work of Dan Gilbert, who is a distinguished scientist at Harvard, despite the fact that he's doing insurance commercials now. And he's been studying decision-making and how do you make yourself happy. So, you walk in another psychology experiment. The postdoc has got five Monet prints, five pictures from Monet, and you rank them from best to least, "I like this one the most, I like this one the least," number one and number five. "Thank you very much, the experiment's over. Oh, by the way, as you're walking out, you know, I kind of screwed up and I bought too many of number two and three. So if you want to take one home you can just have it. Two conditions: in one case, take it home and have it, but don't bring it back because I'm kind of embarrassed and - Just keep it, you can't exchange it. Second condition: I've got lots of these. If you don't like the one you picked, you can swap it back and pick another one." And of course everybody picks number two. It's a little better than number three. We bring people back in a week later and say, "Re-rank the stimuli. Which one do you like now?" The people who were allowed to change their mind don't like their painting, they don't like the print, they don't like the other one anymore, they don't like any of them anymore. In fact, they don't like the whole process and they have destroyed their opportunity to be happy. (Laughter) The people who were told, "You pick it, it's yours, you can't return it" love their print, they typically rank it as number one and think the rest of them suck. (Laughter) If you make decisions reversible, your chance of being happy goes down like 60 or 70 percent. So, let go and move on, make the decision reversible. And by the way, as a designer, that's no problem, because you're really good at generating options, you're great at ideation, you're really good at prototyping to get data in the world to see of that world will be the world you want to live in, so you have no fear of missing out. It's just a process, a mindful process: collect, reduce, decide, move on. That's how you make yourself happy. So, the five ideas: Connecting the dots to find meaning through work and life views. Stay away from gravity problems because I can't fix those and neither can you; reframe those to something that is workable. Do three plans, never one, always do three of everything, three ideations for any of the problems you're working on to make sure that you've covered not just the ideas that you had when you started, but all the other ideas that are possible. Prototype everything in your life before you jump in and try it. And choose well; there's no point in making a good choice poorly. Choose well and you will find that things in your life are much easier. And you can do this, we know you can, because thousands of students have done it. Two PhD studies have been done in the class that demonstrated higher selfefficacy, lower dysfunctional beliefs. It's a fascinating process to watch people who don't think of themselves as creative go through this class and walk out saying, "You know what? I'm a pretty creative person!" what David Kelly calls "creative confidence." So, we know you can do it, thank you very much. It's simple: get curious, talk to people and try stuff, and you will design a well-lived and joyful life. Thank you. (Applause) (Cheers) Tec I once watched this video of a relay race at a primary school in Jamaica. You hno see here, there are two teams, the Yellow team and the Blue team. And the kids logy are doing great, working so hard and running so fast. And the Yellow team has can' the lead, until this little boy gets the baton and runs in the wrong direction. My t fix favorite part is when the grown-up chases him, looking like he's about to pass ineq out, trying to save the situation and get the kid to run in the right direction.In ualit many ways, that's what it's like for many young people in Africa. They're many y -- paces behind their peers on the other side of the inequality divide, and they're but also running in the wrong direction. Because as much as we might wish trai otherwise, and aspire to build economic and social systems where it’s not the nin case, global development is a race. And it's a race that my home country, g Nigeria, and home continent, Africa, are losing.Inequality must be seen as the and global epidemic that it is. From the boy who cannot afford to dream because of opp the disappointment that could come with it to the girl that skips school in order to ortu sell snacks in traffic, just to fund her school fees. It is clear that inequality is at nitie the center of many of the world's problems, affecting not just the bottom 40 s percent of us, but everyone. Young men and women who don't get set on the coul path of equal opportunities become frustrated. And we may not like the choices d they make in their attempt to get what they think they rightly deserve or punish those that they assume keep them away from those better opportunities.But it doesn't have to be this way if we, as humanity, make different choices. We have the ability we need to fill that opportunity gap, but we just have to prioritize it.I grew up many paces behind. Even though I was a smart kid growing up in Akure, a town 350 kilometers from Lagos, it felt like a place that was disconnected from the rest of the world, and one where hope and dreams were limited. But I wanted to get ahead, and when I saw a computer for the first time, in my high school, I was spellbound, and I knew I just had to get my hands on whatever it was. This was in 1991, and there were only two computers for the entire school of more than 500 students. So the teacher in charge said computers were not for people like me, because I wouldn't understand how to use them. He would only allow my friend and his two brothers, sons of a professor of computer science, to use it, because they already knew what they were doing.In university, I was so desperate to be around computers that to make sure I had access to the computer lab, I slept there at night, even when the campus was closed due to teachers' strikes and student protests. I didn't own a computer until I was gifted one in 2002, but what I lacked in devices, I made up for in drive and determination.However, camping out in computer labs in order to teach yourself coding isn't a systemic solution, which is why I started Paradigm Initiative, to help all Nigerians learn to use technology to help them run faster and further toward their hopes and dreams, and help our nation and take our continent great leaps forward in development.You see, to put it as simply as possible, my goal is for everyone in Africa to become Famous'. I don't mean, like, a celebrity, I mean I want everyone to be like Famous, this guy. When Famous Onokurefe came to Paradigm Initiative, he had completed high school, but couldn't afford college, and his options in life were limited. When I asked Famous recently about where he would have been without our training program, he rolled out a list of could-haves, including ending up on the streets, jobless and homeless, at the risk of doing things he wouldn't be proud of. But luckily, Famous came to Paradigm Initiative, in 2007, because his friends, who were part of a youth group I'd told about my plans, kept talking about a free computer training program. And during his training, Famous paid close attention and excelled.When the United Kingdom Trade and Investment team at the UK Deputy High Commission in Lagos asked us to recommend a few potential interns, we recommended Famous and a few others to be interviewed. He got the internship, and while there, he heard about an Entry Clearance Assistant job at the [British] High Commission in Abuja. He applied, even though, without a college degree, no one thought he had a shot. He was starting behind, but it wasn't technology that helped him get ahead, it was the extra training, training rooted in his community, training that understood his context and his challenges, training that helped him change his life for the better.Famous got the job, and then saved enough to pay his way through university. Famous, a Medical Biochemistry graduate from Delta State University, is now a chartered accountant and an assistant manager with one of the world's Big Four professional services firms, where he has won innovation awards consecutively for the last four years. But let's be clear ... the computer didn't do that — we did.Without our additional training and support, Famous wouldn’t be where he is today. Fairness is not giving everyone a computer and a special program, fairness is helping make sure everyone has the same access and training that can help them make use of all these things to improve their lives. When people are further behind, fairness isn't giving everyone the same opportunity to compete, fairness is helping those who are behind to get to the same starting line with everyone else and giving them a chance to run their own race in the right direction. Yet there are millions of young people who have not been as fortunate as Famous and I, who still don't have the skills, let alone the will, to face similarly insurmountable inequality.As more workers and students now have to complete tasks or learn from home, this inequality is exponentially pronounced, and with dire consequences. This is why I do what I do through Paradigm Initiative.But just like many intervention programs, there's a limit to how many young people we can reach through our three centers. We've now taken the training to where the kids are, but public schools are so ill-equipped that we have to bring devices, access, and in many cases, we have to provide power supply.Since 2007, we've worked with young Nigerians in order to improve their lives and that of their families. To give just one example, Ogochukwu Obi father kicked her, her sisters and her mom out, because he preferred to have a son. But when she completed our program, got a job and became her family's breadwinner, her father came calling, admitting that he was wrong about the worth of the girl.In addition to our work at our training centers and in schools, we're now planning to acquire mobile learning units, busses equipped with access, with devices, and with power, and that can serve multiple schools. Yes, we need better access to technology and policies that facilitate open internet access, freedom of expression and more, but the best computers in the world could fall in a democratic forest, but no one would hear them, let alone use them, if they were miles away, hauling water from a well or foraging for scrap metal to pay school fees in a school that can’t even teach them computer skills. Just like the fanciest sneakers in the world can’t help a runner miles behind everyone else.I'll never forget being invited back to my high school while I was Nigeria's Information Technology Youth Ambassador. It was 10 years after I had been denied access to using the computer in that very same school. But here I was, being introduced as a role model who was supposedly shaped by the same school. After my presentation, that teacher, who said I could never understand how to use computers, was quick to grab the microphone and tell everyone that he remembered me as a student and he was sure I had it in me all along. He was right. He didn't know it at the time, but I did have it in me. Famous had it in him, Ogochukwu had it in her, the bottom 40 percent have it in them. Are we going to say that life-changing opportunities are not for people like them, like that teacher said? Or are we going to recognize that centuries of inequality can’t just be solved by gadgets, but by training and resources that fully level the playing field?Fairness is not about giving every child a computer and an app, fairness is connecting them to access, to training and to additional support, for the need to take equal advantage of those computers and apps. That's how we pass them the baton and help them catch up and start running in the right direction, and change their lives.Thank you. Co Don Cheadle: Home. It's where we celebrate our triumphs, make our memories mm and confront our challenges. And these days there are plenty of those. An unit historic pandemic, wildfires, floods and hurricanes all threaten our basic safety. yThese challenges hit even harder in communities that have been cut out of pow equal opportunities.In the US, unfair and racist housing policies, called redlining, ere have for decades forced Black, brown, Indigenous and poor white families into d areas rife with toxic chemicals that make people sick. They are surrounded by solu concrete that traps heat. Extreme temperatures demand more cooling, more tion money, more energy, more carbon. Our problems are interconnected. Imagine s to all we can do when we realize the solutions are too.At the Solutions Project, the we've seen that some of the people most impacted by COVID-19, least likely to clim have a steady place to call home and most affected by the damage to our ate climate are already working on effective and scalable solutions. Take Buffalo and crisi Miami, where affordable housing has become a community solution to the s climate crisis.Rahwa Ghirmatzion: Buffalo, New York, is the third poorest city in the United States and sixth most segregated, but our people power is strong. Over the last 15 years, my organization, PUSH Buffalo, has been working with residents to build green affordable housing, deploy renewable energy and to grow the resilience and power in our communities.When we saw heating bills soar over the last decade, we organized to pass state policy, help small businesses and to put our people to work weatherizing homes. We responded with eco-landscaping and green infrastructure. When record rainfalls flooded our neighborhoods, we replaced the concrete that overwhelmed and made heat waves unbearable.Let us visit School 77, an 80,000-square-foot public school building that was closed and abandoned for nearly a decade. But PUSH Buffalo and the community transformed it into solar-powered, affordable senior apartments and a community center. This is what the community wanted. When private developers were eyeing that school building for high-end loft apartments, 800 residents mobilized and came up with the plan. We became New York State's first community solar project and during the coronavirus pandemic, a volunteer-run Mutual Aid Hub.Zelalem Adefris: At Catalyst Miami and the Miami Climate Alliance, we work with dozens of other organizations to enact policies that provide safe housing and protect the climate. Here in Miami, we've seen a 400-percent increase in tidal flooding between 2006 and 2016 and have seen 49 additional 90-degree days per year since 1970. We fought for the Miami Forever Bond to fund 400 million dollars for affordable housing and climate solutions. Yet every day, we continue to see luxury high-rise condos being built in our neighborhoods, adding more concrete and heat on the ground. Some of our members are taking matters into their own hands, literally.Conscious Contractors is a Grassroots Collective that formed during Hurricane Irma to protect, rebuild and beautify our communities, all while increasing energy efficiency. They don't think that anyone should have to choose between paying a high AC bill and living in a hot and moldy house that will worsen respiratory illnesses such as asthma or coronavirus. They fix problems at the source.Advocates across the country are holding their governments accountable to climate solutions that keep their communities in place. We need to push for more affordable housing, green infrastructure and flood protections because these are the solutions that solve many problems at once.DC: Climate change is the epic challenge of our lives, but we're confident we can solve it. Community leaders like Rahwa and Zelalem are already doing it. We can create the future we want, but getting there is going to take everyone contributing around the world, wherever we call home. Everyone's heard of the tired old adage of paying yourself first. But that saying lacks a lot of useful details. How do you actually pay yourself first? So today, I'll lead you through some changes you can make to improve your saving strategy.[Your Money and Your Mind with Wendy De La Rosa]First and foremost, you should focus on only one goal at a time. Typically, we think about having multiple savings goals for multiple things. We have an emergency savings fund, a vacation fund, a wedding fund, a car fund ... But one great study compared people's savings progress when they had one savings goal compared to five savings goals. And it turns out that when participants had just one savings goal, they saved more than when they had five. The research showed that if you made progress in just one of your savings accounts, you'd think you've made progress across all of them. Like multitasking at work, splitting your attention across multiple savings goals just isn't efficient.Now, that's not to say that this will be your only savings goal; you'll have many more throughout your life. But I want you to think about the one thing that you want to focus on over the next six months to a year. Start with your emergency savings fund, even if it’s 500 dollars or 600 dollars, the average cost of a car repair, and then go from there.Now that you have a primary savings goal in mind, let's focus on helping you increase the amount that you save. Your main savings strategy should be to switch from having to remember to save a small amount every month to saving a percentage of your income automatically, any time you receive income.Now, some people advise saving 10, 15 or 20 percent of your income, but that's not important. You A know your financial situation. You know how much you can manage to save. The sim real trick is to find a provider that lets you set up an automatic savings plan and ple not to have to think about it ever again. The "set it and forget it" approach is 2shown to help you save more. Researchers believe that passive systems like step this are successful, because they work with our tendency towards inertia. You plan don't have to manually initiate each subsequent transfer, and you won't be for tempted to hold back a bit every time you make a savings transfer. I want you to savi take the time right now to find a provider. Go to your app store, download the ng app and set up your automatic savings plan.If you make these two small mor changes — focus on just one savings goal at a time and automate your savings e — you should find success, even if you don't think you're saving that much mo money. And it's easier than it may seem. So there you have it. We have ney demystified the old adage of paying yourself first. Here in this abundant forest, Malassezia is equipped with everything it could ever need. Feasting constantly, it’s in paradise. But wait— what’s this? In fact, Malassezia is a type of yeast that lives and dines on all of our scalps. And in about half of the human population, its activity causes dandruff. So, why do some people have more dandruff than others? And how can it be treated?We might consider ourselves individuals, but we’re really colonies. Our skin hosts billions of microbes. Malassezia yeasts make themselves at home on our skin shortly after we’re born. Follicles, the tiny cavities that grow hairs all over our body, make for especially popular living quarters. Malassezia are fond of these hideouts because they contain glands that secrete an oil called sebum that’s thought to lubricate and strengthen our hair. Malassezia evolved to consume our skin’s proteins and oils. And because of its many sebum-secreting follicles, our scalp is one of the oiliest places on our body— and consequently, one of the yeastiest. As these fungi feast on our scalp’s oils, dandruff may form.This is because sebum is composed of both saturated and unsaturated fatty acids. Saturated fats neatly pack together. Unsaturated fats, on the other hand, contain double bonds that create an irregular kink in their structure. Malassezia eat sebum by secreting an enzyme that releases all of the oil’s fatty acids. But they only consume the saturated fats, leaving the unsaturated ones behind. These irregularly shaped leftovers soak into the skin and pry its barrier open, allowing water to escape. The body detects these breaches and responds defensively, causing the inflammation that gives dandruff it’s itch. It also makes the skin cells proliferate to repair the damaged barrier.Usually, our skin’s outer surface, or epidermis,completely renews itself every two to three weeks, Epidermal cells divide, move outwards, die, and form the skin’s tough outer layer, which Wh gradually sheds off in single cells far too small to see. But with dandruff, cells at churn out quickly to correct the broken barrier, meaning they don’t mature and cau differentiate properly. Instead, they form large, greasy clumps around the hair ses follicle that are shed as visible flakes.This is how Malassezia’s voracious dan appetite and our bodies reaction to its by-products lead to dandruff. Currently, druf the most effective way to get rid of dandruff is by using antifungals in things like f, shampoos, applied directly to the scalp, to kill Malassezia.For those who and experience dandruff, it usually comes and goes as sebum secretions vary how throughout one's lifetime due to hormonal changes. But despite the fact that do Malassezia colonize everyone to a similar extent, not everyone gets dandruff. you Some people are more susceptible. Exactly why is unclear. Do people with get dandruff have a certain genetic predisposition? Is their skin barrier more rid permeable? Scientists are currently investigating if people with dandruff do, in of fact, lose more water through their scalps, and whether this is what’s leading it? their skin cells to proliferate. Researchers are learning that Malassezia communicate with our immune system using small, oily molecules called oxylipins that regulate inflammation. If they can find a way to inhibit inflammatory oxylipins and boost anti-inflammatory ones, they could develop new treatments.Scientists are also investigating if there’s any benefit to our relationship with Malassezia. They hypothesize that dandruff, which can be uncomfortable and embarrassing for us, creates a reliable, oily food source for the yeast. But dandruff isn’t contagious or a great threat to our health. And Malassezia seem to excel at defending their territory, our skin, from other, more harmful microbes like Staphylococcus aureus.So, while scientists have gotten to the bottom of many mysteries surrounding this condition, it must be said: dandruff remains a head-scratcher. In the late 1860s, scientists believed they were on the verge of uncovering the brain’s biggest secret. They already knew the brain controlled the body through electrical impulses. The question was, how did these signals travel through the body without changing or degrading? It seemed that perfectly transmitting these impulses would require them to travel uninterrupted along some kind of tissue. This idea, called reticular theory, imagined the nervous system as a massive web of tissue that physically connected every nerve cell in the body. Reticular theory captivated the field with its elegant simplicity. But soon, a young artist would cut through this conjecture, and sketch a bold new vision of how our brains work.60 years before reticular theory was born, developments in microscope technology revealed cells to be the building blocks of organic tissue. This finding was revolutionary, but early microscopes struggled to provide additional details. The technology was especially challenging for researchers studying the brain. Soft nervous tissue was delicate and difficult to work with. The And even when researchers were able to get it under the microscope, the tissue arti was so densely packed it was impossible to see much.To improve their view, st scientists began experimenting with special staining techniques designed to who provide clarity through contrast. The most effective came courtesy of Camillo won Golgi in 1873. First, Golgi hardened the brain tissue with potassium bichromate a to prevent cells from deforming during handling. Then he doused the tissue in Nob silver nitrate, which visibly accumulated in nerve cells. Known as the “black el reaction,” Golgi’s Method finally allowed researchers to see the entire cell body Priz of what would later be named the neuron. The stain even highlighted the fibrous e... branches that shot off from the cell in different directions. Images of these in branches became hazy at the ends, making it difficult to determine exactly how med they fit into the larger network. But Golgi concluded that these branches icin connected, forming a web of tissue comprising the entire nervous system.14 e years later, a young scientist and aspiring artist named Santiago Ramón y Cajal began to build on Golgi’s work. While writing a book about microscopic imaging, he came across a picture of a cell treated with Golgi’s stain. Cajal was in awe of its exquisite detail— both as a scientist and an artist. He soon set out to improve Golgi’s stain even further and create more detailed references for his artwork.By staining the tissue twice in a specific time frame, Cajal found he could stain a greater number of neurons with better resolution. And what these new slides revealed would upend reticular theory— the branches reaching out from each nerve cell were not physically connected to any other tissue. So how were these individual cells transmitting electrical signals? By studying and sketching them countless times, Cajal developed a bold, new hypothesis. Instead of electrical signals traveling uninterrupted across a network of fibers, he proposed that signals were somehow jumping from cell to cell in a linear chain of activation.The idea that electrical signals could travel this way was completely unheard of when Cajal proposed it in 1889. However his massive collection of drawings supported his hypothesis from every angle. And in the mid-1900s, electron microscopy further supported this idea by revealing a membrane around each nerve cell keeping it separate from its neighbors. This formed the basis of the “neuron doctrine,” which proposed the brain’s tissue was made up of many discrete cells, instead of one connected tissue.The neuron doctrine laid the foundation for modern neuroscience, and allowed later researchers to discover that electrical impulses are constantly converted between chemical and electrical signals as they travel from neuron to neuron. Both Golgi and Cajal received the Nobel Prize for their separate, but shared discoveries, and researchers still apply their theories and methods today. In this way, their legacies remain connected as discrete elements in a vast network of knowledge. Concrete is the second most used substance on earth after water, and for this A reason, it has a significant environmental impact. If it were a country, it would con rank third for emissions after China and USA. But in fact, concrete is an cret intrinsically low-impact material with much lower emissions of CO2 and energy e per ton than other materials like iron and steel, even things like bricks. But idea because of the enormous volumes we use overall, it contributes to about eight to percent of man-made CO2 emissions.Concrete is an essential material. We red need it to house people, to build roads, bridges and dams. So we can't do uce without it, but we can significantly reduce its carbon footprint.Concrete is held car together by cement. And cement we use today, called Portland cement, is made bon by heating together a combination of limestone and clay at a temperature of emi 1,450 degrees Celsius. But in fact, most of the CO2 emissions come not from ssio the heating, but from the breakdown of limestone, which is calcium carbonate, ns into calcium oxide and carbon dioxide, or CO2.Now we can't do without this component altogether, because nothing else is so efficient at holding stuff together. But we can replace a large proportion of it with other materials with lighter carbon footprints. Many colleagues are looking for solutions. And here in Switzerland, we have found that clays produce very reactive materials when they're calcined, that's to say heated to around 800 degrees Celsius, significantly lower than the 1,450 needed to produce cement. But more importantly, there's no CO2 emissions from the decomposition of limestone. We then take this calcined clay, and we add a bit of limestone — but this time not heated, so no CO2 emissions — and some cement, and this combination of limestone, calcined clay and cement, we call LC3.Now this LC3 here has the same properties as Portland cement. It can be produced with the same equipment and processes and used in the same way, but has up to 40 percent lower CO2 emissions. And this was demonstrated in this house we built near Jhansi in India, where we could save more than 15 tons of CO2, which was 30 to 40 percent compared to existing materials.So why isn't everybody already using LC3? Well, cement is a local material. The reason Portland cement is so pervasive is that it's produced from the most abundant materials on Earth and can be produced in India, in the United States, in Ethiopia, almost anywhere. And we have to work with people locally to find the best combination of materials to make LC3. We have already done full-scale trials in India and Cuba. In Colombia, a product based on this technology was commercialized a few months ago, and in the Ivory Coast, the full-scale plant is being commissioned to calcine clays. And many of the world's largest cement companies are looking to introduce this in some of their plants soon.So the possibility to replace Portland cement with a different material — but with the same properties, produced in the same processes and used in the same way, but with much lighter carbon footprint — is really crucial to confront climate change because it can be done fast and it can be done on a very large scale with the possibility to eliminate more than 400 million tons of CO2 every year. So we can't do without concrete, but we can do without a significant amount of the emissions it produces.Thank you. Ho I remember climbing to the top of our airing cupboard at home — I must've been w to six or seven — I'm trying to flick my wrists in the right way to make the spider get web shoot out. I thought I had some super powers, I just had to work out what ever they were. It was a disappointing afternoon.(Laughter)In the end, it didn't come yon with a suit, but I found there aren't many people like me in the environment e to sector and being a Black economist who grew up in Derby is my superpower in care the fight for the environment.And we're facing huge challenges, but they are not abo insurmountable. People have been working on climate change and nature ut a restoration for years and they know what we need to do, and they know the gre sooner we act, the easier it will be. And we're not talking about a few green en sectors. We're talking about changing the whole economy, using investment and eco policy to reward people and businesses for the decisions they take that lower no carbon and restore nature rather than degrade it.The problem is politicians aren't my acting at the speed or scale we need them to because they think the public want them to do something else first. Brexit, building more houses, the economy, Brexit, health sector, Brexit.(Laughter)How do we put the environment at the top of that list? My answer is ... we don’t. We look at this the other way around instead. We show how moving to a green economy delivers on the things that people are already worried about. It improves their lives, whether they care about the environment or not.We're at the point we need to have a very different conversation with people because we need to make the case to rapidly move to a green economy, at a time people are facing real economic challenges, and we can't ask them to put that to one side. And we need to make the case to rapidly move to a green economy at a time of rising populism, which says leaving the EU or stopping immigration will solve all our problems. It won't, but we have to give people real solutions instead. So what does my perspective tell us?I grew up in Derby, an industrial city right in the middle of the country at the foot of the peak district, some of the most beautiful countryside in the UK. And I started my career in regional economics, and I know the UK has got the biggest differences in regional economic performance of any economy in the advanced world. Wealth is concentrated in London and we spend our time — concerning the economy, that's the only region that matters. And that really frustrates people, and it's really bad economics. For too long, we've ignored agriculture and manufacturing, two of the most important sectors for the environment, that need to pioneer new ways of producing goods and food sustainably. Being an economist, I know that UK productivity has stalled and the average weekly wage has not recovered since the financial crisis. That's a decade of lower pay. And that really hurts. We need to invest in our economy, so businesses are competing, not on the basis of low wages, but on high-design, engineering, smart use of resources, all the things we need to succeed in a green economy.And being mixed race, I know the dangers of populism. I feel them personally. I see people being divided and told that some group or other is to blame for all their problems. And I know that's not going to improve anybody's lives, but the environment sector isn't reaching those people and we have to fix that.You might be asking, why do we need to change the conversation now, when interest in the environment has never been higher? Aren't we already winning? Yes, in some ways we are. But we have all the people who are motivated by the plight of the polar bear and the loss of the rain forest. We have all the people who can change their whole life around and make every decision based on how they lower their carbon footprint. You might be one of those people, that is amazing, you are a trailblazer. But that is not a route that everyone can follow. And it is not enough to rely on what individuals can do by themselves.Now, we also need the backing of people who've got other things on their mind: bills to pay, a busy and polluted route to school for the kids, crap job, no prospects, living in a town where more businesses are closing than opening. They need to know the green economy is going to work for them. They do not need another thing to worry about. They do not need to be made to feel guilty. And they do not need to be asked to sacrifice something they don’t have. It's like the gilets jaunes protesters were saying in France about fuel prices and the cost of living: "You want us to worry about the end of the world when we're worried about the end of the week." If we're not listening to those people, you can be sure that the populists are.In my experience, if you want to achieve change and persuade people, you have to talk to them about things that they care about, not the things you care about. And if you ask people, what are the biggest issues facing the country? They say Brexit, that's said by most people by far, and then they say health, and then the environment comes level pegging with crime and the economy. Rather than constantly trying to put environment at the top of the list, we need to show how delivering a green economy will improve our health and our well-being and our quality of life, how it will deliver better jobs, a better economy, more opportunities. I'd even go as far as to say how it deals with the underlying consequences of Brexit.How does environmental policy do all that? We keep being told that it's going to cost too much to save the planet. That's not true. The best source on this is the global commission for climate and the economy. That's economists, former heads of states and finance ministers. And they looked at all the costs and benefits of acting compared to not acting. And they worked out the investments we need to keep the planet within one and a half degrees temperature rise actually improve the economy. And that was true globally, and it's true for the global South that really suffer if we don't act. And those calculations were based on the most prudent estimates of the cost and benefits, not counting all the innovation benefits and the cost savings we're likely to realize on the way.And it's the same story in the UK. The investments we need to make to move to a net zero economy will pay for themselves in jobs, opportunities, health and well-being. And that's just the climate action. It's increasingly clear we need to deal with climate and nature risk together. Species loss, habitat loss, climate change are all driven by the same broken patterns of consumption and production. If we get this right, dealing with climate change will help us preserve nature, and investing in nature will help us mitigate and adapt to climate change. The natural capital committee in the UK calculated that every one pound we spend on our forests, our wetlands, our biodiversity, gives us four to nine pounds back in social and economic benefits.And I've said all that, and it's true, but it means nothing to most people. I get a bit closer. If I start talking about the investments we have to make in our houses, our businesses, transport infrastructure, in our countryside, because those investments have got direct benefits for people, as well as the planet. They mean less drafty houses, a less stressful and congested journey to work, less flooding, cleaner air. So is that going to convince a gilets jaunes protester? No.It is not enough to say there's all this great stuff coming. We have to show how it's going to reach people. We can't have schemes for insulating your home and installing a heat pump and a solar panel, which are only accessible to people who own their own home. In the UK, renters have got 10 percent less disposable income than people with a mortgage. And they're the ones who need government policy to make sure their landlord insulates their home. We can't just talk about 210,000 jobs which have been created, and low-carbon and renewable industries. We also have to talk about how so-called dirty industries, construction and manufacturing, how they will generate better quality, highly skilled jobs if they're investing in water, energy, material efficiency, in products that last longer and produce less waste.We haven't even done the basics yet. We haven't even stopped supporting fossil fuels. The UK has got the biggest fossil fuel subsidies of any country in the EU. Most of those are tax breaks to oil and gas companies, which we should just stop. But some of it is more complicated. No politician is going to stop winter fuel payments to an old person who's worried about paying their heating bill, unless they first put in place a retrofitting scheme so that person has a warm, and comfortable home instead. No politician is going to raise fuel levy and we know that's true because it hasn't risen since 2011. No politician is going to do that and really change the incentives for owning a petrol and diesel car, unless they first put in place good quality, affordable public transport, a scrappage scheme so people can upgrade to an electric vehicle, and charging infrastructure, especially in rural areas, so people aren't cut off from the shops and work and college. And until that happens, the electric vehicle market doesn't take off and we don't get the benefits of cleaner, less congested, more livable cities.The environment sector has to show it's on the side of people who need these solutions. We have the technical side. Now we need the social and economic policies to make this work for people. And this isn't just a moral preference for fairness. This is also about effective policy. Everywhere in the world is facing these same challenges. And businesses want to invest in the solutions in the places where government is really thinking about how to create the conditions for change and how to build a widespread public support. The people-side of this is not somebody else's job. This is our job as environmentalist too.The environment sector has to be right in the middle of a conversation about what kind of country we want to be and how our policies will really improve people's lives. The fairness of the green transition is not a "nice to have." It is a thing that will make the transition happen or not. We will get stuck in protests if we don't make this work for people. If you're serious about moving to the green economy, like I am, you have to be serious about getting the benefits to the people who need them first. There is no way of delivering a change this big without doing that. So my superpower might not be to do whatever a spider can. But I can talk about the policies we need to green our economy in a way a factory worker in Derby and a farmer in Cumbria can get behind. My superpower is not trying to add to the list of things that people care about, but showing how the plan for a green economy is a plan to improve lives right now.Thank you.(Applause) In 1984, two field workers discovered a body in a bog outside Cheshire, England. Officials named the body the Lindow Man and determined that he’d suffered serious injuries, including blunt trauma and strangulation. But the most shocking thing about this gruesome story was that they were able to determine these details from a body over 2,000 years old. Typically, decomposition would make such injuries hard to detect on a body buried just weeks earlier. So why was this corpse so perfectly preserved? And why don't all bodies stay in this condition?The answers to these questions live six feet underground. It may not appear very lively down here, but a single teaspoon of soil contains more organisms than there are human beings on the planet. From bacteria and algae to fungi and protozoa, soils are home to one quarter of Earth’s biodiversity. And perhaps the soil’s most important inhabitants are microbes, organisms no larger Wh than several hundred nanometers that decompose all the planet’s dead and y dying organic material.Imagine we drop an apple in the forest. As soon as it did contacts the soil, worms and other invertebrates begin breaking it down into n't smaller parts; absorbing nutrients from what they consume and excreting the this rest. This first stage of decomposition sets the scene for microbes. The specific 2,00 microbes present depend on the environment. For example, in grasslands and 0 farm fields there tend to be more bacteria, which excel at breaking down grass year and leaves. But in this temperate forest there are more fungi, capable of old breaking down complex woody materials. Looking to harvest more food from the bod apple’s remains, these microbes release enzymes that trigger a chemical y reaction called oxidation. This breaks down the molecules of organic matter, dec releasing energy, carbon, and other nutrients in a process called mineralization. om Then microbes consume the carbon and some nutrients, while excess pos molecules of nitrogen, sulfur, calcium, and more are left behind in the soil.As e? insects and worms eat more of the apple, they expose more surface area for these microbial enzymes to oxidize and mineralize. Even the excretions they leave behind are mined by microbes. This continues until the apple is reduced to nothing— a process that would take one to two months in a temperate forest. Environments that are hot and wet support more microbes than places that are cold and dry, allowing them to decompose things more quickly. And less complex organic materials break down faster. But given enough time, all organic matter is reduced to microscopic mineral nutrients. The atomic bonds between these molecules are too strong to break down any further. So instead, these nutrients feed plant life, which grow more food that will eventually decompose. This constant cycle of creating and decomposing supports all life on Earth.But there are a few environments too hostile for these multi-talented microbes— including the peat bogs outside Cheshire, England. Peat bogs are mostly made of highly acidic Sphagnum mosses. These plants acidify the soil while also releasing a compound that binds to nitrogen, depriving the area of nutrients. Alongside cold northern European temperatures, these conditions make it impossible for most microbes to function. With nothing to break them down, the dead mosses pile up, preventing oxygen from entering the bog. The result is a naturally sealed system. Whatever organic matter enters a peat bog just sits there— like the Lindow Man. The acid of the bog was strong enough to dissolve relatively simple material like bone, and it turned more complex tissue like skin and organs pitch black. But his corpse is otherwise so well-preserved, that we can determine he was healthy, mid-20s, and potentially wealthy as his body shows few signs of hard labor. We even know the Lindow Man’s last meal— a still undigested piece of charred bread.Scholars are less certain about the circumstances of his death. While cold-blooded murder is a possibility, the extremity of his injuries suggest a ritual sacrifice. Even 2,000 years ago, there’s evidence the bog was known for its almost supernatural qualities; a place where the soil beneath your feet wasn’t quite dead or alive. Ho In an era of extreme polarization, it's really dangerous to talk about right and w wrong. You can be targeted, judged for something you said 10 years ago, 10 tech months ago, 10 hours ago, 10 seconds ago. And that means that those who nol think you're wrong may burn you at the stake or those who are on your side that ogy think you're not sufficiently orthodox may try and cancel you. As you're thinking cha about right and wrong, I want you to consider three ideas. What if right and nge wrong is something that changes over time. What if right and wrong is s something that can change because of technology. What if technology is moving our exponentially?So as you're thinking about this concept, remember human sen sacrifice used to be normal and natural. It was a way of appeasing the gods. se Otherwise the rain wouldn't come, the sun wouldn't shine. Public executions. of They were common, normal, legal. You used to take your kids to watch righ beheadings in the streets of Paris. One of the greatest wrongs, slavery, t indentured servitude, that was something that was practiced for millennia. It was and practiced across the Incas, the Mayas, the Chinese, the Indians in North and wro South America. And as you're thinking about this, one question is why did ng something so wrong last for so long? And a second question is: why did it go away? And why did it go away in a few short decades in legal terms?Certainly there was a work by extraordinary abolitionists who risked their lives, but there may be something else happening alongside these brave abolitionists. Consider energy and the industrial revolution. A single barrel of oil contains the energy equivalent of the work of five to 10 people. Add that to machines, and suddenly you've got millions of people's equivalent labor at your disposal. You can quit oppressing people and have a doubling in lifespan after a flattened lifespan for millennia. The world economy, which had been flat for millennia, all of a sudden explodes. And you get enormous amounts of wealth and food and other things produced by far fewer hands.Technology changes the way we interact with each other in fundamental ways. New technologies like the machine gun completely changed the nature of warfare in World War I. It drove people into trenches. You were in the British trench, or you were in the German trench. Anything in between was no man's land. You entered no man's land. You were shot. You were killed. You tried to leave the trench in the other direction. Then your own side would shoot you because you were a deserter.In a weird way, today's machine guns are narrowcast social media. We're shooting at each other. We're shooting at those we think are wrong with posts, with tweets, with photographs, with accusations, with comments. And what it's done is it's created these two trenches where you have to be either in this trench or that trench. And there's almost no middle ground to meet each other, to try and find some sort of a discussion between right and wrong.As you drive around the United States, you see signs on lawns. Some say, "Black Lives Matter." Others say, "We support the police." You very rarely see both signs on the same lawn. And yet if you ask people, most people would probably support Black Lives Matter and they would also support their police. So as you think of these polarized times, as you think of right and wrong, you have to understand that right and wrong changes and is now changing in exponential ways.Take the issue of gay marriage. In 1996, twothirds of the US population was against gay marriage. Today two-thirds is for. It's almost 180-degree shift in the opinion. In part, this is because of protests, because people came out of the closet, because of AIDS, but a great deal of it has to do with social media. A great deal of it has to do with people out in our homes, in our living rooms, through television, through film, through posts, through people being comfortable enough, our friends, our neighbors, our family, to say, "I'm gay." And this has shifted opinion even in some of the most conservative of places. Take the Pope. As Cardinal in 2010, he was completely against gay marriage. He becomes Pope. And three years after the last sentence he comes out with "Who am I to judge?" And then today, he's in favor of civil unions.As you're thinking about technology changing ethics, you also have to consider that technology is now moving exponentially. As right and wrong changes, if you take the position, "I know right. And if you completely disagree with me, if you partially disagree with me, if you even quibble with me, then you're wrong," then there's no discussion, no tolerance, no evolution, and certainly no learning.Most of us are not vegetarians yet. Then again, we haven't had a whole lot of faster, better, cheaper alternatives to meat. But now that we're getting synthetic meats, as the price drops from 380,000 dollars in 2013 to 9 dollars today, a great big chunk of people are going to start becoming vegetarian or quasi-vegetarian. And then in retrospect, these pictures of walking into the fanciest, most expensive restaurants in town and walking past racks of bloody steaks is going to look very different in 10 years, in 20 years and 30 years.In these polarized times, I'd like to revive two words you rarely hear today: humility and forgiveness. When you judge the past, your ancestors, your forefathers, do so with a little bit more humility, because perhaps if you'd been educated in that time, if you'd lived in that time, you would've done a lot of things wrong. Not because they're right. Not because we don't see they're wrong today, but simply because our notions, our understanding of right and wrong change across time.The second word, forgiveness. Forgiveness is incredibly important these days. You cannot cancel somebody for saying the wrong word, for having done something 10 years ago, for having triggered you and not being a hundred percent right. To build a community, you have to build it and talk to people and learn from people who may have very different points of view from yours. You have to allow them a space instead of creating a no man's land. A middle ground, a ??? and a space of empathy. This is a time to build community. This is not a time to continue ripping nations apart.Thank you very much. TikT More than 1.5 billion people around the world, over half of them under the age of ok, 24, regularly watch short videos: clips of 60 seconds or less using Snapchat, Inst TikTok, Instagram Stories and other smartphone apps.The market barely existed agr seven years ago, yet today creators are uploading 702 million short videos every am, day. As our attention span is falling to seconds, short video is not only here to Sna stay but will become the new normal. Unlike other social platforms such as pch Instagram, where perfectly edited, polished images are the norm, short videos at -- are more accessible, inviting imperfection and authenticity. And because each and clip is so short, content producers have to be creative and concise the communicators.But these bite-sized videos are more than just fun and rise entertainment. For me personally, as a consultant and mother, short videos are of where I get parenting tips. On my way to work I can quickly learn about the bite secrets of breastfeeding while traveling and get great ideas about how to make my daughter sleep sooner. Businesses are also learning that short videos are a size great way to find new customers and expand the diversity of their d audiences.Earlier this year, I led a project with TikTok, the world's leading shortcon video platform, to assess the economic and social impact of this bite-sized tent economy. Our study shows that this young medium is changing a lot more than the way we spend our leisure time. In 2019, short video generated an estimated 95 billion US dollars in goods and services sold and created roughly 1.2 million jobs globally. Even within this short lifespan, short video is already impacting the way we work, communicate and learn.In the age of COVID-19, while museums around the world are facing indefinite closure, many have acted quickly to bring in an engage and new, younger audience remotely. The Uffizi Gallery in Florence, which just established its official new website three years ago, is using short video to attract new audiences to their statues and paintings. By matching exhibits with emojis, music lyrics or funny quotes, the museum is making its artwork more accessible and relevant to the young generation of art lovers. In one of its recent posts, a cartoon coronavirus turned into a rock and smashed in half in front of Caravaggio's painting "Medusa," who has the power to turn those who gaze at her into stone.(Video) (Music: "Symphony No. 5")(Recording) Cardi B: Coronavirus!(Voice-over) Qiuqing Tai: Uffizi also experimented with influencers livestreaming from the gallery on short-video platform, allowing viewers around the world to experience art that they've never been able to see in person. Since its appearance on TikTok in April 2020, the museum's profile has attracted more than 43,000 followers in three months. This speed is far quicker than their journey on Twitter, where it built up a similar number of fanbase during the past four years.Small businesses are also using short video as a way to find new audiences who might have never heard of them or their products before. In 2018, Douyin, the leading Chinese short-video platform, as part of a social responsibility initiative to alleviate poverty in China, launched a campaign to help individual farmers and small businesses in China's mountainous areas sell farm produce. As one of its pilot projects, Douyin invited content producers to create four pieces of 15-second short videos showcasing the quality of their products. This is on top of other, regular PR initiatives, such as promotional articles. Douyin wanted to leverage the large user base of short video to find those customers who might be interested in those products and then connected them with the e-commerce website so that people can buy things as they watch the videos. In just five days, the initiative helped nearly 4,000 families in Sichuan Province sell an astonishing 120,000 kilograms of plums.Many brands that are interested in hiring and recruiting young people have been using short video as a fresh way to engage with Generation Z. For example, more than half of McDonald's employees are aged between 16 to 24. In Australia, the brand was struggling to recruit in recent years, so it launched something called "snaplication," which is a Snapchat lens that enabled users to shoot 10-second videos explaining why they'd be a perfect McDonald's employee and then prompted them to a link with a job application. Within 24 hours after launching the campaign, McDonald's received 3,000 "snaplications," four times more than the number they received in a whole week using traditional methods. While it's unclear whether hiring over short video is the best way to find the right people for the job or to retain talent, but judging solely from recruiting numbers, the campaign was a global hit. In Saudi Arabia, McDonald's received 43,000 snaplications within 24 hours, and the company launched the campaign again later in the US.Much like how I like to get parenting tips from short video, many users also want to leverage the platform to learn, but in tiny, bit-sized doses. In our study, short video users globally ranked the top benefits of the platform as discovering new interests and learning new skills. In emerging markets especially, short video for learning and education has huge potential to change the status quo. In 2019, TikTok launched a campaign in India with the aim of democratizing learning for the Indian digital community. While the app has been banned in the country since July 2020, it launched a huge demand for educational short-video content and other platforms are jumping in to fill in the space. TikTok was able to spark this trend by collaborating with Indian social enterprises, education startups and popular creators to produce 15-second short videos that covered a range of topics from school-level science to learning new languages. As the first wave of short video became widely spread on the platform, audiences got inspired and some even began to create their own educational content. By October 2019, the campaign had generated more than 10 million videos and garnered 48 billion views. Through helping people learn and participate in the process of content creation, short videos are in fact helping prep and train the skilled population that can take on the challenges of the future.Like all social media, there are valid concerns around short-video platforms, including data privacy, the addictive nature of the format and the lack of nuance and context in the content. However, I still think that the positive outcomes of short video will outweigh its downsides. I believe short video will become a more vital economic and social force in the future. It is precisely because of this that we need to find the right way to benefit from this young medium through collaboration among users, platforms and policymakers.Thank you. One day, without warning or apparent cause, all of humanity’s artificial satellites suddenly disappear.The first to understand the situation are a handful of government and commercial operators. But well before they have time to process what’s happened, millions sitting on their couches become aware that something is amiss. TV that’s broadcast from or routed through satellites dominate the market for international programming as well as some local channels, so the disappearance causes immediate disruptions, worldwide.The next people affected are those traveling by air, sea, or land, as global positioning, navigation and timing services, have entirely ceased. Pilots, captains, and drivers have to determine their locations using analog instruments and maps. Aircraft, ships, and ground vehicles get stopped, grounded, or returned to port. In the meantime, air traffic controllers have a difficult task on their hands to prevent plane crashes. Within hours, most of the planet’s traffic grinds to a halt.The effects aren’t limited to entertainment and travel. All sorts of machines, from heating and cooling systems to assembly lines, rely on superaccurate satellite-based timing systems, and many have little-to-no backup options. Stoplights and other traffic control systems stop synchronizing, so police and good Samaritans step in to direct the remaining cars and prevent as many accidents as possible.The most catastrophic impact is yet to come. Because in the next few hours, the world economy shuts down. Satellite-based timestamps play a critical part in everything from credit card readers and stock exchanges to the systems that keep track of transactions. People are unable to withdraw cash or make electronic payments. Logistics and supply chains for crucial goods like food and medicine fragment, leaving people to survive on whatever is locally Wh available. Most countries declare a state of emergency and call on the military to at if restore order.That may take quite a while. Most navigation and communication ever systems are no longer operational, so military chains of command may be in y disarray. Many troops, including those actively deployed, are left to their own sate devices. Commanders of nuclear submarines and missile control centers llite wonder if the disruption is the result of a hostile attack. What sorts of decisions sud do they make with partial information?Even in the best-case scenario, our denl civilization gets set back by decades at the very least. That’s because, despite y being a relatively new phenomenon, satellites have quickly replaced more disa traditional long range technologies. The combination of global positioning and ppe internet has allowed for near-instant signals that can be synchronized worldwide. are Many systems we use daily have been built upon this foundation. Going back to d? the communication systems of the mid-20th century would not be a simple matter. In many cases, they’d have to be rebuilt from the ground up.While the sudden disappearance in this thought experiment is unlikely, there are two very real scenarios that could lead to the same results. The first is a solar flare so strong it fries satellite circuitry– as well as many other devices and power grids around the world. And the second is an orbital chain reaction of collisions. With about 7,500 metric tons of defunct spacecraft, spent boosters, and discarded equipment orbiting our planet at relative speeds up to 56,000 kilometers per hour, even small objects can be highly destructive. A single collision in space could create thousands of new pieces of debris, leading to a chain reaction. Space is huge, but many of the thousands of satellites currently in orbit share the same orbital highways for their specific purposes. And since most objects sent to space are not designed with disposal in mind, these highways only become more congested over time.The good news is, we can protect ourselves by studying our solar system, creating backup options for our satellite networks, and cooperating to avoid an orbital tragedy of the commons. The space kilometers above our heads is like our forests, the ocean’s biodiversity and clean air: If we don't treat it as a finite resource, we may wake up one day to find we no longer have it at all. Simone Ross: Jack, I would love you to tell us what Esri is and also why GIS is Ho so important.Jack Dangermond: So it is a company, it builds software products wa that are used by millions of people. Kind of like a platform technology, but not geo literally platform. It builds tools that help people do their work better. And that's a spat very general statement, but helps them do their work better using geography as ial a science and visualization as a science and technology to help them make ner better decisions, or help them be more efficient or help them communicate what vou they're doing better It's kind of mapping. I mean, the way normal people would s think of it as map-making. So this organization has 350,000 organizations that syst we support. They're our customers, you might say. And they range from NGOs, em thousands and thousands of them, working in conservation or humanitarian coul affairs, to large corporations, but our majority of users are in the public sector, in d cities and counties, in national government agencies, and they're basically help running the world, that's the way I would say it.SR: So right now, we hear a lot us about companies using tech to improve the world, but it sounds like that has desi always been baked into your DNA.JD: I grew up as a young kid in a nursery, my gn a parents were servants, and they started a little nursery to help put me through bett school, that's the way I saw it. They were immigrants and they grew plants. They er were attracted to landscaping, which I grew up understanding, so I went to futu design school, first environmental design school and then landscape re architecture and then city planning. And in that progression, I came to understand very clearly the idea of problem-solving, because that's what design really is about, you see a problem and you come up, creatively, with something that solves the problem. And at Harvard, I started to get engaged with systems and computing. And I realized, wow, this was in the '60s, you know, when the environmental movement was still just in its birthing, I saw, "Wow, you could actually apply tech to environmental design." And so this idealism that often happens when you're in school, you know, "I can really do something!" — well, I loved the idea of taking systems theories and technology and applying it to environmental design problem-solving.SR: Do you call Esri a tech company?JD: We started doing little projects, you know, locating a new town, locating a store, locating a transmission line, doing environmental studies as a foundation, using tech, to be able to make decisions, which were largely design decisions or planning decisions. And we did that for about 10 years. Just gradually growing as a professional services company, all the time continuously innovating tools that would help us do our projects better. And this idea of continuous innovation. I mean, we invented some of the first digitizing tools for maps, we invented some of the first computer map-making tools. We invented the first spacial analysis tools that were commercial in nature. And over that decade or so, customers began to say, "Gee, I'd like to do that work that you're doing, Jack." So we started to think about the idea of a product, that is, our technology that we applied on project by project could actually go into a product that people could use everywhere. And the big idea of this product, Simone, was the integration of information using geographic principles. Bringing all the different factors together to not only first help us do the projects, but then build these systems that help other people do the projects, and then later build systems. So we went from a project company to a product company that built systems that helped organizations do their work better.SR: What you're doing, I believe, is sort of the integration of human and built systems with natural systems. And then helping people visualize that and figure out then how they can design and build for that in a better, smarter way. Is that accurate?JD: That's one aspect of it. We sometimes call that geodesign. We digitize or abstract geography, the science of our world. You know, Simone, all of the factors that you think about, I think of as layers. Physical features, environmental features, demographic features. We bring all of those things together in a GIS and then by overlaying those things, we can actually do better designs. We design with all the factors holistically. That's what actually, as a student, got me excited, because I saw you could bring all of the "ologies," all the geology, the sociology, the climatology, all together, and then make better decisions on that, so I think of geography as the mother of all sciences, because it's an integrative technology. And then digital geography, what we call GIS, allows us to be able to use that instrument to empower the transformation of how people make decisions. They can look at the whole, not just one factor, not just making money, not just conserving land, not just this or that. It's optimizing many factors at the same time.Yeah, so in the retail sector, people like Starbucks or Walgreens or Walmart, all the big retailers, both here in the US but in the UK, all around the world, use geographic factors to pick the right location. They look at the demographics, the traffic, and then the large insurance companies and reinsurance companies look at all the different factors that are necessary to understand risk. And they overlay them and they model them and they visualize high-risk areas or low-risk areas. In disaster response, whether it's fire, or like today, the big earthquake in Turkey, there's a whole cycle of work that has to happen when disasters happen. You know, response, recovery, all these work activities are underpinned by having good information. And that information is geographic in nature. So disaster response, public safety, health and looking at issues today that are troubling all of us in the areas of social equity. Where is there disparity? And when something like the pandemic happens, or unemployment due to the economy happens, we can look geographically and see these factors all coming together. So it's like your mind does in many ways. I mean, we built a tool that allows you to abstract reality and see it, and then look at all the relationships between these factors in order to create understanding. So Richard Saul Wurman, the founder of TED often describes us as an understanding organization. "You're all about understanding, Jack, it's not about technology. Your users use your tools to create better understanding." And the way he describes it is understanding precedes action. This is essential to our work.SR: And it is a platform that you're building, so you're sort of connecting all these different areas of knowledge, right?JD: Today, we have what we call Web GIS. So GIS lives in the web with distributed centers of information that are pulling data out, georeferencing, and using location as a way to do the integration. We might call it mashing up different layers from distributed services or distributed sources of information. And our users are now bringing this knowledge together dynamically in things like smart cities or the popular vernacular these days is digital twins. So all of that geographic reality can now be beamed into organizations, whether they be emergency response organizations or utility organizations or government. And any of the different departments, whether they be law enforcement or you know, science, climate change, biodiversity, all of that series of issues that we're facing today can be enriched by not only bringing together the information in real time, real-time measurement seen on maps, but also integrating those like using spatial analysis or location analysis to look at the relationships and patterns. You see, it's not just seeing it, it's also explicitly understanding the relationships between something like breast cancer and pollution that might exist in a particular geography. And saying, "Aha, we can quantitatively understand these different factors and, as a result, respond."SR: So you can do that because you are putting all these different layers on and then you help visualize that.JD: Visualize it, but also spatially relate them with math and modeling. So it's not just a matter of visually overlaying material, it's a matter of connecting the geometries or the factors or the features on these maps to each other, like your mind does.SR: I have to read this, because I don't want to get it wrong. You had said at some event last year, the Geodesign Summit — which sounds fascinating to me — you said, "Transformation is not just about change, it's about leaving behind the past to focus on the future." So can you talk a little bit about that?JD: Historically, we have been at the effect of the environment. I mean, this is the history of the world. The world constrains us in what we can do as human beings and we often adapt and adopt to various environmental situations. This field of geodesign is about bringing geographic systems and knowledge into the design process so that we can actually be guided by nature and be more sensitive to it so that we can be responsive to the greater forces of the environment and do it in such a way that we can take — it's thinking of the world as a garden. It's like gardening, you must pull out the weeds, you nurture your plants, you take care of certain things, you make sure things are watered. And at this point, because of the way we are organized, and the way we think and the way our information is brought to us, we don't think as a garden, we don't think holistically, we don't think of the relationships that are in our lives, that are affecting our lives. And as a result, we're careless, we're polluting the environment, we're messing it up. I mean, on steroids, I mean, the world is really in trouble at this particular point. I mean we have the crisis of COVID, but my God, COVID is just a little wave. What's coming behind us is the climate change issue, which is not so easy to fix. There's no vaccine that's simply applied. And then behind that, there's the loss of biodiversity and behind that, it's sort of unraveling what has taken billions of years to be able to put together. And so, as human beings, my sense is we've got to be more responsive to take care of our place.SR: It's transformation with science and design as opposed to transformation brought on or foisted on us by rapid tech change. It sounds very deliberate.JD: It's very deliberate. Again, when I was a student, I got the vision or thought that we could actually do environmental planning and design and development better by thinking holistically. Bringing all the factors together. And when I launched Esri, we were starting to do projects better because we could integrate all of the factors into the design projects. Then as we started building systems, they were first small, focused systems for a particular department, like an engineering department in a city or a planning department, or a forest management organization or an oil company. They could do their work better by considering all the factors. Then — And that transformed the way projects were done, and it transformed human activities in these different departments. From there, we started to move on to the idea of transforming entire organizations. This meant entire enterprises. So from projects to systems to organizational transformation where you could actually have organizations by intention look at all the factors. And we have so many examples of this.And now, there's a fourth phase that we're very engaged in. Those three phases involve certain kinds of technology innovation, but the fourth phase is resting on the web with web services, and its intention is not to transform simply one organization at a time or one project at a time, it's to transform society so that we can raise the bar with geographic consciousness and geographic knowledge to see what our human footprint is causing. And this is so transformational, because people don't want to mess up, they want to know what to do and they want to put the foot down in the right location, they don't want to mess up wetlands by intention, they want to design with nature.SR: So you're talking about what you call a geospatial nervous system.JD: Yes, building a geospatial nervous system will allow us to guide society in such a way. And in a way, it's not somebody guiding others, it's not like that at all. It's like the internet itself. It's an interconnected network of serving knowledge, sharing knowledge, and using each other's knowledge. That is, multidisciplinary knowledge, different kinds of science knowledge to be able to see and understand before action. All we're doing is building tools that interconnect different organizations' information. And independent actors running in independent organizations all around the world are building something I like to call this geospatial infrastructure. And they're layering it on top of the web. It's like one agency is serving their information and another one is able to use it with their own information and therefore make better decisions, make more sustainable decisions. Now, they're still all independent actors. I mean, there's no control, there's no orders from headquarters. What this is is a fabric that's emerging very rapidly.Let me give a practical example. The Pacific Gas and Electric corporation, a very large organization here in California, one of the largest utilities in the world, is sharing their outage and utility information over the web with the State of California fire people and emergency management people, so that they can act better and vice versa. So they're sharing and collaborating through geographic information in whole new ways. And the FEMA, the large federal emergency management organization is sharing their emergency management information with states and cities who are overlaying their data on FEMA data, which is overlaying on top of NOAA's information on the weather and the tracking of satellites, and so on. So this web-based, internet-based system is allowing the fusion of information from many different actors. And independently, these actors are able to more holistically solve their problems.SR: Do you think we can overcome these challenges?JD: Today, both because of our increased consumption patterns and the overpopulation of the planet, we're in severe trouble. So what we can do is, I think, minimize the impact of population, we can optimize the work that we do, we can save energy, we can do all of these various things. And I have a very positive feeling about the future. This is what drives me day and night. I mean, I have had that vision for over 50 years that we must do this. It's not a question of the outcomes, it's the only way that I can think of to create a sustainable future. We must apply our best science, we must apply our best design and critical thinking, we must apply our best systems theories, we must apply our best technologies, in concert, to be able to address the great challenges that we are all facing. And Esri, as an organization, has always been and will always be all about bringing those forces together to be able to support organizations independently doing their work in this more holistic way. That's the big vision.SR: So what advice or guidance would you give to a young entrepreneur today who, sort of, wants to use tech and science to, you know, if not save the world, transform the world or improve the world, because obviously, that's where a lot of the hope and the potential is. So as someone who has been doing this for quite some time now, what would your advice be to someone like that?JD: Well, there's so many different opportunities to be able to work and contribute in the world. I was very lucky with parents who were servants and they taught me to be in service to others. This was a great value gift. When I went to Harvard, there was also a philosophy there to be in public service, to be able to focus your life, to be able to give back. And Harvard has been a huge contributor to those in public sector. In the UK, Oxford and Cambridge had that same kind of philosophy of growing the next generation that's in public service. So I think service is one of the elements. The second one is really being about staying focused on your vision. For me, my vision was this idea of bringing systems theories and science and technology together to be able to do better problem-solving. First with design and now whole organizations and society in general. That didn't just happen, it was thoughtful time spent by myself and with my wife to think about what we should with our life. And we were really lucky. We found this great thing that we were passionate about. We thought and visualized, "Yes, this is really something we could actually do." We had no idea where it would go, but at least we picked a segment of our interest to be able to follow this passion and we lucked out. And we didn't sell out, we lucked out. We were very fortunate to live very modestly for several decades to build up this organization and stay focused on our purpose. So my suggestion is, find something that you really love, that you really can contribute to, that really supports your idealism, and don't sell out for money or venture capital or borrow money, none of that actually winds up in being able to retain your idealism.SR: So I think there is so much happening on the intersection of tech and life science right now that is so exciting, but also at this intersection that you're talking about as well, and very much, I think, will be part of the solutions for us going forward.JD: I think that this big step of Web GIS that we're into right now will happen over the next few years. And it's, in some ways, just in time. Like the UN has organized their SDGs, these global sustainability issues, into this Web GIS platform. We're building a system which is bottom-up and country by country, that allows all the SDG reporting to be able to tell the world, like they did with COVID, what's happening with the other 290 indicators. Whether it's, you know, women in politics or whether it's loss of forests or water quality, this is a big deal. So it isn't just organizations anymore. We're starting to see unifiers, integrators of the individual systems into this system of systems, which I think can talk to the world and transform the world. This is essential if we are going to evolve to a society that's sustainable.SR: Great. I think that is a perfect place to stop. Thank you so much. This was really wonderful. I'm really, really glad that we got to do this. For most humans, farts are a welcome relief, an embarrassing incident, or an opportunity for a gas-based gag. But for many other creatures, farts are no laughing matter. Deep in the bowels of the animal kingdom, farts can serve as tools of intimidation, acts of self-defense, and even weapons of malodorous murder.The smelliest parts in the animal kingdom aren’t lethal, but they might ruin your trip to the beach. Seals and sea lions are well-known for having truly foul farts due to their diet. Fish and shellfish are incredibly high in sulfur. And during digestion, mammalian gut bacteria breaks down sulfur and amino acids containing sulfur to produce hydrogen disulphide, a gas with a smell resembling rotten eggs.Seals and sea lions can’t help their funky flatulence, But some animals deploy their farts strategically. Both the Eastern hognose snake and the Sonoran coral snake use a tactic called cloacal popping. This involves sucking air into their cloaca— a hole used for urinating, defecating and reproduction— and then shooting it back out with a loud pop. These pops are no more The dangerous than a sea lion’s stench, but they are effective at scaring off would-be worl predators.Meanwhile, the flatulence of beaded lacewing larvae are silent and d's deadly. Their farts contain a class of chemical known as allomone that has mos evolved specifically to paralyze termites. In fact, this allomone is so powerful, a t single fart can immobilize multiple termites for up to three hours, or even kill dan them outright. Either way, these toxic farts give beaded lacewing larvae plenty of ger time to devour prey up to three times their size.For some other animals, ous however, holding farts in can be deadly. The Bolson pupfish is a small freshwater fart fish found in northern Mexico. These fish feed on algae and other small organisms in the sediment. But during the hottest days of the summer, this algae produces a lot of gas. If a pupfish doesn’t fart this gas out, it becomes buoyant— making it easy prey for passing birds. And it isn't just predators they have to worry about. Excessive gas buildup can actually burst their digestive systems. Researchers have found groups of several hundred dead pupfish that failed to fart for their lives.Fortunately for humanity, animal farts can’t directly harm a human— outside making us lose our lunch. But in the right circumstances, some animal flatulence can create surprisingly dangerous conditions. In the fall of 2015, a tripped smoke alarm forced a plane to make an emergency landing. Upon further inspection, officials found that there was no fire— just the burps and farts of over 2,000 goats being transported in the cargo bay. The change in air pressure had caused them to pass gas en masse.Thankfully, this story of farting goats had relatively low costs. But the most dangerous flatulence in the world may actually come from a similarly unassuming mammal: the humble cow. There are nearly one billion cows in the world, most of them raised specifically for milk and meat. Like goats, cows are ruminants, which means their stomachs have four chambers, allowing them to chew, digest and regurgitate their food multiple times. This process helps them extract extra nutrients from their food, but it also produces a lot of gas. This is particularly troubling because one of the gases cows emit is methane, a major greenhouse gas that contributes heavily to global warming. One kilogram of methane traps dozens of times more heat in the atmosphere than one kilogram of carbon dioxide. And with each cow releasing up to 100 kilograms of methane every year, these animals have become one of the biggest contributors toward climate change. So while other animals may have louder, fouler, or even more toxic farts, cow flatulence may be the most dangerous gas ever to pass. Wh I grew up in Atlanta, Georgia, and I didn't know very many white people, but I en was raised in a Southern Black church that was under the shadow of white the supremacy and run by Black people who in many ways were taught to hate worl themselves. The generation that raised me was still familiar with lynchings. So in d is order to not be murdered by racists, some of the Black people in the generation bur before me learned to make themselves smaller. We couldn't be too loud, too nin smart, too attractive, too bold. On some level, they felt like anything that we did g, is that made us stand out might get us murdered.In the midst of that, I emerged, art this straight-A student who rapped, loved "Weird Al" Yankovic and read comic a books. So much for not standing out. So the grownups around me regularly was discouraged my artistry. To them, comic books were the pursuit of a kid who te didn't really understand the world. They told me that art was silly and I was in for of some hard lessons about the real world.Back then, I only had one other friend time who was into comic books and he went to a different school. So when I was ? around 11, he and I went to our very first comic book convention. They were so unused to seeing Black kids there, that one grown white man mistook me for security and showed me his convention badge in order to get in. Remember, I was 11. But me and my friend loved these conventions. Finally, we had other people to talk to about the important questions, like, why does the Hulk always wear purple pants? About a year or so later with every free moment that we had me and that same friend were actively drawing comic books. His father took notice of this and he sat us down in the living room. He loved us both, and he decided it was time to set us straight. He said, "It's great that you two love these comic books, but you need to pick a serious profession, something that's going to take care of you and your families. And you’re not going to be able to do that with comic books.” My friend's father wasn't trying to hurt us. He was trying to prepare us for the world and underneath that was this fear that was shared by my own parents. That being a Black artist would make me stand out and that I might be murdered by racists.And it's not like that was a far jump. My parents were born in the early 50s. In 1955, a white woman accused a 14-year-old boy of whistling at her. He was Black and two grown white men brutally murdered him just for her accusation. These men never went to prison. The boy's name was Emmett Till. So my parents grew up in a time where just the accusation of whistling at a white woman could get a Black boy brutally murdered. So why wouldn't they be concerned about me standing out as some bohemian artsy dude? So as a Black artist, I've had to ask myself: when the world seems like it's burning, is art really worth it?I grew up and I worked serious jobs and did art on the side. Let me tell you about the most serious job that I ever worked. I ran an insurance agency and I know everything that you've learned about me so far screams insurance agent. Predictably, I hated that job. So after a few years and against all the wise advice I heard in my life, I decided to close my insurance agency and try my hand at writing graphic novels. I wanted to address the social issues that I was passionate about. Police brutality, sexism, racism, that kind of thing. But to make it clear, I was leaving the serious insurance job in order to pursue writing comic books. You know, art, which is silly, especially in the face of a world that seemed dedicated to murdering me.This was 2016 and there was this reality show host running for president. You guys probably never heard of him, but there were all these disturbing things arising in the world. Nazis were feeling bolder. People were feeling less shame about their racism, hate crimes arising. In response, my Black and Brown friends organize public protest and boycotts. A lot of my liberal white friends were marching on the Capitol every weekend. And I wanted to write a comic book. Was I being silly? Vain? I never made a living off of art before and now I just quit my job when it seemed like the world was falling apart. Art is silly, right?I struggled with this for a while. So I took a month to travel in the UK for the first time. I was nervous about this trip because I was traveling alone. And I didn't know how people in these countries felt about Black people, but I went to Berlin, Prague, Budapest, and this tiny British town called Melksham.In Berlin, I sat down with the owner of the biggest comic book store chain there. And we talked about how as a kid, his favorite hero was Captain America, but certain issues of that comic book he never got to read as a kid because Captain America was fighting Nazis in those books. And nothing with Nazis was allowed in Germany, even if they were getting beat up. So let's think about that for a moment. In Germany, Nazis were banished from everything while here in the States, we've erected statues to Confederates who betrayed our country. Anyway, I thought about this man, this comic book fan who grew up in Germany, but fell in love with the story of an American icon. And I realized a well-written comic book or graphic novel could reach someone all the way across the world.And I thought about revolution, how whenever society needs to change, that change is inspired at least in part by the artist. I thought about how dictators and despots regularly murder and discredit artists. Hitler's people came up with a term specifically to discredit artists: degenerate art. They were burning books and paintings. But why, why were the leaders of the Nazi party dedicating their attention to destroying art? If art really has no power, if it's really a silly waste of time, then why are dictators afraid of it? Why were Nazis burning books and paintings? Why was McCarthy so dedicated to blacklisting artists in the 1950s? Why was Stalin's government so focused on censoring artists in Russia? Because art scares dictators. Because they understood something that I've been struggling to understand my entire life. Art is powerful. Art is important. Art can change hearts and minds all the way across the world.In 1894, Russian author, Leo Tolstoy wrote "The Kingdom of God Is Within You". It's a book that advocates for nonviolence. In the 1920s, Mahatma Gandhi listed Tolstoy's book as one of the three most important influences in his life. So Tolstoy inspired Gandhi. And you know who Gandhi inspired? Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. So how would the civil rights movement in America have changed if Tolstoy had never written his book? Would I even be here talking to you now? Tolstoy's book made real changes in the world by inspiring people. During the civil rights struggle, Black people would stand hand in hand as police and dogs attacked us and we'd sing gospel songs. Those songs, that art inspired these people and it helped them make it through. Activism is how we change the world. And there are different ways to engage in activism. And for me, that way is art.So I came back to the States and I wrote about all those issues that I mentioned before: the police brutality, the sexism, the racism. Honestly, I didn't know how the world was going to receive it from me. I just knew that I was tired of giving my life to things that I didn't care about. So I hired a comic book artist, I ran a Kickstarter campaign and my graphic novel became "The Burning Metronome." It's a supernatural murder mystery about otherworldly creatures who absorb magical power from human cruelty. They watch human beings and they give us the chance to choose between compassion and cruelty. In one of the stories a police officer has an opportunity to go back and undo a time when he was unnecessarily violent to someone.So what happened as a result of me writing this book? I was interviewed on TV news, newspapers. The university invited me to teach writing in their master's program. I'm a professor now. But more importantly, I was able to reach into my heart, pull out the truest parts of my soul and see it have a positive impact on other people's lives.I was signing books in this comic book store and this man made small talk with me for about 20 minutes. Eventually he said that my book made him think about how he does his job. So of course I asked, what do you do for a living? He was a police officer. So my book made a police officer think about how he does his job. That never happened when I sold insurance.I write comic books and graphic novels for a living. Now I'm a full-time artist. If I hadn't written that book, none of you would be listening to me right now. And listen, my parents weren't wrong to warn me about the lethal tendencies of this country. Just last year, a white supremacist sent me death threats over a book that I hadn't even finished writing yet. But obviously the only reason he was threatened is because he recognized the power of art to change hearts and minds all the way across the world. So I say to you now, if there's any art you want to create, if there's something in your heart, if you have something to say, we need you now. Your art can be activism. It can inspire people and change the world. If you're afraid, that's OK. Just don't let it stop you. Go make art and scare a dictator. Is art worth it? Hell yeah.Thank you. Non e If this bat were a human, she'd be in deep trouble. She’s infected with several deadly viruses, including ones that cause rabies, SARS, and Ebola. But while Wh her diagnosis would be lethal for other mammals, this winged wonder is totally y unfazed. In fact, she may even spend the next 30 years living as if this were bats totally normal– because for bats, it is. So what’s protecting her from these don' dangerous infections?To answer this question, we first need to understand the t relationship between viruses and their hosts. Every virus has evolved to infect get specific species within a class of creatures. This is why humans are unlikely to sick be infected by plant viruses, and why bees don’t catch the flu. However, viruses do sometimes jump across closely related species And because the new host has no established immune defenses, the unknown virus presents a potentially lethal challenge.This is actually bad news for the virus as well. Their ideal host provides a steady stream of resources and comes into contact with new parties to infect— two criteria that are best met by living hosts. All this to say that successful viruses don’t typically evolve adaptations that kill their hosts— including the viruses that have infected our flying friend. The deadly effects of these viruses aren’t caused by the pathogens directly, but rather, by their host’s uncontrolled immune response.Infections like Ebola or certain types of flu have evolved to strain the immune system of their mammalian host by sending it into overdrive. The body sends hordes of white blood cells, antibodies and inflammatory molecules to kill the foreign invader. But if the infection has progressed to high enough levels, an assault by the immune system can lead to serious tissue damage. In particularly virulent cases, this damage can be lethal. And even when it’s not, the site is left vulnerable to secondary infection.But unlike other mammals, bats have been in an evolutionary arms race with these viruses for millennia, and they’ve adapted to limit this kind of self-damage. Their immune system has a very low inflammatory response; an adaptation likely developed alongside the other trait that sets them apart from other mammals: self-powered flight. This energy-intensive process can raise a bat’s body temperature to over 40ºC. Such a high metabolic rate comes at a cost; flight produces waste molecules called Reactive Oxygen Species that damage and break off fragments of DNA. In other mammals, this loose DNA would be attacked by the immune system as a foreign invader. But if bats produce these molecules as often as researchers believe, they may have evolved a dampened immune response to their own damaged DNA. In fact, certain genes associated with sensing broken DNA and deploying inflammatory molecules are absent from the bat genome. The result is a controlled low-level inflammatory response that allows bats to coexist with the viruses in their systems.Even more impressive, bats are able to host these viruses for decades without any negative health consequences. According to a 2013 study, bats have evolved efficient repair genes to counteract the frequent DNA damage they sustain. These repair genes may also contribute to their long lives. Animal chromosomes end with a DNA sequence called a telomere. These sequences shorten over time in a process that many believe contributes to cell aging. But bat telomeres shorten much more slowly than their mammalian cousins— granting them lifespans as long as 41 years.Of course, bats aren’t totally invincible to disease, whether caused by bacteria, unfamiliar viruses, or even fungi. Bat populations have been ravaged by a fungal infection called white-nose syndrome, which can fatally disrupt hibernation and deteriorate wing tissue. These conditions prevent bats from performing critical roles in their ecosystems, like helping with pollination and seed dispersal, and consuming pests and insects.To protect these animals from harm, and ourselves from infection, humans need to stop encroaching on bat habitats and ecosystems. Hopefully, preserving these populations will allow scientists to better understand bats’ unique antiviral defense systems. And maybe one day, this research will help our own viral immunity take flight. The earliest known divorce laws were written on clay tablets in ancient Mesopotamia around 2000 BCE. Formally or informally, human societies across place and time have made rules to bind and dissolve couples. Inca couples, for example, started with a trial partnership, during which a man could send his partner home. But once a marriage was formalized, there was no getting out of it. Among the Inuit peoples, divorce was discouraged, but either spouse could demand one. or they could exchange partners with a different couple— as long as all four people agreed.The stakes of who can obtain a divorce, and why, have always been high. Divorce is a battlefield for some of society's most urgent issues, including the roles of church and state, individual rights, and women’s rights.Religious authorities have often regulated marriage and divorce. Muslims in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia began using the Quran’s rules in the 7th century AD— generally, a husband can divorce his wife without cause or agreement, while a wife must secure her husband’s agreement to divorce him. In Europe, Christian churches controlled divorce from the 11th century on, with the Catholic Church banning it entirely and Protestant churches allowing it in restricted circumstances, particularly adultery.In the late 18th century, a series of changes took place that would eventually shape divorce laws around the world. Following centuries of religious conflict, Europeans pushed for state governance separate from religious control. Secular courts gradually took over education, welfare, health, marriage— and divorce. The French Revolution ushered in the first of the new divorce laws, allowing men and women to divorce for a number of grounds, including adultery, violence, and desertion, or simply mutual consent.Though progress was uneven, overall this sort of legislation spread in Europe, North America and some European colonies in the 19th century. Still, A women's access to divorce often remained restricted compared to men. Adultery brie was considered more serious for women— a man could divorce his wife for f adultery alone, while a woman would need evidence of adultery, plus an hist additional offense to divorce her husband. Sometimes this double standard was ory written into law; other times, the courts enforced the laws unequally. Domestic of violence by a man against his wife was not widely considered grounds for divo divorce until the 20th century. And though new laws expanded the reasons a rce couple could divorce, they also retained the fundamental ideology of their religious predecessors: that a couple could only split if one person wronged the other in specific ways.This state of affairs really overstayed its welcome. Well into the 20th century, couples in the U.S. resorted to hiring actors to jump into bed with one spouse, fully clothed, and take photos as evidence of cheating. Finally, in the 1960s and 70s, many countries and states adopted no-fault divorce laws, where someone could divorce their spouse without proving harm, and importantly, without the other’s consent.The transition from cultural and religious rules to state sanctioned ones has always been messy and incomplete— people have often ignored their governments’ laws in favor of other conventions. Even today, the Catholic Church doesn’t recognize divorces granted by law. In some places, like parts of India, Western-style divorce laws have been seen as a colonial influence and communities practice divorce according to other religious rules. In others, though the law may allow for equal access to divorce, bias in the legal system, cultural stigma, or community pressures can make it far more difficult for certain people, almost always women. And even in the places where women aren’t disadvantaged by law or otherwise, social and economic conditions often make divorce more difficult for women. In the United States, for example, women experience economic loss far more than men after divorce.At its best, modern no-fault divorce allows people to leave marriages that make them unhappy. But dissolving a marriage is almost never as simple as sending two people their separate ways. What divorcing partners owe each other, and how they manage aspects of a once shared life remain emotionally and philosophically complex issues. Public space must be as free and abundant as the air we breathe. In our real estate-driven cities, where open space is increasingly carved up, traded and sold as a commodity, architects must defend public space, advocate for more of A it, and reclaim space that's been squandered by neglect or lack of vision.In our stea practice, this sometimes means openly sparring with a client to carve out public lthy space, or inventing stealthy, under-the-radar ways of insinuating space for the rei public into otherwise private building projects. Either way, all democracies need mag champions. It's our role, as stewards of the urban realm, to will public space into inin existence and to democratize our progressively privatized cities.In 2004, my g of studio came into the orbit of two inspired citizen activists who launched a urb campaign to save a 1.5-mile stretch of derelict infrastructure and convert it into a an public park. After years of struggle and mounting pressure from local developers, pub the High Line was saved from demolition, and we, along with our partners lic James Corner and Piet Oudolf, were put in charge of designing it. We fell in love spa with the accidental ecosystem that developed there after years of neglect. ce Rather than making architecture, we vowed to protect this place from architecture.The site was too fragile to share with the public, so we reinterpreted the DNA of this weird, self-seeded ecosystem that was half natural and half man-made, into a hybrid we called agritecture. Typically, parks serve as an escape from the city. But this park was conceived as an entry into the city, a portal into the city's subconscious. Floating over the fast-paced streets below, the High Line became a place to experience an alternative New York, with views that could never make it onto a postcard.In a culture that rewards relentless productivity, the High Line became a parenthesis in the day for doing nothing but sharing in the pleasures of being urban. Unexpectedly, the High Line became one of the most popular destinations in New York and a landmark on the world tourist map. Last year, over eight million people came.The High Line also went viral. Hundreds of cities around the world were inspired to build one of their own. We touched a global nerve. In a time of environmental awareness and shrinking resources on the planet, cities realized they could seize the opportunity to reimagine aging infrastructure as a sustainable way to give back space to the public. After all, access to green space is an environmental justice issue.In 2013, we were selected to design a park in central Moscow. Thankfully, the city pivoted from its plan to build a giant commercial development on this historically sensitive and politically charged site, adjacent to the Kremlin, Red Square and St. Basil's Cathedral. It would sit on the footprint of the former massive Khrushchev-era hotel "Rossiya."We faced a moral dilemma. Was it possible to make a democratic public space in the context of a repressive regime? Despite being a stone's throw from the Kremlin, we decided to focus on Moscow's aspirations of becoming a progressive, cosmopolitan city. As national governments are failing us, cities hold the promise of social reform. The park would be a site of civic expression, a foil to the military parades and other demonstrations of power in Red Square.Given the vulnerability that public spaces pose from opposition, governments try to control them. The architectural brief we got discouraged large open spaces, presumably out of concern for public assemblies and social unrest. Our response was to make open meadows and plazas whose uses could be open-ended. Instead of the manicured gardens and restricted inventories of official plantings, like rose bushes, we introduced a principle we called wild urbanism. The park would host native plants, sourced from the four major regional landscapes of Russia. This was our stealthy move. It was embraced as an expression of national pride. In contrast to typical parks in Moscow, where you're only permitted to walk on pathways, fenced off from vegetation, this park is unscripted and encouraged immersion in the landscape.Zaryadye Park has been immensely successful. One million people came the first month. So, not surprisingly, Putin politicized Zaryadye as his park for the people. Meanwhile, the park's liberating effect on a repressed younger generation was caught on security cameras. Government officials blamed American influence for corrupting Russian youth. But for us, this was a great sign of success. We came to believe that regimes come and go — some more slowly than others — but public spaces endure. They can work quietly, even subversively, to empower the public.The threat to democratic public space comes also from financial greed. Returning to New York, the neighborhood surrounding the High Line had transformed from a sea of open parking lots to the most expensive real estate in New York. The park inadvertently fell victim to its own success and became an agent of rapid urbanization. And with it came gentrification. I question what is the responsibility of the architect in shaping the aftermath of urban change that they've unwittingly produced.I felt compelled to respond on the site where it happened, to use the public space of the High Line as an urban stage for an epic performance called "The Mile-Long Opera." It would be a meditation on the unprecedented speed of change of the postindustrial city, its winners and losers. And it would embody a sense of nostalgia we feel for an irretrievable past and apprehension about an alienating future. People tend to think of opera as expensive and exclusive. This would welcome everyone for free.I stepped into the role of creator, director and producer, and basically off a cliff, but I brought some brilliant collaborators with me. "The Mile-Long Opera" was performed by a giant ensemble of 40 church, community and school choirs. One thousand singers in all were distributed along the 1.5-mile stretch of the High Line.(Singers singing opera)Elizabeth Diller: Each singer performed solo to a promenading audience of thousands each night for seven nights, each expressing their unique way of coping with contemporary life. Through anxiety, humor, longing, vulnerability, joy and outrage. The city was their backdrop. During some particularly dark days of political strife in the country, across a big swath of Manhattan, there was a palpable sense of shared values and citizenship among New Yorkers.But development around the High Line was not slowing down. A huge real-estate play called Hudson Yards was in the process of becoming the largest mixed-use development in US history. In its wisdom, the city of New York retained a small piece of that huge property for a yet-to-be-determined cultural facility, and asked for ideas. And while not the ideal spot, we thought, "Why not be opportunistic? Why not use the space produced by commercial development for countercultural activity?"With our partner David Rockwell, we had a vision for a building and an institutional ethos. The new entity had to be responsive to an unpredictable future in which artists would be free to work across all disciplines and all media, at all scales, indoors and out. To do so, we had to change the paradigm and challenge the inertia of architecture. Made up of a fixed building with a stack of multi-use galleries and a telescoping outer shell that deploys on demand, The Shed is able to double its footprint for large installations, performances and events. If you don't need the extra space, you can just nest the shell and open up a large outdoor space for cultural and public use. The structure deploys in five minutes, and uses the horsepower of one car engine.The Shed is a start-up realized with a group of visionary collaborators based on a hunch and sheer will.(Music)While it's a small pocket of resistance on publicly owned land and a giant commercial site, The Shed asserts its independence strongly through its content.As populations expand and city growth is inevitable, it's important for those of us who build to relentlessly advocate for a democratic public realm so that dwindling urban space is not forfeited to the highest bidder.Thank you. The last day of school was barely school. I fielded complicated questions from students who braved public transit to attend, I wiped down every desk between classes and reminded myself to breathe. I held it together so hard when students said goodbye, with a strange, scared weight on that word. Colleagues and I exchanged glances in the hallway, at once tense and comforting. We were in this together, even if we were about to part ways for several months. And when school as we know it stopped, we all took a long minute just to process Wh that. It seemed impossible. 400,000 students in Chicago now needed to learn at from home, and we would need to make that happen, both as the third-largest CO school district in the country and as the human beings who constitute it. But the VIDseemingly impossible keeps becoming reality really fast lately.So teachers 19 jumped and adapted. We learned to host online meetings, we hung whiteboards reve on our living room walls. Many teachers struggled just reaching out to see if their aled students were alright. And in addition to making remote learning plausible, abo teachers have also been organizing food drives and housing resources. They ut have made and donated masks by the thousands, and they've never stopped US reaching out.But this isn't new. This isn't dramatic heroism in the face of a sch pandemic. This is teaching. This is being invested in our communities. As ools parents, we've had to adapt too, because our working lives and our family lives -and our mental health have all collided and coagulated. Well-intentioned colorand coded schedules speckled the internet. Everyone has cried at the kitchen table, 4 at least once. Some of us several times.And then, there are the students. I've way seen students participate in class from the breakroom at work, where they are s to frontline for minimum wage to help their families. They've attended a makeshift reth funeral in the morning and a Google Meet in the afternoon. They are childcare ink providers, they are experiencing housing insecurity, they are scared, they are edu stressed, and they are children. When my son's teacher asked a screen full of cati nine-year-olds if everybody was OK, it almost broke me. "How are you?" "What on do you need?" "Is your family safe?"School without school has been traumatic, it's been makeshift, it's been messy. Parents, teachers and students have fumbled with tech, fumbled even more with expectations. And we've lost so much. And maybe, just maybe, stripped bare like it's been, we can see more. When words like "rigor," "grit" and a half dozen other educational hashtags don't seem to matter, we can see what's in front of us with new clarity. And that includes the gaps, the inequities, the failures. They're all heightened. But so are the successes. So what's working? What do kids need from their schools? And what do we really mean when we discuss, frame and fund education?As both a parent and a teacher, I keep coming back to four big ideas. None of them are new, all of them are necessary. And in them, I'm hoping other parents, other teachers and students will hear echoes of their experiences and outlines of what's possible. We can, and we must, engage parents, demand equity, support the whole student and rethink assessment.First and foremost, engaging the parents. Historically, we've isolated parents and teachers, schools and neighborhoods. We say otherwise, but the influential forces in a kid's life rarely intersect with any depth. We have parent-teacher conferences, a STEM night, a bake sale we all immediately regret agreeing to do. But the parents are here now, every day, inadvertently eavesdropping on class, because we're also making lunch or sharing a workspace. We are tutors, we are coteachers, we are all relearning algebra, and it's awkward. But maybe it's exactly what we needed, because parents are seeing how school happens, or doesn't, what excites their kids and what shuts them down, whether there's a rubric for it or not. And we’re watching our kids learn empathy and balance and time management and treeclimbing and introspection and the value of a little bit of boredom.We might not want this to last, but we can learn from it. We can keep parents engaged, beyond bake sales. We can take this time and ask parents what they and their kids need. Ask again. Ask in every language. Ask the parents who haven't been able to engage with their kids' remote learning. Meet parents where they are, and many will tell you they need us to prioritize their children's wellness, support diverse learners, protect neighborhoods from housing instability and attacks on immigrant communities. So many parents will tell us right now that they can't support their children's learning if they can't support their families.So next, we demand equity. Our school system currently serves a student population that includes 75 percent low-income households and 90 percent students of color. The fight for equity in Chicago is as old as Chicago. So what do we need right now? For starters, we need equal tech infrastructure for all. This isn't an option anymore. We have to close the tech gap. These are choices, and we don't have to keep making them. We can refuse the isolation and competition for resources that pits schools and neighborhoods against one another, get rid of rating systems and budgeting formulas that punish kids for their zip codes in a city that's been segregated since its inception.The fight for equity in Chicago did not become life or death in the pandemic — it's been life or death for a long time now. We need to care about other people's children, and not just as data points alongside our own.Third, we need to support the whole student. As much as parents might be exhausted by remote learning and can't wait to get the kids back to school, or teachers can't wait to get back into our classrooms and do some real teaching, chances are the kids miss the playground more than the classroom, the activities as much as the academics, that social emotional peace that forms the core of human learning. We will need social workers, nurses and counselors in every school, so much. We will need them as we try to help our students feel safe, process their trauma and their grief and find their way back to school. To support our students, we will also need smaller class sizes and adequate staffing across the building, something teachers have demanded again and again, with the overwhelming support of our students' parents. We will need art class, more than ever. And physical education and music programs and computer science. And if wading through conspiracy theories on the internet for the last few months has taught us anything, it's that we need to put a librarian back in every school, right now.Finally, let's rethink assessment. We can dial down the testing a lot. Elementary school students in Chicago spend up to 10 percent of their school year just taking standardized tests. We don't know how many hours of learning are lost preparing for those tests, but we know the testprep software alone costs Chicago about 10 million dollars a year. How much more could we do if we got that time and money back? And do we have to go back to obsessively quantifying everything a student attempts, weaponizing grades as a means of compliance and reinforcing inequity at every grade level? Or can we keep considering alternative models, like proficiency-based grading programs, and stop making school about scoring better than the kid next to you? 150 colleges and counting are now test-optional for admissions, including NYU, the University of Chicago and the entire California State system, because they know there's more to a student than a GPA and an SAT score.You know who else knows that? The students themselves. If we are having conversations about any of this, and not authentically including and empowering students every step of the way, we're not having conversations about any of this. We have a moment now — a short moment, and so much to get done before the comforting choruses of "back to normal" get too loud, when we can take what we've seen and experienced, plant our feet and demand better. We can make a system as massive as Chicago pivot to better serve our students, their families and our communities. If 3,000,000 teachers can relearn their jobs in a weekend, we can change school systems to better fit what we know, and what we've known for a while now. And if we can set clear expectations for our students, we can do the same for our school districts and our cities.I want to go back to school. I can't wait to go back to school. I miss the hum of the hallways and the weird energy of a room filling up with sophomores, and a better kind of exhaustion from putting my heart and my guts into what I love doing every day. But we can't miss this moment. We can't let go of the mantra that we are in this together. So don't tell us what is or isn't possible, don’t tell us it’s too hard or too expensive or too aggressive. It's been our job since the start of this pandemic — no, it's been our job since always to make what seems impossible really happen. And when the stakes are this high, and the evidence is this clear, it's our only option. Growing up, one of my fondest memories was of going to a local market with my mom every month in the small town in India where we lived. We would spend the morning walking through an intricate maze of small stores and street vendors, stopping at her favorite spots where everyone knew her, discovering what fruits were in season and what kitchenware was in stock. She would spend hours examining things from all angles, quizzing sellers on their quality and where they came from. They would show her the latest tools and gadgets, picking the ones that they knew she would like. And we always walked back happy and satisfied, our arms overflowing with dozens of shopping bags having bought so much more than what we originally intended.A decade later, as a college student in the bustling city of Delhi, my friends and I would spend a similar few hours every month on "Fashion Street," a euphemism for the row of small stores with the latest clothes at great prices. We would spend hours rummaging through piles of clothes, trying on dozens of trinkets, getting advice from each other on what looked good and what was on trend. We would then The combine everything we had bought to negotiate a big discount. Each of us had joy different roles. One was great at putting the look together. Another one was of better at negotiating the discount. And a third was always the timekeeper to sho make sure that we got back to school on time.Shopping is so much more than ppi what you buy. It's a treasure hunt to discover something new, a personalized ng recommendation from someone you trust. It's a negotiation to get that great deal and a time spent catching up with friends and family. It's social, it's interactive, and it's conversational.Over the last two decades, I have been researching how consumers in emerging markets around the world, digging beneath the surface to to truly understand who they are, how they live and what they want when they reca go shopping. Shopping, like everything else, has moved online. Shopping online ptur is great. It's convenient — at the click of a button, delivered to your doorstep. It e it has everything. It has great prices. But it's also static and impersonal. You sit onli alone in front of a computer or a mobile phone scrolling through hundreds of ne choices identified by an algorithm, delivered by a machine. When you do have a query, you interact with another machine or a bot — rarely an actual human being.What puzzles me about this is when you speak to a successful salesperson, they will always tell you that the secret to closing a sale is the conversation. People want to buy from other people. So why do we forget this most crucial ingredient when we shop online? This impersonal, anonymous experience is leaving many of us less satisfied. Returns are at an all-time high, and we're left feeling — did I buy too much? Did I buy too little? Does it really look good on me? Did I even need this? And for the one billion consumers who are new to the internet in emerging markets, shopping online can be overwhelming. They are unsure whether they'll get what they can see, unsure whether they can trust the seller. What if their money gets lost in cyberspace? The question is: can we create authentic, real, human conversation at scale? Can we create online marketplaces that are convenient and abundant and human?The good news is that the answer is yes. Companies in emerging markets around the world, in China, India and Southeast Asia, are doing just this, using a model that I call conversational commerce. It's hard to believe, isn't it? But let me give you a few examples. First: Meesho, an Indian company where you can build a trusted and authentic relationship with a seller online. The best part about shopping with my mom was that the sellers knew who she was and she knew that she could trust them. They would scroll through the hundreds of choices in the store and pick and make personalized recommendations just for her, knowing what she would like and what would work for her. It's hard to imagine such a thing happening online on that scale, but that's exactly what Meesho is doing.On Meesho, you can shop over and over and over again, but instead of interacting with a stranger or a bot, you interact with the same person: a representative of Meesho who is a real human being that you interact with via social media. Over time, she gets to know you better. She knows your likes, your dislikes, what you buy and when you buy it. And you learn to trust her. For example, she will message my sister right before Diwali with a new range of hand-loomed saris. She knows my sister loves saris — I mean, she has two cupboards full of them — but she also knows that my sister always buys a sari right before Diwali for the Indian festive season. And she also knows the kind of saris she would like. So instead of sending her hundreds of choices, she picks and chooses the colors and styles that she knows my sister would like. And then she answers her relentless questions. How does the silk feel? How does the fabric fall? Will this color look nice on me? And so many more. It truly is a hybrid model, combining the convenience and scale of a large company with the trusted personal relationship that you would expect from the shop around the corner.My next example is LazLive. On LazLive in Thailand, you can watch real sellers describing products to you via a live video stream. Now, I love handbags. And when I am in a store, I like to examine a handbag from all angles before I buy it. I need to feel the texture on my skin, hang it on my shoulder and see how it looks, see how long the strap is, open it up and look at the pockets inside to make sure that there is enough space for all the millions of things I need to put into my handbag. But when I try and buy a handbag online, I just see a few pictures: the basic shape and color and size. But that's not enough, is it?To solve this problem, LazLive has developed a platform where actual sellers — real people can share information about clothes, handbags, gadgets, cosmetics — describing the products to you, showing you what they are from the outside and the inside, explaining what they like and what they don't like. You can ask them questions and get instant responses so that you are much more comfortable with what you buy before you buy it. Over time, you can watch more videos from the same seller and they start to feel more like a friend than a faceless machine. And they help you understand what you're going to buy, stay abreast of the latest trends and often discover things that you didn't even know existed.And finally, my favorite example: Pinduoduo, one of the fastest-growing Chinese platforms, where you can actually shop with your friends online. You remember the fun I had shopping with my friends on Fashion Street, rummaging through stores, finding that perfect sandal, negotiating that great deal? Well, on Pinduoduo, you can do just that. It's lonely to shop online, and I miss hanging out with my friends. But on Pinduoduo, when I find a product, I can either buy it myself at the regular price or I can share it with my friends via social media, discuss it with them, get their advice, and if we all choose to buy it together, we get a great deal. These deals last only for a short time, just like in the real world. And there are lotteries and games and flash sales to keep all the excitement going. It's a fascinating model, really helping you rediscover the joy and connection of shopping with your friends and family in the bazaars of yore.What's important to note is that these are not stray experiments. In markets like China, India and Southeast Asia, over 500 million consumers engage in conversational commerce, and these models are growing much faster than the traditional, more static e-commerce platforms. Conversational commerce emerged to solve the needs of first-time online shoppers, but my research shows that it is equally compelling for more experienced shoppers, not just in emerging markets but around the world. In fact, when we tested conversational commerce with consumers in the US, they found it more compelling for the same reasons as consumers in Asia. Consumers who engage in conversational commerce spend 40 percent more with higher satisfaction and lower returns.I strongly believe that in the not-so-distant future, conversational commerce will become the norm, revolutionizing shopping around the world, and traditional ecommerce platforms like Amazon will need to adapt or risk becoming irrelevant.For brands, this is a crucial next step and an unprecedented opportunity, moving on from mass marketing in the 20th century and analyticsbased hyperpersonalization in the last two decades, to building a truly authentic and deep personal connection with their consumers.And for us shoppers, it brings back the magic, making online shopping finally feel human again.Thank you. On the dusty roads of a small village, a travelling salesman was having difficulty selling his wares. He’d recently traversed the region just a few weeks ago, and most of the villagers had already seen his supply. So he wandered the outskirts of the town in the hopes of finding some new customers. Unfortunately, the road was largely deserted, and the salesman was about to turn back, when he heard a high-pitched yelp coming from the edge of the forest.Following the screams to their source, he discovered a trapped tanuki. While these racoon-like creatures were known for their wily ways, this one appeared terrified and powerless. The salesman freed the struggling creature, but before he could tend to its wounds, it bolted into the undergrowth.The next day, he set off on his usual route. As he trudged along, he spotted a discarded tea kettle. It was rusty and old— but perhaps he could sell it to the local monks. The salesman polished it until it sparkled and shone.He carried the kettle to Morin-ji Temple and presented it to the solemn monks. His timing was perfect— they were in need of a large kettle for an important service, and purchased his pot for a handsome price. To open the ceremony, they began to pour cups of tea for each monk— but the kettle cooled too quickly. It had to be reheated often throughout the long service, and when it was hot, it seemed to squirm in the pourer’s hand. By the end of the ceremony, the monks felt cheated by their purchase, and called for the salesman to return and explain himself.The following morning, the salesman examined the pot, but he couldn’t find anything unusual about it. Hoping a cup of tea would The help them think, they set the kettle on the fire. Within moments, the metal began Jap to sweat. Suddenly, it sprouted a scrubby tail, furry paws and pointed nose. With ane a yelp, the salesman recognized the tanuki he’d freed.The salesman was se shocked. He’d heard tales of shape-shifting tanuki who transformed by pulling myt on their testicles. But they were usually troublesome tricksters, who played h of embarrassing pranks on travellers, or made it rain money that later dissolved the into leaves. Some people even placed tanuki statues outside their homes and tric businesses to trick potential pranksters into taking their antics kste elsewhere.However, this tanuki only smiled sweetly. Why had he chosen this r unsuspecting form? The tanuki explained that he wanted to repay the racc salesman’s kindness. However, he’d grown too hot as a tea kettle, and didn’t like oon being burned, scrubbed, or polished. The monk and salesman laughed, both impressed by this honourable trickster.From that day on, the tanuki became an esteemed guest of the temple. He could frequently be found telling tales and performing tricks that amused even the most serious monks. Villagers came from far away to see the temple tanuki, and the salesman visited often to share tea made from an entirely normal kettle. For too long, those of us who live in cities big and small have accepted the unacceptable. We accept that in cities our sense of time is warped, because we have to waste so much of it just adapting to the absurd organization and long distances of most of today's cities. Why is it we who have to adapt and to degrade our potential quality of life? Why is it not the city that responds to our needs? Why have we left cities to develop on the wrong path for so long?I would like to offer a concept of cities that goes in the opposite direction to modern urbanism, an attempt at converging life into a human-sized space rather than fracturing it into inhuman bigness and then forcing us to adapt. I call it "the 15minute city." And in a nutshell, the idea is that cities should be designed or redesigned so that within the distance of a 15-minute walk or bike ride, people should be able to live the essence of what constitutes the urban experience: to access work, housing, food, health, education, culture and leisure.Have you ever stopped to ask yourself: Why does a noisy and polluted street need to be a noisy and polluted street? Just because it is? Why can't it be a garden street lined with trees, where people can actually meet and walk to the baker and kids can walk to school? Our acceptance of the dysfunctions and indignities of modern cities has reached a peak. We need to change that. We need to change it for the sake of justice, of our well-being and of the climate.What do we need to create 15minute cities? First, we need to start asking questions that we have forgotten. For instance, we need to look hard at how we use our square meters. What is that space for? Who's using it and how? We need to understand what resources we have and how they are used. Then we need to ask what services are available in the vicinity — not only in the city center, in every vicinity. Health providers, shops, artisans, markets, sports, cultural life, schools, parks. Are there green areas? Are there water fountains placed to cool off during the frequent heat waves? We also have to ask ourselves: How do we work? Why is the place I live here, and work is far away?We need to rethink cities around the four guiding principles that are the key building blocks of the 15-minute city. First, The ecology: for a green and sustainable city. Second, proximity: to live with reduced 15distance to other activities. Third, solidarity: to create links between people. min Finally, participation should actively involve citizens in the transformation of their ute neighborhood.Don't get me wrong — I'm not angling for cities to become rural city hamlets. Urban life is vibrant and creative. Cities are places of economic dynamism and innovation. But we need to make urban life more pleasant, agile, healthy and flexible. To do so, we need to make sure everyone — and I mean everyone, those living downtown and those living at the fringes — has access to all key services within proximity.How do we get this done? The first city to adopt the 15-minute city idea is Paris, France. Mayor Anne Hidalgo has suggested a big bang of proximity, which includes, for instance, a massive decentralization, developing new services for each of the districts —(City sounds)a reduction of traffic by increasing bike lanes into spaces of leisure; new economic models to encourage local shops; building more green spaces; transform existing infrastructure, for instance, fabrication labs in sports centers or turning schools into neighborhood centers in the evenings. That's actually a golden rule of the 15-minute city: every square meter that’s already built should be used for different things. The 15-minute city is an attempt to reconcile the city with the humans that live in it.The 15-minute city should have three key features. First, the rhythm of the city should follow humans, not cars. Second, each square meter should serve many different purposes. Finally, neighborhoods should be designed so that we can live, work and thrive in them without having to constantly commute elsewhere.It's funny if you think of it: the way many modern cities are designed is often determined by the imperative to save time, and yet so much time is lost to commuting, sitting in traffic jams, driving to a mall, in a bubble of illusory acceleration. The 15-minute city idea answers the question of saving time by turning it on its head, by suggesting a different pace of life. A 15minute pace.Thank you. A few years back, my friend's dad asked me to show him my mom's house on the map. I knew we didn't have Street View in Zimbabwe yet, but I looked anyway, and of course, we couldn't find it. When you look at most mapping platforms, you will find that parts of the African continent are largely missing. And My I've wondered: Is it the people? Is it the technology? Or is it the terrain? For jour nearly a billion people on the continent, it's an accepted reality that certain ney technologies are just not built for us.When Cyclone Idai flattened parts of map Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Malawi in 2019, killing 1,300 people and displacing pin hundreds of thousands of others, it left more than just destruction. It left a new g awareness of the consequences of omission in the way we build technology. As the rescue workers arrived in the region in search of survivors, we learned that unc thousands of displaced people were in unmapped areas, making it difficult to hart reach them with much-needed food and medical supplies. There was no ed accurate accounting of what had been lost. For those in unmapped areas, a worl natural disaster often means no one will come to find you.Thankfully, as the tools d used to build some of the maps we use today become more easily accessible, we can be part of the solution. Anyone with a computer or a cell phone can play a role in improving the representation of communities that are missing accurate maps.In two weeks, I photographed 2,000 miles of Zimbabwe, and with every single mile I captured, I got closer to an answer and a better sense of what it means to not be on the map. As I started to prepare for my mapping journey, I learned that while many of the maps we use today are built on proprietary technology, the pieces that make up that canvas often have open-source origins. I could combine those pieces with off-the-shelf products to build maps that are accessible on both commercial and open-source platforms.I started with a very rudimentary setup: a 360-degree action camera stuck outside the window of my brother's car. After capturing a few dozen miles of city streets, I borrowed a proper camera from the Street View camera loan program, allowing me to capture high-resolution imagery, complete with location, speed and other vital layers of data. I adapted that camera to sit on a backpack I could carry, and with the help of a few more contraptions, we were able to mount it to the dash of a helicopter, the bow of a speedboat and the hood of an all-terrain vehicle. My journey started at Victoria Falls, one of the seven natural wonders of the world, and then I headed east to the 11th-century city of Great Zimbabwe, before retracing my footprints home, finally putting my hometown on the map. And yet, much of the region remains all but invisible on some of the most widely used mapping platforms.Beyond navigation, maps are a proxy for what we care about. They tell us about the quality of the air we breathe, the potential for renewable energy solutions and the safety of our streets. These lines retrace the journeys we've taken. In a sense, maps are a form of storytelling. When you look at the state of mapping on the African continent today, you'll find a patchwork of coverage, often driven by humanitarian need in the wake of natural disasters, rather than by deliberate and sustained efforts to build out digital infrastructure and improve overall service delivery. What the continent is lacking are maps that tell the story of how people live, work and spend time, illuminating environmental and social issues.With more than 600 million cell phones in the hands of people between Cape Town and Cairo and centers of innovation in the cities in between, this is achievable. Every single one of those devices, in the hands of a contributor to an open-source mapping platform, becomes a powerful source of imagery that forms a vital layer of data on maps.With virtual maps, mapping is no longer just about cartography. It's become a way to preserve places that are undergoing constant and sometimes dramatic change. High-resolution imagery turns maps into a living canvas on which we can instantly experience the rhythm and visual iconography of a city, often from thousands of miles away. City planners are able to measure traffic density or pick out problem intersections, and in the case of Northern Ontario, where I mapped ice roads in partnership with the local government, you can now explore 500 miles of winter roads along the western edge of the James Bay. Every winter, after 10 days of minus 20degree temperatures, engineers begin the work to build the road of the season. These roads only exist for 90 days, connecting communities across hundreds of miles of frozen tundra. Being on the winter roads of Northern Ontario after mapping parts of Namibia, one of the warmest places on the planet, exposed me to the many ways in which communities are using maps to understand the pace and impact of changes in the environment.So after mapping 3,000 miles in Zimbabwe, Namibia and Northern Ontario and publishing nearly half a million images to Street View, reaching more than 26 million people on Maps, I know it's not the technology, it's not the people, and it's clearly not the terrain. Every other day, I hear from scientists who are using maps to understand how our built environment influences health outcomes, teachers using virtual reality in the classroom and humanitarian workers using maps to protect the vulnerable. A dad wrote to me to say he'd finally been able to show his girls the house in which he grew up and the hospital in which he was born, in Harare. Think about the last time you gave directions to a stranger. When we contribute to connected maps, we're giving directions to millions. And that stranger may be the occasional tourist, a researcher, a first responder, a rescue worker working in unfamiliar terrain.As we begin to think about how to bridge the digital divide, we should go beyond the traditional narrative of data extraction and consumption and think more critically about the role you and I play in the creation of the technologies and tools we use every day. The goal is not to map every inch of the planet, but to spare a moment to think about where those tools are most needed, the consequences of our mission and the role you and I can play in filling those gaps and building a more connected world together.Thank you. In the late 13th century, Osman I established a small beylik, or principality, in what is now Turkey. In just a few generations, this beylik outmaneuvered more powerful neighbors to become the vast Ottoman empire. What enabled its rapid rise?In Osman’s time, the Anatolian peninsula was a patchwork of Turkic principalities sandwiched between a crumbling Byzantine Empire and weakened The Sultanate of the Seljuk of Rum. Osman quickly expanded this territory through a rise mixture of strategic political alliances and military conflicts with these neighbors, of attracting mercenaries first with the promise of booty, then later through his the reputation for winning.Osman was the first in a line of Ottoman rulers Otto distinguished by their political shrewdness. Often prioritizing political and military man utility over ethnic or religious affinity, they expanded their influence by fighting Em along certain sides when needed, and fighting against them when the time was pire right.After Osman’s death his son Orhan established a sophisticated military organization and tax collection system geared towards funding quick territorial expansion. The Ottomans’ first major expansion was in the Balkans, in southeast Europe. The military employed a mixture of Turkic warriors and Byzantine and other Balkan Christian converts. They captured thousands of young Christian boys from villages from across the Balkans, converted them to Islam, and trained them to become the backbone of a fierce military elite force known as the Janissaries. The captured enslaved boys could rise to the high position of a vizier in the Ottoman government. Rulers of conquered areas were also allowed, even encouraged, to convert to Islam and take positions in the Ottoman government. Meanwhile, non-Muslims who belonged to Abrahamic religions were allowed religious freedom in exchange for a tax known as Jizye, among other strict conditions— for example, they were not allowed to join the army.By the end of the 14th century, the Ottomans had conquered or subordinated most of the Anatolian beyliks as well as the Balkans. But in the first half of the 15th century, as Sultan Beyazit I focused on Western expansion, the Central Asian ruler Timur attacked from the east. He captured Beyazit and carted him off in an iron cage, sparking a ten year struggle for succession that almost destroyed the Ottoman empire.Sultan Murad II turned this trend around, but fell short of one of his loftiest goals: capturing the Byzantine capital, Constantinople. His son, Sultan Mehmed II, or Mehmed the Conqueror, vowed to succeed where his father had failed. In preparation for the attack on Constantinople, he hired a Hungarian engineer to forge the largest cannon in the world, used Serbian miners to dig tunnels under the walls of the city, and ordered his fleet of ships to be carried overland, attacking the city from an unexpected direction. He laid siege to the city and in the spring of 1453, Constantinople fell to the Ottomans. It would become the Ottoman capital, known by its common Greek name, Istanbul, meaning “to the city.”By the time Mehmed II conquered Constantinople, the city was a shadow of its former glory. Under Ottoman rule, it flourished once again. On an average day in Istanbul, you could hear people speaking Greek, Turkish, Armenian, Persian, Arabic, Bulgarian, Albanian, and Serbian. Architects like the famous Sinan filled the city with splendid mosques and other buildings commissioned by the sultans. Through Istanbul, the Otttomans brought commodities like coffee to Europe. They entered a golden age of economic growth, territorial acquisition, art and architecture. They brought together craftspeople from across Europe, Africa, the Middle East and Central Asia to create a unique blend of cultural innovation. Iznik ceramics, for example, were made using techniques from China’s Ming dynasty, reimagined with Ottoman motifs.The Ottomans would continue to expand, cementing their political influence and lucrative trade routes. The empire lasted for more than 600 years and, at its peak, stretched from Hungary to the Persian Gulf, from the Horn of Africa to the Crimean Peninsula. My parents were refugees of communism. Growing up, I watched my mom and dad work two full-time jobs without ever complaining, so my siblings and I could live a better life than they did. I was proud to be their daughter. And I understood the immigrant part of my identity well.The female part of my identity, however, was much harder for me to own. I never wanted to draw attention to my gender, because I was afraid I wouldn’t be taken seriously as a CEO. So I focused my energy on the things that I thought were important, stuff like making my team laugh. I remember I would painstakingly write and rehearse jokes before every all-hands. Or I'd be the first one in the office and the last one out, because I thought that these things mattered.When I was six months pregnant, one of our large competitors reached out, wanting to talk about acquiring us. Every startup wants the option to be bought, but it really got under my skin when during conversations with these strangers who I was negotiating with, their eyes would sometimes wander to my pregnant belly. I went into labor the same night of our user conference. The weeks leading up to the event, watching our team prepare for our big product unveiling, I wondered how many male CEOs would skip their own conference for the birth of their child. I assumed most would. But I kept reasoning with myself that if I wasn't pregnant, there'd be no question whether I'd be there or not. So I have to be there, forcing myself to parade my ninemonth pregnancy, work the halls as hosts on my feet for 14 hours was a bad idea in hindsight.The moment I arrived home, my water broke and my contractions started and I wouldn't hear my son's first cry for another 32 hours. When my baby was six weeks old, I went back to work. Our M and A had fallen Ho through by then, and I was determined to fundraise a war chest to fight them w back. But I was still bleeding from several tears in my vagina from pushing out a vuln baby.To this day, I still ask myself why I rushed back to work when I wasn't era ready. And I realize now it was because I was afraid. I was so afraid of what bilit people might think of me as a new mother and CEO. I was afraid that they would y think that my priorities had changed. So I pressured myself into proving to mak everyone that I was as dedicated to the company as ever.I would spend the next es two months fundraising to secure our war chest. I had a full schedule and I you needed to pump milk, but I didn't have the courage to ask for 50 million dollars a and ask to use their mother's room. So how does one pump milk on Sand Hill bett Road? Well, I would park my car in front of someone's super nice home in Palo er Alto. I'd undress and extract milk from my breasts with a silicone hand pump. It lead worked out, I guess. We secured a lead investor for our series C and then our er competitors came back with a revised offer, and we decided to sell to them for 875 million dollars.A few months after the acquisition I became pregnant for the second time. And shortly after, I found out I had a miscarriage. While with my team ... I felt it slip out of me. I went to the bathroom ... and it fell to the floor. I didn't know what to do, so I just walked back out to the team, pretending as if nothing happened.It took going through infertility, miscarriage, pregnancy, giving birth without any drugs, while running a company for me to realize how wrong I was to hide my womanhood as if it's something I'm ashamed of. For so long, I thought I had to be what I thought a good male CEO looked like so that I wouldn't be judged or treated differently. I was so constricted by my belief that businesses value maleness more. And it made me afraid to be a woman, which meant I hid a massive part of who I was from everyone. When I dared to be fully myself, when I dared to trust and share my frustrations and my anger and my sadness and my tears with my team, I became a much happier and more effective leader because I was finally honest in who I was. And my team responded to that.One of the most important side effects of leading as my complete raw self was seeing our culture evolve to a more close-knit and effective version of itself. I remember we had several back to back rough quarters. It felt like everything was in shambles and I didn't have time to prepare for an all-hands. And then it was time for me to speak. So I walked up to the mic cold and I started talking openly about my concerns, my concerns on competition, the mistakes we had made in sales strategy, really exposing the weaknesses of our company. And I asked the team for help. That completely changed the conversation and how we would build and solve problems together.As we collectively brought our full selves to work, we were able to accomplish so much more in terms of revenue growth and the most products shipped the company had seen. And it progressed us from a startup to mediumsized business. Whoever you are, if you're thinking about starting a startup, or you’re thinking about leading, do it and don't be afraid to trust and be yourself completely. I wish I knew that a decade ago. And learn from my mistakes. If you find yourself fundraising on Sand Hill, needing to pump milk, go use their niceass mother’s rooms.Thank you. Wh In 1967, researchers from around the world gathered to answer a long-running o scientific question— just how long is a second? It might seem obvious at first. A deci second is the tick of a clock, the swing of a pendulum, the time it takes to count des to one. But how precise are those measurements? What is that length based how on? And how can we scientifically define this fundamental unit of time?For most lon of human history, ancient civilizations measured time with unique calendars that g a tracked the steady march of the night sky. In fact, the second as we know it sec wasn’t introduced until the late 1500’s, when the Gregorian calendar began to ond spread across the globe alongside British colonialism. The Gregorian calendar is? defined a day as a single revolution of the Earth about its axis. Each day could be divided into 24 hours, each hour into 60 minutes, and each minute into 60 seconds. However, when it was first defined, the second was more of a mathematical idea than a useful unit of time. Measuring days and hours was sufficient for most tasks in pastoral communities. It wasn’t until society became interconnected through fast-moving railways that cities needed to agree on exact timekeeping. By the 1950’s, numerous global systems required every second to be perfectly accounted for, with as much precision as possible. And what could be more precise than the atomic scale?As early as 1955, researchers began to develop atomic clocks, which relied on the unchanging laws of physics to establish a new foundation for timekeeping. An atom consists of negatively charged electrons orbiting a positively charged nucleus at a consistent frequency. The laws of quantum mechanics keep these electrons in place, but if you expose an atom to an electromagnetic field such as light or radio waves, you can slightly disturb an electron’s orientation. And if you briefly tweak an electron at just the right frequency, you can create a vibration that resembles a ticking pendulum.Unlike regular pendulums that quickly lose energy, electrons can tick for centuries. To maintain consistency and make ticks easier to measure, researchers vaporize the atoms, converting them to a less interactive and volatile state. But this process doesn’t slow down the atom’s remarkably fast ticking. Some atoms can oscillate over nine billion times per second, giving atomic clocks an unparalleled resolution for measuring time. And since every atom of a given elemental isotope is identical, two researchers using the same element and the same electromagnetic wave should produce perfectly consistent clocks.But before timekeeping could go fully atomic, countries had to decide which atom would work best. This was the discussion in 1967, at the Thirteenth General Conference of the International Committee for Weights and Measures. There are 118 elements on the periodic table, each with their own unique properties. For this task, the researchers were looking for several things. The element needed to have long-lived and high frequency electron oscillation for precise, long-term timekeeping. To easily track this oscillation, it also needed to have a reliably measurable quantum spin— meaning the orientation of the axis about which the electron rotates— as well as a simple energy level structure— meaning the active electrons are few and their state is simple to identify. Finally, it needed to be easy to vaporize.The winning atom? Cesium133. Cesium was already a popular element for atomic clock research, and by 1968, some cesium clocks were even commercially available. All that was left was to determine how many ticks of a cesium atom were in a second. The conference used the most precise astronomical measurement of a second available at the time— beginning with the number of days in a year and dividing down. When compared to the atom’s ticking rate, the results formally defined one second as exactly 9,192,631,770 ticks of a cesium-133 atom.Today, atomic clocks are used all over the Earth— and beyond it. From radio signal transmitters to satellites for global positioning systems, these devices have been synchronized to help us maintain a globally consistent time— with precision that’s second to none. (Māori) Kia ora koutou, everyone. I want to you today about democracy, about the struggles that it's experiencing, and the fact that all of us together in this room might be the solution. But before I get onto that, I want to take a little detour into the past.This is a picture from Athens, or more specifically, it's a picture of a place called the Pnyx, which is where, about two and a half thousand years ago, the ancient Greeks, the ancient Athenians, gathered to take all their major political decisions together. I say the ancient Athenians. In fact, it was only the men. Actually, it was only the free, resident, property-owning men. But with all those failings, it was still a revolutionary idea: that ordinary people were capable of dealing with the biggest issues of the time and didn't need to rely on a single supposedly superior ruler. It was, you know, it was a way of doing things, it was a political system. It was, you could say, a democratic technology appropriate to the time.Fast-forward to the 19th century when democracy was having another flourishing moment and the democratic technology that they were using then was representative democracy. The idea that you have to elect a bunch of people — gentlemen, in the picture here, all gentlemen, at the time, of course — you had to elect them to look after your best interests. And if you think about the conditions of the time, the fact that it was 3 impossible to gather everybody together physically, and of course they didn’t way have the means to gather everyone together virtually, it was again a kind of s to democratic technology appropriate to the time.Fast-forward again to the 21st upg century. And we're living through what's internationally known as the crisis of rad democracy. What I would call the crisis of representative democracy, the sense e that people are falling out of love with this as a way of getting things done, that dem it's not fundamentally working. And we see this crisis take many forms in many ocr different countries. So in the UK, you see a country that now at times looks acy almost ungovernable. In places like Hungary and Turkey, you see very for frighteningly authoritarian leaders being elected. In places like New Zealand, we the see it in the nearly one million people who could have voted at the last general 21st election, but who chose not to.Now these kinds of struggles, these sort of crises cent of democracy have many roots, of course, but for me, one of the biggest ones is ury that we haven't upgraded our democratic technology. We're still far too reliant on the systems that we inherited from the 19th and from the 20th century. And we know this because in survey after survey people tell us, they say, “We don’t think that we’re getting a fair share of decision-making power, decisions happen somewhere else." They say, “We don’t think the current systems and our government genuinely deliver on the common good, the interests that we share as citizens." They say, “We’re much less deferential than ever before, and we expect more than ever before, and we want more than ever before to be engaged in the big political decisions that affect us.” And they know that our systems of democracy have just not kept pace with either the expectations or the potential of the 21st century. And for me, what that suggests is that we need a really significant upgrade of our systems of democracy.That doesn't mean we throw out everything that's working about the current system, because we will always need representatives to carry out some of the complex work of running the modern world. But it does mean a bit more Athens and a bit less Victorian England. And it also means a big shift towards what's generally called everyday democracy. And it gets this name because it's about finding ways of bringing democracy closer to people, giving us more meaningful opportunities to be involved in it, giving us a sense that we're not just part of government on one day, every few years when we vote, but we're part of it every other day of the year.Now that everyday democracy has two key qualities that I've seen prove their worth time and again, in the research that I've done. The first is participation because it's only if we as citizens, as much as possible, get involved in the decisions that affect us, that we'll actually get the kind of politics that we need, that we'll actually get our common good served. The second important quality is deliberation. And that's just a fancy way of saying highquality public discussion, because its all very well people participating, but it's only when we come together and we listen to each other, we engage with the evidence, and reflect on our own views, that we genuinely bring to the surface the wisdom and the ideas that would otherwise remain scattered and isolated amongst us as a group. It's only then that the crowd really becomes smarter than the individual.So if we ask what could this abstract idea, this everyday democracy actually look like in practice, the great thing is we don't even have to use our imaginations because these things are already happening in pockets around the world. One of my favorite quotes comes from the science fiction writer, William Gibson, who once said, "The future's already here, it's just unevenly spread." So what I want to do is share with you three things from this unevenly spread future that I'm really excited about in terms of upgrading the system of democracy that we work with. Three components of that potential democratic upgrade.And the first of them is the citizens assembly. And the idea here is that a polling company is contracted by government to draw up, say, a hundred citizens who are perfectly representative of the country as a whole. So perfectly representative in terms of age, gender, ethnicity, income level and so on. And these people are brought together over a period of weekends or a week, paid for their time and asked to discuss an issue of crucial public importance. They're given training on how to discuss issues well with each other, which we'll all know of course, from our experiences of arguing online, if nowhere else, is not an ability that we're all born with innately, more’s the pity. In the citizens assembly, people are also put in front of evidence and the experts, and they're given time to discuss the issue deeply with their fellow citizens and come to a state of consensus recommendations. So these kinds of assemblies have been used in places like Canada, where they were used to draw up a new national action plan on mental health for the whole country. A citizens assembly was used recently in Melbourne to basically lay the foundation of a new 10-year financial plan for the whole city. So these assemblies can have real teeth, real weight.The second key element of the democratic upgrade: participatory budgeting. The idea here is that a local council or a city council takes its budget for spending on new buildings, new services, and says, we're going to put a chunk of this up for the public to decide, but only after you've argued the issues over carefully with each other. And so the process starts at the neighborhood level. You have people meeting together in community halls, in basketball courts, making the trade-offs, saying, "Well, are we going to spend that money on a new health center, or are we going to spend it on safety improvements to a local road?" People using their expertise in their own lives. Those discussions are then pushed up to the suburb or ward level, and then again, to the city level and in full view of the public, the public themselves makes the final allocation of that budget. And in the city where this all originated, Porto Alegre in Brazil, a place with about a million inhabitants, as many as 50,000 people get engaged in that process every year.The third element of the upgrade: online consensus forming. In Taiwan a few years ago, when Uber arrived on their shores, the government immediately launched an online discussion process using a piece of software called Polis, which is also coincidentally, or not coincidentally, what the ancient Athenians call themselves when they were making their collective decisions. And the way Polis works is it groups people together, and then using machine learning and a bunch of other techniques, it encourages good discussion amongst those participating. It allows them to put up proposals, which are then discussed, knocked back, refined, until they reach something like 80 percent consensus. And in the time, in this case, within about four weeks, this process had yielded six recommendations for how people wanted to see Uber regulated. And those, almost all of them, were immediately picked up by the government and accepted by Uber.Now I find these examples really inspiring. People sometimes ask me why I'm an optimist and a large part of the answer is these kinds of innovations, because I think they, you know, they're really show us that we can have a kind of politics which is deeply responsive to our needs as citizens, but which avoids the peril of the threats to human liberties, the threats to civil liberties that authoritarian populism descends into. They show us that even though we live in what looks like quite a dark time, there are things that act a bit like emergency lighting, guiding us towards something better. And although these are all ideas from the Western tradition, they can also be combined with, adapted by Indigenous traditions that also value turn-taking in speech and consensus decision-making. And the thread that binds all these traditions together is essentially a faith in other people. A faith in people's ability to handle difficult decisions, a faith in people's ability to come together and make political decisions intelligently. In the Polis example, we see that government can be agile and nimble in the face of tech disruption. In the participatory budgeting, we see that we can build systems that are disproportionately used by poor people and which deliver infrastructure that is better quality than the traditional systems. In citizens assemblies, the experts who observed them time and again, say that in those good conditions people's ability to listen to others, to engage with the evidence, and to shift from their entrenched views is consistently astounding.And that's a really, really hopeful finding, because, you know, I think we live at a time where you see right around the world, huge suspicion of other people, of other citizens, huge doubts about whether people are really able to bear the burden of decision-making that democracy places on them. But if you're worried, for instance, about whether a lot of people out there, you know, are misinformed or fallen prey to online propaganda, what better way to push back against that than by ensuring that they're placed in forums. Forums like the New England town hall meetings shown here. Forums where they have to come faceto-face with other people, or at least be in close virtual contact, where they have to justify their opinions, have to deal with the evidence, and are encouraged to step away from their prejudices.The Canadian philosopher Joseph Heath says that rationality, our ability to make good decisions, isn't something that we achieve as individuals, if we achieve it at all. It's something we achieve in groups. Our best hope of rationality is each other. Or to put the thing a different way, the problem with democracy is not other people, it's not other citizens. The problem is the situations in which they — in which we all — have been asked to do our democratic work. The problem is the outdated democratic technology that we've all been forced to use. And so what these examples show to me, the reason I find them inspiring, is that I think they demonstrate that if you get the situations right, if you get the technology upgraded, then actually the things that we do when we come together as citizens can be astounding, and together, we really can build a form of democracy that's genuinely fit for the 21st century.Thank you very much.(Applause) Woman: Doc? We're ready for you. Mehret Mandefro: OK.Man 1: Here we go. Places, please. Last looks.Man 2: We're at roll time.Man 3: Rolling! Man 2: Roll cameras.Man 3: A speed, B speed, C speed.Man 1: Marker. And ... action.MM: I started making movies 15 years ago, during my internal medicine residency, as one does. I was doing HIV disparities research amongst Black women, and that work turned into a documentary, and I've been making movies ever since. I like to think of the movies and shows I create as a kind of visual medicine. By that I mean I try to put stories on the screen that address large social barriers, like racism in America, gender inequities in Ethiopia and global health disparities. And it's always my hope that audiences leave inspired to take actions that will help people hurdle those barriers. Visual medicine.Most of the time, I live and work in Ethiopia, the country I was born in, and currently, I sit on the advisory council of the Ethiopian Government's Jobs Creation Commission. Now, I'm sure you're wondering what a doctor-turned-filmmaker, not economist, is doing working with the Jobs Creation Commission. Well, I believe the creative industries, like film and theater, design and even fashion, can promote economic growth and democratic ideals in any country. I've seen it happen, I've helped it happen, and I'm here to tell you a little bit more.But first, some context. Over the past 15 years, Ethiopia has had amongst the fastest-growing economies in the world. This growth has led to a reduction in poverty. But according to 2018 Ho numbers, unemployment rates in urban areas is around 19 percent, with higher wa unemployment rates amongst youth ages 15 to 29. No surprise, those numbers stro are even higher among young women. Like the rest of Africa, Ethiopia's ng population is young, which means as the urban labor market continues to grow, crea people are aging into the workforce, and there aren't enough jobs to go tive around.So put yourselves in the shoes of any government struggling to create ind enough good-paying jobs for a growing population. What do you do? I'm ustr guessing your first thought isn't, "Hey, let's expand the creative sector." We've y been conditioned to think of the arts as a nice thing to have, but not really as help having a place at the economic growth and security table. I disagree.When I s moved to Ethiopia four years ago, I wasn't thinking about these unemployment eco issues. I was actually thinking about how to expand operations of a media no company I had cofounded, Truth Aid, in the US. Ethiopia seemed like an exciting mie new market for our business. By the end of my first year there, I joined a s fledgling TV station that exploded onto the media scene, Kana TV, as its first thri executive producer and director of social impact. My job was to figure out how to ve produce premium original content in Amharic, the official language, in a labor market where the skills and education for film and TV was limited. There was really only one way we could do it. We would have to invest heavily in training.I was charged with training the scripted drama team, and there was really only one way we could do that: on the job, paying my employees to make TV while they learned how to make TV. Their average age was 24, it was their first job out of university, and they were eager to learn. We built a world-class studio and began.The first show we created as a product of our training was a scripted series with a powerful family at the center called "Inheritance." The second show was Ethiopia's first teen drama, called "Yegna," and was made in partnership with the nonprofit Girl Effect. These shows turned the cast into overnight stars and won audiences over, and the best part of my job quickly became running what was essentially a content production talent training factory. Kana would go on to make several original content shows, including a health talk show I created called "Hiyiweti," which translates into "my life."Now, this is obviously great for Kana, but we were doing something bigger. We were creating a model for how training becomes employment in a market where creating new jobs, especially as it relates to young people, is among the largest of demographic challenges.Now, you can't say you took a bite out of a large social problem like unemployment if the jobs you create only serve the interests of a single private sector company, which is why I didn't stop at TV. I wanted the crews I had trained to have exposure to international standard production and was so thrilled when a Canadian-Irish coproduction that I was executive producing came to Ethiopia to shoot the feature film "Sweetness in the Belly." I contacted the CEO of the state-owned tours in Ethiopia to see if we could use this film as a learning case study for how government can support filmmaking and filmmakers. The argument was, films can promote economic growth and attract tourism dollars in two key ways: by bringing production work to Ethiopia and, more importantly, by promoting Ethiopia and its unique cultural assets to the world. The latter taps into a nation's expressive power.The government was incredibly receptive and supportive and ended up providing logistical and security support above and beyond what a lone producer could provide on her own, especially to such a large film crew. With their help, we were able to complete shooting the feature film under very challenging conditions, and I was able to hire my TV crews so they could deepen their experiences and work alongside a world-class film crew. This meant our employees could mature and grow and move up their own respective career ladders, not just in our company but in the market at large. Members of our crew have gone on to start their own production companies, joined ad agencies, communication firms, even other TV stations. To me, this multiplier effect is what it's all about.But the story gets better. This was right around the time the Jobs Creation Commission hired me to conduct a diagnostic study to assess the unmet needs of subsectors like film, visual arts and design and see what government could do to respond to those needs. After we completed the study, we made policy recommendations to incorporate the creative economy in the National Jobs Action Plan as a high-potential services industry. This led to a larger effort called Ethiopia Creates, which is just beginning to organize the creative industry entrepreneurs in the sector so the sector can thrive. Ethiopia Creates recently organized a film export mission to the European film market, where a team of Ethiopian filmmakers were able to pitch their projects for potential financing opportunities.Now, putting culture on the economic agenda is an incredibly important milestone. But the truth of the matter is, there's far more at stake than just jobs. Ethiopia is at a critical juncture, not just economically but democratically. It seems like the rest of the world is at a similar make-or-break moment. From my perspective on the ground in Ethiopia, the country can go one of two ways: either down a path of inclusive, democratic participation, or down a more divisive path of ethnic divisions. If we all agree that the good way to go is down the inclusive path, the question becomes: How do we get there?I would argue one of the best ways to safeguard democracy is to expose everyone to each other's stories, music, cultures and histories, and of course, it's the creative economy that does that best. It's the sector that helps teach civil society how to access new ideas that are free of bias. Artists have long found ways to inspire inclusion, tell stories and make music for lasting political impact. The late, great American hero, Congressman John Lewis, understood this when he said, "Without dance, without drama, without photography, the civil rights movement would have been like a bird without wings."(Bell rings)Man 1: OK, we're back.MM: Now imagine how much more effective music, films and arts would be if artists had good-paying jobs and the government supported them. In this case, economic growth and democratic growth go hand in hand. I think any government that views arts as a nice thing to have as opposed to a must-have is kidding itself. Arts and culture in all of their forms are indispensable for a country's economic and democratic growth. It's precisely countries like Ethiopia that can't afford to ignore the very sector that has the potential to make the greatest civic impact. So just as John Lewis understood that the civil rights movement could not take flight without the arts, without a thriving creative sector that is organized like an industry, Ethiopia's future, or any other country at its moment of reckoning, cannot take flight. The economic and democratic gains these industries afford make the creative economy essential to development and progress.Thank you.Man 1: And ... cut!(Applause and cheers) AI could add 16 trillion dollars to the global economy in the next 10 years. This economy is not going to be built by billions of people or millions of factories, but by computers and algorithms. We have already seen amazing benefits of AI in simplifying tasks, bringing efficiencies and improving our lives. However, when it comes to fair and equitable policy decision-making, AI has not lived up to its promise. AI is becoming a gatekeeper to the economy, deciding who gets a job and who gets an access to a loan. AI is only reinforcing and accelerating our bias at speed and scale with societal implications. So, is AI failing us? Are we designing these algorithms to deliver biased and wrong decisions?As a data scientist, I'm here to tell you, it's not the algorithm, but the biased data that's responsible for these decisions. To make AI possible for humanity and society, we need an urgent reset. Instead of algorithms, we need to focus on the data. We're spending time and money to scale AI at the expense of designing and collecting high-quality and contextual data. We need to stop the data, or the biased data that we already have, and focus on three things: data infrastructure, data quality and data literacy.In June of this year, we saw embarrassing bias in the Duke University AI model called PULSE, which enhanced a blurry image into a recognizable photograph of a person. This algorithm incorrectly enhanced a nonwhite image into a Caucasian image. African-American images were underrepresented in the training set, leading to wrong decisions and predictions. Probably this is not the first time you have seen an AI misidentify a Black person's image. Despite an improved AI methodology, the underrepresentation of racial and ethnic populations still left us with biased results.This research is academic, however, not all data biases are academic. Biases have real consequences.Take the 2020 US Census. The census is the foundation for many social and economic policy decisions, therefore the census is required to count 100 percent of the population in the United States. However, with the pandemic and the politics of the citizenship question, undercounting of minorities is a real possibility. I expect significant undercounting of minority groups who are Ho hard to locate, contact, persuade and interview for the census. Undercounting w will introduce bias and erode the quality of our data infrastructure.Let's look at bad undercounts in the 2010 census. 16 million people were omitted in the final data counts. This is as large as the total population of Arizona, Arkansas, Oklahoma kee and Iowa put together for that year. We have also seen about a million kids ps under the age of five undercounted in the 2010 Census.Now, undercounting of us minorities is common in other national censuses, as minorities can be harder to fro reach, they're mistrustful towards the government or they live in an area under m political unrest.For example, the Australian Census in 2016 undercounted goo Aboriginals and Torres Strait populations by about 17.5 percent. We estimate d AI undercounting in 2020 to be much higher than 2010, and the implications of this bias can be massive.Let's look at the implications of the census data. Census is the most trusted, open and publicly available rich data on population composition and characteristics. While businesses have proprietary information on consumers, the Census Bureau reports definitive, public counts on age, gender, ethnicity, race, employment, family status, as well as geographic distribution, which are the foundation of the population data infrastructure. When minorities are undercounted, AI models supporting public transportation, housing, health care, insurance are likely to overlook the communities that require these services the most.First step to improving results is to make that database representative of age, gender, ethnicity and race per census data. Since census is so important, we have to make every effort to count 100 percent. Investing in this data quality and accuracy is essential to making AI possible, not for only few and privileged, but for everyone in the society.Most AI systems use the data that's already available or collected for some other purposes because it's convenient and cheap. Yet data quality is a discipline that requires commitment — real commitment. This attention to the definition, data collection and measurement of the bias, is not only underappreciated — in the world of speed, scale and convenience, it's often ignored.As part of Nielsen data science team, I went to field visits to collect data, visiting retail stores outside Shanghai and Bangalore. The goal of that visit was to measure retail sales from those stores. We drove miles outside the city, found these small stores — informal, hard to reach. And you may be wondering — why are we interested in these specific stores? We could have selected a store in the city where the electronic data could be easily integrated into a data pipeline — cheap, convenient and easy. Why are we so obsessed with the quality and accuracy of the data from these stores? The answer is simple: because the data from these rural stores matter. According to the International Labour Organization, 40 percent Chinese and 65 percent of Indians live in rural areas. Imagine the bias in decision when 65 percent of consumption in India is excluded in models, meaning the decision will favor the urban over the rural.Without this rural-urban context and signals on livelihood, lifestyle, economy and values, retail brands will make wrong investments on pricing, advertising and marketing. Or the urban bias will lead to wrong rural policy decisions with regards to health and other investments. Wrong decisions are not the problem with the AI algorithm. It's a problem of the data that excludes areas intended to be measured in the first place. The data in the context is a priority, not the algorithms.Let's look at another example. I visited these remote, trailer park homes in Oregon state and New York City apartments to invite these homes to participate in Nielsen panels. Panels are statistically representative samples of homes that we invite to participate in the measurement over a period of time. Our mission to include everybody in the measurement led us to collect data from these Hispanic and African homes who use over-the-air TV reception to an antenna. Per Nielsen data, these homes constitute 15 percent of US households, which is about 45 million people. Commitment and focus on quality means we made every effort to collect information from these 15 percent, hard-to-reach groups.Why does it matter? This is a sizeable group that's very, very important to the marketers, brands, as well as the media companies. Without the data, the marketers and brands and their models would not be able to reach these folks, as well as show ads to these very, very important minority populations. And without the ad revenue, the broadcasters such as Telemundo or Univision, would not be able to deliver free content, including news media, which is so foundational to our democracy.This data is essential for businesses and society. Our once-in-alifetime opportunity to reduce human bias in AI starts with the data. Instead of racing to build new algorithms, my mission is to build a better data infrastructure that makes ethical AI possible. I hope you will join me in my mission as well.Thank you. Maria walked into the elevator at work. She went to press the button when her Ho phone fell out of her hand. It bounced on the floor and — went straight down that w little opening between the elevator and the floor. And she realized it wasn't just you her phone, it was her phone wallet that had her driver's license, her credit card, r her whole life. She went to the front desk to talk to Ray, the security guard.Ray brai was really happy to see her. Maria is one of the few people that actually stops n and says hello to him each day. In fact, she's one of these people that knows res your birthday and your favorite food, and your last vacation, not because she's pon weird, she just genuinely likes people and likes them to feel seen. She tells Ray ds what happened, and he said it's going to cost at least 500 dollars to get her to phone back and he goes to get a quote while she goes back to her desk. Twenty stor minutes later, he calls her and he says, "Maria, I was looking at the inspection ies certificate in the elevator. It's actually due for its annual inspection next month. I'm going to go ahead and call that in today and we'll be able to get your phone and back and it won't cost you anything."The same day this happened, I read an why article about the CEO of Charles Schwab, Walter Bettinger. He's describing his they straight-A career at university going in to his last exam expecting to ace it, when 're the professor gives one question: "What is the name of the person that cleans cru this room?" And he failed the exam. He had seen her, but he had never met her cial before. Her name was Dottie and he made a vow that day to always know the for Dotties in his life because both Walter and Maria understand this power of lead helping people feel seen, especially as a leader.I used that story back when I ers worked at General Electric. I was responsible for shaping culture in a business of 90,000 employees in 150 countries. And I found that stories were such a great way to connect with people and have them think, "What would I do in this situation? Would I have known Dottie or who are the Dotties I need to know in my life?" I found that no matter people's gender or their generation or their geography in the world, the stories resonated and worked. But in my work with leaders, I've also found they tend to be allergic to telling stories. They're not sure where to find them, or they're not sure how to tell them, or they think they have to present data and that there's just not room to tell a story.And that's where I want to focus today. Because storytelling and data is actually not this either-or. It's an "and," they actually create this power ballad that connects you to information differently. To understand how, we have to first understand what happens neurologically when you're listening to a story and data.So as you're in a lecture or you're in a meeting, two small parts of your brain are activated, Wernicke and Broca's area. This is where you're processing information, and it's also why you tend to forget 50 percent of it right after you hear it. When you listen to a story, your entire brain starts to light up. Each of your lobes will light up as your senses and your emotions are engaged. As I talk about a phone falling and hitting the ground with a thud your occipital and your temporal lobes are lighting up as though you are actually seeing that falling phone and hearing it hit with a thud. There's this term, neural coupling, which says, as the listener, your brain will light up exactly as mine as the storyteller. It mirrors this activity as though you are actually experiencing these things.Storytelling gives you this artificial reality. If I talked to you about, like, walking through the snow and with each step, the snow is crunching under my shoes, and big, wet flakes are falling on my cheeks, your brains are now lighting up as though you are walking through the snow and experiencing these things. It's why you can sit in an action movie and not be moving, but your heart is racing as though you're the star onscreen because this neural coupling has your brain lighting up as though you are having that activity.As you listen to stories, you automatically gain empathy for the storyteller. The more empathy you experience, the more oxytocin is released in your brain. Oxytocin is the feel-good chemical and the more oxytocin you have, the more trustworthy you actually view the speaker. This is why storytelling is such a critical skill for a leader because the very act of telling a story makes people trust you more.As you begin to listen to data, some different things happen. There are some misconceptions to understand. And the first is that data doesn't change our behavior, emotions do. If data changed our behavior, we would all sleep eight hours and exercise and floss daily and drink eight glasses of water. But that's not how we actually decide. Neuroscientists have studied decision-making, and it starts in our amygdala. This is our emotional epicenter where we have the ability to experience emotions and it's here at a subconscious level where we begin to decide. We make choices to pursue pleasure or to avoid risk, all before we become aware of it. At the point we become aware, where it comes to the conscious level, we start to apply rationalization and logic, which is why we think we're making these rationallybased decisions, not realizing that they were already decided in our subconscious.Antonio Damasio is a neuroscientist that started to study patients that had damage to their amygdala. Fully functioning in every way, except they could not experience emotions. And as a result, they could not make decisions. Something as simple as "do I go this way or this way" they were incapable of doing, because they could not experience emotions. These were people that were wildly successful before they had the damage to their amygdala and now they couldn't complete any of their projects and their careers took big hits, all because they couldn't experience emotions where we decide.Another data misconception. Data never speaks for itself. Our brains love to anticipate and as we anticipate, we fill in the gaps on what we're seeing or hearing with our own knowledge and experience and our own bias. Which means my understanding of data is going to differ from yours, and it's going to differ from yours, because we're all going to have our own interpretation if there isn't a way to guide us through.Now I'm not suggesting that data is bad and story is good. They both play a key role. And to understand how, you have to see what makes a great story. It's going to answer three questions. The first is: What is the context? Meaning, what's the setting, who is involved, why should I even care? What is the conflict, where is that moment where everything changes? And what is the outcome? Where is it different, what is the takeaway? A good story also has three attributes, the first being it is going to build and release tension. So because our brains love to anticipate, a great story builds tension by making you wonder: "Where is she going with this?" "What's happening next," right? A good story keeps you, keeps your attention going. And it releases it by sharing something unexpected and it does this over and over throughout the story.A great story also builds an idea. It helps you see something that you can no longer unsee, leaving you changed, because stories actually do leave you changed. And a great story communicates value. Stanford has done research on one of the best ways to shape organizational culture, and it is storytelling, because it's going to demonstrate what you value and encourage or what you don't value and what you discourage. As you start to write your power ballad, most people want to start with the data. They want to dig in, because we often have piles of data. But there's a common mistake we make when we do that.I was working with a CEO. She came to me to prepare for her annual companywide meeting and she had 45 slides of data for a 45-minute presentation. A recipe for a boring, unmemorable talk. And this is what most people do, they come armed with all of this data and they try to sort their way through without a big picture and then they lose their way. We actually put the data aside and I asked her, "What's the problem you're trying to solve? What do you want people to think and feel different and what do you want people to do different at the end of this?" That is where you start with data and storytelling. You come up with this framework to guide the way through both the story and the data. In her case, she wants her company to be able to break into new markets, to remain competitive. She ended up telling a story about her daughter, who's a gymnast who's competing for a scholarship, and she had to learn new routines with increasing difficulty to be competitive.This is one of your choices. Do you tell a story about the data itself or do you tell a parallel story, where you pull out points from the story to reinforce the data? As you begin this ballad, this melody and harmony of data and storytelling come together in a way that will stay with you long after.Briana was a college adviser. And she was asked to present to her university leadership when she realized that a large population of their students with autism were not graduating. She came to me because her leaders kept saying, "Present the data, focus on the data," but she felt like university officials already had the data. She was trying to figure out how to help them connect with it. So we worked together to help her tell the story about Michelle.Michelle was a straight-A student in high school who had these dreams of going to university. Michelle was also a student with autism who was terrified about how she would be able to navigate the changes of university. Her worst fears came true on her first phone call with her adviser, when he asked her questions like, "Where do you see yourself in five years?" and "What are your career aspirations?" Questions that are hard for anybody. But for a person with autism to have to respond to verbally? Paralyzing. She got off the phone, was ready to drop out, until her parents sat down with her and helped her write an email to her adviser. She told him that she was a student with autism, which was really hard for her to share because she felt like there was a stigma associated just by sharing that. She told him that she preferred to communicate in writing, if he could send her questions in advance, she would be able to send replies back to him before they got on the phone to have a different conversation. He followed her lead and within a few weeks, they found all of these things they have in common, like a love for Japanese anime. After three semesters, Michelle is a straight-A student thriving in the university.At this point, Briana starts to share some of the data that less than 20 percent of the students with autism are graduating. And it's not because they can't handle the coursework. It's because they can't figure out how to navigate the university, the very thing an adviser is supposed to be able to help you do. That over the course of a lifetime the earning potential of someone with a college degree over a high school degree is a million dollars. Which is a big amount. But for a person with autism that wants to be able to live independent from their family it's life changing.She closed with, "We say our whole passion and purpose is to help people be their best, to help them be successful. But we're hardly giving our best service by applying this one-sizefits-all approach and just letting people fall through the cracks. We can and we should do better. There are more Michelles out there, and I know because Michelle is my daughter." And in that moment, the jaws in the room went — And someone even wiped away tears, because she had done it, she had connected them to information differently, she helped them see something they couldn't unsee. Could she have done that with data alone? Maybe, but the things is, they already had the data. They didn't have a reason not to overlook the data this time.That is the power of storytelling and data. That together, they come together in this way to help build ideas, to help you see things you can't unsee. To help communicate what's valued and to help tap into that emotional way that we all decide. As you all move forward, shaping the passion and purpose of others as leaders, don't just use data. Use stories. And don't wait for the perfect story. Take your story and make it perfect.Thank you.(Applause) Princess Savitri of the Madra Kingdom was as benevolent, brilliant, and bright as the Sun God she was named for. Her grace was known throughout the land, and many powerful princes and wealthy merchants flocked to her family’s palace to seek her hand in marriage. But upon witnessing her blinding splendor in person, the men lost their nerve. Unimpressed with these suitors, the princess determined to find a husband herself.Mounting her golden chariot, she travelled through rolling deserts, glittering cities and snow-capped mountains— rejecting many men along the way. Eventually, Savitri ventured deep into the jungle, where she met a young man chopping wood. His name was Satyavan, and like her, he loved the tranquil forest— but the princess saw he was not at peace.After talking for hours, Satyavan told her of his plight. His parents had once been wealthy rulers, until his father was blinded and overthrown in a violent coup. Now Satyavan worked tirelessly to support their meager new life. His determination and devotion moved the princess. As they gazed into each other’s eyes, she knew she’d finally found an equal.Savitri rushed home to tell her father the good news, only to find him conversing with Narada a traveling sage and Savi wisest messenger of the Gods. At first her father was thrilled to learn of tri Satyavan, but Narada revealed a tragic prophecy: her betrothed had only a year and to live.Savitri’s blood ran cold. She’d waited so long to find her partner— was Sat she already doomed to lose him? The princess would not accept these terms. yav She swore before Narada, her family, and Savitr himself that she would never an marry another. Satyavan was her one true love, and their fates were entwined forever.Moved by her powerful words, the sage told the princess to follow an ancient spiritual regimen. With regular prayer, periods of fasting, and preparation of special herbs and plants, she might be able to prolong Satyavan’s life.After a simple wedding, the couple returned to the jungle to live in keeping with the sage’s instructions. This modest existence was a far cry from her lavish upbringing, but they were happy in each other’s company. A year passed, and the fated day arrived. On their first anniversary, the sun grew horribly hot, and Satyavan’s brow began to burn, Savitri barely had time to drag him into the shade, before he grew still and cold. Through her tears, the princess saw an immense figure on the horizon. This was Yamraj, the God of Death, come to escort Satyavan’s soul to the afterlife. But Savitri was not giving up yet.She followed the god for hours in the beating sun. Yamraj thundered at the princess to leave him in peace. But even as her feet bled and throat burned, Savitri would not turn back. Eventually, Yamraj paused. He would grant her one wish as reward for her persistence, but she couldn’t ask for her husband’s life. Without hesitating, Savitri asked the God to restore her father in-law’s sight. The wish was granted, and Yamraj rode on. But still Savitri’s footsteps echoed behind him. Exasperated, the God granted her a second wish. This time, she asked for Satyavan’s kingdom to be restored. Again the wish was granted, and Yamraj began his descent into his subterranean kingdom. But when he glanced back, he was astounded to see the bedraggled princess stumbling along. He’d never seen such devotion to the dead, and he honored her dedication with one final wish.Savitri wished to be the mother of many children. The God agreed, and waved to dismiss her. But the princess only repeated the vow she’d made one year earlier: her fate was forever entwined with Satyavan. How could she bear many children, if Yamraj would not return her husband? Hearing this clever question the god relented, knowing he’d been beaten. With Yamraj’s blessing and respect, Satyavan was returned to Savitri, and the two walked back to the land of the living, united in a love that not even death could destroy. Non e Ho If you're in charge of a major metropolitan city, it's almost a must these days to w be sustainable. Us city dwellers pride ourselves on living in places that are car taking action on climate change and achieving net zero.But what if you're Don bon Iveson? You're the mayor of oil and gas town Edmonton, in northern Alberta, capt Canada. Or across the Atlantic, Holly Mumby-Croft, UK member of parliament ure for Scunthorpe, home to one of the last steel plants of Britain. Or much smaller, net you're Dave Smiglewski. You're the mayor of the little city of Granite Falls, wor Minnesota, with a large-scale ethanol production facility nearby. All these places, ks no matter how far apart and how different in size, have something big in coul common: millions of tons of greenhouse gas emissions linked to significant local d employment. And we're going to have to find a way to maintain the critical help economic and social functions of these towns if we're to have any hope of cur combating climate change. Not an easy feat, if you think that we can't really put b a solar panel on a gas processing facility or a steel mill.Fortunately, these places clim have another interesting thing in common, which might offer some hope to these ate local officials. The main sources of pollution in their areas are in close proximity cha to rock formations with the ability to trap carbon dioxide, the greenhouse gas we nge often call CO2. And this puts into reach a potential solution to both their problems: pollution and employment. It's called "carbon capture and storage." It's the process whereby we capture the CO2, which results from burning fossil fuels, before it's emitted into the atmosphere and instead bury it underground. Effectively, we take part of what we've extracted from the earth — the carbon — back to where it came from.Now, this is not a new idea. People have been experimenting with this technology for decades. Today, however, there are very few operational carbon capture facilities in the world, capturing about 14 million tons of CO2 equivalent per year. And while that may sound like a big number, it's less than .1 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions.The International Energy Agency predicts that we need to capture between four and seven gigatons — that's four to seven billion metric tons — of CO2 per year by 2040 to stay at or below two degrees Celsius warming. And that's a more than 100 to 200 times increase in today's carbon capture capacity.To get us there will definitely require a price on greenhouse gas pollution. There is a cost, and it needs to be settled. And if we're not smart about it, the price could be very high. Should we then solely rely on the future improvements in the fundamental technology? No. There is another way. And it's the need for well-thought-through rollouts of what might be called CO2 networks.In BCG, I lead a team of consultants, analysts and data scientists whose focus is on advancing carbon capture utilization and storage. By our estimates, if we want to hit the IEA forecast, we need at least 110 billion dollars per year for the next 20 years to build out the required carbon capture and storage infrastructure. And there's only one way to bring down this essential but hefty price tag, which is to share the cost through networks. Consider it the waste disposal service for CO2. Our research suggests that policymakers and companies can learn a lot by looking at a map — lots of maps, actually, both the ones that you and I look at on our smartphones as well as the less common ones that show what lies below the surface in terms of depleted oil and gas fields and saline aquifers with the ability to trap CO2 underground. And by looking at these maps, we can look for the optimal distances between both the sources of emissions, like Scunthorpe's steel plant, and the sinks, like the saline aquifers of Alberta.We had a first go, and it yields interesting results. By building up a detailed database of emitters as well as potential sinks, we found up to 200 clusters that have the ability to be scaled up to low-cost carbon networks. And they can capture more than one gigaton of emissions, a big step to the four to seven gigatons that we need. And when we dig a little deeper, we find that optimization of distances between sinks and sources matters. It matters a lot in terms of the cost. Network effects, which is the mechanism whereby the benefits of a system to a user increases with the amount of others' use of it, can reduce the capture and storage cost of many emitters by up a third, to below 100 dollars per ton of CO2 captured, based on current costs of technology. And while that is still a substantial cost, it starts to get in the range of carbon taxes and market mechanisms that governments of Western economies are starting to think about or have already put in place. And we would not be able to achieve it without collaboration and sharing of infrastructure between neighboring emitters.Let us walk through some of the cities I mentioned. In assessing areas to build CO2 networks, we look for three different things. Firstly, proximity to storage. Secondly, a cluster of at least a few sources with high amounts of CO2 in their flue gas; the more CO2 in the exhaust, the cheaper it is to capture. And thirdly, an ability to scale up the network and lower the cost quickly with few emitters.Edmonton and its surrounding areas provide a good example of this idea at work. Suitable underground rock layers that can trap CO2 are abundant, well exceeding what is needed, and it also meets the second and third criteria in that it has a good combination of both high- and low- concentration CO2 streams associated with different industrial processes. And it can scale up to low cost quickly. In one of the clusters, we find the number of emitters with very low capture and storage cost in the range of 40 to 50 dollars per ton, but they only represent 1.2 megatons per year. The total cluster, however, can scale up to 12 megatons — up to 10 times its original size. But those first megatons of emissions played a crucial role in scaling up the network and reducing the cost and risk for others down the line. That's your network effect in action.And it's not just Edmonton. If we take Scunthorpe in Lincolnshire in the UK, we see similar dynamics and potential. The North Sea offers sufficient storage, and while storing CO2 offshore is more expensive than onshore, there's the potential to reduce this cost by reusing and repurposing existing oil and gas infrastructure. If the steel mill standalone would have to capture and store its CO2, it would prove very costly. But it can reduce this cost by sharing the infrastructure with refining and chemical emitters en route to the North Sea. Many of them have cheaper capture cost with the ability to improve the overall economics and kick-start a network that has the ability to scale up to 28 megatons. Two examples in two different countries with 14 megatons of potential — already double versus what we have today.And this network effect applies anywhere and is actually not uncommon when it comes to building out infrastructure. In fact, CO2 networks could very much follow the principles of the past in terms of how our energy and utility infrastructure was developed around us, whether it's water, gas, electricity, local supply chains — all these networks apply local economies of scale and were built up over time with favorable, marginal cost of adding new connections. The big difference here is we're reversing the flow. And these networks have the potential to enable future innovation of using CO2 in chemical processes to make, for example, building materials instead of burying the CO2 underground.Our analysis is a pure economic one. It does not account for political and local geographical barriers, but creating a favorable regulatory environment and removing these barriers will be critical. Take these two neighboring states in the US, for example: North Dakota, with ample, cheap storage and existing CO2 pipelines, and the state has put in place tax incentives and financial assistance to use it. Go next door to Minnesota: no storage within several hundred miles, but home to 18 large-scale ethanol production facilities, including the one in Granite Falls, all of which create a highly concentrated stream of CO2 emissions. Can the blue and the red state work together to add 40 megatons to our carbon capture tally?We have no more than 20 years to bend the curve and combat climate change — potentially less. The gas networks in my two home countries of the Netherlands and the UK were built in similar time frames after the Second World War — massive undertakings in infrastructure buildup and at a time of similar high national debt. It's time to build another network, one for CO2. It does not need to last forever. It can be there just for the transition away from fossil fuels. But we need it now to preserve local manufacturing jobs and our communities and provide a hope for a better and more sustainable future.It is critical that governments, both local and national, as well as companies, assess the potential for carbon capture at a local level, start to capture the cheapest sources of CO2 and build up the network from there. Only in that way can local communities like the ones in Edmonton, Granite Falls, Scunthorpe and beyond thrive both economically and sustainably.Thank you. The In the spring of 1947, six Scandinavian explorers noticed a strange phenomenon se while crossing the Pacific Ocean. Somehow, small squid known to live deep squi beneath the waves kept appearing on the roof of their boat. The crew was ds mystified— until they saw the squids soaring above the sea for roughly 50 can meters.On land, people could barely believe the explorers. It seemed impossible fly... that sea creatures without wings or bones could fly at all, let alone travel half the no, length of a football field. But over the next several decades, more reports began reall to surface. Sailors described airborne squid keeping pace with motor boats. y Researchers reported captive squid escaping their tanks overnight. And as cameras became widespread, seafarers finally began capturing proof of these high-flying cephalopods. But how and why do these marine creatures take to the sky?While only a few squid species have been recorded taking flight, most squid are alike in the way they traverse the ocean. The outside of a squid’s body is a massive tube of muscle called the mantle. Water enters that tube through small openings around the squid’s head. Then, muscles clamp these openings shut, and the squid forcefully pumps the water through the base of their body. In practice, this makes the mantle a miniature jetpack, propelling squid through the water at 10 kilometers per hour. This process is also how squid breathe. Squid gills rest inside the mantle, and siphon oxygen from the water being pushed past them. With gills full of air and a mantle full of water, squid can outpace predators and pursue their prey. Or, in the case of some species, they can smash through the ocean’s surface, and attempt an epic flight.Without the resistance of water, a squid’s acceleration is the same as a car going from zero to 100 kilometers per hour in just over a second. At speeds of 40 kilometers per hour, squid quickly generate aerodynamic lift. But to stay in the air they’ll need something like wings. Fortunately, our soaring cephalopod has a plan. Squid tentacles are "muscular hydrostats," meaning the tissue can be held firm by muscle tension. Splaying its tentacles in a rigid formation, the squid transforms them into flexible wing-like structures that stabilise its flight. At the opposite end of its body, two fins typically used for gentle swimming find new purpose as a second set of wings. And by folding these fins down, a squid can streamline itself and dip back into the ocean.There have been too few observations to establish what a squid’s typical flight trajectory looks like. Based on their flying speed, a 10 centimeter squid could hypothetically launch itself six meters above the water. But from what scientists have seen, flying squid tend to glide low, keeping close to the surface. This trajectory allows squid to cover the most horizontal distance possible over a typical several second flight. It also makes it easy to dive back into the water for more fuel— or to make a quick escape from predatory birds.But why do squids fly at all? Leading theories suggest that flight is an escape behaviour, as flying squid generally seem to be fleeing a nearby predator or ship. Other researchers think their flight may be an energy-saving migration strategy, because it takes less energy to move quickly through the air than through water. However, it’s also possible that learning to fly may be a vital part of surviving adolescence. Young, smaller squid can potentially fly faster and farther than their larger relatives. And since adult squid tend to cannibalize juveniles, soaring above the surf can help ensure these young squid will live to fly another day. Julia Gillard: Ngozi, 10 years ago when I became prime minister of Australia, I assumed that at the start, there would be a strong reaction to me being the first woman, but it would abide over time and then I would be treated the same as every other Prime Minister had been. I was so wrong. That didn't happen. The longer I governed, the more visible the sexism became. I don't want any other woman to be blindsided like that. That's why I'm so excited about working with you to help women get ready to lead in what is still a sexist world.Ngozi OkonjoIweala: I share that sense of excitement. After I was finance minister of Nigeria, I was overwhelmed by the number of women who wanted me to be their mentor. It is terrific that aspiring, young women are keen to learn from those who have gone before, but there are still too few female role models, especially women of color. Now as a result of the work we have done together, I can offer everyone clear, standout lessons that are based not just on my own experience, but on the global research on women and leadership and the candid insights of leading women.JG: One of the things to share is that there's joy in being a leader — in having the opportunity to put your values into action. Emphasizing the positive makes a real difference to the power of role modeling. If we only focus on the sexist and negative experiences, women may decide that being a leader sounds so grim they don't want to do it. On the other hand, if we pretend it's all rosy and easy, women and girls can be put off because they decide leadership is only for superwomen who never have any problems. We all have to get the balance right, but Ngozi, it's impossible to talk about role models right now without asking you: how does it make you feel to see Kamala Harris elected as vice president?NOI: I'm delighted. It's important to the aspiration of girls and women that they see role models they can relate to. Vice President-elect Harris is exactly that kind of role model, particularly for girls and women of color. And 6 every woman who steps forward makes more space for the women who come ess next.JG: Of course both of us know from our own experiences that even when enti women get to the top, unfortunately, too much time and attention will be spent on al what they look like rather than what they do and say. Ngozi, for women, is it still less all about the hair?NOI: Certainly, Julia. I laughed when Hillary Clinton said she ons envied my dress style, and particularly my signature scarf, so I don't need to for worry about my hair. Like many of our women leaders, I've effectively adopted a wo uniform. It's a colorful one, it's African, it's me. I have developed my own style men that I wear every day and I don't vary from it. That has helped protect me from lead endless discussion of my appearance. It's helped me to get people to listen to ers my words, not look at my clothes.JG: Hillary told us she lost the equivalent of 24 full days of campaign time in the 2016 election getting her hair and makeup done every day. But actually, contemporary problems for women leaders go far deeper than anything to do with looks. I'd better warn you now, I'm about to use a word many people would find rude. My favorite funny moment in our travels was discussing "resting bitch face" with Prime Minister Erna Solberg of Norway. The global research shows that if a man comes across as strong, ambitious, even self-seeking, that's fine, but if a woman does it, then the reactions against her can be as visceral as revulsion or contempt. They're pretty mind-bogglingly strong words, aren't they?NOI: They certainly are, and women leaders talk about it intuitively, understanding that to be viewed as acceptable as a leader, they have to stay balanced on a tightrope between strength and empathy. If they come across as too tough, they're viewed as hard and unlikeable. But if they come across as too soft, they seem to be lacking the backbone needed to lead.JG: The problem is we still all have sexist stereotypes whirring in the back of our brains. I was portrayed as out of touch because I don't have children. I was even compared to a barren cow in the bush, destined to be killed for hamburger mince.NOI: That's horrible that you faced that stereotype. While I was worried that people would think I couldn't do my job when my family was young, I enjoyed talking to New Zealand's Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern about her experience as the second woman ever to have a child while being a national leader. I was very taken by her saying she doesn't think she gets the work-life balance right, in the sense that she doesn't like the word "balance," and there's always guilt. She just makes it work.JG: Ngozi, where are men in this?NOI: Hopefully, manning up. Men can more equitably share domestic and care work. They can point out sexism when they see it. They can make space for women and mentor and sponsor them. Given that men disproportionately still have the power, we won't see change unless they work with us to create a world that will be better for men and women.JG: Let's talk about the "glass cliff" phenomenon. If a business or an organization is going well, then they're likely to appoint a new leader who looks a lot like the old one — that is, a man. But if they are in difficulties, they decide it's time to get someone quite different, and often reach for a woman. To take one example, Christine Lagarde became the first woman to lead the International Monetary Fund when it was in crisis after its former head was arrested for sexual assault. Ngozi, while not as dramatic as that, you know a bit about glass cliffs too.NOI: I certainly do. I remember clearly being chosen, as a young woman, to lead a very problematic World Bank project in Rwanda. No one else wanted to lead it, lest they fail. So there was this attitude of "if she pulls it off, it's OK. If she fails, then, well, she's just a young African woman whose career doesn't matter that much." From that experience, I learned things about myself and leadership, and the biggest lesson we can share is this: if you have a sense of purpose that drives you, then aim high — become a leader. And make room as you go. Former US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright is fond of saying that there's a special place in hell for women who don't support women. In this world, we need to be there for each other.JG: There's a bit of good news and bad news here. Certainly the research shows that the stereotype about the businesswoman who makes it to the top and then stops other women coming through isn't borne out by the facts. The constraint seems to be that organizations think once they've got a woman or two, they don't need to worry about gender anymore. But we do have to be frank — women do get pitted against other women for the limited number of seats at the table. We have to be wary of having our solidarity with each other eroded by these politics of scarcity. Instead, we should work together to change the rules that keep us at the margins.NOI: So to summarize, our standout lessons are ... Number one, there's no right way to be a woman leader. Be true to yourself.JG: Number two, we know that women leaders face sexism and stereotyping, so sit down with your mentors, sponsors, best supporters and friends and war-game. How are you going to deal with the gendered moments, with being judged on your appearance, with being assumed to be a bit of a bitch or with your family choices questioned? Forewarned is forearmed.NOI: Number three, let everyone you know talking about gender stereotypes and debunking them: these false assumptions can't survive being held up to the light of day.JG: Number four, there are structural barriers too. Don't wait until you need help balancing work and family life or to be fairly evaluated for promotion. Be a supporter of systems and changes that aid gender equality even if you don't personally need them immediately.NOI: Number five, don't take a backwards step. Don't shy away from taking up space in the world. Don't assume you're too junior or people are too busy. Reach out, network.JG: That's great advice, and leads us to the most important lesson of all — go for it.NOI: Yes, go for it.JG: (Laughs) Thank you.NOI: Thank you. My father used to call me Jamila "Gabar Nasiib Nasiib Badan," which means Ho Jamila "The Lucky, Lucky Girl." And I have been very fortunate in my life. My w AI family were originally nomads. And when it rained the night I was born, they can stopped in a tiny village that looked a bit like this, where we lived in the next 11 help years until drought and a war with Ethiopia forced us to move to Somali's capital, shat Mogadishu.When I was 18, my father realized Somalia was headed for a civil ter war and we are all at risk of being killed. He did his best to get me and my 13 barr brothers and sisters out of the country. The family was scattered to the wind. I iers was lucky. I ended up on my own as a displaced person in Kenya, and I was to fortunate to come to Australia thanks to a backpacker who I met there.I was equ incredibly grateful when the Australian government gave me unemployment ality benefits while I learned English, but I wanted to find work as soon as I could. I learned about a Japanese restaurant that was hiring, and I thought, "What do I have to lose?" Mami, the woman who ran front of house, figured my poor English might be a problem, so she sent me to the kitchen to meet her husband, Yoshi. Now, Yoshi didn't speak much English either, but we managed to communicate with one another. He hired me as a dishwasher and trained me as a kitchen hand. Now, that couple's kindness set me on a path where hard work and persistence led me to my graduation as a software developer and went on to become a global executive with IBM and later, chief information officer of Qantas Airways.Now I want artificial intelligence to do at a massive scale what that couple did for me: give disadvantaged people tools to find work, give them the skills to be great at their jobs, get them to do their jobs safely, to give them a break. You hear stories about how artificial intelligence is going to take away jobs and automate everything. And in some cases that might be true, but I can tell you in the real world right now, AI is making amazing things possible for organizations and for people who otherwise would have been left behind. Language, education and location are no longer the barriers they once were.And to help break down those barriers is one of the reasons I founded my company. Much of our work is in global food supply chains, especially in the meat industry. We use computer vision-based AI to create transparency for consumers and to reward producers who operate ethically and sustainably.But AI can do much more than that. For example, it can notice unsafe behaviors, like if someone is not wearing their personal protective gear correctly, or someone not following the hygiene procedures, or if someone needs help on how to carry out a specific task because they're not following the recipe correctly. We can make sure people are socially distancing and can provide contact tracing if needed.We then deliver individualized training to that person's preferred language both in written and audio formats. Now, ability to read or write or to speak the local language are no longer the obstacles they once were. Many of the employees in the food industry are often migrants, refugees or people from disadvantaged backgrounds who might not be able to speak the local language and often might not be able to read or write well. In fact, one of our customers has 49 languages spoken in some of their facilities, with English long way down the list. When we can see opportunities for improvements and then deliver training with that person's preferred language, it makes huge difference to the organization and to its people. And that is only the beginning.When I was very young — about five or six years old, living in that tiny village — one of my jobs was to carry buckets of water from the well to the huts. And I remember putting the buckets down in every 20 meters or so and how the handles digged into my hands. They were so heavy, and I was so scrawny because we didn't have enough to eat. Even though that experience taught me resilience, it's not something I want any other child to go through.I want to live in a world where people are not limited by local language, by geography, by lack of access to knowledge and training, where everyone is safe at work, when nobody's excluded because they cannot read or write, where everyone can fulfill their potential.Now AI can deliver this world.Thank you. As dawn breaks in the Babylonian city of Sippar, Beltani receives an urgent visit from her brother. It’s 1762 B.C.E., during the reign of King Hammurabi.Beltani is a naditu— a priestess and businesswoman, promised to the temple at birth. At puberty, she changed her name and gained her elevated naditu status in a ceremony where a priest examined the entrails of a sacrificed animal for omens. The naditu are an esteemed group drawn from Babylonia’s most affluent families. Though the rules are different for naditu in each city, in Sippar they are celibate and never marry. They live inside the gagum, a walled area inside the temple complex, but are free to come and go, and receive visitors.Beltani owns barley fields and a tavern. Her brother manages these businesses while she fulfils her duties as a priestess. This morning, he makes a troubling accusation: her tavern keeper has been diluting wine with water. If true, this means she’s been undermining the business Beltani relies on to sustain her in old age. But the consequences would be even higher for the tavern keeper: the punishment of diluting wine is death by drowning.The temple court is meeting this afternoon. A Beltani has just a few short hours to find out whether there’s any truth to these day allegations. But she can’t go to the tavern to investigate. Taverns are off limits for in priestesses, even priestesses who own them. She could be burned to death for the entering. So she sends for the tavern keeper to meet her at the temple of life Shamash, the patron god of Sippar.The temple is a stepped pyramid called a of ziggurat, in the heart of the city and visible from twenty miles away. It an symbolically connects heaven and earth and is viewed as the literal home of the anci god Shamash, who gave humanity the code of laws and is the judge of the ent Babylonian pantheon. Beltani leaves an offering of bread and sesame oil in a Bab private room. She never enters the inner chamber of the temple where the god ylon lives, a place so holy only high priestesses and kings visit.Outside, worshippers ian play music and leave gifts, which are later collected and used to feed temple busi workers, including the naditu. The tavern keeper is waiting with grim news. She nes says Beltani’s brother has been altering the weights used to measure payments s to cheat customers. When the tavern keeper confronted him, he falsely accused mo her of watering down the wine. If true, Beltani’s brother is the dishonest one— gul and altering weights is another crime punishable by death.Beltani is running out of time to get to the bottom of this. Though she can’t go to the tavern, she can check on the barley fields her brother manages to see if he’s been honest there. In the granary, she sees much more grain than he reported to her. He’s been cheating her out of her share.Like all naditu in Sippar, Beltani inherited the same portion of her father’s property as her brother. These were rare circumstances for women in a time and place where property passed through men. Still, their families didn’t always honor their rights. Although naditu traditionally went into business with male relatives, the law stated they can choose someone else if their brothers or uncles weren’t up to the task.With the evidence she needs, she hurries to court. A judge presides over the temple court along with two naditu— the overseer of the gagum and a scribe. Beltani asks to remove her brother as her business manager, citing the granary as evidence that he is mismanaging her properties. The judge grants her request. The scribe records the new contract in cuneiform into a wet clay tablet, and the matter is settled. She's protected her income and spared her brother’s life by withholding the true extent of his crimes.Perhaps it is time to adopt a younger priestess: someone to take care of her in old age and inherit her property, who might do a better job of helping with her business. I don't know about you, but when our family got the stay-at-home order in March of 2020, I came out of the gates pretty darn hot. "Embrace not being so busy," I wrote. "Take this time at home to get into a new happiness habit." That seems hilarious to me now. My pre-coronavirus routines fell apart hard and fast. Some days I would realize at dinnertime that not only had I not showered or gotten dressed that day, but I hadn't even brushed my teeth. Even though I have coached people for a very long time in an effective, science-based method of habit formation, I struggled. Truth be told, for the first few months of the The pandemic, I more or less refused to follow my own best advice.This is because I 1love to set ambitious goals. Getting into a good little habit is just so much less min exciting to me than embracing a big, juicy, audacious goal.Take exercise, for ute example. When the coronavirus hit, I optimistically embraced the idea that I secr could get back into running outside. I picked a half-marathon to train for and et spent a week or so meticulously devising a very detailed training plan. But then I to actually only stuck to my ambitious training schedule for a few weeks. All that for planning and preparation led only to a spectacular failure to exercise. I skipped min my training runs, despite feeling like the importance of exercise and the good ga health that it brings has never been more bracingly clear.The truth is that our new ability to follow through on our best intentions, to get into a new habit like habi exercise or to change our behavior in any way, really, doesn't actually depend on t the reasons we might do it or on the depth of our convictions that we should do so. It doesn't depend on our understanding of the benefits of our particular behavior or even on the strength of our willpower. It depends on our willingness to be bad at our desired behavior. And I hate being bad at stuff. I am a go-big-orgo-home kind of a gal. I like being good at things, and I quit exercising because I wasn't willing to be bad at it.Here's why we need to be willing to be bad: being good requires that our effort and our motivation be in proportion to each other. The harder something is for us to do, the more motivation we need to do that thing. And you might have noticed, but motivation isn't something that we can always muster on command. Whether we like it or not, motivation comes and motivation goes. When motivation wanes, plenty of research shows that we human beings tend to follow the law of the least effort, meaning we just do the easiest thing. New behaviors tend to require a lot of effort, because change is really hard. To establish an exercise routine, I needed to let myself be kind of half-assed about it. I needed to stop trying to be an actual athlete.I started exercising again by running for only one minute at a time. Every morning, after I brushed my teeth, I'd change out of my pajamas and walk out the door, my only goal, to run for one full minute. These days, usually I actually do run for 15 or 20 minutes, but on the days that I'm totally lacking in motivation or I just feel like I have no time, I still do that one minute. And this minimal effort always turns out to be way better than if I did nothing.Maybe you relate. Maybe you've also failed in one of your attempts to change yourself for the better. Perhaps you want to use less plastic or meditate more or be a better anti-racist. Maybe you want to write a book or eat more leafy greens. I have great news for you. You can do and be those things, starting right now. The only requirement is that you stop trying to be so good. You'll need to abandon your grand plans, at least temporarily. You'll need to consider doing something so minuscule that it would be better than not doing anything at all.So right now, ask yourself: How you can strip that thing that you have been meaning to do into something so easy you could do it every day with barely a thought? It might be eating one piece of lettuce on your sandwich at lunch or going for a one-minute walk outside. Don't worry — you'll get to do more. This better-than-nothing behavior is not your ultimate goal. But for now, what could you do that is ridiculous easy that you can do even when nothing is going as planned? Even though you ultimately might want to do more and be more, remember that we humans are often too tired and too stressed and too distracted to do the things that we really do intend to do and to be the people that we most intend to be. On those days, our wildly ambitious behaviors really are better than nothing. A one-minute meditation is relaxing and restful. A single leaf of romaine lettuce happens to have a half a gram of fiber and loads of nutrients. A one-minute walk gets us outside and moving around, which our bodies really need.So try doing one better-than- nothing behavior. See how it goes. The goal, remember, is repetition, not high achievement. So let yourself be mediocre at whatever you're trying to do, but be mediocre every day. Take only one step, but take that step every day.If your better-than-nothing habit doesn't actually seem better than doing nothing, consider that you're getting started at something and that initiating a behavior is often the hardest part. By getting started, we're establishing the neural pathway in our brain for a new habit, which makes it much more likely that we'll succeed with something more ambitious down the line.Why is this? Well, it's because once we hard wire a habit into our brains, we can do it without thinking, and therefore without needing much willpower or effort. A better-than-nothing habit turns out to be incredibly easy to repeat again and again until it's on autopilot. This is because we can do it even if we aren't motivated, even if we're tired, even if we have no time whatsoever. And once we start acting on autopilot, that's the golden moment that our habit can begin to expand organically.After only a few days of running for just one minute, I started feeling a real desire to keep on running, not because I felt like I should be exercising more, or because I felt like I needed to impress my neighbors or something, but because it felt more natural to keep running than it felt to stop.Now, I of all people know that it can be incredibly tempting, especially for the overachievers among us — you know who you are — to encourage ourselves to do more than our designated better-thannothing habit. So I must warn you: the moment in which you are no longer willing to do something unambitious is the moment in which you are risking everything. It's the moment you end up checking your phone instead of whatever it is that you intended to do. It's the moment in which you stay on the couch bingewatching TikTok videos or Netflix. The moment you think you "should" do more is the moment you introduce difficulty and force and negotiation with yourself. It's the moment you eliminate the possibility that it will be easy and even enjoyable. So that's also the moment that will require a lot more motivation, and if the motivation isn't there, failure will be.Fortunately, the whole idea behind the better-than-nothing habit is that it doesn't depend on motivation, which we may or may not muster. It's not reliant on having a lot of energy. You do not have to be good at this. You need only to be willing to do something that is wildly unambitious, to do something that is just a smidge better than nothing. But again, don't do more if you feel any form of resistance.I'm happy to report that after months of struggle, I am now a runner. I became one simply by allowing myself to be bad at it. You definitely could not call me an athlete; there are no half-marathons in my future. But I am consistent. To paraphrase the Dalai Lama, the goal is not to be better than other people but rather to be better than our previous selves. And that, I definitely am.When we abandon our grand plans and great ambitions in favor of taking that first step, we shift. And paradoxically, it's only in that tiny shift that our grand plans and great ambitions are truly born.Thank you. What would make me quit my job during the pandemic? The short answer: injustice in America. But since I have a little time, let me give you the long version. In May 2020, protests broke out across the United States. George Floyd, a Minnesota man, was killed by a couple of police officers on camera and hundreds of thousands of Americans had had enough. Like so many others, I watched the protests on the news. I watched as the crowd moved from downtown Atlanta to Buckhead, where I live. The protesters were right outside of my house, so in true millennial fashion, I took out my phone so I could record it and post it to Twitter.After logging the events, I called my parents, and as I was talking to my snook, which is what I call my mom, I began to get a little worried. The energy of the crowd was growing and snook told me, "Don't worry, baby, when people feel that their voices aren't heard, they have to make it felt." Hm. They have to make it felt. That statement hit me hard because, why weren't people being heard? I mean, if we're all watching the same thing, then why aren't we all upset? And how could I help make a difference? No, better yet, how could I make it felt? That was the moment I began to think about opting out ... opting out of a career I dreamed of my entire life.I've been playing in the WNBA since 2009, most recently as a guard for the Atlanta Dream. Basketball has been one of the biggest parts of my life, and yet I decided to give it up, trying to focus on changing the world for the better. I wanted to make it felt.Some people thought I was crazy, but honestly, most people got it, and even though I was filled with fear, I took that leap of faith and did it anyway. I opted out not knowing how I was going to pay my bills. I opted out not knowing if I would ever be a professional WNBA player again. I opted out of my comfort zone, and in doing so, I truly opted in. I gained a completely different perspective and the confidence that comes with turning moments into momentum.The next day I threw a Juneteenth event, and Juneteenth is a day to commemorate the official Ho end of slavery. At the event, people were telling me they heard my story, they w to were coming up to me like, "Yo, you opted out! That's so dope!" But then they turn began to vent to me, telling me about uncles pulled over for no reason, cousins mo killed by the police. They wanted me to know their stories so I could represent men their voices, and in that moment, I felt so connected with helping them. They felt ts that I was the person that could make their stories felt, and honestly, I was into committed to doing whatever I needed to make that happen. I don't know how to mo cure racism, fix police brutality or any of the other problems plaguing America. men No one person can do that. But we all can do what we can to make it felt.Making tum it felt for me is an action. It's not just protesting and raising your voice, but also doing something to show your intention. I opted out and now you feel me. Honestly, that was a big move for me, but now that I've done it, it feels like it was almost inevitable. And while making it felt can have a negative connotation of violence and trouble, I wanted to show that it could also have a really positive form.Playing in the WNBA has afforded me a platform, and with that platform, I want to create positive change. So big picture, I want to level the playing field so that everyone has access to the same opportunities, regardless of race. To do this I know I need to increase exposure to the young Black and brown youth, showing them explosive fields like tech and creating ways for them to develop those skills so they can seize the opportunities. We're creating a workshop and partnering with organizations already doing the work, taking small steps now that I know will have a big impact in the future.A lot of times we underestimate what we can do — the effect we can have. Imagine if we all started to think about "How can I make it felt?" If we all took that leap of faith to stand for what we believe is right, regardless of the very real fear embedded in that decision, I think we would then start to fulfill the title of the United States of America instead of the divided states that we're seeing right now.I know from basketball that all it takes is a single moment, a second, to change everything. So let's choose to turn our moments into momentum. I'm making it felt, are you?Thank you. Imagine you're on a shopping trip. You've been looking for a luxury-line dinnerware set to add to your kitchen collection. As it turns out, your local department store has announced a sale on the very set you've been looking for, so you rush to the store to find a 24-piece set on sale. Eight dinner plates, all in good condition; eight soup and salad bowls, all in good condition; and eight dessert plates, all in good condition. Now, consider for a moment how much you would be willing to pay for this dinnerware set.Now imagine an alternate The scenario. Not having seen this 24-piece luxury set, you rush to the store to find a cou 40-piece dinnerware set on sale. Eight dinner plates, all in good condition; eight nter soup and salad bowls, all in good condition; eight dessert plates, all in good intu condition; eight cups, two of them are broken; eight saucers, seven of them are itive broken. Now consider for a moment how much you would be willing to pay for way this 40-piece dinnerware set.This is the premise of a clever experiment by to Christopher Hsee from the University of Chicago. It's also the question that I've be asked hundreds of students in my classroom. What were their responses? On mor average, when afforded the 24-piece luxury set, they were willing to spend 390 e pounds for the set. When afforded the 40-piece dinnerware set, on average, per they were willing to spend a whopping 192 pounds for this dinnerware set. sua Strictly speaking, these are an irrational set of numbers. You'll notice the 40sive piece dinnerware set includes all elements you would get in the 24-piece set, plus six cups and one saucer. And not only are you not willing to spend what you will for the 24-piece set, you're only willing to spend roughly half of what you will for that 24-piece set.What you're witnessing here is what's referred to as the dilution effect. The broken items, if you will, dilute our overall perceived value of that entire set. Turns out this cognitive quirk at the checkout counter has important implications for our ability to be heard and listened to when we speak up. Whether you are speaking up against a failing strategy, speaking against the grain of a shared opinion among friends or speaking truth to power, this takes courage.Often, the points that are raised are both legitimate but also shared by others. But sadly, and far too often, we see people speak up but fail to influence others in the way that they had hoped for. Put another way, their message was sound, but their delivery proved faulty. If we could understand this cognitive bias, it holds important implications for how we could craft and mold our messages to have the impact we all desire ... to be more influential as a communicator.Let's exit the aisles of the shopping center and enter a context in which we practice almost automatically every day: the judgment of others. Let me introduce you to two individuals. Tim studies 31 hours a week outside of class. Tom, like Tim, also spends 31 hours outside of class studying. He has a brother and two sisters, he visits his grandparents, he once went on a blind date, plays pool every two months. When participants are asked to evaluate the cognitive aptitude of these individuals, or more importantly, their scholastic achievement, on average, people rate Tim to have a significantly higher GPA than that of Tom. But why? After all, both of them spend 31 hours a week outside of class.Turns out in these contexts, when we're presented such information, our minds utilize two categories of information: diagnostic and nondiagnostic. Diagnostic information is information of relevance to the valuation that is being made. Nondiagnostic is information that is irrelevant or inconsequential to that valuation. And when both categories of information are mixed, dilution occurs. The very fact that Tom has a brother and two sisters or plays pool every two months dilutes the diagnostic information, or more importantly, dilutes the value and weight of that diagnostic information, namely that he studies 31 hours a week outside of class.The most robust psychological explanation for this is one of averaging. In this model, we take in information, and those information are afforded a weighted score. And our minds do not add those pieces of information, but rather average those pieces of information. So when you introduce irrelevant or even weak arguments, those weak arguments, if you will, reduce the weight of your overall argument.A few years ago, I landed in Philadelphia one August evening for a conference. Having just gotten off a transatlantic flight, I checked into my hotel room, put my feet up and decided to distract my jet lag with some TV. An ad caught my attention. The ad was an ad for a pharmaceutical drug. Now if you're the select few who've not had the pleasure of witnessing these ads, the typical architecture of these ads is you might see a happy couple prancing through their garden, reveling in the joy that they got a full night's sleep with the aid of the sleep drug. Because of FDA regulations, the last few seconds of this one-minute ad needs to be devoted to the side effects of that drug. And what you'll typically hear is a hurried voice-over that blurts out "Side effects include heart attack, stroke, blah, blah, blah," and will end with something like "itchy feet."(Laughter)Guess what "itchy feet" does to people's risk assessment of "heart attack" and "stroke"? It dilutes it. Imagine for a moment an alternate commercial that says "This drug cures your sleep problems, side effects are heart attack and stroke." Stop. Now all of a sudden you're thinking, "I don't mind staying up all night."(Laughter)Turns out going to sleep is important, but so is waking up.(Laughter)Let me give you a sample from our research. So this ad that I witnessed essentially triggered a research project with my PhD student, Hemant, over the next two years. And in one of these studies, we presented participants an actual print ad that appeared in a magazine.[Soothing rest for mind and body.]You'll notice the last line is devoted to the side effects of this drug. For half of the participants, we showed the ad in its entirety, which included both major side effects as well as minor side effects. To the other half of the participants, we showed the same ad with one small modification: we extracted just four words out of the sea of text. Specifically, we extracted the minor side effects. And then both sets of participants rated that drug.What we find is that individuals who were exposed to both the major side effects as well as the minor side effects rated the drug's overall severity to be significantly lower than those who were only exposed to the major side effects. Furthermore, they also showed greater attraction towards consuming this drug. In a follow-up study, we even find that individuals are willing to pay more to buy the drug which they were exposed to that had both major side effects as well as minor side effects, compared to just major side effects alone. So it turns out pharmaceutical ads, by listing both major side effects as well as minor side effects, paradoxically dilute participants' and potential consumers' overall risk assessment of that drug.Going beyond shopping expeditions, going beyond the evaluation of the scholastic aptitude of others, and beyond evaluating risk in our environment, what this body of research tells us is that in the world of communicating for the purposes of influence, quality trumps quantity. By increasing the number of arguments, you do not strengthen your case, but rather you actively weaken it. Put another way, you cannot increase the quality of an argument by simply increasing the quantity of your argument. The next time you want to speak up in a meeting, speak in favor of a government legislation that you're deeply passionate about, or simply want to help a friend see the world through a different lens, it is important to note that the delivery of your message is every bit as important as its content.Stick to your strong arguments, because your arguments don't add up in the minds of the receiver, they average out.Thank you.(Applause) A mirror that shatters without warning. A trail of cracker crumbs strewn across the floor. Two tiny handprints that appear on a cake. Everyone at 124 Bluestone Road knows their house is haunted— but there’s no mystery about the spirit tormenting them. This ghost is the product of an unspeakable trauma; the legacy of a barbaric history that hangs over much more than this lone homestead.So begins "Beloved," Toni Morrison’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel about the suffering wrought by slavery and the wounds that persist in its wake. Published in 1987, "Beloved" tells the story of Sethe, a woman who escaped enslavement. When the novel opens, Sethe has been living free for over a decade. Her family has largely dissolved— Sethe’s mother-in-law died years earlier, and her two sons ran away from fear of the specter. Sethe’s daughter Denver remains in the house, but the pair live a half-life. Shunned by the wider community, the two have only each other and the ghost for company. Sethe is consumed by thoughts of the spirit, whom she believes to be her eldest daughter. When a visitor from Sethe’s old life returns and threatens the ghost away, it seems like the start of a new beginning for her family. But what comes in the ghost’s place may be even harder to bear.As with much of Morrison’s work, "Beloved" investigates the roles of trauma and love in African-American history. Morrison writes about black identities in a variety of contexts, but her characters are united by their desire to find love and be loved— even when it’s painful. Some of her novels explore when love challenges social conventions, like the forbidden affection that grows between the townsfolk of "Paradise" and their fugitive Wh neighbors. Other works examine how we can be blind to the love we already y possess. In "Sula," one character realizes that it’s not her marriage, but rather, sho one of her friendships that embodies the great love of her life.Perhaps uld Morrison’s most famous exploration of the difficulty of love takes place in you "Beloved." Here, the author considers how the human spirit is diminished when rea you know the things and people you love most will be taken away. Morrison d shows that slavery is destructive to love in all forms, poisoning both enslaved Toni people and their enslavers. "Beloved" examines the dehumanizing effects of the Mor slave trade in numerous ways. Some are straightforward, such as referring to riso enslaved people as animals with monetary value. But others are more subtle. n's Sethe and Paul D.— the visitor from her old plantation— are described as trying "Bel to “live an unlivable life.” Their coping mechanisms are different; Sethe remains ove mired in her past, while Paul D. dissociates himself completely. But in both d"? cases, it’s clear each character has been irreparably scarred.Morrison also blends perspectives and timelines, to convey how the trauma of slavery ripples across various characters and time periods. As she delves into the psyche of townspeople, enslavers, and previously enslaved people, she exposes conflicting viewpoints on reality. This tension shows the limitations of our own perspectives, and the ways in which some characters are actively avoiding the reality of their actions. But in other instances, the characters’ shifting memories align perfectly; capturing the collective trauma that haunts the story.Though "Beloved" touches on dark subjects, the book is also filled with beautiful prose, highlighting its characters’ capacity for love and vulnerability. In a stream-ofconsciousness sequence written from Sethe’s perspective, Morrison unspools memories of subjugation alongside moments of tenderness; like a baby reaching for her mother’s earrings, spring colors, and freshly painted stairs. Sethe’s mother-in-law had them painted white, she recalls, “so you could see your way to the top… where lamplight didn’t reach."Throughout the book, Morrison asks us to consider hope in the dark, and to question what freedom really means. She urges readers to ponder the power we have over each other, and to use that power wisely. In this way, "Beloved" remains a testimony to the destructiveness of hate, the redeeming power of love, and the responsibility we bear to heed the voices of the past. About three years ago, I lost my daughter. She was sexually assaulted and murdered. She was my only child and was just 19. As the shock wore off and the all-consuming grief took over, I lost all meaning and purpose in life. Then my daughter spoke to me. She asked me to keep living. If I am not around, she will have one less heart to continue to live in. With that, my partner Susan and I started our desperate climb out of this deep hole of trauma and loss. In the 3 journey back to the land of the living with grief, we unexpectedly found a rather way unlikely and very helpful ally: my work.At first, I wasn't even sure if I should go s back to work. I had a lot of self-doubt. As a senior executive, I'm responsible for com thousands of employees and billions of dollars. After all that trauma, is my mind pani still sharp and creative enough for that job? Can I still relate to people? Can I get es past the resentment and regret I felt about all the time I spent working instead of can being with my daughter? Is it fair to leave Susan home alone, dealing with her sup own grief and pain? At the end, I made the decision to go back to work, and I am port very glad I did.We all experience grief and loss in our lives. For most of us, that grie means, at some point, getting up and getting back to work while living with the ving grief. On those days, we will continue to carry the incredible burden of sadness, emp but also a hope that work itself can restore for us that much-needed feeling of loye purpose. For me, work started out as just a productive distraction, but evolved to es being truly therapeutic and meaningful in so many ways. And my return to work proved to be a good thing for the company as well. I know I'm not indispensable, but retaining my expertise proved to be very beneficial, and my return helped all the teams avoid disruptions and distractions. When you lose the most precious thing in your life, you gain a lot of humility and a very different perspective free of egos and agendas, and I think I'm a better coworker and a leader because of that.For all the good that came from it, though, my reentry into work was far from easy. It was very hard. The biggest challenge was having to separate my personal and professional lives completely. You know — OK to cry early in the morning, but slap a smile on the face promptly at eight o'clock and act as if everything is the same as before until the workday is over. Living in two completely different worlds at the same time, and all the hiding and pretending that went with it, it was — it was exhausting, and made me feel very alone.Over time, I worked through those struggles and I gained the confidence and the acceptance to bring my whole self to work. And as a direct result of that, I found joy again in it.During that hard journey back to work, I learned the power of having a culture of empathy in the workplace. Not sympathy, not compassion, but empathy. I came to believe that a workplace where empathy is a core part of the culture, that is a joyful and productive workplace, and that workplace inspires a great deal of loyalty. I believe there are three things a company can do to create and nurture a culture of empathy in the workplace in general and support a grieving employee like myself in particular. One is to have policies that let an employee deal with their loss in peace, without worrying about administrative logistics. Second, provide return-to-work therapy to the employee as an integral part of the health benefits package. And third, provide training for all employees on how to support each other — empathy training, as I call it.In the first category of policies to help deal with the loss, the most important policy is regarding time off. It's true that there is no expiration date to grieve and time cannot undo a loss, but time away from work helped me figure out how daily life can coexist with grief. We don't want a grieving employee to have to cobble together vacation days and sick days and unpaid leave and whatever else. A formal timeoff policy that also allows the employee to come back to the same role they had before their time off — that policy will make a real difference. Personally, I was so grateful to come back to my old role. The familiar work, familiar people, provided a lot of comfort.The second category of help companies can provide to employees is return-to-work therapy. Therapy helped me muster the courage needed to bring my whole self to work and merge the two parallel worlds I was straddling into one, and just have one life. A couple of years ago, I spent a weekend scattering my daughter's ashes in the Pacific. It was a — it was a horrific time. When I returned to work from that that following Monday, one of the first meetings was to arbitrate a very passionate debate on office wallpaper. I needed therapy to figure out how to be considerate of others' normal lives when my own life is so very different. Therapy helped me give myself permission to be vulnerable. Even if vulnerability is not often seen as a strength in the corporate world, when seemingly unrelated and just trivial things triggered deep feelings of sadness right smack in the middle of the workday, therapy helped me deal with them. And when painful anniversaries and events tried to hijack the day, like when I got a call from Texas Rangers regarding an arrest in my child's death, I was at work. Therapy helped me stay productive while still remaining true to the unique realities and the painful realities of my life.During the course of the return-to-work therapy, I had realized something. I had realized that many of those learnings, they would have been very helpful for me at work all along, independent of my loss. And that realization brings me to the final category of things companies can do. Provide empathy training to the employees. Look, I know it sounds odd, but empathy can be a learned behavior. For some, showing empathy comes naturally. A colleague came to see me; I had this electronic photo frame on my desk, rotating through pictures of my daughter. As she was leaving, she simply said, "Tilak, when you're ready, I would love for you to tell me the story behind each of those pictures." She didn't ignore my sadness; she didn't dwell on it. She simply gave me permission to be myself and made a human connection. This was her version of empathy, of which I'm sure there are many.But not everybody is a natural with empathy, and traditional work cultures don't always emphasize empathy. One person said to me, "I can't believe you made it back to work. I don't think I could have done it." Boy, did that make me feel awful. Is my love for my child not strong? Another person decided to be my spokesperson, guiding other folks on how and when to interact with me, all without my knowledge or consent. A few folks just maintained absolute stoic and deafening silence, which in some ways trivialized my loss. Some spent a ton of water-cooler time speculating if I would be any good at all at work, coming back from such a devastating loss. Time, frankly, would have been better spent in figuring out how to help me instead. And then there was that moment where I had to console someone, very distraught, who said, "I understand your loss. My dog died last year."Empathy training can help avoid that inherent awkwardness in dealing with loss. It can give people the confidence to bring their whole self to work, and the people around them, the awareness to accept them for who they are. And together, we'll all be better for it. Empathy training can help people acknowledge that a coworker is a very different person after a life-changing loss, and ask that simple and direct question: what would you like me to do differently to help you?There will come a day when I finally see my daughter, my little girl, again. And as she always did, she's going to make fun of me for working so much. But she knew. She knew that she was the top priority — number one priority. And she will be thankful that work helped Dad live a purposeful life after she was gone.It is such an incredible relief that the loss I experienced is not as common. A child dying ahead of the parent is just absolutely horrific — the most nightmarish and unnatural thing to happen. But loss in itself is not uncommon. When done right, returning to work can help us survive loss and grief. And companies can help do it right, by fostering a culture of empathy in the workplace. It's not a burden or a lot of effort or expense. And creating such a workplace, where empathy is core to the culture — it will be one of the best investments a company can make.Thank you. How many people does it take to make a cup of coffee? For many of us, all it takes is a short walk and a quick pour. But this simple staple is the result of a globe-spanning process whose cost and complexity are far greater than you might imagine.It begins in a place like the remote Colombian town of Pitalito. Here, family farms have clear cut local forests to make room for neat rows of Coffea trees. These shrub-like plants were first domesticated in Ethiopia and are now cultivated throughout equatorial regions. Each shrub is filled with small berries called "coffee cherries." Since fruits on the same branch can ripen at different times, they’re best picked by hand, but each farm has its own method for processing the fruit. In Pitalito, harvesters toil from dawn to dusk at high altitudes, often picking over 25 kilograms per shift for very low wages.The workers deliver their picked cherries to the wet mill. This machine separates the seeds from the fruit, and then sorts them by density. The heaviest, most flavorful seeds sink to the bottom of the mill, where they’re collected and taken to ferment in a tub of water for one or two days. Then, workers wash off the remaining fruit and put the seeds out to dry. Some farms use machines for this process, but in Pitalito, seeds are spread onto large mesh racks. Over the next three weeks, workers rake the seeds regularly to ensure they dry evenly. Once the coffee beans are dry, a truck takes them to a nearby mill with several specialized machines. An air blower re-sorts the seeds by density, an assortment of sieves filter them by size, and an optical scanner sorts by color.At this point, The professionals called Q-graders select samples of beans to roast and brew. In a life process called "cupping," they evaluate the coffee’s taste, aroma, and mouthfeel cycl to determine its quality. These experts give the beans a grade, and get them e of ready to ship. Workers load burlap sacks containing up to 70 kilograms of dried a and sorted coffee beans onto steel shipping containers, each able to carry up to cup 21 metric tons of coffee.From tropical ports, cargo ships crewed by over 25 of people transport coffee around the world But no country imports more coffee coff than the United States, with New York City alone consuming millions of cups ee every day. After the long journey from Colombia to New Jersey, our coffee beans pass through customs. Once dockworkers unload the container, a fleet of eighteen-wheelers transport the coffee to a nearby warehouse, and then to a roastery. Here the beans go into a roasting machine, stirred by a metallic arm and heated by a gas-powered fire. Nearby sensors monitor the coffee’s moisture level, chemical stability, and temperature, while trained coffee engineers manually adjust these levels throughout the twelve-minute roasting cycle. This process releases oil within the seed, transforming the seeds into grindable, brewable beans with a dark brown color and rich aroma. After roasting, workers pack the beans into five-pound bags, which a fleet of vans deliver to cafes and stores across the city.The coffee is now so close you can smell it, but it needs more help for the final stretch. Each coffee company has a head buyer who carefully selects beans from all over the world. Logistics teams manage bean delivery routes, and brave baristas across the city serve this caffeinated elixir to scores of hurried customers.All in all, it takes hundreds of people to get coffee to its intended destination— and that’s not counting everyone maintaining the infrastructure that makes the journey possible. Many of these individuals work for low pay in dangerous conditions— and some aren’t paid at all. So while we might marvel at the global network behind this commodity, let’s make sure we don’t value the final product more than the people who make it. Concrete is all around us, but most of us don't even notice that it's there. We use concrete to build our roads, buildings, bridges, airports; it's everywhere. The only resource we use more than concrete is water. And with population growth and urbanization, we're going to need concrete more than ever. But there's a Ho problem.Cement's the glue that holds concrete together. And to make cement, w you burn limestone with other ingredients in a kiln at very high temperatures. we One of the byproducts of that process is carbon dioxide, or CO2. For every ton coul of cement that's manufactured, almost a ton of CO2 is emitted into the d atmosphere. As a result, the cement industry is the second-largest industrial mak emitter of CO2, responsible for almost eight percent of total global emissions. If e we're going to solve global warming, innovation in both cement production and car carbon utilization is absolutely necessary.Now, to make concrete, you mix bon cement with stone, sand, and other ingredients, throw in a bunch of water, and then wait for it to harden or cure. With precast products like pavers and blocks, neg you might shoot steam into the curing chamber to try to accelerate the curing ativ process. For buildings, roads, and bridges, we pour what's called ready-mix e concrete into a mold on the job site and wait for it to cure over time.Now, for over con 50 years, scientists believed that if they cured concrete with CO2 instead of cret water, it would be more durable, but they were hamstrung by Portland cement's e chemistry. You see, it likes to react with both water and CO2, and those conflicting chemistries just don't make for very good concrete. So we came up with a new cement chemistry.We use the same equipment and raw materials, but we use less limestone, and we fire the kiln at a lower temperature, resulting in up to a 30 percent reduction in CO2 emissions. Our cement doesn't react with water. We cure our concrete with CO2, and we get that CO2 by capturing waste gas from industrial facilities like ammonia plants or ethanol plants that otherwise would've been released into the atmosphere. During curing, the chemical reaction with our cement breaks apart the CO2, capturing the carbon to make limestone, and that limestone's used to bind the concrete together.Now, if a bridge made out of our concrete were ever demolished, there's no fear of the CO2 being emitted because it doesn't exist any longer. When you combine the emissions reduction during cement production with the CO2 consumption during concrete curing, we reduce cement's carbon footprint by up to 70 percent. And because we don't consume water, we also save trillions of liters of water.Now, convincing a 2,000-year-old industry that hasn't evolved much over the last 200 years, is not easy; but there are lots of new and existing industry players that are attacking that challenge. Our strategy is to ease adoption by seeking solutions that go beyond just sustainability. We use the same processes, raw material, and equipment that's used to make traditional concrete, but our new cement makes concrete cured with CO2 that is stronger, more durable, lighter in color, and it cures in 24 hours instead of 28 days.Our new technology for ready-mix is in testing and infrastructure applications, and we've pushed our research even further to develop a concrete that may become a carbon sink. That means that we will consume more CO2 than is emitted during cement production. Since we can't use CO2 gas at a construction site, we knew we had to deliver it to our concrete in either a solid or liquid form. So we've been partnering with companies that are taking waste CO2 and transforming it into a useful family of chemicals like oxalic acid or citric acid, the same one you use in orange juice. When that acid reacts with our cement, we can pack in as much as four times more carbon into the concrete, making it carbon negative. That means that for a one-kilometer road section, we would consume more CO2 than almost a 100,000 trees do during one year.So thanks to chemistry and waste CO2, we're trying to convert the concrete industry, the second-most-used material on the planet, into a carbon sink for the planet.Thank you. Ho In 1942, a mother-daughter duo Katherine Cook Briggs and Isabel Briggs Myers w developed a questionnaire that classified people’s personalities into 16 types. do Called the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, or MBTI, it would go on to become one per of the world’s most widely-used personality tests.Today, personality testing is a son multi-billion dollar industry used by individuals, schools, and companies. But ality none of these tests, including the MBTI, the Big Five, the DiSC assessment, the test Process Communication Model, and the Enneagram, actually reveal truths about s personality. In fact, it’s up for debate whether personality is a stable, measurable wor feature of an individual at all.Part of the problem is the way the tests are k? constructed. Each is based on a different set of metrics to define personality: the Myers-Briggs, for instance, focuses on features like introversion and extroversion to classify people into personality "types," while the Big Five scores participants on five different traits. Most are self-reported, meaning the results are based on questions participants answer about themselves. So it’s easy to lie, but even with the best intentions, objective self-evaluation is tricky.Take this question from the Big Five: How would you rate the accuracy of the statement "I am always prepared"?There’s a clear favorable answer here, which makes it difficult to be objective. People subconsciously aim to please: when asked to agree or disagree, we show a bias toward answering however we believe the person or institution asking the question wants us to answer.Here’s another question— what do you value more, justice or fairness? What about harmony or forgiveness?You may well value both sides of each pair, but the MBTI would force you to choose one. And while it’s tempting to assume the results of that forced choice must somehow reveal a true preference, they don’t: When faced with the same forced choice question multiple times, the same person will sometimes change their answer.Given these design flaws, it’s no surprise that test results can be inconsistent. One study found that nearly half of people who take the Myers-Briggs a second time only five weeks after the first get assigned a different type. And other studies on the Myers-Briggs have found that people with very similar scores end up being placed in different categories, suggesting that the strict divisions between personality types don’t reflect real-life nuances.Complicating matters further, the definitions of personality traits are constantly shifting. The Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung, who popularized the terms introvert and extrovert, defined an introvert as someone who sticks to their principles regardless of situation, and an extrovert as someone who molds their self according to circumstance. Introversion later came to mean shyness, while an extrovert was someone outgoing. Today, an introvert is someone who finds alone time restorative, an extrovert draws energy from social interaction, and an ambivert falls somewhere between these two extremes.The notion of an innate, unchanging personality forms the basis of all these tests. But research increasingly suggests that personality shifts during key periods— like our school years, or when we start working. Though certain features of a person’s behavior may remain relatively stable over time, others are malleable, moulded by our upbringing, life experiences, and age.All of this matters more or less depending on how a personality test is used. Though anyone using them should take the results with a grain of salt, there isn’t much harm in individual use— and users may even learn some new terms and concepts in the process. But the use of personality tests extends far beyond self discovery. Schools use them to advise students what to study and what jobs to pursue. Companies use them decide who to hire and for what positions. Yet the results don’t predict how a person will perform in a specific role. So by using personality tests this way, institutions can deprive people of opportunities they’d excel at, or discourage them from considering certain paths. Throughout six centuries, the Ghent Altarpiece has been burned, forged, and raided in three different wars. It is, in fact, the world’s most stolen artwork. And while it’s told some of its secrets, it’s kept others hidden.In 1934, the police of Ghent, Belgium heard that one of the Altarpiece’s panels, split between its front and back, was suddenly gone. The commissioner investigated the scene but determined that a theft at a cheese shop was more pressing. Twelve ransom notes appeared over the following months and one half of the panel was even returned as a show of good faith. Meanwhile, art restorer Jef van der Veken made a replica of the other half for display until it was found. But it never was. Some suspected that he was involved in the theft and, once ransom demands failed, had simply painted over the original and presented it as his copy. But a definitive answer wouldn’t come for decades.Just six years later, Hitler was planning a grand museum, but was missing his most desired possession: the Ghent Altarpiece. As Nazi forces advanced, Belgian leaders sent the painting to France. But the Nazis commandeered and moved it to a salt mine converted into a stolen art warehouse that contained over 6,000 masterpieces. Near the war’s The end in 1945, a Nazi official decided he’d rather blow up the mine before letting it stra fall into Allied hands.In fact, the Allies had soldiers called Monuments Men who nge were tasked with protecting cultural treasures. Two of them were stationed 570 hist kilometers away when one got a toothache. They visited a local dentist, who ory mentioned that his son-in-law also loved art and took them to meet him. They of discovered that he was actually one of the Nazi’s former art advisors, now in the hiding. And miraculously, he told them everything. The Monuments Men devised worl a plan to rescue the art and the local Resistance delayed the mine’s destruction d's until they arrived. Inside, they found the Altarpiece among other world mos treasures.The Ghent Altarpiece, also called "The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb" t after its central subject, consists of 12 panels depicting the Biblical story. It’s one stol of the most influential artworks ever made. When Jan van Eyck completed it in en Ghent in 1432, it was immediately deemed the best painting in Europe.For pain millennia, artists used tempera paint consisting of ground pigment in egg yolk, ting which created vivid but opaque colors. The Altarpiece was the first to showcase the unique abilities of oil paint. They allowed van Eyck to capture light and movement in a way that had never been seen before. He did this using brushes sometimes as tiny as a single badger hair. And by depicting details like Ghent landmarks, botanically identifiable flowers, and lifelike faces, the Altarpiece pioneered an artistic mode that would come to be known as Realism.Yet, conservation work completed in 2019 found that, for centuries, people had been viewing a dramatically altered version. Due to dozens of restorations, as much as 70% of certain sections had been painted over. As conservators removed these layers of paint, varnish, and grime, they discovered vibrant colors and whole buildings that had long been invisible. Other details were more unsettling.The mystic lamb’s four ears had long perplexed viewers. But the conservation team revealed that the second pair was actually a pentimento— the ghost of underlying layers of paint that emerge as newer ones fade. Restorers had painted over the original lamb with what they deemed a more palatable version. They removed this overpainting and discovered the original to be shockingly humanoid.The conservators also finally determined whether van der Veken had simply returned the missing panel from 1934. He hadn’t. It was confirmed to be a copy, meaning the original is still missing. But there was one final clue. A Ghent stockbroker, while on his deathbed a year after the theft, revealed an unsent ransom note. It reads: it “rests in a place where neither I, nor anybody else, can take it away without arousing the attention of the public.” A Ghent detective remains assigned to the case but, while there are new tips every year, it has yet to be found. Let me tell you a story about artificial intelligence. There's a building in Sydney at 1 Bligh Street. It houses lots of government apartments and busy people. From 6 the outside, it looks like something out of American science fiction: all gleaming big glass and curved lines, and a piece of orange sculpture. On the inside, it has ethi excellent coffee on the ground floor and my favorite lifts in Sydney. They're cal beautiful; they look almost alive. And it turns out I'm fascinated with lifts. For lots que of reasons. But because lifts are one of the places you can see the future.In the stio 21st century, lifts are interesting because they're one of the first places that AI ns will touch you without you even knowing it happened. In many buildings all abo around the world, the lifts are running a set of algorithms. A form of protoartificial ut intelligence. That means before you even walk up to the lift to press the button, the it's anticipated you being there. It's already rearranging all the carriages. Always futu going down, to save energy, and to know where the traffic is going to be. By the re time you've actually pressed the button, you're already part of an entire system of that's making sense of people and the environment and the building and the built AI world.I know when we talk about AI, we often talk about a world of robots. It's easy for our imaginations to be occupied with science fiction, well, over the last 100 years. I say AI and you think "The Terminator." Somewhere, for us, making the connection between AI and the built world, that's a harder story to tell. But the reality is AI is already everywhere around us. And in many places. It's in buildings and in systems. More than 200 years of industrialization suggest that AI will find its way to systems-level scale relatively easily. After all, one telling of that history suggests that all you have to do is find a technology, achieve scale and revolution will follow.The story of mechanization, automation and digitization all point to the role of technology and its importance. Those stories of technological transformation make scale seem, well, normal. Or expected. And stable. And sometimes even predictable. But it also puts the focus squarely on technology and technology change. But I believe that scaling a technology and building a system requires something more.We founded the 3Ai Institute at the Australian National University in September 2017. It has one deceptively simple mission: to establish a new branch of engineering to take AI safely, sustainably and responsibly to scale. But how do you build a new branch of engineering in the 21st century? Well, we're teaching it into existence through an experimental education program. We're researching it into existence with locations as diverse as Shakespeare's birthplace, the Great Barrier Reef, not to mention one of Australia's largest autonomous mines. And we're theorizing it into existence, paying attention to the complexities of cybernetic systems. We're working to build something new and something useful. Something to create the next generation of critical thinkers and critical doers. And we're doing all of that through a richer understanding of AI's many pasts and many stories. And by working collaboratively and collectively through teaching and research and engagement, and by focusing as much on the framing of the questions as the solving of the problems.We're not making a single AI, we're making the possibilities for many. And we're actively working to decolonize our imaginations and to build a curriculum and a pedagogy that leaves room for a range of different conversations and possibilities. We are making and remaking. And I know we're always a work in progress. But here's a little glimpse into how we're approaching that problem of scaling a future.We start by making sure we're grounded in our own history. In December of 2018, I took myself up to the town of Brewarrina on the New South Wales-Queensland border. This place was a meeting place for Aboriginal people, for different groups, to gather, have ceremonies, meet, to be together. There, on the Barwon River, there's a set of fish weirs that are one of the oldest and largest systems of Aboriginal fish traps in Australia. This system is comprised of 1.8 kilometers of stone walls shaped like a series of fishnets with the "Us" pointing down the river, allowing fish to be trapped at different heights of the water. They're also fish holding pens with different-height walls for storage, designed to change the way the water moves and to be able to store big fish and little fish and to keep those fish in cool, clear running water. This fish-trap system was a way to ensure that you could feed people as they gathered there in a place that was both a meeting of rivers and a meeting of cultures.It isn't about the rocks or even the traps per se. It is about the system that those traps created. One that involves technical knowledge, cultural knowledge and ecological knowledge. This system is old. Some archaeologists think it's as old as 40,000 years. The last time we have its recorded uses is in the nineteen teens. It's had remarkable longevity and incredible scale. And it's an inspiration to me. And a photo of the weir is on our walls here at the Institute, to remind us of the promise and the challenge of building something meaningful. And to remind us that we're building systems in a place where people have built systems and sustained those same systems for generations.It isn't just our history, it's our legacy as we seek to establish a new branch of engineering. To build on that legacy and our sense of purpose, I think we need a clear framework for asking questions about the future. Questions for which there aren't ready or easy answers. Here, the point is the asking of the questions. We believe you need to go beyond the traditional approach of problem-solving, to the more complicated one of question asking and question framing. Because in so doing, you open up all kinds of new possibilities and new challenges.For me, right now, there are six big questions that frame our approach for taking AI safely, sustainably and responsibly to scale. Questions about autonomy, agency, assurance, indicators, interfaces and intentionality.The first question we ask is a simple one. Is the system autonomous? Think back to that lift on Bligh Street. The reality is, one day, that lift may be autonomous. Which is to say it will be able to act without being told to act. But it isn't fully autonomous, right? It can't leave that Bligh Street building and wonder down to Circular Quay for a beer. It goes up and down, that's all. But it does it by itself. It's autonomous in that sense.The second question we ask: does this system have agency? Does this system have controls and limits that live somewhere that prevent it from doing certain kinds of things under certain conditions. The reality with lifts, that's absolutely the case. Think of any lift you've been in. There's a red keyslot in the elevator carriage that an emergency services person can stick a key into and override the whole system. But what happens when that system is AI-driven? Where does the key live? Is it a physical key, is it a digital key? Who gets to use it? Is that the emergency services people? And how would you know if that was happening? How would all of that be manifested to you in the lift?The third question we ask is how do we think about assurance. How do we think about all of its pieces: safety, security, trust, risk, liability, manageability, explicability, ethics, public policy, law, regulation? And how would we tell you that the system was safe and functioning?The fourth question we ask is what would be our interfaces with these AI-driven systems. Will we talk to them? Will they talk to us, will they talk to each other? And what will it mean to have a series of technologies we've known, for some of us, all our lives, now suddenly behave in entirely different ways? Lifts, cars, the electrical grid, traffic lights, things in your home.The fifth question for these AI-driven systems: What will the indicators be to show that they're working well? Two hundred years of the industrial revolution tells us that the two most important ways to think about a good system are productivity and efficiency. In the 21st century, you might want to expand that just a little bit. Is the system sustainable, is it safe, is it responsible? Who gets to judge those things for us? Users of the systems would want to understand how these things are regulated, managed and built.And then there's the final, perhaps most critical question that you need to ask of these new AI systems. What's its intent? What's the system designed to do and who said that was a good idea? Or put another way, what is the world that this system is building, how is that world imagined, and what is its relationship to the world we live in today? Who gets to be part of that conversation? Who gets to articulate it? How does it get framed and imagined?There are no simple answers to these questions. Instead, they frame what's possible and what we need to imagine, design, build, regulate and even decommission. They point us in the right directions and help us on a path to establish a new branch of engineering. But critical questions aren't enough. You also need a way of holding all those questions together.For us at the Institute, we're also really interested in how to think about AI as a system, and where and how to draw the boundaries of that system. And those feel like especially important things right now. Here, we're influenced by the work that was started way back in the 1940s. In 1944, along with anthropologists Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, mathematician Norbert Wiener convened a series of conversations that would become known as the Macy Conferences on Cybernetics. Ultimately, between 1946 and 1953, ten conferences were held under the banner of cybernetics. As defined by Norbert Wiener, cybernetics sought to "develop a language and techniques that will enable us to indeed attack the problem of control and communication in advanced computing technologies." Cybernetics argued persuasively that one had to think about the relationship between humans, computers and the broader ecological world. You had to think about them as a holistic system. Participants in the Macy Conferences were concerned with how the mind worked, with ideas about intelligence and learning, and about the role of technology in our future.Sadly, the conversations that started with the Macy Conference are often forgotten when the talk is about AI. But for me, there's something really important to reclaim here about the idea of a system that has to accommodate culture, technology and the environment. At the Institute, that sort of systems thinking is core to our work.Over the last three years, a whole collection of amazing people have joined me here on this crazy journey to do this work. Our staff includes anthropologists, systems and environmental engineers, and computer scientists as well as a nuclear physicist, an award-winning photo journalist, and at least one policy and standards expert. It's a heady mix. And the range of experience and expertise is powerful, as are the conflicts and the challenges. Being diverse requires a constant willingness to find ways to hold people in conversation. And to dwell just a little bit with the conflict.We also worked out early that the way to build a new way of doing things would require a commitment to bringing others along on that same journey with us. So we opened our doors to an education program very quickly, and we launched our first master's program in 2018. Since then, we've had two cohorts of master's students and one cohort of PhD students. Our students come from all over the world and all over life. Australia, New Zealand, Nigeria, Nepal, Mexico, India, the United States. And they range in age from 23 to 60. They variously had backgrounds in maths and music, policy and performance, systems and standards, architecture and arts. Before they joined us at the Institute, they ran companies, they worked for government, served in the army, taught high school, and managed arts organizations. They were adventurers and committed to each other, and to building something new. And really, what more could you ask for?Because although I've spent 20 years in Silicon Valley and I know the stories about the lone inventor and the hero's journey, I also know the reality. That it's never just a hero's journey. It's always a collection of people who have a shared sense of purpose who can change the world. So where do you start?Well, I think you start where you stand. And for me, that means I want to acknowledge the traditional owners of the land upon which I'm standing. The Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, this is their land, never ceded, always sacred. And I pay my respects to the elders, past and present, of this place. I also acknowledge that we're gathering today in many other places, and I pay my respects to the traditional owners and elders of all those places too.It means a lot to me to get to say those words and to dwell on what they mean and signal. And to remember that we live in a country that has been continuously occupied for at least 60,000 years. Aboriginal people built worlds here, they built social systems, they built technologies. They built ways to manage this place and to manage it remarkably over a protracted period of time. And every moment any one of us stands on a stage as Australians, here or abroad, we carry with us a privilege and a responsibility because of that history. And it's not just a history. It's also an incredibly rich set of resources, worldviews and knowledge. And it should run through all of our bones and it should be the story we always tell.Ultimately, it's about thinking differently, asking different kinds of questions, looking holistically at the world and the systems, and finding other people who want to be on that journey with you. Because for me, the only way to actually think about the future and scale is to always be doing it collectively. And because for me, the notion of humans in it together is one of the ways we get to think about things that are responsible, safe and ultimately, sustainable.Thank you. Non e In May of 1822, Count Christian Ludwig von Bothmer shot down a stork over his castle grounds in North Germany. However, he wasn’t the first person to hunt that specific bird. Upon recovering the stork, von Bothmer found it impaled by a yard long wooden spear. A local professor determined the weapon was African in origin, suggesting that somehow, this stork was speared in Africa and then flew over 2,500 kilometers to the count’s castle. This astonishing flight wasn’t just evidence of the stork’s resilience. It was an essential clue in a mystery that plagued scientists for centuries: the seasonal disappearance of birds.Ancient naturalists had various theories to explain the annual vanishing act we now know as migration. Aristotle himself proposed three particularly popular ideas. One theory was that birds transformed into different bodies that suited the 3 season. For example, summer time garden warblers were believed to transform biza into black caps every winter. In reality these are two distinct species— similar in rre shape and size, but never appearing at the same time. Over the following (an centuries, birds were said to morph into humans, plants, and even the timbers of d ships. This last transmutation was especially popular with many Christian clergy. deli If barnacle geese were truly made of wood, they could be deemed vegetarian ghtf and enjoyed during meatless fasts.Aristotle’s second and even more enduring ul) hypothesis was that birds hibernate. This isn’t so far-fetched. Some species do anci enter short, deep sleeps which lower their heart rates and metabolisms. And ent there’s at least one truly hibernating bird: the common poorwill sleeps out the winters in the deserts of North America. But researchers were proposing much orie more outlandish forms of hibernation well into the 19th century. Barn swallows s were said to remove their feathers and hibernate in holes, or sleep through the abo winter at the bottom of lakes and rivers.Aristotle’s final theory was much more ut reasonable, and resembled something like realistic migration. However, this idea bird was also taken to extremes. In 1666, the leading migration advocate was mig convinced that each winter, birds flew to the moon.It might seem strange that rati prominent researchers considered such bizarre ideas. But to be fair, the true on story of migration may be even harder to believe than their wildest theories. Roughly 20% of all bird species migrate each year, following warm weather and fresh food around the planet. For birds who spend their summers in the northern hemisphere, this journey can span from 700 to over 17,000 kilometers, with some flights lasting as long as four months. Birds who migrate across oceans may soar without stopping for over 100 hours. Sleeping and eating on the fly, they navigate the endless ocean by the stars, wind currents, and Earth’s magnetic field.Tracking the specifics of these epic expeditions is notoriously difficult. And while birds often take the most direct route possible, storms and human development can alter their paths, further complicating our attempts to chart migration.Fortunately, Count von Bothmer’s stork offered physical proof not only that European storks were migrating south for the winter, but also where they were migrating to. Ornithologists across the continent were eager to map the trajectory of this flight, including Johannes Thienemann. Owner of the world’s first permanent bird observatory, Thienemann was a major public advocate for the study of birds. And to solve the field’s biggest mystery, he wrangled an army of volunteers from across Germany.His team used aluminum rings to tag the legs of two thousand storks with unique numbers and the address of his offices. Then he advertised the initiative as widely as possible. His hope was that word of the experiment would find its way to Africa, so people finding the tags would know to mail them back with more information. Sure enough, from 1908 to 1913, Thienemann received 178 rings, 48 of which had been found in Africa. Using this data, he plotted the first migration route ever discovered, and definitively established that storks were not, in fact, flying to the moon. Fina Whitney Pennington Rodgers: Ajay Banga, thank you so much for being with us ncia today. I feel like this conversation is especially meaningful as we're wading l through this pandemic, it's late 2020, and we've seen the way that inequalities incl have presented themselves throughout this year, through this crisis. And since usio you've been at the helm of Mastercard, you have championed this idea of n, financial inclusion. And so, could you start by telling us a little bit about financial the inclusion, what is it and why do you think this is something that can change digi people's lives?Ajay Banga: Yes, look, I think that the COVID-19 crisis has tal actually made things worse in some ways and some of the advances that were divi being made over the prior decade on fighting poverty and fighting exclusion de have probably got set back a little bit, just by the nature of the manner in which and the virus has impacted minorities and disadvantaged people more than they oth have others, including, by the way, minority-owned businesses, a number of er whom have had disproportionate impact through the crisis.But I guess if you pull tho back from the crisis, because financial inclusion or exclusion is an underlying ugh social problem that dates back to well before this. The real issue, here's the ts theory of the case. Of seven billion people in the world, close to two billion are on either underbanked or unbanked in some way. And what I mean by underbanked the or unbanked — unbanked is obvious, they don't have a relationship with a futu banking institution of any type. Of any type. Now, underbanked is, even if they re do, they're not getting to participate in the financial mainstream and do things of that you and I take for granted, which means being able to access credit when mo you need it, at a reasonable price, being able to access insurance of the type ney that's relevant to you, being able to do things of that nature, save for a rainy day in the right way. All that done in a form that's good for you as the consumer. That's underbanked.And so, a couple of billion people around the world, this is World Bank statistics, are basically unbanked or underbanked, and most of those people do not have a formal identity that they had received or got from their government and therefore, there's nothing they can take and hold out to show when they go to hire a car or live in a hotel or take a flight, which they don't do, to show that they exist in the system. Their opinions don't count, they don't get counted in censuses very often, they don't get counted for their opinion of what government should be doing, they get left out, they're locked out.And the last part of that puzzle is that this is too big an issue, over the years, for just a government to solve, or for just one bank to solve in a country. It does require, kind of, a bunch of shoulders at the wheel to come together, it requires partnerships across the public and the private sector, but even within the private sector, to get to make a real movement on this issue.WPR: So if I'm understanding correctly, it sounds like it's just an opportunity for people no matter where you are, what your socioeconomic status is, that you have access to financial services, that you are part of the system and you have a place, a financial identity.AB: You have identity, you have a voice, you have access to financial services. So financial inclusion has got so many facets, but the basic facet is be counted, be included, be somebody, have the dignity of your identity, and of being included. That's really what financial inclusion is.WPR: It seems like such a simple idea, that can potentially have a big impact, and I know that this is something that you've implemented in your work at Mastercard, but also we see this in many other organizations, so talk a little bit about what does financial inclusion look like in practice for a range of different organizations and a range of different spaces.AB: First of all, you're absolutely correct, there are lots of people participating in trying to change this. And honestly, without that, we wouldn't get anywhere. We're doing our bit, but what we're doing is really in partnership with others, because we're not a direct-to-consumer company. There's nothing I can do to improve your life directly in terms of being included because I don't open bank accounts, I don't give credit, I don't underwrite insurance and I don't have a way to provide you ways to save money in a mutual fund or anything. For me to do anything, I need to have banks, I need to have fintechs, I need to have mobile phone companies, I need to have governments, I probably need to have merchants and that ecosystem of the coalition of the willing is kind of what you will see represented when different companies talk about their role in financial inclusion. Let me give you a couple of tangible examples.So if you're a farmer and you've got to go to sell your produce when it's harvested, you've got to go two days' way to the nearest village market, well then, everybody knows that on the way back you're carrying cash from the produce you sold. That normally leads to bad outcomes. Also, you've got to go buy fertilizer. Or you've got to go back and forth to do all this and you're really unproductive, or you send your spouse to do it. All that changes if I can connect you with a phone into farmers, fertilizers and cooperatives, give you cropping information, rainfall information, enable you to sell your produce in a better marketplace, online, receive the money into an account online, that is a complete game changer. Something again that farmer's cooperatives, local governments, banks and companies like ours can help facilitate, in Africa, we're doing it in India, we're doing it in a bunch of countries around the world. Again, the idea here is to take you out of the cash economy and give you access to an electronic economy.Imagine that same farmer, they now receive money for their produce, a bank can look at how they spend money out of their account, and could, using the spending and receiving of money, underwrite you much better for a crop loan than they could if they didn't know anything about you.So the same example, another one, is for small and microbusinesses. Take a woman in Kenya or in India or in Mexico in a village who opens a small shop outside her home when her husband and children are away. And it runs for a few hours in a day, and she stocks a little baby food, and soap and toilet paper and whatever else people buy there. Well when the company van comes, the Nestle van, the Unilever van, the local Bimbo Bread van, comes to sell produce to her on a Monday or a Tuesday or a Wednesday at a certain time, she buys what she can in cash. Typically, she's in the cash economy, nobody’s given her credit, she runs out of cash for that produce that she's buying before the week is over. She's out of stock. She loses sales. Imagine if she could then be underwritten, digitizing that supply chain, what she bought, what she sold, underwrite her in a bank with actual transaction history, you could lend her the 500 dollars to enable her to be smarter about what she buys, educate her on how to use her credit, that's financial inclusion.WPR: And so one thing that's really struck me as you're talking through what financial inclusion looks like and how it works, is the dependency on technology, on smartphones, on internet access, and we know that this is something that a lot of people struggle to have access to this in developing nations, even in developed countries. Talk a little bit about how this might in some ways increase the digital divide, and sort of, how you respond to people who might criticize this idea in that way.AB: There are two topics you just came across, the digital divide, which I think is a real issue. But just to be clear, all the examples I gave you, they work on smartphones and they work on old flip phones as well. That QR code, if you have a camera on your smartphone, you can take it, but there's a numerical number there, you could enter that number into your finger phone and get it across as well. Examples like that in Egypt, where we've opened mobile wallets on phones, they don't have to be on a smartphone, it could be on an old phone. So to be clear, these financial inclusion examples do not depend on smartphones, they do not depend on just internet access in your house, you do need a phone, a cell phone, in a number of the examples I gave you. But in the case of the micro and small credit enterprises, you don't even need a phone. That actually is just the transaction history of the produce you bought and what you sold getting digitized and a bank being able to underwrite. There are other problems of infrastructure in those that we can talk about.But to be specific about the digital divide, I think that's another real big issue and again, COVID-19 has actually, unfortunately, exposed what was already sort of an issue in society. So whether it's rural parts of America, let alone an African or Indian or Indonesian or Guatemalan example, in America, in rural parts of America, broadband access is a problem. Disadvantaged children in New York City, who may not have access to the same bandwidth capacity or computers that they need to be able to participate in education, that's a problem. And so, that's a separate issue, Whitney, from the issue of some of the examples I gave you, which I think can actually be operated equally well with old-fashioned phones.WPR: It seems like a precursor to this is in talking about these partnerships with governments, perhaps, is making sure people do have even access to a flip phone or some sort of way that they can communicate so they can participate in these initiatives.AB: So I think a phone is transformational and the fact is that there are many people in the world with a phone, but there's still a billion people who do not have the right kind of phone or internet access. That's a different topic. So that said, you've got to find ways to reach them too. You can't only do it by phone. So the example of those micro SMEs I was talking about, they've got nothing to do with a phone. Or for example, in South Africa, with the social security administration where the government gives them a certain amount of money every year for their being not employed, you can actually reach them through a biometric card, which is what we've done, with the government, the government collects your identity, your biometrics on a card, and we can load the card remotely with the amount they want to transfer, take out the middleman in the process, and allow that person to then use that card to go to an ATM to take out their cash, or go straight to a shop to shop. And I think that changes everything. So we've done that in many countries.And so if you go to where Syrian refugees were coming in to Lebanon and Greece and the like, every aid agency there would require them to have an identity with them to get access to whatever form of aid they were dispersing. One of the things we're doing is to convert that into a very simple biometric-enabled identity which will be read across aid agencies, so you or I don't need to get our identity verified separately each time. There is a statistic in the world that 40 percent of the dollars that governments want to spend to reach their citizenry for social benefit programs never reach them. They are called leakage. Leakage means administrative costs and I call it theft. Because it's 40 less cents on a dollar for the person who cannot afford even one cent less. That's the issue. That's what we're trying to solve for.Take out middlemen, use technology to help, enable a direct government to citizenry operation, allow banks and NGOs and foreign companies to intervene in the right way, as in the example of this refugee crisis. The World Food Programme distributes food in those very refugee camps. And we actually help them to take the food, they would buy grain somewhere and ship it across, and lose some of it along the way, we put the dollar value on a card, the card can only be used by the refugee in a shop that the World Food Programme certifies. So it cannot be used for anything other than what the World Food Programme wants it used for, which is grain and food and vegetables and fruit and milk. And that enables the World Food Programme to save money on leakage.What I'm trying to tell you is it's not about technology, it's about using what you have and using the technology you do possess and applying that in a smart, commercially sustainable way to real world problems. If you have good technology as well, well let's do it even better. But let's not use technology as the excuse to not do it.WPR: OK. It makes a lot of sense now. It seems like underlying all of this is this move towards a cashless society. This move to sort of create this way for people to exchange money without the need for cash. I'm curious to hear from you a little bit about what does that actually look like, you know, a society without cash. What are some of the challenges that is presents?AB: Yeah, I think cashless, actually, is something we are not going to get to, and we probably shouldn't. Because just as we have a digital divide, do you really want a world where people who rely on cash because it makes them comfortable, I'm not talking about illegal transactions, I'm talking about somebody who just wants to deal in cash, they may be older and uncomfortable with today's technology.My dad, when he was alive, you know, he never wanted to use a card. He always wanted to use a cash and check. And this is my father, when I worked in banking and was by then the CEO of Mastercard, and he would look at me very indulgently and say, "Son, now I have a Mastercard because of you, but could you please go away" kind of thing. And I understand that.And I think you've got to deal with therefore "cashless," in inverted commas. Reducing cash in the economy is to me a good objective. Taking it to zero? I'm not there. Why do I say it's a good objective to reduce it? Because cash actually is the friend of the person who has something to hide. If you want to not pay your full taxes, or you want to do something with the cash which is not quite kosher, well guess what, here's your chance. But if you're electronic, you are transparent. Electronic forms of money benefits and transfers in utilization, create transparency in an economy. Poorer people, they don't have access to cash, and therefore, they don't indulge any of this.But even other than that, even other than all this, there is a cost of cash in society which many people have computed, central banks, universities, somewhere between one to two percent of GDP is the cost of printing, securing, distributing and using that cash. One to two percent of GDP. I'm certain there are efficient uses of that GDP that we could put into play by reducing the role of cash relatively in the economy. In the process, you take out these middlemen who are in positions of power when social benefits are distributed, when refugees are met. That's what I'm talking about. That to me is a good thing. Transparent, better tax realizations, lower money laundering, that kind of stuff I'm all for, and I've been talking about that for years. But zero cash, I'm not there.WPR: And do you think there is a point where you do get there, or we get there as a society, where that does feel possible?AB: We could. I mean, if you took countries in the Nordics, take Sweden. Sweden, South Korea, these are at the cutting edge of having reduced cash in their economies. In Sweden, essentially everybody uses electronic forms of payments, either a card or app on their phone that they can swish through or things of that nature, consumer payments I'm talking about. Even public toilets on the street in Sweden you can pay by on your phone entering a code, which comes back to you, having deducted that money from your account. You enter the code on a pin pad and I call that tap and go, you go into the public toilet with that tap. That's how far it's advanced in Sweden. So cash is very low there. But even they are having a regular, continuous public conversation about not disadvantaging those parts of Sweden who still want to deal in cash.You've got to be careful, because remember how does cash reach distributed points in a country? Through banks, through ATMs. If those become unprofitable to run and people start closing the ATMs down, that's a problem in itself. So you have to enable cash back in retailers in some way, so that you could still go and get cash from a distribution system. Maybe not an ATM, but a retailer. There are some ways to do this well, but you've got to be conscious of it. You know, we haven't reached it yet, but we could. We haven't reached it yet.WPR: Of course, when you think about this, about moving to a cashless society or at least having that as the goal, that creates this concern around data and privacy and you've said in the past that there's really an importance behind putting consumers in control of their own data and their own privacy. How is that something that we can actually achieve, what does it look like to do that?AB: Whitney, it's a terrific question. I actually believe that it's at the core of a lot to do with the next 10, 20 years of technology, the internet of things, 5G, data, this is all coming together at warp speed, right? If you think about the number of devices that are going to be connected over the next five, ten years, and what 5G could do to moving intelligent computing to the edge right near you, this is going to generate enormous amounts of data. From your fridge, from your car, from you walking around, from your connected glasses, from your watch already, all that. From your shoes if you're a runner. So you've got to get to a stage where we take a responsibility of how your data is used and interpreted.And so, Mastercard, we with a bunch of companies, we have laid out a set of data principles. The first one is exactly what you said. It's your data, you should control it. Meaning you should know what's being collected, you should be able to say, "I don't want that to be collected," in simple language, not in a 12-page legal agreement that you cannot comprehend. And you should be able to benefit from that data of yours that is used, either directly, or indirectly in some way that you comprehend. And if I as a company am collecting your data to enable me to do business with you, I should collect the minimum amount I need to do my job with you and I should keep whatever I collect safe for you, and allow it to be deducted or removed when you want it.These are not complicated things. Your data, you're in control, you should be able to delete it when you want, you should know what's being collected. If I do anything with you, collect the minimum, keep it safe. Consumers will vote with their feet on this topic. As they get more knowledgeable, as they get more educated, and that's the right thing to do, they need to say, "I don't want you to use my data for the following things. I want to know what it's being used for." Putting consumer back in control of their data is going to be mission critical in the data-driven economy of the next 10, 20 years.WPR: Thank you so much, Ajay, this was a great conversation and we appreciate you being with us today.AB: Thanks a lot, see you again. Good luck. Wh Take a ride in Emily Dickinson's chariot. But beware... there's no turning back. at "Because I could not stop for Death" by Emily Dickinson Because I could not hap stop for Death – He kindly stopped for me – The Carriage held but just pen Ourselves – And Immortality.We slowly drove – He knew no haste And I had put s away My labor and my leisure too, For His Civility –We passed the School, whe where Children strove At Recess – in the Ring – We passed the Fields of Gazing n Grain – We passed the Setting Sun –Or rather – He passed Us – The Dews you drew quivering and Chill – For only Gossamer, my Gown – My Tippet – only die? Tulle –We paused before a House that seemed A Swelling of the Ground – The A Roof was scarcely visible – The Cornice – in the Ground –Since then – 'tis poe Centuries – and yet Feels shorter than the Day I first surmised the Horses' tic Heads Were toward Eternity – inq uiry People say that a long, long time ago, everybody on earth spoke the same language and belonged to the same tribe. And I guess people had a little too much time on their hands, because they decided they were going to work together to become as great as God. So they started to build a tower up into the heavens. God saw this and was angry, and to punish the people for their arrogance, God destroyed the tower and scattered the people to the ends of the earth and made them all speak different languages.This is the story of the Tower of Babel, and it's probably not a literal historical truth, but it does tell us something about the way that we understand languages and speakers. So for one thing, we often think about speaking different languages as meaning that we don't get along or maybe we're in conflict, and speaking the same language as meaning that we belong to the same group and that we can work together.Modern linguists know that the relationship between language and social categories is intricate and complex, and we bring a lot of baggage to the way that we understand language, to the point that even a seemingly simple question, like, "What makes a person a speaker of a language?" can turn out to be really, really complicated.I'm a Spanish professor at Ohio State. I teach mostly upper-level courses, where the students have taken four to five years of university-level Spanish courses. So students who are in my class speak Spanish with me all semester long. They listen to me speak in Spanish. They turn in written work in Spanish. And yet, when I asked my students at the beginning of the semester, "Who considers themselves a Spanish speaker?" not Wh very many of them raise their hands. So you can be a really, really good speaker o of a language and still not consider yourself a language speaker.Maybe it's not cou just about how well you speak a language. Maybe it's also about what age you nts start learning that language. But when we look at kids who speak Spanish at as a home but mostly English at work or in school, they often feel like they don't spe speak either language really well. They sometimes feel like they exist in a state aker of languagelessness, because they don't feel fully comfortable in Spanish at of a school, and they don't feel fully comfortable in English at home. We have this lang really strong idea that in order to be a good bilingual, we have to be two uag monolinguals in one body. But linguists know that's not really how bilingualism e? works. It's actually much more common for people to specialize, to use one language in one place and another language in another place.Now, it's not always only about how we see ourselves. It can also be about how other people see us. I do my research in Bolivia, which is a country in South America. And in Bolivia, as in the United States, there are different social groups and different ethnic categories. One of those ethnic categories is a group known as Quechua, who are Indigenous people. And people who are Quechua speak Spanish a little bit differently than your run-of-the-mill Spanish speaker. In particular, there are some sounds that sound a little bit more alike when many Quechua speakers use them.So a colleague and I designed a study where we took a series of very similar-sounding word pairs, and they were similar-sounding in exactly the same sorts of ways that Quechua speakers often sound similar when they speak Spanish. We played those similar-sounding word pairs to a group of listeners, and we told half of the listeners that they were going to listen to just your normal run-of-the-mill Spanish speaker and the other half of the listeners that they were going to hear a Quechua speaker. Everybody heard the same recording, but what we found was that people who thought they were listening to a run-of-themill Spanish speaker made clear differences between the word pairs, and people who thought they were listening to a Quechua speaker really didn't seem to make clear differences.So if a visual would help, here are the results of our study. What you see here in the top line is a little bit of an arch. That's what you would expect from people who are making clear differences between the word pairs, and that's what you see for people who though they were listening to a Spanish speaker. What you see on the bottom is a little bit more of a flat line, and that's what we expect to see when people are not making clear differences, and that came from the group that thought they were listening to a Quechua speaker. Now, since nothing about the recording changed, that means that it was the social categories that we gave the listeners that changed the way they perceived language.This isn't just some funny thing that only happens in Bolivia. Research has been carried out in the United States, in Canada, in New Zealand, showing exactly the same thing. We incorporate social categories into our understanding of language. There have even been studies carried out with American college students who listen to a university lecture. Half of the students were shown a picture of a Caucasian face as the instructor. Half of the students were shown a picture of an Asian face as the instructor. And students who saw the Asian face reported that the lecture was less clear and harder to understand, even though everybody listened to the same recording.So social categories really influence the way that we understand language. And this is an issue that became especially personal to me when my children started school. My children are Latino, and we speak Spanish at home, but they speak mostly English with their friends out in the world, with their grandparents. When they started school, I was told that the district requires that any household that has a member who speaks a language other than English, the children have to be tested to see if they need English as a second language services. And I was like, "Yes! My kids are going to ace this test."But that's not what happened. So you can see behind me the results from my daughter's ESL placement exam. She got a perfect five out of five for comprehension, for reading and listening. But she only got three out of five for speaking and writing. And I was like, "This is really weird, because this kid talks my ear off all the time."(Laughter)But I figured it's just one test on one day, and it's not a big deal. Until, several years later, my son started school, and my son also scored as a non-native speaker of English on the exam. And I was like, "This is really weird, and it doesn't seem like a coincidence." So I sent a note in to the teacher, and she was very kind. She sent me a long message explaining why he had been placed in this way. Some of the things that she said really caught my attention. For one thing, she said that even a native speaker of English might not score at advanced level on this test, depending on what kinds of resource and enrichment they were getting at home. Now, this tells me that the test wasn't doing a great job of measuring English proficiency, but it may have been measuring something like how much resources kids are exposed to at home, in which case, those kids need different types of support at school. They really don't need English language assistance.Another thing that she mentioned caught my attention as a linguist. She said that she had asked my son to repeat the sentence, "Who has Jane's pencil?" And he repeated, "Who has Jane pencil?" She said this is a typical error made by a non-native Englishspeaking student whose native language does not contain a similar structure for possessives. The reason this caught my attention is because I know that there is a systematic, rule-governed variety of English in which this possessive construction is completely grammatical. That variety is known to linguists as "African-American English." And African-American English is actually group of dialects that's spoken across the United States, mostly in African-American communities. But it just so happens that my son's school is about 60 percent African-American. And we know that at this age, children are picking things up from their friends, they're experimenting with language, they're using it in different contexts. I think when the teacher saw my son, she didn't see a child who she expected to speak African-American English. And so instead of evaluating him as a child who was natively acquiring multiple dialects of English, she evaluated him as a child whose standard English was deficient.Language and social categories are intricately connected, and we bring so much baggage to the way that we understand language. When you ask me a question like, "Who counts as a speaker of a language?" I don't really have a simple answer to that question. But what I can tell you is that people are pattern seekers, and we're always looking for ways to connect the dots between different types of information. This can be a problem when our underlying biases are projected onto language.When I look at children like my own, and I see them in the gentlest and most well-meaning of ways being racially profiled as non-native speakers of English, it makes me wonder: What's going to happen as they move from elementary school onto high school and college and onto their first jobs? When they walk into an interview, will the person sitting across the table from them look at their color or their last name and hear them as speaking with a Spanish accent or as speaking bad English? These are the kinds of judgments that can have long-reaching effects on people's lives.So I hope that that person, just like you, will have reflected on the naturalized links between language and social categories and will have questioned their assumptions about what it really means to be a speaker of a language.Thank you.(Applause) It is the third of March, 2016, and I'm anxiously waiting for my wife to deliver our firstborn son. Seconds turn into minutes, then hours, without a sign of a child coming through. Then a midwife emerges with a silent baby in her hands, and she runs past me as though I'm not even there. Why is he not crying? I'm gripped with chills in my spine as I run after her in terror. She puts the baby on a bench and begins a resuscitation procedure. Thirty minutes later, she tells me, "Don't worry, he will be fine, and thank you for staying calm." He was placed in the ICU, and though I cannot touch him, I repeatedly say, "Shine on, my son. Don't give up. I am here with you, and you don't have to be scared. Please pull through and let us go home. You do not belong here."Seven months later, he An would be diagnosed with cerebral palsy, a nonprogressive brain injury which inn primarily affects body movement and muscle coordination. About two to three ovat children out of 1,000 in the United States have cerebral palsy. I do not know the ive statistics for my country and continent, because there's not much way documentation. Maybe this could be the journey that changes everything.We to named him Lubuto, a beautiful Zambian name from my Lunda tribe of the sup Bemba-speaking people, meaning "light." By the time he was seven months, port Lubuto's physical impairment was predominant in the left part of his body. Both chil his left leg and arm were less responsive. He couldn't grasp items; worse off, dre couldn't babble his first words because the cerebral palsy shackle affects the n muscle in his lips. Rolling over and other milestones that come naturally in with typical babies, couldn't be seen in our son. Lubuto was visibly unaware of his spe own body. And some specialists started preparing us for the worst by telling us cial that we were going to be very lucky if he ever sat upright and unsupported. nee Before us was a gigantic, seemingly immovable mountain. What do we do?For ds the past 15 years, I have worked as a computer programmer, and now I'm a certified project management professional. After the denial, crying and partial depression was over, I began to wonder if we could put my programming and project management skills together to try and help the situation. Acceptance kicked in, and I searched from deep within for strength and any available knowledge to help with the challenge before us.I ordered two books online and spent countless sleepless nights researching neuroplasticity in a child's brain. My extensive research indicated that people who have strokes are able to recover through assiduous rehabilitation programs that activates new parts in the better part of their brains.This left me with one big question: If this works for grown people, why should it not work for a baby? I also learned that human beings pick up fundamental patterns mainly between ages zero to five, and after that, consolidation of habits happens. It was scary to realize that we may just have five years to figure out the immobility of Lubuto.On such a tight timeline, we needed to build a support system around him, leveraging the limited resources available to us. This was a clear project before us which needed to be carefully executed, and we needed a capable, self-driven team, an agile team."Agile" is a methodology that we use to execute projects with changing requirements to achieve progressive results in increments. We needed to deliver quick results, and in pieces, considering our work was largely dependent on Lubuto's responsiveness and capability.The first team member I acquired was my beautiful wife Abigail, who is luckily a project manager, too. You know how rough that can be, right? Two project managers under one roof.We searched around Zambia for a neonatal physiotherapist, an occupational therapist and a speech therapist. It felt like mission impossible. We set road maps of one to three months, just enough planning and just in time. We then identified features like, "We want him to stand and walk independently," under different themes like gross motor, fine motor, adaptive skills, communication, asymmetric movement and balance.Next, we created sprints to work on the stimulation of different parts of Lubuto's body. When you're working on an agile project, you do a series of lead-to tasks, collectively called "sprints," which the team reviews after execution. We, for example, set a goal to stimulate his left arm. Say occupational therapists use different textures to rub on his arm. Physiotherapists make deliberate movements in his arm to build the muscles. And self-proclaimed general therapists, who was usually myself, engage in logical stimulations like slowly moving his favorite toy from his right hand across and by in front of him to his left side to prompt movement in his left arm.And at the end of each week, we would review our results as a team: How did OT go? How did physio go? How did stimulation go? Did we meet our goal? Because frequent communication is very important on an agile project, we created a WhatsApp group for quicker updates.Failing early and picking up is a special characteristic of agility, and we leveraged that because our work is largely dependent on his response. Luckily, Lubuto is a fighter, and his determination is out of this world. After we achieved the goal of activating his arm, we then moved to his leg. The activities were totally different, but followed the similar iterative process. I would come to learn in brain plasticity that Lubuto was better off learning certain skills when he was ready, even if it meant delaying him, because he had to learn it right.While working and managing Lubuto as an agile project, a new team member popped up. Oh! It's Lubuto's sister, Yawila. We had no idea how we were going to manage the process without disturbing him while not making the sister feel neglected because we were giving the brother a lot of attention.Our daily iterations continued, and now Lubuto was able to walk on his stiff legs. With me cheerleading from the front as I walked backwards, because I needed to keep eye contact with him, I sang his favorite songs, as we oscillated between our bedroom and the kitchen.We then traveled to South Africa and introduced a neuromovement therapist to the team, coupled with hyperbaric oxygen therapy. These sprints were much shorter and focused on his brain, teaching him about his own body through small body movements. Terry did a miraculous job. Lubuto started opening his knees in unison with his hips. And in our second week, he was able to run with better balance. He started making intentional sounds to communicate with us as a result of the new neuropaths firing.We returned to Zambia with amazing results. And guess who effectively picked up the therapy? The new team member. Lubuto started mimicking the sister, and soon he was learning more things good and bad from the sister than he was learning from his team of therapists. To make sure that he stays on track, we built a unique curriculum that incorporates all the therapies with teacher Goodson.We've been blessed to have the knowledge before us and be able to practically apply it. Not all families with special needs children are as fortunate as we are. We still have backlog stories, which is a fancy agile term for pushing failure to a later date, in Lubuto's case, drooling and potty training. But in iterative, little daily activities, we managed to improve the entire left part of Lubuto's body — from the arm, to one finger to the other, from the leg to the toes. Lubuto began to roll over. He began to independently sit. He was able to crawl, stand, walk, run, and now he plays soccer with me in a more coordinated manner. This has left my wife's heart and mine melting, and we've been blown away by the unbelievable results we've witnessed as a result of this experimental methodology. And now, we proudly call ourselves "agile parents."You may be a parent with a special needs child like me, or you could be facing different types of limitation in your life: professionally, financially, academically or even physically. I want to remind you that, in striving for bigger goals, dare to take small sprints. These sprints are usually far from excellent themselves, but they add up to magnificent results.Thank you. After a long day working on the local particle accelerator, you and your friends head to the arcade to unwind. The lights go out for a second, and when they come back, there before you gleams a foosball table nobody remembers seeing before. Always game, you insert your coins. And with a fanfare, Quantum Foosball begins.Here are the rules: as with normal foosball, the object is to score points by spinning levers with tiny players to sink the ball in your opponent’s goal. Only instead of a standard ball, you’ll be playing with a giant electron. It behaves like a normal electron in all respects, it’s just much larger.Though the rules are simple, gameplay is anything but. Instead of the familiar laws of Newtonian physics, the movement of the ball is governed by quantum mechanics. To minimize the influence from photons and air molecules, you’ll be playing in a vacuum. In the dark. But that’s ok, because you can watch for the flashes of light given off by collisions between figures and the ball. The goals themselves will flash when the electron hits their particle detectors.Now you just have to figure out how to get the electron to go where you want. As soon as it enters play, the electron will never rest. This is a direct consequence of the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, which says that the better you know where a quantum particle is, the less you know about its velocity, and vice versa. Since you know it’s on the field, its velocity is largely uncertain.The electron will behave more like a wave than a particle, with its position described by probability distributions that you’ll have to imagine. These distributions are spread throughout the entire field, making it possible to observe a goal at any time and in either side. The way to win is to control and concentrate the distribution over the opposite goal, giving yourself the highest likelihood of scoring points.Your skill as a player will be determined by your ability to predict Can where the electron is most likely to be, then manipulate the probability you distribution by spinning the rods with just the right amount of strength. Quantum win particles only receive energy in precise amounts, called quanta. So spin too hard a or too soft, and the electron will stay on its previous course.The game board has gam been carefully constructed to contain the electron, but even so, sometimes it’ll e of quantum tunnel through the walls without any apparent reason. At that point it qua could be anywhere in the universe, so to save you the trouble of tracking it ntu down, the game will spit out a new ball.The fact that quantum particles behave m like waves becomes particularly evident in the presence of obstacles. As the foo particle travels through the rows of miniature figures, complicated interference sbal patterns will develop in the probability distribution, making it even more difficult l? to accurately predict its position.And here’s where your advanced physics degree can finally come in handy: you can use the laws of quantum mechanics to your advantage. The only moments when the electron will behave as a particle, rather than a wave, are when it hits something. With frequent enough kicks, the particle would have no time to evolve like a wave and, therefore, not spread out in space. So if you can pass it very quickly between two of your miniatures, you can keep it localized. Masters of the game call this the Quantum Zeno Maneuver.Now, if you really want to dominate your opponents, there’s one more thing you can try, but it’s pretty tricky. One of the distinctive features of the quantum world is the possibility of state superpositions, where particles’ positions or velocities can be simultaneously in two or more different states. If you can put the electron into a superposition of being simultaneously kicked and not kicked, it’ll be almost impossible for your opponents to figure out where and how to strike. It’s said that Erwin Schrödinger, the greatest Quantum Foosball champion of all time, is the only player to have mastered this technique. But maybe you can be the second: Just figure out a way to simultaneously turn and not turn your rods. Let me tell you a story, where you'll meet the characters who I'll call Bilal and Brenda.I was working in a most remarkable part of the world. And one unremarkable morning, a colleague came to see me. She told me that Bilal, one of our senior executives, had been telling everyone I was being removed because I'd been messing with the wrong people. And now, I was going to face the consequences.I wasn't alarmed, because I knew I had done what I'd been hired to do: my job, dealing with thorny issues head on and leaving no stone unturned. In fact, in the months prior to this, we'd overturned more than just a few stones. Those details are for another time.I called my husband, James, to tell him about this bizarre conversation, and with what proved to be great Ho foresight, he said, "Angélique, pack your things and call Brenda, in that order."I w to called Brenda. I'd worked with her for a number of years, and I trusted her. She be was the person who'd recommended me for that job. I cut to the chase, because an my husband's reaction made me realize this was more than just the usual stuff ups I'd encountered before. And I say usual, but in that moment of clarity, it dawned tan on me what James had already recognized: none of this was usual.These der irregularities, part of a pattern I'd failed to notice, were what I now know as open inst secrets living beneath those proverbial stones I'd had the audacity to overturn.To ead my shock, I learned that this was happening because I hadn't tried hard enough of a to operate in the "gray space." I didn't seem to know when to kick things into the byst long grass. And I didn't understand that this was how the system worked. The and message, the implied threat, was clear.Over the next few weeks, I was replaced er by a convenient yes-man while I was still there. I suffered from terrible gastritis, and I pretended to our two young daughters that I still had that job. Leaving home every morning, dressed up as if for work, to drop them to school, for six months.I did not submit, but I won't pretend that it was easy to speak up or beneficial in any way to me, to my family or to my career.When we speak up in the workplace despite policies to the contrary, whilst we may not lose our jobs, we are likely to lose the camaraderie of our coworkers. Disbelieved, ostracized, faced with under-the-radar bullying. You know the kind when you walk into a room and everyone stops talking? We think: It's not my responsibility to say anything.So why did I choose to act despite the risks to my family and to me? The sin of omission is a failure to do what you know is right.When you stay quiet, even though you're not guilty of wrongdoing yourself, what will you have to live with if you don't take action?So who are you in this lineup of actors? The bad actor, the wrongdoer? The bad stander who benefits directly or indirectly and acts as a puppet for the bad actor? The bystander, aware of the open secrets but not actually doing anything wrong or the upstander? This is the person we want to see when we look in the mirror.I've learned three things: One, don't second guess yourself. When you see something amiss, ask questions, because it is okay to challenge those in authority. Two, don't be complicit. You always have the power to say no in the face of wrongdoing. And three, be an upstander. Speaking up is not about being brave. It's not about not feeling scared. But when you do what you know is right, you can be at peace with yourself.Yes, it is hard to say what you feel in the moment. Do it anyway. Be fearless.Martin Luther King said, "In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends." So when you look in the mirror, who will you see? A bystander, keeper of open secrets? Or will the person looking back at you be an upstander?I know who I see. I know who my daughters see. The choice is yours. A I'm not sure what you might think when you think about the job of a police officer. stra Recent events have sparked lots of debate over the role of law enforcement in tegy our society and if it should change. And that's a big, important conversation that for we all need have. But today I'd like to talk about something that's at the core to sup my day-to-day work — something not often discussed when talking about police port work, and that's dealing with trauma, hurt and loss.What's it like to tell someone ing — someone that they know, someone that they love died suddenly? Many of you and might think this is done by hospitals or doctors. If you die there, well, it usually is. liste If you die outside the hospital, it's more often than not the police who notify that nin nearest loved one. Doing that type of work has taught me powerful lessons on g to approaching highly charged situations in all areas of my life.My passion to oth connect started about 10 years ago. I responded to a death call that changed ers me. A woman — let's call her Vicky. Vicky called because her husband had suddenly collapsed in the hallway of their home. The first responders and I tried everything. We gave it our best effort, but he died.In complete devastation, Vicky fell to the floor. Instantly, I could feel us strapping on that emotional armor, going right to work on policies and procedures. I began peppering her with questions like detailed medical history and funeral home arrangements. Questions that she couldn't possibly have been prepared to answer. In an empathetic gesture, I reached down and I put my hand on her shoulder. She flinched and pulled away. Suddenly, her neighbor came running in and instantly hugged her. Vicky pushed her away too. The neighbor seemed stunned, a little put off, and she walked back out. Then, to make matters worse, the medical examiner's office, carrying the body bag holding her husband, dropped it down a flight of stairs, crashing into a decorative end table.I will never forget the sound of her voice when she looked at me and said, "I wish I never called." I felt awful.Being confronted with death can be difficult for everyone. Often we rely solely on our instincts to help guide us. In law enforcement, we tend to put up an emotional shield, a barrier to emotions. That way we can focus on policies and procedures to guide us. This is why we can sometimes come across as robotic.I've discovered that in the civilian world, you're often driven by that instinct to fix it, usually done with wellintended comments or physical touch. Sometimes that may be that right answer. Other times, not. Had I slowed down and just taken a breath, I would have been better able to connect to the humanity of that moment. I could have avoided that policy and procedure, check-the-box mentality. Her neighbor, had she slowed down, just taken a breath, she may have been able to see that in that moment, Vicky just wasn't prepared for touch. Our hearts may have been in the right place, but we made it about us instead of focusing on her.In complete contrast, more recently, I met a woman — let's call her Monica. I was tasked to tell Monica that her husband had tragically taken his own life. She fell to the floor crying so hard she could barely breathe. The gravity of that moment was so strong, but I knew I needed to resist that urge to move in and to comfort her. That sounds crazy, right? Honestly, it's excruciating. In your mind and in your heart, you just want to hug this person. But I stopped myself.Having been around trauma for over 20 years, I will tell you not everybody is comfortable with human touch. There are people all over the world suffering from physical or psychological trauma you may know nothing about. Who knows what they're thinking or feeling in those moments. If I move in, if I touch her like I did Vicky, I could unintentionally revictimize her all over again. Think: respect space. Be guided by respect space. It's a simple concept with a huge impact. You can't step into that space until you're invited.So I sat across from Monica, silent, eye level, just feeling that moment. My heart was pounding so hard I could hear it. That lump in my throat? Ugh, I — I could barely swallow. And you know what? That's OK. Emotions and vulnerability can be so hard for some people. I understand that. But in human moments, people want human. They don't want a robotic police officer or to be talking about paperwork. They just want another human to connect to them. As we sat together, she asked me one question over and over and over again. "What am I supposed to tell my kids?" One of the most important parts of respecting space is not always having to have an answer. I could feel she didn't want me to answer that question. She didn't want me to try to fix that unfixable moment. She wanted me to connect to the depth of that experience she was going through.Yes, I had a job to do. And when the time was right, I asked the questions that needed to be answered, but I did it at her pace.Responding to death calls has taught me so much about the human experience and the best ways to be there for somebody when they need you the most. But it doesn't always have to be when dealing with death. There's never a bad time to build a connection. Hearing a private revelation from a friend, you could be such a better listener. In an argument with a loved one, by just stepping back and giving that respect space, you could better connect to their side of an issue. You may never be asked to tell a complete stranger that their loved one died, but we all have the opportunity to be the best, most connected versions of ourselves, especially in times of need. That respect space that you provide another can have a life-changing effect on the people around you.Thank you. In 2018, a single power plant produced more energy than the world’s largest Buil coal-powered and gas-powered plants combined. And rather than using finite din fossil fuels, this massively powerful plant relied on a time-tested source of g renewable energy: running water. Stretching over 2.3 kilometers, China’s Three the Gorges Dam isn’t just the world’s largest hydroelectric plant. It’s capable of worl producing more energy than any other power plant on Earth. So what allows d's Three Gorges to generate all this power? And how do hydroelectric plants work larg in the first place?A hydroelectric dam is essentially a massive gate, which est redirects a river’s natural flow through a large pipe called a penstock. Rushing (an water flows through the penstock and turns the blades of a turbine, which is d attached to a generator in an adjacent power station. The turning of the blades mos spins coils of wire inside a magnetic field, producing a steady supply of t electricity.Because the penstocks can be sealed at any time, a dam can hold con back excess water during stormy seasons, and save it for dry ones. This allows trov hydroelectric dams to produce power regardless of the weather, while ersi simultaneously preventing floods further downstream.These benefits have long al) appealed to China’s Hubei Province. Located near the basin of the Yangtze pow River, this region is prone to deadly floods during rainy seasons when the er Yangtze’s flow is strongest. Plans to build a dam that would transform this plan volatile waterway into a stable source of power circulated throughout the 20th t century. When construction finally began in 1994 the plans were epic. The dam would contain 32 turbines— 12 more than the previous record holder, South America’s Itaipu Dam. The turbines would supply energy to two separate power stations, each connecting to a series of cables spanning hundreds of kilometers. Electricity from Three Gorges would reach power grids as far away as Shanghai.However, the human costs of this ambition were steep. To create the dam’s reservoir, workers needed to flood over 600 square kilometers of land upstream. This area included 13 cities, hundreds of villages, and over 1,000 historical and archaeological sites. The construction displaced roughly 1.4 million people, and the government’s relocation programs were widely considered insufficient. Many argued against this controversial construction, but others estimated that the lives saved by the dam’s flood protection would outweigh the trauma of displacement. Furthermore, raising the water level upstream would improve the river’s navigability, increase shipping capacity, and transform the region into a collection of prosperous port towns.When the project was completed in 2012, China became the world’s largest producer of electricity. In 2018, the dam generated 101.6 billion kilowatt-hours. That’s enough electricity to power nearly 2% of China for one year; or to power New York City for almost two years. This is a truly astonishing amount of energy. And yet, two years earlier, another dam less than half the size actually generated more electricity. Despite Three Gorges record-setting scale, the Itaipu Dam still produced more power.To understand why Itaipu can outperform Three Gorges, we need to look at the two factors that determine a dam’s energy output. The first is the number of turbines. Three Gorges has the world’s highest installed turbine capacity, meaning it’s theoretically capable of producing over 50% more power than Itaipu. But the second factor is the force and frequency of water moving through those turbines. Three Gorges spans several deep, narrow ravines surging with powerful water. However, the Yangtze’s seasonal changes keep the dam from reaching its theoretical maximum output. The Itaipu Dam, on the other hand, is located atop what was previously the planet’s largest waterfall by volume. Although the dam’s construction destroyed this natural wonder, the constant flow of water allows Itaipu to consistently generate more power each year.This dam rivalry is far from over, and other projects like the Inga Falls Dam in the Democratic Republic of Congo are also vying for the title of most powerful power plant. But whatever the future holds, governments will need to ensure that a power plant’s environmental and human impact are as sustainable as the energy it produces. My first year in graduate school, studying cooperation in monkeys, I spent a lot of time outside, just watching our groups of capuchin monkeys interact. One afternoon, I was out back feeding peanuts to one of our groups, which required distracting one of our males, Ozzie, enough so that the other monkeys could get some. Ozzie loved peanuts, and he always tried to do anything he could to grab some. On that day, however, he began trying to bring other things from his enclosure to me and trade them with me in order to get a peanut.Now, capuchins are smart, so this wasn't necessarily a surprise. But what was a surprise was that some of the things that he was bringing me, I was pretty sure he liked better than peanuts. First, he brought me a piece of monkey chow, which is like dried dog food — it was even made by Purina — and for a monkey, is about as worthless as it gets. Of course, I didn't give him a peanut for that. But he kept trying, and eventually, he brought me a quarter of an orange and tried to trade it with me for a peanut. Now, oranges are a valuable monkey commodity, so this trade seemed, shall I say, a little bit nuts?Now you may be wondering how we know what monkeys prefer. Well, we ask them, by giving them a choice between two foods and seeing which one they pick. Generally speaking, their preferences are a lot like ours: the sweeter it is, the more they like it. So, much like humans prefer cupcakes to kale, monkeys prefer fruits, like oranges or grapes, to vegetables like cucumbers, and all of this to monkey chow. And peanuts are not bad. However, they definitely don't prefer them to a chunk of orange.So when Ozzie tried to trade a quarter of an orange for a peanut, it was a surprise, and I began to wonder if he suddenly wanted that peanut because Wh everybody else in his group was getting one. In case you're wondering, I did give y Ozzie his peanut.But then I went straight to my graduate adviser, Frans de Waal, mo and we began to design a study to see how the monkeys would respond when nke somebody else in their group got a better reward than they did for doing the ys same work.It was a very simple study. We took two monkeys from the same (an group and had them sit side by side, and they would do a task, which was d trading a token with me, and if they did so successfully, they got a reward. The hu catch was that one monkey always got a piece of cucumber, and the other man monkey sometimes got a piece of cucumber, but sometimes got a grape. And if s) you'll recall, grapes are much preferred to cucumbers on the capuchin monkey are hierarchy.These are two of my capuchin monkeys. Winter, on the right, is trading wire for a grape, and Lance, on the left, is trading for a cucumber. You can see that d she — and yes, Lance is actually a female — is at first perfectly happy with her for cucumber, until she sees Winter trading for a grape. Suddenly, Lance is very fair enthusiastic about trading. She gets her cucumber, takes a bite and then — nes throws it right back out again. Meanwhile, Winter trades again and gets another s grape and has Lance's undivided attention while she eats it. This time, Lance is not so enthusiastic about trading. But eventually, she does so. But when she gets the cucumber this time around, she doesn't even take a bite before she throws it back out again. Apparently, Lance only wants a cucumber when she hasn't just watched Winter eat a grape. And Lance was not alone in this.All of my capuchins were perfectly happy with their cucumbers as long as the other monkeys were getting cucumbers too. But they often weren't so happy with their cucumbers when other monkeys were getting a grape. The obvious question is why? If they liked those cucumbers before, what changed?Now, I'm a scientist, and scientists are famously shy about reading too much into our studies, especially when it comes to what other animals are thinking or feeling, because we can't ask them. But still, what I was seeing in my monkeys looked an awful lot like what we humans would call a sense of fairness. After all, the difference in that cucumber was that it came after Winter got a grape, rather than before.We humans are obsessed with fairness. I have a younger sister, and when we were little, if my sister got a bigger piece of the pie than me, even by a crumb, I was furious. It wasn't fair. And the childhood me is not alone.We humans hate getting less than another so much that one study found that if humans were given a hypothetical choice between earning 50,000 dollars a year while others earned 25,000 dollars, or earning 100,000 dollars a year while others earned 250,000 dollars, nearly half the subjects prefer to earn 50,000 dollars a year less money to avoid earning relatively less than someone else. That's a pretty big price to pay.What drives people to this sort of apparently irrational decision-making? After all, throwing away your cucumber because someone else got a grape only makes sense if it makes things more fair. Otherwise, Winter has a grape, and you have nothing. Of course humans are not capuchin monkeys. But on the surface, sacrificing 50,000 dollars because somebody else is going to earn more money than you makes no more sense than throwing away that cucumber. Except maybe it does.Some economists think that the sense of fairness in humans is tied to cooperation. In other words, we need that sense of fairness when we're working with somebody else to know when we're getting the short end of the stick. Think about it this way. Let's say you have a colleague at work who's having a hard time and needs a little extra help. You're probably more than happy to help out, especially if she does the same for you when you need it. In other words, if things even out. But now, let's say that colleague is always slacking off and dumping extra work on you. That's infuriating. Or worse, what if you're doing all the work, and she's getting paid more. You're outraged, right? As well you should be. That righteous fury is your sense of fairness telling you that, well, it's not fair. You need to get your fair share from the people you're working with, or it's exploitation, not cooperation.You may not be able to leave every job where you're treated unfairly, but in a perfect world, one without racism and sexism and the frictions associated with finding a new job, it's your sense of fairness that would let you know when it was time to move on. And if you couldn't? Well, that smoldering frustration might make you throw your cucumbers too.And humans are not alone in this. In the previous study, there was nothing Lance could do about it, but what if there had been? It turns out that capuchins simply refuse to cooperate with other capuchins who don't give them their share after they worked together. And refusing to work together with another monkey is a pretty straightforward way of leveling the playing field. Apparently, no monkey getting anything at all is better than another monkey getting more. But much like you and your coworker, they're perfectly happy with a little short-term inequality as long as everything evens out over the long run.This economic connection between fairness and cooperation makes sense to me as an evolutionary biologist. After all, your ancestors didn't get to pass on their genes because they did well in some absolute sense, but because they did better than others. We don't call it survival of the fit, we call it survival of the fittest. As in more fit than others. It's all relative.OK. So my capuchins don't like it when they get less than another. And they're perfectly happy to sacrifice their cucumbers to level the playing field. That's great. But what we would call a sense of fairness in humans also means that we care when we get more than someone else. What about my monkeys? It turns out that primates do notice when they get more than others, or at least some of them do. My capuchins do not. But in one of my studies, my chimpanzees would sometimes refuse a grape if another chimpanzee in their group got a cucumber, which is pretty impressive, given how much my chimpanzees like grapes. However, they were still more upset when they got less than another chimp as compared to when they got more. You may not think it's fair when you have more than your neighbor, but you really don't think it's fair when your neighbor has more than you.Here's an important question, though. Why do we care about inequality or unfairness when we are the ones who are unfairly benefiting? If evolution is about survival of the fittest, wouldn't it make sense to grab any advantage you can get? Here's the thing though. I do better if I get more than you, sure. But best of all is if you and I can work together and get more than either one of us could have gotten on our own. But why would you work with me if you don't think I'm going to play fair? But if you think I'm going to notice when I've got more than you and do something about it, then you will work with me.Evolution has selected us to accept the occasional short-term loss in order to maintain these all-important long-term relationships. This is true in chimpanzees, but it is even more important in humans. Humans are incredibly interconnected and interdependent, and we have the advanced cognitive abilities to be able to plan far into the future. And to recognize the importance of maintaining these cooperative partnerships. Indeed, if anything, I think we are likely underplaying how important the sense of fairness is for people.One of the biggest differences between humans and capuchin monkeys is the sheer magnitude and ubiquity of cooperation in humans. In other words, we're a lot more cooperative than capuchin monkeys are. Legal and economic systems literally only exist if we all agree to participate in them. And if people feel left out of the rewards and benefits of those systems, then they stop participating, and the whole system falls apart.Many of the protests and uprisings we're seeing, both in the US and around the globe, are explicitly framed in terms of fairness, which is not surprising to me. Whether it's about disproportionate access to resources, or that some groups are being disproportionately impacted by the legal system or the effects of a virus, these protests are the logical outcome of our long evolutionary tendency to reject unfairness combined with our long history of social stratification. And the systemic inequalities that have resulted from that stratification. Layer on top of this the fact that by many measures economic inequality is skyrocketing.Chris Boehm wrote a book called "Hierarchy in the Forest," in which he argued that humans have reverse hierarchies in which those at the bottom band together to keep those at the top from taking advantage of them. Perhaps these protests are simply the latest manifestation of humans' tendency to rebalance the hierarchy. Perhaps the biggest difference between us and capuchin monkeys is that we can recognize this problem and actively work to do something about it. Of course we recognize when we're disadvantaged. But we can and we must also recognize when we're advantaged at the expense of someone else, and recognize fairness as the balance between these two inequalities, because our society literally depends upon it.Indeed, my research shows that not all primate species care about inequality. It's only those that rely on cooperation, which most definitely includes humans. We evolved to care about fairness because we rely on each other for our cooperative society. And the more unfair the world gets, and the less we care about each other, the more peril we will face. Our issues are more complex than grapes and cucumbers, but as the capuchins have taught us, we will all do better when we all play fair.Thank you. Ho Have you ever seen something and you wish you could have said something but w you didn't? A second question I have is: Has something ever happened to you crea and you never said anything about it, though you should have?I'm interested in tive this idea of action, of the difference between seeing something, which is writi basically passively observing, and the actual act of bearing witness. Bearing ng witness means writing down something you have seen, something you have can heard, something you have experienced. The most important part of bearing help witness is writing it down, it's recording. Writing it down captures the memory. you Writing it down acknowledges its existence.One of the biggest examples we thro have in history of someone bearing witness is Anne Frank's diary. She simply ugh wrote down what was happening to her and her family about her confinement, life' and in doing so, we have a very intimate record of this family during one of the s worst periods of our world's history. And I want to talk to you today about how to har use creative writing to bear witness. And I'm going to walk you through an dest exercise, which I'm going to do myself, that I actually do with a lot of my mo collegiate students. These are you future engineers, technicians, plumbers — men basically, they're not creative writers, they don't plan on becoming creative ts writers. But we use these exercises to kind of un-silence things we've been keeping silent. It's a way to unburden ourselves. And it's three simple steps.So step one is to brainstorm and write it down. And what I have my students do is I give them a prompt, and the prompt is "the time when." And I want them to fill in that prompt with times they might have experienced something, heard something or seen something, or seen something and they could have intervened, but they didn't. And I have them write it down as quickly as possible. So I'll give you an example of some of the things I would write down.The time when, a few months after 9/11, and two boys dared themselves to touch me, and they did. The time when my sister and I were walking in a city, and a guy spat at us and called us terrorists. The time way back when when I went to a very odd middle school, and girls a couple years older than me were being married off to men nearly double their age. The time when a friend pulled a gun on me. The time when I went to a going-away luncheon for a coworker, and a big boss questioned my lineage for 45 minutes. And there are times when I have seen something and I haven't intervened. For example, the time when I was on a train and I witnessed a father beating his toddler son, and I didn't do anything. Or the many times I've walked by someone who was homeless and in need, they've asked me for money, and I've walked around them, and I did not acknowledge their humanity. And the list could go on and on, but you want to think of times when something might have happened sexually, times when you've been keeping things repressed, and times with our families, because (In a hushed voice) God bless them.(Laughter)Our families, we love them, but at the same time, we don't talk about things. So we may not talk about the family member who has been using drugs or abusing alcohol. We don't talk about the family member who might have severe mental illness. We'll say something like, "Oh, they've always been that way," and we hope that in not talking about it, in not acknowledging it, we can act like it doesn't exist, that it'll somehow fix itself.So the goal is to get at least 10 things, and once you have 10 things, you've actually done part 1, which is bear witness. You have un-silenced something that you have been keeping silent. And so after this, you're ready for step 2, which is to narrow it down and focus. And what I suggest is going back to that list of 10 and picking three things that are really tugging at you, three things you feel strongly. It doesn't have to be the most dramatic things, but it's things that are like, "Ah," like, "I have to write about this." And I suggest you sit down at a table with a pen and paper — that's my preferred method for recording, but you can also use a tablet, an iPad, a computer, but something that lets you write it down. And I suggest taking 30 minutes of uninterrupted time, meaning that you cut your phone off, put it on airplane mode, no email, and if you have a family, if you have children, give yourself 20 minutes, five minutes. The goal is just to give yourself time to write. What you're going to write is you're going to focus on three things. You're going to focus on the details, you're going to focus on the order of events, and you're going to focus on how it made you feel. That is the most important part. I am the guinea pig today, and so I'm going to walk you through how I do it. I'm going to pick three things.So the first thing I feel very, very strongly about is that time a couple months after 9/11 when those two boys dared themselves to touch me. I remember I was in a rural mall in North Carolina, and I was walking, just walking, minding my business, and I felt people walking behind me, like, very, very close, and I'm like, "OK, that's kind of weird. Let me walk a little bit faster. There's a whole mall around me. What is happening?" They walk a little bit faster, and I hear them going back and forth: "You do it!" "No, you do it!" And then one of them pushes me, and I almost fall to the ground. So I kind of pop back up, expecting some type of apology, and the weirdest thing is that they did not run away. They actually went and just stood right next to me. And I remember there was a guy with blond hair, and he had a bright red polo shirt, and he was telling the other guy, like, "Give me my money. I did it, man." And the guy with the brown hair, I remember he had a choppy haircut, and he gave him a five-dollar bill, and I remember it was crumpled. And so I'm like, am I still standing here? This thing just happened. What just happened? And it was so weird to be the end of someone's dare, and also at the end to not exist to them. I remember it kind of reminded me of the time when I was younger and someone dared me to touch something nasty or disgusting. I felt like that nasty and disgusting thing.A second thing I feel very, very strongly about is the time a friend pulled a gun on me. I should say former friend.(Laughter)I remember it was a group of us outside, and he had ran up and he had the stereotypical brown paper bag in his hand, and I knew what it was, and so I'm a very mouthy person, and I started going off. I was like, "What are you doing with a gun? You're not going to shoot anyone. You're a coward, you don't even know how to use it." And I kept going on and on and on, and he got angrier and angrier and angrier. And he pulled the gun out and put it in my face. I remember every one of us got very, very quiet. I remember the tightness of his face. I remember the barrel of the gun. And I felt like — and I'm pretty sure everyone around me who got quiet felt like — "This is the moment I die."And the third thing I feel very, very strongly about is this going-away luncheon and this big boss. I remember I was running late, and I'm always late. It's just a thing that happens with me. I'm just always late. I was running late, and the whole table was filled except for this seat next to him. I didn't know him that well, had seen him around the office. I didn't know why the seat was empty. I found out later on. And so I sat down at the table, and before he even asked me my name, the first thing he said was, "What's going on with all of this?" And I'm like, do I have something on my face? What's happening? I don't know. And he asked me with two hands this time. "What's going on with all of this?" And I realized he's talking about my hijab. And in my head, I said, "Oh, not today." But he's a big boss, he's like my boss's boss's boss, and so I put up for 45 minutes, I put up with him asking me where I was from, where my parents were from, my grandparents. He asked me where I went to school at, where I did my internships at. He asked me who interviewed me for that job. And for 45 minutes, I tried to be very, very, very, very, very polite, tried to answer his questions. But I remember I was kind of making eyeball help signals at the people around the table, like, "Someone say something. Intervene." And it was a rectangular table, so there were people on both sides of us, and no one said anything, even people who might be in a position, bosses, no one said anything. And I remember I felt so alone. I remember I felt like I didn't deserve to be in his space, and I remember I wanted to quit.So these are my three things. And you'll have your list of three things. And once you have these three things and you have the details and you have the order of events and you have how it made you feel, you're ready to actually use creative writing to bear witness.And that takes us to step 3, which is to pick one and to tell your story. You don't have to write a memoir. You don't have to be a creative writer. I know sometimes storytelling can be daunting for some people, but we are human. We are natural storytellers, so if someone asks us how our day is going, we have a beginning, a middle and an end. That is a narrative. Our memory exists and subsists through the act of storytelling, and you just have to find a form that works for you. You can write a letter to your younger self. You can write a story to your younger self. You can write a story to your five-year-old child, depending on the story. You can write a parody, a song, a song that's a parody. You can write a play. You can write a nursery rhyme. I've read — I mean, these a theories, though — that "Baa, baa black sheep, Have you any wool," "Yes sir, yes sir, three bags full," is actually about impoverished farmers in England being taxed heavily. You can write it in the form of a Wikipedia article.And if it's one of those situations where you saw something and you didn't intervene, perhaps write it from that person's perspective. You know, so if I go back to that boy on the train who I saw being beaten, what was it like to be in his shoes? What was it like to see all these people who watched it happen and did nothing? What happens if I put myself in a position of someone who was homeless and just try to figure out how they got there in the first place? Perhaps it would help me change some of my actions. Perhaps it would help me be more proactive about certain things.And with telling your story, you're keeping it alive. So you don't have to show anyone any of these steps. But even if you're telling it to yourself, you're saying, "This thing happened. This weird thing did happen. It's not in my head. It actually happened." And by doing that, maybe you'll take a little bit of power back that has been taken away.And so the last thing I want to do today is I'm going to tell you my story. And the one I picked is about this big boss. And I picked that one because I feel like I'm not the only one who has been in the position where someone has been above me and kind of talked down. I feel like all of us might have been in positions where we felt like we could not say anything because this person has our livelihood, our paychecks, in their hands, or times we might have seen someone who has power talking down to someone, and we should have or could have intervened. And so, by telling a story, I'm taking back a little bit of power that was taken away from me. And I have changed the names, and it's been a decade, so it's going to be OK. And it doesn't have a happy ending, because it's just me writing down what happened that day. And so this is how I use creative writing to bear witness.At Lisa's goingaway luncheon, I wanted to ask my boss's boss's boss if he's stupid or just plain dumb after he takes one look at my hijab and asks me where I'm from in Southeast Asia. I tell him that it's New Jersey, actually. He asks where my parents are from and my grandparents and my great-grandparents and their parents and their parents' parents, as if searching for some other blood, as if searching for some reason why some Black Muslim girl from Newark wound up seated next to him at this restaurant of tablecloths and laminated menus. I want to say, "Slavery, jerk," but I've got a car note and rent and insurances and insurances and insurances and credit cards and credit debt and a loan and a bad tooth and a penchant for sushi, so I drop the "jerk" but keep the truth. "Tell me," he says, "Why don't Sunnis and Shiites get along?" "Tell me," he says, "What's going on in Iraq?" "Tell me," he says, "What's up with Saudi and Syria and Iran?" "Tell me," he says, "Why do Muslims like bombs?" I want to shove an M1 up his behind and confetti that pasty flesh and that tailored suit. Instead, I'm sipping my sweetened iced tea looking around at the table, at the coworkers around me, none of whom, not one, looks back at me. Rather, they do the most American things they can do. They praise their Lord, they stuff their faces and pretend they don't hear him and pretend they don't see me.Thank you. You’ve come a long way to compete in the great Diskymon league and prove yourself a Diskymon master. Now that you’ve made it to the finals, you’re up against some tough competition. As you enter the arena, the referee explains the rules.There are three Diskydisks you can use. Disk A will always summon a level 3 Burgersaur. Disk B summons a Churrozard that has a 56% chance of being level 2, a 22% chance of being level 4, and a 22% chance of being level 6. Disk C will summon a level 5 Wartortilla 49% of the time, and a level 1 Wartortilla 51% of the time. All Diskymon fully heal between battles, and the higher level Diskymon always wins, no matter what type it is.In round one, you’ll face a single opponent and get to choose your disk before she picks from the remaining two. Which one gives you the best chance of winning?Pause here to figure it out yourselfAnswer in 3Answer in 2Answer in 1Before you start calculating probabilities, take a look at the disks themselves. Disks B and C each have a more than 50% chance of summoning a level 2 or a level 1 Diskymon, respectively. This means that disk A’s guaranteed level 3 Burgersaur will always have better than even odds of winning. If you choose B or C, your opponent could pick A and gain an advantage over you. And C fares worst of all, being more than 50% likely to lose to any opponent.So you choose A, hoping for the best, and sure enough, your level 3 Burgersaur triumphs over the level 2 Churrozard. Now it’s time for round two, and while you’ve prepared for trouble, you didn’t anticipate they’d make it double. You get to choose any one of the three disks again, but this time, you’ll be in a battle royale against two opponents, each using one of the other disks. Whoever summons the highest level Diskymon wins. Should you stick with A, or switch?Pause now to figure it out yourselfAnswer in 3Answer in 2Answer in 1For many Diskymon trainers, it seems intuitive that if A is the best at beating B or C, it should also be the best at Can beating B and C. Strangely enough, that couldn’t be further from the truth. Let’s you calculate the odds. For A to win, B has to summon a level 2 Diskymon, and C solv has to summon a level 1. Those are independent events, so their odds are 56% e times 51%, or 29%. For disk B, a level 2 Churrozard would automatically lose to the the Burgersaur. But you’d have two ways to win. The 22% chance of summoning mo a level 6 would give you an outright win, while a level 4 could still win if C nste summons a level 1. Adding up those mutually exclusive possibilities gives you r odds of about 33%. Finally, C will win with a level 5 Wartortilla as long as B duel doesn’t summon its level 6, giving C a 38% chance overall. So while disk A’s ridd middling consistency was an advantage in a single matchup, multiple fights le? increase the odds that one of the other disks will summon something better. And although C was the worst first-round option, its decent chance of summoning a strong level 5 gives it an advantage when facing two opponents simultaneously. This sort of counterintuitive result is why misleading statistics are a favored tool of unscrupulous politicians and nefarious Diskymon trainers alike.Fortunately, your Wartortilla comes out level 5 and makes short work of its foes. You’re about to celebrate when your rivals capture the referee and announce a surprise third round. You’ll have to repeat each of the previous matches in succession, with all the same rules except for one: you must keep the same disk throughout. Which should you choose to give yourself the best chance at becoming that which no one ever was? (Southern Tutchone and Tlingit)Hello, my name is Kluane Adamek, and I am from the Dakl'aweidi Killer Whale clan. My Tlingit name is Aagé, and it's so important to acknowledge (Traditional language), our grandparents. I'm joining you from the traditional territory of the Kwanlin Dün and Ta'an First Nations in the Yukon territory. (Traditional language) Thank you. (English) Thank you.I shared a little bit about myself in my traditional languages of Southern Tutchone and Tlingit. I continue to learn who we are as Yukon First Nations people. We are a people that deeply value, honor and respect the roles of women. We always have. We're a matrilineal culture. And so, traditionally, our matriarchs would often guide and direct the speakers of the people, otherwise known as the chiefs. This important role of forging trade relationships, forging marriage alliances and ensuring that all of the business that needed to take place in the community was happening was all guided and directed by our matriarchs.I definitely continue to see the ways in which we lead here in the Yukon not quite The being aligned nationally. What do I mean by that? Well, to be clear, misogyny lega and patriarchy are definitely not reflective of who we are as Yukon First Nations cy or of the traditional structures and the ways in which we respect women in of decision-making.And so I saw these gaps and felt we need to have more women mat at the table. We need to have different generations at the table. And so, this is riar where I had to get a bit vulnerable. I had to really look to myself to say, "If not chs me, then who?"And so I submitted my name to become the Yukon Regional in Chief, knowing that I come from a strong people that continues to value and the uphold women, and knowing that the voice that I would bring would be a voice Yuk that will be supported by my region. But furthermore, knowing that in every and on any place where decisions are being made for women, or those who identify, Firs how important it is that women are in every place and space to be part of those t decisions.And so I gave myself permission to put my name forward and to know Nati that yes, I can serve; that yes, this was the best way for me to take action and to ons know that my voice needed to be heard in the same way that other male voices were heard from across this country.There aren't any prerequisites to being a leader. It's not about having a title or being in a specific role. Leadership is about showing up who you are, as you are, being authentic, leading from a place of values and principles, and leading from that place, and staying true to yourself.And so some might say, "Well, you're in an elected position. What do you mean?" Yes, I hear you. There's some irony in that. But let me explain. Contribution is the most important thing. For me, joining an executive of predominantly men, creating a space in my office where other indigenous women could learn and lead, it was all about creating that space, and by celebrating and acknowledging and contributing.There's a story that dates back to over 10,000 years ago. And the way that the story was shared with me is this: The Killer Whale people, the Dakl'aweidi, came to this insurmountable, huge glacier. They were traveling to make it back to their traditional homelands. And so they came to this glacier and they didn't know where they were going to go. Were they going to try to climb and go above? Were they going to try to follow it and see how far long it went? It was the matriarchs that said, "We'll go. We see a small opening there, and so we're going to go, and we're going to try to go through it." They didn't know if they would survive. They didn't know if they'd make it through. But they were fearless. And that is who we are.We are fearless because we understand the power of reciprocity. We understand that it's important to leave things in a better state and place than when we found them. We understand that the importance of connecting to the land and expressing gratitude is truly what grounds us and gives us the power and the abilities we have to lead.Think of when you're walking by the water, for example. Take a moment of gratitude to thank the water for all that it gives you, to thank the land for giving you everything you need. It's always about making sure that you're leaving things in a better place and space than when you found them. It's about contribution.All of us as women have been through so much. And so this is about us finding ways to be supportive of each other. It's about always making sure that we're making that contribution and investment in the future generations. That is about reciprocity.There's so much that we can share with the world and that the world can learn from us as women. These are the challenges that we have for this future generation, and these are the challenges that we need to accept together. We need to give ourselves the permission to step into our own power. We need to give ourselves the permission to connect and to express gratitude to the land. And we need to give ourselves the permission to take care of ourselves, because if we're not being taken care of, then how are we going to contribute to everybody else?Gunalchéesh. Thank you. This is Goliath, the krill. Don’t get too attached. Today this 1 centimeter crustacean will share the same fate as 40 million of his closest friends: a life sentence in the belly of the largest blue whale in the world. Let’s call her Leviatha. Leviatha weighs something like 150 metric tons, and she’s the largest animal in the world. But she’s not even close to being the largest organism by weight, which is estimated to equal about 40 Leviatha’s. So where is this behemoth?Here, in Utah. Sorry, that’s too close. Here. This is Pando, whose name means “I spread out.” Pando, a quaking aspen, has roughly 47,000 genetically identical clone trunks. Those all grow from one enormous root system, which is why scientists consider Pando a single organism. Pando is the clear winner of world’s largest organism by weight— an incredible 6 million kilograms.So how did Pando get to be so huge? Pando is not an unusual aspen from a genetic standpoint. Rather, Pando’s size boils down to three main factors: its age, its location, and aspens’ remarkable evolutionary adaptation of selfcloning.So first, Pando is incredibly expansive because it’s incredibly old. How old exactly? No one knows. Dendrochronologist estimates range from 80,000 to 1 million years. The problem is, there’s no simple way to gauge Pando’s age. Counting the rings of a single trunk will only account for up to 200 years or so, as Pando is in a constant cycle of growth, death, and renewal. On average, each individual tree lives 130 years, before falling and being replaced by new ones.Second: location. During the last ice age, which ended about 12,000 years ago, glaciers covered much of the North American climate friendly to aspens. So if there were other comparably sized clonal colonies, they may have perished then. Meanwhile, Pando’s corner of Utah remained glacier-free. The soil there is rich in nutrients that Pando continuously replenishes; as it drops leaves and trunks, the nutrients return to nourish new generations of clones.Which brings us to the third cause of Pando’s size: cloning. Aspens are capable of both sexual reproduction— which produces a new organism— and asexual reproduction— which creates a clone. They tend to reproduce sexually when conditions are unfavorable and the best strategy for survival is to move elsewhere. Trees aren’t particularly mobile, but their seeds are. Like the rest of us, sexual reproduction is how Pando came into the world in the first place all those tens or hundreds of The thousands of years ago. The wind or a pollinator carried pollen from the flower of worl one of its parents to the other, where a sperm cell fertilized an egg. That flower d's produced fruit, which split open, releasing hundreds of tiny, light seeds. The wind larg carried one to a wet spot of land in what is now Utah, where it took root and est germinated into Pando’s first stem.A couple of years later, Pando grew mature org enough to reproduce asexually. Asexual reproduction, or cloning, tends to anis happen when the environment is favorable to growth. Aspens have long roots m that burrow through the soil. These can sprout shoots that grow up into new trunks. And while Pando grew and spread out, so did our ancestors. As Huntergatherers who made cave paintings, survived an ice age, found their way to North America, built civilizations in Egypt and Mesopotamia, fought wars, domesticated animals, fought wars, formed nations, built machines, and invented the internet, and always newer ways to fight wars.Pando has survived many millennia of changing climates and encroaching ice. But it may not survive us. New stems are growing to maturity much more slowly than they need to in order to replace the trunks that fall. Scientists have identified two main reasons for this. The first is that we’ve deprived Pando of fire. When a fire clears a patch of forest, Aspen roots survive, and send shoots bursting up out of the ground by the tens of thousands. And secondly, grazers like herds of cattle and mule deer— whose natural predators we’ve hunted to the point of local elimination— are eating Pando’s fresh growth.If we lose the world’s largest organism, we’ll lose a scientific treasure trove. Because Pando’s trunks are genetically identical, they can serve as a controlled setting for studies on everything from the tree microbiome to the influence of climate on tree growth rates.The good news is, we have a chance to save Pando, by reducing livestock grazing in the area and further protecting the vulnerable young saplings. And the time to act is today. Because as with so many other marvels of our natural world, once they’re gone it will be a very, very long time before they return. The We are at the end of globalization. We've taken globalization for granted, and as end it drifts into history, we're going to miss it.The second wave of globalization of began in the early '90s, and it delivered a great deal. Billions of people rose out glo of poverty. More impressively, wealth per adult in countries like Vietnam and bali Bangladesh increased by over six times in the last 20 years. The number of zati democracies rose, and countries as diverse as Chile, Malaysia, Estonia, held on free and fair elections. The role of women improved in many parts of the world, if (an you look at wage equality in countries like Spain, or access to education in d countries like Saudi Arabia. Economically, supply chains spread like webs the around the world, with car parts criss-crossing borders before the final product begi came into place. And globalization has also changed the way we live now. It's nni changed our diets. It's changed how we communicate, how we consume news ng and entertainment, how we travel and how we work.But now, globalization is on of its deathbed. It's run into the limitations of its own success: inequality and new, som record levels of indebtedness — for example, world debt-to-GDP is now pushing ethi levels not seen since the Napoleonic Wars 200 years ago — show us that the ng advantages of globalization have been misdirected. The Global Financial Crisis new was the result of this mismanagement, and since then policymakers have done ) little but contain, rather than solve, the problems of our age.Now, some highly globalized countries such as Ireland and the Netherlands, have managed to improve income inequality in their countries by better distributing the bounties of globalization through higher taxes and social welfare programs. Other countries have not been as good. Russia and, especially, the United States, have extreme levels of wealth inequality, more extreme even than during the time of the Roman Empire. And this has convinced many people that globalization is against them, and that the bounties of globalization have not been shared with the many.And now, in 2020, we're confronted by the pandemic, which has shaken the ground under us and further exposed the frailties of the globalized world order. In past international crises, most of them economic or geopolitical, there has usually ultimately been a sense of a committee to save the world. Leaders and leading nations would come together. But this time, uniquely, there has been no such collaboration. Against a backdrop of trade wars, some countries like the US have outbid others for masks. There's been hacking of vaccine programs, and a common enemy, the pandemic, has not been met with a common response. So any hope that we might have a world vaccine or a world recovery program is in vain.So now we're at the end of an era in history, an era that began with the fall of communism, that set in train the flow of trade, of finance, of people and of ideas, and that now comes to an end with events like the shutting down of democracy in Hong Kong.The question now is, what's next? Well, if the era we're leaving was characterized by a connected world trying to shrink and come together on the basis of economic goals and geography, the new world order will be defined by rival, distinct and different ways of doing things, and ultimately collaboration based on values, and this new world order is very much a work in progress. "Disorder" might be a better word, and it has been for some time. But think appropriately of great sheets of ice breaking apart, some drifting away and others later reforming.And the internet is a bit like this. It used to be global. Google used to have 30 percent of the market share in China, and now it has close to zero percent. And the big regions of the world increasingly look at the internet from a values-based point of view. America values tech innovation and its financial rewards. China takes a political view of the internet and cordons it off, and at the same time China has this incredible e-commerce economy that no other country has come close to matching. And then there's Europe, and in Europe a conversation about the internet is effectively a conversation about data and privacy. So there you have it: one common problem, and three increasingly different, competing views.This shows us that rival ideologies will drive very distinct ways of doing things. But what about collaboration and cooperation? Well, I'm going to start with the example of three small countries: Scotland, Iceland and New Zealand. And a couple of years ago, they signed up to the Wellbeing Economy Governments, whose aim is to foster ecological and human well-being as well as economic growth. Practically speaking, these countries are already discussing things like well-being budgeting, well-being-led tourism, and using the well-being framework in the fight against COVID. Now, these three countries are about as geographically distant and diverse as you can get, but they've come together on the basis of a shared value, which is a common understanding that there is more to government policy than merely GDP.Similarly, in the future, other small countries and city-states — Singapore, Switzerland, the United Arab Emirates — will find that they have more in common with each other than with their larger neighbors. They're all global financial centers. They all invest in strategic planning. And they are all geopolitical micropowers and will collaborate more as a result.Another good example of how values, rather than geography, will increasingly shape destinies and alliances is Europe. During the period of globalization, one of the key phenomena was the eastward expansion of the European Union. From 2004, it added 13 new members, despite the near existential crisis of the euro, constant pressure from Russia, and of course the trauma of Brexit. And, like a company that has grown too fast, Europe needs to stop and think about where it's going and ask whether its values can steer it in the right direction. And this is beginning to happen, albeit slowly. European leaders talk a lot about European values, but frankly most Europeans, be they German, Greek, Latvian or Spaniards, really don't know or have a clear idea what those shared common values are supposed to be. So European politicians need to do a very good job of asking them how they feel about these common values and then communicating the answers back to them in a clear and tangible way. And of course social media is a very important tool to deploy here.And as Europe moves [towards] a union that's based more on values and less on geography, its contours and those values themselves will increasingly be defined by the tension between Brussels and countries like Hungary and Poland, who are increasingly behaving in ways that go against basic values such as respect for democracy and the rule of law. The treatment of women and the LGBT community are other important markers here. And in time Europe will, and should, tie financial aid to these countries and policy to their adherence to Europe's shared values. And these countries, and others in Eastern Europe, and Cyprus, still have close financial ties to Russia and China. And again in time they will be forced to choose between Europe and its values and these other countries and their own distinct values.Like Europe, China is another big player with a very distinct set of values, or contract between the people and the state. And I have to say that this set of values is not one that is well-understood in the West. And given China's extraordinary economic and social transformation in the last 30 years, we should really be more curious. China's values are rooted deep in its history, in a desire to regain the place it once enjoyed hundreds of years ago when its economy was the dominant one. Indeed, Xi Jinping talked of the China Dream well before Donald Trump was elected with the catchphrase "Make America Great Again." And China's system, viewed from the outside, is based around a contract or a bargain where people will sacrifice their liberty in return for order, prosperity and national prestige. It's one where the state is very much in control, which is something that most Europeans and Americans would find alien. It's also a system that has worked very well for China. But the biggest risk it faces is a period of high and prolonged unemployment that will break this contract between the state and the people.And for other countries, China can be an attractive partner. It can provide capital and know-how. I'm thinking for example of Pakistan and Sri Lanka, two members of the Belt and Road program. But this partnership comes at a price; they're beholden to Chinese technologies such as the controversial Huawei. Chinese investors own their debt, and as a result control key infrastructure such as the main port in Sri Lanka.Now I find that when we talk about globalization, the end of globalization and the new world order, we spend far too much time discussing America, Europe and China, and not enough time on the many exciting things happening in fast-growing economies, from Ethiopia, Nigeria, to Indonesia, Bangladesh, Mexico and Brazil. And in the new world order, the question for these countries is what model to follow and what alliances to build. And many of them during the period of globalization had become used to being told what to do by the likes of the IMF, the International Monetary Fund. But the age of condescension is now over, so the tangible opportunity in a less uniform, more value-driven world for these countries is that they have much greater choice in the path to follow, and arguably greater pressure to get it right.So should, for example, Belarus and Lebanon follow the Irish model or that of Dubai? Does Nigeria still think it has shared values with the Commonwealth countries, or will it ally itself and its fastgrowing population to China and its model? And then think of one of the few female leaders in Africa, President Sahle-Work Zewde of Ethiopia, and whether she might be inspired by the work of Jacinda Ardern in New Zealand or Nicola Sturgeon in Scotland, and tangibly how she can transfer their example to policy in Ethiopia. Of course, it may be that in this new world order, countries like Kenya and Indonesia decide to go their own way and build out their own value sets and their own economic infrastructure, and in this way the arrangements and the institutions of the future will be crafted much less in Washington and Beijing, but really by countries like Tunisia and Cambodia, comparing notes on how to battle corruption through technology, how to build education and health care systems for burgeoning populations, and how to make their voice heard on the world stage.So as globalization ends and chaos seems to reign, these countries, their young populations and the scope they have to build new societies are the future and the promise of the new world order.Thank you. So here's a thought. The fossil fuel industry knows how to stop causing global warming, but they're waiting for somebody else to pay, and no one is calling them out on it.I was one of the authors of the 2018 IPCC report on 1.5 degrees Celsius. And after the report was published, I gave a lot of talks, including one to a meeting of young engineers of one of the world's major oil and gas companies. And at the end of the talk, I got the inevitable question, "Do you personally believe there's any chance of us limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees?"IPCC reports are not really about personal opinions, so I turned the question around and said, "Well, if you had to fully decarbonize your product, that is, dispose safely and permanently of one ton of carbon dioxide for every ton generated by the oil and gas you sell, by 2050, which is what it would take, would you be able to do so?" "Would the same rules apply to everybody?" somebody asked, meaning, of course, their competition. I said, "OK, yeah, maybe they would." Now, the management just looked at their shoes; they didn't want to answer the Fos question. But the young engineers just shrugged and said, "Yes, of course we sil would, like it's even a question."So I want to talk to you about what those young fuel engineers know how to do: decarbonize fossil fuels. Not decarbonize the com economy, or even decarbonize their own company, but decarbonize the fuels pani themselves, and this matters because it turns out to be essential to stopping es global warming. At a global level, climate change turns out to be surprisingly kno simple: To stop global warming we need to stop dumping carbon dioxide into the w atmosphere. And since about 85 percent of the carbon dioxide we currently emit how comes from fossil fuels and industry, we need to stop fossil fuels from causing to further global warming. So how do we do that?Well, it turns out there's really sto only two options. The first option is, in effect, to ban fossil fuels. That's what p "absolute zero" means. No one allowed to extract, sell, or use fossil fuels glo anywhere in the world on pain of a massive fine. If that sounds unlikely, it's bal because it is. And even if a global ban were possible, do you or I in wealthy war countries in 2020 have any right to tell the citizens of poor and emerging min economies in the 2060s not to touch their fossil fuels?Some people argue that if g. we work hard enough we can drive down the cost of renewable energy so far Wh that we won't need to ban fossil fuels, the people will stop using them of their y own accord. This kind of thinking is dangerously optimistic. For one thing, don' renewable energy costs might not go down as fast as they hope. I mean, t remember, nuclear energy was meant to be too cheap to meter in the 1970s, but they even more importantly, we've no idea how low fossil fuel prices might fall in ? response to that competition. There are so many uses of fossil carbon, from aviation fuel to cement production, it's not enough for carbon-free alternatives to outcompete the big ones, to stop fossil fuels from causing further global warming, carbon-free alternatives would need to outcompete them all.So the only real alternative to stop fossil fuels causing global warming is to decarbonize them. I know that sounds odd, decarbonize fossil fuels. What it means is, one ton of carbon dioxide has to be safely and permanently disposed of for every ton generated by the continued use of fossil fuels. Now, consumers can't do this, so the responsibility has to lie with the companies that are producing and selling the fossil fuels themselves. Their engineers know how to do it. In fact, they've known for decades.The simplest option is to capture the carbon dioxide as it's generated from the chimney of a power station, or blast furnace, or refinery. You purify it, compress it, and re-inject it back underground. If you inject it deep enough and into the right rock formations, it stays there, just like the hydrocarbons it came from. To stop further global warming, permanent storage has to mean tens of thousands of years at least, which is why trying to mop up our fossil carbon emissions by planting trees can help, but it can only be a temporary stopgap.For some applications like aviation fuel, for example, we can't capture the carbon dioxide at source, so we have to recapture it, take it back out of the atmosphere. That can be done; there's companies already doing it, but it's more expensive. And this points to the single most important reason why recapturing and safe disposal of carbon dioxide is not already standard practice: cost. It's infinitely cheaper just to dump carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than it is to capture it and dispose of it safely back underground.But the good news is, we don't need to dispose of 100 percent of the carbon dioxide we generate from burning fossil fuels right away. Economists talk about costeffective pathways, by which they mean ways of achieving a result without unfairly dumping too much of the cost onto the next generation. And a costeffective pathway, which gets us to decarbonizing fossil fuels, 100 percent carbon capture and storage by 2050, which is what net-zero means, takes us through 10 percent carbon capture in 2030, 50 percent in 2040, 100 percent in 2050.To put that in context, we are currently capturing and storing less than 0.1 percent. So don't get me wrong, decarbonizing fossil fuels is not going to be easy. It's going to mean building a carbon dioxide disposal industry comparable in size to today's oil and gas industry. The only entities in the world that have the engineering capability and the deep pockets to do this are the companies that produce the fossil fuels themselves. We can all help by slowing down our use of fossil carbon to buy them time to decarbonize it, but they still have to get on with it.Now, adding the cost of carbon dioxide disposal will make fossil fuel-based products more expensive, and a 10 percent storage requirement by 2030, for example, might add a few pence to the cost of a liter of petrol. But, unlike a tax, that money is clearly being spent on solving the problem, and of course, consumers will respond, perhaps by switching to electric cars, for example, but they won't need to be told to do so. And crucially, if developing countries agreed to use fossil fuels that have been progressively decarbonized in this way, then they never need accept limits on the absolute amount that they consume, which they fear might constrain their growth.Over the past couple of years, more and more people have been talking about the importance of carbon dioxide disposal. But they're still talking about it as if it's to be paid for by philanthropy or tax breaks. But why should foundations or the taxpayer pay to clean up after a stillprofitable industry? No. We can decarbonize fossil fuels. And if we do decarbonize fossil fuels, as well as getting things like deforestation under control, we will stop global warming. And if we don't, we won't. It's as simple as that. But it's going to take a movement to make this happen.So how can you help? Well, it depends on who you are. If you work or invest in the fossil fuel industry, don't walk away from the problem by selling off your fossil fuel assets to someone else who cares less than you do. You own this problem. You need to fix it. Decarbonizing your portfolio helps no one but your conscience. You must decarbonize your product.If you're a politician or a civil servant, you need to look at your favorite climate policy and ask: How is it helping to decarbonize fossil fuels? How is it helping to increase the fraction of carbon dioxide we generate from fossil fuels that is safely and permanently disposed of? If it isn't, then it may be helping to slow global warming, which is useful, but unless you believe in that ban, it isn't going to stop it.Finally, if you're an environmentalist, you probably find the idea of the fossil fuel industry itself playing such a central role in solving the climate change problem disturbing. "Won't those carbon dioxide reservoirs leak?" you'll worry, "Or won't some in the industry cheat?" Over the coming decades, there probably will be leaks, and there may be cheats, but those leaks and those cheats will make decarbonizing fossil fuels harder, they don't make it optional.Global warming won't wait for the fossil fuel industry to die. And just calling for it to die is letting it off the hook from solving its own problem. In these divided times, we need to look for help and maybe even friends in unexpected places. It's time to call on the fossil fuel industry to help solve the problem their product has created. Their engineers know how, we just need to get the management to look up from their shoes.Thank you.