eBook Organisational Behaviour Engaging People and Organisations 2e By Ricky W. Griffin, Jean M. Phillips, Stanley M. Gully, Andrew Cre

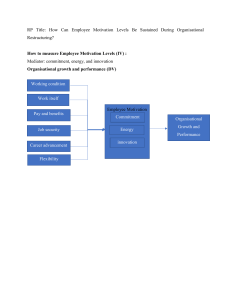

advertisement