Balance Sheets & Ice Cream: Understanding Capital Structures

advertisement

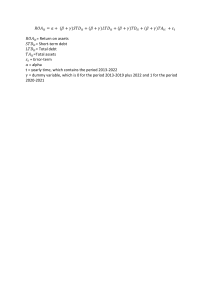

Good morning Ghosties, It's almost December 2021. More than 20 months after the initial lockdown, all we can say is oh-mi-CRON while rolling our eyes and waiting for the next edition of "My fellow South Africans..." Sigh. One of the guaranteed outcomes of a new variant is that markets will be volatile. Bad news will be met with nasty sell-offs in "reopening stocks" (like hotel groups) and good news will see them bounce back. The extent of the volatility in a particular stock is often linked to the amount of leverage on the balance sheet. This is just a fancy way of describing how much debt the company has. For that reason, I've decided to kick off a series of Ghost Mails on capital structures and debt vs. equity. Because I'm a simple ghost at heart, I use the analogy of an ice cream. I like ice cream. Rights offer, wrong time. We need a quick accounting 101 to help us understand capital structure: Accounting 101: Assets = Equity + Liabilities In other words, whenever a company needs to fund assets (like a new project, an acquisition or just keeping the lights on during lockdowns), there is the choice to use either equity or debt capital. You can either ask shareholders or banks for money. A "rights offer" is something you would've seen quite regularly in the market over the past year. It sounds daunting, but this fancy terminology is just based on simple concepts that anyone can understand. So, what is a rights offer? What is a rights issue? These terms are used interchangeably. I've even been guilty of that at times. It's not the end of the world as the concepts are similar. A rights offer is the invitation to existing shareholders to subscribe for more shares and a rights issue is the actual issue of those shares to investors. It's just a timing difference in the same process. The important point to remember is that a rights offer (I'll go with that term for ease) is the process of tapping into existing shareholders for more equity capital i.e. more money! Raising equity capital like this is a vanilla transaction in the market. If that's too boring, you can follow the Brait approach and issue "Exchangeable Bonds" which are listed debt instruments that are convertible into shares. This means Brait can raise debt from investors other than banks. More on that in weeks to come as we unpack capital structures. Before we deal with Brait's Wakaberry equivalent with all the toppings (remember those?), we need to deal with simple ice creams first. Start with vanilla. Capital structures can be really simple. In fact, many small businesses have the simplest structure of all: equity capital only. This is the plain vanilla ice cream. No Flake, sugar cone or other toppings. The simple capital structures in SMEs are mainly there because banks don't like lending to small businesses. They far preferred plowing money into trustworthy listed companies, like Steinhoff or EOH. When they do lend to entrepreneurs rather than listed companies, those entrepreneurs need to send weekly DNA samples to the bank and sign their lives away. This is despite all those wholesome adverts you see of a smiling entrepreneur with a florist or a coffee shop, JUST SO HAPPY because the bank has changed their lives by lending at Prime + 5% in return for a personal surety and rights to the first born child. As you can tell, I'm not sure that banks play enough of a role in facilitating growth in small businesses. The capital structure is based on the most fundamental principle in finance: risk vs. return. The "cost of equity" is the return that shareholders need on their investment. The "cost of debt" is the return that debt providers need on their investment. In my example above, the cost of debt is Prime + 5%. This is an important point: a debt provider is essentially investing in a debt instrument issued by the company. People always say that banks lend money to small businesses and that large companies issue debt instruments. In both cases, there is an investment in debt by whoever is providing the money. That loan agreement that you sign with the bank is a debt instrument. The difference between a small company taking out debt and a large company issuing debt in the market is that the debt of large companies can be traded among "fixed income" investors. Debt is called fixed income because the interest rate and thus the return is a known factor (even if it has some variability), whereas equity returns can vary wildly. Debt in any company will always be a cheaper source of funding than equity. This is because debt is less risky for the capital provider and more risky for the business. It comes with security, like the right to be paid back first if the company is liquidated and personal sureties that shift the risk from the company to the owners. When entrepreneurs introduce debt into a business, the capital structure kicks it up a gear. We are now in vanilla and strawberry mix territory. I do love a good soft serve machine. How much vanilla? How much strawberry? Adding too much strawberry ice cream (debt) to a vanilla ice cream cone (equity) can make the entire thing fall over. This is especially true when the wind is howling in Blouberg, which would be the equivalent of an economic shock or an unexpected Family Meeting. For most people though, a little bit of both is great. It makes the entire ice cream more enjoyable. There is an entire industry dedicated to the mix of vanilla and strawberry ice cream for companies. For large corporates, the strawberry ice cream sometimes converts into vanilla when certain milestones are achieved, with a sprinkling of nuts for good measure. If you can remember that the capital structure is just the mix of ice cream on the cone and the decision about sprinkles, you're well on your way. The cone or the cup supports the capital structure The ice cream ratios: mix and coverage. When assessing a balance sheet (or Statement of Financial Position, because international accounting standard boards are desperate to stay relevant and so they rename things for no reason), investors look at the mix of debt and equity (strawberry vs. vanilla) and the level of interest coverage to hold it all together (the cone vs. the cup). The ratios vary: • Debt : Equity is the ratio of strawberry to vanilla ice cream • Debt : Assets is the percentage of the total ice cream that is made up of strawberry For example, if strawberry is 40% and vanilla is 60%, then the Debt : Equity ratio is 40/60 = 66.67% and the Debt : Assets ratio is 40%. In listed property funds, the key ratio is called Loan-to-Value and is basically the Debt : Assets ratio. The word "value"" is used because the properties are recognised at their market values in the balance sheet rather than at historical cost like in non-property companies. And interest coverage? Coverage ratios link the income statement (sorry, I mean the Statement of Comprehensive Income) to the balance sheet. They measure the relationship between debt and operating profits to service that debt. They are sometimes called debt service ratios. One would frequently use Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortisation (EBITDA) because this is a reasonable proxy for operating cash flows in the business unless there are significant distortions in levels of inventory, debtors, creditors or capex requirements. Interest coverage is measured as EBITDA : interest cost and another common coverage ratio is net debt : EBITDA. Net debt is total debt minus cash. If the cone or the cup is too small for the amount of ice cream, then it's going to spill. Think of the cup or cone as the level of profitability in the business. Cups are stronger than cones, so the safest ice cream (even in a Blouberg wind) would be in a cup that is larger than requirements. A half-eaten sugar cone won't help in the wind, no matter how sweet those profits are. Now, take these learnings and go buy an ice cream later. It will cement the analogy for you and you'll be supporting our battered and beaten tourism / hospitality / restaurant industry.