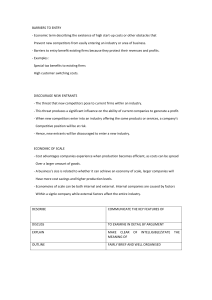

Strategic Management Textbook: Competitiveness & Globalization

advertisement