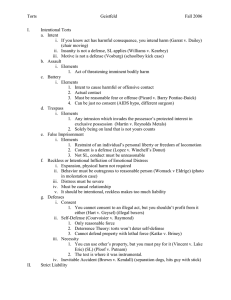

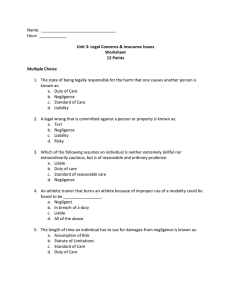

Torts Exam Preparation Negligence Negligence is: a lack of proper care and attention/carelessness. Carelessness = key element of negligence, foundation for legal liability. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Negligence Formula: Duty of care: does the defendant owe the plaintiff a duty of care? Breach of care: Has the defendant breached a duty of care? Causation: Was the damage suffered by the claimant, caused by the defendants breach of that duty? Remoteness: was the damage a sufficiently proximate consequence of the breach? Defences: does the defendant have any defences that may relieve him/her? Liabilities/Remedies: what is recoverable/what damage can the plaintiff claim. (vicarious liability: Rose v Plenty) Foreseeability & Proximity: (consider if the def reasonably had foreseen the damage/injury caused to their neighbour) In establishing a prima facie duty of care, the first requirement is that a reasonable person in the defendants person would have been able to foresee, that harm could result to the plaintiff if he or she failed to take reasonable care. Home Office v Dorset Yacht Co Ltd: (government bodies and vicarious liability) This case widened the scope of duty of care. The officers owed a duty of care to the respondents as they ought to have foreseen as a likelihood in the absence of adequate control/supervision. McCarthy v Wellington City [1996] NZLR 481 (CA): (extension of proximity): council left detonators in a safe without safety signage. Boys removed pin from hinge. Explosives taken home, later given to little brother. Hand exploded. the council were held liable as it may have been reasonably foreseen that the detonators could be obtained by an irresponsible person. Involving cases of harm, a duty care may prevail on foreseeability grounds – even in the absence of proximity. North Shore City Council v Attorney-General (The Grange): “foreseeability is at best a screening mechanism, to exclude claims which must obviously fail because no reasonable person in the shoes of the defendant would have foreseen the loss.” Rolls-Royce v Carter Holt Harvey: (contract vs tort) two stages of inquiry were run together. Noting that the boundary between proximity and policy can merge. Duties were covered in contract not tort. Patel v de Boer: (foreseeable that brakes could be tampered) bus stolen when parked on top of hill, window was left down by bus driver and the theft reached through the window and released brake of bus on a hill, rolled down hill and damage plaintiffs house. The actual act itself was not foreseeable but the type of damage was foreseeable. (ie, the damage a bus causes to property when flying downhill is foreseeable, but a man releasing bus brake is not. (1) Duty of Care: (neighbour principle, two stage test) Reasonable foreseeability of harm to others is a necessary condition for a duty to arise, but frequently in cases involving negligently inflicted economic loss, it is necessary but no sufficient condition. Donohue v Stevenson: In this case, Lord Atkin (at 580) established the neighbour principle. This principle is based on the idea that “you must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour.” Anns v Merton: established the two stage test relevant for determining a duty of care. (1) Foreseeability and proximity: (2) policy considerations (anything negating liability): o NOTE: policy considerations are founded on individual autonomy. The courts must always consider if it is fair, just and reasonable to impose the duty of care and whether it opens indeterminate liability. Torts Exam Preparation NOTE: Prima facie proximity: somebody who is closely and proximately affected by a tortfeasors act. Close proximity may constitute physical vicinity, casual, circumstantial, or assumed. Palsgraf v Long Island Railroad (US): (series of events) platform guard assisted man into train entry. Man dropped package containing fireworks. Explosion caused injury to woman across platform. Platform guard not liable as they could not have foreseen that their actions assisting a man would result in harm to a woman. The element of proximity requires that a person could reasonably foresee a specific harm occurring as a result of their actions. (2) Breach of Duty of Care: (the objective reasonable person test) Question = Whether the defendants conduct fell below the standard of care. The standard of care would be what a reasonable person should have done in the situation. (the question is what should have been done, not what could have been done). Whether the standard of the reasonable person has been attained must be determined in light of what is being done in what particular circumstances. LEADING CASE: Blyth v Birmingham Waterworks (1856): (always apply): “The defendants might have been liable for negligence, if, unintentionally, they omitted to do that which a reasonable person would have done or did that which a person taking reasonable precautions would not have.” This case established that an individual should be judged against the actions of a reasonable man, who is not extraordinary, nor superhuman. A person must contemplate what should be done (common sense) not what could have been done (hindsight). Standard of Care to apply: (only need to prove one to establish Breach of duty but go over all). Need to consider what the defendants purpose was in running the risk and whether there was any social utility in the defendants actions. Weighing all the following considerations, you need to determine whether the defendant was justified and therefore acted as a reasonable person would have done. Factors: 1. Probability of harm (real risk): Bolton v Stone: (low probability of harm due to the high fence): the probability of harm was too remote as precautionary measures were already taken, although the risk was high. Duty of care is not breached where a foreseeably real risk is so extremely rare that such an occurrence might be considered an isolated incident. Wagon Mound No 2: (high probability of harm due to nature of fire): distinguished Bolton as probability of harm was deemed to be high due to the presence of a real risk, which is one that no reasonable man could discount. Care is breached where a reasonable person in the same profession may foresee a real risk as a consequence of acing carelessly, even if such risks are low. 2. Gravity of risk: (where an incident is likely to result in serious injury, there is a higher expectation that precautionary measures have been undertaken to sufficiently eliminate those risks). McCarthy v Wellington City [1966]: (gravity of risk high): probability of boys stealing detonators was low, however it was foreseeable, and the gravity of risk was great. It was readily foreseeable that insufficiently storing the detonators from public access would likely result in a horrific accident. 3. Social Value: (whether continuing to carry out an activity an activity for societies benefit outweighs the risks of the activity): (high social value may negate the breach of duty where such benefits to the public reasonably outweigh the risks). Tomlinson v Congleton: quarry converted into leisure area. Warning signs prohibiting swimming, rangers employed. A boy was rendered quadriplegic after diving into the shallows. The council were not liable to provide premises protection as they had taken adequate precautions to warn of danger. The park was safe and there was an obvious risk. (res ipsa loquitur: obvious). A premises used for social recreation is not rendered dangerous if adequate precautions have been met to warn of potential risks on site. 4. Burden of precautionary measures: (a defendant is expected to reduce risks where the burden of taking reasonable preventative measures is low given the circumstances). Bolton v Stone: (High burden): building a higher fence for the cricket arena is a high burden of precautionary measure. Stadium already had a high fence; cost and time Torts Exam Preparation to build fence etc. the burden for the cricket grounds to take extra precaution was high as they had taken practical measures by installing a fence to prevent injury. Wagon Mound No 2: (low burden) the action to prevent the fire was to stop welding, a low burden of precautionary measures. It was not unreasonable for them to minimise risks by alleviating the leak. Goldman v Hargreaves: (reasonable person test) (low burden): tree left to burn out. The occupier was liable – omitting to put out the fire was unreasonable. The burden for the occupier to put the fire out was low. McCarthy v Wellington: (probability of harm = high; gravity of risk = high; social value of the activity = low; burden of precautionary measures = low) Omission/Failure to Act: (only mention/address if it forms part of the question) General principle = person bound to take care not to inflict damage but not bound to take care positively to prevent injury. A person is bound to exercise care not to inflict damage resulting from their omissions, but not obliged to prevent an injury from happening that would peril themselves. Hill v Chief Constable of W. Yorks Police [1989] AC 53 (HL): someone arrested for misdemeanours. He was suspected but released for lack of evidence. Subsequently murdered two more. The police were not liable. They hold a duty of public safety generally, but there existed no indication these specific women were in distinctively greater risk. Principle: there is no duty to the public to apprehend criminals expeditiously, as this may detriment the effective function of the police and exhaust resources. (3) Causation This involves analysing whether there is a link between the defendants actions and the damage caused. The two elements cause in fact and cause in law must be established. (causation and remoteness can be considered together). 1. Cause in fact (but for): would a claimant still suffer the detriment had the defendant not conducted the prima facie wrongdoing? If yes, claim fails. If no, claim succeeds. 2. Cause in law (novus actus interveniens): a cause may fail where it is inconsistent with legally established maxims. Cause in fact: (but for test): Yania v Bigan (1959) 155 A 2d 343: (obligation to rescue) coal operation. Water in trenches. Land owner enticed a neighbouring operator into the water to start the extraction pumps. The neighbour drowned. The land owner owed no duty of care to the neighbour. Knowing the dangers, the neighbour drowned as a result of placing himself into danger, not as a result of being enticed. Principle: a person is under no obligation to rescue another person. All invitees must have awareness of risks on the land or otherwise be notified of them. Hughes v Lord Advocate (HL): workmen on tea break. Boys saw tent over exposed manhole, no safety signage. Both went down. Dropped lamp causing explosion and injury. The workmen owed a duty of care – exposing manhole and omitting to alleviate the hazard was the casual nexus (connection) of the series of events. Principle: a person must exercise an ordinary degree of precaution to inhibit a person from being allured into the vicinity where danger could be anticipated. (But for the defendants negligent act the damage could not have occurred) Barnett v Chelsea 1969: (ALWAYS APPLY): Doctor negligently sent patient home and patient died of arsenic poisoning. The but for test was not proven because there was no causal link between the death and the failure to diagnose arsenic poisoning, as patient would have died anyway. This case established the principle but for the defendants negligent actions would the claimant have suffered the damage. (In applying this principle, is there a causal link between defendants negligent act and the damage/injury). Atlas Properties v Kapiti Coast DC: flooding became excessive due to undersized culvert built by the council. The council were not liable in causation. The degree of flooding that occurred was inevitable. Even if the culvert was adequate, the downstream constriction was the cause. Causation is negated where the extent of damage will occur anyway, regardless of precipitating factors being present. Torts Exam Preparation Baker v Willoughby (HL): (unbroken chain) (supervening events): B was hit by a car injuring his ankle resulting in reduced income. He sued for lost earnings. Subsequently, robber shot the same leg resulting in amputation. The subsequent injury did not change his capacity resulting from the 1st injury – the claim for loss of income would have been pursued anyway regardless of subsequent events. Causation remains unbroken where the occurrence of an outcome is certain to happen anyway, regardless of supervening events. Performance Cars v Abraham (EWCA): (causation broken) negligent driver hit the claimants car, it required a respray. Prior to this, the car had also been hit by another negligent driver, requiring respray. The driver was not liable as the respray was still pending from the prior accident – the claimant suffered no extra burden (Baker followed). Principle: successive causes: compensation cannot be granted where the claimant suffers no extra burden from subsequent causes. the employees novus actus interveniens had rendered foreseeable risk, breaking the chain of causation. Where a person’s unreasonable action result in subsequent harm, it comes causa causans (immediate cause); initial injury ceases being a contributory factor. Reeves v Commissioner of Police (HL): prisoner was a known suicide risk. Police left hatch in cell door open, prisoner tied his shirt around it and hung himself. The police were responsible. The prisoner’s action did not break the chain of causation as the suicide was causa cusata (cause resulting from initial cause). Where a person is placed in the care of another, their action of committing suicide does not break the chain of causation. Harvey v PD (AU): (contributory negligence: where a victim contributes to a foreseeable detriment through their own actions, they may be proportionately liable): woman contracted HIV, gave birth. Knowing such risks, the woman was liable as she contributed by proceeding with the pregnancy. Principle: (amplification of risk): a person who amplifies a risk after it has become known to them, breaks the chain of causation. Cause in Law: (novus actus interveniens): (important to look at the circumstances in between) (4) Remoteness of Damage: (the proximately close and not too remote or indirect damage is considered) Whether casual connection exists between the defendants action and the claimants injury. When an intervening 3rd party action breaks the chain of causation, that new action subsumes the liability from the originating cause. Lamb v London Borough (EWCA): (causation failed) council works caused water mains to be burst, causing subsidence to house. Whilst unoccupied, squatters moved in and damaged the premises. chain of causation broken due to third party intervening. Though it was foreseeable that squatters could trespass as a result of the councils negligent action, the squatters outrageous conduct broke the chain of causation. Principle: (3rd party interference): an intervening 3rd party may break the chain of causation where their conduct is so capricious that consequences cannot be readily foreseen. McKew v Holland (HL): employee fractured leg at work. In recovery he walked down stairs unaided when he felt his leg give way and jumped to the bottom. He sustained permanent injury. The employer was responsible for the initial injury but TEST = is the damage the kind of damage that a reasonable person would have foreseen: (was the type of damage foreseeable) This is where you look at how far the legal responsibility of damages should be attributed to the defendant. So long as the damage is traceable to the defendants negligent act, you are liable. The range of damage: the range of close proximity extends as far as such losses may be foreseeably expected to touch upon. Wagon Mound No 2: this case establishes that if damage is foreseeable, it is not too remote. A foreseeable risk is a real risk that a reasonable person would not brush aside. If you choose to run the risk of the act then there is remoteness, if the risk is not foreseeable, you are too remove and the negligence test fails. Torts Exam Preparation (burden of proof is always on the defendant.) Taupo Borough Council v Birnie: (pure economic loss) council works caused flooding to hotel resulting in physical damage and loss of business – diminished reputation. The council were liable as consequential economic loss was readily foreseeable and proximate result of damages caused. The losses contributed directly to financial decline. A claimant is entitled to remuneration of profit loss where such losses are a foreseeably proximate result of the negligent act. AG v Geothermal Produce NZ Ltd 1987 (CA): (extent of damages): (should the defendant have been aware of potentially future business): weed control contractors hired and decimated crop. The Crown was vicariously liable as they were aware of the greenhouse existing close to the spraying area. Negligent conduct causes foreseeable loss of business (where such conduct is in physically proximate range) garnishes retribution for business loss. A claimant may recoup business losses sustained from affected mercantile goods as a foreseeably proximate consequence of the negligent act. o You could use this case to argue that a reasonable person would have looked up weather patterns before spraying. Claimants had a clear market plan for new business, therefore defendants negligent and liable for future loss). Contributory Negligence: the burden of proof is on the defendant to prove; they have to show that the claimants did not take reasonable care of themselves through causation and remoteness. This is where the claimant would have foreseen the harm and contributed in some way. Contributory Negligence Act 1947, s 3: this section provides that “where any person suffers damage as the result partly of his own fault…the damages recoverable…shall be reduced to such an extent that the court thinks just and equitable having regard to the claimant’s share in the responsibility for the damage.” Dairy Containers v NZI Bank [1995] 2 NZLR 30: (this case affirms contributory negligence in NZ) 3 directors committed fraudulent activities causing detriment to the company. The auditor failed his duty of care to responsibly act on this. The auditor successfully raised a contributory negligence defence to mitigate his failed duty of care. This reduced his accountability to 70% of the awarded costs. Where employees inflict fraud upon their own company, an auditor is not fully liable for revealing such fraud as their own employees had caused the damage. Jones v Livox Quarries (QBD): quarry worker hitched a lift on traxcavtors the towbar. A dumber truck negligently rear-ended him. Legs amputated. The quarry worker was 20% responsible; the employer was 80% at fault. The claim succeeded but the liable as he placed himself in foreseeable harm. principle: (reasonableness) a person is liable under contributory negligence if they ought reasonably to have foreseen that, not acting as reasonable/prudent person, they might hurt themselves. Hartley v Balemi (QBD): house was built incorrectly. This result in water ingress when it rained causing damage. The owners did not do what an ordinary reasonable person would do. They did not hire a surveyor for correct planning, instead believing they could do it themselves. Principle: (self-negligence): a person who does not do what an ordinary reasonable person would do, resulting in selfdetriment, may be liable in contributory negligence. Eggshell Skull Rule: A duty of care must consider the victims physical and mental states as they currently exist and are assessed regardless of unforeseen latent vulnerabilities. A victim of mental injury must always be able to show that he or she was put at foreseeable risk of mental injury. If the plaintiff has an “egg-shell personality” then his or her mental injury is unlikely to be reasonably foreseeable. Page v Smith [1996] AC 155 (HL): def caused car crash. The plaintiff suffered no physical harm, but his previously held chronic fatigue syndrome resurfaced as a direct cause. Principle: (psychological injury): a latent psychological vulnerability in remission is a proximate condition that may resurface as a result of a negligent act. (5) Defences: Torts Exam Preparation NOTE: (Age): there is no age in which a child is precluded from contributory negligence; the elderly are not expected to act as younger persons. The standard of care is what would be reasonably expected of a child of that age. Volenti non fit injura (assumption of risk): (How the person assumed the risk yet proceeded to follow through) Question to ask: Did they voluntarily assume the risk? (Tomlinson, dived into water when there was a sign that said not to, thus he voluntarily assumed the risk) No harm is done where a person assumes the risk voluntarily. This operates as a bar for claims succeeding. 6. Vicarious/Shared Liability: (joint and concurrent liability: each tortfeasor is liable for the damage they have inflicted. Claimants cannot recover more than their losses: unjust enrichment) Employment relationships: an employer may be held vicariously liable for torts committed by their employees in the course of employment. 1. Nettleship v Weston (UKCA): learner driver crashed car, injuring his instructor. The learner driver claimed she could not be held to the same standard as an experienced driver. The learner drive was 50% responsible; the instructor was at 50% fault as he was in partial control of the vehicle therefore assumed a degree of risk. The standard of care for a learner driver is no different than an experienced driver. Instructors also voluntarily assume a standard of care. Tomlinson v Congleton: (voluntary assumption of risk) quarry converted into leisure area. Warning signs prohibiting swimming, rangers employed. A boy was rendered quadriplegic after diving into the shallows. The council were not liable to provide premises protection as they had taken adequate precautions to warn of danger. The park was safe and there was an obvious risk. (res ipsa loquitur: obvious). A premises used for social recreation is not rendered dangerous if adequate precautions have been met to warn of potential risks on site. Illegality: (someone cannot benefit from their own illegality) No claim in negligence if the negligent act or harm occurred whilst claimant participating in illegal activities. Ashton v Turner (QBD): claimant injured whilst driving away from committing a burglary. Crashed causing injury to his passenger. This case establishes that the law will not recognise a duty of care owed by a participant involved in a crime to another. 2. 1. 2. 3. Contracts OF service: (employee): a person who acts on the command of their superiors (vicarious liability applies). Contracts FOR service: (independent contractor): a person who engages themselves to perform service and does so on their own account (vicarious liability precluded/excluded). Establishing vicarious liability: Has a tort been committed? What is the nature of relationship between tortfeasor/responsible person? (e.g., employer or contractor). Does a connection between tort/relationship exist? (e.g., done whilst on work shift). Test to identify the Employee: 1. “Economic Reality Test”: consider the economic relationship: do they use their own tools, hire their own help or take on a business risk? How are they being paid, are they paying their own tax etc? If yes = independent contractor. Lee Ting Sang v Chung Chi (PC): skilled stone mason worked for a subcontractor on a construction site, using their tools. He became injured in the course of carrying out his work. It was held that the stone mason was an employee and received a wage. He was not involved in investing in the work on site and had not Torts Exam Preparation used his own tools or hired his own helpers. A person who works for a subcontractor may be an employee if they do not supply their own tools. 2. “Control Test”: a servant is a person subject to the command (how and when_ of their master in which they shall do the master’s work. Some servants have a degree of initiative. Steel Structures Ltd v Rangitiki County (CA): “The test in all circumstances is one of the right to control not merely what is done, but how it is to be done.” Yewens v Noakes (1880): “A servant is a person subject to the command of his master as to the manner in which he shall do his work”. (6) Remedies: (aim is to place a party back to the position they would have been in had the tort not taken place) 1. Compensatory Damages: Restores the claimant back to the position had the tort not taken place, through monetary awards: State what has been lost/damaged (e.g., loss of business) Put the claimant back into the same financial position that they were in before the damage occurred. 2. Nominal Damages: Small damages awarded to show the tortfeasor that their actions are wrong. This may be when damage occurred, but that damage has no value (e.g., damage to reputation). 3. Exemplary (punitive) Damages: The sole purpose is to punish the wrongdoing. The courts may award substantial damages to punish an entity for knowingly participating in wrongdoing. ACC: Accident Compensation Act 2001: s 3: “The purpose of this Act is to enhance the public good and reinforce the social contract…by providing for a fair and sustainable scheme for managing personal injury…” s 20: Cover for personal injury: s 20(1)(a): did the event occur in New Zealand after 1 April 2002? s 16: NZ meaning. s 20(2)(a): personal injury by Accident. s 25: accident defined in as “the application of force, resistance external to the body; sudden movement to avoid a force; twisting movement. s 28: work-related personal injury. This includes injury suffered while on break at the place of employment, injury suffered travelling to and from work (if transport provided by employer). s 28(4): personal injury caused by a work-related gradual process, disease or injection. Grimshaw v Ford Motor (US): awarded 2.4m in compensatory damages and 125m in punitive damages due to the size of their company and the value they placed on human life over their own financial situation. Donselaar v Donselaar (CA): longstanding family dispute. a man trespassed onto his brothers land. brother hit him over the head with a hammer. Man sued. The case was dismissed as the man was the principle irritant as the trespasser. Couch v AG (SC): prisoner on parole let go from the RSA, returned later and killed 3 people. The department owed a duty of care. For exemplary damages, the harm must be a foreseeable consequence of persons actions. Cases: Queenstown Lakes v Palmer: This case provides that if relief is not covered under the Act, an affected person may instead bring litigation proceedings under the common law. McDonald v ARCIC: (not a gradual process) (not covered by ACA) In this case, cover was declined on the basis that the injury had ‘triggered’ his arthritis which existed before the injury occurred. This established that an injury which relates to a preexisting or underlying condition will not be covered under the ACA. Torts Exam Preparation ACC v Ambros: (likelihood/proximity test): wife suffered a heart attacked and passed away as a consequence of a complicated childbirth procedure. Husband sued claiming medical error. Cover granted in the HC. COA declined cover applying the likelihood test. Calver: (can be a single event or series of events) Knox v ARCIC: (personal injury caused by a work-related gradual process, disease or infection) (3 part test – s 30(2)). ACC v Monk: (treatment causing mental injury): This case established that an ordinary consequence of treatment will not be covered. However, an unusual consequence of treatment which may cause mental injury will be covered. ACC v Toomey: (work-related mental injury) (employment vs volunteer work). This case established that the courts can sometimes take a generous approach when determining whether a person should be entitled to cover. A self-employed builder assisted the fire service to rescue people trapped in a building following a Christchurch earthquake. He feared he would not make it out alive. Hornby v ACC: 4. 1. Notes: s 317(1): ACC operatives as a ‘legislative bar’ on bringing personal actions for damages. A person is restricted from brining proceedings (independently of the Act) for damages arising from personal injury covered by ACA. Treatment injury: Look to s 33: ‘Treatment’ defined in s 33: “giving of treatment, diagnosis, failure to provide treatment” etc. ‘Treatment injury’ is defined in s 32: 1. a ‘personal injury’ (see definition in s 26, remember personal injury also includes mental injury caused by physical injury). 2. Suffered by a person seeking/receiving treatment (as defined in s 33). 3. Caused by the treatment: it must be proved on the balance of probabilities, that the treatment caused the injury (Ambros). (Adlam: failure to provide treatment: must demonstrate a departure for appropriate standard.) (Relly: implications of a delay in treatment). 2. And not a necessary part of ordinary consequence of the treatment: ACC v Ng: ‘an outcome that is outside the normal range of outcomes, something out of the ordinary which occasions a measure of surprise’. Disentitlements: (ss 119-122) s 119: for wilfully self-inflicted personal injuries and suicide. s 120: a person convicted of murder cannot receive compensation in relation to that death. s 121: no entitlements are payable during any person in which the claimant is in prison. s 122: no entitlements are payable if the injury occurred in the course of committing an offence (with a max term of two years). Working through an ACL problem: s 20(1)(a):The first step is to establish that the person has suffered a personal injury in New Zealand on or after 1 April 2002. (NZ is defined in s 16: the scheme applies to residents and non-residents however, non-resident only entitled to limited benefits; not covered while on board (or embarking/disembarking) from ship/aircraft/other conveyance while traveling to, around or from NZ: s 23). NOTE: a person ordinarily resident in NZ may be covered for personal injury suffered outside NZ: s 22. The second step is to establish that the personal injury is of any of the kind described in s 26(1)(a)-(e). 3. Common Law Tort of Privacy Hosking v Runting Torts Exam Preparation Trespass to the Person Assault Battery False imprisonment