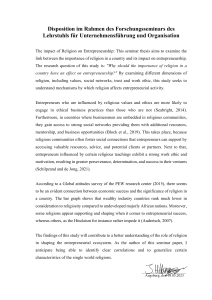

Small Bus Econ (2021) 57:1681–1691 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00372-6 Unraveling the entrepreneurial mindset Donald F. Kuratko & Greg Fisher & David B. Audretsch Accepted: 3 June 2020 / Published online: 17 June 2020 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2020 Abstract Scholars have examined various aspects of the entrepreneurial mindset, which have provided insights into its attributes, qualities, and operations. However, the different perspectives have led to a diverse array of definitions. With the array of differing definitions, there arises the need to better understand the concept of an entrepreneurial mindset. Therefore, the question remains as to what exactly is the entrepreneurial mindset and how do people tap into it. In examining the literature, we find that three distinct aspects have arisen through the years: the entrepreneurial cognitive aspect—how entrepreneurs use mental models to think; the entrepreneurial behavioral aspect—how entrepreneurs engage or act for opportunities; and the entrepreneurial emotional aspects—what entrepreneurs feel in entrepreneurship. Using those as a basis for our work, we unravel the entrepreneurial mindset by examining deeper into the perspectives and discuss the challenges for implementing it. Keywords Entrepreneurial mindset . Entrepreneurial cognition . Entrepreneurial behavior . Entrepreneurial emotion D. F. Kuratko (*) : G. Fisher : D. B. Audretsch Kelley School of Business, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405, USA e-mail: dkuratko@indiana.edu G. Fisher e-mail: fisherg@indiana.edu D. B. Audretsch e-mail: daudrets@indiana.edu JEL classifications L26 . L29 1 Introduction “The mind is everything. What you think, you become.” - Buddha Entrepreneurship and innovation are central to individual and organizational success and advancement in the modern economy. Innovation is critical to entrepreneurship (Schumpeter 1942) and a primary instrument of competition for many firms (Baumol 2002). As technologies rapidly evolve and new markets dynamically emerge, so too does the individual ability to innovate and act in entrepreneurial ways sets certain individuals apart from others. But what does it take to for an individual to innovate and act in entrepreneurial ways? It appears that the paradigm of entrepreneurship has been elusive (Audretsch et al. 2015). Some have argued that innovation stems from the external environment and is largely dependent on being in a specific location like Silicon Valley or Route 128 in Boston. Others suggest it comes from being in an internal organizational environment with an informal atmosphere and a supportive organizational culture. Here, we argue that the true source of innovation and entrepreneurship is an ability and perspective that resides within each one of us, something we refer to as the entrepreneurial mindset (Naumann 2017; Kuratko 2020). This 1682 D. F. Kuratko et al. mindset allows and empowers us to come up with new ideas, solve problems, generate creative solutions, and take action to pursue opportunities. It is the mental perspective that precedes our actions and feeds our emotions, allowing us to innovate. Yet, we tend to believe the myths that block our own ability to innovate. For example, some believe that innovation is an innate ability, while others believe you have to be a crazy risk taker to be an entrepreneur. This is sad because our true potential is enhanced by our ability to innovate and act entrepreneurially; this is accomplished by tapping into our entrepreneurial mindset. While some scholars have made broad and general references to the concept of the entrepreneurial mindset (e.g., Naumann 2017), few have clearly defined it or provided insights into its underlying attributes, qualities, and effects. So, the question remains as to what the entrepreneurial mindset is and how do people tap into it. 2 The entrepreneurial mindset’s key perspectives While some scholars have examined aspects of the entrepreneurial mindset and provided general insights into its attributes, qualities, and operations, the various different perspectives have led to a diverse array of definitions resulting in confusion about what it is and how it operates. So the question remains as to what exactly is the entrepreneurial mindset and how do people tap into it. By consolidating and integrating ideas from across diverse literatures that make reference to the entrepreneurial mindset, we propose that three distinct aspects of the entrepreneurial mindset exist. As depicted in Fig. 1, they are: 1. The cognitive aspect—how entrepreneurs use mental models to think. 2. The behavioral aspect—how entrepreneurs engage or act for opportunities. 3. The emotional aspects—what entrepreneurs feel in entrepreneurship. 2.1 The cognitive aspect Early in the development of the domain of entrepreneurship research, scholars adopted a psychological lens to study individual entrepreneurial characteristics (Hornaday and Aboud 1971; Carland and Carland 1992). More recently, entrepreneurship scholars have returned to their psychological roots to focus on cognitive processes of the entrepreneur (Baron 1998; Mitchell et al. 2002a; Shepherd and Krueger 2002) and have argued that cognition represents an important process lens through which to “reexamine the people side of entrepreneurship” (Mitchell et al. 2002a, b). Cognition defined In science, cognition refers to mental processes. These processes include attention, remembering, producing and understanding language, solving problems, and making decisions. The term comes from the Latin cognoscere, which means “to know,” “to conceptualize,” or “to recognize,” and refers to a faculty for the processing of information, applying knowledge, and changing preferences. Cognition is used to refer to the mental functions, mental processes (thoughts), and mental states of intelligent humans (Estes 1975). Social cognition theory introduces the idea of knowledge The Cognitive Aspect (Thinking) Fig. 1 The triad of the entrepreneurial mindset The Emotional Aspect (Feeling) The Behavioral Aspect (Acting) Unraveling the entrepreneurial mindset structures—mental models (cognitions) that are ordered in such a way as to optimize personal effectiveness within given situations—to the study of entrepreneurship (Fiske and Taylor 1991). Concepts from cognitive psychology are increasingly being found to be useful tools to help probe entrepreneurial-related phenomena, and, increasingly, the applicability of the cognitive sciences to the entrepreneurial experience are cited in the research literature (Grégoire et al. 2011; Tryba and Fletcher 2020). Entrepreneurial cognition Mitchell et al. (2002a): 97) defined entrepreneurial cognition as “the knowledge structures that people use to make assessments, judgments, or decisions involving opportunity evaluation, venture creation, and growth.” In other words, entrepreneurial cognition is about understanding how entrepreneurs use simplifying mental models to piece together previously unconnected information that helps them to identify and invent new products or services, and to assemble the necessary resources to start and grow businesses. Specifically, then, the entrepreneurial cognitions view offers an understanding as to how entrepreneurs think and “why” they do some of the things they do. Research has also extended the definition to the international context (Hafer and Jones 2015). While the research has focused on entrepreneurial cognitions (Mitchell et al. 2002a, b; Baron 2004), a new stream of thinking links the foundation of the entrepreneurial mind-set to cognitive adaptability, which can be defined as the ability to be dynamic, flexible, and self-regulating in one’s cognitions given dynamic and uncertain task environments. Adaptable cognitions are important in achieving desirable outcomes from entrepreneurial actions (Haynie and Shepherd 2009). In this light, a team of researchers developed a situated, metacognitive model of the entrepreneurial mind-set that integrates the combined effects of entrepreneurial motivation and context, toward the development of metacognitive strategies applied to information processing within an entrepreneurial environment (Flavell 1979; Haynie et al. 2010). Consider an entrepreneur faced with the entrepreneurial task of developing a sound explanation for a new venture in preparation for an important meeting with a venture capitalist. Before the entrepreneur is prepared to evaluate alternative strategies, the entrepreneur must first formulate a strategy to frame how 1683 he or she will “think” about this task. This process is metacognitive. The process responsible for ultimately selecting a response (i.e., a particular venture strategy) is cognitive—the process responsible for ultimately selecting how the entrepreneur will frame the entrepreneurial task is metacognitive. Thus, metacognition is not to study why the entrepreneur selected a particular strategy for a set of alternative strategies (cognition), but instead to study the higher-order cognitive process that resulted in the entrepreneur framing the task effectually, and thus why and how the particular strategy was included in a set of alternative responses to the decision task (metacognition) (Haynie et al. 2012). Davis et al. (2016, p. 2) stated that the entrepreneurial mindset is a “constellation of motives, skills, and thought processes that distinguish entrepreneurs from nonentrepreneurs.” In sum, prior research on entrepreneurial cognition has suggested that founders and other entrepreneurs “think” differently than other individuals or business executives. In addition, the work on metacognition demonstrates how entrepreneurs formulate a strategy to frame how they will “think” about a task. Thus, the work on entrepreneurial cognition has been substantively examined (Shepherd and Patzelt 2018; Grégoire et al. 2011). We integrate this into our conceptualization of the entrepreneurial mindset to suggest that the entrepreneurial mindset entails a way to formulate how to think and then actually think about an opportunity. However, it remains less clear as to how this “cognitive difference” leads to entrepreneurs’ efforts and actions. In order to understand how an individual is much more likely to engage in entrepreneurial action, we examine that behavioral aspect of the entrepreneurial mindset in the next section. 2.2 The behavioral aspect Bird and Schjoedt (2009: 327) point out: “The end of all the cognition and motivation of entrepreneurs is to take some action in the world, and by doing so, give rise to a venture, an organization. Thoughts, intentions, motivations, learning, intelligence without action does not create economic value. The very nature of organizing is anchored in actions of individuals as they buy, sell, gather and deploy resources, work, etc.” It is this perspective that has inspired the important research examining entrepreneurial action and behavior (Van Geldren et al. 2018). 1684 Opportunity and creation Research has shown that the extent to which entrepreneurs identify opportunities and bring new products and services to market is based on their prior knowledge (Gruber et al. 2013; Shepherd and DeTienne 2005). Prior knowledge, often from a human capital perspective, has been of immense interest in explaining aspects of opportunity identification for entrepreneurs. Consequently, specific prior knowledge is central to the entrepreneur’s ability to identify an opportunity—or miss an opportunity entirely (McKelvie and Wiklund 2004). Once an opportunity is identified, entrepreneurs must then create a venture. While a true statement, its narrow framing neglects the complete process of entrepreneurship and much of the reality regarding how ventures and entrepreneurs come into being. A venture is not simply produced by an entrepreneur. Entrepreneurs do not preexist; they emerge as a function of the novel, idiosyncratic, and experiential nature of the venture creation process. Venture creation is a lived experience that, as it unfolds, forms the entrepreneur. In fact, the creation of a sustainable enterprise involves three parallel, interactive phenomena: emergence of the opportunity, emergence of the venture, and emergence of the entrepreneur. None are predetermined or fixed—they define and are defined by one another (Morris et al. 2012). This experiential view of the entrepreneur captures the emergent and temporal nature of entrepreneurship. It moves us past a more static “snapshot” approach and encourages consideration of a dynamic, socially situated process that involves numerous actors and events. It allows for the fact that the many activities addressed as a venture unfolds are experienced by different actors in different ways (Davidsson 2004). Moreover, it acknowledges that venture creation transcends rational thought processes to include emotions, impulses, and physiological responses as individuals react to a diverse, multifaceted, and imposing array of activities, events, and developments. This perspective is consistent with recent research interest in a situated view of entrepreneurial action (Berglund 2007). Entrepreneurial action McMullen and Shepherd (2006) proposed a conceptual model of entrepreneurial action—what they refer to as an “action framework” (p. 146). To do so, they linked the motivation and cognition perspective in entrepreneurship research with an actionoriented perspective by theorizing how an individual’s cognition and motivation lead to entrepreneurial action. D. F. Kuratko et al. They proposed a model in which entrepreneurial action is driven by knowledge (what a person knows) and motivation (an individual’s personal strategy) which together lead to a third-person opportunity (an opportunity for someone). The feasibility and desirability of the third-person opportunity is in turn assessed by an individual before being claimed as a first-person opportunity which spurs action. Thus, entrepreneurial action is an outcome of a cognitive and motivational process. Sarasvathy (2001, 2008) also combined entrepreneurial cognition with action in developing a theory of effectuation, in which entrepreneurs “take a set of means as given and focus on selecting between possible effects that can be created with that set of means” (2001: 245). She combined cognitive aspects of entrepreneurship, such as attending available means in constructing opportunities and making decisions with respect to what one is willing to lose (the affordable loss principle), with more action-oriented aspects of entrepreneurship, such as leveraging relationships (the strategic partnerships principle) and exploiting contingencies (the leveraging contingencies principle) (Sarasvathy 2008). When conceptualized as a process, the cognitive aspects of effectuation are assumed to spur the actions of partnering and leveraging contingencies. Despite being combined with action-related aspects, effectuation, at its core, is a cognitive theory reflected in it commonly being referred to as “effectual reasoning” or the “logic of effectuation” (Sarasvathy 2001, 2008). Alvarez and Barney (2007) developed an actionorientated theory they labeled “creation theory” to account for the creation versus discovery of opportunities. They argued that entrepreneurial “[opportunities] are created, endogenously, by the actions, reactions, and enactment of entrepreneurs exploring ways to produce new products or services” (p. 15). Creation theory assumes that an entrepreneur’s actions are the essential source of opportunities, and it is contrasted with discovery theory where opportunities are assumed to exist independent of entrepreneurs. The work of Alvarez and Barney (2007) has prompted a number of conceptual and empirical studies that take a constructionist perspective and associate entrepreneurial opportunities with action on the part of an entrepreneur to create that opportunity (e.g., Alvarez et al. 2015; Alvarez et al. 2013; Garud et al. 2010; Wood and McKinley 2010). A mindset has been viewed as goal directed emphasizing prior experiences (CohenKdoshay and Meiran 2007). Unraveling the entrepreneurial mindset Recent research has uncovered specific actions that entrepreneurs have exhibited in the execution of the mindset. For example, Fisher et al. (2020) introduce the concept of entrepreneurial hustle. They propose that entrepreneurial hustle is an entrepreneur’s urgent, unorthodox actions that are intended to be useful in addressing immediate challenges and opportunities under conditions of uncertainty, which allows entrepreneurs to navigate uncertainty. This is especially true for exploiting new and untested technologies and new market opportunities that are common for entrepreneurial opportunities (Audretsch 1995; Schumpeter 1934). Behavioral definitions of the mindset Shepherd, Patzelt and Haynie (2010, p. 62) adapted from Ireland et al. (2003) and McMullen and Shepherd (2006) to define the entrepreneurial mindset as the “ability to rapidly sense, act, and mobilize in response to a judgmental decision under uncertainty about a possible opportunity for gain.” McGrath and MacMillan (2000) believe that while entrepreneurs stay alert to new opportunities, they pursue those opportunities that align with their strategy. McMullen and Kier (2016, p. 664) agree by stating that the entrepreneurial mindset is the “ability to identify and exploit opportunities without regard to the resources currently under their control”. The entrepreneurial mindset has also been described as a dynamic process of vision, change, and creation, requiring an application of energy and passion toward the creation and implementation of new ideas and creative solutions. It is the vision to recognize opportunity where others see chaos, contradiction, and confusion (Kuratko 2020). Thus, the behavioral aspect of the entrepreneurial mindset begins with people (Mariz-Péreza et al. 2012). By tapping into one’s entrepreneurial mindset, the opportunity exists to make tomorrow better through innovation. Again, we integrate this into our conceptualization of the entrepreneurial mindset to suggest that the entrepreneurial mindset entails a way to behave and act an opportunity and create a venture. However, there also exists an emotional side to this mindset that must be acknowledged as individuals tap into their entrepreneurial mindsets. We examine this particular aspect next. 2.3 The emotional aspect Popular view Emotions that entrepreneurs experience or feel have been discussed in the popular media. Surprise, anticipation, and stress are more internally 1685 focused, and therefore, these emotions are ones that the entrepreneur must handle in the confines of his or her mind. How the entrepreneur mitigates these feelings is demonstrated in the running of the business, and the managing of relationships (Cole 2017). Another article interviewed researchers about emotion and entrepreneurship. These researchers assessed 66 entrepreneurship teams in 569 decision-making rounds. They assert that one of the main drivers of entrepreneurial emotion comes from uncertainty. They also found that if entrepreneurship teams are comprised of friends, then this deepens the sense of commitment among team members. Friends turned business partners also work inherently well together, since there is an established emotional understanding that underpins the relationship (Knowledge @ Wharton 2019). Academic focus Studies in the academic literature have focused on different elements of emotion. One study analyzed how emotion regulation of a venture’s lead founder impacts ventures survival. The study examined two types of emotion regulation: cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. Overall, regulation of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression appear to have mixed effects on venture survival depending on the individual context of the venture (De Cock et al. 2020). Fodor and Pintea (2017) assessed the relationship between affect and entrepreneurial performance. This concept of dispositional affect refers to the ability to feel a range of emotions, including enthusiasm and pleasurable engagement. The negative side of this affect is susceptibility to distress and nervousness. These emotions are often connected to a singular event for entrepreneurs. Yet, another study examined the idea of entrepreneurial judgment being affected by emergent role demands (Giménez Roche and Calcei 2020). Within the domain of emotion for entrepreneurs, research has shown that there is a dark side derived from the energetic drive of entrepreneurs which acts as a destructive source. Kets de Vries (1985) acknowledged the existence of certain negative factors that may envelop entrepreneurs and dominate their behavior. While some of these factors could have a positive aspect, it is important for entrepreneurs to understand their potential destructive side as well. Three specific ones have been identified: risk, stress, and ego. Confrontation with risk Entrepreneurs face a number of different types of risk (Janney and Dess 2006; Caliendo 1686 et al. 2009). These can be grouped into four basic areas: (1) financial risk, (2) career risk, (3) family and social risk, and (4) psychic risk. In most new ventures, the individual puts a significant portion of his or her savings or other resources at stake, which creates a serious financial risk. The entrepreneur also may be required to sign personally on company obligations that far exceed his or her personal net worth. The entrepreneur is thus exposed to personal bankruptcy (Caggese 2012). Career risk is another major risk to managers who have a secure organizational job with a high salary and a good benefit package. Because a new venture requires much of the entrepreneur’s energy and time, entrepreneurs face a family and social risk exposing their families to the risks of an incomplete family experience and losing former friends due to missed events (Zahra et al. 2006). However, the psychic risk may be the greatest risk to the well-being of the entrepreneur. Entrepreneurs who suffer financial, career, or family issues may be unable to bounce back because the psychological impact has proven to be too severe for them (Caliendo et al. 2010). Dealing with stress Some of the most common entrepreneurial goals are independence, wealth, and work satisfaction. To achieve their goals, however, these entrepreneurs were willing to tolerate these effects of stress (Afzalur 1996). In general, stress can be viewed as a function of discrepancies between a person’s expectations and ability to meet demands, as well as discrepancies between the individual’s expectations and personality. When entrepreneurs’ work demands and expectations exceed their abilities to perform as venture initiators, they are likely to experience stress. One research study has pointed out how entrepreneurial roles and operating environments can lead to stress. Lacking the depth of resources, entrepreneurs must adopt a multitude of roles, such as salesperson, recruiter, spokesperson, and negotiator. These simultaneous demands can lead to role overload (deMol et al. 2018). Finally, entrepreneurs often work alone or with a small number of employees and therefore lack the support from colleagues that may be available to managers in a large corporation (Kariv 2008). Boyd and Gumpert (1983) made a significant contribution to entrepreneurial stress with presentation of stress-reduction techniques which include acknowledging its existence, developing coping mechanisms, and facing unacknowledged personal needs. Goldsby et al. D. F. Kuratko et al. (2005) examined the relationship between exercise and the attainment of personal and professional goals for entrepreneurs. The study addressed the issue by examining the exercise regimens of 366 entrepreneurs and the relationship of exercise frequency with both the company’s sales and the entrepreneur’s personal goals. Specifically, the study examined the relationship that two types of exercise—running and weightlifting— had with sales volume, extrinsic rewards, and intrinsic rewards. The results indicated that running is positively related to all three outcome variables, and weightlifting is positively related to extrinsic and intrinsic rewards. This study demonstrates the value of exercise regimens on relieving the stress associated with entrepreneurs. The entrepreneurial ego In addition to the challenges of risk and stress, the entrepreneur also may experience the negative effects of an inflated ego. In other words, certain characteristics that usually propel entrepreneurs into success also can be exhibited to their extreme. We examine some of these characteristics that may hold destructive implications for entrepreneurs (Wright and Zahra 2011). Entrepreneurs are driven by a strong need to control and sometimes a need for power in their ventures. This internal focus of control spills over into a preoccupation with controlling everything. An obsession with autonomy and control may cause entrepreneurs to work in structured situations only when they have created the structure on their terms. This, of course, has serious implications for networking in an entrepreneurial team, because entrepreneurs can visualize external control by others as a threat of subjection or infringement on their will. Worse yet, the strong desire for power can be a corruptive force that could lead to negative consequences. Thus, the same characteristic that entrepreneurs need for successful venture creation also contains a destructive side (Beaver and Jennings 2005). The entrepreneur’s ego is involved in the desire for success. Although many of today’s entrepreneurs believe they are living on the edge of existence, constantly stirring within them is a strong desire to succeed in spite of the odds. Thus, the entrepreneur rises up as a defiant person who creatively acts to deny any feelings of insignificance. Some have termed this behavior as “hubris” of an entrepreneur (Hayward et al. 2006). Others have termed it as overconfidence (Salamouris 2013). One study examined overconfidence across four cultures and found overplacement and overprecision were Unraveling the entrepreneurial mindset common in many entrepreneurs (Muthukrishna et al. 2018). The individual is driven to succeed and takes pride in demonstrating that success. Therein lie the seeds of possible destructiveness. The ceaseless optimism that emanates from entrepreneurs (even through the bleak times) is a key factor in the drive toward success. Entrepreneurs maintain a high enthusiasm level that becomes an external optimism—which allows others to believe in them during rough periods. However, when taken to its extreme, this optimistic attitude and overconfidence can lead to a fantasy approach to the business (Koellinger et al. 2007; Hogarth and Karelaia 2011). A self-deceptive state may arise in which entrepreneurs ignore trends, facts, and reports and delude themselves into thinking everything will turn out fine. This type of behavior can lead to an inability to handle the reality of the business world (Haynes et al. 2015). These examples do not imply that all entrepreneurs fall prey to these scenarios, nor that each of the characteristics presented always gives way to the “destructive” side. Nevertheless, all potential entrepreneurs need to know that the dark side of an entrepreneurial mindset exists. In essence, the emotional aspect describes what entrepreneurs feel. Many times it is those feelings that can drive entrepreneurial mindset. It is clear that the emotional side must be considered a crucial element of the entrepreneurial mindset. Examining the three aspects of the entrepreneurial mindset certainly offers value but only to the extent that they are integrated for an interactive relationship that fosters the initiation of the entrepreneurial mindset. 3 The interacting elements of the entrepreneurial mindset Central to understanding the entrepreneurial mindset is the recognition that the three aspects described above— the cognitive aspect, the behavioral aspect, and the emotional aspect—do not operate independently of one another; rather they interact and reinforce each another. The cognitive aspect, which focuses on the mental functions, thoughts, and mental states of entrepreneurial individuals (Estes 1975), serves as an enabler and facilitator of individual actions and emotions (Wood et al. 2012). It is commonly recognized that individual thoughts impact actions and emotions (Dweck and Leggett 1988). This underpins the common 1687 philosophical notion, attributed to Buddha stating that: “The mind is everything. What you think, you become” (Stevenson 2019). Yet, in the same way that the cognitive aspect of the entrepreneurial mindset serves as an enabler and facilitator of individual actions and emotions, the behavioral aspect—what entrepreneurs do—also influences their cognitions and emotions. An individual’s mind and feelings are highly reactive to what they are doing. By taking action entrepreneurs can influence how they feel about the world around them and begin to transform the perceptions and mental models they adopt (McMullen and Shepherd 2006; Sarasvathy 2001). Emotions too can have a direct and significant impact on the other aspects of the entrepreneurial mindset. The way that an entrepreneur feels, and the affect they experience, can affect how they think about things and actions that they take (Cardon et al. 2012; Morris et al. 2012). Thus, there is a reciprocal and self-reinforcing cycle between the different aspects of the entrepreneurial mindset (Shepherd et al. 2010). If individuals embrace this mindset and realize the interactive nature of the three aspects then they will likely become even more entrepreneurial over time; whereas those individuals that fail to utilize the interactive aspect of their entrepreneurial mindset will find it more difficult to tap into their entrepreneurial mindset as time progresses. The self-reinforcing cycle of the entrepreneurial mindset also means that a breakdown in any one aspect of the mindset—the cognitive aspect, the behavioral aspect, and the emotional aspect—will make it difficult for an entrepreneur to operate optimally in the other areas. For example, if an individual avoids acting on their entrepreneurial impulses, perhaps because a manager in a corporation discourages any kind of entrepreneurial behavior (Kuratko et al. 2005), then over time that individual’s passion for entrepreneurial endeavors and their cognitions toward entrepreneurial opportunities will likely dissipate. Similarly, someone who is not allowed explore and express their passions and other emotions related to entrepreneurship will overtime, stop thinking and acting in entrepreneurial ways (Cardon et al. 2009). In the same vein, someone who adopts mental models and ongoing thoughts that guard against opportunity pursuit, risk taking, and exploration, will find it very difficult to sustain any kind of emotion or action to support an entrepreneurial mindset (Shepherd et al. 2010). 1688 The delicate nature of the entrepreneurial mindset means that individuals who strive to embrace this mindset as a means to live their life to its potential, need to guard against placing themselves in situations where one (or more) of the aspects is threatened or put under strain. And if they do find themselves in situations where one of the aspects of the entrepreneurial mindset is threatened or constrained, they need to work hard to eliminate the threat or constraint. This might entail an internal locus of control, where they actively manage their cognitions, emotions and behaviors so as to foster elements of each that support their entrepreneurial mindset. Alternatively, it may entail an external locus of control, where they remove themselves from the situation that is creating the threat or constraint, so that it is easy to think, act and feel in a way that supports and reinforces an entrepreneurial mindset. The external influence of contextual factors and relationships on different aspects of an individual’s entrepreneurial mindset is part of the reason that context matters so much in framing and influencing entrepreneurial behavior (Welter et al. 2019). As John Donne (1624) admonished four centuries ago, “No man is an island.” An organizational context clearly matters (Kuratko et al. 2014). Compelling empirical evidence suggests that entrepreneurial behavior is neither equally nor randomly distributed across firms and other organizations (Parker 2018). A firm or organization comprised of and conducive to individuals with an entrepreneurial mindset can be characterized as entrepreneurial and is more likely to continue to be entrepreneurial, allowing it to adapt to technological changes and industry dynamics, seizing new opportunities enabling it to be competitive over time (Kuratko et al. 2015). So too can a place, such as a community, city, region, state or even entire country be comprised by individuals with and conducive to an entrepreneurial mindset. The empirical evidence confirms that entrepreneurial activity is not evenly distributed across geographic space (Bennett 2020). However, the spatial variance in entrepreneurial activity is closely linked to characteristics and institutions specific to the specific place. Thus, what holds for firms and organizations also holds for communities, cities, regions, states and entire countries— they can be considered to be entrepreneurial if they are characterized by people with and are conducive to an entrepreneurial mindset. In addition, if they continue to support and foster all aspects of the entrepreneurial mindset—the cognitive aspects, the behavioral aspects, D. F. Kuratko et al. and the emotional aspects—then such communities, cities, regions, states, and countries will likely be more effective and competitive over time, generating new innovations, ideas, and business models that allow them to flourish in the long term (Kuratko et al. 2017). 4 Conclusions Research and thinking about entrepreneurship has developed something of a schizophrenia in understanding what distinguishes the entrepreneurial mindset. One strand of the literature views the cognitive decision making as the distinctive feature characterizing and differentiating entrepreneurship. A second view puts the focus on behavior as the most salient feature of the entrepreneurial mindset. Yet, a third strand of the literature revolves around the emotional aspects of the entrepreneurial mindset. This paper integrates all three views and proposes a unified view of what constitutes the entrepreneurial mindset—thoughts, action, and feelings (see Fig. 1). Attempting to understand the entrepreneurial mindset from only one of these three perspectives—cognitive, behavioral, or emotional—incurs the risk of misrepresenting and inaccurately characterizing the entrepreneurial mindset. That the entrepreneurial mindset is influenced by the context, spanning from the organizational to the spatial, only exacerbates the inherent complexity. The popular press is replete with such mischaracterizations erroneously based on a limited perspective and context, such as entrepreneurs “embrace failure” (Markowitz 2010). Similarly, the understanding, analysis, and advocacy of polices to foster entrepreneurship may be limited or even misguided if their view of the entrepreneurial mindset along with the context is limited (Lerner 2009). Still, this paper demonstrates that by incorporating all three dimensions of the triad of the entrepreneurial mindset a fuller and more replete understanding of the entrepreneurial mindset is within the grasp of both scholars as well as thought leaders in business and policy. It is up to subsequent research to probe the various ways that these three dimensions of the entrepreneurial mindset—cognition, behavior, and emotions—interact with each other as well as how they are shaped and influenced by the specific context. Unraveling the entrepreneurial mindset References Afzalur, R. (1996). Stress, strain, and their moderators: An empirical comparison of entrepreneurs and managers. Journal of Small Business Management, 34(1), 46–58. Alvarez, S. A., & Barney, J. B. (2007). Discovery and creation: Alternative theories of entrepreneurial action. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 1(1–2), 11–26. Alvarez, S. A., Barney, J. B., & Anderson, P. (2013). Forming and exploiting opportunities: The implications of discovery and creation processes for entrepreneurial and organizational research. Organization Science, 24(1), 301–317. Alvarez, S. A., Young, S. L., & Wooley, J. L. (2015). Opportunities and institutions: A co-creation story of the king crab industry. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(1), 95–112. Audretsch, D. B. (1995). Innovation, growth and survival. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 13(4), 441–457. Audretsch, D. B., Kuratko, D. F., & Link, A. N. (2015). Making sense of the elusive paradigm of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 45(4), 703–712. Baron, R. (1998). Cognitive mechanisms in entrepreneurship: Why and when entrepreneurs think differently than other people. Journal of Business Venturing, 13(4), 275–295. Baron, R. (2004). The cognitive perspective: A valuable tool for answering entrepreneurship's basic “why” questions. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(2), 221–239. Baumol, W. J. (2002). The free-market innovation machine. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Beaver, G., & Jennings, P. (2005). Competitive advantage and entrepreneurial power: The dark side of entrepreneurship. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 12(1), 9–23. Bennett, D. L. (2020). Local institutional heterogeneity & firm dynamism: Decomposing the metropolitan economic freedom index. Small Business Economics, (In press). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00322-2. Berglund, H. (2007). Entrepreneurship and phenomenology. In J. Ulhoi & H. Neergaard (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research methods in entrepreneurship (pp. 75–96). London: Edward Elgar. Bird, B., & Schjoedt, L. (2009). Entrepreneurial behavior: Its nature, scope, recent research, and agenda for future research. In Understanding the entrepreneurial mind (pp. 327–358). Springer, New York. Boyd, D. P., & Gumpert, D. E. (1983). Coping with entrepreneurial stress. Harvard Business Review, 61(2), 46–56. Caggese, A. (2012). Entrepreneurial risk, investment, and innovation. Journal of Financial Economics, 106(2), 287–307. Caliendo, M., Fossen, F. M., & Kritikos, A. S. (2009). Risk attitudes of nascent entrepreneurs–new evidence from an experimentally validated survey. Small Business Economics, 32(2), 153–167. Caliendo, M., Fossen, F. M., & Kritikos, A. S. (2010). The impact of risk attitudes on entrepreneurial survival. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 76(1), 45–63. Cardon, M. S., Wincent, J., Singh, J., & Drnovsek, M. (2009). The nature and experience of entrepreneurial passion. Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 511–532. 1689 Cardon, M. S., Foo, M. D., Shepherd, D., & Wiklund, J. (2012). Exploring the heart: Entrepreneurial emotion is a hot topic. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(1), 1–10. Carland, J. C., & Carland, J. W. (1992). Managers, small business owners, entrepreneurs: The cognitive dimensions. Journal of Business & Entrepreneurship, 4(2), 55–66. Cohen-Kdoshay, O., & Meiran, N. (2007). The representation of instructions in working memory leads to autonomous response activation: Evidence from the first trials in the flanker paradigm. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 60(8), 1140–1154. Cole, N. (2017). 7 powerful emotions that all entrepreneurs feel. Inc.com. https://www.inc.com/nicolas-cole/7-powerfulemotions-all-entrepreneurs-feel.html Accessed 16 Apr 2020. Davidsson, P. (2004). A general theory of entrepreneurship: The individual-opportunity nexus. International Small Business Journal, 22(2), 206–219. Davis, M. H., Hall, J. A., & Mayer, P. S. (2016). Developing a new measure of entrepreneurial mindset: Reliability, validity, and implications for practitioners. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 68(1), 21–48. De Cock, R., Denoo, L., & Clarysse, B. (2020). Surviving the emotional rollercoaster called entrepreneurship: The role of emotion regulation. Journal of Business Venturing, 35(2), 105936. deMol, E., Ho, V. T., & Pollack, J. M. (2018). Predicting entrepreneurial burnout in a moderated mediated model of job fit. Journal of Small Business Management, 56(3), 392–411. Donne, J. (1624). No man is an island. Meditation 17; Devotions upon Emergent Occasions, https://web.cs.dal. ca/~johnston/poetry/island.html Accessed 26, Apr 2020. Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256. Estes, W. K. (1975). Handbook of learning and cognitive processes (Vol. 1). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum. Fisher, G., Stevenson, R., Burnell, D., Neubert, E., & Kuratko, D.F. (2020). Entrepreneurial hustle: Navigating uncertainty and enrolling venture stakeholders through urgent and unorthodox actions. Journal of Management Studies, Forthcoming. Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (1991). McGraw-Hill series in social psychology. Social cognition (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill Book Company. Flavell, J. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906–911. Fodor, O. C., & Pintea, S. (2017). The “emotional side” of entrepreneurship: A meta-analysis of the relation between positive and negative affect and entrepreneurial performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 310. Garud, R., Kumaraswamy, A., & Karnøe, P. (2010). Path dependence or path creation? Journal of Management Studies, 47(4), 760–774. Giménez Roche, G. A., & Calcei, D. (2020). The role of demand routines in entrepreneurial judgment. Small Business Economics, (In press). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-01900213-1. Goldsby, M. G., Kuratko, D. F., & Bishop, J. W. (2005). Entrepreneurship and fitness: An examination of rigorous 1690 exercise and goal attainment among small business owners. Journal of Small Business Management, 43(1), 78–92. Grégoire, D. A., Corbett, A. C., & McMullen, J. S. (2011). The cognitive perspective in entrepreneurship: An agenda for future research. Journal of Management Studies, 48(6), 1443–1477. Gruber, M., MacMillan, I. C., & Thompson, J. D. (2013). Escaping the prior knowledge corridor: What shapes the number and variety of market opportunities identified before market entry of technology start-ups? Organization Science, 24(1), 280–300. Hafer, R. W., & Jones, G. (2015). Are entrepreneurship and cognitive skills related? Some international evidence. Small Business Economics, 44(2), 283–298. Haynes, K. T., Hitt, M. A., & Campbell, J. T. (2015). The dark side of leadership: Towards a mid-range theory of hubris and greed in entrepreneurial contexts. Journal of Management Studies, 52(4), 479–505. Haynie, M., & Shepherd, D. A. (2009). A measure of adaptive cognition for entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 695–714. Haynie, J. M., Shepherd, D. A., Mosakowski, E., & Earley, P. C. (2010). A situated metacognitive model of the entrepreneurial mindset. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(2), 217–229. Haynie, J. M., Shepherd, D. A., & Patzelt, H. (2012). Cognitive adaptability and an entrepreneurial task: The role of metacognitive ability and feedback. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(2), 237–265. Hayward, M. L. A., Shepherd, D. A., & Griffin, D. (2006). A hubris theory of entrepreneurship. Management Science, 52(2), 160–172. Hogarth, R. M., & Karelaia, N. (2011). Entrepreneurial success and failure: Confidence and fallible judgment. Organization Science, 23(6), 1733–1747. Hornaday, J. A., & Aboud, J. (1971). Characteristics of successful entrepreneurs. Personnel Psychology, 24, 141–153. Ireland, R. D., Hitt, M. A., & Sirmon, D. G. (2003). A model of strategic entrepreneurship: The construct and its dimensions. Journal of Management, 29, 963–990. Janney, J. J., & Dess, G. G. (2006). The risk concept for entrepreneurs reconsidered: New challenges to the conventional wisdom. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(3), 385–400. Kariv, D. (2008). The relationship between stress and business performance among men and women entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 21(4), 449–476. Kets de Vries, M. F. R. (1985). The dark side of entrepreneurship. Harvard Business Review, 63(6), 160–167. Knowledge @ Wharton. (2019). How feelings and friendship factor into startup success and failure. https://knowledge. wharton.upenn.edu/article/role-of-feelings-inentrepreneurship/ Accessed 16 Apr 2020. Koellinger, P., Minniti, M., & Schade, C. (2007). “I think I can, I think I can”: Overconfidence and entrepreneurial behavior. Journal of Economic Psychology, 28(4), 502–527. Kuratko, D. F. (2020). Entrepreneurship: Theory, process, practice (11th ed.). Mason: Cengage publishers. Kuratko, D. F., Ireland, R. D., Covin, J. G., & Hornsby, J. S. (2005). A model of middle-level managers’ entrepreneurial behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29, 699– 716. D. F. Kuratko et al. Kuratko, D. F., Covin, J. G., & Hornsby, J. S. (2014). Why implementing corporate innovation is so difficult. Business Horizons, 57(5), 647–655. Kuratko, D. F., Hornsby, J. S., & Hayton, J. (2015). Corporate entrepreneurship: The innovative challenge for a new global economic reality. Small Business Economics, 45(2), 245– 253. Kuratko, D. F., Fisher, G., Bloodgood, J., & Hornsby, J. S. (2017). The paradox of new venture legitimation within an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 119– 140. Lerner, J. (2009). Boulevard of broken dreams: Why public efforts to boost entrepreneurship and venture capital have failed– and what to do about it. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Mariz-Péreza, R. M., Teijeiro-Alvareza, M. M., & GarcíaAlvareza, M. T. (2012). The relevance of human capital as a driver for innovation. Human Resource Management Review, 35(98), 68–76. Markowitz, E. (2010). Why Silicon Valley loves failures. Inc, august 16. https://www.inc.com/eric-markowitz/brilliantfailures/why-silicon-valley-loves-failures.html accessed 26, Apr, 2020. McGrath, R., & MacMillan, I. (2000). The entrepreneurial mindset: Strategies for continuously creating opportunity in an age of uncertainty. Canbridge: Harvard Business School Press. McKelvie, A., and Wiklund, J. (2004). How knowledge affects opportunity discovery and exploitation among new ventures in dynamic markets? In Opportunity Identification and Entrepreneurial Behaviour, ed. J. E. Butler (Greenwich, CT: Information age publishing), 219–239. McMullen, J. S., & Kier, A. S. (2016). Trapped by the entrepreneurial mindset: Opportunity seeking and escalation of commitment in the Mount Everest disaster. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(6), 663–686. McMullen, J. S., & Shepherd, D. A. (2006). Entrepreneurial action and the role of uncertainty in the theory of the entrepreneur. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 132–152. Mitchell, R., Busenitz, L., Lant, T., McDougall, P., Morse, E., & Smith, B. (2002a). Toward a theory of entrepreneurial cognition: Rethinking the people side of entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 27(2), 93– 105. Mitchell, R. K., Smith, J. B., Morse, E. A., Seawright, K. W., Peredo, A. M., & McKenzie, B. (2002b). Are entrepreneurial cognitions universal? Assessing entrepreneurial cognitions across cultures. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26(4), 9–33. Morris, M. H., Kuratko, D. F., & Schindehutte, M. (2012). Framing the entrepreneurial experience. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(1), 11–40. Muthukrishna, M., Henrich, J., Toyokawa, W., Hamamura, T., Kameda, T., & Heine, S. J. (2018). Overconfidence is universal? Elicitation of genuine overconfidence (EGO) procedure reveals systematic differences across domain, task knowledge, and incentives in four populations. PLoS One, 13(8), e0202288. Naumann, C. (2017). Entrepreneurial mindset: A synthetic literature review. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 5(3), 149–172. Unraveling the entrepreneurial mindset Parker, S. (2018). The economics of entrepreneurship (Cambridge: Cambridge University press, 2nd edition). Salamouris, I. S. (2013). How overconfidence influences entrepreneurship. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 2(8), 1–8. Sarasvathy, S. D. (2001). Causation and effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 243–263. Sarasvathy, S. D. (2008). Effectuation: Elements of entrepreneurial expertise. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The theory of economic development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Schumpeter, J. A. (1942). Capitalism, socialism, and democracy. New York: Harper and Brothers. Shepherd, D. A., & DeTienne, D. R. (2005). Prior knowledge, potential financial reward, and opportunity identification. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(1), 91–112. Shepherd, D. A., & Krueger, N. (2002). Cognition, entrepreneurship & teams: An intentions-based perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(2), 167–185. Shepherd, D. A., & Patzelt, H. (2018). Entrepreneurial cognition: Exploring the mindset of entrepreneurs. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG. Shepherd, D. A., Patzelt, H., & Haynie, J. M. (2010). Entrepreneurial spirals: Deviation-amplifying loops of an entrepreneurial mindset and organizational culture. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 34(1), 59–82. Stevenson, T. (2019). What we think is what we become: Control your mind, control your life. Medium, March 5. https://medium.com/@tom.stevenson78/what-we-think-iswhat-we-become-df58a698de99 Accessed 9 May 2020. 1691 Tryba, A., & Fletcher, D. (2020). How shared pre-start-up moments of transition and cognitions contextualize effectual and causal decisions in entrepreneurial teams. Small Business Economics, (In press). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-01900148-7. Van Geldren, M., Kautonen, T., Wincent, J., & Binari, M. (2018). Implementation intentions in the entrepreneurial process: Concept, empirical findings, and research agenda. Small Business Economics, 51(4), 923–941. Welter, F., Baker, T., & Wirsching, K. (2019). Three waves and counting: The rising tide of contextualization in entrepreneurship research. Small Business Economics, 52(2), 319–330. Wood, M. S., & McKinley, W. (2010). The production of entrepreneurial opportunity: A constructivist perspective. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 4(1), 66–84. Wood, M. S., Williams, D. W., & Grégoire, D. A. (2012). The road to riches? A model of the cognitive processes and inflection points underpinning entrepreneurial action. Advances in entrepreneurship, firm emergence and growth, 14, 207–252. Wright, M., & Zahra, S. (2011). The other side of paradise: Examining the dark side of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 1(3), 1–5. Zahra, S. A., Yavuz, R. I., & Ucbascaran, D. (2006). How much do you trust me? The dark side of relational trust in new business creation in established companies. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(2), 541–559. Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.