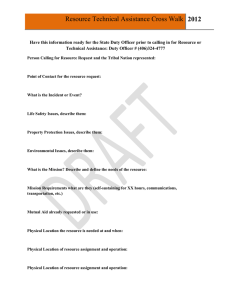

Afars, Issas . . . and Djiboutians: Toward a History of Denominations Simon Imbert-Vier Northeast African Studies, Volume 13, Number 2, 2013 (New Series) , pp. 123-149 (Article) Published by Michigan State University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/nas.2013.0012 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/536645 Access provided at 12 Jan 2020 00:46 GMT from University of Cambridge Afars, Issas . . . and Djiboutians: Toward a History of Denominations SIMON IMBERT-VIER, Centre d’études des mondes africains, France ABSTRACT This article analyzes the ethnic denominations around the Gulf of Tadjoura. By using travel narratives from the nineteenth century and colonial archives from the twentieth, it provides a history of these denominations, their construction and evolution, and the representations they carry. In the nineteenth century, denominations proposed by African informers were used by European travelers to describe the political and social situation in the area as they understood it. Later, the colonial administration wanted to identify groups and individuals in order to manage the inhabitants and secure its domination over the country. We show how this practice was an impossible task because of the identity lability of individuals and groups and the impossibility of defining accurate limits between them, either physical or symbolic. Nonetheless, these constructions have been used until now to legitimate access to the State and country’s resources. On 19 March 1967, 60 percent of the voters in the last French colony in continental Africa—Côte française des Somalis (CFS) or French Somaliland— officially chose the maintenance of French sovereignty with a new denomination: Territoire français des Afars et des Issas.1 Hardly ten years later, on 8 May 1977, 98.8 percent of the voters approved of the attainment of Northeast African Studies, Vol. 13, No. 2, 2013, pp. 123–150. ISSN 0740-9133. © 2013 Michigan State University. All rights reserved. 124 ▪ Simon Imbert-Vier independence of the country under the name of République de Djibouti. As one Djiboutian observer noted: “In order to remove from the first day of independence all tracks of tribalism, all risk of ethnical division, the new State’s officials borrowed from the country capital city . . . the prestigious name of Djibouti to give to the Republic.”2 To build a national identity, the new State did not identify itself in reference to its inhabitants but related to its main town to create new nationals: the Djiboutians. At the time of independence,3 the country was torn apart, literally by the Barrage encircling the town,4 but also because of a 20-year confrontation between independence militants and supporters of French sovereignty. With the growing demand for independence coming from some of the Djiboutian political leaders after 1958,5 and after the union of British and Italian Somaliland within the Republic of Somalia in 1960,6 the French administration associated Somalis with supporters of independence and favored inhabitants identified as Afars in accessing political and economic resources, such as employment on the harbor’s docks.7 Since 1896, the town of Djibouti— created from scratch in 1888 —was the capital city of the Côte française des Somalis, a colony created at the same time. Besides being an imperial outpost on the sea routes to Madagascar and Indochina, this port was the outlet of the railway from Addis Abeba, built between 1897 and 1917. This “railway territory,”8 regarded by the authorities as a land inhabited primarily by Somali nomadic cattle breeders, was the sole colonial investment until the beginning of the 1930s. Then, an extension toward the West and North began, ending around 1950 with the delimitation of the boundary with Ethiopia.9 Others inhabitants of the colony, who were called Danakil10 until the 1950s and who were mostly nomadic cattle breeders, were neglected by the colonial management. The 1958 ideological and political reversal brought to power leaders belonging to groups assimilated to those forgotten territories, behind the emblematical figure of Ali Aref Bourhan.11 In this context, the representation of an insurmountable division between those two groups—seen as the only autochthonous ones in the colony12—took shape and was expressed through the denomination of Territoire français des Afars et des Issas in 1967. This “identitary crystallization” aimed to distinguish (and so divide) the Issas from the Somalis and to bring the Afars to the fore. This link between the emergence of ethnic identification, its use, and colonial administrative chronology confirms the necessity to question those Afars, Issas . . . and Djiboutians ▪ 125 denominations, the way they were produced, and how the different political actors and entrepreneurs took hold of them. Those representations, although reversed again after independence in 1977, establish the access rights to the country’s resources. If power is assimilated to Somalis and opposition to Afar13—in an emblematic way during the Frud revolt in the 1990s—the national representation built within the single governing party always takes care to explicitly include representatives of different “national groups” the same way the colonial administration did. To question ethnic denominations in Djibouti does not mean to come back to crystallization or the symbols they represent, while individuals and identities overlap groups14 and groups themselves evolve.15 Even less does it mean trying to show “realities” that ethnic names could either cover or hide.16 Identification terms are not univocal; their meanings change according to situations and needs. As a practitioner of ethnic identification in Djibouti eventually stated, “different groups muddle up and different denominations overlap often to apply to same individual”;17 individual identities are multiple resources that actors can mobilize according to their need at a particular moment. However defined and expressed during the identification situation, they are later interpreted in different contexts to explain political situations involving groups, themselves described by the use of those tools without establishing the continuities. They can impose themselves on individuals, particularly within bureaucratization;18 their essentialization makes social structures more rigid for the advantage of those who can show evidence of the “good” identities in front of newcomers. Generally, in an identification situation— group or individual—three elements must be taken into account: identified person or group, identifying person, and identifying term.19 The analysis of the relationship between groups, individuals, and symbols carrying representations must take into account the identification situation— during which the requests and presuppositions of actors are usually neither explained nor shared—to clarify the concrete form of identity-building. Around the Gulf of Tadjoura, in those processes of identity-building, two main categories of actors intervene: Africans and Europeans. As far as we are concerned here, the former are the identified but also the identifying persons. They are the first producers of identifiers that they deliver with 126 ▪ Simon Imbert-Vier their own fluctuating conceptions and interests. The situation is different in particular if they identify their own group or another one. The other actors, the Europeans, are identifying persons: they wish to understand and describe social and political realities with various goals— commercial, politi- cal, administrative, or even scientific. They are filtering the information they get—mostly through the mediation of interpreters who add another bias—with their interrogations and previous knowledge, their readings, and acquaintance with other cultures. They can also intervene in the identifier production by special request. Within a description of denominations, it is impossible to fully get out of “ethnic vocabulary” and the conceptions it carries.20 However, studying the invention and changes of identifiers and their use, and the relationships between words and the construction they cover at one moment, allows one to rethink them, if not to really deconstruct them. I would like to open tracks for a history of denominations around the Gulf of Tadjoura, showing how they were identified and the representations they carried at the moment they were discovered by Europeans in the nineteenth century, and how they evolved as identity categories were used for political constructions21 and access to resources. The first Europeans to cross the actual Djiboutian territory, around 1840, collected identifiers and tried to organize them to describe the local political situation and to facilitate shorter and safer journeys; travelers around 1880 took a similar approach, adding the commercial and political purposes of the early colonial appropriation.22 In the 1930s, with the beginning of the conquest of the territory beyond the coast and the railway, the administration again took up this catalog of ethnic names to identify African social and political structures. From the Second World War, the administration made up and put into effect system- atic identification practices.23 They mainly consisted in relating inhabitants to already-identified groups, whose meanings and limits evolved dialectically during the process. A change happened in the meaning of the identification of the groups living within the Djiboutian territory and the relations between inhabitants and those identities when local political life began after 1945. In 1956, all nationals (French, then Djiboutians) became citizens and therefore eligible voters. At that moment, the policy of identification of the nationals was mostly aimed at ensuring continued French sovereignty Afars, Issas . . . and Djiboutians ▪ 127 over the territory, and subsequently at maintaining alliances within the ruling group that issued from the independence process. Descriptions from Nineteenth-Century Travelers Between 1841 and 1890, 11 travel accounts were published by ten Europeans who crossed the terrestrial areas around the Gulf of Tadjoura between 1839 and 1886,24 before the installation of colonial rule. One travel was narrated twice and one traveler made the journey two times. There were other travelers as well, but they did not publish accounts of their journeys. These narratives can be divided into two stages. The first stage, beginning in the late 1830s, consisted of travelers typically appointed by their governments whose purposes were mostly exploratory. Their accounts included geographical descriptions that detailed toponyms and described itineraries and obstacles, the peoples, and the social and political structures they encountered. From 1877, the travelers became implicated in the beginnings of the colonial movement and produced accounts that Isabelle Surun calls a process of conquest geography.25 In addition to a Protestant missionary speaking German, these writers included three French and three English voyagers traveling in two groups that met in Shewa, and three Italians in the second period. Some were mandated by their governments; others travelled more or less for themselves. Travelers went from the coast to Shewa. Return trips were only narrated by Rochet d’Hericourt’s (second trip), Paul Soleillet, and Jules Borelli. Table 1 summarizes the section of the crossing between the coast and the Awash river, which symbolized the entrance into Shewa.26 The first travelers all left from Tadjoura and took approximately the same route alongside Lake Assal and the southern end of Lake Abbé. It is only during the second period that Zeila, Assab, or Obock (passing through Tadjoura) became starting points. The last traveler, Borelli, departed finally from Tadjoura after failing from Djibouti on the South shore of the Gulf. Writers mix three main sources for their descriptions: information obtained from local inhabitants, either directly or via intermediaries; their own observations and eyewitness accounts; and publications from previous travelers. The first European travelers across the Gulf of Tadjoura landscape 128 ▪ Simon Imbert-Vier Table 1: Chronology of Travels and Publications DEPARTURE ARRIVAL NARRATOR PLACES DAYS PUBLICATION 26 April 1839 29 May 2839 Karl Wilhelm Isenberg Tadjoura-Awash 34 1843 3 August 1839 27 September 1839 Xavier Rochet d’Héricourt Tadjoura-Allata 55 1841 17 May 1841 11 July 1841 Cornwallis Harris R. Kirk Tadjoura-How 41 1844 1842 7 March 1842 20 May 1842 Charles Johnston Tadjoura-How 56 1844 15 September 1842 20 October 1842 Xavier Rochet d’Héricourt Tadjoura-Awash 36 1846 15 May 1877 9 September 1877 Antonio Cecchi Zeila-Bonta 118 1886 22 August 1882 29 September 1882 Paul Soleillet Obock-Awash 39 1886 11 January 1883 10 April 1883 Pietro Antonelli Assab-Dhora 92 1883 28 July 1885 − Emilio Dulio Assab- − 1886-88 14 April 1886 10 June 1886 Jules Borelli TadjouraBoulohama 58 1890 identified groups and imposed the earliest taxonomies. They tried to describe social and political organization but were confronted quickly by the ambiguities and approximations of rigid definitions in the face of fluid and ever-changing social realities. Because our travelers do not detail the specific modes by which they acquired their information, we can only gather some clues. Their knowl- edge of local language was unequal. Some of the earliest explorers had lived for a time in the Red Sea area and spoke Arabic (Isenberg, Rochet d’Héricourt). Isenberg even claimed to have an elementary knowledge of Amharic, Oromo, and Afar.27 Harris and Kirk, from the Army of India, participated in an official embassy escorted by military personnel using interpreters. Johnston had previously been in India and seems to have spoken Arabic. They all used local guides, who indicated toponyms and the names of resident groups. Even if the area was sparsely settled and meetings with the locals were infrequent, during some halts, which could be long, travelers exchanged information with inhabitants they may also have employed.28 These exchanges were indirect because few locals were able to Afars, Issas . . . and Djiboutians ▪ 129 use Arabic: someone capable of it is often very specially mentioned.29 A detailed analysis of informants’ motivations and of the local meanings carried at the time by denominations is not possible, partly because of the few existing studies;30 the approach we are suggesting here will perhaps allow new research. Our analysis of travelers’ descriptions retains the ethnic names they used. Even if they remind us of present-day usages, any continuity of meaning cannot automatically be assumed and must rather be clearly demonstrated so as to avoid anachronism. Isenberg talks about several ensembles (Danakil, Somal, Arab, Galla) and tribes. Among the latter, he met on his way We’ema, Mudaitu, Ad Alli, Galeila, and Burhanto. He mentions also Debne, who were concluding a conflict with Mudaitu, where they were helped by Arabs who came from Aden. He shows an interesting situation: “The We’ema Danakil maintain about 100 Somal bow-men, who have been taken from various Somal tribes, and are now naturalized among them: they still preserve, however, their Somal tongue, and marry among themselves, without intermixing with the Danakils.” If he sees the We’ema as a part of Danakil, it is a different story for the Mudaitu: “the shore [of the Awash] to the right is inhabited by the Allas, Ittoos, and Mudaitus; and to the left, by the Danakils.”31 Four months later, Rochet d’Héricourt distinguished two main groups: Saumalis and Danakiles, who exchange their grazing pasture according to rains, and claimed that “this mutual need maintains usually good harmony between those two large tribes.”32 He distinguished kabile inside Danakil of Adel: Ad-Ali, Assouba, Débenet, Débenet-Buema, Déniserra, Achemali, Takahides, and Hasen-Maras or Modeïtos, who lived in Awsa. “Bédouins of ras Bidar’s kabile are a mix of Débenets, Asouba, Hasen-Maras”33 and “some Asoubas, Débenets and Hasen-Maras are mixed with real Takahides.”34 This was partly explained by the fact that “all inhabitants of the Adel kingdom speak the same dialect . . . : this community of language is the main link of their nationality.”35 During his second trip, three years later, he encountered Mahamet-Ibrahim-Loéta, head of the Debenets and signaled that “Harraris belong to the Saumalis race.”36 Harris talks about “all the tribes of Danakil, Eessah, Somauli and Mudaïto.”37 However, while maintaining the Mudaïto’s specificity, whose “capital city” is Awsa, he divides them into Assa-himéra, Issé-hiraba, Galeya, Dar, and Koorha. He sometimes integrates the Eesahs into the Somauli and 130 ▪ Simon Imbert-Vier speaks about “Aboo Bekr,38 of the Somauli tribe Aboo Salam.”39 The Adrussi, part of the Debeni—themselves a subset of Danakil—were under the authority of Tadjoura’s sultan, “Lohaïta ibn Ibrahim, Makobunto, Akil, or chief of the Debeni and a section of the Eessah, asserting supremacy over Gobaad, as a portion of his princely dominions.”40 This chief had taken control of the caravan route fighting “the Galeyla tribe of Mudaïto,” who were “on non very amicable terms with the Danakil.”41 Kirk, who travelled with him, also distinguished Mudaïtus from Danakil. If none of these authors use the identifier Afar, is it because their Arabic-speaking interpreters translated it into the Arabic Danakil—which would be a confirmation of their way of communication— or because informants did not use that term locally? In any event, Johnston was the first to identify Danakil with Affah and to mention that Abyssinians called them Adal.42 He also mentions the Debenee and the Wahamah and Muditee of Owssa. He indicates the Issah Soumaulee as inhabitants of the South of the Gulf up to the territory of Wahama Dankalli43 and specifies that “a great portion of the Issah Soumaulee acknowledged Lohitu as their chief, and bore the Debenee mark upon their breast. . . . Half of the Wahama tribe . . . were actually Issah Soumaulee.”44 He concludes that “at the present day, the Dankalli and Soumaulee are distinct”45 but share a common origin. He also signals another identity change, with the “Assobah Galla, who . . . are now, however, considered to be a Dankalli tribe.”46 He also indicates the presence of mixed people who claimed multiple identities. This first set of travelers’ observations also provides a view of political authority around the Gulf of Tadjoura in the 1840s that does not appear to coincide with ethnic or tribal identities. First, the country of Tadjoura and sea access; to the South-West was the Debné country headed by Lo’oyta who unified politically numerous groups; to the north-west, the Môdhatou’s Awsa; to the South, the Somali country. However, the territorial and human limits between these sets were blurred and fluctuating: they were perhaps “interstitial frontiers” as proposed by Igor Kopytoff.47 The many individual and collective allegiances depended on immediate events, seasonal transhumance patterns, and political circumstance. All the inhabitants shared the same way of life, pastoral and nomadic, the same cultural and social references, and practiced intermarriage. After a long period without narratives, five travels undertaken around 1880 were published at the same time the occupation of the Western Red Afars, Issas . . . and Djiboutians ▪ 131 Sea shore by Europeans began.48 Two of these travelers were crossing from Tadjoura, two from Assab, and the first accessed by Zeila in 1877. The variability of these itineraries seems to indicate that the political situation had become less stable along the established routes. Accounts are shorter and less expressive; more practical descriptions concentrate on itinerary details and costs. Even if the journeys were still an adventure for the travelers, they no longer represent the exploring of unknown territories but rather the working out of reliable means to cross them. The conditions of information gathering seem the same, except for the additional knowledge from previous travelers’ accounts, which are used as “cultural guide books” in giving meaning to descriptions and representations. Later travelers do not furnish any additional details about how they concretely obtained their information; their linguistic capacities seem comparable to those of their predecessors.49 Antonio Cecchi, leaving from Zeila, was the first to detail the internal organization of Somalis,50 particularly Isa who were found between Zeila and Herrer and divided “in three main tribes called Haber-Gerhais, HaberAual e Haber-el-Jalec . . . all sons of Ishac.”51 He talks also about the Uarsangali and Migertini living farther East. About Afars, he identifies two main groups, Devenekemena, toward Shewa, and Assaiamarà, toward the sea. He distinguishes “Assaiamarà full blood”52 from Mudaitù and those of Anfari. He also insists on the similar way of life of Afars and Somalis.53 In 1882, Paul Soleillet, upon crossing from Tadjoura, described the Afar political structure: “the Reitta’s sultan . . . is allied to Tadjoura’s and Loïta, and these three sultans are feudataire of Mohammad Hanfalé, Haoussa’s sultan.”54 But there exist also “two great Afar tribes independent and salvage between salvages”:55 Gallelas and Aissameras. He also mentions inter-marriages between Afars and Çomalis Issas.56 In 1883, Pietro Antonelli travelled north from Assab, the first European to cross Awsa and the Awash lakes. He distinguishes Assaiamaras between the sea and Awash from Adoiamaras beyond the river. He mentions Modaito among Assaiamaras. Two years later, Emilio Dulio left also from Assab, but his description does not provide new information. When in 1886, Jules Borelli wished to travel to Shewa, “Issah-Somali and Danakil [were] at war” and caravans deserted “the road used before French installation in Obock”57 from Zeila, to go through Awsa. But this road was then closed by a conflict between Galela and Debenet.58 After 132 ▪ Simon Imbert-Vier failing to depart from Djiboutil, in the South of the Gulf, he was obliged to leave from Tadjoura. He identifies two entities (Issah and Danakil) and wonders whether “the authority exercised by Abou-Bakr over Issah-Somali is real; it is hard to understand when you know that this man is Dankali.”59 Among Afars, he distinguishes Mohammed Loëta, head of Adoïamara, Takaïli in Obock, Adali in Rehayto, and Assoba in Ambado. To sum up, at the beginning of the colonial settlement, according to these narratives, it seems that the representation of the inhabitants of territories around the Gulf of Tadjoura as divided into two groups (Somalis and Afars) was largely established. But these groups were not seen as fully homogenous; relations between groups, hierarchies, and political constructions were not well understood but seen as in motion. This description and analytical understanding of the local inhabitants continued during the colonial period, mostly in the area under colonial control. After the 1888 Anglo-French agreement, which opened the Southern road, and then the building of the Addis-Djibouti railway, the road toward Harar was favored by the French. The Northern area was neglected, and its inhabitants rarely described for a few decades. It was only at the beginning of the 1930s that the conquest of the Western parts of the colony started from the Dikhil post, created in 1928 on the “boundary line between Afars and Issas.” Identifications by the Administration Since World War II In December 1939, Hubert Deschamps, then governor of the CFS, made an important step in the assignations’ history in Djibouti: he published a circulaire60 asking commandants de cercle to switch their attention from groups identification—“at present mostly known”61—toward that of individuals by making a population census. Among the colony inhabitants, he distinguished three main sets: Issas and Adohyamara, the census of whom should be comprehensive,62 and the other Danakil, Assahyamara, for whom the census “should be postponed if it can cause incident.”63 For the nomads, the census would not be made individually but “with information sought from competent worthies”64 who were to be the references. The scope of this work was to mark “a new step for our ascendancy over inhabitants,” which will bring some “facilitation . . . of the political situation and security.”65 The time for discovery was over; the administration now wanted to Afars, Issas . . . and Djiboutians ▪ 133 adapt to social structures it could distinguish to use them.66 This enterprise was done the same way as earlier ones: mostly not a direct knowing, but a collection of information through intermediaries, that is, translators and worthies. Relations with informants were changed by the making of a colonial situation.67 The events of the war prevented the implementation of this ambitious project. However, in 1942, an officer who commanded the districts (cercles) of Ali Sabieh and Dikhil and participated in the political and military organization of the territory’s occupation, Édouard Chedeville,68 completed a genealogical census (recensement généalogique) of Issas. In this document, a few hundred pages in length,69 he tries to identify family lineages from chiefs’ declarations and to situate individuals inside it. Regularly updated at least up to the 1970s, this work constituted for more than 30 years a tool to identify Issas and to classify the French citizens among them.70 A first use of this census consisted in raising a poll tax on nomads, from 1944.71 The scope was not truly fiscal—with income being very low— but rather population control.72 Furthermore, the link between census, meaning identification, and right to stay on the territory appeared immediately: from 1944, the territory’s access was in theory forbidden to nomads out of census.73 This question became particularly important in the town of Djibouti. From 1947, we see in the colony’s Official Journal (Journal officiel) a new type of decision: expulsion orders detailing ethnical identifiers for the concerned persons. The study of the 10,000 decisions made between 1947 and 1963 provides clear evidence of the making of ethnical representations and distinctions. For instance, the identification of a Somali subset, Issaqs on the same level as Issas, emerges slowly from the agglutination of several groups becoming components of the new one.74 It was also during the 1950s that the name Afar was re-attributed to the inhabitants of the West and North,75 called Danakil/Dankali in almost all texts from the end of the nineteenth century. This denomination change marked the end of the conquest of Afar territories76 begun in the 1930s and symbolized their progressive incorporation into the Djiboutian space. The Afars’ areas were then administered, described, and the denominations of their representations became more accurate.77 After World War II the question of inhabitants’ identification carried a political stake linked to citizenship. In 1945, a Conseil représentatif was established, where the representation was not territorially but ethnically 134 ▪ Simon Imbert-Vier based, with two Afars, two Somalis, two Arabs, and six French up to 1950.78 Despite the French Fourth Republic Constitution of 1946, which made citizens of all nationals, the indigenous remained second-class voters. It was only the loi cadre or loi Defferre (23 June 1956) that unified French nationals: they all became full citizens and electors, including women. Elected representatives of the colony afterwards were all autochthonous and remained male. The question of a citizen’s identification, that is the distinction between national and foreigner, however, became central for the maintenance of the colonial situation, particularly because three referendums in 20 years were held regarding the territory’s independence. The French colonial administration had a difficult time in identifying its nationals, confronted as it was by the uncertainty of boundaries, the fluidity of identities, the mobility of the inhabitants, and the lack of civil registration.79 From the evidence of the distinction between French and Foreigners, administrators in charge of census lost themselves in taxonomies, trying to identify individuals.80 As early as 1945, one event showed that the question was unsolvable. After the Ethiopian consul complained about being expelled from a stand forbidden to “indigenous” during a sport meeting, a note explained that “Ethiopians are not indigenous but nationals of a neighboring country.”81 It truly demonstrates the impossibility of an objective distinction and the limit of assignation: there is no break between the inhabitants of the CFS and those of Ethiopia, Somalia, or Yemen; boundaries were not even negotiated at that time. Because it was impossible to respect the formal criteria provided by law for the attribution of the French nationality82 and all attempts to carry out objective description were doomed to failure, the identification of nationals was finally a political decision. Although the attribution of French citizenship was a judiciary prerogative, it was in fact done by the administration by using administrative and hence often arbitrary procedures.83 To do so, it essentialized the representations while continuing to make them evolve, always in the same process of African discourses reinterpreted and reused.84 In 1951, an “Autochthonous inhabitants census commission” (Commission de recensement de la population autochtone du territoire) was created to establish the “identity of French autochthonous citizens” who “will receive an identity card.”85 Under cover of census, the scope was to distinguish French from foreigners among the local inhabitants. The commission, appointed with French worthies,86 examined only the files accepted by Afars, Issas . . . and Djiboutians ▪ 135 officials in charge of their reception. It had to identify lineage and attach individuals to them. As before, assignation was done by applying a European filter to information provided by Africans. In the actual state of research, we can only imagine the conditions in which the so-called worthies proferred their advice, both in and outside the commission hearings. For the single town of Djibouti, this commission dealt with 15,009 files87 between 1951 and its end in 1955. It delivered 11,360 identity cards, of which 4,468 were not claimed, and rejected 3,649 files (24.3 percent).88 The last years of the French presence in Djibouti were characterized by the administration’s desperate attempts to find criteria allowing a “satisfactory” typology of inhabitants. The contradictions between a growing urban population, the impossibility of freezing identities and genealogies, the pressure of African leaders in favor of their clients, and the necessity of maintaining the territory under French sovereignty were insurmountable. Another element, after the creation of Somalia in 1960 and the “events” preceding the first referendum in 1966−67,89 was the tendency to favor the presence of Afars, defined as supporting the continued French presence, at the expense of Somalis, who were supposed to favor independence. All the rationalization failed; representations were decisive. In 1970−72 again, a “Population identification mission” (Mission d’identification de la population), operated by military personnel, created files for 120,000 inhabitants older than 15 years of age.90 It operated by direct physical identification of the inhabitants, without go-between, and tried to infer their nationality even if it was not its official function since it was a judiciary prerogative. At the end of the mission, its leader, the former General and representative of the CFS to French Assemblée nationale (1951−56) Edmond Magendie, explained the patent ideological implications of this process: It is not without a great relief that the mission’s head has acted that at the end of the mission’s works, conducted objectively and without precon- ceived ideas, . . . the assessment of the estimations here presented corroborates the results of the March 1967 referendum. By adding the Europeans votes to those of Afars and Arabs, convinced supporters of French presence, the 60% of affirmative votes are found.91 The identification of Somalis with independence supporters is thus demonstrated and legitimated by the “scientific” study of the population. This note is 136 ▪ Simon Imbert-Vier exemplary of how over-determination of elements from local reality led to ethnic essentialization while ignoring individual views and preferences. Using Identities Today Since Djiboutian independence, political equilibrium— established practically within the unique presidential party—is presented ethnically: for instance the Prime Minister is always identified as Afar. If the police and identity control system is maintained without break, legitimacy is sometimes recomposed92 to guarantee continuity of the political personnel and its access to State resources.93 In the 1990s, an armed opposition movement identified itself with the Afars; it is also because of their “Afar-ness,” making them dissident, that northern civilian inhabitants have been exposed to the violence of governmental troops,94 necessarily Somali, during the “reconquest” of the territory in 1994. This opposition movement remains loyal to the notion of the Djiboutian nation: it claims to seek better national integration, not independence or the making of a “Great Afaria.”95 As a militant said in 1992: “We don’t want to catch the Issas, just an equal share with them.”96 In 2001, the movement tried to shed its “tribal connotation of ‘Afar rebellion,’”97 but its leader Ahmed Dini continued to defend Afars interests when, in June 2002, he denounced the creation of Arta’s district as “a political operation, an economic operation and a tribal expansion operation for Issas’s profit.”98 In 2004, Mohamed Kadamy still asserted that “Afars have never been so put out in this country.”99 The identity claim is used by political leaders to mobilize supporters in order to legitimate access to State resources. Regular denunciation of “tribalism” since the 1950s confirms a contrario the continuity of ethnic representations and the persistence of their usefulness in political discourse. Another application of identity categories occurred in 2003 with the expulsion from Djiboutian territory of 80,000 refugees called “foreigners in irregular situation,” nearly 15 percent of the country’s inhabitants.100 The national, and not ethnic, identity was publicly invoked to justify the expulsions, but the initial attribution of Djiboutian citizenship was determined on the basis of criteria elaborated during colonial times,101 since the one who “is Djiboutian, with its minor children, is the person of age on 27 Afars, Issas . . . and Djiboutians ▪ 137 June 1977, who, because of its birth in Republic of Djibouti, was French within the laws then applicable upon the territory.”102 Under cover of “modern” identities, the colonial categories are still mobilized.103 The examples presented in this article can help in understanding how some Djiboutian identities have been made up, modified and used. Born in the confrontation between African descriptions and European interpretations, they finish in political conflicts. Indeed, the evolution of identifications proposed since the nineteenth century is mobilized today in individual relations and political allegiances. Besides the resources they represent for individuals, identities have been used by political regimes for they own needs.104 At the creation of an indepen- dent state around the Gulf of Tadjoura in 1977, contradictions were sustained by the continuity of representations and categories.105 Although the nation- building project would like to create a Djiboutian identity, djiboutienneté,106 and despite the crystallization produced by administrative practice, ethnical identities are today still essentialized, used, adapted, recomposed and manipulated according to concrete situations and actors’ needs. PUBLISHED NARRATIVES, IN ORDER OF TRAVELS Isenberg, Karl Wilhelm and Krapf, Ludwig, Journals (London: Frank Cass & Co., 1968). Rochet d’Héricourt, C. F. Xavier, Voyage sur la côte orientale de la mer Rouge, dans le pays d’Adel et le Royaume de Choa (Paris: Arthus Bertrand, 1841). Harris, W. Cornwallis, The Highlands of Æthiopia, Described During Eighteen Months’ Residence of a British Embassy at the Christian Court of Shoa, 3 vols. (London: Brown Green and Longman 1844). Kirk, R., “Report on the Route from Tadjoura to Ankobar, Traveled by the Mission to Shwá, under Charge of Captain W. C. Harris, Engineers, 1841 (Close of the Dry Season),” Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, 12 (1842): 221–38. Johnston, Charles, Travels in Southern Abyssinia, Through the Country of Adal to the Kingdom of Shoa, 2 vols. (London: J. Madden and Co., 1844; Westmead: Gregg International, 1969). Rochet d’Héricourt, C. F. Xavier, Second voyage sur les deux rives de la mer Rouge, dans le pays des Adels et le Royaume de Choa (Paris: Arthus Bertrand, 1846). 138 ▪ Simon Imbert-Vier Cecchi, Antonio, Da Zeila alle frontiere del Caffa, 3 vols. (Roma: Società Geografica Italiana, 1886). Soleillet, Paul, Obock, le Choa, le Kaffa. Récit d’une exploration commerciale en Ethiopie (Paris: Dreyfous, s.d. 1886). Antonelli, Pietro, “Il mio viaggio da Assab allo Scioa,” Bolletino della Società geografica italiana (1883): 857– 80. Dulio, Emilio, “Dalla baia di Assab allo Scioa per l’Aussa,” Cosmos (1886 –1888): 102–18, 163–72, 272–78, 283–356. Borelli, Jules, Ethiopie méridionale, journal de mon voyage aux pays Amhara, Oromo et Sidama (Paris: Ancienne maison Quantin, 1890), gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/ 12148/bpt6k104072f. NOTES Previous versions of this research have been presented at the 7th Iberian Congress of African Studies of 2010 in a panel organized by Itziar Ruiz-Gimenez and Alexandra Dias and at a CEMAf seminar at Aix-en-Provence in 2012. I would like to thank the participants, Pierre Guidi and the anonymous referee for their remarks, and Damien Joron, James De Lorenzi, and Lee Cassanelli for their help in translating the text to English. 1. French Territory of Afars and Issas. This result was contested because of the numerous instances of fraud organized by the administration. The repression of consecutive riots caused 31 deaths among the inhabitants. More than 4,000 persons were expelled from the territory. Vote manipulation remains constant in Djibouti. According to Roland Marchal: “Elections in Djibouti have been without much surprise since independence. . . . The greater the distance from the capital city, the higher the electoral participation and the support for the president.” Marchal, Roland, “Djibouti (Vol 2),” Africa Yearbook, ed. Andreas Mehler, Henning Melber, Klaas van Walraven (Brill Online, 2011) http://www.brillonline.nl/subscriber/entry?entry=ayb_ayb2005-COM-0032 (accessed 25 July 2011). 2. “Dans le but de faire disparaître dès le premier jour de l’Indépendance toute trace de tribalisme et tout danger de division ethnique, les responsables du nouvel Etat ont emprunté à la capitale du pays . . . le nom Afars, Issas . . . and Djiboutians ▪ 139 prestigieux de Djibouti pour le donner à la République.” Mohamed Aden, Sombloloho Djibouti - La Chute du président Ali Aref (1975–1976) (Paris-Montréal: L’Harmattan, 1999), 12. 3. On the political process leading to independence, see Fantu Agonafer, Djibouti’s Three-Front Struggle for Independence: 1967–77 (PhD diss., University of Denver, 1979); Philippe Oberlé; Pierre Hugot, Histoire de Djibouti - Des origines à la République (Paris, Dakar: Présence Africaine, 1985, 1996); Ali Coubba, Le mal djiboutien: rivalités ethniques et enjeux politiques (Paris: L’Harmattan, 1995). 4. For a more detailed analysis of the colonial situation at independence time, see Simon Imbert-Vier, “Après l’Empire: Violences institutionnelles dans le Djibouti colonial tardif,” French Colonial History 13 (2012): 91–110. On the Barrage’s history and stakes, see Simon Imbert-Vier, “Il Barrage di Gibuti, frontiera inutile o fucina sociale,” Storia urbana 128 (2010): 109−27. 5. For the first referendum about independence, on 28 September 1958, the Vice-President of the territory’s Conseil de gouvernement and deputy at the French National Assembly, Mahmoud Harbi, appealed to reject the maintenance of French presence. Despite vote’s manipulation, the “yes” officially only gathered 75 percent of votes, the lowest result in the whole Union française except Sekou Toure’s Guinea. The territorial Assembly was then dissolved. Mahmoud Harbi died in 1960. 6. Somalia was ideologically built upon the project of uniting all “Somalis” in the “Greater Somalia,” proposed by Lord Bevin in 1946. Its Constitution set the scope of “reunification” of “five Somalias” symbolized by the five points of its flag’s star, that is the incorporation of French Somaliland, Ethiopian Ogaden, and Kenya’s Northern District. 7. In 1967, Afars replaced all Somali dockers (mostly Issaqs), who took the places of Arabs in 1957. 8. Simon Imbert-Vier, Tracer des frontières à Djibouti. Des territoires et des hommes aux XIXe et XXe siècles (Paris: Karthala, 2011), 101−24. 9. Imbert-Vier, Tracer des frontières à Djibouti, Chapter 4. 10. From an Arabic name, plural of Dankali. 11. Great grandson of an important merchant who is the last “pacha” of Zeila under Egyptian rule (Abu Bekr) and grandson of the first “bey” of the town if Djibouti (Burhan), he is part of the family of the Afar “sultan” of Tadjoura. He was Vice-President of the CFS Governmental Council from 1960 to 1966 and Head of the TFAI Government from 1967 to 1976. 140 ▪ Simon Imbert-Vier 12. However, many other “ethnic” identities are claimed by Djibouti’s inhabitants: Somalis like Issaq or Gadabursi, but also Arabic, Oromo, Ethiopian orthodox, French, Corsican, etc. See Absieh Omar Warsama and Maurice Botbol, “Djibouti: les institutions politiques et militaries,” La Lettre de l’océan Indien (1986): 12−15. 13. In an encounter in August 2007, Abdallah D., whose mother and language are Somali, still defines himself as Afar and opponent in the same time. 14. Fredrik Barth, dir., Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: the Social Organization of Culture Difference (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, London: George Allen & Uwin, 1969); Jocelyne Streiff-Fénart and Philippe Poutignat, Théories de l’ethnicité (Paris: PUF, Le Sociologue, 1995, 1999). 15. For instance, about “Somali Bantus,” see Lee V. Cassanelli, “Social Construction of the Somali Frontier: Bantu Former Slave Communities in the Nineteeth Century,” in The African Frontier: the Reproduction of Traditional African Society, ed. Igor Kopytoff (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987), 216−38; Ken Mankhaus, “The Question of Ethnicity in Somali Studies. The Case of Somali Bantu Identity,” in Milk and Peace, Drought and War. Somali Culture, Society and Politics, ed. Markus Hoehne and Virginia Luling (London: Hurst and Company, 2010), 87−104. 16. On this point, I refer to the foundation work: Jean-Loup Amselle and Elikia M’Bokolo, ed., Au cœur de l’ethnie (Paris: La Découverte, 1985, 1999). 17. “les différents groupes s’enchevêtrent et les diverses dénominations se superposent souent les unes aux autres pour s’appliquer aux mêmes individus.” Robert Ferry, “Groupes de descendance et groupes territoriaux en pays Afar,” in Actes de la Xe Conférence des Études Éthiopiennes, ed. Claude Lepage (Paris: SFEE, 1994), 465−75. As a military man, Robert Ferry had been a few times in CFS. In the 1950s, he worked there for the SDECE (intelligence service). He was also involved in the Mission d’identification at the beginning of the 1970s. 18. Gérard Noiriel, “L’identification des citoyens. Naissance de l’état civil républicain,” Genèses 13 (1993): 3−28. 19. Isabelle Grangaud and Nicolas Michel, dir., “L’identification, des origines de l’islam au XIXe siècle,” Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée 127 (2010), remmm.revues.org/6548. 20. François-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar Histoire de l’Afrique du Sud (Paris: Seuil, coll. L’Univers historique, 2006), 65, 100. Afars, Issas . . . and Djiboutians ▪ 141 21. Charles Tilly writes: “category formation is itself a crucial political process. Category formation creates identities.” See his The Politics of Collective Violence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 29. For Jean-François Bayart, L’État en Afrique (Paris: Fayard, 1989, 2006), 15, 84, ethnicity doesn’t help in understanding political constructs in Africa, it “is only a scope amongst other of social and political conflict” [un cadre parmi d’autres de la lutte sociale et politique]. For a study of a similar process in a nearby context, see Uoldelul Chelati Dirar, “Colonialism and the Construction of National Identities: The Case of Eritrea,” Journal of Eastern African Studies 1, no. 2 (2007): 256−76. 22. European discourses about Djibouti were studied by Jean-Pierre Diehl, Le regard colonial (Paris: Régine Desforges, 1986) and Marie-Christine Aubry, Djibouti l’ignoré, récits de voyages (Paris: L’Harmattan, 1988). A first analysis of the francophone Djiboutian literature about the colonial situation is proposed by Abdourahman Yacin Ahmed, “Djibouti au centre du discours littéraire,” in Djibouti contemporain, ed. Amina Saïd Chiré (Paris: Karthala, 2013), 317−48. 23. Pierre L. van den Berghe, State Violence and Ethnicity (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 1990), 3, 9, suggests that modern States are using administrative and industrial coercive means to “accentuate the disparity of power between the state and its citizenry” with the scope of “nation killing” ethnic groups. 24. The list of these publications is above. Richard Burton entered Harar from Zeila in 1854−55, but he used a southern road far from the Gulf of Tadjoura. See Richard Burton, First Footsteps in East Africa or an Exploration of Harar (London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1856). 25. “géographie de conquête.” See Isabelle Surun, Géographies de l’exploration La carte, le terrain et le texte (Afrique occidentale, 1780-1880) (EHESS, PhD diss., 2003), 577. 26. It was the Shewa administrative limit up to its disappearance in 1992. 27. His cotraveler, Krapf, translated the Bible in Oromo in 1875. 28. Johnston also evokes the practice of “women hiring” during those halts. 29. Even if those texts do not evoke double translations, first from a European language to Arabic, then from Arabic to a vernacular language, one can guess its existence. 30. Regarding the political situation in the “Afar area” in nineteenth century, see Didier Morin, Dictionnaire historique afar (1288 –1982) (Paris: Karthala, 142 ▪ Simon Imbert-Vier 2004) and Aramis Houmed Soulé, Deux vies dans l’histoire de la Corne de l’Afrique: Mahamad Hanfare (1861–1902) et Ali Mirah Hanfare (1944), Sultans Afars (Addis Abeba: CFEE, 2005, 2012), who don’t interrogate the category afar. For more recent time up to independence, see Kassim Shehim and James Searing, “Djibouti and the Question of Afar Nationalism,” African Affairs 79, no. 315 (1980): 209−26. For Somalis, the analysis is renewed in Markus Hoehne and Virginia Luling ed., Milk and Peace, and Lidwien Kapteijns, “I. M. Lewis and Somali Clanship: A Critique,” Northeast African Studies 11, no. 1 (2010): 1−23. 31. Isenberg and Krapf, Journals, 41, 53. 32. “ce besoin réciproque maintient ordinairement la bonne harmonie entre ces deux grandes tribus,” Rochet d’Héricourt, Voyage sur la côte orientale de la mer Rouge, 80. 33. “les Bédouins de la kabile du ras Bidar sont un mélange de Débenets, d’Asouba, d’Hasen-Maras,” Rochet d’Héricourt, Voyage sur la côte orientale de la mer Rouge, 114. 34. “des Asoubas, des Débenets et des Hasen-Maras sont mêlés aux Takahides proprement dits,” Rochet d’Héricourt, Voyage sur la côte orientale de la mer Rouge, 115. 35. “tous les habitants du royaume d’Adel parlent le même dialecte . . . : cette communauté de langage est le principal lien de leur nationalité,” Rochet d’Héricourt, Voyage sur la côte orientale de la mer Rouge, 118. 36. “les Harraris appartiennent à la race des Saumalis,” Rochet d’Héricourt, Second voyage sur les deux rives de la mer Rouge, 262. 37. Harris, The Highlands of Æthiopia, 180. 38. About Abu Bekr, see Marc Fontrier, Abou-Bakr Ibrahim, Pacha de Zeyla Marchand d’esclaves (Paris: Aresae, L’Harmattan, 2003) and note 11 supra. 39. Harris, The Highlands of Æthiopia, 31. 40. Harris, The Highlands of Æthiopia, 151. 41. Harris, The Highlands of Æthiopia, 177. 42. Johnston, Travels in Southern Abyssinia, 12. 43. Johnston, Travels in Southern Abyssinia, 108. 44. Johnston, Travels in Southern Abyssinia, 240. 45. Johnston, Travels in Southern Abyssinia, 322. 46. Johnston, Travels in Southern Abyssinia, 13. Afars, Issas . . . and Djiboutians ▪ 143 47. Igor Kopytoff, “The Internal African Frontier: the Making of African Political Culture,” The African Frontier, 3−84. 48. After Rubattino bought Assab in 1880, the harbor was occupied by Italy in 1882. In Obock, where some French traders were installed since 1881, a coal deposit and a colony were created in 1884. The United Kingdom sent a representative to Zeila in 1885 and declared a protectorate in 1887. 49. Borelli signals he tried to familiarize himself with amharigna. 50. Besides his journey narrative Da Zeila, Antonio Cecchi published two “ethnographic” articles: “Le popolazioni della regione di Assab. I Danakili (Afar),” Nuova antologia rivista di scienze, lettere e arti, Roma, anno 20, 2e seria, vol. 49 (della racolta v. 79), fasc. 1 (1885): 523−32; and “Le popolazioni della regione di Assab. I Somali,” Nuova antologia rivista di scienze, lettere e arti, Roma, anno 20, 2e seria, vol. 53 (della racolta v. 83), fasc. 17 (1885): 281−93. In 1877, he participated in an expedition headed by Sebastiano Martini and financed by the Società geografica italiana. 51. “in tre grandi tribù, chiamate: Haber-Gerhais, Haber-Aual e Haber-el-Jalec ... tutti figli di Ishac,” Cecchi, Da Zeila alle frontiere del Caffa, 39. 52. “Assaiamarà pure sangue.” Cecchi, Da Zeila alle frontiere del Caffa, 98. 53. Cecchi, Da Zeila alle frontiere del Caffa, 102. 54. “Le sultan de Reitta . . . est allié des sultans de Tadjoura et de Loïta et ces trois sultans sont feudataires de Mohammad Hanfalé, sultan de Haoussa,” Soleillet, Une exploration commerciale en Ethiopie, 3. 55. “deux grandes tribus afars indépendantes et sauvages parmi les sauvages,” Soleillet, Une exploration commerciale en Ethiopie, 60. 56. Soleillet, Récit d’une exploration commerciale en Éthiopie, 65. 57. “les Issah-Somali et les Danakil sont en guerre”; “la route pratiquée avant l’affermissement des Français à Obock,” Borelli, Ethiopie méridionale, 3. 58. Borelli, Éthiopie méridionale, 14. 59. “l’autorité qu’Abou-Bakr exerce sur les Issah-Somali est réelle; elle se comprend mal quand on sait que cet homme est Dankali,” Borelli, Ethiopie méridionale, 8. 60. Aix-en-Provence, ANOM, CFS, 3F2 Circulaire 12 December 1939. 61. “maintenant connus dans leurs grandes lignes,” Circulaire 12 December 1939. 62. “Because of the difficulty of distinguishing French Issas from Italians ones, all ‘sub-groups’ having representatives on our territory will be included in 144 ▪ Simon Imbert-Vier the census” “En raison de la difficulté de discriminer les Issas français des Issas italiens, toutes les sous-fractions qui ont des représentants sur notre territoire seront recensées intégralement,” Circulaire 12 December 1939. 63. “devra être ajourné dans les cas où il pourrait amener des incidents,” Circulaire 12 December 1939. 64. “par renseignements demandés aux notables compétents,” Circulaire 12 December 1939. 65. “un nouveau stade de notre emprise sur les populations,” “facilités . . . aux points de vue de la situation politique et de la sécurité,” Circulaire 12 December 1939. 66. Hubert Deschamps finished his career as professor in African History at the Sorbonne University in Paris. He theorized principles of colonial administration, see Hubert Deschamp, “Et maintenant, lord Lugard?” Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 33, no. 4 (1963): 293−306. 67. Georges Balandier “La situation coloniale: approche théorique,” Cahiers internationaux de Sociologie. 11 (1951): 44−79, completed in Sociologie actuelle de l’Afrique Noire (Paris: PUF, 1955, 1963). See also Maxime Rodinson, “Israël, fait colonial?” Les Temps modernes 253 (1967): 17−88. 68. Édouard Chedeville, born in 1905, after studying in Saint-Cyr high military school, was sent to Tunisia, AOF, Mauritania, and Morocco, then CFS from 1938 to 1943. Prosecuted for murders committed during the war, he was finally discharged in 1950. He was appointed as Afar language teacher in 1967−69 by the École nationale des langues orientales vivantes (actually Inalco) in Paris. 69. A copy of 1960, in four volumes corrected in 1970, can be found in ANOM (fonds privés, Papiers Bertin PA 351). There is also a version “developed” in 1966 together with a 1965 “Fractionnement des Issa, Issack, Gadaboursi” (ANOM, fonds privés, Papiers Ferry, 49 PA). 70. “It was enough in order to constitute voters lists, to update this census and to deduce the list of living individuals of more than 21 years” “Il a suffit, pour obtenir les listes électorales de mettre à jour ce recensement et d’en tirer la liste des individus vivants ayant plus de 21 ans.” Fontainebleau, CAC, 940163/78, report of the election control commission, 19 March 1967. 71. It was suppressed in 1949 with the creation of the “franc Djibouti.” Afars, Issas . . . and Djiboutians ▪ 145 72. “Indigenous are more affable since they have mostly been registered into census” “Les indigènes sont d’autant plus affables qu’ils se savent en majeure partie recensés.” (ANOM, CFS, 1E5 et 1E6/1-5 Tadjoura, “Rapports mensuel, journal de poste - 1930-1945,” report of February 1944). 73. “L’accomplissement des formalités de recensement vaut autorisation de séjour . . . Ceux qui refusent de s’y plier ne sont pas “insoumis,” mais l’accès de (sic) territoire doit leur être interdit.” (ANOM, CFS, 1E6/4-7 Tadjoura, “Correspondance 1944-1945,” letter from governor [23 August 1944]). 74. Called “Abar-Awal,” “Abar-Jallo,” “Abar-Yonis” . . . in the documents. The same evolution is noticed with the delivering of identity cards. It is said actually that Issa would be a subset of Dir, a Somali branch like Issaq (Piguet [François] [1998], Des nomades entre la ville et le sable. Sédentarisation dans la Corne de l’Afrique, Karthala/IUED, Paris). 75. The first mention I found is in a report from the administrator of Tadjoura, dated January 1955 (ANOM, AE6/4-7, rapport du 4e trimestre 1954). 76. Armed fights confronting French military and militia to inhabitants arose up to the 1940s, with two paroxysms in 1935 and 1943. 77. From 1930 to 1939, the northern administrative area was called cercle des Adal. According to an administrator, it is an “historic word used to designate inhabitants of areas now forming the CFS” “mot historique qui servait à désigner les populations établies sur les territoires qui forment actuellement la Côte française des Somalis” (ANOM, 3G3, “Correspondance 1923–1955,” letter from administrator Jourdain [16 December 1930]). 78. Colette Dubois and Jean-Dominique Pénel, Saïd Ali Coubèche, la passion d’entreprendre: témoin du XXe siècle à Djibouti (Paris: Karthala, 2006), 59−64. 79. The indigenous registration office, created in CFS in 1935, was extended to internal parts of the colony in 1951. About the creation of registration office, see Gérard Noiriel “L’identification des citoyens.” 80. Administrators’ difficulties are well explained in a census Compte-rendu d’exécution by the Djibouti commandant de cercle (P. Roser), 28/1/1957 (ANOM, CFS, 3F2). 146 ▪ Simon Imbert-Vier 81. “les Ethiopiens ne sont pas des indigènes mais les ressortissants d’un pays voisin.” AD Nantes, “Ambassade à Addis Abeba” B26, note of 16 February 1945. 82. To be considered as French native (i.e., by attribution), one must usually prove its birth in CFS, eventually from parents themselves born there. The absence of registry office makes these events impossible to demonstrate. See Simon Imbert-Vier, Tracer des frontières à Djibouti, 322−29. For a description of similar process in Gulf countries, see Claire Beaugrand, “Émergence de la ‘nationalité’ et institutionnalisation des clivages sociaux au Koweït et au Bahreïn,” Chroniques yéménites 14 (2007): 89−104. 83. In 1950, the FOM (Overseas) ministry noticed that “the difficulty we are facing is that it is impossible for an administrative commission to recognise or attribute French citizenship. To get round this obstacle, I think we should not mention nationality and to suppose it every time an attentive exam of the situation will let think it possessed” “la difficulté à laquelle nous nous heurtons, c’est qu’il n’est pas possible à une commission administrative de reconnaître ou d’attribuer la nationalité française. Pour tourner cet obstacle, je crois qu’il conviendrait de ne pas faire mention de la nationalité et de la supposer acquise, chaque fois que l’examen attentif des cas particuliers justifiera une telle détermination.” (ANOM, CFS, 3F2, letter to governor [23 December 1950]). An anonymous note, probably of 1951, explains that “all individuals registered, married, head of family of whom all parents (ascents and descents) have their address in CFS did receive ‘ipso facto’ an identity card. Their declaration of birth in Djibouti has been presumed true, without any enquiry” “tous les individus recensés, mariés, chefs de famille dont toute la famille (ascendant et descendants) sont domiciliés en CFS ont ‘ipso facto’ reçu une carte d’identité. Leur déclaration de naissance à Djibouti a été présumée exacte, sans aucune enquête.” (ANOM, CFS, 4F2). 84. In 1966, H. Beaux, head of territorial affairs, details mode of a census: “We check the belonging of tribes living actually on our territory to ethnic groups and fractions considered by customary law and our previous enquiries as only originating from CFS. . . . We will be able, at the end of those operations, to know with a great estimate [sic] the exact number of the local population and specially the one of inhabitants originating from the territory” “On vérifie l’appartenance des tribus résidant Afars, Issas . . . and Djiboutians ▪ 147 momentanément sur notre territoire aux ethnies et aux fractions considérées par la coutume et par nos enquêtes antérieures comme seules originaires de la Côte française des Somalis. . . . Nous serons en mesure, au terme de ces opérations, de connaître avec une très grande approximation (sic) le chiffre de la population locale et plus spécialement celui de la population originaire du Territoire.” (ANOM, CFS, 13A1/3 [30 April 1966]). 85. “identité des autochtones citoyens français ( . . . qui) recevront une carte d’identité.” Local decision no. 49, 17 January 1951, JO CFS. The concept of autochthonous citizen (citoyen autochtone) doesn’t exist legally. 86. “deux issas, deux danakils, un gadaboursi, un abéraoual et deux arabes” for Djibouti, “two worthies took into the concerned fraction” “deux notables pris dans la fraction recensée” for the rest of the territory. 87. There were less than 40,000 inhabitants in the town of Djibouti circa 1950. 88. ANOM, 3F2 Démographie. 89. After the exhibition of banderole claiming for independence during a stay of General de Gaulle in August 1966, the territory entered in a cycle of demonstration-repression, causing numerous deaths. A new wave of demonstrations and repression followed the rejection of independence by a referendum in March 1967. The administration carried out many expulsions, then built a barrage around the Djibouti’s town, officially to control migrations. 90. These files are still used actually by the Djiboutian authorities. 91. “Ce n’est pas sans un profond soulagement que le chef de mission a pris acte du fait qu’au terme des travaux de la mission conduits en toute objectivité et sans idée préconçue . . . le bilan des estimations présentées ici corrobore les résultats du Référendum de mars 1967. En apportant en effet l’appoint des suffrages européens à ceux des Afars et des Arabes, partisans convaincus de la présence française, les 60% de réponses affirmatives se retrouvent,” Rapport Magendie (16 February 973), 14, note 1 (copies of this text can be consulted in ANOM, PA 351; ANOM Contrôle 1270; CAC 940163/28 and 940163/78). See also the same analysis in Robert Tholomier, under the pseudonym of Robert Saint-Véran, A Djibouti, avec les Afars et les Issas (Cagnes-sur-mer: Tholomier, 1977): 41. 92. Between the vote of independence in June 1977, and the first elections in 1981, the number of registered voters diminish by 8 percent (from 148 ▪ Simon Imbert-Vier 105,952 to 97,964 according Ali Coubba, Le mal djiboutien). On that matter, see also Simon Imbert-Vier, Il Barrage di Gibuti. 93. For Abdourahman Yacin Ahmed, with a reference especially to the novels of Abdourahman Ali Waberi, “Institutionalization of tribalism creates a competition between ethnic groups inside the State. Clans perceive the State as a stake between them and a sharing place where everybody tries to obtain the most important share of the cake. . . . The government making of respects this ‘tribal equilibrium’. . . . Every ethnic group gets a representative in the government” “L’institutionnalisation du tribalisme instaure une compétition entre les ethnies au sein de l’État. Les clans perçoivent en effet l’État comme un enjeu entre eux et un lieu de partage où chacun cherche à obtenir la plus importante part du gâteau. . . . La constitution du gouvernement respecte cet ‘équilibre tribal’. . . . Chaque ethnie a un représentant dans le gouvernement” (“Djibouti au centre du discours littéraire,” in Djibouti contemporain, 332). 94. According Le Monde (5 March 1994), the opposition denounced rapes, the execution of 176 civilians, and massive transfer of inhabitants. 95. According Youssif Yacine, “program of no Afar political organisation mentions the Great Afaria idea” “aucun programme des organisations politiques afar ne mentionne l’idée de grande Afarie.” Dernières Nouvelles d’Addis 27 (1-3/2002). 96. “Nous ne voulons pas chasser les Issas, mais avoir la même part qu’eux].” Jean Hélène, “Djibouti: la guerre en pays afar,” Le Monde (29/1/1992). The Front pour la restauration de l’unité et la démocratie (Frud) launch an armed insurrection in November 1991. It controlled most of Northern and Western part of the country up to a governmental counter-offensive in July 1993. 97. Interview of Ahmed Dini, Dernières Nouvelles d’Addis 27 (1-3/2002). 98. [une opération politique, une opération économique et une opération d’expansion territoriale tribale, au bénéfice des Issas], interview of Ahmed Dini, Dernières Nouvelles d’Addis 30 (7-9/2002). An analysis of the contemporary relation between Afars and Issas, particularly in Ethiopia, can be found in Yasin Mohamed Yasin, “Trans-Border Political Alliance in the Horn of Africa: the Case of the Afar-Issa Conflict,” in Borders & Bordelands as Resources in the Horn of Africa, ed. Dereje Feyissa and Markus Virgil Hoehne (London: James Currey, 2010), 85−96. 99. “les Afars n’ont jamais été autant marginalisés dans ce pays.” Dernières Nouvelles d’Addis 41 (5-7/2004). Afars, Issas . . . and Djiboutians ▪ 149 100. Dernières Nouvelles d’Addis, no. 37 (9-11/2003); Le Monde (17/9/2003). 101. About French citizenship in colonial situation, see Yerri Urban, L’indigène dans le droit colonial français 1865–1955 (Paris: Fondation Varenne, 2011). 102. “est djiboutien, ainsi que ses enfants mineurs, l’individu majeur, au 27 juin 1977 qui, par suite de sa naissance en République de Djibouti, était français au sens des lois encore en vigueur sur le territoire.” art. 5 of the “Loi portant code de la nationalité djiboutienne,” no. 200/AN/81 (10/24/1981), www.presidence.dj/datasite/jo/1981/loi200an81.htm (accessed 15 May 2010). This rule is modified in 2004 by the law no. 79/AN/04 (10/24/2004), www.presidence.dj/datasite/jo/2004/ loi79an04.php (accessed 17 May 2010). 103. “The sovereign power of the Djiboutian state through the nationality law allows the marginalization of citizens. In Djibouti graduated citizenship emerges both from the practice of ethnic discrimination and also as a result of the nationality law. But these two elements should not be viewed as separate, as they overlap considerably,” Samson A. Bezabeh, “Citizenship and the logic of sovereignty in Djibouti,” African Affairs 110/441 (2011): 587−606. 104. In the 1960s, Somali nationalists described Afars as “Northern Somalis.” For an Afar militant, “la seule chose que l’on peut rapprocher de la notion ‘Afar’ est naturellement l’entité ‘Somali’” (Ali Coubba, Djibouti, une nation en otage [Paris: L’Harmattan, 1993], 42). At the opposite, for Pierre Oberlé, former French State employee in Djibouti, “un Issa ressemble davantage à un Afar qu’à un Somali de Mogadiscio” (Philippe Oberlé and Pierre Hugot, Histoire de Djibouti, 44). 105. Pierre L. van den Berghe, State Violence and Ethnicity, 11. 106. Ali Moussa Iye, Dernières Nouvelles d’Addis 37 (9-11/2003): 11.