A Quantitative Study of the Effects of a Summer Literacy Camp to

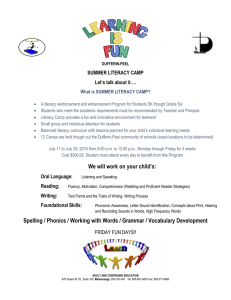

advertisement