Viking Age Shields: Gokstad Ship Burial Re-examined

advertisement

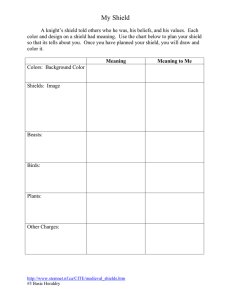

Arms & Armour ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/yaaa20 The Viking Age shields from the ship burial at Gokstad: a re-examination of their construction and function Rolf Fabricius Warming To cite this article: Rolf Fabricius Warming (2023): The Viking Age shields from the ship burial at Gokstad: a re-examination of their construction and function, Arms & Armour, DOI: 10.1080/17416124.2023.2187199 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/17416124.2023.2187199 © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 24 Mar 2023. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=yaaa20 ARMS & ARMOUR, Vol. 0 No. 0, Month 2023, 1–24 The Viking Age shields from the ship burial at Gokstad: a re-examination of their construction and function ROLF FABRICIUS WARMINGa,b aDepartment of Archaeology and Classical Studies, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden; bSociety for Combat Archaeology, Frederiksberg, Denmark The early find of the 64 Viking Age round shields from the Gokstad ship burial has almost singularly shaped our understanding of the construction and role of shields from this period. Despite their significance, however, the shield material has never been published in full nor been subjected to any substantial examination since their discovery in 1880. The current understanding of the shields is thus highly limited, tainted also in part by the preconception that they potentially represent ceremonial shields for the burial rite as well as assumptions of homogeneity. This preliminary study critically assesses these preconceptions and presents the results from a reexamination of the shield boards from the Gokstad ship burial. Despite their fragmented state, these artefacts significantly contribute to a more nuanced understanding of shield constructions of the Viking Age, especially when coupled with other well-preserved archaeological shield finds and the scholarly corpus available on such shields. As such, the preliminary findings of this paper offer new insights into the complexities of Viking Age shield technologies and their use in funerary rites, underlining the need for more comprehensive treatment of this material in the future. KEYWORDS burial, Viking age, Gokstad, ship, maritime, shields, technology, ceremonial Introduction Ever since its early discovery in 1880, the monumental ship burial at Gokstad in eastern Norway has remained a veritable icon and object of fascination for Viking Age scholars. Currently in the process of being re-located to a new building for the # 2023 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. DOI 10.1080/17416124.2023.2187199 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, and is not altered, transformed, or built upon in any way. The terms on which this article has been published allow the posting of the Accepted Manuscript in a repository by the author(s) or with their consent. 2 R. F. WARMING Viking Ship Museum in Oslo, the unusually rich and well-preserved archaeological material from Gokstad has yielded valuable knowledge regarding both mundane and high-status material culture of the Viking Age (c.750-1050 AD).1 For scholars interested in the Viking Age warfare, the archaeological material holds special significance, being arguably one of the main sources of data for shield technologies of this period. The remains of the reportedly 64 black and yellow painted shields uncovered at Gokstad are amongst the most well-preserved shields of the Viking Age and simply unparalleled in quantity in terms of a synchronous find from a single archaeological context. As such, these artefacts have significantly contributed to our understanding of the construction of Viking Age round shields. It is no exaggeration to say that the finds have almost single-handedly shaped our understanding of Viking Age round shields as a consequence of their degree of preservation as well as the early excavation and publication by Norwegian archaeologist Nicolay Nicolaysen in the late 19th century (Figure 1). Notwithstanding the early excavation date and general interest in the shields, however, there is much ambiguity surrounding the finds. Most importantly, it should be noted that the shields remain to be submitted to a comprehensive material culture study. Relatively little attention was actually paid to the shield material in Nicolaysen’s otherwise valuable publication of 1882, Langskibet fra Gokstad ved Sandefjord, which remains the main piece of literature on the Gokstad ship and the associated artefacts. Being primarily a catalogue, it contained only two half pages of 1. A reconstructive drawing of the Gokstad long ship from Nicolaysen’s 1882 publication. Drawing by Harry Schøyen. FIGURE THE VIKING AGE SHIELDS FROM THE SHIP BURIAL AT GOKSTAD 3 general notes on the shields as well as a rough sketch of a single hypothetical reconstruction out of the 64 shields that were found, leaving many issues relating their construction open to debate and interpretation.2 As will be seen, it is evident, too, that several important constructional details have been overlooked in previous publications. Further ambiguity has been added by four hypothetical reconstructions that were cobbled together for visual display around the time of Nicolaysen. The lack of documentation for the reconstruction process leaves much guesswork and room for misunderstandings, especially as the accuracy of the shields is highly questionable (see below). It is also clear that the received view of the Gokstad shields is tainted by previous interpretative tendencies in archaeology to label supposedly inexplicable artefacts, including weaponry, as ‘ritual’ or ‘ceremonial’.3 Indeed, a non-functional interpretation of the thin, wooden shield boards from Gokstad has persisted for more than a century without a serious empirical re-evaluation of the claim. Obviously, the shields were ceremonial in so far as they were part of the burial rite, but to what extent can they be considered as representative of functional shields (within the context of combat)? The ambiguities surrounding the Gokstad shields thus range from simple constructional aspects to interpretations regarding their function and role. As such, the surviving shield material of the Gokstad ship burial warrants a thorough re-examination. As a step in that direction, this paper presents the results of a short preliminary examination of the surviving Gokstad shield material that the current author undertook at The Viking Ship Museum in Oslo in May 2019. The aim of the study was two-fold. First, the artefacts were primarily studied for constructional details needed for a Viking Age shield reconstruction project (The Viking Shield: The First Authentic Round Shield in 1000 Years) conducted in collaboration with the Trelleborg Viking Fortress (National Museum of Denmark). This investigation was necessary as the shield boards from Gokstad are the only archaeological remains from Viking Age Scandinavia that are sufficiently preserved to offer insights into the shaping of the boards. Another aim was to assess the shield material for a more detailed investigation which could be conducted in the future with the aim of publishing the shield material in full. The results of the current study were surprisingly numerous and deemed sufficiently valuable to prompt this initial paper in anticipation of a larger project. With the recent completion of a PhD dissertation4, which in part deals with the shields from Gokstad, it is fitting to add my observations at this point, having examined a relatively large body of Iron Age and Medieval shield material in Scandinavia and beyond that can aid us in our interpretation.5 The purpose of this paper is thus not to provide any comprehensive treatment of the surviving shield remains from the Gokstad ship burial but to present a selection of the results from the initial examination, focusing on components that offer new insights into the constructional details of the shields, especially in relation to the claim of these shields being of a ceremonial nature. In so doing, the paper seeks to 4 R. F. WARMING contribute to our current understanding of Viking Age shield technologies and highlights the need for a fuller investigation into the shields from Gokstad and round shields in general. To achieve this, the paper is structured into four parts. First, I review and outline the archaeological context as well as both older and more recent scholarly attempts to understand the shields. Second, in the main analytical section, I present the findings from my preliminary examination of the shield fragments. Third, in the main interpretive section regarding the function of the shields, I consider some of the implications of the new findings. Finally, in the conclusion, I highlight the main findings of this study and recommend further analyses that could bring forth further clarity in relation to the points raised in this study. PART 1: research history Discovery and context To offer a contextual overview, the longship and the associated grave goods, including the shield material, were found in a monumental burial mound (known as Gokstadhaugen or Kongshaugen) at Gokstad in Vestfold, Norway. The burial mound was excavated in the spring of 1880 by antiquarian Nicolay Nicolaysen (then President of the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Norwegian Monuments), who had been notified that the sons of the owner of the Gokstad farm had begun digging in the mound and found handcrafted timber earlier that year. Upon excavation, a longship with ‘uncommonly well-preserved’ contents was found, although the burial had been partly disturbed by previous digging.6 The longship, too, was preserved in relatively good condition, but the upper woodwork of the vessel – including the upper part of the stem and stern with the adjoining planks and gunwale appurtenant – had rotted away, having lain in an upper layer of clay mixed with sand. Fortunately, the remaining upperworks had collapsed inwards at nearly a right angle under the pressure from the soil and thus been preserved in a layer of blue clay along with the rest of the vessel. The excavated vessel itself measures 23.8 m in length and 5.1 m in width with space for 32 oarsmen. A human skeleton of a male (aged c.40-45) of a powerful build and with evidence of peri-mortem trauma from combat was uncovered in a bed within a burial chamber aboard the ship.7 The excavated vessel was transported in two pieces to the University Gardens in Christiania (re-named Oslo in 1925) and subsequently became part of the collection of the Viking Ship Museum in 1932. Later dendrochronological analyses of the excavated oak timbers revealed that the ship had been constructed around AD 890-900 while the mound was dated to around AD 900-905.8 In addition to the longship, three smaller boats were also found as well as a broad variety of mundane and high-status items – such as equestrian equipment, kitchen utensils, beds, etc. - and different animal bones, including horses, dogs, goshawks and peacocks. While the many details regarding the vessel and the unique artefacts within the Gokstad burial mound are THE VIKING AGE SHIELDS FROM THE SHIP BURIAL AT GOKSTAD 5 far too numerous to be discussed in this place, the above should suffice as a general contextual introduction to the objects of interest in this current study, namely the shields.9 The excavated shields An unspecified number of shield fragments were found during the excavation. Based on their placement, Nicolaysen10 suggests that 32 shields had originally hung outside on each side of the vessel between the foremost oar-port up to a little abaft the furthest sternward.11 The shields overlapped so that the rim of each shield touched the boss of the next. Nicolaysen reports that they were painted either in yellow or black and positioned in alternating colours, giving the rows of shields an appearance of yellow and black half-moons. The shields had been fixed to the side of the vessel by thin bast cords that passed through the handle on the back of each shield and tied to the small quadrangular apertures in the skirting of the gunwale. Some shields, according to Nicolaysen, had disappeared with the portion of the ship’s portside that had been disturbed by previous digging. The upper parts of some of the remaining shields had been bent inwards with the gunwale along with parts of the vessel, resulting in that only minor parts of the shield boards were found in their original position. They had been bent in one of two directions: either nearly horizontally close to the boss or sideways over the edge of the gunwale. Shield bosses are mentioned by Nicolaysen but, as is the case with the rest of the shield material, the numbers are unspecified.12 A single fitting of iron coated in decorative sheet of copper-alloy (C10455) for a shield handle terminal was also recovered at the excavation.13 Notwithstanding this documentation, it is unclear how many shields components were in fact recovered from the excavation. Nicolaysen, however briefly, also comments on the construction of the shields. He concludes the following: Each shield was circular in shape and measured 94 cm in diameter. The boards were of white pine (analysed by Prof. A Blytt) and decreased in width towards the extremities of the shield. The shields were equipped with a hemispherical iron boss of a type typical for the Late Iron Age and a handle on the back that provided structure for the shield. He also observes that the shield edge was chamfered and equipped with fine holes around the circumference, convinced that these were used for fastening a metallic rim which had corroded away. As presented, Nicolaysen thus assumes a uniform construction with the only notable difference being the two pigments of the shields (Figure 2). The shields in the Museum collection and recent research The surviving shield material from the Gokstad ship burial are currently kept in the collection of the Viking Ship Museum in Oslo. The bulk of the shield material is comprised of an unspecified number of complete and fragmented wooden shield boards that are contained in 50 boxes (esker) under the same accession number 6 R. F. WARMING FIGURE 2. Drawing of a reconstructed shield. Adopted from Nicolaysen 1882: pl. VIII, fig. 7. (C10390). Four of these boxes (Eske 1-2 and Eske 49-50) contain more-or-less complete shields which were restored and hung on the side of the ship in the late 19th to early 20th century.14 There is a widespread assumption that these four ‘reconstructions’ from Gokstad, along with their modern reinforcements, are representative of Viking Age shields, wherefore it is necessary to discuss them in this place. The four shields are crudely assembled, and it is highly questionable whether the boards in each reconstruction have originally been part of the same shield. Judging from shield shape, number of boards and degree of preservation, the shields boards appear to have been assembled based on aesthetic criteria, rather than their original archaeological context. The reconstructions have been reinforced by modern round steel frames along the circumference on the back of the shield boards and three crosspieces (including a ‘handle’) which have been nailed to the wooden boards (Figure 3). As is also the case with many other wooden objects that was exhibited in the late 19th and early 20th century, the front sides of the shields have been covered with an unidentified black substance, probably creosote/tar.15 These modifications and the general unscientific assembly of the shields render them an unreliable source of data for Viking Age shield technology that should be consulted with caution. In comparison, the fragmented but unaltered shield components are far more numerous and reliable as a source of data for Viking Age shield constructions. A limited number of studies have been conducted on these shield remains since Nicolaysen’s publication in 1882. The pigments on the shields have incited much interest from scholars but have until recently, to my knowledge, only been subjected to analyses by chemist Unn Plahter, the results of which were seemingly inconclusive.16 More importantly, as mentioned in the introduction, the shields were also re-examined in 2016 and 2018 in conjunction with a recent PhD dissertation by Kerstin THE VIKING AGE SHIELDS FROM THE SHIP BURIAL AT GOKSTAD 7 FIGURE 3. Shield ‘reconstruction’ cobbled together in the late 19th - early 20th century. The shield is reinforced with modern steel frames but comprised of original boards. The central board is seemingly equipped with a roughly heart-shaped centre hole. Photo: # Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo, Norway. Rotated 90 degrees clockwise by the author. Odeb€ ack.17 According to Odeb€ack, the material consists of three reconstructed shields, 429 wooden fragments and 18 shield bosses. Based on her re-examination of six fragmented central boards, Odeb€ack argues that the central holes of the shields were not circular, highlighting a central board with two half-circular cut-outs (c.3.5 cm wide) along the board edge which, to her, suggests a small figure-of-eight shaped configuration behind the boss.18 The apertures would leave no room for a hand but would suffice for the bast cords with which the shields had been fastened to the ship. Odeb€ack does not specify if similar configurations were observed on the other central boards. She also states that traces of pigment or leather could not be confirmed by recent X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) analyses conducted on a selection of the shield fragments; however, traces of lead and iron were found on all the examined timber and could possibly be connected to chemical compositions of pigment, for example red and white.19 Based on the above, Odeb€ack suggests that the shields were constructed for the express purpose of the mortuary practice, rather than for use in combat.20 Notwithstanding these studies, there is much that remains to be done on the subject, including a detailed cataloguing of the extant shield remains. The current paper contributes to this body of literature with a critical assessment of the constructional features, highlighting new findings in relation to past interpretations, and suggests potential paths for further research. 8 R. F. WARMING PART 2: the Gokstad shields revisited General remarks The results from the re-examination will be presented in this section. The empirical basis of the present study are the wooden shield boards contained in the remaining 50 boxes which remain largely undocumented. Shield bosses were not examined in this study, except through previous documentation (Figure 4). As mentioned, the material was examined in connection with a shield reconstruction project for the purpose of gaining knowledge of constructional details – especially in relation to other finds - and to assess its potential for further analysis. The investigation was a basic material culture study, involving documentation through ocular inspection, measurements and photography. Special emphasis was placed on overall diameter, shape and size of the centre hole, thickness, handle, perforations and possible residues of skin product or other organic material. These aspects are discussed below following a few general remarks on the shield material as a whole and the condition of the examined artefacts. Reviewing the archaeological documentation, it is evident from the outset that the material itself is not of a high-status nature despite stemming from a monumental ship burial. The shields were equipped with a simple hemispherical boss of iron (R562) and devoid of other metal fittings, thus being in accordance with the majority of archaeological shield finds in Scandinavia where only the boss tends to survive.21 FIGURE 4. Selection of fragmented shield bosses. Irregular notches and cuts (trauma?) are discernible on several examples. Photo: # Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo, Norway/Vegard Vike. THE VIKING AGE SHIELDS FROM THE SHIP BURIAL AT GOKSTAD 9 One exception to this general picture is the decorative handle terminal fitting of iron and copper-alloy (C10455), indicating that at least one shield in the Gokstad ship burial can be ascribed to the category of more prestigious shields found elsewhere in Scandinavia.22 The unimpressive nature of the bulk of the shield material can in part explain the general lack of detailed analyses of these artefacts. Turning to the archaeological material itself, it was found that only the boxes are differentiated by numbered labels even though most of them contain several artefacts. The surviving artefacts range from minor unidentifiable fragments to entire shield boards.23 These are generally in poor condition but sufficiently preserved in quantity to reveal several important details on the better-preserved pieces of timber. Some shield boards are highly fragmented and suffer from varying degrees of distortion and cracks due to the lack of conservation. The measurements given in this paper, although taken off relatively well-preserved parts, should therefore be treated with caution and not necessarily be considered as representative of their original dimensions. Both smaller and larger quantities of unidentified organic layer was observed on the surface of several of the boards, including patches of a distinctly yellowish colour. These should be subjected to further analyses (e.g. XRF, ZooMS and multiple microanalyses) for possible identification of traces of skin product and pigment.24 As such, there is great variation in the level of preservation of the material but much potential for future analysis despite their seemingly unimpressive state. Diameter and centre holes According to Nicolaysen, each shield had a diameter of 94 cm and, based on his drawing, understood as perfectly circular in shape.25 This claim could only be partially assessed with confidence based on two surviving central boards from two different shields (in Eske 5 and Eske 22), identified based on their partially preserved centre holes (Figure 5). Assuming symmetry and a centre hole with an original internal diameter of c.10 cm, it is possible to arrive at an estimated total diameter of c.90 cm for the shield in Eske 5 and c.92 cm for the one in Eske 22. This hints at a certain degree of standardization with regards to size which would be worthwhile to explore further in future studies of the fragments. Whether the shields were perfectly circular (or slightly oval) could not be determined in this investigation. All shields were assumedly equipped with a centre hole behind the boss. The shapes of the centre holes were possible to determine as roughly circular/oval or Dshaped based on some of the fragmented centre boards. The observed edges were chamfered at steep angles on the reverse side, thus facilitating a more comfortable handling of the shield. Moreover, despite being cobbled together, it is evident that the surviving centre holes on the boards of the ‘reconstructions’ are of similar shape and size and, indeed, chamfered. As such, the observed centre holes from the Gokstad shields are in accordance with those that have been observed on other well-preserved shield finds dating to the Viking Age and earlier periods.26 The presence of smaller 10 R. F. WARMING FIGURE 5. Central shield board from Eske 5 with the author’s hand to visualize the position of the centre hole. A longitudinal row of perforations was observed along the lower edge. Photo: R. Warming/Society for Combat Archaeology. cut-outs, as suggested by Odeb€ack, was only possible to confirm in one case through photographic evidence following her publication (Eske 47).27 However, in contrast to Odeb€ ack’s interpretation of a figure-of-eight shaped configuration, which assumes symmetry, it is more plausible to interpret this as stemming from a large heart-shaped or D-shaped aperture where a strip of board had been retained between the two semi-circular cut-outs, thus leaving sufficient room for a hand (Figure 6).28 A similar configuration is seen on one of the ‘reconstructions’, although the cut-outs are less pronounced, possible due to preservation conditions (Figure 3). It is possible to interpret this centre hole as a method of providing partial support for the handle but the semi-circular cut-outs may also indicate a specialized suspension feature for accommodating ropes or similar. If so, the orientation of the asymmetrical centre hole may correspond to different uses of the shield. Thickness and tapering Special attention was given to the dimensions and shaping of the shield board fragments to determine overall thickness and potential tapering. In all cases where it was possible to measure the overall thickness of the boards and the edge it was found that the boards had an overall thickness of 8-9 mm with tapering towards the edge. Two different tapering systems were identified in the examined material: one radical tapering or chamfering at the very edge (c.2-3 cm from the edge) and a gentle THE VIKING AGE SHIELDS FROM THE SHIP BURIAL AT GOKSTAD 11 FIGURE 6. Schematic illustration of hypothesised heart-shaped centre hole with a handle in the centre. This configuration would leave room for a hand in the aperture. Illustration: R. Warming/Society for Combat Archaeology. tapering beginning further back towards the centre of the shield (c.6-10 cm from the edge). Radical tapering or chamfering is known from other contemporary finds– such as the rim fragment from Bj850 (chamfered 2 cm from the edge) – where it is used to accommodate a rim of organic or metallic material.29 The gentle tapering has also been identified in other shield finds, being an important factor in reducing the overall weight of the shield.30 The two tapering systems seem to have been applied to the boards in different ways, offering a uniquely detailed insight into this aspect of shield craftsmanship. All boards which could be identified as having been positioned towards the extremities of the shield construction had been tapered using both systems. In these cases, the gentle tapering usually began approx. 6-10 cm from the edge on both sides of the board, reducing the thickness of the board from c. 8-9 mm to 5-6 mm; the radical tapering began 2-3 cm from the edge, reducing the thickness further to 3-4 mm (Figure 7). At least one of the central boards (Eske 5) was sufficiently preserved to determine that the gentle tapering had not been applied to this particular piece and had only been radically tapered (from both sides), thus reducing the thickness from c. 8-9 mm to 3-4 mm only at the very edge. On some boards, moreover, the radical tapering had been done on both sides (e.g. on a board in Eske 48) whereas on other examples it was observed on only one side (e.g. Eske 9), thus showing a degree of variation in the craftsmanship. 12 R. F. WARMING FIGURE 7. Board with both gentle tapering (yellow) and radical tapering or chamfering (red). The dotted line indicates the centre of the board. Photo: R. Warming/Society for Combat Archaeology. How is the discrepancy in the application of the radical and gentle tapering systems to be interpreted? The disjointed finds were stored in the museum collection without any documentation of their original context, rendering it challenging to reassemble the boards into their original constructions with confidence. It is certainly possible that the examined board fragments belong to separate shield constructions with their own respective systems of continuous tapering around their edge. However, it is equally possible that the shield constructions, or at least some of them, featured non-continuous systems of tapering around the edge. More specifically, the correspondence between the identified systems of tapering and the relative positions of the examined boards suggest that the central parts of the shield may have been tapered differently than the boards at the extremities within the same shield construction. A possible explanation for the observed tapering is found in the practical use of the round shield. Rather than passive defence, the round shield was particularly wellsuited for active use in combat.31 Generally, the tapering described above would result in a lighter shield with most of the mass situated in the middle of the shield, meaning that it was easier to control from the handle and less prone to be manipulated at the extremities. In addition, the tapering would allow the shield wielder to rotate or spin the shield more easily around the boss by reducing rotational inertia. Potential explanations for the central planks being less tapered around the edge could be related to balance preferences in the handling of the shield or a desire of retaining THE VIKING AGE SHIELDS FROM THE SHIP BURIAL AT GOKSTAD 13 the thickness of the shield board for additional protection where it would be more challenging to deflect blows. Handle Evidence for handles is surprisingly scarce in the surviving shield material from Gokstad. According to Odeb€ack there is only a single fragment (34.5 cm in length) from such a handle amongst the material.32 In examining the shield remains Eske 32 was found to contain a fragmented handle with an irregular quadrilateral or triangular cross-section. Although of a different length than that reported by Odeb€ack it is assumedly the same handle fragment as the one discussed in her dissertation. It measures 49.7 cm in length and 1.8-2.3 cm in width, the thickness ranges from between 7 mm to 13 mm (Figure 8). The top of the handle is facetted and equipped with a delicate ridge which runs along most of its length (c. 41.5 cm). The grip has not been preserved but the thickness of the handle increases significantly in one of the distal FIGURE 8. Handle fragment seen from the thicker and more fragmented distal end. Photo: R. Warming/Society for Combat Archaeology. 14 R. F. WARMING ends and is assumedly the beginning of this part of the handle. The cross-section at this end is roughly triangular and has a relatively crude appearance, although it is unclear to what extent this is owing to distortion and splitting. The wood species is undetermined but is potentially another species than the timber for the shield boards, perhaps hardwood, as is known from other archaeological finds, such as the handle of beech discovered together with the shield from Trelleborg, Denmark.33 With this handle in mind, it is worth returning to the so-called reconstructions. In one of them the middle crosspiece is similarly shaped to the examined handle fragment and includes a facetted central grip. In another all three crosspieces are similarly fashioned, indicating perhaps that original handles have been reused as both handle and supporting crosspieces. Unfortunately, there is no information available to confirm or debunk whether these parts are original handles or reconstructions based on them. Although only a single handle fragment can be positively identified it is evident that additional information can be gained from some of the surviving shield boards. Perforations for rivets to fasten the handles to the shields are visible along the centre of several boards. Most interesting are perhaps some of boards that can be identified as those belonging either to the top or bottom of the shield construction based on their overall shape. Eske 22 seemingly contains such a board which, although partially deformed, shows a clear impression or groove in the wood (along with a rivet hole) where the handle would have been positioned. The dimensions of the groove and the position of the rivet hole match with the aforementioned handle fragment, thus confirming the suggested rotation of this piece. This observation also confirms that the handles spanned most of the diameter of the shields and, more specifically, without the added length of a metal handle terminal, stopped short only 2-3 cm from the edge, i.e. before a potential rim reinforcement and the radical tapering of the shield boards. Perforations Small rows of perforations, generally separated by c. 1-1.5 cm, were observed around the rim of several boards, as also noted by Nicolaysen and Odeb€ack.34 These can reasonably be interpreted as sewing holes for attaching a shield rim or facing of organic material, most likely of skin product.35 Similar perforations can be observed on the nearly complete 9th century round shield from Tira, Latvia, where two layers of untanned bovine hide are preserved.36 No additional rim reinforcements have been found in connection with the shield from Tira, indicating that the two layers assumedly overlapped and were fastened together at the edge. Although this configuration has not been identified in the Scandinavian material, it demonstrates that perforations around the rim could be used for fastening skin products in a variety of ways and do not necessarily entail the presence of a separate rim reinforcement. Interestingly, some of the shield boards from Gokstad did not show any evidence of rim perforations. It is therefore possible that some of the shield boards were not THE VIKING AGE SHIELDS FROM THE SHIP BURIAL AT GOKSTAD 15 FIGURE 9. Longitudinal rows of perforations on the central board from Eske 5, indicated in yellow (see also Figure 5). Photo: R. Warming/Society for Combat Archaeology. intended to be reinforced with skin product or that the skin product was not sewn into place in those particular areas. In the reconstruction project with Trelleborg Viking Fortress (National Museum of Denmark), we demonstrated that fastening using casein glue and limited sewing in specific areas around the shield rim was sufficient for keeping both the rim and facings in place.37 A third explanation could be that the perforations have been sealed by post-depositional processes; however, considering the general level of preservation of the artifacts in question, such an explanation seems unlikely. Another important but hitherto overlooked detail is the presence of longitudinal rows of perforations along the edge of some of the central boards, e.g. those in Eske 5 and Eske 22. The perforations were in both cases positioned roughly along the same axis as the edge of the centre holes; in the case of Eske 5 the observed perforations had a spacing of 3.8-15.9 cm whereas the board from Eske 22 had a more even spacing of 7.2-8 cm (Figure 9). Cracks at similar intervals and positions were also observed on other shield boards, including the so-called reconstructions, but these features could not with confidence be ascribed to similar perforations and are, without further analyses, just as likely to simply stem from post-depositional processes. Similar longitudinal rows of perforations have been observed on the well-preserved 9th century round shield from Tira in Latvia as well as on the 4th century examples from Nydam in Denmark.38 These perforations can be interpreted as stitching repairs for longitudinal splits or as methods of fastening skin product to the shield board in cases where several segments were necessary to cover the surface area of the shield. In our reconstruction project, the shield-maker (Tom Jersø) noted that such perforations were useful for stretching and fastening the skin product to the shield boards.39 The exact nature of the perforations on the Gokstad shields cannot discerned at this point without further analyses but would in consideration of the above be important to investigate further. 16 R. F. WARMING PART 3: discussion and interpretation For combat or ceremony? Having reviewed a selection of the shield fragments, it is relevant to consider the question of whether the Gokstad fragments represent practical or ceremonial shields. By this crude dichotomy is meant a distinction between functional shields in the context of combat and shields expressly made for display, e.g. as ceremonial representations in connection with the burial rite.40 An overarching challenge in this question is the disadvantage of not being able to examine a complete example; instead, without further investigations that can piece together the artefacts with confidence, any answer to this question must necessarily rely on an examination of disconnected fragments and their features. Nonetheless, we can consider the merits of the above findings without subscribing shields to either claim or assuming that they are all the same. An important question in this respect is whether the shields were reinforced with skin product. The fragility of the shields and their unsuitability for combat was already remarked upon by Nicolaysen (1882: 63).41 Indeed, a number of studies have since then convincingly demonstrated the significance and practical necessity of skin product in functional shield constructions for use in combat.42 A common but erroneous conclusion regarding the shields from Gokstad is that they were necessarily devoid of skin product as their surface had been painted; however, as demonstrated through experimentation, it is possible to render rawhide more-or-less transparent through stretching and various chemical treatments, thus making it possible for the colours on the shield board to surface.43 Using newly developed methods involving multiple microanalyses and ZooMS, a recent study has convincingly identified thin, parchment-like rawhide covers of cattle on the round shields from Baunegaard (Bornholm, Denmark), dating to c.250-310 AD, and Tira (Latvia), late 9th century AD. In the case of a shield from grave Bj 850 in Birka (Sweden), dating to the 10th century, both the facing (sheepskin) and rim reinforcement (bovine) was identified as tanned leather.44 Similar analyses on the unidentified organic material on the surface and around the edge of the shield boards from Gokstad (e.g. Eske 15) may reveal important clues regarding potential reinforcement of the shields.45 Considering the above, the perforations around the rim on the Gokstad shields, coupled together with the painted surface, strongly suggest that at least some of them had been covered with thin, parchment-like rawhide.46 However, another possibility, which cannot be ruled out at this point due to the wanting 19th century documentation, is that the shields may have been painted on the backside and reinforced with skin product on the front, as seems to be the case with the shields from Nydam.47 Finally, although much less likely, the shield boards may for some unexplained reason have been covered by skin product despite having been painted. The longitudinal rows of perforations on some of the central boards offer further indications of the original function of the round shields. As pointed out elsewhere, THE VIKING AGE SHIELDS FROM THE SHIP BURIAL AT GOKSTAD 17 the observed perforations may suggest that the assemblage contains shields that were repaired or covered with skin product.48 Both possibilities point towards shields constructed for the purpose of being used in combat. On the other hand, it is equally important to note that any potential repairs could also have been undertaken in the original construction process and that some faulty material may have been permissible if the shields were mostly for visual display. Relatedly, the quality of some of the timber also indicates a certain degree of deficiency in the final product. This is certainly the case with a fragmented board in Eske 46 (length c.53 cm; width 8.6 cm) which contains a large knot in the wood (Figure 10). However, as the knot may have looked entirely different before post-depositional drying processes, it is possible that the shield-maker did not regard the knot as particularly problematic although the timber quality was suboptimal. Indeed, poor quality timber with knots have also been identified in other finds that are considered entirely functional, such as the upper planking of the Skuldev 5 shipwreck dated to c.1030 AD.49 The rest of the board from Eske 46 is otherwise normally shaped and intricately tapered, starting 6-7 cm from the edge. This indicates that a certain amount of time and energy was invested in the crafting of the shield despite the condition of this particular piece of timber. Another case in point is the single handle fragment in the assemblage. The relatively fragile and roughly shaped handle may indicate that it was quickly constructed with little concern for ergonomics or the structural integrity of the shield. However, as is the case with the board, the post-depositional distortions of the timber leaves room for the possibility the handle was originally more suited for the shield construction than can be gained from its present form. In general terms, the craftsmanship is mostly in accordance with other shield finds that are judged to be of a practical nature and the Germanic flat round shield 10. Board with knot protruding from the timber. Photo: R. Warming/Society for Combat Archaeology. FIGURE 18 R. F. WARMING FIGURE 11. The Skuldelev 5 shipwreck at the Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde, Denmark. The ship was equipped with an external shield rack, a portion of which survives (visible to the left on the top strake). Photo: Werner Karrasch. Copyright: Vikingeskibsmuseet i Roskilde. tradition as a whole.50 This includes the majority of the constructional details, such as the shape and dimensions of the centre holes as well as the boards, and, especially, their tapering. In addition to the shaping of the very edge, some boards were tapered from further back, indicating a complex carpentry process that lends further credibility to notion of practical use. The preliminary results from the current study also suggest that at least some shield boards were constructed with the intention of reinforcing them with skin product on the rim and, most likely, on the front and back of the shield, despite having been painted. Neither skin product nor paint has yet been positively identified with modern methods but several boards with patches of unidentified organic material may offer some clarity in future investigations.51 The observed longitudinal perforations, although at present somewhat unclear, are also in accordance with finds from other contexts. Against this overall impression are a number of irregular features that can be summarized in this place. Undoubtedly, the feature that is most at odds with our current understanding of practical shields is the set of miniature centre holes observed by Odeb€ ack52; however, as discussed above, an alternative explanation is possible. To this we may add the suboptimal quality of the aforementioned shield board and the single handle fragment, although their state may be due to post-depositional processes. The lack of skin product is also worthy of note but is likewise possible to explain by preservation conditions, especially considering the rows of perforations discussed above. In summary, the Gokstad shield assemblage mostly exhibits diagnostic features that are strongly associated with ‘practical shields’ known from other contexts. Features that may indicate non-functionality (at least in the context of hand-to-hand THE VIKING AGE SHIELDS FROM THE SHIP BURIAL AT GOKSTAD 19 combat) are highly limited as well as ambiguous due to preservation conditions. The constructional analysis thus supports a more practical interpretation of the shield assemblage as a whole, although with the reservation of it potentially containing some non-functional elements as well. Roles in life and death Given the observed differences in the constructional features, including the potentially ‘ceremonial’ elements, it is evident that past assumptions of uniformity are incorrect and that new interpretations must be sought out. Although the above strongly suggests an assemblage of ‘practical shields’, this section takes a more balanced approach in the search for different explanatory paths. Beyond the explanation of different craftsmen, it is useful to consider the function(s) of the shields in both life and death through a more biographical perspective.53 In basic terms, the observed heterogeneity can be viewed as either representing an original assemblage with different shield constructions or as a homogenous shield assemblage that was later modified. Following this logic, one interpretation is that the observed differences represent shields serving different functions in life. As is well-known, ships armed with shields along their top strakes (harbrynjuð/hardbrynjuð skip) were certainly of practical use in armed conflicts; however, their display seemingly also held special significance, as evidenced by a number of historical and iconographic sources.54 Conceivably, this arrangement of shields could be used to convey strength, in which case the shields did not need to be entirely functional for hand-to-hand combat. To be critical, the shield board with the small apertures, although potentially impractical for handling, can be interpreted in terms of a more passive shipborne defence on the side of the ship, known from contemporary cultures such as Byzantium who employed specialised shields known as dorkai aboard their ships.55 The importance of a visual display, as opposed to a combat function in this context, is perhaps indicated by the fact that the shields were simply tied to the skirting of the gunwale instead of being hung from a shield rack (Figure 11), although the former may also be considered an archaic fastening method.56 In this sense, the assemblage of shields, despite their differences, may be interpreted as part of the ordinary equipment associated with the ship in life. It is, of course, also possible that the shields served different combat functions and visual functions beyond the maritime context. Another interpretation, which is linked to past interpretations of the assemblage being entirely comprised of ceremonial shields, is that some shields were expressly constructed for the burial rite. Accepting that the assemblage included shields that were not intended for combat, it is tempting to see it as a case of Viking Age shield symbolism which is well-attested in both archaeological and historical sources.57 Such symbolism can be observed in other burials that contain non-functional shield elements, such as the 10th century AD ship burial at Myklebustad where a cauldron containing eight shield bosses and cremated bones was uncovered.58 Outside of 20 R. F. WARMING Scandinavia, in Anglo-Saxon England, we find clear cases of non-functional ‘funerary shields’, e.g. Graves 33 and 93 at the Worthy Park cemetery (dated to the 5–7th century), both of which contained a heavily damaged and repaired shield boss without any rivets.59 Other symbolic artefacts specifically made for burials are known from elsewhere in Europe, e.g. the goldblattkreuze of southern Germany and the Alps.60 In other words, abstract symbolism involving seemingly non-functional artefacts and weaponry is not an unusual phenomenon in burial practices and can to some extent explain the nature of the observed features in the Gokstad ship burial, if they really are non-functional. From a more pragmatic perspective, however, the observed differences can also be explained by the share quantity of shields in this burial. Considering the level of energy expenditure involved, some shields may simply have been included as substitutes. While a certain number of available shields, perhaps even the majority, comprised ‘practical shields’, other (‘ceremonial’) shields may have been constructed specifically for the burial to fill the gaps – or vice versa. To add further complexity to the subject, it is also possible that shield components from originally ‘practical shields’ could have been re-used in the construction of new (‘ceremonial’) shields for the burial rite. As such, a potential mix of ceremonial and practical shield elements can be interpreted as a practical solution to a complex and resource demanding burial practice. In either case, the demands driving the inclusion of such a large quantity of shields in the funeral seems closely associated with the ship. As suggested by Nicolaysen, the shields can be taken to represent 64 crew members aboard, given the ratio of two shields per oar hole (32 oar holes in total).61 This general association between the number of shields and ship size has certainly been recognised in connection with other ship burials, such as at Myklebustad from c.875-950 AD with 44 shields and Fosnes from c.900-950 AD with 10 shield bosses.62 Another conceivable, and not wholly incompatible interpretation, is that the shields are part of the ship’s equipment.63 Thus, a certain significance may have been tied to displaying a full crew in symbolic terms or a fully equipped ship in connection with the burial ceremony. Going further, and considering the peri-mortem trauma identified on the deceased, a more daring interpretation of a potential lack of ‘practical shields’ may be that a number of them had either been lost or destroyed in a violent encounter, perhaps together with their bearers.64 In this respect, a closer inspection for possible evidence of trauma and use-wear in the shield material, especially the bosses, would be interesting to pursue in future investigations (Figure 4). Given the strong association with the ship, it would also be pertinent to re-examine shield material from other ship burials for similar indications as those noted in this paper. While the above considerations provide us with different explanatory possibilities, it is too early to make any conclusive interpretations regarding the shield assemblage as a whole. The considerations listed here should be seen as points of departure for further studies into the shields and, more broadly, how they relate to what we currently know about funerary practices of the Viking Age. To better understand the shield assemblage, it will be important to examine the cultural biographies of the THE VIKING AGE SHIELDS FROM THE SHIP BURIAL AT GOKSTAD 21 objects. For now, it is sufficient to say that the heterogenous nature of the shield assemblage needs to be addressed and can either be interpreted as a consequence of their use in life or the funerary rite. Conclusion In examining the wooden shield fragments from the Gokstad ship burial, this study highlights the need for a more nuanced interpretation of these artefacts and serves as useful reminder of the complexity of Viking Age shield technologies. Most significantly, the investigation shows that the shield material reflects a high degree of uniformity but also important differences beyond the use of pigments, including constructional features that strongly suggest a functional use of the shields, although certain features can potentially be ascribed to shields of a ceremonial nature. This assessment forms a cogent argument for discarding past interpretations of these shields as being merely ceremonial as well as the overarching dichotomous discussion of whether all the 64 shields are necessarily either for ceremony or combat. It is assumedly partly because of the underappreciation of the complexity of the shields and the underlying assumption of homogeneity that many constructional details have been overlooked since Nicolaysen’s excavation in 1880. Although only a brief and preliminary investigation, the present study has thus brought forth a number of significant considerations and points of departure for future studies. The Gokstad shield material has yet to be published in full and much of the material should be subjected to re-examination, where careful attention is paid to the craftsmanship, the thin patches of organic material on some of the boards and details that can connect the various fragments, although the reassembly of a complete shield is unlikely. With a much richer body of literature available on round shields today than at the time of their excavation, it will also be important to compare the constructional details of the Gokstad shields to other archaeological finds and the Germanic flat round shield tradition in general. When carefully examined, the wooden fragments can continue to animate our understanding of the construction and roles of shield technologies of the Viking Age as well as funeral rites in general. The devil is in the detail and the pagan ship burial at Gokstad has fortunately left us many to examine. Acknowledgements Special thanks to Prof. Jan Bill and the Viking Ship Museum in Oslo for providing access to the shields and to Vegard Vike, conservator at the Museum of Cultural History, for his kind help in providing information and photos. I am also grateful for the kind suggestions provided by Dr Astrid Noterman (Stockholm University) and Tomas Vlasaty (Projekt ForloRg) in their review of this paper. Thank you also to the anonymous peer-reviewer for their kind and helpful comments. Finally, I would like to thank the Viking Fortress Trelleborg (National Museum of Denmark) for financing the research trip. 22 R. F. WARMING Notes 1 E.g. N. Wexelsen, Gokstadfunnet: et 100-års minne (Sandefjord: Sandefjord Bymuseum, 1980). 2 N. Nicolaysen, Langskibet fra Gokstad ved Sandefjord: (Christiania: Cammermeyer, 1882), pp. 62f; pl. VIII, fig. 7. 3 E.g. P. Beatson and K. Siddorn. ‘Shield,’ in Viking: Weapons & Warfare, ed. by K. Siddorn (Stroud: Tempus, 2000), pp. 35–57. 4 K. Odeb€ack, ‘Vikingatida Sk€ oldar: Ting, Bild Och Text Som Associativt F€ alt’ (PhD diss., Stockholm University, 2021). 5 E.g. R. Warming, ‘Shields and Martial Practices in the Viking Age’ (unpublished MA, University of Copenhagen, 2016); R. Warming, ‘Praksistilgangen i Kamparkæologi: “The Practice Approach” og vikingetidens krigeriske praksisser,’ Arkæologisk Forum, 38 (2018), 15– 23; R. Warming, R. Larsen, D., ‘Shields and Hide: On the Use of Hide in Germanic Shields of the Iron Age and Viking Age,’ Bericht der R€ omisch-Germanischen Kommision 97 (2020), 157–227. <http://nbn-resolving.de/ urn:nbn:de:bsz:16-berrgk-766417 > [accessed 30 August 2022]; R. Warming. Viking Age Round Shields and High Medieval Bucklers: The Emergence of the Sword and Buckler Tradition in Scandinavia (In Press); R. Warming. ‘Bucklers in Scandinavia: A Case Study,’ in The Medieval and Renaissance Buckler, ed. by H. Schmidt (Sofa Books, 2022); R. Warming and I. Zeiere. Two 9th Century Curonian Shields from Tira, Latvia (Forthcoming); Warming. The 12th Century Shield from the Kn€ osen Wreck: On Round Shields from the Late Viking Age and High Middle Ages (In prep). 6 This disturbance is most likely owed to the partial reopening of the grave and plundering shortly after its erection, as evidenced by the wooden spades that had been left behind, dated by dendrochronology to 939-1050 CE. See Nicolaysen 1882, p. 6; J. Bill. and A. Daly, ‘The Plundering of the Ship Graves from Oseberg and Gokstad: An Example of Power Politics?,’ Antiquity, 86 (2012), 814f.; Odeb€ ack, ‘Vikingatida Sk€ oldar,’ p. 52. 7 Ibid; P. Holck, ‘The Skeleton from the Gokstad Ship: New Evaluation of an Old Find,’ Norwegian Archaeological Review, 42 (2009), 40–9. 8 N. Bond, ‘Dendrochronological Dating of the Viking Age Ship Burials at Oseberg, Gokstad and Tune, Norway,’ in Archaeological Sciences, ed. by A Sinclair, E. Slater and J. Gowlett (Oxford: Owbow Books, 1994), pp. 195–200; J. Bill, ‘Revisiting Gokstad. Interdisciplinary Investigations of a Find Complex Investigated in the 19th Century,’ in Fundmassen, Innovative Strategien zur Auswertung fr€ uhmittelalterlicher Quellebest€ ande, ed. by S. Brather and D. Krausse (Konrad Theis Verlag, 2013), pp. 75–86. 9 For a comprehensive treatment, see Nicolaysen 1882. 10 Ibid, 62f. 11 This formulation in Norwegian has seemingly caused some confusion in the English translation, resulting in that 32 shields is often reported as the total number. 12 In the museum catalogue entry from March 1957, it is noted that there are remains of c.35 shield bosses, of which a few were more-or-less complete (C10390, katalogtekst). 13 Nicolaysen 1882, Pl. X. 20. 14 Pers.com. Vegard Vike, conservator at Museum of Cultural History in Oslo, 23 March 2018. 15 Ibid. 16 Ibid. 17 Odeb€ ack, ‘Vikingatida Sk€ oldar,’ pp. 53–6. 18 Ibid, 54f. 19 Ibid, 55.; K. Odeb€ ack, C. C. Steindal and J. Bill, Forthcoming. ‘The Shields from the Gokstad Ship Burial: A Reassessment,’. 20 Odeb€ ack, ‘Vikingatida Sk€ oldar,’ pp. 56, 60, 190. 21 O. Rygh, Nordske Oldsager (Christiania: Cammermeyer, 1885). 22 This may mean that the total number shields is 65, not 64; see, K. Hjardar and V. Vike, Vikinger i Krig (Oslo: Spartacus, 2011), p. 185; A. Pedersen, Dead Warriors in Living Memory: A Study of Weapon and Equestrian Burials in Viking-Age Denmark, AD 800-100 (Copenhagen: University Pres of Southern Denmark, 2014). Studies in Archaeology & History vol. 20: 1 1 Jelling Series, p. 101; T. Vlasat y, ‘The Shield Handle from Myklebost. Projekt Forlo Rg: Reenactment a Veda,’ <https://sagy.vikingove.cz/ en/the-shield-handle-from-myklebost/> [accessed 30 August 2022]. 23 Considering Nicolaysen’s interpretation of 64 shields, there is surprisingly little material. Much of the timber may have been discarded after the excavation but the original interpretation can also be questioned. 24 For methods, see Warming et al., pp. 157–227. 25 Nicolaysen, 1882, p. 94. 26 E.g. H. H€ arke, ‘Shield Technology,’ in Early AngloSaxon Shields, ed. by H. H€ arke and T. Dickinson (London: The Society of Antiquarians in London, 1992), Archaeologia 110, pp. 31–54; J. Ilkjær, Illerup Ådal bd. 9-10. Die Schilde (Århus: Jysk Arkæologisk Selskab, 2001). Jysk Arkæologisk Selskabs Skrifter 25; A. Dobat, ‘Fund Fra THE VIKING AGE SHIELDS FROM THE SHIP BURIAL AT GOKSTAD Undersøgelserne ved Trelleborg,’ in Kongens Borge: Rapport Over Undersøgelserne 2007–2010, ed. by A. Dobat (Århus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 2013), Jysk Arkæologisk Selskabs Skrifter 76, pp. 148–69; Warming, ‘Shields and Martial Practices,’ ; P. Vang Petersen, ‘The Painted Shields from Nydam,’ in Excavating Nydam: Archaeology, Paleontology, and Preservation. The National Museum’s Research Project 1989–99, ed. by S. Holst and P. O. Nielsen (Copenhagen: University Press of Southern Denmark, 2020), pp. 141–96.; Warming and Zeiere, Two 9th Century, Forthcoming. 27 Odeb€ack, ‘Vikingatida Sk€ oldar,’ pp. 54f. 28 A sufficiently large aperture of this sort is possible within the parameters provided by oldar,’ pp. 54f.; see Odeb€ack, ‘Vikingatida sk€ also ‘hand hole 4’ in Vang Petersen, ‘The Painted,’ p. 151. 29 Warming et al., pp. 157–227; See also, G. Arwidsson, ‘Schilde,’ in Birka II:1 Systematische Analysen der Gr€ aberfunde, ed. by G. Arwidsson (Stockholm, 1986), pp. 38–44; Ilkjær, Illerup Ådal, pp. 347ff. 30 H€arke, ‘Shield Technology,’ pp. 47f; Society for Combat Archaeology, ‘Project: The Viking Shield,’ <https://www.facebook.com/media/set/ ?set = a.1696875160459269&type=s3> [accessed 30 August 2022]; Warming and Zeiere, Two 9th Century, Forthcoming. 31 E.g. Warming, ’Praksistilgangen’; Warming, ‘Bucklers in Scandinavia’; R. Warzecha, ’Form folgt Funktion: Wie die Anforderungen im Kampfeinsatz die Formgebung von der Spatha zu mittelalterlichen Schwertern beeinflussten’, in Das Schwert – Symbol und Waffe. Beitr€ age zur geisteswissensschaftlichen Nachwuchstagung vom 19.-20- Oktober 2012 in Freiburg/Breisgau, ed. by L. Deutscher, M. Kaiser & S. Wetzler (Verlag Marie Leidorf, 2014.), pp. 153161; S. Hand, ’Further Thoughts on the Mechanics of Combat with Large Shields’, in SPADA 2: Anthology of Swordsmanship, ed. by S. Hand (Texas: The Chivalry Bookshelf, 2005): pp. 51-68. 32 Odeb€ack, ‘Vikingatida Sk€ oldar,’ p. 54. 33 H€arke, ‘Shield Technology,’ pp. 35ff; Dobat, ‘Fund Fra,’ pp. 163ff; Warming, ‘Shields and Martial Practices,’ p. 54; Odeb€ ack, ‘Vikingatida Sk€ oldar,’ p. 54. 34 Nicolaysen, 1882, p. 62; Odeb€ ack, ‘Vikingatida Sk€ oldar,’ p. 54. 35 Warming et al., pp. 157–227. 36 Ibid.; Warming and Zeiere, Forthcoming. 37 Society for Combat Archaeology, 2019. 38 Vang Petersen, ‘The Painted,’ pp. 141ff, 183. 39 Society for Combat Archaeology, 2019. 40 The dichotomous distinction will suffice as a shorthand here to indicate the original function of the shield. For classical discussions on 23 ceremonial versus functional weaponry, see B. Molloy, ‘For Gods or Men? A Reappraisal of the Function of European Bronze Age Shields.’ Antiquity 83.322 (2009), 1052–64; H€ arke & Dickinson, 1992. 41 Nicolaysen, 1882, p. 63. 42 O. Nielsen, ‘Skydeforsøg Med Jernalderens Buer,’ in Eksperimentel arkæologi. Studier i teknologi og kultur, ed. by B. Madsen (Lejre: Historisk-Arkæologisk Forsøgscenter, 1991), pp. 135–48; H. Paulsen, ‘B€ ogen und Pfeile,’ in Der Opferplatz von Nydam. Die Funde aus den € alteren Grabungen Nydam-I und Nydam-II, ed. by G. J. Bemman (Neum€ unster: Wachholtz, 1998), pp. 387–427; X. Pauli Jensen, ‘North Germanic Archery. The Practical Approach – Results and Perspectives,’ in Waffen in Aktion. Akten der 16. Internationalen Roman Military Equipment Conference (ROMEC) Xanten, 13.– 16. Juni 2007. Xantener Ber, ed. by H. J. Schalles and A.W. Busch (Mainz, Philipp von Zabern, 2009), p. 16; Warming, ‘Shields and Martial Practices’; Warming, ‘Praksistilgangen,’ pp. 15–23; Warming et al. 2020. 43 Vang Petersen, ‘The Painted,’ p. 156.; Ilkjær, Illerup Ådal, p. 361. 44 Warming et al., 2020, pp. 202ff. 45 Dr. Rene Larsen (pers.com, conservator, 15 August 2022) has through photographic evidence observed that some patches of organic material potentially have a more canvas or textile-like surface. Such fragments (assumedly not from the shields) may stem from the sail or tent aboard the ship and should be submitted to further analyses. 46 This is assuming that the paint observed by Nicolaysen had not been painted on top of the skin product. 47 Vang Petersen, ‘The Painted,’ pp. 141ff; see also, Warming et al., 2020. 48 A. Ringaard, ‘Mere om Vikingeskjolde: Dansk Forsker har nyt om Gokstadskibets Skjolde,’ <https://videnskab.dk/kultur-samfund/vi-vedendelig-hvordan-vikingernes-skjolde-saa-ud> [accessed 30 August 2022]; Society for Combat Archaeology, 2019. 49 O. Crumlin-Pedersen, The Skuldelev Ships: Topography, Archaeology, History, Conservation and Display. Ships and Boats of the North V. 4.1 (Roskilde: The Viking Ship Museum, 2002), pp. 252ff. 50 Warming et al., 2020, pp. 160ff. 51 For recent XRF-analyses, see K. Odeb€ ack, C. C. Steindal and J. Bill, Forthcoming. 52 Odeb€ ack, ‘Vikingatida Sk€ oldar,’ pp. 54f. 53 I. Kopytoff. 'The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditisation as Process,’ in Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, 24 R. F. WARMING ed. by A. Appadurai (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), pp. 64–91; J. Jody. 'Reinvograting Object Biography: Reproducing the Drama of Object Lives,’ World Archaeology, 41.4 (2009), 540–56; Odeb€ ack, 'Vikingatida Sk€ oldar', 72ff. 54 J. Jesch, Ships and Men in the Late Viking Age: The Vocabulary of Runic Inscriptions and Skaldic Verse (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2001), pp. 157ff., 203ff.; R. Warming, ‘An Introduction to Hand-to-Hand Combat at Sea: General Characteristics and Shipborne Technologies from c. 1210 BCE to 1600 CE,’ Ch 6 in On War on Board: Archaeological and Historical Perspectives on Warfare in the Early Modern Period, ed. by J. R€ onnby (Huddinge: S€ odert€ orn University, 2019), pp. 111f. 55 Warming, 2019, p. 103. 56 Cf. Crumlin-Pedersen, The Skuldelev, pp. 262–4. 57 L. Gardeła and K. Odeb€ack, ‘Miniature Shields in the Viking Age: A Re-Assessment,’ Viking and Medieval Scandinavia, 14 (2019), 81–133; Odeb€ack, ‘Vikingatida Sk€ oldar’. 58 A. Lorange, Samlingen af Norske Oldsager i Bergens Museum, ed. by J. D. Beyers Bogtrykkeri (Bergen: Bergen Museum, 1875), p. 155; H. Schetelig, ‘Gravene ved Myklebostad paa Nordfjordeid,’ Bergens Museums Aarbog, 7 (1905), pp. 11–6; H. Schetelig, Vestlandske Graver fra Jernalderen (Bergen: John Griegs Boktrykkeri, 1912), p. 187. 59 Pers.com. Matt Bunker, independent researcher/Wulfheodenas, 13 Aug. 2022; G. Grainger and J. Bayley, eds., The Anglo-Saxon Cemetery at Worthy Park, Kingsworthy, Near Winchester, Hampshire (Oxford: Oxford University School of Archaeology, 2003), pp. 42f., 87, 98, 111. 60 V. Bierbrauer, ‘The Cross Goes North: From Late Antiquity to Merovingian times South and North of the Alps,’ in The Cross Goes North: Processes of Conversion in Northern Europe, AD 300–1300, ed. by M. Carver (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2003), pp. 429–42. 61 Nicolaysen, 1882, pp. 63. 62 For an overview of monumental ship burials, see J. Bill, ‘The Ship Graves on Kormt - and Beyond,’ in Rulership in 1st to 14th Century Scandinavia: Royal Graves and Sites at Avaldsnes and Beyond, ed. by D. Skre (Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2019), pp. 334–7. 63 H. Shetelig, 'Gravene ved Myklebostad paa Nordfjordeid,’ In Bergens Museums Aarbog 7 (Bergen: Bergen Museum, 1905), pp. 3–53; S.Grieg, Gjermundbufunnet. En Høvdingegrav fra 900-årene fra Ringerike, (Oslo: Universitets Oldsaksamling, 1947), pp. 19ff. 64 Holck, ‘The Skeleton,’ pp. 40–9. Notes on contributor Rolf Warming is a Maritime Archaeologist and Prehistoric Archaeologist, currently working as a PhD Student at the Department of Archaeology and Classical Studies, Stockholm University. He is also the founding director of the Society for Combat Archaeology. Correspondence to: Rolf Warming. Email: rolf.fabricius.warming@ark.su.se ORCID Rolf Fabricius Warming http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2479-076X