MBA Handbook: Academic & Professional Skills for Management

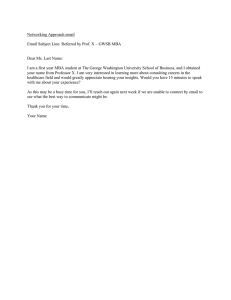

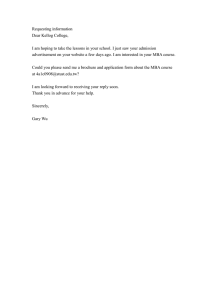

advertisement