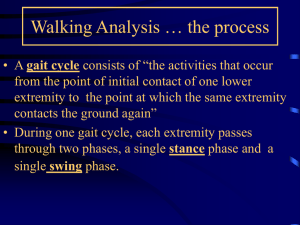

7/8/24, 9:16 PM Running Biomechanics - Physiopedia pPhysiopedia pPhysiopedia About News Contribute Courses Resources Shop Contact Login pPhysiopedia About News Contribute Courses Resources Shop Contact po+ Contents Editors Categories Share Cite Contents 1 The Running Gait Cycle 2 Definitions 3 Joint Motion 4 Muscle Activity 5 Kinematics 6 Elastic Support Strategy 7 Rotation through the Kinetic Chain 8 Multimedia 9 References Original Editor - Joanne Garvey Top Contributors - Joanne Garvey, Kapil Narale, Evan Thomas, George Prudden, WikiSysop, Wanda van Niekerk and Naomi O'Reilly Biomechanics Gait Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics Sports Medicine When refering to evidence in academic writing, you should always try to reference the primary (original) source. That is usually the journal article where the information was first stated. In most cases Physiopedia articles are a secondary source and so should not be used as references. Physiopedia articles are best used to find the original sources of information (see the references list at the bottom of the article). https://www.physio-pedia.com/Running_Biomechanics 1/9 7/8/24, 9:16 PM Running Biomechanics - Physiopedia If you believe that this Physiopedia article is the primary source for the information you are refering to, you can use the button below to access a related citation statement. Cite article Running Biomechanics Jump to:navigation, search Original Editor - Joanne Garvey Top Contributors - Joanne Garvey, Kapil Narale, Evan Thomas, George Prudden, WikiSysop, Wanda van Niekerk and Naomi O'Reilly Contents 1 The Running Gait Cycle 2 Definitions 3 Joint Motion 4 Muscle Activity 5 Kinematics 6 Elastic Support Strategy 7 Rotation through the Kinetic Chain 8 Multimedia 9 References Online Course: Rehabili… Online Course: Commo… Online Course: Running… Rehabilitation of Running Biomechanics Learn how to Biomechanical Errors in Runners Recognize the most common Mechanics for Clinicians Clinical insights from an elite sports Online Course: Rehabilitation of Running Biomechanics Rehabilitation of Running Biomechanics Learn how to create a comprehensive plan of care for runners Start course 1-1.5 hours - - - Powered by Physiopedia Course instructor Ari Kaplan Ari Kaplan is a PT, with specialities in MSK conditions such as headaches, Online Course: Common Biomechanical Errors seen in Runners Biomechanical Errors in Runners Recognize the most common running patterns seen in athletes that can lead to injury Start course 1.5-2 hours - - - - Powered by Physiopedia Course instructor Ari Kaplan Ari Kaplan is a PT, with specialities in MSK conditions such as Online Course: Running Mechanics for Clinicians Mechanics for Clinicians Clinical insights from an elite sports physiotherapist on the biomechanics of running Start course 1-1.5 hours - - - - Powered by Physiopedia Course instructor Chris Bramah An elite-level sports physiotherapist with a specialty in managing Online Course: Running Gait Retraining Gait Retraining The what, why and how of addressing problems experienced by runners Start course 1-1.5 hours - - - - Powered by Physiopedia Course instructor Chris Bramah An elite-level sports physiotherapist with a specialty in managing running-related injuries Online Course: An Introduction to Understanding Your Runner An Introduction to Understanding Your Runner How to delve deeper in the subjective evaluation to find out what motivates your patient to run Start course 1-1.5 hours - - - - Powered by Physiopedia Course instructor Dawn Nunes Dawn is an enthusiastic sportswoman The Running Gait Cycle[ edit | edit source ] Running is similar to walking in terms of locomotor activity. However, there are key differences. Having the ability to walk does not mean that the individual has the ability to run.[1] Running requires: Greater balance https://www.physio-pedia.com/Running_Biomechanics 2/9 7/8/24, 9:16 PM Running Biomechanics - Physiopedia Greater muscle strength Greater joint range of movement Running Gait cycle There is a need for greater balance because the double support period, present during the stance phase of the walking gait cycle, is not present when running. There is the addition of a double float phase, at the beginning and end of the swing phase during the running gait cycle, in which both feet are off the ground. [2] The amount of time that the runner spends in float, increases as the runner increases in speed. The muscles must produce greater energy to elevate the head, arms and trunk (HAT) higher than in normal walking, and to support the HAT during the gait cycle. The muscles and joints, must also be able to absorb increased amounts of energy to control the weight of the HAT. As seen, there is an absorption phase and a generation phase in the stance phase of running. After absorption, the velocity of the center of mass decelerates horizontally. [2] After stance phase reversal, the center of mass is translated upward and forward during stance phase generation. At swing phase reversal, the next period of absorption begins. [2] During the running gait cycle, the ground reaction force (GRF) at the centre of pressure (CoP) have been shown to increase to 250% of the body weight.[3] Definitions[ edit | edit source ] Here is a review of some definitions as they apply to the running gait cycle: The gait cycle begins when one foot comes in contact with the ground and ends when the same foot contacts the ground again. These moments in time are referred to as initial contact. Stance ends when the foot is no longer in contact with the ground. Toe off marks the beginning of the swing phase of the gait cycle - since the runner is moving faster, less time is spent in stance phase, and toe off occurs quicker The timing of toe off depends on speed Double support – when both feet are touching the ground – with walking, there are two phases of double support, one at the beginning of the stance phase, and one at the end of the stance phase With running, toe off occurs before 50% of the gait cycle (40%), and double support does not occur - instead double float occurs, once at the beginning of swing https://www.physio-pedia.com/Running_Biomechanics 3/9 7/8/24, 9:16 PM Running Biomechanics - Physiopedia and at the end of swing As speed increases, time spent in swing increases, stance time decreases, double float increases, and cycle time shortens Absorption and Generation (propulsion) – alternating periods of acceleration and deceleration that occur within the running gait cycle They are not in sync with initial contact and toe off, and occur during loading response. Absorption – the body’s center of mass translates from its peak height during double float The absorption phase is divided by initial contact (IC) into swing phase absorption and stance phase absorption Ground Reaction Force (GRF) is created between the foot and the ground, in which the foot and ground exert an equal and opposite force on each other. The direction and magnitude of the ground reaction force is determined by the position and acceleration of the runner’s center of mass. After maximum velocity is reached, the center of mass moves backward. Someone who tries to accelerate with their body upright would fall backward due to the direction of the GRF. A forward trunk lean and pelvic tilt keep the GRF in a position to allow forward acceleration Joint Motion[ edit | edit source ] Beginning of stance phase - hip is in about 50° flexion at heel strike, continuing to extend during the rest of the stance phase. It reaches 10° of hyperextension after toe off. The hip flexes to 55° flexion in the late swing phase. Before the end of the swing phase, the hip extends to 50° to prepare for the heel strike. The knee flexes to about 40° as the heel strikes, then flexes to 60° during the loading response The knee begins to extend after this, and reaches 40° flexion just before toe-off. During swing phase and the initial part of the float period, the knee flexes to reach maximum flexion of 125° during mid swing. The knee then prepares for heel strike by extending to 40° The ankle is in about 10° of dorsiflexion when the heel strikes, and then dorsiflexes rapidly to 25° of dorsiflexion. Plantarflexion happens almost immediately, continuing throughout the rest of the stance phase of running, and as it enters swing phase also. Plantarflexion reaches a maximum of 25° in the first few seconds of swing phase. The ankle then dorsiflexes throughout the swing phase to 10° in the late stage of swing phase, preparing for heel strike. The lower limb medially rotates during the swing phase, continuing to medially rotate at heel strike. The foot pronates at heel strike. Lateral rotation of the lower limb stance leg begins as the swing leg passes by the stance leg in mid stance position. Muscle Activity[ edit | edit source ] Muscles are most active jus before and just after heel strike. This is a crucial time for muscle contraction, as opposed to when the foot is preparing to leave the ground at toe off. [2] There is a lag of about 50ms between the onset of EMG activity and the facilitation of muscle contraction. In addition, there are also instances where EMG activity is has stopped, while muscles may still be activating. [2] Gluteus maximus and gluteus medius are both active at the beginning of the stance phase, and also at the end of the swing phase. Tensor Fascia Latae (TFL) is active from the beginning of stance, and also the end of swing phase. It is also active between early and mid swing. Adductor Magnus is active for about 25% of cycle, from late stance to the early part of swing phase. Iliopsoas activity occurs during the swing phase, for 35-60% of the cycle. Quadriceps work in an eccentric manner for the initial 10% of the stance phase. Their role is to control knee flexion as the knee goes through rapid flexion. Its activity stops after the first part of the stance phase, and it remains inactive until the last 20% of the swing phase. At this point, the quadriceps change to a concentric action, for the knee to extend in preparation for heel strike. Medial Hamstrings become active at the beginning of the stance phase (18-28% of stance). They are also active throughout much of the swing phase (40-58% of initial swing, then the last 20% of swing). They act to extend the hip and control the knee through a concentric contraction. In late swing, the hamstrings act eccentrically to control knee extension and take the hip into extension again. Gastrocnemius muscle activity starts just after loading at heel strike, remaining active until 15% of the gait cycle (this is where its activity begins in walking). It then re-starts its activity in the last 15% of the swing phase in preparation for heel strike. Tibialis Anterior (TA) muscle is active through both stance and swing phases in running. It is active for about 73% of the cycle (compared to 54% when walking). The swing phase when running is 62% of the total gait cycle, compared to 40% when walking, so TA is considerably more active when running. Its activity is mainly concentric or isometric, enabling the foot to clear the support surface during the swing phase of the running gait. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Running_Biomechanics 4/9 7/8/24, 9:16 PM Running Biomechanics - Physiopedia Kinematics[ edit | edit source ] Sagittal Plane Kinematics - when comparing walking, running, and sprinting, there is a shift into flexion, as motion progresses, as well as lowering of the center of mass.[2] Although a greater amount of pelvic tilt may be expected with increasing speed, pelvis tilt remains relatively consistent between the different gait speeds. This occurs to maintain energy and the efficiency with running or sprinting. [2] Despite the minimal changes, as speed increases, there is a forward tilt in the pelvis and trunk, the center of mass is lowered, and the horizontal force produced in the propulsion phase is the greatest. [2] Elastic Support Strategy[ edit | edit source ] Joanne Elphinstone (2013) [4] describes this as a mechanism for transferring force from the lower control zone to the upper control zone and back again. In runners, the diagonal elastic support mechanism is utilised. This is produced by a constant diagonal stretch and release that is enabled by the body's counter rotation. The force continually flows up and down these force pathways alternately. The pattern of force distribution prevents force being concentrated in one area, but allows wide distribution of force throughout the body. Elphinsone [4] maintains that it is crucial to have a well functioning central core area to allow this pattern of force distribution to take place efficiently. Rotation through the Kinetic Chain[ edit | edit source ] https://www.physio-pedia.com/Running_Biomechanics 5/9 7/8/24, 9:16 PM Running Biomechanics - Physiopedia The kinetic chain can be described as a series of joint movements, that make up a larger movement. Running mainly uses sagittal movements as the arms and legs move forwards. However, there is also a rotational component as the joints of the leg lock to support the body weight on each side. There is also an element of counter pelvic rotation as the chest moves forward on the opposite side. This rotation is produced at the spine, which is often referred to as the spinal engine. This is also linked to running economy [4]. This counter rotation enables the spinal forces to be dissipated as the foot hits the ground. Runners may complain of a feeling of restriction in hamstrings or shoulders, however, when examined it may be found that there is actually limitation in rotation of the pelvis, causing the problem. Multimedia[ edit | edit source ] The Running Gait Cycle Made Simple - … Muscle contributions to fore-aft and vertical body mass center accelerations over a range of running speeds What is The Windlass Mechanism of T… T… Rules to Follow to Return to Running Af… Af… Samuel Hamner 00:26 700+ accredited online courses for clinicians Join the world's largest community of rehabilitation professionals Learn more on this topic https://www.physio-pedia.com/Running_Biomechanics 6/9 7/8/24, 9:16 PM Running Biomechanics - Physiopedia Related articles Assessment of Running Biomechanics - Physiopedia Introduction Running is a popular sport worldwide, but while it is a positive way of enhancing health and fitness, it is associated with a high risk of injury. Up to 50% of people who run regularly, will experience more than one injury each year.[1] Out of all the types of aerobic exercises, running is Gait - Physiopedia Introduction Gait is defined as the walking pattern in humans.[1] It is further described as particular manner of moving on foot which can be a walk, jog or run. [2] Human gait depends on a complex interplay of major parts of the nervous, musculoskeletal and cardiorespiratory systems. The Gait Deviations Associated with Pelvis and Knee Pain Syndromes - Physiopedia Introduction This article discusses gait deviations associated with pain syndromes in the pelvis and knee. While this information focuses on certain regions of the body, remember that the human body functions within a kinetic chain. No one movement is ever completely isolated and without Foot and Ankle Structure and Function - Physiopedia Anatomy The foot and ankle form a complex system which consists of 28 bones, 33 joints, 112 ligaments, controlled by 13 extrinsic and 21 intrinsic muscles. The foot is subdivided into the rearfoot, midfoot, and forefoot. It functions as a rigid structure for weight bearing and it can also function as PII: S0966-6362(97)00038-6 [1] Encyclopedia Britannica, 1952:234. [2] Cavanagh PR. The mechanics of distance running: a historical perspective. In: Cavanagh PR, editor. Biomechanics of Distance Running. Champaign, IL, Human Kinetics Publishers, 1990; Chapter 1:1–34. [3] Hanks GA, Kalenak A. Running injuries. References[ edit | edit source ] 1. Norkin C; Levangie P; Joint Structure and Function; A comprehensive analysis; 2nd;'92; Davis Company. 2. Novacheck TF; The Biomechanics of running; Gait and Posture 7; 1998; 77-95 3. Mann RA: Biomechanics of running. In D' Ambrosia, RD and Drez D: Prevention and treatment of running injuries, ed 2. Slack, New Jersey, 1989 4. Elphinsone J; Stability, sport and performance movement 2nd ed; 2013; Lotus Publishing. pg 19. Retrieved from "https://www.physio-pedia.com/index.php?title=Running_Biomechanics&oldid=327805" : Biomechanics Gait Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics Sports Medicine Get Top Tips Tuesday and The Latest Physiopedia updates Enter your email address I give my consent to Physiopedia to be in touch with me via email using the information I have provided in this form for the purpose of news, updates and marketing. HP Yes please It's free, and you can unsubscribe any time. Privacy policy. Our Partners https://www.physio-pedia.com/Running_Biomechanics 7/9 7/8/24, 9:16 PM Running Biomechanics - Physiopedia The content on or accessible through Physiopedia is for informational purposes only. Physiopedia is not a substitute for professional advice or expert medical services from a qualified healthcare provider. Read more pPhysiopedia oPhysiospot +Plus https://www.physio-pedia.com/Running_Biomechanics 8/9 7/8/24, 9:16 PM Running Biomechanics - Physiopedia Physiopedia About News Donations Shop Contact Content Articles Categories Resources Projects Contribute Courses Legal Disclaimer Terms Privacy Cookies AI Licensing Physiopedia available in: French German Italian Spanish Ukrainian © Physiopedia 2024 | Physiopedia is a registered charity in the UK, no. 1173185 https://www.physio-pedia.com/Running_Biomechanics 9/9