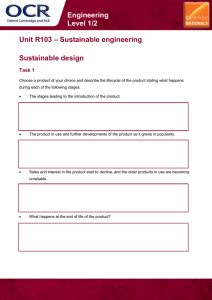

Planned Obsolescence & Sustainable Smartphone Consumption

advertisement