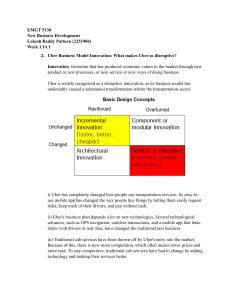

V viewpoints DOI:10.1145/3372918 Michael A. Cusumano Technology Strategy and Management ‘Platformizing’ a Bad Business Does Not Make It a Good Business Transaction platforms link third-party applications and services providers with users. U as well as Airbnb, WeWork (We Co.), and other sharing-economy startups, offer valuable services, albeit with different levels of financial success (see “The Sharing Economy Meets Reality, Communications, January 2018). What most of these ventures have in common is they function as transaction platforms. That is, they bring together two or more market sides to exchange information, goods, or services, including advertisements. The businesses can grow rapidly through the power of network effects whereby one market actor (for example, sellers) attracts another side (for example, buyers) in a self-reinforcing positive feedback loop. The more populated one side becomes, the more value and participation we see on the other side. Transaction platforms contrast with innovation platforms, such as Microsoft Windows, Apple iOS, Google Android, or the Facebook and WeChat APIs. These foundational products or technologies generate network effects by linking users with third-party providers of applications and services.5 All platforms connect multiple market participants and can get big fast if they generate strong network effects and do not have a lot of digital or conventional competition. But there IMAGE BY AND RIJ BORYS ASSOCIAT ES, USING SH UTT ERSTOC K BER AND LYFT, are significant differences in business models. Microsoft and Apple mostly sell products. Google gives away software and digital services but then sells advertisements. Airbnb matches people with rooms for rent to possible renters and charges a fee when a match occurs. WeWork is really a “onesided company platform” in that it leases office space and then resells it on short-term arrangements. The most valuable publicly listed firms in the world today—Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Alphabet-Google, Facebook, Alibaba, and Tencent—are all “hybrids” that combine transaction and innovation platforms. Several colleagues and I recently measured their performance, comparing the largest 43 publicly listed platform companies to 100 of the largest firms in the same businesses over a 20-year period. They all had comparable annual revenues in 2015 (the year we compiled our list) of between $4.3 billion and $4.8 billion. But platforms achieved these sales with half the JA N UA RY 2 0 2 0 | VO L. 6 3 | N O. 1 | C OM M U N IC AT ION S OF T HE ACM 23 viewpoints Median values for Forbes Global 2000 industry control sample and platforms, 1995–2015. Variable Industry Control Sample Innovation and Transaction Platforms Number of Firms 100 43 Sales (Million$) $4,845 $4,335 Employees 19,000 9,872* Operating Profit % 12% 21%* Market Value (Million$) $8,243 $21,726* Mkt Value-Sales Multiple 1.94 5.35* Sales Growth vs. Prior Year 9% 18%* Observations 1,018 374 Source: Michael A. Cusumano, Annabelle Gawer, and David B. Yoffie, The Business of Platforms (2019), p.23. Notes: * Differences significant at p < 0.001 for Industry Sample vs. Platforms using two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney) test. Mkt Value-Sales Multiple = ratio of market value compared to prior year sales. Average of 13 years of data for 18 innovation platforms and five years for 25 transaction platforms. number of employees, generated nearly twice the operating profits, had market values more than twice as high, and were growing about twice as fast (see the accompanying table). Not surprisingly, investors and entrepreneurs keep looking for the next blockbuster platform. In fact, we estimate 60% to 70% of the billion-dollar private “unicorn” companies are platform ventures.5 But “platformizing” (creating a platform) in a “bad” business (an industry with low profit margins due to high costs, low entry barriers, or other structural factors) does not make it a good business. Profits depend on supply and demand, which impact prices, as well as economies of scale and scope or other efficiencies, which impact costs. Moreover, a business that delivers a physical good or service is unlikely to generate the same high profits as a platform that sells digital goods such as software, content, or advertisements, which have close to zero marginal costs. Let’s look more carefully at Uber, the most valuable sharing-economy platform. It went public in May 2019 and has since seen its stock price drop sharply, even though Uber remains a compelling and convenient service. Uber users can summon a ride, usually within minutes, track the driver’s progress, and then pay, all via a smartphone app. Uber and other ride-sharing companies also usually charge less than taxis to attract riders. Each additional driver adds value because transportation options for riders increase. Uber also owns no cars, so its capital costs are minimal. Nevertheless, Uber lost $4.5 billion in 2017 and $1.8 24 COMM UNICATIO NS O F THE ACM billion in 2018 (with income boosted from selling some overseas operations). For the first six months of 2019, Uber reported sales of $6.2 billion and operating losses of $6.5 billion, including costs related to the IPO.12 Uber has been raising prices and cutting staff, yet operating losses in the billions are expected to continue.3 Why does a company with such a valuable service lose so much money? First, Uber (like Lyft and WeWork) is not really a digital business. Only the transaction process is digital. Transporting people or goods is a physical service with potentially high costs. In this case, Uber must pay a lot of money to find drivers, and it keeps prices low to attract riders. In addition, Uber’s economies of scale and scope are primarily local since each area needs its own drivers. Second, a platform rather than a traditional product or service company should bring together two or more market sides, rely on network effects to grow, and then charge for a product or transaction fee without the expense of having the same number of employees or large capital investments as a conventional business. Uber’s platform works best if the driver side is heavily populated so that customers can always get a ride quickly when they need one. However, Uber drivers frequently quit because of long hours and low compensation, with no employee benefits since they are independent contractors. According to data released prior to its IPO, Uber drivers were quitting at a rate of 12.5% per month and the company had to pay approximately $650 to hire each new driver. With at least three mil- | JA NUA RY 2020 | VO L . 63 | NO. 1 lion drivers, this meant Uber had to find 375,000 new drivers every month and replace all its drivers every eight months. Driver costs before commissions on rides were almost $250 million per month or nearly $3 billion per year.2 In short, Uber has been massively subsidizing both sides of its platform—large payments to drivers as well as low fares to riders. This is a great way to lose a lot of money. Lyft loses less money ($911 million in 2018 on sales of $2.2 billion, and $1.14 billion on sales of $776 million in the first quarter of 2019, including IPOrelated stock-compensation charges) mainly because it is smaller.4 WeWork lost $1.9 billion in 2018 on $1.8 billion in revenues and postponed its IPO after losses of $690 million on revenues of $1.5 billion in the first six months of 2019.6 By contrast, Airbnb, which plans to go public in 2020, consistently reports profits or at least a positive cash flow.9 Why? Because Airbnb can charge both sides of its platform. It does not pay people to list rooms or to rent real estate on its supply side, and it allows renters to charge market prices. Uber pays drivers even when they do not have riders. WeWork pays for real estate even when it does not have renters (and, like Uber, it generally has charged well below the market price in order to grow quickly). Why would investors put their money into businesses that consistently lose money? In the case of Uber, investors must be hoping for a “winner take all or most” outcome. Once competitors have disappeared, then Uber can raise prices to riders and reduce payments to drivers. But Uber already has 70% of the U.S. ride-sharing market and it still does not have enough market power or operating efficiencies to turn a profit. At least in part this is because of high driver turnover and the fact that, in most cities, there are still too many transportation options (including people using their own vehicles). Uber makes a profit mainly in a few cities where taxis and other transport options are limited and expensive. Uber has also attracted investors with the promise it will become the “Amazon of transportation” and move into nearly every transportation segment.1 But expansion into more “bad” businesses simply means the bigger the platform gets, the more money it will lose. Amazon took many years to make a profit and viewpoints funded much of its growth through cash flow from its global online store and then a marketplace matching buyers and sellers, with high fees for fulfillment services and advertising. Still, most of Amazon’s profit (nearly 60% in 2019) comes from a highly profitable digital service and innovation platform: Amazon Web Services (see “The Cloud as an Innovation Platform for Software Development,” Communications, October 2019). Transporting food is slightly more profitable than transporting people.2 But Amazon tried and failed to make money in food transport and recently closed down Amazon Restaurants.11 Deliveroo is the market leader in the U.K. and Europe but it also has failed to earn a profit in food transport.10 Another option for Uber is to get rid of drivers (its main cost) by investing in driverless vehicles. This strategy may work someday in some locations. But Uber will most likely run out of cash long before driverless vehicles become safe and commonplace. Moreover, someone still has to own the vehicles. Let’s say Uber buys two million vehicles to replace its three to four million drivers. Even at $50,000 per vehicle, that would be a massive expense of $100 billion. Then there are maintenance, recharging, replacement, or leasing costs. The economics may still be better than constantly subsidizing drivers and riders. However, there will also likely be more competition. Every major automaker in the world, as well as Lyft and Google Waymo, are in or planning to enter the markets for ridesharing and driverless vehicles, with the goal of “selling miles, not cars.”7 Uber and Lyft should stay with the platform strategy rather than own or lease their vehicles, but their ongoing losses may force them to get smaller before they can get bigger again. Ridesharing platforms should focus on the few cities where taxis and transportation options are expensive and in short supply, and then expand gradually into other geographies and transportation segments, such as partnerships with public transportation authorities to bring people from their homes to masstransit facilities. Uber already is exploring such partnerships, and it has sold several unprofitable overseas subsidiaries. It also seems to be making some money matching shippers with truckers in a new marketplace venture. However, Expansion into more “bad” businesses simply means the bigger the platform gets, the more money it will lose. there is nothing to stop more companies and entrepreneurs from entering the transportation business. Taxi companies can also develop their own smartphone apps and expand their operations and partnerships (see “How Traditional Firms Must Compete in the Sharing Economy,” Communications, January 2015). As for WeWork, it must raise prices much more to cover its costs, and that will depress demand. Landlords are also now hesitant to lease properties to WeWork, putting the whole business at risk.8 Meanwhile, Airbnb is likely to continue its strong business model, although there is nothing to stop traditional hotel companies from aggressively entering roomsharing—if it is a “good” (that is, profitable) business.13 References 1. Bond, S. Uber aims to be the ‘Amazon of transportation.’ Financial Times (Oct. 25, 2018). 2. CB Insights. How Uber makes money. (2018), 6–23. 3. Clark, K. Uber lost more than $5B last quarter. Techcrunch (Aug. 8, 2019). 4. Conger, K. Lyft’s first results after I.P.O. show $1.14 billion loss. New York Times (May 7, 2019). 5. Cusumano, M.A., Gawer, A., and Yoffie, D.B. The Business of Platforms: Strategy in the Age of Digital Competition, Innovation, and Power (2019), 18–20. 6. Farrell, M. WeWork IPO filing reveals huge revenue and losses. Wall Street Journal (Aug. 14, 2019). 7. Gindrat, R. Automakers envision a business model for AVs: Selling miles, not cars. Axios.com (Apr. 17, 2019). 8. Grant, P. and Morris, K. Virtually no one will lease to WeWork. That’s a drag on NYC’s office market. Wall Street Journal (Sept. 29, 2019). 9. Prang, A. Airbnb plans to go public next year. Wall Street Journal (Sept. 19, 2019). 10. Satariano, A. Deliveroo takes a kitchen sink approach to food apps. Bloomberg.com (Jan. 15, 2018). 11. Soper, T. Amazon to shut down its Amazon restaurants business in the U.S. Geekwire (June 10, 2019). 12. Uber Technologies, Inc. Form 10-Q (June 30, 2019). 13. Weed, J. Blurring lines, hotels get into the homesharing business. New York Times (July 2, 2018). Michael A. Cusumano (cusumano@mit.edu) is a professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management doing research on computing platforms for business and coauthor of The Business of Platforms: Strategy in the Age of Digital Competition, Innovation, and Power (Harper Business, 2019). Calendar of Events Jan. 6–8 Group ’20: The 2020 ACM International Conference on Supporting Group Work, Sanibel Island, FL, Sponsored: ACM/SIG, Contact: Louis Barkhus, Email: barkhuus@itu.dk Jan. 13–16 ASPDAC ’20: 25th Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference, Beijing, China, Contact: Huazhong Yang, Email: yanghz@tsinghua.edu.cn Jan. 19–25 POPL ’20: The 47th Annual ACM SIGPLAN Symposium on Principles of Programming Language, New Orleans, LA, Sponsored: ACM/SIG, Contact: Brigitte Pientka, Email: bpientka@cs.mcgill.ca Jan. 20–21 CPP ’20: 9th ACM SIGPLAN International Conference on Certified Programs and Proofs, New Orleans, LA, Sponsored: ACM/SIG, Contact: Jasmin Christian Blanchette, Email: j.c.blanchette@vu.nl Jan. 21 PLMW@POPL ’20: Programming Languages Mentoring Workshop at PLMW, New Orleans, LA, Sponsored: ACM/SIG, Contact: Justin Hsu, Email: email@justinh.su Jan. 27–31 AFIRM ’20: ACM SIGIR/SIGKDD Africa School on Machine Learning for Data Mining and Search, Cape Town, South Africa, Sponsored: ACM/SIG, Contact: Tamer Mohamed Elsayed, Email: telsayed@qu.edu.qa Jan. 27–30 ACM FAT* ’20: Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Barcelona, Spain, Sponsored: ACM/SIG, Contact: Carlos A. Castillo, Email: chato@chato.cl Copyright held by author. JA N UA RY 2 0 2 0 | VO L. 6 3 | N O. 1 | C OM M U N IC AT ION S OF T HE ACM 25