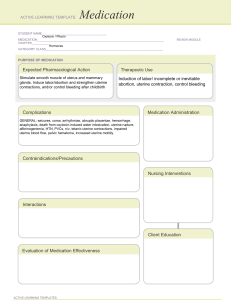

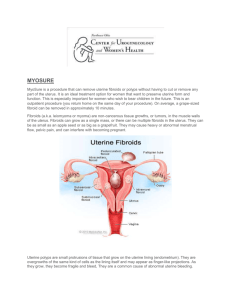

RABIL, ANGEL BAE D. BSPHARMACY-V1A HUMAN REPRODUCTION: REPRODUCTIVE DISORDER Uterine Leiomyomata Uterine leiomyomata or fibroids are an extremely common benign neoplasm in women of reproductive age. Although they are benign, they can have a significant impact on the everyday physical and mental well-being of women with this condition (Barjon & Mikhail, 2023). Fibroids originate from uterine smooth muscle cells (myometrium) whose growth is primarily dependent on circulating estrogen levels. Further information regarding the pathogenesis of fibroids is poorly understood. Fibroids can either present as an asymptomatic incidental finding on imaging or symptomatically. Common symptoms include abnormal uterine bleeding, pelvic pain, disruption of surrounding pelvic structures (bowel and bladder), and back pain (Lewis et al., 2018). Uterine fibroids typically are seen in three significant locations: subserosal (outside the uterus), intramural (inside the myometrium), and submucosal (Inside the uterine cavity). They can further be broken down into pedunculated or not (Islam et al., 2017). Physiopathology of Uterine Fibroids The cause of uterine leiomyomata is idiopathic to date. However, several hypotheses have been postulated, namely: Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase studies suggest that each leiomyoma is unicellular in monoclonal origin [2]. Hence, this implies a genetic probability for the growth of uterine (Tochie et al., 2021). Increment in the exposure of circulating oestrogens is another hypothesis for the growth of uterine fibroids. Effectively, leiomyomas contain oestrogen receptors in higher concentrations than the surrounding myometrium. But at lower concentrations than the endometrium, this oestrogen may contribute to tumour enlargement by increasing the production of extracellular matrix. On the other hand, progesterone increases the mitotic activity of myomas in young women. It may allow for tumour enlargement by down-regulating apoptosis in the fibroids [16]. They usually decrease in size after menopause and whenever myomas grow after menopause, malignancy must be seriously considered. Malignant transformation of leiomyomas is very rare, seen in 0.04% of women having uterine fibroids. In a review of 13,000 leiomyomas, 38 cases (0.29%) demonstrated malignant manifestations. A second study reported that malignant change developed in less than 0.13% of uterine leiomyomas. The diagnosis of leiomyosarcomas is based on the counts of 10 or more mitotic figures per 10 HPFs. Atypical leiomyoma is differentiated from leiomyosarcoma by a lack of necrotizing tumor cells and a mitotic count of less than 7 per 10 HPFs. Nuclear atypia makes the difference with mitotically active leiomyoma. Diagnosis Most of the time, leiomyomas are asymptomatic. Symptoms are found only in about 35–50% of the patients. They vary according to the type, location, size, number and vascular supply of the fibroids. These include: Bleeding -Abnormal uterine bleeding is the most common symptom, occurring during menstrual periods with heavy and prolonged menses or as light spotting before and after periods. This occurs in 47.7% of cases, largely due to the development or dilatation of endometrial venules. Pain- It may result from various factors including red degeneration, infarction, or torsion of a uterine fibroid, leading to pelvic heaviness or fullness, and a feeling of a mass in the pelvis, especially with large tumors. Pressure- effects include compression on the bladder leading to frequent micturition, urinary incontinence, compression on the ureters, leading to hydrometers, and increased rectal pressure causing constipation or tenesmus. The relationship between fibroids and infertility is not clear, potentially impacting fertility in up to 10% of cases due to impaired implantation, tubal function, or sperm transport. Medical Therapy Hormonal Contraceptives. Women who use combined oral contraceptives have significantly less self-reported menstrual blood loss after 12 months compared with placebo.33 However, the levonorgestrel-releasing intra-uterine system (Mirena) results in a significantly greater reduction in menstrual blood loss at 12 months vs. oral contraceptives (mean reduction = 91% vs. 13% per cycle; P < .001). Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs. Another medical option for the treatment of uterine fibroids is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. These agents significantly reduce blood loss (mean reduction = 124 mL per cycle; 95% CI, 62 to 186 mL) and improve pain relief compared with placebo,34 but are less effective in decreasing blood loss compared with the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system or tranexamic acid at three months. Hormone Therapy. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists and selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRMs) are options for patients who need temporary relief from symptoms preoperatively or who are approaching menopause. Preoperative administration of GnRH agonists (e.g., leuprolide [Lupron], goserelin [Zoladex], triptorelin [Trelstar Depot]) increases hemoglobin levels preoperatively by 1.0 g per dL (10 g per L) and postoperatively by 0.8 g per dL (8 g per L), as well as significantly decreases pelvic symptom scores. Surgery Hysterectomy. Hysterectomy provides a definitive cure for women with symptomatic fibroids who do not wish to preserve fertility, resulting in complete resolution of symptoms and improved quality of life. Myomectomy. Hysteroscopic myomectomy is the preferred surgical procedure for women with submucosal fibroids who wish to preserve their uterus or fertility. Uterine Artery Embolization. Uterine artery embolization is an option for women who wish to preserve their uterus or avoid surgery because of medical comorbidities or personal preference.4 It is an interventional radiologic procedure in which occluding agents are injected into one or both of the uterine arteries, limiting blood supply to the uterus and fibroids. REFERENCES Barjon, K., & Mikhail, L. N. (2023, August 7). Uterine Leiomyomata. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546680/ Islam, M. S., Ciavattini, A., Petraglia, F., Castellucci, M., & Ciarmela, P. (2017). Extracellular matrix in uterine leiomyoma pathogenesis: a potential target for future therapeutics. Human Reproduction Update, 24(1), 59–85. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmx032 Lewis, T. D., Malik, M., Britten, J., Pablo, A. M. S., & Catherino, W. H. (2018). A Comprehensive review of the pharmacologic management of uterine leiomyoma. BioMed Research International, 2018, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/2414609 Ramaiyer, M. S., Saad, E., Kurt, I., & Borahay, M. A. (2024). Genetic mechanisms driving uterine leiomyoma Pathobiology, Epidemiology, and Treatment. Genes, 15(5), 558. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes15050558 Tochie, J. N., Badjang, G. T., Ayissi, G., & Dohbit, J. S. (2021). Physiopathology and management of uterine fibroids. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.94162 In IntechOpen eBooks.