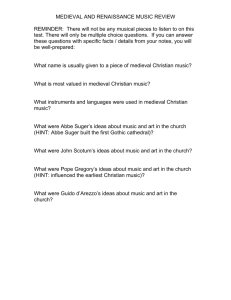

Medieval Christianity in the North ACTA SCANDINAVICA Aberdeen Studies in the Scandinavian World A series devoted to early Scandinavian culture, history, language, and literature, between the fall of Rome and the emergence of the modern states (seventeenth century) – that is, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and the Early Modern period (c. 400–1600). General Editor Stefan Brink, University of Aberdeen Editorial Advisory Board under the auspices of the Centre for Scandinavian Studies, University of Aberdeen Maria Ågren (History), Uppsala universitet Pernille Hermann (Literature), Aarhus Universitet Terry Gunnell (Folklore), Háskóli Íslands (University of Iceland) Judith Jesch (Old Norse/Runology), University of Nottingham Jens Peter Schjødt (History of Religions), Aarhus Universitet Dagfinn Skre (Archaeology), Universitetet i Oslo Jørn Øyrehagen Sunde (Law), Universitetet i Bergen Volume 1 Medieval Christianity in the North New Studies Edited by Kirsi Salonen, Kurt Villads Jensen, and Torstein Jørgensen British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Medieval Christianity in the North : new studies. -- (Acta Scandinavica ; 1) 1. Scandinavia--Church history. 2. Church history--Middle Ages, 600-1500. 3. Conversion--Christianity--History--To 1500. 4. Ecclesiastical law--Scandinavia--History--To 1500. I. Series II. Salonen, Kirsi editor of compilation. III. Jensen, Kurt Villads editor of compilation. IV. Jorgensen, Torstein, 1951- editor of compilation. 274.8'03-dc23 ISBN-13: 9782503540481 © 2013, Brepols Publishers n.v., Turnhout, Belgium All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. D/2013/0095/98 ISBN: 978-2-503-54048-1 e-ISBN: 978-2-503-54053-5 Printed on acid-free paper Contents Illustrations vii Preface xi Introduction Kurt Villads Jensen, Torstein Jørgensen, and Kirsi Salonen Remnants of Old Norse Heathendom in Popular Religion in Christian Times Else Mundal Early Ecclesiastical Organization of Scandinavia, Especially Sweden Stefan Brink Canonical Observance in Norway in the Middle Ages: The Observance of Dietary Regulations Sæbjørg Walaker Nordeide and Jennifer R. McDonald Wine and Beer in Medieval Scandinavia Lars Bisgaard Martyrs, Total War, and Heavenly Horses: Scandinavia as Centre and Periphery in the Expansion of Medieval Christendom Kurt Villads Jensen The Making of New Cultural Landscapes in the Medieval Baltic Torben Kjersgaard Nielsen 1 7 23 41 67 89 121 Contents vi The Emerging Birgittine Movement and the First Steps towards the Canonization of Saint Birgitta of Sweden Claes Gejrot Forbidden Marital Strategies: Papal Marriage Dispensations for Scandinavian Couples in the Later Middle Ages Kirsi Salonen ‘He Grabbed his Axe and Gave Thore a Blow to his Head’: Late Medieval Clerical Violence in Norway as Treated according to Canon and Civil Laws Torstein Jørgensen The Lars Vit Case: A Fragmentary Example of Swedish Ecclesiastical Legal Practice and Sexual Mentality at the Beginning of the Fifteenth Century Bertil Nilsson Concluding Remarks Patrick Geary 155 181 209 237 261 Index of Persons 269 Index of Places 273 Illustrations Figures Figure 1, p. 29. Burial ground in Björned, Torsåker parish. Figure 2, p. 56. Archbishop Olav Engelbrektsson’s menu for his men at Steinvik­ holm Castle in the 1530s. Figure 3, p. 73. Danish medieval drinking horn, from the guild of the Holy Trinity in Flensburg. Figure 4, p. 78. Statutes of the cooper’s guild, Malmö, 1503. Figure 5, p. 84. The three magi, one with drinking horn. Fresco in Vesterø church, Denmark, early sixteenth century. Figure 6, p. 94. The Jelling stone, 980s. Figure 7, p. 109. Reconstruction of tiles from the Cistercian monastery of Øm in Denmark. Probably thirteenth century. Figure 8, p. 168. The seal of the Bishop of Linköping, Nils Hermansson. Figure 9, p. 174. Saint Birgitta’s daughter Katarina writes to the archbishop of Uppsala, Birger Gregersson. Figure 10, p. 220. Priestly violence. BAV, MS Vat. lat. 1371, fol. 159r. Graphs Graph 1, p. 57. The relation in per cent between the number of mammal, fish, and bird bones found in the Archbishop’s Palace, Trondheim. Graph 2, p. 58. The relation in per cent between the number of mammal, fish, and bird bones found in aunceston Castle. Graph 3, p. 193. Scandinavian marriage graces in time-axis. viii ILLUSTRATIONS Maps Frontispiece, p. x. The geopolitical and ecclesiastical situation in Scandinavia and the Baltics during the early Middle Ages. Map 1, p. 24. Early Christian Burials in Scandinavia. Map 2, p. 24. Early Churches in Scandinavia. Map 3, p. 45. The Norwegian medieval law districts. Map 4, p. 107. The Wendish areas around Mecklenburg. Tables Table 1, p. 51. Number of graves with various animal species recorded from Merovingian period/Viking Age in the Oslofjord region. Table 2, p. 54. Number of bones of various mammals, fish, and birds recorded from occupation layers in Trondheim and Kaupang. Table 3, p. 190. The provenance of the Nordic marriage supplications. Archbishopric Episcopal see NIDAROS NORWAY Hamar Bergen K a r e lia n s SWEDEN Oslo Åbo/Turku UPPSALA Västerås Reval Stavanger E st o n ia n s Strängnäs ron LUND DENMARK Riga S em gal l i ans Lit Let gal l i ans hu an Samland S el oni ans ian sian s Roskilde Odense Växjö Cu Århus ian Viborg Ribe L ivs Letts Rus Linköping Børglum s Dorpat Skara s Slesvig Saxons HAMBURG Rugi ans A b o tr i tes Po l abi ans Pom erani ans P r u ssia n s Po l e s Frontispiece: The geopolitical and ecclesiastical situation in Scandinavia and the Baltics during the early Middle Ages (approx. ninth to fourteenth centuries), with the major archbishoprics: Lund (1103/4; episcopal see c. 1050), Uppsala (1164; episcopal see c. 1140), Nidaros (1152/3; episcopal see late eleventh century), and the episcopal sees: Slesvig (948), Ribe (948), Århus (948), Odense (988), Roskilde (c. 1020), Viborg (1060), Skara (c. 1060; according to tradition 1014), Børglum (c. 1060), Oslo (late eleventh century), Bergen (late eleventh century), Stavanger (c. 1125), Linköping (early twelfth century), Västerås (early twelfth century), Strängnäs (early twelfth century), Hamar (1152/3), Växjö (first mentioned in 1170), Riga (1199), Reval/Tallinn (c. 1219), Dorpat/Tartu (c. 1224), Åbo/Turku (mid thirteenth century). Preface T he Nordic Centre for Medieval Studies (NCMS) was a Nordic Centre of Excellence comprising the universities of Bergen, Gothenburg, Helsinki, and Southern Denmark (Odense); it was financed for the fiveyear period 2005–10 by NOS-HS, the Joint Committee for Nordic research councils for the Humanities and Social Sciences (Nordisk samarbeidsnemnd for humanistisk og samfunnsvitenskapelig forskning). NCMS based its work and achievements on three teams: Religion, Culture, and State Formation, each commissioned to promote new trends of historical research in Scandinavia via topics assigned to each team. The leading idea of the NCMS research was to expand the perspective to include all of Scandinavia and to challenge traditional interpretations with a narrowly nationalist focus. Equally, the project stressed a comparative approach to areas outside Scandinavia as well. Each of the three teams planned their work independently of each other but also, to a large extent, engaged in close collaboration during the five-year period of operation. The teams organized a number of conferences and workshops (the proceedings from most of which have been published), invited external scholars to contribute to the research nodes, and sent scholars to the other thematic nodes as well as to national and international conferences. The activity of the Religion team was overseen by two team leaders, Kurt Villads Jensen and Torstein Jørgensen. In addition to the two leaders, the team consisted of experts from different fields of research. Most team members were scholars attached to the four main nodes of the NCMS structure, but some had been recruited from other institutions (universities, museums, research institutes, archives). They represented all five Nordic countries and different disciplines such as philology, literature, history, archaeology, and theology. The structure of the team was flexible in the sense that the number of team members varied between eleven and fifteen over the course of the years. Some left the team because of appoint- xii Preface ments in other countries, and new members were invited when necessary. The contributors to this publication were all members of the team, but the list of authors does not cover all team members, as some were unable to contribute. The task entrusted to the Religion team was to study the religious element of the Scandinavian Middle Ages by concentrating on three main research topics: 1) the dynamics of the conversion to Christianity of the Nordic countries, 2) the penetration of Christianity into different layers of Scandinavian societies throughout the Middle Ages (especially with the focus on sacralization, religious conservatism vs. modernism, and liminality), and 3) the application of canon law in Scandinavia. This book is a joint attempt by the Religion team members to contribute to the new trends in Scandinavian history research. It is not a conference publication but consists of articles by the participants on themes of their own research within the activity of the NCMS — ideas that have been presented and discussed in various internal workshops and seminars as part of the common activities of the team. Introduction Kurt Villads Jensen, Torstein Jørgensen, and Kirsi Salonen T his book, produced by the Religion team of the Nordic Centre for Medieval Studies (NCMS),1 aims to demonstrate how medieval Latin Christianity in Scandinavia incorporated influences from Nordic beliefs and customs. It thus contributes to discussions of the relation of the Nordic countries to the rest of Europe and Latin Christendom during the Middle Ages. Previously, Nordic societies have often been considered to be far-off, strange, undeveloped areas, whose inhabitants, with the help of Christianization, were finally — albeit slowly — transformed from harsh and uncivilized Vikings into ‘proper’ human beings — into true Europeans.2 Such a picture is obviously a caricature, but the idea of Scandinavia as an under-developed hinterland that was integrated with Europe only upon the arrival of the new faith is nonetheless very common. A similarly common and stereotypical view is that, with the arrival of Christianity, Scandinavians simply accepted and assimilated everything new into their culture, and that everything new constituted an improvement. The aim of this book is to challenge such misconceptions and, through the study of various aspects of Scandinavian medieval culture, to analyse the extent to which Scandinavians imported and accepted all foreign ideas and habits: did they assimilate or even refashion the new ideas to correspond to their existing cultures, or did they actively contribute, by producing something entirely new, 1 NCMS was a Nordic Centre of Excellence. See A Nordic Centre of Excellence <http:// www.uib.no/ncms/> [accessed 30 January 2013]. 2 The influential book by Bartlett, The Making of Europe, is built on this idea of cultural transfer to the peripheries of western Europe, including Scandinavia; Blomkvist, The Discovery of the Baltic, is a theoretically interesting and well argued example of a similar approach applied to the southern Scandinavian and the Baltic areas. Medieval Christianity in the North: New Studies, ed. by Kirsi Salonen, Kurt Villads Jensen, and Torstein Jørgensen, AS 1 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013) pp. 1–6 BREPOLS PUBLISHERS 10.1484/M.AS-EB.1.100808 Introduction 2 with regard to common Christian (or European) culture? Furthermore, this book will offer a demonstration of the diversity of Scandinavian cultures in the Middle Ages. Previous historians have tended to write Scandinavian history primarily from a nationalistic viewpoint, considering a given phenomenon not as Scandinavian, but as Swedish, Norwegian, or Danish. If comparing at all, historians tended to look for differences rather than for similarities. As this book attempts to show, this approach is insufficient in many respects. Scandinavian societies very often had much more in common than later historians have wanted to admit. At the same time, however, this book demonstrates that there was a great diversity in the three medieval kingdoms with regard to certain phenomena. To address this problem, all writers have compared their findings with similar results from the other Scandinavian countries, as well as including international comparisons, in order to discuss whether the trends identified were international, national, or local, and why they were adopted or rejected. It is not only general European historiography that has contributed to the image of wild and harsh Scandinavian pagans; local historiography has also been guilty of the same tendency, as Scandinavian historians have been very careful to separate Scandinavian societies from the rest of Europe in order to create a ‘special Scandinavian’ past. This was easy when it came to the Viking era; but the same approach has also been used for later periods. Scandinavian historians have often attempted to separate the history of their countries from broader European historical developments by explaining certain phenomena — such as the Crusades or urbanization — in terms other than those used by their European colleagues when defining these phenomena in a ‘European’ context. Recently, however, perspectives and approaches in historical research in Scandinavia have changed very much: historians now tend to concentrate on finding similarities between European and Scandinavian cultures instead of trying to keep the two separate. This new trend has provoked numerous reinterpretations of Scandinavian history and led scholars to emphasize in particular the active contributions made by Scandinavians in creating a common European culture.3 3 Bysted and others, Jerusalem in the North, and Møller Jensen, Denmark and the Crusades, have argued that wars in the Baltic in the High Middle Ages were not just a continuation of Viking raids, but proper European Crusades. Archbishop Anders Sunesen and his interest in canon law have long been known, but his presence has often been treated in light of the fact that he had studied abroad and was therefore not a real Scandinavian but international in his interests; this is rejected by Nielsen, ‘The Missionary Man’, and elsewhere. Scandinavian provincial laws have been considered very Nordic or Germanic, but their close connection to other contemporary European laws have been stressed recently, e.g. in Andersen, Lærd ret og verdslig lovgivning. Introduction 3 This is the historiographical background to some of the research questions investigated by the project. Since the team members represent different disciplines and are experts in various time periods and geographical areas, the book deals with a wide range of territorial, chronological, and methodological focuses. It considers not only Scandinavia but also beyond, for instance the Baltic territories, which were closely connected to Scandinavia. The comparative method applied in this collection includes references to general European Christian culture. Some authors discuss traditional research themes, such as the Crusades and Christian conversion, while others present totally new fields of research, such as the archival study of the Apostolic Penitentiary, which was made accessible for research only in the last decades of the twentieth century.4 This publication does not attempt to offer a panoptic study of the Scandinavian Middle Ages and its religious culture. This would simply have been too large a task to be dealt with in a single book: the time period in question is very long, covering some one thousand years from the early pagan times up to the era of Reformation; the relevant geographical area, moreover, is very large and heterogeneous, covering not only the present-day Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden) but also areas influenced by them such as the Baltic countries or northern parts of Germany or Poland. In addition, the countries show significant variations in their specific historical development: the emergence of Christianity, for instance, happened in the tenth century in Denmark but as late as the twelfth century in Finland. The aim of this book is therefore not to cover everything but, more modestly, to produce interesting research themes and new approaches in Scandinavian history, and thereby, hopefully, to inspire future research. The book consists of ten articles and some concluding remarks by Patrick Geary, who has followed the NCMS project from the beginning as a member of its external advisory board. The book is divided into two parts, the first of which deals with conversion and its consequences in a broad perspective, while the second is devoted to the consolidation of Christianity and ecclesiastical structures in Scandinavia. The first part begins with an article by Else Mundal which discusses — in regard to the processes of Christianization in the territory of Norway, Iceland, and the western islands — the survival within the new Christian culture of certain mythical and semi-mythical figures from Old Norse heathendom. Stefan Brink then addresses two problematic aspects of 4 Synder og pavemakt, ed. by Jørgensen and Saletnich; Salonen, The Penitentiary as Well of Grace; Auctoritate Papae, ed. by Risberg. 4 Introduction the early church in Scandinavia: the intermediate phase between a first phase of Christianization and the later parish formation, and the question of where the incentive for parish formation came from. A still unsolved problem is why the word which came to be used for a ‘parish’ — more or less simultaneously across all of Scandinavia (barring Iceland) — was sokn, an old legal word literally meaning ‘seeking’ or ‘pursuit’. The joint article by Sæbjørg Walaker Nordeide and Jennifer R. McDonald examines the extent to which canonical conventions, specifically the church’s regulations on food, permeated medieval Norwegian society. By highlighting people’s relationship with certain animals and meats in Norway before and after Christianization through norms (law) and practice (archaeological evidence), the essay examines if and how this relationship changed after the introduction of Christianity with its legal code and conventions. The contribution of Lars Bisgaard then examines the religious roles of wine and beer in medieval Scandinavia, again considering what changes occurred with the coming of Christianity. He concentrates his analysis on sources from various guilds, shedding light upon feasting and drinking rituals which had the character of a lay sacrament, involving beer and wine, and the particular significance of drinking horns. Kurt Villads Jensen argues in his contribution that despite the geographical distance, the North played an important role in the Christian fight against evil and was a prime area for producing both martyrs and war-horses. He further argues that Christianity adapted to local circumstances and that the Nordic pagans, likewise, may perhaps have adopted elements of Christianity. Taking the work of the late American anthropologist Clifford Geertz as a theoretical basis, the article by Torben Kjersgaard Nielsen subsequently discusses the Christianization process of the Baltics in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries through an analysis of the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle and the Chronicle of Henry of Livonia. Claes Gejrot opens the second part of the book with his article on St Birgitta of Sweden, using the documentary source material from the 1370s to uncover the problems of the young but growing Birgittine movement in its initial phase, as well as the preparations behind the attempted canonization process of St Birgitta. Kirsi Salonen then examines the marriage graces (absolutions and dispensations) granted by the Holy See to Scandinavian supplicants in the late Middle Ages. In addition to a statistical analysis related to the supplicants, their background, and their needs, this essay sets the results in the context of the regulations within medieval Scandinavian laws, and tries to identify a specific ‘Scandinavian’ marriage pattern that is unique compared with those elsewhere in Europe. Introduction 5 Torstein Jørgensen focuses in his article on the issue of clerical violence, both in Norwegian civil law and canon law. The problem is addressed through two case studies, one handled by secular legislation and the other by canon law. The author discusses the similarities and the differences of the treatment of these cases within the civil and ecclesiastical jurisdictional systems. Bertil Nilsson then analyses a case in which a rector and canon was punished by the bishop’s judgement for his way of life. The rector paid the fines but at the same time appealed to the pope for justice, prompting further legal dispute and the resummoning of witnesses against him. This essay analyses the minutes from these interrogations, which offer information on the sexual mentality of late medieval Sweden. The book closes with the remarks of Patrick Geary, in which he summarizes some of the results of the book and puts them into a broader perspective. * * * As said, geographical diffusion is one of the issues in this publication. In principle all authors have addressed their subjects from a comparative perspective, but the level and means of comparison vary from one article to the next. Some of the contributions more closely examine one phenomenon or case from one or two defined areas and compare the results to Scandinavian and/or European trends, as in the contributions of Gejrot, Jørgensen, Mundal, Nilsson, and Nordeide and McDonald. A more holistic picture of all Scandinavian countries is compared to wider European Christian contexts in the contributions of Bisgaard, Brink, Jensen, and Salonen, while Nielsen’s article studies the kinds of Scandinavian influences which could be found elsewhere. Interdisciplinary cooperation has been an important part of the activity of the Religion team and this is hopefully reflected in the content of the contributions. All articles deal with at least one discipline, but some draw on more than one scholarly field. An archaeological approach is present in the article by Nordeide and McDonald, and the contributions of Gejrot and Mundal use linguistic and literary approaches, while Brink’s chapter employs all three. Legal, theological, and more popular religious aspects are addressed in the papers by Jørgensen, Nordeide and McDonald, Nilsson, and Salonen. A historical approach is the most common and has been used by Bisgaard, Gejrot, Jensen, Jørgensen, Nielsen, Nilsson, and Salonen. Other disciplines could certainly have been included to a fuller extent, for example the history of art, architecture, theology; these could have been used to present some of the many other source groups from Scandinavia not included in this collection, such as the frescoes in thousands of churches, the huge collections of sermons — well 6 Introduction studied in Sweden but totally untouched in Denmark — or the medieval cathedrals, churches, and monasteries still standing all over Scandinavia. But what has been included in this book is hopefully enough to give an impression of the wealth of material remaining from the Scandinavian Middle Ages and to demonstrate how, by applying an interdisciplinary and comparative approach, we may gain new insights into old problems. Works Cited Secondary Studies Andersen, Per, Lærd ret og verdslig lovgivning: retlig kommunikation og udvikling i middel­ alderens Danmark (København: Jurist- og Økonomforbundets, 2006) Bartlett, Robert, The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization, and Cultural Change, 950–1350 (London: Lane, 1993) Blomkvist, Niels, The Discovery of the Baltic: The Reception of a Catholic World-System in the European North (ad 1075–1225), The Northern World, 15 (Leiden: Brill, 2005) Jensen, Janus Møller, Denmark and the Crusades, 1400–1650, The Northern World, 30 (Leiden: Brill, 2007) Jørgensen, Torstein, and Gastone Saletnich, eds, Synder og pavemakt: botsbrev fra Den Norske Kirkeprovins og Suderøyene til Pavestolen, 1438–1531, Diplomatarium poeni­ tentiariae Norvegicum (Stavanger: Misjonshøgskolen, 2004) Lind, John, and others, Danske korstog: krig og mission i Østersøen (København: Høst, 2004) Nielsen, Torben K., ‘The Missionary Man: Archbishop Anders Sunesen and the Baltic Crus­ade, 1206–21’, in Crusade and Conversion on the Baltic Frontier, 1150–1500, ed. by Alan V. Murray (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2001), pp. 95–117 Risberg, Sara, ed., Auctoritate Papae: The Church Province of Uppsala and the Apostolic Penitentiary, 1410–1526, Diplomatarium Suecanum, Appendix: Acta Pontificum Suecica, 2 (Stockholm: Riksarkivet, 2008) Salonen, Kirsi, The Penitentiary as a Well of Grace in the Late Middle Ages: The Example of the Province of Uppsala, 1448–1527, Annales Academiae Scientiarum Fennicae: Humaniora, 313 (Saarijärvi: Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 2001) Remnants of Old Norse Heathendom in Popular Religion in Christian Times Else Mundal T his article discusses certain mythical and semi-mythical figures from Old Norse heathendom — the landvættir, ‘the spirits of the land’; so-called lower deities, among them female fylg jur and norns; and fylg jur in the shape of animals — which continued to survive at the periphery of Christian culture for a long time after Christianization, albeit in somewhat altered form. The remnants of Old Norse heathendom are discussed against the background of the Christianization process. Although that process shares certain common traits in all cultures, the precise nature of its development must have varied from one culture to another; and the form of Christianity developed must have been affected by both the old culture and the culture from which the process of Christianization was launched. Old Norse culture, the focus of this article, was found in the western Nordic area: Norway, Iceland, and the other islands in the west that were populated predominantly from Norway. The majority of the sources are Icelandic, and in some cases it is difficult to say with certainty whether the whole west Nordic area shared the remnants of heathen beliefs discussed in this article. The close contact experienced within this region, and the common origins of the people, suggest that religious concepts did not differ greatly in the last phase of heathenism but that differences in heathen remnants developed over time. Else Mundal (else.mundal@cms.uib.no) is Professor Emerita at Universitetet i Bergen. Medieval Christianity in the North: New Studies, ed. by Kirsi Salonen, Kurt Villads Jensen, and Torstein Jørgensen, AS 1 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013) pp. 7–22 BREPOLS PUBLISHERS 10.1484/M.AS-EB.1.100809 8 Else Mundal Introduction Christianization did of course form a break in historical development, but it is not easy to stamp out old beliefs in, and concepts of, supernatural beings. Within all areas of Europe some remnants of what existed prior to Christianization probably continued to live on — at least for some time — after conversion. If these remnants were integrated into Christian beliefs, they would have given Christianity, within a particular area, a local tint. That this local colour was strong enough and long-lasting enough to have a permanent influence on Christian concepts was obviously more likely in the early phases of Christendom, when Christianity was a small religion, its dogmas less solidified and more open to influences than later in the Middle Ages. The influence of Greek philosophy on Christianity in the primitive church is a good example of permanent influence on Christian concepts from a preceding culture. In the Christianity of a newly converted area, such as the Old Norse area in the Middle Ages, it may be possible to find traits from all the cultures through which Christianity had passed on its way to this region. However, besides traits from the cultures in which early Christendom was formed (late Judaism and Greek culture), it was probably the traits from the culture or cultures from which Christianity was directly introduced that were most visible. Such traits were not necessarily connected to Christian beliefs directly — though a local tinting of beliefs and ideas in one culture could of course be transferred to another. But the introduction of local saints, vernacular words for Christian concepts, and ecclesiastical organization are perhaps more typical of ‘loans’ from the region from which Christianity was introduced to newly converted regions. By the time Christianity was introduced to the Nordic periphery of Europe, it had already grown to become a strong and widespread religion. However, in the periphery of the Christian world, the church met many of the same challenges in the Middle Ages as it had met in the first centuries in the Mediterranean area, such as how to deal with old heathen beliefs and figures. The present article will discuss how the early Christian Old Norse culture dealt with some of its heathen remnants. One important problem faced by Christian missionaries among the Old Norse must have been: How can we make Christianity appeal to the heathen North? In the period before the Nordic countries converted to Christianity, the new religion was far from unknown in the North. We do not know exactly how early the Nordic culture came into contact with Christianity, but we must assume that there had been some contacts for a long time, and that they had been increasing in the period leading up to Christianization. It is obvious that Old Norse Heathendom in Popular Religion in Christian Times 9 the Old Norse religion was influenced by Christianity in the period before Christianization, and many scholars of different periods have explained certain elements in Old Norse religion by the influence of Christianity.1 Old Norse heathendom was an open religion which easily could include new elements, and it would probably have shown great variation over both space and time. Christianity, which was a dogmatic religion, was more stable, but the missionaries probably tried to present Christianity in a way which they thought would appeal to the local heathens. That in itself would perhaps not have changed Christianity, but such a missionary strategy, called forth by the wish to communicate better with a local heathen population, would have given Christian preaching within a certain area a local hue, stressing the Christian elements which were best suited to persuade and convert its inhabitants. One clear example of this in Old Norse culture is that the strength of the Christian God, his omnipotence, is emphasized in early skaldic poetry from the Christianization period onward, and Christ is pictured as a victorious Viking king. This must in all likelihood reflect the preaching of the period. The Christian God’s omnipotence was presumably a strong argument in favour of the new religion. To the heathen Vikings it must have seemed logical that the warriors who worshipped the strongest god would be victorious.2 What the missionaries preached and what the heathens understood were not necessarily the same. Those who had been brought up in the heathen culture would have interpreted Christianity with the help of concepts and a world1 Sophus Bugge, a leading scholar in the last decades of the nineteenth century, was inclined to see influence from Christianity in many Old Norse myths. He believed, for instance, that the myth of the death of Baldr, and that of Óðinn hanging on the tree, were modelled on the death of Christ. Further, he argued that both these myths, as many others, were formed in the British Isles where Vikings settled down and came in contact with Christianity. Bugge, Studier over de nordiske Gude- og Heltesagns Oprindelse; see also Moe, ‘Sophus Bugge og mytegranskingane hans’. Bugge’s interpretation takes Óðinn’s sacrifice out of its context in Old Norse mythology. Óðinn’s aim was to obtain wisdom, not salvation, and Óðinn strives for wisdom in many myths. His sacrifice of himself to himself must be seen in connection with other sacrifices in Old Norse mythology. Óðinn also sacrificed his eye to obtain wisdom, and other gods made their sacrifices too: Tyr sacrificed his right arm, and Heimdallr his sense of hearing. Walter Baetke is a good representative of the scholars who, in the period when historical source criticism was at its height, saw most parallels between Christianity and Old Norse myths and rituals as reconstructions of Old Norse heathendom made by Christian authors. See Baetke, Christliches Lehngut in der Sagareligion. 2 A discussion of such skaldic stanzas is found in Marold, ‘Der Gottesbild der Christlichen Skaldik’; and in Mundal, ‘Kristusframstillinga i den tidlege norrøne diktinga’. Else Mundal 10 view inherited from their old religion.3 God the Father and Christ could easily be accepted as new gods and included in the Nordic pantheon, but in a heathen context they would have been seen in a heathen light. One might think that Christ, who had been killed by his enemies in a humiliating way, would not have appealed to people in the Old Norse culture. There existed Old Norse myths, however, which could function as a basis for interpreting Christ’s death in their own fashion. For example the god Baldr was killed and went to hell.4 There is also another Old Norse story that Óðinn sacrificed himself to himself by hanging for nine nights from the World Tree in order to obtain wisdom.5 The constituent elements of these myths were probably not unique to the Old Norse culture.6 The death of Christ on the cross as a symbol of salvation for mankind may have been initially difficult to conceive by a culture where the concepts of sin and salvation did not exist. It was probably easier and more acceptable in the Old Norse culture to interpret Christ’s crucifixion as a mysterious death which, like that of Óðinn, made him wise and powerful. The picture of Christ as a king is of course rooted in the Bible, and in Old Norse culture the image of Christ as king is very dominant. There may, however, also have existed Old Norse myths which explain why the son of God in this particular culture was portrayed as a king. According to Old Norse mythology and ideology of kingship, the first king, the prototype king, was the son of a god and a giantess.7 The son of God and a human woman, Mary, would there3 See Mundal, ‘Il cristianismo considerato dal punto di vista pagano dei vichinghi’. The fullest form of the Baldr myth is found in Snorri Sturluson, Edda, Gylfaginning, ed. by Faulkes, chap. 49. There are partial retellings of and references to the myth in several Eddic poems which Snorri knew: Baldrs draumar, Vǫluspá, Vafþrúðnismál, and Lokasenna. The Eddic poems are in Norrœn Fornkvæði, ed. by Bugge. He further built on a skaldic poem, Húsdrápa by Ulfr Uggason, composed in the late tenth century: Den norsk-islandske skjaldedigtning, ed. by Finnur Jónsson, B I: pp. 128–30. It can be seen from Snorri’s Gylfaginning that he also knew poems that are unknown to us. 5 The source for the myth of Óðinn hanging on the tree is the Eddic poem Hávamál, in Norrœn Fornkvæði, ed. by Bugge. In Hávamál, stanza 138, these words are put in the mouth of Óðinn: ‘I know that I hang on a windy tree for nine nights, wounded with a spear, given to Óðinn, myself to myself […]’. There are also many references to this myth in the skaldic language. 6 Richard North has argued that in the Old English poem The Dream of the Rood, ‘the image of Christ’s death was constructed […] with reference to an Anglian myth about the world tree’: North, Heathen Gods in Old English Literature, p. 273. In an Old English charm, Woden’s Nine Herbs Charm, preserved in BL, MS Harley 585, probably from the tenth or eleventh century, Óðinn and Christ seem to be mixed. In this case the mixing could be due to Scandinavian influence. 7 See Steinsland, Det hellige bryllup og norrøn kongeideologi. 4 Old Norse Heathendom in Popular Religion in Christian Times 11 fore conform very well to an Old Norse mythic pattern. Even the virgin birth in the Christian religion may have been understood in the light of an Old Norse heathen myth. The Old Norse god Heimdallr was born by nine giantesses, all sisters, and whether there was a father or not is very unclear from the sources. It is the nine mothers who are focused upon.8 This birth by nine mothers was probably even more mysterious than the virgin birth by one single mother and may have prepared the ground for the acceptance of the Christian virgin birth. Few scholars still regard the Christian influence on Old Norse myths to be of the same strong impact that Bugge and Baetke suggested. But there is no reason to doubt that Old Norse myths in the last phase of heathenism were influenced by Christianity, and later in the Middle Ages learned authors, such as Snorri, may have stressed the similarities between heathen myths and Christianity in accordance with the church’s view of pre-Christian religions — namely, that they could be seen as imperfect glimpses of the truth created in the minds of people who had lost contact with God. 9 This means that the form of Old Norse myths in the pre-Christian culture — which probably existed in different local variants — cannot be established with certainty because of a lack of written sources from the heathen period. We have only glimpses of fragmented myths in a few skaldic poems from the period before 900, like Bragi’s Ragnarsdrápa from the first half or middle of the ninth century, and some Eddic poems that contain Old Norse myths may have already existed in the same period. The dating of Eddic poems is, however, very complicated, and these poems were, moreover, much more open to changes in the oral tradition than skaldic poetry. Even though we do not know the form of the myths in any detail, the concepts and world-view expressed in Old Norse myths represented the Old Norse mentality which received and interpreted the new religion when the two worlds met. It is not very likely that Old Norse heathen interpretations of Christianity were long-lived. They would probably have disappeared with growing knowledge of Christianity and would have been replaced by ‘correct’ Christian concepts. Remnants of Old Norse heathendom, on the other hand, for which Christianity offered no replacement, could live on for centuries. 8 Heimdallr’s nine giant mothers are mentioned in Snorri Sturluson, Edda, Gylfaginning, ed. by Faulkes, chap. 27. His main source, from which he quotes two lines, seems to be an Eddic poem, otherwise lost, called Heimdallargaldr. 9 See Kurt Villads Jensen’s article in this book. 12 Else Mundal Remnants of Heathendom in Old Norse Christian Culture When a people changed religion there were always some mythical figures and concepts central to the old religion which did not have their equivalents — or, at least, not good equivalents — in the new religion, and might therefore leave an empty space, a need, in people’s religious life. In such cases it is very likely that the old concepts continued to live on in some form or another, at least for a period of time. Regarding the remnants of Old Norse heathendom within Christian culture, the longer these remnants continued to exist, the better our sources. Since there are no written sources from the period of Christianization — except for a few runic inscriptions — it is difficult to follow the transition from heathen to Christian society in any detail. Skaldic stanzas from the Christianization period and the Christian period before the advent of written literature may, however, give some information about heathen remnants and the mixing of heathen and Christian beliefs in the newly Christianized Old Norse society. The oldest Old Norse written source for Christianization in Iceland is Íslendingabók by Ari inn fróði, written in the 1120s or around 1130. The sources used in this article — Eddic and skaldic poetry, Snorri’s Edda, saga literature, laws, and sermons — originate, as written texts, from a period when society had been Christian for two hundred years or more. Saga literature, laws, and other texts produced in the Christian society are, of course, very good sources for the concepts and beliefs which existed in this society. In the following I will discuss a few supernatural beings which were closely connected with Old Norse heathendom and heathen concepts but which continued to live on in popular belief for a long time after Christianization. The concepts of these beings were, however, influenced by the new religion in different ways. I will suggest some explanations as to why certain heathen beings continued to exist in people’s minds in Christian times and try to explain the changes these beings underwent in light of the different ways in which the Christian culture could react against the remnants of heathendom. The beings I will discuss are: 1) landvættir, the spirits of the land; 2) so-called lower deities, especially female figures like nornir (norns), fylg jur (guar­dian spirits), and valkyrjur (valkyries) (belief in fate was closely connected with the norns); and 3) fylg jur in the shape of animals which were external souls/alter egos. Old Norse Heathendom in Popular Religion in Christian Times 13 It was not the policy of the church to deny that heathen gods or heathen powers existed even though they did not, of course, recognize them as gods. Heathen gods were normally demonized, but there were other ways to react, especially against heathen figures or spirits, which were probably regarded as less dangerous to Christianity than the heathen gods. Figures belonging to a heathen mythology could be made harmless — or less harmful — by being transferred to the sphere of superstition. They could be altered and made acceptable to the Christian religion, or they could have an existence at the periphery of Christian culture if the potential conflict between the Christian religion and the remnants of Old Norse heathendom did not become an open controversy. The landvættir, the Spirits of the Land The landvættir, ‘spirits of the land’, were probably important figures in the Old Norse religion. They seem to overlap, more or less, with the group called álfar, ‘elves’, in Old Norse. They secured fertility and ‘luck’, which in this context means a person’s ability to succeed, and they were objects of worship. Christianization did not root out the cult of the landvættir. In the Norwegian laws from the Middle Ages, this worship was strongly prohibited, which probably indicates its continued practice. As late as in the Christian section in the younger Gulathing Law (from the 1260s), landvættir are mentioned (Chapter 3) among things in which people should not believe — it is forbidden ‘at trua a landvættir at se j lvndum [londum]10 æda haugum æda forsom’ (to believe in spirits of the land; that they are in groves, mounds, and waterfalls).11 The cult of the landvættir in Christian times is also documented in a sermon preserved in Hauksbók (early fourteenth century, though the sermon may be older). This sermon is about superstition, and says that some women are so stupid and blind that they take their food and bring it out to cromlechs or caves, bless it and sacrifice it to the spirits of the land and eat it thereafter so that the spirits of the land shall be friendly towards them and so that they shall have more luck with their farming than before.12 10 Some manuscripts of the law have the reading londum (land). Norges Gamle Love, ed. by Keyser and Munch, ii (1848), 308. 12 ‘taka mat sínn oc fœra a rœysar vt eða vndir hella. oc signa land vettum oc eta siðan. til þess at land vettír skili þeím þa hollar vera oc til þess at þer skili þa eiga betra bu en aðr’; Hauksbók, ed. by Eiríkur Jónsson and Finnur Jónsson, p. 167. 11 14 Else Mundal One reason why people continued to believe in the landvættir, and even continued to sacrifice food to them, may be that Christianity had nothing which easily could replace the spirits of the land, and the function they served in the old religion was too important to be ignored. We know that heathen worship in many cases was transferred onto saints, but this does not seem to have happened with the cult of the landvættir. Perhaps the saints who were introduced in the period of Christianization — those central to the whole church, together with local saints from the regions from which Christianity was introduced to the Old Norse world — lacked the connection to the local soil and local past enjoyed by the landvættir. This changed later — most regions eventually had their own local saints — but by that time the landvættir had survived the critical period of Christianization. Whether the landvættir were demonized or denounced as mere superstition may be a matter of discussion. According to the laws, the belief in landvættir is defined as heiðinn átrunaðr (heathendom); in the sermon, the sacrifice to the spirits of the land is characterized as stupidity. Probably the belief in the land­ vættir — and the álfar — was in the grey area of what the church bothered to fight. As shown in the sermon quoted above, this cult was practised by women — and probably mostly by women. Perhaps the men of the church saw it as mere harmless female foolishness, an ‘old wives’ tale’, but as we can see from the laws and the sermon, the church did react against the belief in this remnant of heathendom. Lower Deities Belief in some of the so-called lower deities, such as fylg jur and nornir, also continued to exist after Christianization. In the Icelandic saga literature — mostly from the thirteenth century — we meet the female fylg ja in many texts. This figure was the guardian spirit of the family, especially of the head of the family: she secured luck and prosperity. If she abandoned a person, it was a very bad omen.13 As I see it, the female fylg ja had her origin in the cult of foremothers, in which case this figure would have been problematic in Christian times.14 The cult of forefathers and foremothers may have been an important part of Old Norse heathen cult. According to the older Gulathing Law, Chapter 29, 13 Analyses of motifs in which the female fylg jur occur are found in Mundal, Fylg jemotiva i norrøn litteratur, pp. 63–128. 14 See Mundal, Fylg jemotiva i norrøn litteratur, pp. 101–06. Old Norse Heathendom in Popular Religion in Christian Times 15 it was forbidden to blóta (‘sacrifice to’) mounds, which probably means grave mounds, and the cult which took place there must have been that of forefathers and foremothers.15 Worship of this type was forbidden together with the worship of the gods, and if the connection between the female fylg ja and ancestors was still clear at the time of Christianization, these figures would have been closely connected with the forbidden heathendom. However, here we can observe a solution other than wholesale rejection or demonization; nor are the fylg jur recast as harmless superstitions. In a few literary motifs from the sagas we can observe that the old female fylg ja is separated into two figures, one white and Christian, one black and heathen. A very good example of this splitting of one being into two is found in Þáttr Þiðranda ok Þórhalls.16 This short story tells of a young boy, Þiðrandi, who was seriously wounded one night when he went out against his father’s will. He was found the next morning, and before he died he explained what had happened. He had gone out in the middle of the night because he thought that he heard someone knocking at the door. Outside he saw nine women riding from the north towards him, all dressed in black. They had swords in their hands and attacked him. While defending himself against the black women, he heard nine women come riding from the south. They were all dressed in white and riding on white horses. A wise man interpreted this strange incident. His interpretation was that the black women were the old heathen fylg jur of the family, and they wanted to make sure that Þiðrandi would come to them before it was too late. People would soon convert to a new and better faith. The white women were the new Christian fylg jur of the family, but since Þiðrandi was not yet a Christian, they were not able to save him. The same splitting of the female fylg ja, here called draumkona, ‘dream woman’, is found in Gísla saga Súrssonar, a saga of Icelanders probably written around the middle of the thirteenth century. Gísli, who is the hero of the saga, lives in the last phase of heathendom. He is acquainted with Christianity, he does not sacrifice to the heathen gods any more, but he has not become a Christian. He can be characterized as a ‘good heathen’. Gísli has two draum­ konur who appear in his dreams. The good draumkona is clearly connected with Christianity and advises Gísli to live in accordance with what can be identified as Christian morality; she promises Gísli that he will come to her when he dies. 15 Norges Gamle Love, ed. by Keyser and Munch, i, 18. Flateyjarbók, ed. by Guðbrandur Vigfússon and Unger, i, 420. Flateyjarbók was written in the 1380s, but the story may be older. 16 16 Else Mundal The evil draumkona counteracts any decision made by the good and Christian draumkona about Gísli’s life. The two draumkonur, who are the old female fyl­ g ja split in two, can be read as the Christian and heathen powers struggling over Gísli, the good heathen, at the threshold of Christian times.17 Concerning the norns, we can observe a splitting of another kind. In Iceland the word norna gradually acquired the same meaning as the English ‘witch’. This important female figure in Old Norse mythology became demonized more or less in the same way as the Old Norse gods. One good example of this is found in a skaldic stanza, lausavísa 10, by the Icelandic skald Hallfrøðr vandráðaskáld, one of the skalds of King Óláfr Tryggvason (995–1000). In this stanza Hallfrøðr says that: ‘verðum flest at forðask | fornhaldin skǫp norna’ (we have to keep away from all decisions made by the norns in which they believed earlier).18 If this stanza is genuine, that is, by Hallfrøðr, it was composed a few years before the year 1000; if it is not, it may have been composed any time between Hallfrøðr’s time and the writing of his saga early in the thirteenth century. This stanza describes the attitude towards old heathen figures, both gods and norns, at the court of King Óláfr Tryggvason, and if the stanza is genuine it should be representative of attitudes towards the norns in circles around the Norwegian king. However, in Norway belief in and attitudes towards the norns seem not to have changed, at least not as drastically as in Iceland. In a runic inscription found in Borgund stave church (probably from around 1200) the norns are mentioned as the creators of fate. The man who carved the inscription names himself Þórir, and he says in the runic inscription: ‘Bæði gerðu nornir vel ok illa; mikla mœði skǫpuðu þær mér’ (the norns did both good and bad things, for me they made heavy burdens | a cruel fate). 19 In the Norwegian valley of Setesdal, the porridge which was served to women after childbirth was called nornegraut, ‘the norns’ porridge’, as late as when folklore from the valley was collected in the nineteenth century. It is tempting to see the ‘norns’ porridge’ in the light of a passage in Snorri’s Edda. In Gylfaginning Snorri says that norns come to every newborn child to create fate.20 17 For a fuller analysis of the female fylg ja motif in this saga, see Mundal, ‘Sagalitteraturen og soga im Gisle Sursson’. 18 Den norsk-islandske skjaldedigtning, ed. by Finnur Jónsson, i, 159. 19 Norges Innskrifter med de yngre Runer, ed. by Olsen, iv (1957), 149. 20 Snorri Sturluson, Edda, Gylfaginning, ed. by Faulkes, chap. 15. Old Norse Heathendom in Popular Religion in Christian Times 17 The idea that fate was created by the norns is of course not in agreement with the Christian faith. However, in Norway — and probably also elsewhere — the belief in the fate-making norns seems to have persisted after Christianization. The potential conflict between this ‘heathen’ idea and the Christian faith did not develop into an open controversy. Perhaps conflict was avoided by not stressing who the creators of fate were, the norns or the Christian God. It is also possible that the concept of the norns dictating fate — that is, that everything was decided in advance — found a point of connection in the belief in predestination in Christianity, even though predestination primarily concerned the next life, and fate this life. A parallel to the situation in the North can be found in the areas in which the goddess Fortuna had been worshipped in pre-Christian times. The concept of fortune lived on after Christianization, but must have gradually lost its connection with the personified goddess.21 As Tuomas M. S. Lehtonen has shown, in the twelfth-century European renaissance there was a revival in the belief in Fortuna, not as a classical goddess but as a principle explaining life and history. The concept of fortune was not unproblematic in relation to Christianity.22 The Old Norse concept of fate or decisions made by the norns has much in common with the concept of fortune. But in the North, not only the concept of fate but also that of the personified female figure, the norn, continued to exist. In Iceland this figure was more or less demonized as a witch, whilst in Norway the norn lived on as a more neutral figure. When so-called lower female deities survived in Christian times, the explanation could partly be, in this case too, that Christianity had little with which to fill the gap. The Virgin Mary and female saints might partly fit, but Christianity was a much more male-oriented religion than Old Norse heathendom, both in the sense that there was only one male god, and because women could not be in charge of acts of worship. In addition, the lower deities were probably seen as a less serious threat to Christianity than the gods. However, that the fylg jur were split into two, one good and Christian and the other bad and heathen, and that the norns became witches in Iceland, show that these beings were problematic and not easy to integrate with the Christian culture. The requirement for integration — or acceptance — seems to have been that the heathen figures changed so that they could be more or less identified with a 21 When Fortuna returned as a personified goddess during the Renaissance, this apparent paganism was purely literary. 22 Lehtonen, Fortuna, Money, and the Sublunar World, pp. 73–122. Else Mundal 18 Christian figure. The white and good fylg jur have clearly inherited traits from the Christian angels. This could happen since they had something in common. They were both guardian spirits, and they were both connected with the afterlife. In Old Norse sources we meet the idea that people will come to their dead ancestors — a place where their fylg jur also exist.23 Even the valkyrjur seem in one text to merge with the angels. In a skaldic stanza (lausavísa 22), the skald Bjǫrn hítdœlakappi describes a woman who has visited him in a dream.24 This woman invites him home, and she is called the woman of hilmir dagbœjar, which is a kenning for ‘the King of Heaven’. This woman, who comes from the Christian King of Heaven, is described in a long and complicated kenning, but the interesting thing is that she is hjalmfaldin, which means that she wears a helmet. This is the picture of a valkyrja, but she invites the Christian skald home to the King of Heaven. The valkyrjur who chose the men who were to die and brought them to Óðinn’s Valhǫll, and the angels who brought the souls to heaven, had little in common, but obviously enough to make the two beings merge in at least some early Christian minds. If the stanza in question is genuine, it was composed early in the eleventh century, but if it was by the author of the saga about Bjǫrn hítdœlakappi, which perhaps is more likely, then it was composed early in the thirteenth century. The merging of angels and Old Norse female deities is interesting because angels were male figures. Female angels are — as far as I know — a late phenomenon, and have not been seen in connection with the so-called lower female deities in pre-Christian European religions.25 One could, however, wonder whether the lower female deities, who continued to exist both in popular religion (in the North) and in sculpture and literature (in the South), had something to do with the angels, probably from the seventeenth century onwards, being represented as female in different forms of art. The problem with this explanation is the long period of time between heathenism and the appearance of female Christian angels. We do not, however, know much of what existed in popular religion in the meantime, and it must be admitted that the gender reversal of the angels is not a well- explored topic. 23 See Mundal, Fylg jemotiva i norrøn litteratur, pp. 101–05. Den norsk-islandske skjaldedigtning, ed. by Finnur Jónsson, i, 282. 25 In pre-Christian European religions there existed a wide variety of winged female beings. See Egeler, ‘Death, Wings, and Divine Devouring’. 24 Old Norse Heathendom in Popular Religion in Christian Times 19 The fylgjur in the Shape of Animals The last figures which I want to mention are the fylg jur in the shape of animals. These are external souls, a person’s alter ego, and the shape of the animal reflects the character of the person. A strong man may have a bull or a bear as his animal fylg ja, a cunning man a fox, and so on.26 The belief in the existence of such fylg jur is found in a large number of Old Norse texts. We often meet an animal, walking in front of his person, invisible to all except second-sighted people and dreamers. If a man sees his own animal fylg ja, it means that he is soon going to die. What happens to the fylg ja will happen to its owner in a short time. The animal fylg ja motifs are therefore used to foretell the future, and their popularity must be seen in connection with their important function in saga composition. The concept must have been strong and took a long time to die out. These souls in the shape of an animal probably did not represent a great threat to Christianity, and, as far as I know, there is no evidence that the church tried to root out the belief in them. On the other hand, the Christian concept of the eternal soul was not consistent with souls in the shape of an animal. That may explain why the belief in fylg jur changed over time. In Norway the whole figure of the animal faded away, leaving the vardøger, a being which in some strange way was still identical with the person but no longer had the shape of an animal, or any shape at all. In Iceland, fylg jur may have retained their shape of an animal but lost their close connection with a person’s external soul. The identification between a person’s soul and an animal seems to have become problematic, but only after some hundred years.27 Conclusions As suggested above, stressing the strength of the new religion, and presenting Christ as a victorious Viking king (in all likelihood, the missionaries’ strongest argument when trying to convince the people of the heathen North that 26 An overview of the animal fylg ja motifs, demonstrating the variety of animals that occur as fylg jur, is found in Mundal, Fylg jemotiva i norrøn litteratur, pp. 26–37. 27 For a fuller analysis of the animal fylg ja motif see Mundal, Fylg jemotiva i norrøn littera­ tur, pp. 26–55 and 129–42. The subject has lately been addressed by Eldar Heide who expresses a slightly different view concerning the animal fylg ja’s character as man’s alter ego. Heide, ‘Gand, seid og åndevind’, pp. 146–55. 20 Else Mundal Christianity was a better and more useful religion than their old one), would have given a local tint to the form of Christendom which was practised in the North. It is probable that the stress placed upon the strong elements within Christianity during the period of Christianization led to a somewhat later introduction and adoption of other, potentially conflicting, Christian ideas — such as the concepts of sin and God’s mercy and the demand on Christians to love their enemies and forgive instead of taking revenge. The interpretation of stories from the Bible in the light of Old Norse myths would probably be corrected once Christianity was firmly established. The Old Norse culture became a written culture rather early, and within a written culture, variants of Biblical motifs — at least those which concern central Christian dogmas — are not likely to survive for long. They may have survived longer in the more oral popular religion. On the other hand, beings belonging to Old Norse heathenism which were demonized, made harmless by being transferred to the sphere of superstition, or partly assimilated with Christian figures (for example, angels) could continue to live on for centuries — but usually in a changed form. Even unchanged, the belief in heathen beings and concepts, for example the norns and fate, could continue within the frame of a Christian culture as long as the potential conflict between Christianity and remnants of the old religion was downplayed. These remnants of Old Norse heathendom did in a way leave their marks on the Christianity practised in the North. The dogmas were unchanged, but the beings that were demonized were unique to the Nordic area. Every Christianized area populated hell with beings that reflected their pre-Christian religion. These would mix and partly merge with the earlier inhabitants of hell. Even though Christianity, unlike Norse heathenism, was a dogmatic religion, the ‘demonic side’ of Christianity was as open as the old heathendom and could easily include all the demonized ‘leftovers’ from the old religion. At the periphery of the Christian culture existed beings and beliefs which had been only partly integrated, and perhaps scarcely tolerated, and this too would have contributed to a sort of a regional Christian culture. The remnants of Old Norse heathenism which continued to exist in the popular religion of the North hardly spread to other areas within the Christian church. However, to the concept of fate or fortune which developed in Christian Europe on the basis of older beliefs, the North contributed its part. Old Norse Heathendom in Popular Religion in Christian Times 21 Works Cited Manuscripts and Archival Documents London, British Library, MS Harley 585 Primary Sources Den norsk-islandske skjaldedigtning, ed. by Finnur Jónsson, 2 vols (København: Villadsen & Christensen, 1912–15) Flateyjarbók: en samling af Norske Konge-saegar, ed. by Guðbrandur Vigfússon and Carl Rikard Unger, 3 vols (Christiania: Malling, 1860–68) Hauksbók, ed. by Eiríkur Jónsson and Finnur Jónsson (København: Det kongelige nordiske oldskrift-selskab, 1892) Norges Gamle Love indtil 1387, ed. by Rudolf Keyser and Peter Andreas Munch, 5 vols (Christiania: Gröndal, 1846–95) Norges Innskrifter med de yngre Runer, ed. by Magnus Olsen, 6 vols (Oslo: Kjelde­ skriftfondet, 1948–90) Norrœn Fornkvæði: Islandsk Samling af Folkelige Oldtidsdigte om Nordens Guder og Heroer almindelig kaldet Sæmundar Edda hins fróða, ed. by Sophus Bugge (Christiana: Malling, 1867) (repr. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1965) Snorri Sturluson, Edda, Gylfaginning, in Edda: Prologue and Gylfaginning, ed. by Anthony Faulkes (London: Viking Society for Northern Research, University College London, 1988), pp. 7–55 Secondary Studies Baetke, Walter, Christliches Lehngut in der Sagareligion, Sitzungsberichte der Sächsischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Leipzig, Philologisch-historische Klasse (Berlin: Akademie, 1951) Bugge, Sophus, Studier over de nordiske Gude- og Heltesagns Oprindelse, 2 vols (Christiania: Cammermeyer, 1881–89) Egeler, Matthias, ‘Death, Wings, and Divine Devouring: Possible Mediterranean Affini­ ties of Irish Battlefield Demons and Norse Valkyries’, Studia Celtica Fennica, 5 (2008), 5–25 Heide, Eldar, ‘Gand, seid og åndevind’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, Universitetet i Bergen, 2006) Lehtonen, Tuomas M. S., Fortuna, Money, and the Sublunar World: Twelfth-Century Ethi­ cal Poetics and the Satirical Poetry of the ‘Carmina Burana’ (Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1995) Marold, Edith, ‘Der Gottesbild der Christlichen Skaldik’, in The Sixth International Saga Conference 28/7–2/8 1985: Workshop Papers (København: Arnamagnæanske Institut, Københavns Universitet, 1985), pp. 717–49 22 Else Mundal Moe, Molkte, ‘Sophus Bugge og mytegranskingane hans’, in Norske folkeskrifter, 6 (Oslo: Norigs ungdomslag og Student-maallaget, 1903), pp. 1–24 Mundal, Else, ‘Il cristianesimo considerato dal punto di vista pagano dei vichinghi: Christianity Seen from the Heathen Point of View of the Vikings’, in Il mondo dei Vichinghi: ambiente, storia, cultura e arte, ed. by Ernesto Bruno Valenziano (Genova: Sagep, 1992), pp. 309–22 —— , Fylg jemotiva i norrøn litteratur (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1974) —— , ‘Kristusframstillinga i den tidlege norrøne diktinga’, in Møtet mellom hedendom og kristendom i Norge, ed. by Hans-Emil Lidén (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1995), pp. 255–68 —— , ‘Sagalitteraturen og soga om Gisle Sursson’, in Soga om Gisle Sursson: lang og kort versjon, ed. by Dagfinn Aasen (Oslo: Samlaget, 1993), pp. 28–30 North, Richard, Heathen Gods in Old English Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge Uni­ versity Press, 1997) Steinsland, Gro, Det hellige bryllup og norrøn kongeideologi: en analyse av hierogami-myten i Skírnismál, Ynglingatal, Háleyg jatal og Hyndluljóð (Oslo: Solum, 1991) Early Ecclesiastical Organization of Scandinavia, Especially Sweden Stefan Brink* T his article addresses two vital, although very elusive and problematic, aspects of the early church in Scandinavia. One is the intermediate phase between initial Christianization (probably to be placed in the tenth and early eleventh centuries) and the later parish formation phase (in the late twelfth and thirteenth centuries). The other concerns the incentive for parish formation: one still unsolved problem, for instance, is why in Scandinavia the word to be used for a ‘parish’ was sokn, an old legal word, which more or less simultaneously became the word for a ‘parish’ used all over Scandinavia (except Iceland). Introduction With the arrival of the Christian church came the introduction of literacy and written administration, which fundamentally changed Scandinavian society. There seems to have been some sort of territorial administration of a basic kind before the church, a ‘hundred’ division (into hundari and hærath), men- * This article is a reworked and expanded version of ‘Pastoral Care before the Parish: Aspects of the Early Ecclesiastical Organization of Scandinavia, Especially Sweden’, in England and the Continent in the Tenth Century: Studies in Honour of William Levison (1876–1947), ed. by David Rollason, Conrad Leyser, and Hannah Williams, Studies in the Early Middle Ages, 37 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2011), pp. 399–410. I would like to thank Guðný Zoëga, Ragnheiður Traustadóttir, and Leif Grundberg for permission to reproduce their illustrations. Stefan Brink is Sixth Century Professor of Scandinavian Studies at the University of Aberdeen. Medieval Christianity in the North: New Studies, ed. by Kirsi Salonen, Kurt Villads Jensen, and Torstein Jørgensen, AS 1 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013) pp. 23–39 BREPOLS PUBLISHERS 10.1484/M.AS-EB.1.100810 Stefan Brink 24 11th century 11th century c. 950 c.1020 c.1050? c.1150 St Clement’s, Oslo c.1000 c.1000 c.1000 c.1050 c. 865? Map 1. Early Christian Burials in Scandinavia. c. 9 85? c. 840? 1112 St Clement’s, Helsingborg c.1025 c.980 c. 990 Map 2. Early Churches in Scandinavia tioned in sources from the eleventh century, but with the church came a comprehensive structure at different levels which remained stable, in principle at least, up to the nineteenth century. Early scholars argued that the ecclesiastical structure reused, and was more or less superimposed upon, an already existing non-Christian territorial structure, based upon small pagan cult districts.1 Subsequent research has rejected this idea. Instead it has been stressed that the church was innovative and creative in this organizational respect. But before discussing the ecclesiastical organization, we must start somewhat earlier, with the Christianization of Scandinavia. The Christianization and the organization of the church in Scandinavia have been favoured fields of research during the last two decades; new knowledge has been gained, and long-accepted truths have been challenged. We now have a fairly good picture of how the Christianization process developed, and the stress has been on process, challenging an older stance in research, which rather favoured the impact of individuals, specific important events, and a ‘nat1 See e.g. Hafström, ‘Sockenindelningens ursprung’. Early Ecclesiastical Organization of Scandinavia, Especially Sweden 25 ural’ growth of the new religion in the form of individuals converting to the new religion. Against this older position, most recent researchers analysing the process have argued for a top-down process.2 Christianization in Scandinavia may be divided into various phases. A three-phase development has been proposed by Fridtjof Birkeli; favoured by many, it consists of: 1) an infiltration phase, 2) a missionary phase, and finally 3) an establishment phase.3 For the later process of ecclesiastical organization I would also propose three phases: 1) An infiltration phase, during which foreign clergymen stayed with kings and chieftains in Scandinavia, acting as counsellors on religious and other matters. This first phase occupied roughly the latter part of the tenth century and the eleventh century (see Map 1). We have indications of earlier attempts, such as Anskar’s travels to Denmark and Birka in Sweden in the ninth century, mentioned in the Vita Anskarii, but we do not know what impact these early missionaries had in Scandinavia. Instead we have to rely on archaeology, which at the moment can substantiate Christian burials in Scandinavia from around the middle of the tenth century (and perhaps already at the beginning of that century), and remnants of some small wooden churches from the latter half of the same century. 2) A rather obscure phase, during which: churches were built, especially at royal strongholds; bishops were ordained to certain centres and markets, ports, and proto-towns which were obviously also under the control of a king, such as Lund, Roskilde, Sebbersund, Hedeby, Ribe, Skara, Sigtuna, Nidaros, and so forth (see Map 2); and many small private churches, as was probably the case, were built. During this phase, which took place in the late eleventh and twelfth centuries, the first sees were established in Scandinavia; we may label it the ‘large-scale organization phase’. 2 See e.g. Kristnandet i Sverige, ed. by Nilsson; Nilsson, Sveriges kyrkohistoria, i: Missionstid och tidig medeltid; Hjalti Hugason, Kristni á Íslandi, i: Frumkristni og upphaf kirkju; Jón Viðar Sigurðsson, Kristninga i Norden, 750–1200; Kristendommen i Danmark før 1050, ed. by Lund; Religionsskiftet i Norden, ed. by Jón Viðar Sigurðsson and others. 3 Birkeli, Norske steinkors i tidlig middelalder, p. 14; see e.g. Gräslund, Ideologi och men­ talitet, p. 19. Stefan Brink 26 3) The third phase, during which parishes were formed, tithes were introduced, and a priest became attached to many parish churches. This constituted the final and small-scale ecclesiastical organization of Scandinavia, taking place in the late twelfth but mainly the thirteenth century, when the church took a firm grip on the Scandinavian realm, organized itself territorially, and fully integrated itself into society.4 The first phase we can grasp, and the third we can reconstruct, but what about the second? The Early Church Phase The solution of the early church to the problem of ecclesiastical organization in northern Europe laid the foundations for a type of church which was socially very biased towards the elite. First, we have the older Episcopal churches in the cities (civitates). More numerous were the later private or proprietary churches, or Adelskirchen, ‘churches of the nobility’; hence the private churches on the manors of landlords’ estates, which eventually — after a long period of struggle and negotiations — came under the control of the papacy and the bishops.5 We seem to have a similar development in Scandinavia, but taking place somewhat later in date. The picture of the early church in Scandinavia, with missionaries attached to kings, is well established in research today. But the term ‘missionaries’ has the misleading connotation of holy men moving around, preaching, and baptizing; I would prefer instead to label them ‘counsellors’, who stood beside the itinerant kings and gave them advice — probably not only on religious matters.6 These bishop-counsellors were attached to the itinerant royal courts, being part of the king’s retinue (hirð), and they dealt primarily with kings, princes, noble warriors, and ‘women who wove aristocratic dynasties together in marriage’.7 The people with whom they interacted were the rich and the influential, who could afford to build churches and found religious communities which they could populate with their kinsfolk and dependants. It is notable, however, that at least in Sweden, for some reason, no monasteries were founded during this early phase. The lack of monasteries as a driving 4 Brink, Sockenbildning och sockennamn. For a background and overview, and also for references, see Wood, The Proprietary Church in the Medieval West. 6 Wood, The Missionary Life. 7 Fletcher, The Conversion of Europe, p. 455. 5 Early Ecclesiastical Organization of Scandinavia, Especially Sweden 27 force in the early phase of the Christianization of Sweden especially is rather remarkable when we compare it with northern Europe as a whole.8 The first churches seem to a large extent to have been built under the control of the kings and on their land, in the case of Sweden especially on estates and farms called husaby, making up the vital part of the regal economic assets (bona regalia) of the Swedish king, in the early Middle Ages called Uppsala ødh, literally ‘the wealth of Uppsala’.9 On these husabyar, we often find exceptional medieval stone churches, each with one or two steeples, intended to impress. Most of these churches probably had predecessors in the form of much smaller wooden churches built in the eleventh century. Of a few of these we have some remaining archaeological traces, but for the majority we have to rely on informed guesswork. The 1152 visit of the papal legate Cardinal Nicholas Breakspear (later Pope Adrian IV, r. 1154–59) to Norway (and later to Sweden)10 has been interpreted as a decisive event for the organization of the church in Scandinavia. One important result of this visit seems to have been the establishment of tithes, or rather the laying of a greater stress on the importance of introducing it, for this was something which Pope Gregory VII (r. 1073–85) had already emphasized in a letter to the Swedish king Inge around 1080. Tithes must have been the fundamental prerequisite for the organization of the church, and in particular for the establishment of parishes with their own priests. We can see in some of the Swedish provincial laws how part of the tithe-money was used for the priest’s stipend (beneficium), part was for maintenance and extension of the fabric of the church (fabrica), part was directed to the bishop, and in some regions part was devoted to helping the poor, this part being called fattigtionde (‘tithe for the poor’). In an early phase there were obviously also certain one-off taxes, such as the huvudtionde, literally ‘main tithe’, which is believed to have been paid out for the building of the first churches.11 With an active church backed up by the royal houses and the nobility, the more or less accepted payment of tithes, and the establishment of the benefi­ cium, the mensa, or fundus (in principle the vicarage) and a church’s fabrica, the way was paved for the final and decisive phase of the organization of the church 8 Nyberg, ‘Early Monasticism in Scandinavia’; see also Nyberg, Monasticism in NorthWestern Europe. 9 Brink, ‘Husaby’. 10 Nilsson, Sveriges kyrkohistoria, p. 95. 11 Lindkvist, ‘Kyrklig beskattning’, p. 219. Stefan Brink 28 and its ‘infiltration’ of the Scandinavian provinces and bygder (‘settlement districts’) — that is, the formation of parishes. In the late 1980s, I was very much concerned with the process of parishformation in Scandinavia, and I tried to ascertain whether or not it was rapid and uniform all over Scandinavia, which was the view found in textbooks.12 I could see that the introduction of tithes must have been decisive, but it was an introduction which suffered many setbacks and much resistance in many regions. As late as 1232, Pope Gregory IX (r. 1227–41) instructed the deans in Västerås, Sigtuna, and Aliati to force the people in the province of Hälsingland to pay their tithes, and to repay the archbishop of Uppsala the sum of money he had had to pay out on their behalf in consequence of their negligence.13 The other fundamental aspect of the organization was the churches themselves. In many parts of Scandinavia there were a number of churches already in existence when the process of parish formation began, but in other parts it looked to me as if there were no churches being built before the process of parish formation. In these latter cases, I assumed that the church and the bishops must have taken an active role in the building of churches and the creation of parishes.14 New Emerging Evidence The picture sketched above is one which I have been forced to modify. The background to this is provided by some very important archaeological excavations in Norway, Denmark, Iceland, and Sweden, from which I shall pick out a couple of examples. The first of these excavations took place at the hamlet of Björned, which was formerly a farm, and which is situated in Torsåker parish in the province of Ångermanland, in northern Sweden. On this farm, the archaeologist Leif Grundberg has excavated a small and obviously Christian graveyard measuring approximately 25 m × 12 m.15 It is not known what the shape of the graveyard was or whether its boundary was marked with a dyke. Around a hundred individuals were buried there, men to the south, women to the north, some with and some without wooden coffins. Over the period from c. 1000 to c. 1250/1300, the number of individuals buried probably corresponds to that of a farm inhab12 See Brink, Sockenbildning och sockennamn (passim) for a discussion and further references. Brink, Sockenbildning och sockennamn, p. 144. 14 Brink, ‘Tidig kyrklig organisation i Norden’. 15 Grundberg, Medeltid i centrum, pp. 61–72. 13 Early Ecclesiastical Organization of Scandinavia, Especially Sweden Burial mound Settlement site Burial ground Figure 1. Burial ground in Björned, Torsåker parish. Drawing: Leif Grundberg. 29 Stefan Brink 30 ited by between six and ten people — a normal size for a Viking Age farm. DNA analyses of the remains of skeletons in the graves show that those buried there were close relatives. In the middle of the burial ground is a small area with no graves, which may be interpreted as the site of a small wooden church (perhaps measuring approximately 10 m × 5.5 m). What we have here in Björned is probably a small private church with a Christian burial ground for the farm (see Figure 1). The pagan burials found in a cemetery close to the Christian graveyard on the farm were apparently abandoned around the year 1000. Thereafter people were buried in the small Christian graveyard until the thirteenth century. From the second half of the thirteenth century, no burials are known on this farm. This must coincide with the process of parish formation. When a tithe was introduced, a church at the nearby Torsåker was chosen as the parish church. This church may already have been in existence since — to judge from the place name, which means ‘the arable land dedicated to [the god] Þórr’ — Torsåker must have been the old assembly and cult site for the district.16 At that time, the baptismal and burial rights were transferred to Torsåker church, and Björned church and graveyard were abandoned. The second example is the discovery and excavation in 2002 of a small church and Christian graveyard on a farm called Keldudalur in northern Iceland.17 This is quite similar to what has been found at Björned. In the middle of a small, round cemetery, measuring approximately fifteen metres in diameter, were traces of a church (approximately 5 m × 5 m in size). Around fifty graves were found, some with wooden coffins; men to the south, women to the north, and children close to the church. The church was built over an older Viking Age longhouse, which had been covered by a layer of tephra (volcanic ash) dating from c. 1000. Tephra layers and radiocarbon dating show that this graveyard was in use from c. 1000 to the middle of the twelfth century, that is, for around 150 years. The picture that emerges from such archaeological evidence is one in which many, perhaps nearly all large farms in the eleventh century had their own small private church. This picture for Scandinavia is also substantiated by the observations made by Dagfinn Skre, when he analysed the farms in SørGudbrandsdalen in Norway, where he could archaeologically identify, or at least obtain indications of the existence of, many small churches on the farms.18 It seems, then, that already at an early phase of the Christianization process we 16 Brink, ‘Cult Sites in Northern Sweden’, p. 466. Zoëga and Ragnheiður Traustadóttir, ‘Keldudalur’. 18 Skre, Gård og kirke, bygd og sogn. 17 Early Ecclesiastical Organization of Scandinavia, Especially Sweden 31 are dealing with small wooden churches on most or at least many of the farms, churches which had no place and function when the new parish system was introduced in the twelfth century and established in the thirteenth century, for large parts of Scandinavia. For the province of Västergötland in particular, we have several of these small and early stone churches which were abandoned when they became superfluous to the new parish structure, and which today are preserved as ruins. The Intermediate Phase Our next problems are the following: Who conducted the services in these small churches? Where did the priests come from? Where did the priest live? And how is it possible to understand the intermediate phase between, on the one hand, the early Adelskirche phase, with ‘bishops’ attached to the itinerant kings in their courts and all the small churches on farms; and on the other, the parish-formation phase, with parish churches, each with its own priest, to be found all over Scandinavia? When we take a retrospective look back in history, the parish system, which dates mainly from the thirteenth century, creates a pattern so dense that it must obscure any earlier pattern. Consequently we have to work with written sources which are scarce and problematic, we have to propose models inspired by comparisons with better-known societies, and we have to rely on guesswork. A most fruitful model for comparison has been that proposed by John Blair and others to describe Anglo-Saxon England. This model, labelled the ‘Minster hypothesis’ by its critics, has been intensely discussed and often criticized. The idea is that there were ‘mother churches’ of some kind, each with a collegium of priests, normally under the supervision of a bishop, and they had pastoral care for a large community or parochia.19 We find a similar development on the Continent, in Gaul at least, in the sixth century.20 We had the old public or baptismal churches in the cities and the emerging private oratories, built by a bishop or a lord in the grounds of his villa. In the latter the lord’s household was allowed to attend Mass but had to go to the cathedral or parish church for the great feasts and for baptism. The word parochia still had the meaning of the bishop’s territory — the large, loosely 19 See e.g. Minsters and Parish Churches, ed. by Blair; and Pastoral Care before the Parish, ed. by Blair and Sharpe. 20 See Wood, The Proprietary Church in the Medieval West, p. 66. Stefan Brink 32 defined region served by him and his clergy. In the later sixth and the following centuries this changed fundamentally. From now on functions and revenues, once reserved for a few major churches, were taken over by the many new private churches, which eventually became parish churches. On the other hand, the proprietary attitudes and concepts once restricted to the private oratories eventually came to be applied to many major and hence once-public churches.21 In this process, when many estates still lacked any private church, the bishop could build and endow new churches and create large new parishes.22 In northern parts of the Continent, in Frankish conquests, with late Christianization and few churches, pastoral care came at first from missionary monasteries.23 These churches, built and owned by a bishop, a king, or a monastery, could serve very large and loose parishes, and some old churches could keep their baptismal rights over vast parishes as late as the eleventh century. This situation, with active monasteries functioning as important missionary centres, differs fundamentally from the Scandinavian situation, where monasteries were late establishments (especially in Sweden) and took no initial part in the Christianization process. A Scandinavian Version of the Minster Hypothesis? There are several of us who have used this kind of model to try to understand the phase in Scandinavian history before the formation of parishes, including Jørn Sandnes for Trøndelag, Dagfinn Skre for Romerike, and myself for Hälsingland and Gotland.24 According to the ‘Minster hypothesis’, Anglo-Saxon kings in the seventh and eighth centuries built minsters and created a system of minsterchurches with large parochiae, often coinciding with small kingdoms or other areas of royal administration. The nobility could found minsters with parochiae corresponding to their landed estates. The idea is that these minsters were not only serving the needs of the royal household or the lords on their estates but were active in spreading Christianity and serving the emerging Christian community around each minster. Soon a group of clergy were responsible for the 21 Wood, The Proprietary Church in the Medieval West, p. 67. Wood, The Proprietary Church in the Medieval West, p. 70. 23 Wood, The Proprietary Church in the Medieval West, p. 79. 24 A good introduction to and discussion of this English Minster hypothesis applied to Scandinavia and Iceland has recently been written by Antonsen, ‘The Minsters’. See also Brink, ‘New Perspectives on the Christianization of Scandinavia’, pp. 172–75. 22 Early Ecclesiastical Organization of Scandinavia, Especially Sweden 33 pastoral care of a large area, the parochia.25 The criticisms raised against this hypothesis are that it is not recorded in written sources, that it is doubtful that monastic institutions (minsters) should have been so active in society, and that the active role of bishops is questionable.26 From a Scandinavian point of view, there is another problem with the ‘Minster hypothesis’, namely that of chronology. Already in the ninth and especially the tenth century it is assumed that in England the organization of minster parochiae declined when new churches on private estates and smaller parishes became the norm. In Scandinavia, on the other hand, the ‘Minster hypothesis’ model has been assumed to have been functioning in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, so it is difficult to see how we could have a direct transfer from England at that time. Although there are problems with a direct transfer of the model from Anglo-Saxon England to Scandinavia, the ‘Minster hypothesis’ may nevertheless, in my opinion, serve as a possible or even probable model for the activities of the early church in large parts of Scandinavia. It is not so far-fetched to assume that the early churches built on royal estates and farms, such as the husabyar, may have served as ‘mother churches’ where a group of clergy, under the supervision of a bishop, spread the word and conducted ritual service over a large area, a ‘storsocken’ (i.e., a large parochia). The systematic distribution of early churches on these husabyar, as well as the survival of certain relict terms, may support such a hypothesis. The clergy which may be assumed to have been resident at these ‘mother churches’ were probably funded by the king and the bishop, but they must have had another source of income in a period when tithes were not yet in use. This must have been payment for the services the clergy conducted, presumably at the many small private churches in their parochiae. A reminiscence of this system can probably be seen in the Old Gulathing Law, used in western Norway. The church laws, which are considered to be the oldest in the law, very often have two parallel texts, called Olav’s text and Magnus’s text,27 where the former no doubt is more archaic than the latter. In the Olav’s text a priest is obviously designated to some farmers or district, from where he could collect money for the services he conducted, but a parish is not mentioned in the Olav’s text, nor are tithes, although these are noted in the 25 For a recent discussion of this ‘Minster-model’, see Blair, The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society. Cf. Rollason and Cambridge, ‘The Pastoral Organization of the Anglo-Saxon Church’; Palliser, ‘The “Minster Hypothesis”: A Case Study’; and Rollason, ‘Monasteries and Society in Early Medieval Northumbria’. 27 Rindal, ‘Innleiing’, p. 9; Helle, Gulatinget og Gulatingslova, pp. 17–20. 26 Stefan Brink 34 later Magnus’s text. It has been assumed that the Olav’s text describes a society not yet fully integrated within a parish system, but rather in an intermediate phase.28 In the paragraph dealing with the procedure of ‘arveøl’ (erviol, ‘inheritance beer’), we read that when someone had died the heir should go to the priest and ask him to come and sing what is called the ‘corpse’s song’ (liksong) over the deceased; the Olav’s text continues by saying that for this service, the priest should be paid one and a half øre, ‘which sum people call the buying of the corpse’s song’ (liksongs kaup).29 In the same paragraph we find another interesting passage: When people make [funeral] beer and call it ‘soul’s beer’ (salo ol), they should invite the priest from whom they normally buy Masses.30 In these cases it is obvious that people do not come to the church for religious services (which is the case in the later Magnus’s text), but that the priest is moving around between farms, whether within a ‘parish’ or not (parishes are in any case not mentioned in the Olav’s text), conducting Masses and other religious services. Alexander Bugge has highlighted this passage of the Gulathing Law, and looks upon this funeral beer ritual as an old pagan custom, taken over by the church and incorporated and transformed into a Christian religious ritual, for the benefit of the deceased’s soul.31 If Bugge is correct, which seems more than plausible, this connects with the aspiration of the early church to include and transform pagan customs into Christian rituals. We also possess the word probably used for this kind of payment for service — reiða (payment, fee) — although later on it acquired other meanings.32 In the Norwegian laws we read of prestreiða, which in a later phase, in the Borgarthing law, evolved into an annual fee consisting of butter and flour for a year for the priest, a fee also called Olavssåd. In return, the priest was to conduct prescribed services during the year, although he was still to be paid separately for some special rites. Another kind of fee for the performance of rites was gipt, which also means ‘gift’ or ‘present’. I think it is possible to pick out relict words like these and use them to build up this hypothetical model of a system of mother 28 Helle, Gulatinget og Gulatingslova, p. 205. ‘En þa er maðr er dauðr oc ferr ervíngi efter preste oc biðr hann til fara of syngía ivír liksong. hann scal til fara oc syngía ivir likí. [Olafr] oc skal hann þar fíri hava halvan eyrí. þat kalla menn liksongs kaup’ (Den eldre Gulatingslova, ed. by Eithun, Rindal, and Ulset, pp. 46–47). 30 ‘En ef menn gera ol. oc kalla salo ol. þa scolo þeír til bioða preste þeím er þeír kaupa tiðír at’ (Den eldre Gulatingslova, ed. by Eithun, Rindal, and Ulset, p. 47). 31 Bugge, Studier over de norske byers selvstyre og handel før Hanseaternes tid, p. 65. 32 See Bjørkvik, ‘Reide’. 29 Early Ecclesiastical Organization of Scandinavia, Especially Sweden 35 churches (in Norway called höfuðkirkjur or fylkiskirkjur, in Sweden hunda­ reskirkior, etc.) with a group of clergy attached to each of them, each group serving a large parochia without defined territorial boundaries, and being paid fees (reiða or gipt) as recompense for performing their clerical duties. This seems to be a plausible model for the organizational structure of the period between the first phase of Christianization, with ‘bishops’ and clergy acting as councillors attached to kings, and the fully developed parish structure, covering more or less the whole of Scandinavia. This intermediate period should then be dated approximately to the eleventh and twelfth centuries. The transfer of the ‘Minster hypothesis’ model of an early parish formation from Anglo-Saxon England to Scandinavia nevertheless remains speculative, although possible. We do, however, have another case of cultural exchange between medieval England and Scandinavia, namely the concept of sókn, soke, and hence of the parish itself.33 The Old Norse word sókn is the same word as Middle English soke and Old English sôcn. The Old Scandinavian word was originally one of the more frequently used and more important words in the legal language, with the meaning ‘the process of suing someone; a trial’. The intricate problem to be explained here is why, in the early phase of the church in Scandinavia, this word is used in the ecclesiastical realm as the word for a parish, and found with this meaning all over Scandinavia, except for Iceland. This drastic and geographically far-reaching change must have an explanation. The discussion of the interrelation between OE sôcn and ON sókn has two sides. One group of scholars see sôcn as a native Anglo-Saxon word; the other as a loanword from Old Danish (in the Danelaw). The historian Frank Stenton has argued the latter,34 and recently Peter Sawyer has also supported this position, arguing that the Scandinavian conquerors and their descendants in Lincolnshire in the tenth century used the word sôcn to describe estates or lordships and continued to do so long after the West Saxon kings had regained power there.35 J. E. A. Jolliffe and others have argued instead that the word is originally of Anglo-Saxon origin, analogous with the Northumbrian shires which had already arisen in a pre-feudal stage.36 33 See Brink, ‘The Formation of the Scandinavian Parish’, pp. 33–37; Fellows-Jensen, ‘Old English sôcn “soke” and the Parish in Scandinavia’. 34 Stenton, ‘An Introduction’. 35 Sawyer, Anglo-Saxon Lincolnshire, pp. 107–08. 36 Jolliffe, ‘The Era of the Folk in English History’. The Northumbrian shire has recently been discussed by the geographer Roberts, Landscapes, Documents and Maps, pp. 151–87. For 36 Stefan Brink For the Scandinavian situation one explanation worth considering is that the ecclesiastical term was borrowed outside Scandinavia, quite independently of ON sókn, thus producing a homonym of sókn with a quite new meaning. There is some evidence for OE sôcn acquiring in the tenth century the additional meaning of ‘parish’ or ‘the congregation attached to a lord’s church’. 37 With the close contacts between England and Scandinavia in the early eleventh century, and with Cnut the Great ruling both England and large parts of Scandinavia — and hence organizing the church there — we have at least the prerequisites for this English usage to have been transferred to Scandinavia with the creation of the new homonym sókn.38 No final conclusion has yet been reached regarding this sôcn/sókn problem. It may be a Scandinavian contribution to the Anglo-Saxons, a word used in the Danelaw by the Danes, later transferred and incorporated into the English language. Or it may be the other way around, an Anglo-Saxon word and concept transferred to Scandinavia during the early organization of the church — if so, most probably with the English clergymen, who seem to have been decisive for organizing the early church in Scandinavia. We can thus finish with another interesting hypothesis linking England and Scandinavia during this vital period of cultural exchange between the two. a short introduction to the debate about the origin of English soke, see Fellows-Jensen, ‘Old English sôcn “soke” and the Parish in Scandinavia’, pp. 102–03. 37 See Brink, ‘Sockenbildningen i Sverige’, pp. 117–18. 38 This could be interpreted in the same way that solskıifte ‘sun division’ has been explained by Sölve Göransson: ‘The bulk of the evidence suggests that the Scandinavian solskifte was in fact derived from England during the period of close political, ecclesiastical and cultural contact between these countries (tenth to twelfth centuries)’; Sölve Göransson, ‘Regular Open-field Patterns in England and Scandinavian Solskifte’, p. 101. Early Ecclesiastical Organization of Scandinavia, Especially Sweden 37 Works Cited Secondary Studies Antonsen, Haki, ‘The Minsters: A Brief Review of the “Minster Hypothesis” in England and Some General Observations on its Relevance to Scandinavia and Iceland’, in Church Centres in Iceland from the 11th to the 13th Century and their Parallels in Other Countries, ed. by Helgi Þorláksson (Reykholt: Snorrastofa, 2005), pp. 175–99 Birkeli, Fridtjov, Norske steinkors i tidlig middelalder: et bidrag til belysning av overgangen fra norrøn religion til kristendom, Skrifter utg. av Det Norske Videnskaps-Akademi i Oslo, 2: Hist.-filos. klasse, n.s., 10 (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1973) Bjørkvik, Halvard, ‘Reide’, in Kulturhistoriskt lexikon för nordisk medeltid, ed. by John Danstrup and others, 22 vols (Malmö: Allhems, 1956–78), xiv: Regnebraet–samgäld (1969), pp. 10–11 Blair, John, The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005) —— , ed., Minsters and Parish Churches: The Local Church in Transition, 950–1200, Oxford University Committee for Archaeology, 17 (Oxford: Oxford University Com­ mittee for Archaeology, 1988) Blair, John, and Richard Sharpe, eds, Pastoral Care before the Parish (Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1992) Brink, Stefan, ‘Cult Sites in Northern Sweden’, in Old Norse and Finnish Religions and Cultic Place-Names, ed. by Tore Ahlbäck, Scripta Instituti Donneriani Aboensis, 13 (Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1990), pp. 458–89 —— , ‘The Formation of the Scandinavian Parish, with Some Remarks Regarding the English Impact on the Process’, in The Community, the Family and the Saint: Patterns of Power in Early Medieval Europe, ed. by Joyce Hill and Mary Swan, International Medieval Research, 4 (Turnhout: Brepols, 1998), pp. 20–44 —— , ‘Husaby’, in Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde, ed. by Rosemarie Müller, 2nd edn, 35 vols (Berlin: Gruyter, 1973–2007), xv: Hobel–Iznik (2000), pp. 274–78 —— , ‘New Perspectives on the Christianization of Scandinavia and the Organization of the Early Church’, in Scandinavia and Europe, 800–1350, ed. by John Adams and Kathy Holman, Medieval Texts and Cultures of Northern Europe, 4 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2004), pp. 163–75 —— , ‘Sockenbildningen i Sverige’, in Kyrka och socken i medeltidens Sverige, ed. by Olle Ferm (Stockholm: Riksantikvarieämbetet, 1991), pp. 113–42 —— , Sockenbildning och sockennamn: studier i äldre terrotoriell indelning, Acta Academiae Regiae Gustavi Adolphi, 57 (Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1990) —— , ‘Tidig kyrklig organisation i Norden — aktörerna i sockenbildningen’, in Kristnandet i Sverige: gamla källor och nya perspektiv, ed. by Bertil Nilsson, Sveriges kristnande, 5 (Uppsala: Lunn, 1996), pp. 269–90 Bugge, Alexander, Studier over de norske byers selvstyre og handel før Hanseaternes tid (Christiania: Grøndahl, 1899) 38 Stefan Brink Fellows-Jensen, Gillian, ‘Old English sôcn “soke” and the Parish in Scandinavia’, Namn och bygd, 88 (2000), 89–106 Fletcher, Richard, The Conversion of Europe: From Paganism to Christianity, 371–1386 ad (London: Fontana, 1998) Gräslund, Anne-Sofie, Ideologi och mentalitet: om religionsskiftet i Skandinavien från en arkeologisk horisont, Occasional Papers in Archaeology, 29 (Uppsala: Institutionen för arkeologi och antik historia, Uppsala universitet, 2001) Grundberg, Leif, Medeltid i centrum: Europeisering, historieskrivning och kulturarvsbruk i norrländska kulturmiljöer, Studia Archaeologica Universitatis Umensis, 20 (Umeå: Institut för arkeologi och samiska studier, Umeå universitet, 2006) Hafström, Gerhard, ‘Sockenindelningens ursprung’, in Historiska studier tillägnade Nils Ahnlund, ed. by Sven Grauers and Åke Stille (Stockholm: Norstedt, 1949), pp. 51–67 Helle, Knut, Gulatinget og Gulatingslova (Leikanger: Skald, 2001) Hjalti Hugason, Kristni á Íslandi, 4 vols (Reykjavík: Alþingi, 2000) Jolliffe, J. E. A., ‘The Era of the Folk in English History’, in Oxford Essays in Medieval History Presented to Herbert Edward Salter, ed. by F. M. Powicke (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1934), pp. 1–32 Jón Viðar Sigurðsson, Kristninga i Norden, 750–1200 (Oslo: Norske samlaget, 2003) Jón Viðar Sigurðsson, and others, eds, Religionsskiftet i Norden: brytinger mellom nordisk og europeisk kultur, 800–1200 e.Kr., Centre for Viking and Medieval Studies: Occasional Papers, 6 (Oslo: Unipub, 2004) Lindkvist, Thomas, ‘Kyrklig beskattning’, in Sveriges kyrkohistoria, ed. by Lennart Tegborg and Bertil Nilsson, 7 vols (Stockholm: Verbum, 1998–2005), i: Missionstid och tidig medeltid, ed. by Bertil Nilsson, pp. 216–21 Lund, Niels, ed., Kristendommen i Danmark før 1050 (Roskilde: Roskilde Museum, 2004) Nilsson, Bertil, Sveriges kyrkohistoria, 7 vols (Stockholm: Verbum, 1998–2005) —— , ed., Kristnandet i Sverige: gamla källor och nya perspektiv, Sveriges kristnande, Pub­ lika­tioner 5 (Uppsala: Lunn, 1996) Nyberg, Tore, ‘Early Monasticism in Scandinavia’, in Scandinavia and Europe, 800–1350: Contact, Conflict, and Coexistence, ed. by John Adams and Kathy Holman, Medieval Texts and Cultures of Northern Europe, 4 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2004), pp. 197–208 —— , Monasticism in North-Western Europe, 800–1200 (London: Ashgate, 2000) Palliser, David M., ‘The “Minster Hypothesis”: A Case Study’, Early Medieval Europe, 5 (1996), 207–14 Rindal, Magnus, ‘Innleiing’, in Den eldre Gulatingslova, ed. by Bjørn Eithun, Magnus Rindal, and Tor Ulset (Oslo: Rigsarkivet, 1994), pp. 7–28 Roberts, Brian K., Landscapes, Documents and Maps: Villages in Northern England and Beyond, ad 900–1250 (Oxford: Oxbow, 2008) Rollason, David, ‘Monasteries and Society in Early Medieval Northumbria’, in Monasteries and Society in Early Medieval Britain, ed. by Benjamin Thompson and Paul Watkins (Stamford: Watkins, 1999), pp. 59–74 Rollason, David, and Eric Cambridge, ‘The Pastoral Organization of the Anglo-Saxon Church: A Review of the “Minster Hypothesis”’, in Early Medieval Europe, 4 (1995), 87–104 Early Ecclesiastical Organization of Scandinavia, Especially Sweden 39 Sawyer, Peter, Anglo-Saxon Lincolnshire, A History of Lincolnshire, 3 (Lincoln: Lincolnshire Local History Society, 1998) Skre, Dagfinn, Gård og kirke, bygd og sogn: organiseringsmodeller og organiseringsenheter i middelalderens kirkebygging i Sør-Gudbrandsdalen, Riksantikvarens rapporter, 16 (Øvre Ervik: Alvheim & Eide, 1988) Sölve Göransson, ‘Regular Open-field Patterns in England and Scandinavian Solskifte’, Geografiska Annaler, 43 (1961), 80–101 Stenton, Frank M., ‘An Introduction’, in The Lincolnshire Domesday and the Lindsey Survey, ed. by C. W. Foster and Thomas Longley (Lincoln: Publications of the Lincoln Record Society, 1924), pp. ix–xlvi Wood, Ian, The Missionary Life: Saints and the Evangelisation of Europe, 400–1050 (Harlow: Longman, 2001) Wood, Susan, The Proprietary Church in the Medieval West (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006) Zoëga, Guðný, and Ragnheiður Traustadóttir, ‘Keldudalur – A Sacred Place in Pagan and Christian Times in Iceland’, in Cultural Interaction between East and West: Archaeology, Artefacts and Human Contacts in Northern Europe, ed. by Ulf Fransson and others, Stockholm Studies in Archaeology, 44 (Stockholm: Stockholms universitet, 2007), pp. 225–30 Canonical Observance in Norway in the Middle Ages: The Observance of Dietary Regulations Sæbjørg Walaker Nordeide and Jennifer R. McDonald T his paper examines the extent to which Norwegian society was permeated by canonical conventions, and specifically by the church’s regulations concerning food. By highlighting people’s relationship with certain animals and meats in Norway before and after Christianization through norms (law) and practice (archaeological evidence), we ask if and how this relationship changed after the introduction of Christianity with its legal code and conventions. The primary legal sources used here are canon law itself and the provincial law codes of early medieval Norway, as well as the later 1274 Landislaw Code and the 1276 Town Code. The archaeological data investigated are primarily animal bones from two regions under two different early medieval provincial laws. We demonstrate that Christian dietary regulations did not have much impact on the daily Norwegian diet but did influence aspects of Old Norse cult practice, which in general was prohibited. Local religious differences in relation to animals in the Viking Age may explain some of the differences in the early medieval legislation. The evidence also shows that these regulations were generally followed by society, but with some important exceptions and surprising nuances. At the same time greater changes are observed in species not regulated by canon law than species included in the regulations. Sæbjørg Walaker Nordeide (swanord@gmail.com) is a researcher, and Jennifer McDonald was postdoctoral fellow, both at Universitetet i Bergen. Medieval Christianity in the North: New Studies, ed. by Kirsi Salonen, Kurt Villads Jensen, and Torstein Jørgensen, AS 1 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013) pp. 41–66 BREPOLS PUBLISHERS 10.1484/M.AS-EB.1.100811 Sæbjørg Walaker Nordeide and Jennifer R. McDonald 42 Introduction Diet is an important part of culture and individuals’ identity, and food regulations present possible consequences for individuals several times every day. The study of dietary regulations is thus a study of the impact of Christianization on daily life, and this chapter examines the extent to which these regulations permeated medieval Norwegian society. The legal conventions concerning diet — promulgated by the international church and instituted locally by rulers and clergy — will be assessed against a backdrop of archaeological evidence. This analysis will examine society’s relationship with animals and meats in late Iron Age Norway (ad 560–1050) and how this changed after the introduction of Christianity and its legal code and conventions in the early Middle Ages (from ad 1050). The legal sources combined with the archaeological data will serve to highlight just how closely Norwegian society chose to adhere to, or deviate from, canonical conventions, as well as the provincial codes, concerning food. In line with the intentions of this volume, comparisons to similar trends in the British Isles and on the Continent will also be made to demonstrate conformity and deviation in the application of the canons concerning diet and food consumption in different regional contexts. Ecclesiastical Dietary Regulations Most peoples followed some form of dietary restrictions for religious reasons; for instance horses were not eaten by Jews, Muslims, Hindus, or early Christians.1 When, in the eleventh century, Christianity became the official religion in Norway, its rulers and clergy began, by legislative and other means, to eradicate all non-Christian religious practices. In the immediate aftermath of conversion, five Christian practices — marriage, the observance of feast and fast days, burials, and baptism — were introduced through ecclesiastical legislation.2 Laws on feasts and fasting also included a number of dictates concerning food and the types of foods which could and could not be consumed by Christians. The rationale behind the church’s dietary regulations is still debated by scholars. Certainly, some of these regulations were implemented to prevent non-Christian practices. Biblical tradition also played its part, with many of the regulations deriving directly from the Holy Scripture. The books of Leviticus 1 2 Gade, ‘Horses’. Sanmark, Power and Conversion, pp. 205–07. Canonical Observance in Norway in the Middle Ages 43 and Deuteronomy, for instance, forbade believers from consuming blood, animals that had died of natural causes, those that had been killed by beasts, those without split hooves but which chewed the cud, and swine because they have split hooves but do not chew the cud. 3 Food regulations are also given in the New Testament: the Book of Acts forbids the consumption of animals sacrificed in pagan worship or strangled.4 On the other hand, in the Gospel of Matthew (15. 11) it is stressed: ‘That which enters into the mouth doesn’t defile the man; but that which proceeds out of the mouth, this defiles the man’. There seem to have been further reasons behind the church’s regulations, however. These rules, undoubtedly, had practical implications, perhaps principally to prevent sickness and disease. Many medieval regulations in surviving English and Continental legislation forbid the consumption of dead animals for which the time and cause of death could not be ascertained.5 Other reasons behind these regulations may also have been to prevent society from consuming ‘polluted’ food. The Penitential of Theodore, for instance, forbids the consumption of the meat of an animal with which a man has had sexual intercourse.6 The church’s dictates concerning food were predominantly introduced during or immediately after the conversions which took place throughout Latin Christendom. At the time of Norway’s conversion, canon law was in a relatively early phase of its development, and only a few basic canons had been promulgated to address dietary issues, such as the prohibition of the meat and dairy products of warm-blooded animals, and of the same foods at certain feasts. 7 Some canons on diet, although not many, were promulgated during conversions in the Latin West, a direct result of local clerical aims to enforce these dietary regulations. For instance, Pope Gregory III (r. 731–41) forbade the eating of horseflesh after having received a letter from St Boniface (c. 731), indicating that his Christians were in the habit of consuming horseflesh.8 While local churches implemented the canons dictated by the church, local rulers and clerics throughout the Latin West also issued additional dietary regulations, pri3 Leviticus 7. 23–26, 17. 12–15, 22. 8; Deuteronomy 14. 6–21. Acts 15. 20, 15. 29; Matthew 15. 11. 5 Theodore of Canterbury, The Penitential (668–90). 6 Theodore of Canterbury, The Penitential (668–90), bk ii. 11. 9; On the concept of ‘pollution’ in medieval society, see, for example, Meens, ‘Pollution in the Early Middle Ages’; Douglas, Purity and Danger, pp. 29–40; Sanmark, Power and Conversion, pp. 219–25. 7 See, for example, Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Friedberg and Richter, i: Decretum Gratiani, pars III, d. 3, C. 1–30; pars III, d. 5, C. 16–33 (cols 1353–61 and 1416–21). 8 Willibald, Briefe, ed. by Rau. 4 Sæbjørg Walaker Nordeide and Jennifer R. McDonald 44 marily based on biblical regulations, such as those found in the Old Testament. Such examples include the earliest laws of the Anglo-Saxon kings and the Carolingian legislation. These local laws provide a much more specific context in which to assess the church’s dietary regulations and their impact on medieval society in different places. Other contemporary manuals also offer a unique insight into the impact of these regulations. Providing intense and sometimes very specific discussions behind these local regulations were the penitentials which circulated throughout Europe, such as that of Theodore, and the decretal collections of Regino of Prüm and Burchard of Worms. Dietary Regulations in Medieval Norway The Christian regulations promulgated in Norway were added to the four provincial codes, Gulathing Law, Eidsivathing Law, Borgarthing Law, and Frostathing Law,9 which regulated the four provincial jurisdictions into which early medieval Norway was divided and which remained in force until the thirteenth century.10 These codes originated at the meetings of law-making assemblies, law-things (Old Norse lögthing), which were established in each of these four districts. The three earliest Christian laws, those for the Gulathing, Eidsivathing, and Borgarthing districts, could be dated to the first part of the eleventh century, even though the exact origins and dates of these provincial codes are not certain.11 The earliest extant manuscripts containing them date to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The scholarly debate surrounding the date of these manuscripts will not be addressed here, as it has already been well documented. Nevertheless, it is worth noting in this context that these laws were introduced rather early, and certainly before similar legislation was enacted throughout the rest of Scandinavia. Scholars tend to agree that the first Christian codes issued in Norway were those added to the Gulathing Law, which were promulgated at the thing of Moster (c. 1020s).12 9 The Gulathing Law regulated the southwestern districts of Norway, while the Eidsivathing Law was established in southeastern Norway. The Eidsivathing Law district was divided into two regions, and a new provincial code was promulgated, the Borgarthing Law. The Frostathing Law was in force in central Norway, in the Trøndelag region. 10 The country was consolidated as a single entity (including mainland Norway, Iceland, Greenland, and the Hebridean and Orkney Isles) in the 1260s. 11 Rindal, ‘Liv og død i kyrkjas lover’. 12 See, for instance, the discussion in Sanmark, Power and Conversion, pp. 110–43; Sjöholm, Canonical Observance in Norway in the Middle Ages 45 each of these provincial codes provides unique insight into the ways in which church and secular authorities in early medieval Norway implemented Christian ideals in society. Dietary regulations are a particularly useful 240 km tool for gauging the topic, because adherence to these rules can be detected by an analysis of archaeological data. Particular attention is paid, in each of the codes, to the role which food played both in everyday life and in sacred settings. For the most part, these dietary regulations are similar in nature, although some regional variation can be noted. every code repeated the basic traditional canons on Map 3. The Norwegian medieval law districts. food. The meat and dairy products of warm-blooded animals were forbidden during the times of lent and other fasting periods, while the consumption of animals that had died of natural causes was also forbidden. While canonical conventions were repeated in these provincial statutes, most of the biblical rules, particularly those in the old Testament, were not. rather than repeating these rules — and in contrast to contemporary english and Continental legislation — the Norwegian codes provided a number of circumstances in which exceptions to these biblical regulations could be made. exceptions for animals which had died of natural causes are particularly noteworthy in this respect. These laws, for instance, permitted the consumption of animals which had been choked by their halter, which had ‘Sweden’s Medieval laws’; Sjöholm, Sveriges medeltidslagar; bagge, ‘elsa Sjöholm’; brink, ‘law and legal Customs in Viking Age Scandinavia’; Norseng, ‘law Codes as a Source for Nordic history’. Sæbjørg Walaker Nordeide and Jennifer R. McDonald 46 drowned, had fallen from cliffs, or were killed by falling trees.13 These exceptions were probably a response to actual cases brought before things. The laws did, however, make it clear that these exceptions were only exceptions to the rule, and not acknowledged Christian practice. They also provided certain instructions which were required to be undertaken should these exceptions ever arise. As the Gulathing Law declared: But men may eat what wolves rend and deprive of life; and men may eat the flesh of beasts attacked by bears or bitten by dogs. Men may also eat the flesh of a beast that is drowned in running water or falls over a cliff or is choked by the halter. But there is this to add about the flesh of animals that are killed in this way, that salt and water shall be consecrated and sprinkled upon the carcass, and it shall be hung up till the blood dries up. It is proper to sell the hide and divide the money in such a way that the owner keeps one-half; but with the other half let him buy the wax and send it to the church where he buys the divine services.14 Although none of the laws actually forbade the eating of sacrificed food, each code prohibited much of what was ritually consumed by non-Christian Scandinavians. Apart from the Frostathing Law, each prohibited the consumption of horseflesh, while the Borgarthing Law, in addition, prohibited the consumption of dogs and cats.15 The consumption of horseflesh had long been discouraged by Christian theology. The campaign against horse-meat goes back at least to the eighth century. Around the same time that St Boniface’s letter reached the pope in the eighth century, a papal mission to England condemned the eating of horsemeat among other ‘pagan customs’. An Irish penitential likewise condemned the practice, but not as a severe matter, noting, like Theodore in the seventh century, that ‘We do not forbid horse’s flesh, but it is not customary to eat it’.16 In the High Middle Ages, starvation often prompted the consumption of horseflesh, though it was generally viewed by most as unusual and repellent, and not as a pagan custom. It is uncertain, however, given the lack of written evidence, whether these regulations were decreed in the Norwegian provincial codes in response to a particular localized problem lingering from pre-Christian practice, or rather to 13 Borgarthing Law 1. 5; Eidsivathing Law 1. 26; Frostathing Law 2. 42; Gulathing Law 1. 20. Gulathing Law 1. 20. 15 Borgarthing Law 1. 5. Gulathing Law did not clearly forbid the consumption of dog, but according to 1:20 a person was permitted eat dog in case of necessity (‘he shall rather eat dog than dog eat him’). A similar formulation is found in Eidsivathing Law. 16 Theodore of Canterbury, The Penitential (668–90), bk ii.11.4. 14 Canonical Observance in Norway in the Middle Ages 47 show allegiance to contemporary Christian ideals. That each of the Norwegian provincial codes except the Frostathing Law prescribes harsh punishments for the consumption of horseflesh is nonetheless telling. It is interesting to note in this context that the Borgarthing Law prescribed the most severe penalty for consuming horseflesh: outlawry and exile. This was recommended by the code in only four other instances — in circumstances where individuals refused to baptize a child, to pay a tithe, or performed illegal marriages or divorces. The absence of textual evidence can to some extent be mitigated by archaeological sources, particularly concerning which type of food was consumed or not, as will be demonstrated below. But other aspects are more difficult to investigate, like the manner of the animal’s death and aspects of bestiality, as dietary regulations forbade not only foods used for ritual practices but also foods considered polluted. These included regulations against the consumption of animals involved in acts of bestiality. The Gulathing Law, albeit indirectly, forbade the consumption of a cow with which a man had had sexual intercourse. According to the regulation, the cow’s owner ‘shall drive her into the sea and shall make no further use [of her]. But if he does make use of her, he shall pay a fine of three marks to the bishop’.17 Other regulations, such as that noted in the Frostathing Law, forbade the consumption of foods which had been made unclean by contamination: If anything [that is] defiling drops into the food of men or into the ale, one may partake of it after having sprinkled hallowed water upon it; and one shall share it with the needy on the priest’s advice.18 In addition to forbidding food, the provincial codes also contained legislation about the types of foods that were to be consumed and when they should be consumed, especially during times of fasting and feasts. A number of regulations from the Frostathing Law are particularly notable in this respect: Statute 31: On the lesser gang day [April 25, dedicated to St Mark] all men shall partake of dry food [only fish and vegetables] and shall keep [the day] holy after midday. On three gang days one is allowed to work till midday but must fast till noon; but the fourth day is [to be kept] holy all day like a Sunday, for it is the day of our Lord’s ascension. Whoever fails so to keep these days shall pay three oras to the bishop for Monday or Tuesday or Wednesday, but six oras for Holy Thursday, if he works on that day.19 17 Gulathing Law, Appendix, no. 15. Frostathing Law 2. 42. 19 Frostathing Law 2. 31. 18 Sæbjørg Walaker Nordeide and Jennifer R. McDonald 48 Statute 32: It is further enacted that on the eve of the earlier St Mary’s Day and on the eve of All Saints’ Day all persons who are twelve winters old, or older, shall partake of bread and salt only […]. And the food that the husbandman and his wife would [regularly] eat on that day shall be given to the poor on the Mass day or three oras shall be given to the bishop.20 Statute 39: It is enacted that every man in good health who is fifteen winters old [or more] shall, while within our jurisdiction, fast on St Olaf ’s eve, eating only bread and salt, or pay six oras.21 Although the amounts varied among the regions, monetary fines were a common punishment for violating these dietary rules. But fines were not the only forms of punishment which the laws prescribed. The Frostathing Law dictated that any man who consumed flesh during Lent risked forfeiting ‘his right to peace among men everywhere [i.e., would become an outlaw] and his chattels to the bishop’.22 It seems that in Norway clergy and rulers actively considered practical needs when enacting certain dietary regulations. The Gulathing and the Borgarthing codes, for instance, both contain rules apparently promulgated to prevent the population from eating unsafe foods. 23 As Sanmark notes, these regulations certainly suggest that the compilers gave thought and consideration to their decrees. They are all the more revealing — and particularly those which provide exceptions — because they probably arose from actual legal cases.24 These regulations remained in force throughout the medieval period, though many were not rewritten into the laws when the country was unified under the lawcodes of King Magnus the Law-Mender (1274 (Landislaw Code) and 1276 (Town Code)). During the preparations of Magnus’s new laws, Archbishop Jon Raude had a new version of the Christian law worked out around 1273, but due to conflicts between the church and the king, these laws were never accepted as part of the new legal code. Thus the revised law codes from 1274 and 1276 did not include a proper, revised Christian law and contained no prohibitions against eating certain animals. It is unfortunately not known where, when, and to what degree Jon Raude’s Christian laws were valid. According to these laws 20 Frostathing Law 2. 32. Frostathing Law 2. 39. 22 Frostathing Law 2. 41. 23 Borgarthing Law 1. 5; Gulathing Law 1. 20. 24 Sanmark, Power and Conversion, pp. 226–27. 21 Canonical Observance in Norway in the Middle Ages 49 Christians could eat anything which was not prohibited given certain circumstances, but no species are mentioned. However, in the case of starvation one could eat anything except human flesh.25 It is important to note that it is typical of medieval legislation not to include older legal statutes in newer, more concise law codes, especially when the older statutes concerned matters which, for the most part, had become custom (con­ suetudo) among the people. The statutes concerning horse, cat, and dog flesh may not have been copied in Jon Raude’s Christian law simply because it had become customary in the kingdom not to eat those types of meat. Regulations in early medieval legislation in Norway concerning the eating of horseflesh and fasting are similar to Christian norms elsewhere, with the minor nuances addressed above. The provincial laws testify to a considerable knowledge of canon law even in a peripheral polity such as Norway in the early Middle Ages. However, the Borgarthing Law regulated more animal species than was the norm in other regions in Norway and in many countries. The background for this difference may reflect regional variations, which in turn may have caused differences regarding the consequences of and adaptation to canon law. The background and the practical application of the medieval dietary regulations are somewhat difficult to assess without the insights offered by archaeological data, to which we now turn. Archaeological Evidence In order to improve our understanding of some of the major regional differences in dietary regulations, we consider here the archaeological material from two regions: the Oslofjord region, with particular focus on the towns of Kaupang and Tønsberg in Vestfold, subordinate to the Borgarthing Law; and central Norway, with particular focus on the city of Trondheim, subordinate to the Frostathing Law. Investigating sacred26 and non-sacred settings demonstrates possible cultural or religious affiliations with the species mentioned, particularly cats, horses, and dogs. Both regions include coastal, cultivated landscapes with forested surroundings rich in both wild and domestic animals, and both regions include one or more early towns. As emphasized above, the Borgarthing Law and the Frostathing Law differ on food taboos: the 25 Personal information by Jørn Øyrehagen Sunde and Bjørg Dale Spørck, 2 December 2008; a translation of Jon Raude’s Christian law is Nyere norske kristenretter, trans. by Spørck. 26 Animal bones from sacred contexts are only found in non-Christian graves. Sæbjørg Walaker Nordeide and Jennifer R. McDonald 50 Borgarthing Law mentions certain species that should be avoided, while the Frostathing Law does not. The similar natural and structural contexts provide a good opportunity to investigate any possible cultural or religious reasons as background to the differences in legislation. Animal Bones from Sacred Contexts From time to time animal remains were associated with Old Norse (non-Christian) burials. Animals may have served several purposes at a Norse funeral: they may have been eaten during the funeral as part of the ritual, or they may have been given to the deceased as part of the grave goods. Animals may also have been sacrificed in the following years during ancestral or annual rites, but any bones from these kinds of rituals would normally be found outside the original grave. Several conditions may however bias the collections of animal bones from archaeological contexts: animal bones may not be collected, they may not be preserved, it may not be possible to identify the species, and it is rarely demonstrated whether the animal had been eaten or simply placed in the grave without any further exploitation. However, in each of these cases the animal has had some kind of Norse religious status. In the following, any animal traced in such a religious context will consequently be regarded as an important part of the background for the Christian laws: if any species had particular status in Old Norse religious cult, it may account for Christians avoiding these. Furthermore, comparing animal bones from sacred and secular contexts will strengthen or weaken the interpretation of the animal’s ritual status. Table 1 presents an overview of animal bones occurring (indicated by x) in a ritual context at some important sites from the time before/around Christianization in the Oslofjord region/Borgarthing Law district. Although a slightly different chronology exists between the cemeteries, two species generally dominate the grave material: the dog and the horse. There are, however, local variations between which animal was preferred: the dog or the horse. While normally the whole dog seems to have been put in the grave, other animals were mostly represented by their extremities alone. Normally, only the head of a horse is found in the grave, and even more often, only a harness is found, with no traces of the horse itself.27 A similar pattern is found in late Iron Age graves in Denmark.28 At Gulli in Vestfold there was also a ‘horse platform’ 27 28 Only (parts of ) horse skeletons are included in Table 1. Sanmark, Power and Conversion, p. 209. Canonical Observance in Norway in the Middle Ages 51 Table 1. Number of graves with various animal species recorded from Merovingian period/ Viking Age in the Oslofjord region. First two sites are from Østfold, the others from Vestfold. Site Date Store Dal 560–1050 Holøs 560–1050 Lille Gullkronen 560–1050 Gulli 900–1050 Tønsberg 800–1050 Kaupang 800–950 Cattle Sheep/Goat Dog Horse Bear Red deer Fish × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × Data for Store Dal, Holøs, and Lille Gullkronen collected from Mansrud, ‘Dyrebein i Graver’; Mansrud, ‘Dyret i jernalderens forestillingsverden’; for Lille Gullkronen also from Oslo, Kultur­ historisk museum, Universitetet i Oslo, Museum catalogue no. C22441. Data for Gulli from E18prosjektet Vestfold, ed. by Gjerpe; from Tønsberg from Nordmann, De arkeologiske undersøkelsene i Storgaten 18; Sælebakke, ‘Beskrivelse og analyser av de menneskelige skjelettfunn fra 4 jernaldersgraver i Tønsberg’; for Kaupang from Stylegar, ‘The Kaupang Cemeteries Revisited’. in the grave and horses were included among the grave goods between c. 900 and 1050.29 Perhaps this was because horses and other animals were consumed in a sacrificial meal associated with the burial, which again indicates a difference between dogs and other animals.30 This may again indicate that dogs were more like companions or guardians than food to the deceased, but the value and the size of horses compared to dogs may have mattered as well. We should also mention the exceptionally rich and well-preserved ship graves at Oseberg and Gokstad, both in Vestfold, in the Borgarthing Law province. The two women in the grave at Oseberg, buried in 834, were accompanied by fifteen decapitated horses, two oxen, and four dogs, all slaughtered for the burial. One horse was found in the grave chamber, standing, supported by clay.31 The grave goods included a lot of artefacts too, among others with animal decoration. The splendour and character of the find has led to the conclusion that at least one of the two women in the grave was more than a queen; she was also a cult leader, a völva, a ‘bearer of the staff ’. Some of the objects in this barrow are interpreted as having a pure cultic function, among others a richly carved wagon of the same kind as depicted on tapestries found in the grave 29 E18-prosjektet Vestfold, ed. by Gjerpe, pp. 136–37. Mansrud, ‘Dyret i jernalderens forestillingsverden’, Appendix 3. 31 Shetelig, ‘Graven’, p. 219. 30 Sæbjørg Walaker Nordeide and Jennifer R. McDonald 52 chamber. The wagon is decorated with nine cats, each with one paw up to its eyes, and one of the three sledges has a cat-themed decoration as well. The cat was Freya’s animal, and many symbols and artefacts in the burial suggest that the graves were a burial for a priestess of Freya, with the fertility cult as a central aspect.32 The ship grave at Gokstad also included at least twelve horses and six dogs, buried c. 900.33 The information in Table 1, and the barrows at Oseberg and Gokstad, indicate a close relationship between the deceased and some particular animal species, and also the ritual importance of these species, particularly in the Borgarthing region: even though other animals occur as well, horses and dogs occur more frequently than others, and cats are interpreted as having a ritual status at Oseberg. It is probably no coincidence that these species are the same as those mentioned in the Borgarthing Law. In central Norway/the Frostathing province, the records for late Iron Age graves in the municipalities Frosta, Snåsa, Rissa, Tingvoll, and Rauma have been searched, particularly for animal bones. No dog bones have been found, and a horse cranium has been observed only in two graves, one in Snåsa and one at Frosta.34 Besides, in two Viking Age barrows at Oppdal, two horses have been found in each cremation. The horses were not cremated but may have been consumed at a sacrificial meal associated with the funeral and the bones added to the grave after the cremation.35 To further investigate the absence of dog bones in the Frostathing province, we carried out a general search in the Vitenskapsmuseet – arkeologisk hovedkata­ log online for dogs and horses in this region. 36 It turned out that dog bones have been found in only a few graves from the Late Iron Age, at the edge of the region: two at Ørlandet and two in Brønnøy,37 but horse bones, and teeth in particular, have been found at other places in addition to those mentioned above. This investigation confirmed the impression of a distinct difference between the province of Borgarthing and that of Frostathing concerning the ritual status of dogs, but it also seems that horses were of lesser ritual importance in the Frostathing province. 32 Ingstad, ‘The Interpretation of the Oseberg-Find’. Nicolaysen, Langskibet fra Gokstad ved Sandefjord, p. 52. 34 Nordeide, The Viking Age as a Period of Religious Transformation. 35 Farbregd, ‘Menn, kvinner, graver og status’; Hufthammer, ‘Bein av mennesker og dyr’. 36 <http://www.dokpro.uio.no/arkeologi/trondheim/hovedkat.html> [accessed 18 March 2013]. 37 Brønnøy was either at the periphery of, or outside the Frostathing law district. 33 Canonical Observance in Norway in the Middle Ages 53 It is obvious that the dog and the horse were of outstanding importance among mammals in a Norse burial ritual in the Oslofjord region/Borgarthing region at the time when Christianity arrived in Norway, to some extent in contrast to the status of these animals in central Norway/Frostathing region. Skeletal remains of cats have not been observed in the graves, but cats could have been present as a ritual symbol in other ways, as demonstrated by the Oseberg find. It is probably not a coincidence that, in a saga paraphrase, the völva Torbjørg Lislevolve is described as wearing gloves and a cap lined with white fur from a cat. It is obvious from the story about Torbjørg that some regarded her deeds as völva as un-Christian. The saga of Eirik Raude containing the story about Torbjørg was, however, written centuries after Christianization and its details cannot be trusted.38 But it illustrates how cats could be involved in un-Christian behaviour in many ways, even if they were not necessarily eaten. In other parts of Scandinavia and Europe, horses have been found in graves as well. In Hungary, for instance, the hide, including the skull and leg bones of the horse, was usually buried with the deceased with the harness on top of it.39 The people of Lower Saxony occasionally practised ritual burials for dogs and horses, and at the Münster Domplatz was found a grave containing a dog and a horse from the latter part of the ninth century, interpreted as a building sacrifice.40 In contrast, horse offerings were not mentioned and almost never found in archaeological sources among Slavic people. Instead western Slavs had some kind of horse oracles, and parts of horses have been excavated around a kind of stone altar in Starigard/Oldenburg.41 Animal Bones from Non-Sacred Contexts Occupation sites from the Viking period have rarely been found and excavated in Norway, and even less often have bones from these contexts been preserved, analysed, and recorded. But on the basis of the few urban sites selected here, there are clearly differences between ritual sites and occupation sites. Animal bones have been collected by sieving Viking Age occupation layers at Kaupang, 38 Holtsmark, ‘Eirik Raudes Saga’, pp. 284–86. Bartlett, ‘From Paganism to Christianity in Medieval Europe’; Berend, Laszlovsky, and Szakács, ‘The Kingdom of Hungary’. 40 Kroker, ‘Die Siedlung Minmigemaford und die “Domburg”’. 41 Slupecki and Valor, ‘Religions’. 39 Sæbjørg Walaker Nordeide and Jennifer R. McDonald 54 dated c. 800–960/80 (Table 2).42 It should be noted that among mammal bones only one was identified as from the dog family (dog or wolf ), three as horse bones, but between thirty-three and thirty-six as from cats. Bones from pigs dominate the number of bones as food waste from mammals.43 Table 2. Number of bones of various mammals, fish, and birds recorded from occupation layers in Trondheim and Kaupang.* Trondheim is represented by the site Folkebibliotekstomten Phase 1 and 2 (late tenth to early eleventh century) and Kaupang by Site Period 1–3 (800–960/80). Kaupang Trondheim Pig Cattle 303 165 711 4094 Sheep / Goat 111 1621 1 4 Horse 3 5 Cat 36 6 Bear 0 1 Red deer 2 6 Dog Bird 10 58 Fish 605 866 Hare 2 2 Fox Seal / Whale 0 0 5 47 1238 7426 Total * Numbers based on Lie, Dyr i byen (for Trondheim); Bartlett and others, ‘Interpreting the Plant and Animal Remains from Viking-Age Kaupang’ (for Kaupang). The bones from Trondheim date from the embryonic phase of the centre of the urban settlement, that is, from the late tenth century or turn of the millennium.44 It is quite obvious that while dogs and horses dominated the ritual sites, these species are sparse in Viking Age occupation contexts, which are instead completely dominated by other domestic mammals. Similar patterns are observed in Sweden.45 42 Pilø, ‘The Settlement: Extent and Dating’. Bartlett and others, ‘Interpreting the Plant and Animal Remains from Viking-Age Kaupang’. 44 Christopherson and Nordeide, Kaupangen ved Nidelva. 45 Sanmark, Power and Conversion, p. 24. 43 Canonical Observance in Norway in the Middle Ages 55 There is also a difference between Kaupang from the early Viking Age and Trondheim from the late Viking Age concerning pigs: while pigs dominate the former, they have become inferior to cattle, fish, sheep, and goats in the latter. Pork was generally inferior to beef and mutton in medieval Tønsberg, Oslo, and Trondheim.46 It is a general trend in Norway that pork lost its dietary importance relative to other meats in medieval towns, even though there was no legal regulation of pork.47 What caused this collapse in the consumption of pork remains to be explained. A considerable contribution of pork to the diet in the Viking period, and its reduction over time, have been observed elsewhere as well: In Viking-era Haithabu there was a large proportion of pork: pig bones represented 34.2% of the material. At this important site the proportion of horse bones was 0.5%, dog remains 0.7%, and cat remains 1%.48 Also in Sweden pigs were more important by the end of the Viking Age than in later periods: in Swedish towns the consumption of pork and beef decreased relative to mutton, but while cattle retained its status as the most important species for consumption (c. 60–70% of bones from domestic animals), pig remains were reduced from c. 20% to less than 10% from the eleventh to the fourteenth century.49 A similar reduction has not been noticed in England, for instance in Lincoln and York, even though pigs seem to be represented in greater quantities in Denmark and Germany than in England.50 A few horse bones have been found at two high medieval sites in Tønsberg. Quite a few bones have also been found from cats and dogs (or other members of the dog family).51 A horse head has been butchered,52 which — regarding the laws — should be interpreted as a result of starvation or disregard of the law. Bones from cattle and sheep or goats still dominated. Some birds and a lot of fish were naturally eaten as well.53 After 1274/6, no great dietary change 46 The earliest phase at one site in Tønsberg, in Baglergate, seems to be a possible exception to this general rule. 47 Hufthammer, ‘Kosthold hos overklassen og hos vanlige husholdninger’. 48 Herre, ‘Die Haustiere von Haithabu und ihre Bedeutung’; Requate, ‘Die Hauskatze’. 49 Carelli, En kapitalistisk anda, pp. 173–75. 50 O’Connor and Wilkinson, Animal Bones from Flaxengate, Lincoln; O’Connor, Selected Groups of Bones from Skeldergate and Walmgate; O’Connor, Bones from Anglo-Scandinavian Levels at 16–22 Coppergate. 51 Solli, Dyrebein, pp. 262–65. 52 Personal information from Anne Karin Hufthammer, 2007. 53 Solli, Dyrebein, pp. 262–65. Sæbjørg Walaker Nordeide and Jennifer R. McDonald 56 Retther Primo groffkødt winsupenn eller vildebraadh Jtem bysteick, kokøtt eller wildebraadh Jtem hensekødt wildebraad eller ein andnen rett Jtem faarekøt oc gallerey Jtem bagelse och tungher Jtem gaas mett mooszoc salthit wildebraad Jtem hwidt gaasekøt och ein rett smaa huggenn aff kokødt mett kriidder Jtem steicht twngher met kriidder och ein ret bagelsze Jtem sylthe oc kalum Jtem grøtt och steiick Jtem oster oc løff Saa skall vprettis paa fiske dage Primo tør siilld: oc wyn suben Jtem salt torsk: oc bagellse Jtem fersk fisk: oc skadther Jtem karuser oc tørre gedder Jtem sund mager: oc ferske gedder Jtem bagelsse: oc stoffiisk Jtem tørre flynder: oc grødt Jtem stegt rundfiisk oc løff Figure 2. Archbishop Olav Engelbrektsson’s menu for his men at Steinvikholm Castle in the 1530s. Source: Olav Engelbriktssons Rekneskapsbøker, ed. by Seip, p. 1. has been observed in Tønsberg, in spite of the lack of obvious legal restrictions against the consumption of horses and dogs from this time on. This picture is very similar to the diet observed in Trondheim. Horses and dogs are represented by only a few bones but in fact by a few more before the change in legislation than after.54 Dogs were also butchered in Bergen, but it is not known if they fed people or animals.55 The Norwegian archbishop’s seat with his palace was located in Trondheim (Nidaros). One would expect the people here to follow the rules set by Christian laws more carefully than people further from the church and the ecclesiastical elite. This context could serve as a good test case for the penetration of the Christian dietary regulations at the centre of the church in Norway. 54 55 Folkebibliotekstomten Phase 6, 8, and 9. Lie, Dyr i byen. Hufthammer, ‘The Dog Bones from Bryggen’. Canonical Observance in Norway in the Middle Ages 57 100% 80% Birds 60% Fish 40% Mammals 20% 0% 4–6 7–9 10–11 Period Graph 1. The relation in per cent between the number of mammal, fish, and bird bones found in the Archbishop’s Palace, Trondheim. Period 4–6: 1250 (1275)–1532, Period 7–9: 1532–1672, Period 10–11: 1672–1783. After Nordeide, Erkebispegården i Trondheim, p. 312. From the list of courses served by the archbishop in his castle at Steinvikholm in the 1530s, it is clear that he served his men well in all ways (Figure 2). The list of courses demonstrates the correct food: fish on fish days, meat on other days. No horseflesh or meat from cats and dogs is listed on the menu. Beef, mutton, and fowl dominate the list. However, bones from dogs, horses, and cats have been found in the late medieval occupation layers in the palace, and some of this was food debris, although it is likely the cats were used for fur rather than food. In fact, the whole skeleton of a dog was buried by the construction of one of the buildings. This dog was not butchered, but it was skinned before being buried, probably as a building offering some time before the Black Death.56 It may also come as a surprise that there was never a higher proportion of meat compared to fish in the diet than during the period the archbishops resided in the palace, from 1152/3 to 1537. After the Reformation the royal authorities took over the palace, and from the animal bone debris it seems that the king’s Lutheran men were better models for a correct Catholic diet than the inhabitants during the archbishop’s tenure. The relative proportion of ‘white food’, fish and fowl, increased after 1537 and again after 1672 (see Graph 1).57 Dogs and horses 56 Nordeide, Erkebispegården i Trondheim, p. 128. Hufthammer, Utgravningene i Erkebispegården i Trondheim; Nordeide, Erkebispegården i Trondheim. 57 Sæbjørg Walaker Nordeide and Jennifer R. McDonald 58 Graph 2. The relation in per cent between the number of mammal, fish, and bird bones found in Launceston Castle. Period 6 (late thirteenth century), Period 8 (fifteenth century), Period 9 (1500–1650), and Periods 10–11 (1660–1939). Adapted from Albarella and Davis, ‘Mammals and Birds from Launceston Castle, Cornwall’, p. 10. were also found more frequently in the Archbishop’s Palace than in occupation areas in Oslo from the period before 1500, but it is unlikely that this was a sign of starvation in the Archbishop’s Palace. Instead, it may indicate that the dietary regulations concerning the consumption of flesh and fasting were not followed as strictly as they should have been, particularly in the seat of the apostolic successor’s delegate. Compared with Launceston Castle in England, a residence for representatives of the secular social elite, there was an increase in the importance of mammals relative to fish and birds from the late thirteenth century to the twentieth century (Graph 2). This tendency was opposite to the pattern observed in the Archbishop’s Palace in Trondheim. The percentage of fish and birds compared to mammals was also much higher in the secular castle in Launceston than in the Archbishop’s Palace in Trondheim. But in Launceston Castle, horses, dogs, and cats were well represented: horse bones were seven per cent of the material in the period 1500–1650. Much dog flesh was consumed particularly from the thirteenth century and cat flesh from the end of the thirteenth century. Butchery marks were found on cat, dog, and horse bones. The cats were probably only skinned, however.58 Analyses of urban material in England has produced slightly different results: in Lincoln the bone material shows that dogs were kept as true pets, and no butchery marks were found on cat, horse, or dog bones. In York the 58 Albarella and Davis, ‘Mammals and Birds from Launceston Castle, Cornwall’. Canonical Observance in Norway in the Middle Ages 59 consumption of pork increased in the late tenth/early to mid-eleventh century, and low proportions of dog, cat, and horse remains were found here as well. In Viking Age occupation layers in Coppergate, York, horses were butchered and disposed in much the same way as the cattle.59 Even if some variation could be observed between various sites in England, the sites show similar patterns to other sites in England.60 The castle Starigard/Oldenburg in East Holstein was situated on the border between the Germans and the Slavs. This castle switched between Christian and non-Christian occupation several times, but during the period c. 650–1150 the proportion of horse, dog, and cat remains in this castle steadily increased, from 0.2% of the material to 1.7%.61 However, as can be seen from the numbers, these species were never very important in the castle-dwellers’ diet. To sum up: horse and dog remains have been found in late Iron Age graves in the Borgarthing region, and cat bones have been found as well, while horse remains were more rare in similar contexts in the Frostathing region, and dog and cat bones have hardly been observed at all in this region. These species were not of any dietary importance in daily life during the Viking Age and the Middle Ages in Norway, which means that they must have had a particular ritual status in Old Norse religion, whether or not they were consumed. In continental Europe, horses and dogs had a ritual status during the same period, but not necessarily both species and not in the same way. This means that there were regional variations in Norway as well as in other European countries, and some trends were more common across Europe than others. After Christianization, cat, dog, and horse flesh were more common for daily consumption in some daily diets in medieval England than in the similar contemporary contexts in Norway, but for the most part these mammals were not of a significant dietary importance anywhere. A dog’s grave in the Archbishop’s Palace in Trondheim from the high medieval period is difficult to explain in relation to Christian customs, and relatively small proportions of fish in the diet there, compared to norms elsewhere in medieval Europe, indicate that there was a difference between norms and practice even at the ecclesiastical centre of the Nidaros province. The butchering of a horse in early medieval 59 O’Connor and Wilkinson, Animal Bones from Flaxengate, Lincoln, pp. 1–50; O’Connor, Selected Groups of Bones from Skeldergate and Walmgate, pp. 1–55; O’Connor, Bones from AngloScandinavian Levels at 16–22 Coppergate, pp. 137–201. 60 O’Connor, Bones from Anglo-Scandinavian Levels at 16–22 Coppergate, pp. 137–201. 61 Prummel, ‘Haus- und Wildtiere’; Gabriel, ‘Starigard/Oldenburg und seine Historische Topo­graphie’. 60 Sæbjørg Walaker Nordeide and Jennifer R. McDonald Tønsberg may represent one of the few examples of conduct clearly deserving a penalty at the time, but whether this happened is not known to us. Discussion and Conclusion The dietary regulations included in the Norwegian provincial law codes indicate that the compilers possessed a fair knowledge of biblical regulations, as well as a competent understanding of current legal and theological rationale. This is particularly evident from the exceptions which the compilers provided to biblical rules. The similarities between the regulations issued in the Norwegian codes and those issued in Continental, English, and Irish penitentials also support this impression. The prohibition of horseflesh is a particular case in point, and seems to have been a concern not only to the compilers of most of the provincial Norwegian codes, but also compilers of insular and Continental penitentials. As demonstrated by the contemporary archaeological sources, the horse was not an important part of the diet in the Viking Age in Norway, and any prohibition would not represent a great impact on daily life in the society. But the important role of the horse in pre-Christian cultic practices, at least in Norway, is one possible explanation as to why Christians felt the need to forbid the eating of horseflesh. There are, however, some significant differences between the codes from Norway and those issued in England and on the Continent. As has been noted, the Norwegian codes provide more in-depth discussion on the exceptions to the biblical rules. Furthermore, the English and Continental legislation expressly prohibit the consumption of sacrificial food. No similar provision exists among the Norwegian codes. Nevertheless, it has been noted that these provisions do — albeit indirectly — prohibit the consumption of food that has been sacrificed, which unfortunately is difficult to verify by archaeological sources outside obvious ritual sites. Scholars have offered four reasons why dietary regulations were promulgated during the Middle Ages: the eradication of non-Christian practices, biblical tradition, the prevention of pollution, and the prevention of disease. Whether the Norwegian provincial codes were issued for the first reason is debatable. It seems plausible, given the similarity in language and formulation between Norwegian and other contemporary legislation, that the issuance of these regulations may rather have been an attempt to demonstrate allegiance to current legal and theological rationales. Regarding dietary regulation, legislation should thus promote a Christian way of living by holding the local diet to the standards of Christendom as a whole. Canonical Observance in Norway in the Middle Ages 61 However, this could be considered superfluous, since horse, cat, and dog flesh were never important parts of the Norse diet. It is perhaps as likely that Christian legislation and Old Norse society shared an opinion on these species: horses, cats, and dogs were close to people, and too close to be served at the table. Instead, they would be natural companions to the grave. From this point of view the legislation and occurrence in graves of horses, dogs, and cats shared the same cause. There is a difference, however: while the whole dog was found in the graves, the horse was normally only represented by its head, and as demonstrated in the Oppdal case, the horse was probably eaten. Consuming such an animal was possible but normally only in a ritual meal. Similar finds have been observed in other parts of Scandinavia, and ritual feasting has also been verified by archaeological sources in Denmark and Sweden as noted above. The Christian dietary regulations may however also have been issued to prohibit a lingering Old Norse religious practice. The differences observed in the ritual use of horses, dogs, and cats in the Frostathing province compared to the Borgarthing province may explain the less precise prohibition of food in central Norway compared to the specific species mentioned in the Oslofjord region: the horse, and particularly the dog and the cat, seems to have been a smaller problem for Norse worship in the Frostathing province than in the Borgarthing province. Early medieval Norwegian legislation was thus in line with canon law but was also a response to local conditions. The rationale behind the Christian dietary regulation can be seen as part of an effort to eradicate Old Norse religious customs and at the same time pave the way for a Christian way of life. This effort was probably most effective regarding burials: people were denied Norse burials and sacrifices at tumuli, which eliminated the major context for the consumption and sacrifice of the forbidden mammals. It should be noted that neither the first Christian laws nor the revised laws of 1273–76 seemed to have any considerable consequences for the average daily diet with respect to horse and dog flesh. Even if neither of these species was specifically prohibited in these later codes, no increase in their consumption can be observed. One of the major changes in diet of this time was, all the more surprisingly, one which was not regulated in the laws: for some reason, pork lost its former importance as part of the diet, a tendency shared with other parts of Scandinavia and beyond. This fact is hard to explain. But in this matter the diet was now more similar to the diet of Jews and Muslims, who would not eat pork either.62 62 Gade, ‘Hogs (Pigs)’. Sæbjørg Walaker Nordeide and Jennifer R. McDonald 62 The data from the Archbishop’s Palace is notable as well. This suggests that while the population of Norway largely adhered to its written laws, the archbishop’s retinue did not set an example for the rest of the Christian community, at least regarding their diet. One would have expected them to lead by having a higher proportion of fish than others and by avoiding horse and dog flesh more than others. This does not seem to have been the case. The dog burial here is also surprising. Such finds indicate that there was a discrepancy between norms and practice even at the centre of ecclesiastical organization. But it is well known from European palaces that their wealth made possible a greater choice of food, especially in times of crisis, and the church allowed the justification of the diet at feasts, even if held on fish days. The church used the difference between feast and fast to demonstrate the difference between heaven and hell.63 It is also possible that it was not deemed necessary to set an example: Christianity had penetrated sufficiently to the majority of people of the Nidaros province in the high and late medieval period, and it may have been more important to show generosity towards the population. Although there is evidence of dietary regulations being clearly disregarded, the examples of this are few. The dynamics between law and practice should be further explored. For instance, why was there a collapse in the consumption of pork even though its consumption was not restricted by law? On the other hand, why would the law restrict the consumption of horse, dog, and cat flesh if these species were already insignificant in the diet? Did the restriction or setting aside of restrictions mean anything at all? In the case of the species mentioned in this article, it appears not. An interdisciplinary study would be of particular interest if we would know more about the relation between dietary theory and practice. 63 Skaarup and Jacobsen, Middelaldermad, pp. 27–28; Redon, Sabban, and Serventi, The Medieval Kitchen, p. 8. Canonical Observance in Norway in the Middle Ages 63 Works Cited Manuscripts and Archival Documents Oslo, Kulturhistorisk museum, Universitetet i Oslo, Museum catalogue no. C22441 Primary Sources Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Aemilius Friedberg, 2 vols (Graz: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, 1959) Nyere norske kristenretter (ca. 1260–1263): Thorleif Dahls kulturbibliotek, trans. by Bjørg Dale Spørck (Oslo: Aschehoug, 2009) Olav Engelbriktssons Rekneskapsbøker, 1532–1538, ed. by Jens Arup Seip (Oslo: Noregs Riksarkiv, 1936) Theodor of Canterbury, The Penitential of Theodore of Canterbury (668–90) <http://ldysinger. stjohnsem.edu/@texts/0680_theod-cant/00a_start.htm> [accessed 26 June 2012] Willibald, Briefe: Willibalds Leben des Bonifatius; Nebst einigen zeitgenössischen Doku­ menten, ed. by Reinhold Rau, Ausgewählte Quellen zur deutschen Geschichte des Mittelalters, 4 (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1968) Secondary Studies Albarella, Umberto, and Simon J. M. Davis, ‘Mammals and Birds from Launceston Castle, Cornwall: Decline in Status and the Rise of Agriculture’, Circaea, 12 (1996), 1–156 Bagge, Sverre, ‘Elsa Sjöholm: Sveriges medeltidslager; Europeisk rättstradition i politisk omvandling, Lund 1988’, Historisk tidsskrift utgitt av den norske historiske forening, 68 (1989), 500–07 Barrett, James, and others, ‘Interpreting the Plant and Animal Remains from Viking-Age Kaupang’, in Kaupang in Skiringssal, ed. by Dagfinn Skre, Kaupang Excavation Project Publication Series, 1 (Oslo: Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 2007), pp. 283–319 Bartlett, Robert, ‘From Paganism to Christianity in Medieval Europe’, in Christianization and the Rise of Christian Monarchy: Scandinavia, Central Europe and Rus’, c. 900–1200, ed. by Nora Berend (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), pp. 47–72 Berend, Nora, József Laszlovszky, and Bela Zsolt Szakács, ‘The Kingdom of Hungary’, in Christianization and the Rise of Christian Monarchy: Scandinavia, Central Europe and Rus’, c. 900–1200, ed. by Nora Berend (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), pp. 319–68 Brink, Stefan, ‘Law and Legal Customs in Viking Age Scandinavia’, in The Scandinavians from the Vendel Period to the Tenth Century, ed. by Judith Jesch, Studies in Historical Archaeoethnology, 5 (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2002), pp. 87–127 Carelli, Peter, En kapitalistisk anda: kulturella förändringar i 1100-talets Danmark, Lund Studies in Medieval Archaeology, 26 (Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 2001) Christophersen, Axel, and Sæbjørg Walaker Nordeide, Kaupangen ved Nidelva, Riksantik­ varens Skrifter, 7, 2 vols (Trondheim: Riksantikvaren, 1994) 64 Sæbjørg Walaker Nordeide and Jennifer R. McDonald Douglas, Mary, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (New York: Praeger, 1966) Farbregd, Oddmunn, ‘Menn, kvinner, graver og status’, Bøgda vår, 15 (1993), 67–80 Gabriel, Ingo, ‘Starigard/Oldenburg und seine Historische Topographie’, in Starigard/ Olden­burg: ein Slawischer Herrschersitz des frühen Mittelalters in Ostholstein, ed. by Michael Müller-Wille (Neumünster: Wachholtz, 1991), pp. 73–84 Gade, Daniel W., ‘Hogs (Pigs)’, in The Cambridge World History of Food, ed. by Kenneth F. Kiple and Kriemhild Coneè Ornelas (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), pp. 536–42 —— , ‘Horses’, in The Cambridge World History of Food, ed. by Kenneth F. Kiple and Kriem­ hild Coneè Ornelas (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), pp. 542–45 Gjerpe, Lars Erik, ed., E18-prosjektet Vestfold, 4 vols (Oslo: Kulturhistoriskmuseum, Fornminneseksjonen, Universitetet i Oslo, 2005–08) Herre, Wolf, ‘Die Haustiere von Haithabu und ihre Bedeutung’, in Die Haustiere von Hait­habu, ed. by Wolf Herre (Neumünster: Wachholtz, 1960), pp. 9–17 Holtsmark, Anne, ‘Eirik Raudes Saga’, in Islandske Ættesagaer, ed. by Hallvard Lie (Oslo: Aschehoug, 1953), pp. 275–301 Hufthammer, Anne Karin, ‘Bein av mennesker og dyr’, Bøgda vår, 15 (1993), 81–83 —— , ‘The Dog Bones from Bryggen’, in The Bryggen Papers: Supplementary Series (Bergen: Universitetsforlaget, 1994), pp. 233–37 —— , ‘Kosthold hos overklassen og hos vanlige husholdninger i middelalderen: en sammenligning mellom animalosteologisk materiale fra Trondheim og Oslo’, in Osteologisk materiale som historisk kilde, ed. by Audun Dybdal, Skrifter, 11 (Trond­ heim: Senter for middelalderstudier, 2000), pp. 163–87 —— , Utgravningene i Erkebispegården i Trondheim: kosthold og erverv i Erkebispegården. En osteologisk analyse, Norsk institutt for kulturminneforskning temahefte, 17 (Trond­ heim: Norsk institutt for kulturminneforskning, 1999) Ingstad, Anne Stine, ‘The Interpretation of the Oseberg-Find’, in The Ship as Symbol in Prehistoric and Medieval Scandinavia, ed. by Ole Crumlin-Pedersen and Birgitte Munch Thye, Publications from the National Museum, Studies in Archaeology & History (København: Nationalmuseet, 1995) Kroker, Martin, ‘Die Siedlung Minmigernaford und die “Domburg” im 9. und 10. Jahr­ hundert’, in 805: Liudger Wird Bischof, Spuren Eines Heiligen Zwischen York, Rom und Münster, ed. by Gabriele Isenberg and Barbara Rommé (Mainz: Zabern, 2005), pp. 229–42 Lie, Rolf W., Dyr i byen: en osteologisk analyse, Meddelelser fra prosjektet Fortiden i Trond­ heim bygrunn: Folkebibliotekstomten, 18 (Trondheim: Riksantikvaren, 1989) Mansrud, Anja, ‘Dyrebein i Graver – En kilde til jernalderens kult og forestillingsverden’, in Mellom himmel og jord: foredrag fra et seminar om religionsarkeologi Isegran 31. Januar–2. Februar 2002, ed. by Lotte Hedeager, Oslo Archeological Series (Oslo: Institutt for arkeologi, kunsthistorie og konservering, Universitetet i Oslo, 2004), pp. 82–112 Canonical Observance in Norway in the Middle Ages 65 —— , ‘Dyret i jernalderens forestillingsverden: En studie av forholdet mellom dyr og mennesker i nordisk jernalder, med utgangspunkt i dyrebein fra graver’ (unpublished master’s thesis, Universitetet i Oslo, 2004) Meens, R., ‘Pollution in the Early Middle Ages: The Case of the Food Regulations in Penitentials’, Early Medieval Europe, 4 (1995), 3–19 Nicolaysen, Nicolay, Langskibet fra Gokstad ved Sandefjord (Oslo: Cammermeyer, 1882) Nordeide, Sæbjørg Walaker, Erkebispegården i Trondheim: Beste tomta i by’n (Trondheim: Norsk institutt for kulturminneforskning, 2003) —— , The Viking Age as a Period of Religious Transformation: The Christianization of Nor­way from ad 560–1150/1200, Studies in Viking and Medieval Scandinavia, 2 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2011) Nordmann, Ann-Marie, De arkeologiske undersøkelsene i Storgaten 18 og Conradis Gate 5/7, Tønsberg 1987 Og 1988, Arkaeologisker rapporter fra Tønsberg, 1, 2 vols (Tønsberg: Riksantikvaren, Utgravningskontoret for Tønsberg, 1989) Norseng, Per, ‘Law Codes as a Source for Nordic History in the Early Middle Ages’, Scandinavian Journal of History, 16 (1991), 137–66 O’Connor, Terry P., Bones from Anglo-Scandinavian Levels at 16–22 Coppergate, in The Animal Bones, ed. by Peter Addyman, The Archaeology of York, 15. 3 (York: York Archaeological Trust, 1989) —— , Selected Groups of Bones from Skeldergate and Walmgate, in The Animal Bones, ed. by Peter Addyman, The Archaeology of York, 15. 1 (York: York Archaeological Trust, 1984) O’Connor, Terry P., and M. Wilkinson, Animal Bones from Flaxengate, Lincoln, c. 870–1500, The Archaeology of Lincoln, 18. 1 (London: Council for British Archaeo­logy for Lincoln Archaeological Trust, 1982) Pilø, Lars, ‘The Settlement: Extent and Dating’, in Kaupang in Skiringssal, ed. by Dagfinn Skre, Kaupang Excavation Project Publication Series (Oslo: Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 2007), pp. 161–78 Prummel, Wietske, ‘Haus- und Wildtiere’, in Starigard/Oldenburg: ein Slawischer Herrschersitz des frühen Mittelalters in Ostholstein, ed. by Michael Müller-Wille (Neumünster: Wachholtz, 1991), pp. 299–306 Redon, Odile, Francoise Sabban, and Silvano Serventi, The Medieval Kitchen: Recipes from France and Italy, trans. by Edward Schneider (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998) Requate, Horst, ‘Die Hauskatze’, in Die Haustiere von Haithabu, ed. by Wolf Herre (Neu­ münster: Wachholtz, 1960), pp. 131–35 Rindal, Magnus, ‘Liv og død i kyrkjas lover: Dei eldste norske kristenrettane’, in Fra hedendom til kristendom: perspektiver på religionsskiftet i Norge, ed. by Magnus Rindal (Oslo: Gyldendal, 1996), pp. 141–49 Sælebakke, Inger, ‘Beskrivelse og analyser av de menneskelige skjelettfunn fra 4 jernalders­ graver i Tønsberg: En rapport’, in De arkeologiske undersøkelsene i Storgaten 18 og Conradis Gate 5/7, Tønsberg 1987 Og 1988, Arkeologiske rapporter fra Tønsberg, 1, 2 vols (Tønsberg: Riksantikvaren, 1990), Appendix 3 66 Sæbjørg Walaker Nordeide and Jennifer R. McDonald Sanmark, Alexandra, Power and Conversion: A Comparative Study of Christianization in Scandinavia (Uppsala: Uppsala universitet, 2004) Shetelig, Haakon, ‘Graven’, in Osebergfundet, ed. by Anton Wihelm Brøgger, Hjalmar Falk, and Haakon Shetelig, 4 vols (Christiania: Universitetets Oldsaksamling, 1917–27), i, 209–78 Sjöholm, Elsa, Sveriges medeltidslagar: Europeisk rättstradition i politisk omvandling, Skrifter utgivna av Institutet för rättshistorisk forskning, 1st ser., Rättshistoriskt bib­ lio­tek, 41 (Stockholm: Nordiska bokhandeln, 1988) —— , ‘Sweden’s Medieval Laws: European Legal Tradition — Political Chance’, Scan­ dinavian Journal of History, 15 (1990), 65–87 Skaarup, Bi, and Henrik Jacobsen, Middelaldermad: kulturhistorie, kilder og 99 opskrifter (København: Gyldendal, 1999) Slupecki, Leszek, and Magdalena Valor, ‘Religions’, in The Archaeology of Medieval Europe: Eighth to Twelfth Centuries ad, ed. by James Graham-Campbell and Magdalena Valor, Acta Jutlandica, Humanities Series (Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 2007), pp. 366–419 Solli, Brit, Dyrebein, Varia, 18 (Oslo: Universitetets Oldsaksamling, 1988) Stylegar, Frans-Arne, ‘The Kaupang Cemeteries Revisited’, in Kaupang in Skiringssal, ed. by Dagfinn Skre, Kaupang Excavation Project Publication Series (Oslo: Aarhus Uni­ versitetsforlag, 2007), pp. 65–126 Wine and Beer in Medieval Scandinavia Lars Bisgaard T his article examines the religious functions of wine and beer in medieval Scandinavia. From ancient times, beer had been part of religious practice in Scandinavia. This changed with the arrival of Christianity, wine then being given superiority. Nonetheless, even in the High Middle Ages evidence exists that beer was used for baptism in Norway and that Swedes used more water than wine in the Eucharist — habits that the papacy strongly rebuked. The best evidence on the use of beer stems from the popular guilds. In their communal feasting several rituals took place. The most important was the remembrance of deceased brothers, which was incorporated into the anniversary performed in the church. The structure of this ritual is examined using material from most Nordic countries. Drinking horns and beer played a central role. A certain similarity with the Last Supper seems to be at stake and in that sense beer played the same role within the guilds as wine in the church. No doubt, the ritual had the character of a lay sacrament. Introduction The Christianization process in Scandinavia entered a crucial period after the time of Charlemagne and is symbolized in the mission of St Ansgar following the baptism of the Danish king Harald Klak (826). Unfortunately, we have little knowledge of the following century and a half, although the process seems to have suffered some setbacks during this period. Then suddenly, out of nowhere, in the second half of the tenth century, the Danish king Harald Bluetooth proclaimed on the large runic stone in Jelling to have Christianized Lars Bisgaard (bisgaard@sdu.dk) is Associate Professor at Syddansk Universitet, Odense. Medieval Christianity in the North: New Studies, ed. by Kirsi Salonen, Kurt Villads Jensen, and Torstein Jørgensen, AS 1 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013) pp. 67–87 BREPOLS PUBLISHERS 10.1484/M.AS-EB.1.100812 68 Lars Bisgaard Denmark. Christian activity during subsequent years is easily traceable all over southern Scandinavia. Churches were built, runic stones with Christian inscriptions erected, and the first national Scandinavian saint, King Olav of Norway (d. 1030), was proclaimed. All three Scandinavian kingdoms — Sweden, Norway, and Denmark — had their own church provinces established during the twelfth century. But the three kingdoms had one problem in common: wine production was not possible because of the cold climate, and yet wine was central to Christian rites. Nor does it seem that ordinary men had much experience of drinking wine, which was exclusively used by the upper strata of society, particularly at larger feasts at the king’s hall. In short, the culture of wine was unfamiliar to the Nordic people. The consumption and religious use of alcohol were familiar, but that alcohol was always beer. The earlier use of beer as a religious drink seems to have caused some trouble for the introduction of the Christian liturgy in medieval Scandinavia, as will be argued below, but in the long run, the victory of wine was evident. The aim of this article is to follow this transformation more closely: did the defeated beverage, beer, find a new place in the hierarchy? Did it lose all ceremonial and religious prestige? The questions are easier to pose than to answer. One way to answer them is to examine the usage of drinking horns, especially among the guilds. These drinking vessels played a vital role in the ceremonies of the guilds and, in general, beer was unquestionably the liquid they contained. Guild statutes have survived very differently in the Nordic countries. Norway has only two, Sweden more than a dozen, and Denmark more than a hundred.1 This varying survival pattern is explained by the heavier urbanization of Denmark from the High Middle Ages onwards by comparison to Norway or Sweden. However, it is important to stress that guilds existed in the countryside as well as in towns. Unfortunately, we know less about the rural guilds, because their statutes were transmitted orally rather than in writing. The Early Years Upon his return from the Holy Land, the Norwegian king Sigurd Jorsalfar arrived at Constantinople in the year 1110.2 According to the English chroni1 The most recent work on the guilds of Scandinavia is Anz, Gilden im mittelalterlichen Skandinavien. Anz does not distinguish between guilds, craft guilds, and confraternities. 2 The following is based on Hiestand, ‘Skandinavische Kreuzfahrer, Griechischer Wein und eine Leichenöffnung’. Wine and Beer in Medieval Scandinavia 69 cler William of Malmesbury, Sigurd was concerned about the widespread illness among his men. The king had his own ideas about the negative effects of the climate, not to mention the Mediterranean food and drink, and he blamed the local Greek wine above all for having caused the trouble. To prove his case he undertook an experiment. A pig’s liver was placed in pure Greek wine and everybody watching it could see how it soon began to dissolve. The king’s suspicion was thus nourished. But he did not stop there: instead, he ordered a human liver to be taken from a dead body and placed in the wine as well. This too dissolved, and all doubts were dispelled: the wine was indeed a dangerous drink.3 This episode has been renowned as the first known medieval dissection. 4 However, it is also one of the few known cases demonstrating the Scandinavian unfamiliarity with wine. In general, the reputation of Greek wine was low at this time, and one could not deny that in highlighting this story, William of Malmesbury wanted to entertain his audience by striking a familiar chord.5 Even so, the fact remained: those used to beer, with its low alcohol content, adjusted with difficulty to wine, which was much stronger. Few comparable illustrations of the Scandinavian attitude survive, which makes this story all the more valuable. Sigurd’s men had easy access to wine during their journey to the Holy Land. At home, the case was different. Transit from wine-growing regions was long and unreliable, and the long winter would halt trade from around November to May. We do not know how wine was procured for the Norwegian churches, but it is generally accepted that it must have been purchased by the cathedrals and distributed from there to the smaller churches. Nor is it clear whether there was a specific ecclesiastical distribution system for wine or whether the cathedrals were left to rely on merchant supplies.6 3 Saxo Grammaticus describes a similar warning. In 1103 the Danish king Eric Ejegod had begun a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, which also brought him to Miklagard, as Constantinople was called by the Scandinavians. Danish soldiers from the emperor’s guard were called to his ship, so the King could speak to them. He warned them among other things of the wine, which he found incompatible with the duties of a soldier. However, the warning was given in general terms and Greek wine is not mentioned. Saxo Grammaticus, Gesta Danorum, ed. by FriisJensen, xii. 7. 2. 4 Grøn, ‘Lot Sigurd Jorsalfar en av sine menn abducere i Bysans’. 5 Hiestand, ‘Skandinavische Kreuzfahrer, Griechischer Wein und eine Leichenöffnung’, p. 145, gives several references on the bad reputation of Greek wine in the West. 6 A modern survey goes no further than to say that the continual spread of Christianity was an important factor behind the growing trading activity throughout northwestern Europe in the eleventh century. Hunt and Murray, A History of Business in Medieval Europe, pp. 12–14. Lars Bisgaard 70 Papal letters sent to Sweden and Norway in the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries seem to refer to some difficulties in wine provision. In 1171–72 Pope Alexander III wrote to the Swedish bishops and admonished them not to spare wine in the Eucharist.7 The background for this admonition is not known but scarcity of wine seems to be the obvious reason. In cases of shortage the pope usually referred to the two natures of Christ — human and divine — arguing that pure wine represented the divine nature only, so adding water, the symbol of man, would solve the shortage problem.8 This had been the practice for several centuries and known from the missionary years in the Germanic lands as well. Everybody agreed that wine and water could be mixed. The disputed point was the exact amount of water that clergymen were allowed to add without undermining the sanctity of the Holy Communion. In 1220 Pope Honorius III rebuked the archbishop of Uppsala for not having stopped the practice of adding more water than wine in the sacrament in his province. This prohibition later entered the collection of canon law. 9 No further letters have survived on the matter between Rome and Sweden. Belonging to the southern part of Scandinavia, the kingdom of Denmark seems not to have had the same difficulties in obtaining wine. Reproving papal letters from the late eleventh century on the general behaviour of the laity in the province do not mention any problems relating to the Mass.10 One could argue that as long as Scandinavia was part of the province of Hamburg-Bremen, which was the case until 1103–04, German wine would probably flow regularly to the region through ecclesiastical channels. Raising each of the Nordic kingdoms to ecclesiastical provinces in the twelfth century meant that new means of wine provision were to be established. The many international relations of the strong Danish monarchy under Valdemar I, Canute VI, and Valdemar II (1157–1241), combined with its proximity to the Netherlands and the Rhine region made Denmark more successful in that task than Sweden or Norway. Norway seems to have been the country that suffered most from the scarcity of wine. In 1237 the archbishop of Nidaros, Sigurd Eindridesson (r. 1231–52), tried to convince Pope Gregory IX (r. 1227–41) that his most northern fron7 Gallén, ‘Eucharisti’. The letter is printed in Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, i, no. 56. 8 Härdelin, Aqua et vina mysterium. 9 Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Friedberg and Richter, ii: Decretalium collectiones, x 3.41.13 (col. 643). Gallén, ‘Eucharisti’; Härdelin, Aqua et vina mysterium, p. 76. 10 Diplomatarium Danicum, ed. by Afzelius and others, ii (1963), nos 7, 8, 11, 13, 17, 19, and 20. Wine and Beer in Medieval Scandinavia 71 tier needed special assistance because wheat and wine could not be produced locally. He even suggested replacing wine in the sacrament with beer or some other liquid.11 But the pope did not agree. The province of Nidaros, which consisted of Norway, Greenland, Iceland, and other North Atlantic islands, had to follow the same rules as all other Christian territories. The reference to beer in the letter to Pope Gregory IX is especially noteworthy. Although shortage of wine had been put forward as the reason, the mention of beer recalls the use of that drink in heathen religious practice. Another argument for this is that, a few years later in 1241, Gregory IX condemned baptism in beer instead of water, propter aque penuriam.12 In an earlier letter from 1206, Innocent III (r. 1198–1216) had instructed the archbishop of Nidaros not to allow the baptism of sick children by striking their head, their breast, and between their shoulders with saliva. Beer is not mentioned in the letter.13 No papal letter addressed to Denmark or Sweden concerning baptism has survived. During the Germanic missionary period (c. 550–800), the church challenged beer from time to time because it was part of heathen rites. In the Life of the Irish saint Columbanus, who christened the German people around 600, we read that he came to the Swabians at a time when they were preparing a profane sacrifice. In their midst they had a big pot with a large amount of beer (20 modii, i.e. about 180 litres). St Columbanus, we read, approached them and asked what they intended to do. They responded that it was a sacrifice in honour of the god Wotan. Columbanus then blew into the pot and it broke apart with a horrible crash into a thousand pieces and together with the beer out came the evil spirit, for in that pot was hidden the devil who by means of the sacrilegious liquid hoped to possess the souls of those participating in the sacrifice.14 11 Diplomatarium Islandicum, ed. by Jón Sigurðsson and others, i: 834–1264, ed. by Jón Sigurðsson, no. 131. 12 Diplomatarium Norvegicum, ed. by Lange and others, i, no. 26. ‘Cum, sicut ex tua relatione didicimus, nonnunquam propter aque penuriam infantes terre tue contingat in cervisia baptizari, tibi tenore presentium respondemus, quod cum secundum doctrinam evangelicam oporteat eos ex aqua et spiritu sancto renasci, non debent reputari rite baptizati, qui in cervisia baptizantur’. 13 Diplomatarium Norvegicum, ed. by Lange and others, vi (1864), no. 10, ‘in capud ac pectus et inter scapulas pro baptismo saliue’. 14 Montanari, The Culture of Food, p. 19. St Columbanus would have been acquainted with beer in his homeland in Ireland. Lars Bisgaard 72 St Columbanus did not consider beer itself as demonic. What mattered was how and for what the liquid was used. In the monastery of Luxeuil, founded by Columbanus, a monk had forgotten to close a tap in a barrel of beer in the cellars. When he remembered he hurried back only to find that not a drop had been lost, thanks to the saint’s intervention.15 The conclusion is that beer intended for good purposes ought to be saved. This is supported by a miracle from the saint’s Life where he multiplied loaves and beer to feed a mass of hungry people. There was nothing inherently pagan about beer: it was simply a healthy drink as long as it had not been consecrated for ritual purposes. The situation was quite different in the twelfth century. Widespread Gregorian reforms had laid the foundation for a self-confident church which strove for a new uniformity in liturgy, sacraments, and chant. For the vigorous popes of the early thirteenth century, there was no longer any place for different habits in central sacraments such as baptism and the Eucharist. Consequently, the Old Norwegian church laws which had permitted the use of liquids other than water in case of an emergency baptism were no longer valid. Beer was denied to be a part of Christian ceremonies. But was this denial accepted by the Scandinavian laity? Drinking Vessels In 1909 Jørgen Olrik from the Danish National Museum published a large catalogue of the many medieval drinking horns in its collection. Half of them had Danish origins; the other half came from Iceland and Norway.16 Olrik presented the horns as unique to the Nordic kingdoms, although he did not deny their Germanic origin. Denmark’s relationship to Germany became strained after her loss of sovereignty over the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein in a war with Prussia and Austria which ended in 1864. For nationalist reasons, then, it seems, Olrik insisted that Germans had given up drinking from horns at a much earlier stage than the Scandinavians.17 Olrik even claimed that drinking horns had been part of Danish culture ever since the Iron Age. However, the chronological diffusion of the surviving vessels did not show the continuity for which Olrik argued. Only a few horns had survived from the Viking Age and none from the early High Middle Ages 15 Montanari, The Culture of Food, p. 19. Norway had been ruled by the Danish king from 1397–1814. Iceland freed itself in 1944. 17 Olrik, Drikkehorn og Sølvtøj fra Middelalder og Renaissance, pp. 1–2. 16 Wine and Beer in Medieval Scandinavia 73 Figure 3. Danish medieval drinking horn, from the guild of the Holy Trinity in Flensburg. Photo: Städtisches Museum, Flensburg. (c. 1000–1200). Olrik solved the problem of the missing horns by reference to the regular mentions of horns in medieval ballads and folk songs — although we now know that the texts date from the sixteenth century. Of their function Olrik wrote: ‘These horns, many of a substantial volume […] are very likely intended for being passed around from hand to hand between the drinking brethren, so each of them could take a gulp from them’.18 This explanation has been refuted in recent years,19 but it was picked up by popular culture, where it is still often met. Olrik seems to have missed the point that most of the drinking horns had religious inscriptions: a prayer for the Virgin Mary, the name of a saint, or even rhymed sentences. Ellen Marie Magerøy, who has published extensively on Icelandic drinking horns, has found among them many decorated examples with scenes from the Bible or with portraits of saintly figures. Such ornamentation indicates that their original function was religious. Compared to the number of surviving drinking horns, many more are found mentioned in medieval written sources. Examining the material from Iceland and Denmark, we find that most of the horns belonged to ecclesiastical institutions or clergymen. Inventory lists from Iceland inform us that the monas18 19 Olrik, Drikkehorn og Sølvtøj fra Middelalder og Renaissance, p. 1. Bisgaard, ‘Gilder og drikkehorn i middelalderen’; Magerøy, Islandsk hornskrud. Lars Bisgaard 74 tery of Videy possessed five horns in 1367, the cathedral of Hólar had thirteen horns in 1374, and that of Skálholt owned eighteen examples in 1548.20 Similar lists from Denmark have not survived but horns mentioned in wills demonstrate their popularity in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries: fortyeight horns figure in thirty-two last wills in the period between 1285 and 1459. Only four of them belonged to secular persons. The rest — more than ninety per cent — were in the possession of abbots, bishops, other prelates, and parish priests.21 Not only were clerics the predominant possessors of drinking horns, they also passed the horns as gifts to other ecclesiastical figures.22 How can we explain this clerical predominance? Being sceptical, one could argue that we always are better informed about the church than the rest of society. It is true that a disproportionately large amount of the wills come from clerics (more than fifty per cent), but even if this is taken into consideration, there was still an overwhelming predominance of horns among clerics. Therefore the crucial question is to determine the function of the drinking horn. Minne Drinking Several scholars have stressed that horns were part of commemorative drinking.23 The Nordic languages have their own word for this practice, minne. The word comprises several meanings: memory, remembrance, souvenir, toast, and cup. The purpose of minne drinking was the commemoration of the dead. In conservative Iceland minne drinking was also performed at weddings, which is probably why the authorities allowed drinking horns still to be produced after the Reformation.24 Commemoration of the dead played a vital role in medieval religious practice. Perpetual Masses were founded both by clerics and lay people especially from 20 Magerøy, Islandsk hornskrud, p. 115 n. 18. Bisgaard, ‘Gilder og drikkehorn i middelalderen’, p. 82 nn. 5 and 6. 22 Bisgaard, ‘Gilder og drikkehorn i middelalderen’, p. 67. Nine of the forty-eight horns were given to secular persons. 23 Fritzner, Ordbog over Det gamle norske Sprog; Seierstad, ‘Noko um religiøse minnedrikkjer i Noreg etter Reformasjonen’, to mention but a few. 24 Magerøy, Islandsk hornskrud, p. 3; Agnes S. Arnórsdóttir, Property and Virginity, pp. 217–94 and fig. 21. 21 Wine and Beer in Medieval Scandinavia 75 the thirteenth century onwards. Commemorative acts and intercessory prayers were both parts of the Mass at such arrangements which could vary in length and occasion. At least two types of Mass became immensely popular: perpetual obsequies/anniversaries and votive Masses. Anniversaries were repeated Masses for the deceased which took place each year on the day the person to be remembered had passed away. Guilds, crafts guilds, and confraternities also founded anniversaries for their dead members. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries it had become normal to found obsequies to be celebrated two, four, or six times a year.25 Votive Masses, often called chantries, were more expensive as they usually were spoken or sung once a week or even daily, except on Sundays. Several priests participated in the celebration of an anniversary.26 If the perpetual Masses were founded at a monastery, the ordained priests under the rule of the abbot were each expected to celebrate a Mass. At the cathedrals Masses would be sung or spoken both in the choir and in the nave, and the celebrating prelates and vicars would be paid respectively. In parish churches clergymen would attend according to the numbers promised in the written contract. Everywhere the idea was to awaken as many clerics as possible to the good qualities of the dead person or persons to be remembered. Deeply integrated within this system of prayers and commemorative acts in perpetual Masses was the practice of minne drinking. The drink is, however, not mentioned in the founding charters of the Masses. One reason for this was that the church officially had nothing to do with it. Another was that the lay additions to the perpetual Masses probably differed from region to region in the Latin West, and regional customs were in tension with the very core idea of the charters, which was to be part of the unifying code established by the Gregorian reforms of the twelfth century. Guild statutes, however, are quite informative on the matter. Communal feasting and Masses for the dead were constituent elements of a guild from the very beginning.27 They can be traced in the old Danish saint Canute’s guilds from the end of the twelfth century, and their written ordinances are among the oldest we have.28 No special date in the calendar was reserved for communal 25 Bisgaard, De glemte altre, pp. 83–86. Bisgaard, De glemte altre, pp. 92–103 and 295–300. See also Bisgaard, Tjenesteideal og fromhedsideal, pp. 93–98. 27 According to Cooenart, ‘Les Ghildes Medievales’, this can be traced back to the time of Charlemagne. See also Anz, Gilden im mittelalterlichen Skandinavien. 28 The Norwegian guild ordinance from Nidaros, only partially extant, is the oldest. See Anz, Gilden im mittelalterlichen Skandinavien, pp. 83–87. 26 Lars Bisgaard 76 feasting, and the exact dates would depend on the patron saint/saints of the guild, the craft guild, or the confraternity. A certain variety in the organization of the feast cannot be denied. But we must not forget that communal feasting was composed on the very same scheme as the funeral.29 Communal feasting in Nordic languages was everywhere called drik. Its first sequence took place in the evening and consisted of vigils in the church for the dead members of the guild. Shortly thereafter the minne drink began. It is prescribed in many details in the (unfortunately undated) statutes of a Swedish guild dedicated to St George. Three central paragraphs run as follows: Xix Item om tysdagehnn om aptonen tha skal vigiles hollas ok alla gyllesbröder skulo ner vara. Ok om Onstagen siälamesso tha skulo alla brödher offra, Strax epther messone skulo alla brödher ok systrar i gyllestugone stempnas ok allermanom med brödrom ok systrom stempno holla. Xx Om tysdagx aptonen tha skal syäla mynne skänkias tha skal alla brødher ok systrar närvara. Tha högxtha mynne ä skänkth tha skal klokaren bära rökilse och vigdhe vatn brödrom systrom ok ther bör klokaren i öre före aff gilles peningh. Xxi Mynnes kar skola vara ix. Først varss herra mijne. Varffru mynne och sancte Örianss mijne högxtha mynne och thz serdelis skal skiänkias serdeliss mz horn ok handkläde ok gillesbloss ok alla gillesbrödher skulo upsta ok qvädha tha thz mynne skiänkth är, tha skulo gerdenne mz horn handkläde gen qwedandes vtför dörena ok gijffva them fatigom öl som the haffwa i hornen eller kannor. Item lijthen stundh ther epther skulo gerdenne skänkia Helge Kors mynne, ok Sancte Erikz mynne, ok sancte olaffs mynne. Item lijthen stundh ther epther skulo the skiänkia all Gudz helgona mynne, Sancte Gertrud, oc sancte benkth.30 (§19. Likewise on Tuesday evening vigils shall be celebrated and all guild brethren should attend. And on Wednesday at the Masses for the souls all brethren should offer. Immediately after the Masses have finished all brothers and sisters should meet in the guild rooms and the master of the guild with brothers and sisters have its meeting. §20. On Tuesday evening minne for the souls shall be poured and all brothers and sisters be present. When highest minne is poured, the bell ringer shall bring incense and holy water to the brothers and sisters and the bell ringer ought to be paid 1 øre of the guild’s money. 29 30 Bisgaard, De glemte altre, pp. 92–103. Småstycken på forn svenska, ed. by Klemming, pp. 131–32. The translation is author’s. Wine and Beer in Medieval Scandinavia 77 §21. Minne vessels should be nine. First Our Lord’s minne. Our Lady’s minne and the Knight St George’s minne [i.e. highest minne] should in particular be poured in a horn with a piece of cloth and the guild’s torches lit and all guild-brethren should stand up and chant when these minne are poured, and then those who have brewed and prepared the beer should go singing out of the door and give to the poor what beer they have left in the horn or in the pots. Likewise a short while thereafter those who have brewed and prepared the beer should pour the minne of the Holy Cross, St Erik’s mine, and St Olav’s minne. Likewise a short while thereafter those who have brewed and prepared the beer should pour the minne for all God’s saints, St Gertrud and St Benedict.) The drinking horn was used at the most memorable of the nine toasts, namely that for the patron saint of the guild of St George. The torches would be lit, the brothers would sing, and what they could not drink was given to poor people outside the doors of the guild rooms.31 All this would happen in close connection with the parish church. Here the ritual would begin with vigils, and the Masses for the soul would be celebrated early the following morning with as many officiating priests as possible. In the lay sequence the bell ringer would bring incense and consecrated water from the parish church to bestow the requisite solemnity of this important moment in the guild’s religious activity. Minne drinking was indeed holy. Other paragraphs in the guild’s ordinance tell how the beer to be drunk had been specially brewed and cared for. The task of brewing that beer was passed around among the guild members. The Nordic word for brewing and serving that beer was gerd (mentioned in § 21 above). This word is common in the Nordic guild statutes, whether from craft guilds or ordinary guilds. The word gerd is often met in the guild statutes, while minne occurs only rarely. After the Swedish guild ordinances, where the word appears the most, it is only found in the Norwegian statutes for the Onarheim guild, which dates from the second half of the thirteenth century, and in three Danish guild statutes,32 the oldest of which are the 1266 Latin statutes for St Erik’s guild in Kallehave. Unlike the practice in the Swedish St George’s guild, the Danes in Kallehave restricted themselves to three drinks only, one for St Erik, one 31 For a more detailed survey of the importance of the poor, see Bisgaard, De glemte altre, chaps 2 and 6. 32 Anz, Gilden im mittelalterlichen Skandinavien, pp. 87–97. Lars Bisgaard 78 Figure 4. Statutes of the cooper’s guild, Malmö, 1503. Photo: Malmö Stadsarkiv. Wine and Beer in Medieval Scandinavia 79 for Our Lord, and one for the Holy Virgin.33 So did the smiths in the cathedral town of Roskilde more than two hundred years later in 1491. They sang and drank for their patron St Eligius, for Our Lady, and for the Holy Trinity.34 The Hellested statutes from 1404 do not explicitly mention whom they sent their prayers to but include an instructive Latin verse comment on the minne drinking:35 The living brothers call on their beloved dead The Psalm will remember the brothers passed away Now the names of the deceased will be read Whose souls at the seat of the heavenly King will stay.36 Especially in the otherwise rich Danish material, where 122 different statutes are preserved,37 the rarity of the word minne is striking. The obvious reason seems to be that ‘drik’ (anniversaries) were sufficient and accurate words to describe what went on. The Latin verse in Hellested supports this. If that is true, the fusion of popular tradition and Christian liturgy had become complete in the later Middle Ages. The Priest Guilds So far we have met the drinking horns as indispensable requisites in commemorating the dead members of a guild. The horns were highly regarded, as can be seen from the statutes of the guilds as well. For example, in the ordinance of the Danish guild in Uggerløse, dating from the second half of the fourteenth century, the fine for spilling beer from a horn is five times higher than spilling from a cup.38 Drinking for the dead from a horn embraced the dignity of the guild and took place the first evening. Cups were used instead at the dinner which followed the Masses on the next day and ended the communal feasting. 33 Danmarks Gilde- og Lavsskraaer fra Middelalderen, ed. by Nyrop, i, 66, § 42. Minne is untranslated in the Latin text. 34 Danmarks Gilde- og Lavsskraaer fra Middelalderen, ed. by Nyrop, ii, 209, § 30. 35 Danmarks Gilde- og Lavsskraaer fra Middelalderen, ed. by Nyrop, i, 172, §§ 11 and 13. 36 ‘Fratrum viuorum recitentur nomina [a]morum | Psalmus defunctorum memor esto quisque suorum | Nunc defunctorum recitentur nomina, quorum | Pneumata celorum rex seruet in ede polorum’. Danmarks Gilde- og Lavsskraaer fra Middelalderen, ed. by Nyrop, i, 176. 37 Bisgaard, De glemte altre, p. 32. 38 Danmarks Gilde- og Lavsskraaer fra Middelalderen, ed. by Nyrop, i, 105, § 37. Lars Bisgaard 80 However, no explanation has yet been given for the preponderance of horns among clerics. Half of the surviving Danish drinking horns belonging to guilds come from priest guilds, which blossomed in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Their idea was to assemble as many priests as possible to make the perpetual anniversaries even more attractive. Thus the communal feasts at priest guilds, however odd it may sound, became meeting places between laypeople and clerics.39 Commemorative drinking was on the agenda here as well. Here, unlike in ordinary guilds, it signalled piety and efficiency. Firstly, the programme for communal feasting at priest guild involved more religious acts than in ordinary guilds. Secondly, the perpetual Masses on the second day would grow in numbers because of the many priests in the guild.40 The idea of the priest guilds came from the Hanseatic towns of northern Germany and reached the duchies of southern Jutland during the first half of the fourteenth century. The first known Danish ordinance from a priest guild dates from 1362.41 The Holy Trinity guild was founded in Flensburg, a prosperous town by the sea in the duchy of Schleswig. From this guild two drinking horns have survived, confiscated at the time of the Reformation by the Protestant magistrates, to whom the commemoration of the dead was illicit, and locked away in the city hall.42 From inventory lists we know that the guild at that time owned four horns. All of them were presents from members of the guild. The larger of the two surviving horns was given to the guild by the bishop of Ribe around 1400, the smaller one by a vicar from Flensburg about a hundred years later.43 Priest guilds like the one in Flensburg spread all over Denmark. By chance, we know that priest guilds had been founded in each of the towns on the island of Fyn before the Reformation in 1536.44 Priest guilds in Norway or Sweden have not been the subject of a close study, and so their history remains unknown. In Denmark, where we have more information, the largest and most influential priest guilds were established in the cathedral cities. Many of them grew 39 Bisgaard, ‘Det middelalderlige kalente’. The priest guild in Kiel dates from 1337. Bisgaard, ‘Det middelalderlige kalente’, p. 451. 41 Danmarks Gilde- og Lavsskraaer fra Middelalderen, ed. by Nyrop, i, 263–300. Its Liber vivorum et liber mortuorum has survived. 42 Danmarks Gilde- og Lavsskraaer fra Middelalderen, ed. by Nyrop, i, 275. 43 Bisgaard, ‘Gilder og drikkehorn i middelalderen’, p. 66. 44 Bisgaard, ‘Guild and Power’. 40 Wine and Beer in Medieval Scandinavia 81 immensely rich and had their own guild houses. The priest guild in Flensburg was rich too, although the town had no cathedral. Their statutes prescribed only Danish beer to be served, when the guild met twice a year with vigils in the evening and Masses in the morning for the dead. However, the assembly beginning on the Sunday after Ascension Day was to last one day longer and contain Masses pro defunctorum in the morning on the third day. All participating priests promised to have the names of the dead and living souls of the lay members in their prayers in the Mass. No gathering after the vigils is mentioned but two large dinners on the second and third day are.45 Plenty of opportunities to chant the honour of the Holy Trinity or Virgin Mary and to ask them to intercede for the dead and living souls would arise. The many drinking horns in the possession of Danish clerics ought to be seen in this context. Drinking horns were necessary items for priests so that they could participate in every sequence of the anniversary ceremonies. The drinking horn had thus become an almost professional tool for clergymen. For example, the bishop of Roskilde donated twelve horns in his last will in 1350.46 This function of the vessels will also explain a strange composition in the last will of a canon at Lund Cathedral written in 1338. One of his dispositions is to found a perpetual anniversary at the cathedral, but then, right in the middle of the text, he gives four drinking horns to four specific canons in Lund.47 What seems to be a break in the flow of an ecclesiastical disposition is actually a very understandable association and reflects the composition of an anniversary. Our focus has been on the guilds because their ordinances offer us good glimpses of the sequences added to the many perpetual Masses in the later Middle Ages. This must not make us forget that the main part of the chantries and about half of the anniversaries were founded by individuals. When examining anniversary charters it becomes clear that they always imply drinking and eating for the soul of the dead. On these occasions horns would also be meaningful requisites to be passed around the celebrants after the Masses for the donor and his family had been spoken or sung.48 45 Danmarks Gilde- og Lavsskraaer fra Middelalderen, ed. by Nyrop, i, 264–65, §§ 3–4. Five or six courses were to be served at the dinner, and expensive German beer could be arranged. 46 Testamenter fra Danmarks Middelalder, ed. by Erslev, no. 45. 47 Testamenter fra Danmarks Middelalder, ed. by Erslev, no. 37. 48 Bisgaard, De glemte altre, pp. 295–300. Lars Bisgaard 82 Wine and Beer Among scholars there are different opinions on how to understand the medieval minne drinking. Magerøy presents it as a direct continuity of the heathen drinking for Odin/Wotan and other gods.49 Andreas Seierstad is not so sure, arguing instead that scholars must distinguish sharply between minne drinking in heathen times, in the Middle Ages, and in the Protestant era. He reserves the term minne drinking for the medieval period alone; before and after, he argues, they used other words to express the ritual of drinking.50 Neither Magerøy nor Seierstad connect minne drinking with the rise of anniversaries from the beginning of the thirteenth century onwards. An anniversary was an old Roman rite where Christians met at the tombs of the martyrs to pray, eat, and drink to them. The new vitality of this tradition is usually presented as a consequence of the doctrine of transubstantiation accepted at Lateran IV in 1215. The crucial question now is how minne drinking and the anniversary ritual intermingled? Thirteenth-century Scandinavia saw a lot of changes, in which the church played a major role. Only a few of them have been treated here: the cleansing of sacraments, such that water became dominant in baptism and wine in the Eucharist; the modernization of guilds after the model of the confraternity;51 the popularity of the anniversary; and the reappearance of drinking horns. All these changes were probably interconnected. It is hard to imagine that the old habit of minne drinking could be unaffected by such extensive and far-reaching change. The very word minne was affected by developments in the German language, where minne came to mean love and harmony, and Minnesang (minne song) grew very popular. The German meaning of the word was more or less what minne drinking was about, seen from the guilds’ perspective.52 The ritual of the anniversary of which minne drinking was part, established precisely that communal spirit which the guild needed to justify its very existence. The structural similarity between an ecclesiastical anniversary and communal feasting within a guild is obvious. Vigils in the evening, Masses in the morning, and a large meal to follow are all common ingredients. On the other 49 Magerøy, Islandsk hornskrud, p. 3. Seierstad, ‘Noko um religiøse minnedrikkjer i Noreg etter Reformasjonen’, reserves the word full for the pagan era and minne for the Christian. 51 Bisgaard, De glemte altre, p. 20. 52 Bisgaard, De glemte altre, pp. 232–36. 50 Wine and Beer in Medieval Scandinavia 83 hand, a major difference can also be noted. It occurs at night after the vigils in the church. Here we know that guilds would meet and celebrate the remembrance of their dead brothers and sisters, either in their guild house or at the house of one of its members, and minne drinking was the central part of this gathering. Hereby is indicated a non-Christian origin. Soon the content of the minne drinking, however, was heavily marked by Christianity, as the different toasts were all drunk to honour the Virgin Mary, a specific saint, or the Holy Trinity, as we saw in the Swedish cases referred to above. Other non-Christian elements included drinking horns and the use of beer. Drinking horns and minne drinking are often presented as two sides of the same question. The story is probably more complicated. Horns erode if hidden in soil and only metal plates used for decorative purposes survive. Neither plates nor intact horns survive from the period 1000–1200. An educated guess would be that clergymen as well as lay people tried to distance themselves from tools directly connected to the old religious practice. An ecclesiastical ban is also a possibility. After 1200 German beer was introduced into Scandinavia and together with it came fashionable drinking horns made of aurochs from the plains of central eastern Europe. The elaborated and decorated horns which have survived are all from this period. Alone their size gave them an advantage in ceremonial settings. From the beginning of the fourteenth century we know they were part of the celebration of perpetual anniversaries. It is not known how they were introduced into the guilds, but presumably this happened alongside their successful appearance in the anniversaries. Beer offers more trouble. The beverage was vital for the region and any general prohibition would be bound to fail. As the Life of St Columbanus showed, cooperation, respect, and adoption soon became part of the church’s dealings with beer. What could not be tolerated was its use in heathen practices. It is unclear how this was translated and interpreted in the missionary years of Scandinavia, but it seems that to some extent, at least in northern Scandinavia, beer was accepted in Christian sacraments. It was banned by the intervention of the popes around 1200. A hundred years later beer had obviously won a permanent and official position in the religious practice relating to funerals and the repeated holding of perpetual anniversaries. The result was a genuinely medieval piece of liturgy. We are best informed of its composition when anniversaries were held by guilds. The gathering after the vigils of the first evening is as close as one could come to a lay sacrament, in which beer was the indispensable element. And yet this was only the prelude to the real sacrament: that is, the Masses next morning, based on the new strong concept of the Eucharist, following 1215. 84 Lars Bisgaard Figure 5. The three magi, one with drinking horn. Fresco in Vesterø church, Denmark, early sixteenth century. Photo: Johannes Christoffersen. The greatness of the Middle Ages is in its conceptual simplicity. The contrast between the drinking horn in the guild rooms and the chalice in the church may seem immense, but viewed in a symbolic way it disappears. The people gathered around the two valuable requisites are part of the same story, which began with the Last Supper. In one of the Danish churches, Vesterø, on the island of Læsø, there is a mural painting showing the Magi’s offerings to Christ as a child. One of the presents given is a drinking horn. The presumed meaning Wine and Beer in Medieval Scandinavia 85 is that it forecasts his death, which was repeated at each Mass as a real sacrifice for mankind, for both living and dead souls. Drinking from the passing horn, the guild brethren — on behalf of their wives, children, and household — would be reminded of that story, their own death, and the death of the sisters and brothers who had died since the last festive gathering in the guild. This was no heathen ritual but a new, very medieval, Christian one. The question is whether communal feasting within the Nordic guilds differed from that within other European guilds. It certainly did not with respect to the ways in which religious tasks were part of the guild structure, nor in how the remembrance of dead guild brethren was part of communal feasting. Scholars such as Christoph Anz, Otto Gerhard Oexle, and Miri Rubin have stressed this.53 More detailed studies on the composition of the drinks in a comparative perspective may give a full answer to that question. So far there is reason to believe that the importance of beer, the dominant role of the drinking horn in lay sacramental behaviour, and components from heathen drinking all contributed to give the anniversary a specific Nordic elaboration. 53 Anz, Gilden im mittelalterlichen Skandinavien; Oexle, ‘Liturgische Memoria und historische Erinnung’; Rubin, ‘Fraternities and Lay Piety in the Later Middle Ages’. 86 Lars Bisgaard Works Cited Primary Sources Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Emil Friedberg and Aemilius Ludwig Richter, 2 vols (Graz: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, 1959) Danmarks Gilde- og Lavsskraaer fra Middelalderen, ed. by Camillus Nyrop, 2 vols (København: Gad, 1895–1904) Diplomatarium Danicum, ed. by Adam Afzelius and others, 36 vols in 4 series (København: Munksgaard, 1938–2000) Diplomatarium Islandicum = Íslenzkt fornbrèfasafn: sem hefir inni að halda brèf og g jörnínga, dóma og máldaga, og aðrar skrár, er snerta Ísland eða íslenzka menn, ed. by Jón Sigurðsson and others, 16 vols (København: Hið íslenzka bókmentafèlag, 1857–1972) Diplomatarium Norvegicum, ed. by Christian C. A. Lange and others, 22 vols (Oslo: Malling, 1849–1995) Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Johan Gustaf Liljegren and others,, 11 vols (Stockholm: Norstedt, 1829–2011) Saxo Grammaticus, Gesta Danorum, ed. by Karsten Friis-Jensen (København: Gad, 2001) Småstycken på forn svenska, ed. by G. E. Klemming (Stockholm: Svenska fornskriftsällskapet, 1868–81) Testamenter fra Danmarks Middelalder indtil 1450, ed. by Kristian Erslev (København: Gyldendal, 1901) Secondary Studies Agnes S. Arnórsdóttir, Property and Virginity: The Christianization of Marriage in Medieval Iceland, 1200–1600 (Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 2009) Anz, Christoph, Gilden im mittelalterlichen Skandinavien, Veröffentlichungen des MaxPlanck-Institut für Geschichte, 129 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1998) Bisgaard, Lars, ‘Gilder og drikkehorn i middelalderen’, Den jyske Historiker, 85 (1999), 62–83 —— , De glemte altre: Gildernes religiøse rolle i senmiddelalderens Danmark (Odense: Syd­ dansk Universitetsforlag, 2001) —— , ‘Guild and Power: A List Commemorating the Dead in Odense’, in Medieval Spirituality in Scandinavia and Europe: A Collection of Essays in Honour of Tore Nyberg, ed. by Lars Bisgaard and others (Odense: Syddansk Universitetsforlag, 2001), pp. 245–65 —— , ‘Det middelalderlige kalente — et bindeled mellem kirke og folk’, in Kirke og kongemagt i senmiddelalderen: de to øvrigheder i dansk middelalder, ed. by Per Ingesman and others (Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 2007), pp. 443–70 —— , Tjenesteideal og fromhedsideal: studier i adelens tankemåde i dansk senmiddelalder (Aarhus: Arosia, 1988) Cooenart, E., ‘Les Ghildes Medievales’, Revue historique, 199 (1948), 22–55 and 208–43 Fritzner, Johan, Ordbog over det gamle norske sprog, 4 vols (Christiania: Møller, 1886–1972) Wine and Beer in Medieval Scandinavia 87 Gallén, Jarl, ‘Eucharisti’, in Kulturhistorisk Leksikon for Nordisk Middelalder, ed. by John Dalstrup and others, 2nd edn, 22 vols (København: Rosenkilde og Bagger, 1956–78), iv: Epistolarium–Frälsebande (1959), p. 58 Grøn, Fredrik, ‘Lot Sigurd Jorsalfar en av sine menn abducere i Bysans’, Norsk Magasin för Lægevidenskaben, 95 (1934), 1405–18 Härdelin, Alf, Aqua et vini mysterium: Geheimnis der Erlösung und Geheimnis der Kirsche im Spiegel der mittelalterlichen Auslegung des gemischen Kelches (Münster: Aschendoff, 1973) Hiestand, Rudolf, ‘Skandinavische Kreuzfahrer, Griechischer Wein und eine Leichen­ öffnung im Jahre 1110’, Würzburger medizinhistorische Mitteilungen, 7 (1987), 143–53 Hunt, Edwin S., and James M. Murray, A History of Business in Medieval Europe, 1200–1550 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999) Magerøy, Ellen Marie, Islandsk hornskrud, Bibliotheca Arnamagnæana: Supplementum, 7 (København: Reitzel, 2000) Montanari, Massimo, The Culture of Food (Oxford: Blackwell, 1994) Oexle, Otto Gerhard, ‘Liturgische Memoria und historische Erinnung: zur Frage nach dem Grupåpenbewusstsein und dem Wissen der einigen Geschichte in den mittelalterlichen Gilden’, in Tradition als historische Kraft: Interdisziplinäre Forsch­ ungen zur Geschichte des früheren Mittelalters, ed. by Norbert Kamp and Joachim Wollasch (Berlin: Gruyter, 1982), pp. 323–40 Olrik, Jørgen, Drikkehorn og Sølvtøj fra Middelalder og Renaissance (København: National­ museet, 1907) Rubin, Miri, ‘Fraternities and Lay Piety in the Later Middle Ages’, in Einungen und Bruderschaften in der spätmittelalterlichen Stadt, ed. by Peter Johanek (Köln: Böhlau, 1993), pp. 185–98 Seierstad, Andreas, ‘Noko um religiøse minnedrikkjer i Noreg etter Reformasjonen’, Norsk Aarbok (1929), 10–37 Martyrs, Total War, and Heavenly Horses: Scandinavia as Centre and Periphery in the Expansion of Medieval Christendom Kurt Villads Jensen I t is commonly assumed that everything came a little later to Scandinavia than to the rest of Europe, and that, of necessity, culture and knowledge diffused from a centre in France to the European periphery. It is instead proposed in this article that cultural transmission always involved negotiation between sender and receiver, and that beliefs and institutions had to be adapted to local circumstances in order to be accepted. It is argued that the geographical periphery of the North played an important role in the Christian fight against evil and was a prime area for producing both martyrs and war-horses. It may have been the first place where religious wars were conducted against Christians, and where pagans were forced to choose between conversion or death. It is further argued that Christianity adapted to local circumstances and brought a God of war more than a suffering Christ, but also conversely that Nordic paganism (which we know only in glimpses) may to some extent have adapted to Christianity. Introduction Throughout the twentieth century, the majority of historians in Scandinavia agreed that everything came a little late to Scandinavia and other countries on the periphery of Europe — not only Christianity and all that was connected to church administration, education, and theology, but also trading organiKurt Villads Jensen (kvj@sdu.dk) is Associate Professor at Syddansk Universitet, Odense. Medieval Christianity in the North: New Studies, ed. by Kirsi Salonen, Kurt Villads Jensen, and Torstein Jørgensen, AS 1 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013) pp. 89–120 BREPOLS PUBLISHERS 10.1484/M.AS-EB.1.100813 Kurt Villads Jensen 90 zations, advanced economic administration and taxation, chivalric culture, military technology, and state formation. There was simply a time lag between western and central European history and developments in Scandinavia — a time lag of at least a generation, and sometimes centuries.1 It is not impossible to find good medieval sources to support the impression of a certain primitivism in the North. A German ecclesiastic, around 1170, described the Danish archbishop Asser (d. 1137) as knowledgeable and pious, but also as simple-minded and looking like a peasant or a pagan Wend.2 Anselm of Canterbury, on the other hand, had praised Asser in 1103 for his faith in wisdom and wisdom in faith.3 Also in the early twelfth century, the English William of Malmesbury wrote of the Danes’ incessant drinking and of how the Norwegians gorged themselves on fish,4 while Guibert of Nogent derided the Scots for their bare legs and hopelessly outdated military equipment.5 The ‘remotest part of the world’ or ‘the end of the world’ (ultima orbis provintia)6 became often-used designations for the areas where Christian territory ended and pagan lands, or the unending ocean, began: ‘The land of the primitives’,7 the land much distant from France, both in geographical terms and in the way people behaved.8 1 Examples are numerous, e.g. in the latest general history of Europe in Danish, in four volumes; see Kruse and Haakon Arvidsson, Europa 1300–1600, pp. 137–39. Insofar as historians outside Scandinavia wrote about Scandinavian history at all, they often agreed wholeheartedly, e.g. in discussions about whether Scandinavians learned trading first from Frisians and later from the Hanseatic League, or whether it developed independently. For the ‘Frisian theory’, see Christensen, Vikingetidens Danmark på oldhistorisk baggrund, pp. 112–15; for the German influence and the Hanseatic trade, see Blomkvist, The Discovery of the Baltic, pp. 420–24. 2 Herbordus, Herbordi Vita Ottonis episcopi, ed. by Pertz, bk iii, chap. 31. 3 Diplomatarium Danicum, ed. by Afzelius and others, 1st ser., ii: 1053–1169, ed. by Lauritz Weibull, with Niels Skyum-Nielsen (1963), no. 29. 4 William of Malmesbury, Gesta regum Anglorum, ed. and trans by Mynors, chap. 348, 2. William was writing in the 1120s. 5 Guibert of Nogent, Dei gesta per Francos et cinq autres textes, ed. by Huygens, 1. 1. Guibert was writing c. 1106. 6 Adam of Bremen, Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum, ed. by Lappenberg, bk iv, chap. 30, about Norway. Adam was writing in the early 1070s. 7 Abbot Peter of Cluny seems to have been fond of such expressions. He used it about Nor­way in a letter to the Norwegian king Sigurd c. 1123 (see below), and about Denmark and Norway in a sermon in 1157. Peter the Venerable, De laude dominici sepulchri, ed. by Constable, p. 246. Cf. also in general Fraesdorff, Der barbarische Norden, esp. pp. 120–29 on ‘Die Bewertung der Himmelsrichtungen’. 8 Peter de la Celle, c. 1178: ‘uestra Dacia remota est a nostra Francia. Distant enim et mor- Martyrs, Total War, and Heavenly Horses 91 On the other hand, we should take care not to over-emphasize the significance of such expressions in the sources. In general, medieval authors, as well as their antique role models, were inclined towards pejorative epithets and were quick to invoke stereotypes about other peoples or ethnic groups (or perhaps ‘races’, depending on how we translate the medieval word (gentes)).9 The ‘others’ were uncultured or uncivilized, no matter whether they lived on the geographical periphery of Europe or in the heart of France; they were primitive, uninfluenced by the evolution that most writers in the Middle Ages were convinced the world had undergone and was still undergoing.10 Change, and not petrified stasis, was characteristic of a world in which Christendom should be expanded ever further, brought to its remotest outposts, so that all would hear the Word and could be prepared for the ending of the world and the Second Coming of Christ.11 It was therefore a natural idea to describe those you did not like or who were far away from you as primitive and undeveloped, which reflects a medieval concept of history more than it reflects what actually happened during the Middle Ages. It is in any case possible that the main reason for the depiction of medieval Scandinavia as old-fashioned and backward does not stem from the medieval sources themselves but from an understanding of European history that developed in the second half of the nineteenth century. This view — in the wake of colonialism and a general belief in the history of progress — assumed ibus hominum et consuetudinibus siue situ terrarum’. Diplomatarium Danicum, ed. by Afzelius and others, 1st ser., iii, no. 81. 9 Reynolds, Kingdoms and Communities in Western Europe, pp. 250–56, esp. pp. 254–55, argues against the tradition of translating gens as ‘race’, while Bartlett, The Making of Europe, does so throughout his book. 10 Nisbet, History of the Idea of Progress, is an inspiring and pointed defence of the position that an idea of progress was also substantially a part of ancient and medieval world-views, and not exclusively a phenomenon of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment period. 11 One of the basic structures for writing sacred history in the Middle Ages was that of the Hexaemeron, which described Creation and what happened on the first seven days of the world’s history and, to varying extents, what had happened since then, paralleling the first seven days. The basic medieval idea of history was thus one of development towards a complex world with humans and animals and resources, and, after the Fall, with work and social structures as well. An important contribution to this genre was the Danish archbishop Anders Sunesen of Lund’s Hexaemeron from c. 1200, fully on a level with the best in western Europe at that time. See Freibergs, The Medieval Latin Hexaemeron. For medieval thinking about history and development and societies in general, see Töpfer, Das kommende Reich des Friedens; and Töpfer, Urzustand und Sündenfall. Kurt Villads Jensen 92 a core European centre in France or Germany, from which every good thing was passed on to neighbouring peoples, helping them to develop and slowly approach the level of civilization that marked out European modernity. This nineteenth-century obligation to civilize less ‘developed’ peoples continued to hold sway; for example the German expansion into Poland at the start of the Second World War was justified by reference to the Middle Ages and the Kulturträgertheorie that for more than a thousand years Germans had brought culture to the Slavic peoples in the East.12 In their most simplistic variations, such theories about a centre in France or Germany and a continuous expansion into the periphery become teleological. History could not have happened differently. Those on the margins would become Christians anyhow, in due time, sooner or later. Europe became Europeanized, as Robert Bartlett formulated it in 1993, and in the end it had no other choice. All culture emanated from the centre and diffused slowly outward, and on the periphery people sat passively, waiting to receive it — whether ‘it’ was writing, coins, military technology, Christianity, Crusades, or common saints to replace local ones. But this picture shows a complete misunderstanding of what actually happened and of how we should understand the dynamic of European medieval history. Dynamic Exchange: Adaptation of God and Re-Presentation of Sacred History The problem is not primarily the exact dating of elements and events. Some features can clearly be shown to have existed in France before they were present or became more commonly incorporated in Scandinavia, whilst others were surprisingly contemporaneous. Christianity came late to the North, but since antiquity new weapons, military machines, and principles of fortification were immediately introduced to Scandinavia, as archaeological investigations of war sacrifices of huge quantities of weapons have convincingly shown.13 When it concerned fighting for life in this world, the newest and most effective means 12 For example, the first volume of Urkundenbuch des Erzstifts Magdeburg, ed. by Israël and Möllenberg, published in 1937, which refers in the Introduction to the German colonization of eastern Europe in the Middle Ages as ‘the greatest cultural achievement of the German Middle Ages’: ‘Magdeburg […] wurde […] zur Metropole des gesamten Ostens, dessen Kolonisierung, das größte Kulturwerk des deutschen Mittelalters, hier seinen Ausgang genommen hat’ (i, p. vii). 13 Ilkjær, Illerup Ådal; Jensen, Danmarks oldtid, for the period after Christ, vols iii and iv. Martyrs, Total War, and Heavenly Horses 93 were accepted and imported without delay. When it concerned the afterlife, Nordic alternatives to Christianity seem to have had a strong attraction for Scandinavians for centuries and were deemed just as efficient as the faith of the Franks. ‘The Danes testify that Jesus verily is God, but they say that other gods are greater than Him, namely those who make greater signs and wonders for mortals’, as the Saxon Widukind summarized the southern Scandinavian position in the 960s.14 This points to a central fact in understanding the dynamics of cultural and religious transmission from one place to another. Scandinavians knew what was happening elsewhere in the Christian world, but they did not want it, because they had something better. Culture was negotiated and not just passively received. To accept or not to accept something from the centre was a cultural choice, and we must look at each specific feature and try to understand and explain why it was rejected or accepted at any given time; we cannot just assume in general that everything comes automatically if we wait long enough. There are two implications to this dynamic understanding of the relation between centre and periphery. One is that culture from the centre had to be chosen carefully, and possibly even changed and adapted to local circumstances, to be able to meet local demands. Early crucifixes in every part of Scandinavia depict a god for warriors, a conqueror of the world and of death, rather than the suffering Christ. The most impressive example of this is the royally commissioned rune stone in Jelling from c. 980, on one side of which a strong Christ gazes firmly out at the believer, and on the other a mighty lion is depicted fighting a dragon, while the carved runes proudly proclaim King Harald who ‘won for himself all Denmark and Norway and made the Danes Christians’. Among the different representations of Christ available in Europe, the Danish king had chosen the bravest and least humiliated, a Christ with clothes — belted garment and long sleeves — and suspending himself, not the naked and humiliated body on the cross. The Danish Jelling stone is a very early example of the kind of crucifixes that were known as the vultus sanctus after its most famous figure,15 in Lucca, said to have been carved by Nicodemus with the real face of the Saviour as its model. The Jelling vultus sanctus may have been inspired by a few early examples from England or from the Ottonian empire, but any direct background is difficult to point to today. 14 Widukind, Widukindi Rerum gestarum saxonicarum libri tres, ed. by Waitz, chap. 65. Nees, ‘On the Image of Christ Crucified in Early Medieval Art’, esp. p. 352. For representations of vultum sanctum in general, see Il Volto Santo in Europa, ed. by Ferrari and Mayer, passim. Thanks to Kirsi Salonen for drawing my attention to this publication. 15 Kurt Villads Jensen 94 Figure 6. The Jelling stone, 980s. Photo: Anne Pedersen. In the missionary period at the turn of the tenth century, Pope John IX (r. 898–900) declared directly that the newly-baptized Scandinavians should not be burdened with a strict observance of too many of the rules for a proper Christian life, for then they would probably fall away from faith again. It had to be accepted that they continued to kill each other and Christians and priests, and that they ate forbidden food in what looked most of all like pagan religious ceremonies. All this could be accepted as long as the church could rejoice that the Scandinavians now went to communion, so that those who spilled human blood had now been redeemed by the sweet blood of the Saviour.16 A minor 16 Epistola ad Heriveum; the Latin text with a translation is included as appendix at the end of this article. Martyrs, Total War, and Heavenly Horses 95 evil, the killing, had to be accepted to achieve a major good: namely that Scandinavians now formally belonged to the Christian flock. The same attitude towards the newly converted is also clearly expressed in a Nordic source, the Íslendingabók from the 1120s. Around the year 1000, the first Christian mission came to Iceland, and some were baptized, including some of the major chieftains, while others remained pagans and strongly opposed the new faith. At a general assembly on the mount of the law, the pagan Thorgeir the Law-Speaker suggested a compromise between the two faiths so that both had their way to some extent, because ‘when we break our law into two, we will also break our peace’. With two religions, people would start fighting and killing each other. It was then decided that everybody in the whole country should be Christian and baptized, but the exposure of newborns and the eating of horse meat should still be allowed according to the old religion. If anyone sacrificed to the old gods, it should happen at home and in secrecy; if there were any witnesses it would result in three years of outlawry. ‘And a few years later, that heathen practice was also taken away, like the others.’17 In other missionary areas, pagan practices were tolerated for a much longer time; for example, in Estonia in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, pagan burial practices and ceremonies remembering the dead were tolerated and only later actively fought against by Christian ecclesiastics.18 But it was not only the culture from the centre that was changed via adoption: the periphery itself also had to adapt to new impulses. Here we have the other implication arising from a dynamic interpretation of relations between centre and periphery: an understanding of how countries on the periphery strove to understand and portray themselves as the true centres, or at least as representing the values of the centre, perhaps even in a purer or better form. Recent investigations into saints’ cults in the northern and eastern peripheries of Europe, and history-writing and hagiography from the Orkney Islands and Iceland across Scandinavia to Hungary from the tenth to the thirteenth centuries, have shown how the sources tended to present the past as inevitably leading up to the present and thus to the martyrdom or miracles of the local saint. Taking inspiration from the classical genre of hagiography, northern authors created their own mythopoetics (as Lars Boje Mortensen labels it, following J. R. R. Tolkien19) — they turned the history of their own lands into a sacred 17 Íslendingabók, ed. by Finnur Jónsson, chap. 7, p. 17. Valk, ‘Christian and non-Christian Holy Sites in Medieval Estonia’. 19 Mortensen, ‘Sanctified Beginnings and Mythopoetic Moments’. 18 Kurt Villads Jensen 96 Christian history and created a whole new mythology for it. But in this way, they also positioned their own lands prominently in Christian providential history. God showed concern for mankind especially in Scandinavia, which in this literature therefore moved from the periphery to become a Christian centre. In a similar way, there seems to have been a concerted effort in Scandinavia from the beginning of the twelfth century to turn the wilderness in the North into a new Jerusalem. As in many other western European countries at the same time, round churches were built in imitation of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem,20 and relics were brought in huge quantities from the Holy Land to Scandinavia, not least the Holy Cross. The Norwegian king Sigurd Jorsalfarer brought a cross relic back from his Crusade in 1110 or 1111 which he had promised to place at the tomb of St Olav in Trondheim, but instead he installed it in the church in his new fortification in Kongshelle, on the border of pagan Västergötland, where for years it helped to repel the attacks of his enemies, until it was eventually stolen by Wends and had to be ransomed. 21 In 1123 Archbishop Asser consecrated the crypt in Lund Cathedral and enumerated all the relics placed there: not only a piece of the Holy Cross, but also of the manger from Nazareth, of the table of the Last Supper, and even a fragment of the stone Jesus had stood upon before ascending to heaven.22 In short, one could physically see and experience the whole life of Christ in Lund, and it was no longer necessary to go to the earthly Jerusalem; although of course the relics also had the opposite effect, actually inspiring more people than ever before to go on a pilgrimage or a Crusade. The transplantation of Jerusalem from the centre of the world to the geographical periphery worked, and in a relatively short time it attracted an amazing acceptance even from the centre of Christianity itself. In 1108, the archbishop of Magdeburg sent out a letter to ecclesiastics and princes in northern Europe and Flanders and invited them to a religious war against the Slavs who were attacking the Christian congregations, killing and pillaging.23 Both the 20 For round churches in the North, see Frölén, Nordens befästa rundkyrkor; on round churches or imitations of the Holy Sepulchre in other western European countries, with further references, see Morris, ‘Picturing the Crusades’, pp. 208–09. 21 Magnússona saga, ed. by Aðalbjarnarson, chap. 19; Magnúss saga blinda ok Haralds gilla, chaps 10–11. 22 Diplomatarium Danicum, ed. by Afzelius and others, 1st ser., ii: 1053–1169, ed. by Lauritz Weibull, with Niels Skyum-Nielsen (1963), no. 46. 23 Urkundenbuch des Erzstifts Magdeburg, ed. by Israël and Möllenberg, i, no. 193. For a recent analysis of the letter, see Constable, ‘The Place of the Magdeburg Charter of 1107/08 in Martyrs, Total War, and Heavenly Horses 97 German and the Danish kings had promised military support for the enterprise, and the archbishop generously promised to those who came to help liberate ‘our Jerusalem in the North’ the same indulgence as the Jerusalem crusaders received. A hundred years later, Pope Innocent III (r. 1198–1216) wanted to concentrate all Crusades on the liberation of the Holy Land and withdrew all indulgences for fighting in other areas.24 With one exception, however: at Lateran IV in 1215, Bishop Albert of Riga (r. 1199–1229) succeeded in explaining to the pope and cardinals that Riga and the Baltic coasts around it were the land of the Virgin Mary and of no less importance than Palestine, the land of the Son.25 The pope was persuaded and again granted indulgence to those fighting in the Baltic Crusades. Within a century, the periphery had become centre, and contemporary authors could now even call Riga and Livonia terra transmarina,26 the land on the other side of the sea, the normal designation of Palestine or Outremer. The Scandinavians and the peoples in the northern parts of presentday Germany had got their own Jerusalem, their own Palestine, their own crusading area. Martyrs on the Margin of the World The periphery became more original than the centre, in the sense that it was only in the religious border areas that it was still possible to be persecuted and suffer for Christ, and thus to gain the crown of martyrdom, as it had been in the Roman Empire in the good old days of the early church. Adam of Bremen in the eleventh century, and even more Helmold of Bosau in the twelfth and Henry of Livonia in the thirteenth, relate in detail how individual Christians met their death.27 Their writings tell us how churches were burned to the ground just before the year 1000; sixty priests were killed like cattle in the missionary area of Oldenburg, the rest were spared to be ridiculed and tortured. In Magdeburg the provost and priest were caught and had crosses cut so deep into their head that they broke the skulls and laid the brain open, and the rest the History of Eastern Germany’. 24 Fonnesberg-Schmidt, The Popes and the Baltic Crusades, pp. 83–91. 25 Henry of Livonia, Chronicon, ed. by Arbusow and Bauer. 26 Henry of Livonia, Chronicon, ed. by Arbusow and Bauer, chap. 15, sect. 4 27 In contrast, the Danish author Saxo who wrote around 1200 has surprisingly few stories about anything resembling a martyr, which may perhaps be explained by his eccentric attempt at being a classical Roman author rather than a good ecclesiastic. Kurt Villads Jensen 98 were flogged and driven from one village to the next till they died of exhaustion. Some Christians were sacrificed upon pagan altars.28 Bishop Christian of Magdeburg was beaten, and when he would not renounce his Christian faith, his arms and legs were cut off and his mutilated body thrown on the open square in the city, before his head was eventually cut off and put on a stake and offered to the heathen god Redigost.29 ‘There are so many martyrs in Denmark and the Slavic lands that one whole book is not enough to contain all their names’, the Danish king explained to Adam of Bremen.30 All this cruelty and death was a good thing, which true believers could take inspiration from and perhaps try to imitate. In the 1140s, the poor provost Keld, from Viborg in western Denmark, longed so much for martyrdom that he twice applied to the pope to get permission to go and preach Christianity to the pagan Wends and be killed, but the pope refused him the favour and judged that Keld’s presence in Viborg was more important. Perhaps as a kind of compensation, Keld became active in organizing the Danish participation in the Baltic part of the Second Crusade in 1147.31 More successful was Bishop Bertold in Livonia who with only two men to follow him in 1198 attacked a pagan army and was killed. ‘We believe that he is now crowned with honour and glory, because he was ardent in his desire to die.’32 Ardour to die may have been a desire shared by many religious persons throughout Western Christianity, but it was only possible to live out that desire on the periphery of Europe. Some of the vivid descriptions from Scandinavia of torture and cruel death have their closest parallels in contemporary saints’ vitae from missions to Muslim countries or further into Asia.33 It was also only along the religious border that it was possible to lead Crusades against infidels and gain the indulgence which seems to have been the primary motivating factor behind the 28 Adam of Bremen, Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum, ed. by Lappenberg, bk ii, chaps 42–44; Helmold of Bosau, Chronica Slavorum, ed. by Lappenberg, chap. 16. 29 Helmold of Bosau, Chronica Slavorum, ed. by Lappenberg, chap. 23. 30 Adam of Bremen, Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum, ed. by Lappenberg, bk ii, chap. 44. 31 Bysted and others, Jerusalem in the North, pp. 58–59. 32 Arnold of Lübeck, Chronica slavorum, ed. by Lappenberg, bk v, chap. 30. 33 Illustrative examples are the Martyrs of Cordoba in the 850s and the Martyrs of Morocco (c. 1220), who with great perseverance returned to Muslims again and again to be killed for insulting the prophet Muhammad, succeeding in the end despite the reluctance of the Muslim authorities. See Wolf, Christian Martyrs in Muslim Spain, for Cordoba; Madahil, Tratado da vida e martírio dos cinco Mártires de Marrocos, for Morocco. Martyrs, Total War, and Heavenly Horses 99 Crusade movement, of increasing importance throughout the twelfth and thirteenth centuries everywhere in Europe.34 Killing and Conversion From at least the fourth century, the expansion of Christianity was naturally secured by military means, but the use of force had never held an easy or uncontested place in the history of the church. The new theology of indulgence from the mid-eleventh century, and the markedly increased interest in the earthly Jerusalem in the same period, developed into a distinctly new missionary strategy: the Crusades. Warfare could now become a meritorious act in itself.35 If the killing was done to serve the church and with papal authority, it was no longer a sin. That was a totally new attitude to war which allowed for the novelty of the religious military orders, such as the Templars, founded in 1118, and the Hospitallers, who became militarized shortly afterwards.36 They combined the religious life of monks with the fighting life of knights. The first wave of crusaders in 1096–99 were closely connected through a network of St Peter’s vassals who had all sworn special allegiance to the pope and supported the Gregorian reform movement of the late eleventh century. The Danish king Svend Estridsen and his sons were also vassals of St Peter and members of this network, but the majority of the first crusaders came from Flanders and Normandy and other parts of France.37 It is tempting in the context of the present book to claim that warriors from these areas were especially susceptible to the idea of heroic warfare because many of them stemmed from Scandinavian Viking conquerors and had preserved for two hundred years their Nordic ésprit d’aventure.38 But in spite of the extensive network among 34 Riley-Smith, The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading; Bysted, ‘In Merit as Well as in Reward’. 35 Russell, The Just War in the Middle Ages; Tyerman, God’s War, pp. 27–91, with differing opinions on whether a major shift actually took place around 1100. Tyerman is not convinced of Russell’s thesis. 36 Riley-Smith, Hospitallers: The History of the Order of St John; Nicholson, The Knights Templar. 37 Riley-Smith, The First Crusaders, 1095–1131; and Diplomatarium Danicum, ed. by Afzelius and others, 1st ser., ii: 1053–1169, ed. by Lauritz Weibull, with Niels Skyum-Nielsen (1963), no. 17. 38 Riant, Expéditions et pèlerinages des Scandinaves, pp. 21–22. A concept of normannitas existed in the Middle Ages, and instead of understanding it in primitive biological terms, it may 100 Kurt Villads Jensen Norman families in the eleventh century from Sicily to Scandinavia, and in spite of the role the Normans played in the First Crusade, the changing attitude to war seems to me to be the result of contemporary changes in Christian theology rather than the involvement of Norman warriors. They may, however, have appreciated the new possibilities for pious killing. The idea of crusading was eagerly embraced by the peoples living on the European periphery. In Spain in 1101, Christian warriors received from Pope Pascal II (r. 1099–1118) the same indulgence as the crusaders to Jerusalem if they would stay home on the Peninsula and fight ‘your own Muslims’.39 In the Baltic area, the eleventh-century wars against pagan Wends now became real Crusades after the promulgation of the letter written by the archbishop of Magdeburg in 1108 (as mentioned above), and the Danish king was ready with his army to go on Crusade. Crusade theology developed slowly, and the first couple of crusading generations fought apparently without caring too much about formal definitions.40 However, it seems clear that a Crusade with indulgence was to be fought against Muslims or against Slavic pagans who had never been Christians. Although in principle it was impossible to force others to believe, in practice the enemies were often given the choice between baptism or death. Crusade from the beginning was a defence of the true faith against attack from outsiders; it was not an aggressive mission by sword — in principle, at least. Scandinavia seems to be one of the first known places where crusading took on a new direction, when in 1123 a common Danish, Norwegian, and perhaps Polish crusader expedition was directed against Swedish apostates around Kalmar.41 In hindsight this is unsurprising, because after the codification of canon law with Gratian around 1150,42 all Crusade theologians knew that herbe better explained as an ethnicity invented by Norman families expressing a peculiar ferocity, boundless energy, cunning, capacity for leadership, and simple piety, as explained in Gravett and Nicolle, The Normans, p. 8. 39 Pascal II, Epistolae et privilegia, letter 44, col. 63. 40 This is an enormous subject. Tyerman, ‘Were There Any Crusades in the Twelfth Century?’, and Tyerman, The Invention of the Crusades, pp. 8–29, deny that any clear concept of crusading existed until very late in the twelfth century. Most Crusade scholars today would agree that work on the theory of crusading became much more systematic and more common after the middle of the twelfth century. 41 Bysted and others, Jerusalem in the North, pp. 30–32; Blomkvist, The Discovery of the Baltic, pp. 307–34. 42 On the more precise dating and the process of codification of canon law, see Winroth, The Making of Gratian’s Decretum. Martyrs, Total War, and Heavenly Horses 101 etics and apostates could lawfully be forced back to Christianity through violent means, and they could be killed if they continued their wilful denial of the fundamental dogmas of faith. St Augustine himself had written so and was one of the fundamental authorities for Gratian in these matters about just warfare.43 In the 1120s, however, canon law did not exist as a readily accessible collection, Augustine’s views on war were probably much less known, and Crusades had up to then only been fought against Muslims and pagans. It must therefore have been a novelty when the Danish and Norwegian kings decided to go crusading against the population in Småland, ‘because those who lived there had received Christianity, but did not keep it. Because at that time in Svealand, there were many heathen peoples and many bad Christians, and some of their kings rejected Christianity and continued with their heathen sacrifices’.44 On a military level, the success of the expedition was very limited. The Danish contingencies came first and waited a long time for the Norwegians; eventually they believed that the others had given up the idea, and went back home. Shortly afterwards, King Sigurd arrived at the empty place and believed that he had been let down by the Danes, so he decided to plunder in Danish territory and went on to pagan lands around Kalmar, where he forced a number of the Smålanders to accept or return to Christianity.45 The episode is mentioned directly, with names of persons and places, only in a short passage in Snorri Sturluson’s thirteenth-century narrative which, however, clearly incorporates older source material. In a more indirect way we know about it from a letter written by Abbot Peter the Venerable of Cluny to King Sigurd which is undated but fits in perfectly with the Kalmar Crusade.46 The abbot gives thanks to the Lord who has placed King Sigurd at the outermost edge of the world — in extremis finibus orbis — under the frozen pole, but the 43 Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Friedberg and Richter, i: Decretum Gratiani, Pars ii, c xxiii, q. 6, c. 2; and q. 7 in general (cols 948 and 950–54). 44 Magnússona saga, ed. by Aðalbjarnarson, chap. 24 (pp. 263–64). 45 Nordic historians have doubted the veracity of Snorri’s words, holding that it would have been impossible to lead a Crusade against Christians — and that everyone in Småland was a Christian at this time. It has been suggested, without any textual foundation, that Sigurd’s expedition had been directed against the pagan Wends instead. Blomkvist, The Discovery of the Baltic; Lönnroth, ‘En fjärran spegel’, pp. 151–54. 46 Diplomatarium Norvegicum, ed. by Lange and others, xix, no. 25; also in Peter the Venerable, The Letters, ed. by Constable, i, 140–41, no. 44; notes, p. 128. Berry, ‘Peter the Venerable and the Crusades’, p. 144, suggests that the letter concerns a Crusade which Sigurd planned around 1130, shortly before his death, but her arguments are not convincing. Kurt Villads Jensen 102 Spirit of the Lord has, with the warmth from the south, softened the northern winds and melted the ice of infidelity. Sigurd has exchanged the sceptre of the king for the yoke of Christ and has fought against the enemies of the Cross, both in the remote areas in the Mediterranean and the Orient and in his own country. He has fought on land and at sea, and now he has collected a huge navy and is ready to set out again. Sigurd had begun to walk the way to perfection for the eternal kingdom, and Peter praises him and gives thanks to the Lord again. The concluding formulation about the road to perfection bears a distant resonance to papal formulas promising indulgence to other crusaders, but it is much less precise. There is, however, no doubt that Sigurd’s expedition had the full approval of Peter, who was one of the highest ranking ecclesiastics from one of the most fervently Crusade-supporting institutions of his day, Cluny itself. After Kalmar, Crusades against apostates and heretics became an accepted and integrated part of the general crusading movement everywhere in Europe and the Middle East. Similarly, a special prominence was given to Scandinavia and the Baltic area in connection with the Second Crusade in 1147. The background was the fall of Edessa on Christmas Day three years earlier, which led to large-scale preparations for the heretofore most numerous army to set out to defend the Holy Land. Closely parallel to the spread of the crusading idea to all peripheries of Europe, now the threat from the enemies of the Cross was also seen as imminent on all frontiers of Christendom. The danger was military, but even more spiritual, and therefore every attack upon Christians was seen as part of a common scheme to undermine and destroy Christianity. Abbot Bernard of Clairvaux was one of the leading organizers of the Second Crusade and travelled extensively in northern and western Europe to preach and exhort the listeners to take the cross. In spring 1147, he issued a general letter to archbishops, bishops, princes, and all faithful in the North.47 It is impossible to be more precise about its recipients, and whether it actually reached Scandinavian countries or not, but this is likely because of its content. Also, a cardinal visited Denmark in the same months with a view to persuading the 47 In Pommersches Urkundenbuch, ed. by Klempin and Konrad, i, 35–36, no. 31; and in a number of other editions. For the Second Crusade, see Phillips, The Second Crusade; on Bernhard’s preaching tour pp. 61–98; on the Wendish Crusade pp. 228–43. Phillips stresses (p. 236) that it is with this letter that the Wendish Crusades actually and formally first became proper Crusades on the same level as the Iberian and Middle Eastern Crusades. Cf. also Fonnesberg-Schmidt, The Popes and the Baltic Crusades, pp. 30–31. Martyrs, Total War, and Heavenly Horses 103 Danish king to take part in ‘the holy Bernard’s Crusade’.48 In the letter, Bernard first claims that the Crusades to the Middle East were a great success and that most of the gentiles and almost all of the Jews were about to enter Christianity. This is a wonderful example of the medieval abuse of history, being contrary to all the facts we have about the situation after the fall of Edessa, but it was important for Bernard’s argument. He continued in a similar vein, namely that the Christians’ success irritated the devil and made him grind his teeth, and that the devil had therefore raised his evil seed (cf. Genesis 15), the pagans, ‘whom the Christian powers have tolerated for far too long a time and the pernicious attacks of the pagans; and the Christian power held back his heel and did not bruise the venomous head’. Christian princes in the North were openly criticized for having tolerated pagans; and they were then summoned to convert the pagans or to eliminate them. Bernard firmly prohibits making any peace agreement with them for any reason, whether money or tribute, until, with the help of God, their worship or their nation has been exterminated — ‘donec auxiliante deo aut ritus ipse aut natio deleatur’.49 Debates about how exactly to understand Bernard’s words have been heat50 ed. Did he propose a radical break with the Augustinian tradition that faith cannot be forced, actually meaning that the only choice the pagans should be given was between conversion and death? Or should we understand the word natio as a technical term for an ordered society, so that the pagans should have the choice between converting and living in society as before, or continuing to be pagans but then without the legal and social status that the Christians had in society?51 The first interpretation is a very natural reading of the text as it is and only debatable because it seems too harsh on a theological level. Mitigating circumstances have been produced to ‘excuse’ Bernard. One idea is that his conviction that the end of the world was imminent added particular urgency to having all the gentiles converted before Armageddon.52 Another 48 Diplomatarium Danicum, ed. by Afzelius and others, 1st ser., ii: 1053–1169, ed. by Lauritz Weibull, with Niels Skyum-Nielsen (1963), no. 86. 49 Bernard of Clairvaux, Opera, ed. by Leclercq, Talbot, and Rochais, viii, no. 457. 50 Fonnesberg-Schmidt, The Popes and the Baltic Crusades, pp. 32–33; in more details Phillips, The Second Crusade, pp. 236–39; with reference both to former positions and to the scholarly literature. 51 Lotter, Die Konzeption des Wendenkreuzzugs; Lotter, ‘The Crusading Idea and the Conquest of the Region East of the Elbe’. 52 Proposed by Kahl, ‘Crusade Eschatology as Seen by St Bernard’, but criticized because such an apocalyptic fear does not seem to have played any significant role in other writings by Bernard. Kurt Villads Jensen 104 explanation has been that he was addressing a warrior class with little interest in theology, and that he tried to speak their language — that of heroic knightly tales such as the Song of Roland or the great Crusade narratives, which, without any restrictions, depicted the wars of Charlemagne or the battles of the First Crusade as a targeted extermination of the infidels who did not surrender and convert. On the other hand, the division between a learned and a popular culture in the Middle Ages has undoubtedly been exaggerated in medieval studies in the last decades of the twentieth century. Warriors and theologians belonged to the same families and met regularly and knew about each other’s business.53 The Cistercians in their monasteries copied theological treatises as well as the heroic poems, and almost all of the authors of the bloody Crusade narratives were actually ecclesiastics. Therefore, the most natural — albeit unpleasant — conclusion is that Bernard, through his preaching and theology in the North, initiated a violent mission which, from a broader chronological perspective, was much more reminiscent of Charlemagne’s forced baptism of the Saxons in the early ninth century and the Ottonians in the march areas north and east of the Empire in the tenth century than the Augustinian principles which had until then permeated twelfth-century Crusade thinking. The Land of Horses The North saw important changes in crusading in the expansion of its targets to include apostates, and in institutionalizing a forced conversion. But the area was also closely attached to the crusading movement on a much more practical level as one of the main European suppliers of heavy war-horses. Denmark was one of the most important horse countries and in the thirteenth century exported eight thousand horses per year on ships from the westernmost city of Ribe alone;54 thousands of others were shipped from other ports or driven over land southwards to the great horse markets in Holstein and northern Germany. When they passed through the city of Schleswig, six pennies had to be paid in toll for every horse, unless the rider was an ecclesiastic or a crusader.55 Denmark was famous for its fertile and green pastures and for its large numbers of fine horses, ‘which meant that the Danes were as splendid warriors 53 Bull, Knightly Piety and the Lay Response to the First Crusade. Skyum-Nielsen, Kvinde og slave, p. 312. 55 Danmarks Gamle Købstadslovgivning, ed. by Kroman and Jørgensen, i, 75. 54 Martyrs, Total War, and Heavenly Horses 105 from horseback as from ships’ decks’.56 Danish horses were typically bred on the many small islands and lived half wild, until they were old enough to be rounded up and broken in. They were famous for the heavy neck and soft skin, their high groins and golden complexion.57 The basic element in the medieval Danish horse seems to have been the Frisian, a heavily-built and hardy horse with relatively short legs and a large head.58 During the twelfth century this race was crossed with big Flemish stallions and gave a very strong and large horse, which was then crossed in turn with the Portuguese or Spanish Genette, a much slimmer and more elegant horse with a lot of Arabic blood in it. The result was a large but also fast and lithe horse which could carry a warrior in full armour and almost dance at the same time. This breeding system required regular and well-established contacts throughout Europe over a lengthy period. Kings and princes and individual nobles were part of it, but very soon the religious orders took over, and in various ways the Cistercians achieved a decisive role in the systematic war-horse production. They were well organized, introduced the effective grange system with huge farms cultivated by large groups of lay brethren living in almost slavelike conditions, and most of the Cistercians had the aristocratic background to work with horses. Most of all, they had international connections. From the beginning, the production of surplus money from the very worldly occupation of breeding war-horses gave occasion for serious doubts within the order, but that changed rapidly in only about a generation. The matter was first discussed in 1152 at the Chapter General, which directly forbade that any monastery sold foals to anyone outside the order.59 Five years later, in 1157, the regulations were mitigated a little and the Cistercians were allowed to trade horses and wool, but the foals were to be broken in only with the harness, not with the saddle, ‘so that it is trained for running’. The difference is obviously that with the harness the animal could be used as a working horse, but had it been trained with a saddle it could be used for races or in warfare. When the foals had changed their first four teeth, they should be sold before they changed the rest. If not, the monastery had to keep the foal itself and use it as a labour horse.60 56 Arnold of Lübeck, Chronica slavorum, ed. by Lappenberg, bk iii, chap. 5. Skyum-Nielsen, Kvinde og slave, p. 156. 58 Ettrup, ‘Esrum Kloster som hovedsæde for Frederiksborgstutterierne’; Ettrup, ‘Esrum Klosterstutterier’. 59 Statuta capitulorum generalium ordinis Cisterciensis, ed. by Canivez, 1152, § 18. 60 Statuta capitulorum generalium ordinis Cisterciensis, ed. by Canivez, 1157, § 37; 1158, § 3; 1175, § 27. 57 Kurt Villads Jensen 106 These regulations had no effect, and the systematic breeding of war-horses became so prominent among the Cistercians that in 1184 the Chapter General had to lift the prohibition against it, and decided instead that the income from the sale of well trained war-horses should be sent to the Chapter General which would then distribute it among the poorer monasteries.61 We do not know for sure where such poor monasteries were located, but in the latter half of the twelfth century it is obvious to point to some of the relatively newly founded monasteries in the religious border areas, many of which were attacked and plundered in the continuous warfare and sometimes had to move to safer locations. They certainly needed money, and they could not take part in the high-profit war-horse production. It would simply be too risky to have property of that value in such an insecure place. The monastery of Dargun near Mecklenburg was founded from Denmark in 1171 but destroyed by pagans in 1179 and had to be re-founded in 1186. 62 Doberan in the same area was founded also in 1171 and destroyed by another pagan uprising in 1198, moving to Eldena, but in 1209 it was re-founded in its original place by Cistercians from Doberan.63 Written sources from Scandinavia are appallingly few, but from 1214 we get a glimpse of how this tight connection between the Cistercians, holy war, and the local nobility worked in practice. King Valdemar II’s (r. 1202–41) nephew Niels had decided to go on a Crusade to the Holy Land to atone for his sins. He did not have sufficient means for the whole journey, ‘while the expenditures are so high because of all the different things that are needed on the way’. Niels did not want to borrow the money and preferred to pay himself, ‘because God would like that better’. Therefore he sold huge areas of land to the Cistercian monastery of Esrom for twenty marks of pure gold, and if he came home alive, he could buy back the land. One gold mark should be given to adorn the shrine of his name-saint Nicholas in Esrom, another four to his wife, two to a number of churches and to the poor, and two gold marks to three new altars in Esrom for the crusader saints Santiago, Nicholas, and Olav of Norway. The remaining nine gold marks should be delivered to Niels, partly in cash and partly in the form of war-horses from Esrom.64 He does not specify whether the horses 61 Statuta capitulorum generalium ordinis Cisterciensis, ed. by Canivez, 1184, § 7. Donat, Reinmann, and Willich, Slawische Siedlung und Landesausbau, p. 139. 63 McGuire, The Cistercians in Denmark. 64 Diplomatarium Danicum, ed. by Afzelius and others, 1st ser., v: 1211–1223, ed. by Niels Skyum-Nielsen (1957), nos 7 and 8. 62 Martyrs, Total War, and Heavenly Horses 107 Map 4. The Wendish areas around Mecklenburg. Map: Inger Bjerg Poulsen. were to be delivered on his arrival at the port of Acre in Palestine or whether he should have them immediately and ride them all the way to the Holy Land is not specified — which probably indicates that the latter was more likely. Esrom on Sjælland in the centre of the kingdom of Denmark was lavishly supported by the royal family and by local magnates. It obviously had a reputation for breeding war-horses for the Crusades, but they certainly also must have been sold to crusaders to the Baltic lands and northern Germany. Esrom supported the Baltic Crusades by providing crusaders with war-horses, by founding daughter monasteries as Dargun and Doberan, and — if Esrom followed the regulations stipulated by the Chapter General — by transferring the surplus from lucrative horse-breeding directly to the poor daughter-houses at the crusading borders. Heavenly Horses Horses were the medieval war machine and a very practical instrument for crusading, but they also evoked a range of associations with heavenly horses. During a decisive moment in the Maccabean wars, help had come from above in the form of riders from the sky: Kurt Villads Jensen 108 But when the battle waxed strong, there appeared unto the enemies from heaven five comely men upon horses, with bridles of gold, and two of them led the Jews, and took Maccabeus betwixt them, and covered him on every side with weapons, and kept him safe, but shot arrows and lightnings against the enemies: so that being confounded with blindness, and full of trouble, they were killed.65 The Maccabees were among the prime objects of identification for twelfth-century crusaders, who believed they were the new Maccabees and maybe even that they had surpassed them.66 The most famous Crusade speech from Denmark from this period was delivered in 1187 by Esbern Snare during Christmas celebrations with the king in Odense, when suddenly the news of the fall of Jerusalem to Saladin reached Denmark and the distinguished party. Esbern jumped to his feet and gave a long speech exhorting his fellow magnates to join him on a Crusade, to win fame and protect the church; during the speech he referred to the Maccabees.67 The most important horse in the Bible is of course the ‘white horse’: And he that sat upon him was called Faithful and True, and in righteousness he doth judge and make war. His eyes were as a flame of fire, and on his head were many crowns. […] And he was clothed with a vesture dipped in blood: and his name is called The Word of God. And the armies which were in heaven followed him upon white horses, clothed in fine linen, white and clean. And out of his mouth goeth a sharp sword, that with it he should smite the nations: and he shall rule them with a rod of iron: and he treadeth the winepress of the fierceness and wrath of Almighty God.68 Crusaders considered themselves members of the armies clothed in fine linen and led by Christ himself. In the Holy Land and on the Iberian Peninsula, it became very common, according to contemporary chroniclers, for earthly crusaders to receive sudden support from an army of warriors riding down out of heaven against the infidels. They were led by St James, by Isidore of Seville, or sometimes by St George, but the army itself consisted of dead crusaders who continued to fight and help their living comrades.69 Although such stories must have been known in 65 ii Maccabees 10. 29–30. Guibert of Nogent, Dei gesta per Francos et cinq autres textes, ed. by Huygens, 6.9. 67 De profectione Danorum in Hierosolymam, ed. by Gertz, chap. 5 (p. 467). 68 Revelation 19. 11–15. 69 On heavenly knights in general, see Morris, ‘Martyrs on the Field of Battle before and during the First Crusade’; Holdsworth, ‘An “Airier Aristocracy”’. On mural paintings and other 66 Martyrs, Total War, and Heavenly Horses 109 Figure 7. Reconstruction of tiles from the Cistercian monastery of Øm in Denmark. Probably thirteenth century. Øm kloster museum. Scandinavia, we apparently lack any reports of heavenly knights being observed during battles in Scandinavia. The riders for religion can, however, still be seen very clearly in a different kind of sources, the mural paintings of the almost two thousand Danish churches built and decorated in the High Middle Ages (from the twelfth to the fourteenth century). A number of them, unevenly distributed geographically,70 have preserved depictions of mounted warriors leaving home, fighting other armies, gathering for the siege of strongly fortified castles; but first of all killing enemies. This motif was popular, and scattered archaeological finds seem to indicate that the Cistercian monastery of Øm had its liturgically important southern entrance from the cloister to the church decorated with tiles containing motifs of fighting knights.71 When the monks during the Easter procession had symbolically left the earthly Jerusalem72 — the garden of the monastery — and with the crucifix lifted high above them symbolically entered the heavenly pictorial representations of heavenly knights, see Morris, ‘Picturing the Crusades’. 70 More are found in the south-eastern part of Jutland, the original royal centre since late Viking times. Examples are Skibet Church, and, further west, Aal, but mounted warriors are also found in other areas of Denmark. Ny Dansk Kunsthistorie, ed. by Frederiksen and Kolstrup, pp. 117–24; Gotfredsen and Frederiksen, Troens Billeder. 71 Gregersen and Jensen, ‘Munkene i Øm og deres klosterkirke’, p. 87. 72 On the interpretation of Cistercian Easter processions and the earthly versus the heavenly Jerusalem, see Bruun, ‘Procession and Contemplation in Bernard of Clairvaux’s First Sermon for Palm Sunday’. Kurt Villads Jensen 110 Jerusalem — the church of the monastery — they did so by the help of the mounted crusaders. The mounted warriors were often depicted in friezes below the main pictorial programme with scenes from scripture, and iconographic discussions about how to interpret them have often been heated. Do they represent battles from the Old Testament, from the New Testament, or from early church history, or are they attempts to illustrate contemporary crusades, in the Baltic or the Middle East? Or are they inspired directly by the histories from the Book of Maccabees, as one of the grand old authorities on Danish mural painting, Poul Nørlund, suggested in 1944?73 I would suggest that they can be all these at the same time. Just as writers of the twelfth century used the Old Testament names of Moabites and Amalekites to designate the Muslims of their time, so the pictures could represent both historical and contemporary military fights against evil. Warriors on horses are frequently attested all over Europe in the Middle Ages, both in paintings, in reported visions of riders from the sky, and as actual living and fighting warriors. It has sometimes been argued that chivalric culture came late to Denmark and Scandinavia and only under the influence of more advanced areas to the south, especially German lands. There is no reason at all to believe this. The breeding of war-horses for the Crusades was highly developed in Denmark, which from the middle of the twelfth century was developed to a large extent by the Cistercians. And mural paintings from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries show a fully realized understanding of the intimate relation between horses and religion known from scripture and contemporary European narratives. Warriors in Heaven — or in Valhalla Any discussion of how the Northern periphery reacted to influences from the European centre should attempt to address the question of the relationship between Nordic paganism and Christianity. This is a complicated issue, because pagan mythology is known only through testimonies on parchment written down in the thirteenth century. The main corpus is Snorri’s Edda from c. 1220–25, which contains a number of stanzas from poems which may perhaps be older or even much older but which are impossible to date with any 73 Nørlund, Danmarks romanske kalkmalerier, p. 168. For Nørlund’s discussion of the mounted warrior motif in general, see chap. 6. Martyrs, Total War, and Heavenly Horses 111 degree of certainty, either in absolute terms of years or centuries, or in relation to the process of Christianization.74 Not all scholars would agree, but arguments for distinguishing sharply between pagan and Christian elements in the Edda often become circular and highly debatable — for example, that initiation rites are known in all Indo-European cultures, and that initiation rites described in the Nordic sources therefore cannot have been introduced with Christianity but must have existed earlier.75 This sounds logical but still leaves us with the problem that we have no possibility at all of ascertaining to what extent former pagan rites of initiation have been changed and adapted to new circumstances when confronted with Christianity. A classic example is the story in the poem Hávamál about the god Odin: ‘I know that I hung on a windy tree nine long nights, wounded with a spear, dedicated to Odin, myself to myself ’.76 It is probably safe to say that there was some pagan myth behind this poem, but it is also obvious that tree and spear would be symbols of Christ to any thirteenth-century Christian. Sophus Bugge in 1881 interpreted the ‘windy tree’ as a kenning for the gallows and pointed to Germanic expressions in which the cross of Christ is translated as the gallows,77 as far back as in Wulfila’s translation of the Bible into Gothic in the late fourth century.78 Jens Peter Schjødt, however, interprets the windy tree as the general Indo-European tree of life. It is interesting in this context that the oldest known figure of Christ in Denmark — on the Jelling rune stone — places Him in a tree79 and not on a cross. The idea of Odin dedicating or sacrificing80 himself to himself is clear and good Anselmian theology, as expressed in Cur deus homo, in which it is by necessity that God must be incarnated to atone for the original sin from the fall in Paradise, and He does so by sacrificing Himself to Himself. On the other 74 A very fine introduction to this complex situation is Schjødt, Initiations between Two Worlds; for sources and dating, see pp. 85–103. Thanks to Else Mundal for her help with discussing these ideas and for references. See her article in this volume. 75 Schjødt, Initiations between Two Worlds, p. 105. 76 Discussed in detail in Schjødt, Initiations between Two Worlds, pp. 173–206. 77 Bugge, Studier over de nordiske Gude- og Heltesagns Oprindelse, pp. 291–308. 78 Gothic galga for Greek stauros, in e.g. Matthew 10. 38; Mark 15. 21; Luke 9. 23; i Corinthians 1. 17. Wulfila’s translation has been consulted on the internet-edition Wulfila Project <http://www.wulfila.be/> [accessed 4 February 2013]. 79 See also Fuglesang, ‘Crucifixion Iconography in Viking Scandinavia’. 80 The word is gefinn and there is a long scholarly debate on whether it should be understood as meaning ‘consecrated’ or ‘sacrificed’. Schjødt, Initiations between Two Worlds, pp. 184–96. Kurt Villads Jensen 112 hand, the purpose of Odin’s sacrifice is to gain wisdom, which does not appear to be a part of mainstream Christian theology of the thirteenth century. At one extreme, we have a pagan myth that has been rendered in a form which makes it perfectly comprehensible to a Christian audience. At the opposite extreme, we could perhaps imagine that the myth in Hávamál of Odin in the tree is simply a Christian construction of pagan tradition, a kind of perverted Christianity which was the only available mental image for Christians in the twelfth century, when they were to imagine how people would have been thinking in a long-dead pagan past, as was the case when Snorri wrote his Edda. It would fit well into twelfth-century Europe’s generally great interest in the pagan past, but ultimately we cannot know for sure which of the two interpretations is correct. Similarly, the Edda contains a description of the afterlife which seems to be quintessentially pagan and far from our normal understanding of a Christian paradise, but which may nevertheless be related somehow to twelfth-century ideas about Christian warfare and heavenly horses. Snorri relates how Odin collects the fallen warriors on the battlefield — the val. They have been designated or consecrated to him by the valkyrjur, the female and semi-divine mounted warriors who ride out from heaven and over the earth or ‘over air and sea’ to lead the men to Valhal, the home or fortress of Odin in the other world.81 The valkyrjur shine like lightning, just like the Maccabees, and they are armed with helmets and bloody chainmail, and with shining spears. Every morning the dead start fighting each other, but at noon they return to Valhal and start eating pork and drinking mead for the rest of the day. At the end of time, at Doomsday, Odin’s dead warriors will march out, eight hundred through each of the 540 doors of Valhal, to fight against the beast, the Fenris wolf, followed by the valkyrjur riding in the air. The alternative to this splendid and heroic life in Valhal was the dark and dull near-non-existence in Hel, a grey and wet location designated for those who die of illness or old age, without fighting.82 In spite of all the differences, there are certainly parallels to the Christian idea of a heaven with horses and mounted warriors who will ride out from the sky and take part in the great battle against evil, and to the idea that a brave warrior can fight his way to heaven by falling in battle, by becoming a martyr for the faith. Our glimpse of the Nordic mythology is so vague that we can 81 82 Völuspá, stanza 30. Snorra Edda. Cf. also Jensen, ‘Korstogene og Nordatlanten’, pp. 77–86. Martyrs, Total War, and Heavenly Horses 113 never be certain about the precise relationship between the two religions. One possibility is that the idea of Valhal is invented in the Nordic periphery and modelled upon contemporary crusader theology from the centre. It is more plausible perhaps that some idea of heroic death in battle existed in the pagan North, and that this facilitated the acceptance of crusader theology, even in its harsh Bernardine version, where it became a question of converting or killing. Centre and Periphery At the opening of this article a passage was quoted from c. 1170 about Archbishop Asser being pious but simple-minded and resembling a peasant or a pagan Wend.83 Historians who quote this passage never resist the temptation to balance it with another description of the Danes by Arnold of Lübeck from c. 1210, in which it is stated that the Danes have made no insignificant progress also in science and education. The magnates in the country send their sons to Paris not only to an ecclesiastical career, but also to acquire secular knowledge. They learn literature and the language of the country, and they have become advanced not only in the liberal arts, but also in theology. Because of the natural speediness of the Danish language, they are subtle not only in dialectics, but also in all matters pertaining to church affairs, and they become good ecclesiastical or secular lawyers and judges.84 Apparently a sign of progress within a generation, around 1200, and an indication that culture actually became further and further diffused, from centre to periphery. But the difference between the two quotations here reflects a difference of perspective between two authors much more than a measurable accumulation of knowledge or culture among Nordic peoples. What has been attempted in this article is to argue that at any given time there seems to have been a thorough knowledge in Scandinavia about what was happening in the centre of Europe, that institutions and ideas in the periphery and the centre mutually influenced each other, and that the acceptance and accommodation of institutions and ideas were always the result of a dynamic process, a deliberate choice, and not simply a passive, one-way process from centre to periphery. 83 84 Herbordus, Herbordi Vita Ottonis episcopi, ed. by Pertz, bk iii, chap. 31. Arnold of Lübeck, Chronica slavorum, ed. by Lappenberg, bk iii, chap. 5. Kurt Villads Jensen 114 Appendix The Letter of Pope John IX to Heriveus; c. 900.85 JOANNES episcopus, servus servorum Dei, reverentissimo confratri nostro HERIVEO Rhemorum archiepiscopo. Vestrae fraternitatis, vestraeque reverendae sanctitatis mellifluas litteras libentissime suscipientes, ac diligentissime pertractantes: et tristes admodum, et vehementer exstitimus exsultantes. Moerentes itaque de tantis calamitatibus tantisque pressuris atque angustiis, non solum paganorum, verum etiam Christianorum in vestris partibus (ut vestrarum assertio litterarum edocet) accidentibus: gaudentes siquidem de ipsa gente Northmannorum, quae ad fidem, divina inspirante clementia, conversa, olim humano sanguine grassata laetabatur; nunc vero vestris exhortationibus, Domino cooperante, ambrosio Christi sanguine se gaudet fore redemptam atque potatam. Unde multipliciter ei, a quo procedit omne quod bonum est, immensas gratiarum actiones rependimus, suppliciter obsecrantes ut eos soliditate verae fidei confirmare et aeternae Trinitatis gloriam agnoscere faciat, atque ad suae visionis inenarrabile gaudium introducat. Nam quod de his vestra nobis innotuit fraternitas, quid agendum sit quod fuerint baptizati et rebaptizati, et post baptismum gentiliter vixerint, atque paganorum more Christianos interfecerint, sacerdotes trucidaverint, atque simulacris immolantes idolothyta comederint: equidem si tirones ad fidem non forent, canonica experirentur judicia. Unde quia ad fidem rudes sunt, vestro utique libramini vestraeque censurae committimus experiendos, qui illam gentem vestris confiniis vicinam habentes, studiose advertere, et illius mores, actusque omnes pariter et conversationem agnoscere prae caeteris valeatis. Quod enim mitius agendum sit cum eis quam sacri censeant canones vestra satis cognoscit industria, ne forte insueta onera portantes, importabilia illis fore, quod absit, videantur, et ad prioris vitae veterem quem exspoliaverunt hominem, antiquo insidiante adversario, relabantur. Et quidem si inter eos tales inventi fuerint, qui secundum canonica instituta se per poenitentiam macerare, et tanta commissa scelera dignis lamentationibus expiare maluerint, eos canonice judicare non respuatis; ita ut in omnibus erga eos pervigiles existatis, ut ante tribunal aeterni judicis cum multiplici animarum fructu venientes gaudia aeterna cum beato Remigio adipisci mereamini. 85 From Epistola ad Heriveum, ed. by Migne. Martyrs, Total War, and Heavenly Horses 115 Translation From Bishop John, serf of the serfs of God, to our most revered brother Heriveus Archbishop of Rheims. Our brother’s letter, our Most Revered Holiness’s mellifluous letters we have received with joy and read carefully, and we were filled with sorrows and at the same time rejoiced strongly. We grieved over such calamities and difficulties and inconveniences, not only from the pagans, but even from what was done by the Christians in your region, as we learned from the description in your letter, but we certainly also rejoiced at hearing about the people of the Normans which, inspired by divine mercy, has converted, and those who earlier took joy in spilling human blood now, because of your exhortations and through God’s work, are happy for having drunk and being redeemed by the nectar of Christ’s blood. Therefore we give thanks without end to Him, from whom proceeds all that is good, and we pray again and again that He will confirm them in a steadfast faith and make them acknowledge the glory of the eternal Trinity, and lead them into the indescribable joy of the vision of Him. Concerning the things that you, our brother, have raised with us, namely what to do with those who have been baptized and re-baptized but after the baptism continue to live as heathens, and, like pagans, to kill Christians and massacre priests and eat the sacrifices that have been immolated to idols: truly, if they had not been newcomers to the faith, they would have been exposed to canonical judgement. But because they are unused to the faith, we will leave to your balanced view and your consideration whether they should be exposed to canonical judgement or not, because you have this race living near your region, and you more than anybody else are capable of studying them closely and understanding all their acts and how they live together. And your diligence has well enough learnt that it is better to act more leniently with them than the holy regulations of canon law prescribe, so that they should not, when they are carrying burdens to which they are unaccustomed, find it insupportable and — heaven forbid! — relapse into the old person of their former life whom they had now robbed from the ambush of the old enemy. But truly, if you find among them some who will not soften themselves by penitence as laid down in canon law, and who will not expiate the wickedness perpetrated with proper lamentations, do not refrain from judging them according to canon law, so that in all things you are always watchful over them, and that when you stand before the tribunal of the eternal judge, you can bring a great harvest of souls and earn eternal joy together with the holy Remigius. 116 Kurt Villads Jensen Works Cited Primary Sources Adam of Bremen, Adami Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum, ed. by Johann Martin Lappenberg, in Monumenta Germaniae Historica: Scriptores rerum Germanicarum in usum scholarum separatism editi, 75 vols (Hannover: Hahn, 1868–), ii, ed. by Bernhard Schmeidler (1917) Arnold of Lübeck, Arnoldi Chronica slavorum, ed. by Johann Martin Lappenberg, in Monumenta Germaniae Historica: Scriptores in folio, 38 vols in 40 (Hannover: Hahn, 1826–), xxi: Historici Germaniae saec. xii. 1, ed. by George Heinrich Pertz (1868), pp. 101–250 Bernard of Clairvaux, S. Bernardi Opera, ed. by J. Leclercq, C. H. Talbot, and H. Rochais, 8 vols (Roma: Editiones cistercienses, 1957–77) Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Emil Friedberg and Aemilius Ludwig Richter, 2 vols (Graz: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, 1959) Danmarks Gamle Købstadslovgivning, ed. by Erik Kroman and Peter Jørgensen, 5 vols (København: Rosenkilde og Bagger, 1951–61) De profectione Danorum in Hierosolymam, in Scriptores minores historiæ danicæ medii ævi, ed. by Martinus Clarentius Gertz, 2 vols (København: Gad, 1917–22), ii (1922), 444–92 Diplomatarium Danicum, ed. by Adam Afzelius and others, 36 vols in 4 series (København: Munksgaard, 1938–2000) Diplomatarium Norvegicum, ed. by Christian C. A. Lange and others, 22 vols (Oslo: Malling, 1849–1995) Epistola ad Heriveum, in Patrologiae cursus completus: series latina, ed. by Jacques Paul Migne, 221 vols (Paris: Migne, 1844–64), cxxxi (1853), cols 27–29 Guibert of Nogent, Guibert de Nogent, Dei gesta per Francos et cinq autres textes, ed. by R. B. C. Huygens, Corpus Christianorum, continuatio mediaevalis, 127A (Turnholt: Brepols, 1996) Helmold of Bosau, Helmoldi presbyteri chronica Slavorum a. 800–1172 ed. by Johann Martin Lappenberg, in Monumenta Germaniae Historica: Scriptores in folio, 38 vols in 40 (Hannover: Hahn, 1826–), xxi: Historici Germaniae saec. xii. 1, ed. by George Heinrich Pertz (1868), pp. 1–99 Henry of Livonia, Henrici Chronicon Livoniae, in Monumenta Germaniae Historica: Scrip­ tores rerum Germanicarum in usum scholarum separatism editi, 75 vols (Hannover: Hahn, 1868–), xxxi, ed. by Leonid Arbusow and Albertus Bauer (1955) Herbordus, Herbordi Vita Ottonis episcopi, ed. by George Heinrich Pertz, in Monumenta Germaniae Historica: Scriptores in folio, 38 vols in 40 (Hannover: Hahn, 1826–), xii: [Historia aevi Salici] (1856), pp. 746–822 Íslendingabók, ed. by Finnur Jónsson (København: Jørgensen, 1930) Magnúss saga blinda ok Haralds gilla, in Snorri Sturluson, Helmskringla, ed. by Bjarni Aðalbjarnarson, Íslenzk fornrit, 26–28, 3 vols (Reykjavík: Hið Islenzka Fornritafélag, 1941–51), iii, 289–95 Martyrs, Total War, and Heavenly Horses 117 Magnússona saga, in Snorri Sturluson, Helmskringla, ed. by Bjarni Aðalbjarnarson, Íslenzk fornrit, 26–28, 3 vols (Reykjavík: Hið Islenzka Fornritafélag, 1941–51), iii, 238–77 Pascal II, Epistolae et privilegia, in Patrologiae cursus completus: series latina, ed. by Jacques Paul Migne, 221 vols (Paris: Migne, 1844–64), clxiii (1854), cols 0031–0448A Peter the Venerable, De laude dominici sepulchri, in Giles Constable, ‘Petri Venerabilis sermones tres’, Revue Benedictine, 64 (1954), 224–72 (pp. 232–54) Peter the Venerable, The Letters of Peter the Venerable, ed. by Giles Constable, 2 vols (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967) Pommersches Urkundenbuch, ed. by Karl Robert Klempin and Claus Konrad, 10 vols (Köln: Böhlau, 1970–84) Statuta capitulorum ordinis Cisterciensis ab anno 1116 ad annum 1786, ed. by D. JosephMarie Canivez, 8 vols (Louvain: Bureaux de la revue, 1933–41) Widukind, Widukindi Rerum gestarum saxonicarum libri tres, ed. by Georg Waitz (Hannover: Hahn, 1882) William of Malmesbury, De gestis regum Anglorum: The History of the English Kings, ed. and trans. by R. A. B. Mynors, completed by Rodney M. Thomson and Michael Winterbottom, Oxford Medieval Texts, 2 vols (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998–99) Urkundenbuch des Erzstifts Magdeburg, ed. by Friedrich Israël and Walter Möllenberg (Magdeburg: [n. pub.], 1937) Secondary Studies Bartlett, Robert, The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization, and Cultural Change, 950–1350 (London: Lane, 1993) Berry, Virginia G., ‘Peter the Venerable and the Crusades’, in Petrus Venerabilis, 1156–1956: Studies Commemorating the Eighth Centenary of his Death, ed. by Giles Constable and James Kritzeck, Studia Anselmiana, 40 (Roma: Herder, 1956), pp. 141–62 Blomkvist, Nils, The Discovery of the Baltic: The Reception of a Catholic World-System in the European North (ad 1075–1225), The Northern World, 15 (Leiden: Brill, 2005) Bruun, Mette Birkedal, ‘Procession and Contemplation in Bernard of Clairvaux’s First Sermon for Palm Sunday’, in The Appearances of Medieval Rituals: The Play of Con­ struc­tion and Modification, ed. by Nils Holger Petersen and others, Disputatio, 3 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2004), pp. 67–82 Bugge, Sophus, Studier over de nordiske Gude- og Heltesagns Oprindelse, 2 vols (Christiania: Cammermeyer, 1881–89) Bull, Marcus, Knightly Piety and the Lay Response to the First Crusade: The Limousin and Gascony, c. 970–c. 1130 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993) Bysted, Ane L., ‘In Merit as Well as in Reward: Indulgences, Spiritual Merit, and the Theology of the Crusades, c. 1095–1216’ (unpublished doctoral dissertation, Syd­ dansk Universitet, 2004) Bysted, Ane L., and others, Jerusalem in the North: Denmark and the Baltic Crusades, 1100–1522, Outremer: Studies in the Crusades and the Latin East, 1 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2012) 118 Kurt Villads Jensen Christensen, Aksel E., Vikingetidens Danmark på oldhistorisk baggrund (København: Gyldendal, 1969) Constable, Giles, ‘The Place of the Magdeburg Charter of 1107/08 in the History of Eastern Germany and of the Crusades’, in Vita religiosa im Mittelalter: Festschrift für Kaspar Elm zum 70. Geburtstag, ed. by Franz J. Felten and Nikolas Jaspert (Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 1999), pp. 283–99 Donat, Peter, Heike Reinmann, and Cornelia Willich, Slawische Siedlung und Landes­ ausbau im nordwestlichen Mecklenburg (Stuttgart: Steiner, 1999) Ettrup, Flemming, ‘Esrum Kloster som hovedsæde for Frederiksborgstutterierne’, in Bogen om Esrum Kloster, ed. by Søren Frandsen, Jens Anker Jørgensen, and Christian Gorm Tortzen (Frederiksborg: Frederiksborg Amt, 1997), pp. 188–205 —— , ‘Esrum Klosterstutterier’, in Fjernt fra menneskers færden: sider af Esrum Klosters 850-årige historie, ed. by Jens Anker Jørgensen, Henrik Madsen, and Brian Patrick McGuire (København: Reitzel, 2000), pp. 76–101 Ferrari, Michael Camillo, and Andreas Meyer, eds, Il Volto Santo in Europa: culto e im­ magini del crocifisso nel Medioevo; atti del convegno internazionale di Engelberg (13–16 settembre 2000) (Lucca: Istituto Storico Lucchese, 2005) Fonnesberg-Schmidt, Iben, The Popes and the Baltic Crusades, 1147–1254 (Leiden: Brill, 2007) Fraesdorff, David, Der barbarische Norden: Vorstellungen und Fremdheitskategorien bei Rimbert, Thietmar von Merseburg, Adam von Bremen und Helmold von Bosau (Berlin: Akademie, 2005) Frederiksen, Hans Jørgen, and Inger-Lise Kolstrup, eds, Ny Dansk Kunsthistorie, 10 vols (København: Kunstbogklubben, 1993–96) Freibergs, Gunar, The Medieval Latin Hexaemeron: From Bede to Grosseteste (Los Angeles: University of Southern California Press, 1981) Frölén, Hugo, Nordens befästa rundkyrkor, en kunst- och kulturhistorisk undersökning (Stockholm: Frölen, 1910–12) Fuglesang, Signe Horn, ‘Crucifixion Iconography in Viking Scandinavia’, in Proceedings of the 8. Viking Congress, ed. by Hans Bekker-Nielsen, Peter Foote, and Olaf Olsen (Odense: Syddansk Universitetsforlag, 1981), pp. 73–94 Gotfredsen, Lise, and Hans Jørgen Frederiksen, Troens Billeder: Romansk kunst i Danmark (København: Gad, 1987; repr. 2003) Gravett, Christopher, and David Nicolle, The Normans (Oxford: Osprey, 2006) Gregersen, Bo, and Carsten Selch Jensen, ‘Munkene i Øm og deres klosterkirke’, in Øm Kloster: kapitler af et middelalderligt cistercienserabbedis historie, ed. by Bo Gregersen and Carsten Selch Jensen (Odense: Syddansk Universitetsforlag, 2003), pp. 81–93 Holdsworth, Christopher, ‘An “Airier Aristocracy”: The Saints at War’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 6 (1996), 103–22 Ilkjær, Jørgen, Illerup Ådal (Højbjerg: Moesgård, 2000) Jensen, Jørgen, Danmarks oldtid, 4 vols (København: Gyldendal, 2001–04) Jensen, Peter, ‘Korstogene og Nordatlanten’ (unpublished master’s thesis, Syddansk Uni­ versitet, Odense, 2007) Martyrs, Total War, and Heavenly Horses 119 Kahl, Hans-Dietrich, ‘Crusade Eschatology as Seen by St Bernard in the Years 1146 to 1147’, in The Second Crusade and the Cistercians, ed. by Michael Gervers (New York: St Martin’s, 1992), pp. 35–47 Kruse, Tove, and Haakon Arvidsson, Europa, 1300–1600 (Frederiksberg: Roskilde Uni­ versitetsforlag, 1999–2003) Lönnroth, Lars, ‘En fjärran spegel: Västnordiska berättande källor om svensk hedendom och om kristningsprocessen på svenskt område’, in Kristnandet i Sverige: gamla källor och nya perspektiv, ed. by Bertil Nilsson (Uppsala: Lunn, 1996), pp. 141–58 Lotter, Friedrich, ‘The Crusading Idea and the Conquest of the Region East of the Elbe’, in Medieval Frontier Societies, ed. by Robert Bartlett and Angus MacKay (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989), pp. 268–306 —— , Die Konzeption des Wendenkreuzzugs: Ideengeschichtliche, kirchenrechtliche und his­ torisch-politische Voraussetzungen der Missionierung von Elb- und Ostseeslawen um die Mitte des 12. Jahrhunderts, Vorträge und Forschungen hrsg. vom Konstanzer Arbeits­ kreis für mittelalterliche Geschichte: Sonderband, 23 (Sigmaringen: Thorbecke, 1977) Madahil, Antonio Gomes da Rocha, Tratado da vida e martírio dos cinco Mártires de Marrocos (Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade, 1928) McGuire, Brian Patrick, The Cistercians in Denmark: Attitudes, Roles, and Functions in Medieval Society (Kalamazoo: Cistercian, 1982) Morris, Colin, ‘Martyrs on the Field of Battle before and during the First Crusade’, in Martyrs and Martyrologies, ed. by Diana Wood, Studies in Church History, 20 (Oxford: Blackwell, 1983), pp. 79–101 Morris, Colin, ‘Picturing the Crusades: The Uses of Visual Propaganda, c. 1095–1250’, in The Crusades and their Sources: Essays Presented to Bernard Hamilton, ed. by John France and William G. Zajac (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998), pp. 195–216 Mortensen, Lars Boje, ‘Sanctified Beginnings and Mythopoetic Moments: The First Wave of Writing on the Past in Norway, Denmark, and Hungary, c. 1000–1230’, in The Making of Christian Myths in the Periphery of Latin Christendom (c. 1000–1300), ed. by Lars Boje Mortensen (København: Museum Tusculanum, 2006), pp. 247–74 Nees, Lawrence, ‘On the Image of Christ Crucified in Early Medieval Art’, in Il Volto Santo in Europa: culto e immagini del crocifisso nel Medioevo; atti del convegno internazionale di Engelberg (13–16 settembre 2000), ed. by Michael Camillo Ferrari and Andreas Meyer (Lucca: Istituto Storico Lucchese, 2005), pp. 345–85 Nicholson, Helen, The Knights Templar: A New History (Stroud: Sutton, 2002) Nisbet, Robert, History of the Idea of Progress (New York: Basic, 1980) Nørlund, Poul, Danmarks romanske kalkmalerier (København: Høst, 1944) Phillips, Jonathan, The Second Crusade: Extending the Frontiers of Christendom (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007) Reynolds, Susan, Kingdoms and Communities in Western Europe, 900–1300 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984) Riant, Paul, Expéditions et pèlerinages des Scandinaves en Terre Sainte au temps des croisades (Paris: Lainé & Havard, 1865) 120 Kurt Villads Jensen Riley-Smith, Jonathan, The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading (London: Athlone, 1986) —— , The First Crusaders, 1095–1131 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997) —— , Hospitallers: The History of the Order of St John (London: Hambledon, 1999) Russell, Frederick H., The Just War in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975) Schjødt, Jens Peter, Initiations between Two Worlds (Odense: Syddansk Universitetsforlag, 2008) Skyum-Nielsen, Niels, Kvinde og slave (København: Munksgaard, 1971) Töpfer, Bernhard, Das kommende Reich des Friedens: zur Entwicklung chiliastischer Zu­ kunfts­hoffnungen im Hochmittelalter (Berlin: Akademie, 1964) —— , Urzustand und Sündenfall in der mittelalterlichen Gesellschafts- und Staatstheorie (Stuttgart: Hiersemann, 1999) Tyerman, Christopher, God’s War: A New History of the Crusades (London: Penguin, 2006) —— , The Invention of the Crusades (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1998) —— , ‘Were There Any Crusades in the Twelfth Century?’, English Historical Review, 110 (1995), 553–77 Valk, Heiki, ‘Christian and Non-Christian Holy Sites in Medieval Estonia: A Reflection of Ecclesiastical Attitudes towards Popular Religion’, in The European Frontier: Clashes and Compromises in the Middle Ages, ed. by Jörn Staecker (Lund: Almqvist & Wiksell, 2004), pp. 299–310 Winroth, Anders, The Making of Gratian’s Decretum (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000) Wolf, Kenneth Baxter, Christian Martyrs in Muslim Spain (Cambridge: Cambridge Uni­ versity Press, 1988) The Making of New Cultural Landscapes in the Medieval Baltic Torben Kjersgaard Nielsen T aking the philosophy of the American anthropologist Clifford Geertz as a theoretical basis, this article investigates and discusses the Christianization process in the medieval Baltic of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries through an analysis of the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle and the Chronicle of Henry of Livonia. I argue that this was a process of forced conversion through continuous warfare brought upon the Baltic peoples by expansionist Christian powers fuelled by a crusading spirit. However, it is one of the main premises of the article that the Baltic peoples themselves had a decisive say in this process of historical change. By according an important historical agency to the Baltic peoples who eventually succumbed to Christian power, I attempt to show that the new Christian practices of baptism, cult buildings, and Christian mastery would change the ‘cultural landscape’ of the Baltic peoples, and also that the Baltic peoples themselves appropriated these changes in actions both of compliance and of resistance. Introduction In the Gesta Innocentii tertii, comprising the deeds of Pope Innocent III (r. 1198–1216), we read from the year 1207 of a report from the Danish archbishop Anders Sunesen.1 This report concerned the Baltic, and its contents 1 ‘Meanwhile, a report arrived from the Archbishop of Lund, whom he had appointed as legate for the conversion of the pagans, that the whole of Livonia had been converted to the Torben Kjersgaard Nielsen (tkn@cgs.aau.dk) is Associate Professor at Aalborg Universitet. Medieval Christianity in the North: New Studies, ed. by Kirsi Salonen, Kurt Villads Jensen, and Torstein Jørgensen, AS 1 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013) pp. 121–153 BREPOLS PUBLISHERS 10.1484/M.AS-EB.1.100814 122 Torben Kjersgaard Nielsen would have been quite uplifting to a pope of Innocent III’s stance and character.2 Unfortunately, we do not know the exact circumstances of this report, or, for that matter, precisely what the Archbishop wrote to the Pontiff. However, to the author of the Gesta the overall message seemed clear: due to the efforts of Archbishop Andreas, the whole of Livonia was now firmly Christianized and the Livonian people had accepted the sacrament of baptism. From other sources, we know this to be a rather modified truth: the pagans of the Baltic would only be fully Christianized towards the end of the thirteenth century at the earliest, and then still with the great exception of Lithuania.3 However, what is certainly true is that important changes to the Baltic region had occurred with the Christian expansion in the shape of Crusades and missionary attempts.4 Despite the report to Innocent III, the Crusades to the Baltic were never really at the forefront of papal political interest. The Danish historian Iben Fonnesberg-Schmidt has investigated papal policies towards the Baltic Crusades, and one of her main conclusions is that the popes bestowed privileges on the participants in the Baltic Crusades rather inconsistently, since they regarded these Crusades as of secondary importance. Only with the pontificate of Honorius III (r. 1216–27) did the papacy reach a consistent ‘policy’ towards the Baltic Crusades, regarding them as equal to the military endeavours in the East.5 Thus, the Baltic Crusades took on a different shape in comparison to the ‘original’ Crusades in the Near East under the auspices of papal power and with the aid of a plenary indulgence promised to every crusader. Christian faith, and no one remained there who had not accepted the sacrament of baptism, and the neighbouring peoples were, for the most part, ready for this’. The Deeds of Innocent III, trans. by Powell, p. 235; Leonid Arbusow found a reference to this report in Raynaldus’s Annales Ecclesiastici, Cf. Arbusow, ‘Ein verschollener Bericht des Erzbischofs Andreas von Lund’. 2 In many modern works, Innocent III is referred to as a pope who embodied a new pastoral stance in the papacy. Cf. e.g. Fonnesberg-Schmidt, The Popes and the Baltic Crusades, pp. 86–87. Likewise, Brenda Bolton has in numerous articles opted for a view of this pope as having specific pastoral interests. Cf. Bolton, Innocent III. 3 Cf. Christiansen, The Northern Crusades; Rowell, Lithuania Ascending. 4 See for instance the many fine articles in Crusade and Conversion on the Batic Frontier, ed. by Murray. 5 Cf. the conclusions and reflections in Fonnesberg-Schmidt, The Popes and the Baltic Crusades, pp. 249–55. Regional contacts between the peoples of the Baltic and the North were of course of great antiquity. Trade had been conducted between inhabitants of the Baltic Coast ever since the Iron Age. However, it was only in the atmosphere of the holy wars of the Crusades that the Baltic region became interesting as a target area for Christian expansion. Cf. Blomkvist, The Discovery of the Baltic. The Making of New Cultural Landscapes in the Medieval Baltic 123 Papal decretals calling for Baltic Crusades are small in number, and very often these bear witness only to a papal acknowledgement and sanction of activities already undertaken by Christian forces in the area. These dissimilarities aside, it is still the term ‘Crusade’ that best describes the warfare in the Baltic between pagan tribes and Christian powers between the end of the twelfth century and the middle of the fourteenth. The warfare was characterized not by large-scale military battles and campaigns but rather by a continuous military presence and the making of numerous — and easily broken — strategic alliances in the region. This was accompanied by mission, church building, and attempts at evangelization, as was hinted at in the report mentioned in the Gesta Innocentii. This situation of continuous warfare brought social changes of a fundamental nature to the Baltic: wholly new modes of production were introduced, new taxes levied, and the Baltic peoples would eventually be subjugated to new masters.6 Furthermore, with Christianity, the Baltic peoples experienced a dramatic change in their social and religious world-view. It is important, however, when assessing the impact of violent Chris­ tianization, not simply to consider the Baltic peoples as mute victims of an overpowering historical development to which they themselves had nothing to contribute. The premise of this article is in fact the opposite: witnessing the attempts at violent Christianization and colonization, the Baltic peoples acted and reacted, appropriated and confronted, and in doing so they also influenced the course of Christianization. Their change in world-view was not only brought about by the aggressors but also mediated by their own preconceptions. With this premise in mind it is my hope to point to what — for want of a better phrase — might be a Baltic or northern European imprint upon the history of Christianity and the Crusade movement of the Middle Ages. On Culture, Cultural Landscape, and Religion When dealing with culture, the insights of the famous American anthropologist Clifford Geertz (1926–2006) remain useful. His definition of culture — or rather, his compilation of elements of culture in a single phrase — possesses some important features, which are relevant also when discussing matters from the medieval Baltic. To Geertz, culture ‘denotes an historically transmitted pattern of meanings embodied in symbolic forms by which men communicate, 6 For an introduction to the social changes brought upon the Baltic with the Christian ex­ pan­sion Cf. Nielsen, ‘Mission and Submission’. Torben Kjersgaard Nielsen 124 perpetuate, and develop their knowledge of and attitudes towards life’.7 Since this article discusses mainly the important changes in the cultural landscape brought about by Christianization, I shall limit myself to stressing some specific points, which deal precisely with the ways in which culture is transformed. The Geertzian compilation-definition of culture obviously stresses the importance of man’s direct action in developing and communicating what to him would look like an inherited, yet changeable, historical pattern. In stressing this point, Geertz opted for an understanding of man inspired by the thoughts of Max Weber. In another very famous Weberian quote by Geertz, he characterized man as ‘an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun’.8 Culture, thus, is to be acknowledged as a system expressing itself through symbols, but at the same time as a system actually powered and operated by man. As such it is a system of communication, which we as humans are definitively marked by, but also a system, the direction, content, and form of which is changeable by us. In this article I shall loosely subscribe to a Geertzian notion of culture, stressing the necessity and capacity of human action.9 It is one of the basic assumptions in this article that cultural changes in the Baltic during the period of the Crusades were effected through deliberate and conscious processes instigated by human agents: even if the Christian ‘agents of Europeanization’10 probably did not think of their own actions as conscious 7 Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures, p. 89 (chap. 4, ‘Religion as a Cultural System’). The paragraph from the famous chapter ‘Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture’, in his seminal 1973 book, reads: ‘The concept of culture I espouse, and whose utility the essays below attempt to demonstrate, is essentially a semiotic one. Believing, with Max Weber, that man is an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun, I take culture to be those webs, and the analysis of it to be therefore not an experimental science in search of law, but an interpretive one in search of meaning. It is explication I am after, construing social expression on their surface enigmatical’ (Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures, p. 5). 9 The Geertzian position has been criticized for not trying to explain how and why cultures change. Furthermore, Geertz is often accused of aestheticizing culture by looking at it in a fixated manner, as a still picture. According to some who propound this critique, for instance the Norwegian anthropologist Fredrik Barth, it is necessary to examine how culture is construed and transmitted, how the web is spun, and not just how the pattern of the web looks. For a presentation of Geertz and a critique of his thought, see Krause-Jensen, ‘Clifford Geertz’. Especially on the topic of anthropology and change, the historian Natalie Zemon Davis offers a convincing defence of Geertz by focusing precisely on the important position of change in his writings. Cf. Davis, ‘Clifford Geertz on Time and Change’. 10 This is the phrase for the missionary and crusading Christian forces offered in Blomkvist, The Discovery of the Baltic. Even if the title of Blomkvist’s book suggests a rather high degree of generalist and systematic theoretical thought, using among others the world-system theories of 8 The Making of New Cultural Landscapes in the Medieval Baltic 125 attempts to change a ‘cultural landscape’, the development in the Baltic was in fact explicitly discussed by some of these agents themselves, if not in any exhaustive or self-reflective manner.11 Neither the results achieved, nor how they were achieved, were of course foreseen by these agents themselves. It was not the case that the Christian powers simply followed an already-laid plan to completion. Rather, the result of the cultural encounters between pagan societies and the Christian military mission was something of a third kind: a new type of Christian society in the Baltic would be the result, different from the ideas both of the Christian missionaries and, even more, of the Baltic societies before Christianity. It follows from these claims that the Christian expansionists were not the only historical agents in this process. My use of a Geertzian definition of culture implies the necessity of historical agency also in the illiterate Baltic peoples: the changing of the cultural landscapes of the inhabitants of the region had to take place with the active participation of these peoples themselves — in opposition or compliance, or in other ways along this spectrum. Obviously it is of some difficulty to document this precisely, since the Baltic pagan peoples themselves did not leave written evidence. However, to deny the pagan peoples a historical agency in this process of change is simply untenable. The new societies in the Baltic were the result of deliberate actions by all the human agents involved, crusaders, missionaries, and pagans alike. Let us turn to the other element in my conceptual phrase — landscape. My approach to Geertz’s definition of culture stresses change and temporality. Landscape, on the other hand, is of course first and foremost a spatial category.12 When brought together the two epistemological categories, time and space, seem to coincide. Temporal changes in culture affect the ways man conImmanuel Wallerstein, the book in fact offers a very close analysis of the specific development in the Baltic. 11 Besides the above-mentioned report to Innocent III, the two basic texts used in this article, The Chronicle of Henry of Livonia and the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle, are themselves testimony to this claim. See below for further information on the specific texts. 12 This fundamental division between time and space is not at all straightforward. The British archaeologist Barbara Bender raises two proposals: ‘The first: Landscape is time mate­ rialised: landscapes, like time, never stand still. The second: Landscapes and time can never be out there: they are always subjective’. And she goes on to state: ‘And there are many other sorts of peopled definitions of landscape: historical landscapes, landscapes as representation, landscapes of settlement, landscapes of migration and exile, and most recently perhaps, phenomenological land­ scapes, where the time duration is measured in terms of human embodied experience of place and movement, of memory and expectation. The list could surely be extended, but whatever the focus, time passes’. Bender, ‘Time and Landscape’, p. 103. Torben Kjersgaard Nielsen 126 siders his spatial surroundings as well. These time-culture and space-landscape interrelationships, however, also work the other way around. Cultural change is always also spatially defined, so that change always takes place in, and is directed or affected by, the physical landscape surrounding man.13 Thus, just as inevitably, significant changes in the landscape will affect the cultural outlook of man.14 However, in my usage of the term ‘landscape’ here, I do not directly consider the specific natural landscape of the Baltic. Nor will I consider at any length man-made material remains from the topography of this region, even if some of these may be of importance to what I am going to say below. Rather, I shall leave this topic to the archaeologists.15 Nevertheless, I still find Barbara Bender’s statement to be highly pertinent to my concept of cultural landscape: ‘The landscape is never inert, people engage with it, rework it, appropriate and contest it. It is part of the way in which identities are created and disputed, whether as individual, group, or nation-state’.16 13 The current worldwide worries about climate change are an obvious example of how such processes of cultural change affect our considerations of space and culture. 14 A number of understandings of the concept used in human geography underline the direct (both deliberate and accidental) effects of man upon the natural landscape, and only rather recently has a new orientation emerged in human geography, which more directly considers man’s conceptualizations of landscape. Cf. Rowntree, ‘The Cultural Landscape Concept’. The classic definition of ‘cultural landscape’ was offered in 1926 by American geographer Carl Sauer (1889–1975): ‘The cultural landscape is fashioned from a natural landscape by a culture group. Culture is the agent, the natural area the medium, the cultural landscape is the result’ (quoted from Fowler, World Heritage Cultural Landscapes, p. 21). UNESCO identifies different sorts of cultural landscapes: ‘Cultural landscapes fall into three main categories, namely: (i) The most easily identifiable is the clearly defined landscape designed and created intentionally by man. This embraces garden and parkland landscapes constructed for aesthetic reasons which are often (but not always) associated with religious or other monumental buildings and ensembles. (ii) The second category is the organically evolved landscape. This results from an initial social, economic, administrative, and/or religious imperative and has developed its present form by association with and in response to its natural environment. […] (iii) The final category is the associative cultural landscape. The inscription of such landscapes on the World Heritage List is justifiable by virtue of the powerful religious, artistic or cultural associations of the natural element rather than material cultural evidence, which may be insignificant or even absent’ [original emphasizing] (UNESCO, ‘Operational Guideline for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention’, p. 84). 15 A number of important archaeological findings and interpretations have been made over the past decade. Some of these are published in English and German in conference proceedings under the auspices of the so-called CCC — Culture Clash or Compromise, a research programme (1996–2005) hosted by the University of Gotland and led by Professor Nils Blomkvist. 16 Bender, ‘Introduction’, p. 3. The Making of New Cultural Landscapes in the Medieval Baltic 127 Before I proceed to the actual analysis of the texts left to us, I shall make remarks on the concept of religion, since the people of the premodern societies I am dealing with here — the pagans of the medieval Baltic and the Christians from what is now Germany and Scandinavia — took their most important pattern of meanings from that metaphysical realm we today would label as religion. Working as an anthropologist Geertz obviously also concerned himself with religion. His definition of religion is linked to his definition of culture: A religion is a system of symbols which acts to establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in men by formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and clothing these conceptions with such an aura of factuality that the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic.17 In the medieval Baltic as in Medieval Scandinavia, religion — being ‘a system of symbols with a pervasive power on man’ — would have been the primary epistemological system available to man. When trying to make sense of life, when trying to establish social order, and also when trying to change that order, religion would have worked as a symbolic system imbuing existence with meaning. In the Baltic region, this goes as well for the original pagans as for the Christian merchants, missionaries and warriors. Thus it is that when dealing with questions of politics, of the right social order, of the meaning of life, medieval man would use metaphysical, religious reasoning. The political, social, and mental (cultural) landscapes thus created were fundamentally also religious ones, finding their explanations in concepts and thoughts not from scientific observations of the physical world as we would do today but thought of and expressed in after- and other-worldly metaphysical categories.18 17 Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures, p. 90. One could argue that, by such a definition, Geertz would seem to diminish the effects of human action, in that in his definition it is religion per se which takes on the active part. It seems in his definition to be religion as a symbolic system that acts, and not man himself. This apparent incongruity aside, I still find his definition workable. 18 Examples: Political systems were often legitimized through religious concepts of the sacral king; normative ideas of the right social order were structured and developed — at least in Christianity — with references to holy and thus authoritative books which retold divine revelations and foretold the future. And the entire world-view of an individual in this place and time was framed by religious institutions and liturgies encircling him from life to death and thus giving meaning to life. For material on this from the Nordic countries (especially the Edda poetry) — but perhaps with results also applicable to the Baltic, see the works of the historian of religion Steinsland, Det hellige bryllup og norrøn kongeideologi; and Steinsland, Den hellige kongen. Torben Kjersgaard Nielsen 128 Thus, bearing in mind the interrelationship of the categories of time and space when dealing with cultural change, and accepting that cultural change always takes place in and is informed by the natural surroundings of man in his search for meaning, I hope that the investigations to follow will show some of the cultural changes involved in the drastic Christianization of the Baltic societies. The groves in the woods, the rivers running to the sea, and the villages and fields — all natural, physical surroundings of the Baltic peoples — were important settings for the change in world-view and perception brought upon and appropriated differently by the Baltic peoples of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. To investigate the changing of cultural landscapes in the contextual setting of the medieval Baltic, I have thought it wise to unfold the above theoretical and conceptual arguments in slightly more operational categories. I shall address two fundamental elements: the sacralization of religious landscape when introducing Christianity to the Baltic, and the de-sacralization of the pagan religious and social landscape, when trying to get Christianity to take hold in the minds of neophytes. The Setting One of the primary sources for the Baltic conversion process and Crusades — the so-called Livonian Rhymed Chronicle — provides a starting point for this analysis. This verse text produced in the 1290s by an anonymous writer, probably an active member of the Teutonic Order,19 gives a shorthand presentation of the area and some of its peoples from a decidedly Christian outlook: There are numerous pagans by whom we are oppressed. They do much harm to Christianity, as we will tell you, father. One group is called Lithuanians. Those pagans are arrogant and because of their great might, their army does much harm to pure Christianity. Nearby lies another group of pagans named Semgallians, who have great strength of numbers and dominate the lands around them. They impose 19 The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle constitutes the earliest extant example of literary output from the Teutonic Order. It survives in only one manuscript consisting of 12,017 lines in rhyming couplets in Low German with traces of Middle Low German influence. The Chronicle draws on oral tradition and documentary sources as well as eyewitness testimony. In dealing with the conversion and conquest of Livonia/Estonia by missionary and crusading powers, it is one of the most important sources for the history of the medieval Baltic. Cf. Murray, ‘The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle’. I have used the English translation, The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle, trans. by Schmidt and Urban. The Chronicle is also published in its Low German original as Livländische Reimchronik, ed. by Meyer. The Making of New Cultural Landscapes in the Medieval Baltic 129 hardships without relief upon those who live near them. The Selonians are also pagans and blind to all virtue. They have many false gods and perform evils without number. Nearby is another people named Letts. All these pagans have most unusual customs. They dwell together of necessity, but they farm separately, scattered about through the forests. Their women are beautiful and wear exotic clothing. They ride in ancient manner and their army is very strong whenever it is assembled. Along the seashore lies an area named Kurland. It is more than three hundred miles long. Any Christian who comes to this land against their wishes will be robbed of life and property. The Ösilians are evil heathens, neighbours to the Kurs. They are surrounded by the sea and never fear strong armies. In the summers, as we have cause to know, they raid those neighbouring lands, which they can reach by ship. They have attacked both Christians and pagans and their greatest strength lies in their fleet. The Estonians are also pagans and there are many mothers’ sons of them. That is because their land is wide and extensive. I cannot begin to describe it. They have so many powerful men and so many provinces that I do not wish to say anything more about them. The Livonians are also heathens, but we have hope that God shall sunder them from that, just as He has with Caupo, who has come here with us. God’s gentle wisdom has brought him to Christianity. His tribe is large and most of it has come to us and has accepted Baptism.20 Besides the obvious stereotypes, the quotation addresses the Baltic leaders as obvious targets for Christianization, and it mentions some of the pagan religious and social practices that would have to be suppressed and replaced by Christian ones, if Christianity were to take root in the region. Even if the text quoted is from the late thirteenth century, the Christian missionary activity in the region had been going on since the late twelfth century, with cultural encounters in trade having been in effect for centuries before the arrival of missionaries. The appearance of the third consecutive missionary bishop to the Baltic in the person of the German prelate Albert of Buxhövden in 1200, and his many years in office as Bishop of Riga (r. 1199–1229), spurred the writing of another important text, the Chronicon Livoniae of Heinricus. The chronicle was completed in 1227, probably as a partial report to the papal legate William of Modena. This chronicle, based extensively on Henry’s own eyewitness accounts, is the most important written source for Baltic history in the period c. 1184–1227. With Albert’s mission and the founding of the military order of the Sword Brothers in 1202, the mission to the Baltic was thoroughly milita20 The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle, trans. by Schmidt and Urban, pp. 5–6. Although the main text was written only towards the end of the thirteenth century, the quotation claims to be part of the above-mentioned status report delivered to Pope Innocent III in 1203. Torben Kjersgaard Nielsen 130 rized and several Christian powers would from now on strive to conquer and Christianize the Baltic region in a decisively competitive atmosphere.21 Sacralization of Cultural Landscape According to the Polish archaeologist Przemyslav Urbanczyk, paganism must be understood as a world-view acquired by the inhabitants in these regions through an informal process of socialization and upbringing in society at large. Urbanczyk calls this a ‘multigenerational tradition, and an inseparable element of the ideological system that regulated the life of the whole of society’.22 Unlike Christianity, Baltic paganism did not claim any specific origin in time, with a subsequent evolving history.23 In this process of socialization a considerable degree of conformity and consensus was involved, but it would be quite false to characterize the pagan societies as static.24 Christianity in the Baltic, on the other hand, was of course not slowly acquired through socialization. As stated above Christianity came to the Baltic from outside, bringing with it a well-developed belief system established originally through revelation, that is, being very specifically located, both temporally and spatially. Furthermore, Christianity was exclusively administered and interpreted by an easily distinguishable group of cultic officers, priests, and other prelates, displaying an 21 Quotations from Henry’s chronicle in this article are taken from the English translation of the Latin original: Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage. Latin quotes are from Henry of Livonia, Chronicon, ed. by Arbusow and Bauer. For information on Henry Cf. Nielsen, ‘Henry of Livonia’. For the plans on Danish mission to Estonia from 1170 onwards see Nyberg, ‘The Danish Church and Mission in Estonia’. For a short survey of the Baltic lands’ incorporation into Western Christianity, see Kala, ‘The Incorporation of the Northern Baltic Lands’. For an introduction to the Order of the Sword Brothers, see Lind, ‘Sword Brethren’, and the literature listed there. 22 Urbanczyk, ‘The Politics of Conversion in North Central Europe’, p. 16. 23 Baltic paganism was, however, very much spatially oriented, in that it specified a distinct geography for some of the ‘creatures’ in the pagan pantheon. For instance, the god Tharapita is said, by Henry of Livonia, to have been born in a forest in Viljandi from where he (!) later flew to the island of Ösel. Cf. Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, pp. 193–94. 24 Quite the contrary, in fact, a number of the pagan European societies in the Middle Ages would display a rather marked adaptability towards ‘foreign’ religious influx. A telling example is the pagan god Svantevit, venerated in the eleventh and twelfth centuries by pagans living on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea. Some scholars argue that Svantevit was a pagan transformation of the Christian saint Vitus originating from Bohemia. Cf. Danske korstog, ed. by Lind and others. The Making of New Cultural Landscapes in the Medieval Baltic 131 organizational structure rather different from pagan society. Paganism, thus, is claimed to have been inherently social, whilst Christianity had to be deliberately instituted in the Baltic through learning and acquisition.25 Such a fundamental difference between paganism and Christianity is sometimes claimed also when discussing landscape. The Swedish archaeologist Stefan Brink states that ‘During pre-Christian times, all nature and landscape were metaphysically “charged” in different ways, with different degrees of energy, as regarded holiness or sacrality; the landscape was metaphysically impregnated as a totality, and people lived in a numinous environment’.26 We have of course almost no possibility of proving these assumptions, but it may suffice to compare them again directly to Christianity, the learned representatives of which would introduce a clear distinction between sacred and profane.27 The primary manifestations of this new and fundamental division would be the erection of churches and chapels, firstly in wood and later in stone, almost as islands of Christian sacrality in a sea of pagan numinous nature. 28 In other words, we can claim that paganism in a sense emanated from the material world. In opposition to this, Christianity and its symbols were very specifically located 25 Urbanczyk seems to claim a universal validity for his, in my view, somewhat formalistic distinction. However, his contrast between Christianity and paganism seems to me to hold true only in times and places of rapid change, e.g. the Baltic in the period I am discussing here. On this general level of analysis, there is no difference between the two religions per se: for a person born into and raised in a medieval Christian environment as well, Christianity would be considered something ‘naturally acquired’, and so wholly on a par with the way in which pagan religion evolved over generations. There are of course huge differences in the two religious approaches, e.g. when it comes to content and form of transmission. For example, paganism was based to a great degree on oral transmission; whereas the acquisition of Christianity was based instead on religious tenets fixed in writing. Where they are similar, however, is in their status: either as a pagan or as a Christian you simply ‘know’ that you have to learn important elements of your religion. For Christians and pagans alike this knowledge was — to use Urbanczyk’s phrases again — a ‘multigenerational tradition’ with a high degree of ‘conformity and consensus’. 26 Brink, ‘Mythologizing Landscape’, p. 83. 27 The classic work on this classic (Durkheimian) distinction is Eliade, Sacred and Profane; Cf. also Brereton, ‘Sacred Space’. Eliade’s ideas have been appreciated and further developed by many scholars since the appearance of his book, and in recent years mostly by emphasizing the fluidity of boundaries between the basic concepts of sacred and profane. For a short introduction see Hamilton and Spicer, ‘Defining the Holy’; See also Werblowsky, ‘Introduction’. 28 For an interesting discussion of the sensual elements of Christianity, including the smell of incense and the sounds of church bells in mission and warfare, see Jensen, ‘Crusading and Christian Penetration into the Landscape’. Torben Kjersgaard Nielsen 132 in the material world.29 Eventually, with the introduction of Christianity to the Baltic, a once diffusely numinous landscape would over time become more clearly compartmentalized. The ‘sacred’ would eventually be contained only in designated religious buildings, in which one could feel the numinous presence of a now singular God. In the process, the rest of the physical environment would be declared profane, and thus had to be ‘discharged’ from the sacrality associated with pagan pantheons, lower deities, elves, and spirits.30 One can only speculate as to how the introduction of a sharper division between sacred and profane in itself worked to change man’s perception of the natural world, making it ‘uncanny’, if we may use that word: the abode of monsters, of pagan remnants, and of generalized fear.31 This introduction of what must be termed a new thought system, bolstered by both physical and ideological structures, must have had effects on the cultural landscape of the former pagans. They would now have to come to terms with a wholly new conceptual understanding of the world around them. The Estonian archaeologist Heiki Valk argues for a prolonged Christianization in the Baltic. Valk shows that the Christian church, having displayed an initial indifference towards pagan practices of local village burials and cremations, the worship of local holy sites and the active 29 Cf. e.g. Howe, ‘The Conversion of the Physical World’; and Howe, ‘Creating Symbolic Landscapes’. 30 Howe, ‘The Conversion of the Physical World’, pp. 66–67, states: ‘Unless wilderness springs, wells, forests, and mountains were specifically claimed for Christ, their pagan resonances remained. […] Pagan geography had to be converted into Christian geography’. Howe adduces numerous sources showing the early medieval Christians to be quite aware of the demonic nature of pagan geography and accordingly forbidding Christians to visit temples or leave offerings or candles at pagan sites. Howe is contributing importantly to the discussion on whether or not Christianity had a sacred geography of its own or rather had to convert pagan geography into a Christian landscape. For this discussion, see also Markus, ‘How on Earth Could Places Become Holy?’; See also the contribution by Else Mundal in this volume. Bartlett, ‘The Conversion of a Pagan Society in the Middle Ages’, and Jensen, ‘How to Convert a Landscape’; both deal with the ways in which the Christian authorities, in Pomerania in the tenth and Livonia in the thirteenth centuries respectively, go about evangelizing and converting, destroying pagan idols, and the like. My approach here is slightly different in that I wish to highlight the effects and appropriation of such measures primarily in the minds of the people targeted by the missionary strategies, and to underline the important aspect of (historical) agency in the individuals involved in these actions. That is to say, I do not directly disagree with the results presented by Bartlett and Jensen, but rather I am attempting to turn the looking glass around when investigating the sources. 31 Here I shall not deal in particular with the specific attitudes towards the profane, physical world, as these were advocated by some Christian chroniclers. See however Nielsen, ‘Henry of Livonia on Woods and Wilderness’, for a discussion of the subject. The Making of New Cultural Landscapes in the Medieval Baltic 133 remembrance of the dead through rituals such as eating on their graves, later in the Middle Ages came down hard on the pagan rites and attitudes. Even today religious attitudes in Estonia display clearly syncretistic features. Valk in his investigation uses folkloric material collected in the late nineteenth century, as well as toponymic studies. This material of course does not allow us to determine whether these hybrid Christian-pagan practices had been in use continuously since the thirteenth century.32 In contrast to this view, another Estonian archaeologist Marika Mägi argues for a swift change of religion, at least on the island of Ösel. Arguing from archaeological material in burials and cremations, she states: ‘The concept that violent Christianization during the conquest of Saaremaa was a change too abrupt for the mentality of the Osilians, and therefore was not accepted for a long period, is mostly based on the interpretation of written sources from the 13th century’.33 These are however exactly the sources used in this connection. And they state rather clearly that something decisive happened to the people targeted by Christianization even before the new Christian division of physical landscape and cult buildings. Judging from one of the basic texts on the missionary Crusades to the Baltic, the building of churches was in fact not the initial concern for the Christian missionaries and religious authorities. The decisive and primary missionary act seems rather to have been the creation of a sacral body in the Christianized persons. In other words, it was baptism which seemed to have the primary attention of the missionaries and priests. The ‘sacralization of religious landscape’ took place within individuals: The singular neophyte would be ‘charged with holiness or sacrality’ precisely through baptism, the exclusive symbol of having accepted Christianity. St Augustine considered baptism so important that it should only be offered to people who, by their own free will and in their actual behaviour, demonstrated a real and deep inner conversion to the Christian faith.34 In the thirteenth-century Baltic, this was an 32 Valk, ‘Christian and Non-Christian Holy Sites in Medieval Estonia’. Cf. also Staecker, ‘In atrio ecclesiae’. 33 Mägi, ‘From Paganism to Christianity’, p. 33. 34 For example Scheffczyk, ‘Taufe’. The Augustinian baptismal preconditions were eventually reduced, in subsequent centuries, to demanding from the person wanting to be baptized a short version of the Catholic Creed, particularly the parts involving the renunciation of paganism and the punishment for apostasy. In the High Middle Ages important elements of baptism were the three different ways of dealing with holy water: immersio, infusio, and aspersio, each involving different levels of liturgical display. The most elaborate baptismal liturgy, the immer­ sio, was also the most commonly used in western Europe in the Middle Ages and consisted of 134 Torben Kjersgaard Nielsen entirely idealistic claim, since baptism here was tightly connected to warfare and submission. Indeed, Christianization in the Baltic in the thirteenth century can only be called a forced conversion. Following yet another Christian campaign against the Selones in 1207, Henry of Livonia would write: They marched toward Ascheraden, crossed the Dvina, and found the unburied bodies of the Lithuanians killed in the previous campaign. They trod over them and, marching in ordered ranks, came to Selburg. From all sides they laid siege to the fort, wounded many on the ramparts with arrows, captured many in the villages, killed many, brought together logs, and made a great fire. They gave the Selones no rest day or night, and struck fear into their people. Hence the latter secretly called together the leaders of their army and begged for peace. The Christians then said: ‘If you wish true peace, renounce idolatry and receive the true Peacemaker, Who is Christ, into your camp; be baptized and, moreover, remove the enemies of Christ’s name, The Lithuanians, from your fort.’ These terms of peace pleased the Selones and, after giving hostages they promised to receive the sacrament of baptism. Moreover, after they had removed the Lithuanians, they vowed to obey the Christians in all things. After receiving their boys, therefore, the army was pacified. Accordingly the abbot and the provost, with the other priests, went up to them in the fort, instructed them in the beginnings of the faith, sprinkled the fort with holy water, and raised the banner of Blessed Mary over it. They then rejoiced over the conversion of the pagans, praised God for the advancement of the church, and, together with the Livonians and Letts, returned joyfully to their country.35 We learn nothing here of the necessary ensuing rituals to complete the baptism. This was apparently a rather often used tactic, since Henry of Livonia is outspoken on the matter. His relation of a siege of an Estonian castle in 1211 clearly demonstrates the Christian method of subjugation, in the Baltic at least: first you conquer the pagans by force, then you negotiate the terms of peace, and after demanding hostages you instruct the leading figures of pagan society in the rudiments of the Christian faith; finally you sprinkle the pagans with holy water, thus initiating the sacrament of baptism. Henry writes: On the sixth day, the Germans said: ‘Do you still resist and refuse to acknowledge our Creator?’ To this they replied: ‘We acknowledge your God to be greater than prolonged exorcist rituals before a three-fold immersion of the entire body in the baptismal font, followed by the laying on of hands and formal abjurations of one’s former faith, before the final blessings. However, in western Europe the prolonged baptismal rites as displayed in liturgical books show ‘einer archaischen Idealzustand […], der in der frühma. frk. Kirche längst die Ausnahme von der Regel geworden war’. Langenbahn, ‘Taufritus’. 35 Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, chap. XI, 6 (p. 74). The Making of New Cultural Landscapes in the Medieval Baltic 135 our gods. By overcoming us, He has inclined our hearts to worship Him. We beg, therefore, that you spare us and mercifully impose the yoke of Christianity upon us as you have upon the Livonians and Letts.’ The Germans, therefore, after calling the elders out of the fort, disclosed to them all the laws of Christianity and promised them peace and brotherly love. The Esthonians rejoiced greatly over peace simultaneously with the Livonians and the Letts, and they promised to receive the sacrament of baptism on the same terms. When hostages had been given and peace had been ratified, therefore, they received the priests into the fort. The priests sprinkled all the houses, the fort, the men and women, and all the people with holy water. They performed a sort of initiation and catechized them before baptizing but postponed administering the sacrament of baptism because of the great shedding of blood which had taken place. When these things had been done, therefore, the army returned to Livonia and they all glorified the Lord for converting the tribes.36 In the passage above, Henry mentions elements of the baptismal ceremonies (initiation and catechism) and in his distinctions he reveals himself to be well aware of the prescribed baptismal requirements both in the persons subjugated to the sacrament and in those bestowing it. On another campaign, this time against the Ösilians in 1227, he relates: The sons of the nobles were given up. The venerable bishop of Riga joyfully and devotedly catechized the first of them and watered him from the holy font. Other priests poured water on the other hostages. The priests were led with joy into the town in order to preach Christ and throw out Tharapita, the god of the Oesilians. They consecrated a fountain in the middle of the fort, filled a jar, and, after catechism, baptized first the elders and upper-class men and then the other men, women, and boys. From morning to evening the men, women, and children crowded very closely around, shouting: ‘Hurry and baptize me,’ so that even these priests, of whom there were sometimes five, sometimes six, were worn out with the work of baptizing.37 Apparently, the Christian missionaries did not take the prescribed baptismal liturgies too seriously. However, this need not worry us here, since what I am interested in is not the canonical acceptance or non-acceptance of mass baptism through sprinkling or the like but rather the effects of these actions on the priests doing the sprinkling, watering, and baptism, as well as the peoples subjugated to these actions. 36 37 Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, chap. XV, 1 (pp. 106–07). Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, chap. XXX, 5 (p. 244). 136 Torben Kjersgaard Nielsen Obviously, what we are witnessing in these passages is exactly this: people performing or taking action — and doing so in a specific and knowledgeable way.38 The Christian missionaries worked with specific actions and unintelligible Latin. Thus, when reading the sources it becomes obvious that the physical acts of watering, sprinkling, and murmuring strange gibberish would in fact have serious consequences — both for the priests doing the sprinkling and for the now former pagans. Firstly, the missionaries themselves hoped that their actions would have consequences for their own salvation. The missionaries and priests acted in part because their actions and the interpretations of these actions in their minds imbued in them a sense of doing good and honourable things to others, which would also work to benefit themselves. Apparently, the Christian priests did not sprinkle holy water on the conquered pagans solely out of a wish to ‘change a cultural landscape’ in the minds of the pagans through baptism. They also hoped to improve their own situation in the hereafter. This element is rather obvious in Henry’s chronicle, even if he describes it allegorically, alluding to both classical authors and Christian ritual books: So the priests, with great joy, baptized all the people of both sexes in all the forts of Oesel. The priests wept from joy because, by the bath of regeneration, they were producing so many thousands of spiritual children for the Lord and a beloved new spouse for God from among the heathen. They watered the nation by the font, and their faces by tears. 38 This of course hints at an immensely important discussion. The question of the so-called ‘performative turn’ in history as well as other disciplines of the humanities has been discussed intensely over the past decade or so. In an important and thought-provoking essay, Peter Burke argues that ‘on different occasions (moments, locales) or in different situations (in the presence of different people) the same person behaves in different ways’. Burke, ‘Performing History’, p. 36. Obviously, this apparently banal observation has implications for any historian wrestling with the written sources trying to figure out what is going on and how to understand this: ‘What used to be treated as the “same” ritual is now regarded as varying significantly on each new occasion of performance. Hence the increasing emphasis on the part of the historians on what went wrong, what “misfired”, as [ J. L.] Austin used to say. Of course, if meanings are unstable and contested, if there is no “correct” interpretation, terms such as “wrong”, “misfire” or even “misunderstand” become inappropriate. However, they can be reformulated in terms of divergences from tradition, from the official point of view, from the intentions of the organisers of a particular ritual and so on. The strategy of studying the gap between “script” and practice remains a valuable one’ (p. 42). Burke’s statement is important in this connection, because at least some of the discussions of performativity assume as an epistemological condition for human action a cultural ‘fluidity’ as opposed to a cultural or social ‘fixity’ (p. 35). The inspiration for this stems largely from Pierre Bourdieu, who in introducing his notion of the central concept of ‘habitus’ argued against a too structuralist notion of culture as a system of — largely unbreakable — rules. For an introduction to the ‘performative turn’ see for instance Loxley, Performativity. The Making of New Cultural Landscapes in the Medieval Baltic 137 Thus does Riga always water the nations. Thus did she now water Oesel in the middle of the sea. By washing she purges sin and grants the kingdom of the skies. She furnishes both the higher and lower irrigation. These gifts of God are our delight. The glory of God, of our Lord Jesus Christ, and of our Blessed Virgin Mary gives such joy to His Rigan servants on Oesel!39 A change in the cultural landscape in the minds of the pagans subjugated to baptism would of course be another result. Even if the conversion was forced rather than voluntary,40 it would have grave consequences for the former pagans. One important reason for this was the social status given to the new neophytes. Baptism was indeed a sacrament, but it was also an important legal act and thus a very powerful tool in the hands of the colonizers in the Baltic. Through baptism Christian powers could effectively subjugate the pagans to Christian obligations — the so-called iura christianitatis and all new means of exploitation and suppression. Baptism would place the neophyte in a legal relationship with the local church and the other Christian authorities.41 However, not only the legal status of the former pagans changed through baptism. The baptismal rites would change these people culturally as well. A new cultural awareness of ‘person’ would be the immediate result, whether or not a given individual was forcibly converted and baptized. Through the physical acts involved in the liturgical elements of baptism, a new cultural landscape 39 Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, chap. XXX, 5–6 (p. 245). Henry puns on the Latin verb irrigare and the name of the city Riga, the centre of the German missionary engagement since the 1180s. The chronicler also gives in short form a more concise description of the consequences of baptism for the priests doing the sprinkling, when he writes from the same incident: ‘The priests, therefore, baptized with the greatest devotion many thousands of people, whom they saw rush with the greatest joy to the sacrament of baptism; and they, too, rejoiced, hoping that the work would count for the remission of their sins [my emphasis]. What they could not accomplish on that day, they completed on the next day and the third day’ (p. 244). The Latin text reads: ‘sperantes eundem laborem in suorum remissionem peccatorum’ (Henry of Livonia, Chronicon, ed. by Arbusow and Bauer, p. 336). 40 The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle, trans. by Schmidt and Urban, p. 34, also relates the forced conversion: ‘Many Kurs were killed before the land was conquered, but to break a stubborn habit one has to strike hard. One had to show them both kindness and sternness before they would make the decision to accept baptism, but at last they grudgingly accepted it’. 41 Consequently, it was important for these authorities to know exactly which power the neophytes belonged to — Danish authority, German, or Swedish, or whether the neophytes were subjugated to the authority of the Teutonic Knights. At times there was in fact a fiercely competitive atmosphere between the crusading powers on this issue. See on this issue e.g. Nielsen, ‘Mission and Submission’. Torben Kjersgaard Nielsen 138 would be introduced to — or, rather, forced upon — the neophytes. Regardless of their attitude towards it, a physical act had taken place which affected the persons touched by it. The rites of baptism, the acting out of common, yet singular, rituals towards any one of the neophytes marked out every single one of these pagans as a new ‘someone’ in his own right. A new awareness of body and religious status was thus instated. Consequently, the physical acts of baptism had to be in some way contemplated upon by the neophyte. The newly baptized pagan would have to appropriate the act of baptism in order to make meaning of it. Such appropriation would result in either appreciation or dissociation. Which one of these he chose is not of great importance to this end: my point here is simply that the rite of baptism was important because it could not be undone. The water from the sprinkling would quickly evaporate, but the symbolic effect of the ritual would remain forever. In a very Geertzian way, then, the pure physical act of sprinkling water on the conquered pagans was also to the pagans themselves a symbolic action, establishing lasting, pervasive, and powerful moods in the persons sprinkled upon. Every single baptized pagan would remember afterwards under what circumstances, in which location, and together with whom he had been baptized. And he would have to consider exactly what had happened to him. That such a ‘necessity of appropriation’ holds true for forced conversion in the medieval Baltic is clearly underlined in Henry’s chronicle. He tells us that in times of rebellion against the Christian authorities, the Baltic peoples would actively rid themselves of their Christian baptism through washing and the performance of specific rituals. Following the death in 1198 of Bertold, the second missionary bishop to Riga, Henry writes of the Livonian preparations for war against the Christians: The treacherous Livonians, emerging from their customary baths, poured the water of the Dvina River over themselves, saying: ‘We now remove the water of baptism and Christianity itself with the water of the river. Scrubbing off the faith we have received, we send it after the withdrawing Saxons.’ Those who had gone away had cut the likeness of the head of a man on a branch of a certain tree. The Livonians supposed this to be the god of the Saxons and they believed that it was bringing flood and pestilence upon them. Accordingly, they cooked mead according to the rite, drank it together, and, having taken counsel, took the head from the tree, placed it on logs which they had tied together, and sent it as the god of the Saxons, together with their Christian faith, after those who were going back to Gothland by sea.42 42 Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, chap. II, 8 (p. 34). The Making of New Cultural Landscapes in the Medieval Baltic 139 On a source-critical level we should remark that Henry may have simply misinterpreted the age-old Baltic sauna-traditions. Further, his use of direct speech is nothing but a literary convention to heighten the tension and drama of his narrative. Otherwise, however, the chronicler was very well versed in the local languages,43 and the chance of him making so profound a mistake is, in my view, rather low. We learn of pagan actions in response to Christian baptism from early on in Henry’s chronicle. During the episcopacy of Meinhard (c. 1186–96) the people of the Riga area accepted baptism on the promise that the art of stone masonry would be related to them. The Rigans ‘relapsed’, we learn in the Chronicle, when ‘the fort had at last been finished’. The neighbouring people of Holm made a similar promise, thus ‘cheating’ the missionary bishop. This caused Henry of Livonia to write: The neighboring people of Holm cheated Meinhard by making a similar promise. After a fort had been built for them, they profited from their fraud. […] Between the construction of the two above-mentioned forts, Meinhard was consecrated bishop by the metropolitan of Bremen. After the second fort had been completed, in their iniquity they forgot their oath and perjured themselves, for there was not even one of them who accepted the faith. Truly the soul of the preacher was disturbed, inasmuch as, by gradually plundering his possessions and beating his household, they decided to drive him outside their borders. They thought that since they had been baptized with water, they could remove their baptism by washing themselves in the Dvina and thus send it back to Germany.44 After a great rebellion in 1223 which affected most of the Baltic, Henry relates, the people of Ösel very consciously played out specific rituals or liturgies as a preparation for war against the Christian authorities: Then word went out through all of Esthonia and Oesel to fight against the Danes and the Germans. They cast the Christian name out of all of their territories. They called upon the Russians from Novgorod and Pskov to help them. They made peace with the Russians and placed some of them in Dorpat, some in Fellin, and others in other forts to fight against the Germans and Latins and all the Christians. […] They took back their wives, who had been sent away during the Christian period. They disinterred the bodies of their dead, who had been buried in cemeteries, and cremated them according to their original pagan custom. They washed themselves, 43 Henry appears as an interpreter on several occasions in his own chronicle, e.g. Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, p. 126. Cf. also the Introduction, pp. xxvi–xxvii. 44 Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, chap. I, 7 (p. 27). Torben Kjersgaard Nielsen 140 their houses, and their forts with brooms and water, trying thus to erase the sacrament of baptism in their territory.45 As stated above, there is no reason to understate the important legal consequences of the baptismal liturgies for the conquered peoples. These they would meet in everyday life, when struggling to meet demands for taxes and levies claimed by the new Christian authorities. The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle discloses very clearly that it was not only the care for pagan souls that drove the Christians. One example will suffice: Master Andreas von Stierland decided to no longer keep peace with the heathens. He said, ‘Lord God, Your strength has stood by me well, but I shall never be free of worry until You grant me and the other Christians success in conquering the ancestral lands of the heathens. I have no concern for my own life’.46 That the former pagans would have to try to interpret the ritualistic elements of the baptism as well, so as to conceive what had happened to them, strikes me as logical and sensible. The central premise of this article, that religion was the primary epistemological system available to medieval man, makes good sense of the pagan use of water to cleanse and revoke the Christian water-ritual, baptism.47 The pagans could have chosen to consider Christian baptism a strange ritual without importance to them. But they did not. Through sprinkling and the other rites of baptism, the individual indeed became charged with a new religious meaning. What was intended by the Christians to be understood as an act of symbolic value and importance was apparently also understood as such by the pagans. Even the initiation rites of baptism — superficial and drastically shortened as they were compared to ideal Christian standards and the prescribed liturgies from apostolic times — were perceived by the pagans as a symbol of Christian victory, even if temporary. Coincident with the fact that even the prefatory rituals of baptism were an important symbol of defeat with effects for the whole pagan community, the initiation of baptism also singled out every pagan individual as a target for the 45 Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, chap. XXVI, 8 (p. 210). From a strict source-critical point of view, Henry of course would have been in no real position to know exactly either whether the apostates from Ösel actually performed the rituals mentioned by him, or whether his interpretation of these rituals would be congruent with the interpretation given by the apostates, who allegedly performed the rituals. 46 The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle, trans. by Schmidt and Urban, p. 47. 47 What strengthens the argument is that water is a very strong apotropaic remedy in many societies and in many religions. The Making of New Cultural Landscapes in the Medieval Baltic 141 sacrament by water. That the Christian actions had this consequence became obvious precisely in times of insurgency, when the effects of (preliminary) baptism had to be wiped away in a conscious — and again ritualistic — effort to religiously dissociate from the new religion. De-sacralization of Pagan Religious and Social Landscape Besides the sacralization of a religious landscape in the minds of the former pagans through baptism and instruction in the faith, another distinctive feature also took place when introducing Christianity to the Baltic. This feature I will term a de-sacralization of the pagan cultural landscape. This has already been hinted at above, but I shall be a bit more specific. If sacralization, as in the cases above, would mean ensuring changes by establishing new ways of thinking and reacting, then the term de-sacralization signals not the building up of something new but rather the destruction of something already existing. However, if the sacralization discussed above can be said to have been both religious and ritualistic, presenting both communal and personal consequences, so can also the acts of de-sacralization. I shall consider two examples of de-sacralization: the first is religious and cultic, with implications for the pagan individuals in their beliefs, while the second is decidedly social, having implications for pagan society at large. The pagans of the Baltic worshipped a number of different gods and lower deities, each with different attributes and powers who would populate the many groves and forests and at times be called upon for protection, to foretell the future or to decide in matters of public interest.48 This would include specific rituals as when in 1211 during a siege, a pagan sacrifice ritual apparently resulted in a bad omen: After this the Esthonians sent some of their younger and stronger men through the province to despoil the land. They burned villages and churches, seized and killed some of the Livonians and took others prisoners, took many spoils, drove the cattle and other livestock to their base, and slaughtered the cattle and livestock, immolating them to their gods, whose favor they sought. But the flesh which they cut off fell on the left side, which indicated that their gods were displeased: this was a sinister omen.49 48 For Baltic pre-Christian religion see Gimbutas, ‘The Pre-Christian Religion of Lithuania’, and the literature therein. 49 Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, chap. XV, 3 (p. 110). Torben Kjersgaard Nielsen 142 Consequently,50 we learn in Henry’s Chronicle, the pagans lost the ensuing battle. On another occasion in the following year, we read about a siege of the pagan leader Dobrel’s fort in Treiden: The Germans destroyed the ramparts of the fort and killed many men and beasts with the many large rocks which they shot into the fort with their paterells. Some forced the Livonians from the defenses with arrows, wounding a great many of them. Others put up a tower, which the wind knocked to the ground the next night. At this there was great noise and rejoicing in the fort and the Livonians sacrificed animals, paying honor to their gods according to their old customs. They immolated dogs and goats and, to mock Christianity, they tossed them from the fort, in the face of the bishop and the whole army.51 If we are to believe our written sources, paganism in the Baltic also included ritual killings of the enemy. The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle tells of some of the Brothers of the Teutonic Order, who defended themselves well but were eventually vanquished. The Semgallians had their way and soon after they held a tribunal. They all stood around in a wide circle and would force a Brother into the ring where he was hacked to pieces.52 Henry of Livonia, by contrast, focuses on the casualties among the merchants and the priests when relating stories of Christian martyrdom and cruel paganism. Using biblical imagery and quotations, Henry depicts the pagan Estonians rebelling in 1223 against Christian authority: After a long delay, peace was at last sworn to and the Brothers went out, one by one, to the Saccalians. The traitors at once seized them, cast them into shackles and chains, and pillaged their money, horses, and all their goods, which they divided among themselves. They threw the bodies of the slain in the fields, to be gnawed at by the dogs, as it is written, ‘They have thrown the corpses of Thy servants to feed the birds of heaven; the flesh of thy saints for the beast of the earth; their blood 50 Interestingly, the chronicles of the Baltic offer numerous examples that their Christian authors admitted at least some sort of demonic power to the pagan gods. See Mazeika, ‘Granting Power to Enemy Gods’. 51 Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, chap. XVI, 4 (p. 127). Apparently, this is to be understood quite literally: The animals were tossed ‘ad illusionem christianorum in faciam episcopi et tocius exercitus’, the text says in Latin (Henry of Livonia, Chronicon, ed. by Arbusow and Bauer, p. 158). 52 The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle, trans. by Schmidt and Urban, p. 107. See also pp. 63 and 73, where we learn that some of the Brothers ‘were brutally seized and every precaution was made to prevent their escape. A fire was built, and some of the Brothers were roasted in it while others were hacked to bits’. The Making of New Cultural Landscapes in the Medieval Baltic 143 has flowed like water, and there was none to bury the dead.’ Certain of them went to another fort which was by the Pala and there ordered similar things to be done. On the road they killed their priest and others. After this the Saccalians went into Jerwan. There they seized the magistrate, Hebbus, and brought him with the other Danes back to their fort and tormented him and the others with a cruel martyrdom. They tore out their viscera and plucked out Hebbus’ heart from his bosom while he was still alive. They roasted it in the fire, divided it among themselves, and ate it, so that they would be made strong against the Christians.53 Such pagan practice could of course not be tolerated and the Christians would have to work to eliminate it. One of the means to achieve this was to beat the pagans in battle: then they would recognize the power of the Christian God. At least, we often find this thought in the written sources. In an especially interesting chapter, Henry depicts Livonia, in unusual and dramatic language, as ‘the land of the Mother’, who has caused many enemies of the Christian cause to perish: Behold how the Mother of God, so gentle to Her people who serve Her faithfully in Livonia, always defended them from all their enemies and how harsh She is with those who invade Her land or who try to hinder the faith and honor of Her Son in that land! See how many kings, and how mighty, She has afflicted! See how many princes and elders of treacherous pagans She has wiped off the earth and how often She has given Her people victory over the enemy! Up to this time, indeed, She has always defended Her banner in Livonia, both preceding it and following it, and She has made it triumph over the enemy.54 Another measure was to de-sacralize paganism itself. This measure was employed by the Christian priests sent out to baptize and perform missionary work. Not only did they teach the new faith: they also proved the utter uselessness of the old religion. A Cistercian monk and later abbot of Dünamunde, 53 Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, chap. XXVI, 6 (pp. 208–09). See also chap. X, 5 (p. 57), where Henry relates the story of two converts, Kyrian and Layan, who fell victim to a conspiracy that cost them their lives: ‘When they entered the meeting they were immediately taken by the elders, who attempted to force them to put off the Christian faith and to renounce the Germans. Constant in the love of God, they confessed that they had embraced the faith they had received with all devotion and affirmed that no kind of torture could separate them from the love and society of Christians. Because of this, naturally, the hatred even of their kinsmen grew so great against them that henceforth this hatred was greater than the love which they had previously felt. Thus it was that by a conspiracy of all the Livonians their feet were bound by ropes and they were cut through the middle. They afflicted them with most cruel punishments, tore out their viscera and cut off their arms and legs. There is no doubt that they received eternal life with the holy martyrs for such a martyrdom’. 54 Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, chap. XXV, 2 (p. 199). Torben Kjersgaard Nielsen 144 Theoderich, was at one point approached by a wounded Livonian, who begged him for a cure, promising to be baptized if Theoderich could rescue him. In Henry’s Chronicle we learn that Theoderich rescued the man, not with the help of the herbs he simply pounded together without knowing their effect but only by the prayers he sent to God: ‘The Livonian was thus healed in body and, by baptism, in soul’.55 We also read of the priest Daniel, who was sent to preach to the people of Lennewarden. When he had called the people together to hear the Word of God, a Livonian came forward from ‘his hiding places in the forests’ to tell the priest of a vision: I saw the god of the Livonians, who foretold the future to us. He was, indeed, an image growing out of a tree from the breast upwards, and he told that a Lithuanian army would come tomorrow; and for fear of that army we dare not assemble. Daniel, being the level-headed Christian priest and missionary that he was, of course, quickly realized that this was ‘an illusion of the devil, because at this time of autumn there was no road by which the Lithuanians could come’, and continued in his prayers: When, in the morning, they heard or saw nothing that the Livonian’s phantom had foretold, they all came together. The priest then execrated their idolatry and affirmed that a phantom of this kind was an illusion of the demons. He preached that there was one God, creator of all, one faith, and one baptism, and in this and in similar ways invited them to the worship of the one God. After hearing these things, they renounced the devil and his works, promised to believe in God, and those who were predestined by God were baptized.56 The Christian priests and missionaries would work by their own example and actions to prove the worthlessness of the pagan beliefs. They might incur martyrdom by doing so, but they might also succeed in convincing the pagans of the powers inherent in the Christian God. From 1220 Henry of Livonia gives a story of German priests destroying a pagan holy place. In this place, located in what is depicted sympathetically by Henry as a ‘lovely forest’, the priests had found figures of woodcut, probably depictions of a pagan pantheon: 55 Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, chap. I, 10 (p. 28). Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, chap. X, 14 (p. 66). The last part of the Latin text reads: ‘tandem unum Deum, creatorem omnium, unam fidem, unum baptisma [Cf. Ephesians 4. 5] esse predicat et hiis et aliis similibus ad culturam unius Dei eos invitat. Hiis auditis diabolo et operibus eius abrenunciant et in Deum credere se promittunt et baptizantur, quotquot predestinati erant [Cf. Acts 13. 48] a Deo’ (Henry of Livonia, Chronicon, ed. by Arbusow and Bauer, p. 64). 56 The Making of New Cultural Landscapes in the Medieval Baltic 145 There was there a mountain and a most lovely forest in which, the natives say, the great god of the Oesilians, called Tharapita, was born, and from which he flew to Oesel. The other priest went and cut down the images and likenesses which had been made there of their gods. The natives wondered greatly that blood did not flow and they believed the more in the priests’ sermons.57 That the natives would have expected the flow of blood is very probable, given their specific ideas of the meaning of this place beforehand. Following the words of Stefan Brink, the natives would clearly have had an idea of the forest as a numinous place. Brink states that a ‘sacred grove, well, lake, river or mountain could therefore be a place or an area (i) where one might sacrifice to the gods, that is, a cult site, (ii) where one could have a closer contact with gods or ancestors, and where one might perform rituals, (iii) where one might receive godly power or be spiritually charged, for example, with holy water or under a sacred tree, (iv) which was dedicated to some god, because you were one of his or her people or so that he or she might protect you or (v) where you might be given an (sacrally sanctioned) asylum or protection’.58 If this is true, the devastation of the pagan site would surely have been a terrifying experience to witness. In direct connection to this destruction, the priests succeeded in their campaign of baptism and conversion. They continued on to a number of small villages in the region surrounding Lake Virtsjärv and ‘consummated the mysteries of holy Baptism’ to hundreds of men, women, and children, thus wiping out pagan worship.59 57 Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, chap. XXIV, 5 (pp. 193–94). It could be that the story from 1203 of the two priests, John of Vechta and Volhard of Harptstedt, who together with pilgrims were ‘cutting down trees next to the Old Mountain’ before being seized and killed by a Russian petty prince, Vetseke, is another story of destruction of pagan holy sites. Cf. Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, chap. VII, 9 (p. 44). 58 Brink, ‘Mythologizing Landscape’, p. 81. 59 Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, chap. XXIV, 5 (p. 194). The Latin text reads: ‘et similiter ebdomadam ibidem implentes circumiverunt ad villas et quolibet die circiter trecentos aut quingentos promiscui sexus baptizaverunt, donec eciam in illis finibus consumato baptismate paganorum ritus abolerent’ (Henry of Livonia, Chronicon, ed. by Arbusow and Bauer, pp. 262–64). These are of course well known hagiographical themes of sufferings and successes, and it is true that some of the stories in Henry’s Chronicle could be perceived as laying the groundwork for a later cult of the martyrs involved. Cf. e.g. Henry’s story of the converted pagan leader, Caupo, which ends in Caupo’s death by a lance (!) and his syncretistic burial (Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, chap. XXI, 4 (p. 163)), or the stories of the martyred converts Kyrian and Layan (related above), whose bodies we are told ‘rest in the church of Uexküll and are beside the tombs of the bishops Meinhard and Bertold, of whom 146 Torben Kjersgaard Nielsen Another efficient way of de-sacralizing paganism would be to attack the social sphere of pagan society. In the written sources, stories of hostage-taking and abduction of children and women abound. Abducting women and children was a military strategy very well known to both the Christian crusaders and the pagan tribes. The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle says: From among his own subjects Master Volkwin recruited an army and led it to Wiek, passing through many bad places until they came to their goal. He took hostages from the natives and they gave them to him without resistance on the condition that he withdrew his army. This he did and then returned home a very happy man. When the Estonians heard of this they assembled and said: Alas, shall the crusaders drive us from our ancestral homes with the help of the Livs and Letts? Let us defend ourselves and raise an army larger than ever before raised from Estonia and drive them back over the seas so that they can never again return and oppress us. And if we win glory in battle from the Livs and Letts, who are now allies of the Germans, we shall capture their women and children and carry them home with us.60 The idea behind such strategies of war was probably the same, whether the abductors were pagans or Christians: Abducting women and children would effectively put an end to existing tribal dynasties. Henry of Livonia relates how the women and children were spared after battle, but held captive, some of them even sent to Germany.61 It was common practice among the Livonian and Estonian pagan widows simply to remarry the brother of their deceased husbands, i.e., the original brother-in-law.62 By marrying her brother-in-law, the widow would pass on the lineage of her husband to coming generations. Thus, by abducting the females of a pagan village, the existing pagan kin lines would be dealt a heavy blow. It was not only that the widows remarried. Apparently, some of the pagans practised male polygamy — or simply violated the women captured. Henry writes of the ‘infamous’ Ösilians: the first was a confessor and the second a martyr who, as is related above, was killed by the same Livonians’ (chap. X, 6 (p. 57)). Cf. also the story of the martyrdom of John the priest, who had his head cut off and the rest of his body cut to pieces by the pagans from Holm before being buried in the Church of Blessed Mary in Riga (chap. X, 7 (p. 58)). The cleaning of the ‘mountain’ in Kukenois (Latv.) for ‘snakes and worms’ because of the ‘filthiness of the former inhabitants’ also has a ring to it of cultic purging (chap. XIII, 1 (p. 88)). 60 The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle, trans. by Schmidt and Urban, p. 14. 61 Cf. for instance Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, chap. XII, 6 (p. 86) and chap. XV, 2 (p. 109). 62 What is hinted at is the so-called Levirate marriage. A letter from Pope Innocent III from 1201 actually discusses this custom in the Baltic. Cf. Nielsen, ‘Mission and Submission’, p. 222. The Making of New Cultural Landscapes in the Medieval Baltic 147 The Oesilians were accustomed to visit many hardships and villainies upon their captives, both the young women and virgins, at all times, by violating them and taking them as wives, each taking two or three or more of them. They allowed themselves these unlawful actions, though it is not right that Christ be joined with Belial, nor is it suitable for a pagan to be joined to a Christian. The Oesilians were even accustomed to sell the women to the Kurs and other pagans.63 We can understand in the same way the apparent counter-measure of the fifty women from Lithuania, of whom we learn from Henry that they had hanged themselves because of the deaths of their husbands, believing without doubt that they would rejoin them immediately in the other life.64 Suicide, out of either defiance or shame, is also mentioned with male pagans, even if the reasons for this apparently collective action offered by Henry in the passage below appear illogical: Since it was now winter, the Lithuanians who escaped through the woods, because of the difficulty of crossing the Dvina, either drowned in the Dvina or hanged themselves in the woods, that they might not return to their own land. For they had despoiled the Blessed Virgin’s land and Her Son returned vengeance against them. To Him be praise throughout the ages.65 Perhaps Henry’s story from 1210 of the ritual killing of fellow pagan tribesmen must also be understood as an attempt to resist the de-sacralization of paganism wrought upon these societies by the Christian crusaders. Henry states, in his account of a pagan attack on the city of Riga, that when the pagans heard the sound of the great bell, they said they were being eaten and consumed by the God of the Christians, and, approaching the city again, fought through the whole day. When they came out from under their shields in order to bring up wood for burning the fort, many of them were wounded by arrows and when any of their men fell, wounded by the stones of the machines or by the ballistarii, immediately his brother or some other companion killed him by cutting off his head.66 63 Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, chap. XXX, 1 (p. 238). Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, chap. IX, 5 (p. 50). 65 Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, chap. XXV, 4 (p. 203). 66 Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle, trans. by Brundage, chap. XIV, 5 (p. 98). 64 Torben Kjersgaard Nielsen 148 The End: Sacralization, De-sacralization, Neo-memorialization In this article, I have argued that deliberate actions, such as violent Christianization and ritual sprinkling of water in baptism, destruction of pagan holy sites, as well as warfare and the deliberate abduction of women and children, caused rapid changes in the conceptualizations of the physical landscape, of body and identity, and of social order. Described in this way, Christianization had grave consequences for the Baltic peoples, who must have had to work hard to make sense of these violent changes of life and society. In doing so, they themselves appropriated these changes, either through resistance or through acknowledgement. Such appropriation would have had consequences in itself, regardless of the way it was expressed and lived out. Stefan Brink has noted that (physical) ‘landscape is history’.67 I would expand his point to include the whole of the cultural landscape, as I have tried to delimit it in this article. A cultural landscape also involves important relations both backwards and forwards in time, since it includes notions of history and memory.68 Memories of past experiences and phenomena give meaning to the present and offer guidelines for the future. Thus, any appropriation of profound changes in society and person will affect history and memory as well. Memory was tightly connected to structures and behaviours in the cultural landscapes of the Baltic. In a recent article, the Estonian historian Dr Marek Tamm discusses such issues in his effort to understand what modern Estonians remember of their past. His notions strike me as being of direct relevance to our own discussion. He writes: ‘Cultural memory works by reconstructing,’ writes Jan Assmann, ‘that is, it always relates its knowledge to an actual and contemporary situation’. But cultural memory, as noted by Rudy Koshar among others, is also ritualistic and performative. It derives its motive force not only from constant ‘construction’ and ‘invention’, but also from the repetition of culturally specific bodily practices associated with commemorations, demonstrations and other ritual activities. Also, Paul Connerton has pointed out that a nation’s master narrative is ‘more than a story told and reflected 67 Brink, ‘Mythologizing Landscape’, p. 83. The relationship between history and memory is of course a huge and important subject to which important contributions have been delivered by scholars such as Maurice Halbwachs, Norbert Elias, Pierre Nora, Zygmunt Baumann, Eric Hobsbawm, David Loewenthal, Jan Assmann, Aleida Assmann, Peter Burke, Homi H. K. Bhabha, Rudy Koshar, and Jeffrey K. Olick, who have approached this vast area from different angles and perspectives. For a short but pithy discussion of memory and society see Connerton, How Societies Remember. 68 The Making of New Cultural Landscapes in the Medieval Baltic 149 on; it is a cult enacted. An image of the past, even in the form of a master narrative, is conveyed and sustained by ritual performances.69 The Baltic peoples had to construct their past anew through newly developed ritualistic performances, mirroring the changes that had taken place. They found new ways to commemorate their (new) past in light of Christianization and the consequent changes to pagan society. The violent de-sacralization of the Baltic pagan cultural landscape was in this sense also a process of de-memo­ rialization or, rather, of re-memorialization. This is one of the main reasons why Christianity prevailed in the end. Besides the political power play and prowess in battle, the Christians were keen to destroy the extant symbols of paganism and to disrupt the cultural landscapes and mindsets upon which these societies were grounded. The Baltic peoples necessarily had to appropriate these disruptions in order to make sense of life. Perhaps this is the real content of the report from Danish archbishop Anders Sunesen to Pope Innocent III in 1207: With the successful crusading efforts by Scandinavian and German forces, Christianity had taken root in the Baltic. This was so, because the Crusades in the Baltic were intimately accompanied by conscious actions to convert the pagans. Through a ritualistic practice of mass baptism and destruction of pagan cult sites, Christianity put its mark on the population, who on their part had to reflect upon this, if not react against it. Perhaps, then, Anders’s report spoke the truth, when he claimed that the whole of Livonia had been converted: the necessary prerequisite for a conversion, that is, a radical change in the cultural landscape, had begun. 69 Tamm, ‘History as Cultural Memory’, pp. 508–09. I have omitted Tamm’s references in the quotation. They are given here: Assmann, ‘Collective Memory and Cultural Identity’, p. 130; Koshar, From Monuments to Traces, p. 8; Connerton, How Societies Remember, p. 70; Burke, ‘Performing History’; Burke, ‘Co-memorations: Performing the Past’. 150 Torben Kjersgaard Nielsen Works Cited Primary Sources The Deeds of Innocent III by an Anonymous Author, trans. by James M. Powell (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2004) Henry of Livonia, The Chronicle of Henry of Livonia: Heinricus Lettus, trans. by James A. Brundage (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003) —— , Heinrici Chronicon Livoniae, ed. by Leonid Arbusow and Albert Bauer (Würzburg: Holzner, 1959) Livländische Reimchronik: mit Anmerkungen, Namenverzeichnis und Glossar, ed. by Leo Meyer (Paderborn: Schöningh, 1876) The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle, trans. by Jerry C. Schmidt and William Urban (Bloom­ ing­ton: Indiana University Press, 1977) Secondary Studies Arbusow, Leonid, ‘Ein verschollener Bericht des Erzbischofs Andreas von Lund aus dem Jahre 1207 über die Bekehrung Livlands’, Sitzungsberichte der Gesellschaft für Geschichte und Altertumskunde der Ostseeprovinzen Russlands aus dem Jahre 1910 (1911), 4–6 Assmann, Jan, ‘Collective Memory and Cultural Identity’, New German Critique, 65 (1995), 125–33 Bartlett, Robert, ‘The Conversion of a Pagan Society in the Middle Ages’, History, 70 (1985), 185–201 Bender, Barbara, ‘Introduction’, in Landscape: Politics and Perspectives, ed. by Barbara Bender (Oxford: Berg, 1993), pp. 1–17 —— , ‘Time and Landscape’, Current Anthropology, 43 (2002), 103–12 Blomkvist, Niels, The Discovery of the Baltic: The Reception of a Catholic World-System in the European North (ad 1075–1225), The Northern World, 15 (Leiden: Brill, 2005) Bolton, Brenda, Innocent III: Studies on Papal Authority and Pastoral Care (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1995) Brereton, Joel P., ‘Sacred Space’, in Encyclopedia of Religion, ed. by Mircea Eliade and others, 16 vols (New York: Collier Macmillan, 1987), xii: PROC– SAIC, pp. 526–35 Brink, Stefan, ‘Mythologizing Landscape: Place and Space of Cult and Myths’, in Kon­ tinuitäten und Brüche in der Religionsgeschichte: Festschrift für Anders Hultgård zu seinem 65. Geburtstag am 23.12.2001, ed. by Michael Stausberg, Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde, 31 (Berlin: Gruyter, 2001), pp. 76–112 Burke, Peter, ‘Co-memorations: Performing the Past’, in Performing the Past: Memory, History, and Identity in Modern Europe, ed. by Karin Tilmans, Frank van Vree, and Jay Winter (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2010), pp. 105–18 —— , ‘Performing History: The Importance of Occasions’, Rethinking History, 9 (2005), 35–52 The Making of New Cultural Landscapes in the Medieval Baltic 151 Christiansen, Eric, The Northern Crusades (London: Penguin, 1980; repr. 1997) Connerton, Paul, How Societies Remember (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989) Davis, Natalie Zemon, ‘Clifford Geertz on Time and Change’, in Clifford Geertz by his Colleagues, ed. by Richard A. Schweder and Byron Good (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), pp. 38–44 Eliade, Mircea, Sacred and Profane: The Nature of Religion (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1957) Fonnesberg-Schmidt, Iben, The Popes and the Baltic Crusades, 1147–1254 (Leiden: Brill, 2007) Fowler, P. J., World Heritage Cultural Landscapes, 1992–2002, World Heritage Papers 6, UNESCO World Heritage Center, Paris 2003 <http://whc.unesco.org/en/series/6/> [accessed 17 July 2008] Geertz, Clifford, The Interpretation of Cultures (New York: Basic, 1973) Gimbutas, Marija, ‘The Pre-Christian Religion of Lithuania’, in La Cristianizzazione della Lituania: atti del colloquio internazionale di storia ecclesiastica in occasione del VI centenario della Lituania cristiana (1387–1987), ed. by Paulius Rabikauskas (Città del Vaticano: Libreria editrice vaticana, 1989), pp. 13–25 Hamilton, Sarah, and Andrew Spicer, ‘Defining the Holy: The Delineation of Sacred Space’, in Defining the Holy: Sacred Space in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, ed. by Sarah Hamilton and Andrew Spicer (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005), pp. 1–23 Howe, John M., ‘The Conversion of the Physical World: The Creation of a Christian Landscape’, in Varieties of Religious Conversion in the Middle Ages, ed. by James Muldoon (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1997), pp. 63–80 —— , ‘Creating Symbolic Landscapes: Medieval Development of Sacred Space’, in Inventing Medieval Landscapes: Senses of Place in Western Europe, ed. by John M. Howe and Michael Wolfe (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002), pp. 208–23 Jensen, Carsten Selch, ‘How to Convert a Landscape: Henry of Livonia and the Chronicon Livoniae’, in The Clash of Culture on the Baltic Frontier, ed. by Alan V. Murray (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2009), pp. 151–68 Jensen, Kurt Villads, ‘Crusading and Christian Penetration into the Landscape: The New Jerusalem in the Desert’, in Sacred Sites and Holy Places: Exploring the Sacralization of Landscape through Time and Space, ed. by Stefan Brink and Sæbjørg Walaker Nordeide, Studies in the Early Middle Ages, 11 (Turnhout: Brepols, forthcoming) Kala, Tiina, ‘The Incorporation of the Northern Baltic Lands into the Western Christian World’, in Crusade and Conversion on the Batic Frontier, ed. by Alan V. Murray (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2001), pp. 3–20 Koshar, Rudy, From Monuments to Traces: Artifacts of German Memory, 1870–1990 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000) Krause-Jensen, Jakob, ‘Clifford Geertz: Thick Description, New York 1973’, in Antropologiske mesterværker, ed. by Ole Høiriis (Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 2007), pp. 245–56 Langenbahn, S. K., ‘Taufritus’, in Lexikon des Mittelalters, ed. by Robert Auty and others, 9 vols (Zürich: Artemis & Winkler, 1977–99), viii: Stadt (Byzantinisches Reich)– Werl (1997), col. 500 152 Torben Kjersgaard Nielsen Lind, John, ‘Sword Brethren’, in The Crusades: An Encyclopedia, ed. by Alan V. Murray, 4 vols (Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio, 2006), iv, 1130–35 —— , and others, eds, Danske korstog: Krig og mission i Østersøen (København: Høst, 2004) Loxley, James, Performativity (London: Routledge, 2006) Mägi, Marika, ‘From Paganism to Christianity: Political Changes and their Reflection in the Burial Customs of Twelfth and Thirteenth Century Saaremaa’, in Der Ostseeraum und Kontinentaleuropa 1100–1600: Einflußrahme – Rezeption – Wandel, ed. by Detlef Kattinger, Jens E. Olesen, and Horst Wernicke, Culture Clash or Compromise, 7 (Schwerin: Helms, 2004), pp. 27–34 Markus, R. A., ‘How on Earth Could Places Become Holy? Origins of the Christian Ideas of Holy Places’, Journal of Early Christian Studies, 2 (1994), 257–71 Mazeika, Raza, ‘Granting Power to Enemy Gods in the Chronicles of the Baltic Crusades’, in Medieval Frontiers: Concepts and Practices, ed. by David Abulafia and Nora Berend (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002), pp. 153–72 Murray, Alan V., ‘The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle’, in Encyclopedia of the Crusades, ed. by Alan V. Murray (Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio, 2006), iii, 753, col. 2 —— , ed., Crusade and Conversion on the Baltic Frontier (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2001) Nielsen, Torben Kjersgaard, ‘Henry of Livonia’, in The Crusades: An Encyclopedia, ed. by Alan V. Murray, 4 vols (Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio, 2006), ii, 575–76 —— , ‘Henry of Livonia on Woods and Wilderness’, in Crusading and Chronicle Writing on the Medieval Baltic Frontier, ed. by Linda Kaljundi, Marek Tamm, and Carsten Selch Jensen (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2010), pp. 157–78 —— , ‘Mission and Submission: Societal Change in the Baltic in the Thirteenth Century’, in Medieval History Writing and Crusading Ideology, ed. by Tuomas M. S. Lehtonen and Kurt Villads Jensen (Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2005), pp. 216–31 Nyberg, Tore, ‘The Danish Church and Mission in Estonia’, Nordeuropa-Forum: Zeitschrift für Politik, Wirtschaft und Kultur, 1 (1998), 49–72 Rowell, S. C., Lithuania Ascending: A Pagan Empire within East-Central Europe, 1295–1345 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994) Rowntree, Lester B., ‘The Cultural Landscape Concept in American Human Geography’, in Concepts in Human Geography, ed. by Carvill Earle, Kent Mathewson, and Martin S. Kenzer (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 1996), pp. 127–59 Scheffczyk, L., ‘Taufe’, in Lexikon des Mittelalters, ed. by Robert Auty and others, 9 vols (Zürich: Artemis & Winkler, 1977–99), viii: Stadt (Byzantinisches Reich)–Werl (1997), cols 495–98 Staecker, Jörn, ‘In atrio ecclesiae: Die Bestattungssitte der dörflichen und städtischen Friedhöfe im Norden’, in Lübeck Style? Novgorod Style? Baltic Rim Central Places as Arenas for Cultural Encounters and Urbanisation, 1100–1400 ad: Transactions of the Central Level Symposium of the Culture Clash or Compromise (CCC) Project Held in Talsi September 18–21, 1998, ed. by Muntis Auns (Riga: Nordik, 2001), pp. 187–258 Steinsland, Gro, Det hellige bryllup og norrøn kongeideologi: en analyse av hierogami-myten i Skírnismál, Ynglingatal, Háleyg jatal og Hyndluljóð (Oslo: Solum, 1991) The Making of New Cultural Landscapes in the Medieval Baltic 153 —— , Den hellige kongen: om religion og herskemakt fra vikingtid til middelalder (Oslo: Pax, 2000) Tamm, Marek, ‘History as Cultural Memory: Mnemohistory and the Construction of the Estonian Nation’, Journal of Baltic Studies, 39 (2008), 499–516 UNESCO, ‘Operational Guideline for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention’, UNESCO World Heritage Center, Paris, 2008 <http://whc.unesco. org/archive/opguide08-en.pdf> [accessed 17 July 2008] Urbanczyk, Przemyslav, ‘The Politics of Conversion in North Central Europe’, in The Cross Goes North: Processes of Conversion in Northern Europe, ad 300–1300, ed. by Martin Carver (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2004), pp. 15–27 Valk, Heiki, ‘Christian and non-Christian Holy Sites in Medieval Estonia: A Reflection of Ecclesiastical Attitudes towards Popular Religion’, in The European Frontier: Clashes and Compromises in the Middle Ages, ed. by Jörn Staecker (Lund: Almqvist & Wiksell, 2004), pp. 299–310 Werblowsky, R. J. Zwi, ‘Introduction: Mindscape and Landscape’, in Sacred Space: Shrine, City, Land, ed. by Benjamin Z. Kedar and R. J. Zwi Werblowski (New York: New York University Press, 1996), pp. 9–17 The Emerging Birgittine Movement and the First Steps towards the Canonization of Saint Birgitta of Sweden Claes Gejrot T aking its starting point from the fact that St Birgitta’s fame, ideas, and monastic order were spread throughout late medieval Europe, this essay aims to analyse documentary source material from the 1370s emanating from a circle of ecclesiastical and secular leaders who helped the growing Birgittine movement in its initial phase. The first section will throw light upon the initial hardships suffered by the young monastic institution and present evidence of the alleviating efforts of friends and noblemen. The following section will show how two bishops, both authors of officia for Birgitta, played leading roles in her canonization. A highly rhetorical supplication for her canonization will be examined, and its origin discussed. Further supplications issued by international leaders, Queen Giovanna of Naples and the German emperor Charles IV, will be shown to resemble that of the Swedish bishops. The efforts made by King Albrekt of Sweden will also be discussed, as will national and international requests for miracle collections. Introduction The European late Middle Ages saw at least one easily distinguished set of religious and cultural ideas and values being imported from Scandinavia: Birgitta Claes Gejrot (claes.gejrot@riksarkivet.se) is editor-in-chief of the national Swedish charters edition series, Diplomatarium Suecanum, at Riksarkivet, Stockholm. He is also Associate Professor of Latin at Stockholms Universitet. Medieval Christianity in the North: New Studies, ed. by Kirsi Salonen, Kurt Villads Jensen, and Torstein Jørgensen, AS 1 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013) pp. 155–180 BREPOLS PUBLISHERS 10.1484/M.AS-EB.1.100815 Claes Gejrot 156 Birgersdotter (1303–73), a Swedish noblewoman, was the author of a series of ‘divine revelations’ that circulated her views on spiritual as well as secular matters.1 She founded a new monastic order, which eventually spread to a number of countries. Around 1500, twenty-five Birgittine monasteries had been established, for instance in northern Germany, Bavaria, Poland, Estonia, Italy, and England.2 She was canonized by Pope Boniface IX (r. 1389–1404) in 1391, and in 1999 Pope John Paul II (r. 1978–2005) chose Birgitta as one of the patron saints of Europe. The realization of the first monastic building plans at the ‘mother’ monastery, Vadstena in the Swedish province of Östergötland, and the setting in motion of Birgitta’s canonization, required the active support of ecclesiastical and secular leaders. The present article aims primarily to describe the national and international efforts made in the 1370s, and it will take a closer look at the roles played by some of the main characters. Possible links between influential groups in Sweden and various European leaders will be discussed. Several sources contribute to our knowledge of the background. Texts like miracle narrations and the canonization acts themselves are of course important, and these have been edited and discussed by previous scholars.3 This article, however, will concentrate on the charters and letters preserved from the period, not least the supplications to the pope. The relevant documents from these years will be analysed, and they form the basis of our investigation.4 We will start by looking at the situation in Vadstena, the location that Birgitta herself chose for materializing her monastic ideas, having secured royal donations in the 1340s, just before her departure for Rome.5 After this, 1 For a survey (in English) of Birgitta Birgersdotter’s biography and works see Morris, St Birgitta of Sweden (including a full bibliography for further reading). 2 Strictly speaking the Birgittine ‘Order of Saint Saviour’, Ordo sancti(ssimi) Salvatoris, became a branch of the Augustinian order. On the early development of the order see Höjer, Studier i Vadstena klosters och birgittinordens historia, and Nyberg, Birgittinische Klostergründungen des Mittelalters. The later diffusion of the Birgittines is related in Olsen, ‘Birgittinorden och dess grenar’. 3 For example, the edition in Acta et processus canonizacionis beate Birgitte, ed. by Collijn. For a presentation of these sources see Fröjmark, Mirakler och helgonkult (with further references); and Morris, St Birgitta of Sweden, pp. 143–52. 4 The Swedish charters of the period 1371–77 are edited in Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, x. 1–xi. 3 (1970–2011). 5 On King Magnus Eriksson’s and Queen Blanka’s ample testamentary gifts for the future monastery, see Fritz, 600 år i Vadstena, ed. by Söderström, pp. 62–69. On the oldest history of Vadstena Abbey in general, see Höjer, Studier i Vadstena klosters och birgittinordens historia, The Birgittine Movement & the Canonization of St Birgitta of Sweden 157 some examples of the literary activities connected to the Birgittines during this period will be considered, partly by examining a set of personal letters from one of the protagonists. Parts of the first supplications for the canonization of Birgitta will be studied carefully and compared to other texts. Finally, we will discuss some other measures taken to enhance the work for the canonization. Vadstena after Saint Birgitta’s Death: Strengthening the Finances Birgitta Birgersdotter died in Rome in 1373, and it was not long before the efforts for her canonization began.6 The Memorial Book of Vadstena (Diarium Vadstenense)7 tells us that Birgitta’s daughter, Katarina Ulfsdotter (d. 1381), and others brought Birgitta’s bones to their first resting place at Vadstena, where they were installed for the first time in July 1374.8 There is also information about a new Italian journey, undertaken by Katarina already in 1375, when she needed to be close to the papal court in order to oversee various preparations for her mother’s case and make valuable contacts in the circles around the papal curia.9 Meanwhile in Sweden, construction work had progressed at Vadstena.10 Katarina was the unofficial leader of the young monastery, 11 but during her absence the activities were directed by the confessor general, Peter Olofsson, perhaps more known as the father confessor of Birgitta herself, 12 and by pp. 78–101, and Fritz, 600 år i Vadstena, ed. by Söderström, pp. 70–85 (with further references). 6 The early preparations for the canonization have been discussed in Nyberg, ‘The Canonization Process of St Birgitta of Sweden’; see also Fröjmark, Mirakler och helgonkult, pp. 31–41; and Nyberg, Birgittinsk festgåva, pp. 401–14. It can be remarked here that the texts of the supplications, which we shall examine later, have been subject to little research. 7 Diarium Vadstenense, ed. by Gejrot, also with commentary and Swedish translation in Vadstenadiariet, ed. by Gejrot. 8 Diarium Vadstenense, ed. by Gejrot, no. 31; Jönsson, ‘Den heliga Birgittas skrinläggning’, deals with the problematic questions surrounding the dating of Birgitta’s translation feast(s). Besides the solemn translation of June 1393 (see Diarium Vadstenense, ed. by Gejrot, no. 77), Jönsson discusses an earlier translation (28 May 1381) not mentioned in Diarium Vadstenense. 9 Diarium Vadstenense, ed. by Gejrot, no. 32. Another important matter for Katarina was to obtain papal confirmation of Birgitta’s rule (Regula Salvatoris). 10 Fritz, 600 år i Vadstena, ed. by Söderström, pp. 72–76 with further references. 11 On Katarina’s leadership, see Höjer, Studier i Vadstena klosters och birgittinordens histo­ ria, pp. 85–87. 12 On magister Peter Olofsson (Petrus Olavi) of Skänninge (d. 1378; not to be confused with his namesake, the prior of Alvastra monastery) see Aili, ‘Petrus Olavi’. 158 Claes Gejrot Katarina’s brother, Birger Ulfsson.13 Few documents survive to reveal the practicalities and realities of the period in which when the building project existed side by side with the original monastic congregation trying to lead a spiritual life. But there is at least one source that can give us useful glimpses. In a private letter, undated but most probably from the second half of 1375, Peter Olofsson writes to Katarina, quite naturally in Swedish, about some urgent matters at home.14 The original of Peter’s letter has disappeared, but a fifteenth-century transcription is found in the wide-ranging letter-book of Vadstena Abbey, a manuscript today preserved at the National Archives in Stockholm.15 The letter starts with Peter trying to encourage Katarina in her difficult undertakings, as he reminds her of a promise made by God to her mother, who was told that her daughter was to be endowed with good senses: ‘Your daughter Katarina needs wisdom, and this I will give her’ (Katerina thin dottir hon thorff snille uidhir och hona scal iach hænne giffua). After giving some fatherly advice to Katarina and extolling the strong efforts made for Vadstena by the recently appointed bishop of Linköping, Nils Hermansson,16 the confessor general then moves on to describe the serious problems affecting the monastery. The fact is that the construction work has consumed almost all the financial resources, and Peter fears that there will be no money for food. With drastic clarity, he declares that if all the funds — ‘more than 200 marks’ — allocated in the budget for the building are used, this might result in a situation with convent members wandering around like beggars. Peter now asks Katarina to write directly to the men responsible for the building activities and forbid them from using all the available funds. We cannot determine exactly who these men were; it is perhaps unlikely that Katarina’s brother Birger should be the target.17 ‘I cannot answer 13 Birger Ulfsson (Ulvåsaätten) was actually appointed by King Albrekt as a deputy for his sister (Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, x. 3 (2002), no. 8780, issued 18 May 1375). We cannot say if this appointment had any actual effect. 14 Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, x. 3 (2002), no. 8698. 15 Stockholm, Riksarkivet, MS A 20. See the thorough description in Ståhl, ‘Vadstena klosters stora kopiebok’. 16 On Nils Hermansson, who before his episcopate (from 1375) had served as the archdeacon of Linköping, see Schück, ‘Nicolaus Hermanni’. 17 In 1371, there is a preserved document (Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, x. 1 (1970), no. 42), naming Johan Petersson and Bishop Thomas of Växjö (see further below) as ‘supervisors’ of the construction work. Johan Petersson’s work as a builder is also attested by the memorial book (Diarium Vadstenense, ed. by Gejrot, no. 132). In this Diarium Vadstenense entry, the narrating brother reports how Birgitta herself commissioned Johan as the builder, and how he was assisted in his work by the bishop of Växjö. The Birgittine Movement & the Canonization of St Birgitta of Sweden 159 before God or his Mother, nor before the relatives of the sisters, if the food is taken from their mouths’, writes the confessor general. He suggests that a better solution would be to ‘let the builders pause and have the singing stop for a while’ (Wi thorom oc ey swara for Gudhi oc hans modhor oc for systranna ærlico frændom at wig matin takom fran thera munnom oc bætra ær at bygningin star i stadh nakra stund æntidheh oc sangir aflæggias). As a final emphatic wish, he tells Katarina that all ‘this would be easier to take if only you were at home’ (ware thu siælff hemma tha sculde mædh Gudz hielp thy bætir lidha)! These explicit worries about funding and conditions at Vadstena may perhaps be mirrored in a brief message in Latin that has survived from 1376. It emanates from one of the most important contemporary Swedish men, the wealthy landowner and ‘official’ of the Swedish king, Bo Jonsson, who wishes to know whether the monastery would like to have provisions for Lent, such as dried salmon:18 Votiua et sincera in omnium Saluatore salutacione premissa. Reuerende pater et domine magister! Noueritis, quod ego cum consorte et filiabus meis ceterisque, qui mecum sunt, diuina nobis cooperante clemencia optata gaudemus corporis sanitate. Hoc idem de uobis et suis seruitoribus, qui vobiscum sunt, faciat nos frequenter et diu percipere, qui in se confidentes continua prosperitate sicut pius pater misericorditer dirigit et conseruat. Amice dilecte! Si placuerit vobis aliquid habere de expensis quadragesimalibus, videlicet de siccis salmonibus et aliis, que mecum fuerint, hec libenter scirem tempestiue, antequam distribucio fieret in communj. Placeat igitur dileccionj vestre michi super hoc vestram rescribere voluntatem, quia usque ad Epyphanyam Dominj dante Domino continuam moram facio circa castrum. Jn Dei filio feliciter valeatis precipientes michi tamquam deuoto filio vestro fiducialiter in singulis, que volueritis me facturum. Scriptum Nycopie in profesto beati Nicholai episcopi, sub sigillo meo. Hec vester specialis Bo Jonsson. (My heartfelt wishes and greeting in the Saviour of us all! Reverend father and lord, Master. I want you to know that I, my wife, my daughters and the rest of the people with me are all — thanks to divine mercy — enjoying good bodily health. May He, who as a good father governs and protects with unbroken success those who believe in Him, make us perceive the same thing about you and His servants staying with you, and this often and for a long time! Dear friend, If you want to have provisions 18 Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, xi. 1 (2006), no. 9374 (5 December 1376). The translations in this essay are by the author. This text too is preserved in the Vadstena copy book. — The texts of the Diplomatarium in this essay are quoted with preserved orthography but sometimes with normalized punctuation. — On Bo Jonsson (Grip), see Engström, Bo Jonsson I. Till 1375, and Engström, ‘Bo Jonsson’. 160 Claes Gejrot for Lent, namely dried salmon and other things that I keep here, I would like to know this early, before the distribution to the people takes place. I would be grateful if you, my esteemed friend, could write back to me and tell me what you wish in this matter, since I now — God willing — intend to stay without interruption at my castle until the Epiphany of the Lord. Live well in God’s Son and give me, as your devoted son, your decision about every single thing you want me to do! Written at Nyköping, the day before St Nicholas’s feast, with my seal attached. This letter was written by your special friend Bo Jonsson.) Let us look for a moment at the text of this private letter, which reports several interesting details. The addressee is not explicitly named, but the words used (‘reuerende pater et domine magister’) make it clear that we are dealing again with Confessor General Peter Olofsson. Nor is there any direct mention of Vadstena, but the brothers and sisters are referred to as God’s servants staying with Peter (‘suis seruitoribus, qui vobiscum sunt’). For our purpose here, it is sufficient to see that the letter unmistakably shows Bo Jonsson assisting the monastery and the Birgittines. Indeed, he calls himself ‘vester specialis’19 (your special friend), and it may be added that the Diarium, announcing Bo’s death and burial right in the centre of the church, describes the benefactor with the words: ‘he loved this place dearly, as is shown by his repeated gifts’ (qui multum dilexit locum istum in donis suis continuis).20 The letter demonstrates clearly the support given by one of the most prominent men of the time, but, as we shall see, a number of close, or more distant, relatives of Birgitta were also to play essential parts during these years. After a while, the financial situation of the abbey improved, while various incomes continued to flow in, eventually making Vadstena one of the richest institutions of late medieval Sweden. 21 During 1375 alone we find no fewer than twenty-three donation documents with Vadstena as the beneficiary. 19 The word specialis is carefully chosen and clearly indicates his status as a particularly generous secular benefactor to a monastery. We may compare with the note on the notorious bailiff Jösse Eriksson (d. 1436) who after his dramatic death is remembered thus in the Diarium (Diarium Vadstenense, ed. by Gejrot, no. 465, 1436): ‘Ffuit enim specialis amicus monasterii et contulit magnum testamentum’ (he was a special friend of the monastery and gave [us] a large will). 20 Diarium Vadstenense, ed. by Gejrot, no. 43 (1386). 21 Birgitta’s plans which had been expressed in the rule (Cf. Birgitta of Sweden, Opera minora, ed. by Eklund, pp. 164–65) meant that the donations made by the relatives of the sisters on their introduction should be enough as a prebendary basis to supply for the needs of the monastery; cf. also Nyberg, Birgittinische Klostergründungen des Mittelalters, pp. 56–58. On the developing economic circumstances surrounding the Birgittine foundation, see Norborg, Storföretaget Vadstena kloster. The Birgittine Movement & the Canonization of St Birgitta of Sweden 161 Among these is the document displaying Katarina’s own contribution, and it shows that she must have managed to take care of this business and obtain her siblings’ consent before her journey to Rome, mentioned above. The charter, dated 25 March and explicitly written and issued in Vadstena Abbey, comprised a number of farms and lands in the province of Östergötland that were handed over to the young monastery.22 Katarina authorizes her brother to deal with the further legal complications on account of the monastery, which ought to have been in accordance with Birger’s responsibilities for the monastery during Katarina’s absence. The choice of persons requested to append their seals to the donation document clearly illustrates some of the active connections with high nobility that Katarina could count on for the benefit of the monastery. The important persons — knights and councillors — who witness the donation with their seals are in fact all members of her extended family: Til thessa witnis byrdh bedhis jak hedherlika ok wælborna riddara herra Karls Wlfson aff Toftom laghmanz ij Wplandum, herra Bændictz Philippussons ok mins kæra førnempda brodheris herra Birghers Wlfsons minnæ kæra fornempda syster frw Ceciliæ ok hedherliks manz Pætars Ribbings incighle medh mino eghno incighle fore thetta brewit.23 (As testimony of this, I ask that the seals of the honourable and noble knights Sir Karl Ulfsson of Tofta, the chief judge of Uppland, and Sir Bengt Filipsson, as well as that of my dear mentioned brother Birger Ulfsson, my dear mentioned sister Lady Cecilia and the honourable man Peter Ribbing be appended to this charter together with my own seal.) To sum up, these texts show the Vadstena economy as it grows stronger and exemplifies the early influence of a circle of leading secular men and women. Literary Efforts Vadstena required more than the establishment of new material conditions. An entirely new liturgy with especially composed texts and hymns had to be produced for the monastery, and indeed also for other ecclesiastical institutions 22 Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, x. 3 (2002), no. 8743 (25 March 1375; in Swedish). 23 Karl Ulfsson (Sparre av Tofta) was married to Katarina’s cousin Helena Israelsdotter (see Äldre svenska frälsesläkter, ed. by Wernstedt, i, 36–37 and 87–88) and Bengt Filipsson (Ulv) to Katarina’s sister Cecilia (see i, 302–03 and 93–94). Peter Ribbing was the son of Katarina’s elder sister Märta (see i, 93). Claes Gejrot 162 wishing to celebrate Birgitta. Bishop Nils Hermansson of Linköping wrote an office — a special liturgy — devoted to Birgitta, called Rosa rorans after the first words of the first antiphone; it was to be used in his own diocese. This is arguably the best-known and most popular work ever written for her cult.24 However, Bishop Nils was not alone. In Uppsala — and probably often in his summer residence of Biskops-Arnö — Archbishop Birger Gregersson seems to have been working intensively to finish his texts for the cult of the Swedish candidate for sainthood. At the centre of his attention, at least during parts of the first half of 1376, was another office for Birgitta, called Birgitte matris inclite.25 This liturgy would soon be in use in most of the dioceses in the Uppsala church province, except that of Linköping — which included Vadstena — where Nils Hermansson’s composition was instead chosen. What do we know about the writing process of these Birgittine offices? As to the circumstances of the composition of Nils Hermansson’s work, our knowledge is sparse. In fact, we do not even know when the Rosa rorans office was composed. (This question, however, will be further discussed below.) In the case of Birger Gregersson, we are more fortunate. Four of his private letters from 1376 have been preserved in transcription, providing us with the opportunity to see him at work.26 They are all messages directed to Confessor General Peter Olofsson and the Vadstena brethren. As expected between men of the church, the language employed is Latin. On several occasions the archbishop mentions the Birgitta office (historia (or hystoria, as here) is the Latin 24 On the Rosa rorans see Lundén, Nikolaus Hermansson biskop av Linköping, pp. 27–29. Birger Gregersson (Malstaätten), was archbishop of Uppsala from 1366 until his death in 1383. For biographical details see Engström,‘Birger Gregersson’, and Äldre svenska frälsesläkter, ed. by Wernstedt, i, 177; On the Birgitte matris inclite, see Birger Gregerssons Birgitta-officium, ed. by Undhagen, for the origins of the office, see esp. pp. 19–31. Also this office is named after the first verse of the first antiphone; for a comparative study of the two texts, see Borgehammar, ‘Birgittabilden i liturgin’; On Birger Gregersson as a Latin writer, see Birger Gregerssons Birgittaofficium, ed. by Undhagen, pp. 10–18 and 81–117; Önnerfors, ‘Zur Offiziendichtung im schwedischen Mittelalter’, and Liedgren, ‘Ärkebiskop Birger som latinsk prosastilist’; on Nils Hermansson, see Lundén, Nikolaus Hermansson biskop av Linköping. The two bishops probably knew each other well. They were about the same age and shared an academic background. Both men had studied in France, starting with artes at the University of Paris and after that turning to canon and civil law at Orléans. 26 Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, xi. 1 (2006), nos 9224 (13 March), 9229 (27 March), 9240 (21 April), 9246 (6 May). The letters are all copied in Stockholm, Riksarkivet, MS A 20, and also printed in Birger Gregerssons Birgitta-officium, ed. by Undhagen, pp. 23–26. 25 The Birgittine Movement & the Canonization of St Birgitta of Sweden 163 term used by the archbishop himself ) which appears to be on his writing desk at that very moment. Let us look at one of these letters. Affectuosa et votiua in Domino salutacione premissa. Noueritis, amici dilecti, quod mittimus vobis cum exhibitorepresencium Conrado hystoriam domine Birgitte ex Dei gracia ad sui et beate Virginis gloriam et honorem ac veneracionem ipsius domine Birgitte completam vsque ad officium misse, quod iam diu fecissemus, si non fuissemus tam cotidianis et tediosis hospitalitatibus et aliis diuersis negociis impediti. Destinabimus tamen vobis infra festum pasche vel circa huiusmodi officium Domino concedente rogantes sumopere eandem hystoriam per prudencias tamen vestras cum diligenti studio prius examinatam et accepta copia ab illa, vlterius sub sigillis vestris domino nostro Wexionensi, in casu quo ad monasterium vestrum in hoc jeiunio non peruenerit, destinari. Ceterum mittimus vobis quoddam brachium argenteum ex voto propter dolorem, quem in brachio nostro dextro habuimus, factum ad honorem Dei et laudem ante reliquias domine Birgitte, cuius interuenientibus meritis sanitatem recepimus, appendendum. Et rogamus, vt verbis exhibitorispresencium fidem adhibeatis creditiuam in Domino perpetuo valituri. Scriptum apud Arnø in crastino beati Gregorii pape, nostro sub secreto. Nos Birgerus prouidencia diuina archiepiscopus Vpsalensis.27 (My heartfelt wishes and sincere greeting in the Lord! I wish you to know, my dear friends, that I send to you with my letter carrier, Konrad, the historia of Lady Birgitta, which is now finished until the office of Mass through God’s grace and for His and the holy Virgin’s glory and honour and for the cult of Lady Birgitta herself. I would have finished the text long ago, if I had not been thwarted by daily, tiring visitors and other business. However, during Easter or thereabouts — with God’s help — I will send you this office. And I ask you to use your good knowledge and examine the historia very thoroughly before copying the text and finally sending it to our bishop of Växjö, if he himself does not come to your monastery in Lent. Furthermore, I dispatch to you an arm of silver that was fashioned to the honour and praise of God because of the promise I made on account of the pain in my right arm. This silver arm is to be placed in front of the relics of Lady Birgitta, since it was through her intercession and merits that my health was restored. And, asking you to trust the words of the letter carrier, I wish you to live well forever in the Lord. Written at (Biskops-) Arnö, the day before the feast of the holy Pope Gregory, with my seal attached. I, Birger, by divine providence Archbishop of Uppsala’.) The image transferred to us is that of an author experiencing recognizable and timeless hardships. Birger Gregersson was a man in his fifties who had held the office of archbishop for about ten years. It seems clear that he now, in 1376, 27 Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, xi. 1 (2006), no. 9224. Claes Gejrot 164 despite all his other work, was near the completion of the Birgitta office. As the letter above shows, the work is running behind schedule. We do not know exactly when he began writing on the office, but the wording of the letter iam diu (long ago) indicates that he had worked for some time. It seems likely that he began directly after Birgitta’s death. The Archbishop then proceeds to promise the Vadstena brothers that they will receive the whole text by Easter time. It is interesting to note that Birger Gregersson asks the Birgittines at Vadstena to look through the text. We may certainly assume that the Archbishop particularly wanted to hear the opinion of the confessor general himself, Peter Olofsson, a man with long experience in compositions of text as well as music. Among other things he was the author and composer of the liturgy — including several hymns — of the Birgittine sisters, the Cantus sororum.28 According to the quoted letter, as soon as the brothers had procured a transcription of the Archbishop’s text, the finished text was to be sent to Bishop Thomas of Växjö or handed over to him if he visited the monastery. He was also Birger Gregersson’s paternal uncle and something of a mentor. 29 In another private letter from 1376, the Archbishop himself describes the Växjö prelate as his ‘teacher and master who will be able to correct all that needs to be corrected’.30 Notwithstanding his good intentions as to the conclusion of the project, some textual problems still hindered the author. As the same letter shows, the Archbishop had to give the brethren detailed information on some additions and instruct them how to correct errors he had revealed himself. Apart from the textual work with the office, some practical matters are mentioned in these letters. Among other things, Birger Gregersson wants Vadstena’s assistance in sending fifty florins to help Katarina in her efforts in Rome.31 And, as the letter above shows, the Archbishop had earlier ordered the production of a votive artefact which is now sent to the monastery with the explicit instruction that it be placed near Birgitta’s bones. According to the letter, this arm 28 Peter Olofsson’s hymns are printed in Analecta hymnica medii aevi, ed. by Blume and Dreves, nos 362–88. On Cantus sororum see Servatius, Cantus sororum. 29 On Bishop Thomas Johansson (Malstaätten) see Äldre svenska frälsesläkter, ed. by Wernstedt, i, 176. He died not long after these events, probably later in 1376, after having served as bishop of Växjö for more then thirty years. As one of the supervisors of the monastic building site (see above, n. 17), Bishop Thomas would perhaps have visited often. 30 Ut ipse, qui noster magister est et dominus, corrigere valeat corrigenda: Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, xi. 1 (2006), no. 9240. 31 Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, xi. 1 (2006), no. 9246. The Birgittine Movement & the Canonization of St Birgitta of Sweden 165 made of silver was meant to commemorate the fact that Birger Gregersson had been cured from the soreness of his right arm, thanks to Birgitta. It is perhaps not too far-fetched a guess that the arm pains suffered may have had something to do with all his writing? The First Supplications for Canonization Thus, it is obvious that Birger Gregersson was deeply involved in the ecclesiastical and cultural heritage of Birgitta and the promotion of the Birgittine order. It is only natural to identify him as one of the men behind the solemn and official supplication for canonization that was submitted ‘to the pope and the College of cardinals in 1376’.32 Besides the Archbishop, the issuers of the letter are two of his suffragans, Bishop Mattias Larsson of Västerås and Bishop Nils Hermansson of Linköping.33 We may safely assume that the two authors of the liturgical offices in Birgitta’s honour, Birger Gregersson and Nils Hermansson, were the most influential of the issuers as to the definitive design and wording of the document. We will soon return to the question of which of the two may have been the principal originator. The Latin text formulated in this supplication (with the incipit Immensa Christi bonitas) seems to have become something of a model for future supplications.34 It reveals the involvement of an accomplished Latinist. The language is wholly adapted to the demands of the situation and to the expectations of the learned readers. References to church authorities and Christian writers are abundant. An analysis of a central excerpt of the text may be illustrative: 32 Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, xi. 1 (2006), no. 9340 (9 October 1376). This supplication and several others have been preserved through copies in Stockholm, Riksarkivet, MS A 14. For quotations and references, see Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others. 33 On Mattias Larsson, see Ekström, Västerås stifts herdaminne, i. 1, 88–95. A Swedish translation of the first supplication is printed on pp. 93–94. 34 It is used in the supplication issued by the Swedish king on the same day (Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, xi. 1 (2006), no. 9339, see below). Furthermore, it is seen in the document issued by a group of leading Swedes on 8 February 1377, in the supplication from the bishops and cathedral chapters on 27 May 1377 (directed to Pope Gregory XI), and also in that sent to Urban VI, the new pope, by the bishops and certain abbots on 18 January 1379 (Svenskt Diplomatariums Huvudkartotek, nos 40534, 11029, and 11413). 166 Claes Gejrot Ipse conditor lucis eterne humi(l)lima dispensacione thalamum vteri virginalis elegit, Ipse virginibus ad integritatis amorem viduisque ad continencie decorem illuxit, Ipse hijs vltimis mundi temporibus velud nardum odoriferam oliuamque speciosam, gloriosam scilicet sancte memorie Brigidam ex nobiliori gentis Gottorum prosapia oriundam, in mundum jnuexit, veritatis filiam, bonitatis alumpnam conuersacione conspicuam, fama spectabilem, opinione preclaram, humilitatis et paciencie omniumque virtutum tanta maturitate compositam, vt plurimos ad diuini cultus gloriam ab eorum erroribus et vicijs suarum diffusis virtutum aromatibus incitaret. (He, the creator of the eternal light, chose humbly to be born by a virgin, He shone for virgins to make them love chastity and for widows to make them honour moderation, He, in these last days of the world, brought the honourable Birgitta, of holy memory, into this world from a noble family among the people called ‘Götar’. She was like the sweet-smelling nard and the beautiful olive branch, a daughter of truth, a pupil of goodness, prominent in her way of life, admirable and eminent as to her fame and reputation. She possessed such a mature supply of humility, patience and other virtues that she led many people from their faults and sins to the honourable divine worship through the fragrant diffusion of her virtues.) The English translation is by necessity very free. An exact translation from the carefully composed, rhythmical Latin is impossible to make. We note here at once the marked and anaphoric use of the subject, the pronoun Ipse (‘He’) referring to God/Christ, in a tricolon with its climax placed on Birgitta’s birth. Birgitta — Brigidam — in this way becomes the central object surrounded by a varied set of positive words (‘velud nardum odoriferam oliuamque speciosam […] veritatis filiam, bonitatis alumpnam conuersacione conspicuam, fama spectabilem, opinione preclaram’). In a subsequent passage, Birgitta is portrayed as shining star and a remarkable light: que tamquam sydus omnium virtutum ornamento, dum viueret, radiabat in terris, iam de mundo translata quasi luminare conspicuum et splendore glorie et multorum coruscacione signorum effulget. Propter quod ad monasterium in Wastenum diocesis Lincopensis, vbi gloriosum eius corpus repositum est, de diuersis regnis, nacionibus et linguis magna gencium multitudo concurrit laudantes et glorificantes Deum in miraculis et prodigijs, que per eam operari cotidie dignatur. (While she lived, she shone in the world like a star, adorned by all virtues. Now, taken away from this world, she glows like a remarkable light by the brightness of her honour and the sparkling of many signs. For this reason, people are gathering in crowds at the monastery at Vadstena in the diocese of Linköping, where her glorious body rests. Coming from various countries and nations, speaking different languages, they praise and glorify God for the miracles and portents that he daily deigns to put in motion through her.) The Birgittine Movement & the Canonization of St Birgitta of Sweden 167 Nils Hermansson’s Influence Nils Hermansson may have been the originator of the text, at least in part. This would be indicated by the fact that the final lection in the Rosa rorans clearly parallels the passage quoted above from the 1376 supplication. The relevant text of this lection follows: Et quia tamquam sydus ex(c)ellens omnium uirtutum ornamento, dum uiueret, radiabat in terris, iam de mundo translatam non solum in monasterio predicto Watzstenum, ubi corpus eius quiescit, set eciam in Roma et aliis mundi partibus diversis miraculorum prodigiis et signis ipsam […] mirificat […] dominus noster Iesus Christus.35 (And because, while she lived, she shone in the world like a star, prominent with the adornment of all virtues, our Lord Jesus Christ now — when she has been taken away from the world — makes her famous, not only in Vadstena monastery, where her body rests, but also in Rome and in other parts of the world with various miraculous portents and signs.) The two passages indeed bear many similarities, and this fact seems not to have been observed in earlier scholarly discussions. There is a further detail that might point towards Nils Hermansson’s active participation in formulating the supplication text, namely the wording ab ordinario loci, scilicet me epis­ copo Lincopensi (‘by the ordinary of the diocese, that is by me, the bishop of Linköping’). However, this cannot be taken as a strong indication: Since Nils was one of the issuers, anyone could have formulated the words for him.36 We will come back to this passage below. Returning to the corresponding passages in Nils Hermansson’s office and the supplication we cannot say with certainty which text influenced the other. The formulation of the supplication may actually have come first: as already mentioned, we have no positive dating as to the writing time of the Rosa rorans. An interesting additional piece of information is provided by the 1893 editor of the office, Henrik Schück. He says, in a brief note, that the relevant passage in the lection may have been added after the canonization.37 35 Nils Hermansson, Rosa rorans, ed. by Schück, p. 51 (reprinted in Lundén, Nikolaus Hermansson biskop av Linköping, p. 106). 36 As Nils Hermansson was the ordinarius of the diocese involved it could be reasonably argued that his name ought to be in the supplication (even if he did not formulate the text). 37 Nils Hermansson, Rosa rorans, ed. by Schück, p. 51 n. 2 (which is misprinted as n. 3). Schück gives no reason for his assumption. Claes Gejrot 168 Figure 8. The seal of the Bishop of Linköping, Nils Hermansson. Attached to SDHK no. 13567 (orig. on parchment, 29 August 1389, Riksarkivet, Stockholm). Photo: Kurt Eriksson. It is also necessary to look at another, much older source that is probably behind the expressions formulated here. The death of the church father St Jerome is described in the following way in a text widely read and used throughout the Middle Ages: anima /Hieronymi/ […] tanquam sidus omnibus virtutibus radians carnis resoluta coeno coelorum regna adiit gloriosa. In quibus jam certe tanquam luminare conspicuum renitet et splendore beatitudinis et multorum coruscatione prodigiorum.38 ( Jerome’s soul came to the glorious kingdom of heaven like a star, shining with every virtue, cleansed from the filth of the flesh. There, without any doubt, he now shines like a remarkable light, both through the brightness of his holiness and through the glittering of many portents.) This excerpt about Jerome has apparently been considered suitable to be used as a source and inspiration for the vocabulary and phrasing of a description of Birgitta’s holiness. In my opinion, the most probable explanation for the similarities in the texts concerning Birgitta is that Nils Hermansson, when taking part in the composition of the important supplication, reused a couple of 38 Eusebius Cremonensis, De morte Hieronymi, chap. 52 (col. 275). The Birgittine Movement & the Canonization of St Birgitta of Sweden 169 phrases he had employed in his office. It seems natural to presume that Nils started writing the Rosa rorans texts quite soon after Birgitta’s death. International Efforts The image of Birgitta as a glowing light recurs in other supplications issued the same year. From her court in Castellamare di Stabia, Queen Giovanna of Naples gave her support for the canonization.39 Her supplication was issued six days before that of the three Swedish bishops, and the strategy seems to have been to leave it to the Neapolitan royal supplication to open the first doors.40 Queen Giovanna now formally requests the pope to write Birgitta’s name in the book of saints, since she was ‘a decorative model for all women who refrained from secular happiness and wealth so as to be able to dedicate her soul to Christ’. The Neapolitan ruler continues her supplication by depicting Birgitta as a candle that burns brightly for all mankind: velut ardentem lampadem tantis circumcinctam fulgoribus super candelabrum collocarj, vt luceat omnibus et sub eius luminis claritate eam venerando exemplariter gradiantur. (like a burning candle [she shall] be placed on the candlestick surrounded by such a number of lights that she will shine for all men, so they will be able to lead exemplary lives by worshipping her in the brightness of her glow.) Here, the reader may at once detect a clear Biblical reference — Matthew 5. 15: ‘Neque accendunt lucernam et ponunt eam sub modio sed super candelabrum ut luceat omnibus qui in domo sunt effort’ (Neither do men light a candle and put it under a bushel, but upon a candlestick, that it may shine to all that are in the house).41 Of course, the stylistic demands of the genre — formal texts about 39 Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, xi. 1 (2006), no. 9333 (3 October 1376). On Queen Giovanna I (of the Anjou family, from 1343 queen of Naples, titular queen of Jerusalem and countess of Provence, murdered 1382), see above all the extensive biography (in three volumes) by Léonard, Histoire de Jeanne Ire; for a brief overview of more recent information see Dictionnaire de biographie française, ed. by Balteau, Prévost, and d’Amat, xviii (1994), p. 614 and Lancaster, In the Shadow of Vesuvius, pp. 67–69. 40 The supplication sent in by the Swedish king was issued on the same day as the bishops’ document (see further below). 41 The importance of the words from Matthew can be further supported. In an article on the required proofs of sanctity in the canonization process, Gábor Klaniczay comments on the standards set up by Pope Gregory IX (in 1228, for the process of St Francis): ‘[T]he bull of the 170 Claes Gejrot candidates for sainthood — were such that one must expect this kind of prose. But, all the same, the phrases chosen resemble the Swedish texts quoted above. Queen Giovanna had received Birgitta at her court and belonged to the highest social stratum of contacts employed by the emerging Birgittine movement. It is very likely that the direct cause of the queen’s endeavours for the canonization is to be sought in what was said and done during Katarina’s visit to Naples and the royal court in that year (1376).42 In the same document, the queen takes the opportunity to recommend Birgitta’s daughter to Pope Gregory XI (r. 1370–78). We should not rule out the possibility that Katarina brought with her to Naples a draft, or perhaps an already finished but not sealed, document that had been composed by one of the literary, efficient, and dedicated bishops in Sweden who would now be even further involved in the process, this time by securing foreign powerful assistance. It would indeed be natural to see the archbishop, the ecclesiastical leader in Sweden, as the figure most suitable to approach Queen Giovanna, most probably together with the king of Sweden. But we have no letters or other documents proving this. However, we demonstrated above how the archbishop in one of his letters to Vadstena mentioned his sending money to Katarina in Italy. This proves, at least, that there was a direct connection between the two at the time, perhaps also before her meeting with the Neapolitan Queen. As expected, the Swedish promoters of the canonization process were interested in further international support, if only to spread the saintly rumours. From the following year, 1377, we find yet another supplication from the highest ranks of European secular authority. Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1355–78), sent in his request to Pope Gregory XI using phrases comparable with the earlier documents we have seen (‘splendor lucis eterne […] illustrando beate memorie Brigidam ex nobiliore gentis Gottorum prosapia oriundam’).43 Just as with Queen Giovanna, we do not know the details of the process leadpope also indicated that miracles, as divine signs, would help to ensure that the light (lucerna) of his sanctity would not be obscured but rather be set in a fine candelabrum’. Klaniczay, ‘Proving Sanctity in the Canonization Process’, p. 119. 42 Höjer, Studier i Vadstena klosters och birgittinordens historia, pp. 106–07; Morris, St Birgitta of Sweden, pp. 145–46. 43 Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, xi. 2 (2009), no. 9586 (9 September 1377), also in Acta et processus canonizacionis beate Birgitte, ed. by Collijn, pp. 53–54. As to the quotation ‘the brightness of eternal light […] shining on Birgitta, in holy memory, born in a noble family in the people called Götar’, cf. the bishops’ supplication above. On Charles IV, see Seibt, Karl IV: Ein Kaiser in Europa. The Birgittine Movement & the Canonization of St Birgitta of Sweden 171 ing to the Emperor’s actions. In the following year, the election of the new pope, Urban VI (r. 1378–89), seems to have prompted new supplications, and interesting documentation from this year reveals some background to Charles’s petition. In an undated document, which must have been issued in the winter of 1378–79, the imperial court is approached by five prominent Swedish men. Here we find some of the leading secular profiles with an interest in the Birgittine cause: the ‘special friend’ of Vadstena mentioned above, Bo Jonsson, is one of the issuers, but also Karl Ulfsson (Sparre av Tofta) and Birgitta’s son Birger.44 These men were now joined by the two councillors Erengisle Sunesson and Sten Bengtsson45 in their joint request to the Emperor to direct a supplication for Birgitta’s cause to Urban VI.46 We have no such document from the Emperor to Urban, and it is likely that it never was issued. Moreover, we have every reason to suspect that the same, or a similar, group of secular promoters had acted in the same way the previous year, in order to secure the imperial supplication to Gregory XI. In fact, the narratio of the emperor’s 1377 supplication begins by referring to what he has been told through the trustworthy reports of many people (‘fidedigna relacione multorum’). Such a general, standard remark is of course no proof of influence from a certain direction, but, all the same, it may refer to a written request from Sweden. Another interesting detail in Charles IV’s text is found right at the end and shows the Emperor regarding himself as the spokesman of other rulers as well.47 Twenty days after this supplication, Charles IV issues yet another document with similar content and phrases, directed this time, however, not to the pope but probably to a cardinal.48 44 Äldre svenska frälsesläkter, ed. by Wernstedt, i, 93. On Erengisle Sunesson (båt), married to Birgitta Birgersdotter’s niece, and Sten Bengtsson (Bielke), his stepson, see Svenskt biografiskt lexikon, ed. by Nilzén and others, vii: Bülow– Cedergren (1927), pp. 49–50; Äldre svenska frälsesläkter, ed. by Wernstedt, i, 92. 46 Svenskt Diplomatariums Huvudkartotek, no. 11414; Acta et processus canonizacionis beate Birgitte, ed. by Collijn, pp. 52–53 (as an addition in the footnotes). The letter from the Swedish group of Birgittine lobbyists is likely to have reached its addressee too late. After Charles IV’s death on 29 November 1378, Wenzel of Luxemburg became the new emperor. 47 ‘Jn eo, pater beatissime, nedum nobis sed et multis alijs principibus catholicis facietis clemencie graciam specialem’ (By this, most blessed father, you will give your special grace of mercy not only to us, but to many other Catholic princes). 48 The preserved transcription does not reveal the address, but the formulae used (which are not suitable for the pope) point to a high ecclesiastical dignitary. Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, xi. 2 (2009), no. 9596 (29 September 1377). 45 Claes Gejrot 172 The Swedish King Let us now again look at the situation in Sweden and make some observations as to the actions of King Albrekt of Mecklenburg, who had ruled Sweden for a decade. The source material at hand indicates that he did not embrace the monastic establishment at Vadstena with great enthusiasm. He had issued some routine renewals of earlier royal decrees concerning a special taxation for the construction work and a couple of letters of protection, but apart from that there is nothing to report.49 Unsurprisingly, however, he must have been interested in promoting the canonization. The king had serious financial problems and must have seen an opportunity to gain from all the attention that Birgitta’s elevation to sainthood would bring.50 The supplication issued by King Albrekt together with his councillors and other leading men is — mutatis mutandis — almost the same as the one sent in by the archbishop and two of his suffragans, as discussed above.51 Thus, King Albrekt had only to turn to his archbishop in order to find a competent Latinist for the phrasing of the document. As a matter of fact, the relationship between the king and Birger Gregersson is intricate and complex. During his time as cathedral dean in Uppsala, Birger had been the king’s chancellor, right at the start of his regime. Naturally, he had then often been in Albrekt’s presence. But later, especially during his last years as archbishop, Birger’s opposition to the king grew.52 All in all, the preserved material does not give the picture of a king wholly devoted to the Birgittine cause. We must at this point keep in mind that the first large donations to Vadstena came from King Albrekt’s old enemy, the dethroned king, Magnus Eriksson (who had died in Norwegian exile in 1374), and his queen.53 49 On this taxation, the so called ‘vårfrupenning’ (Our Lady’s Tax), see e.g. Höjer, Studier i Vadstena klosters och birgittinordens historia, pp. 56–57, and Cf. Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, viii (1953–76), no. 7046 (22 August 1364). In one of the letters of protection (Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, x. 3 (2002), no. 8780, 18 May 1375) Birger Ulfsson is appointed temporary leader of the work at Vadstena, as has been mentioned above. 50 King Albrekt was under serious political pressure too; for a brief survey of the political situation in the mid-1370s see Nyberg, ‘The Canonization Process of St Birgitta of Sweden’. 51 Incipit: Immensa Christi bonitas. The royal supplication is edited as Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, xi. 1 (2006), no. 9339 (9 October 1376). In the king’s new supplication of 18 January 1379 (Svenskt Diplomatariums Huvudkartotek, no. 11412) another formulary is utilized. 52 53 Engström,‘Birger Gregersson’, p. 426. Cf. n. 4 above. It may be added that King Albrekt and his German supporters are The Birgittine Movement & the Canonization of St Birgitta of Sweden 173 Vitae and Miracles The supplications we have seen were, quite naturally, very important. The international undertakings for the canonization and the requests from important Swedish figures all brought substantial momentum to the future negotiations, and were necessary for the process in the curia to begin.54 But these measures were not enough, and further actions and preparations were essential. Apart from new missions to Rome,55 narrations of Birgitta’s life — vitae — as well as collections of miracles were commissioned. Such detailed texts, witnessed and sealed, were required for successful results in Rome.56 A whole series of documents compiling the miraculous events due to Birgitta’s intervention have been preserved. In the three bishops’ supplication, quoted above, there is an additional piece of information on this point. A book of miracles was to be dispatched to the pope: Quorum [sc. miraculorum] aliqua in libello quodam conscripta per deputatos ab ordinario loci, scilicet me episcopo Lincopensi, sanctitati vestre dirigimus.57 (We are sending to Your Holiness some of these miracles that have been written down in a book by men chosen by the ordinary of the diocese, that is, by me, the Bishop of Linköping.) adversely depicted as aves rapaces (birds of prey) in Vadstena’s memorial book (Diarium Vadstenense, ed. by Gejrot, no. 22). 54 Supplications continued to arrive at the curia in the following years; the last documents before the canonization that we know of were issued by Queen Margareta, the bishops, and some secular leaders on 30 October 1389 (Svenskt Diplomatariums Huvudkartotek, nos 13608 and 13609) and by Vadstena Abbey about a year later (no. 13774). 55 For instance by several Vadstena brothers (Höjer, Studier i Vadstena klosters och bir­ gittinordens historia, pp. 111–12; cf. e.g. Svenskt Diplomatariums Huvudkartotek, no. 12059, Diarium Vadstenense, ed. by Gejrot, no. 50. 7). 56 Birger Gregersson is the author of a prose life of Birgitta (in Gregersson, Legenda Sancte Birgitte, ed. by Collijn). Better known is the life written by Birgitta’s confessors, the two men both named Peter Olofsson (cf. n. 12 above; one (revised) version of their vita is published in Acta et processus canonizacionis beate Birgitte, ed. by Collijn, pp. 73–101; for an English account of the complicated textual history, see Birgitta of Sweden, Life and Selected Revelations, ed. by Harris, p. 216. A verse vita was produced by Magister Ragvald of Linköping (see Ragvald of Linköping, ‘Vita metrica beate Brigide’, ed. by Beji-Wahlstöm). On the collection of miracles see Fröjmark, Mirakler och helgonkult, pp. 31–43. For documentary material see e.g. Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, x. 3 (2002), nos 8772, 8870; xi. 1–2 (2006–09), nos 9305a, 9378, 9436, 9466, 9468, 9471, and 9587. 57 Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, xi. 1 (2006), no. 9340 (9 October 1376). Claes Gejrot 174 Figure 9. Saint Birgitta’s daughter Katarina writes from the papal summer residence in Anagni to the archbishop of Uppsala, Birger Gregersson. She describes the present situation (the summer of 1377) in her mother’s canonization process. DS no. 9568 (orig. on paper, 29 July 1377), Riksarkivet, Stockholm). Photo: Riksarkivet, Stockholm. Presumably, this book was brought to the curia by the same messenger who carried the supplication. An undated letter (which ought to have been written before September 1376) gives the names of the mentioned miracle annotators.58 The three men were all at the time priests in Vadstena, but Johan Präst, Gudmar Fredriksson, and Kettilmund were later to enter the monastery.59 In other countries parallel activities were arranged for the mustering of facts around these wondrous occurrences. In one preserved document, Archbishop Bernard of Naples orders one of his assistants to start the collection of miracles in the town of Naples.60 There is every reason to start this work, writes Bernard, and 58 Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, xi. 1 (2006), no. 9305a. Diarium Vadstenense, ed. by Gejrot, nos 41, 48, and 53. 60 Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, xi. 1 (2006), no. 9303 (25 August 1376). For biographic details on Archbishop Bernard (of Rhodes), d. 14 November 1377, who 59 The Birgittine Movement & the Canonization of St Birgitta of Sweden 175 not keep quiet about Birgitta’s saintly rumour. In an introductory part the image we have seen frequently used above, that of Birgitta as a light, is again present: Et cum in istis temporibus vltimis huius seculi mali Dominus nobis, licet indignis, contulerit lucernam et eam posuit super candelabrum videlicet beatam Brigidam de Swecia de gente regali exortam, quam illustrauit innocencia multis virtutibus et cui multa secreta reuelauit. Que viuens in ciuitate nostra Neapolitana nonnulla salubria consilia nobis et populo Neapolitano contulit et pro nobis Deum sepius interpellauit et ad eius preces nonnulla mala cessauerunt sed post eius mortem, sicut in vita, ad eius preces Dominus noster in nostra ciuitate multa miracula fecit, que non debent silencio tradi sed pocius ad laudem Dei diuulgari et publicari. (And in these last times of this evil world the Lord gave us a light, although we are unworthy, and placed it on a candlestick, namely the holy Birgitta from Sweden of royal descent, and he made her famous through her virtues and he disclosed many secrets to her. When she lived in our town Naples she gave much healthy advice to us and to the Neapolitan people, and she often spoke with God for our sake. Many evil things ended because of her prayers. And, because of her prayers, after her death just as in her life, our Lord performed many miracles in our town. These should not be passed over in silence, but rather be spread and made public as a way to praise God.) Further Development and Concluding Remarks Already in the summer of 1377 Katarina could inform the Swedish archbishop that her work had made some progress. She wrote from the papal summer residence in Anagni, and the news was good: the first propositio concerning her mother’s canonization had been introduced by Magister John of Spain before the pope and the collegium of cardinals earlier that year, on 29 May, in the church Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome.61 Furthermore, Katarina’s letter reports that a group of noblemen, Count Gomez, the count of Nola, and Latino Orsini, had given testimony of Birgitta’s life and miracles, and all this was received in the best way by the pope. She was now waiting for the second proposition to be brought forward in Anagni, and among her special friends she counts two cardinals, Guy de Malesset of Poitiers and Guillaume d’Aigrefeuille.62 had served in the papal administration in the time of Urban V, see Vones, Urban V, pp. 351–52. 61 Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, xi. 2 (2009), no. 9568. 62 On the letter see Höjer, Studier i Vadstena klosters och birgittinordens historia, pp. 107–08. John of Spain ( Johannes de Hispania) from Burgos, Cardinal Guy de Malesset of Claes Gejrot 176 This advancement of the canonization issue was of course welcome information to all those who had taken part in the efforts so far. The activities in 1377 reported by Katarina meant that the process was formally launched. New complications would appear; new popes were to be elected before Birgitta was officially recognized as a saint, in October 1391. A period of fourteen years was a comparatively short time for the completion of a canonization process,63 but during this period, almost all the main personalities we have discussed here passed away. The two writers of liturgical poetry, prose, and papal supplications, Arch­ bishop Birger Gregersson of Uppsala and Bishop Nils Hermansson of Linköping, had both ended their days. The latter died only a few months before the canonization. Birger Gregersson, who must be singled out as one of the most important operators of the time, died in Uppsala in 1383. Katarina Ulfsdotter, who had stayed with her mother in Rome since 1350 and led the monastic movement after Birgitta’s death, passed away in Vadstena in 1381; her brother Birger died in 1391. Peter Olofsson, the first confessor general in Vadstena, who had worked with liturgical and, as we have seen, also with more material matters, had died in Vadstena in 1378. The special benefactor of Vadstena, the influential Bo Jonsson, died in 1386 and was buried in the monastery church. Emperor Charles IV, who was recruited for Birgitta’s cause and issued a supplication in 1377, passed away a year later, as did Pope Gregory XI. Queen Giovanna of Naples, who had sent in one of the first supplications, was murdered in 1382. Archbishop Bernard of Naples, whom we have seen urging for the collecting of miracles, died in 1379. Of these principal characters, King Albrekt, perhaps a somewhat reluctant adherent of the Birgittine movement, was the only one still alive at the time of the canonization. Dethroned and imprisoned, he died in 1412. * * * Poitiers, and Cardinal Guillaume d’Aigrefeuille were members of the first committee for the process, appointed by Gregory XI. Count Gomez (Garcias de Albornoz), the count of Nola (Nicola Orsini), and the knight Latino Orsini belonged to the circle of Birgitta’s close friends in Italy. See Acta et processus canonizacionis beate Birgitte, ed. by Collijn, p. 66 n. 1. 63 The fourteenth century saw only a limited number of completed canonization procedures. One of these concerned St Thomas of Aquinas, who was canonized in 1323, forty-nine years after his death. Birgitta’s contemporary, Catharine of Siena, died in 1380 and was proclaimed a saint in 1461; see Elders, ‘Thomas Aquinas’, and Pásztor, ‘Katherine von Sienna’. For a survey and discussion of late medieval canonizations see Kemp, Canonization and Authority in the Western Church, pp. 107–40 (especially, on St Birgitta, pp. 128–30). The Birgittine Movement & the Canonization of St Birgitta of Sweden 177 Let us now sum up what we have found in documentary texts from these few years in the middle of the 1370s. We have seen Vadstena experiencing initial problems but also funding starting to come in from various directions. Birgitta’s own family and relatives in high places played a part as donors of property and operators in legal matters but also, as we have shown, as promoters of the canonization. Literary works were written for the liturgy, as were a number of supplications to the pope. A case of textual similarity led to the assumption that the Birgitta office of Nils Hermansson might have influenced the first supplication. The international efforts were doubtless crucial for the successful start of the canonization negotiations in Rome.64 Preserved documents show that the Holy Roman Emperor as well as the queen and Archbishop of Naples decided to give their active support. The canonization of Birgitta is a concrete example of Nordic influence in a specific matter, and its success was to a great extent, as we have seen, the fruit of effective lobbying by Swedish groups. In the long run, the activities in these early, formative years were essential in the diffusion of Birgittine ideas and in the establishment of new monasteries all over Europe. 64 And, naturally enough, also for another urgent Birgittine matter, which has not been discussed in this article — the confirmation of the Rule. 178 Claes Gejrot Works Cited Manuscripts and Archival Documents Stockholm, Riksarkivet, MS A 14 —— , MS A 20 Primary Sources Acta et processus canonizacionis beate Birgitte, ed. by Isak Collijn, Svenska Fornskrifts­ sällskapets Samlingar, 2nd ser., Latinska skrifter, 1 (Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1924–31) Äldre svenska frälsesläkter: Ättartavlor utg. av Riddarhusdirektionen, ed. by Folke Wernstedt, 3 vols (Stockholm: Norstedt, 1957–2001) Analecta hymnica medii aevi, ed. by Clemens Blume and Guido Maria Dreves, 55 vols (Frankfurt a.M.: Johnson, 1978) (orig. publ. Leipzig: Rauner, 1886–1922) Birger Gregerssons Birgitta-officium, ed. by Carl-Gustaf Undhagen, Svenska Fornskrifts­ sällskapet, 2nd ser., Latinska skrifter, 6 (Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1960) Birgitta of Sweden, Birgitta of Sweden: Life and Selected Revelations, ed. by Marguerite Tjader Harris and trans. by Albert Ryle Kezel, Classics of Western Spirituality (New York: Paulist, 1990) —— , Opera minora, in Regula Salvatoris, ed. by Sten Eklund, Svenska Fornskriftssällskapet, 2nd ser., Latinska skrifter, 8, 3 vols (Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1972–91), i (1975) Diarium Vadstenense: The Memorial Book of Vadstena Abbey, ed. by Claes Gejrot, Studia Latina Stockholmiensia, 33 (Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1988) Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Johan Gustaf Liljegren and others, 11 vols (Stockholm: Norstedt, 1829–2011) Eusebius Cremonensis, De morte Hieronymi, in Patrologiae cursus completus: series latina, ed. by Jacques-Paul Migne, 221 vols (Paris: Migne, 1844–64), xxii (1845), cols 239–82 Gregersson, Birger, Birgerus Gregorii: Legenda Sancte Birgitte, ed. by Isak Collijn, Svenska Fornskriftssällskapet, 2nd ser., Latinska skrifter, 4 (Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1946) Nils Hermansson, Rosa rorans: Ett Birgittaofficium af Nicolaus Hermanni, ed. by Henrik Schück, Lunds universitets årsskrift, 28: Meddelanden från det litteraturhistoriska seminariet i Lund, 2 (Lund: Lunds universitet, 1893) Ragvald of Linköping, ‘Ragwalds Vita metrica beate Brigide’, ed. by Malin Beji-Wahlström (unpublished licentiate thesis, Stockholms universitet, 1989) Svenskt Diplomatariums Huvudkartotek över Medeltidsbreven (Stockholm: Riksarkivet, 2001) <http://www.nad.riksarkivet.se/sdhk> [accessed 18 March 2013] Vadstenadiariet: Latinsk text med översättning och kommentar, ed. by Claes Gejrot, Kungl. Samfundet för utgivande av handskrifter rörande Skandinaviens historia: Handlingar, 19 (Stockholm: Samfundet för utgivande av handskrifter rörande Skandinaviens his­ toria, 1996) The Birgittine Movement & the Canonization of St Birgitta of Sweden 179 Secondary Studies Aili, Hans, ‘Petrus Olavi’, in Svenskt biografiskt lexikon, ed. by Gören Nilzén and others, 33 vols (Stockholm: Bonnier, 1918–2010), xxix: Pegelow–Ruttig (1997), pp. 221–23 Balteau, J., Michel Prévost, and Roman d’Amat, eds, Dictionnaire de biographie française, 21 vols (Paris: Letouzey & Ané, 1933–2011) Borgehammar, Stephan, ‘Birgittabilden i liturgin’, in Heliga Birgitta – budskapet och före­ bilden, ed. by Alf Härdelin and Mereth Lindgren (Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien, 1993), pp. 299–310 Ekström, Gunnar, Västerås stifts herdaminne, 2 vols (Falun: Falu nya boktryckeri, 1939) Elders, L., ‘Thomas Aquinas’, in Lexikon des Mittelalters, 9 vols (München: Beck, 2002), viii, cols 706–11 Engström, Sten, ‘Birger Gregersson’, in Svenskt biografiskt lexikon, ed. by Gören Nilzén and others, 33 vols (Stockholm: Bonnier, 1918–2010), iv: Berndes–Block (1924), pp. 424–27 —— , ‘Bo Jonsson’, in Svenskt biografiskt lexikon, ed. by Gören Nilzén and others, 33 vols (Stockholm: Bonnier, 1918–2010), v: Blom–Brannius (1925), pp. 82–91 —— , Bo Jonsson I. Till 1375 (Uppsala: Wretman, 1935) Fritz, Birgitta, 600 år i Vadstena: Vadstenas historia från äldsta tider till år 2000, ed. by Göran Söderström (Stockholm: Stockholmia, 2000) Fröjmark, Anders, Mirakler och helgonkult: Linköpings biskopsdöme under senmedeltiden, Acta universitatis Upsaliensis, Studia Historica Upsaliensia, 171 (Uppsala: Historiska institutionen vid Uppsala universitet, 1992) Gejrot, Claes, ‘Att sätta ljuset i ljusstaken: Birgittinsk lobbying vid mitten av 1370-talet’, in Medeltidens mångfald: studier i samhällsliv, kultur och kommunikation tillägnade Olle Ferm, ed. by Göran Dahlbäck and others (Stockholm: Runica et mediævalia, 2008), pp. 91–106 Höjer, Torvald, Studier i Vadstena klosters och birgittinordens historia intill midten af 1400-talet (Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1905) Jönsson, Ann-Mari, ‘Den heliga Birgittas skrinläggning’, Kyrkohistorisk Årsskrift, 87 (1987), 37–53 Kemp, Eric Waldram, Canonization and Authority in the Western Church (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1948) Klaniczay, Gábor, ‘Proving Sanctity in the Canonization Process’, in Procès de canonisation au Moyen Âge: aspects juridiques et religieux, ed. by Gábor Klaniczay (Roma: École française de Rome, 2004), pp. 117–63 Lancaster, Jordan, In the Shadow of Vesuvius: A Cultural History of Naples (London: Tauris, 2005) Léonard, Émile, Histoire de Jeanne Ire, reine de Naples, comtesse de Provence (1343–1382) (Monaco: Imprimerie de Monaco, 1932) Liedgren, Jan, ‘Ärkebiskop Birger som latinsk prosastilist’, Kyrkohistorisk Årsskrift, 80 (1980), 69–73 180 Claes Gejrot Lundén, Tryggve, Nikolaus Hermansson biskop av Linköping: En litteratur- och kyrko­ historisk studie (Lund: Gleerup, 1971) Morris, Bridget, St Birgitta of Sweden (Woodbridge: Boydell, 1999) Nilzén, Gören, and others, eds, Svenskt biografiskt lexikon, 33 vols (Stockholm: Bonnier, 1918–2010) Norborg, Lars-Arne, Storföretaget Vadstena kloster: Studier i senmedeltida godspolitik och ekonomiförvaltning (Lund: Gleerup, 1958) Nyberg, Tore, Birgittinische Klostergründungen des Mittelalters, Bibliotheca historica Lun­d­ensis, 15 (Lund: Gleerup, 1965) —— , Birgittinsk festgåva: Studier om Heliga Birgitta och Birgittinorden (Uppsala: Teo­ logiska institutionen vid Uppsala universitet, 1991) —— , ‘The Canonization Process of St Birgitta of Sweden’, in Procès de canonisation au moyen âge: Aspects juridiques et religieux, ed. by Gábor Klaniczay (Roma: École fran­ çaise de Rome, 2004), pp. 67–85 Olsen, Ulla Sander, ‘Birgittinorden och dess grenar’, in Birgitta av Vadstena, pilgrim och profet (Stockholm: Natur och Kultur, 2003), pp. 377–91 Önnerfors, Alf, ‘Zur Offiziendichtung im schwedischen Mittelalter’, Mittellateinisches Jahrbuch, 3 (1966), 55–93 Pásztor, E., ‘Katherine von Sienna’, in Lexikon des Mittelalters, 9 vols (München: Beck, 2002), v, cols 1072–74 Schück, Herman, ‘Nicolaus Hermanni’, in Svenskt biografiskt lexikon, ed. by Gören Nilzén and others, 33 vols (Stockholm: Bonnier, 1918–2010), xxvi: Fich–Gehlin (1964–66), pp. 602–06 Seibt, Ferdinand, Karl IV: Ein Kaiser in Europa, 1346–1378 (München: Süddeutsch, 1978) Servatius, Viveca, Cantus sororum: Musik- und liturgiegeschichtliche Studien zu den Anti­ phonen des birgittinischen Eigenrepertoires, Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis: Studia musicologica Upsaliensiana, n.s., 12 (Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1990) Ståhl, Peter, ‘Vadstena klosters stora kopiebok: En presentation av handskriften A 20 i Riksarkivet’, Kyrka, helgon och vanliga dödliga: Årsbok för Riksarkivet och Landsarkiven 2003 (2003), 35–64 Vones, Ludwig, Urban V (1362–1370): Kirchenreform zwischen Kardinalkollegium, Kurie und Klientel, Päpste und Papsttum, 28 (Stuttgart: Hiersemann, 1998) Forbidden Marital Strategies: Papal Marriage Dispensations for Scandinavian Couples in the Later Middle Ages Kirsi Salonen T he papal use of its power over Christians in the Middle Ages is mainly understood as unilateral (stipulating norms) and general (norms were similar everywhere). Because of this, canon law is often considered as a homogeneous collection of norms that were interpreted similarly throughout Christendom. This was, however, not the case in reality, as many different local laws and customs altered the interpretation and the application of ecclesiastical regulations. This was especially true in connection with marital matters in the Nordic countries, where a marriage was generally regarded as an economic relationship between two families rather than a religious issue. This article examines the marriage graces (absolutions and dispensations) granted by the Holy See to Scandinavian supplicants in the late Middle Ages. Who were the couples who turned to the apostolic authority in order to legitimize their relationships? Where did they come from? What kind of impediments did they have? What was their social background? In addition to the statistical analyses, this article will discuss the results in the light of the regulations of the Scandinavian provincial laws, and will try to find a special Scandinavian marriage pattern and compare it to the general European one. Kirsi Salonen (kirsi.l.salonen@utu.fi) is a tenure-track professor in Medieval and Early Modern History at Historian, Kulttuurin ja Taiteiden tutkimuksen laitos at Turun Yliopisto. This article was written with the generous support of the Academy of Finland. Medieval Christianity in the North: New Studies, ed. by Kirsi Salonen, Kurt Villads Jensen, and Torstein Jørgensen, AS 1 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013) pp. 181–208 BREPOLS PUBLISHERS 10.1484/M.AS-EB.1.100816 Kirsi Salonen 182 Marriage and Law Canon Law and Marriage The right to make decisions in various marriage matters was reserved for the apostolic authority because the Catholic Church considered matrimony of great importance. It was indeed considered to be a sacrament by the thirteenth century. This attitude has its basis in the Bible, where St Paul defines the Christian marriage between a man and a woman as the living image of the indissoluble union between Christ and the Church.1 The right of the popes to make decisions (i.e. to grant dispensations and absolutions) in marriage matters arose from the fact that the marital impediments were based not on the divine law of the Holy Bible, but on later decisions made by the popes, for example Alexander III (r. 1159–81) and Innocent III (r. 1198–1216), as well as by church councils, Lateran IV, held in Rome in 1215, being the most significant.2 According to the regulations of canon law, the basic rule for a legally valid marriage was that both parties were entering matrimony of their own free will. If not, the Church did not consider the union valid. Canon law regulated the validity of marriages in numerous other ways as well. It stipulated several fundamental impediments which prevented a couple from being legally married. Some of these impediments could be overcome with a papal dispensation, some not.3 The first marital impediment was consanguinity; too close a relation by blood (consanguinitas). Canon law did not permit persons related to each other by the fourth degree (or less) of consanguinity to marry. In practice this meant that marriages between siblings, cousins, second cousins, and third cousins (just to mention some examples within the same generation) were considered illegal.4 The impediment of consanguinity was dispensable in a horizontal line, but if the relationship was in vertical line (for example, between parents and 1 Ephesians 5. 21–33; Matthew 19. 3. Conciliorum Oecumenicorum Decreta, ed. by Alberigo and others, canons 50 and 51 (pp. 257–58). 3 Most of the ecclesiastical legislation concerning marriages that was valid in the late Middle Ages can be found in Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Friedberg and Richter, ii: Decretalium collectiones, x 4 and vi 4 (cols 661–732 and 1065–68). 4 The concept of consanguinity within the four degrees is very complex and contains dozens of different possibilities of consanguinity. In Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Friedberg and Richter, i: Decretum Gratiani, cols 1425–26 there is an appendix called Arbor consanguinitatis, which gives all the possible combinations for the different degrees of consanguinity. 2 Forbidden Marital Strategies 183 children or grandparents and grandchildren) it could not be overcome by dispensation.5 Affinity (affinitas) was the second marital impediment. It forbade marriages in cases when a person intended to marry the close relative of a previous spouse or lover, that is, in cases typically involving the second marriage of at least one of the spouses. Canon law stipulated that marriages were forbidden between persons related to each other up to the fourth degree of affinity. The degree of affinity was counted according to the degree of consanguinity between the new and former partner — a third degree of consanguinity between the old and new partner resulted in a third degree of affinity and so on. Like the impediment of consanguinity, affinity too was dispensable.6 The impediment of public honesty (impedimentum publicae honestatis iustitia) was a form of affinity. According to this regulation nobody could marry a person closely related to his or her previous fiancé or fiancée — unless the couple received a dispensation.7 The fourth marital impediment was a spiritual relationship (cognatio spir­ itualis), and it involved several different possible relationships. The spiritual relationship was based on a tie created by holy sacrament, baptism, or confirmation, and it rendered impossible marriages between a person and his or her godparents or their close relatives. However, also this impediment could be overruled by an apostolic dispensation.8 Canon law stipulated numerous other marital impediments too. One of them was a so-called legal relationship (cognatio legalis) or legal fraternity (fra­ ternitas legalis), which existed between individuals related to each other by the tie of adoption. This impediment too was dispensable. 9 Moreover, a marriage contracted after bride-abduction was not considered valid because at least one of the spouses had not acted voluntarily, but these cases became dispensable 5 On the canon law regulations concerning consanguinity, see Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Friedberg and Richter, ii: Decretalium collectiones, x 4.14.1, 8 (cols 700–01 and 703–04). 6 On the canon law regulations concerning affinity, see Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Friedberg and Richter, ii: Decretalium collectiones, x 4.14.1 (cols 700–01). 7 Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Friedberg and Richter, ii: Decretalium collectiones, x 4.1.4, 8 (cols 662–63). 8 Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Friedberg and Richter, ii: Decretalium collectiones, x 4.11 (cols 693–96). Concerning the different forms of spiritual relationship, see also de Leon, La ‘cognatio spiritualis’ según Graciano. 9 Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Friedberg and Richter, ii: Decretalium collectiones, x 4.12 (col. 696). Kirsi Salonen 184 if the abducted spouse later gave her consent.10 Furthermore, certain persons were not regarded suitable to marry anyone under any circumstances because of some sort of physical defect, for example, impotence, frigidity, or madness, and these impediments were not dispensable.11 Minority was also considered a physical impediment, but it could be dispensed because it was ‘healed automatically’ when the individuals in question reached the required age of consent.12 Men in holy orders or persons who had entered a monastic career could not marry because they had to observe celibacy.13 Scandinavian Laws and Marriage The oldest Scandinavian provincial civil laws seem to have considered marriage mainly as a civil matter, in which the involvement of the Church was not necessary.14 The Christianization of Scandinavia, however, was a turning point in this respect, because the Church insisted on establishing ecclesiastical jurisdiction over marriages. The change in this direction was carried out first in Denmark (the first of the Nordic countries to convert to Christianity), where the ecclesiastical concept of marriage was established at the time of the codification of the local laws. This is reflected in the fact that the codified Danish provincial laws contain practically no references to secular marriage practices.15 The shift took place a bit later in Sweden and Norway, where the codified medieval laws still include a special legislation related to the civil procedure in marriage cases. Marriage legislation is collected in most of the Swedish provincial laws into an entire chapter called giftermålsbalk. In the Norwegian law of the province of Gulathing we find similar legislation in the kvende-burtgiftingbolk and in the law of the province of Frostathing these regulations are included into the 10 Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Friedberg and Richter, ii: Decretalium collectiones, x 4.1.21 (cols 668–69). 11 Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Friedberg and Richter, ii: Decretalium collectiones, x 4.1.24 (col. 670) and 4.15 (cols 704–08). 12 On marriages of minors: Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Friedberg and Richter, ii: Decretalium collectiones, x 4.2 (cols 672–79). 13 Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Friedberg and Richter, ii: Decretalium collectiones, x 4.6 (cols 684–87). 14 On the possible existence of special civil marriage laws in the Danish provincial laws, see Vogt, Slægtens funktion i nordisk højmiddelalderret, pp. 286–87. 15 Kroman and Iuul, Danmarks gamle love paa nutidsdansk. Forbidden Marital Strategies 185 kristendomsbolk.16 Thus in the Swedish and Norwegian laws marriage remained more a secular matter than in Denmark, where the regulations of canon law were predominant.17 The worldly concept of marriage, especially in Sweden and Norway, becomes evident in various ways in the laws. Most concrete is the lack of any mention of a priest in the different stages of marriage: the proposal, the engagement, and finally the wedding.18 Neither do the laws contain references to an obligatory solemnization of the marriage in the church. Furthermore, the marriage regulations of the Scandinavian laws are often in close association with the inheritance legislation, which indicates that the various economic aspects (which had nothing to do with the Church) of the marriage were considered to be of great importance.19 It can be said, in general, that a marriage (especially in Sweden and Norway) was considered more as an economic interaction between two families, represented by the spouses, than as an ecclesiastical matter. Therefore, it seems, many Scandinavian couples assigned less importance to the religious aspects of contracting a marriage. It was clearly more important for them that their marriage was considered legally valid in the eyes of the civil society, which defined the rights of inheritance for their offspring, than in the eyes of the church. This generalization must, however, be considered from a strictly legal viewpoint, and not as the general opinion among the Scandinavians. We cannot ignore the fact that in the late Middle Ages the Scandinavians were as pious as anyone else in the Christian West, and an ecclesiastical blessing of a marriage must have had an important religious meaning for the individuals concerned. The ecclesiastical influence upon the civil legislation concerning marriages is reflected in the later compilations of Swedish and Norwegian civil laws. 20 16 Svenska Landskapslagar, ed. by Holmbäck and Wessén; Gulatingslovi, ed. and trans. by Robberstad. In the Norwegian provincial law of Frostathing these matters are included in the kristendomsbolk. Frostatingslova, ed. by Hagland and Sandes. 17 Concerning the medieval Scandinavian laws and especially their concepts of marriage, see Vogt, Slægtens funktion i nordisk højmiddelalderret; Korpiola, Between Betrothal and Bedding, regarding Sweden in particular; as well as numerous publications of Lars Ivar Hansen regarding Norway, especially Hansen, ‘Slektskap, eiendom og sociale strategier i nordisk middelalder’. 18 Concerning the various phases in marriage, see Korpiola, Between Betrothal and Bedding. 19 This is true also in a Danish context. Vogt, Slægtens funktion i nordisk højmiddelalderret, pp. 156–57. 20 On the discussion regarding the impact of the ecclesiastical legislation on the Swedish laws, see Korpiola, Between Betrothal and Bedding, passim. Her results are, however, not accepted by everyone. For a criticism of her theses, see Vogt, Slægtens funktion i nordisk højmid­ delalderret, pp. 303–04. Kirsi Salonen 186 A good example of this is the way the regulations of civil law reflect or directly repeat in certain circumstances the regulations of canon law, especially the marital impediments. For example, the Swedish Law of Realm stipulated (around 1350) that the offspring of a couple related to each other in a prohibited way were considered to be bastards and had no hereditary rights.21 Consequently, if a couple wanted to ensure the position of their offspring, it was wise to act in a way that was recognized as correct under both ecclesiastical and civil laws. In such cases, an apostolic marriage grace, which guaranteed that a marriage was valid despite an impediment, was the easiest way to ensure the position of the heirs, since such marriage dispensations and/or absolutions automatically contained an explicit reference to legitimization of the offspring. A papal letter of grace was a useful document in this respect, because it was regarded as a legal testimony before both ecclesiastical and civil courts. Legalizing the status of the children was important because an official legitimization would ensure their hereditary rights. In a dubious case, there was always the risk that relatives might claim that the children were not born in legal wedlock and were thus illegitimate and consequently without right to the inheritance. The legitimization of children was especially important for those couples with a considerable patrimony to pass to their heirs. Papal Graces in Marriage Matters The Catholic Church considered marriage matters so important that the handling of such issues was reserved for the papal authority. The papacy could grant dispensations and absolutions to couples who wished to marry or to continue in their marriage (in case they already were married) with someone to whom they were related too closely. Since the pontiffs did not have time to handle all cases submitted to them, they delegated the powers to deal with these matters to the officials of the curia. The Apostolic Penitentiary was the most important papal office that had the powers to deal with these questions. The papal Chancery and the Apostolic Dataria as well as papal legates and collectors — and sometimes even local bishops — possessed a similar authority.22 However, 21 Magnus Erikssons landslag i nusvensk tolkning, ed. by Holmbäck and Wessén, Äkten­ skapsbalken 18: ‘Om horbarn och andra sådana barn, huru de skola ärva. Avlar någon barn i hordom, i skyldskapsbrott, i andligt skyldskapsbrott eller i svågeskapsbrott, de barnen äro skilda från alla arv’ (p. 63). 22 On the Scandinavian faculties of dispensation in marriage matters, see Ingesman, ‘Danish Marriage Dispensations’. Forbidden Marital Strategies 187 it is evident that the Penitentiary was the most important office dealing with marital questions. The Dataria or Chancery only rarely granted such graces, while dealing with such petitions was an everyday business for the officials of the Penitentiary.23 As said above, the papal offices and representatives could grant dispensations for couples who desired to marry despite an impediment. In theory, a couple should have requested a dispensation before contracting their marriage. It should not even have been possible for a couple to get married without a dispensation if an impediment existed between them. According to canon law, it was the task of the local parish priest to check that the couples who came to him to be married were not related to each other in an improper way. To facilitate the task of the parish priest, canon law stipulated that the banns had to be read aloud in the parish church on three Sundays or other ecclesiastical holidays in order to ensure that there were no impediments between the future spouses. If somebody knew a reason why the couple should not be married, he or she was supposed to advise the parish priest. The social control exercised through reading the banns was important, and persons who did not express their doubts or information about the spouses’ relationship were automatically (ipso facto) excommunicated. In the end, it fell to the responsibility of the parish priest to make sure that no impediments existed.24 There were, nonetheless, couples who were married despite an impediment. If the local ecclesiastical authorities later found out about the existence of an impediment, they instituted proceedings separating the couple through a sentence in a local ecclesiastical court. In such a case, only a papal dispensation could help the couple to remain in their marriage. A couple who knowingly married despite an impediment intentionally violated the rules of canon law and incurred excommunication. According to the regulations of canon law, however, a couple who knowingly married despite an impediment could apply to the Holy See for absolution and a dispensation that allowed them to return to the community of Christians and to continue legally in their marriage. Those couples who married in ignorance of the existence of an impediment, on the other hand, did not incur excommunication, 23 Petitions from the territory of the Holy Roman Empire demonstrate that the Penitentiary granted most of the graces related to marital matters, while the other offices handled only a handful of supplications. Schmugge, Hersperger, and Wiggenhauser, Die Supplikenregister der päpstlichen Pönitentiarie. 24 Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Friedberg and Richter, ii: Decretalium collectiones, x 4.1.27 (col. 671). 188 Kirsi Salonen because they had not violated the ecclesiastical norms intentionally. They could remain married after they had received an apostolic dispensation. The couples who obtained a papal marriage grace usually wanted to ensure the position of their heirs by requesting a special legitimization of their children too. What do the papal marriage graces reveal to us? The existing documentation concerning the papal marriage graces consists for the most part of the abbreviated texts recorded in the registers of the Penitentiary, while the other medieval papal register series contain only a few relevant documents. The entries in the Penitentiary registers comprise the most important details concerning the couple and their problem. Each entry begins with the names of the persons who were requesting the grace with a reference to the name of their home diocese. Along with the personal data of the supplicants, the entries contain all the information which the officials of the Penitentiary needed in decisionmaking. The first detail given is whether the supplicants were planning to get married or whether they were already married. In the supplications of already married couples, it is then noted whether they had been aware of the impediment at the moment of their wedding or not. These details were crucial for the decision-making, because the type of grace depended on the circumstances. As noted above, those couples who planned to get married needed only a dispensation, as did those couples who had married in ignorance of impediment. Those couples, instead, who had knowingly married despite an impediment, needed both dispensation and absolution. Furthermore, the already-married couples occasionally mentioned whether they had consummated their marriage or not and if they had children. These facts were, however, not always copied into the Penitentiary registers, since they did not play a role in the decision-making. The petitions always included another very important fact, namely exactly what kind of impediment there was between the spouses. In the case of consanguinity or affinity it was also important to indicate how close the relationship was (second degree was the closest dispensable and fourth degree still needed dispensation). In the case of spiritual relationship the petitioners had to explain what kind of spiritual relation they had, that is, whether the relationship was based on the sacrament of baptism or confirmation. The last piece of information given in the entries concerns the legitimization of the children. In certain entries the fact is mentioned simply with a phrase that the couple wanted to legitimize their offspring. In some other cases the supplicants specified that they desired to legitimize their future children or both existing and future children. Since the legitimization of children did not affect the decision of the Penitentiary this fact has quite often — depending on the scribe — been omitted from the records. Forbidden Marital Strategies 189 Nordic Petitions for Marriage Graces Provenance The later medieval (c. 1450–153025) Nordic sources on the marital problems resolved by the apostolic authority consist of 123 documents. In eighty years, this represents a very small proportion of all marriage cases handled in the papal curia, but nevertheless these graces were of vital importance for the supplicants.26 The majority of these graces, 116 petitions, were handled by the Penitentiary. Only seven dispensations were granted by other papal offices, Chancery or Datary. The dominance of the Penitentiary is not only a Nordic phenomenon, but the same trend applies everywhere — the Penitentiary was the main papal office for handling matters related to marriages. The 123 matrimonial graces represent all three medieval Nordic kingdoms. Table 3 indicates how many cases came from each Nordic church province and individual dioceses as well as how many graces were granted by the Penitentiary and by other papal offices. Scandinavia consisted of three church provinces. The province of Lund covered present-day Denmark and parts of what is now southern Sweden and consisted of seven dioceses: the archdiocese of Lund and the dioceses of Aarhus, Børglum, Odense, Ribe, Roskilde, and Viborg. The Norwegian province of Nidaros (Trondheim) covered present-day Norway, Iceland, some North Atlantic islands, as well as certain eastern parts of Sweden (Härjedalen and Bohuslän), including the following nine dioceses: the archdiocese of Nidaros (Trondheim) and the dioceses of Bergen, Färöar, Gardar (Greenland), Holar, Oslo, Skálholt, and Stavanger, while the Swedish church province of Uppsala covered more or less the rest of present-day Sweden and Finland and included the archdiocese of Uppsala and the dioceses of Linköping, Skara, Strängnäs, Turku, Västerås, and Växjö. 25 This article has been limited to the years from which we possess the surviving Penitentiary records, i.e. from the 1450s until the Reformation period in the Scandinavian church provinces, i.e. in the 1530s. 26 According to the statistics to hand at the moment, in the second half of the fifteenth century (1455–92) the Penitentiary handled 42,691 marriage petitions from all parts of Christendom. Of these only sixty-five (0.15%) came from the three Scandinavian church provinces. On the statistics of the Penitentiary see Salonen and Schmugge, A Sip from the ‘Well of Grace’, pp. 19, 27, 48, 57, 61, 64, and 68. Kirsi Salonen 190 Table 3. The provenance of the Nordic marriage supplications.27 Source: Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonialium et diversorum, vols i–lxxvi.28 Province Diocese Lund Lund Aarhus Børglum Odense Ribe Roskilde Viborg Subtotal Nidaros Bergen Faeroer Gardar Hamar Holar Oslo Skálholt Stavanger Subtotal Uppsala Linköping Skara Strängnäs Turku Västerås Växjö Other Subtotal Nidaros Uppsala Royal Total 27 Penitentiary Other Total Per cent 10 2.5 2.5 4 10 10.5 1.5 41 2 0 0 0 0 0 1 5 0 8 19 3.5 3.5 1.5 35 1 1.5 1 66 1 116 3 1 0 0 0 1 0 5 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 7 13 3.5 2.5 4 10 11.5 1.5 46 2 0 0 0 0 0 1 5 0 8 20 4.5 3.5 1.5 35 1 1.5 1 68 1 123 28% 8% 5% 9% 22% 25% 3% 37% 25% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 13% 63% 0% 7% 29% 7% 5% 2% 51% 1% 2% 1% 55% 100% I have counted each marriage petition as one digit. If the supplicants come from two different dioceses, I have given half a digit to each diocese. Therefore several dioceses have half numbers. 28 Some of the Nordic marriage graces have already been edited. The cases from the province of Nidaros are edited in Synder og pavemakt, ed. by Jørgensen and Saletnich; and the cases from the province of Uppsala in Auctoritate Papae, ed. by Risberg and Salonen. There is a list of all petitions regarding the province of Lund in Ingesman, ‘Danish Marriage Dispensations’, pp. 150–56. Forbidden Marital Strategies 191 The number of marriage graces from each church province varies considerably. The province of Uppsala is represented by sixty-eight cases (fifty-five per cent), while forty-six cases (thirty-seven per cent) are from the Danish province and only eight cases (seven per cent) from the Norwegian province. One case concerns Nordic royals and is calculated separately. If we compare these numbers to the estimated number of inhabitants in Nordic countries, Sweden is clearly over-represented in the number of marriage graces in relation to the other Nordic provinces. The data in Table 3 also shows how many cases came from each diocese. Some differences can be observed between the dioceses within each province. The Danish dioceses of Lund (thirteen cases), Roskilde (eleven and a half cases), and Ribe (ten cases) are quite well represented, while from the other four Danish dioceses, Aarhus, Børglum, Odense, and Viborg, there are only a few cases each. Regarding the Norwegian church province, the marriage graces are clearly concentrated in Iceland (diocese of Skálholt, five cases), while only three cases originate from the Norwegian mainland: two from the archdiocese of Trondheim and one from the diocese of Oslo. The distribution of cases is very uneven in the Swedish church province too: the diocese of Turku is the most numerous with as many as thirty-five cases, and Uppsala is in second place with twenty cases. From the other dioceses there are only a few instances. What could explain such a pattern? One often offered explanation for the varying numbers of cases from different dioceses is the varying number of inhabitants in each region — the more people, the more supplications. This demographic explanation does, however, not hold in the Nordic context. The diocese of Turku was by no means the most densely populated diocese in the North. Neither were there more inhabitants in Iceland than on the Norwegian mainland. One could stick to the demographic explanation and offer the counter-argument that the fewer inhabitants there were in one region, the greater the probability of prohibited interrelations, and the greater the need of a papal dispensation. Such an explanation could fit Iceland in relation to the Norwegian mainland, and Finland in relation to the Swedish mainland, but does not hold in the Danish context. If we observe the distribution between different dioceses, we notice that the diocese of Turku with thirty-five cases is much above any other diocese in the number of cases. The Finnish petitions represent in all twenty-eight per cent of all Scandinavian marriage petitions, which is much more than one could expect from the number of inhabitants or the significance of the diocese. The archdiocese of Uppsala comes in second place with twenty cases, whereas thirteen cases is the highest number of cases from a Danish diocese, that of Lund. In conclu- Kirsi Salonen 192 sion, marriage graces were granted to all Nordic church provinces, but the geographical distribution of these graces was very uneven — for an unknown reason. Nor can we explain these numbers by claiming that the large number of petitions from Turku depended on the excessive wealth of the inhabitants and the consequent need to ensure that the offspring would have all hereditary rights. On Time Axis Graph 3 shows the distribution of the Nordic marriage graces on the time axis. It allows us to analyse whether such petitions were at certain times brought to the Apostolic See more often or whether there were times when such graces were not needed at all. Comparing the results to the historical events in the North could give us information as to the necessity of these graces in different parts of Scandinavia. Graph 3 demonstrates some variation in the number of granted marriage graces. Since the number of Nordic marriage graces is very small, it is not wise to place too much emphasis on statistical analysis, but certain patterns can be observed nonetheless. We see that only one grace was granted before 1458 and that the number of graces in the 1460s varies between nought and three. The near absence of Scandinavian marriage graces prior to 1458 is easily explainable by the fact that the Apostolic Penitentiary only started to record its decisions in that year. It was then that Philippus Calandrini was appointed as the Cardinal Penitentiary and, under his lead, the office adopted an accurate system of recording its decisions.29 Between 1469 and 1481 at least one marriage grace was granted to Scandinavian supplicants each year, the year 1478 having the top figure with five graces. During the 1480s, the number of graces diminished, but the Scandinavians still continued to turn to the papal curia relatively frequently. From the 1490s onwards, this pattern seems to change: there are more years in which no marriage graces were granted, but at the same time more petitions were brought to the Penitentiary during those years when the office handled Scandinavian marriage petitions. This could indicate that couples no longer tended to send their petitions to the curia individually, as earlier, and that obtaining such letters had become professionalized and perhaps dominated by ecclesiastical authorities. It might be that, to some extent, such petitions were 29 On Calandrini’s decisive role in developing the recording system, see Salonen, ‘The Penitentiary under Pope Pius II’, pp. 11–13. Forbidden Marital Strategies 193 Graph 3. Scandinavian marriage graces on the time axis. Source: Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonialium et diversorum, vols i–lxxvi. Kirsi Salonen 194 piled up in ecclesiastical centres and waited there until there were other (similar) supplications to carry to the pope and only then were these sent together to the curia. The contacts between Nordic countries and the papal curia seem to become less frequent during the sixteenth century, but the couples kept turning to the apostolic authority with their marriage problems until the Reformation in the North in the 1520s or 1530s — a fact which demonstrates that marital dispensations were important matters. The decline in the number of marriage graces when approaching the end of the period in question is, however, not necessarily a real tendency, because a number of Penitentiary registers from the sixteenth century are missing, and thus we lack information on possible marriage graces granted by the office.30 One important aspect to consider when analysing the marriage graces on the time axis is the presence of papal nuntii or collectors. The pontifical representatives always had powers to grant similar kind of graces — which evidently resulted with a diminishing need to turn to the Apostolic See. Per Ingesman has listed all faculties given to the papal legates destined for Denmark,31 and Christiane Schuchard has studied all the papal representatives sent to the German Empire, who were usually destined for the Nordic countries as well.32 30 There is only one Penitentiary register missing from the fifteenth century, that of the fifth pontifical year of Pope Alexander VI (August 1496 to August 1497). From the sixteenth century the lacunae are much bigger. The volumes from the second, third, and sixth pontifical years of Julius II (November 1504 to November 1506 and November 1508 to November 1509), the volumes from the first, second, third, sixth, and eighth pontifical years of Leo X (March 1513 to March 1516, March 1518 to March 1519, and March 1520 to March 1521) as well as the volumes from the second, third, and fourth pontifical years of Clement VII (November 1524 to November 1527) have not been preserved to our days, and so there are no graces from these years, as can be seen from Graph 3. On the preservation of the Penitentiary registers, see Salonen, The Penitentiary as a Well of Grace, pp. 425–26. 31 Ingesman, ‘Danish Marriage Dispensations’, p. 157. According to Ingesman, during the period in question in this essay, six papal legates destined for Denmark had obtained faculties to grant marriage dispensations: Marinus de Fregeno, bishop of Kammin for sixty couples on 20 June 1479; Angelus Gherardini, bishop of Suessa for an undefined number of couples on 22 July 1482; Bartholomeus de Camerino similarly for an undefined number of couples on 14 October 1483; Johannes Antonius, Guntherus de Bunow, and Hermannus Tuleman together for an undefined number of couples on 6 April 1487; Bishop Simon of Tallinn for forty couples on 21 May 1488; and Bishop Johannes of Tallinn for an undefined number of couples on 16 April 1515. 32 Schuchard, Die päpstlichen Kollektoren im späten Mittelalter. Persons studied by Schuchard are often the same papal representatives as in Ingesman’s list. Schurchard lists Marinus de Fregeno in the first half of 1460s, Bartholomeus de Camerino in the first half of Forbidden Marital Strategies 195 If we compare Graph 3 to the presence of papal representatives in Scandinavia, we see that during the periods when they were visiting the Nordic countries there are somewhat fewer petitions for marriage dispensations than during the previous years. This indicates that the Scandinavian couples sent their petitions to Rome when they could not receive the graces locally. This makes sense, as it was much quicker and easier to obtain the graces locally. But if there were no possibilities of this, sending one’s application to the papal curia was the only way to settle the matter. Supplicants Social Status Filippo Tamburini has defined the Penitentiary as a ‘papal tribunal for poor people’, because the costs of the graces granted through this office were lower than the costs of the same grace granted through some other papal office, like the Chancery or the Datary. Occasionally the Penitentiary even granted graces for free, if its officials considered the supplicants poor. Recently it has been shown that Tamburini’s definition is not correct, especially in respect to supplicants from Northern Europe, among whom we meet many members of important noble families. However, the presence of the nobility or upper class people among the supplicants cannot be applied to the Penitentiary material as a whole, as Paolo Ostinelli has demonstrated in his studies of the supplications from northern Italy.33 Tamburini’s definition is therefore correct in a certain way, even regarding the marriage graces — as Per Ingesman has demonstrated with the Danish marriage petitions. Even though the majority of the Nordic supplicants came from wealthy families with high social rank, a certain difference can be observed between those who turned to the Penitentiary and those who choose another papal office. According to Ingesman, most Danish couples whose petition was handled in the Chancery were of royal, princely, or noble origin, while the Danish Penitentiary petitioners were mostly noblemen or members of urban the 1480s, followed almost immediately by Raymundus Peraudi and Antonio Mast who stayed in the North until 1491. After a break of some decades, at the end of the 1510s, Archangelo Arcimboldus continued the papal mission of indulgence-selling in the Swedish realm. Many other papal representatives were appointed to the Empire and Scandinavia, but many of them never came to the Nordic countries, remaining instead in the German territory. 33 Ostinelli, Penitenzieria Apostolica. Kirsi Salonen 196 elite. Furthermore, the number of unidentified couples — more likely to be people of middle or lower social strata, of whom there often are no other sources that would permit their identification — is much higher among the Penitentiary petitioners.34 But let us see in more detail what kind of people we find among the Nordic petitioners. It has been possible to identify and thus to determine the social background of the supplicants in eighty-one cases while forty-two couples remained unidentified. All identified couples could be classified as members of the upper social strata. One supplication was made by a couple of royal origin ( Joachim, Margrave of Brandenburg, and Elisabeth, daughter of King Hans of Denmark), while the rest of the identified couples belonged to well-known noble families or to the wealthy urban patriciate. Among the supplicants we find families like Banner, Bielke, Bille, Bonde, Brahe, Fleming, Frille, Gyldenstierne, Horn, Krummedige, Kurki, Renhufvud, Rosenkranz, Scheel, Skytte, Sparre, Store, Tavast, Tott, Trolle, Ulf, and Vasa — some of them even several times. We may therefore conclude that the papal curia and the Penitentiary were definitely not in the service of ‘poor people’ at the Scandinavian level, but that most of the supplicants came rather from wealthy and socially well-established families. One can argue that the one third of supplicants whose identities have not been able to be discovered probably represent the middle or lower classes. The reason for their remaining unidentified is that there is a smaller chance of finding references to the poor in other medieval sources, since they have normally not made donations, sold or bought anything, and are thus more likely to have remained unknown to later periods. It is, in fact, probable that some of the unidentified couples have belonged to this social stratum, but it is also possible that genealogists will manage to identify more of the couples once all Scandinavian documents are edited and accessible to everyone. One Couple, Several Supplications The corpus used in this article consists of 123 supplications presented at the papal curia. Among them, only 113 couples could be found. Why? The answer is simple: some of the couples turned to the apostolic authority more than once. The reason for this is that according to canon law a marriage grace was valid only if all details mentioned in the letter of grace were correct. Thus if something was wrong in their supplication — and consequently in the papal 34 Ingesman, ‘Danish Marriage Dispensations’, pp. 150–51 (Chancery dispensations) and pp. 152–55 (Penitentiary dispensations). Forbidden Marital Strategies 197 letter of grace composed according to the details mentioned in the petition — the grace was void and the supplicants had to renew their request. In the Scandinavian marriage material we find that nine couples have renewed their petitions.35 It was normally sufficient to renew one’s supplication once, but one couple can be found three times in the pages of the Penitentiary register. One Nordic couple who petitioned twice to the Apostolic Penitentiary was Aage Brahe and Johanne (Henriksdatter Sparre) from the archdiocese of Lund.36 Two petitions from them have been recorded — on the same day, 5 October 1524 — on the pages of the Penitentiary register. The first petition, on fol. 190r, says that they were an unmarried couple who desired to get married but could not do so without an apostolic dispensation because Johanne’s first husband, Erik Bille, was related to Aage by the tie of third degree of consanguinity, and Aage’s first wife, Beata ( Jensdatter Ulfstand), was related to Johanne by the tie of fourth degree of consanguinity. Thus between the couple it was a question of impediments of third and fourth degrees of affinity for which they petitioned dispensation together with legitimization for their future children.37 A little further in the same register volume, on fol. 226r, we find another petition from the couple. In that document it is said that Aage and Johanne were a couple who had married each other knowing that Johanne’s first husband, Erik, was related to Aage by the tie of third degree of consanguinity, and that Aage’s first wife, Beata, was related to Johanne by the tie of fourth degree of consanguinity. Hence they petitioned for dispensation to continue in their marriage and absolution because they had broken the norms of the Church, as well as for legitimization for their existing and future children.38 35 Aage Brahe and Johanne Henriksdatter (Sparre) (two times, 5 October 1524); Erik Trolle and Ingeborg Filipsdotter (Tott) (5 and 9 April 1487); Jens Pedersen and Alhein Volteirs (27 November and 24 Deceber 1501); Magnus Nilsson and Alissa Henriksdotter (Horn) (11 October 1469 and 13 September 1470); Peder Lille and Barbara Olofsdotter (9 March 1478 and 16 June 1481); Peter Turesson (Bielke) and Katarina Nilsdotter (Sparre) (26 January and 23 December 1494); Sten Henrikssen (Renhufvud) and Anna Jacobsdotter (Kurki) (13 September 1470, 13 December 1471, and 6 August 1477); Sten Sture and Ingeborg Åkesdotter (Tott) (6 December 1474 and 27 June 1475); and Åke Hansson (Tott) and Katarina Eriksdotter (Bielke) (17 June and 2 October 1507). 36 About Aage and Johanne, see Danmarks Adels Aarbog, ed. by Thiset and others, lxvii (1950), ii, 3–32 (about Brahe-family, esp. p. 11). 37 Città del Vaticano, Archivio Segreto Vaticano, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matri­ monialium et diversorum, lxxi, fol. 190r. 38 Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonialium et diversorum, lxxi, fol. 226r. Kirsi Salonen 198 In their case it is easy to see why the petition has been presented twice. In the first petition they are said to be an unmarried couple without children who desired to marry, while in the second one they are presented as an already married couple who had knowingly contracted marriage and procreated children. But which was the correct one? The other surviving medieval sources do not answer this question because we do not know the date of their marriage. It is known that Beata died on 24 August 1523.39 Since more than a year passed between that date and the date of their petitions, it is possible that the couple had married each other and even had a child, but since the time difference is so short, considering the period of mourning, it seems more likely that the couple simply wanted to marry. Another kind of problem occurred in the case of Magnus Nilsson and Alissa Henriksdotter (Horn) from the diocese of Turku. Their case is handled by the Penitentiary for the first time on 11 October 1469. This document describes them as an unmarried couple who needed a dispensation so that they could marry despite the impediment of the fourth degree of consanguinity.40 Almost a year later, 13 September 1470, they appear again in the Penitentiary register. In this petition they are described as an unmarried couple who wished to contract a marriage but could not do it because of the impediment of third and fourth degrees of consanguinity. 41 Thus Magnus and Alissa needed to renew their grace because in the first dispensation the impediment was not correct. Renewing their supplication a year later was practical, because they could do it together with Alissa’s brother Klaus Henriksson (Horn) and his fiancèe Kristina Kristiansdotter (Frille), who at the same time received a marriage dispensation from the Penitentiary. Renewing their petition after almost a year also meant that Magnus and Alissa had requested their first dispensation well before their planned wedding. Or perhaps they had to postpone the marriage because they could not get married before they had received a valid dispensation. The time between the first and renewed petition could sometimes — but not always — be relatively long. As we learned from the case described above of Aage and Johanna, their new petition is dated on the same day as the first one. Erik Trolle and Ingeborg Filipsdotter (Tott) (who also appear twice in the Penitentiary registers) have a second petition dated four days later than their 39 Danmarks Adels Aarbog, ed. by Thiset and others, lxvii (1950), ii, 11. Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonialium et diversorum, xvii, fol. 51r. 41 Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonialium et diversorum, xviii, fol. 52r. 40 Forbidden Marital Strategies 199 first request. The problem in their case was very simple: Erik was defined in the first petition as a cleric and not as a layman. Since there was no other difference between their two petitions, this minute detail must have been the reason why their first petition was not considered correct.42 The other couples waited from one month to about a year before renewing their requests. The only exception to this is Peder Lille and Barbara Olofsdotter from the diocese of Turku. They received their first dispensation from the Penitentiary on 9 March 1478. In their petition they claimed to be a married couple who had contracted marriage in ignorance of the fact that they were related to each other by the tie of the third and fourth degrees of affinity.43 After almost three years, on 16 June 1481 they turned again to the Penitentiary and requested a new grace, this time absolution and dispensation because they had contracted a marriage despite their being aware of the existing tie of third and fourth degrees of affinity. 44 Thus in their case there had been doubt locally as to whether their first dispensation was valid or not. It is difficult to judge if they had to renew their petition because they had cheated in the first place or whether the second grace was sought more for ensuring the legal position of their children. It is, however, odd that a couple renew their petition after such a long time. One reason might be that Barbara’s uncle Arvid Jacobsson (Garp) was one of the canons of the Turku chapter and might have insisted on the issue. Another motivation for renewing the petition was to ensure the legal position of their offspring. Their son Arvid was entered into an ecclesiastical career, and later, in the beginning of sixteenth century, became a canon of Turku. The latter would have been impossible if there had been some doubt about his legitimacy, since the regulations of the chapter did not tolerate illegitimate children as canons.45 Apart from the couples who have renewed their petitions we also meet one and the same person as supplicant in another context — when intending to marry someone else who also was related to them in a forbidden way. We find three such cases in the Scandinavian material.46 One of those who turned to the 42 Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonialium et diversorum, xxxvi, fols 80v (5.4.1487) and 80r (9.4.1487). 43 Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonialium et diversorum, xxvi, fol. 42v. 44 Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonialium et diversorum, xxx, fol. 103v. 45 Pirinen, Turun tuomiokapituli myöhäiskeskiajalla, p. 238; Salonen and Schmugge, A Sip from the ‘Well of Grace’, p. 263. 46 Erik Eriksen (Banner) with two sisters (1511 and 1517), Anne Mouridsdatter with Oluf Stigsen (1489) and with Predbjørn Podebusk (1507), and Katarina Eriksdotter (Bielke) 200 Kirsi Salonen Penitentiary twice — with two different spouses — was Erik Eriksen (Banner). He petitioned for the first time on 21 November 1511 for a dispensation to marry an unnamed daughter47 of Niels Eriksen (Gyldenstjerne) to whom he was related by the tie of spiritual relationship because his mother was godmother to his spouse.48 We meet him again as supplicant on 24 April 1517, this time together with his wife, Margarethe (Mette), another daughter of Niels Eriksen. They state in their petition that they had knowingly married each other even though Erik had earlier been clandestinely married to Catherina, sister of Margarethe. They obtained from the Penitentiary absolution and dispensation and legitimization for their offspring.49 We also meet Anne Mouridsdatter (Gyldenstjerne) twice among the Peni­ten­ tiary petitioners. Her first petition, made together with her fiancé Oluf Stigsen (Krognos), was for a dispensation that would allow them to marry and was approved by the Penitentiary on 5 November 1489.50 She appears again in the registers of the Penitentiary, almost twenty years later, on 9 December 1507, as a widow who wished to marry the widower Predbjørn Podebusk. They asked for a dispensation so that they could marry despite the fact that Anne and Predbjørn’s first wife had been related to each other by the third degree of consanguinity.51 In these two cases the supplicants had married each other, but in the case of Katarina Eriksdotter (Bielke), who appears in the Penitentiary registers with two different fiancés, we know that she never used the first dispensation granted by the office. Katarina petitioned for the first time to the Penitentiary on 17 June 1507 together with Åke Hansson (Tott) for a dispensation so that they could marry each other despite the impediment of fourth degree of consanguinity.52 Three and half months later the Penitentiary granted them the with Åke Hansson (Tott) (17 June and 2 October 1507) and with Tönne Eriksson (Tott) (1 December 1512). 47 From the later supplication we know that there was question of Catherina, daughter of Niels Eriksen (Gyldenstjerne). 48 Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonialium et diversorum, lvi, fol. 701r. 49 Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonialium et diversorum, lxi, fol. 22r-v. 50 Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonialium et diversorum, xxxix, fol. 14v. 51 Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonialium et diversorum, liv, fol. 371v. 52 Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonialium et diversorum, liii, fol. 131r. Forbidden Marital Strategies 201 same grace for the second time: dispensation from the impediment of fourth degree of consanguinity.53 The reason for the renewal of the petition was probably the fact that in the first petition they were both said to come from the diocese of Skara and that they also petitioned for absolution. In the second petition, instead, they are said to come from the dioceses of Skara and Linköping. On 1 December 1512, Katarina petitioned the Penitentiary for the third time, now together with her husband Tönne Eriksson (Tott). They state in their supplication that they had married each other knowing that Katarina had earlier been engaged to a now deceased man who was related to Tönne in the second degree of consanguinity (i.e. Tönne’s cousin Åke Hansson (Tott)).54 The office granted them absolution and dispensation as well as legitimization for their offspring. These petitions give us a good example of how marriage graces could be requested well in advance of the planned weddings. Actually, one could speculate that perhaps Katarina and Åke had even decided to call off the intended wedding despite the dispensations they had received, since there is no evidence that they ever were married before Åke died three years later in 1510. And we meet Katarina, as soon as 1512, married to Tönne. In any case, this example demonstrates that the existence of a marriage dispensation does not necessarily demonstrate that the supplicants in fact married. There is still one particular phenomenon concerning the marriage supplications brought to the authority of the Apostolic See: they were quite often brought to the Penitentiary together with other similar kinds of supplications — often from the same diocese or, indeed, from the same family.55 A good example of such a practice comes from the Swedish mainland. The Penitentiary handled on 1 September 1493 the petitions of four sisters: Kristina, Lucia, Gunnhild, and Gertrud Petersdotter from the archdiocese of Uppsala. They had all married in ignorance of being related to their husbands by the tie of fourth degree of affinity (which in two cases resulted from a sexual relationship of the men to women related to the sisters by the tie of fourth degree of consanguinity).56 53 Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonialium et diversorum, liii, fol. 194v. 54 Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonialium et diversorum, lviii, fols 164v–165r. 55 On jointly-made petitions, see Salonen, The Penitentiary as a Well of Grace, pp. 256–60. 56 Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonialium et diversorum, xl, fols 3v–4r. Kirsi Salonen 202 What Did the Couples Need? As explained above, the marriage petitions directed to the papal curia contained all (for the decision-making) necessary details about the supplicants and their requirements. We have now analysed the provenance of the supplicants, the distribution of the petitions over time, and the social background of the couples who needed such graces, but not yet concentrated on the actual content of the requests. There are some details that can be studied more closely, namely: whether the supplicants were planning to get married or had already contracted matrimony, what kind of impediments were involved, and what kind of graces did the couples request? Married or Not? Among the 123 Scandinavian requests for dispensation or absolution, slightly more than half (sixty-seven petitions, fifty-four per cent) were engaged couples who wished to get married but could not fulfil their desire without a papal dispensation because of some impediment. These couples who were requesting a dispensation beforehand were acting correctly. Some of the couples who received a grace before getting married were, however, not innocent in the eyes of the church and had to request absolution too. In these few cases, it was a question of spouses who had knowingly fornicated despite an illegal relationship. On the other hand, fifty-five couples explain that they were already married and needed a papal marriage grace, which permitted them to remain in their marriage despite an impediment. Not all of them, however, acted illegally and intentionally broke the regulations of canon law by getting married despite an impediment: for the majority of them, thirty-nine couples (seventy-one per cent), had been ignorant of the existence of an impediment when getting married.57 Thus these couples only needed dispensation in order to continue in 57 The proportion of seventy-one per cent of the pairs being unaware of their relationship seems very high — especially against the idea that (Scandinavian) people in the Middle Ages ‘had a good idea of who were their relatives from both the paternal and maternal sides’, as it was put in Vogt, Slægtens funktion i nordisk højmiddelalderret, p. 30. A similar claim can be found in most of the studies regarding families in the Middle Ages. Against this very established assumption, it would be easy to claim that the couples who claimed ignorance simply lied because — according to the assumption — they must have been aware of their genealogy. However (as it was argued earlier in the context of renewing one’s petition), the curial regulations stated that a papal letter of grace was void if all details were not correct. This is a strong Forbidden Marital Strategies 203 their union. Eleven couples confessed that they had contracted their marriage knowing about the impediment and thus intentionally violated the norms of the church. They needed (and applied for) both absolution and dispensation from the papal curia. In two cases, a pair who had married knowingly about the existence of an impediment requested dispensation only. The missing reference to absolution might result from an error of the scribe who copied the petition to the Penitentiary register, but there is also another common factor in these cases, namely the impedimentum publicae honestatis iustitiae. Additionally, one of the already married couples stated that they were married ‘perhaps knowing’ (for­ san scienter) of the existence of an impediment. Furthermore, one of the already married couples had already been dispensed but they needed an additional letter of declaration for making their marriage valid. Thus they had behaved in the correct way. In one petition the marital status of the couple is not clear, since the wording in the document says that they were ‘perhaps married’ (forsan contracto [matrimonio])58. The Penitentiary treated this couple as if they had already been married and they were granted absolution and dispensation. counter-argument to the assertion that the supplicants simply lied because that made their case look better before the papal officials. The question is, then, why would the couples have lied and therefore risked receiving (and paying for) a void grace rather than told the truth that they were unaware of their relationship? I would argue that most of the couples who claimed that they did not know that they were related were telling the truth. Perhaps we should reconsider our assumption that most medieval Scandinavians knew their family backgrounds very well. This is, however, not the task of this essay. I still want to stress the fact that since most of the people who were unaware of their relationship were related to each other by the tie of fourth degree of consanguinity (meaning that they were third cousins or equivalent) or by the tie of third or fourth degrees of affinity — both relatively distant relations — the claim of ignorance may well be true. Furthermore, the Swedish provincial law of Östergötland stated in Giftermålsbalken, vii § 1 that those who organized a wedding had to invite to the party all relatives within the third degree of consanguinity under the pain of fines (text is in Svenska Landskapslagar, ed. by Holmbäck and Wessén, i, 104). This demonstrates that people might no more have personally known their relatives within the fourth degree of consanguinity — which corresponds well to the results mentioned here. 58 The use of uncertain formularies does not refer to the fact that the pair itself was unaware of whether they were married or not but to the fact that the couple was not present in the curia when their case was handled, and that their representative could not tell the proctor who composed the petition, whether they were married or not. Therefore the proctor chose to use in the petition an all-embracing formulation that would guarantee that the grace would be valid in both cases. Kirsi Salonen 204 Comparing the Scandinavian data to the general trends in the Penitentiary documentation demonstrates that the supplicants from Nordic countries had behaved exactly in the same way as Christians from all over Christendom, of whom more or less half were about to marry and half had already contracted their marriage.59 Impediment The marital impediments stipulated by the Catholic Church were explained above. Among the great mass of marriage petitions presented to the papal curia, the impediments of consanguinity (more than half of the supplications) and affinity (c. 20–25%) were the most common. Spiritual relationship (c. 10%) or the impediment of the justice of public honesty (c. 5%) as well as the other impediments remain much less numerous. 60 How does this pattern fit the Scandinavian marriage material? In the corpus of Scandinavian marriage petitions, there are sixty-four cases (52%) related to the impediment of consanguinity, thirty-seven cases related to affinity (30%), and six cases to both (5%). Thus in this respect the Scandinavian material follows the general trend. Examining the proportions more closely there seem to be a little too few consanguinity cases and a little too many affinity cases in the Nordic material, but due to the small corpus this small variation cannot be regarded as significant. Only nine petitions concern the impediment of spiritual relationship (7%) and in six cases there is question of the impedimentum publicae honestatis iustitiae (5%). One of the petitions involves a totally different situation: a man requests a license to marry a woman with whom he had had a sexual relationship already when his late wife was still alive. If we concentrate more closely on the impediments, we can observe what kind of relationships the supplicants had with, or how close they were to, each other. Of the 123 marital graces granted by the papal authority, 107 concerned degrees of consanguinity or affinity. The great majority of them, seventy-six petitions, regarded the fourth degree, which still required to be dispensed, while only four petitions regarded the third degree. In thirty-nine cases the couples were related to each other by a double (once by a triple) tie of relationship. In twelve cases it was a question of the combination of double fourth degrees, in twenty-four cases of the combination of fourth and third degrees, in two cases of the combination of fourth and second degrees, and once of the combination 59 60 Salonen, The Penitentiary as a Well of Grace, p. 115. Salonen, The Penitentiary as a Well of Grace, p. 113. Forbidden Marital Strategies 205 of third and second degrees. This demonstrates that the Scandinavians tended not to seek dispensations for marrying someone related very closely to them, but that the spouses were typically related to each other rather loosely — but still in a way that they fell within the forbidden degrees. Nine supplications concerned the impediment of spiritual relationship: in five cases the spiritual relationship was caused by baptism, in three cases by confirmation, and in one instance the nature of the relationship was not mentioned. What Kind of Grace Did the Supplicants Ask For? Most of the couples, 103 pairs (eighty-four per cent), were asking for a dispensation. Some requested dispensation in advance and were not guilty of fornication, while others were already married couples who had not known about the existence of an impediment at the moment they contracted their marriage. Absolution and dispensation were requested by eighteen couples who were related to each other in a forbidden way but who nonetheless had intentionally either married or fornicated. One supplicant, who had committed adultery with his future spouse while his first wife was still alive, asked for a licence to marry his mistress; in another case it was a question of receiving a declaratory letter that granted that the marriage of an already earlier dispensed couple was valid. The legitimization of the children of the couples is mentioned in almost all marriage graces. Since this was a detail which did not affect the decisionmaking but was just a formal addition to the marriage grace, the scribes did not always copy this detail properly into the records of the Penitentiary. In general the references to the legitimization of children can be divided into four groups: in twelve cases it is not mentioned at all; in fifty cases (when the couple was about to be married and did not yet have children) legitimization was granted only to ‘future children’; while in thirty-four cases (mostly already married couples) it was granted for ‘existing and future children’; and in twenty-seven cases the fact is mentioned only incompletely. A Nordic Imprint? If we compare the content of the Nordic marriage supplications presented at the papal curia to the general trend in marriage petitions, we notice that the content of Scandinavian requests corresponds very well to the international trend. The impediments of consanguinity and affinity were the most common 206 Kirsi Salonen and most commonly it was a question of fourth degree, that is, of relationships that were not very close. Similarly, the proportions of already married couples and of those who were planning to marry correspond to the general trend. The number of petitions from the Swedish church province (and especially from the diocese of Turku) — in relation to the number of petitions from the two other Scandinavian church provinces — is abnormally high. There are only a very few Norwegian cases and most of them are from the Icelandic diocese of Skálholt. Some Danish dioceses are a bit better represented, but generally there are relatively few Danish cases. No reason for such territorial differences could be found, however. Studying the petitions against time demonstrated that the Nordic marriage petitions were brought relatively evenly to the papal curia. The lack of Nordic petitions from certain years did not usually result from inexistent contacts but from the lack of the Penitentiary records from those years. A slight diminution of the number of petitions could be observed in those years when papal nuntii and collectors, who had powers to grant similar graces, were present in Scandinavia. The Nordic supplicants differ in one respect from the general trend of the petitioners in the Penitentiary material. Most of the Scandinavians could be identified as members of either the nobility or the upper class, while for example the supplicants from northern Italy mainly represent the middle class. This demonstrates that assuring that one’s marriage was ecclesiastically valid and at the same time legally correct was mainly a matter that concerned the wealthy, who wanted to ensure through a papal marriage grace that their offspring were legitimate and thus had all legal rights to inherit from their parents. The reason behind this phenomenon seems to be the local civil legislation which stressed — especially in Sweden and Norway — the worldly function of being married. Forbidden Marital Strategies 207 Works Cited Manuscripts and Archival Documents Città del Vaticano, Archivio Segreto Vaticano, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matri­ moni­alium et diversorum, I-LXXVI Primary Sources Auctoritate Papae: The Church Province of Uppsala and the Apostolic Penitentiary 1410–1526, ed. by Sara Risberg and Kirsi Salonen, Diplomatarium Suecanum, Appendix: Acta Pontificum Suecica, 2 (Stockholm: Riksarkivet, 2008) Conciliorum Oecumenicorum Decreta, ed. by Joseph Alberigo and others (Basel: Herder, 1962) Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Emil Friedberg and Aemilius Ludwig Richter, 2 vols (Graz: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, 1959) Danmarks Adels Aarbog, ed. by Anders Thiset and others, 96 vols (København: Dansk Adels Forening, 1884–2002) Frostatingslova, ed. and trans. by Jan Ragnar Hagland and Jørn Sandes (Oslo: Norske Sam­laget, 1994) Gulatingslovi, ed. and trans. by Knut Robberstad, Norrøne Bokverk, 33, 2nd edn (Oslo: Norske Samlaget, 1952) Magnus Erikssons landslag i nusvensk tolkning, ed. by Åke Holmbäck and Elias Wessén (Stockholm: Nordiska, 1962) Svenska Landskapslagar, ed. and trans. by Åke Holmbäck and Elias Wessén, 5 vols (Uppsala: Geber, 1933–46) Synder og pavemakt: botsbrev fra den Norske Kirkeprovins og Suderøyene til Pavestolen, 1438–1531, ed. by Torstein Jørgensen and Gastone Saletnich, Diplomatarium poeni­ tentiariae Norvegicum (Stavanger: Misjonshøgskolen, 2004) Secondary Studies Hansen, Lars Ivar, ‘Slektskap, eiendom og sociale strategier i nordisk middelalder’, Colleg­ ium medievale, 7 (1996), 103–53 Ingesman, Per, ‘Danish Marriage Dispensations: Evidence of an Increasing Lay Use of Papal Letters in the Late Middle Ages’, in The Roman Curia, the Apostolic Penitentiary and the Partes in the Later Middle Ages, ed. by Kirsi Salonen and Christian Krötzl, Acta Instituti Romani Finlandiae, 28 (Roma: Institutum Romanum Finlandiae, 2003), pp. 129–57 Korpiola, Mia, Between Betrothal and Bedding: The Making of Marriage in Sweden, 1200–1600, The Northern World, 43 (Leiden: Brill, 2009) 208 Kirsi Salonen Kroman, Erik, and Stig Iuul, Danmarks gamle love paa nutidsdansk, 3 vols (København: Gad, 1945–48) Leon, Enrique de, La ‘cognatio spiritualis’ según Graciano, Pontificio Ateneo della santa Croce, Monografie giuridiche, 11 (Milano: Giuffre, 1996) Ostinelli, Paolo, Penitenzieria Apostolica: le suppliche alla Sacra Penitenzieria Apostolica provenienti dalla diocesi di Como (1438–1484), Materiali di storia ecclesiastica lom­ barda (secoli xiv–xvi), 5 (Milano: Unicopli, 2003) Pirinen, Kauko, Turun tuomiokapituli myöhäiskeskiajalla, Suomen Kirkkohistoriallisen Seuran toimituksia, 58 (Helsinki: Suomen Kirkkohistoriallinen Seura, 1956) Salonen, Kirsi, The Penitentiary as a Well of Grace in the Late Middle Ages: The Example of the Province of Uppsala 1448–1527, Annales Academiae Scientiarum Fennicae, Humaniora, 313 (Saarijärvi: Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 2001) —— , ‘The Penitentiary under Pope Pius II: The Supplications and their Provenance’, in The Long Arm of Papal Authority: Late Medieval Christian Peripheries and their Com­ munication with the Holy See, ed. by Gerhard Jaritz, Torstein Jørgensen, and Kirsi Salonen, CEU Medievalia, 8 (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2005), pp. 11–21 Salonen, Kirsi, and Ludwig Schmugge, A Sip from the ‘Well of Grace’: Medieval Texts from the Apostolic Penitentiary, Studies in Medieval and Early Modern Canon Law, 7 (Washing­ton, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2009) Schmugge, Ludwig, Patrick Hersperger, and Béatrice Wiggenhauser, Die Supplikenregister der päpstlichen Pönitentiarie aus der Zeit Pius’ II. (1458–1464), Bibliothek des deutschen historischen Instituts in Rom, 84 (Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1996) Schuchard, Christiane, Die päpstlichen Kollektoren im späten Mittelalter, Bibliothek des deutschen historischen Instituts in Rom, 91 (Tübingen: Niemeyer, 2000) Vogt, Helle, Slægtens funktion i nordisk højmiddelalderret: kanonisk retsideologi og freds­ skabende lovgivning (København: Jurist- og Økonomforbundets, 2005) ‘He Grabbed his Axe and Gave Thore a Blow to his Head’: Late Medieval Clerical Violence in Norway as Treated according to Canon and Civil Laws Torstein Jørgensen O ne of the fields in which supranational and national currents crossed each other in medieval Europe was that of law and legislation. Roman Law, and in turn canon law, seem to have influenced most local and national law codes. On the northern Scandinavian fringes of Europe we find a legislative tradition which to some extent contains older indigenous elements originating from a system of provincial laws. As for Norway, the drawing of a demarcation line between royal and ecclesiastical jurisdiction was a matter of dispute from the late thirteenth century onwards and throughout the Middle Ages. This article presents the main steps of this historical process and focuses particularly on the issue of clerical violence in order to exemplify how matters were actually resolved. On the basis of two diplomas, one addressed to the pope and one to the king,1 written by or on behalf of clerics who had killed someone, this 1 As for the Penitentiary case see Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonialium et diversorum, xl, fol. 320v. Synder og Pavemakt, ed. by Jørgensen and Saletnich, pp. 101–03 and 167–68. The civil case is recorded in Diplomatarium Norvegicum, ed. by Lange and others, i, no. 359. For a discussion of the latter text in relation to other Norwegian homicide cases see Solberg, Forteljingar om drap. Torstein Jørgensen (torstein.jorgensen@mhs.no) is Professor of Church History at Mis­ jonshøgskolen – teologisk fakultet, Stavanger. In 2003–2012 he was co-connected as project leader to Senter for Middelalderstudier (CMS) at Universitetet i Bergen, which in that period was a national centre of excellence. Medieval Christianity in the North: New Studies, ed. by Kirsi Salonen, Kurt Villads Jensen, and Torstein Jørgensen, AS 1 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013) pp. 209–236 BREPOLS PUBLISHERS 10.1484/M.AS-EB.1.100817 210 Torstein Jørgensen essay will outline and discuss the similarities and the differences between the treatment of these cases within the civil and ecclesiastical jurisdictional systems. An overarching aim of this book is to search for particular Nordic imprints on, or variants of, general European traits of development. With similar kinds of cases dealing with clerical homicide treated in Rome and Scandinavia respectively, we have sources at hand that open up this kind of comparative outlook. The main points of this essay will be the status of the principle of privilegium fori, relevant provisions of the law, the format of the supplications, and the aspect of mitigating and aggravating circumstances. Medieval Petitions to the Pope and to the King The late medieval practice of addressing the pope through letters of petition was a tradition with deep historical roots. Over the centuries an increasing number of supplications arrived at the papal curia from all parts of Western Christendom from individuals and groups of people with different needs, in the hope that these could be resolved by the pope. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries the papal court received thousands of petitions every year — either brought to the curia by the supplicants themselves or by couriers. These were treated by the different units of the papal administration, such as the Datary, the Chancery, and the Penitentiary. In principle, all these were to be recorded in register protocols, now organized and kept in the different source collections of the Vatican Archives.2 As for the particular kind of petitions dealt with by the Apostolic Penitentiary examined in this article, the oldest preserved register from this office dates from 1409, but only from the mid-fifteenth century do we find a more complete series of annual register volumes.3 In the Penitentiary petitions, the supplicants asked for some grace from the pope in those matters reserved to papal dispensation, such as violence in which clergymen were involved as perpetrators or victims, marriages and sex in prohibited degrees of kinship and affiliation, clerical careers in certain circumstances, apostasy from monasteries, change of religious orders, and some other specified matters. The graces were granted in the form of absolution, dispensation, licence, or a letter of declaration. 2 That is, the different categories according to which the holdings of the Vatican Archives are organized. 3 On the preservation of the Penitentiary registers, see Salonen, The Penitentiary as a Well of Grace, pp. 425–26. ‘He Grabbed his Axe and Gave Thore a Blow to his Head’ 211 In medieval society, supplications and appeals were also addressed to secular rulers by their subjects. These letters too could deal with a wide range of matters, of which a large portion were cases in which the petitioner had committed some serious crime and needed a final decision from the king, in many cases in the form of a reprieve. The two lines of petitions sent by people of different classes to the supreme heads of civil or ecclesiastical society represent formalized and organized ways of resolving the problems which the senders faced, and which affected not only themselves, but were a matter of concern to society at large. Both kinds were treated according to set rules of procedure and law.4 Clerical Violence in Ecclesiastical and Civil Sources The number of registered cases in the Penitentiary registers from the Norwegian church province of Nidaros is very limited if compared to the number of cases from other church provinces. This applies also to the number of cases dealing with violence and killing in which clergymen were involved as violators or victims. Altogether seventeen Norwegian cases of killing and seven cases of violence are reported in the Penitentiary register protocols under the de diversis formis-category.5 And under the de declaratoriis-rubric6 the number of cases is only ten, all dealing with killing, and all from the dioceses on the Norwegian mainland.7 Of the thirty-four cases from the Norwegian province clerics were involved in twenty-nine cases as perpetrators. The obvious disadvantage with such low numbers is that they are useless for any kind of statistical survey, and consequently rather unable to reveal general tendencies. But low numbers also have their advantages. They give one the opportunity to obtain a good overview of the different details of the Norwegian murder and violence cases that actually took place and were reported to the Penitentiary. 4 For the ecclesiastical procedures see Schmugge, Hersperger, and Wiggenhauser, Die Supplikenregister der päpstlichen Pönitentiarie, pp. 8–51. 5 As the name indicates this rubric includes petitions dealing with a variety of topics. 6 This category contains cases in which the petitioners address the pope in order to obtain some authoritative declaration from the Holy See. All the Norwegian cases derive from clergymen who have been involved in killing or violence, but who plead innocent, and ask the pope for a declaration to confirm their innocence. 7 Synder og Pavemakt, ed. by Jørgensen and Saletnich, pp. 34 and 45. In addition to the five dioceses on the mainland the Norwegian archdiocese included the two dioceses in Iceland, one in Greenland, one in the Færø Islands, and until the 1470s one in the Orkney Islands. Torstein Jørgensen 212 When it comes to medieval sources from ecclesiastical institutions, Norway finds itself in the same situation as the other Scandinavian countries in that the vast majority of this kind of text material was destroyed during the time of Reformation in 1537 and after. Also, if we look into the civil jurisdictional material, very few cases of clerics involved in violence and killing have survived. According to the church historian Oluf Kolsrud, eighteen cases of priests as killers are mentioned in total in Norwegian sources from before 1607, but the majority of these date from the time of Reformation and after. On this basis Kolsrud drew the conclusion that cases of priests committing murder were extremely rare in medieval Norway. The main reason, as he saw it, was the canon law ban on clerics being involved in such matters.8 But Kolsrud was unaware of the Penitentiary textual material which, at least if the above-mentioned twenty-nine cases were only the tip of an iceberg, 9 should show that clerical violence and killing in medieval Norway was not so rare after all. In addition, it is worth noticing that all the Norwegian cases to be found in the Penitentiary registers date from the period between 1450 and the Reformation. There is therefore every reason to presume that similar cases also occurred earlier, that some of these were reported to the pope, but that the records of these cases have since been lost. The case that was sent to the king discussed in the following might as well have been sent to the pope, but since this dates from a period before the surviving Penitentiary petitions it is impossible to know. If we compare the cases from the ecclesiastical and civil sources, both similarities and differences catch the eye. The similarities apply to such aspects as the actual circumstances and situations of the killing, the development of events, weapons used, points of argumentation, and, finally, in the fact that both categories are accounted for in documents with a longer narrative section. When it comes to divergences these are first and foremost to be seen in the different kinds of documents that were produced in the two sorts of cases. In the Penitentiary cases, the documents consist of a supplication for some papal grace; in the civil cases, of ‘letters of proof ’ (provsbrev). In the former instance the sender of the letter was the culprit himself, although in most cases with the help of some professional such as a papal proctor. In the latter instance the persons putting the text on paper were officials at both civil and clerical levels who were commissioned to try the case and to forward their statements to higher 8 Kolsrud, ‘Folket og reformasjonen i Noreg’, pp. 42–43. It is impossible to settle exactly how many of the reserved delicts were actually brought all the way to the papal curia. But there is no lack of examples of such matters that were solved locally. 9 ‘He Grabbed his Axe and Gave Thore a Blow to his Head’ 213 authorities, in most cases to the king. A conspicuous characteristic of the civil cases is the extensive use of witnesses. Texts Since the textual basis of this article consists of only two documents, and these texts provide the basis for the following analysis it is necessary to give a full presentation of the documents.10 I. The Letter of Proof Sent to the King11 To the honourable lord, by God’s grace King Håkon of Norway, sira12 Arne in Brunkeberg, Vigleik at Håtveit, Trond Reidarsson in the district of Berg Hermundsson, and Svein in Aker send Our Lord’s and our everlasting compliments, Our Lord, and their willing service. We declare to you, my lord, that last Wednesday before Crossmess in the autumn [14 Sept] we were at [the vicarage of ] Eik in Lårdal [in the county of Telemark], in the fourth year of Your reign [1357]. I there took proof from sira Guttorm Thorlaugsson who inadvertently killed Thore Rolvsson, and the legal heirs of the deceased were legally summoned. This was the origin of the strife, and the struggle between them, that on the day of Olavsmess last year Thore Rolvsson, his father, and his brother Asmund, came walking to sira Guttorm’s manor Å, which is located in the parish of Høydalsmo. Sira Guttorm offered them food and drink. Rolv talked to sira Guttorm and asked him to give him a scythe, which sira Guttorm gave him. Then Rolv asked him to sell him a leather rope, but sira Guttorm answered: ‘Never is it my habit to sell ropes, rather I shall give it to you’. After that the aforementioned Guttorm threw the rope on Rolv’s lap and said he could keep it. But Rolv got angry, took up a stone which was lying in the fireplace, and intended to hit the priest. After that Rolv was taken and held and sira Guttorm went away from him. He came in again on the floor, but Rolv ran towards him and shoved him. ‘Do 10 The civil case was written down in Old Norse (mid-fourteenth century), the ecclesiastical text in Latin. The original text versions are included as appendices to this article. 11 Diplomatarium Norvegicum, ed. by Lange and others, i, no. 359. 12 Sira is the Old Norse honorific title of ordained clerics. Torstein Jørgensen 214 not shove me’, sira Guttorm said, ‘I will not shove you’. After that Rolv grabbed sira Guttorm [with one hand] on the collar of his cloak and his head with the other. After that sira Guttorm took up a piece of wood and hit Rolv on his hand. Rolv spoke to his sons: ‘Are you really in here?’, he said, ‘Now my both hands are off ’. Then Thore, his son, got up and gave sira Guttorm one blow to his chest and one to his hand and Asmund, his brother, beat him on his arm with his axe so he spilled some blood and sira Guttorm gave way, stepping backwards upon the bench; he grabbed his axe and gave Thore Rolvsson a blow to his head, and from this he died. I took proof about this incident from two witnesses, whose names are Nerid Hallsteinsson and Liv Gunnarsdaughter, who swore with their hand on the Book that it was so, word by word, as already has been stated. I also took proof from sira Guttorm’s witnesses, whose names are Asbjørg Toresdaughter and Gunna Geirulvsdaughter, that sira Guttorm the same day declared the killing on his own head at the farm nearest to the place where the killing had been committed. The aforementioned Guttorm is now in need of God’s and Your grace, My lord, in order to have ‘landsvist’.13 This killing was committed in sira Guttorm’s home, but still outside all other places of peace. As a true confirmation that I did not receive more true proof in this case, we put our seal to this letter, which was written at the date and in the year as already stated. II. The Supplication Addressed to the Apostolic Penitentiary14 Amund Håkonsson, a priest from the diocese of Hamar, explains that he asked a certain Olav Koch, layman and mason from the same diocese, to build a stove for him in his house and agreed with him about a certain price or salary which he immediately paid to the layman. He told the layman a final time to finish the stove. Despite this agreement, the paid salary and the fixed time limit, the layman on purpose and maliciously postponed the work on the stove way beyond the mentioned time limit inflicting great harm on the same petitioner. As if this were not enough he appeared drunk at the same petitioner’s house or home with no intention of continuing the work, but instigated by the devil with the aim of hurting the petitioner 13 That is, the right to live freely in the realm. Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonialium et diversorum, xlv, fols 401v–402r. 14 ‘He Grabbed his Axe and Gave Thore a Blow to his Head’ 215 and adding evil to evil and kill the petitioner if he so could. But the petitioner was not within reach of the layman since he found himself in another place in the mentioned home. Through the petitioner’s family the layman was told and reminded that he had deceived the petitioner in a wicked manner by the promise, the payment, the long time, and the postponement making the petitioner dissatisfied with him and because of the aforementioned also angry with him, and with good reason. The same layman then started to scold, curse, and swear both against the petitioner, although he was not present, and against his family, who were present. He asked in fury where he could find the petitioner to whom he said he would talk because they had some business together. By the same family he was told again and again that in his state of drunkenness and fury he could not see him since the petitioner perhaps would scold him because of the aforementioned matters — being well aware of his drunkenness and fury — and then the layman would start to harm the petitioner more seriously or kill him. Still, the layman got more and more furious and spiteful, and went to the house where he found the petitioner. He placed himself in the doorway so the petitioner could not walk out, throwing out insults and oaths even worse than before. The worst thing was that he put his hand on a big axe and made himself ready and prepared to hit the petitioner and, if possible, kill him. The petitioner, who wanted to, and thought that he could, calm him down by good and flattering words, asked him first friendly to go away from him, saying that he thought he was a friend, and that he hoped that he for the money he had given him would be paid back and rewarded with friendship rather than such insults. He then asked him to put the axe down. The latter answered the petitioner, that if he had not had a special reason he would have dropped and put down the axe. But he continued to hold on to the axe as if he would attack the petitioner. Finally the petitioner realized that in this way he was simply provoking cruelty in him instead of goodwill and friendship, and he also urged the same layman to reason, especially since he had been so drunk and furious, which he could see with his own eyes and had heard by others. He realized that he himself would be without hope to escape, and would come to be hit by the violence of the mentioned layman. For this reason, if he had not returned violence by violence, he would inevitably have ended up in mortal danger. In order to defend himself, and in this way warding off violence by violence, although by the moderation of an immaculate guardian, the mentioned petitioner hit the layman on his arm with a small axe which he had grabbed in order to defend himself. And in order to escape, and to take the axe out of the hands of the layman he raised his small axe against the big [axe] of the layman. Then the iron blade came loose from the handle and fell after a lofty loop right onto the head 216 Torstein Jørgensen of the mentioned layman and hit a wound or an old injury which because of mistreatment and ignorance was already in putrefaction. The blade hit him, not seriously, however, but enough to make the skin break or almost so. Because of this old wound, which was infected inside and which was now opened, the mentioned layman died according to God’s will after seven days or thereabouts, insisting and swearing until his last moment that his death, which he knew was impending, was without doubt a result of the first infected wound. The same petitioner by no means wished the death of the said layman and was not guilty of it in any fashion other than the one described. He is mourning deeply and wishes to serve in his orders and administer at the altar, and to obtain and keep any ecclesiastical benefice which he might already have obtained and which canonically might be bestowed upon him in the future. Nevertheless, it is asserted by some simple people who are ignorant about the law, and probably also envious of the petitioner, that because of what has happened he has made himself guilty of homicide and incurred the stain of irregularity and the sign of inability. In order to silence the mouth of these detractors, the petitioner asks Your Holiness for a declaration stating that the same petitioner on the said premises has neither made himself guilty of homicide nor incurred any stain of irregularity or sign of inability, and in spite of the aforementioned is entitled to serve in his orders and be eligible to obtain and keep liberally and licitly the ecclesiastical benefices, ut in forma. Granted as below, Julianus, bishop of Bertinoro, regent. To be examined by Franciscus Brevius, and committed to the ordinary, who, provided the necessary inquiries confirm the aforementioned, shall declare as has been requested. Rome, at St Peter’s, 15 July 1496. Some Perspectives on the Demarcation Line between Canon and Civil Law in Norway The two cases on the one hand reflect two divergent jurisdictional regimes, and on the other deal with very similar crimes; it is this fact that makes the two documents so relevant for a comparative analysis. The discourse between church and king on the drawing of a valid and functional demarcation line between ecclesiastical and civil law had been an issue in Norway from the arrival of Christianity around the year 1000 and continued throughout the Middle Ages. As background for our comparison between the two documents below, some information about the Norwegian variant of the general European dispute between king and church in these matters is necessary. ‘He Grabbed his Axe and Gave Thore a Blow to his Head’ 217 A milestone in this process was the agreement between King Magnus the Law-Mender and Archbishop Jon Raude, signed in 1277,15 the so-called Compositio Tunsbergensis or the Tønsberg Concordat.16 If we look into the substance of this document,17 the first issue deals with the dispute between king and church over the jurisdiction of certain types of causes. The claim of the archbishop for causes belonging to the ecclesiastical forum to be tried exclusively by ecclesiastical courts was a main point on the old Gregorian programme of libertas ecclesiae. According to canon law this question belonged to the area of ius commune, which implied that it was a matter of universal validity, and as such non-negotiable. The archbishop was, however, well aware that, by this claim for exclusive ecclesiastical jurisdiction, he acted against the people since his claim was against custom, and since the trial of such causes by secular judges was in Norway a practice ex consuetudine antiqua.18 But for Archbishop Jon, who at this time stood steadfast on the statutes of canon law, the regard for custom had to yield to the regard for the universal validity of the ius commune. However, with respect to Archbishop Jon’s claims under the canon law principle of ius particulare, which he also presented on this occasion, matters stood differently. The issue at stake here was the restitution of ecclesiastical privileges which he claimed had been obtained by the church in the preceding twelfth century. The main points were: firstly the right of the church to have a decisive influence on the succession of new kings, and secondly the privilege of having the Crown sacrificed to the church on St Olav’s altar.19 Although the controversy was sharp, both parts had a strong and serious interest in solving the disagreement by negotiation, for the purpose of avoiding perturbacio and preserv- 15 For the research history on this document: Seip, Sættarg jerden i Tunsberg og kirkens juris­ diksjon; Sandvik, ‘Sættargjerda i Tunsberg og kongens jurisdiksjon’; Riisøy, Stat og kirke; Hamre, ‘Ein diplomatarisk og rettshistorisk analyse av Sættargjerda i Tunsberg’; Orrman, ‘Church and Society’, pp. 446–47 and 451. 16 The Norwegian version of the document is called Sættarg jerden. Diplomatarium Islandicum, ed. by Jón Sigurðsson and others, ii: 1253–1350, ed. by Jón Þorkelsson (1893), no. 65. For the Latin text and translation into modern Norwegian see Norske Middelalderdokumenter i Utvalg, ed. by Bagge and others, pp. 136–51. 17 Two historical events lay behind the agreement of 1277: 1) a national gathering in Bergen in 1273 and 2) the Council of Lyon in 1274. 18 Norske Middelalderdokumenter i Utvalg, ed. by Bagge and others, p. 139. 19 From the Law on succession to the throne of 1163 (Norges Gamle Love, ed. by Keyser and Munch, i, 3), and King Magnus Erlingsson’s Letter of Privilege of 1163–72 (i, 442–44). Torstein Jørgensen 218 ing peace.20 The result was, in short, that the Archbishop in these matters was the one to yield by renouncing the privileges bestowed upon the church in the 1160s. But after all, this was no heavy concession, since the privileges had never really been put into effect. Instead the Archbishop obtained the King’s consent to confirm the different rights of the church already stated in the Christian sections of the old provincial law codes and their representations in national laws. The main concession on the part of the king in this agreement was his renunciation of royal jurisdiction in matters ‘que ad ecclesiam spectant mero iure’ (in matters of Church Law) which he, as the document states, ‘renounces fully’ (renunciavit […] omni iuri).21 Such cases were, again in the words of the document: Omnes cause clericorum quando inter se litigant uel a laicis impetuntur, matrimonium, natalium, iuris patronatus, decimarum, votorum, testamentorum — maxime quando agitur de legatijs ecclesijs et piis locis et religiosis —, tuicio peregrinorum visitancium limina beati Olaui et aliarum ecclesiarum cathedralium in Norwagia et eorum cause. Item cause possessionem ecclesiarum, sacrilegij, periurij, usurarum, simonie, heresis, fornicationis, adulterij et incestus et alie consimiles que ad ad ecclesiam spectant mero iure saluo semper regio iure in hijs causis ubicumque debetur ex consuetudine approbata uel legibus regni mulcta pene pecuniarie persoluenda. (Cases in which clergymen are at law with one another or are sued by laymen, matrimonial cases, birth, patronage, tithes, holy vows, wills — especially when gifts to churches are involved — monasteries and holy foundations, protection of pilgrims coming to St Olav’s or other Norwegian cathedrals’ doorsteps. Further, cases concerning church property, sacrilege, perjury, usury, simony, heresy, concubines, adultery and incest, and all other things which in any way may belong to the ecclesiastical forum according to separate jurisdiction.)22 However, the renunciation on the part of the king was, also in these cases, not so complete after all, for at the end of the list a decisive reservation was added, namely that of ‘royal right in cases in which, according to custom or the laws of the country, fines are to be imposed’. It is not difficult in this list to recognize the canon law distinction between cases claimed to belong to ecclesiastical jurisdiction according personal status (ratione personae) and according to contents (ratione materiae). We should also note that the Compositio Tunsbergensis in connection with the criminal 20 Norske Middelalderdokumenter i Utvalg, ed. by Bagge and others, p. 141. Norske Middelalderdokumenter i Utvalg, ed. by Bagge and others, p. 143. 22 Our translation from Norske Middelalderdokumenter i Utvalg, ed. by Bagge and others, p. 143. 21 ‘He Grabbed his Axe and Gave Thore a Blow to his Head’ 219 cases under the second category also touches indirectly on the relation between sin (culpa) and crime (crimen delictum), which is a most interesting question in itself, although it exceeds the scope of this article. The treatment of sin in foro interno was, naturally enough, not a topic of the Compositio, and nor were purely secular crimes (delicta mere civilia). What does appear as a main point of the agreement, however, is an attempt at a clarification of the rights of the church in the treatment of purely ecclesiastical cases (delicta mere ecclesiastica) and mixed cases (delicta mixta) in matters pertaining to forum externum. But unfortunately no detailed reflection is given on the demarcation line between cases ad ecclesiam spectant mero iure and cases to be solved also regio iure. It is also worthwhile noting that the Compositio does not, like the older provincial law codes, contain a separate section of Christian Law (kristenrett). The reason for this seems to have been the fact that the right to compose such a law code at this point of time had become a controversial matter of dispute. And it remained so also in the aftermath of the concordat. The archbishop continued to maintain that this was an exclusive right of the church, whereas the king maintained that it was a matter to be dealt with by king and church in accordance with older Norwegian tradition. Since no agreement on this issue was obtained, Archbishop Jon composed on his own initiative such a Christian Law, which, however, was never recognized by the civil authorities. Nonetheless, it was often in use.23 In anticipation of a new Christian Law, based on approval from both the king and the church, the Norwegian king declared in 1316 and 1327 that the old Christian Law should remain in force. The reference in the Compositio to cases in which fines were involved according to custom and to the laws of the country was also in the decades after 1277 the object of continued dispute. An agreement between King Magnus Eriksson and Archbishop Pål Bårdsson of 1337 prescribing in detail how ecclesiastical and civil judges should share power is a good example of this process.24 Between 1360 and 1380 the civil authorities composed a new Christian Law.25 This gave concessions to the church on several points.26 23 Norges Gamle Love, ed. by Keyser and Munch, ii (1848), 339–86. Norges Gamle Love, ed. by Keyser and Munch, iii (1849), 161–62. 25 For a detailed presentation of the process of development of this issue, see Bøe, ‘Kristen­ rettar’. 26 Nye Borgartings Kristenrett, Norges Gamle Love, ed. by Keyser and Munch, iv (1885), 160–82. 24 Torstein Jørgensen 220 Figure 10. Priestly violence. BAV, MS Vat. lat. 1371, fol. 159r. Reproduced with permission. From the fifteenth century several documents are preserved testifying to how the division of authority between pope and king was handled in this period. In 1458 the Compositio was confirmed in a declaration from King Christian I, the so-called Skara agreement.27 As matters reserved for ecclesiastical jurisdiction, however, the declaration lists only a few of those mentioned in the Compositio: concubines, incest, perjury, and adultery. But the document includes a general reference to ‘many other articles written in the aforementioned composition’ (manghom flerom articulis, som standa j fornefnda composicione). It also adds a new topic: sponsorship (fadderscap). The document also states that many of the old regulations had been violated, and that complaints had come from the clergy about impediments put in their way when trying to execute their rightful duties. What we see here, then, is probably a situation in which the princi27 King Christian was at this time king of Norway, Denmark, and Sweden. Norges Gamle Love: 1388–1604, ed. by Taranger, Johnsen, and Kolsrud, ii (1934), 140–44. ‘He Grabbed his Axe and Gave Thore a Blow to his Head’ 221 pal theory has been more or less intact, whereas the actual practice has not been entirely consistent. In 1478 the issue was again the subject of an attempt at drawing up a demarcation line between ecclesiastical and civil law.28 The issue was dealt with in a joint decree from King Christian I and the Norwegian National Council, the latter chaired by the archbishop and with all the other bishops as members. The decree takes up again some of the delicta mixta listed in the Compositio which entail punishment in some form or another. In particular the document helps to clarify which kind of jurisdiction the two kinds of courts possessed and to what extent they had the right to recover fines in the different kinds of cases. Cases of incest in the first and second degrees, as well as bestiality and sodomy, are declared as mixed cases, and the culprits are to be sentenced as outlaws. Their property should be confiscated and distributed evenly between king and church. Adultery and concubinage in the third and fourth degrees, however, are defined as irrelevant to the king and falling under Church Law only (ath kongens ombodtsmandt skulle ei beware seg meth frille lefnit, hordome eller skild­ skaff i tredie eller fierde, och ingen secht ther aff tage i noger maade). Adultery and bigamy are also to be fined half to the king and half to the church, but the judicial power in these cases is said to belong to the church (faller theris goetz hel­ thenn under kongen och helten under kirken [ ] end dømes skulle thee maall under kirke dome). Perjury is also mentioned as a mixed case, which according to the contents of each case should be tried either by civil or ecclesiastical courts with the right of the respective courts to impose fines in their own cases. These are the only concrete matters mentioned expressis verbis in the four articles of the decree. But it is stated at the end of the document that the judicial power in all other cases should be judged by king or church in accordance with the regulations of Christian Law (Jtem all anner maallefne mellom kirkenn oc kongisdøme skulle bliffve at affver døme oc saager effther som christenretten udviser). Priests as Killers in the Ecclesiastical and Civil Jurisdictional Systems As appears from our above account of the attempts by king and church to settle disputed matters of jurisdiction between the two, clerical killing and violence are not specifically mentioned. We have no sources to testify why this was so, but one possibility is simply that no doubt was raised by any of the parties that the issue in principle belonged to the ecclesiastical sphere, or, as stated in 1478, 28 Norges Gamle Love: 1388–1604, ed. by Taranger, Johnsen, and Kolsrud, ii (1934), 270–71. Torstein Jørgensen 222 that the matter was to be tried in accordance with the regulations of canon law. But, as the two cases in focus in this article show, the reality was not necessarily so straightforward. The surprising point with the two cases of killer priests is that one of them was in fact tried by the civil jurisdictional apparatus and addressed to the king. From this, and a few other similar cases, it appears that the privilegium fori which canon law prescribed for clerics in practice did not necessarily exempt them either from being accused at Norwegian civil courts or from being sentenced to pay compensation to the relatives of the deceased person, as well as different sorts of fines to the king. The two cases, one from the Penitentiary registers and one from the civil system, should throw into relief both the divergence and the coherence between the two ways of dealing with clerics who killed laymen. The two cases also offer a good illustration of how insufficient the preserved accounts are — whether contained in the Penitentiary archives or as occasional letters of proof surviving from this period — if the aim is to obtain an overview of the full course of the cases.29 There are no circumstances recorded of the two cases other than those presented here, since we have no further surviving historical documentation of them. Thus, in the Telemark case we have no sources mentioning any kind of economic settlement between the killer-priest and the family of the deceased, which must also have been an issue. And in the Hamar case we have no information on what happened to the priest when the letter of grace from the Penitentiary arrived in Norway and the facts of his case were tried by his bishop. The civil case30 deals with a priest in the county of Telemark in south-eastern Norway, sira Guttorm Torlaugsson at Høydalsmo, who was sought in his home by some of his parishioners, one Rolv and his two sons, Thore and Asmund. Obviously there had been some previous disagreement between the priest and the laymen, which evolved into a vehement argument, ending up in a brawl and killing. The incident took place in 1357, and the letter of proof, which was addressed to the then reigning King Håkon VI Magnusson, was written down by a neighbouring priest, sira Arne in Brunkeberg, and witnessed by four trustworthy persons in the district, of whom three are women. 29 From other parts of Europe where written sources are preserved in greater quantities we know that the process of addressing the pope in Penitentiary matters involved a complex process with a number of official units taking part, and a number of documents produced. See Ostinelli, Penitenzieria Apostolica. 30 Diplomatarium Norvegicum, ed. by Lange and others, i, no. 359. ‘He Grabbed his Axe and Gave Thore a Blow to his Head’ 223 Also the ecclesiastical case,31 dated 1496, deals with a layman, the mason Olav Koch, who went to see a priest, Amund Håkonsson, in his home in order to solve some matter of dispute between them. The incident takes place somewhere in the diocese of Hamar. The situation escalated from a hot discussion into a fight with the use of different weapons, ending with the death of Olav after seven days. It is of interest in this context to make a more detailed comparison of the two texts, showing that they contain a number of parallel features as well as diverging elements. We will look at the corresponding features first. Corresponding Aspects The fact that both incidents took place at the killer-priest’s home, caused by laymen coming to see the clergymen in order to settle some disagreement, has already been mentioned. In the Telemark case the cause of the conflict is somewhat blurred. The concrete items of dispute are a scythe and a rope, which Rolv and his sons claim were given or sold to them by the priest. One can only speculate as to the real conflict behind this, since it is not likely that three adults from the same family should show up at the home for such small things. Perhaps their visit was an act of revenge for the priest’s men harvesting too much from their fields — by cutting with the scythe and transporting with the rope. Some obscure background seems to have underscored their request, and the men’s requests were taken as highly offensive by the priest. In the Hamar case, the issue of the dispute is a stove, which the mason Olav had promised to make for the priest. The conflict arose from different opinions about the payment and the alleged slow progress of the work of the mason. In both cases the laymen were described as the instigators of the conflict, by appearing at the clergymen’s homes with accusations and offensive words. In Telemark the three visitors are invited into the house and according to custom offered food and drink. Then the laymen state their claim, first about the scythe, which is given to them, and then about the rope, which the priest in anger throws at Rolv. In short, the further details of the escalating conflict are as follows: Rolv threatens sira Guttorm with a stone; Rolv is held, probably by the priest’s servants; Rolv pushes Guttorm; Rolv grabs Guttorm’s scarf with one hand and his head — probably in his hair — with the other; Guttorm 31 Synder og Pavemakt, ed. by Jørgensen and Saletnich, pp. 101–03 and 167–68. Torstein Jørgensen 224 grabs a piece of wood with which he hurts Rolv’s hand; Rolv’s sons, Thore and Amund, attack Guttorm with axes, hitting his chest and hands; Guttorm grabs an axe and kills Thore with a blow to his head. In Hamar the layman Olav comes to the priest Amund’s house in a state of excessive drunkenness and fury. He takes his stand in Amund’s doorway, leaving the priest no way of escape. The priest tries to calm down the intruder with appeasing words, but with no result. From that point matters develop as follows: Amund hits Olav on his arm with a small axe that he had grabbed in self-defence; Amund raises his small axe to avert a blow from Olav’s large axe, the blade from Amund’s axe loosens from the handle and falls after spinning through the air onto Olav’s head; and Olav dies after seven days. In both cases we read that the killer-priests act friendly at the beginning trying to appease the intruders by offering food or kind words, and in each case the murder weapon is an axe. Other corresponding features are the fact that both perpetrators plead innocent on the basis of mitigating circumstances referred to in the argumentation of the two documents. We shall return to this below. Finally, both documents aim at obtaining a letter from the king and the pope, respectively, in order to secure a continuation for the clerics in their positions as local priests. In the former case the letter involved was a so-called lands­ vistbrev, a letter of reprieve, granting the king’s grace and the right to live freely in the realm without the risk of further prosecution and under royal protection against revenge from the family of the victim. In the latter case, the letter applied for was a declaration from the pope to confirm the perpetrator’s innocence, lifting the state of irregularity and granting the right to remain in office.32 Diverging Circumstances Perhaps the most conspicuous difference between the two documents, apart from the fact that they are addressed to different authorities, is that the Telemark case is put down on paper by some official of the district who possesses the faculty of trying the case, whereas the sender, and the original writer, in the Hamar case is the perpetrator himself. In the former case the account is based on the hearing of witnesses on which occasion also the next of kin of the deceased person are present. In the latter case the text is entirely based on 32 Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Friedberg and Richter, ii: Decretalium collectiones, x 5.31.10 (col. 838). ‘He Grabbed his Axe and Gave Thore a Blow to his Head’ 225 the applicant’s own story, although with the reservation that the grace granted depend on the confirmation of the facts by the petitioner’s local bishop, ordi­ narius. This implies that some procedure of trying the facts of the incidents is employed in both cases, in the former instance before the case is sent to the king, in the latter after the decision was made at the curia. Although both priests plead not guilty, they do it in different ways. Sira Guttorm of Telemark admits that his blow with the axe was the direct cause of Thore Rolvsson’s death. On the very same day as the killing took place, in accord with law and custom,33 he went to the nearest farm where he publicly declared himself to have perpetrated the killing. His pleading innocent is therefore based on extenuating circumstances. In the Hamar case, on the other hand, sira Amund tries to raise doubts about the actual cause of Olav’s death. He admits that the blade from his axe landed on the head of the deceased. But the blade loosening from the handle was by no means his fault. And when hitting Olav’s head it happened to reopen an old infected wound. And when it comes to the question of Olav’s death the priest maintains that it was due to reasons other than his blow with the axe. It seems that alcohol was involved only in one of the two incidents. One should, however, not lay too much stress on this, since we know from other cases of violence, both from the Penitentiary and from civil registers, that drunkenness was widespread in Norway at the time, among lay people and clergy alike. When it is mentioned in texts like those discussed in this article, drunkenness is generally applied to the victim and mostly used as a cause to put blame on the deceased or hurt person and to clear the perpetrator.34 What Was at Stake for the Two Killer-Priests? The fact that priests involved in killing could be tried by both civil and ecclesiastical jurisdictional systems shows that they found themselves in deep trouble in both the realm of the kingdom and in that of the Church. The sentence to be imposed on murderers in the Norwegian civil system was outlawry and the confiscation of property. The Norwegian term ubotamann refers to a person 33 This procedure was in accordance with older Norwegian custom. See Frostatingslova, ed. by Hagland and Sandnes, Mannhelgebolk 5. 34 See for instance Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonia­ lium et diversorum, xli, fol. 277r–v; lix, fols 363v–364v; Synder og Pavemakt, ed. by Jørgensen and Saletnich, pp. 68, 97, 138, and 163. Torstein Jørgensen 226 who had committed a crime that was so grave that it could not be compensated by fines; neither to the relatives of the murdered person nor to the king. Often such a person was simply put to death or, if possible, he managed to flee the country. In some instances we know, however, that they remained untouched in their local communities.35 On the other hand, if it was possible for the culprit to persevere with his argument of mitigating circumstances, he would be declared botamann, that is, he would be sentenced to pay compensation to the family of the deceased person, and fines to the king. This is the aim of the letter of proof written in the case of Guttorm. In the ecclesiastical system priests involved in violence and killing became ipso facto irregulars,36 that is, their priestly acts were considered invalid, and in practice they were suspended. 37 If guilt was obvious, the need for a papal absolution, since the act belonged to the reserved delicts,38 was imminent. In cases where guilt could be avoided, and the perpetrator pled innocent, the aim of the petition to the pope was a letter to confirm this innocence. Such a document would have the effect of stopping the mouth of accusers who thought otherwise about the guilt question. It generally also authorized the supplicant to remain in office and be ready for other offices and benefices. An important question has to be raised on the basis of cases like the two recorded here: to what extent did Norwegian killer-priests have to fight in two jurisdictional arenas? Was it normal that both civil and ecclesiastical jurisdictional procedures were applied in the solving of these cases? The fact that the number of cases is so limited, both in the Penitentiary registers, and even more where priests were tried for killing by the civil apparatus, suggests that a definite answer to this question is not possible. The only verifiable conclusion is that in the latter part of the fifteenth century many priests in accordance with ecclesiastical order brought their cases to the Apostolic Penitentiary, and that clergymen from the fourteenth century all the way up to the Reformation were sometimes tried for their acts of killing by the civil jurisdictional system.39 35 Solberg, Forteljingar om drap, p. 28. Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Friedberg and Richter, ii: Decretalium collectiones, x 5.31.10 (col. 838). 37 Sägmüller, Lehrbuch des katholischen Kirchenrechts, i, 226–27; Schmugge, Hersperger, and Wiggenhauser, Die Supplikenregister der päpstlichen Pönitentiarie, p. 99. 38 Provision from Schmugge, Hersperger, and Wiggenhauser, Die Supplikenregister der päpstlichen Pönitentiarie, pp. 9–11. 39 Other cases are from 1347, 1449, 1511, and 1522. Solberg, Forteljingar om drap, pp. 130–31 and 152–61. 36 ‘He Grabbed his Axe and Gave Thore a Blow to his Head’ 227 Mitigating Circumstances as Mentioned in the Two Texts The Telemark and the Hamar texts are both characterized by their aim of acquitting the killers, and are therefore marked by a tendency to emphasize the extenuating circumstances. The Telemark case stresses that the priest was the one who had been approached by aggressive visitors and that he tried to appease the intruders with food and friendly words. It is also stressed that he left the scene of the fight for a moment when he saw the aggressive attitude of Rolv, waiting for the latter to calm down. Against the stone in the hands of Rolv, Guttorm defended himself with a piece of wood. Having been attacked several times, he ended up in a situation without possible escape. Only after being hit on his hand by the axe of one of Rolv’s sons, spilling blood, Guttorm finally grabbed his own axe and gave the layman the deadly blow in self-defence. In the letter of proof this version is confirmed by witnesses who were present. And the official who wrote the letter expressly states that Guttorm had committed his act vfor­ synio — that is, inadvertently or as an unpremeditated act. In the Hamar case the text also states that the layman was the aggressor. Further, it was the layman and not the priest who had violated the agreements between them about the work. In addition he appeared drunk and furious at the priest’s house carrying a big axe, whereas the priest tried to appease the mason with friendly words. The priest was forced into a situation without escape by the intruder, and finally in this situation of imminent danger he defended himself with a small axe whose blade hit the head of the mason by chance. It is also stated that the act was unpremeditated, that the priest mourned the killing, that the death occurred seven days after the fight, and that the cause of the death was an old wound and not the result of the priest’s doing. Finally the text mentions that the dying mason himself several times on his death bed admitted that his death was caused by the old wound and not by the priest.40 40 The emphasis on the fact that the killing had been committed in a situation of self-defence with no possible means of escape is a general pattern to be found in these kinds of Penitentiary cases, and is motivated by canon law statutes. Schmugge, Hersperger, and Wiggenhauser, Die Supplikenregister der päpstlichen Pönitentiarie, pp. 176–78. See especially the decretal Si furiosus, Clem. 5.4.1, in Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Friedberg and Richter, ii: Decretalium collectiones, col. 1184. Torstein Jørgensen 228 Mitigating and Aggravating Circumstances and the Law In order to put the above texts into a wider perspective we shall draw some lines to relevant guiding principles of law and legislation. The basic historical connection between Roman Law and canon law, and the influence of both on civil medieval legislation is, of course, a visible element in this picture. According to older Norwegian legislation free men were entitled to enjoy peace in their own homes.41 Settlements between adversaries were in principle to be handled at the thing and later at court. Attacking free men in their own homes, as happened here, was therefore a violation of national law and custom, and must have been regarded as an extenuating circumstance for both priests. In both of the above cases weapons were employed as means of killing. In the actual incidents these were axes. According to canon law clergymen were not allowed to carry weapons except for domestic and practical purposes,42 such as a small knife for cutting bread.43 The use of axes by clerics as seen in the two cases here, is therefore in principle a violation of canon law. There are clear indications that both priests and laymen in Norway were well aware of this.44 On the other hand, one matter was the written regulations of the law, another was the reality of life. And there is no lack of examples of Norwegian priests armed with heavier weapons such as axes and daggers.45 One crucial point in the trial of the case was in which context the weapon was used, especially, as we have already mentioned, if a situation of self-defence could be established.46 Violence used in self-defence was regarded as an act 41 See for instance, Frostatingslova, ed. by Hagland and Sandnes, Mannhelgebolk 7. See, for instance, Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Friedberg and Richter, ii: Decretalium col­ lectiones, x 3.1.2 (col. 449): ‘Clerici arma portantes et usurarii excommunicentur’. 43 Kuttner, Kanonistische Schuldlehre von Gratian, pp. 342–43; Examples: Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonialium et diversorum, xvi, fol. 128r– v ; xlviii, fol. 428r–v; lix, fols 363v–364v; lxxvii, fols 9v–10r; Synder og Pavemakt, ed. by Jørgensen and Saletnich, pp. 66, 68, 73, 87, 137, 139, 142, and 160; Dan Crisan, ‘Physical Violence and the Church’. 44 Synder og Pavemakt, ed. by Jørgensen and Saletnich, pp. 104 and 169; Solberg, Forte­ ljingar om drap, p. 130. 45 Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonialium et diversorum, xv, fol. 86r; xviii, fols 102v–103r; xxv, fol. 142v; Synder og Pavemakt, ed. by Jørgensen and Saletnich, pp. 77–78, 94, 145–46, and 159; Solberg, Forteljingar om drap, pp. 130–33. 46 Clem. 5.4.1, edited in Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Friedberg and Richter, ii: Decretalium collectiones, col. 1184; Schmugge, Hersperger, and Wiggenhauser, Die Supplikenregister der päp­ stlichen Pönitentiarie, p. 99. 42 ‘He Grabbed his Axe and Gave Thore a Blow to his Head’ 229 within the frames of the law (vis licita). And from the stress placed on this point in both of the above cases we can conclude that the matter was crucial in both legal systems. The term vim vi repellendo47 (averting violence by violence) is a term with deep historical roots in pre-Christian Roman law. In the Penitentiary supplications the term is one of the most frequently occurring points in texts where the petitioner applies for an apostolic declaration of innocence.48 According to canon law there was a decisive limit between self-defence and revenge. Three main circumstances distinguished the one from the other: measure, time, and intention. As for the first point self-defence required the necessary restraint in averting the attack — cum moderamine inculpate tutele. And the violence (vis) of the defender was not allowed to be stronger than that of the attacker. Thus, it was not permitted to use an axe if the assailant used a stick (moderamen ratione instrumenti). And it was not acceptable to hit the head, if the attacker had hit the hand or the leg (moderamen ratione partis).49 Secondly, to be categorized as an act of self-defence the killing had to take place either immediately (in continenti) or as soon as possible (dum primum poterit) after the attack. If the alleged defence occurred some time afterwards (ex intervallo) it was regarded as an illegal act of revenge. And thirdly, it was required that the intention behind the killing was defence, or that it had taken place unintentionally. In the two cases here neither of the culprits complied with the requirement of moderation when it comes to the body parts that they struck. Both hit the aggressors on their head, sira Guttorm after having been hit on the hand, arm, and chest; and sira Amund under the threat of being hit. As for the use of weapons sira Guttorm obviously violated canon law by fighting with an axe of normal size. Sira Amund, on the other hand, used a small axe against the big axe of the attacker, and thus complied with the moderation principle. As for the two last criteria of time and intention, however, both seem to comply. Both killings took place in the heated situation of the fight, and the alleged intention of both priests was to save their own life in a situation of imminent mortal danger with no possible means of escape. 47 Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Friedberg and Richter, ii: Decretalium collectiones, x 5.39.3 (col. 890): ‘si in continenti vim vi repellat, quum vim vi repellere omnes leges imniaque iura permittant’. 48 Schmugge, Hersperger, and Wiggenhauser, Die Supplikenregister der päpstlichen Pöniten­ tiarie, p. 176. 49 Kuttner, Kanonistische Schuldlehre von Gratian, pp. 340–41. Torstein Jørgensen 230 There is no room in this article to go into detail on all the mitigating and aggravating circumstances to be found in the Norwegian material with references to situation. But the most frequently referred points deal with the different use of smaller and heavier weapons, different kinds of dry and bloody wounds caused by the persons involved, instigation by the devil and evil spirits, mourning of the deceased, and the pious intentions of serving at the altar. One point mentioned in one of the two cases here, however, deserves to be mentioned especially, namely that of pulling the hair (depilatio). Tearing one’s opponent’s hair was considered highly disgraceful, especially if the result was that the person fell to the ground. This seems, in fact, to have been a widespread element of manual combat in the late Middle Ages.50 In the Telemark case both pushing and grabbing one’s head are ingredients of the fight, the latter most likely in the manner of pulling the hair. This act is not reported from the Hamar case, but both pulling the hair and pushing to the ground are known from other Norwegian cases brought to the Penitentiary.51 We can only speculate about why this was considered such a disgraceful infamy. The old Norwegian provincial law of the Gulathing, in fact, goes into some detail on this matter, saying: If a man grabs another man in his beard by a hostile hand, he shall pay a full fine to the other. And if a man grabs and pulls another man in his hair he shall pay a half fine. But if he so does and pushes him away it is called rumpling, and he shall pay a full fine. But if men throw away their weapons and go into the hair of one another, it is called ‘venegrin’ [a female way of fighting], and no fines are to be levied.52 The last point here shows that fighting by pulling the hair was regarded as a female act and an assault against the person’s male power and masculinity. Behind this idea lay perhaps the Old Testament story of Samson whose hair was a symbol of his power.53 50 Crisan, ‘Physical Violence and the Church’, p. 15; Solberg, Forteljingar om drap, p. 117. ‘illumque per capillos apprehendens ad terram prostravit’, Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonialium et diversorum, xvi, fol. 128r–v; Synder og Pavemakt, ed. by Jørgensen and Saletnich, pp. 87 and 154. 52 Gulatingslovi, ed. by Robberstad, p. 195. 53 Judges 16. 17. 51 ‘He Grabbed his Axe and Gave Thore a Blow to his Head’ 231 Conclusion With the two documents in focus in this article, containing rather detailed reports about killings committed by clergymen in late medieval Norway, and addressed to pope and king respectively, it has been possible to draw some comparative lines on the actual treatment of such cases within the two jurisdictional realms. Since we have no documentation of the cases whatsoever from other sources, and since the texts at hand only reflect one stage of the juridical process, the insight to be obtained is limited. Nonetheless, it is possible to draw conclusions on some crucial points. First, the two cases render a clear indication that the principle of privilegium fori, prescribed by canon law for clerics, was not in force in all cases. Clergymen who killed someone could also be tried by the civil jurisdictional apparatus. In addition, members of the clergy could also act as officials with formalized commissions within the civil process of bringing the case to the king. The reason behind the latter practice could simply be that they were the only literate persons of the local community. Second, the two kinds of documents differ in the way they were produced. Whereas the petition to the papal curia was set up by the culprit himself or by some professional papal proctor on his behalf, the address to the king is a letter of proof put on paper by some allegedly neutral official with the aim of demonstrating the objective facts of the case, normally by the use of witnesses and representatives from both sides of the conflict. Third, an extensive correspondence can be found in the two of texts. There is every indication, therefore, that the two jurisdictional systems did not exist in totally separate spheres. On the contrary, the pointing out of extenuating circumstances as articulated so clearly in both texts shows that the same rules to clear the petitioner from guilt were valid and in force in both systems. Finally, the very aim of the two letters also seems to have been the same, namely to provide a document from supreme authorities which could liberate the two priests from severe punishment, and to enable them to continue in their office either by confirming innocence against allegations to the contrary or by reprieve on the basis of testified circumstances. Torstein Jørgensen 232 Appendices I) Diplomatarium Norvegicum, i, no. 359. Sinum hæierlegom herra[,] herra Hakone med guds naad Noregs kononge senda sira Aarne a Bruggabergum Viglæikr a Haþueit Þrondr Reidars son i umbode Bergs Hermunda sonar Suein i Akrenom æuerdelaga hæilsu med varom herra ok sina viliulega þionosto. Yddr min herra gerom mer kunnikt at a miduikudagen nesta firir krosmesso vm haustit uoro mer a Eik i Laardale a fiorda are rikis ydars. tok ek prof sira Gudthorms Þorlaugs sonar er af tok Þorer Roofs son vfyrsiniu logliga firirstemdum æruingium hins er dauda. var þetta uphah og vider atta þæira at a Olafs vaukudagen um aret adr komo ga[n]gande hæim til sira Gudthorms til Aar er liggr i Hæidalsmoos sokn Þorer Rools son ok fader hans ok Asmundr broder hans. baud þa sira Gudthormr þæim til matar ok drykkiar. talade þa Rooluer til sira Gudthorms ok bad geua ser æin lia ok sira Gudthormr gaf hanom. Eiptir þet bad Roluer seilia ser æit alreip en sira Gudthormr suarade aldre er ek uan at selia reip en fyr geuer ek þer þet. eiptir þet kastade optnemndr sira Gudthormr i fanget a Rolue ok bad han eiga en Rolluer reidist ok tok up ein stæin er la a arnenom ok uildi slæigit haua presten. eiptir þet uar Rolluer tæikin ok halden en þa gek sira Gudthormr ut i fra hanom ok kom in aptr a goluet en Roluer læipr i mot hanom ok skyuir honom. Skyf eikki mer sagde sira Gudthormr eikki uil ek þer skylua54. eiptir þet gripr Roluer i hauudsmottena a sira Gudthorme en annare til hauudsins. eiptir þet tok up sira Gudthormr eit tre ok slo til Rolfs ok kom a handena a hanom er Roluer talade til sunar sinni ero þit nokot inni sagde Rolluer nu ero af mer badar handaner. eiptir þet lep up Þorer sun hans ok hiogge til sira Gudthorms firir briostet en annat a hondena en Asmundr broder hans slo han a hondena med æiksi sua ut stak blodet um armen a hanom ok sira Gudthormr ooks undan agugr up i pallen ok tok up æiksina ok hiogge til Þores Rofs sonar eit hog i hauudit ok þer af doo han. ok þer um tok eg tuæiggiamanna uittni er sua hæitta Neiridr Halstæinsson ok Liif Gunnars doter er sua soro a bok a sua uar ord eiptir orde sem fyr seigir. tok ek ok uiglysingar uitni sira Gudthorms er sua hæitta Asbiorg Þoresdoter ok Gunna Geirulfsdoter at sira Gudthormr lysty vigi a sik samdægars a nesta by sem uigit uar unnit er nu optnemdr sira Guthormr þuruande guds og ydra nada min herra 54 Skylua is probably a miswriting of skyfua. ‘He Grabbed his Axe and Gave Thore a Blow to his Head’ 233 um lansvistena. Var þetta vig vunnit i hæimili sira Gudthorms og þo uttan alla addra gridastade. ok til sans uitnisburdar at ek fek æigi sannare prof a þesso male þa seitti mer voor insigli firir þetta bref er gort var a tima ok are sem fyr seigir. II) Città del Vaticano, ASV, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matrimonialium et diversorum, xlv, fols 401v–402r Armundus Haquirin presbiter Hamarensis diocesis <exponit> quod, cum alias ipse quendam Olavum Coch laicum murafortis eiusdem diocesis ad fabricandum pro eo certum furnum in eius domo rogasset secumque de et super illius fabrica et pretio sive salario convenisset ipsumque salarium eidem laico illico persolvit eidemque laico terminum, infra quem fornum huiusmodi fabricare deberet, statuisset, tamen idem laicus non obstante conventione et salarii solutione <et> statuitione termini prefatis fabricationem huiusmodi longe ultra terminum predictum in eiusdem exponentis magnum dampnum deliberate et malitiose differebat, et insuper de premissis non contentus ad domum sive habitationem ipsius exponentis non intentione fabricationem huiusmodi proficiendi sed diabolica instigatione animo ipsum exponentem iniuriandi et mala malis aggregandi ipsumque, si potuisset, interficiendi ebrius accessit, ipso exponente non in eiusdem laici presentia sed alibi in habitatione tamen prefata constituto. Cum igitur prefato laico per familiam exponentis aliquantulum ad mentem et ad memoriam reduceretur quod ipse promissione et solutione ac dilatione et tardatione suis prefatis ipsum exponentem male decepisset, adeo quod ipse exponens de eo non bene contentus sed adversus eum premissorum occasione non immerito commotus erat, et tunc idem laicus ad iniurias imprecationes et blasfemias verbales tam contra exponentem, licet absentem, quam eius familiam presentem devenit, interrogatam tandem furibunde ubi nam esset exponens, asserens se cum eo utrumque rem agi contingeret, loqui velle et licet per familiam prefatam sepe iteratisque vicibus ei responsum fuisset et consultum quod ad exponentem ebrius maxime et furibundus non accederet, eo quod cum forte exponens ipse non constito sibi de ebrietate et furia eius ipsum de et super premissis forsan increparet, idem laicus ad iniurias maiores aut occisionem ipsius exponentis devenerit; tamen ipse laicus continuo magis et magis apud semetipsum male sentiens et furiens ad domum, ubi exponentem invenit, accessit stansque in hostio, ne exponens exire posset, iniurias increpationes et blasfemias prioribus longe acriores in exponentem dixit et fecit ymmo quod peius est; manum ad arma, videlicet ad quandam magnam securim, apposuit seque, ut exponentem percuteret et, si posset, interficeret, disposuit et paravit; Torstein Jørgensen 234 et deinde exponens ipse volens et credens eum ita semetipsum bonis et blandis verbis mitigare, eum a se inter cetera amicabiliter recedere rogavit dicens quod eum amicum suum esse putaret quodque amicum pro pecuniis suis, quas ei dederat, quam similes iniurias refundi et retribui speraret rogansque eum, ut securim de suis manibus secure deponeret et dimitteret, cui respondit quod nisi certa obesset causa, inveniret et sentiret securim ipsam ab eo dimitti et deponi et continuo ipsam securim, ut exponentem aggrederetur, attigit. Tandem exponens videns se magis crudelitatem illius potius suscitare quam benevolentiam et amicitiam sic captare, reducens etiam in memoriam dicti laici, presertim dum foret in tanta55 ebrietate et furia constitutus tam oculari experientia quam etiam relatione plurimorum, austeritatem attendensque nullam sibi fuge spem vimque sibi a dicto laico inferri, ex qua, nisi illam vim vi repulisset, mortis periculum inevitabiliter incurrisset, idem exponens se defendendo et vim huiusmodi vi cum moderamine tamen inculpate tutele repellendo eundem laicum in brachio cum quadam parva secure, quam pro sui corporis defensione acceperat, ad effectum, ut effugere manus illius posset, percussit, et cupiens eiusdem laici securim ab eius manibus eripiendam, <cum> suam securim parvam in illius magnam elevaret, ferrum a ligno ipsius parve securis exiliit et parumper in altum prosiliens retrocedit in eiusdem laici caput, et quoddam vulnus seu antiquam lesuram, iam ex negligentia vel alias ex imperitia putrefientem, licet in modico, videlicet ad rupturam cutis vel circa offendit, ex quo vulnere antiquo interius putrefacto sic aperto dictus laicus post septem dies vel circa, sicut Domino placuit, expiravit, protestans et iurans in extremis mortem, quam imminere cognovit, ex primo vulnere putrefacto infallibiliter evenisse. Et licet idem exponens in mortem dicti laici minime aspiraverit neque alias, quam ut premittitur, in illius morte, de qua plurimum dolet, culpabilis non fuerit cupiatque in suis ordinibus etiam in altaris ministerio ministrare et beneficia ecclesiastica quecumque et qualiacumque per eum hactenus forsan obtenta et in futurum sibi canonice conferenda recipere et retinere, a nonnullis tamen simplicibus et iuris ignaris ac ipsius exponentis forsan emulis asseritur ipsum propter premissa homicidii reatum incurrisse irregularitatisque maculam sive inhabilitatis notam contraxisse; ad ora igitur talium etc. <et aliorum sibi forsan in futurum obloqui volentium emulorum> obstruenda, supplicatur etc. <Sanctitati Vestre> quatenus ipsum propter premissa nullum homicidii reatum incurrisse nullamque irregularitatis maculam sive inhabilitatis notam contraxisse, sed premissis non obstantibus in dictis ordinibus ministrare et beneficia 55 The original writes tantis here instead of the expected tanta. ‘He Grabbed his Axe and Gave Thore a Blow to his Head’ 235 huiusmodi recipere et retinere libere et licite posse, declarari misericorditer mandare dignemini, ut in forma. Fiat ut infra, Iul<ianus>, episcopus Brictonoriensis, regens; videat eam dominus F<ranciscus> Brevius, Iulianus; committatur ordinario, ut, si vocatis vocandis sibi constiterit de assertis, declaret ut petitur. Rome apud Sanctum Petrum, id. iul. anno quarto domini Alexandri pape sexti. Works Cited Manuscripts and Archival Documents Città del Vaticano, Archivio Segreto Vaticano, Penitenzieria Apostolica, Registra matri­ monialium et diversorum, XLV Città del Vaticano, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Vat. lat. 1371 Primary Sources Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Emil Friedberg and Aemilius Ludwig Richter, 2 vols (Graz: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, 1959) Diplomatarium Islandicum, 16 vols (København: Möller, 1857–1972) Diplomatarium Norvegicum, ed. by Christian C. A. Lange and others, 22 vols (Oslo: Malling, 1849–1995) Frostatingslova, ed. by Jan Ragnar Hagland and Jørn Sandnes (Oslo: Samlaget, 1994) Gulatingslovi, ed. by Knut Robberstad (Oslo: Samlaget, 1952) Norges Gamle Love: anden række, 1388–1604, ed. by Absalon Taranger, O. A. Johnsen, and Oluf Kolsrud, 3 vols in 5 (Christiania: Grøndahl, 1912–76) Norges Gamle Love indtil 1387, ed. by Rudolf Keyser and Peter Andreas Munch, 5 vols (Christiania: Gröndal, 1846–95) Norske Middelalderdokumenter i Utvalg, ed. by Sverre Bagge and others (Bergen: Univer­ sitets­forlaget, 1973) Synder og pavemakt: Botsbrev fra Den Norske Kirkeprovins og Suderøyene til Pavestolen 1438–1531, ed. by Torstein Jørgensen and Gastone Saletnich, Diplomatarium Poeni­ tentiariae Norvegicum (Stavanger: Misjonshøgskolen, 2004) 236 Torstein Jørgensen Secondary Studies Bøe, Arne, ‘Kristenrettar’, in Kulturhistorisk Leksikon for Nordisk Middelalder fra vikingtid til reformationstid, ed. by Lis Jacobsen and John Danstrup, 22 vols (Oslo: Gyldendal, 1956–78), ix: Konge–Kyrkerummet (1964), pp. 298–304 Crisan, Dan Sebastian, ‘Physical Violence and the Church: The De declaratoriis Sup­ plications from the German-Speaking Area during the Pontificate of Paul II’ (un­ published master’s thesis, Central European University, Budapest, 2006) Hamre, Lars, ‘Ein diplomatarisk og rettshistorisk analyse av Sættargjerda i Tunsberg’, Historisk Tidsskrift, 83 (2003), 381–431 Kolsrud, Olof, ‘Folket og reformasjonen i Noreg’, in Heidersskrift til Gustav Indrebø på 50-årsdagen 17. november, ed. by Hjørdis Johannessen and others (Bergen: Lunde, 1939), pp. 23–53 Kuttner, Stefan, Kanonistische Schuldlehre von Gratian bis auf die Dekretalen Gregors IX: systematisch auf Grund der Handschriftlichen Quellen dargestellt, Studie e testi, 64 (Città del Vaticano: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 1935) Orrman, Elias, ‘Church and Society’, in The Cambridge History of Scandinavia, ed. by Knut Helle, 1 vol. to date (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003– ), i: Prehistory to 1520, pp. 421–62 Ostinelli, Paolo, Penitenzieria Apostolica: le suppliche alla Sacra Penitenzieria Apostolica provenienti dalla diocesi di Como (1438–1484), Materiali di storia ecclesiastica lom­ barda (secoli xiv–xvi), 5 (Milano: Unicopli, 2003) Riisøy, Anne Irene, Stat og kirke: rettsutøvelsen i kristenrettsaker mellom Sættarg jerden og reformasjonen, Publikasjoner fra tingprosjektet, 22 (Oslo: Universitetet i Oslo, 2004) Sägmüller, Johann Babtist, Lehrbuch des katholischen Kirchenrechts, 4 vols (Freiburg: Herder, 1914–34) Salonen, Kirsi, The Penitentiary as a Well of Grace in the Late Middle Ages: The Example of the Province of Uppsala, 1448–1527, Annales Academiae Scientiarum Fennicae, Humaniora, 313 (Saarijärvi: Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 2001) Sandvik, Gudmund, ‘Sættargjerda i Tunsberg og kongens jurisdiksjon’, in Samfunn, rett, rettferdighet: Festskrift til Torstein Eckhoffs 70-årsdag, ed. by Anders Brattholm and others (Oslo: Tano, 1986), pp. 563–85 Schmugge, Ludwig, Patrick Hersperger, and Béatrice Wiggenhauser, Die Supplikenregister der päpstlichen Pönitentiarie aus der Zeit Pius’ II. (1458–1464), Bibliothek des deutschen historischen Instituts in Rom, 84 (Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1996) Seip, Jens Arup, Sættarg jerden i Tunsberg og kirkens jurisdiksjon (Oslo: Dybwad, 1942) The Lars Vit Case: A Fragmentary Example of Swedish Ecclesiastical Legal Practice and Sexual Mentality at the Beginning of the Fifteenth Century Bertil Nilsson T his article deals with an ecclesiastical juridical case concerning a rector and canon who was removed by the bishop’s judgement because of his way of life. The judgement had reference especially to his sexual excesses, which had resulted in a number of children, but also to other types of criminality about which we do not know anything more precisely. The rector paid a high fine to the bishop, but he also turned to the pope with the help of the reigning Queen Margareta, since he regarded himself as having been unjustly treated. The result at the curia is not possible to determine, but as a consequence the bishop regarded it necessary to once again summon the witnesses to confirm their earlier testimonies against the rector. Thanks to the fact that the minutes from the interrogations are preserved we know the sexual nature of the rector’s crime in greater detail; we also learn about the sexual mentality among ordinary women in Sweden in the beginning of the fifteenth century. Introduction During the years 1410 and 1411 a legal case took place concerning a rector and canon named Lars Sunesson Vit (Laurentius Hwiit)1 in the diocese of 1 It should be noted that Lars Vit cannot be found among the canons in the two diocesan annals (Swedish: herdaminne) of the diocese of Linköping written in 1846 and 1919 respec- Bertil Nilsson (bertil.nilsson@religion.gu.se) is Professor of the History of Christianity at Göteborgs Universitet. Medieval Christianity in the North: New Studies, ed. by Kirsi Salonen, Kurt Villads Jensen, and Torstein Jørgensen, AS 1 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013) pp. 237–260 BREPOLS PUBLISHERS 10.1484/M.AS-EB.1.100818 238 Bertil Nilsson Linköping in Sweden.2 The case is comparatively well documented and concerns a parish priest and his way of life, especially in relation to women. At the same time it should be pointed out that the number of preserved sources concerning parish priests’ lives in Sweden are in general very small; and thus only a very few can throw light upon Lars Vit’s life when looking at the closest Swedish context. However, from the documents concerning his case we can also draw insights into how such a priest could be legally treated when he did not live up to the ecclesiastical demands of clerical continence,3 and how he was able to continue the case in a higher court of appeal. Due to the scarcity of source material it cannot be known how representative Lars’s life was among the Swedish clergy during the late Middle Ages, but it may be assumed that his way of life as a whole was not especially common: if it were, we should have more parallel examples to adduce, even though the source material is only preserved at random. It is quite clear, at least, that many priests around the turn of the fifteenth century failed to remain celibate.4 This was a general phenomenon in the whole of the Western Church and not something typically Swedish, even if we, in contrast to the Lars Vit case, do not know in such detail of other priests’ failures to live up to the Church’s prescriptions. In any case, no other Swedish case has such a wealth of detail. Erik Gunnes has studied the demand for celibacy and its observance in Norway. In the Norwegian diplomatic material he has found only thirteen examples, which all belonged to the first half of the fourteenth century when the bishops either — most commonly — threatened the priests with punishments if they continued their life together with women or — in only a few cases — actually suspended them.5 Certainly it is not possible to make statistical caltively, despite the fact that he became canon on 31 December 1400 and, thus, held the position for ten years before he was removed from the office. One gets the feeling that his life story perhaps has not been suitable for those who wrote the annals. 2 Since this article was accepted for publication, my attention has been drawn to another very recent article about the same Lars Vit, but from a different perspective: Mornet, ‘Le Crime du chanoine’. It has not been possible to take the author’s results into consideration in this piece. 3 On the demand for celibacy in canon law, see Nilsson, ‘A Fight against an Intractable Reality’, pp. 596–98. 4 See Nilsson, ‘A Fight against an Intractable Reality’, pp. 616–17. 5 Gunnes, ‘Prester og deier — sølibatet i norsk middelalder’, pp. 27–28. The cases are found in Diplomatarium Norvegicum, ed. by Lange and others, iii (1855), nos 74, 84, and 85; iv (1858), no. 79; ix (1878), nos 109, 110, 111, 112, 115, and 119, but none of them is as detailed as the Lars Vit case. The Lars Vit Case 239 culations on the basis of the preserved Swedish material, but, as Gunnes himself observed, it does give the impression that priests who lived in matrimony or concubinage were rarely subjected to reprimands or punishments by their superiors, even if the bishops stressed repeatedly that their prescriptions be obeyed. It should also be noted that in one of the cases discussed by Gunnes it might have been that the incontinent rector became a pawn in a game between the bishop of Bergen, who had forced him to leave the rectory, and the archbishop of Nidaros, who intervened and reinstalled him. No other lengthier case is known in Norway regarding the question of celibacy. In Denmark Torben K. Nielsen6 has investigated the role of the prescriptions regarding celibacy in the contacts between Archbishop Anders Sunesen of Lund and the papal see without finding any individual cases at the parish level which resulted in an ecclesiastical judgement. The period under his investigation is certainly short, 1198–1220, but still it seems that no such cases have been preserved for posterity from the Danish church province from the Middle Ages as a whole.7 Material in the Apostolic Penitentiary from the latter part of the fifteenth century from the church provinces of Uppsala and Nidaros respectively only confirms that clerics in holy orders had children and in all likelihood lived in solid concubinages. From Nidaros there are examples concerning brothers who sent supplications to the Penitentiary for dispensations in order to be allowed to become priests, and from Finland, namely the diocese of Turku in the church province of Uppsala, the son of the provost received a dispensation and was then in the service of several bishops, who certainly must have been aware that the provost had children.8 Thus it should be regarded a rather uncontroversial statement that the parish priests in the Scandinavian realms, as well as elsewhere in the Western Church, had children. What makes the Lars Vit case different is that, among other things, he was brought before the bishop’s court because of this fact. 6 Nielsen, Cølibat og kirketugt. Private correspondence from Torben K. Nielsen to Bertil Nilsson, 28 April 2008. 8 Salonen, The Penitentiary as a Well of Grace, pp. 350–52; Salonen, ‘Introduction’, p. 65; Nilsson, ‘Förbjudna kvinnor och barn i medeltida prästgårdar’, pp. 65–67 and n. 74. See also Schmugge, Kirche, Kinder, Karrieren, especially diagram p. 183, where he states that in the Penitentiary archives from the years 1449–1533 there are as many as 21,301 illegitimate children whose fathers were in holy orders. 7 240 Bertil Nilsson Lars Vit is Sentenced to Removal The oldest record belonging to the Lars Vit case is dated 29 April 1410 and issued by Bishop Knut Bosson of Linköping.9 Bishop Knut belonged to the high nobility and the family Natt och Dag. He was elected bishop of Linköping in 1390 and died as such in the year 1436, after a forty-five year episcopate. His attitude and changing loyalties towards, on the one hand, his own cathedral chapter and, on the other, the reigning queen of the Kalmar union Margareta, are also reflected in the lawsuit against Lars. The bishop’s letter is addressed directly to Lars who then was rector of the parish of Säby in the hundred (Swedish: härad) of Norra Vedbo in the province of Småland and at the same time canon of the cathedral of Linköping since, probably, 31 December 1400.10 The letter starts with an account of the criminal acts of which the rector was guilty. He was pointed out and addressed directly by the bishop as a notorious lecher (publicus et notorius fornicator es) who had begotten a number of children and also deflowered a virgin (deflorator virginis) whose confession he had earlier heard. He had often been involved in controversies and contentions with his parishioners and others, in Säby and in Motala, where he had been a minister earlier. For that reason such hatred had been provoked between him and the parishioners that it had not been possible to suppress it. This fact had brought with it danger for their souls, disgrace, and death (animarum pericula, scandala et mortis occasio). Had he been a layman, the bishop continued, he would have been sentenced to exile long before, like his adherents. Furthermore, he had ignored his obligations towards the parishioners so that several had died without receiving the sacrament of penance and other sacraments.11 In addition he was engaged in and stained by other very serious crimes (as the text puts it). Therefore he was not suitable to 9 Svenskt Diplomatarium, ed. by Silfverstolpe, ii (1875), no. 1290. About the letter, see also Bäärnhielm, ‘Bock i prästagård’, p. 22, who deals with it very briefly. 10 On the last subject, see Brilioth, Svensk kyrka, kungadöme och påvemakt, pp. 363 and 373. 11 Because of the scarcity of source material from the church province of Uppsala it is worth noting that complaints of exactly the same kind are documented in the year 1492, when parishioners in Somero in the diocese of Turku (Finland) accused their rector of having neglected to administer the sacraments to the poor and dying; see Finlands medeltidsurkunder, ed. by Hausen, v: 1481–95 (1928), no. 4434. Of course, no binding conclusions can be drawn from this fact concerning the conditions during Lars Vit’s time, but it is still obvious that also in the beginning of the fifteenth century there were priests who received complaints from their parishioners for having neglected their office. In all likelihood this must have been a well-known phenomenon, though the documentation is scarce. The Lars Vit Case 241 hold a priestly office and an ecclesiastical benefice, since it led to disgrace for the church and danger for the souls in his care. Hereafter information follows about the measures taken by the bishop in his capacity as judge (sedendo in iudicio). The document makes clear that the bishop had summoned Lars before his court and that he had proved to be guilty after testimonies had been given. Therefore, the bishop wrote, in accordance with prescriptions of canon law and as a consequence of the fact that the administration of justice demanded it, he had lovingly exhorted Lars to refrain from everything that had occurred so far and to change his way of life. Moreover, he had suspended him from his office and deprived him of his benefice, namely the canonry at the cathedral of Linköping and the prebend in the parish of Säby. Furthermore he excommunicated Lars and ordered him not to remove any of his possessions in Säby or in other places before he had paid his way with regard to the debts that he had to the church in Säby. Finally the text states that this judgement had been read aloud in the chapter-hall in the cathedral of Linköping in the presence of, besides the bishop, the members of the chapter and also other ‘trustworthy clerics and laymen’. The last remark in the letter of judgement shall be seen in the light of opinions that manifested themselves in canon law already in the Decretum Gratiani around the year 1150 and were even more emphasized in the later normative sources added during the thirteenth century, especially the Liber Extra from 1234. There it was stressed that the cathedral chapter should be present and even formally corroborate the judgement when the bishop exercised his jurisdiction. Thus, this meant a limitation of his sole right to exercise potestas iuris­ dictionis and a tendency to strengthen the role of the chapter with regard to the government of the diocese. From the Swedish church province there are several examples showing that the chapter was present when the bishop pronounced a sentence.12 In the Lars Vit case, as we have seen, the members of the chapter and others were at least allowed to listen to the bishop’s judgement in the chapter-hall, but it is uncertain whether this fact should be regarded judicially as the chapter giving its assent to the judgement, especially since the audience contained clerics who were not canons, as well as laymen. The bishop’s letter does not make clear every detail of Lars’s crime, but the fact that he had children who were born after he had received holy orders was enough for the bishop to punish him in the way he did, that is, with the loss of office and benefice.13 However, this type of punishment did not necessar12 13 See Inger, Das kirchliche Visitationsinstitut, pp. 382–87 and 460. See Nilsson, ‘A Fight against an Intractable Reality’, p. 597. Bertil Nilsson 242 ily last for ever.14 Instead the punished priest had the possibility of being reinstated. But Lars had also sinned within the sexual sphere by deflowering a confessant. According to the synodal statutes which Bishop Nils Hermansson of Linköping issued during his episcopate in 1374–91, sexual intercourse with a confessant belonged to crimes that were classified as casus episcopales,15 that is, those to be handled with regard to penal law and church discipline by the bishop only, not a priest, unless the sinner was in danger of his life. This shall be seen in the light of the fact that the bishop, as iudex ordinarius according to canon law, was the most eminent administrator of the sacrament of penance in his diocese.16 Thus, Bishop Knut in this case acted entirely in accordance with prescriptions in international canon law as well as diocesan instructions issued by one of his predecessors. However, Lars’s transgressions and problems were not only about sex; he was guilty of other crimes that pertained to the bishop’s jurisdiction. Without being precise concerning details, the bishop stressed that Lars had been involved in conflicts with his parishioners, which in some cases were very serious. It is not possible to determine exactly what the conflicts had been about, and the meaning of the words ‘had had death as a consequence’ remains unclear. It is probably too much to suggest that he himself was the cause of someone’s death and at the same time too little to think that this only concerned his crimes against the demand for celibacy,17 especially since the bishop emphasized that Lars, according to the law of the realm, would have been sentenced to exile had he not been a priest. Thus, Lars in this respect was protected by the clerical privilegium fori, whence it followed that his case was handed over to the church’s institute of penance instead of being handled within the framework of secular penal law. In connection with this his adherents and accessories are mentioned, but nothing more becomes clearer other than that they must have been laymen who supported Lars Vit and, as it seems, that they had already been punished. This may have concerned the accusation of causing death which the bishop mentioned, but we cannot be sure.18 14 See Plöchl, Geschichte des Kirchenrechts, ii, 391. Statuta synodalia veteris ecclesiae sveogothicae, ed. by Reuterdahl, p. 63. See also undated statutes from the diocese of Linköping, p. 82, no. 22. 16 For this, see Inger, Das kirchliche Visitationsinstitut, pp. 114–16. 17 So Schück, Ecclesia Lincopensis, p. 102. 18 ‘Si laycus esses, secundum constituciones patrie sicut sequaces et complices tui fuerunt exilio dampnati, dudum dampnatus fuisses’. 15 The Lars Vit Case 243 Thus, on the basis of the bishop’s wording it is not possible to determine what crimes Lars was guilty of having participated in, and due to a lack of other sources nothing more concrete can be said. In the law of the realm of King Magnus Eriksson from around 1350, there are a number of crimes that should lead to banishment, which after all gives a hint as to the nature of Lars’s and his accessories’ crimes. Banishment was imposed particularly for crimes against the edsöreslagstiftning (legislation on the king’s peace), gathered in the edsöres­ balk of the law of the realm, but this punishment could be used also for homicide. The edsöreslagstiftning was guaranteed by the king’s oath (hence the name edsöre, from ed and svära, Cf. German Eidschwur) and contained laws aiming to protect the individual’s peace. To this belonged peace with regard to home, women, thing, and church and also unjust revenge and mutilation. In the law of the realm the punishment for crimes against the edsöre was formulated as follows: ‘Whoever breaks the edsöre, and how many they are in company, they have forfeited everything they own above the earth [i.e. all personal property but not the landed property] and they shall be biltoga [outlawed] in the whole of the realm’.19 In addition to the sexual offences and the other crimes within the moral sphere Lars had also neglected his clerical office. Moreover he had debts, a fault which in fact was not punishable but meant additional disadvantage when he was deprived of his sources of income at the same time as his own resources were sequestrated. Furthermore, we should not forget the more theological aspects that were emphasized in the bishop’s letter, namely that Lars’s way of life and his neglect had caused danger to other persons’ souls and thus to their eternal wellbeing. Even if this was a standard formulation, it was still regarded as grounded in reality. With regard to sexual crimes, Gratian in his Decretum had already provided thorough definitions.20 The church demanded that sexual violations, fornication, and rape belong to the so-called crimina ecclesiastica and therefore be handled by ecclesiastical courts, even when the culprit did not belong to the clergy. It seems as if the secular authorities in Sweden, at a comparatively early stage with regard to Swedish conditions (i.e. during the first half of the thirteenth century), had accepted this canonical demand in the field of penal law, since 19 Magnus Erikssons landslag i nusvensk tolkning, ed. by Holmbäck and Wessén, Edsöres­ balken 24 (pp. 194 and 207 nn. 63, 64). 20 Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Friedberg and Richter, i: Decretum Gratiani, Dict. post c. 2, C 36, qu. 1 (cols 1288–89). Bertil Nilsson 244 they were regarded as crimes against religion.21 Even if the church’s demand for privilegium fori for the clergy and religious persons (religiosi) was in some aspects opposed in Sweden by the secular authorities at least until the latter part of the thirteenth century,22 when this privilege seems to have been accepted, it must be regarded as uncontroversial that Lars, at the beginning of the fifteenth century, should be sentenced before the bishop’s court also because of his violation of the confessant. Moreover, according to the church law (kyrkobalk) of the provincial law of Östergötland, which dates from the beginning of the fourteenth century and remained in force in the diocese of Linköping, the fine for fornication was given to the bishop irrespective of whether the guilty person was a layman or a cleric, although the law did not expressly state before which forum the case should be handled.23 Lars Vit Pays a Fine Even if nothing is said about a fine in the judgement of 29 April 1410, Lars did pay one to Bishop Knut of Linköping on 7 June the same year. This becomes clear from a letter which Lars wrote, where he described himself as ‘former rector in Säby’. Here he stated that he had been a criminal without specifying in what ways, and therefore voluntarily gave what is then enumerated to his ‘spiritual father’, the bishop of Linköping. He also pointed out that it was a question of ensaksböter, that is, that the bishop alone should receive the fine. Among the things that went to the bishop were: Lars’s ‘case’ with its content, which amounted to ‘almost one hundred marks’; as well as a number of horses, oxen, sheep, and pigs; all the malt, rye, and flour which he possessed; all the pork; and also the best feather beds and cushions. The following formulations are certainly not all that clear, but it seems that a part of all things that Lars handed over to the bishop should be regarded as compensation for the expenses that 21 Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, i, no. 215; Inger, Das kirchliche Visitationsinstitut, pp. 171–72. The document which bears witness to this fact is a royal letter of ratification of an earlier privilege for the bishop of Skara. However, the dating is very uncertain and is set to the years 1222 to 1250, see Stockholm, Riksarkivet, Svenskt diplomatariums huvudkartotek över medeltidsbreven, no. 410. Concerning the Svenskt Diplomatariums huvudkartotek, see <http://www.riksarkivet.se/default.aspx?id=8004&refid=8005> [accessed 10 February 2013]. 22 Inger, Das kirchliche Visitationsinstitut, pp. 173, 218, and 250; Inger, ‘Skänninge möte 1248 ur rättshistorisk synpunkt’, pp. 186–87. 23 Inger, Das kirchliche Visitationsinstitut, p. 194. The Lars Vit Case 245 the bishop had incurred during his journey in the diocese to clear up ‘the matters’ which had taken place between the parish of Säby, a person named Eskil Djäkne, and Lars himself. Lars went on by forswearing that the content of his letter would be the subject of appeal or withdrawal or would be left without measure, since he had written it out of free will and with honest intent. At the side of his own seal were attached that of his brother, who was rector of the parish of Gränna (not far from Säby), and those of two other named persons.24 According to the legislation a fine was normally a sum of money, but in all likelihood the most common way of paying was with possessions and/or goods as Lars did.25 In the Swedish provincial laws, as well as in the law of the realm, there are examples of fines being paid in goods. In the vådamålsbalk (i.e. ‘the code of corporal offences committed accidentally’) of the Östgötalaw it was prescribed among other things that a fine should be paid with ‘oskuret kläde och lärft och vadmal och reda penningar och unga hästar och nöt’ (uncut cloth and linen and frieze and ready money and young horses and neat cattle). 26 In this case it concerned manslaughter or if anyone had inflicted what were called ‘full wounds’ (fulla sår) upon a person. In the rättegångsbalk (i.e. ‘the code of judicial procedure’) of the law of the realm there were similar prescriptions decreeing that belongings and land should be paid as a fine.27 Although all comparisons are difficult to make concerning the amount of a fine it is no exaggeration to say that Lars’s fine was very high. At the same time it becomes unclear exactly how his letter corresponds with the bishop’s judge24 Stockholm, Riksarkivet, Svenskt diplomatariums huvudkartotek, no. 17500 = Svenskt Diplomatarium, ed. by Silfverstolpe, ii (1875), no. 1310. 25 Hasselberg, ‘Böter, Sverige’, col. 522. 26 Magnus Erikssons landslag i nusvensk tolkning, ed. by Holmbäck and Wessén, Öst­ götalagen Vådamåls­balken 6, § 1. 27 Magnus Erikssons landslag i nusvensk tolkning, ed. by Holmbäck and Wessén, Rätte­ gångsbalken 20: ‘Nu blir en man lagligen sakfälld för sina brott. Då skall målsäganden fara till tinget och tillsäga häradshövdingen. Häradshövdingen skall utse åt honom tolv män från tinget. Dessa tolv skall gå till bondens gård. De skall utmäta lösöre och levande boskap. Räcker det inte till, då skall de utmäta säd och hö […]. Räcker det inte till, då skall man utmäta hans hus. Räcker det inte till, då skall man utmäta hans utjord. Räcker den inte till, då skall man utmäta bolbyn, efter som de tolv säger vara dyrast i värde’ (Now a man becomes legally convicted of his crimes. Then the prosecutor shall go to the thing and tell the district judge. The district judge shall appoint for him [the prosecutor] twelve men from the thing. These twelve shall walk to the farmer’s house. They shall distrain upon personal property and living cattle. If this is not enough then they shall distrain upon corn and hay […]. If this is not enough then they shall distrain upon his house. If this is not enough then they shall distrain upon his utjord [a smaller piece of land]. If this is not enough then they shall distrain upon the village, what the twelve say is most valuable). 246 Bertil Nilsson ment in this respect. In Lars’s letter from 7 June only ‘the matters’ that had been in the parish of Säby are expressly mentioned, but he regarded at least some of the goods that he delivered to the bishop as compensation for ‘the time when he [the bishop] travelled and took the trouble’ with the mentioned ‘matters’. We have no more information than that, but according to Lars at least a part of the fine was a sort of procuration — that is, the fee paid by the clergy in commutation of the entertainment formally provided for the bishop and his escort at his visitations and other types of visits that he made by virtue of his office in the parishes of his diocese. At all events, the fine which Lars had paid cannot be considered only as a punishment. It should also be noted that he did not mention anything at all in the letter concerning his sexual criminality. The ‘Eskil Djäkne’ mentioned by Lars was the trustee (syssloman) of the monastery of Vadstena and appears in a number of affairs between 1406 and 1416 involved with the monastery’s extensive properties and economic interests. 28 That Lars had had some conflict with Eskil throws light upon the fact that the bishop in his judgement also pointed out that Lars had debts to Vadstena, although we hear nothing further on that matter. As far as we can follow the development today, the first phase of the Lars Vit case ended with his letter of 7 June 1410. There remain a number of questions due to the brittle character of the source material, but it seems reasonable to reconstruct the course of events in the following way: the rector in Säby had been removed from office and benefice through the bishop’s judgement according to canonical regulations. This was a consequence of Lars’s crimes (both sexual ones and other types), which all pertained to ecclesiastical jurisdiction, since the privilegium fori had been accepted in Sweden. He had confessed the crimes, paid the fine, and at the same time settled the economic debts to the bishop — a compensation for procuration which Lars had not paid before. Lars Vit Applies to the Pope Rather shortly after Lars had written the aforementioned letter there was a continuation, namely when he applied to the pope by personally going to Bologna where the curia was located until the summer of 1411.29 This becomes clear from 28 See for instance Stockholm, Riksarkivet, Svenskt diplomatariums huvudkartotek, nos 16785, 17051, 17455, 17893, 18043 = Svenskt Diplomatarium, ed. by Silfverstolpe, ii (1875), nos 783, 966, 1368, 1627, and 1744. 29 See Brilioth, Svensk kyrka, kungadöme och påvemakt, p. 245 n. 1. The Lars Vit Case 247 a letter from Bishop Knut’s representative at the curia, Peter Holmstensson, who wrote home to the bishop from Bologna during Lent in 1411. No other document from the following conflict has been preserved, and thus we have to be content with looking at it in the way it was described by Peter. From his letter it is evident that Lars had reached all the way to the pope with his matter. The letter contained an attack on Bishop Knut, which had been brought up in a public consistory where also the cardinals and other persons were present. Lars’s purpose with the visit to the curia was to force Knut to present himself personally there. For this he had the support of Queen Margareta, who was in opposition to Bishop Knut as well as to the cathedral chapter of Linköping concerning the appointment of the bishop of Strängnäs. At the same time Bishop Knut, for other reasons, was on a collision course with his own chapter. Added to this was the looming papal schism between Gregory XII (1406–15) of the Roman obedience, and Alexander V (1409–10), elected by the Pisa council, between whom bishops had to choose their allegiance.30 During 1410 the Danish queen changed her mind and started to support Alexander, and Bishop Knut became reconciled with his chapter, which also was loyal to Alexander rather than Gregory. Thus, all three — the bishop, the queen, and the chapter — were now on the same side in the papal schism. As a consequence Lars’s actions became dangerous for Bishop Knut, because Lars put him in opposition to the reigning queen before the council’s pope, who after Alexander’s death in spring 1410 was John XXIII (1410–15). At the same time it seems that there also were circumstances concerning Bishop Knut’s way of handling his office, as well as his way of life, for which he could be attacked. For instance, we are informed that he had great debts to the Strängnäs church which ought to be paid and furthermore it was desirable that he amended his behaviour. Lars also handed over a letter from the queen to the pope in which she expressed her support for Lars. When this had been done, the pope had stated that the queen hardly would act in favour of such a person as Lars had he not been treated unjustly (si non fuisset injuste spoliatus et indebite grauatus). However, Pope John changed his mind when he was informed about what Lars had been accused of, and even if it is not expressly written in the letter, this must have had to do which his sexual transgressions, which becomes clear from the further development of the case in Sweden. Therefore, according to the pope, it was enough that Bishop Knut answered through a deputy, rather than travelling to Bologna himself. 30 On the conflict concerning the appointment to the episcopal see in Strängnäs, see Schück, Ecclesia Lincopensis, pp. 100–02. Bertil Nilsson 248 According to the letter its author at the same time suspected that the queen would bribe the judge ‘because the queen has here at the curia a number of benefactors who are blind thanks to her gifts’. This fact might have the result that the case would be brought one step further and so become an even more expensive affair for Bishop Knut. It also becomes clear that Peter had been forced to defend his bishop against the queen and her support for Lars.31 Less than a year after Lars had been sentenced by the bishop of Linköping, confessed, and paid the fine for his crimes, he presented himself at the curia and, with the queen’s support, claimed innocence or at least that he had been treated unjustly. However, it seems that he did not mention the real reasons as to why he had been condemned in Linköping, at least if we may trust Peter Holmstensson’s letter. On the other hand, there is no reason to believe that Peter, as the bishop’s representative and also the person who had reprimanded him, by writing that he ought to change his behaviour and pay his debts would have told him half-truths in what was for the bishop so important and serious a matter. Obviously Lars must have had influential friends at home to receive the queen’s support and to reach the highest leaders of the Church. But it is not possible to determine who those persons were with the source material presently available. These persons had quite likely known why Lars had been sentenced but obviously they paid no attention to it. It is not clear how Lars presented his case at the curia and in precisely what way he regarded himself as having been unjustly condemned, which at least from the very beginning was the impression that he managed to give the pope. As has already been established here the bishop of Linköping acted in accordance with the prescriptions of canon law, but despite that, Lars regarded himself free to make an appeal to a higher legal authority, although he had confessed his crimes and paid the fine and thus had regarded himself as guilty. Testimonies Are Given about Lars Vit The third and last phase of the Lars Vit case, as far as we are aware, took place during the summer of 1411. The threat of an expensive trial at the curia which concerned Bishop Knut was probably the reason why he summoned the witnesses against Lars Vit to confirm the evidence that they had given earlier. 31 Peter Holmstensson’s letter is to be found as a copy in Johan Hildebrandsson’s copy book in Uppsala Universitetsbibliotek, Codex Upsaliensis C 6, fols 21v–22r; Brilioth, Svensk kyrka, kungadöme och påvemakt, pp. 244 and 247 and notes; Schück, Ecclesia Lincopensis, pp. 102–03; Bäärnhielm, ‘Bock i prästagård’, p. 22. The Lars Vit Case 249 Their explanations provide us with some insights into the sphere of sexual mentalities and they also show that it must have been his transgressions in this sphere, and not the other crimes that Lars had committed, that made the pope change his mind, as already mentioned, concerning the necessity of Bishop Knut’s presence at the curia. In connection with the interrogations that were held in the Dominican convent in the town of Skänninge on 5 June 1411, a so-called notarial instrument (notariatsintyg)32 was issued containing accounts of Lars’s sexual excesses.33 The author of the document, whose identity becomes clear at the end, was Lars Finvidsson, a cleric in the diocese and an imperial notarius publicus. In the document he emphasized that he had been present when the accusations against Lars Vit were first brought forward and the testimonies given, and that he had at that time made thorough notes which formed the basis for the notarial instrument. The other persons present were the canon Lars Gädda, who led the meeting; the bishop; a number of representatives of the clergy of Skänninge; the chief magistrate of the same town; and ‘several city court judges from the town of Skänninge’. It is also mentioned that the document had been sealed with the seal of the town of Skänninge in the presence of Lars Finvidsson ‘as palpable proof ’ of the truth of what had been written down. From the document it is clear that the crimes that were dealt with concerned the accusations against Lars for his licentiousness (incontinentia vite) and the question of their truth. We are informed that action had been brought for this by the parishioners in Säby at a meeting which had taken place in the bishop’s house in Vadstena on 26 April 1410. The result was the judgement in Linköping on 29 April. Now, the testimonies were going to be given once more. What, then, was Lars guilty of according to these testimonies?34 32 Stockholm, Riksarkivet, Svenskt diplomatariums huvudkartotek, no. 17654 = Svenskt Diplomatarium, ed. by Silfverstolpe, ii (1875), no. 1426. The text is also printed in Bäärnhielm, ‘Bock i prästagård’, and there also translated into Swedish with short notes about the persons, place names, etc. found in the document. 33 Brilioth, Svensk kyrka, kungadöme och påvemakt, p. 243, was of the opinion that not all of the testimonies had been entered into the minutes, but he did not give any reasons for this assumption. Judging from the notarial instrument, only Lars’s sexual sins and crimes were the subject of attention on this occasion. As we have seen he had also been accused of other crimes of which we know nothing in greater detail, but these are not mentioned in the notarial instrument and we do not know the reason why. However, they may have been regarded as relevant from the point of view of what had happened at the curia during the spring of 1411. 34 To what extent the document correctly depicts what the witnesses and the interrogators said in all respects is, of course, impossible to determine. Their words are here and there given in direct speech, and therefore the text makes a lively and dramatic impression of being an official document from this time in history. 250 Bertil Nilsson Lars Vit’s First Sexual Transgression The comparatively exhaustive and detailed text treats two cases of immorality of which Lars was accused. They were said to have taken place while he was rector in Säby. Concerning the first case two midwives, Ingrid and Karin, were questioned. Both of them gave their testimony concerning the accusations against Lars separately and under oath. From that it became evident that Lars had had a woman in the rectory named Karin (not the midwife) and had had sexual intercourse with her before finally marrying her off with his servant Mårten. After a while Lars came to hate Mårten so much that the latter fled from his wife while she stayed in the rectory. There she became pregnant by Lars and therefore she was sent away by him from the rectory. In this way Lars hoped to avoid disgrace. She was received by a relative of hers, a certain Peter Källarson in the village of Ullevi in the parish of Järstad close to Skänninge, and she remained there until the time of delivery. However, Karin died in childbirth, the child being still-born — the baby was thought to have died a week earlier. Karin’s death was said to have taken place on the Sunday after Christmas 1409. The day before, 29 December, Karin had said that she was not going to take care of the child herself, and a little later she had explained that her husband was not the father of the child. She made an account of her background and revealed that Lars was the father. The midwives in their turn had told others this story and, thus, the matter became known not only in the village where Karin’s relative lived and where she had spent her last days but also in the surrounding area. Peter Källarson, a relative of the deceased Karin in whose house she had stayed, also gave testimony but claimed that he knew nothing more than what the midwives had told him. However, he said that Karin had arrived at his place on the last day of September 1409, bringing a letter of recommendation from Lars, in whose service she had been. Peter showed the letter which was written in Swedish and had Lars’s seal. The letter is quoted in the notarial instrument. There Lars asked that Karin would receive the help she needed on her journey to relatives in Östergötland to wait for her husband to return from a journey to Skåne. ‘You will be rewarded by the Lord for your good deeds’, Lars wrote among other things. A little later in the autumn he had also sent twelve öre pen­ ningar for Karin’s maintenance with a man from the vicinity of Säby to her relative in Ullevi. Peter Källarson also stated that Karin had earlier been a servant of his and that his wife was old and deaf, and therefore she had not been able to catch any word, although she was present in the house at the time of Karin’s death. Four more persons, all men, gave testimony concerning the deceased Karin. Two of them lived in Ullevi and had heard from four persons from the The Lars Vit Case 251 parish of Säby that Lars had come to terms with Karin’s husband Mårten after he had returned from Skåne. Lars had given him ‘several gifts’ but the witnesses made no further specification. The rector in Järstad also spoke and emphasized that the villagers in Ullevi were acquainted with the story and regarded it as true. Moreover, there was a rumour in the parishes all around that also said that it was true, which was confirmed on account of the town of Skänninge by the rector there, Jöns. If the content of the testimonies was true it was obvious to everybody that Lars had committed severe crimes not only in his capacity as a priest. As such he had neglected the demand for celibacy by living together with Karin. Moreover, he had treated her badly, partly by forcing her into marriage, partly by having sexual intercourse with her while her husband was away, and finally by having sent her away to conceal the fact that she was expecting his child. In juridical language he had committed ‘simple adultery’ (Swedish: enkelt hor), which occurred when an unmarried person had sexual intercourse with a married one. This crime was punishable according to the law of the realm. 35 Of course, this was the case irrespective of whether the man involved belonged to the clergy or not, but a priest had also made a promise, meaning that he was obliged to live in total sexual continence, among other things because he otherwise would jeopardize the cultic purity that was a condition for the celebration of Mass. One could also point to the rector’s superior position in relation to the woman and also in relation to her future and then lawful husband, who both were servants in the rectory. No detailed insight of the drama between these three persons is available and not all of the circumstances become clear, but probably Mårten was away for a longer time, since Karin was quite clear that Lars was the father of her child. At the same time the rector in this situation did not repudiate Karin totally since he sent with her an accompanying letter for her help and later even sent money to her. However, in the sealed letter Lars did not state that Karin was pregnant. He only said that she intended to spend her time with her relatives until her husband returned. Concerning the remaining testimonies, the importance of a good name (fama) should be noted. In a number of places in the notarial instrument it was emphasized that what had happened with Karin was known not only in the village of Ullevi, where Karin and her baby had died, but in the neighbouring parishes and in the town of Skänninge. Judging from the formulations — the fact was confirmed by highly placed persons — this general knowledge as well as 35 See further Hedberg, ‘Ægteskabsbrud, Sverige’. Bertil Nilsson 252 the rumour played a role in substantiating the repudiation of Lars’s behaviour. According to canon law a priest who lost his good name and became infamatus could thereby become irregular. The term infamia was of far-reaching importance in canon law and was connected to notorious criminality by the commentators to the Decretum Gratiani. Lateran IV, moreover, gave the subject its consideration.36 It was in the light of this that the bishop had been able to sentence Lars as publicus et notorius fornicator, since his sexual excesses also belonged to the so-called ‘notorious’ crimes (manifesta sive notoria delicta) in the canon law of procedure.37 The importance of publicity and good reputation becomes clear also in the next testimony given in Skänninge. Lars Vit’s Second Sexual Transgression Lars Vit’s second transgression concerned a woman named Ingegerd, who gave her testimony on the bishop’s summons. She also witnessed under oath, it was emphasized, but also under the threat of excommunication, since a letter of command (compulsoria) for her testimony had been issued by Fredericus de Deys, who, according to the notary instrument, was dean in Paderborn, papal chaplain and examining magistrate at the papal court of appeal, as well as a doctor of canon law. His letter does not survive, but it was he who was supposed to hear the case between Lars and Bishop Knut at the curia.38 Ingegerd had served as a housekeeper in Lars’s rectory and was asked if the rumours about him in Säby as well as in many other places in Östergötland were true, that is, that he had both sons and daughters with her. Ingegerd stated that out of her nine years at Lars’s place she had only been his concubine for four years, but while she still 36 About defectus famae, see Plöchl, Geschichte des Kirchenrechts, ii, 293–95; on the origin of the concept of infamia in canon law, see Landau, Die Entstehung des kanonischen Infamiebegriffs, pp. 39–41; see also Decrees of the Ecumenical Councils, ed. by Tanner, i: Nicaea I to Lateran V, conc. Lat. IV, c. 8 (p. 238), concerning clergymen: ‘Sed cum super excessibus suis quisquam fuerit infamatus ita, ut iam clamor ascendat, qui diutius sine scandalo dissimulari non possit vel sine periculo tolerari, absque dubitationis scrupulo ad inquirendum et puniendum eius excessus, non ex odii fomite, sed caritatis procedatur affectu’ (But when someone is so notorious for his offences that an outcry goes up which can no longer be ignored without scandal or be tolerated without danger, then without the slightest hesitation let action be taken to inquire into and punish his offences, not out of hate but rather out of charity). 37 About these crimes, see Plöchl, Geschichte des Kirchenrechts, ii, 359. 38 Concerning Fredericus de Deys, see Brilioth, Svensk kyrka, kungadöme och påvemakt, pp. 245–46. It can be noted that Brilioth without any explanation left out the content of the notarial instrument in his book and only mentioned its existence, p. 247. The Lars Vit Case 253 was in his service — that is, during the five first years — she had given birth to two children. She could not determine who their father was, since she had had another man, Mats Andersson, but still had had sex with Lars as often as he wanted (frequentabam lectum presbiteri quociens placuit). Then, of course, she was asked how it could be that she did not know who the children’s father was — ‘even whores usually know that’, the text runs. Furthermore her ignorance was extremely dangerous, since errors could occur concerning lineage, it was pointed out. This concern of the interrogators should be seen in the light of the fact that ambiguity could lead to uncertainties with regard to inheritance and many other things. Thus, the first part of Ingegerd’s interrogation already reflects both Lars’s and her own easy-going opinions of sexual relations, and, as we shall soon see, it was not the case that he raped her. As has been pointed out before, the priest must have been well aware of the fact that sexual continence was required of him, and since Ingegerd stated that she had another man, whom she mentioned by name, she knew that she was committing adultery with Lars, though as is evident from the document they were not married. Even if concubinage was not legally defined, either in the Swedish legislation or in the other Scandinavian countries, the customary position was that a couple in such a relationship should live only with one another, because the children had the right of inheritance, albeit a limited one.39 Since we have few source materials from Sweden it is difficult to say anything with certainty about the common view of premarital sex at the beginning of the fifteenth century. The church’s official standpoint, however, was quite clear but far from fully adopted in practice — one should marry before the priest and the contracting parties should publicly declare their mutual consent (normally in front of the church’s door). Only within the framework of marriage was mutual sexuality permissible.40 After the first dialogue between Ingegerd and those who questioned her, an animated discussion arose. To the question of paternity she answered, upset: ‘How should I know whose the child is, since I received one of the men and sent the other away, one in the morning and the other in the evening?’ Moreover she maintained that since she was unmarried she was allowed to have sex with whom she wanted to. She was then accused of having left Lars’s rectory when she was about to bear a child but then returned there and continued sexual relations with him. Besides, the leaders of the interrogation asserted that on one occasion 39 Auður Magnusdóttir, Frillor och fruar, pp. 18 and 20; Carlsson, ‘Slegfred, Sverige’. See Brundage, Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval Europe, for instance pp. 348–55 and 494–503; Korpiola, Between Betrothal and Bedding, pp. 145–51 with regard to Sweden. 40 Bertil Nilsson 254 she had given birth to a child in the rectory of Bishop Nils in Gränna, who was Lars’s brother and who had baptized the child ‘with distinguished godparents and a splendid barnsöl’ (i.e. solemn beer drinking on the occasion of the birth and baptism of a child). This was enough for the chief interrogators to consider Lars and no one else the father of the child. Another time she had given birth to a child in Starby in the parish of Vadstena. Also on this occasion it was asserted that she had had a lot of belongings and an expensive barnsöl. Therefore the interrogators wondered from where she had acquired all her belongings. She answered that Lars indeed had been angry with her every time she left to give birth to a child, but that after giving birth, she had regained his friendship. Thereafter it is said in the document that the interrogation continued and that the bishop spoke. He maintained that Ingegerd had mentioned publicly in his presence that Lars was the father of her children. She answered now under oath that this was true about the first child and that she could not know whether it was true of the second. Several unanswerable questions arise from this last part. Why was Lars angry with her when she went away to give birth? Was he not aware that she was pregnant until then? If he was, had he suggested an attempt at clandestine abortion? Did he want, as in the case of Karin who died in Järstad, to conceal his paternity by sending her away? Was he really the father? And when he took her back, where was the child, who according to canon law he was not allowed to keep in his house or publicly admit to having fathered?41 Moreover, we do not get to know in what connection the bishop had received Ingegerd’s public confession. However, from the judgement of 29 April 1410 it is clear that the bishop had visited the parish of Säby because of Lars’s transgressions, and thus he could of course have interrogated Ingegerd at that time. It remains unknown why the bishop and Ingegerd had different opinions about the paternity — the bishop, as we know, maintained that she had publicly said that Lars was the father of both children. Why did she change her mind now, if the bishop was right? Despite the fact that all these questions must be left without answers, it is interesting to note the mentality which Ingegerd expressed during the interrogation. It is stated that the questioners reproached her for her conduct with two men, saying to her: ‘Poor woman, why did you want to act like this? Tell us the truth!’ She answered: ‘I was an unmarried woman so why should I not be allowed to take any man I wanted?’ Her statement here probably reflects a common attitude. However, there is little source material which can throw further light upon this attitude. 41 For this last issue, see Nilsson, ‘A Fight against an Intractable Reality’, p. 603. The Lars Vit Case 255 At the provincial council in Uppsala in September 1368 this attitude had been dealt with. Among the statutes that were approved by the council was this: Everybody who maintained that ‘simple fornication’ (Swedish: enkel otukt), that is, sexual intercourse between two unmarried persons, was not a mortal sin should be condemned as traitor to the faith.42 The prescription was closely related to the next point, namely that according to the council there were those who asserted that hell did not exist and therefore one could sin without being punished. Such persons should be regarded as heretics and be excommunicated.43 Whilst the leaders of the church took up this standpoint concerning two unmarried persons, their opinion with regard to two married was, as has already been pointed out, of course clear. However, here it is after all a question of law and a question of sin respectively. From a purely juridical point of view, that is, according to Swedish legislation, it was not a punishable offence for two unmarried persons to have sex with each other when no child was begotten, and especially not for the woman, since she did not have criminal responsibility with regard to this type of moral ‘offence’. The sexual sin, by contrast, was the same for man and woman. Thus it can be concluded that the ecclesiastical aspect of these activities was not strongly emphasized in the Swedish legislation.44 Of course one can ask how common such a standpoint as Ingegerd’s was among people in general, without, however, receiving any answer. Much of what was decreed at provincial councils was repeated again and again throughout the centuries, and therefore it did not always have its background in conditions prevalent in the church province in question but rather reflected prescriptions to be enforced in the Western Church as a whole. In this case the council did not refer to any concrete examples, but it is said that the persons present, namely the bishops of the church province of Uppsala, had presented several cases concerning different types of misbehaviour (errores), which led to the council’s decisions and statutes. It therefore seems that the opinions mentioned 42 Stockholm, Riksarkivet, Svenskt diplomatariums huvudkartotek, no. 9344 = Diploma­ tarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, ix (1995). 2, no. 7777: ‘Quarto dampnamus et reprobamus omnes illos tamquam fidei catholice proditores qui dicunt simplicem fornicacionem non esse peccatum mortale’. 43 Stockholm, Riksarkivet, Svenskt diplomatariums huvudkartotek, no. 9344 = Diploma­ tarium Suecanum, ed. by Liljegren and others, ix (1995). 2, no. 7777: ‘Quinto dampnamus et reprobamus et excommunicatos esse denunciamus tamquam veros hereticos omnes asserentes infernum non esse, cum ex hoc concludere videantur vnicuique licitum et liberum esse sine pena peccare’. 44 See further Ekholst, För varje brottsling ett straff, pp. 208 and 216–17. Bertil Nilsson 256 about sexual intercourse and the non-existence of hell had spokesmen in the dioceses of the Swedish church province. The aforementioned council was held soon after 1350, but even by 1400, when Ingegerd made her statement in Skänninge, the church’s point of view had obviously not spread and found a firm hold among the people. If we keep to the official ecclesiastical regulations that were issued later on, and nothing else seems to be obtainable, the situation does not seem to have changed. The formulations from 1368 were repeated in a more precise version at, for instance, the provincial councils in Arboga in 1412 and 1474 respectively.45 Moreover, these positions were incorporated by Bishop Konrad Rogge of Strängnäs (1479–1501) in his order for visitations. At the visitation the bishop accordingly, among many other things within the moral sphere, should investigate if there was anyone in the parish who maintained the opinions concerning sex and hell described here.46 Despite some problems regarding how to evaluate the basis of this material in reality, taken together it allows us to draw the conclusion that Ingegerd’s attitude was not especially uncommon even though the church had made repeated attempts to condemn it. The Last Evidence of Lars Vit What happened, then, to the removed rector Lars Vit, his women, and the children? The only one of these whom we know anything about is Lars himself. The women are mentioned with their names only in the notarial instrument from the interrogations in Skänninge; they cannot be followed any further, and the same applies to the children. What legal consequences did Lars face after testimonies had been given to his disadvantage and the bishop’s benefit? We do not know, but it has been argued that the bishop ‘seems to have won the case’.47 Probably this was the result, despite the fact that Lars had managed to mobilize even royal power in his favour at the curia. However, there are no longer any records where his name occurs concerning this affair, but in all likelihood he was never again reinstated in his office either as canon or as rector of the parish of Säby. He had been sentenced to removal from his office, his benefice, and 45 Statuta synodalia veteris ecclesiae sveogothicae, ed. by Reuterdahl, pp. 108, 133, and 177–78; Inger, Das kirchliche Visitationsinstitut, p. 456 n. 1. 46 See Inger, Das kirchliche Visitationsinstitut, pp. 448–50 (especially p. 450). 47 Bäärnhielm, ‘Bock i prästagård’, p. 22. The Lars Vit Case 257 his canonry, but had not, however, lost his rights to exercise the ministry for all time, since he is found as a supplicant at the curia on 20 November 1417. At that time Lars Vit ‘priest (presbyter) in the diocese of Linköping’, applied for the office at All Saints Church in Skänninge which was vacant after Johan Karlsson’s death.48 The yearly income would not exceed four marks of silver, it is stated.49 We do not know if Lars was appointed to the position. Finally, in September 1435 his name appears in a certificate issued by the public notary Lars Finvidsson — the same person who wrote the notarial instrument from the interrogations in Skänninge. Here it is mentioned that Lars had given a testimony on the request of the monastery of Vadstena concerning tithes from the fishery in Motala ström (Motala stream). Lars is here called honorabilis vir, dominus Laurentius Hwiit, a title normally used for a priest at this time, but no more is said about his position. It is stated that forty years ago, that is, during the 1390s, Lars had been rector of the parish of Motala for more than eight years.50 This is about the time before he became rector in Säby and a canon as well. According to what we have seen before in the episcopal judgement also in Motala, he had had difficulties with the parishioners, although these difficulties had not been specified. With this reference back to Lars Vit’s first priestly office which is known to us, he disappears forever out of history, but his life has helped us to understand a bit of ecclesiastical jurisdiction, intrigues, and tensions between a bishop and a reigning queen and also something about the sexual mentality in Sweden at the beginning of the fifteenth century. Concluding Remarks As far as we can judge, when we look at the legal procedure where the bishop exercised his jurisdiction, the components in the Lars Vit case give the impression that canonical ideals were well known and followed in Sweden. However, 48 The name Vit is spelled incorrectly in the document as Lriit, which the copyist of the supplication already noted, but there is no reason to believe that the name should be anything other than Hwiit. 49 Stockholm, Riksarkivet, Karl Henrik Karlsson’s copies from the Vatican archives, 20 November 1417. Schück, Ecclesia Lincopensis, p. 447 asserted that Lars Vit was the ‘protégé of the monastery of Vadstena’. However the preserved records do not support this opinion. 50 Stockholm, Riksarkivet, no. 22437; Svenska medeltidsregester 1434–1441, ed. by Tunberg, no. 292. 258 Bertil Nilsson concerning the individual priest’s way of life and the exercise of his office, there were discrepancies between the regulations in canon law and reality. With regard to his neglecting the demand for celibacy, it is well known that he was not an exception either in Scandinavia or in the rest of Europe, even if he was a little more cunning than other priests in his handling of the situation when his mistresses or concubines became pregnant. Other priests in Scandinavia as well as in the rest of Europe lived in all likelihood in more solid concubinages, though this was probably not always the case. Nor does Lars’s accusation by parishioners of neglecting his office seem to have been unique. At the same time his case shows that with the help of influential persons, in this case among others the reigning queen, even a parish priest from Sweden could reach the pope personally with his concerns. The curia, in other words, was used for matters of an individual character, not only for those with immediate general interest. However, it must be deemed very unusual that the pope really had knowledge of a specific parish priest’s life in the Swedish church province and was informed about it both by the rector himself and by the other party, that is, Bishop Knut Bosson of Linköping. The surviving sources reveal not only the juridical conditions but also, to some extent, sexual morality itself. How much of what we have heard about was representative for Swedish conditions in general is difficult to say, but the opinions seem not to have been unusual in the kingdom. However, more source material is needed to say anything further about this matter. The Lars Vit Case 259 Works Cited Manuscripts and Archival Documents Uppsala, Uppsala Universitetsbibliotek, Codex Upsaliensis C 6 Primary Sources Corpus iuris canonici, ed. by Emil Friedberg and Aemilius Ludwig Richter, 2 vols (Graz: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, 1959) Decrees of the Ecumenical Councils, ed. by Norman P. Tanner, 2 vols (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 1990) Diplomatarium Norvegicum, ed. by Christian C. A. Lange and others, 22 vols (Oslo: Malling, 1849–1995) Diplomatarium Suecanum, ed. by Johan Gustaf Liljegren and others, 11 vols (Stockholm: Norstedt, 1829–2011) Finlands medeltidsurkunder, ed. by Reinh Hausen, 7 vols (Helsingfors: Kejserliga Senatens Tryckeri, 1910–35) Magnus Erikssons landslag i nusvensk tolkning, ed. by Åke Holmbäck and Elias Wessén (Stockholm: Nordiska, 1962) Statuta synodalia veteris ecclesiae sveogothicae, ed. by Henrik Reuterdahl (Lund: Berling, 1841) Svenska medeltidsregester, 1434–1441, ed. by Sven Tunberg (Stockholm: Norstedt, 1937) Svenskt Diplomatarium från och med år 1401, ed. by Carl Silfverstolpe, 3 vols (Stockholm: Norstedt, 1875–1902) Secondary Studies Auður Magnusdóttir, Frillor och fruar: politik och samlevnad på Island, 1120–1400 (Göte­ borg: Historiska institutionen, Göteborgs universitet, 2001) Bäärnhielm, Göran, ‘Bock i prästagård’, in Röster från svensk medeltid: Latinska texter i original och översättning (Stockholm: Natur och Kultur, 1990), pp. 22–35 Brilioth, Yngve, Svensk kyrka, kungadöme och påvemakt, 1363–1414 (Uppsala: Lundequitska Bokhandeln, 1925) Brundage, James A., Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval Europe (Chicago: Uni­ versity of Chicago Press, 1987) Carlsson, Lizzie, ‘Slegfred, Sverige’, in Kulturhistoriskt lexikon för nordisk medeltid, ed. by John Danstrup and others, 22 vols (Malmö: Allhems, 1956–78), xvi: Skudehandel– Stadsskatter (1971), cols 195–97 Ekholst, Christine, För varje brottsling ett straff: Föreställningar om kön i de svenska medel­ tids­lagarna (Stockholm: Historiska institutionen, Stockholms universitet, 2009) 260 Bertil Nilsson Gunnes, Erik, ‘Prester og deier — sølibatet i norsk middelalder’, in Hamarspor: eit festskrift til Lars Hamre 1912 – 23. januar – 1982, ed. by Steinar Imsen and Gudmund Sandvik (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1982), pp. 20–44 Hasselberg, Gösta, ‘Böter, Sverige’, in Kulturhistoriskt lexikon för nordisk medeltid, ed. by John Danstrup and others, 22 vols (Malmö: Allhems, 1956–78), ii: Blik–Data (1957), cols 519–25 Hedberg, Gunnel, ‘Ægteskabsbrud, Sverige’, in Kulturhistoriskt lexikon för nordisk medel­ tid, ed. by John Danstrup and others, 22 vols (Malmö: Allhems, 1956–78), xx: Vidjer– Øre (1976), cols 503–07 Inger, Göran, Das kirchliche Visitationsinstitut im mittelalterlichen Schweden (Lund: Gleerups, 1961) —— , ‘Skänninge möte 1248 ur rättshistorisk synpunkt’, Kungliga Humanistiska VetenskapsSamfundet i Uppsala: Årsbok (1998), 177–95 Korpiola, Mia, Between Betrothal and Bedding: The Making of Marriage in Sweden, 1200–1600 (Leiden: Brill, 2009) Landau, Peter, Die Entstehung des kanonischen Infamiebegriffs von Gratian bis zur Glossa ordinaria (Köln: Böhlau, 1966) Mornet, Élisabeth, ‘Le Crime du chanoine: observations sur une procédure criminelle en Suède au début du xve siècle’, in Un Moyen âge pour aujourd’hui: mélanges offerts à Claude Gauvard, ed. by Julie Claustre, Olivier Mattéoni, and Nicolas Offenstadt (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2010), pp. 478–86 Nielsen, Torben K., Cølibat og kirketugt: studier i forholdet mellem Innocens III og Anders Sunesen, 1198–1220 (Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 1993) Nilsson, Bertil, ‘A Fight against an Intractable Reality: The Efforts at Implementing Celibacy among the Swedish Clergy During the Middle Ages’, in Sacri canones ser­ vandi sunt: Ius canonicum et status ecclesiae saeculis xiii–xv, ed. by Pavel Krafl (Praha: Historický ústav AV ČR, 2008), pp. 596–617 —— , ‘Förbjudna kvinnor och barn i medeltida prästgårdar: Celibatskrav och motstånd i Sverige’, Saga och sed: Kungl. Gustav Adolfs akademiens årsbok (2008), 41–70 Plöchl, Willibald M., Geschichte des Kirchenrechts, 2nd edn, 6 vols (Wien: Herold, 1959–68) Salonen, Kirsi, ‘Introduction’, in Auctoritate Papae: The Church Province of Uppsala and the Apostolic Penitentiary, 1410–1526, ed. by Sara Risberg and Kirsi Salonen, Diplo­ matarium Suecanum, Appendix: Acta Pontificum Suecica, 2 (Stockholm: Riksarkivet, 2008), pp. 7–144 —— , The Penitentiary as a Well of Grace in the Late Middle Ages: The Example of the Province of Uppsala, 1448–1527, Annales Academiae Scientiarum Fennicae, Hum­an­ iora, 313 (Saarijärvi: Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 2001) Schmugge, Ludwig, Kirche, Kinder, Karrieren: Päpstliche Dispense von der unehelichen Geburt im Spätmittelalter (Zürich: Artemis & Winkler, 1995) Schück, Herman, Ecclesia Lincopensis: Studier om Linköpingskyrkan under medeltiden och Gustav Vasa (Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1959) Concluding Remarks Patrick Geary T he editors and contributors to this volume confront two seemingly diametrically opposed images of the relationship between Medieval Scandinavia and the rest of Western Christendom. The first is the ‘marginal’ view of Scandinavia, a perspective expressed by Peter the Venerable in his description of King Sigurd placed by the Lord in extremis finibus orbis.1 From the perspective of Cluny or indeed from Rome, the ultimate borders might be conceived of being at the ends of the earth, as in the case of Scandinavia or Ireland, or they might be understood in terms of the borders of Christendom or at least Latin Christendom, as in the cases of Poland or Hungary. In either case, this vision reassured those who claimed to live in the centre of their authority and superiority vis-à-vis the other. Such marginalization was not only a distancing tactic of those who considered themselves to write from the ‘centre’, but it could also be a useful self-designation of Scandinavians or for example Hungarians, who could appeal for special consideration and a special status because of their situation on the precarious edge of Christendom.2 Modern scholarship has largely accepted and even embraced these images of marginalization. The history of Europe in the Middle Ages relies on paradigms of social, cultural, and political organization largely based on the cases of France, Germany, and England. Thus just as continental traditions of lordship and king1 Peter the Venerable, The Letters, ed. by Constable, p. 141. On Hungary as the Gate of Christendom see Berend, At the Gate of Christendom, esp. pp. 163–71. 2 Patrick Geary (geary@ias.edu) is Distinguished Professor Emeritus of History at the Univer­ sity of California, Los Angeles. Medieval Christianity in the North: New Studies, ed. by Kirsi Salonen, Kurt Villads Jensen, and Torstein Jørgensen, AS 1 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013) pp. 261–268 BREPOLS PUBLISHERS 10.1484/M.AS-EB.1.100819 Patrick Geary 262 ship, social organization and agrarian economy, warfare, and commerce, are often treated as normative and those of Scandinavia and eastern Europe as variants, the elaboration of religious practice, canon law, parish structures, and saints’ cults as experienced in Continental Europe are taken as normative and phenomena elsewhere as deviant. And just as in the twelfth century, many in these putative ‘marginal’ regions today embrace this status, emphasizing their isolation and their uniqueness, not as a sign of underdevelopment but rather as a source of pride and differentiation. Norway and Iceland are famously and proudly not members of the European Community; Denmark and Sweden are, but they have not yet joined the Eurozone. These countries claim not only a unique position in the Europe of the present but, as the editors note, a ‘special Scandinavian past’, one identified most strongly with the Viking Age, an heroic pagan world that fades only gradually into particularistic national histories of Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. Even then, scholars tend to eagerly seek evidence of the survival of unique Norse religion and culture through the Middle Ages and beyond. This traditional view of centre and periphery is complicated by a second scholarly tradition pointed out by the editors in their introduction: namely the expansion of the centre, taken to be the Carolingian model of society, government, and religion, into the peripheries, be they Scandinavian, Celtic, Slavic, or Iberian. The result, according to the logic of this argument, is the creation of ‘Europe’, defined not by geography but by homogeneous religious, political, and cultural traditions. As they rightly point out, Robert Bartlett’s The Making of Europe forcefully argues this image of cultural transfer, but this and other accounts of Europe’s genesis take a resolutely hegemonic perspective: European culture is the culture of the colonizer; there is no consideration of what the colonized, be they Celts, Slavs, or Scandinavians, might have contributed either to European culture in general or even to the particular forms of European culture in different areas of Europe.3 Such an approach understandably disturbs those who are uncomfortable with the vision of a monolithic Europe, directed from the centre (understood today as Brussels rather than Rome or Cluny) and adds to the ambivalence of many people concerning the existence of a European identity and a common culture. Is indeed Scandinavia a part of Europe? The authors of this volume grapple with the challenges of this dilemma within the sphere of religion. Wisely they do not ask whether Scandinavia is part of a common culture, but, as the title of the volume suggests, they ask how Scandinavians negotiated variation within an admittedly common culture. Was the religious life of Nordic people different from that of southern Christians? 3 Bartlett, The Making of Europe. Concluding Remarks 263 If so, to what are these differences to be attributed — distance from the centre, late or incomplete Christianization, or creative response to imported tradition? And finally, what were the dynamics uniting the production of difference and of homogenization? Did the periphery perhaps change the centre, even as the centre changed the periphery? The results largely confirm Kurt Villads Jensen’s perception that transfer is always a negotiation between sender and receiver; Christianity as practised in Scandinavia was no exception. On the one hand one sees little that is truly exceptional or unique in the religious, cultural, and legal practices explored in these essays. Paganism appears to have left no more of a mark on the region than it did elsewhere in Europe within a similar timeline following conversion. Lars Bisgaard and Stefan Brink find, for example, that the myriad uses of beer, whether at communal celebrations of lay and clerical guilds, or the ‘soul’s beer’ of the Old Gulathing Law, fall well into the pattern of European religious and communal celebrations. Perhaps some of these practices may have some distant pre-Christian origins, but then so too in all likelihood both the minne drinking of Continental tradition and indeed the ancient Mediterranean tradition of funerary meals and libations.4 The uses of beer certainly conform to those of wine in southern regions, while the lack of the latter in Scandinavia explains the expanded use of the former in the North, and the desire to expand it even further on the part of some clerics. Likewise the ‘spirits of the land’ examined by Else Mundal resonate with similar, widespread traditions across Europe. As she suggests, Christianity may have left a ‘gap’ filled by fylg jur and norns, beings that did not quite fit into a Christian cosmos. Exactly the same phenomenon has been richly explored for France and Angevin England by Jean-Claude Schmitt, who recognized in the tales of Walter Map the attempts to fit the myriad being of pre- and extraChristian folk tradition into a Christian cosmology.5 Map’s accounts of visits to other worlds as well as sightings of otherworldly beings in this world demonstrate the ambivalence of Christian commentators confronted with widespread belief in beings and places that, like fylg jur and norns in the North, had no obvious place in the Christian cosmos of heaven, earth, and hell. All of these processes are, as Torben Kjersgaard Nielsen expresses it, a complex process of the sacralization of religious landscape when introducing Christianity to the Baltic, and the de-sacralization of pagan religious and social landscape. 4 5 See Oexle, ‘Die Gegenwart der Toten’, esp. pp. 48–57. Schmitt, ‘Temps, folklore et politique au xiie siècle’. 264 Patrick Geary These twin processes had characterized the introduction of Christianity to the Mediterranean and Britain long before, with similar results. The deep integration of Scandinavia into the religious and social landscape of Christendom is nowhere more in evidence than in the ideology of Crusade, a theme woven through many of these essays. Sigurd Jorsalfar, the first European king to personally participate in a Crusade, could be considered an ‘early adapter’ of Crusade ideology and practice, having experience not only in Jerusalem and the Levant but significantly in Portugal as well, experience and renown that he brought home and set to use against Småland. The close parallels with Iberian rulers such as Pedro I of Aragón, Alfonso VII of León and Castile, or Alfonso I of Portugal demonstrate conclusively that rulers at both ends of Europe were following the same religious and ideological programme, and all were seemingly aware of how their wars against the infidels to the north or south could aid their negotiations with the centre as well as their positions at home. Indeed, the age of crusading positively enhanced the significance of both Scandinavia and the Iberian Peninsula because it was precisely on these margins that crusading was practised: the margins of the Christian world, both north-east and south-west, were where crusades, which were but an ideology in the old centres of Europe, became reality. Here indeed the margins became the true centre. Perhaps the clearest image of the deep integration of Scandinavia into the wider world of Latin Christendom emerges from the examination of legal cases. Although the level of fine-grained detail of the Lars Vit case examined by Bertil Nilsson is a rarity in most of Europe, both the offences of this lecherous cleric and the more schematically presented evidence studied by Kirsi Salonen concerning supplicants to the Holy See for the regularization of their marriages conforms generally to the norms of European-wide sexual regulation. While Scandinavia lacks the detailed episcopal visitation records available for parts of southern Europe, one finds similar concerns about the clerical concubinage across Europe, concerns that seem to come to the fore less simply because of the widespread practice of clerical marriage itself than when the sexual activities of clergy created public scandal or resulted in community hostility. One can infer from Lars’s case, as from similar cases elsewhere, that it was the common complaint that Lars’s behaviour interfered with his office rather than his sexual mores per se that brought him before ecclesiastical courts. Otherwise in southern Europe it appears that the penalty for concubinage, a relatively small fine imposed on married priests at the time of episcopal visitations, might well be seen as simply another source of episcopal revenue. Similarly, the cases of clerical violence Torstein Jørgensen analyses from the Apostolic Penitentiary Concluding Remarks 265 demonstrate not only the violent potential of clergy — certainly an international phenomenon — but perhaps more significantly the expertise of the petitioners in drafting a narrative of the killings in terms precisely calculated to have the best chance of obtaining the desired pardons. One thinks immediately of Natalie Zemon Davis’s Fiction in the Archives, which explores, for a slightly later period, the petitions for pardon drafted by supplicants hoping to escape execution by telling the kind of story that might bring a royal pardon.6 And what is true of cases of clerical violence, concubinage, and lay incest seems to be true as well of Norwegian legislation concerning licit and illicit animals: in their very clever confrontation of ecclesiastical prohibitions and archaeological evidence, Sæbjørg Walaker Nordeide and Jennifer R. McDonald find that statically Norwegian dietary practice was largely in conformity with canon law. And yet, in the same sentence in which Nordeide and McDonald conclude that Norwegian practice conformed to canon law, they add the significant phrase, ‘but was also a response to local conditions’ [insert cross-reference here], and this caveat might be seen as the hallmark of all of these essays. Scandinavian Christianity was indeed fully integrated into Latin Christendom, but here as everywhere it also responded to local conditions, conditions of ecology, of traditions, of sociology and, inevitably, of distance from other parts of Christendom. To return to the first issue discussed above, the lingering heritage of paganism, pre-Christian Scandinavian culture may have been no more alive than in Germany, Ireland, or even Mediterranean Europe, but its presence was certainly not negligible. Landvættir, fylg jur, and norns had their own personalities and identities; they weren’t just another version of ‘Herlechin’s troop’, English fairies, or Italian Strege. Certainly, too, drinking rituals were part of communal celebrations and the commemoration of the dead from North Africa to the Arctic Circle, and such rituals were incorporated as normal policy into Christian practice. But in the North, the significance of beer relative to wine was undoubtedly greater and enjoyed an ancient pedigree. Here tradition and ecology combine to reinforce ancient traditions under new circumstances. Of necessity, wine was an extremely expensive import commodity. The reality of Scandinavian climate made it impossible to cultivate an adequate supply of wine for the Eucharist, and if priests attempted to use more wine than water in the Mass, the ground may have been practical rather than cultic. However the use in guild statutes of the traditional word gerd, more frequently than minne, which after all was 6 Davis, Fiction in the Archives. Patrick Geary 266 possibly imported along with the guild system itself from Germany, suggests that the tradition of ritual drink to commemorate the dead (and in Iceland to celebrate the marriage of the living) was at once a thoroughly regional tradition and yet integrated into a pan-European tradition. If both local traditions and local ecology combined to root certain forms of drink deeply in Scandinavian culture, geographical realities certainly inflected the nature of the involvement of Scandinavia in Christendom-wide phenomena, such as the spread of the parish system, cult of saints, or the appellate procedures of ecclesiastical courts. The parish system took longer to become normative both north and south of the Alps than an earlier generation of scholars assumed, and the spread of the system was probably not complete in Continental Europe before the twelfth century. Here Scandinavia is not so much lagging as roughly contemporaneous with many regions to the south. Some, like André Vauchez, have on the other hand argued for a certain retard in the development of the cult of saints in northern Europe in the later Middle Ages. His study of canonization processes suggested to him a kind of northern model of sanctity, still closely associated with high status individual or the victims of a violent and unexplained death at a time when southern Europe, especially Italy, saw the flourishing of new cults of saints, whose sanctity was tied to their lowly status and their interior spirituality. 7 This may be so, and certainly the cult of Birgitta of Sweden, perhaps the most important Scandinavian ‘export’ to the rest of Christendom, ably examined by Claes Gejrot, does not contradict this image. Birgitta after all belonged to the highest levels of society. But in the case of canonization processes, as in the cases of individuals appealing to the papal curia or the Apostolic Penitentiary which Kirsi Salonen points out to be of a higher social class than appeals from the Continent, one must simply consider the enormous distances and expenses involved. Even if in theory the costs of the dispensations themselves might be reduced or waived entirely, the complexities of transmitting such a supplication over so great a distance would surely have been an insurmountable barrier to most simple Scandinavian farmers or townsfolk. And the cost of a successful canonization process was and remains enormous. Even the support of the Swedish bishops would probably not have sufficed had it not been for the support received from the queen of Naples and the Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV. But of course for Birgitta, as indeed for the crusading King Sigurd, it was not necessary for her renown to travel to the extreme ends of the earth: she made the trip herself, 7 Vauchez, La Sainteté en Occident. Concluding Remarks 267 in the flesh, and made Rome her own before her death. For others, the simple reality of distance required other accommodations and that acknowledged and incorporated local realities. Finally, these essays allow us to consider not only the ways in which Scandinavia received and negotiated Christianity but how the region in turn exported particular forms of the Christian tradition. Birgitta was certainly the most visible example of a Scandinavian who became a Europe-wide inspiration. But Stefan Brink’s reflections on the origin of the parish system also complicate common assumptions about direction of cultural influence. A version of the ‘Minster hypothesis’ may explain the development of Scandinavian parish, but perhaps without the ‘minster’ itself. One need not posit direct influence from England to envision early large (royal?) estates and farms, serving ‘mother churches’. Moreover the origin of Anglo Saxon soke may well demonstrate the complexity of exchange between England and southern Scandinavia: if soke began as a Scandinavian term that became a loan-word in Anglo Saxon and acquired the meaning of parish in the tenth century, only to be re-exported to Scandinavia by Anglo-Saxon clergy, then one can begin to understand how very complex and multidirectional the complexities of Nordic variations of Latin Christianity may have been. In conclusion, these essays go a long way towards resolving the dilemma of Scandinavian conformity and difference as developed across generations of scholarship. The Nordic world was as Christian as any other region of the Latin West; it shared the same beliefs, the same ecclesiastical structures, the same aspirations, devotional traditions, and moral expectations. But in every case these were subtly integrated into the realities of a unique climate, geographical position, and long and complex prehistory, realities that made every region of Europe equally particular, whether self-proclaimed centre or self-proclaimed periphery. 268 Patrick Geary Works Cited Primary Sources Peter the Venerable, The Letters of Peter the Venerable, ed. by Giles Constable (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967) Secondary Studies Berend, Nora, At the Gate of Christendom: Jews, Muslims and ‘Pagans’ in Medieval Hungary, c. 1000–c. 1300 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001) Bartlett, Robert, The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization, and Cultural Change, 950–1350 (London: Lane, 1993) Oexle, Otto Gerhard, ‘Die Gegenwart der Toten’, in Death in the Middle Ages, ed. by Herman Braet and Werner Verbeke (Leuven: Universitaire Pers Leuven, 1983), pp. 19–77 Schmitt, Jean-Claude, ‘Temps, folklore et politique au xiie siècle: A propos de deux récits de Walter Map (‘De Nugis Curialium’, I, 9 et VI, 13)’, in Le Temps chrétien de la fin de l’Antiquité au Moyen Âge (iiie-xiiie siècles): Colloques internationaux du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (Paris 9–12 mars 1981) (Paris: Editions du Centre national de la recherche scientifique, 1984), pp. 489–515 Davis, Natalie Zemon, Fiction in the Archives: Pardon Tales and Their Tellers in SixteenthCentury France (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1987) Vauchez, André, La Sainteté en Occident aux derniers siècles du Moyen Âge: d’après les procès de canonisation et les documents hagiographiques (Roma: Ecole française de Rome, 1981) Index of Persons Aage Brahe: 197–98 Adam of Bremen: 90, 97–98 Adrian IV, pope: 27 Åke Hansson (Tott): 197, 200–01 Albert of Buxhövden, bishop of Riga: 97, 129 Albrekt of Mecklenburg, king of Sweden: 155, 158, 172, 176 Alexander III, pope: 70, 182 Alexander V, pope: 247 Alexander VI, pope: 194, 235 Alfonso I, king of Portugal: 264 Alfonso VII, king of León and Castile: 264 Alhein Volteirs: 197 Alissa Henriksdotter (Horn): 197–98 Amund Håkonsson: 214–16, 223–25, 227, 233–34 Anders Sunesen, archbishop of Lund: 2, 91, 121–22, 149, 239 Andreas von Stierland: 140 Angelus Gherardini: 194 Anna Jakobsdotter (Sparre): 197 Anne Mouridsdatter (Gyldenstierne): 199–200 Anselm of Canterbury: 90, 111 Antonio Mast: 195 Anz, Christoph: 85 Arbusow, Leonid: 122 Archangelo Arcimboldus: 195 Ari inn fróði: 12 Arne in Brunkeberg: 213, 222, 232 Arnold of Lübeck: 113 Arvid Jacobsson (Garp): 199 Arvid Lille: 199 Asbjørg Toresdaughter: 214, 232 Asmund Rolvsson: 213–14, 222, 224, 232 Asser, archbishop of Lund: 90, 96, 113 Assmann, Jan: 148 Baetke, Walter: 9, 11 Baldr: 9, 10 Barbara Olofsdotter: 197, 199 Barth, Fredrik: 124 Bartholomeus de Camerino: 194 Bartlett, Robert: 92, 262 Beate Jensdatter (Ulfstand): 197–98 Belial: 147 Bender, Barbara: 125–26 Bengt Filipsson (Ulv): 161 Bernard, archbishop of Naples: 174, 176–77 Bernard of Clairvaux: 102–04 Bertold, bishop in Livonia: 98, 138, 145 Birger Gregersson, archbishop of Uppsala: 162–65, 172–74, 176 Birger Ulfsson: 158, 161, 171–72, 176 Birgitta Birgersdotter see St Birgitta of Sweden Birkeli, Fridtjof: 25 Bjǫrn hítdœlakappi: 18 Blair, John: 31 Blanka, queen of Sweden: 156 Bo Jonsson (Grip): 159–60, 171, 176 Bolton, Brenda: 122 Boniface IX, pope: 156 Bourdieu, Pierre: 136 Bragi: 11 Brink, Stefan: 32, 131, 145, 148 Bugge, Alexander: 34 Bugge, Sophus: 9, 11, 111 270 Burchard of Worms: 44 Burke, Peter: 136 Canute VI, king of Denmark: 70 Catherine, daughter of Niels Eriksen Gyldenstierne: 200 Caupo: 129, 145 Cecilia Ulfsdotter: 161 Charlemagne: 67, 104 Charles IV, emperor: 155, 170–71, 176–77, 266 Christ: 9–10, 19, 70, 73, 89, 91, 93–94, 96–97, 102, 108, 111, 134–35, 137, 147, 166–67, 169 Christian, bishop of Magdeburg: 98 Christian I, Union king: 220–21 Clement VII, pope: 194 Cnut the Great, king of England: 36 Connerton, Paul: 148 Daniel, Priest: 144 Dobrel: 142 Eirik Raude: 53 Elisabeth, daughter of King Hans of Denmark: 196 Erengisle Sunesson: 171 Eric Ejegod: 69 Erik Bille: 197 Erik Eriksen (Banner): 199–200 Erik Gunnes: 238–39 Erik Trolle: 197–99 Esbern Snare: 108 Eskil Djäkne: 245–46 Fonnesberg-Schmidt, Iben: 122 Fortuna: 17 Franciscus Brevius: 216, 235 Fredericus de Deys: 252 Freya: 52 Geertz, Clifford: 121, 123–25, 127, 138 Gertrud Petersdotter: 201 Giovanna, queen of Naples: 155, 169–70, 176–77, 266 Gísli: 15, 16 Gomez, count of Nola (Garcias de Albornoz): 175 Gratian: 100–01, 243 INDEX OF PERSONS Gregory III, pope: 43 Gregory VII, pope: 27 Gregory IX, pope: 28, 70–71, 169 Gregory XI, pope: 165, 170–71, 176 Gregory XII, pope: 247 Grundberg, Leif: 28–29 Gudmar Fredriksson: 174 Guibert of Nogent: 90 Guillaume d’Aigrefeuille: 175–76 Gunna Geirulvsdaughter: 214, 232 Gunnhild Petersdotter: 201 Guntherus de Bunow: 194 Guttorm Thorlaugsson: 213–14, 222–27, 229, 232–33 Guy de Malesset: 175–76 Håkon VI Magnusson, king of Norway: 222, 232 Hallfrøðr vandráðaskáld: 16 Hans, king of Denmark: 196 Harald Bluetooth, king of Denmark: 67, 93 Harald Klak, king of Denmark: 67 Hebbus: 143 Heide, Eldar: 19 Heimdallr: 9, 11 Helena Israelsdotter: 161 Helmold of Bosau: 97 Henry of Livonia: 97, 129–30, 134–40, 142–47 Heriveus: 114–15 Hermannus Tuleman: 194 Honorius III, pope: 70, 122 Howe, John M.: 132 Inge, king of Sweden: 27 Ingeborg Åkesdotter (Tott): 197 Ingeborg Filipsdotter (Tott): 197–98 Ingegerd: 252–56 Ingesman, Per: 194–95 Ingrid, midwife: 250 Innocent III, pope: 71, 97, 121–22, 125, 129, 146, 149, 182 Isidore of Seville: 108 Jens Pedersen: 197 Jesus see Christ Joachim, margrave of Brandenburg: 196 Jöns, rector in Skänninge: 251 Jösse Eriksson, bailiff: 160 Johan Karlsson: 257 INDEX OF PERSONS Johan Peterson: 158 Johan Präst: 174 Johanne Henriksdatter (Ulfstand): 197–98 Johannes, bishop of Tallinn: 194 Johannes Antonius: 194 John IX, pope: 94, 114–15 John XXII, pope: 247 John of Spain ( Johannes de Hispania): 175 John of Vechta: 145 John Paul II, pope: 156 Jolliffe, J. E. A.: 35 Jon Raude, archbishop of Nidaros: 48–49, 217–19 Julianus, bishop of Bertinoro: 216, 235 Julius II, pope: 194 Karin: 250–51, 254 Karin, midwife: 250 Karl Ulfsson (Sparre af Tofta): 161, 171 Katarina Eriksdotter (Bielke): 197, 199–201 Katarina Nilsdotter (Sparre): 197 Katarina Ulfsdotter: 157–60, 164, 170, 174–76 Keld, provost in Viborg: 98 Kettilmund: 174 Klaniczay, Gábor: 169 Klaus Henriksson (Horn): 198 Knut Bosson, bishop of Linköping: 240–42, 244–45, 247–49, 252, 258 Kolsrud, Oluf: 212 Konrad: 163 Konrad Rogge, bishop of Strängnäs: 256 Koshar, Rudy: 148 Kristina Kristiandotter (Frille): 198 Kristina Petersdotter: 201 Kyrian: 143, 145 Lars Finvidsson: 249, 257 Lars Sunesson Vit: 237–58 Latino Orsini: 175–76 Laurentius Hwiit see Lars Sunesson Vit Layan: 143, 145 Lehtonen, Tuomas M. S.: 17 Leo X, pope: 194 Liv Gunnarsdaughter: 214, 232 Lucia Petersdotter: 201 Mägi, Marika: 133 Märta Ulfsdotter: 151 271 Magerøy, Ellen Marie: 73, 82 Magnus Eriksson, king of Sweden: 156, 172, 219, 243 Magnus Nilsson: 197–98 Magnus the Law-Mender, king of Norway: 48, 217–18 Margareta, queen of the Kalmar Union: 173, 240, 247–48 Margarethe, daughter of Niels Eriksen: 200 Marinus de Fregeno: 194 Mårten: 250–51 Mats Andersson: 253 Mattias Larsson, bishop of Västerås: 165 Meinhard, bishop of Riga: 139, 145 Mortensen, Lars Boje: 95 Muhammad: 98 Nerid Hallsteinsson: 214, 232 Nicholas Breakspear: 27 Nicodemus: 93 Nicolas Orsini, count of Nola: 176 Niels: 106 Niels Eriksen (Gyldenstierne): 200 Nielsen, Torben K.: 239 Nils in Gränna: 254 Nils Hermansson, bishop of Linköping: 158, 162, 165, 167–69, 176–77, 242 Nørlund, Poul: 110 Odin: 9–10, 18, 82, 111–12 Oexle, Otto Gerhard: 85 Óláfr Tryggvason, king of Norway: 16 Olav, king of Norway see St Olav Olav Engelbrektsson, archbishop of Nidaros: 56 Olav Koch: 214–16, 223–25, 233–34 Olrik, Jørgen: 72–73 Oluf Stigsen (Krognos): 199–200 Ostinelli, Paolo: 195 Pål Bårdsson: 219 Pascal II, pope: 100 Peder Lille: 197, 199 Pedro I, king of Aragón: 264 Peter Holmstensson: 247–48 Peter Källarson: 250 Peter Olofsson: 157–60, 162, 164, 173, 176 Peter Ribbing: 161 Peter the Venerable of Cluny: 90, 101, 261 272 Peter Toresson (Bielke): 197 Philippus Calandrini, cardinal: 192 Predbjørn Podebusk: 199–200 Ragvald of Linköping: 173 Raymundus Peraudi: 195 Redigost: 98 Regino of Prüm: 44 Rolv: 213–14, 222–24, 227, 232 Rubin, Miri: 85 Saladin: 108 Samson: 230 Sandmark, Alexandra: 48 Sandnes, Jørn: 32 Santiago see St James Sauer, Carl: 126 Saviour see Christ Sawyer, Peter: 35 Saxo Grammaticus: 69, 97 Schjødt, Jens Peter: 111 Schmitt, Jean-Claude: 263 Schuchard, Christiane: 194 Schück, Henrik: 167 Seierstad, Andreas: 82 Sigurd Eindridesson, archbishop of Nidaros: 70 Sigurd Jorsalfar, king of Norway: 68, 69, 90, 96, 101–02, 261, 264, 266 Simon, bishop of Tallinn: 194 Skre, Dagfinn: 30, 32 Snorri Sturluson: 10–12, 16, 101, 110, 112 St Anskar: 25, 67 St Augustine: 101, 133 St Birgitta of Sweden: 2, 155–57, 160, 162–63, 165–77, 266–67 St Boniface: 43, 46 St Canute: 75 St Catharine of Siena: 176 St Columbanus: 71–72, 83 St George: 108 St James: 106, 108 St Jerome: 168 St Mary: 10, 17, 73, 134, 137 St Nicholas: 106 St Olav: 68, 96, 106 St Paul: 172 St Thomas of Aquinas: 176 St Vitus: 130 INDEX OF PERSONS Sten Bengtsson: 171 Sten Henrikssen (Renhufvud): 197 Sten Store: 197 Stenton, Frank: 35 Svantevit: 130 Svein in Aker: 213, 232 Svend Estridsen, king of Denmark: 99 Tamburini, Filippo: 195 Tamm, Marek: 148 Tharapita: 130, 135, 145 Theoderich: 144 Theodore of Canterbury: 43–44, 46 Þiðrandi: 15 Thomas Johansson (Malstaätten), bishop of Växjö: 158, 164 Thore Rolvsson: 213–14, 222, 224–25, 232 Thorgeir the Law-Speaker: 95 Þórir: 16 Tönne Eriksson (Tott): 200–01 Tolkien, J. R. R.: 95 Tor: 9, 30 Torbjørn Lieslevolve: 53 Trond Reidarsson: 213, 232 Ulfr Uggason: 10 Urban VI, pope: 165, 171 Urbanczyk, Przemyslav: 130–31 Valdemar I, king of Denmark: 70 Valdemar II, king of Denmark: 70, 106 Valk, Heiki: 132–33 Vauchez, André: 266 Vigleik at Håtveit: 213, 232 Volhard of Harptstedt: 145 Volkwin: 146 Wallerstein, Immanuel: 125 Walter Map: 263 Weber, Max: 124 Wenzel of Luxembourg: 171 Widukind: 93 William of Malmesbury: 69, 90 William of Modena: 129 Wotan: 71, 82 Wulfila: 111 Zemon Davis, Natalie: 124, 265 Index of Place Names Aal: 109 Aarhus: 189–91 Acre: 107 Africa: 265 Aliati: 28 Alvastra: 157 Anagni: 174–75 Ångermanland: 28–29 Aragón: 264 Arboga: 256 Arctic Circle: 265 Ascheraden: 134 Asia: 98 Austria: 72 Baltic: 2, 4, 97–98, 100, 102, 107, 110, 121–34, 137–39, 141–42, 146–47, 263 Bavaria: 156 Bergen: 56, 189–90, 217, 239 Bertinoro: 216, 235 Birka: 25 Biskops-Arnö: 162–63 Björned: 28–30 Børglum: 189–91 Bohemia: 130 Bohuslän: 189 Bologna: 246–47 Borgarthing: 34, 44–53, 59, 61 Borgund: 16 Brandenburg: 196 Bremen: 139 British Isles: 9, 31–33, 35–36, 42–43, 45–46, 55, 58–60, 68, 90, 93, 156, 261, 264–65, 267 Brønnøy: 52 Brussels: 262 Burgos: 175 Castellamare di Stabia: 169 Cluny: 101–02, 261–62 Constantinople: 68–69 Continent see Europe Cordoba: 98 Dargun: 106–07 Denmark: 2–3, 6, 25, 28, 35–36, 50, 55, 61, 67–75, 77, 79–81, 84, 90–91, 93, 97–105, 107–13, 122, 137, 139, 143, 148, 184–85, 189, 191, 194–96, 206, 220, 239, 247, 262 Doberan: 106–07 Dorpat see Tartu Dünamunde: 143 Dvina: 134, 138–39, 147 Edessa: 102–03, 106 Eidsivathing: 44–45 Eik in Lårdal: 213 Eldena: 106 Empire see Germany England see British Isles Esrom: 106–07 Estonia: 95, 128–29, 132–35, 139, 141, 146–47, 156 Europe: 1–2, 4–5, 8, 17–18, 20, 31–32, 42–45, 53, 59–60, 62, 69, 83, 85, 89–93, 95–96, 98–100, 104–05, 110, 113, 133–34, 155–56, 170, 177, 181, 195, 209–10, 216, 222, 258, 261–64, 266 274 Faroe Islands: 189–90, 211 Fellin: 139 Finland: 3, 189, 191, 239–40 Flanders: 96, 99 Flensburg: 73, 80–81 France: 31–32, 89–93, 99, 162, 261, 263 Frisia: 105 Frosta: 52 Frostathing: 44–50, 52–53, 59, 61, 184 Fyn: 80 Gardar: 189–90 Gaul see France Germany: 3, 55, 59, 70–72, 80, 82–83, 90, 92, 97, 104, 107, 110–11, 127, 129, 134–35, 137, 139, 142–44, 146, 148, 155–56, 172, 187, 194–95, 261, 265–66 Gokstad: 51–52 Gotland: 32, 138 Gränna: 245, 254 Greece: 69 Greenland: 44, 71, 189, 211 Gulathing: 13–14, 33–34, 44–48, 184, 230, 263 Gulli: 50–51 Hälsingland: 28, 32 Härjedalen: 189 Haithabu see Hedeby Hamar: 190, 214, 222–25, 227, 230, 233 Hamburg-Bremen: 70 Hebrides: 44, 71 Hedeby: 25, 55 Hellested: 79 Høydalsmo: 213, 222 Hólar: 74, 189–90 Holm: 139, 146 Holøs: 51 Holstein: 59, 72, 104 Holy Land: 68–69, 96–97, 102, 106–08 Hungary: 53, 95, 261 Iberian Peninsula: 108, 264 Iceland: 3–4, 7, 12, 14–17, 19, 23, 28, 30, 32, 35, 44, 71–74, 95, 189, 191, 206, 211, 262, 266 Ireland: 46, 60, 71, 261, 265 Italy: 156–57, 170, 195, 206, 265–66 INDEX OF PLACE NAMES Järstad: 250–51, 254 Jelling: 67, 93–94, 111 Jerusalem: 97, 99–100, 108–10, 169, 264 Jerwan: 143 Jutland: 80, 109 Kallehave: 77 Kalmar: 100–02 Kammin: 194 Kaupang: 49, 51, 53–55 Keldudalur: 30 Kongshelle: 96 Kukenois: 146 Kurland: 129, 147 Læsø: 84 Launceston: 58 Lennewarden: 144 León and Castile: 264 Levant: 264 Lille Gullkronen: 51 Lincoln: 55, 58 Lincolnshire: 35 Linköping: 158, 162, 165–68, 173, 176, 189–90, 201, 238, 240–42, 244, 247–49, 257–58 Lithuania: 128–29, 134–35, 144, 146–47 Livonia: 97–98, 121–22, 128–29, 132, 135, 138, 141–44, 146, 148 Lucca: 93 Lund: 25, 81, 96, 121, 189–91, 197, 239 Luxeuil: 72 Lyon: 217 Magdeburg: 96–98, 100 Malmö: 78 Mecklenburg: 106–07 Mediterranean: 8, 69, 102, 264–65 Miklagard see Constantinople Morocco: 98 Motala: 240, 257 Münster: 53 Naples: 155, 169–70, 174–77, 266 Nazareth: 96 Netherlands: 70 Nidaros see Trondheim Nola: 175–76 Normandy: 99 INDEX OF PLACE NAMES Norra Vedbo: 240 Northumbria: 35 Norway: 2–5, 7–20, 27–28, 30, 33–35, 41–49, 52–53, 55–56, 59–62, 67–72, 75, 77, 80, 90, 93, 96, 100–01, 124, 172, 184–85, 189, 191, 206, 209, 211–13, 216–22, 225–26, 228, 230–32, 238, 262, 265 Novgorod see Russia Nyköping: 159–60 Øm: 109 Ørlandet: 52 Ösel: 129, 133, 135–37, 139–40, 145–47 Östergötland: 156, 161, 203, 244, 250, 252 Østfold: 51 Odense: 108, 189–91 Oldenburg: 53, 59, 97 Onarheim: 77 Oppdal: 52 Orkney Isles: 44, 71, 95, 211 Orléans: 162 Oseberg: 51–53 Oslo: 49–51, 53, 55, 58, 61, 189–91 Oslofjord see Oslo Paderborn: 252 Pala: 143 Palestine see Holy Land Paris: 113, 162 Pisa: 247 Poitiers: 175–76 Poland: 3, 92, 100, 156, 261 Pomerania: 132 Portugal: 105, 264 Provence: 169 Prussia: 72 Pskov: 139 Rauma: 52 Rheims: 114–15 Rhine: 70 Ribe: 25, 80, 104, 189–91 Riga: 97, 127, 135, 137–39, 146–47 Rissa: 52 Rome: 4, 70, 82, 156–57, 161, 164, 167, 173, 175–77, 182, 192, 194–95, 210–11, 216, 235, 247, 261–62, 264, 267 Romerike: 32 275 Roskilde: 25, 79, 81, 189–91 Russia: 139, 145 Saaremaa see Ösel Saccalia: 142–43 Säby: 240–41, 244–46, 249, 251–52, 254, 256–57 Scandinavia: 1–6, 23–28, 30–33, 35–36, 44, 46, 53, 61, 67–70, 72, 82–83, 85, 89–96, 98–100, 102–04, 106, 109–13, 122–23, 127, 148, 155, 177, 181, 184–85, 189–96, 199, 202–06, 209–10, 212, 253, 258, 261–67 Schleswig: 72, 80, 104 Sebbersund: 25 Selburg: 134 Setesdal: 16 Sicily: 100 Sigtuna: 25, 28 Sjælland: 107 Skänninge: 157, 249–52, 256–57 Skálholt: 74, 189–91, 206 Skåne: 250–51 Skara: 25, 189–90, 201, 220, 244 Skibet: 109 Småland: 101, 240, 264 Snåsa: 52 Sør-Gudbrandsdalen: 30 Somero: 240 Spain: 100, 105 Starby: 254 Starigard see Oldenburg Stavanger: 189–90 Steinvikholm: 56–57 Stockholm: 158 Store Dal: 51 Strängnäs: 189–90, 247, 256 Suessa: 194 Svealand: 101 Sweden: 2–6, 25–28, 32, 35, 54–55, 61, 67–68, 70–71, 76–77, 80, 83, 100, 131, 137, 155–60, 162, 165, 169–73, 175, 177, 184–86, 189, 191, 195, 201, 203, 206, 220, 237–39, 241, 243–46, 253, 255–58, 262, 266 Tallinn: 194 Tartu: 139 Telemark: 213, 222–25, 227, 230 276 Tingvoll: 52 Tønsberg: 49, 51, 55–56, 60, 217 Tofta: 161 Torsåker: 28–30 Treiden: 142 Trøndelag: 32, 44 Trondheim: 25, 49, 54–59, 62, 70–71, 75, 96, 189–91, 211, 218–19, 239 Turku: 189–92, 198–99, 206, 239–40 Üxküll: 145 Uggerløse: 79 Ullevi: 250–51 Uppland: 161 Uppsala: 27–28, 70, 162–163, 172, 174, 176, 189–91, 201, 239, 255 Vadstena: 156–62, 164, 166–67, 170–74, 176–77, 246, 249, 254, 257 Västerås: 28, 165, 189–90 Västergötland: 31, 96 Växjö: 158, 163–64, 189–90 Vesterø: 84 Vestfold: 49–51 Viborg: 98, 189–91 Videy: 73 Viljandi: 130 Virtsjärvi: 145 Wiek: 146 York: 55, 58–59 INDEX OF PLACE NAMES Acta Scandinavica All volumes in this series are evaluated by an Editorial Board, strictly on academic grounds, based on reports prepared by referees who have been commissioned by virtue of their specialism in the appropriate field. The Board ensures that the screening is done independently and without conflicts of interest. The definitive texts supplied by authors are also subject to review by the Board before being approved for publication. Further, the volumes are copyedited to conform to the publisher’s stylebook and to the best international academic standards in the field. In Series The Nordic Apocalypse: Approaches to Vǫluspá and Nordic Days of Judgement, ed. by Terry Gunnell and Annette Lassen (2013) In Preparation New Approaches to Early Law in Scandinavia, ed. by Stefan Brink and Lisa A. Collinson