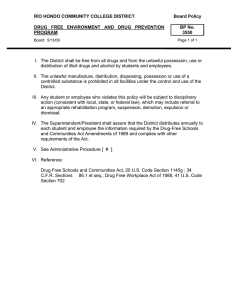

ISSN 1681-5157 Drug users and the law in the EU A balance between punishment and treatment Drug laws in the European Union (EU) seek continuously to strike a balance between punishment and treatment. The three United Nations (UN) conventions on drugs [1] limit drug use exclusively to medical or scientific purposes. While they do not call for illicit use of drugs to be considered a crime, the 1988 Convention — as a step towards tackling international drug trafficking — does identify possession for personal use to be regarded as such. Signatory countries are thus obliged to address the illegal possession of drugs for personal use, but retain their individual freedom to decide on the exact policies to be adopted. In framing their national laws, EU Member States have interpreted and applied this freedom taking their own characteristics, culture and priorities into account, while maintaining a prohibitive stance. The result is a variety of approaches EU-wide to illicit personal use of drugs and its preparatory acts of possession and acquisition. Yet, when comparing law with actual practice, national positions within the EU seem less divergent than might be expected. In many countries, judicial and administrative authorities increasingly seek opportunities to discharge offenders, or, failing that, arrangements that stop short of severe criminal punishment, such as fines, suspension of a driving licence, etc. ‘Relapse into drug abuse and crime is a common feature of drug addicts. Preventing and treating addiction, its causes and consequences can be difficult, time-consuming and costly — but this is the clear answer to breaking the expensive chain of drugs and crime.’ GEORGES ESTIEVENART, EMCDDA EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Nevertheless, data show that police action against drug users is rising — possibly due to greater drug prevalence [2] — and varies both within and between countries. Moreover, some cases of illicit personal use of drugs do continue to reach the courts and prison sentences are still given, especially to repeat offenders. Such inconsistencies in applying the law can confuse the public and affect the credibility of the legal system relating to personal drug use. An EMCDDA Insights publication, Prosecution of drug users in Europe: varying pathways to similar objectives [3] focuses on the issue in considerable depth and offers individual country reports. Quote: ‘While drug-related arrests are on the increase — with police resources concentrated on tackling cannabis users — justice systems in most countries increasingly seek opportunities to discharge drug offenders, apply “soft” sanctions or consider criminal measures as a last resort. The message we send citizens — especially the young — is confusing and often contradictory. An effective prosecution policy on drugs needs to be more consistent and therefore more credible.’ MIKE TRACE, CHAIRMAN EMCDDA MANAGEMENT BOARD Key policy issues at a glance 1. The UN drug conventions leave countries room for manoeuvre to control illicit possession of drugs for personal use as they see fit, without rigidly defining specific punishments. 2. Within the EU, laws regulating personal use of drugs vary from country to country. In some, punishment includes prison sentences; in others, possession for personal use has been decriminalised in recent years. 3. Police action against illicit use and possession of drugs, although differing within and between countries, is generally increasing in the EU. 4. Prosecutors in most Member States now lean towards non-criminal sanctions for drug use and possession offences. But firm action, including imprisonment, is still the usual outcome for addicts who sell drugs or commit property crime, especially when they are reoffenders. 5. Alternatives to criminal prosecution — usually of a therapeutic or social nature — are now widely available across the EU, but their application and effectiveness vary. 6. Programmes offering alternatives to prosecution can benefit from coordination between the justice and health systems. Rua da Cruz de Santa Apolónia, 23–25, P-1149-045 Lisbon • Tel. (351) 218 11 30 00 • Fax (351) 218 13 17 11 • http://www.emcdda.org Briefing 2 bimonthly Drugs in focus Drug users and the law — overview 1. UN conventions set the scene International drug law is based on the UN conventions of 1961, 1971 and 1988 [1]. It was Article 3.2 of the latter that first required signatories to characterise possession of drugs for personal use as a criminal offence. But it subjugates this requirement to the principles and concepts of national legal systems, leaving countries leeway to decide on the exact policy to be adopted. As a result, signatories have not felt obliged to adopt uniform legal measures against those found in possession of drugs for personal use. Moreover, the underlying philosophy of Article 3 of the 1988 Convention is improving the effectiveness of the criminal justice system in relation to international drug trafficking [4]. 2. Drug laws vary but show signs of convergence Laws regulating the use and possession for use of drugs vary considerably from one EU country to another. In some, the law prohibits such acts and allows prison sentences. In others, these acts are prohibited but sanctions tend to be lenient. The remainder do not consider drug use and possession for use as criminal offences. Developments over the last five years show similar laws and guidelines emerging within Member States’ criminal justice systems in response to drug users — notably a move towards more lenient measures for personal drug use. Some countries now legitimise practices that had become common. In so doing, they bring the law into line with police and prosecution practice, thus enhancing the law’s credibility. In Spain, Italy and Portugal, criminal sanctions do not apply to the possession of any drugs for personal use. Instead, sanctions tend to be administrative: a warning, fine or, particularly in Italy, suspension of a driving licence. In cases of addiction, treatment is required. Since 2001, Luxembourg law has envisaged only a fine for cannabis use and its transportation, possession and acquisition for personal use. In Belgium, Denmark, Germany and Austria, laws and guidelines indicate March–April 2002 that first offenders for illicit possession of drugs, especially cannabis, should not be punished. Instead, they are ‘invited’ to refrain from taking drugs in future, often with warnings and probation. In the Netherlands, possession for personal use of small amounts of cannabis is prohibited by law but tolerated under certain circumstances. In Ireland, possession of cannabis is punishable by a fine on the first or second conviction but a sentence for imprisonment is possible from the third offence onwards. Meanwhile, in the UK, a suggestion from the Home Secretary in 2001 that cannabis be reclassified as a ‘Class C’ rather than ‘Class B’ drug could render possession of cannabis for personal use a non-arrestable offence in the future. In France, a 1999 directive recommends only a warning for drug-use offences specifically. Finally, in Greece, Norway, Finland and Sweden, the law prohibiting use is reported to be applied ‘to the letter’. 3. Police action on the rise In several European countries, the principle of legality obliges the police to report for prosecution any offence of which they are aware. And research [3] suggests that most individuals suspected of offences of drug use or possession for use are, indeed, reported for prosecution. But police action varies both within and between countries. Norway, Finland and Sweden consider targeted police action a significant deterrent to drug use. Elsewhere in Europe, issues of public order and nuisance determine police intervention in dispersing open drug scenes. On the whole, police action against drug use or possession is reported to occur ‘accidentally’ in the course of routine patrolling — or when drug use becomes too visible or too dangerous. Data to 2000 show that, in many EU Member States, arrests for drug use and possession for use are on the rise [2]. In several countries, the majority of arrests for drug offences are for use or possession for use (see Figure 2), while offences of drug dealing or trafficking are Figure 1 — Most likely outcomes in prosecuting 'possession of drugs for personal use' Prosecution and conviction, followed by prison, fines or therapeutic measures Discharge or diversion leading to reduction of charges Discharge or diversion to alternative measures at prosecution (by law, directives, guidelines) Administrative sanctions or therapeutic measures (decriminalisation by law) Note: In this chart, the term ‘possession of drugs for personal use’ refers to possession of a small amount of drugs, with no graver offences involved (property crime, retail sale, etc.). NB: Luxembourg data: cannabis only. Source: European legal database on drugs (ELDD) ‘Country profiles’ (http://eldd.emcdda.org) and EMCDDA Insights No 5 [3]. Figure 2 — Drug use/possession offences amongst the total of drug law arrests % 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Germany cases, is not seen as sufficient to prevent criminal proceedings. Such offences usually lead to criminal sanctions, with repeat offenders liable to greater penalties. France Ireland Austria 5. Alternative measures gain ground Norway Portugal United Kingdom 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 Research shows that treatment of drug users in the criminal justice system can produce positive results [5], whether therapeutic, for drug dependence, or educational, for first-time use [6]. Figure 3 — Cannabis among total of drug use/possession arrests % 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Alternatives to criminal prosecution, usually therapeutic or social, are now widely available across the EU, although their impact and quality still vary. Germany France In some countries, such measures are under-used, due to legal constraints or general scepticism about their effectiveness. In others, treatment is the norm; in a few, its application is impeded by a lack of resources. Ireland Portugal United Kingdom 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 NB: In Figure 2, Austrian data are for misdemeanours (possession, dealing, etc.) involving small quantities. In both graphs, it should be noted that arrests for drug law offences are defined differently by EU countries. Source: 2001 Reitox national reports (standard tables). far less common. In some countries, cannabis is the substance involved in most offences of drug use or possession (see Figure 3). At present, there is little evidence that police action against drug users predominantly targets the most harmful situations and patterns of use. Some 60–90 % of arrests for all drug offences in Belgium, Germany, Greece, France, Ireland, Austria, Finland, Sweden and the UK are for use or possession for use of drugs. Cannabis is the main drug involved in 55–90 % of arrests for drug use and possession in Germany, France, Ireland and the UK. In Portugal, where the cannabis rate is among the lowest, arrests related to cannabis rose to 37 % of all drug use and possession arrests in 2000. Source: 2001 Reitox national reports (standard tables). 4. Prosecutors look for alternatives Today, EU countries’ prosecution policies favour alternatives to traditional criminal punishment for drug use and possession. Judicial authorities often refrain from criminal sanctions and choose from a range of alternatives. These can be fines, formal warnings, suspension of a driving licence, probation or diversion to treatment. Countries where drug addiction is considered the real cause of a drugrelated crime are more prepared to offer treatment instead of prosecution, even for more serious offences. Others are less lenient, with drug-related crimes leading automatically to imprisonment. 6. Justice and health: partnership is the key When the appropriate treatment is readily available, includes a social and rehabilitative component, and involves a partnership between the justice and the health authorities, research shows that it can be cost-effective in reducing relapses into crime and drug abuse [7]. Crucial to this process is effective, well-organised cooperation between the justice and health systems at prosecution level, targeting the most appropriate response (and resources) to each individual. Simple warnings are the usual response to illicit drug use and possession for use, especially for first offenders or when small quantities of cannabis are involved. These non-criminal options apply less to those involved in selling drugs or in theft to buy them. Any drug dependence that might have triggered such offences is generally taken into account, but, in most March–April 2002 15 Conclusions 5 Drug users and the law in the EU — policy considerations 2. While drug laws vary across the EU, there is a recent trend by Member States to attempt to bring the law into line with police and prosecution practices. This serves to strengthen the credibility of the law. 3. Effective police action in the field of drugs needs to be targeted primarily at the most harmful situations of drug-related crime. 4. In the case of drug use or possession, most Member States have implemented mechanisms to divert a high proportion of arrested users away from criminal punishment. 5. Where an arrested user is drug dependent, research indicates that diversion into treatment can produce significant health, social and crime-reduction benefits. 6. Close cooperation between justice and health agencies is recommended to ensure the effective management of diversion initiatives. Web information Key sources [1] United Nations (UN) (1961, 1971, [4] United Nations (UN) (1998), 1988), 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances, 1988 Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (http://www.incb.org/e/conv). Commentary on the United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances 1988, United Nations Publications, New York, 1998, pp. 48–99. [2] European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) (2001), 2001 Annual report on the state of the drugs problem in the European Union, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg, 2001, p.19. [3] European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) (2002), Prosecution of drug users in Europe: varying pathways to similar objectives, EMCDDA Insights series No 5, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg, 2002. [5] European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) (2001), An overview study: Assistance to drug users in European Union prisons, EMCDDA Scientific Report, Cranstoun Drug Services Publishing, London, 2001, pp. 201–217. [6] Aos, S., Phipps, P., Barnoski, R. and Lieb, R. (2001), The comparative costs and benefits of programmes to reduce crime, Washington State Institute for Public Policy, WA, United States (http://www.wa.gov/wsipp — version 4.0). [7] Hough, M. (1996), Drugs misuse and the criminal justice system: a review of the literature, Paper 15, Home Office, 1996, United Kingdom. OFFICIAL PUBLISHER: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. © European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2002. EUR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Georges Estievenart. EDITORS: Kathy Robertson, John Wright. AUTHORS: Danilo Ballotta, Brendan Hughes, Chloé Carpentier. GRAPHIC CONCEPTION: Dutton Merrifield, UK. Printed in Italy Drug-law ‘Country profiles’ http://eldd.emcdda.org/databases/ eldd_country_profiles.cfm Decriminalisation in Europe? Recent developments in legal approaches to drug use http://eldd.emcdda.org/databases/ eldd_comparative_analyses.cfm Main trends in national drug laws http://eldd.emcdda.org/trends/ trends.shtml Data on arrests (EMCDDA 2001 Annual report data library) http://annualreport.emcdda.org/en/ sources/index.html Drugs in focus is a series of policy briefings published by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), Lisbon. The briefings are published six times a year in the 11 official languages of the European Union plus Norwegian. Original language: English. They may also be downloaded from the EMCDDA web site (http://www.emcdda.org). Any item may be reproduced provided the source is acknowledged. For free subscriptions, please contact us by e-mail (info@emcdda.org). Register on the EMCDDA home page for updates of new products. TD-AD-02-002-EN-D 1. The underlying philosophy of the 1988 UN Convention, and its requirement to characterise possession of drugs for personal use as a criminal offence, relates more to strengthening the fight against international drug trafficking than to criminalising drug users. 6 This briefing summarises key aspects of, and trends in, the way the law treats drug users in the EU today, and indicates primary sources for further information. The EMCDDA believes the following points could form the basis of future policy considerations: