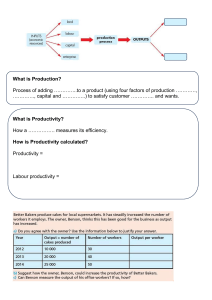

Empirical Essays on Military Service and the Labour Market Peter Bäckström Department of Economics Umeå School of Business, Economics and Statistics Umeå 2023 This work is protected by the Swedish Copyright Legislation (Act 1960:729) Doctoral thesis ISBN (print): 978-91-8070-079-5 ISBN (digital): 978-91-8070-080-1 ISSN: 0348-1018 Umeå Economic Studies No. 1012 Cover by Gabriella Dekombis, Inhousebyrån, Umeå University Electronic version available at: http://umu.diva-portal.org/ Printed by: CityPrint i Norr AB Umeå, Sweden 2023 Han sett så mången blodig dag, Så många faror delat, Ej segrar blott, men nederlag, Vars sår ej tid har helat; Så mycket, som ren världen glömt, Låg i hans trogna minne gömt. Ur Fänrik Ståls sägner av J.L. Runeberg Abstract This thesis consists of an introductory part and four self-contained papers that study empirical questions related to military service and the labour market. Paper [I] studies the relationship between civilian labour market conditions and the number of people who volunteer for military service in Sweden. I use panel data on Swedish counties for the years 2011 through 2015 and study the effect of civilian unemployment on the rate of applications from individuals aged 18 to 25 to initiate basic military training. The results indicate a positive and statistically significant relationship between the unemployment rate and the application rate, and suggest that the civilian labour market environment can give rise to non-trivial fluctuations in the supply of volunteers to the Swedish military. Paper [II] studies how local labour market conditions influence the quality composition of those who volunteer for military service in Sweden. I estimate a fixed-effects regression model on a panel data set containing cognitive ability test scores for those who applied for military basic training across Swedish municipalities during the period 2010 to 2016. The main finding is that if civilian employment rates at the local level go up, the average test score of those who volunteer for military service goes down. The results suggest that, due to the way in which different types of individuals select themselves into the military, the negative impact of a strong civilian economy on recruitment volumes is reinforced by a deterioration in recruit quality. Paper [III] studies the effect of peacekeeping on post-deployment earnings for military veterans. Using Swedish administrative data, we follow a sample of more than 11,000 veterans who were deployed for the first time during the period 1993-2010 for up to nine years after returning home. To deal with selection bias, we use difference-in-differences propensity score matching based on a rich set of covariates, including measures of individual ability, health and pre-deployment labour market attachment. We find that, overall, veterans’ post-deployment earnings are largely unaffected by their service. Even though Swedish veterans in the studied period tend to outperform their birth-cohort peers who did not serve, we show that this advantage in earnings disappears once we adjust for non-random selection into service. Paper [IV] studies the relationship between military deployment to Bosnia in the 1990s and adverse outcomes on the labour market. The analysis is based on longitudinal administrative data for a sample of 2275 young Swedish veterans who served as peacekeepers in Bosnia at some point during the years 1993–1999. I follow these veterans for up to 20 years after deployment. Using propensity score matching based on a rich set of covariates, I estimate the effects of deployment on three broad measures of labour market marginalisation: long-term unemployment, work disability, and social-welfare assistance. I find no indication of long-term labour market marginalisation of the veterans. Even though the veterans experienced an increase in the risk of unemployment in the years immediately following return from service, in the long run their attachment to the labour market is not affected negatively by their service. Keywords: Military recruitment, military labour market, military veterans, peacekeeping, earnings, labour market marginalisation i Sammanfattning Denna avhandling består av en inledande del och fyra självständiga kapitel som undersöker empiriska frågeställningar kopplade till militärtjänstgöring och arbetsmarknaden. Från det att värnplikten lades vilande år 2010, och fram till att den återinfördes år 2018, baserades Försvarsmaktens rekrytering helt och hållet på frivillighet. I det första kapitlet av min avhandling undersöker jag hur regionala arbetsmarknadsförhållanden påverkar antalet unga personer som frivilligt söker sig till Försvarsmakten. Genom att använda paneldata över svenska län för åren 2011-2015, analyserar jag effekten av regional arbetslöshet på antalet ansökningar om att påbörja grundläggande militär utbildning. Resultaten visar att det finns ett positivt samband mellan arbetslöshet och ansökningstryck. Slutsatsen är att konjunkturläget kan ha en förhållandevis stor inverkan på unga personers benägenhet att frivilligt söka sig till Försvarsmakten. I avhandlingens andra kapitel fortsätter jag att undersöka hur läget på arbetsmarknaden påverkar Försvarsmaktens frivilliga rekrytering. Genom att använda paneldata över svenska kommuner för perioden 2010-2016, analyserar jag hur förändringar i sysselsättningsgraden påverkar sammansättningen av personer som frivilligt söker sig till Försvarsmakten. Resultaten visar att en det finns ett negativt samband mellan sysselsättningsgraden och de sökandes genomsnittliga prestationer på försvarets begåvningstest. Det beror på att personer med relativt höga testvärden tenderar att välja bort Försvarsmakten när arbetsmarknadsläget i deras hemkommuner förbättras, medan ansökningarna från personer med relativt låga testvärden förblir mer eller mindre opåverkade. Slutsatsen är att den negativa effekt som en stark ekonomi har på rekryteringsvolymen går hand i hand med en försämring av kvaliteten på rekryteringsunderlaget. Många svenska män och kvinnor har tjänstgjort i fredsbevarande insatser runtomkring i världen. Trots detta, vet vi väldigt lite om utlandsveteranernas situation på arbetsmarknaden. I det tredje kapitlet av min avhandling (samförfattat med Niklas Hanes) undersöker vi om militär utlandstjänstgöring påverkar veteranernas inkomster på längre sikt. Vi använder registerdata från flera olika källor och följer mer än 11 000 svenska utlandsveteraner som tjänstgjorde under perioden 1993-2010, i upp till nio år efter hemkomsten. Resultaten visar att veteranernas inkomster, i genomsnitt, inte påverkas av tjänstgöringen. Svenska veteraner från den studerade perioden tenderar visserligen att ha högre inkomster än värnpliktiga ur samma årskull, men vi finner att detta beror på att de redan i utgångsläget var en positivt selekterad grupp. De svenskar som tjänstgjorde i fredsinsatserna i Bosnien på 1990-talet var stundtals under mycket stor press. I avhandlingens sista kapitel undersöker jag om dessa veteraner riskerade att hamna utanför arbetsmarknaden efter tjänstgöringen. Genom att använda registerdata från flera olika källor följer jag 2 275 veteraner som tjänstgjorde i Bosnien under perioden 1993-1999, i upp till 20 år efter hemkomsten. Resultaten visar att det, över tid, inte finns någon ökad risk för långtidsarbetslöshet, nedsatt arbetsförmåga eller behov av försörjningsstöd för veteranerna i den grupp jag studerar. Veteranerna hade visserligen en ökad risk för arbetslöshet under de första åren efter hemkomsten, men på lite längre sikt är de en väletablerad grupp på arbetsmarknaden. ii Acknowledgments Writing this thesis was a joy. Getting paid to read, write, and reflect on stuff that really interests you is indeed a dream job. Don´t get me wrong — it was no walk in the park. It took some time, and the road was not straight. I couldn’t have succeeded without the help of others. I owe gratitude to many persons who, all in their own way, have contributed to the completion of this thesis. First of all, I wish to thank my supervisor, professor Gauthier Lanot, and my cosupervisor, lieutenant (ret.) Niklas Hanes, for being my guides in writing this thesis. Thank you, Gauthier, for your critical feedback and for pushing me to keep improving my writing and empirical analyses. Without you, my thesis would probably be a mess. Thank you, Niklas, for helping me to ask the right questions and for your positive and encouraging way. The thesis project was made possible thanks to the collaborative efforts of Umeå School of Business, Economics and Statistics (USBE), the Swedish Defence Research Agency (FOI), the Industrial Doctoral School at Umeå University (IDS), and the Swedish Armed Forces Veterans Centre. Lars Persson at USBE and Christian Ifvarsson at FOI deserve credit for making the first part of the project possible. Anders Clareués and Monica Larsson at the Swedish Armed Forces, and Patrik Rydén at IDS, deserve credit for setting the stage for the second part of the project. Thank you to all my colleagues at FOI and at the Swedish Armed Forces Headquarters. Mattias Johansson deserves a special thanks for providing me with the freedom necessary to combine my academic pursuits with my daily work as a human slide rule under military command. Anders Clareués — again, thank you for your support and encouragement! Also, thank you to colonels Åkerblom and Demarkesse for letting me play around with my numbers. I spent most of the time writing the first part of this thesis away from the university, while working at FOI. Luckily, for the second part, I had the pleasure of working full-time together with other PhD-students and faculty at the Department of Economics. Stina, Balder, Sef, Samielle, Hanna, Linn, Johan G, Johan H, Gabrielle and Evelina — thank you for being great friends along the journey! And, thank you to all PhD-students in my cohort at IDS — meeting you from time to time was something I always looked forward to! I also owe special thanks to Mattias Vesterberg, Magnus Wikström, Linn Karlsson, Katharina Jenderny, Olle Westerlund, Evelina Bonnier, Balder Bergström, Anna Baranowska-Rataj, Johan Holmberg, and Richard Langlais, for reading and commenting on my papers. Thank you to my family and to all my friends. I´m grateful for each and every one of you. My friends for being great friends. My mother and my father for always being there and for providing their unconditional love and support. My brother and my sisters, along with their families, for being who they are. Finally, but most of all, I would like to express my deepest gratitude and love to mina tjejjor: Ida, Ella and Astrid. I dedicate this work to the three of you (and, also, to my mother Britt, who is probably more excited about this thesis than she was about my actual birth). Umeå in June 2023 Peter Bäckström iii iv This thesis consists of an introductory part and four self-contained papers that study empirical questions related to military service and the labour market: Paper [I] Bäckström, P. (2019). Are Economic Upturns Bad for Military Recruitment? A Study on Swedish Regional Data 2011–2015. Defence and Peace Economics, 30(7), 813-829 (reprinted with permission). Paper [II] Bäckström, P. (2022). Self-Selection and Recruit Quality in Sweden’s All Volunteer Force: Do Civilian Opportunities Matter? Defence and Peace Economics, 33(4), 438-453 (reprinted with permission). Paper [III] Bäckström, P., & Hanes, N. (2023). The Impact of Peacekeeping on Post-Deployment Earnings for Swedish Veterans. Umeå Economic Studies, No. 1010. Paper [IV] Bäckström, P. (2023). Swedish Veterans After Bosnia: The Relationship Between Military Deployment and Labour Market Marginalisation. Umeå Economic Studies, No. 1011. v vi 1 Introduction Until the end of the Cold War, the main task of the Swedish Armed Forces was to deter and ultimately fight off an enemy invasion. This all changed in the late 1990s and early 2000s. In the absence of any perceived military threat in Northern Europe, national defence was downplayed, and international military missions instead emerged as a main priority. Swedish national security was now to be achieved by promoting peace and security in other parts of the world. The deployment of peacekeeping troops abroad was an essential part of this new strategic concept (see Agrell, 2010, for a historical account). The increased focus on international military peace operations went hand in hand with a move towards the use of voluntary recruitment. Compulsory military conscription for males had been the foundation of the military manpower system in Sweden throughout the 20th century. However, as the focus of the Armed Forces changed, it became clear that training fewer and fewer conscripts, who could not be used in international service, was a costly way of manning international missions (Ministry of Defence, 2009, 2010). Eventually, conscription and mandatory military service in peacetime was (as it turned out, temporarily) abolished in 2010. The relatively small number of soldiers and sailors needed for the Swedish Armed Forces was now to be recruited on a voluntary basis and employed as professionals. In this thesis, I study some aspects of this transformation. The first part (comprising papers I and II) focuses on the supply of volunteers to the Swedish Armed Forces and the economic factors that affect the recruit flow. The second part (comprising papers III and IV) focuses on international military missions and the long-term labour market consequences for deployed military veterans. Through my research, I hope to provide insights into the dynamics of military recruitment and the impact of international military missions on the lives of those who serve in them. 2 The Supply of Volunteers The economics of military enlistment When conscription was abolished in 2010, the Swedish Armed Forces had to adapt to a new role. In order for voluntary recruitment to be successful, the Armed Forces needed to become "an attractive employer, requiring favourable conditions for those serving" (Ministry of Defence, 2009, p. 54). At the time, however, concerns were raised about the Armed Forces’ ability to compete with other employers in the labour market. In May 2010, several members of the Riksdag expressed fears that recruitment would be affected by the business cycle (Sveriges riksdag, 2010). Similarly, a 2007 report on long-term defence planning identified economic booms as a significant risk for recruitment and employee turnover in the Armed Forces (Swedish Armed Forces, 2007). 1 These concerns are indeed warranted from the perspective of economic theory. For those who decide to enlist, the perceived benefits of enlistment must be greater than the economic costs (Becker, 1993). Economic upturns are likely to be bad news for military recruiters since the opportunity cost of serving in the military increases when civilian wages rise or the chance of finding a civilian job improves. While most employers face similar challenges in attracting labour, the military differs in its limited ability to hire from outside its organisation. Instead, the military depend on a steady supply of new recruits entering at the bottom of the military hierarchy to ensure that there are enough personnel to staff upperlevel positions in the future; senior officers must essentially be "grown" from within the junior ranks (Asch & Warner, 2001; Warner, 1995). Thus, shortfalls in recruitment might have lasting effects on the performance on the military organisation; to some extent, recruitment outcomes today will impact the quality of generals 30 years from now. The idea that military recruitment outcomes are related to the business cycle is supported by a range of empirical studies from the U.S., which show that a strong civilian economy makes it less likely for people to enlist (Asch et al., 2010; Asch et al., 2009; Brown, 1985; Ellwood & Wise, 1987; Simon & Warner, 2007; Warner et al., 2003). Generalising empirical findings across countries is difficult, however. People’s preferences towards military work can vary greatly; while some are willing to serve for little pay, others may be hesitant to choose a military career even with high compensation (Rosen, 1974, 1986). If people have very divergent opinions about military life, then there will be relatively consistent number of volunteers each year, regardless of the state of the economy. On the other hand, if people are more similar in their appreciation of military life and many are indifferent between a civilian occupation or a military one, recruitment outcomes are likely to be more sensitive to changes in the attractiveness of civilian job alternatives. Thus, the distribution of preferences in the population determines how much the civilian economy actually affects enlistment supply (Rosen, 1986; Warner, 1995). Ultimately, whether the state of the economy is important for Swedish recruitment outcomes is an empirical question. Moreover, the military not only cares about the number of recruits, but also about the characteristics of those who volunteer for service. In particular, the military is interested in attracting high-quality recruits, in terms of physical and mental abilities. Enlistment incentives might not be the same for all individuals, however. Rather, opportunity costs will vary between different types of individuals, as some have more lucrative civilian career prospects than others. If recruit quality is positively correlated with civilian career prospects, then, at the margin, high-quality recruits may be more sensitive to enlistment incentives. This means that a strong civilian economy could have a dual impact on military recruitment: not only could it reduce the total number of recruits, but it could also disproportionately reduce the number of high-quality recruits. Hence, selfselection of individuals in and out of the recruit pool could actually worsen the impact of a strong civilian economy on military recruitment outcomes (Borjas, 2 1987; Roy, 1951). Again, whether or not this is actually the case is an empirical question. Understanding the factors that influence the flow of recruits is crucial for military employers in a voluntary recruitment environment. In the first two papers of this thesis, I explore the economic factors that affect the supply of volunteers to the Swedish Armed Forces. I ask two fundamental questions: does the state of the civilian economy impact the number of people willing to join the military, and does it affect the quality of those who volunteer? In the rest of this section, I provide empirical evidence and discuss the implications of my findings. Summary of papers [I] and [II] Does the state of the civilian economy affect the number of people who are willing to join the military? The transition to an all-volunteer military in 2010 came as the Swedish economy was recovering from the global financial crisis. In the first paper of this thesis, I explore if changing conditions in the civilian labour market affects the supply of labour to the military. Specifically, I study the effect of civilian unemployment rate on the rate of applications from individuals aged 18 to 25 to initiate basic military training, using panel data on Swedish counties for the years 2011 through 2015. Geographical regions that have high unemployment rates also tend to have high application rates. Figure 1 illustrates this positive association between unemployment rates and application rates, in the cross-section, and over time. However, geographical regions might have different characteristics that affect both military applications and unemployment. So, this simple association might be confounded by all sorts of unobserved background variables, such as the location of military bases or access to higher education. To further explore the relationship, I estimated a fixed-effects regression model. This approach allowed me to to isolate the effect from civilian unemployment by controlling for observed and unobserved differences across regions, as well as common trends on the national level. Moreover, to account for the possibility of reverse causality, i.e, that changes in the application rate in a region could influence the youth unemployment rate of that region, I used the variation in unemployment rates for older age groups as an instrument for regional labour market conditions for the youth population. The results from the fixed-effects regression analysis support the idea that falling unemployment rates are actually causing application rates to drop. The cross-sectional relationship is not simply due to other factors that vary across regions. Rather, the effect from unemployment on applications becomes stronger when controlling for unobserved differences across regions. Specifically, the results indicate that a one percentage point decrease in the unemployment rate is associated with a 0.3 percentage point decrease in the application rate. Given 3 (2) 3.5 4.0 3.0 Blekinge county Application rate (%) Percentage of full population, 18−25 years (1) 5.0 3.0 2.0 1.0 Gotland county 2.5 2.0 1.5 0.0 1.0 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Year 2.0 Application rate Unemployment rate 3.0 4.0 5.0 6.0 Unemployment rate (%) Figure 1: Application rates vs. Unemployment rates Notes: The left panel of the figure shows the annual percentage of the full Swedish population aged 18 to 25 that applied for basic military training over the period 2011-2015, together with the unemployment rate in the same age group. The right panel contains a scatter diagram of the cross-section of annual application rates against the unemployment rates by county over the same period. The sizes of the markers are in accordance with the size of the county population aged 18 to 25. From: “Are Economic Upturns Bad for Military Recruitment? A Study on Swedish Regional Data 2011–2015.”, by P. Bäckström, 2019, Defence and Peace Economics 30 (7): 813-829. Reprinted by permission of the publisher (Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com). that the average application rate at the national level was 1.4 over the studied period, the results suggest that changes in the civilian labour market can lead non-trivial fluctuations in the number of applications to initiate basic military training with the Swedish Armed Forces. Does the state of the civilian economy affect the quality composition of those who volunteer? The results from the first paper of this thesis suggest that fewer individuals want to join the military in Sweden when conditions in the civilian labour market improve. However, little is known about how the quality composition of volunteers responds to changes in economic circumstances. Do conditions in the civilian economy affect which type of people choose to join the military? Is the negative 4 impact of a strong civilian economy on recruitment volumes made worse by a decline in recruit quality? In the second paper, I explore these questions in the context of voluntary recruitment to the Swedish Armed Forces. One measure of recruit quality is intelligence, or cognitive ability. Since the 1940s, the Swedish military has been using cognitive ability tests to help determine the military service of conscripts (Carlstedt, 2000). In line with research that shows that psychometric measures of cognitive ability are predictive of performance in school and on the job (Deary et al., 2007; Gottfredson, 1997; Schmidt & Hunter, 2004; Strenze, 2007), cognitive ability has also been found to be an indicator of successfully completing military training (Carlstedt, 1999; Farina et al., 2019), as well as specific military tasks (Kavanagh, 2005; Scribner et al., 1986; Winkler, 1999). Moreover, low levels of cognitive ability has been found to increase combat veterans’ risk of developing mental health conditions, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), after service (Gale et al., 2008; Macklin et al., 1998; McNally & Shin, 1995). In this paper, I study how cognitive ability test scores of applicants for basic military training responds to changes in the economic environment. The empirical analysis is based on panel data for Swedish municipalities over the years 2010 to 2016. The results show that application rates from individuals who score high on the test is more responsive towards changes in the employment rate in the municipality of origin, compared to the application rate from individuals who score low. Consequently, if civilian employment rates go up, the average test score of those who volunteer for military service goes down. More specifically, if the civilian employment rate rises by one percentage point, the share of volunteers who score high enough to qualify for commissioned officer training programme falls by two percentage points. Consistent with the view that a strong civilian economy favours negative self-selection into the military, the results from this paper suggest that the negative impact on recruitment volumes of a strong civilian economy can indeed be reinforced by a deterioration in recruit quality. Why does it matter? The main findings from the first two papers of this thesis can be boiled down to one simple statement: conditions in the civilian economy matter for military recruitment outcomes. In poor economic times, military service may be an attractive alternative to individuals, but this also means the Armed Forces face challenges in attracting volunteers during strong economic periods. Additionally, my results suggest that the negative impact of a strong civilian economy on recruitment volumes is made worse by a decline in the quality of recruits. The main lesson to be learned from this is that the Armed Forces must be proactive in their recruiting strategies in order to overcome challenges associated with changes in the civilian business cycle. The government, however, has a unique tool for addressing staffing short- 5 ages in the military: the ability to conscript citizens into military service. In response to a deteriorating security environment and difficulties in recruitment, the Swedish government decided to re-instate peacetime conscription for both men and women starting January 1, 2018. This allows the government to tap into a larger pool of potential recruits and ensure that the military has the personnel it needs. However, conscription also has economic implications that must be considered. Compulsory conscription can be viewed as a form of in-kind tax that allows the government to collect less in fiscal taxes. So, whether military manpower is obtained through voluntary recruitment or compulsory conscription is, to some extent, a matter of how the costs to society of staffing and maintaining the military force are financed (see e.g. Friedman, 1967; Hansen and Weisbrod, 1967; Oi, 1967; Fisher, 1969; Poutvaara and Wagener, 2007). The findings of the first two papers of this thesis highlight an important fact: the stronger the state of the civilian economy, the higher the societal opportunity cost of allocating labour to the military sector. This is true regardless of the recruitment system. The only difference is who bears the burden: the taxpayer or the conscript. Under voluntary recruitment, self-selection of individuals into the military will assure that the opportunity costs of the recruits is kept at a minimum, whereas this selection, under a system based on conscription, is ultimately left in the hands of military manpower planners. As long as the size of the conscription cohort is substantially larger than the demand for military labour, there are important opportunities for the government to limit the societal cost of military conscription by prioritising occupational preferences and motivation in the military selection process.1 Moreover, the re-instatement of military conscription in Sweden might seem like an ideal way to avoid fluctuations in recruit quality by selecting only highquality recruits for military service. However, such a policy may not be optimal from a social welfare perspective, and it may not be desirable for the military organisation either. First, since the military does not have to pay a premium for selecting high-ability individuals, it is unlikely that the draft would balance a draftee’s productivity while in the military with the opportunity cost of removing them from the civilian labour market. In other words, the individuals selected for military service would, from a societal perspective, be too smart (Berck & Lipow, 2011). Second, since enlistment incentives for individuals with relatively high earning potential in the civilian sector are likely to be relatively weak, putting too much emphasis on ability might result in conscripts having too little motivation to remain in the military as professionals after their mandatory service. The challenge for the military selection system is to balance the needs of the military with individual opportunity costs and preferences. The results from the first two papers of this thesis suggest that this balancing act is especially 1 It should be noted, however, that military productivity might not be independent of individual preferences towards the military (Berck & Lipow, 2011). 6 delicate during economic upturns, when the civilian economy is strong and the opportunity cost of military service is high. 3 Peacekeeping and Labour Market Outcomes The labour market consequences of service Sweden and the Swedish Armed Forces have a long history of contributing to international peace operations.2 Since the 1950s, close to 70,000 Swedish men and women have been deployed as peacekeepers in many locations worldwide (Swedish Armed Forces, 2021). There is a growing body of literature on the long-term effects of deployment on the lives of Swedish military veterans. In general, these studies tend to emphasise the physical and mental well-being of the men and women who have served in peace operations (Michel et al., 2003, 2007; Pethrus, Frisell, et al., 2019; Pethrus et al., 2017; Pethrus, Reutfors, et al., 2019; Pethrus et al., 2022). However, we still know very little about how military veterans’ situation on the labour market after returning home are affected. To fully understand the long-term consequences of deployment, more research is needed in this area. Deployment can have both positive and negative effects on subsequent labour market outcomes for those who serve. On one hand, it has been long known that exposure to combat and traumatic events can have negative consequences for soldiers’ mental health (Cesur et al., 2013; Dobkin & Shabani, 2009; Hyams et al., 1996). Studies from the U.S. have consistently shown that mental health conditions, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), are associated with poor work related outcomes for Vietnam-era veterans, as well as more recent military combat veterans (Amick et al., 2018; Anderson & Mitchell, 1992; Ramchand et al., 2015; Savoca & Rosenheck, 2000; M. W. Smith et al., 2005). In this sense, military service in combat zones may impair veterans’ ability to re-integrate into civilian life and the civilian labour market after returning home. Additionally, military service can interrupt veterans’ civilian careers, leading to lost labour market experience and delayed investments in human capital that can worsen their labour market outcomes (Albrecht et al., 1999; Angrist, 1990; Lyk-Jensen, 2018; Paloyo, 2014). On the other hand, soldiers may develop valuable new skills and receive training during their service that could be useful in a civilian job. For instance, military leadership training, discipline, and experience working with others under difficult conditions may be beneficial and lead to improved outcomes on the labour market after returning home (Elder, 1986; Goldberg & Warner, 1987; Grönqvist & Lindqvist, 2016; Kleykamp, 2009; Mangum & Ball, 1989). These 2 Here, the term peace operations refers to military operations based on a mandate from the UN Security Council, including both peace keeping and peace enforcement. I use the term peacekeepers to describe those serving in all types of UN-mandated peace operations. 7 skills can help veterans transition from the military to civilian work environments, and may be particularly valuable for members of less advantaged groups. Indeed, a recent study by Greenberg et al. (2022) finds that military service in the U.S. promotes social mobility by expanding post-service employment opportunities for minorities. In the last two papers of this thesis, I contribute to the existing literature by studying the effects of deployment to an international peace operation on veterans’ subsequent labour market outcomes. The papers aim to answer two important questions: Does peacekeeping affect earnings in the long term, and are veterans at an increased risk of becoming marginalised in the labour market after returning home? The rest of this section summarises my findings and discusses the implications of my results. Summary of papers [III] and [IV] Does peacekeeping affect earnings in the long run? Despite Sweden’s long history of participating in international peace operations, there has been surprisingly little research on how these experiences affect veterans’ labour market outcomes in the long run. In the third paper of this thesis, I and my co-author Niklas Hanes study the effect of peacekeeping on post-deployment earnings for Swedish veterans. Using rich administrative data, we followed a sample of more than 11,000 Swedish veterans, who were deployed for the first time during the period 1993-2010, for up to nine years after returning home. Measuring the causal effects of military deployment is complicated by selection issues. All veterans from the time period studied volunteered for service and were actively screened and selected by the military prior to deployment. Previous research has shown that this has resulted in Swedish veterans being a selected group of mentally and physically healthy individuals with above average levels of cognitive and non-cognitive ability (Pethrus, Frisell, et al., 2019; Pethrus et al., 2017; Pethrus, Reutfors, et al., 2019). Since these pre-deployment characteristics are likely to be correlated with potential post-deployment labour market outcomes (Edin et al., 2022; Lindqvist & Vestman, 2011), simply comparing veterans to the general population is likely to lead to biased estimates of the effects of service. To address selection bias, we used a difference-in-differences propensity score matching approach that accounted for a wide range of individual characteristics, including ability, health, and pre-deployment labour market attachment. This allowed us to adjust for observed pre-deployment differences, as well as for selection bias stemming from unobserved differences between individuals that are constant over time (Heckman et al., 1998; Heckman et al., 1997; J. A. Smith & Todd, 2005). Our results indicate that, on average, the veterans in our sample did not experience any large long-term earnings effects as a result of their service. Indeed, 8 1500 Effect on annual earnings (100s of SEK) 500 1000 0 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 Time to/since first deployment (years) 7 8 9 Figure 2: Impact of deployment on average annual earnings. Notes: Matched difference-in-differences estimates of the average treatment effect from first-time deployment 1993-2010 on veterans’ annual earnings (100s of SEK in 2019 prices) for up to nine years after deployment. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Year 0 refers to the calendar year when a veteran was deployed for the first time. Baseline year is year -2. 100 SEK is approximately $10, £8 or 10 euro. From: "The Impact of Peacekeeping on Post-Deployment Earnings for Swedish Veterans.”, by P. Bäckström and N. Hanes, 2023, Umeå Economic Studies, No. 1010. Swedish veterans from the studied period tend to earn more than conscripts from the same birth cohort. However, once we adjust for non-random selection into service, this earnings advantage disappears. Figure 2 illustrates the impact of deployment on average earnings, after accounting for observed and unobserved differences between veterans and non-veterans. For the full sample of veterans, the point estimates of the earnings effects are close to zero for all follow-up times beyond the first year after returning home, with confidence intervals that are small enough to rule out any large long-term earnings effects. Does peacekeeping increase the risk of labour market marginalisation? The Swedish peacekeepers who were deployed to Bosnia in the 1990s found themselves in the midst of a violent civil war marked by war crimes and atroc9 ities, and were at times under severe pressure. Over the years, the well-being of these veterans has been a concern for many people, but little is known about how they have fared on the labour market after returning home. In the fourth paper of this thesis, I provide novel evidence on the relationship between military deployment to Bosnia and adverse outcomes on the labour market. The analysis is based on rich administrative data for a sample of 2275 young Swedish veterans who served as peacekeepers in Bosnia at some point during the years 1993–1999. Using propensity score matching, I followed these veterans for up to 20 years and compared the veterans’ risk of being marginalised in the labour market to that of a matched comparison group of non-veterans from the same birth-cohort. I find that veterans who were deployed to Bosnia in the 1990s did not face any increased risk of long-term labour market marginalisation after returning home. Figure 3 illustrates the impact of deployment to Bosnia on work disability, social-welfare assistance and long-term unemployment. Even though the veterans experienced an increased risk of unemployment in the years immediately following return from service, in the long run their attachment to the labour market is not affected negatively by their service. Despite the challenges that these soldiers faced, my findings show that their deployment to Bosnia did not have a negative impact on their labour market outcomes in the long run. 10 .03 Work disability .005 Proportion .01 .02 Estimated effect 0 -.005 -.01 0 -.015 0 4 8 12 16 Years to/since deployment year 20 0 4 8 12 16 20 Years to/since deployment year Social welfare assistance Proportion .05 Estimated effect .1 .02 0 -.02 0 -.04 0 4 8 12 16 Years to/since deployment year 20 0 4 8 12 16 20 Years to/since deployment year Long-term unemployment Proportion .1 Estimated effect .2 .1 0 0 -.1 0 4 8 12 16 Years to/since deployment year 20 0 Veterans 4 8 12 16 20 Years to/since deployment year Matched comparisons Figure 3: Impact of deployment to Bosnia on labour market marginalisation Notes: The left panel of this figure shows the observed outcomes for a sample of 2275 veterans deployed to Bosnia in the 1990s (solid line) together with the outcomes for the matched comparison group of birth-cohort peers who did not serve (dashed line). The right panel shows the estimated average treatment effect on the treated (ATT), together with 95% confidence intervals. All outcome variables are indicator variables (i.e., dummy variables). Year 0 refers to the calendar year when a veteran was deployed for the first time. From: "Swedish Veterans After Bosnia: The Relationship Between Military Deployment and Labour Market Marginalisation”, by P. Bäckström, 2023, Umeå Economic Studies, No. 1011. 11 Why does it matter? Like in many other countries, there is an ongoing debate in Sweden about the well-being of military veterans and the long-term consequences of deployment. Some have argued that military veterans are harmed by their service and that they struggle to re-integrate into civilian society (see, for example, Strömberg et al., 2013; and Häggström, 2013), whereas others have warned against letting negative aspects of service dominate the narrative (Neovius et al., 2014; Ramnerup, 2013). My findings challenge the notion that Swedish veterans struggle on the labour market. Instead, the last two papers of this thesis show that veterans, on average, perform well on the labour market after returning home. In fact, they do so well that they manage to keep up, in terms of earnings, with those who did not serve and therefore had a head start on the labour market. Even the group of veterans in my sample who arguably experienced the most stressful events during their service — the men and women deployed to Bosnia during the early 1990s — show no signs of long-term labour market marginalisation after returning home. In the long run, these veterans may even experience less difficulties than their non-veteran peers in the matched comparison group. These results are in line with previous Swedish studies that highlight the well-being of Swedish peace veterans, and should provide important insights, not only for policymakers and military planners, but also for the general public. Even though it is important not to neglect individual sacrifices and hardships, incorrectly labelling the collective of Swedish military veterans as victims or sufferers might be harmful, not only for the individual veteran, but for the status of the whole military profession. Instead, we should acknowledge this group for who they are: a highly selected group of individuals who not only have made great contributions to society as peacekeepers abroad, but continue to do so by being valuable members of the labour force after returning home. There are, however, some policy points to be made. First, the absence of adverse effects, for the veterans studied in this thesis, is likely to be connected to active selection, as well as pre-deployment training and post-deployment support. Any changes to the military selection and training system must be carefully assessed with respect to how they affect protective and/or risk factors for adverse post-deployment outcomes (DiGangi et al., 2013; Weisæth, 1998; Xue et al., 2015). Second, even though veterans appear to manage well in the labour market in the long run, depending on the labour market situation at home, they may still struggle with establishing themselves on the labour market in the short run. The Swedish Armed Forces plays a key role in making this transition as smooth as possible for the individual veteran. Third, the absence of adverse average effects must not be confused with the absence of negative outcomes for individual veterans; the support system for Swedish veterans is a vital part of ensuring that no individual is neglected, and may very well be part of the explanation for the findings of this thesis. 12 References Agrell, W. (2010). Fredens illusioner. Det nationella försvarets nedgång och fall 19882009. Bokförlaget Atlantis. Albrecht, J. W., Edin, P.-A., Sundström, M., & Vroman, S. B. (1999). Career interruptions and subsequent earnings: A reexamination using Swedish data. Journal of Human Resources, 294–311. Amick, M. M., Meterko, M., Fortier, C. B., Fonda, J. R., Milberg, W. P., & McGlinchey, R. E. (2018). The deployment trauma phenotype and employment status in veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 33(2), E30. Anderson, K. H., & Mitchell, J. M. (1992). Effects of military experience on mental health problems and work behavior. Medical Care, 30(6), 554–563. Angrist, J. D. (1990). Lifetime Earnings and the Vietnam Era Draft Lottery: Evidence from Social Security Administrative Records. The American Economic Review, 80(3), 313–336. Asch, B. J., Heaton, P., Hosek, J., Martorell, F., Simon, C., & Warner, J. T. (2010). Cash incentives and military enlistment, attrition, and reenlistment (tech. rep.). RAND Corporation. Asch, B. J., Heaton, P., & Savych, B. (2009). Recruiting Minorities: What Explains Recent Trends in the Army and Navy? (Tech. rep.). RAND Corporation. Asch, B. J., & Warner, J. T. (2001). A theory of compensation and personnel policy in hierarchical organizations with application to the United States military. Journal of Labor Economics, 19(3), 523–562. Becker, G. S. (1993). Nobel lecture: The economic way of looking at behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 101(3), 385–409. Berck, P., & Lipow, J. (2011). Military conscription and the (socially) optimal number of boots on the ground. Southern Economic Journal, 78(1), 95–106. Borjas, G. J. (1987). Self-selection and the earnings of immigrants. The American Economic Review, 77(4), 531–553. Brown, C. (1985). Military Enlistments: What Can We Learn from Geographic Variation? The American Economic Review, 75(1), 228–234. Carlstedt, B. (1999). Validering av inskrivningsprövningen mot vitsord från den militära grundutbildningen [Validation of the enlistment test against grades from military basic training]. Ledarskapsinstitutionen, Försvarshögskolan. Carlstedt, B. (2000). Cognitive abilities - aspects of structure, process and measurement (Doctoral dissertation). University of Gothenburg. Cesur, R., Sabia, J. J., & Tekin, E. (2013). The psychological costs of war: Military combat and mental health. Journal of Health Economics, 32(1), 51–65. Deary, I. J., Strand, S., Smith, P., & Fernandes, C. (2007). Intelligence and educational achievement. Intelligence, 35(1), 13–21. DiGangi, J. A., Gomez, D., Mendoza, L., Jason, L. A., Keys, C. B., & Koenen, K. C. (2013). Pretrauma risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder: A 13 systematic review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(6), 728– 744. Dobkin, C., & Shabani, R. (2009). The health effects of military service: Evidence from the Vietnam draft. Economic Inquiry, 47(1), 69–80. Edin, P.-A., Fredriksson, P., Nybom, M., & Öckert, B. (2022). The rising return to noncognitive skill. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 14(2), 78–100. Elder, G. H. (1986). Military times and turning points in men’s lives. Developmental Psychology, 22(2), 233. Ellwood, D. T., & Wise, D. A. (1987). Uncle Sam Wants You-Sometimes: Military Enlistments and the Youth Labor Market. Public Sector Payrolls (pp. 97– 118). University of Chicago Press. Farina, E. K., Thompson, L. A., Knapik, J. J., Pasiakos, S. M., McClung, J. P., & Lieberman, H. R. (2019). Physical performance, demographic, psychological, and physiological predictors of success in the US Army Special Forces Assessment and Selection course. Physiology & Behavior, 210, 112647. Fisher, A. C. (1969). The Cost of the Draft and the Cost of Ending the Draft. The American Economic Review, 59(3), 239–254. Friedman, M. (1967). Why not a volunteer army? New Individualist Review, 4(4), 3–9. Gale, C. R., Deary, I. J., Boyle, S. H., Barefoot, J., Mortensen, L. H., & Batty, G. D. (2008). Cognitive ability in early adulthood and risk of 5 specific psychiatric disorders in middle age: the Vietnam experience study. Archives of general psychiatry, 65(12), 1410–1418. Goldberg, M. S., & Warner, J. T. (1987). Military experience, civilian experience, and the earnings of veterans. Journal of Human Resources, 62–81. Gottfredson, L. S. (1997). Why g matters: The complexity of everyday life. Intelligence, 24(1), 79–132. Greenberg, K., Gudgeon, M., Isen, A., Miller, C., & Patterson, R. (2022). Army Service in the All-Volunteer Era. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 137(4), 2363–2418. Grönqvist, E., & Lindqvist, E. (2016). The making of a manager: Evidence from military officer training. Journal of Labor Economics, 34(4), 869–898. Häggström, B. (2013). Krigarna som landet glömde [The warriors that were forgotten]. Sydsvenskan. Retrieved May 2, 2022, from https : / / www. sydsvenskan.se/2013-07-21/krigarna-som-landet-glomde Hansen, W. L., & Weisbrod, B. A. (1967). Economics of the military draft. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 81(3), 395–421. Heckman, J. J., Ichimura, H., Smith, J., & Todd, P. (1998). Characterizing Selection Bias Using Experimental Data. Econometrica, 66(5), 1017. Heckman, J. J., Ichimura, H., & Todd, P. E. (1997). Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator: Evidence from evaluating a job training programme. The Review of Economic Studies, 64(4), 605–654. 14 Hyams, K. C., Wignall, F. S., & Roswell, R. (1996). War syndromes and their evaluation: From the US Civil War to the Persian Gulf War. Annals of Internal Medicine, 125(5), 398–405. Kavanagh, J. (2005). Determinants of productivity for military personnel. a review of findings on the contribution of experience, training, and aptitude to military performance (tech. rep.). RAND Corporation. Kleykamp, M. (2009). A great place to start? The effect of prior military service on hiring. Armed Forces & Society, 35(2), 266–285. Lindqvist, E., & Vestman, R. (2011). The labor market returns to cognitive and noncognitive ability: Evidence from the Swedish enlistment. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 3(1), 101–28. Lyk-Jensen, S. V. (2018). Does peacetime military service affect crime? New evidence from Denmark’s conscription lotteries. Labour Economics, 52, 245– 262. Macklin, M. L., Metzger, L. J., Litz, B. T., McNally, R. J., Lasko, N. B., Orr, S. P., & Pitman, R. K. (1998). Lower precombat intelligence is a risk factor for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(2), 323. Mangum, S. L., & Ball, D. E. (1989). The transferability of military-provided occupational training in the post-draft era. ILR Review, 42(2), 230–245. McNally, R. J., & Shin, L. M. (1995). Association of intelligence with severity of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in Vietnam Combat veterans. The American Journal of Psychiatry. Michel, P.-O., Lundin, T., & Larsson, G. (2003). Stress reactions among Swedish peacekeeping soldiers serving in Bosnia: A longitudinal study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16(6), 589–593. Michel, P.-O., Lundin, T., & Larsson, G. (2007). Suicide rate among former Swedish peacekeeping personnel. Military Medicine, 172(3), 278–282. Ministry of Defence. (2009). Slutbetänkande av Utredningen om totalförsvarsplikten [Final report from the Total Defence Service Commission] (Committee Report SOU 2009:63). Ministry of Defence. Stockholm. Ministry of Defence. (2010). Betänkande av Utredningen om Försvarsmaktens framtida personalförsörjning. Personalförsörjningen i ett reformerat försvar [Final report of the Committee on the future manpower system of the Swedish Armed Forces] (Committee Report SOU 2010:86). Ministry of Defence. Stockholm. Neovius, M., Reutfors, J., Pethrus, C.-M., Neovius, K., & Karlsson, M. (2014). Sjukförklara inte krigsveteraner [Do not call war veterans sick]. Svenska Dagbladet. Retrieved December 5, 2022, from https://www.svd.se/a/ 7f7b6c16-1f25-3b4f-92ce-a9f30ece7f6b/sjukforklara-inte-krigsveteraner Oi, W. Y. (1967). The economic cost of the draft. The American Economic Review, 57(2), 39–62. Paloyo, A. R. (2014). The Impact of Military Service on Future Labor-Market Outcome. The Evolving Boundaries of Defence: An Assessment of Recent Shifts in Defence Activities. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. 15 Pethrus, C.-M., Frisell, T., Reutfors, J., Johansson, K., Neovius, K., Söderling, J. K., Bruze, G., & Neovius, M. (2019). Violent crime among Swedish military veterans after deployment to Afghanistan: A population-based matched cohort study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 48(5), 1604–1613. Pethrus, C.-M., Johansson, K., Neovius, K., Reutfors, J., Sundström, J., & Neovius, M. (2017). Suicide and all-cause mortality in Swedish deployed military veterans: A population-based matched cohort study. BMJ open, 7(9), e014034. Pethrus, C.-M., Reutfors, J., Johansson, K., Neovius, K., Söderling, J., Neovius, M., & Bruze, G. (2019). Marriage and divorce after military deployment to Afghanistan: A matched cohort study from Sweden. PLOS ONE, 14(2), e0207981. Pethrus, C.-M., Vedtofte, M. S., Neovius, K., Borud, E. K., & Neovius, M. (2022). Pooled analysis of all-cause and cause-specific mortality among Nordic military veterans following international deployment. BMJ open, 12(4), e052313. Poutvaara, P., & Wagener, A. (2007). Conscription: Economic costs and political allure. Economics of Peace and Security Journal, 2(1). Ramchand, R., Rudavsky, R., Grant, S., Tanielian, T., & Jaycox, L. (2015). Prevalence of, risk factors for, and consequences of posttraumatic stress disorder and other mental health problems in military populations deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17(5), 1–11. Ramnerup, A. (2013). ”Krigsveteranerna tas inte tillvara i Sverige” ["War veterans are not made use of in Sweden"]. Svenska Dagbladet. Retrieved December 5, 2022, from https://www.svd.se/a/c48d585e-7bf7-3a1e-bda6683c68a75a28/krigsveteranerna-tas-inte-tillvara-i-sverige Rosen, S. (1974). Hedonic prices and implicit markets: Product differentiation in pure competition. Journal of Political Economy, 82(1), 34–55. Rosen, S. (1986). The theory of equalizing differences. Handbook of Labor Economics, 1, 641–692. Roy, A. D. (1951). Some thoughts on the distribution of earnings. Oxford Economic Papers, 3(2), 135–146. Savoca, E., & Rosenheck, R. (2000). The civilian labor market experiences of Vietnam-era veterans: The influence of psychiatric disorders. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 3(4), 199–207. Schmidt, F. L., & Hunter, J. (2004). General mental ability in the world of work: Occupational attainment and job performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(1), 162. Scribner, B. L., Smith, D. A., Baldwin, R. H., & Phillips, R. L. (1986). Are smart tankers better? AFQT and military A productivity. Armed Forces & Society, 12(2), 193–206. Simon, C. J., & Warner, J. T. (2007). Managing the all-volunteer force in a time of war. The Economics of Peace and Security Journal, 2(1). 16 Smith, J. A., & Todd, P. E. (2005). Does matching overcome LaLonde’s critique of nonexperimental estimators? Journal of Econometrics, 125(1-2), 305–353. Smith, M. W., Schnurr, P. P., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2005). Employment outcomes and PTSD symptom severity. Mental Health Services Research, 7(2), 89– 101. Strenze, T. (2007). Intelligence and socioeconomic success: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal research. Intelligence, 35(5), 401–426. Strömberg, J., Hultkrantz, L., Bom, J., & Hellbergh, D. (2013). Svenska krigsveteraner stupar i det tysta [Swedish war veterans perish in silence]. GöteborgsPosten. Retrieved April 22, 2022, from https : / / www. gp . se / debatt / svenska-krigsveteraner-stupar-i-det-tysta-1.544760 Sveriges riksdag. (2010). Minutes of chamber proceedings 19 may 2010 [Parliamentary Record 2009/10:121, § 5]. Swedish Armed Forces. (2007). Rapport från perspektivstudien hösten 2007 – Ett hållbart försvar för framtida säkerhet [Report on long-term defence planning autumn 2007] (tech. rep. Document no. 23 382:63862). Swedish Armed Forces Headquarters. Swedish Armed Forces. (2021). Utlandsveteraner i siffror. Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://www.forsvarsmakten.se/sv/utlandsveteraner-ochanhoriga/for-utlandsveteraner/utlandsveteraner-i-siffror/ Warner, J. T. (1995). The economics of military manpower. Handbook of Defense Economics, 1, 347–398. Warner, J. T., Simon, C., & Payne, D. (2003). The military recruiting productivity slowdown: The roles of resources, opportunity cost and the tastes of youth. Defence and Peace Economics, 14(5), 329–342. Weisæth, L. (1998). Vulnerability and protective factors for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 52(S1), S39–S44. Winkler, J. D. (1999). Are smart communicators better? Soldier aptitude and team performance. Military Psychology, 11(4), 405–422. Xue, C., Ge, Y., Tang, B., Liu, Y., Kang, P., Wang, M., & Zhang, L. (2015). A meta-analysis of risk factors for combat-related PTSD among military personnel and veterans. PLOS ONE, 10(3), e0120270. 17