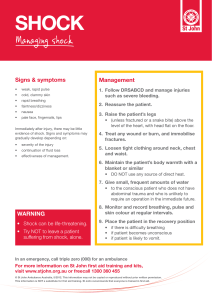

Chapter 42 Shock, Sepsis, and Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome KEY POINTS SHOCK • Shock is a syndrome characterized by decreased tissue perfusion and impaired cellular metabolism resulting in an imbalance between the supply of and demand for O2 and nutrients. • The 4 main categories of shock are cardiogenic, hypovolemic, distributive (includes septic, anaphylactic, and neurogenic shock), and obstructive. Cardiogenic Shock • Cardiogenic shock occurs when either systolic or diastolic dysfunction of the pumping action of the heart results in reduced cardiac output (CO). • Causes of cardiogenic shock include acute myocardial infarction (MI), cardiomyopathy, blunt cardiac injury, severe systemic or pulmonary hypertension, and myocardial depression from metabolic problems. • Manifestations of cardiogenic shock include tachycardia, hypotension, a narrowed pulse pressure, tachypnea, pulmonary congestion, cyanosis, pallor, cool and clammy skin, diaphoresis, decreased capillary refill time, anxiety, confusion, and agitation. 1 Copyright © 2023 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. Hypovolemic Shock • Hypovolemic shock occurs from inadequate fluid volume in the intravascular space to support adequate perfusion. • Absolute hypovolemia results when fluid is lost through hemorrhage, gastrointestinal (GI) loss (e.g., vomiting, diarrhea), fistula drainage, diabetes insipidus, or diuresis. • Relative hypovolemia results when fluid volume moves out of the vascular space into extravascular space, such as with sepsis and burns. • Manifestations depend on the extent of injury, age, and general state of health. They may include anxiety; an increase in heart rate, CO, and respiratory rate and depth; and a decrease in stroke volume, pulmonary artery wedge pressure (PAWP), and urine output. Neurogenic Shock • Neurogenic shock is a hemodynamic phenomenon that can occur within 30 minutes of a spinal cord injury at the fifth thoracic (T5) vertebra or above and last up to 6 weeks, or in response to spinal anesthesia. • The classic manifestations are hypotension (from the massive vasodilation) and bradycardia (from unopposed parasympathetic stimulation). The patient may not be able to regulate body temperature. Anaphylactic Shock • Anaphylactic shock is an acute and life-threatening hypersensitivity (allergic) reaction. • The reaction is caused by a sensitizing substance (e.g., drug, chemical, vaccine, food, insect venom). 2 Copyright © 2023 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. • Immediate reaction causes massive vasodilation, release of vasoactive mediators, and an increase in capillary permeability resulting in fluid leaks from the vascular space into the interstitial space. • Manifestations include anxiety, confusion, dizziness, chest pain, incontinence, swelling of the lips and tongue, wheezing, stridor, flushing, pruritus, urticaria, and angioedema. Septic Shock • Sepsis is a life-threatening syndrome in response to an infection. • It is characterized by a dysregulated patient response along with new organ dysfunction related to the infection. • Septic shock is the presence of sepsis with hypotension despite adequate fluid resuscitation along with the presence of inadequate tissue perfusion. • In severe sepsis and septic shock, the body’s response to infection is exaggerated, resulting in an increase in inflammation and coagulation, and a decrease in fibrinolysis. • Septic shock has 3 major pathophysiologic effects: vasodilation, maldistribution of blood flow, and myocardial depression. • Patients often have hypotension, respiratory failure, altered neurologic status, acute kidney injury with decreased urine output, and GI dysfunction. Obstructive Shock • Obstructive shock develops when a physical obstruction to blood flow occurs with a decreased CO. 3 Copyright © 2023 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. • Common causes include restricted diastolic filling of the right ventricle from compression and abdominal compartment syndrome. • Patients may have a decreased CO, increased afterload, and variable left ventricular filling pressures depending on the obstruction. Other signs include jugular venous distention and pulsus paradoxus. Stages of Shock • The initial stage of shock that occurs at a cellular level is usually not clinically apparent. • The compensatory stage is clinically apparent and involves neural, hormonal, and biochemical compensatory mechanisms to try to overcome the increasing consequences of anaerobic metabolism and to maintain homeostasis. • The progressive stage of shock begins as compensatory mechanisms fail and aggressive interventions are needed to prevent the development of multiple organ dysfunction system (MODS). • In the refractory stage, decreased perfusion from peripheral vasoconstriction and decreased CO worsen anaerobic metabolism. The patient will have profound hypotension and hypoxemia, as well as organ failure. At this stage, recovery is unlikely. Diagnostic Studies • There is no single diagnostic study to determine shock. The diagnosis is established from a detailed history and physical examination findings. 4 Copyright © 2023 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. • Studies that aid in the diagnosis include a serum lactate, base deficit, 12-lead ECG, continuous cardiac monitoring, chest x-ray, continuous pulse oximetry, and hemodynamic monitoring. Interprofessional Care • Successful management of the patient in shock includes: (1) identifying patients at risk for the development of shock; (2) integrating the patient’s history, physical assessment, and clinical findings to establish a diagnosis; (3) interventions to control or eliminate the cause of the decreased perfusion; (4) protecting target and distal organs from dysfunction; and (5) providing multisystem supportive care. • General management strategies for a patient in shock begin with ensuring that the patient has a patent airway and O2 delivery is optimized. The cornerstone of therapy for septic, hypovolemic, and anaphylactic shock is volume expansion with the appropriate fluid. • The goal of drug therapy for shock is to correct the decreased tissue perfusion resulting in tissue hypoxia. Vasopressor or vasodilator therapy is used according to patient needs to maintain the mean arterial pressure at the appropriate level after adequate volume resuscitation. • Protein-calorie malnutrition is one of the main manifestations of hypermetabolism in shock. Early enteral nutrition is vital to decreasing morbidity from shock. Measures Specific to Type of Shock Cardiogenic Shock • The overall goal is to restore heart function and the balance between O2 supply and demand in the myocardium. 5 Copyright © 2023 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. • Definitive measures include angioplasty with stenting, emergency revascularization, and valve replacement. • Care involves hemodynamic monitoring, drug therapy (e.g., diuretics to reduce preload), and use of circulatory assist devices (e.g., intraaortic balloon pump, ventricular assist device). Hypovolemic Shock • The underlying principles of managing patients with hypovolemic shock focus on stopping the loss of fluid and restoring the circulating volume. Septic Shock • Patients in septic shock need large amounts of fluid replacement. The goal is to achieve a targeted response based on CVP, ScvO2, cardiac ultrasound, a focused physical assessment, fluid responsiveness, or other measures. • A fluid challenge technique (e.g., a minimum of 30 mL/kg of crystalloids) may be used and repeated until hemodynamic improvement (e.g., increase in MAP and/or CVP) is noted. • Vasopressor drug therapy may be added for a MAP that does not respond to initial fluid resuscitation. Vasopressin may be given to those refractory to vasopressor therapy. • IV corticosteroids are only recommended for patients who cannot maintain an adequate blood pressure (BP) with vasopressor therapy, despite fluid resuscitation. 6 Copyright © 2023 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. • Antibiotics are a critical component of therapy for patients with septic shock. They should be started after cultures (e.g., blood, urine) are obtained and within the first hour of severe sepsis or septic shock. Neurogenic Shock • The treatment of neurogenic shock is dependent on the cause. In spinal cord injury, general measures to promote spinal stability are initially used. • Treatment of hypotension and bradycardia involves the use of vasopressors and atropine, respectively. Fluids are given cautiously. The patient is monitored for hypothermia. Anaphylactic Shock • Epinephrine is the drug of choice to treat anaphylactic shock. • Maintaining the airway is critical. Endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy may be needed. • Aggressive fluid replacement, most often with crystalloids, is needed. Obstructive Shock • The main strategy in treating obstructive shock is early recognition and treatment to relieve or manage the obstruction. Nursing Management: Shock Nursing Assessment • The initial assessment focuses on assessing responsiveness and ABCs: airway, breathing, and circulation. 7 Copyright © 2023 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. • Further assessment focuses on the assessment of tissue perfusion and includes evaluation of trends in vital signs, peripheral pulses, level of consciousness, capillary refill, skin (e.g., temperature, color, moisture), and urine output. Planning • The overall goals for a patient in shock include (1) evidence of adequate tissue perfusion, (2) restoration of normal or baseline BP, (3) recovery of organ function, and (4) avoiding complications from prolonged states of hypoperfusion, and (5) preventing health care– associated complications of disease management and care. Nursing Implementation • Your role in shock involves (1) monitoring the patient’s ongoing physical and emotional status, (2) identifying trends to detect changes in the patient’s condition, (3) planning and implementing nursing interventions and therapy, (4) evaluating the patient’s response to therapy, (5) providing emotional support to the patient and caregiver, and (6) collaborating with other members of the health team to coordinate care. • The patient in shock requires frequent assessment of heart rate/rhythm, BP, CVP, SvO2, and pulmonary artery (PA) pressures or arterial pressure wave-form analysis for cardiac output (APCO); neurologic status; respiratory status, urine output, and temperature; capillary refill; skin for temperature, pallor, flushing, cyanosis, diaphoresis, or piloerection; and bowel sounds and abdominal distention, as well as prevention of health care-associated infections. 8 Copyright © 2023 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. • Rehabilitation of the patient who is recovering from shock includes correcting the precipitating cause, preventing or early treatment of complications, and teaching focused on disease management and/or prevention of recurrence based on initial cause of shock. SYSTEMIC INFLAMMATORY RESPONSE SYNDROME AND MULTIPLE ORGAN DYSFUNCTION SYNDROME • Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) is a systemic inflammatory response to a variety of insults, including infection (referred to as sepsis), ischemia, infarction, and injury. • SIRS is characterized by generalized inflammation in organs remote from the first insult. • SIRS can be triggered by mechanical tissue trauma (e.g., burns, crush injuries), abscess formation, ischemic or necrotic tissue (e.g., pancreatitis, myocardial infarction), microbial invasion, and global and regional perfusion deficits. • Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) is the failure of 2 or more organ systems in an acutely ill patient such that homeostasis cannot be maintained without intervention. It often results from SIRS. • The respiratory system is often the first system to show signs of dysfunction in SIRS and MODS, often ending in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). • Cardiovascular changes, neurologic dysfunction, acute kidney injury, DIC, GI dysfunction, and liver dysfunction are common. Nursing and Interprofessional Management: SIRS and MODS • The prognosis for the patient with MODS is poor. The most important goal is to prevent SIRS from progressing to MODS. 9 Copyright © 2023 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. • A critical part of your role is vigilant assessment and ongoing monitoring to detect early signs of deterioration or organ dysfunction. • Interprofessional care for patients with SIRS and MODS focuses on (1) prevention and treatment of infection, (2) maintaining tissue oxygenation, (3) nutritional and metabolic support, and (4) appropriate support of individual failing organs. 1 0 Copyright © 2023 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved.