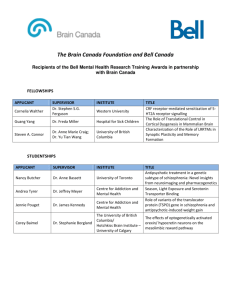

Author’s Accepted Manuscript Speech and language therapies to improve pragmatics and discourse skills in patients with schizophrenia Marilyne Joyal, Audrey Bonneau, Shirley Fecteau www.elsevier.com/locate/psychres PII: DOI: Reference: S0165-1781(15)30190-6 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.010 PSY9571 To appear in: Psychiatry Research Received date: 19 August 2015 Revised date: 3 January 2016 Accepted date: 3 April 2016 Cite this article as: Marilyne Joyal, Audrey Bonneau and Shirley Fecteau, Speech and language therapies to improve pragmatics and discourse skills in patients with schizophrenia, Psychiatry Research, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.010 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting galley proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. Speech and language therapies to improve pragmatics and discourse skills in patients with schizophrenia Marilyne Joyal, M. Sc. SLP*, Audrey Bonneau, M. Sc. SLP, Shirley Fecteau, Ph. D. Centre interdisciplinaire de recherche en réadaptation et en intégration sociale, 525, boul. WilfridHamel, bureau H-1312, Quebec, Quebec, Canada G1M 2S8 ; Centre de recherche de l’Institut universitaire en santé mentale de Québec, 2601, de la Canardière, Quebec, Quebec, CANADA G1J 2G3 ; Faculté de médecine, Université Laval, 1050, avenue de la Médecine, Quebec, Quebec, Canada G1V0A6 *Corresponding author. Marilyne Joyal, Postal address: 525, boul. Wilfrid-Hamel, bureau H-1312, Quebec city QC G1M 2S8, Tel.: 418 649-3735. Email: marilyne.joyal.1@ulaval.ca Abstract Individuals with schizophrenia display speech and language impairments that greatly impact their integration to the society. The aim of this systematic review was to identify the importance of speech and language therapy (SLT) as part of rehabilitation curriculums for patients with schizophrenia emphasizing on the speech and language abilities assessed, the therapy setting and the therapeutic approach. This article reviewed 18 studies testing the effects of language therapy or training in 433 adults diagnosed with schizophrenia. Results showed that 14 studies out of 18 lead to improvements in language and/or speech abilities. Most of these studies comprised pragmatic or expressive discursive skills being the only aim of the therapy or part of it. The therapy settings vary widely ranging from twice daily individual therapy to once weekly group therapy. The therapeutic approach was mainly operant conditioning. Although the evidence tends to show that certain areas of language are treatable through therapy, it remains difficult to state the type of approach that should be favoured and implemented to treat language impairments in schizophrenia. Keywords Psychiatry, rehabilitation, communication, speech-language pathology 1. Introduction Pragmatics is a major component of language referring to the use of language in context. It involves verbal, paralinguistic and nonverbal aspects of communication, such as the ability to introduce a topic of conversation, respect turn-taking, detect emotions in someone else voice and adopt appropriate body posture and facial expression according to the social context (Prutting & Kirchner, 1987). Pragmatics deficits are reflected in discourse skills, and more specifically in discourse coherence (i.e. continuity across adjacent utterances and in the overall meaning) (Ulatowska & Olness, 2007). Indeed, nonrespect of the topic and situation in which the conversation takes part make the discourse lacking of coherence. Pragmatics deficits are observed in many clinical populations such as individuals with schizophrenia (Haas et al., 2015), autism spectrum disorders (Simmons et al., 2014), specific language impairments (Mäkinen et al., 2014) and right brain damage (Sobhani-Rad et al., 2014). Since the beginning of the 20th century (Bleuler, 1950; Kraeplin, 1919), communication impairments, and more specifically in the areas of pragmatics and discourse understanding (Byrne et al., 1998; Haas et al., 2015; Meilijson et al., 2004; Pavy, 1968; Salavera et al., 2013; Tavano et al., 2008), have constantly been considered as an indicator of schizophrenia. Communication impairments in schizophrenia can be apparent both in oral production and comprehension (DeLisi, 2001). Some authors reported impaired pragmatic and discursive abilities in schizophrenia: low self-disclosure in conversation (Byrne et al., 1998), less information provided in narratives (Byrne et al., 1998; Tavano et al., 2008), difficulty to produce appropriate interpretations (Tavano et al., 2008), and deficits in proverb comprehension and use of less connectors in discourse (Haas et al. 2015). With the Pragmatic Protocol (Prutting & Kirchner, 1987), Meilijson et al. (2004) also identified 5 clusters of pragmatic deficits: topic, speech acts, turn-taking, lexical (e.g. conciseness, prosody) and non-verbal aspects. The authors formed three different profiles of inappropriateness according to the deficits exhibited: minimal impairment, lexical impairment and interactional impairment. Further, pragmatic deficits in schizophrenia have been associated with formal thought disorders (Salavera et al., 2013) and impairment in theory of mind (i.e. a difficulty in representing the emotional and intellectual state of mind of the interlocutor) (Brüne & Bodenstein, 2005; Mazza et al. 2007). It has also been suggested that pragmatic deficits are key features of schizophrenia (Tavano et al., 2008). In our current first-world reality, the slightest deficit can create a substantial handicap since communication and interpersonal skills are put forward and play a crucial role in social integration, 2 personal recognition, working purposes, etc. As stated by the Schizophrenia Society of Canada (2014), the reality underlying these impairments is that as many as 70 percent of people living with schizophrenia would like to be engaged in competitive employment, but fewer than 15 percent are actually employed. Social difficulties are one of the hallmarks. Communication impairments associated with a diagnostic of schizophrenia are hence a central issue to assess regarding any goal for optimizing their quality of life and functioning in society on both a personal and professional level. Speech and Language Therapy (SLT) comprises behavioral interventions addressing oral and written communication impairments and are provided by speech language pathologists and has been shown effective in various clinical populations of adults (Brady et al., 2012) and children (Law et al., 2003). These interventions entail direct training of linguistic behaviors and/or environmental adaptations to facilitate communication. They can be delivered within a functional approach when the aim is to improve communication during daily activities (LPAA Project Group, 2008). Other interventions might also be used for individuals with schizophrenia in order to improve language or speech, such as cognitive remediation, operant conditioning therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, integrated psychological therapy or general psychiatric rehabilitation. Cognitive remediation can be defined as an ‘intervention targeting cognitive deficit (attention, memory, executive function, social cognition, or meta cognition) using scientific principles of learning with the ultimate goal of improving functional outcomes’ (McGurk et al., 2013). Operant conditioning therapies implies the use of explicit and systematic reinforcement to a specified response in order to modify behavior (Keutzer, 1967). Cognitive behavioral therapy aims at promoting accurate and balanced thinking with the goal of producing changes in behavior (Farmer & Chapman, 2015). Integrated psychological therapy entails training in cognitive functions, social perception, verbal communication and social skills (Taksal et al., 2015). Psychiatric rehabilitation can also address speech and language deficits through individualized rehabilitative programs based on patient’s disabilities and strengths, including realistic goals and regular measures of progress (Gigantesco & Giuliani, 2011). The National Institute of Mental Health (2009) and the Schizophrenia Society of Canada (2014) along with the Canadian Psychiatric Association currently provides the population with information regarding language and social skills training for individuals with schizophrenia, taking place in different rehabilitation facilities and provided by social workers or occupational therapists. In both booklets, there is no mention of SLT involved in the rehabilitation process. This is in line with the fact 3 that few studies specifically examined the efficacy of SLT to treat language deficits in individuals with schizophrenia. Language deficits have recently been targeted in cognitive remediation programs, but SLT is not yet systematically part of a comprehensive intervention in schizophrenia. One reason is that pragmatic and discourse deficits might not always be the most preoccupying symptoms, in comparison with other symptoms such as hallucinations. However, considering that pragmatic deficits compromise the integration of individuals with schizophrenia, and that pragmatic deficits can be assessed and treated as part of SLT, it could be an appropriate approach to treat language deficits observed in individuals with schizophrenia. Furthermore, when adopting a mindset in which therapeutic care for individuals living with schizophrenia is specialized and complete, it comes obvious that the place of SLT in psychiatry is small and circumscribed. This hampers the diffusion of the clinical expertise and to a stronger degree, the recognition of SLT as a science based on scientifically proven data. However, in the recent years, projects have started to explore the potential development of SLT in adults with schizophrenia in hopes of legitimating SLT in adult psychiatry (Findlay, 2012). Through experimental designs, attempts have been made to answer a need for using and eventually developing standardized tests for this population (LeBar & Mahouet, 2011). The findings of the latter suggest that non-verbal communication, verbal perseverations, inference and deduction are areas that should be explored in therapy for schizophrenia. It is important to consider all fields of expertise that have previously tested language as a variable in studies as SLT is part of medical and rehabilitation facilities where science is supported by high degrees of evidence and the amount of required scientific data available is currently minimal. This is of capital importance especially when aiming at providing patients with the most accurate support possible based on an evidence-based practice. Due to the lack of evidence, there is currently no consensus on the most efficient language or communication therapy available for treating patients with schizophrenia (National Institute of Mental Health, 2009; Schizophrenia Society of Canada, 2014). This systematic review hence aims at identifying the importance of SLT as part of rehabilitation curriculums for patients with schizophrenia and addressing the various approaches used for therapies while providing an insight on the different conclusions reached by those studies. The main factors discussed to highlight which approaches might be beneficial are 1) the therapeutic approach of the studies reviewed; 2) speech and language abilities assessed; 3) the therapy setting. 4 2. Methods 2.1 Search strategy The search for articles included in this systematic review was used CINAHL and PubMED databases with no year restriction up to December 2015. Keywords used the following combination: ((schizophrenia) AND ((language) OR speech)) AND ((((therapy) OR intervention) OR training) OR remediation). We applied filters to identify relevant literature in English and examining humans. This search yielded to 1355 results. After removal of doubles, 1287 articles remained. 2.2 Selection criteria In a first phase of study selection, we excluded those abstracts (1) not reporting original data (e.g., reviews, meta-analyses), (2) not including subjects who were adults (older than 18 years of age) and diagnosed with schizophrenia, (3) not assessing speech or language component before and after therapy, and (4) not delivering behavioral intervention (i.e., pharmacotherapy) as therapy. From the 1287 articles found in the initial search, 1217 were excluded after title and abstract reading because they did not meet these inclusion criteria. Then 70 articles were full-text reviewed and 52 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. This selection resulted in 18 articles (see Figure 1 for the flowchart). Please insert Flowchart about here 3. Results Eighteen studies were retained for this systematic review. Together they included 433 adults diagnosed with schizophrenia: 326 subjects received language therapy or training and 107 subjects received control intervention. In the thirteen studies reporting the ratio of men and women, men were more represented with two exceptions, Mundt et al. (1995) with 60% of females and Allen et al. (1978) who conducted a case study with a woman. The number of subjects included in these studies varied between single cases studies (Allen et al., 1978; Foxx et al., 1988; Clegg et al., 2007) and studies with large sample size (e.g., 93 participants with schizophrenia; Ojeda et al., 2012). Details on these 18 studies 5 can be found in Table 1. Please insert Table 1 about here 3.1 Therapeutic approach The therapeutic approach that was the most represented for realising the interventions was based on operant conditioning (5 studies). The main goal of these five studies was to enhance communication. This approach led to improvement in pragmatic skills, discourse production or naming in these five studies (Allen et al., 1978; Baker, 1971; Cliff, 1974; Foxx et al., 1988; Hart et al., 1980). However, improvements were sometimes observed only for some participants (Cliff, 1974) or were not transferred in everyday life (Allen et al., 1978). Three studies (Hoffman & Satel, 1993; Kramer, 2001; Ryu et al., 2006) used so-called metacomprehension (explicit training on communication skills) or metalearning (self monitoring, self learning). Both approaches led to significant improvement in pragmatic skills or discourse production, whether the goal of the intervention was to improve communication (Hoffman & Satel, 1993; Kramer, 2001) or social abilities and clinical symptoms in a wider perspective (Ryu et al., 2006). Cognitive remediation was used in the three most recent studies, which aimed to improve cognitive functions in general (Man et al., 2012; Ojeda et al., 2012) or autobiographical memory (Blairy et al., 2008). Only Ojeda et al. (2012) found a significant improvement in language, specifically in phonological fluency. The remaining seven studies used different approaches (psychiatric rehabilitation, cognitive behavioral therapy, functional approach, integrated psychological therapy and vestibular stimulation) alone or combined to treat speech and/or language deficits in patients with schizophrenia. The efficacy of these various approaches remains unclear to treat speech and/or language deficits in this population. 3.2 Speech and language abilities assessed Among the eighteen studies analysed, twelve measured pragmatic skills and/or discourse as part of the therapy (see Table 1). Eleven of them reported significant changes in pragmatic skills and/or discourse, for at least some participants. The following skills have been treated and measured in several studies: discourse coherence, amount of speech, clarity, intelligibility, appropriateness and elaboration of responses. Clegg et al. (2007) and Kawabuko et al. (2007) targeted non-verbal aspects of pragmatics; an improvement was reported by Clegg et al. (2007). Within the twelve studies which assessed pragmatic skills and/or discourse, five conducted follow-up assessments after the last therapy session 6 ranging from 8 weeks to 2 years. Verbal fluency have been assessed in 3 studies, and improved in one of them (Ojeda et al., 2012). Naming have been assessed in four studies, and improved in two of them. Nevertheless, improvement in naming was not retained at one month follow-up (Kondel et al., 2006) and did not lead to improvement of verbal behavior in everyday life (Allen et al., 1978). The four studies that did not reach any significant changes in speech or language with therapy measured repetition, naming, comprehension, verbal or phonological fluency, and one measured pragmatics. We extracted quantitative data (Glass’s Delta) from six studies; the remaining twelve studies did not report means and standard deviations of performance before and after therapy or they were case studies so we could not calculate effect sizes. We considered that effect size values lower than 0.5 were not significant, values between 0.5 and 1 reflected small positive effects of therapy, and values between 1 and 2 were clinically relevant. We found clinically relevant improvement for discourse production (score of intelligibility, appropriateness and elaboration of responses) (Baker, 1971), small positive effects for phonological fluency (Ojeda et al., 2012) and naming (Kondel et al., 2006), but no significant changes for sentence comprehension, repetition and naming (Man et al., 2012), verbal and semantic fluency (Blairy et al., 2008; Ojeda et al., 2012), and pragmatic non-verbal skills (Kawabuko et al., 2007). 3.3 Therapy setting Individual therapy was preferred by researchers in fourteen studies, whereas the four other studies favoured group therapy. Eleven out of fourteen studies using individual therapies led to improvements, and three out of the four group therapies also induced to improvements. 4. Discussion The main objective of this systematic review was to identify the importance of SLT as part of rehabilitation curriculums for patients with schizophrenia, as well as characterize interventions that seems to be beneficial to treat speech and language impairments highlighting 1) the therapeutic approach; 2) the speech and language abilities assessed, and 4) the therapy setting. 4.1 Therapeutic approach 7 Operant conditioning was the most favoured approach in our reviewed articles. Operant conditioning has been documented and used in psychology for decades, it is not surprising that this was also the preferred approach used by researchers in this last decade. As new theories emerged, approaches became more eclectic and this shows in the sample of studies used in this review. Cognitive remediation also seems to be privileged in recent years. There was no clear evidence from the studies reviewed here that this approach leads to significant improvement in speech or language, and changes in social cognition or social skills appear inconsistent. Social cognition was improved with cognitive remediation (Mendella et al. 2015) but not when cognitive remediation was combined with a program of social skills-training (Kurtz et al. 2015) or with an integrated supported employment (Au et al., 2015). Efficiency of cognitive remediation on speech and language abilities may vary according to its aim: the one specifically targeting communication may lead to better results than the one targeting cognitive functions in general. Finally, social skills-training seems to reduce social impairments in individuals with schizophrenia (Bellack, 2004), which may also improve pragmatics and discourse skills in these individuals. Unfortunately it is not possible to connect articles to each other based on similar underlying theories. As stated by Kramer et al. (2001) “despite the significance of the language of patients who are mentally ill, there are no satisfactory descriptions of their language and as a consequence no published hypothesis driven therapy programmes to remediate their language”. Further progress of a unified conceptual model would greatly contribute to better describe speech and language impairments, as well as to develop SLT interventions specifically for patients with schizophrenia. 4.2 Speech and language abilities assessed This review indicates that pragmatics and discourse are skills that can be trained in patients with schizophrenia and that this training can be retained over time. From the eighteen studies reviewed here, twelve targeted pragmatic or discursive skills that are impaired in individuals with schizophrenia, and eleven of them showed an improvement. Five of these twelve studies also assessed pragmatics and/or discourse skills with follow up assessments. The all reported improvements that were maintained at follow-up assessment ranging from eight weeks to two years. We could not calculate effect sizes for most of these studies, it is thus difficult to compare the efficiency of these therapies on language or speech skills. These findings are coherent with current knowledge on language and speech impairments in patients with schizophrenia. Impairments in pragmatic rules along with general cognitive deficits 8 greatly affect the construction of a coherent discourse (Marini et al., 2008). However, one study targeted pragmatics with therapy and reported negative findings (Kawakubo et al., 2007). These results might be explained by the choice of the therapy, social skills training based on a medication selfmanagement module (Liberman & Martin, 2002), a therapy that might not be specific enough to teach and train pragmatics. Studies targeting communication impairments as a whole and including formal testing of language in areas known to be less affected in patients with schizophrenia reported that therapy did not lead to significant changes (Lewis et al., 2003; Man et al., 2012). These approaches indicate that skills such as naming, repetition, and verbal comprehension may not be sufficiently impaired to be targeted in therapies and/or therapies have yet to be developed for this clinical population. It is also possible that some deficits would be endophenotypes of schizophrenia, these deficits being more resistant to treatment. For instance, semantic verbal fluency impairments remain unchanged in individuals with schizophrenia despite treatment (Szöke et al., 2008) and appear to discriminate responders from non-responders to a pharmacological treatment (Stip et al., 1999). In sum, pragmatic and discourse skills can be improved with therapy in patients with schizophrenia. However, only nine studies out of eighteen measured speech and language skills with follow-up assessments. It is thus difficult to conclude on the long-term benefits of an intervention targeting speech and language deficits for patients with schizophrenia. Future studies should further test retention of gained skills over time. 4.3 Therapy setting Both individual and group therapies led to improvements or no changes in the studies reviewed here. Most studies preferred an individual setting for therapy, however this choice did not seem to be based on previous evidence. This trend of favouring individual therapy is common in current rehabilitation setting. It should also be noted that some studies delivering group therapy targeted hospitalized patients (Ojeda et al., 2012; Ryu et al., 2006) who were likely more severely impaired than outpatients. In terms of duration of therapeutic sessions and frequencies, they greatly differed across studies. Duration of therapies ranged from 15 days to 2 years and each lasted from 15 to 90 minutes. Frequency of the sessions delivered went from twice a day to once a week. It seems that shorter durations with higher frequencies such as in Cliff (1974) that reported beneficial changes using a similar approach may be privileged over longer durations with spaced times. This is also in line with other field such as in aphasia (Godecke et al., 2012) and children with language difficulties (Barratt et al., 1992), in which 9 the subjects receiving intensive individual therapy, 5 and 4 times a week respectively, had better improvement on communication outcomes than those receiving individual therapy once a week. Unfortunately, duration of therapy was not reported in all the studies reviewed here. 4.4 Limitations and future directions This systematic review has limitations to be considered. The number of participants was limited, participants were diagnosed based on different editions of the DSM and gender ratio was not representative of the general population of schizophrenia. In studies with smaller samples, interindividual variations might account for a high percentage of the success or failure of the therapies tested taking in account also intrinsic motivations of patients. This is why using larger sample sizes as it was done by Ojeda et al. (2012) who tested 93 patients are encouraged in order to formulate broader generalizations on the efficiency of these treatments. This is especially important when considering the various disorders recognized by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5; APA, 2013) and the different presentations of speech and language impairments due to illness ranging from muteness (Baker, 1971) to lengthy utterances (Kramer, 2001). For instance, the 5 subtypes of schizophrenia were removed in the 5th edition due to limited diagnostic stability, low reliability, and poor validity. Moreover, five studies included in this review did not conduct statistical analyses as they were case studies. Also, gender ratio in the reviewed articles was not fully representative of the general population. In the eighteen studies, men were always more represented than women with two exceptions. However, as reported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (2009), the proportion of male and female living with a diagnostic of schizophrenia around the world is of 50/50. Recruitment processes greatly varied across studies. For instance, Ryu et al. (2006) systematically offered therapy to an entire facility dedicated to patients with schizophrenia, whereas Man et al. (2012) used randomized, controlled, double-blind selection and treatment of patients with schizophrenia. It is thus difficult to generalize findings from this work to the general population of adults with schizophrenia. Moreover, methodological aspects of the studies reviewed vary widely (e.g. therapy settings, length and intensity of interventions, speech and language abilities that are trained) which made the results difficult to compare and interpret. Consequently, despite improved pragmatic and discourse skills with therapy, the strength of evidence should be considered with precaution and the need for more studies with follow-ups remains. In future studies, it would be interesting to investigate whether improved language and communication 10 skills in patients with schizophrenia enhances their quality of life and/or reduces frequency and severity of positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Hoffman and Satel (1993) found reduced severity or frequency of auditory hallucinations in patients who improved their language abilities following SLT. Nevertheless, most studies reviewed here did not measure the impact of the intervention targeting language and communication on patient’s quality of life with standardized questionnaires. In accordance to the strength of the evidence presented here, therapies should focus on pragmatic skills and discourse production should be the areas where on. Improved pragmatic and discourse skills can certainly help patients in social reintegration and quality of life. There is however much work to be done. Moreover, we believe that the place of the expertise of SLT is yet to be made in schizophrenia as most studies reviewed here appear to come from psychology (e.g. studies using operant conditioning) and neuropsychology (e.g. studies using cognitive remediation). Best case practices and rigorous scientific studies are rare in a young and emerging discipline such as SLT. The field of SLT can contribute at characterizing speech and language impairments across life span of patients with schizophrenia in a detailed manner, as well as identifying and developing efficient approaches to treat speech and language impairments with evidence based data. Existing multidisciplinary service offered to these patients might consider including SLT speciality in the future, as well as strong incentives within the SLT field should be put forward in order to develop standardized tests for evaluating speech and language skills of patients with schizophrenia. Role of the Funding Source M. Joyal was supported by a Centre Interdisciplinaire de Recherche en Réadaptation et Intégration Sociale PhD scholarship. This work was supported by the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada grant (402629-2011) and Canada Research Chair in Cognitive Neuroplasticity to S. Fecteau. Acknowledgments None References Allen, D.J., Antonitis, J.J., Magaro, P.A., 1978. Reinforcing effects of prerecorded words and delayed speech feedback on the verbal behavior of a neologistic schizophrenic. Percept. Motor Skill. 46, 11 343-346. American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. Au, D.W.H., Tsang, H.W.H., So, W.W.Y., Bell, M.D., Cheung, V., Yiu, M.G.C., Tam, K.L., Lee, G.T.H., 2015. Effects of integrated supported employment plus cognitive remediation training for people with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders. Schizophr. Res. 166, 297-303. Bailey, D.M., 1978. The effects of vestibular stimulation on verbalization in chronic schizophrenics. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 32(7), 445-450. Baker, R.,1971. The use of operant conditioning to reinstate speech in mute schizophrenics. Behav. Res. Ther. 9(4), 329-336. Barratt, J., Littlejohns, P., Thompson, J., 1992. Trial of intensive compared with weekly speech therapy in preschool children. Arch. Dis. Child. 67(1), 106–108. Bellack, A.S., 2004. Skills training for people with severe mental illness. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 27(4), 375-391. Blairy, S., Neumann, A., Nutthals, F., Pierret, L., Collet, D., Philippot, P., 2008. Improvements in autobiographical memory in schizophrenia patients after a cognitive intervention: A preliminary study. Psychopathology. 41, 388-396. Bleuler, E., 1950. Dementia praecox : On the group of schizophrenias (J. Zimkin, Trans.). International Universities Press, NY. (First published 1911). Brady, M.C., Kelly, H., Godwin, J., Enderby, P., 2012. Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke. Cochrane Db. Syst. Rev. 5, CD000425. Brüne, M., Bodenstein, L., 2005. Proverb comprehension reconsidered-‘theory of mind’ and the pragmatic use of language in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 75, 233-239. Byrne, M.E., Crowe, T.A., Griffin, P.S., 1998. Pragmatic language behaviors of adults diagnosed with chronic schizophrenia. Psychol. Rep. 83, 835-846. Canadian Psychiatry Association, Schizophrenia Society of Canada, 2007. Schizophrenia : The Journey to Recovery (A consumer and Family Guide to Assessement and Treatment). Retrieved December 14th, 2015, from: http://www.schizophrenia.ca/journey_to_recovery.php Clegg, J., Brumfitt, S., Parks R.W., Woodruff P.W.R., 2007. Speech and language therapy intervention in schizophrenia – a case study. Int. J. Lang. Comm. Dis. 42(S1), 81-101. Cliff, M.J., 1974. Reinstatement on speech in mute schizpohrenics by operant conditioning. Acta. Psychiat. Scand. 50(6), 577-585. 12 DeLisi, L.E., 2001. Speech disorder in schizophrenia: Review of literature and exploration of its relation to uniquely human capacity for language. Schizophrenia Bull. 27(3), 481-496. Farmer, R.F., Chapman, A.L., 2015. Behavioral interventions in cognitive behavior therapy: practical guidance for putting theory into action, second ed. Washington, DC. Findlay, C., 2012. Intérêt de la prise en charge orthophonique des personnes souffrant de schizophrénie, dans une perspective de réhabilitation psychosociale: Étude de cas. Université de Nancy. Foxx, R.M., McMorrow, M.J., Davis, I.A., Bittle, R.G., 1988. Replacing a chronic schizophrenic man’s delusional speech with stimulus appropriate responses. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psy. 19, 43-50. Gigantesco, A., Giuliani, M., 2011. Quality of life in mental health services with a focus on psychiatric rehabilitation practice. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanità. 47(4), 363-372. Godecke, E., Hird, K., Lalor, E.E., Rai, T., Phillips, M. R., 2012. Very early poststroke aphasia therapy: A pilot randomized controlled efficacy trial. Int. J. Stroke. 7(8), 635–644. Haas, M.H., Chance, S.A., Cram, D.F., Crow, T.J., Aslan, L., Hage, S., 2015. Evidence of pragmatic impairments in speech and proverb interpretation in schizophrenia. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 44, 469-483. Hart, B.B., 1980. Speech modification in near-mute schizophrenics. Brit. J. Psychol. 71(2), 241-246. Hoffman, R.E., Satel, S.L., 1993. Language therapy for patients with persistent ‘voices’. Brit. J. Psychiat. 162, 755-758. Kawakubo, Y., Kamio, S., Nose, T., Iwanami, A., Nakagome, K., Fukuda, M., 2007. Phonetic mismatch negativity predicts social skills acquisition in schizophrenia. Psychiat. Res. 152, 261265. Keutzer, C.S., 1967. Use of therapy time as a reinforcer : application of operant conditioning techniques within a traditional psychotherapy context. Behav. Res. Ther. 5, 367-370. Kondel, T., Hirsch, S., Laws, K., 2006. Name relearning in elderly patients with schizophrenia: Episodic and temporary, not semantic and permanent. Cogn. Neuropsychiatry. 11(1), 1-12. Kraeplin, E., 1919. Dementia praecox and paraphrenia. Robert E. Krieger, New York. Kramer, S. Bryan, K., Frith, C.D., 2001. Mental illness and communication. Int. J. Lang. Comm. Dis. 36(137-2). Kurtz, M.M., Mueser, K.T., Thime, W.R., Corbera, S., Wexler, B.E., 2015. Social skills training and computer-assisted cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 162, 35-41. Law, J., Garrett, Z., Nye, C., 2003. Speech and language therapy interventions for children with 13 primary speech and language delay or disorder. Cochrane Db. Syst. Rev. 3, CD004110. LeBar, M., Mahouet, C., 2011. Schizophrénie et orthophonie: Évaluation des compétences pragmatiques, par le protocole MEC, de patients adultes schizophrènes. Lille. Lewis, L., Unkefer, E.P., O’Neal, S.K., Crith, C.J., Fultz, J., 2003. Cognitive rehabilitation with patients having persistent, severe psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 26, 325-331. Liberman, R., Martin, T., 2002. Social skills training for people with serious mental illness. Retrieved August 15th, 2015, from : http://www.bhrm.org/guidelines/mhguidelines.htm LPAA Project Group, 2008. Life-participation approach to aphasia: A statement of values for the future, in Chapey, R. (Ed.), Language intervention strategies in aphasia and related neurogenic communication disorders (5th ed.). Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp. 279-289. Mäkinen, L., Loukusa, S., Laukkanen, P., Leinonen, E., Kunnari, S., 2014. Linguistic and pragmatic aspects of narration in Finnish typically developing children and children with specific language impairment. Clin. Linguist. Phonet. 28(6), 413-427. Man, D.W., Law, K.M., Chung, R.C., 2012. Cognitive Training for Hong Kong Chinese with schizophrenia in vocational rehabilitation. Hong Kong Med. J. 18(6), 18-22. Marini, A., Spoletini, I., Rubino, I.A., Ciuffa, M., Bria, P., Martinotti, G., 2008. The language of schizophrenia : An analysis of micro and macrolinguistic habilities and their neuropsychological correlates. Schizophr. Res. 105, 144-155. Mazza, M., Di Michele, V., Pollice, R., Roncone, R., Casacchia, M., 2007. Pragmatic language and theory of mind deficits in people with schizophrenia and their relatives. Psychopathology. 708, 110. McGurk, S.R., Mueser, K.T., Cicerone, K.D., Silverstein, S.M., Myers, R., Bell, M.D., Covell, N.H., Drake, R.E., Medalia, A., Bellack, A.S., Essock, S.M., 2013. Mental health system funding of cognitive enhancement interventions for schizophrenia: Summary and update of the New York office of mental health expert panel and stakeholder meeting. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 36(3), 133145. McPherson, F.M., Cockram, L.L., Grimes, J., Fraser, D., Presly, A.S., 1979. The restoration of one aspect of communication in chronic schizophrenic patients. Health. Bull. (Edinb). 37(5), 227-231. Meilijison, S.R., Kasher, A., Elizur, A., 2004. Language performance in chronic schizophrenia: a pragmatic approach. J. Speech Hear. Res. 47(3), 695-713. Mendella, P.D., Burton, C.Z., Tasca, G.A., Roy, P., St. Louis, L., Twamley, E.W., 2015. Compensatory cognitive training for people with first-episode schizophrenia: Results from a pilot randomized 14 controlled trial. Schizophr. Res. 162, 108-111. Mundt, C., Barnett, W., Witt, G., 1995. The core of negative symptoms in schizophrenia: affect of cognitive deficiency? Psychopathology. 28(1), 46-54. National Institute of Mental Health, 2009. Schizophrenia. Retrieved August 4th, 2015, from: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/schizophrenia/index.shtml Ojeda, M., Peña, J., Sánchez, P., Bengoetxea, E., Elizagárate, E., Ezcurra, J., Gutiérrez, G., 2012. Efficiency of cognitive rehabilitation with REHACOP in chronic treatment resistant Hispanic patients. NeuroRehabilitation. 30, 65-74. Pavy, H., 1968. Verbal behavior in schizophrenia : A review of recent studies. Psychol. Bull. 70, 164178. Prutting, C.A., Kirchner, D.M., 1987. A clinical appraisal of the pragmatic aspects of language. J. Speech Hear. Disord. 52, 105-119. Ryu, Y., Mizuno, M., Sakuma, K, Munakata, S., Takebayashi, T., Murakami, M., 2006. Deinstitutionalisation of long-stay patients with schizophrenia: the 2-year social and clinical outcome of a comprehensive program in Japan. Aust. Nz. J. Psychiat. 40(5), 462-470. Salavera, C., Puyuelo, M., Antoñanzas, J.L., Teruel, P., 2013. Semantics, pragmatics, and formal thought disorders in people with schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 9, 177-183. Schizophrenia Society of Canada, 2014. Learn More About Schizophrenia. Retrieved July 21st, 2015, from : http://www.schizophrenia.ca/learn_more_about_schizophrenia.php Simmons, E.S., Paul, R., Volkmar, F., 2014. Assessing pragmatic language in autism spectrum disorder : The Yale in vivo pragmatic protocol. J. Speech Lang. Hear. R. 57, 2162-2173. Sobhani-Rad, D., Ghorbani, A., Ashayeri, H., Jalaei, S., Mahmoodi-Bakhtiari, B., 2014. The assessment of pragmatics in Iranian patients with right brain damage. Iran J. Neurol. 13(2), 8387. Stip, E., Lussier, I., Ngan, E., Mendrek, A., Liddle, P., 1999. Discriminant cognitive factors in responder and non-responder patients with schizophrenia. Eur. Psychiatry. 14, 442-450. Szöke, A., Trandafir, A., Dupont, M.E., Méary, A., Schürhoff, F., Leboyer, M., 2008. Longitudinal studies of cognition in schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry. 192, 248-257. Taksal, A., Sudhir, P.M., Janakiprasad, K.K., Viswanath, D., Thirthalli, J., 2015. Feasibility and effectiveness of the Integrated Psychological Therapy (IPT) in patients with schizophrenia: a preliminary investigation from India. Asian J. Psychiatr. 17, 78-84. Tavano, A., Sponda, S., Fabbro, F., Perlini, C., Rambaldelli, G., Ferro, A., Cerruti, S., Tansella, M., 15 Brambilla, P., 2008. Specific linguistic and pragmatic deficits in Italian patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 102, 53-62. Ulatowska, H.K., Olness, G.S., 2007. Pragmatics in discourse performance : Insights from aphasiology. Semin. Speech Lang. 28(2), 148-157. Figure 1. Flowchart of the study selection process. Table 1. Summaries of the studies investigating the effects of therapy or training on speech and language abilities in adults with schizophrenia. *mo/mos, month/months; wks, weeks; yr/yrs, year/years. Therapeutic approach Speech and language abilities assessed Therapy setting N of subjects Male sex ratio Followup measur e Results Effect size (Glass’s delta) Man et al. (2012) Cognitive training for Hong Kong Chinese with schizophrenia in vocational rehabilitation. 80 (includin individua g 30 N/A 3 mos negative 0.40 l control patients) Ojeda et al. (2012) Efficiency of cognitive rehabilitation with REHACOP in chronic treatment resistant Hispanic patients. phonologica 93 l fluency : semantic, improved cognitive (includin 0.9 phonological group 78% no phonological remediation g 46 semantic fluency fluency control fluency : patients) 0.48 Blairy et al. (2008) Improvements in autobiographical memory in schizophrenia patients after a cognitive intervention cognitive remediation combined with 27 principles of (includin cognitive verbal fluency group g 12 53 % 3 mos negative -0.05 behavioural control therapy patients) (autobiographical memory intervention) cognitive remediation (errorless training) sentence comprehension , repetition, naming Clegg et al. (2007) Speech and language therapy intervention in schizophrenia- a case study. 16 combination of cognitive behavioral therapy (desensibilisation) and functional approach (less structured conversations) repetition, naming, word association, reading comprehension , discourse comprehension , discourse production (selfdescription, use of emotional words), pragmatics (eye contact, facial expression) individua l 1 100 % no improved discourse production and pragmatics* (negative attitude to communicatio n remained unchanged) N/A Kawakubo et al. (2007) Phonetic mismatch negativity predicts social skills acquisition in schizophrenia. psychiatric rehabilitation (medication selfmanagement module of a social skills training program) pragmatic skills (eye contact, facial expression, voice loudness, voice tone, maintaining conversation, fluency of conversation, clarity of message, social validity of the interaction and goal attainment) individua l 13 69% no negative 0.07 Kondel et al. (2006) Name relearning in elderly patients with schizophrenia : Episodic and temporary, not semantic and permanent name relearning (naming with repetition of good answers) naming individua l 10 N/A 1 mo improved naming but not 0.53 maintained at follow-up Ryu et al. (2006) Deinstitutionalization of long-stay patients with schizophrenia- the 2-year social and clinical outcome of a comprehensive intervention program in Japan. 17 metacomprehensio n (explicit training on communication skills) pragmatic skills/discourse production (speech skills : amount and initiation of speech, disturbed speech : speech sense and clarity) group 60 63% 2 yrs improved speech skills and disturbed speech scores N/A Lewis et al. (2003) Cognitive rehabilitation with patients having persistent, severe psychiatric disabilities. Integrated Psychological Therapy phonological fluency, verbal comprehension individua l 38 N/A 3 mos negative N/A no improved discourse production (more essential frames, no more irrelevant frames)* N/A Kramer (2001) Mental illness and communication metalearning (self monitoring and self learning) discourse production (macrostructur e of narrative discourse : inclusion of essential frames) individua l 2 100 % Mundt et al. (1995) The core of negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: Affect or Cognitive Deficiency? psychiatric rehabilitation discourse production (coherence) individua l 25 40% no improved discourse production N/A Hoffman & Satel (1993) Language therapy for schizophrenic patients with persistent 'voices'. qualitative improvements prosody, in a range of combination of semantic, individua 100 language metacomprehensio discourse 4 no N/A l % exercises n and metalearning production, (including comprehension coherence of discourse)* Foxx et al. (1988) Replacing a chronic schizophrenic man's delusional speech with stimulus appropriate responses. 18 operant conditioning (errorless training) pragmatic skills (connectedness of responses and contextual appropriateness ) individua l 1 100 % 8 wks 15 mos improved pragmatic skills* N/A no greater improvements in discourse production after modelling and operant conditioning N/A Hart et al. (1980) Speech modification in near-mute schizophrenics. modelling and operant conditioning (reinforcements) or modelling only discourse production (mean number of words produced) individua l 12 (includin g4 control patients) 100 % McPherson et al. (1979) The restoration of one aspect of communication in chronic schizophrenic patients improved number of words (results confounded at individua 21 71% 24 mos follow-up N/A l because of other treatment programmes) Allen et al. (1978) Reinforcing effects of prerecorded words and delayed speech feedback on the verbal behaviour of a neologistic schizophrenic improved operant naming after conditioning both kinds of (reinforcement reinforcement with singly individua *, no naming 1 0% No N/A presented l remarkable prerecorded words improvement or delayed speech of verbal feedback) behaviour in everyday life treatment based on behavioural principles, employed instruction, verbal prompting and social reinforcement discourse production (number of words in responses and spontaneous speech) Bailey (1978) The effects of vestibular stimulation on verbalization in chronic schizophrenics vestibular stimulation (sensorystimulating activities designed to promote sensory integration) discourse production (speed of responses, number of words used, relevance of responses) group 14 (includin g7 control patients) N/A No negative for speed and number of words, improvement for relevance of responses N/A Cliff (1974) Reinstatement of speech in mute schizophrenics by operant conditioning. 19 operant conditioning (reinforcements) discourse production (intelligibility, appropriateness and elaboration of responses) individua l 13 77% 1 yr improved discourse production for 6 subjects N/A Baker (1971) The use of operant conditioning to reinstate speech in mute schizophrenics. discourse production operant (intelligibility, conditioning appropriateness (reinforcements) and elaboration of responses) * Not statistically tested individua l 18 (includin g8 control patients) N/A 1 yr improved discourse production 1.43 Highlights Pragmatic and discourse skills can be improved in people with schizophrenia. It remains difficult to state the type of approach that should be favoured. The expertise of speech and language therapy is yet to be made in schizophrenia. Articles identified through database searching n = 1287 articles (after removal of doubles) Exclusion criteria (n = 1217) : 1- Not reporting original data 2- Not including subjects who were adults and diagnosed with schizophrenia 3- Not assessing speech or language component in a systematic way before and after therapy 4- Not delivering behavioural intervention as therapy Studies scanned for subsequent inclusion : n = 70 articles Subsequently excluded studies (n = 52) : 1- Studies meeting the exclusion criteria 2- Not describing sufficiently the methodology 3- Gathering people with different mental illnesses in the same experimental groups Eligible articles : n = 18 articles 20