Does It Make a Difference?

Evaluating Professional Development

Using five critical levels of

evaluation, you can improve

your scbool's professional

development p1'Og ram,

But be sure to start with the

desb'ed result-improved

student outcomes,

dllCiltors have long considered

evaluation of professional development

professional development to

programs more import3m than ever.

be their right-something

TmdirionaUy, educators haven't paid

much attention to evaluating their

E

they deserve as dedicated and

hardwo rking individuals. But

Icgislmors and policymakers have

recently begun to question that right. As

ed ucation budgets grow tight, they look

at wh.tt schools spe nd on professional

development and w:mt to know, Does

the investment yield tangible payoffs or

Thomas R. Guskey

could that money be spent i.n better

ways? Stich questions make effective

professional development effon5. Many

consider evalwuion a costly, timeconsuming process thai diverts attention from more imporulnt ilctivities such

as pia ruling, implementation, and

follo w ·up, Others feel they L,ck the skill

and e.xpenise to become involved in

rigorous evaluations; as a result , they

either neglect eval uation issues

completely or kave them to

"cv;lluation experts. "

Good evaluations don 't have

to be complicated. They

simply require thoughtful

p lanning, the ability to ask

good questio ns, and a basic

understanding of how to find

valid answers. \Vhat 's more ,

they can provide meaningful

info nnation that you CUl use to

make thoughtful, responsible

decisions about professional

development processes and

effects.

What Is Evaluation?

1.11 simplest terms, evaluatio n is

"the systematic investigation of

merit or worth "Ooint Com·

mjttee on Standards for Educa·

tional Evaluation, 1994, p. 3).

Systematic implies a focliseu ,

tho ughtful , and intentional

process. \Ve conduct evalua·

tions fo r clear reasons and with

explidt intent. In vestigation

refers [Q the collection :md

analysis of pertinent info nna·

tion through appropriate

methods and tec hniques. M erit

or worth denotes appraisal and judgment. We use evaluations to determine

the value of something-to help answer

Stich questions as, Is this program or

activity achieving its intended results? Is

it bener th:U1 what was done in the

past? Is it bener than another,

competing actiVity? Is it worth the

costs?

Some educators understand the

impo rtance o.f evaluation fo r event·

driven professional development activities, such as workshops and seminars,

but fo rget the w ide Iilnge of less formal,

o ngoing, job-embedded professional

development activities-study groups,

action research, coUaborat.ive planning,

curric ulum developme nt, structured

observ:ltions, pee.r coaching, mentoring,

and so o n. But regardleSS of its foml ,

professional development sho uld be a

purposeful endeavor. Through evalualio n, YOll can detenninc whethe r these

activities arc achieving their plltJ>oses.

46

EOU C ATIONAI-

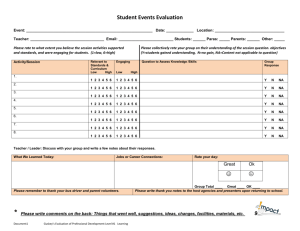

time was well spent? Did the

material make sense to the m?

\Vere the activities well

planned and meaningful? \Vas

the leader knowledgeable and

helpful? Did the participants

fmd the infonnatio n useful ?

Impo rtant questions fo r

professional deve lop ment

workshops and seminars also

indude, Was the coffee hot and

ready o n time? \Vas the room at

the right temperdtllre? Were

the chairs comfortable ? To

some , questions such as these

may seem silly and inco nse·

quential. But experienced

professional developers know

the impo rtance of ~m en d ing to

these b'ls1C human needs.

Information o n participants'

reactions is generally gathered

through q ucslioIlnai.res handed

out at the clld of a sessio n or

activity. These questionnaires

typically include a combination

of rating·scale items and open·

ended response questions that

<= allow participants to make

personal comments. Because of

the general nature of thjs infor·

mation, many o rganizations use the

same questionnaire for all their profc.s·

sional development activities.

Some educators refer to these

meas ures of partidpants' reactio ns as

"happiness quotients," insisting that

they reveal o nly the entenainment value

of an activity, nor its q uality or worth.

But me:lsuring participants' initial satis-faction with the experience can help

you improve rhe design and delivery of

programs o r activities in valid ways.

,t

!

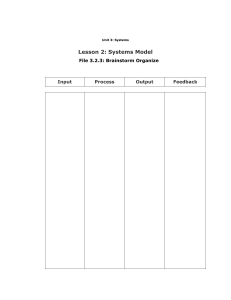

Critical Levels of Professiona l

Development Evaluation

Effective professional development evaluatio ns require the colJection and analysis of the five criticallevcls of informa·

tion shown in Figure 1 (Guskey, 2000a).

With e~lch succeeding level, the process

of gat hering eval uation info rmati o n gets

a bit more complex. And bectllse each

level builds on those thaI come before,

success at one level is usually necessary

for success at higher levels.

Level l: Particip(ll1ts ' Re(lclio7ls

The first level of evalua tion looks at

participants' reactions to the profes-sio nal development experience.. This is

the most common form of professional

deve lo pme nt evaluations, and the

easiest type of infomlation to gather and

imalyzc.

At Levell , you address questions

focusing on whethe r or nOI panicipanrs

liked the experience. Did they feel their

LI! .... nER ,!, III1' / MAR C Il 2002

Level 2: p (lrUcipallts ' Learnillg

In additio n to liking their professional

development experience, we also ho pe

that panicipams learn something from

it. Level 2 focuses on measuring the

knowledge and skills that panicipants

gained . Depending o n lhe goals of the

program o r activity, this can involve

anything from a pencil-and-paper assess-ment (Can participants desc ribe the

c rucial attributes of mastery learning

and give examples of how these might

be applied in typical classroom situalions?) [0 a simuJarion or full-scale skill

demonstration (presented with a variety

of classroom conflicts, can participants

diagnose each situation and then

prescribe and carry Ollt a fair and workable solution?). You can also use oral

personal reflections or portfolios that

participants assemble to docuOlem their

learning.

Although you can usually gather Level

2 evaluation information at the completion of a professional development

activity, it requires more than a standardized form. Measures must show

attainment of specific learning

goals. This means that indicators

of successful learning need to be

omlined before activities begin.

You can use rnjs infomJation as a

basis for improving the content,

format, and organi7..ation of the

program or activities.

I Traditionally, educators

I

haven't paid much attention to

evaluating their professional

development efforts.

The lack of positive results in this

case doesn' t reflect poor training or

inadequate learning, but rather organization policies that undermine implementation efforts. Problems at Level 3 have

essential1y canceled the gains made at

Levels I and 2 (Spa rks & Hirsh, 1997).

Stich as these can playa large part in

determining the success of any professional development effort.

Gathering information at Level 3 is

generaUy more compHcatcd than at

previous levels. Procedures differ

depending on the goals of the program

or actiVity. They may involve analyzing

district or school records, examining

the minutes from follOW-Up meetings,

administering questionnaires, and interviewing participants and school administrators. You can use thjs information

not only to document and improve

organization support but also to inform

future change initiatives.

Level 3: OrgllPlizatioll

Support arId Cha1lge

At Level 3, the focus shifts to the

organization. Lack of organization support and c hange can

sabotage any professional developmem effort, even when all the

individual aspects of professional

development are done right.

Suppose, for example, that

sever.:t1 secondary school educators partidpate in il professio nal

development program on cooper-dtive leaming. TIley gain a

thorough tmderstanding of the

theory and develop a variety of classroom activities based on cooperative

learning principles. Following their

tr.:lining, they try to implement these

activities in schools where students are

graded ~ on the curve"-according to

their relative standing amo ng classmares-and great importance is

attadled to selecting the c1'ISS valedictorian. Org.1Jli7..ation policies :md practices

such as these make learning highly

competitive and wiU thwart the most

va.Uam efforts to have SlUdents cooperate and help one another learn

(G uskey,2000b).

I

i•

That's why professional development

eV:lluations must include inform'ltion on

organization suppOrt and ch:mge.

At Level 3, you need to focus on

questions about the organii". ation characteristics and attributes necessary for

success. Did the professional development activities promote changes mat

were aligned with the mission of the

school and district? Were changes at me

individual level encouraged and

supported al all levels? Were sufficient

resources made avaiJable, including

time for sharing :Uld reflection? Were

successes recogni7..ed and shared? Issues

Level 4: Pllrticipallts #Use of

New Kllowledge a"d Skills

At Level -4 we ask, Did the new knowl-

edge and skiUs that partidpams leamed

make a difference in their professional

practice? Tbe key to gathering relevant

information at dtis level rests in specifying c.lear indicators of both the degree

and the quality of implementation.

UnUke Levels 1 and 2, this infoml:ltion

cannot be gathered at the end of a

professional development session.

Enough time must pass to allow panicipants to adapt the new ideas and practices to [heir settings, Beclllse imple-

A SSOC IATIO N 110R SU P E RVISIO N AND CURRICU I.U ... I OeV E I.O I' M EN T

47

FI

GU

R f

1

Five Levels of Professional Deve l opmen t Evalu ation

Evaluation level

What Questions Are Addressed?

How Will Information

Be Gathered?

What Is Measured or

Assessed?

1. Participants'

Reactions

Did they like it?

Was their time well spent?

Did the material make sense?

Will it be useful?

Was the leader knowledgeable and

helpful?

Were the refreshments fresh and tasty?

Was the room the right temperature?

Were the chairs comfortable?

Questionnaires administered at the end

of the session

Initial satisfaction with the

experience

2. Participants'

learning

Did participants acquire the intended

knowledge and skills?

Paper-and-pencil instruments

Simulations

Demonstrations

Participant reflections

(oral andlor written)

Participant portfolios

New knowledge and skills of

participants

3. Organization

Support 8.

Change

Was implementation advocated,

facilitated, and supported?

Was the support public and overt?

Were problems addressed quickly and

efficiently?

Were sufficient resources made available?

Were successes recognized and shared?

What was the impact on the organization?

Did it affed the organization's climate

and procedures?

District and school records

Minutes from follow-up meetings

Questionnaires

Structured interviews with participants

and district or school administrators

Participant portfolios

The organization's advocacy,

support, accommodation,

facil~ation. and recognition

4. Participants'

Use of New

Knowledge

and Skills

Did participants effectively apply the new

knowledge and skills?

Questionnaires

Structured interviews with participants

and th eir supervisors

Participant reflections

(oral andlor written)

Participant portfolios

Degree and quality

of implementation

Direct observations

Video or audio tapes

S. Student

learning

Outcomes

•

.~

J

~

0

~

~

What was the impact on students?

Did it affect student performance

or achievement?

Did it influence students' physical

or emotional well-being?

Are students more confident as learners?

Is student attendance improving?

Are dropouts decreasing?

u

48

ED UCAT I ONAL I.EAOE1{S I-I II' / MAR C H 2002

Student records

School records

Questionnaires

Structured interviews with students,

parents. teachers, and/or

administrators

Participant portfolios

Student learning outcomes:

Cognitive (Performance &

Achievement)

Affective (Attitudes &

Dispositions)

Psychomotor (Skills &

Behaviors)

mentation is often a gradual and uneven

process, YOLI m<ly also need LO measure

progress at several time intervals.

You may gadler this inJonnation

through questionnaires or slnlctured

interviews with participants and their

How Will Informat ion

Be Used7

To improve program design and delivery

To improve program content, format,

and organization

To document and improve organization

support

To inform future change efforts

To document and improve the

implementation of program content

To focus and improve all aspects of program

design, implementation, and follow-up

To demonstrate the overall impad of

professional development

supervisors, oral or written personal

reflections, or examinatjon of participants' journals or portfolios. The most

accurate information typical ly COmes

from direct observations, either with

trained o bservers or by reviewing videoor audiotapes. These observations,

however, should be kept as unobtrusive

as possible (for examples, see Hall &

Hard, 1987).

YOll can analyze Ihis infonn<ltion to

heIp reSlnlcture future programs and

activities to facilitare better and more

consistent implementatio n .

Level 5: Studellt Lea ,."iug Outcom es

Level 5 addresses "the bottom line ~:

How did the professional development

activity affect snldents? Did it benefit

them in any way? The particular student

learning outcomes of interest depend ,

of course, on the goals of that specit1c

professional development effort.

tn addition to the stated goaJs, the

activity may result in inlpOrtam unintended o utcomes. ,For this reason , eval uations should always include multiple

measures of student leaming Ooyce,

1993). Consider, for example, elementary school educators who participate in

study groups dedicated to finding ways

to improve the quality of students'

writing and devise a series of strategies

that they believe will work fo r their

students. In gathering Level 5 informatio n, they find that their students' scores

on measures of writing ~I biliry over the

school year increased significantly

compared with those of comparable

students whose teachers did nOt use

these strategies.

On further analysis, however, they

discover that their students' scores o n

matJlematics achievement declined

compared with those of the other

snldents. This unintended o utcome

apparently occurred because the

teachers inadvertently sacrificed instnlCtional time in mathematics to provide

~perintendents. board I

members. and parents rarely

ask. "Can you prove it?"

Instead. they ask for evidence.

more time for writing. Had information

at Level; been restricted to the singJe

measure of students' writing, this import;mt unintended result might have gone

unnoticed.

Measures of student learning rypically

include cognitive indicators of student

perfom13nce and achievement, such as

ponfolio evalulltions, grades, and scores

from standardized tests. I.n addition, you

may wal][ co measure affective mit·

comes (attitudes and dispositions) ~lOd

psychomOtor o utcomes (skills and

behaviors). Examples incl ude students'

self.·concepts, srud)' habits. school attendance , homework completion r'dtes, and

classroom behaviors. You can also

consider such scboo lwide indicators as

enrollment in advanced classes. member·

ships in honor societies, participation in

school-related activities, disciplinary

actions, and retention or drop·out rates.

Student and school records provide the

majority of such illfonnation. You can

also include results from questionnaires

and structured interviews with students,

parents, teachers, and administrators.

LeveJ 5 infonnaLion about a program 's

overa ll impacl can guide im provements

in aU aspect's of professional development, including program deSign, imple·

mentation, and fOllOW-Up. In some

cases, infonnation on snldent learning

outcomes is used to estimate the cost

effectiveness of professional development, sometimes referred to as "return

o n investment n or uROl eval uation ~

(Parry. 1996; Todnem & Wamer, 1993).

Look fo r Evidence. Not Proof

Using these five levels of infonnatioo. in

professional development evaluations,

are you ready to "prove" that profes-sional development programs make ..

difference? Can you now demonstrate

A SS OCIATION FOR S U PERVI S I ON A NI) CURR I CliLUM Of. VF.LOPMI:NT

49

that a p~llticlilar profession,ll development program, and nothing e lse, is

solely responsible for the school 's 10

percent increase in student achievement scores or its 50 percent reduction

in discipline referrals?

Of course not. Ne'.trl)r all professional

development takes place in real-world

st.:ltings. The relationship between

professional development and improvements in student learning in these realworld settings is f,lr too complex and

includes too many imervening variables

to permit simple causal inferences

(G uskey, 1997; Guskey & Sparks, ( 996).

What 's more, most schools are engaged

in systemic refoml initiatives that

involve the simultaneous implementation of multiple innovations (FuUan,

1992). Isolating the effects of a single

program or activity under such conditions is lIsually impossible.

But in the absence of proof, you can

collect good evidence about whether a

professionaJ development program has

con uibutcd to specific gains in studem

lea ming. Superintendents, board

members, and parents mrely ask, "Can

you prove it? n Lnstead, they ask for

evidence. Above aU, be sure to gather

ev idence on measures that are meaningful to stakeholders in the evaluation

process.

Consider, for example, the use of

:U1ecdotes and restimonials. From a

methodological perspective, they are a

poor source of d:lttl. They are typically

highly subjective, and they may be

inconsistcnt and un reliablc:::. Nevenhe·

Icss, ~s any triaJ attorney will tell you ,

they offer the kind of personalized

evidence that most people believe, and

tl1C.~y should not be ignored tiS a source

of infom13tion. Of course, anecdotes

and testimonials should never form the

basis of fin entire eva luation. Setting up

l11eaningfuJ comparison groups and

using appropriate pre- and postmeasurcs provide valuable infornlation .

Time-series designs that include multiple measures collected before and

after implementation are another useful

alternativc.

Keep in mind, tOO , th:.II good evidence isn 't h,ud to come by if you

50

know what you ' re looking for before

you begin. Many educators find eV:lluation at Levels 4 and 5 difficult , expen·

sive, and lime-consuming because they

:tre conting in after the fact to sea rc h for

resu lts (Gordon, 1991 ). !f you don 't

know where you are going, it's very

difficu lt to teU whether you 've arrived.

But if you clarify your goals up front,

most evaluation issues faU into place.

Working Backwa rd

Through the Five levels

'!luce important implica tio ns ste m from

(his model for evaluating professional

development. First, e:ldl of these five

leve ls is important. The information

gathered at each level provides vital

data for improving the quality of professional development programs.

Second, tracking effectiveness <It one

level tdls YOLI nothing about the impact

at ule next. Although success ~Il an eady

level may be necessary for positive

results at (he nc},.'{ high er o ne, it's

clearly not suffident. Breakdowns can

occur at ,]flY point along the way. Jt's

imponam (0 be aware of the difficulties

involveu in moving from professional

devdopmem experiences (Levd I ) to

improvements in snluent learning (Level

5) and to p lan for the time ,md effort

required to build thjs conn ection.

EI) ll C,\T10 N ,\I. 1. I:.AOek s IIIP / MAR C Il 2002

The third implication, aocl perhaps

the most important, is lhis: In planning

professional development to improve

smdent learning, tbe order of lbese

levels must be reversetl. You must plan

"back'ward" (Guskey, 2001), staning

where YOll want to end and then

working back.

In backward planning, you first

consider the student learning outcomes

that you want to achieve (Level 5), For

exampk, do you want to improve

~ludents ' reading comprehension,

enhance uleir skills in problem solving,

develop (heir sense of confidence in

kaming Sitlwtions, or improve their

collaboration with classmates? Critical

analyses of relevant data from <Issessme nts of student learning, examples of

student work, iU1d school records are

espedally useful in identi.fying these

studem learning goals.

Then you determine, on the basis of

pertinent research eVidence, what

instructio nal practices and policies wiJJ

mOSf effectively and efficiently produce

those outcomes (Level 4). You need 10

ask) What evidence verifies tbat these

particular pmclices and policies will

le"d to the desired results? I-low good or

reliable is thal evidence? Was it gathered in a context s i mil~lr to o urs? \"'<ltch

out for popular innovations that are

more opinion-based than researchbased, promoted by people morc

concemed with " what sells" than with

Mwhm works." You need lO be camious

before jumping on any education bandwago n, always m:lking sure that t.ruStworthy evidence validates whatcver

approach you choose.

Next, consider what aspects of organization suppOrt need to be in place for

those practices and polides to be impkmc.::med (Level 3). So metimes, as I

mentioned earlier, aspects of the

org.anization actually pose barriers to

implementation . "No tolerance

poliCies regarding studem discipline

and grading, for example, may limit

teachers ' options in dealing with

tudenLS' be.h:lvio r:d o r leaming problems. A big part of planning involves

ensuring that o rganization elements are

in place to support the desired practices

and poliCies.

Then, decide what knowledge and

skl.IJs the participating professionals

must have to implement the prescribed

pnlctices and policies (Level 2). \Vhat

must they know and be able to do to

successfully adapt the innovation lO

llleir specific situation and bring about

the sought-after change?

Finally, consider what set of experiences will en:lble participants to acquire

the needed knowledge and skills (level

I). Workshops and seminars, especially

when paired with collaborative planning and stnlctured oppon-unities for

pmctice with feedback , action research

projects, organized sl1ldy groups, and a

wide range of other activities G Ul all be

effective, depending on the specified

purpose of the professio nal development.

This backward phlnning process is so

imponant because the decisions m.tde

at each level profoundly affect tho!'ic at

the next. For example, the particular

student le.tming outcomes you want to

ach ieve inllucnce lbe kinds of practices

and policies you implement. likewise,

the practices and policies you wam to

implement influence the kinds of organiz.'lUon SUppOl1 or change required,

(mel so on.

The context-specitic nature of this

work complicates matters further. Even

if we agree on lhe snldem leaming

outcomes that we want to achieve,

what works besl in o ne comext widl a

particular comm unity of educators and

a p:trt'icular group of students Lnight not

work as well in another contex't with

different educators and different

students. T ltis is what makes developing

examples of truly universal "best prclctices" in professional development so

difficult. \Vhat works always depends

on where, when, and with whom.

M

~ove all, be sure to gathe~

evidence on measures that

are meaningful to stakeholders

in the evaluation process.

Unfortunately, professional developers Gin faU into the same trap in planning rhat teadlers sometimes domaking plans in te.mlS of what they arc

going to do, instead of what they want

their students to know and be able to

do. Professional developers often plan

in terms of what they will do (workshops, seminars, institutes) or how dIe),

will do it (study groups, "ction researdl,

peer coaching). This dimin.ishes the

effectiveness of their efforts and makes

evaluation much more difficult.

Instead, begin planning professional

deve lopment with what you want to

achieve in terms of learning and

leamers and then work backw~lrd from

there. Planning will be much more efficient and the results wiH be mudl easier

to evaluatc.

analysis as a cemntl compo nent of all

professional development activities, we

can enhance the success of professional

development effons everywhere . •

References

Fu ll ~ln , M. G. ( 1992). Visions that blind.

EdIIC(ltiOll(l1 Leadersbip, 49(;) 19-20.

Gordon, ) . ( 1991 , August). M{;lsuring the

~goodness " of training. Training, 19-2;.

Gliskey, T. R. (1997). Research needs IO

link professional development and

student learning.Journal Of Staff

Development, 18(2), 36-40.

Guskey. T. R. (2000a). Evaluatillg proJi!Ssiollal deoelopmenl. Thousand Oaks,

CA: Corwin.

Guskcy, T. R. (2ooob). Grading policies

that work againSt standards :U1d how to

fix them. NASSP I3I1l/ellll , 84(620),

20-29.

Guskey, T. R. (2001). The backward

~lpproa ch . jOllrllal oJ Staff Dellclofr

II/ellt , 22(3), GO.

Guskc)" T . R., & Sparks, D. (1996).

Exploring tile relationship between

staff development lmd improvements in

stU(lenr Iearning.jourual Of Staff

Development, 17(4) , 34-38.

Hall, G. E., & Hard, S. M. ( 1987). Cballge

ill scbools: Facilitating tbe process.

Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Joint Conuninee on Standards for EducationaJ Evaluation. (1994). 77Je progrmn

evaluation sta.lldart/s (2 nd cd.). Thousa nd Oaks, 0\: Sage.

.Joyce, B. (1993). The link is there, but

where do we go from here? journal of

Staff Development, 14(3), 10-12.

PmT)" S. B. (1996). Measuring trdining's

ROI. Training & Development, 50(;),

72-75.

Sparks, D. (1996, February). Viewing

rdoml from a systems perspecth'e. The

Developer, 2, 6.

Spa rks, D. , & I'lirsn. S. (1997). A new

visio n Jor staff development .

Alexandn.1. VA: ASCD.

Tadnem, G., & Warner, M. P. (1993).

Using ROI (0 assess staff development

efforts. Journal Of sr(tJf DevelojJmellt,

14(3),32-34.

M aking Eva luation Central

Copyright © 2002 'I1lOlllas R. Guskey.

A lot' of good things are done in the

name of profcssio nal development. OUl

so are a lot of rouen things. What

educators haven 't done is provide

evidence to docwncnt the difference

between the two.

Eva luation provides the key to

making that distinction . By including

systema tic information garhering and

Tho mas R, Guskey (Guskey@uky.edu) is

a pro fessor o f education policy studies

and evaluation, College o f Education.

University o f Kent ucky, Taylor Educa tion

Building, Lexi ngton, KY 40 506, an d

author o f Evaluating Pro fessional Development (Corw in Press, 2000),

A SSOCI ,\ T [ ON FO R S lj P E R \, I ~ I Ol\ Al\.I) Ct; R RICU I. Il M D Ev": LO P~I EN T

51