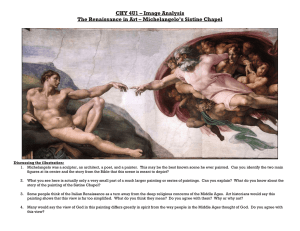

As the sun glistens over the peak of the Sistine Chapel, an unsure Michaelangelo stands before its daunting beauty. Ahead of him stands a seemingly impossible task, the painting of the Sistine Chapel Ceiling. With a surface area of more than twelve thousand square feet, painting something so vast while being suspended more than 68 feet above the ground would be difficult to say the least. Self-identifying primarily as a sculptor, Michelangelo was inexperienced with the fresco technique. How would a sculptor, new to such a complex technique, successfully complete the incredibly large project? Michelangelo gazed upon the ceiling. He realized that the journey would be hard, but his worry would do nothing to complete the task. This pivotal shift in mindset marked his first step toward the formation of a new habit: the belief in one’s ability to change. An enormous project was laid out before him. Undoubtedly, taken all at once, it would be impossible to complete, but Michelangelo knew this. In order to combat this, he made the ingenious decision to break up one large task into many smaller, more manageable pieces. This strategic approach, breaking a large project into many small pieces, showcases the very essence behind habit formation. Just as Micahelanglo divided the ceiling into subsections, section by section, the aspiring self-improvementee can simply their goal by making each checkpoint as easy as possible to reach. Despite the challenges presented before him, Michaelanglo’s everyday persistence and commitment to the mural became the foundation for what would be one of the greatest achievements in all of art’s history. His dedication and consistency stand as anecdotes to the importance of small improvements, one percent better every day. The story of the Michelangelo and the Sistine Chapel showcases all four of the Laws of Behavioral Change: 1. Make it Obvious. It was clear to Michelangelo that this would be no easy task. Coming into such a large project with limited experience in the field would be a worrying cue to many, requiring a need for change. The sheer vastness of the project was his cue. 2. Make it Attractive. His reward was obvious. If he completed the job, he would be paid 3000 ducats, the equivalent of millions of dollars today! Such a huge sum of money would obviously attract artists all over the world, and Michaelangelo knew he was lucky to be given this opportunity. 3. Make it Easy. For more reasons than one, painting the ceiling would not be easy. Such a massive canvas is daunting to be presented with. In order to make the job easier, Michelangelo developed special scaffolding and divided the ceiling into small, more manageable parts. 4. Make it Satisfying. By painting the ceiling one section at a time, Michelangelo created a sort of game for himself. He knew that each section completed would bring him closer to completing the entire job. Every small step forward would reward him with the feeling of accomplishment. It was that very feeling that kept him determined to move forward. Michaelangelo’s story may seem very specific, but the truth is this example can be widely extrapolated to your everyday life. Understanding how and why habits are formed is the key to forming your own good habits and getting rid of the bad ones. However, it is important to remember that success in your own habits, just like the painting of the Sistine Chapel, does not come over night. In order for Michaelangelo to finish his artwork, he had to adopt the philosophy “1% better every day.” No matter how much effort you put in, you must strive to stay consistent. Even the most remarkable artists would get nowhere without consistency. The impact of small changes can be immeasurable. Michelangelo didn’t paint the Sistine Chapel in a day, nor did he finish it in one fell swoop. Instead, it was an amalgamation of thousands of small and deliberate actions taken over the course of time, powered only by dedication and remembering the importance of his end goal. His story serves as a metaphor of sorts that we can apply to our own every day habits. This book was written to help you understand that even your tiniest habits become the foundation that your future is built upon. Atomic Habits compound over time. Approaching every aspect of your life with the intention to make the smallest consistent improvements will undoubtedly reward you with success. The journey that is building good habits, much like Michaelangelo’s mural in the Sistine Chapel, is a demonstration that greatness is not achieved all at once. Analysis: Atomic Habits uses very vivid analogies. For example, in chapter 1, James Clear references the 2003 British Cyclying team to showcase just how impactful small changes and tweaks in the teams training could be. This idea of atomic level optimization later becomes the backbone of Atomic Habits. With each new chapter comes a vivid analogy depicting the chapter’s key message in a way that readers can understand. In my alternate ending chapter, I referenced Michelangelo’s work on the Sistine Chapter and parallel it to the key ideas within Atomic Habits in order to summarize and conclude the book. James Clear carrys a conversational tone filled with vivid imagery in order to captivate and enthrall readers allowing them to understand his message on a more relatable level. Saying things like: “If you’re a millionaire but you spend more than you earn each month, then you’re on a bad trajectory. If your spending habits don’t change, it’s not going to end well. Conversely, if you’re broke, but you save a little bit every month, then you’re on the path toward financial freedom—even if you’re moving slower than you’d like.” James’ writing style is very similar to a conversation you might have with your friends or family. Because of that, readers can understand it and enjoy it. In my alternate ending essay, I tried to adopt James’ conversational tone while still incorporating ideas that readers might know something about. “The impact of small changes can be immeasurable. Michelangelo didn’t paint the Sistine Chapel in a day, nor did he finish it in one fell swoop. Instead, it was an amalgamation of thousands of small and deliberate actions taken over the course of time, powered only by dedication and remembering the importance of the end goal.” By referencing Michelangelo’s years of work on the Sistine Chapel, I was able to give an example of the importance of patience and consistence when building habits. Challenges: The biggest challenge I faced when reading this book was the act of actually changing my own habits. Throughout the book, you are given a clear path to identifying, understanding, and improving your own habits. It is easy to understand the concepts, but it is a completely new thing to put them into practice. Although it is not easy, I can definitely say that by changing my daily habits, I have become a more productive and effective version of myself. For example, in chapter 15, Clear says: “it takes time for the evidence to accumulate and a new identity to emerge. Immediate reinforcement helps maintain motivation in the short term while you’re waiting for the long-term rewards to arrive.” I decided to implement this idea to try and keep me on track in the gym. I now have two jars on my desk. One was filled with marbles and the other was empty at the start of my gym program. Each day that I went to the gym and completed my workout I would move one marble from the full jar to the empty one. Writing this now, coming to the end of my 8 week weight lifting program, the jar that was previously empty is almost full and the previously full jar only has 4 marbles left inside of it. By far the most challenging part of the book was sticking to the key ideas it talks about, however, they do seem to be paying off.