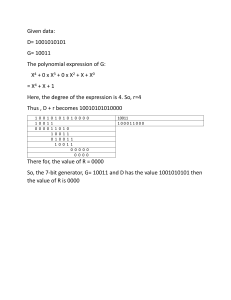

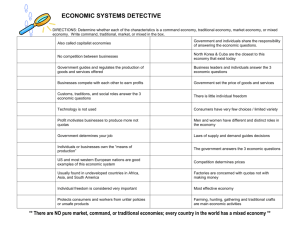

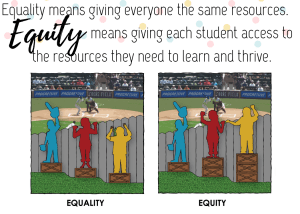

PARLIAMENTARY DIVERSITY AND GENDER QUOTAS A REPORT ON THE EFFECTIVENESS OF GENDER QUOTAS IN PROVIDING FOR GREATER EQUALITY Word Count: 3198 (excluding references and outline of contributions) Details of Group Members Adam O’Leary, 20344486 Molly Coogan, 20325913 Grace Zhu, 20362513 We declare that this is all our own work except where we have cited other work. PARLIAMENTARY DIVERSITY AND GENDER QUOTAS PARLIAMENTARY DIVERSITY AND GENDER QUOTAS A REPORT ON THE EFFECTIVENESS OF GENDER QUOTAS IN PROVIDING FOR GREATER EQUALITY Table of Contents 1.1 Abstract 2.1 Introduction 1.1 Abstract The topic that this report explores is gender equality. More specifically, it examines the effectiveness and workability of gender quotas in national parliaments, and whether those quotas have the ability to stimulate greater progress in the general area of gender equality. We have used data analysis in order to study whether two primary arguments against the idea of gender quotas have any merit. There are three separate sets of data across 27 European countries that are assessed in this report. These selections of data are the percentage female representation in national parliaments, each country’s gender equality index score, and their index score with respect to the balance of political power across gender. This data is analysed over the 13 years between 2005 and 2018. The proportional changes in these summary measures were calculated and then compared to each other, which resulted in a number of interesting observations. Upon comparing the changes in female parliamentary representation and the same countries’ gender equality scores, we found a strong correlation between the two. This suggests that quotas do not frustrate progress or reform and maintain the potential to bring greater change in the area of gender equality, contrary to the belief of opposition. When the changes in female parliamentary representation were compared to those in the gender balance of political power, we concluded that there is no evidence to suggest that members of parliament will experience any notable detriment to their influence simply because of assistance from a quota. To conclude, we found that gender quotas have great beneficial possibilities, and since there was no statistic-based evidence to support popular counterarguments, we would fully support their imposition. 1 o 2.2 Data Selection o 2.3 Definition of ‘Change’ etc. 3.1 Statistical Analysis o 3.2 Female Representation Statistics o 3.3 Statistics on Gender Equality Index Scores o 3.4 Statistics on Gender Balance of Political Power 4.1 Conclusion o 4.2 Recommendations 5.1 References o 5.2 Data Source o 5.3 Academic Sources 6.1 Team Members’ Contributions o 6.2 Molly Coogan o 6.3 Grace Zhu o 6.4 Adam O’Leary PARLIAMENTARY DIVERSITY AND GENDER QUOTAS 2.1 Introduction As a group, we decided to report on the topic of gender equality, as it remains a prevalent and contentious issue despite the level of reform and cultural shift that has taken place in recent decades. In a world that has become obsessed with identity politics, there is greater pressure on authoritative bodies to implement change on the basis that women are inherently oppressed in our modern society. One of the primary concerns in relation to gender equality is the lack of female representation in national parliaments. The proposed solution to this issue is the introduction of gender quotas which can be divided into three distinct categories: reserved seats, party quotas and legislative quotas (Krook 2005). Each of these quota types aim to ensure optimal equality of outcome by making guarantees as to the minimum number of women that will stand as candidates and potentially accede to political office (Dahlerup 2006). These quotas are implemented in the hope of a greater gender balance within parliaments so that women have more power over political affairs and can therefore bring about greater gender equality reforms. However, that expectation is said to be incorrectly predicated on the assumption that gender is intrinsically tied to political opinion in the sense that all women have the same viewpoint. Another argument against gender quotas has been that they would undermine the authority of female politicians as they may not be respected as other politicians that have not benefitted from quotas. The aim of this report, therefore, is to analyse the data relevant to this issue and deliver a selection of unbiased findings. We as a group have examined empirical evidence and statistics from 27 European nations in order to determine how effective gender quotas in parliament are across two measures: the change in each nation’s gender equality index score and the change in their political power equality score. 2.2 Data Selection Our analysis is spread over three separate sets of data, those being female parliament representation, gender equality index scores, and gender balance in political power. The period of time that we chose to examine in relation to these statistics was the 13 years between 2005 and 2018. While the selection of this time period was subject to the constraint of data availability, there was also an incentive for us to choose this relatively large frame. Given that the parliamentary term in European countries tends to be between 4-6 years, we hoped to incorporate a minimum of 2 separate parliament formations into our analysis in order to give an accurate depiction of the reasons for the change taking place. 2.3 Definition of ‘Change’, ‘Increase’ etc. Another point to address is what this report is trying to convey when using terms referring to changes in different values. When analysing our selected data from the 27 European countries, we calculated percentage changes in different measures which are proportional to their respective original values. This allows us to accurately compare and contrast the different results we obtained from examination of the different data sets. For the sake of convenience, this report simply refers to the shorthand rather than repeating the fact that these are proportional percentage values. 2 PARLIAMENTARY DIVERSITY AND GENDER QUOTAS 3.1 Statistical Analysis 3.2 Female Representation Statistics The first data set to be examined is of course the progression of female representation in parliaments. The focus of our analysis was on the overall change in the percentage of female representation which is essential in order to establish the context surrounding this issue with regard to the selected data subjects. We also used this data set to compare to others and examine the strength of their correlations. Percentage Female Representation 50 Female Representation in Parliament 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 2005 2018 Country Figure 1 The bar chart above (Figure 1) represents the female representation in parliament for each of the 27 countries in 2005 and 2018. At first glance, it is clear that this representation has dramatically improved in the wider European context. Out of the 27 countries, only 4 of them did not experience an increase in female representation, and the proportional decreases in these cases were very minor with the largest being approximately 9.28%. On the other hand, there were several countries that experienced very dramatic increases in their level of female representation. A particularly noticeable example, which might be considered as an outlier of sorts, was Italy. The Italian parliament had a very noticeable shortage of female presence with only 10.9% of the members being women. This figure rose to 35.3% by the end of 2018 which was well above the mean percentage of 28.5%. The extent to which female representation has increased in each country can be visualised through use of the histogram (Figure 2) on the next page. 3 PARLIAMENTARY DIVERSITY AND GENDER QUOTAS Figure 2 By examining the spread of the change in female representation in parliaments, we can make several observations. These are that the majority of countries have experienced a reasonably large increase in female representation of between 24% and 91%, and that while a large portion of the data is found in the first bin, only a third of those countries actually experience a negative change and the rest had modest increase. Furthermore, some countries such as Italy and France that used to have particularly small percentages have tended to correct that issue by over doubling or tripling their female representation. Overall, this tells us that gender inequality in parliamentary procedure is an issue that is taken seriously across Europe and is in the process of being fixed. Furthermore, we can use these findings to discover if the imposition of gender quotas can be an effective addition to that process. 3.3 Statistics on Gender Equality Index Scores As previously mentioned, one of the main criticisms of gender quotas is that they are entirely based on the assumption that a person’s political opinion is directly linked to their gender. The idea behind these quotas is that with a greater number of women in parliament, issues that primarily or exclusively affect women will be addressed more effectively. The relevance of gender is reinforced by a number of surveys, which collectively show that female politicians have a “mandate of difference” (Skjeie, 1998). The manner in which we felt it would be easiest to determine whether gender has a notable degree of relevance in addressing equality issues and generally influencing parliamentary decisions was to examine the changes in overall gender equality in the 27 countries which acted as our data subjects. This index, developed by the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE), takes into account multiple different factors such as earnings and economic 4 PARLIAMENTARY DIVERSITY AND GENDER QUOTAS power, all of which are affected by legislation and the administration of the State. We have analysed the gender equality index and the scores that each country has received in this index in both 2015 and 2018. We then calculated the changes in these scores in order to crossreference these against the respective changes in female representation, as shown (Figure 3). Female Representation v. Gender Equality Chnage in Gender Equality Score 35,0000% -50,0000% 30,0000% y = 0,0805x + 0,0747 25,0000% 20,0000% 15,0000% 10,0000% 5,0000% 0,0000% 0,0000% 50,0000% 100,0000% 150,0000% Change in Female Representation 200,0000% 250,0000% Figure 3 Our calculations suggest that there is a linear correlation of approximately 0.61 between the change in a country’s gender equality score and their changing female representation in parliament. This means that there is a strong positive relationship between the change in the two variables: as the percentage of female representatives in parliaments increases there is a strong tendency for that country’s gender equality score to increase. While this correlation may initially appear to work in favour of gender quotas, in reality it does not directly prove that gender is relevant in addressing political issues such as gender inequality or that these quotas are guaranteed to be beneficial. This is because of the principle that correlation does not imply causation which leaves us unable to deduce for certain that there is a cause-and-effect relationship between these two variables. What is more, while the linear correlation between these changes may be strong, it is still relatively far from being a perfectly correlated observation and this makes it even more difficult to suggest an element of causation is present. Even if there was a relationship between the change in female representation and change in gender equality score, it would be illogical and intellectually disingenuous to automatically assume that the change in female representation is what causes the latter change to occur. There is just as strong an explanation to say the opposite, in that while gender equality conditions in a country improve there is a subsequent increase in female politicians being elected to parliament. When then there is a greater level of gender equality in a given country, that inherently means that women will be viewed to be just as competent as men 5 PARLIAMENTARY DIVERSITY AND GENDER QUOTAS and obviously the population will be more inclined to vote these women into parliament should they decide to be politicians. The strong correlation between the change in female representation and gender equality does however allow us to eliminate certain extreme possibilities in the analysis of this data. We can tell immediately that the introduction of more women into parliament does not somehow frustrate the progress of parliaments in relation to gender equality reform. Even if female politicians are not collectively obsessed with pushing for more gender equality, there is little reason to believe that they are against these policies in any sense. This is indicative of the fact that gender quotas will not present any notable disbenefits for gender equality reform if implemented and will maintain a high potential to benefit the wider society in the areas of equality and diversity with more widespread experience and ideas. 3.4 Statistics on Gender Balance of Political Power With the question of the relevance of gender in politics set aside, this report aims to determine the validity of another argument against the introduction of gender quotas into parliamentary formation. This counter-argument is that quotas will undermine the influence that women can have in politics as the legitimacy of their political position is threatened. The broad sentiment among the opposition to gender quotas is that women, especially those who perhaps had not secured a seat in parliament beforehand, will receive a lesser degree of respect from their colleagues because they were assisted by quotas (Koch, 2015). This is consistent with the fear that people will believe that women elected with the help of a quota will be considered to be undeserving of their position. In order to see if this anti-quota ideology has any statistical basis, it is not enough to simply look at the composition of each of the 27 countries’ parliaments. It is necessary to look at a more specific index, which is that which attributes a score to each country based on their gender balance with regard to political power, similar to the overall gender equality index. These statistics, which were also compiled by the EIGE, give an accurate measure of the political influence and positions that women have in the parliaments of each country. By comparing this data to the statistics relating to parliamentary representation, we can discover whether the political standing of women is actually infringed by quotas. It is required here that we look at countries with quotas in place in isolation so that this data can then be compared to the overall population of 27 countries. (See Figure 4 and Figure 5 on the next page). The changes in this case are once again those experienced in the thirteen years between 2005 and 2018, to allow for easy and accurate comparison. 6 PARLIAMENTARY DIVERSITY AND GENDER QUOTAS Female Representation v. Political Power (Countries with No Quotas) Change in Gender Baalance of Political Power 45,0000% 40,0000% 35,0000% 30,0000% 25,0000% 20,0000% 15,0000% 10,0000% 5,0000% 0,0000% -10,0000% 0,0000% y = 0,3133x + 0,1192 10,0000% 20,0000% 30,0000% 40,0000% 50,0000% Change in Female Representation 60,0000% Figure 4 Change in Gender Baalance of Political Power Female Representation v. Political Power (Overall) 140,0000% 120,0000% y = 0,4553x + 0,1116 100,0000% -50,0000% 80,0000% 60,0000% 40,0000% 20,0000% 0,0000% 0,0000% -20,0000% 50,0000% 100,0000% 150,0000% Change in Female Representation 200,0000% 250,0000% Figure 5 When examining the five countries from our selection of 27, we can see that while there is a positive linear correlation, it is quite weak with a coefficient of only 0.49. There is certainly a trend in which an increase of female representation gives rise to a greater gender balance when it comes to political power. Given the limited data in this subset, we cannot derive many assumptions or observations from this correlation, but it is quite useful when compared to the overall data set. When later looking over the statistics in relation to all 27 of the countries, we get a much clearer picture of things. Purely by comparing the trendlines, when countries with quotas are added to the mix, we can see that there is a slightly greater rise in the balance of political power as regard to gender. There is a much stronger correlation coefficient of 0.72 and this very strong correlation means that there is a very tight-knit relationship between the change in female representation and the change in gender quality in the context of political power. 7 PARLIAMENTARY DIVERSITY AND GENDER QUOTAS Again, unfortunately, we are faced with the problem of whether this correlation is also implicit of a causation relationship between the two variables. Despite the fact that in this case we are dealing with a correlation coefficient that is much stronger than that in the analysis under Appendix 3.3 and the analysis of the 5-country data set, it would still be analytically incorrect for us to make the assumption that causation is present. Either way, whether or not an increase in the number of women in parliament is directly linked to an increase in the balance of political power across gender groups is not the question that we are trying to answer. The question at hand is whether the imposition of quotas undermines the political power of the women that stand to benefit from them. There are two separate observations from the data that contradict that belief. 1. When looking at the trendlines, there is a slight increase in the slope from when all 27 countries are taken into account to when only those countries without quotas are included. While this is most likely a reflection of more accuracy from more data, the comparison refutes the idea that gender quotas could frustrate progress towards a situation where political power is divided more equally across genders 2. Ignoring the trendlines or a comparison between the two datasets, the correlation between the change in female representation and the change in the gender equality of the political power of the 27 countries is a very strong and positive one. Given that the majority of the countries have gender quotas, if the idea were valid that these quotas inhibit the influence of women due to a lack of respect, then we would expect this correlation to be much weaker if not negative. 4.1 Conclusion In analysis of the summary measures reflecting information gathered across the 27 countries we examined, we can divide our findings into three main observations. The first is that, as a collective, the 27 European countries that acted as our data subjects had experienced a large increase in the number of women who stood as members of their national parliaments. It is clear from this that there has been great progress on the issue of gender inequality in parliament, irrespective of whether there were any quotas in place. The second observation comes in response to the claim made by those who oppose gender quotas, which is that gender is irrelevant in terms of politics and that a parliament without equal representation is able to adequately address gender and equality issues. The data examined in evaluation of this idea was that of the female representation in national parliaments compared to the changes of the score of each country in terms of the gender equality index. Our calculations found that there was a strong, positive linear correlation between these summary measures. While this may not guarantee a relationship of causation, it shows that gender has relevance when it comes to parliament and that it may in fact lead to greater gender equality for the state that parliaments legislate for. 8 PARLIAMENTARY DIVERSITY AND GENDER QUOTAS The third observation into which we got an extensive insight responded to a separate claim, which is that the imposition of gender quotas could potentially lessen the power of women in parliament as they lose respect from their colleagues. The attitude from gender quota opposers seems to be that women will be viewed as less qualified and therefore the quotas would be quite counter-intuitive. However, when we examined the changes between female representation in parliaments and the change in the gender balance of political power over the same period, it appeared that this could not be the case. There existed here another even stronger correlation between the two, suggesting that quotas cannot be said to have this negative effect, at least not to a significant extent. 4.2 Recommendations Throughout this report, our group has used data analysis to rebut two of the main arguments used against gender quotas. By virtue of our findings, we feel that these arguments cannot be said to have merit, at least not in the European context represented by our 27 chosen countries. In carrying out this function, our data has also hinted at some potential benefits to be gotten from gender quotas, such as greater efficiency in bringing gender equality reform associated with more diverse parliaments. These benefits considered, our group is comfortable in recommending the introduction of gender quotas to parliaments and political parties alike, as well as in other aspects of society and business. 5.1 References 5.2 Data Source European Institute for Gender Equality. (2021). Gender Statistics Database (online). Available from: https://eige.europa.eu/gender-statistics/dgs (accessed 19/2/2021) 5.3 Academic Sources Krook, M. Lena. (2004). Gender Quotas as a Global Phenomenon: Actors and Strategies in Quota Adoption. European Political Science 3 (3): 59-65 Dahlerup, D. and Freidenvall, L. (2005). Quotas as a Fast Track to Equal Representation for Women: Why Scandinavia Is No Longer the Model. International Feminist Journal of Politics 7(1): 26-48 Raphael, H. (2015). Board Gender Quotas in Germany and the EU: An Appropriate Way of Equalising the Participation of Women and Men?. Deakin Law Review 20(1): 57 Skjeie, H. (1998). Credo on Difference – Women in Parliament in Norway. Women in Parliament: Beyond Numbers (A. Karam, ed.) pp. 183-189, IDEA 9 PARLIAMENTARY DIVERSITY AND GENDER QUOTAS 6.1 Team Members’ Contributions 6.2 Molly Coogan For my part in the creation of this report, I decided to focus on researching the area of gender equality. I found and studied a number of different academic sources on this topic and chose the gender equality index provided by the European Institute for Gender Equality as the data set to study. I used Microsoft Excel to make a number of different calculations, including the linear correlation between the proportional changes in this index and the percentage of female representatives in national parliaments. This work was essential in comparing these two statistical measures and led to our team making a number of interesting findings. I examined all this data and wrote an extensive analysis for the actual report. Overall, my research and analysis furthered the idea that gender quotas are a viable solution to gender inequality, which was the overall area discussed in our report. 6.3 Grace Zhu My task for this report was to look at the gender balance of political power across our chosen 27 countries in Europe. During my research I came across a very broad variety of opinions across academic literature which were very helpful in giving me a general idea of the topic and added greatly to the report’s content. However, the majority of the writing I did was based on the data that I sourced and analysed. Within the website of the European Institute for Gender Equality, there was an extremely helpful subsection under which each country was given an index score based on gender equality in terms of political power. Following a similar model to Molly Coogan’s, I compared the proportional changes between this and female representation from 2005-2018. From my findings, we were able to derive a number of summary measures and in my writing, I developed a strong, data-based argument for the implementation of quotas which was of course an essential aspect of our conclusion. 6.4 Adam O’Leary For my contribution to this report, I completed several general tasks which were important in terms of the overall preparation and presentation of the report. First of all, I focused on researching the general empirical evidence and academic literature relating to gender quotas and their effectiveness. Alongside this, I examined the data available on female representation in parliament for each of 27 European countries. These two areas of research were fundamental in the establishment of context for our report and allowed me to create a set of data which we used to compare to others and observe linear correlations. In terms of presentation, I combined the analysis and writings that both Molly and Grace had prepared with my own and formatted all the information into a tidy and professional report. This also involved the creation of relevant and clear graphs to coincide with the text. Subsequent to this, I further combined all the raw data we had analysed and tided it up into a single, presentable Excel spreadsheet. 10