Modernism vs Postmodernism: Key Concepts & Jeepney Case

advertisement

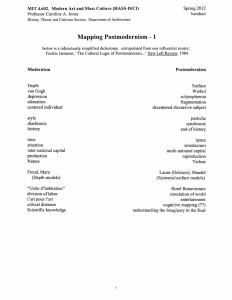

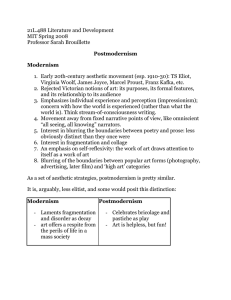

WHY DO WE HAVE TO TALK ABOUT THE MODERNISM SCHOOL OF THOUGHTS? Do you have any idea on what is a state-centric politics all about? State-centric politics - the emergence of the State, as a central apparatus for consolidating power, became a historical milestone that marginalized civil society and the individual in the private sphere, not only in the domain of political practice but also, and more importantly, in the domain of political theory. This powerful apparatus consolidated control, often marginalizing civil society and individual freedoms. This shift wasn't just felt in practical politics, but also in how we understand them. Political theory became heavily focused on the state itself, leaving less room for discussions of the individual and civil society. (Example) •Think of the rise of absolute monarchies in Europe. Kings held immense power, dictating laws and suppressing dissent. This left little space for citizen participation or independent thought. •The imposition of martial law under President Ferdinand Marcos in 1972 exemplifies this statecentric approach. While aimed at curbing communist insurgencies, it resulted in widespread human rights abuses and limited civil liberties. Universal Truths - Modernism often emphasized the possibility of reaching universal truths through reason and scientific inquiry. Postmodernism challenges this notion, arguing that knowledge is always contingent on specific historical contexts and social perspectives. Morality is another arena ripe for critique. Postmodernism reminds us that ethical codes are shaped by specific cultural contexts. What's considered moral in one place might be taboo in another. Example: Eskimos allowed their elderly to die by starvation. Modernists (thinkers from the late 1800s to mid-1900s): Believed everyone is like a puzzle piece - there are only two shapes, boy/man and girl/woman. These shapes come from your body (science!). They thought these shapes meant everyone had different, set roles in life (men do X, women do Y). But some Modernists also believed in fairness, so they fought for equal rights within those two shapes (like women getting to vote). Postmodernists (thinkers from the mid-1900s to today): Said the puzzle piece idea was too simple. Gender is more like a rainbow - there are many colors, not just two! Cultures and societies decide what each color means (what it's like to be masculine or feminine). These meanings can change over time! There might even be people who don't fit any one color exactly. They believe everyone should feel free to choose their own color (gender identity). Remember: Not all Modernists were exactly the same, some challenged the two-piece idea. Postmodernists don't ignore bodies, but they say our bodies alone don't define who we are. Grand Narratives - Modernism often relied on overarching narratives that explained history, progress, and human experience from a universal perspective. Postmodernism critiques these grand narratives, arguing that they ignore the fragmented and subjective nature of knowledge. Grand narratives are like tall tales in the Philippines - stories of national unity and progress that everyone's supposed to believe. But postmodernism, the ultimate critic, jumps in and says, "Hold on a minute!" Grand Narrative: One Nation, One Dream This story says Filipinos are all on the same team, working together to get richer and more modern. Sounds good, right? Postmodernism Dunks on the Story Who's on the Team? Are indigenous people and those in poverty part of this team? Or are they stuck on the sidelines watching the rich get richer? Is Progress Fair? Does this "progress" benefit everyone equally, or does it widen the gap between rich and poor? One Culture Fits All? The Philippines has tons of cool traditions! Does everyone have to be the same to be united? The New Game Plan Postmodernism says there's no one-size-fits-all story for the Philippines. It's more like a huge basketball tournament with many teams – each region, group, and culture has its own story to tell. The Takeaway Grand narratives aren't bad, but they can be too simple. By looking at the Philippines from different angles, we can create a more inclusive and realistic story of a nation moving forward together. After all, the people who win the war always tell the story. Objectivity - modernism placed a high value on objectivity, believing that knowledge could be independent of the knower. Postmodernism argues that all knowledge is shaped by the knower's position, language, and culture. Rationality - While not abandoning reason entirely, postmodernism questions its absolute authority. It emphasizes the role of emotions, experiences, and the unconscious in shaping our understanding of the world. In the context of the Jeepney faceout here in the Philippines, modernization advocates, armed with reason and data, push for their phase-out. But before we hail a goodbye, let's see how objectivity and rationality clash with postmodern perspectives in this complex issue. Modernists: Waving the Flag of Objectivity and Rationality Cold, Hard Facts: Modernists rely on data. They point to pollution statistics, accident rates, and passenger capacity limitations of jeepneys. These paint a clear picture: a system in need of an upgrade. Their approach is logical – replace jeepneys with cleaner, safer alternatives. Rational Solutions for a Rational World: Imagine a giant spreadsheet filled with numbers. Modernists analyze this data to find the most efficient and logical solution. They might propose a cost-benefit analysis, favoring a large-scale shift to modern buses. Safety and efficiency reign supreme. But Hold On, Says Postmodernism Postmodernism throws a wrench in the objective machine. It argues that data can be a doubleedged sword: Whose Objectivity? Modernization benefits often focus on environmental concerns and passenger safety. But what about the cultural significance of jeepneys? Objectivity can overlook these non-quantifiable aspects. Beyond the Numbers: Modernist solutions might not consider the human cost. Jeepney drivers, whose livelihoods depend on these vehicles, could face unemployment and economic hardship. A one-size-fits-all approach might not fit everyone. Lived Experiences and the Power of Stories Postmodernism emphasizes the importance of lived experiences: The Driver's Seat: Imagine a jeepney driver struggling to make ends meet. The datadriven push for modernization might feel like a threat to their way of life. Understanding their stories is crucial. Jeepneys and Regional Identity: Manila's solution might not work everywhere. Jeepneys might be a vital transportation lifeline in smaller towns where public options are scarce. A blanket phase-out ignores regional contexts. The Heart of the Jeepney Beyond statistics, Filipinos have a deep emotional connection to jeepneys. They represent a cultural icon, a symbol of ingenuity and resilience. Modernization shouldn't erase this cultural identity. Finding Common Ground: Beyond Objectivity Modernism's data-driven approach is essential. But by incorporating the perspectives of those affected, we can create a more balanced solution: Modernization with a Human Face: Upgrading jeepneys with cleaner engines or creating alternative livelihood opportunities for drivers could be explored. Gradual Transitions: A slow phase-out with government support allows for a smoother shift, minimizing economic hardship. Celebrating Heritage: Modernization doesn't have to erase the past. Preserving classic jeepneys in museums or designated routes can keep the cultural connection alive. The future of the jeepney shouldn't be a one-sided story. By combining objectivity with the richness of lived experiences, we can find a solution that ensures a cleaner, safer future while preserving the heart and soul of this iconic Filipino symbol. THEREFORE, LET ME ASK YOU. Whose Reason? Whose Objectivity?: Modernity often presents its logic and facts as neutral, but are they? Couldn't these "objective" viewpoints be shaped by the dominant cultures and power structures of the time? Beyond Universals: Modernity often seeks universal truths, but what about the experiences of marginalized groups or those outside the Western world? Doesn't their knowledge offer valuable, yet often excluded, perspectives? The Limits of Logic: Modernism emphasizes logic and reason, but what about emotions, intuition, and lived experiences? Don't these subjective elements also play a role in shaping our understanding of the world? Isn't the constant questioning and re-evaluation central to Postmodernism a more open and dynamic way to approach new knowledge? By critically examining the foundations of Modernity, Postmodernism opens the door to a more complex and inclusive exploration of the world. It's not about throwing out reason entirely, but rather acknowledging its limitations and embracing the richness of diverse perspectives in creating new knowledge