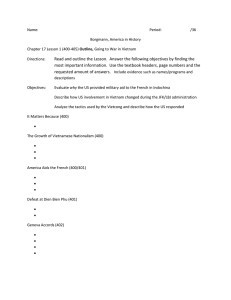

Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vol 3, No 2 (2017) 171-186 Consuming doi moi: Development and middle class consumption in Vietnam Arve Hansen* Abstract: Since doi moi, Vietnam has undergone a variety of social and economic transformations. Among the most obvious are found in the realm of consumption. The new openness to international trade and foreign investments has radically increased the availability of goods. And new opportunities for income have led to increased purchasing power in most social strata, although to very different extents. High-consuming urban middle classes are emerging rapidly-Vietnam’s middle class is indeed considered the fastest growing in Southeast Asia-symbolising economic progress and modernisation on the one hand and growing inequalities and environmental unsustainability on the other. These changes are reflected in surging consumption of a wide variety of goods, from household appliances and food items to vehicles and luxury products. This paper approaches the new ‘socialist consumer classes’ partly through the particular politicaleconomic contexts that have fostered them, but mainly through the consumption patterns and consumer culture that define them. Combining secondary statistical data with insights from ethnographic fieldwork, the paper discusses the drivers of changing consumption patterns and investigates the new roles of goods in everyday middle-class practices in Hanoi, in turn using consumption as a lens to analyse post-doi moi society. Keywords: Middle class; consumption; practice theory; doi moi; Vietnam; development. Received 2nd April 2017; Revised 25th April 2017; Accepted 29th April 2017 1. Introduction* to represent 80 percent of the global middle class by 2030 and to account for 70 percent of the world’s total consumption expenditure the same year, much due to Asia’s rapid economic growth (UNDP 2013; Hansen et al. 2015)1. From an academic point of view, understanding the social, economic and cultural realities hiding behind these numbers represents an intriguing field of inquiry. From the perspective of environmental sustainability understanding this shift becomes imperative. The shift of the global economy that Peter Dicken (2015) has been analysing since 1986 continues materialising. However, while production has been moving East and South for decades, a new shift is underway in the form of consumption. The number of middle-class consumers in Asia has now been estimated to be close to equal that of North America and Europe (Kharas et al. 2010). The middle classes in the ‘South’ are roughly projected 1 Numbers from the Human Development Report 2013, based on estimates by the Brookings Institution (2012, in UNDP, 2013). They consider middle class those that earn or spend between USD 10 and USD 100 a day in 2005 USD PPP terms. * Centre for Development and the Environment University of Oslo. Guest Researcher, Institute for European Studies, Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences; email: arve.hansen@sum.uio.no 171 172 Arve Hansen / Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vol 3, No 2 (2017) 171-186 In a world that is already consuming the planet to excess, and where the mature capitalist countries have not managed to create the ‘development space’ called for by the Brundtland Comission in order to let poorer parts of the world raise their living standards (Hansen et al. 2015), the rapid rise in levels of consumption in other parts of the world will put further strain on the environment. The so-called ‘Rise of the South’ thus reaffirms the position of increasing levels of consumption among the main challenges to sustainable development globally (McNeill et al. 2015). While much effort has been made in recent decades to make energy use more efficient and production processes cleaner, governments in affluent countries appear both unable and unwilling to curb upwards spiralling consumption patterns. A complex combination of reasons is behind this disinclination. Most fundamental, however, is the fact that limiting consumption often challenges economic growth (Wilhite et al. 2015). Capitalism’s growth imperative is at the core of the world’s sustainability challenges, and so far, theories of decoupling and green economy remain highly theoretical when analysing trends globally (Hansen et al. 2015; McNeill et al. 2015). Thus, while major technological advancements have been made, the global resource use continues increasing rapidly. However, in a time when high-growth capitalism seems to represent the only remaining viable alternative for developing countries, a few of the fastest growing economies in the world are claiming to have found their own model of development; the ‘socialist market economies’ of China, Vietnam and Laos. Over the past three decades, these three countries have stood out globally with consistently high rates of economic growth (Malesky et al. 2014). Vietnam is presented as a development success story and even ‘textbook example’ of development by the World Bank and other development donors (JDPR 2012); no small achievement for a country ruled by a communist party. The governments of the three countries claim to have found a middle-ground, using the market economy as a tool to deliver sustainable and just progress in a socialist society. However, questions are asked regarding the sustainability of the development models of all three countries. Considerable challenges for economic development persist, social inequalities are increasing rapidly, and the environmental impacts of resource-intensive development strategies have been severe. With exportoriented development strategies, much of the environmental degradation has been closely tied to consumption elsewhere, but domestic consumption is representing an increasing share. The alarming levels of air pollution in Beijing and Hanoi are for example to a significant extent caused by the transition to private motorised mobility in these cities. Also in these countries high-consuming urban middle classes are emerging rapidly, and domestic consumption is targeted as important drivers of future growth in both China and Vietnam. Can we expect the ‘socialist market economies’ to handle consumption better and develop more sustainably than the mature capitalist countries have done? And how does the emergence of high-consuming urban middle classes fit into the socialist visions of these countries? This paper focuses on Vietnam, and approaches the development of the ‘socialist market economies’ from the perspective of consumption and sustainability, focusing on rapid changes in urban consumption patterns at the Arve Hansen / Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vol 3, No 2 (2017) 171-186 intersection between development strategies and everyday practices. Vietnam’s development success story following the introduction of the doi moi market reforms are well-known by now (Van Arkadie et al. 2003). Some attention has also been given to the challenges that Vietnam is facing in both crafting its own development model (Beresford 2008), in sustaining growth and achieving industrial upgrading (Masina 2006, 2012), and dealing with the negative effects of development, such as inequality and environmental degradation (Hansen 2015a). This paper will take inequality as a starting point, but mainly focus on the relatively well-off side of the coin. That is, the paper will not focus on the elite, but the rapidly expanding middle class. The presence of these new consumers is being felt in Vietnam’s cities, where new shops, supermarkets, cafes and gated communities are popping up at an impressive speed, as well as in the heavily motorised streets. After a discussion of the theoretical starting points for the paper’s discussion of development and consumption, I will analyse some of the new consumption patterns that arise with the new middle classes, giving special attention to the private automobile. I will then discuss these new consumers in the context of Vietnam’s vision of a socialist market economy. Methodologically, the paper draws on fieldwork in Hanoi between 2012 and 2017, mainly through what I have termed a ‘motorbike ethnography’ (Hansen 2016ab). This also included semi-structured and indepth interviews with policy makers, car and motorbike retailers, car and motorbike manufacturers, and a total of 30 car owners 173 and 16 motorbike owners. For the latter group of informants, I mainly used snowball sampling. My informants came from a wide range of occupations and social positions, and included military officials, stateemployed academics, businessmen and businesswomen, and public sector employees and government officials of different ranks, including family members of high ranking officials. As is discussed below, all my car-and motorbike-owning informants can be lumped together as belonging to the Vietnamese middle classes. Their incomes ranged from average to very high, and while none could be considered poor, a few were clearly bordering the upper class. 2. Development and middle class consumption: theoretical starting points How can changing consumption patterns be approached in contexts of rapid economic growth? First of all, this paper is in line with the now substantial body of social scientific research that dismisses mainstream economic theories of the rational selfmaximizing human individual as a useful starting point for understanding consumption. Instead, I will discuss the symbolic meaning of goods as well as approaching consumption through practices, before briefly discussing the combination of consumption and development research. The classic social scientific approach to consumption looks at the symbolic meanings of goods. From Veblen’s (2005 [1899]) conspicuous consumption and emulation effects through Douglas and Isherwood’s (1979) The World of Goods and Bourdieu’s (1984) Distinction, this has represented a central part of enquiry into 174 Arve Hansen / Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vol 3, No 2 (2017) 171-186 how consumption patterns change and how humans use material objects in social situations. The ‘cultural turn’ of the social sciences took the focus on symbolic communication to another level, to the extent where consumption was close to totally divested from the material world (Warde 2005). Obviously, status-seeking behaviour is central to many forms of consumption, and I will return to this point below. An exaggerated focus on symbolism does however lead to a neglect of more mundane forms of consumption. Thus, in the 2000s a body of research started emerging that instead focused on everyday life and inconspicuous consumption (Gronow et al. 2001; Shove 2003). These strands of research eventually converged in the highly influential revival of social practice theories. Consumption research, along with many other parts of social sciences, has indeed seen a practice turn. Although the practice approach has deep theoretical roots, its application to consumption research is a rather recent phenomenon. As Warde (2005) argues, even the two most prominent figures in modern application of practice theory, Giddens and Bourdieu, seemed to ignore their own practice approach when discussing consumption. This was particularly so for Giddens (1991), who attributed most agency to individuals and intended action in his discussion of lifestyle, but also Bourdieu (1984) focused more on habitus and capital than practice in his most famous work on consumption, Distinction (Warde 2005). In consumption research, sociologists such as Alan Warde and Elizabeth Shove have played prominent roles in advocating the practice shift, but the approach is currently being applied and developed across disciplines by a range of contemporary consumption researchers (Gregson et al. 2009; Gram-Hanssen 2011; Shove et al. 2012; Warde 2005, 2014; Sahakian et al. 2014). Consumption is not itself a practice, but almost all practices involve some sort of consumption, and consumption always happens as part of, as moments in, a practice (Warde 2005). In line with the overall goal of practice theory to transcend the structureagency dichotomy, the practice approach bridges a fundamental dualism in approaches to consumption; that between ‘consumers’ as dupes or sovereign agents. Whereas economic orthodoxy (and to some extent culturalist and post-modern approaches) conceptualises the consumer as a sovereign agent which actively makes calculated and rational decisions, Marxist and other radical approaches have tended to view the individual consumer as powerless in the encounter with structural forces (whether this is capitalism or other social structures). Indeed, from the perspective of practice approaches the very concept of ‘the consumer’ disappears (Warde 2005). As put by Warde (2005: 146): ‘The [practice] approach offers a distinctive perspective, attending less to individual choices and more to the collective development of modes of appropriate conduct in everyday life. The analytical focus shifts from the insatiable wants of the human animal to the instituted conventions of collective culture, from personal expression to social competence, from mildly constrained choice to disciplined participation. […] the key focal points become the organization of the practice and the moments of consumption enjoined. Persons confront moments of consumption neither as sovereign choosers nor as dupes.’ Practice theory is thus a competing approach to both the methodological Arve Hansen / Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vol 3, No 2 (2017) 171-186 individualism of economic approaches and the emphasis on cultural expressivism in cultural approaches, focusing on routine rather than action, doing rather than thinking, the material rather than the symbolic, and ‘embodied practical competence over expressive virtuosity in the fashioned presentation of self’ (Warde 2014: 286). As already indicated above, this involves a broadening of the concept of agency, what Wilhite (2008) conceptualises as ‘distributed agency’, including people (and bodies), social context and material context (Wilhite 2009, 2012; Sahakian et al. 2014). In contexts of rapid economic development, I argue that such an approach should be combined with an analysis of larger scale development process, and particularly the role of the state. Development, the state and consumption In development research, consumption seldom enters the debate apart from as a poverty indicator (lack of consumption), as a measurement of inequality (in some versions of the GINI index) or as overall demand. In macroeconomic analysis consumption is usually approached through its function as forming part of the overall demand in an economy (along with investment and government expenditure), and as the alternative to saving (which is seen as postponed consumption). Although there have been different interpretations of the primacy of consumption versus production, from the classical economic belief in Say’s Law (production creates its own demand) to Keynes’ focus on stimulating aggregate demand, there is no disagreement to the fact that consumption is a necessary part of the economy. No matter from which perspective it is approached, it is obvious that production requires consumption, since 175 without it a capitalist economy ends up in a crisis of overproduction or stagnation. In development research, the role of the state frequently represents the starting point for academic inquiry. In consumption research, however, the state is rarely given a prominent position (Sanne 2002). The state is crucial for processes of economic development on arguably all scales. In a globalising (and regionalising) world economy states are ‘containers’ of distinct institutions and practices, as well as international competitors and collaborators (Dicken 2015). Nationally, state policies to various extents influence everything from the functioning of the economy to everyday life. The state’s influences on consumption could thus be approached in a variety of ways. Government policies are crucial for achieving developmental success as well as for distributing the gains from development. The level of welfare provided by the state furthermore strongly influences the capacity of its citizens to consume beyond subsistence. The state can in many ways be considered as what Myrvang (2009) has called ‘consumption agents’. In capitalism, the overall national economy benefits from, and indeed depends on, increasing levels of consumption. The capitalist state can aim policies towards shifting consumption (e.g. away from tobacco or alcohol), but will rarely, if ever, aim to reduce overall levels of consumption, since this would negatively affect the national economy through declining aggregate demand (and be bad for popular support). This is a fundamental difference between an economy based on delivering ‘enough’ goods to the population (such as Vietnam before doi moi) and one where the expansion of production and consumption is fundamental to the ‘health’ of the economy. It is widely agreed that to 176 Arve Hansen / Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vol 3, No 2 (2017) 171-186 create sufficient domestic demand, a significant middle class of consumers is necessary. 3. Doi moi and the socialist middle classes ‘Middle class’ is an elusive and slippery category, and one that is frequently highly imprecisely used in contexts of development (Birdsall 2014). A transition context makes matters even worse. Contemporary Vietnam clearly is home to large and often intersected classes of peasants and workers. While neat classifications of these are hard due to the frequency of temporary migration and seasonal jobs, the elites and middle classes are often even harder to pin down. As Gainsborough (2010) has highlighted, it is often difficult to distinguish the private from the public sector in Vietnam. As he puts it, both the bourgeoisie and the salaried classes in Vietnam are still ‘very much of the system’ (Gainsborough 2010: 17). Furthermore, measurements of the middle class tend to use income as a starting point, but in Vietnam the large amounts of informal income sources complicate such measurements. The World Bank and the Ministry of Planning and Investment have recently categorised 10% of Vietnam’s population as ‘global middle class’ and about 55% as ‘emerging consumers’. These numbers are, as often is the case, based on consumption statistics. The people found within the first category spends more than 15 USD PPP per day, while the second spends between 5.51 and 15 USD PPP per day (World Bank and Ministry of Planning and Investment, 2016). Interestingly, in these statistics there is no room for an upper class. This is nevertheless a clear improvement from earlier publications were international organisations have labelled anyone earning or spending more than 2 USD per day as middle class (Birdsall 2014). Yet, numbers like these remain disputed. Our ability to measure consumption expenditure accurately is limited, and it is also questionable to what extent middle classes can be captured by quantifications of income or consumption. Entering a detailed discussion about numbers and measurements is beyond the scope of this paper. What we know for certain is that the middle class in Vietnam is rapidly expanding; it is indeed considered the fastest growing in Southeast Asia (Huong Le Thu 2015), of course also due to a low starting point. I furthermore argue that we should be using the plural form and talk about middle classes. Clearly, there is no uniform group of people hiding behind this expanding social segment. At least we can divide them into two groups, the upper middle classes and the lower middle classes. Of course, we could further divide them depending on cultural and economic capital, as Bourdieu (1984) would have, but I will leave that out for now. Instead, I will consider some of the consumption patterns that define this new consumer segment of Vietnam’s society, as well as what political economic and ideological shifts that have been necessary to create them. 4. Consuming doi moi Through opening for foreign investments and liberalising trade, doi moi has obviously led to dramatic changes in the availability of goods in Vietnam, and consumption of a wide range of commodities has increased rapidly (Belanger et al. 2012). This has been well documented by Vietnam’s General Statistics Office (GSO) through their biannual publication of the Household Living Standard Survey. Table 1 captures Arve Hansen / Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vol 3, No 2 (2017) 171-186 177 the rapid changes in consumption of a range of technological appliances among Vietnamese households. The table neatly captures one of the most discernible manifestations of ‘development’ to most people: the improved access (due to availability and income) to goods. It shows the rapid expansion of especially motorbike, telephone and TV ownership, but also significantly increased ownership of refrigerators and video players, as well as to some extent of washing machines and water heaters. The table furthermore reveals the uneven development between rural and urban areas. These numbers are averages, and are of course tilted by the fact that some households own a lot of goods. Some wealthy households in the cities own several cars and 5-6 motorbikes, while other household own none. Transport indeed represents a particularly interesting consumption domain, and one that has even been suggested as an appropriate way to capture middle classes globally. As Huong Le Thu (2015: 7) explains, in vernacular Vietnamese belonging to the middle class is often expressed as ‘having enough to eat, enough to save’. If we were to be more accurate in using material possessions as a starting point for defining the Vietnamese class system, which commodities should we use? In one of the many attempts to capture the global middle class, Dadush and Ali (2012) have suggested ‘the car index’ as an appropriate tool, measuring the middle class in a given country through the number of cars in circulation. For the case of India, Krishna and Bajpai (2015) also use a car approach and argue that in a context of fluctuating income and expenditures, assets represent a more reliable base for classification than income. They furthermore find that transportation assets hold a special position as markers of status groups due to their capacity to limit or enhance individual’s ‘ambit of operations’ (Krishna et al. 2015: 71). They argue that in India those able to 178 Arve Hansen / Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vol 3, No 2 (2017) 171-186 possess a motorbike broadly fit into the category of lower middle class, while those able to afford a car fit into the upper middle class. This is an original (yet crude) starting point for thinking about class, and one that I believe holds some potential also in contemporary Vietnam. As Truitt (2008: 4) has argued in her analysis of motorbikes in Ho Chi Minh City: in Vietnam ‘it is in traffic that one sees the emergence of the middle class’. I believe this to a large extent still holds true, but while Truitt saw the middle class as those owning motorbikes, the car is perhaps a more accurate marker today. While estimates for China and India find good matches between cars and the size of the middle class (Dadush et al. 2012; Krishna et al 2015), however, Vietnam’s comparatively low number of cars (approximately two million in 2013 according to OICA (2014) estimates) would make the middle class quite small. Using Dadush and Ali’s method of car per household, the Vietnamese middle class would include between seven and eight million people while other estimates count it to 12 million (Huong Le Thu 2015).2 Furthermore, in Vietnam’s ‘motorbike society’ we cannot let go of the motorbike so easily. Among my car-owning informants, very few had got rid of their motorbikes. There are however clear differences in the type of motorbikes that are driven. Vietnamese consumers’ appetite for ‘premium’ motorbike models is considered extraordinary, something that led Italian manufacturer Piaggio to use Vietnam as a base for manufacturing their different 2 The car index includes multiplies the number of cars on the road with average household size (Dadush and Ali, 2012). Vietnam is home to around two million cars and the average size of a Vietnamese household was 3.8 (and rapidly declining) in 2009 (Guilmoto and de Loenzien, 2015). Piaggio and Vespa models for the Southeast Asian market (Interview with Piaggio Vietnam representative, November, 2013). Despite costing several times the price of their competitors, Piaggio has been a remarkable success in Vietnam (Wunker 2013; Hansen 2015c). I would argue that the Piaggio is another obvious material proof of membership in the well-off strata of post-doi moi Hanoi. Nevertheless, car ownership can certainly help identify the upper and upper middle classes in contemporary Vietnam, and who is able to purchase a car in Hanoi and how they manage to muster the financial ability to do so, can provide important insights into contemporary Vietnamese society. 4.1. Who are the Hanoian car owners? A car is undoubtedly still a luxury commodity in Vietnam. With a wide range of taxes and fees, purchasing a car is far out of range for the vast majority of Vietnamese people. Although it may be possible to acquire a used car for 200-300 million VND, a new car usually starts at more than 500 million. A new Toyota, one of the most popular brands in Hanoi, will often cost closer to 1 billion. By comparison, a new Honda motorbike is available for less than 20 million VND (although the most expensive Piaggio models cost several hundred million). Moreover, using a car is very expensive. Expenses such as fuel, parking, insurance, and road fees added up to between 3 and 10 million a month for my car-owning informants. The expenses for just using a car one month thus often exceed the monthly income of the average worker. Beyond the upper class of ‘super rich’, I have found that those who are able to own a car in Hanoi can broadly be considered to belong in the two groups Gainsborough (2010) has located as the middle class in Arve Hansen / Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vol 3, No 2 (2017) 171-186 Vietnam: high-ranking professional state employees and professional Vietnamese employed by foreign companies or aid institutions. Businessmen obviously belong to the middle class, and constituted a significant part of my car-owning informants. By businessmen I refer to those employed in foreign firms, or run their own small firms. They work in the new market economy, as part of usually regional or global firms, and many of them are, as this social segment often is across the world, very conscious of appearance. Many of the businessmen I interviewed were open about how they used their cars as strategies of distinction, for displaying their success in the market economy in order to achieve further success. They explained in detail that they needed relatively expensive cars to show potential and existing business partners that they were successful members of the market economy (Hansen 2016b). The large group of (relatively) high-ranking state employees are interesting, as is discussed below. Clearly, there is a strong overlap between the two groups. And the higher up you get in the public sector hierarchy, the stronger the link is also to the capital owning classes. Many use public positions mainly as a springboard to better private business opportunities. This overlap between the private and public sectors is common in transition economies, particularly where economic transition has not been accompanied by political transition, such as in Vietnam and China (Li 2010). The higher the public ranking the higher is also the access to informal sources of income. 179 4.2. Poor people with lots of money: The public-private middle class Although displaying wealth has become accepted in contemporary Vietnam, sources of income can still be a sensitive topic. For example, the sources of the wealth of socalled dai gia, or new rich, is subject to controversy. As put by a young female anthropologist in Hanoi: ‘The transition of Vietnam has made many people suddenly become rich with money falling from the sky but not from their effort and capability’ (Interview, May 2013). Relatedly, a marketer for a large, foreign auto company in Hanoi commented: ‘demand is very high on cars now. We usually make [a] joke: Vietnam is a very poor country but we have the best and the most beautiful cars in the world. People are very poor but they have a lot of money’ (Interview, October 2013). The comment on poor people with lots of money takes us back to my two groups of car owners. It is no big surprise that businessmen and other private professionals can own a car. Incomes in the foreign sector are often significantly higher than in the rest of the economy. In the public sector, however, even high-ranking officials earn about five million VND a month. A young female public employee raised my question herself: Do you wonder why people have so much money even though they don’t have money? […] Do you question how a poor country can have lots of people with cars? (Interview, May, 2013, translated from Vietnamese) As she was driving a car, she was concerned I would think they were ‘breaking the law’, but explained that this was not the case. In her case, her husband who was ‘doing business’ had bought the 180 Arve Hansen / Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vol 3, No 2 (2017) 171-186 car.3 Other informants were more cryptic. In an interview with two senior, male state employees, I was told that they earned a few hundred dollars a month but still bought expensive cars. Their expenses for just using the car were equivalent to their income, they explained. The highest ranking of the two was quite serious and said that it was just about ‘extra jobs’. The other laughed, put on a funny smile and said that even doctors did not have the salary to afford a car. He showed his new smart phone and explained that it cost him two months’ salary. He laughed again and said he had not eaten for those two months. They ended up explaining that as high ranking state employees they have other sources for income, and the highest ranking of them returned to saying that they take on many different jobs, like being involved in consultancy with international organisations. They explained that the government paid their salary even though they were doing other jobs, and that they were probably allowed to work ‘two thousand percent’ outside their formal positions (Interview, April, 2013). The last point is relevant for all of the car-owning informants employed in the public sector. They all reported to have extra income, and some of them ran private businesses that occupied large portions of their time. In another interview, when asking a young female professional who she thought could own a car in Vietnam today, she giggled and answered that ‘it’s difficult to say, because, you know, here, income doesn’t come from your job’ (Interview, October, 2013). Her father had bought the car for her, which was a common statement 3 Quite typical for the Confucian patriarchal gender relations of modern Vietnam (see Drummond and Rydstrom, 2004), most car owners in Hanoi are men. Even though women are to an increasing extent driving cars, men usually own the vehicles. among my younger informants. Getting closer to what is probably an important part of the truth, a young and obviously wealthy businessman laughed out loud when asked how government officials and other state employees can afford a car. He said that ‘In Vietnam, being a government official is like being a businessman. Your money is like someone in business. So you can have different kinds of income’. He explained that they have the right to decide who will be promoted, as well as the fact that they receive money from a range of different sources. ‘If other people earn money, they can share it with government officials.’ ‘Commission’, he added (Interview, May, 2013). This statement reflects the rather well-known fact that personal connections and money can get you more or less anything in today’s Vietnam. In the Leninist political structure and state-influenced economy, who you know certainly matters much more than what you know. This fact is also clearly visible in the market for ‘lucky numbers’ (so dep, literally beautiful numbers). Getting a nice license plate brings luck and represents a significant status symbol in Hanoi (Hansen 2016b). However, for cars, buying and selling lucky numbers is illegal. Instead they are randomly drawn at the registration office by pushing a button. Still, there are ways of getting around this system, and the response by young, female car owner (who was lucky and got a license plate adding up to the number nine) is a telling example: Author: Did you choose to get a lucky number? Informant: You cannot choose it! You get it randomly. Author: But I think some people still manage to? Informant: Ah, yeah, yeah, if you have a lot of money. And relationship. Arve Hansen / Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vol 3, No 2 (2017) 171-186 (Interview, October, 2013). In one of my interviews with a car retailer, the process of obtaining a lucky license plate was explained to me in detail: Informant: Actually the government restricts the selling of numbers, so you have to push the button. But you can do another way, it depends on relationship and money. Here if the customer ask we can help them. [Laughter] We know somebody so we can go to the place for registering, ask them to come out and give them some money. So we still just press the button, but it will give us the number we want. [Laughter] Author: And how much does it cost? Informant: It depends on the number and the relationship. It’s more difficult now. We cannot use a fixed price, it’s unfixed price. If you want to know the price, just ask God. [Laughter] (Interview, April, 2013, translated from Vietnamese). The important role of political connections as well as the significant amounts of informal income also resonate with Vu’s (2014: 31) findings concerning ‘selling of office’ as one of the most serious forms of corruption in Vietnam today and how party officials can make fortunes by ‘selling state positions to the highest bidders’. Vu is discussing very high-ranking officials, but from my own observations this is prevalent across the public sector. For the case of transport, an interesting example is that it according to several informants is possible for traffic police to buy a lucrative spot in the streets. This gives a relatively low salary, but very high opportunities for easy money in the pocket. It is generally known in traffic in Hanoi that the police can stop you without necessarily having a very good reason, and that they will always find a 181 reason to give you a fine. In order to avoid having to go through a time-consuming process to pay the fine, where the vehicle is often kept by the police until the fine is paid, people rather ‘pay the fine directly’ to the officer, usually including a bribe. The standard ‘fine’ seems to be 200.000-300.000 VND on a motorbike, often significantly higher if driving a car. My car-owning informants reported that the fines they had to pay to the police were often more than twice as high in a car compared to on a motorbike. According to many of my informants the exception is if the car looks particularly luxurious, perhaps even with an expensive license plate. Then the police would usually not stop it. Although an expensive car could signify a profitable ‘client’ to the police, it also means that its driver probably has very powerful political connections. Nevertheless, the point here is that public sector employees despite low salaries use a variety of legal and illegal ways of generating enough financial capacity to participate in consumption practices-including owning a car-that qualifies for middle class categorisation. The main point, as I have discussed in several publications (Hansen, 2015bc, 2016bc, 2017), is that a growing number of people can afford a car in Vietnam today, and that the private car has emerged as a ‘must-have’ object in among certain social segments. Drawing on Bourdieu (1984), we could say that people drive cars to belong to the middle class, while belonging to the (upper) middle class comes with expectations of automobility. And crucially, this is not necessarily about displaying status, it also concerns generally higher expectations to comfort, convenience, and safety. No matter the reasons, however, car ownership is rapidly increasing in Vietnam, 182 Arve Hansen / Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vol 3, No 2 (2017) 171-186 and the country is now considered among the fastest growing car markets in the world (Saigoneer 2017). 5. Consumption, development and doi moi The case of cars is perhaps the most visible one, but a wide range of consumer goods are relevant for understanding the Vietnamese middle classes today. Private consumption arguably represents one of the clearest shifts away from the planned economy in Vietnam. While able to produce large number of goods, history has shown that socialist economies have tended to include ideological limitations on what an individual should consume. With doi moi the official position towards private consumption has changed from limitations to encouragement (Vann 2012; Huong Le Thu 2015). From a macro-economic perspective, this of course makes perfect sense. While a planned economy usually focuses on producing and delivering enough goods to people, a market economy fundamentally depends on growth, and thus on increasing levels of consumption (Wilhite et al. 2015). With reforms, widespread ownership of goods beyond strict necessities thus had to be accepted, and in time even the consumption of luxury goods appears to be considered as beneficial for the road to socialism in Vietnam. The market reforms have surely involved more than strictly economic measures. Although there has been no political transition in Vietnam, the socio-political changes in terms of relative economic freedoms and the official position towards commodities have been radical. The social and indeed political meanings of consumer goods have changed drastically. As Vann (2012) argues, in a country ruled by a communist party and with little freedom of speech or media, consumption has represented the strongest sense of liberty brought along by doi moi. The reforms have led to a new acceptance of consumption and display of wealth, and those who can afford it are now able purchase and display consumer objects that would surely be judged as bourgeois excess not long ago. Let us return to motorised transport. Spreading so rapidly and becoming so integral to everyday life in Vietnam, motorbike ownership quickly became fairly uncontroversial. A private car, however, is in many ways a more conspicuous object. As Broz and Habeck (2015) note on the dual role of cars in the Soviet Union, cars have from a socialist perspective historically represented suspicious items with connotations of individualism and consumerism rather than socialist progress (Siegelbaum 2008). Similarly, a hotly debated topic in China after market reforms was whether the Chinese auto industry should support what was considered bourgeois consumption patterns by producing cars for private use (Notar 2017). Some of my informants recalled that even as late as the 2000s high-ranking public servants would avoid purchasing a car due to the signals a private car sent about its owner (probably of both corruption and extravagance). They stressed that this was a thing of the past and that people now were rather afraid of buying a car for more practical reasons such as high costs and lack of parking space (Hansen 2016c). The signals a car sends can however still influence the type of car purchased. One relatively high-ranking public servant I interviewed stressed how people in the private sector want to show that they are rich, even if they in reality are not, and if Arve Hansen / Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vol 3, No 2 (2017) 171-186 they do not own a car they will borrow one and display it as their own. Conversely, he argued, government officials are rich but do not want to show it, and will thus adopt a more careful approach to car consumption (Interview, April 2013). Nevertheless, both the economic and political elites (with their considerable overlaps) in Hanoi are increasingly found within the confines of a private automobile. Similarly, it is now generally accepted to spend large amounts of money on clothing, food, alcohol, housing and a wide range of consumer products. Meanwhile, the symbolic meaning of goods are continuously negotiated and changing. And apart from certain categories, such as cars, housing and restaurants, it is hard to generalize what exactly are middle class consumption patterns in Vietnam today. Within the middle classes there are many different categories. In line with Bourdieu’s (1984) argument in Distinction, what is considered appropriate within the subgroups high on economic capital may not be considered appropriate within the subgroups high on cultural capital. In the latter too conspicuous consumption is often frowned upon, while at the same time more subtle ways of conspicuousness are integral to cultural middle-classness. What is nevertheless certain is that goods play a decisive role in defining class in Vietnam today. Furthermore, everyday practices get more consumption intensive. This is similar in processes of economic development and increasing affluence around the world. The exact ways that this plays out, however, are usually highly context specific. Nevertheless, the more consumption and thus resource intensive practices carry with them higher ecological footprints. At the same time, however, parts of the Vietnamese middle classes are 183 becoming increasingly environmentally conscious. Buying green products, riding (often very expensive) bicycles and even turning vegetarian are new trends that may hold some promise of greener lifestyles. Lessons from other countries do however show us that we can expect these to be ‘compensated’ by other carbon intensive practices, such as car ownership, in general more shopping of for example clothing, and more frequent holidays involving longer flights. For Vietnam, the expanding middle classes lead to a growing domestic market and a more dynamic domestic economy. At the same time, however, they come with higher expectations of material wellbeing and potentially of political rights, although for the latter seemingly to a lesser extent than what conventional theory tells us (see Gainsborough, 2010; or Chen 2013 for a similar discussion on China). The consumption patterns of the higher end of the middle classes, together with those of the elites, are simultaneously very visible manifestations of the social inequalities embedded in the post-doi moi economy and society. How the government deals with this situation within the context of the socialist market economy will represent a fascinating venture for further social scientific research. 6. Conclusions Investigating the middle classes in the context of Vietnam’s attempt to find an alternative development model remains a rather understudied aspect of Vietnam’s transformations. This paper has discussed how not only the economic changes but also ideological softening has been necessary for the middle-class consumption patterns we see today. The paper mainly used the private car as a starting point for the discussion, 184 Arve Hansen / Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vol 3, No 2 (2017) 171-186 showing how owning a car, maybe the most conspicuous consumer item of all, only in the recent decade became an accepted part of Vietnamese aspirations. Accepting high levels of private consumption is a necessary part of a market economy, and the question now is to what extent Vietnam’s new development model can bring about more sustainable consumption patterns than in the rich countries (and if so, how), as well as how to deal with the deep inequalities that are so visibly manifested by the consumption patterns of the upper middle class and the elites in Vietnam today. References Bélanger, D., Drummond, L. B. W., & NguyenMarshall, V. 2012. Introduction: Who Are the Urban Middle Class in Vietnam? In V. Nguyen-Marshall, L. B. W. Drummond, & D. Bélanger (Eds.), The Reinvention of Distinction: Modernity and the Middle Class in Urban Vietnam. Dordrecht: Springer Beresford, M. 2008. "Doi Moi in review: The challenges of building market socialism in Vietnam". Journal of Contemporary Asia, 38 (2), 221-243. Birdsall, N. 2014. Who You Callin’ Middle Class? A Plea to the Development Community. Retrieved from http://www.cgdev.org/blog/who-youcallin%E2%80%99-middle-class-pleadevelopment-community Bourdieu, P. 1984. Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Broz, L., & Habeck, J. O. 2015. Siberian Automobility Boom: From the Joy of Destination to the Joy of Driving There. Mobilities, 10 (4), 552-570. doi:10.1080/17450101.2015.1059029 Chen, J. 2013. A Middle Class without Democracy: Economic Growth and Prospects for Democratization in China. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Dadush, U., & Ali, S. 2012. In search of the global middle class: A new index. Washington DC: Brookings Institution. Dicken, P. 2015. Global shift: mapping the changing contours of the world economy. Los Angeles: Sage. Douglas, M., & Isherwood, B. 1979. The world of goods. New York: Basic Books. Drummond, L. and Rydstrom, H. 2004. Gender Practices in Contemporary Vietnam. Copenhagen: NIAS Press. Gainsborough, M. 2010. Vietnam: Rethinking the state. London: Zed Books. Giddens, A. 1991. Modernity and self-identity. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Guilmoto, C. Z., & de Loenzien, M. 2015. Emerging, transitory or residual? One-person households in Viet Nam. Demographic Research, 32, 1147-1176. Gram-Hanssen, K. 2011. "Understanding change and continuity in residential energy consumption". Journal of Consumer Culture, 11 (1), 61-78. Gregson, N., Metcalfe, A., & Crewe, L. 2009. "Practices of Object Maintenance and Repair: How consumers attend to consumer objects within the home". Journal of Consumer Culture, 9 (2), 248-272. Gronow, J., & Warde, A. 2001. Ordinary consumption. London: Routledge. Hansen, A. 2016a. Capitalist transition of wheels: Development, consumption and motorised mobility in Hanoi, PhD thesis, University of Oslo. Available online: https://www.duo.uio.no/handle/10852/52717 Hansen, A. 2016b. Hanoi on Wheels: Emerging automobility in the land of the motorbike. Mobilities. doi: 10.1080/17450101.2016.1156425 Hansen, A. 2016c. Driving Development? The Problems and Promises of the Car in Vietnam. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 45 (4), 551569. Hansen, A., & Wethal, U. 2015. Emerging Economies and Challenges to Sustainability. In A. Hansen & U. Wethal (Eds.), Emerging Economies and Challenges to Sustainability: Theories, Strategies, Local Realities. London and New York: Routledge. Arve Hansen / Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vol 3, No 2 (2017) 171-186 Hansen, A. 2015a. The best of both worlds? The power and pitfalls of Vietnam's development model. In A. Hansen & U. Wethal (Eds.), Emerging Economies and Challenges to Sustainability: Theories, Strategies, Local Realities. London and New York: Routledge. Hansen, A. 2015b. "Transport in transition: Doi moi and the consumption of cars and motorbikes in Hanoi". Journal of Consumer Culture. doi:10.1177/1469540515602301 Hansen, A. 2015c. Motorbike Madness? Development and Two-Wheeled Mobility in Hanoi. Asia in Focus, 2, 5-13. Hansen, A. 2017. Doi moi on two and four wheels: capitalist development and motorised mobility in Vietnam, In A. Hansen & K.B. Nielsen (Eds.), Cars, Automobility and Development in Asia: Wheels of change. London: Routledge Huong Le Thu. 2015. The Middle Class in Hanoi: Vulnerability and Concerns. ISEAS Perspective # 8, Singapore: ISEAS. JDPR [Joint Development Partner Report] (2012). Vietnam Development Report 2012: Market Economy for a Middle-Income Vietnam. Hanoi: World Bank. Kharas, H., & Gertz, G. 2010. The New Global Middle Class: A Cross-Over from West to East. In C. Li (Ed.), China's Emerging Middle Class: Beyond Economic Transformation. Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press. Krishna, A., & Bajpai, D. 2015. Layers in Globalising Society and the New Middle Class in India. Economic and Political Weekly, L (5), 69-77. Li, C. 2010. Introduction: The Rise of the Middle Class in the Middle Kingdom. In C. Li (Ed.), China's emerging middle class: Beyond economic transformation. Washington, D.C: Brookings Institution Press. Malesky, E. and London, J. 2014. ‘The Political Economy of Development in China and Vietnam’. Annual Review of Political Science, 17, 395-419. Masina, P. 2006. Vietnam's development strategies. Oxon UK ; New York: Routledge. Masina, P. 2012. Vietnam between Developmental State and Neoliberalism: The Case of the Industrial Sector. In C. Kyung-Sup, B. Fine, & L. Weiss (Eds.), Developmental 185 Politics in Transition: The Neoliberal Era and Beyond. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan McNeill, D., & Wilhite, H. 2015. Making sense of sustainable development in a changing world. In A. Hansen & U. Wethal (Eds.), Emerging Economies and Challenges to Sustainability: Theories, Strategies, Local Realities. London and New York: Routledge. Myrvang, C. 2009. Forbruksagentene: Slik vekket de kjøpelysten. Oslo: Pax Forlag. Notar, B. 2017. Car Crazy: The Rise of Car Culture in China. In A. Hansen & K.B. Nielsen (Eds.), Cars, Automobility and Development in Asia: Wheels of change. London: Routledge. OICA 2014. Vehicles in use. http://www.oica.net/category/vehicles-in-use/ Sahakian, M., & Wilhite, H. 2014. "Making practice theory more practicable: Towards more sustainable forms of consumption". Journal of Consumer Culture, 14 (1), 25-44. Saigoneer. 2017. ‘Vietnam has world’s second fastes growing car market’. http://saigoneer.com/vietnam-news/9375vietnam-has-world-s-second-fastest-growingcar-market Sanne, C. 2002. Willing consumers-or locked-in? Policies for sustainable consumption. Ecological Economics, 42, 273-287Shove, E. (2003). Comfort, cleanliness and convenience: the social organization of normality. Oxford: Berg. Shove, E., Pantzar, M., & Watson, M. 2012. The dynamics of social practice : everyday life and how it changes. Los Angeles: Sage. Siegelbaum, L. H. 2008. Cars for comrades: The life of the Soviet automobile. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Truitt, A. 2008. On the back of a motorbike: Middle-class mobility in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. American Ethnologist, 35 (1), 3-19 UNDP. 2013. Human Development Report 2013: The Rise of the South: Human Progress in a Diverse World. New York: UNDP. Van Arkadie, B., & Mallon, R. 2003. Viet Nam: A transition tiger? The Australian National University: Asia Pacific Press. Vann, E. F. 2012. Afterword: Consumption and Middle-Class Subjectivity in Vietnam. In V. Nguyen-Marshall, L. B. W. Drummond, & D. Bélanger (Eds.), The Reinvention of 186 Arve Hansen / Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vol 3, No 2 (2017) 171-186 Distinction: Modernity and the Middle Class in Urban Vietnam. Dordrecht: Springer. Veblen, T. 2005. [1899]). The theory of the leisure class : an economic study of institutions. Delhi: Aakar Books. Vu, T. 2014. Persistence Amid Decay: The Communist Party of Vietnam at 83. In J. London (Ed.), Politics in Contemporary Vietnam: Party, State, and Authority Relations (pp. 21-41). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Warde, A. 2005. "Consumption and Theories of Practice". Journal of Consumer Culture, 5 (2), 131-153. Warde, A. 2014. After taste: Culture, consumption and theories of practice. Journal of Consumer Culture, 14(3), 279-303. Wilhite, H. 2008. New thinking on the agentive relationship between end-use technologies and energy-using practices. Energy Efficiency, 1 (2), 121-130. Wilhite, H. 2009. The conditioning of comfort. Building Research & Information, 37 (1). Wilhite, H. 2012. Towards a better accounting of the roles of body, things and habits in consumption. In A. Warde & D. Southerton (Eds.), COLLeGIUM: Studies across Disciplines in the Humanities and Social Sciences: The Habits of Consumption (Vol. 12). Helsinki: Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies Wilhite, H., & Hansen, A. 2015. Reflections on the meta-practice of capitalism and its capacity for sustaining a low energy transformation. In C. Zelem & C. Beslay (Eds.), Sociologie de l'énergie: Gouvernance et pratiques sociales. Paris: CNRS Editions. World Bank and Ministry of Planning and Investment. 2016. ‘Vietnam 2035: Toward Prosperity, Creativity, Equity, and Democracy’. Washington DC: World Bank. Wunker, S. 2011. How the Vespa became Vietnamese. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/stephenwunker/20 11/11/08/how-the-vespa-became-vietnamese/