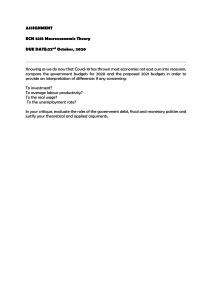

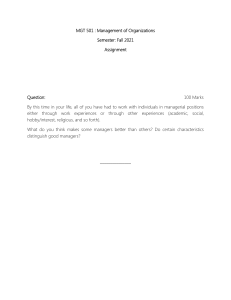

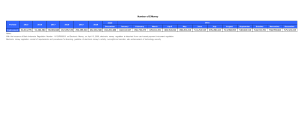

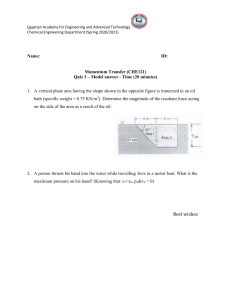

HBP# CMR771 California Management Review 2021, Vol. 63(4) 5–26 © The Regents of the University of California 2021 Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions https://doi.org/10.1177/00081256211025823 DOI: 10.1177/00081256211025823 journals.sagepub.com/home/cmr rP os The Blinkered Boss: t Management HOW HAS MANAGERIAL BEHAVIOR CHANGED WITH THE SHIFT TO VIRTUAL WORKING? op yo Julian Birkinshaw1, Maya Gudka1, and Vittorio D’Amato2 tC SUMMARY Virtual working became the norm for most organizations since March 2020, and it brings well-recognized challenges. But we know little about the impact of virtual working on managerial behavior. This article presents the results of three surveys conducted before and during lockdown to understand what changed. It shows how managers became more blinkered: turning inward, becoming task-focused at the expense of relationship-building, and finding few opportunities to develop new skills. The article offers practical suggestions for how the evolution of managerial work might be accelerated, so that managers can become more effective in this changing environment. KEYWORDS: managers, managerial behavior, managing subordinates, virtual environments, developing employees W No ith the onset of the Covid pandemic in March 2020, most professional and knowledge workers began working from home and had to adapt to a different rhythm and style of work. Many firms, including Google, Microsoft, and Siemens, quickly committed to making the “flexible workplace”1 a permanent feature of their operating model. In part, this was driven by necessity, but also by the success of virtual working. Studies indicated good outcomes in terms of worker productivity and job satisfaction.2 Do The challenges of virtual working are reasonably well understood. Studies have emphasized the loss of “water cooler” moments, the limitations of videoconferencing for creative or spontaneous work, and the lack of joie de vivre when work is conducted from home.3 1London Business School, London, UK 2Università Cattaneo, Castellanza, Italy 5 This document is authorized for educator review use only by LYONEL LAULIÉ, Universidad de Chile until Aug 2021. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860 6 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW 63(4) rP os t However, we know little about the impact of the virtual environment on managerial behavior—how those in line-management positions think and act, how they get things done, and how they get the best out of the people working for them.4 This is an important phenomenon, attracting considerable amounts of research interest since Henry Mintzberg’s pioneering research almost 50 years ago.5 However, that body of work was conducted largely in office environments. In this research, we therefore sought to understand how the nature of managerial work might have changed as the majority of people began working virtually. During the 2020 lockdown, we conducted a series of surveys looking at various aspects of the phenomenon. And to overcome the risk of retrospective sensemaking, we compared the findings to identical surveys done prior to March 2020, to help us identify areas where significant differences in behavior could be observed. op yo The evidence suggested managers were as motivated and committed to doing a good job as ever. But the virtual working environment appeared to have a deleterious effect on their effectiveness: they turned inward, they became taskfocused at the expense of relationship-building, and they found few opportunities to develop new skills. As alluded to in the title of this paper, they became more “blinkered” in their outlook. tC Of course, there were many examples of managers doing a good job, but the evidence suggested there were more who were struggling. Our interpretation of the findings is that the virtual working environment “exposes” managers to the challenging aspects of their work. Without the usual crutches afforded by office life—such as being able to monitor team members, or sense what’s happening through body language, or gossip in the restrooms—there is a tendency to shift toward “task mode” and act in a more narrow and controlling way. All of which is likely to be harmful to the morale and professional development of employees. No To the extent that virtual working becomes a normal—even dominant— mode of working in the years ahead, it is important for managerial work to continue to evolve, so that the problems identified above are addressed, and so that the potential benefits afforded by this new way of working are realized. There are opportunities for managers to change how they operate, and there are also opportunities for firms to rethink their structures and processes to enable managers to be more effective. This article finishes with some suggestions for how this process of evolution might be accelerated so that managers can become more effective in this new set of operating conditions. Do Background and Context The Co-Evolution of Management and Technology Many studies have sought to make sense of how the field of management has evolved. Over the last 150 years, there has been a broad shift from mechanistic to organic ways of working, mirroring the transition from the industrial to the digital age, and within this long-cycle trend there have been smaller iterations This document is authorized for educator review use only by LYONEL LAULIÉ, Universidad de Chile until Aug 2021. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860 The Blinkered Boss: How Has Managerial Behavior Changed with the Shift to Virtual Working? 7 rP os t back and forth between what Barley and Kunda call rational (emphasis on task) and normative (emphasis on people) management practices.6 In all these accounts of management evolution, technological progress has played an important role as a facilitator of change. For example, the invention of assembly line technology and mass production in the 1920s ushered in the tight control systems of Scientific Management; the early mainframe computers of the 1960s enabled the operations research movement and a period of strong functional control over management decision making; and the personal computer and cloud computing revolutions, from the 1980s on, facilitated a trend toward greater individual empowerment and more organic forms of coordination.7 tC op yo Viewed in this light, virtual working (i.e., where individuals work in different locations without ever having to meet) first became possible in the 1990s with the advent of the Internet, and only became fully effective (i.e., with high-quality videoconferencing and file-sharing technologies) over the last 5-10 years. Firms were experimenting with forms of virtual working earlier than this, typically under the label telecommuting or teleworking, but typically focusing on a narrow group of workers and tasks, and with mixed success.8 During the 2010s, virtual working grew in popularity, with a majority of large firms allowing it in some form, and around 20% of workers engaging in virtual working fairly frequently.9 However, the evidence around its benefits and costs was equivocal. One wellcited study of a Chinese firm, Ctrip, showed significant performance improvements following a work from home experiment, but it also noted fewer promotions for those working from home.10 Other studies had ambiguous and sometimes contradictory findings.11 Finally, it is worth noting that the Covid pandemic provided further impetus to studies of new work practices that had already been gathering pace.12 For example, studies have used the Covid context to re-examine important topics such as individual time management, coping mechanisms, patterns of communication, and leadership roles.13 No The Changing Nature of Managerial Work Linked to these broad shifts in how work gets done within organizations is a much narrower question: what is the nature of managerial work, and how is it changing over time? Do Again, it is useful to start with the early literature, for example, the writings of Henri Fayol, Luther Gulick, and Lyndall Urwick. In their view, management involved such activities as forecasting and planning, organizing, commanding, and controlling.14 This was the “Scientific Management” era of F.W. Taylor in which the manager’s job was “to take control over how and how fast workers would execute their tasks,” even though this led to “dysfunctional side effects, particularly in the form of high turnover and low worker morale.”15 In terms of their means of influence, managers emphasized their formal authority to coerce employees to act in certain ways, they used incentives (carrots and sticks), and they controlled the flow of information to their workers. This document is authorized for educator review use only by LYONEL LAULIÉ, Universidad de Chile until Aug 2021. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860 8 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW 63(4) rP os t This scientific management model was countered by the human relations movement, which started in the 1930s and grew into a wider culture and quality management movement in the 1960s and 1970s. These bodies of thinking emphasized the normative or people-centered aspects of organizations. And they advocated a very different role for those at the top: “enlightened managers were said to be capable not only of formulating value systems but of instilling those values in their employees.”16 op yo With the advent of computer technology, information was more widely shared among employees, thereby taking away one of the manager’s traditional sources of power, viz control over information flow. Employees were also better educated, with greater rights and freedoms in society more widely, so they were less likely to tolerate coercive behavior from their boss. As Mintzberg observed in the 1970s,17 managerial work was fragmented, multifaceted, and often hectic, as managers sought to cater to the interests of multiple stakeholders through mostly informal means of influence. The nature of managerial work evolved further during the modern era. Technological advances provided workers with immediate access to information and tools, so managers increasingly saw their role as supporting and coaching their employees, and facilitating coordination with others.18 This was made possible in no small part by having teams of people working in the same office, because managers could influence their subordinates through brief conversations, role-modeling, and a variety of other informal attention-channeling behaviors.19 No tC This brief sketch of how managerial work has evolved does not do justice to the complexity of the changes that have occurred,20 but it nonetheless provides some context to the global virtual working experiment underway since March 2020. While the formal roles and responsibilities of managers did not change, they faced new challenges in doing their job effectively, because many of the informal levers of influence noted above were not readily available. To the extent that virtual working becomes a normal feature of business life in the years ahead, we can expect managerial work to evolve further. The purpose of the research reported here is to offer some tentative suggestions about what it might look like. Research Methodology Do During the first wave of the Covid pandemic (April to August 2020), we conducted three related studies looking at different aspects of managerial work. In all three cases, the data were collected using survey instruments that we had used before, so we were able to explicitly compare how managers were behaving during “lockdown” to how they had behaved under normal office-based working conditions. The first study looked at the effectiveness of managers in their activities. It was conducted with a random sample of 315 managers in 2018, and then with a sample of 82 managers in August 2020. The sampling frame was people in managerial roles in knowledge-work sectors (education, marketing, media, accounting, This document is authorized for educator review use only by LYONEL LAULIÉ, Universidad de Chile until Aug 2021. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860 The Blinkered Boss: How Has Managerial Behavior Changed with the Shift to Virtual Working? 9 rP os t technology, science, finance, and the public sector) with university-level education. The survey asked respondents how effective they were in a wide range of managerial activities, such as analyzing the task environment, motivating employees, and decision making. The second study examined how managers spend their time, with an emphasis on why particular tasks or activities were chosen and how important they were. It was conducted through telephone interviews in June 2020, with 40 managers providing data on 264 specific activities. We then compared the findings to an earlier study conducted in 2013, to a comparable group of 45 managers, sometimes even the same individuals, who had provided data on 329 specific activities. The sampling frame was the same as above. op yo The third study focused on how managers learn and develop over time. There was an initial survey done in late 2019 with 497 managers (alumni from a leading business school) who answered questions on how effective they were in managing their own professional development. In August 2020, a subset of these individuals who had given permission for a follow-up were approached and 38 of them provided answers to the same questions for the lockdown period. tC In addition to these three surveys, we also conducted more than 20 interviews with respondents to gain qualitative insights into how their work had changed since March 2020. Below we report primarily on the quantitative data, with some qualitative insights included to provide context and explanation. Further details on the research methodology, including how the surveys were developed and how the data were analyzed, are provided in the appendix. Findings No We describe the findings from the research in three parts, in terms of how effective managers were in their various activities, how they spent their time, and how they enabled their subordinates and their own development over time. How Effective Are Managers in Their Various Activities? There are many ways to describe the work of management. Building on the existing literature, including studies by Henry Mintzberg, Charles Handy, and others,21 we divided management work into three broad sets of activities: Cognitive—analyzing and making sense of situations; • Task-Based—making things happen and delivering results; and Do • • People-Based—enabling and inspiring the efforts of others. It is worth noting that a bottom-up analysis of our data (through factor analysis) confirmed the validity of this threefold categorization. Figure 1 shows the ratings from our respondents in 2018 and 2020, respectively, in terms of how effective they believed themselves to be on each different This document is authorized for educator review use only by LYONEL LAULIÉ, Universidad de Chile until Aug 2021. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW 63(4) op yo rP os FIGURE 1. Effectiveness of management tasks in office and virtual workplaces. t 10 Note: Asterisks beside each activity indicate statistical significance of differences. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. activity. Significant differences are indicated using asterisks. The key insights from this analysis can be summarized as follows. No tC First, managers operating virtually rated themselves as highly effective on the cognitive aspects of their work (i.e., solving problems, making sense of things, and managing their own time). While these received among the lowest ratings in the office-based environment, they were the highest-rated in the virtual context. It makes sense that this type of analytical work is location-neutral; but as noted, already working virtually means fewer interruptions and therefore more opportunity to focus. Another possible explanation, suggested to us during the interviews, is that the virtual environment—especially during lockdown—encouraged greater personal reflection and legitimized introverted behavior. Do Second, respondents rated themselves as performing better on the task-oriented aspects of their work in the virtual environment, though some of these differences were significant and others were not. In our interpretation, this is consistent with the sense of urgency that many organizations felt during the summer of 2020, and it suggests that many aspects of the manager’s job can be done as well remotely as in person. “People are meeting their deadlines better” was one observation shared with us during the interviews. Third, the people-based aspects of management work were rated consistently and significantly lower in the virtual context. While fully aware of the importance of motivating and helping their subordinates, respondents rated their effectiveness as low—both relative to the equivalent ratings from 2018 and relative to the scores for the cognitive and task-focused domains of work. This document is authorized for educator review use only by LYONEL LAULIÉ, Universidad de Chile until Aug 2021. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860 The Blinkered Boss: How Has Managerial Behavior Changed with the Shift to Virtual Working? 11 rP os t Interviewees provided additional color on these points. “My relationship with team members has definitely suffered, because I have so much to deal with myself, I don’t make enough time to focus on that—there aren’t enough hours in the day,” was a typical comment. In terms of specific challenges, bringing new people into a team was unsurprisingly difficult in a purely virtual environment: “It has been so much harder to onboard my new team member . . . so many little things that would have been ironed out if she sat opposite me haven’t happened.” Managing poor performance was also more difficult given the reluctance to give negative feedback by video: “You cannot challenge a person so well over Zoom . . . you tend to hold back.” One respondent mentioned that performance reviews in their organization had been put entirely on hold during the first wave of the Covid pandemic, again because of the challenges of doing it well. op yo There were also low scores for innovation and creativity, which depend on interpersonal connections for their effectiveness.22 Consider this observation from one respondent: It’s a lot harder to create the kind of spontaneous discussion which results in ideas. I’ve tried to use WhatsApp to create more free discussions for each issue, getting groups of key people together on a particular problem. But then I’ve woken up to endless chats that I need to read through if I want to be able to contribute anything. It takes up far more energy. For an extrovert like me, I find the whole thing much harder than just being in the office and enjoying the energy of my team to create solutions. tC In sum, the picture that emerged from this analysis was a shift in emphasis toward personal reflection and task-based action, and away from the relational, employee-engagement narrative of recent decades. How Do Managers Spend Their Time, and Why? No Our second study took a more micro-level look at the specific tasks and activities managers engage in over the course of a working day. In Mintzberg’s seminal analysis of managerial work, managers worked “at an unrelenting pace” with “their activities characterized by brevity, variety, and discontinuity” and they were “strongly oriented to action” rather than undertaking reflective activities. In his original study, half of their activities lasted less than nine minutes, and only 10% exceeded one hour.23 Do While our quantitative analysis took a different approach to Mintzberg’s, it was clear from our interviews that this frenetic, multitasking approach to managing was not being replicated in the virtual working environment. While managers were spending large amounts of time on Zoom calls, they were often more than an hour in length and rarely less than 30 minutes. Mintzberg noted that 93% of the verbal contacts made by managers in his study were ad hoc, whereas managers we interviewed observed—unsurprisingly—that most of their conversations with colleagues were scheduled in advance. Here is how one senior manager stayed up to date with his team: This document is authorized for educator review use only by LYONEL LAULIÉ, Universidad de Chile until Aug 2021. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860 12 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW 63(4) op yo rP os t FIGURE 2. How managers spend their time. Every day I make calls to five or six people in the office at random, so I can check in with everyone (almost 100 people) every three weeks . . . I used to be able to do that in just a couple of days. There is, in other words, a greater amount of structure in the manager’s working day when operating virtually, and this has both benefits (fewer interruptions) and costs (the short, spontaneous conversations are lost). One respondent recalled how he missed the informality of some of his dealings with his manager: tC The only thing that is lost [in virtual working] is when your boss pops his head around the door and you can tell him what you’re working on casually without it seeming like you’re making a big show of it. No The quantitative analysis drilled down on the specific tasks and activities managers spent their time on, categorizing these activities by the people they were interacting with (boss, subordinates, colleagues, external clients, themselves). It is presented in Figure 2 and Table 1 and can be summarized in two key observations. First, managers working virtually were spending significantly less time in internal meetings with colleagues and significantly more time on externally facing activities such as with clients. This might suggest they were becoming more efficient in their use of time, in that they were being more discerning about the meetings they chose to take part in. One respondent said, “I have to say, many members of my team are hugely productive at home, and it seems to really be suiting them.” Do Second, and perhaps more surprising, managers saw their work—and their own role—as more essential in the virtual setting. For example, managers rated 78% of their activities as essential or important in 2020, compared with 56% in the earlier study; and when asked if there was scope for delegating or outsourcing to others, they said 72% of their work in 2020 could only be done by them, compared with 58% before (Table 1). All these differences were statistically significant (p < .01). This document is authorized for educator review use only by LYONEL LAULIÉ, Universidad de Chile until Aug 2021. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860 This document is authorized for educator review use only by LYONEL LAULIÉ, Universidad de Chile until Aug 2021. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860 13 No To what could this activity potentially be done by someone else? Did this activity contribute toward the company’s overall objectives? To what degree was this an activity you could have gotten out of? It was . . . Question tC A discretionary activity An unimportant/optional activity It contributed negatively It did not contribute (positively or negatively) It contributed in a small way It contributed in a moderate or large way Really important activity—has to be done by me Largely important activity—has to be done by me Reasonably important activity—could probably be done my someone junior to me Relatively unimportant activity—could be done by someone junior or even outsourced Very unimportant and straightforward activity—easily outsourced. • • • • • • • • • • • 5 6 30 39 19 28 34 36 1 7 36 27 29 2013 (%) <1 5 23 34 38 49 40 12 <1 6 17 44 34 t 2020 (%) rP os An important activity • op yo An essential activity • TABLE 1. Motivation for Performing Each Activity. Do 14 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW 63(4) rP os t To some extent, these differences can be explained by the immediate work context. During the 2020 lockdown, many organizations were in crisis mode, so the work managers were doing was genuinely more important and harder to delegate. But there also appears to be some self-justification here, in that greater freedom to choose what you do (i.e., when working from home) makes you more likely to believe it to be worthwhile. Our interviews provided some additional color, particularly the ones from more junior managers who were not getting as much scope to contribute as they would have liked. Several reported feeling “out of the loop” on important decisions. One commented, op yo It was just a vacuum. The communication [in the first few months of the Covid lockdown] was really bad. I had suggestions for things we should do but I was fobbed off with, yes, we are doing that. They could easily have given more frequent updates. Some of this behavior was exacerbated by the crisis conditions in MarchMay 2020, but there is evidently a risk that virtual working makes it hard to stay informed through corridor or lunchtime conversations. Overall, there was a tendency for managers to take a narrower and more controlling view of their role when working from home. Many managers we spoke to were aware of this and were taking steps to alleviate these risks, for example, with weekly all-employee meetings. tC How Do Managers Learn and Develop? No In the third study, we shifted our perspective from a static analysis of what activities managers do to the dynamic of learning and development—one of the core activities of management according to Peter Drucker.24 Managers continuously learn and develop in their roles as they try out new ideas, observe the consequences of their actions, and make sense of the behaviors of others.25 In addition to taking care of their own professional development, managers also nurture and support the development of their subordinates.26 Do To understand these issues, we used the same framework as above, though in a more dynamic way to capture the process of development. The cognitive dimension here is mostly about formal training-type activities to increase understanding, the task-based dimension involves taking on challenging work assignments and new opportunities, and the people-based one is about seeking feedback and coaching to enrich the manager’s sense of self or identity. Again, this three-way split is well established in the literature.27 We asked specific questions about each domain, and these are listed in Figure 3. The findings can be summarized in three points. First, on the cognitive dimension, respondents were doing many fewer face-toface training programs, but making up for the shortfall with more online training programs. Our interviews confirmed this point: “in terms of self-development and training, I had 2-3 programs which take 5-6 weeks each. I would never have been This document is authorized for educator review use only by LYONEL LAULIÉ, Universidad de Chile until Aug 2021. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860 op yo rP os FIGURE 3. Management development in office and virtual workplaces. 15 t The Blinkered Boss: How Has Managerial Behavior Changed with the Shift to Virtual Working? Note: How effective at each of the following: 1 Not at all effective; 2 Slightly effective; 3 moderately effective; 4 effective; 5 highly effective. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. able to do it [when working in the office], but online we just did it,” said one respondent. Online platforms such as Coursera and LinkedIn Learning reported massive increases in user numbers during 2020.28 No tC Second, respondents rated their task-based development opportunities as roughly the same in office-based and virtual working. To be specific, there were no differences in effectiveness for three questions (taking on challenging assignments, challenging the status quo, and working collaboratively with others). However, there was a significant reduction in exposure to new experiences in the virtual working environment. This rings true—there is a steep learning curve when one moves into a challenging new role, and it becomes even steeper when you cannot work face-toface with close colleagues and learn from them. As one respondent commented, “I used to throw people into new assignments, where they learned on the job, watching and learning from experienced colleagues. That’s almost impossible to do in a virtual setting.” In our interviews, we also observed big differences by level, with junior people often being reassigned during the early stages of virtual working (e.g., office managers taking on new roles), but senior managers being asked to stay in their existing roles for longer. “For many months, we were working really long hours. . . . it wasn’t the time to try something new,” said one respondent. Do Third, and most importantly, respondents reported being significantly less effective in all the people-based aspects of personal development when working in a virtual environment. To be specific, they reported less challenge and feedback from those around them, less support from coaches and mentors, and fewer opportunities to learn by observing others. Based on the interviews, it seems this lack of feedback and coaching was partly a lack of time (with task-based work taking priority) and partly that such activities are more fulfilling when done in person. One respondent commented, This document is authorized for educator review use only by LYONEL LAULIÉ, Universidad de Chile until Aug 2021. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860 16 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW 63(4) rP os t Look . . . it’s not that [coaching] doesn’t work over Zoom . . . but you have to be much more proactive to find time for it . . . it isn’t easy. I haven’t had a good discussion with [my coach] for months. Discussion op yo In sum, virtual working appeared to be stifling some key aspects of personal development for managers. One interview respondent said that “many aspects of career management are on pause” in his organization. Consistent with the findings from the first survey, it is not hard for managers to address the cognitive aspects of learning through the myriad of online courses and webinars that can be consumed sitting at a home office desk. But the aspects that require intense personal interaction and challenging new experiences are much harder to address. For example, consider the way an apprentice learns a new trade: he or she starts as a peripheral observer, gradually getting involved, taking on small tasks, and getting direct feedback from the master until he or she becomes a fullfledged expert. In a similar way, this form of situated learning is a vital part of how managers develop, and yet it is very hard to replicate in a purely virtual working environment.29 The Evolution of Managerial Work tC The findings from our three linked studies paint a clear picture of the challenges managers were grappling with as they learned to work virtually. During “lockdown,” managers were working in a more structured and controlling way, with a greater focus on analytical and task-based work, and less emphasis on enabling and motivating their subordinates. They had fewer opportunities for personal growth or for developing those around them, and their ability to create a supportive and enabling environment was reduced. Of course, not all managers were acting in this way, but as a generalized statement, this is accurate—and somewhat concerning. Do No The findings also point to a broader conceptual point about how managerial work is evolving. Going back to the discussion earlier on, there was a transition during the twentieth century from management as “monitoring and controlling” with an emphasis on task, through to management as “coaching and supporting” with an emphasis on people. This transition was enabled by technology, education, and social change, and it took place within the context of a factory or office, where the manager had a broad set of levers of influence at his or her disposal. With the move into a virtual working environment, the immediate levers of influence managers have to play with are fewer in number, for reasons that have been discussed already. However, there is still a range of options open to managers in terms of how they view the role (see Figure 4). One way forward is to emphasize the task dimension. This of course is how managers often handle outsourcing and freelance relationships—it is commonplace to work with This document is authorized for educator review use only by LYONEL LAULIÉ, Universidad de Chile until Aug 2021. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860 op yo rP os FIGURE 4. The evolution of management—Four models. 17 t The Blinkered Boss: How Has Managerial Behavior Changed with the Shift to Virtual Working? individual freelancers or contractor firms at a distance, often another country, and for the two parties never to meet face to face. In this situation, the role of management can be described as “contracting and reviewing” with an emphasis on delivering results and less emphasis on the people aspects of the relationship. No tC The other way forward is to attempt to maintain an emphasis on people management in the virtual environment (quadrant D in Figure 4). In part, this means transplanting existing practices from the face-to-face to the virtual world, as indeed many people and firms are doing. It also means developing new practices that are only made possible by virtual working, such as letting people choose their own hours and interweaving their work and home lives much more. Unlike quadrant C, which is narrow and contractual, quadrant D is potentially the opposite—it is about “inspiring and enabling” employees so they can do their best work within a given frame.30 Do The evidence presented here suggests that at the time of the research, managers were stuck somewhere between C and D, with good intentions to emphasize the people-management aspects of their role but often struggling to deliver on those intentions. To some degree, responsibility for getting this right lies with individual managers, who are expected to be creative in adapting to their new circumstances. But responsibility for the problem also lies with the bureaucratic systems in which they operate. The shift to a virtual way of working significantly increased the pressure on managers, who had to cope with additional task-based and people-based problems, often with very little support. So it is not surprising that many of them seemed somewhat “blinkered” in how they responded. Moving beyond the pandemic context, however, we can anticipate changes for the better, as short-term challenges are overcome and as some of the benefits of virtual working become clearer. There is potentially an opportunity for management innovation here, for individuals and organizations to This document is authorized for educator review use only by LYONEL LAULIÉ, Universidad de Chile until Aug 2021. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860 18 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW 63(4) Implications for Practice rP os t experiment with new ways of working to make management an “inspiring and enabling” activity.31 op yo There are some obvious limitations to this study that need to be borne in mind before offering prescriptive advice to managers and firms. First, the samples of managers involved in the three studies were fairly small, and their experiences may not be generalizable to people in other sectors and countries. Second, there was quite a wide variation in the level of responsibilities of these managers and in their functional responsibilities, so our aggregate findings potentially obscure some of the differences that might exist across levels and functions. Third, the data were collected in a particular time period (April to August 2020) when people were learning how to work in a virtual setting, and when many firms were facing crisis-like situations. These studies were, in other words, a useful first step in understanding the wholesale transition to virtual working, but this is a fluid situation so it will be important to continue to monitor how things change in the years ahead. Notwithstanding all these important caveats, we would like to put forward some practical advice to managers about how best to respond to the challenge and opportunity of virtual working. Table 2 provides an overview of the differences between office-based and virtual working in terms of the different aspects of managerial work. Below we provide a summary of our key recommendations. tC Harness the freedom afforded by virtual working. A clear benefit of virtual working for many people is greater degrees of freedom in how and when they work and, as research has shown, this greater autonomy is typically associated with higher levels of intrinsic motivation and improvements in productivity.32 Unfortunately, this higher level of autonomy can create discomfort among managers, who might be worried about the employees slacking off when working from home. Do No The view emerging from this research is that managers should embrace rather than resist the greater freedoms afforded by virtual working. This means providing clear and inspiring objectives, being more proactive in delegating to front-line employees, and shifting from input-based to output-based measures of performance. A recent example of this policy in action comes from German conglomerate Siemens, which allows its 385,000 employees around the world two to three days virtual working per week. According to Deputy CEO Roland Busch, this new working model “will also be associated with a different leadership style, one that focuses on outcomes rather than on time spent at the office.”33 While virtual working provides some people with greater freedom, it is worth noting that others ended up with less time and attention on their work during the Covid pandemic, because of home-schooling and caring responsibilities. While not our focus here, changes to work-life balance brought about by the shift to more virtual work is an important phenomenon for future research.34 This document is authorized for educator review use only by LYONEL LAULIÉ, Universidad de Chile until Aug 2021. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860 This document is authorized for educator review use only by LYONEL LAULIÉ, Universidad de Chile until Aug 2021. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860 19 No tC Easy access to colleagues and information when needed, but frequent interruptions make it harder to get things done. Easier to arrange short ad hoc meetings, you can meet many people in the course of a day; and private meetings on sensitive issues work very well in an office environment. Face-to-face meetings are very good for creative and problem-solving type activities, because they enable unscripted and serendipitous connections. But such meetings often take a long time, and some have bad team dynamics, e.g., ‘grandstanding’ behavior. There is great scope for social activities, informal gettogethers, celebrations and events, which many people appreciate. Such activities are useful in generating social connectivity and reinforcing the organization’s culture. Many aspects of learning and development, such as observing others, taking on challenging assignments, seeking feedback, are made easier and more effective in an office environment. Working on your own tasks One-on-one and small meetings Large team meetings and team dynamics Office-wide activities Professional development for yourself and others Virtual Working t Personal learning, for example, by watching videos or reading, are easier when working virtually because of the lack of disturbance. But the social aspects of learning-by-doing and gaining feedback work less well. Some people (e.g., introverts) enjoy not having to take part in office activities. But for managers the absence of a shared space is mostly negative, because they cannot get an informal sense of how people are feeling or what is happening. rP os Large meetings are more focused and structured, and the manager has greater control over the proceedings (for better or worse). But it is harder to get feedback or “read the room”, and building agreement on sensitive issues is harder. Meeting schedules are more structured, it is clear who is meeting when and why. But the process takes more time, and on sensitive issues virtual meetings are generally less effective. Easier to focus on your own tasks and agenda when you are not disturbed; more opportunity to reflect and think deeply. Working from home saves time and money, and some people like the convenience. But others find it hard to disconnect, and work-life balance can suffer. op yo Separation of work and home life is clearer and easier, and for most people it gives greater balance. But the time and cost of commuting is significant. Your working day Office-Based Working TABLE 2. Summary of the Relative Beneÿts of Ofÿce-Based and Virtual Working for Managers. Do 20 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW 63(4) rP os t Make use of all possible levers of influence. Working virtually makes it harder for managers to do their jobs well because many of the informal levers of influence they are accustomed to, such as monitoring what people are doing, sensing their mood and responding accordingly, or sharing a quick thought over a coffee machine, are not readily available. So as a first step, learning how to replicate or adapt these informal levers to the virtual environment is important.35 For example, you can create “virtual office hours” when people know their managers are available for a casual check-in. Desktop-based messaging services are also useful for resolving issues quickly. And it is useful to remind team members to pick up the phone for issues requiring back and forth communication, as people tend to be more hesitant to do this than they would be initiating a similar in-person chat.36 tC op yo But equally important here is amplifying those levers of influence that work better in the virtual setting. In our interviews, we heard mixed views about the effectiveness of virtual (rather than face-to-face) meetings. Some emphasized their benefits; for example, they tend to start on time, there are fewer side conversations, it is easier for introverts to contribute, and bad behavior (e.g., bullying) is less common. Others focused on their limitations: for example, the difficulty of “reading the room” to see how people are responding to what you say; and the greater control that the chair of the meeting has to decide who speaks when, particularly in discussions of tricky matters. Our advice is for managers to play up these benefits and make them real virtues, for example, by having super-short breakouts in groups of three to four before opening up an issue for plenary discussion. For things that do not work so well virtually, hybrid arrangements are the way forward. No Design your hybrid working arrangements carefully. In situations where businesses move from “lockdown” restrictions toward greater freedom of movement, it is tempting to allow employees discretion over when to work from home. But our research suggests some clear top-down guidance would be prudent in such circumstances to ensure that time in the office is spent on the most value-added activities. For example, one respondent commented on his brief return to officebased work in Summer 2020, “I used to think of the office as the place to get tasks done and home as the place for social stuff; now it’s the exact opposite.” His point was that “catching up” with colleagues informally is better done face to face, as are several other activities such as brainstorming, agenda-setting, resolving tricky problems, and negotiating. The structuring of work—in terms of who spends time in the office and when—should reflect these realities. There are potentially important shifts underway here that would merit additional research. Do In terms of how to design a hybrid model, we recommend using the categories in Table 2 to help define the specific activities where physical co-location is necessary. Then one can earmark specific days when the immediate management team, or the entire office, need to be present, perhaps two days per week.37 It is also useful to build some norms around how people will communicate their whereabouts and what their working patterns will be. In the early stages, regular reviews are helpful to troubleshoot and refine the process. This document is authorized for educator review use only by LYONEL LAULIÉ, Universidad de Chile until Aug 2021. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860 The Blinkered Boss: How Has Managerial Behavior Changed with the Shift to Virtual Working? 21 op yo rP os t Actively create development pathways for managers. Many managers left their employees in their existing roles through lockdown, as the costs of moving people around—especially in such an uncertain time—were considerable. But it is well established that people learn more when they are given challenging new assignments, not when they do the same thing many times. The book Lessons from Experience argued that 70% of learning occurs on the job through challenging work assignments. Related to this is the notion of situated learning mentioned earlier, which says people develop new skills by observing and experimenting under the watchful eye of an expert.38 Such learning-by-doing opportunities were in relatively short supply during the height of the Covid pandemic. To the extent that virtual working becomes the norm, managers have to become more proactive in findings opportunities for their employees (and themselves) to take on the types of novel assignments that help them develop and grow. Again, here are some specific recommendations based on what we have seen working. First, try to avoid putting the same “A team” players on important projects—it is important to give people new developmental experiences even if it means the initial stages of work on the project take a little longer. Second, create mentorship schemes for new hires and high-potentials, so they are paired with a senior colleague and encouraged to join them in virtual meetings. Third, take active charge of personal development by scheduling time with colleagues and subordinates for feedback sessions. If there is a budget for personal coaches to facilitate such meetings, that is likely to be even more effective.39 No tC In addition to these specific recommendations for managers, our findings hint at the opportunity for large firms to make more systemic changes in how they are structured. For managers to have the time and energy to work more effectively, they need support from above. Unfortunately, many large firms operate with a bureaucracy that “saps initiative, inhibits risk taking, and crushes creativity,”40 and it is not getting any less burdensome with the shift to virtual working. There is thus a bigger challenge for firms to address, namely, to put in place structural changes that provide greater clarity and freedom to act for managers in front-line roles. Such changes are underway in a wide variety of firms, often using so-called “agile” principles. There is scope for much greater progress here, to provide managers with clear accountability and purpose, and to help them, in turn, to shape the working environments for their own employees. Conclusions Do The shift from office-based to virtual working happened almost instantaneously in March 2020, and it allowed firms to develop expertise and patterns of behavior that seemed likely to endure beyond Covid. This article provided an evidence-based view of the changing nature of managerial work, highlighting that managers struggled with the transition, with many taking a narrower, more controlling view of their work, with a greater focus on analytical and task-based activities at the expense of people development and relationship management. We discussed some of the tactics managers need to adopt to facilitate a more This document is authorized for educator review use only by LYONEL LAULIÉ, Universidad de Chile until Aug 2021. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860 22 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW 63(4) rP os t people-centered approach when working virtually, and some of the more systematic changes that firms might consider putting in place. As a final thought, we note that the virtual working environment “exposes” managers to the more challenging aspects of their role, that is, inspiring and enabling those around them. Without access to the usual levers of influence, they have to become more proactive and disciplined in how they spend their time to get the best out of others, and they have to be more thoughtful about the structures they put in place to enable effective collaboration. In Warren Buffet’s famous words, when the tide goes out, we can see who is swimming naked. Appendix op yo Research Methodology We developed three survey instruments, and each one was administered at two different points in time. tC The first survey of Management Activities was administered to a random sample of 315 managers in 2018. The sampling frame, as above, was people in knowledge-work sectors (education, marketing, media, accounting, technology, science, finance, and public sector) with university-level education and at least three years of professional experience. In addition, all these individuals had line-management responsibilities. The survey asked respondents how effective they were in each of 32 different managerial tasks. Each pair of questions represented one of the 16 activities listed in Figure 2. The questions were based on earlier publications by one of the authors, and the research was written up as part of an article in Sloan Management Review.41 No In August 2020, the survey was sent to a random sample of approximately 500 managers drawn from a larger database of London Business School alumni to ensure that they met all the same criteria as above. We received 82 valid responses to this survey. Respondents were asked how effective they had been in each of the 32 managerial tasks since the beginning of lockdown (which for most of them was March 2020). Do We compared the 2018 and 2020 responses using independent sample t tests, one for each of the 16 management activities, and we found that 11 of them were significantly different at p < .05. Because the two samples were not identical, we also performed a series of regressions, controlling for the age, gender, seniority, and years’ experience of the respondents, and the significant differences remained. Figure 2 indicates the significance level for the t tests. Full details of the statistical analysis are available from the authors. The second survey of How Managers Spend Their Time was initially done in 2013 and then repeated in June 2020.42 Rather than ask people about their general reflections on how they filled their days, we asked them to open their Outlook Calendar and go to a day from the previous week that was typical of their working life. We then asked them to list between six and ten discrete This document is authorized for educator review use only by LYONEL LAULIÉ, Universidad de Chile until Aug 2021. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860 The Blinkered Boss: How Has Managerial Behavior Changed with the Shift to Virtual Working? 23 rP os t activities during that day, such as a meeting or a period of time responding to emails. The interviewer asked the respondent to describe briefly what the activity involved, how long it lasted, and who else was involved. Then there were questions about such things as why they did that activity and how valuable it was. op yo In the 2013 survey, we gathered data on 329 specific activities undertaken by 45 knowledge workers (33 line managers, 12 individual contributors). In the 2020 survey, we gathered data on 264 activities from 40 individuals (26 line managers, 14 individual contributors). In terms of the sampling frame, the individuals were selected randomly, subject to a few specific criteria: at least five years full-time work experience; at least a bachelor’s degree; and working in a knowledge-based role where effectiveness is determined by the use of brainpower and the capacity to make sound judgments. Because the survey participants were (mostly) different people, the analysis was done using independent sample t tests. The third survey of Management Learning and Development was first administered in late 2019 to a sample of almost 5,000 alumni of London Business School executive education programs. There were 497 valid responses to this survey. Respondents were asked how effective they were in undertaking various forms of learning and development, for example, taking part in formal training programs, gaining challenging feedback from peers and colleagues, and taking on new work assignments. This research has been written up but has not yet been published. No tC In August 2020, we went back to 231 of the 497 respondents, that is, the ones who had given permission for us to contact them again, and we asked them the same questions again, focusing on how effective they were in these various forms of learning and development during the period March-July 2020 (when they were working entirely or mostly from home). We received 38 valid responses, and because these individuals had offered their personal contact details, we were able to pair their answers with the ones they had given in late 2019. In our analysis, we therefore focused only on the 38 respondents who responded to both surveys, and we conducted paired t tests for each of the 12 survey items (these are listed in Figure 3). Again, the significance levels of the differences are included in the figure, and detailed results are available from the authors. Do Looking across all three surveys, we acknowledge some differences in the samples. They were consistent in their focus on “knowledge workers” in managerial positions with degree-level education. However, there were significant differences in the scope of responsibility of respondents: they were operating one to four levels from the top of their organizations and, with the exception of the “individual contributors” in survey one (26 people), they had responsibility for between 4 and 1,000 employees. These differences should be borne in mind when interpreting the findings. This document is authorized for educator review use only by LYONEL LAULIÉ, Universidad de Chile until Aug 2021. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860 24 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW 63(4) t Author Biographies rP os Julian Birkinshaw is a Professor of strategy and entrepreneurship at London Business School (email: jbirkinshaw@london.edu). Maya Gudka is an Executive Coach and Researcher affiliated with London Business School (email: vdamato@liuc.it). Vittorio D’Amato is Director of the international MBA program at LIUC Business School at Università Cattaneo in Castellanza, Italy (email: maya. gudka@gmail.com). Notes Do No tC op yo 1. For example, see https://blogs.microsoft.com/blog/2020/10/09/embracing-a-flexible-work place/; https://press.siemens.com/global/en/pressrelease/siemens-establish-mobile-workingcore-component-new-normal. 2. P. Choudhury, “Our Work-from-Anywhere Future,” Harvard Business Review, 98/6 (November/December 2020): 58-67; J. Birkinshaw, J. Cohen, and P. Stach, “Knowledge Workers Are More Productive from Home,” Harvard Business Review (August 31 2020): 2-11, https://hbr.org/2020/08/research-knowledge-workers-are-more-productive-from-home. 3. G. D’Auria, A. De Smet, C. Gagnon, J. Goran, D. Maor, and R. Steele, “Reimaging the Post-Pandemic Organization,” McKinsey & Company, May 15, 2020, https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/reimagining-the-post-pandemicorganization#; D. Sull, C. Sull, and J. Bersin, “Five Ways Leaders Can Support Remote Work,” Sloan Management Review, June 3, 2020, https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/ five-ways-leaders-can-support-remote-work/. 4. Our emphasis in this paper is on management (getting work done through others) rather than leadership (a process of social influence), though the two phenomena are clearly linked. For example, see H. Mintzberg, Managing (San Francisco, CA: Berret-Koehler, 2009). 5. H. Mintzberg, The Nature of Managerial Work (New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1973); L. B. Kurke and H. E. Aldrich, “Note—Mintzberg Was Right! A Replication and Extension of the Nature of Managerial Work,” Management Science, 29/8 (August 1983): 975-984; S. Tengblad, “Is There a ‘New Managerial Work’? A Comparison with Henry Mintzberg’s Classic Study 30 Years Later,” Journal of Management Studies, 43/7 (November 2006): 1437-1461; P. Osterman, The Truth about Middle Managers: Who They Are, How They Work, Why They Matter (Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press, 2009); J. Hassard, L. McCann, and J. Morris, Managing in the Modern Corporation: The Intensification of Managerial Work in the USA, UK and Japan (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009). 6. Two influential studies of the evolution of management are: S. R. Barley and G. Kunda, “Design and Devotion: Surges of Rational and Normative Ideologies of Control in Managerial Discourse,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 37/3 (September 1992): 363-399; Z. Bodrožić and P. S. Adler, “The Evolution of Management Models: A Neo-Schumpeterian Theory,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 63/1 (March 2018): 85-129. 7. Nicholas Carr, The Big Switch: Rewiring the World, from Edison to Google (New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 2009); D. A. Wren and A. G. Bedeian, The Evolution of Management Thought (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley, 2020); M. J. Mol and J. M. Birkinshaw, Giant Steps in Management: Creating Innovations that Change the Way We Work (Harlow, UK: Pearson Education, 2008). 8. T. D. Allen, T. D. Golden, and K. M. Shockley, “How Effective Is Telecommuting? Assessing the Status of Our Scientific Findings,” Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 16/2 (October 2015): 40-68; A. Felstead and G. Henseke, “Assessing the Growth of Remote Working and Its Consequences for Effort, Well-Being and Work-Life Balance,” New Technology, Work and Employment, 32/3 (November 2017): 195-212. 9. This data is from page 42 of Allen et al., op. cit. 10. N. Bloom, J. Liang, J. Roberts, and Z. J. Ying, “Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130/1 (February 2015): 165-218. This document is authorized for educator review use only by LYONEL LAULIÉ, Universidad de Chile until Aug 2021. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860 The Blinkered Boss: How Has Managerial Behavior Changed with the Shift to Virtual Working? 25 Do No tC op yo rP os t 11. R. S. Gajendran and D. A. Harrison, “The Good, the Bad, and the Unknown about Telecommuting: Meta-analysis of Psychological Mediators and Individual Consequences,” Journal of Applied Psychology, 92/6 (November 2007): 1524. 12. J. Aroles, N. Mitev, and F-X. de Vaujany, “Mapping Themes in the Study of New Work Practices,” New Technology, Work and Employment, 34/3 (November 2019): 285-299. 13. For example, see R. Purvanova, S. D. Charlier, C. J. Reeves, and L. M. Greco, “Who Emerges into Virtual Team Leadership Roles?” Journal of Business and Psychology (June 24, 2020): 1-21; R. Borpujari, S. Chan-Ahuja, and E. Sherman, “Time Fungibility: An Inductive Study of Workers’ Time-Use during COVID-19 Stay-at-Home Orders,” AOM 2020 Submission, Rapid Research Plenary on COVID-19 and Organizational Behavior, 2020, https://obcovid19files.s3.amazonaws.com/borpujari.pdf; T. He, M. Minervini, J. Narayanan, and P. Puranam, “Communication Transparency of Virtual Hierarchical Teams on Team Creative Processes,” https://obcovid19files.s3.amazonaws.com/he.pdf; C. Flinchbaugh, A. Mchiri, S. Dharba, J. Fatoki, S. Ghandi, S. Rudsari, J-Y. Seok, and Q. Zhou, “Empathic Leadership during Covid-19: Distinguishing the Role of Cognitive Empathy,” All in Proceedings of Academy of Management Conference 2020, https://obcovid19files. s3.amazonaws.com/flinchbaugh.pdf. 14. This list of activities is from Henri Fayol, General and Industrial Management (London, UK: Pitman, 1967). Slightly different lists can be found in Luther Gulick and Lyndall Urwick, Papers on the Science of Administration (New York, NY: Institute of Public Administration, 1937); Peter Drucker, Management, 4th ed. (New York, NY: Collins Business, 2008); Mintzberg (2009), op. cit. 15. Bodrožić and Adler, op cit. 16. Barley and Kunda, op cit., p. 383. 17. Mintzberg (1973), op. cit. 18. Many books have discussed this shift. For example, see S. Ghoshal and C. A. Bartlett, The Individualized Corporation (New York, NY: Harper Business, 1997); L. Hill, Becoming a Manager (Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press, 2003). 19. A useful perspective on how managers shape the attention of their employees is W. Ocasio, “Attention to Attention,” Organization Science, 22/5 (September/October 2011): 1286-1296. 20. T. Bridgman and S. Cummings, A Very Short, Fairly Interesting and Reasonably Cheap Book about Management Theory (Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2020). 21. Mintzberg (2009), op. cit.; Charles B. Handy, Gods of Management: The Changing Work of Organizations (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1996); J. Birkinshaw and J. Ridderstråle, Fast/Forward: Make Your Company Fit for the Future (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2017). 22. Several studies have looked specifically into the challenges of innovation in virtual settings. For example, see B. Laker, C. Patel, P. Budhwar, and A. Malik, “How Leading Companies Are Innovating Remotely,” MIT Sloan Management Review, December 14, 2020, https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/how-leading-companies-are-innovating-remotely/. 23. H. Mintzberg, “The Managers Job: Folklore and Fact,” Harvard Business Review, 53/4 (July/ August 1975): 49-61. 24. P. Drucker, Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices (New York, NY: Harper Business, 1973). 25. G. Petriglieri, “Learning for a Living,” MIT Sloan Management Review, 61/2 (Winter 2020): 44-51; M. W. McCall, M. M. Lombardo, and A. M. Morrison, Lessons of Experience: How Successful Executives Develop on the Job (New York, NY: Free Press, 1988). 26. Peter Drucker’s Management (op. cit.) highlights the key role of developing others as a key managerial task. 27. Several books and articles have used the “knowing, doing being” framework for management development. For example, see S. Snook, N. Nohria, and R. Khurana, The Handbook for Teaching Leadership: Knowing, Doing, and Being (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2012); D. Crandall and J. Collins, Leadership Lessons from West Point (San Francisco, CA: John Wiley, 2010). 28. G. Moran, “People Can’t Get Enough of These Online Classes Right Now,” Fast Company, June 10, 2020, https://www.fastcompany.com/90512719/people-cant-get-enough-of-theseonline-classes-right-now. 29. J. Lave and E. Wenger, Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1991). This document is authorized for educator review use only by LYONEL LAULIÉ, Universidad de Chile until Aug 2021. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860 26 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW 63(4) Do No tC op yo rP os t 30. There is a related research stream looking at the enablers of coordination in distributed settings. For example, see K. Srikanth and P. Puranam, “Integrating Distributed Work: Comparing Task Design, Communication, and Tacit Coordination Mechanisms,” Strategic Management Journal, 32/8 (August 2011): 849-875. 31. See G. Hamel and M. Zanini, Humanocracy (Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press, 2020) for examples and ideas about management innovations to overcome bureaucracy and “inspire and enable” managers. 32. R. M. Ryan and E. L. Deci, “Self-determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being,” American Psychologist, 55/1 (January 2000): 68-78. 33. Press Release, July 16, 2020, https://press.siemens.com/global/en/pressrelease/siemensestablish-mobile-working-core-component-new-normal. 34. A. Hjálmsdóttir and V. S. Bjarnadóttir, “‘I Have Turned into a Foreman Here at Home’: Families and Work-Life Balance in Times of COVID-19 in a Gender Equality Paradise,” Gender, Work & Organization, 28/1 (January 2021): 268-283. J. Birkinshaw, D. McCallum, and S. Ghazi-Tabatabai, “The Remote Working Marathon—Morale, Flexibility and the Gender Divide,” Forbes, February 18, 2021, https://www. forbes.com/sites/lbsbusinessstrategyreview/2021/02/18/the-remote-workingmarathonmorale-flexibility-and-the-gender-divide/?sh=40cbf7892288. 35. For example, see Choudhury, op. cit.; Sull et al., op. cit. Also see E. Bernstein, H. Blunden, A. Brodsky, W. Sohn, and B. Waber, “The Implications of Working Without an Office,” Harvard Business Review, July 15, 2020, https://hbr.org/2020/07/ the-implications-of-working-without-an-office. 36. C. Newport, Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World (New York, NY: Penguin, 2019). 37. For example, see Christoph Hilberath, Julie Kilmann, Deborah Lovich, Thalia Tzanetti, Allison Bailey, Stefanie Beck, Elizabeth Kaufman, Bharat Khandelwal, Felix Schuler, and Kristi Woolsey, “Hybrid Work Is the New Remote Work,” BCG Perspectives, September 22, 2020, https://www.bcg.com/en-us/publications/2020/managing-remotework-and-optimizing-hybrid-working-models; E. Jacobs, “How to Make the Hybrid Workforce Model Work,” Financial Times, October 12, 2020, https://www.ft.com/ content/85e7199e-ad35-4072-89d6-349e083f3d61. 38. McCall et al., op. cit.; Lave and Wenger, op. cit. 39. One recent example is D. Jeske and C. Linehan, “Mentoring and Skill Development in e-Internships,” Journal of Work-Applied Management, 12/2 (April 2020): 245-258. 40. G. Hamel and M. Zanini, “The End of Bureaucracy,” Harvard Business Review, 96/6 (November/December 2018): 50-59. 41. J. Birkinshaw, J. Manktelow, V. d’Amato, E. Tosca, and F. Macchi, “Older and Wiser? How Management Style Varies with Age,” MIT Sloan Management Review, 60/4 (Summer 2019): 75-83. 42. J. Birkinshaw and J. Cohen, “Make Time for Work that Matters,” Harvard Business Review, 91/9 (September 2013): 115-118. This document is authorized for educator review use only by LYONEL LAULIÉ, Universidad de Chile until Aug 2021. Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu or 617.783.7860