Asylum Adjudication Process & Refugee Rights in South Africa

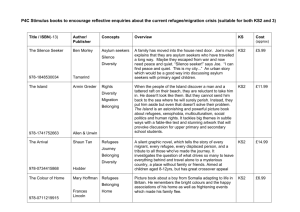

advertisement

The asylum adjudication process within the Department of Home Affairs and the plight of asylum seekers who have no right to work or study and cannot apply for permanent residency as well as the impact of the new Green Paper on these vulnerable people. Amy Nayman, 3350205 Mr W Le Roux Date: 17/05/2018 Introduction “No one leaves home unless home is the mouth of a shark.” This quote taken is from the book by Warsen Shire1 and captures the essence behind what it means to be an asylum seeker and later a refugee. Every year, hundreds of thousands of people are leaving their countries. Being different from normal immigrants who make this choice, these people are forced to leave their homeland. Their reasons may vary but they all have one thing in common: the fear of going back. These people are called refugees. Or at least that’s what they are called once they have been granted protection or at least recognition by their hosting state, through Home Affairs. However, while refugee status is still under consideration and the person is not yet recognised they are referred to as asylum seekers. The practice of granting asylum to people fleeing persecution in foreign lands is one of the earliest hallmarks of civilization. References to it have been found in texts written up to 3,500 years ago during the blossoming of the great early empires in the Middle East such as the Hittites, Babylonians, Assyrians and ancient Egyptians.2. According to the International Refugee Law, the definition of a refugee refers to people who flee outside his or her country of origin, unable or unwilling to avail him or herself of the protection of that country or to return there for fear of persecution because of his or her race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group or political opinion.3 In South Africa the definition remains the same and yet so many legitimate refugees fleeing from the ‘mouth of a shark’ find themselves in the mouths of this democratic nations office of Home Affairs, symbolically bleeding through the process of proving that the fears they risked their lives running from are real. These processes can take years to complete and leave the refugees involved traumatised. In recent times Home Affairs plans to make matters worse by entertaining the idea of border camps where sickness and extreme living conditions are meant to serve as a deterrence to anyone wanting to seek refuge in South Africa. This should not be possible in a country with such a humanitarian constitution. A country where human dignity is one of the founding principles. South Africa’s duty to asylum seekers and refugees In South Africa there is a process by which home affairs grants an asylum seeker protection and recognition. Either by way of the Refugee Act4 or by way of an obligation. The government of the Republic of South Africa has an obligation to grant protection to refugees and other persons in need of protection under a number of UN Conventions such as the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees.5 South Africa therefore took upon itself the legal obligation to receive and treat asylum seekers and refugees in agreement with the internal standards and principles 1 Shire, W “Teaching My Mother How to Give Birth”. “Refugees” www.unhcr.org 14 December 2016 3 Jastram, M. K. (2001). “The Legal Frame Work of International Refugee”. 4 No 130 of 1998 5 Jastram, M. K. (2001). “The Legal Frame Work of International Refugee”. 2 adopted in such instruments.6 Significantly, these international norms found their way into the creation of the Refugees Act 130 of 1998, which presented a highly progressive piece of legislation. The main grounds of refugee determination focused on granting the rights to persons faced with a well-founded fear of persecution or war in their home countries and the need to seek safety or sanctuary in a land other than their country of nationality or habitual residence. Eligibility Procedure: Asylum Seeker A person enters the Republic of South Africa through a port of entry (a land border post, airport or harbor), claims to be an asylum seeker and is, therefore, issued with a section 23 Permits which is a non - renewable “asylum transit permit” of the Immigration Act. The permit is valid for a period of 14 days only and authorizes the person to report to the nearest Refugee Reception Office in order to apply for asylum in terms of section 21 of the Refugee Act. The asylum seeker is required to furnish: A section 23 permit; any proof of identification from the country of origin; and travel document if in possession of one. The asylum seeker lodges in person his application at a designated Refugee Reception Office where an admissibility hearing takes place. The following are done: Applicant’s fingerprints taken in the prescribed manner; interpreter if secured (if necessary ); first interview conducted by a Refugee Reception Officer (RRO) and BI1590 form duly completed; applicant’s data and image captured in the refugee system; and an Asylum Seeker’s permit (a section 22 permit) is printed, signed, stamped and issued to the Asylum Seeker. The Refugee Act Despite all its broad-minded intent, at the commencement of said Act, which took effect in 2000, the authorities failed to grant unconditional rights to asylum seekers to work or study unless specifically authorised in certain cases and such rights were permitted in the asylum seeker permits. Moreover, if these circumstances were broken by conducting unauthorised work or study, that asylum seeker faced immediate detention, deportation and even criminal prosecution and a sentence of up to 5 years imprisonment. Whilst the Refugees Act failed to allow asylum seekers the right to work or study, on the face of it, it may have been pleasant considering the Refugee Regulations7 legislated an effective 3 month period to finalise and regularise their status from asylum seeker to refugee and this process would have been acceptable to most. 6 International treaties or conventions signed by South Africa. Regulations to the SA Refugees Act The Minister of Home Affairs has, in terms of section 38 of the Refugees Act, 1998 (Act No. 130 of 1998), made the Regulations in the Schedule. 7 For asylum seekers the right to work or study was more an exception than the rule and would be approved on application to the Standing Committee8 after the expiry of the intended 3-month adjudication period. As refugees they could work or study without exception. As is often the case the most vulnerable fall victim to administrations and genuine asylum seekers were no different as they were left without the right to work or study whilst their status was not being adjudicated in the stipulated 3 month adjudication period. The Department was consistently breaking Regulation 3(3)9 by refusing to consistently grant the right to work or study after the legislated 3 month period. Refugee status determinations would take anything from 6 to 12 months10, if not longer currently, to adjudicate, coupled with further time delays in the appeals process it potentially left asylum seekers without any means of income for the duration of this period. In many cases asylum seekers for obvious reasons would leave their countries with their families which left their situation even more desperate. Right to renew asylum seeker permits and appeals to Refugee Appeal Board There is a disturbing trend within the Department of Home Affairs to reject a significant number of asylum seekers applications as ‘unfounded’ in terms of section 24(3)(b)11. These cases will be heard before the Refugee Appeal Board on a date determined by them which can take up to 12 months or more. Appeal and Review Process In case of rejection, an asylum seeker or refugee who believes that he has a wellfounded fear of persecution but whose claim has been rejected, may decide to appeal against the rejection decision of the RSDO to the Refugee Appeal Board (RAB) in the prescribed manner within 30 days after the decision has been handed over to them. The Appeal Board conducts an appeal hearing during which the appellant who is entitled to a fair hearing have the rights to be heard and to present his case fully. The Refugee Appeal Board is responsible for considering and deciding appeals on decisions made by RSDOs. The RAB may after hearing an appeal confirm or set aside or substitute the decision of the RSDO. In respect of manifestly unfounded applications, the Standing Committee for Refugee Affairs (SCRA) reviews or confirms or sets aside decisions taken by the RSDO and refer cases back to RSDO for determination within 14 days as well as monitors in general the decisions of the RSDO. 8 “The Standing Committee for Refugee Affairs” immigrationsouthafrica.com Regulations to the SA Refugees Act 10 Watchenuka and Another versus Minister of Home Affairs and Others 11 of the Refugees Act 130 of 1998 9 The practical implications are that the final determination of a refugee application may take another 6 to 18 months to adjudicate and in this interim phase his or her section 22 asylum seeker permit is automatically renewed, normally for 6 month periods at a time. These extreme time delays in determining a status lead any asylum seeker, as a human being, to produce feelings of normalisation and a strong desire to realign or identify with a new habitat and stay in this country. When the need to leave his or her home country was so strong, an asylum seeker would desperately need to secure a livelihood just to survive and hence the right to work becomes paramount. Watchenuka Case In the case of Watchenuka and Another versus Minister of Home Affairs and Others12 the Court found technical administrative grounds to declare the prohibition of work or study contained in the Regulations made by the Minister of Home Affairs to be unconstitutional. The significance of this finding provided the asylum seeker with the right to work or study whilst awaiting his or her final determination of refugee status and it is widely lauded for its practical effects in affording an asylum seeker with an opportunity to become economically active especially relating to the regularisation of their status that may take a 12 months or more. Right to apply for Permanent Residency Asylum seekers were completely let out in the ‘cold’ when it came to the immigration stream, having no rights to apply for a residency status under the Immigration Act 13 of 2002 despite legitimately qualifying as any other foreign applicant from abroad. Moreover, any documentation under the Aliens Control Act (now the Immigration Act13) was specifically prohibited and had to handed in to the Department of Home Affairs for cancellation under section 22 of the Refugees Act. The only avenue open to an asylum seeker to enter the immigration stream was as a de facto refugee after successfully being granted asylum and obtaining the Standing Committee’s approval of such status under section 27(c)14 after 5 continuous years residence read with section 27(d) of the Immigration Act. However, had the asylum seeker not been granted asylum or the application for asylum was still pending – this route was not an option. In a landmark ruling in the matter of Dabone and others versus the Minister of Home Affairs and another15 the High Court issued a court order compelling the Minister of 12 (1486/02) ZAWC 64 (15 November 2002) 13 of 2002 (as amended in 2004) 14 of the Refugees Act 15 (case number 7526/03) 13 Home Affairs to allow asylum seeker permit holders and refugees to apply for temporary and/or permanent residence in terms of the Immigration Act. Contrary to the current provision in section 22 of the Refugees Act16 it was ordered by the court in the Dabone matter that asylum seeker permit holders and refugees are no longer required to give up their asylum seeking or refugee status in order to apply for a residency status in terms of the Immigration Act. In line with this rationale it was further held that possession of a passport is no longer a prerequisite for processing residency applications of asylum seekers or refugees. Prior to this development, one of the general requirements for the issuance of any residence permit was the submission of the applicant’s passport. Now the Department of Home Affairs has issued a directive to all its personnel to endorse the asylum seeker or refugee permits under section 22 and 24 respectively where any temporary or permanent residence status has been acquired under the Immigration Act. The practical effects of Dabone Now that the relevant orders have been spread and all stakeholders are properly informed of this significant development, it is perhaps important to consider the practical effects of this judgment on especially asylum seekers and how their current plight under the asylum and refugee stream may finally be overcome. It is necessary that key participants embark on a programme of inclusivity and undergo a shift away from all the negative connotations associated with asylum seekers and look to the positive impact that asylum seekers and refugees can make to South Africa and its economic prosperity – a stated intention under the Immigration Act. The failings of the entire asylum adjudication process within the Department of Home Affairs has had the resultant effect of necessitating a series of legal interventions that now provide very attractive options to asylum seekers and refugees to procure a residency status in South Africa under the Immigration Act. These asylum seekers and refugees need to ‘qualify’ in their own right and satisfy the requirements set out under the Immigration Act and Regulations17 as any other ‘foreigner’. When an asylum seeker becomes a foreign “spouse” in terms of the Immigration Act Many asylum seekers and refugees marry or become partners as the “spouse” of a South African citizen or permanent resident and in that case are afforded the right to apply to have their residency as a foreign spouse recognised under the Immigration Act. It cannot be argued that it is always a case of ‘convenience’ since the very stages of adjudication that take an inordinate amount of time provide many asylum seekers and refugees with the social environment to become party to serious 16 17 130 of 1998 Of the Refugee Act 130 of 1998 relationships as any other human being would experience going to any other country for such long periods of time. In the unreported judgment handed down on the 8th of February 2001 by the Cape High Court in the landmark case of Makinana v the Director-General of Home Affairs18 our immigration laws have now finally overturned the previous regime as it was held that it impacted on a foreign spouse’s constitutional right to be with his or her South African partner in South Africa. The effect of this judgment is that it resulted in the amendment to our immigration laws by allowing a foreign spouse to validly enter South Africa and whilst in South Africa to legally apply for a change in status and endorse such foreign spouse’s section 1119 visitor’s permit to successfully work, study or conduct an own business without any of the typical onerous standard requirements that apply to normal foreign applicants. In light of the judgment in Makinana, foreign spouses are now ‘armed’ with the right to apply for a change of status by procuring a visitor’s permit to reside with their South African partner or spouse, which may be further endorsed to accommodate the additional right to work, study or start an own business without the difficult requirements that non foreign spouses have to satisfy or prove. Asylum seeker applies for rights to work, study or start own business For asylum seekers or refugees who remain unattached, they will enjoy the rights under the Immigration Act as any other foreigner, whether to work, study or start an own business. It must be kept in mind that these requirements must be satisfied in full to successfully acquire such residency rights applied for as any other prospective immigrant foreigner. Many of the temporary residence grounds will through the passing of time evolve into legitimate permanent residency rights and potentially qualify as naturalised citizens of South Africa.20 Green Paper on International Migration The current immigration legislation in South Africa is under scrutiny. A new ‘Green Paper’21 was released to suggest ways for a more strategic and proactive immigration policy. The objective is to enable South Africa, via the right approach towards international immigration, to embrace global opportunities and maintain 18 Case No 339/2000 Immigration Act 13 of 2002 (as amended in 2004) 20 Jastram, M. K. (2001). “The Legal Frame Work of International Refugee”. 21 16 September 2016 19 national security. The current approach to immigration is a protective and re-active one, considering immigrants more as a potential threat than an asset.22 The 2016 “Green Paper” challenges this current view and looks at the vital role that immigration plays in the acquisition of skills which are essential to South Africa’s development in order to become a significant player in the global arena.23 The old perception that South Africa is swamped with immigrants is wrong and it is time to move away from this mind set. This was corroborated by an analysis of 2012 in the Quarterly Labour Force Survey24 which indicated that South Africans made up 90% of the workforce employed in every sector of the economy, including selfemployment. Should the main suggestions of the Green Paper materialise, we could see in the coming years a significant shift in the current immigration approach with a liberalisation of the immigration policies ruling not only South Africa but the rest of the continent. What points are getting raised in the Green Paper? It is quite evident in the Green Paper, that there might be a distinction between immigration from Africa compared to immigration from the rest of the world. The focus is on Africa: there is the vision of an “African Union 2063” which would basically mean a visa free continent; there is even talk of introducing an African passport in all African countries by 2018, which will de facto abolish the visa requirement for all African citizens. According to the Green Paper, is in its criteria for granting permanent residence or naturalisation to a foreigner. South Africa’s current granting of residence, or naturalisation, is automatically based on the ‘time criteria’ – period of time the applicant has legally spent in the country. Adopting a more strategic (and effective) criteria such as the skills which would benefit the country’s economic, social or cultural developments and which are therefore considered as “critical” would lead to fast-track permanent residence. In this respect, South Africa would be well inspired to take example from ‘points-based system’ countries like Australia and Canada, which have some of the most pro-active and strategic immigration policies in place. The sensitive issue of ‘asylum seekers’ and ‘refugees’ is concerned. Although South Africa is amongst the top 5 countries in the world for asylum seekers applications, 90% of applicants do not qualify for the ‘refugee status’. There is talk of establishing “Asylum Seekers Processing Centres” – basically, refugee camps – close to borders where applicants would be held before entering the country to determine if they qualify as refugees and fall under the Section 27 of the Refugees Act which allows them to apply for permanent residence after 5 years. This would mean having appropriate agreements in place with neighbouring countries to avoid the logistical, 22 Bhandari, S “Global Constitutionalism and the Path of International Law” 23 24 www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/P02112ndQuarter2012.pdf security and humanitarian problems which we have recently seen in other parts of the world. Conclusion Home Affairs has to take big steps to legitimise their waiting period and processing periods for asylum seekers. Furthermore, the issue of permanent residency in the case of asylum seekers should be given importance as these people have been waiting for years and have normalised into the South African population. Sending them back would be deeply traumatic after the years they have spent in the country. South Africa needs to adopt an integrated approach regarding its immigration policy, with various sectors of the Government and the population on board. This Green Paper aims to increase the hurdle for permanent residence if one is not highly skilled and also for naturalisation and to provide different approaches to refugees and asylum seekers with extra processing centres. Whether the country’s lack of common vision on the value of international migration will allow South Africa to see its immigration policy evolve towards a clear and coherent policy, only time will tell. Bibliography Cases Dabone and others versus the Minister of Home Affairs and another (case number 7526/03) Makinana versus the Director-General of Home Affairs Case No 339/2000 Watchenuka and Another versus Minister of Home Affairs and Others (1486/02) ZAWC 64 (15 November 2002) Legislation Immigration Act 13 of 2002 Refugees Act 130 of 1998 Regulation to the SA Refugee Act Vol. 418, No. 21075, 6 April 2000 Textbook Jastram, M. K. (2001). The Legal Frame Work of International Refugee. In M. K. Jastram, REFUGEE PROTECTION:A Guide to International Refugee Law (p. 8). Bhandari, S “Global Constitutionalism and the Path of International Law” Treaties 1951 UN Convention relating to the Status of Refugees 1969 OAU Convention Governing The Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa and 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees 1993 Basic Agreement between the Government of South Africa and the UNHCR Website “Refugees” www.unhcr.org 14 December 2016 <http://www.unhcr.org/ceu/84-enwho-we-helprefugees-html.html> "Political Repression, Ethnic Conflict and Refugees." 123HelpMe.com. 08 May 2018 <http://www.123HelpMe.com/view.asp?id=206847>. “Permanent Residence in South Affrica” < http://www.southafrica-newyork.net/homeaffairs/immigration.htm> “The Standing Committee for Refugee Affairs” immigrationsouthafrica.com < https://immigrationsouthafrica.com/the-standing-committee-for-refugeeaffairs/> www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/P02112ndQuarter2012.pdf