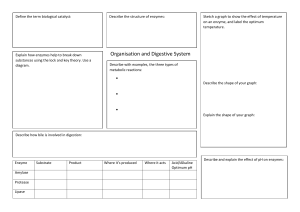

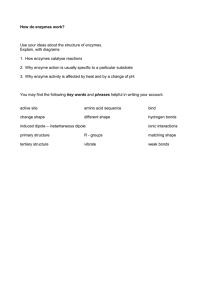

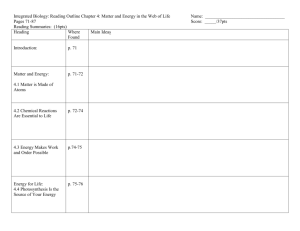

. Enzymes- Definition, Structure, Types, Mode of action, Functions • . Enzymes Definition An enzyme is a protein biomolecule that acts as a biocatalyst by regulating the rate of various metabolic reactions without itself being altered in the process. • • • • The name ‘enzyme’ literally means ‘in yeast’, and this was referred to denote one of the most important reactions involved in the production of ethyl alcohol and carbon dioxide through the agency of an enzyme zymase, present in yeast. Enzymes are biological catalysts that catalyze more than 5000 different biochemical reactions taking place in all living organisms. However, these are different from other catalysts which are chemical and can last indefinitely. Enzymes are proteins that are prone to damage and inactivation. Enzymes are also highly specific and usually act on a specific substrate of specific reactions. Created with BioRender.com 1. Intracellular enzymes • • The enzymes that act within the cells in which they are produced are called intracellular enzymes or endoenzymes. As these enzymes catalyze most of the metabolic reactions of the cell, they are also referred to as metabolic enzymes. • • • Most of the enzymes in plants and animals are intracellular enzymes or endoenzymes. Intracellular enzymes usually break down large polymers into smaller chains of monomers. All intracellular enzymes undergo intracellular digestion during cell death. 2. Extracellular enzymes • • • • • The enzymes which are liberated by living cells and catalyze useful reactions outside the cell but within its environment are known as extracellular enzymes or exoenzymes. Exoenzymes act chiefly as digestive enzymes, catalyzing the breakdown of complex macromolecules to simpler polymers or monomers, which can then be readily absorbed by the cell. These mostly act at the end of polymers to break down their monomers one at a time. Exoenzymes are enzymes found in bacteria, fungi, and some insectivores like Drosera and Nepenthes. Extracellular enzymes, unlike intracellular enzymes, undergo external digestion during cell death. Enzymes and activation energy • • • • • • • According to the transition state theory, for a chemical reaction to occur between two reactant molecules, their free energy level must be raised above a threshold level to take them to a high-energy transition state. The free energy needed to elevate a molecule from its stable, low-energy ground state to a higher energy unstable state is known as activation energy. The rate of a reaction depends on the number of reactant molecules that have enough energy to reach the transition state of the slowest step (rate-determining step) in the reaction. As a rule, very few molecules possess enough energy to reach the transition state. Enzymes, however, reduce the value of activation energy for a reaction, thereby phenomenally increasing the rate of reactions. Some enzymes lower the activation energy after the enzyme forms a complex with the substrate which by bending substrate molecules in a way facilitates bond-breaking. Other enzymes speed up the reaction by bringing the two reactants closer in the right orientation. Structure of Enzymes All enzymes are proteins composed of amino acid chains linked together by peptide bonds. This is the primary structure of enzymes. All enzymes have a highly specific binding site or active site to which their substrate binds to produce an enzyme-substrate complex. The threedimensional structures of many proteins have been observed by x-ray crystallography. These structures differ from one enzyme to another, and some of the enzymes and their structure has been described below: 1. Ribonuclease (RNase) • • • • • Ribonuclease is a small globular protein secreted by the pancreas into the small intestine, where it is involved in the catalysis of the hydrolysis of certain bonds in ribonucleic acids present in ingested food. This enzyme protein consists of a single polypeptide chain of 124 amino acid residues with lysine at the N-terminal and valine at the C-terminal. About 25% of the segments are in α-helix structure while the rest are β-sheets. Besides, there are eight cysteine residues, thus apparently forming four disulfide linkages that support the tertiary structure of the protein. The active site is present in the depression at the middle of the chain and the residues forming the active site are 6-8, 11, 12, 41, 42, 46-48, and 117-119. 2. Lysozyme • • • • • Lysozyme is another small globular protein that is present in tears, nasal mucus, gastric secretions, milk, and egg white. The enzyme lysozyme is consists of 129 amino acids linked together to form the primary structure, and the first amino acid is lysine. The enzyme has about 12% β-conformation and 40%-α helical segments. Lysozyme has a compactly-folded conformation with most of its hydrophobic R groups inside the globular structure, away from water, and its hydrophilic R groups outside, facing the aqueous medium. The active site has six subsites that bind various substrates or inhibitors, and the amino acid residues located at the active sites are 35, 52, 59, 62, 63, and 107. 3. Chymotrypsin • • • • Chymotrypsin is a mammalian digestive enzyme produced in the small intestine that catalyzes the hydrolysis of proteins. Chymotrypsin is highly selective in its action as it catalyzes the hydrolysis of only those peptide bonds that are present on the carboxyl side of amino acids with aromatic or bulky hydrophobic R groups. A molecule of chymotrypsin consists of 3 short polypeptide chains of 13, 131, and 97 amino acid residues respectively, supported by two interchain disulfide bonds. The secondary structure of chymotrypsin consists of several antiparallel β pleated sheet regions and a little α helical structure. How do enzymes work? • • • • • • The mechanism of action of enzymes in a chemical reaction can occur by several modes; substrate binding, catalysis, substrate presentation, and allosteric modulation. But the most common mode of action of enzymes is by the binding of the substrate. An enzyme molecule has a specific active site to which its substrate binds and produces an enzyme-substrate complex. The reaction proceeds at the binding site to produce the products which remain associated briefly with the enzyme. The product is then liberated, and the enzyme molecule is freed in an active state to initiate another round of catalysis. To describe the mechanism of action of enzymes to different models have been proposed; 1. Lock and key hypothesis Lock and key model of Enzymes. • • • • • • • The lock and key model was proposed by Emil Fischer in 1898 and is also known as the template model. According to this model, the binding of the substrate and the enzyme takes place at the active site in a manner similar to the one where a key fits a lock and results in the formation of an enzyme-substrate complex. In fact, the enzyme-substrate binding depends on a reciprocal fit between the molecular structure of the enzyme and the substrate. The enzyme-substrate complex formed is highly unstable and almost immediately decomposes to produce the end products of the reaction and to regenerate the free enzyme. This process results in the release of energy which, in turn, raises the energy level of the substrate molecule, thus inducing the activated or transition state. In this activated state, some bonds of the substrate molecule are made susceptible to cleavage. This model, however, has few drawbacks as it cannot explain the stability of the transitional state of the enzyme and also the concept of the rigidity of the active site. 2. Induced fit hypothesis Figure: Induced fit model of Enzymes • • • • • • • • • The induced fit hypothesis is a modified form of the lock and key hypothesis proposed by Koshland in 1958. According to this hypothesis, the enzyme molecule does not retain its original shape and structure. Instead, the contact of the substrate induces some configurational or geometrical changes in the active site of the enzyme molecule. As a result, the enzyme molecule is made to fit the configuration and active centers of the substrate completely. Meanwhile, other amino acid residues remain buried in the interior of the molecule. However, the sequence of events resulting in the conformational change might be different. Some enzymes might first undergo a conformational change, then bind the substrate. In an alternative pathway, the substrate may first be bound, and then a conformational change may occur in the active site. Thirdly, both the processes may co-occur with further isomerization to the final confirmation. Properties of enzymes • • • • • • • Enzyme molecules are large, and because of their large size, the enzyme molecules possess meager rates of diffusion. As a result, enzymes form colloidal systems in water. Enzymes act catalytically and accelerate the rate of chemical reactions occurring in biological systems and involving biological substrate. Most enzymes also do not participate in the reactions they catalyze. Similarly, some enzymes that are involved in the reaction are recovered without undergoing any qualitative or quantitative change at the end of the reaction. Most enzymes are highly specific in their action. Being proteinaceous in nature, the enzymes are susceptible to heat. The rate of an enzyme action increases with the rise in temperature; the rate being frequently increased 2 to 3 times for a rise in temperature of 10ºC. The enzymes catalyze the reversion of the reactions they catalyze. Enzymes are also pH sensitive as the pH of a medium will affect the efficiency of an enzyme and their activity is maximum at a specific pH. Active site of enzymes Enzymes are much larger than the substrate they act on, and thus there are some specific regions or sites on the enzyme for binding with the substrate, called active sites. Even in enzymes that differ widely in their properties, the active site present in their molecule possesses some common features; 1. The active site of an enzyme is a relatively small portion within an enzyme molecule. 2. The active site is a 3-dimensional entity made up of groups that come from different parts of the linear amino acid sequence. 3. The arrangement and orientation of atoms in the active site are well defined and highly specific, which is the cause of the marked specificity of the enzymes. However, in some cases, the active site changes its configuration in order to bind a substance. 4. The interactions or forces between the active site and the substrate molecule are relatively weak. 5. The active sites in the enzyme molecules are mostly present in grooves or crevices from where large quantities of water are excluded. Enzyme-substrate complex • • • The enzyme-substrate complex is a transitional molecule formed after the substrate binds with the enzyme. The formation of the enzyme-substrate complex is important for several reasons. The most important and notable reason is that the substrate binds with the enzyme temporarily and the enzyme is set free once the reaction is complete. This allows a single enzyme molecule to be used millions of times, and thus, only a small amount of enzyme is required in each cell. • Another advantage of an enzyme-substrate complex is the reduction in the free energy (activation energy) required for the substrate to rise into the high-energy transition state. Enzyme specificity Most enzymes are highly specific towards the substrate they act on. Enzyme specificity exists in a way that they may act on one specific type of substrate molecule or on a group of structurally related compounds or on only one of the two optical isomers of a compound or only one of the two geometrical isomers. Based on this, four patterns of enzyme specificity have been recognized; 1. Absolute specificity • Some enzymes are capable of acting on only one substrate, and an example of this is the enzyme urease that acts only on urea to produce ammonia and carbon dioxide. 2. Group specificity • • Other enzymes catalyze all reactions of a structurally related group of compounds. It is observed in lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) that catalyzes the interconversion of pyruvic acid and lactic acid along with a number of other structurally related compounds. 3. Optical specificity • • • Another important form of specificity is seen in some enzymes where a certain enzyme will react with only one of the two optical isomers of a compound. The oxidation of the D-amino acids to the corresponding keto acids by amino acid oxidase is an example of optical specificity. Among the enzymes that exhibit optical specificity, some might interconvert the two optical isomers of a compound. An example of this is alanine racemase that catalyzes the interconversion between L- and D-alanine. 4. Geometrical specificity • • Geometrical specificity is observed in some enzymes exhibit specificity towards the cis and trans forms. An example of this is the enzyme fumarase that catalyzes the interconversion of fumaric and malic acids Functions/ Biological roles of Enzymes Enzymes are vital for all biological processes, aiding in digestion, and metabolism. Besides, these are also involved in several other processes; 1. Enzymes like kinases and phosphatases are important for cell regulation and signal transmission. 2. Different enzymes are produced throughout the body for the regulation of reactions involved in various metabolic pathways. 3. The activation and inhibition of enzymes resulting in a negative feedback mechanism adjust the rate of synthesis of intermediate metabolites according to the demands of the cells. 4. They also catalyze Post-translational modifications involving phosphorylation, glycosylation, and cleavage of the polypeptide chain. 5. Some enzymes are also involved in the regulation of enzyme levels by changing the rate of enzyme degradation. 6. Since a tight regulation of enzymes is essential for homeostasis, any changes in the enzyme structure and production might result in diseases. 7. Enzymes synthesized in various organisms are also utilized in various industries for wine production, cheese production, bread whitening, and designing fabrics. Enzyme-catalyzed reactions Some examples of enzyme-catalyzed reactions include; 1. Inversion of cane sugar • Invertase converts cane sugar into glucose and fructose. invertase → C12H22O11 + H2O (sucrose/ cane sugar) C6H12O6 + C6H12O6 (glucose) (fructose) 2. Degradation of urea • Urease catalyzes the degradation of urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide. urease (NH2)2CO + H2O → (urea) 2NH3 + CO2 (ammonia) (carbon dioxide) 3. Isomerization reaction • Isomerase enzyme catalyzes the conversion of glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate into dihydroxy-acetone phosphate. 4. Protein digestion • Pepsin converts proteins into shorter polypeptides. pepsin Proteins → polypeptides Email Address* Cofactors and Coenzymes What are Cofactors? • • • • • Cofactors are non-protein molecules that are necessary for some enzymes to show their full activity. Cofactors can either be inorganic compounds like metal ions or organic compounds like flavin and heme. Some cofactors like zinc atom in carbon anhydrase are found tightly bound to the active site of the enzyme and help in catalysis. The enzymes that require cofactors are called apoenzymes when they do not have a cofactor bound to them. However, once the cofactors are bound, the enzyme is termed as holoenzymes. What are Coenzymes? • • • • • • . Coenzymes are smaller organic molecules that are loosely bound to some enzymes. The primary function of coenzymes is to transport chemical groups from one enzyme to another. Common coenzymes include NADH, NADPH, and ATP and some are compounds derived from vitamins. Coenzymes usually become charge as a result of enzyme action, which is why these are also considered secondary substrates. In some enzymes, coenzymes are released from the enzyme during the chemical reaction. The level of coenzymes is continuously regenerated and maintained at a steady level in the body.