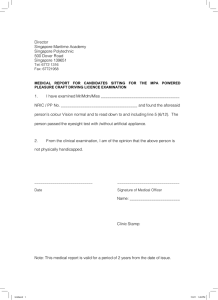

Inter-Asia Cultural Studies ISSN: 1464-9373 (Print) 1469-8447 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/riac20 Emergence of a cosmopolitan space for culture and consumption: the new world amusement park‐Singapore (1923–70) in the inter‐war years Wong Yunn Chii & Tan Kar Lin To cite this article: Wong Yunn Chii & Tan Kar Lin (2004) Emergence of a cosmopolitan space for culture and consumption: the new world amusement park‐Singapore (1923–70) in the inter‐war years , Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 5:2, 279-304, DOI: 10.1080/1464937042000236757 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/1464937042000236757 Published online: 04 Aug 2006. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 2491 View related articles Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=riac20 Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, Volume 5, Number 2, 2004 Emergence of a cosmopolitan space for culture and consumption: the New World Amusement Park-Singapore (1923–70) in the inter-war years1 WONG Yunn Chii & TAN Kar Lin The New World Amusement Park-Singapore is a significant aspect of the country’s urban and cultural history. Its value as an active component in, and as a significant facilitator of, Singapore’s emergent urban mass culture, in the context of British colonial rule, is largely uncharted. This paper offers, through examining archival records, building plans and oral history transcripts, an account of its genesis and its cultural dimension. New World was a product of deliberate design, in its multifaceted and complex existence as a site for architectural and planning experimentation, a quasi-public space, an endless programme of entertainment forms, and a shrewdly run business. Most importantly, the New World is an exemplary crucible of colonial modernity in Singapore of the inter-war years. Through its varieties of leisure industry and its spatial formation, it was the nexus of modern consumption and ‘mass culture’. As a site for the production and cultivation of new cultural forms and social types, New World exhibited the roles of architecture, urban space and event-planning in fostering and enabling the most tangible expression of a cosmopolitan mass culture in the colonial setting. ABSTRACT KEYWORDS: colonial modernity, urban amusement parks, colonial mass leisure industry, urban development. Introduction [A] cosmopolitan metropolis in cultural terms is difficult to define, for it has to do with both substance and appearance — with a whole fabric of life and style … While obviously determined by economic forces, urban culture is itself the result of a process of both production and consumption … [T]he process involved the growth of both socioeconomic institutions and new forms of cultural activity and expression made possible by the appearance of new public structures and spaces for urban cultural production and consumption … [A] cultural map of [the city] must be drawn on the basis of these structures and spaces together with their implications for the everyday life of [the city’s] residents, both foreign and [local] … (Lee 1999: 7) Lee Ou-fan made the above proposition with respect to his study of the urban culture of pre-revolution Shanghai. In what ways could one argue that the urban amusement park is one of such urban and functional typology of ‘substance and appearance’ that could contribute to the making of a cosmopolitan metropolis? In particular, and in the case of colonial Singapore, how did the former New World Amusement Park in Jalan Besar, contributed its cultural modernity? Progenitors Historically, the concentration of wealth and population in cities created the preconditions and ISSN 1464-9373 Print/ISSN 1469-8447 Online/04/020279–26 © 2004 Taylor & Francis Ltd DOI: 10.1080/1464937042000236757 280 Wong Yunn Chii and Tan Kar Lin demands for large scale amusement precincts. In China, during the Sung Dynasty, for example, huge public entertainment precincts called the wa-tze tapped the reserves of urban populations. In a similar way, the amusement parks in Singapore arose from the opportunities offered by a burgeoning urban population. Furthermore, in colonial Singapore from the1920s to 1930s, this influence was stirred by urban entertainment and popular consumer cultures that had emerged in Europe and America around the turn of the century. As a major Asian entreport of the British Empire with international transport infrastructure and communication,2 Singapore in the inter-war years was increasingly exposed to a wide variety of commodified spectacles, such as the world’s fairs and trade exhibitions, which were closely associated with the development of urban amusement parks. The very first known urban amusement park in Singapore, according to one source, was the Happy Valley Park located in the central Tanjong Pagar area, founded in 1921 (Gwee 1981: 22–23). Not much has been written about the Happy Valley, and it ceased operation after less than ten years in business. Following in the wake of Happy Valley’s establishment, the Malaya Borneo Exhibition was held in April 1922, to honour the visit of the Prince of Wales. The Exhibition, where ‘all very unusual things were shown’ and which attracted great crowds, was such a memorable event that the local business community was still reminiscing about it in the Depression years, proposing its revival to stimulate the ailing economy (British Malaya 1930: 39). Perhaps much more than the Happy Valley Park, the huge success of this one-off event spurred the project of the New World in 1923. In terms of external influences, Shanghai’s Great World and New World, are often cited as the main influence on Singapore’s own, not just for their names, but also through their nearness, cultural connections and cosmopolitanism. The New World and Great World of Shanghai, established in 1912 and 1917 respectively, were billed as entertainment multi-storied entertainment ‘palaces’. Founded by physician turned business entrepreneur Huang Chujiu3 (Fu 1999) the Shanghai ‘Worlds’ were developments backed by heavy investments, and they provided ‘every variety of entertainment Chinese ingenuity had contrived’ (von Sternberg 1998). The key was to provide popular public entertainment at the lowest possible price, with the largest variety of shows, to attract the largest number and range of patrons. Uniqueness of Singapore’s New World Shanghai’s Great World began as a temporary fairground. Despite its humble beginnings, the variety, intrigue, peculiarity, uniqueness and constant change in programmes offered by this set-up soon attracted enough business for its meteoric transformation into a multi-storey entertainment structure, unrivalled in scale and glamour (Fu 1999: 10–18). In comparison with Shanghai, Singapore’s New World experienced a slow and incremental expansion. The difference in development pattern reveals the particular contextual conditions that New World faced in Singapore. Unlike the Shanghai Great World, which was situated in one of the busiest districts in the city centre, Singapore’s New World was sited in the outskirts at Jalan Besar, an area away from the developmental pressures of the Central Area. Thus, over the five decades of its operation, there was no real need for intensified development into a multi-storied urban form to stay competitive. The slow growth could also be accounted for by the aggressive competitions from the other ‘Worlds’ and entertainment forms, all vying for the much more limited leisure market in Singapore, as compared with Shanghai. Furthermore, it also belies the civic anxieties of the colonial authorities towards the social impact of this urban entertainment development. Another factor that contributed to the uniqueness of Singapore’s New World as an urban and architectural typology was the weather. Prior to its official opening in 1917, the Shanghai Great World was an ad hoc set-up, bounded by tall bamboo fences, with free-standing makeshift stages and theatres scattered across the compound (Fu 1999: 13). However, the open The New World Amusement Park 281 configuration obviously could not weather Shanghai’s harsh winter, and its subsequent development into a multiplex was not only a business move, but also arose from a necessity to provide adequate shelter. In Singapore, on the other hand, tropical weather made under-thesky night-out activities not only tolerable but pleasant, and did not, until the arrival of ‘kinema’ entertainment, need sophisticated environmental tempering technologies. In fact, throughout its existence, New World maintained the open fairground-type configuration. Finally, and most significantly, the audience of the New World was drawn from the multi-racial migrant society of colonial Singapore, which was markedly different from Shanghai. Thus, despite receiving the initial impulses from Shanghai and from the west, Singapore’s New World finally was a product of gradual assimilation that could be argued as culturally unique and historically significant. Speculating the New World: risks and mutual interests The early 1920s was the beginning of a boom period that, over a few years, saw vast economic growth in Singapore, spurring the rise of many local entrepreneurs: Lee Kong Chian, Tan Lark Sye and Aw Boon Haw (Turnbull 1989: 127–128). The New World, opened in 1923, was similarly a product of speculative investment and enterprise. The New World was first conceived and founded by two Straits Chinese brothers Ong Boon Tat and Ong Peng Hock, despite a general misconception that it was the initiative of the Shaw Brothers, moguls of Asia’s film industry. Young enterprising businessmen in their 30s, the Ong brothers were working in their father’s company, Ong Sam Leong & Co., when they decided to try their hands in the entertainment business, as part of a land speculation exercise. At the time, the company was headed by Boon Tat as Administrator to the Estate, while Peng Hock worked as the Attorney. The primary business of Ong Sam Leong & Co., listed in the 1922 Singapore and Malaya Directory, was ‘Merchants, Estate & Property Owners’.4 It was only as late as 1938 that the Ongs entered into a joint venture with the Shaws.5 By this time, the amusement park was already well established, and the mature configuration of programmes and structures were in place. Finally, in 1958, the Ongs completely relinquished their ownership of the amusement park to the Shaw Organisation.6 Managed then by The New World (1958) Pte. Ltd, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Shaw, the park had already reached the crest of its full effects on the burgeoning mass culture in Singapore. Shaw Brothers subsequently owned and operated many amusement parks which mushroomed all over Malaya’s major cities, mostly modelled after the New World.7 Today, the New World Amusement Park is but an erased and ghostly vacant site awaiting re-development.8 Its almost iconic curved secondary entrance at Serangoon Road, of Deco and neo-classical elements (Figure 1), a favourite subject of tourist postcards, was demolished recently. It is now a forgotten landscape. Proprietor’s interests Real estate development was an especially risky proposition in the post-First World War recession years when the New World, tentatively billed as a ‘temporary exhibition’, opened in 1923. Under such a climate, what were the considerations behind the Ong’s ‘real estate’ speculation? The site was located in the middle of a low-lying area that stretched for two miles north of Syed Alwi Road (Figure 2). Because of the abundance of water, the site had, for decades, attracted agricultural activities, cattle-raising as well as other vocations favoured by Indian migrants who settled down in the area, such as the dhobis.9 The New World site was one of the company’s many land holdings in these bucolic fields. The present day Kitchener Road was a reserve road as yet unnamed. Jalan Besar, partially constructed around 1836 and completed by the Municipality in the 1880s, was a road 282 Wong Yunn Chii and Tan Kar Lin Figure 1. Serangoon entrance to the New World, undated. (Source: VICO-NUS, Lim Kheng Chye Collection, Image#LKC0108) connecting the densely built-up city area to the north-eastern suburb. Urban build-up along Jalan Besar and Serangoon Road near Rochor Canal had begun by the turn of the century, in the form of two-storey shop-houses.10 This was part of the ad hoc urban expansion starting in the late 19th century, resulting from overcrowding in the city. The turn of the century saw a rapid increase in the number of migrants, and they crowded into the city as they could not afford suburban housing and the cost of commuting. Meanwhile, the middle to upper income households fled to the suburbs in all directions around the city, in search of a better living environment. Old plantations were subdivided and replaced by new bungalows, terrace houses and shop-houses. Since the late 19th century, the waves of suburbanization had steadily expanded to areas such as Tanglin, Thomson, Tanjong Pagar and Telok Blangah. Being swampy and low-lying, the area was not a choice site however, attracting only the new middle class who could not afford a better location. As a result, houses built here in this period were generally modestly scaled bungalows, constructed of lower cost material, such as attap and timber, and elevated on piers as a measure to counter the periodic floods and rising damp (Edwards 1990: 70–72). North of Syed Alwi Road, the immediate vicinity of the New World site was especially affected by flooding of the upper reaches of Rochor River. This discouraged business and residential developments, and the land was occupied by Chinese vegetable farmers. (Siddique and Shotam-Gore 1983: 74) The development of the New World was likely one of the earliest attempts to drain comprehensively a large tract of the swampy area. By putting in place an effective drainage system and a value-adding leisure attraction, the arrival of New World in 1923 facilitated, if not accelerated, the urban development and consolidation of the area. The drainage system consisted of a concrete storm drain constructed along the ‘upstream’ north boundary (still existing at the time of this paper), complemented by a system of smaller drains dug around structures within the grounds. The New World Amusement Park 283 Figure 2. 1924 map of Singapore, Central Area and vicinity. Note fringe location of New World site in relation to the dense downtown area. (Source: Singapore History Museum) In addition, there were two added features around the Jalan Besar site. The adjacent Serangoon Road was served by electric tramways, the most modern form of public transport in the early post-First World War years. The long established recreational institution, the Racecourse at Farrer Park, was another important suburban amenity and magnet (Edwards 1990: 72; Liu 1999: 59, 104). The Ongs’ estate in Jalan Besar was probably bought over by them, if not owned originally, under speculations of further urban development and a rise in property prices. The earliest known site plan of 1923 shows that the Ongs had originally intended the site for shop-house development (Figure 3: BP 1a). They were also obliged by the Development Control Division of the Municipality to subdivide the land into blocks, and conform to the recently passed by-laws regulating back-lanes. However, in June 1923, Ong Boon Tat applied to the Municipal Council for approval to set up a ‘Temporary Exhibition & Recreation Ground — “The New World⬙’. Eventually, only two lots fronting the main road were developed into shophouses, retaining only a narrow ‘throat’ access to the rest of the estate. One could only speculate about the business intention behind this change of mind. This unusual configuration of land parcel, which remains to this day, could have been the result of a business strategy in frugal times. The Ongs probably sold the two prime lots fronting Jalan Besar, in order to finance the early New World temporary fairground, retaining only a narrow strip as the main entrance, just wide enough as a conduit tapping onto the traffic along the busy thoroughfare. In the post-war, post-recession years, such deployment of land for a temporary use was a prudent, albeit conservative move: it avoided the risks of reckless development and averted potential risks of financial ruins by deferring permanent development works until better times. On the other hand, the New World project could be also viewed from an entrepreneurial angle, namely as an attempt by the Ongs to diversify their assets by venturing into a nascent leisure 284 Wong Yunn Chii and Tan Kar Lin Figure 3 BP 1a. 1923 Site Plan showing the first New World layout. Note outline of intended shop-house lots, and concrete drain along the length of the site. Architect: EC Seah of SY Wong & Co. (Source: National Archives of Singapore. Graphic overlay by author) Figure 3 BP 1b. Part of 1923 site plan enlarged to show distribution of concessions (Source: National Archives of Singapore. Graphic overlay by author) The New World Amusement Park 285 Figure 3 BP 2. 1933 Plans of the New World, comprehensively redeveloped. Note distribution of concessions (in shade). Architect: Chan Fook Wah. (Source: National Archives of Singapore. Graphic overlay by author) and entertainment industry. The appropriateness of the site for starting a business in leisure such as the New World is readily discernible, given its location and ready population catchment. The majority of Jalan Besar’s community was made up of a largely middle class, cosmopolitan mixture of Chinese, Indians, Malays and Eurasians, typically small business operators or white-collar clerical class employees (Edwards 1999: 71).11 In addition, the nearby Racecourse at Farrer Park, attracted the predominantly Chinese and European patrons across various social strata, as well as working class migrants with its wide range of employment opportunities. The bettors, other than gambling on equestrian sports, would conceivably also have spare cash to spend on leisure and recreation after working hours. 286 Wong Yunn Chii and Tan Kar Lin Colonial interests The Municipal Council referred the 1923 plan by E. C. Seah of S.Y. Wong & Co.12 to the Development Control Improvement Trust (the precursor of Singapore Improvement Trust, henceforth referred to as DCIT), a planning entity created in 1920, ensuing from the Housing Difficulties Report the year before, to take over the role of the municipal authorities in supervising the improvement and future expansion of Singapore Town (Yeoh 1996: 161). DCIT favoured the proposal, citing that the land, recently converted from vegetable farms was still ‘too low and unconsolidated’ for the development of permanent building, and thus, ‘a suitable temporary use of it (seemed) justified’.13 It was probably in the interest of the colonial government to stimulate expansion of the city, as it would increase its taxable area. Further, this would also ease the acute congestion in the inner city core caused by the post-recession upsurge of immigrants. In addition, the north-eastern suburbs were, until then, plagued with flooding problems and suffered from ‘wasteful and impractical lay-out’.14 The low-density land-use of vegetable farms, kampongs and bungalows were probably considered to be far from optimizing the resources of the colony. The DCIT noted in its Report for 1921 that only zoning, a highly rationalized organization and management of urban space, could ‘prevent further disordered growth, remedy past mistakes and prevent congestions, and cause … business-like, ordered, common sense expansion and amenity’ (Yeoh 1996: 163). In line with this prognosis, the DCIT was quick to assert, in a memo, to the proprietors that for the New World site, ultimately ‘the best permanent use (was) for shop houses along main roads round this big block, and terrace dwellings inside’, justifying that they had been employing this strategy of zoning for two-and-a-half years, ‘and all (the affected) owners (seemed) quite satisfied.‘15 To emphasize further its determination in eventually affecting the zoning plans for the site, explicit conditions on length of tenure and cause for its cancellation were explicitly stated as such: • The Exhibition shall close each night at (time, not legible) … No hooters, or other noises such as would cause annoyance or nuisance to neighbouring house-holders shall be permitted. • Should the MC’s (Municipal Commissioners) decide at any time that a nuisance is caused by the Exhibition, etc. or that it is objectionable or contrary to the public welfare or interests, they may cancel the permit after giving the lessee three month’s notice to do so and there shall be no compensation due from the MC’s for such action by them. The needs to ensure public safety and health aside, these conditions also highlighted DCIT’s uncertainty over, and inexperience with, the nature of such a project, especially how a leisure and entertainment set-up would affect the surrounding environs. More important were the anxieties over looming social problems such an urban typology would create: the activities would not only cause ‘nuisance’ to the residents nearby, but also harm the larger ‘public welfare’. Despite this unsettling mixture of anxieties and civic-mindfulness, DCIT nonetheless approved the New World proposal. One could cite the mutual benefits for both parties concerned. For the colonial government, at least, it was an urban development that met their interests without incurring cost on their part, as the project was completely financed by private investors. The New World development, thus, although temporary, was an opportunity with little outlay to the colonial government, to transform an otherwise flood-prone area into prime land for development. The terms for the use of the site were negotiated and subsequently, accepted.16 Within one-and-a-half months, on 1 August 1923, a small and nondescript advertisement appeared in The Straits Times under the heading ‘Public Amusements’, announcing the opening of the New World at Jalan Besar. The transactions above between DCIT and the Ongs highlighted the special convergence of interests, namely how the value of private enterprises’ vision, albeit cast in business oppor- The New World Amusement Park 287 1923 (Before opening of New World). 1924. 1938. Figure 4. Growth of New World and urban development and densification of the surrounding area. (Source: Singapore History Museum. Graphic overlay by author) tunism, obviously compensated for the colonial government’s lack of resources to enable its own developmental plans outside the Central Area. Private capital was used to develop public infrastructure, which in turn spurred the growth of more shop-houses and hotels. It was specifically the development of a crowd-pulling amenity at an underdeveloped suburban area. For this reason, one could credit the New World as an urban catalyst for the development of the Jalan Besar area (Figure 4). The role of design-leisure, design and landscape of colonial modernity New World in the inter-war years became a harbinger of things modern, where programmes and design played pivotal roles. In reviewing the extant building plan proposals for New World from its inception to 1967, there are several observable patterns, although one cannot really speak of a consistent urban intent or an apparent design consciousness to perpetuate any ‘style’ or ‘look’; and neither can one attribute its design to one single architect. Several architects worked at various stages of the World’s development: E. C. Seah of S. Y. Wong & Co. (1923, 1945), H. D. Ali (1927–1928), Chan Fook Wah (1931–1934), Ho Kwong Yew (1934–1937), United Engineers Ltd (1936–1937) and, after the Second World War, Kwan Yow Luen (1959), Ho Kok Hoe & Ho Kok Yin (1957–1967). There were two distinct phases of extensive building works. The first, through the 30s when the owners decided to expand and make a permanent business out of New World, which started out as a temporary Exhibition. The second, in the late 1950s, was clearly a result of the Korean War boom years. The architecture of New World was ordinary, and included the earliest make-shifts, which were short-lived. Stalls were erected with a lifespan of four to ten years. One could characterize these designs as crudely elemental. With little seasonal variation, open configuration worked well in Singapore for temporary set-ups and as an urban form for a permanent amusement park. The New World opening hours, scheduled to correspond with after-work leisure time, took good advantage of the most pleasant time of the day. The primary framework and layout of the amusement park was settled by the end of 1934; 288 Wong Yunn Chii and Tan Kar Lin and all subsequent works were layered upon and around the established footprint. Changes to façades and appearances were frequent and, through its existence, the park adorned an assortment of thematic settings, as befit the festive occasion or reigning trend. These thematic revisions, although numerous, were piecemeal and minimal. They were not comprehensive overhauls. The pattern of design of the architecture for New World unfolded through the exigencies of market demands, and for this reason, its ‘urban aesthetics’ was fluid, adaptive and opportunistic. In fact, the temporal and pragmatic nature of New World’s architecture and environment contributed directly to its survival. In a volatile and unpredictable business, both the building design and the spatial disposition of buildings had to be rapidly responsive to trends. If they hold any lessons, they are about designing ‘just enough, and just in time’. Since the business of New World was based on affordable mass entertainment, it had to keep running costs to minimum to ensure profit margins. This explains why the extent of architectural works need only be ‘just enough’ to fulfil the advertised promise of a ‘new experience’ to the visitor. Perhaps this is peculiar to the mass entertainment industry, prone to the transient popular taste. Design and programming the business of leisure The programmes in the 1923 temporary New World were organized in two parts: an ‘Exhibition’ precinct for the open-air shows, and another a ‘Football Ground’. Concessions were liberally distributed throughout either as perimeter ‘hawker stalls’ or lots within large ‘sheds’. One visitor to the early New World recounted: The exhibition … is crowded with stalls where inexpensive commodities are to be purchased. At one of these I observed a display of cheap thermos flasks, a popular article, … (And) there are so many refreshment booths. (Bleackley 1994: 210) This reflected directly the business format of the urban amusement park, likely modelled after fairs and exhibitions, while staged shows and performances were the major attractions drawing in the masses. One eye-witness, a former Chinese opera troupe artiste, observed the main source of revenue came from the rental of the numerous stalls selling food, beverages, sundries and other goods (Mak 1988: 77). The calling price for stall rental as well as profits for the operators were thus directly tied to the popularity and patronage of the shows. The business format could account for the logic behind the configuration and layout of the New World, and other amusement parks of the era. To maximize profits made from rental fees, there should be a maximum number of stalls. To achieve high rental fees, these should be optimally positioned on ‘prime land’, accessible and fronting the shows. The shows should thus be spaced apart and evenly distributed throughout the compound, encircled by ample circulation space, which should in turn be lined with stalls, forming a labyrinth of endless shopping (Figure 3: BP 1a–b). This can be seen in the simple but effective layout of the temporary New World in 1923. In the plan, the exhibition ground was separated, by a formal and geometric circulation grid, into four main areas, each dominated by a show area. A singing stage located at the main crossroads was the centrepiece. All the circulation routes were lined with ‘hawker sheds’ at the perimeters, with more elaborate ‘kiosks’ encircling the central area. For the hawkers who usually plied the streets, the amusement park provided a viable alternative for running their small scale businesses. Although itinerant hawkers did not have to pay stall rental and could operate anywhere, they were constantly harassed by aggressive gangsters who claimed streets as ‘territories’ and solicited ‘protection money’. Paying rental for a stall space in the amusement park could also be likened to giving legalized ‘protection money’, but the security of location and a peace of mind were at least assured. Having a ‘captured audience’ within the compound also meant a more stable source of income. To the colonial administration, unlicensed and illegal itinerant hawkers operating on the The New World Amusement Park 289 streets constantly posed a threat to the orderly functioning of the colony, and necessitated continuous policing. In comparison, the amusement park was a tangible demonstration of a fenced-in, orderly and layered exploitation of the economic surplus created by the urban proletariat. It was a spatial typology they readily preferred and condoned. Thus, surveillance and capitalist activities found an almost perfect and mutually beneficial match. Orchestrating the urban fantasy For an amusement park located in the urban setting, a design and marketing ‘problem’ was how to orchestrate a transition from the mundane everyday realm into its world of fantasy and escape. Since visiting patrons did not really need to travel ‘out’ of the city, there was no benefit of a ‘natural’ threshold in the form of physical distance. Architects for the New World obviously gave much thought to this design problem, right from the beginning in 1923. Typically, visitors would start arriving at dusk. As the rest of Jalan Besar receded into darkness, showtime began at the New World. From a side alley — a mere gap in the solid row of repetitive shop-house facades — bright lights and merry music emanated. Turning in, visitors could hear music from an elevated bandstand, ingeniously integrated as part of the entrance, with four booking offices arranged symmetrically on both sides. The whole installation, recessed deep within the alley, was adorned with an eclectic mix of Malay, Roman and Moorish styles, replete with arches, turrets, and spires. The doorway plausibly announced the park’s theme of all-night revelry beyond, an architectural amplification of the bangsawan17 proscenium stage-set, and an act of passing through would transform the visitor into one of the larger-than-life characters to partake in the ornate fantasies of bangsawan melodrama. The magic of the New World was further enhanced by electric lighting, as recounted in one traveller’s account. As ‘a cluster of electric lights cast its radiance upon the actors,’ the night leaped into life at the fringe of town (Bleackley 1994: 210). Over the next four decades, subsequent architects creatively exploited the narrow access condition through a variety of curious entrance follies to announce the new attractions. Turning a constricted access into a dramatic asset by manipulating the scale of this invitation, two understated urban moves were enabled — one, of domesticating what would otherwise be a large space; and, the other, of providing a threshold of suspense and promises. Here, the theme-effect preyed on the mass audience’s desire to escape, amplifying the illusion of slipping away into a fantasy world. With throngs of people pushing past this throat-like entry, the heightened sense of anticipation probably added to the experience. Beyond advertisements and posters, the physical presence of the amusement park in the city held an immediate and material promise of the New World beyond. Even now, the ‘ghost’ of the entrance has not failed to evoke the historical magic. Metamorphosis in the expansion of the 1930s In 1932, New World was rebuilt and expanded into a full-scale urban amusement park based on the design by the architect, Chan Fook Wah (Figure 3:BP2). This new plan departed from the rigid geometry and sparse configuration of the old layout. Nonetheless, the underlying organizational principle is still discernible in the new layout. The raised singing stage previously in the middle of the 1923 Exhibition ground had, in the new plans, been replaced by a Chinese-style Pagoda — a dramatic marker of the visual axis from the main entrance. The newly introduced vertical element, ‘the highest in Malaya’, stood tall amidst the low rise, horizontally distributed expanse of the park, and was the focal point of the common square (Singapore Free Press 1935: Section 2). Just as the ‘shows’ were positioned around the centre of the 1923 exhibition ground, in the new plan, clusters of programmes and the most prominent 290 Wong Yunn Chii and Tan Kar Lin structures were loosely organized around this open space, where the visitor could quickly orientate him or herself upon entering the park. The more substantial building programme included two theatre halls (subsequently named Sunlight Hall and Moonlight Hall) and one City Opera Hall. The Sunlight and Moonlight Halls, symmetrically positioned on both sides of the entrance were still the largest theatres in the New World, supplemented by a smaller Twilight Hall situated towards the middle of the park. Right next to the pagoda was one of the principal new attractions of the park, Cabaret De Luxe. The other, an open-air talkie, enclosed by a perimeter wall, was situated towards the back of the park, where the football field used to be. Back-to-back with the open-air talkie was a new Boxing Arena. Boxing was a favoured spectator sport; besides it took up less space and could be readily programmed which other programmes for a quick turn-around in profits, unlike football matches. In addition, the newly established Balestier Plain Recreational Ground probably made the old facility redundant Concurrent with the extensive architectural works and firming up the footprint of the new urban form, the repertoire of programmes was expanded to offer the visitor an even more extravagant array of entertainment choices. These bold moves were significant enough to be duly chronicled in the centenary issue of the Singapore Free Press. The funds expended in the extension and beautification of New World were such that the issue recorded was sufficient to ‘have opened a new park’. Its shrewd proprietors, who were apparently well-cushioned during the economic downturn, took advantage of the depressed cost in labour, equipment and material. The building activities and opening of new entertainment programmes certainly created plenty of employment opportunities for the construction and entertainment job markets, which were hard-pressed in such bad times. Not only did the amusement park survive through this difficult period, it actually undertook a major physical and programmatic revamping. Programming and the labyrinth of profit The 1932 redevelopment was a major overhaul. Nevertheless, it was based on an existing organizational framework that had been proven to work. The complex circulation network in the new plans was still planned to maximize stall frontage, in line with New World’s primary business strategy of profiting through stall rental. Only this time, however, the integration of business sense into planning was much more developed, and the spatial manifestation was consequently more complex. The new plan also added layering of new programmes and structures upon the old and established. The resultant transformation was almost like the organic growth of a mini-city contained within high fences and inhabited by hawkers, performers and audience. The original spaces and structures have evolved, and the organization of spaces has grown in complexity with the introduction of new elements. In the new layout, structures other than the main buildings, such as eating places or open-air stages, appeared at first glance to be randomly sited with no coherent order or hierarchy. Looking closer, these had actually been planned to cluster loosely around shared open spaces. The clusters and common spaces were fluid and without clear physical boundaries, connected by a meandering labyrinth of stall-lined alleyways. The circulation was planned to create and intensify concentrations of spontaneous activities within each shared open space. These open areas were where people gathered to dance, eat, play, wait or rest depending on the programmes clustered around, generating a sense of bustling and sustained festivity around the grounds. The entertainment programmes were strategically grouped according to their different target crowds. At the same time, keeping the clusters loose and organic maximized the exposure of each programme to potential patrons, especially those housed in open-sided The New World Amusement Park 291 Figure 5. Open air ‘Bunga Tanjong Modern Rhythm’ dance stage in New World, 1949 (Source: National Archives of Singapore) structures, such as the open-air joget or wayang stages18 (Figure 5). New feature rides such as the Ghost Train, Crazy House, and Twilight Hall belonged to the same cluster, sharing a common space with a merry-go-round in the middle. It was nonetheless not a rigid arrangement. To prevent the problem of unsightly backs, not all the main façades fronted the common space. The open-sided stage of Twilight Hall, strategically positioned along a main passageway, was in fact also visible to a neighbouring cluster of eating places. While mothers waited outside for their children to emerge from the Crazy House, they could at the same time enjoy a Chinese drama unfolding on stage. The openness of the clusters, one witness remarked, did not cause undue noise or visual distractions that would detract from the enjoyment of each of the features.19 Rather, the intensity of each cluster was such that one became oblivious to the adjacent features. This strategic clustering of compatible shows or programmes optimized their impact, while the differentiation of target patrons, e.g. children, women, men, families etc, facilitated both their enjoyment and transactions. New World as cosmopolitan crucible of culture At the New World, there was no pre-conceived formal organization, no pretensions of and allusions to squares, plazas and piazzas. The hoardings and alterations to facades, even if one could only characterize them as Potemkin-like fronts were effective and appropriate. Extensive works after 1934 were rare. The entertainment blueprint had been firmly established. However, merely to evaluate either the stylistic architectural merits of the New World or to establish the close connection to the functional limits of its building programme would miss the vital historical dimension of its design. New World offered variety and choice and non-stop offerings that could not be found in 292 Wong Yunn Chii and Tan Kar Lin Figure 6. A Bangsawan Performance, dated 1920. (Source: National Archives of Singapore) traditional cultural and entertainment venues. It was a crucible of new cultural forms, as old contents transformed to meet changing popular taste, and new ones were introduced to suit the diverse crowds. One could say that it was the new business format that accelerated the transformation and commodification of the traditional cultural forms. On the other hand, the cultural constitution of the Ongs, as Straits Chinese, played no small role. In fact, one could argue that the cultural lineage of the Ongs had a decisive influence on the cultural uniqueness of Singapore’s urban amusement park. Ong Boon Tat and Ong Peng Hock came from a lineage of rich Straits Chinese. Like many in their community, their mother, also of Baba lineage, was an avid fan of bangsawan — a new commercial form of Malay opera highly popular with the locals, and recently evolved from Persian theatres that toured the region in the late 19th century (Figure 6). Unlike traditional Malay theatre performed as rituals to propitiate spirits or praise the gods, the entertainment-oriented bangsawan was a travelling commercial theatre meant to generate profits for its proprietors and performers. Bangsawan means ‘aristocracy’ in Malay, and refers to the most popular subject matter of its plays. Its growth in popularity was influenced by the urbanization of colonial Malaya, where rapidly growing towns were peopled by high concentrations of multicultural migrant population, with Malay as the predominant common tongue (Tan Sooi Beng 1993: 8–34). Although the main language used was Malay, the bangsawan as a cultural form was effectively multicultural. In fact, a bangsawan show was always performed on the raised proscenium stage, which was a Western element, rather than the open-air free-standing platforms of traditional Malay theatres. Not only did the profile of audience cut across class The New World Amusement Park 293 distinction, it was also multi-ethnic and multi-cultural, with a fair proportion of Chinese, Straits-born, Indians, Javanese, Arabs, Europeans and Eurasians (Jürgen 1996: 23). In content, the performances adapted freely from stories of different national and ethnic origins: Sometimes within a week, a theatrical company might offer as the evening’s feature play a Hindustani or Arabic fairy-tale, a Shakespearean tragedy, a Chinese romance, and an English or Dutch play. (Tan Sooi Beng 1993: 35) It was not surprising that the bangsawan was singled out as the principal programme when the Ongs opened the New World. In fact, a bangsawan troupe, the City Opera, was founded as resident performers for the park. As the park’s main attraction, the Singapore Free Press centenary issue noted this aspect of the programme in the New World: In deference to the wishes of their late mother … (the Ong brothers) originally specialised in operatic shows until the City Opera, a child of the New World, was according to press opinion considered to be the best opera in Malaya. The tribute to their mother aside, the choice made a lot of business sense. To succeed as a business venture, the New World had to attract the widest possible range of visitors across all social strata, by tailoring its programme to achieve mass appeal. Owing to Singapore’s demographic profile, this meant that the repertoire of programmes had to be necessarily multicultural — and bangsawan fitted the bill. It was further complemented by an array of other popular programmes — Chinese opera or wayang shows, band performances, open-air cinema, and Malay social dances such as joget or ronggeng. The Ongs’ penchant for such an eclectic mix was, one could propose, as much a result of their business acumen as their cultural progeny. One could attribute the credit of this cultural concoction to the sensibilities of their Baba lineage: perched between the east and west, and east and local — two simultaneous liminal cultural positions that were highly tolerant of the eclectic mixes at all levels. The Ongs were not traditionalists, rather they were like most Straits-born who viewed their hybridized culture and the ‘pure’ forms of others from a cosmopolitan angle. This modern view of culture enabled them to collapse culture as entertainment; thus purging the former of the original ritualistic intents and ignoring the problematics of their translatability. In other words, their eclecticism loosened ethnic strictures of cultures. The process of assimilating traditional performance groups, and especially travelling theatres, such as the bangsawan or Chinese opera troupes, to become organs of the urban amusement park, inevitably resulted in the transformation of these cultural forms. Drawn in the first place by the highly attractive deals offered by the amusement parks, they eventually had to change and adapt to a totally different mode of operation and a new environment. In the past, to earn revenue, the troupe would have to pay rent for a venue, before it could stage performances and sell tickets. In contrast, it appeared that the amusement parks provided performance space for free and, in addition, subsidized the troupes with lodging allowance. The urban amusement park provided the traditional travelling theatre groups with a more permanent venue, ascertaining a more steady and regular source of income for the troupes. This arrangement was made possible by the business format of the urban amusement park, where the main earnings came from stall rental (Mak 1988: 77). The synergistic relationship between the urban amusement park and these performance troupes had far-reaching interrelated effects. For a travelling troupe that never stayed long in one location, it could specialize in and keep on repeating a select repertoire, since it performed to different audiences at different places. However, if a troupe was stationed at a permanent location and performed to the same audience week after week, it had to constantly revise its repertoire. According to a former Chinese opera artiste whose troupe performed in the amusement parks, ‘[the programme] cannot be the same everyday… if one day it was this 294 Wong Yunn Chii and Tan Kar Lin show, and the next day it was the same show, [the audience] would not have come back to watch it again’ (Mak 1988: 77). In addition, with a wide variety of shows located within the same compound, competition became more immediate and intense. The troupes were constantly kept on their toes to improve performance standards and to sustain the interest of the audience with novelty and variety. When the bangsawan was assimilated into the urban amusement parks, it featured an improbable variety of shows. To fill in the time between acts, or before and after each play, there would be musical and dance interludes, ranging from ronggeng with lively audience participation, Malay classical chamber music, or even exotic performances such as the Spanish flamenco. There were also guest performances such as ‘illusionist’ magic shows, comic sketches and pantomimes, and even clown acts from a travelling circus. The ultimate crowd-drawer were the boxing matches held on stage, which were sometimes scheduled to occur between acts, with ‘four events of three one-minute rounds each’ (Mak 1988: 39–41). In fact, these probably stole the limelight from the actual bangsawan performance. It was reported that, in the opening months of the New World, 16 first-class boxing contests featuring ‘boxing stars’ and ‘two important’ wrestling matches were hosted (Mak 1988: 39–41). With popular shows drawing in visitors to the amusement park, the operators could collect higher rentals from the stalls on the premise of guaranteed good business. Thus, the efforts of amusement park operators were spent on outdoing each other, actively seeking out the latest entertainment gadget, or the most acclaimed performers who could pull in the biggest crowd. Conversely, popular artistes were often headhunted, while troupes switched between competing parks depending on which had the best offer. Driven by the logic of the market, amusement park operators became the biggest patrons of these cultural forms, thus also as active agents of their transformation and commodification into highly commercialized entertainment. The regularity of performances ensured a steady income for the troupes, who were now committed to the task of drawing crowds for the park, especially for anchor programmes such as bangsawan and Chinese opera. This gradually professionalized the performers as commercial entertainers while the increasing repertoires whetted the appetite of the consuming public. For the audience, this was a whole new experience that was markedly different from simply visiting a theatre. The various cultural and leisure forms were now cast narrowly as entertainment values and given a common space. To be sure, the cultural activities of the New World were commercially driven, audience-oriented, permeated through, and by, media rather than regulated along religious lines or social practices. In the process of being assimilated into the larger market ecology of the urban amusement park, some were hybridized, others were emulated and transformed. With the advent of mass entertainment, there also arose new identities of revellers as consumers, and performers as celebrities — borne of, and dependant upon, the mass market. Renewing desires (The urban amusement parks were) huge playgrounds of cinemas, theatres, cabarets, beer gardens, gaming booths, stalls sporting countless varieties of articles for sale, stadiums, sideshows…20 The New World dazzled the masses with its startling variety of shows and hosts of star performers, complemented on the side by restaurants, watering holes, and unending rows of stalls offering colourful assortments of foods, trinkets, garments and games. Yet, the potency of New World lies in its totality as a ‘spectacle’ — more than the sum of all that it contained. The frequency of these facelifts was driven by the need to draw repeat visitors, by perpetuating the promise of a ‘new’ and ‘different’ world, and constantly renewing the visitors’ desires for an experience behind the fences. This was not unlike how the performing troupes The New World Amusement Park 295 had to constantly reinvent their repertoire. The building works tended to focus on the level of appearance. In fact, they were regular renewals of the ‘picturesque setting’ of the park. This was no doubt intended to induce more spending, by facilitating the visitors’ enjoyment of the entertainment line-up. A whole-year schedule of events such as trade fairs, festival celebrations, and sports competitions provided the occasions for making over the park — be it elaborate renovation works or mere festive embellishments. Like fashion that changes with time, through the years the park structures assumed different ‘looks’ of the day, from the earliest ‘vernacular’ style to art deco facades in latter days. It was clearly not sufficient to depend on superficial facelifts alone to draw the mass clientele. In fact in its expansion programme of the late 1920s, it was evident that New World’s ambitions went far beyond infrastructural and architectural improvements. It was preparing itself to move beyond its role as mere provider of affordable entertainment for the masses — it was going to introduce, and even import, new forms of entertainment to the park, some of which were seen for the first time in Singapore. The Singapore Free Press reported that ‘(t)he proprietors of the New World during the early stage of the park concentrated their undivided attention on keeping interests alive by continually introducing new forms of amusement’. This was a necessary and inevitable move in line with the massive expansion of the park, and central to the effort of sustaining its novelty factor. On the other hand, it was also to stay ahead of stiff competition such as cinema theatres, which were rapidly emerging as a discrete and popular form of urban entertainment. The park thrived on a varied array of constantly renewed programmes and importation of new entertainment institutions or technologies of amusement. Old structures were recycled to accommodate new programmes, as the modes of entertainment evolved and new ones were invented. As entertainment became increasingly technologized, specialized buildings were needed to accommodate these new forms, such as the cabaret, the cinema and amusement rides. For example, the New World cabaret, or Cabaret De Luxe, opened in 1929 and was revamped from the City Opera Hall. It was the first large-scale public cabaret in Malaya, organized separately and outside the context of the exclusive hotel cabarets, which catered for the elite European patrons. Thus, at the New World, the cabaret was transformed from a high-society space into one for ‘mass’ appeal. It became a place of affordable entertainment, serving a broader spectrum of the consuming urban population. The advertising hype for the New World Cabaret was that it offered ‘refined merriment’, featured ‘the longest dance floor in Malaya’, and an accompanying orchestra that was ‘second to none’ (Malaya Tribune 23 August 1934). In addition, there were ‘experienced dancing partners’ or dance hostesses to charm male patrons seeking for a leisurely evening of gracious dancing (Singapore Free Press 1935: Section 2). The cabaret as an urban entertainment form was facilitated as much by the emergence of a generation of young, English educated urban population, as by the ease of regional travels. The new anchor programme of the New World opened with great fanfare, featuring ‘a company of 30 dancing partners and vaudeville artistes, the cream of Manila…recruited personally by Mr Ong Peng Hock’ (Singapore Free Press 1935: 22). The public presentation to this newly introduced anchor attraction was bombastic but accurate: it added a ‘whole new dimension to the world of entertainment … (illuminating) the nightlife of Singapore and Malaya.’ (Singapore Free Press 1935: 22) (Figures 7(a)–(c)). One year later, in 1930, New World boasted another inclusion — the first open-air talkie, showing first-run pictures where previously there were only silent films. Other amusement novelties imported from abroad by The New World Ltd. included The Ghost Train, which was a replica of the one at Dreamland, Margate, purchased by Ong Boon Tat while travelling in Europe. Another item, the Crazy House, copied from Kursal, Southend-on-Sea, Essex was a maze compacted within what looked like a house, fixed with special gadgets such as ‘Eccentric Wheels’ which caused the floor to rock, rattle and slide where the visitor least expected it. As a result of these efforts to keep ahead in competition, the New World took an accelerated 296 Wong Yunn Chii and Tan Kar Lin Figure 7(a). Advertisement of cabaret in the ‘Worlds’. (Source: Malaya Tribune, 31 July 1934) headstart in the depression years as the ‘Pioneer Park of All Malaya’ and trumpeted its achievements: First in Conception & the First to Study the Needs of, & Cater for First-Class Amusements for All Classes. [Authors’ emphasis] (Singapore Free Press 1935: 22) Regular doses of novelty, and continual façade changes became an integral, if not vital, part of the amusement park’s operation to keep up with competition. The extant building plan proposals and approvals for the New World highlight the flurries of activities and dynamic changes in the entertainment milieu and technology. Through the ever self-renewing amusement park, Singapore in the inter-war years was kept up-to-date with rapid technological changes and trends of the day, albeit confined to the leisure industry. Sorting out differences One could characterize the New World as the first seminal modern urban space in colonial The New World Amusement Park 297 Figure 7(b). New World Cabaret, 1930s. (Source: National Archives of Singapore) Figure 7(c). Cabaret, New World. (Source: VICO-NUS, Image#NUS0264) 298 Wong Yunn Chii and Tan Kar Lin society, its heterotopic qualities ensuing from its function as a cosmopolitan promenade with broad civic dimension drawing from a more diverse section of the Asiatic society.21 As an orderly consumption in the colonial-capitalist economy, it was true to the Ong’s own characterization: the New World as a ‘first-class amusement for all classes.’ Prior to the urban amusement parks, the public urban space as a category in colonial Singapore was implicitly segregated and limited in terms of accessibility. The Esplanade, the Padang and Raffles Square, archetypal spaces which contemporary accounts claim as public, were the confines of European society. Their boundaries, although invisible, were explicitly defined by what could be done within them. The presence of Asian bodies in these public realms was incidental; if present, they were mostly and merely service appendages. For example, Maurice Miller, subsequently an inspector of schools in Malacca and Singapore before the First World War, made these observations of the Padang upon arriving in Singapore in 1887: The green sward of the esplanade with the trees and the [St. Andrew’s] cathedral spire in the background made an unforgettable picture, and when animation was lent to it in the evening, by the tennis and cricket players, and the ladies whose custom it was in those days to draw up in their victorias [sic] on the seaside of the ‘padang,’ the scene was pleasing in the extreme. (Miller n.d.: 5) Under British rule, Singapore was expediently categorized and divided, intended to facilitate its efficient management and operation as a strategic trading port in the region. The colonial society was socially stratified — in both their work and social lives, the migrant and domicile communities relied heavily on communal networks for accommodation, jobs, healthcare, as well as leisure. Each person kept to exclusive clubs or closed social circles, which occupied and frequented particular areas — they were spatially segregated in the colonial city. Within these enclaves, were clubs of various sorts (swimming, gardening, weekly entertainment) music societies, mahjong, sports and recreation clubs. Venues of leisure and entertainment, such as hotels, theatres, pubs and restaurants, also catered to specific communities. Although offering a wide range of social activities, these were membership based, confined to the middle to upper middle-class strata, and generally limited to the domiciled population, in secluded areas that were generally inaccessible (Ager 1937: 20). For example, the Singapore Recreation Club in the pre-Second World War years was highly exclusive: Entry into the club was only for Eurasians. And I suppose the definition of a Eurasian was one of mixed parentage. But invariably your name had to be European… I don’t think the Chinese or Indian could join. It was a Eurasian Club. SCC (Singapore Cricket Club) was a European Club… The membership was opened to other nationalities only after the war [WWII]. (Barth 1984: 39) Up to the decade when the New World came into existence, the most substantial massbased ‘leisure industry’ known in colonial Singapore before the New World was the Racecourse. However, to a significant extent, it was a space for spectacle sports, socially segregated and conducted on scheduled days. Under these circumstances, in a society so used to class and spatial segregations in leisure and entertainment, what was it that rendered the urban amusement park a viable, and in fact attractive, alternative option as a ‘public space’? The key was to subtly differentiate the various classes of patrons without complete segregation, while the larger boundary of the amusement park was shared. The New World was the first large urban space for the urban proletariat which consisted of a wide range of under-classes (petty merchants, shopkeepers and workers) and races. The scale was huge and the space was all encompassing, containing behind its high fences all manners of amusements, now made affordable and available to virtually everybody, everyday. Rather than being exclusive to any social group, the various cultural forms were now adapted to allow for different degrees of participation in the show, depending only on the amount of money one The New World Amusement Park 299 could spare. The following description of the bangsawan show, or Malay opera, was also typical of other theatre performances in urban amusement parks: [T]he introduction of amusement parks in big towns made certain that … [bangsawan] performances would become easily accessible to the public. For a charge of 10 cents, the wage-earner could enter the park. If he could afford it, he could pay another 10 cents to $3.00 to sit in the hall where bangsawan was performed; if he could not, he could still stand outside and watch through the doors. He could listen to bangsawan hits played over the air in the parks … (Tan Sooi Beng 1993: 3) In the case of joget, a Malay social dance, the patron could watch the dances from outside the low fence, or he could pay for a seat and a drink at the tables, or even buy a token to join the ronggeng girls on the open-air stage. Differences were somewhat suspended within the fluid realm of a ‘new world’, as people enjoyed the show together, sharing a common space and moment. The loosened boundaries of the urban amusement park afforded everyone glimpses into the different cultures, practices, and leisure life of the diverse people living in Singapore, at a time when there were few such opportunities. The intrigue of the exotic was integral to the overall appeal of the urban amusement park. For the diverse immigrants who had come to Singapore with the sole shared purpose of earning a living, day-to-day encounters with different ethnicities and cultures were limited, since most depended on self-help institutions within their own communities for shared resources such as accommodation, jobs, medical treatment, and leisure. The urban amusement park was then a different world where visitors could even participate in the leisure activities and cultural performances of the various communities, all at once, within a single common space. Bruce Lockhart, a Malayan rubber planter in the 1910s, upon returning to Singapore in 1936 and visiting the New World, observed that: The crowd was of all classes and of all races. Naval ratings towered over squat Malays. If Chinese predominated, there was a fair sprinkling of Europeans and Eurasians. Tamils, Japanese, Arabs and Bengalis completed the racial conglomeration. The noise was deafening. Next door to an open Chinese theatre with the usual accompaniments of gongs, a Malay operatic company was performing … From the side-shows came an endless broadside of chatter and laughter. In the booths in the centre, Japanese and Chinese were selling toys which would have delighted the heart of any European child: voracious-looking dragons, clock-work crocodiles and snakes, miniature baby-carriages, wooden soldiers, and the quaintest of domestic animals… (Lockhart 1985: 239) Day after day, and not just on festive occasions, they could observe at close quarters how other communities socialized and partook of leisure, and even interact with them at a time and place outside of work and the mundane everyday. In fact, the patrons themselves had also become part of the show, each an unselfconscious display of exotic difference to the other, in this cosmopolitan promenade of people from all walks of life. To the performers, being stationed in an urban amusement park exposed them to, and enabled them to, learn new types of music and performance arts. This would not have been possible if the troupe was travelling, or performing in exclusive theatres. Zubir bin Said, acclaimed Malay musician who, in the inter-war years, was with a bangsawan troupe in the amusement parks, recalls learning Chinese music there, through watching the Chinese opera during the breaks (Zubir 1984: 86). The urban amusement park was surely intended by its operators as a business venture to cream the spare cash off the majority wage-earning population. It was scarcely conceived with 300 Wong Yunn Chii and Tan Kar Lin altruistic community support or cultural promotion in mind. Yet, as a result of a business concept that aimed to profit from the mass market, it could not afford to be exclusive. Intentions aside, the urban amusement park nonetheless presented a potential social space for people of different cultures, creeds and classes to rub shoulders, where one did not exist. Eventually, the urban amusement park took on the critical role of a sizeable social gathering space for the diverse Asiatic society of Singapore. Other than regular programmes, the urban amusement park also played host to charity events. New World organised a ‘Gala “Charity” Ball’ in 1934, of which all entrance fees were donated in aid of the Tiong Bahru Fire Relief Fund.22 Throughout the years of their existence, the amusement parks were popular venues for many community fund-raising performances and even politically-charged activities, such as the anti-Japanese propaganda speeches in the inter-war years up until the post-independent political rallies in the 1060s (Choo 1984: 15). Charity acts on the part of the amusement parks were loaded with populist marketing and hypes; nonetheless, they remained vital ground-up initiatives with community interests. The Europeans frequented the New World as well. However, they stood apart from other communities, including the Eurasians, and did not seem to identify with the New World as part of their own leisure landscape. They were more like visitors to a curious and exotic attraction, amused by a spectacle of native or migrant settler’s leisure and social life. The account of Horace Bleackley, a British novelist who travelled to Singapore in 1925, exemplifies: [T]here are few public amusements in Singapore for English people… The natives, on the other hand, are well catered for. On the outskirts of the city an open-air exhibition — called ‘The New World — is run for their benefit… and [my host] insists upon taking his clients to visit the place. It is well worth a visit, for the enlightenment it affords into native life… (Bleackley 1994: 210) At the New World, the vulgar coexisted with the refine, the low with the high, the ethnic with the contemporary — all subsumed under the space of a profit-driven and seemingly egalitarian urban entertainment. It was an organized opportunity ‘to watch’ people, and watching people watching others — almost in an endless loop through tentative peeks into the amusement park, enveloped by band music which accompanied shows and broadcast across the whole park. Conclusions The spatial and architectural characteristics of the New World were integral to its commercial success and facilitated its role as a space and as an emergent urban form for cultural and social transformations of colonial Singapore in the inter-war years. Naturally, one cannot adequately claim that urban amusement parks, such as the New World, are a unique urban-spatial typology, since clear antecedents could be traced to exemplars like those in Shanghai and the west. Nonetheless, as a case, New World offers us an opportunity to review mainstream historical scholarships, which generally attribute the efforts of elite colonial British society as the dominant forces of modern life in Singapore, by installing a legacy of legal, economic, transport and urban infrastructure. By following the emergence and early evolution of the New World amusement park, it is evident that another aspect of colonial modernity was due no less to the roles of non-European private capital, entrepreneurs, design professionals and artistes. The New World, as described and analysed, is a supreme example of a reified space in the colonial Singapore of the inter-war years. It physically enabled, in a seamless continuum of its labyrinthine spaces, the groupings of classes that would otherwise remain segregated. This was done under, and reinforced by, the euphoria of leisure consumption. The demise of the New World amusement park by the mid-1960s was neither because it was unable to keep up with the emergent technologies of entertainment nor that it was unable to find new forms of The New World Amusement Park 301 distraction. Rather, the evidence shows that its owners had the resources and means to innovate continually. The problem was social structural and external. And the concept of a space for all ‘classes’ carried within its seed of initial success, also its own eventual undoing. By the 1960s, this formula had become anachronistic as classes found their respective niches more appealing. The primary contributing factor to the park’s demise is that the pattern of leisure spaces began to be increasingly demarcated along class-lines, as social stratification of the domiciled, post-independent populations settled in. New World provided, in very tangible terms, the profile of the landscapes of inter-war modernity in colonial Singapore. Under the colonial backdrop of class segregation by race, New World showed that the ethnic distinction was less an issue than class in Asiatic society, at least while its members were suspended in the euphoria of the World’s eclectic entertainment environment. In as sense, this was a de facto landscape of modern life, lying outside the dominant modernities circumscribed by the colonial agents and their instruments. In the same vein, the urban entrepreneurialism of New World spurred an alternative form of urban aggregation outside colonial governance, and serendipitously served as a model for the similar parks to pioneer the settlement of land at the edge of the colonial gaze. The study of the history and design of the New World is valuable at several levels. First, it offers a different route for understanding the modern leisure industry, especially in the context of a colonial setting. In contrast to the plethora of studies of popular cultures (Bennett 1995, Sorkin 1992) that are underpinned by implicit and fundamental class homogeneity, either the elite or the middling sort, the lesson of the New World is unique. It showcases how design could create an idealistic setting for a wider spectrum of class enclaves within one precinct, yet ably adverting potential class antagonisms. Thus, while the labyrinth directly transformed the bodies of working class to a mass spectacle, it also insulated the middle classes in the internal environments of their preferred cabarets and ‘kinemas’. However, when these environments proliferated outside the amusement park, their captured audiences departed in droves. Even the palatial fantasy and electric grandeur of the New World at this point were inadequate enticements, as its audience awoke from the slumber of the make-believes and headed for their respective class niches. Second, New World is unique in its offerings and means to captivate the mass audiences. Amusement parks in the west, from the start, through their rise, ebb and recovery in the 1950s, were singularly impelled by technology, almost to a point of obsession. This is especially true of the emblematic midway rides; even subsequent theme parks are enabled by elaborate technological infrastructures. Cultural entertainments, such as the American vaudeville theatres, minstrels, ragtime shows, tend to be confined to specific urban locales, and when they were incorporated as part of amusement parks, they remained as secondary side-shows. New World on the other hand, quickly thrived on the early commodification of cultures, and with the rooting of heretofore travelling performances, also standardized, professionalized and institutionalized mass entertainment in the colony. Urban entertainment at the New World, through the active alchemy of new forms of culture and entertainment, was thus Singapore’s proto- culture industry, transforming what had been popular practices into mass-culture. New World and all the other subsequent amusement parks were special consumptive and productive spaces of a Malayan cultural smorgasbord. Finally, New World also foregrounds how leisure entertainments provided a dimension of contact with modernity. Immediately and directly, this was through the technologization of entertainment, spurring new visualities and consumption modes, with the rise of trade fairs and advertisements in public places. Indirectly but more importantly, through the spaces of New World, a condensed and charged defamilarization of the cultures of Asiatic society was enabled. Under the eclectic cosmopolitanism of the bangsawans, jogets, kinemas, cabarets, contact sports, etc, the appearances of the others at first so foreign and so quaint, became accessible through exchanges and recognizable through performances. 302 Wong Yunn Chii and Tan Kar Lin Notes 1. This is a substantially expanded version of the paper presented at the conference on ‘Shaw Enterprise and Asian Urban Culture,’ 26–28 July 2001, Department of Chinese Studies-NUS. 2. The first commercial wireless station was set up in 1915, and British Malayan Broadcasting Corporation was set up in 1936. Work on the Seletar Aerodrome commenced in 1927, and Singapore became a popular stopover for flights from Europe to East Asia. 3. Huang Chujiu was an accomplished business man in Shanghai, well known in the 1920s to 1930s for his entrepreneurial spirit and pioneering ventures into the entertainment business. According to Fu Xiangyuan, Huang first introduced the ‘roof-top amusement park’ to Shanghai, borrowing the idea from Japan (Fu 1999). 4. Ong Boon Tat was a distinguished Straits Chinese, serving as a JP and Fellow of the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce. His father, Ong Sam Leong (b. 1857) built the family’s wealth in timber trade, brick works (Batam Brickworks) and rubber estates. Mrs Ong came from an old Baba family as well, by the surname of Yeo. For more details of the Ong family, see Song (1984: 98-100). 5. Shaw’s Singapore official website (http://www.shaw.com.sg/shawstory/shawstory2a.htm) noted: From the mid 30’s to the 80’s the Shaws operated two highly popular fairgrounds. They were the Great World at Kim Seng Road and New World at Jalan Besar. Shaw’s initial involvement in the New World came as a 50/50 joint venture with the latter’s parent company, Ong Sam Leong Ltd. (The Shaw Organization 2001)However, the post-war registry of business (Directory of Registered Business Names & Companies of Singapore, Bleackley 1949, p. 371) suggests that the aforementioned venture was probably initiated under an entity called ‘Peng Hock & Shaw’ only in 1938. Its paid up capital of $100,000 contrasted starkly with the SS$1 million. of ‘The New World Ltd,’ established in 1932 — with Ong Peng Hock, Ong Tiang Wee and Ong Tiang Guan as the company’s directors. Although both companies were listed as ‘amusement park proprietors’, it is probable that the latter was a primary holding company of the real estate represented by the site. Similarly, the The Registry of Companies in the National Archives of Singapore shows that New World Ltd was registered in March 1932 until July 1955. It was re-listed as New World (1958) Pte. Ltd. in March 1958 until October 1975. From 1923 to 1932, New World was probably run as part of Ong Sam Leong Trading Co. Ltd. (1920–1928) and Ong Sam Leong & Sons (1932–1961). 6. The success of urban amusement parks in Shanghai was the reason why the Shaw brothers decided to join the venture with the Ongs. Tan Sri Dr Runme Shaw offered:Amusement park in Shanghai was very popular. They had two parks in Shanghai. One was called New World, the other was called Great World. We thought this was suitable for this place (referring to Singapore). So we tried to run the amusement park. (Shaw 1981: 9) 7. Tan reported that, by the late 1960s, amusement parks in Malaysia were not lucrative, and faced stiff competition from more accessible entertainment like films, televisions and night-clubs (Tan 1984: 4ff) 8. See proposal for a mega mixed development of the site by City Developments Ltd. as Hong Leong City in ‘CityDev’s New World Project to start next year’, Business Times, 21 December, 1992, p. 3 and The Straits Times, 20 October 1992, p. 39. CityDev bought the site from the Shaw Organisation in April 1987.The exact end of the ‘Worlds’ remain speculative, though one author, Jurgen Rudolph, offered eye-witnesses’ accounts that Teochew operas were performed there as late as 1969 and 1970 (Jürgen 1996: 21–22). 9. A dhoby refers to an Indian who held the traditional occupation of a washer-man. 10. The shop-house refers to a typology of mostly two- to three-storey terrace row housing, where the ground floor is a place of business while sleeping and living quarters are situated above. In the Malayan context, the ground floor unit is usually recessed, forming a continuous colonnaded and sheltered walkway known as the five-foot-way. 11. Kampong Kapur to the south of the proposed site was an Indian Muslim settlement, while Malay communities predominate to the east in Kampong Boyan. 12. S. Y. Wong was one of 16 architectural firms listed in the Directories of 1926, the critical year of the passing of the Architect’s Ordinance, and in early 1927 (Seow 1972). 13. Annotations on Bldg. Plan 1412/23, 21 June 1923: ‘Proposed Temporary Exhibition & Recreation Ground — ‘The New World’ (including a football field) Behind North side of Jalan Besar’ in the National Archives of Singapore. 14. Annotations on Bldg Plan 1412/23, 21 June 1923 in the National Archives of Singapore. 15. DCIT Memo, SIT (Municipal Office) Bldg 1412/23, 21 June 1923 in the National Archives of Singapore. 16. Exchanges of letters between DCIT, Mr Ong Boon Tat and the lessee’s Architect’ in the National Archives of Singapore. 17. The bangsawan is a form of commercial Malay opera with culturally eclectic contents, performed on a Western proscenium stage. The New World Amusement Park 303 18. Both are Malay terms: joget refers to dance, though in contemporary use, joget is now taken to represent a type of traditional Malay dance with a fast-paced beat, accompanied fast hand and leg movements. Wayang means theatre in the broadest sense through, it is often associated with Chinese opera. 19. Notes from authors’ interview with Mr Ho Kok Hoe (21 July 2001). Mr Ho’s practice, with his brothers, under Ho Kwong Yew & Sons, was responsible for several major posts in the New World. 20. Singapore Free Press, Happy World Supplement, 27 April 1937, p. 1. 21. Colonial Singapore had a predominantly migrant population, made up of people who came from diverse backgrounds, and who grew up in vastly different societies and cultures all over the world. According to the Census of British Malaya 1921, there were then six main racial divisions, Europeans, Eurasians, Malays, Chinese, Indians and ‘Others’, the last category included the Japanese, Arabs and Filipinos (Nathan 1922: 70). 22. The event was covered in The Malaya Tribune, 23 August 1934, p. 9. References Ager, A. P. (1937) ‘Singapore as it used to be’ in Straits Times Annual, Singapore. Barth, Ronald H. (1984) Transcripts of interview conducted by the Oral History Department, National Archives of Singapore, 10 February, Acc#394 Bennett, Tony (1995) The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics, New York: Routledge. Bleackley, Horace (1949) Directory of Registered Business Names & Companies of Singapore, Singapore. Bleackley, Horace (1994) ‘The Europe and Raffles Hotel (1925 — 26)’ in John Bastin (ed.) Traveller’s Singapore: An Anthology, Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. British Malaya (1930) ‘Malaya on Mail Day’, 5(2) June. Choo, Cheng Meng (1984) Transcripts of interview conducted by the Oral History Department, National Archives of Singapore, 30 August, Acc#472. Edwards, Norman (1990) The Singapore House and Residential Life 1819–1939, Singapore: Oxford University Press. Fu, Xiangyuan (1999) A Popular History of The Great World , Shanghai: Daxue Chubanshe: . Gwee, Peng Kwee (1981) Transcripts of interview conducted by the Oral History Department, National Archives of Singapore, 11 November Acc#128. Ju;aurgen, Rudolf (1996) ‘Amusements in the Three “Worlds” ’ in Sanjay Krishnan, Lee Weng Choy et al. (eds) Looking at Culture, Singapore: Artres Design & Communications, 21–33. Lee, Ou-fan (1999) Shanghai Modern: the Flowering of a New Urban Culture in China, 1930–1945, London: Harvard University Press. Liu, Gretchen (ed) (1999) Singapore — A Pictorial History 1819 — 2000, Singapore: Archipelago Press (in association with National Heritage Board). Lockhart, R. H. Bruce (1985) ‘Secret shame’ in Michael Wise and Wise Mun Him (eds.) Traveller’s Tales of Old Singapore, Singapore: Times Books International. Mak, Siew Wai. (1988) Transcripts of interview conducted by the Oral History Department, National Archives of Singapore, 3 July, Acc#946. Miller, Maurice (n.d.) Unpublished MSS, c.1950 ‘Part II, Malacca Memories’. In Cambridge University Library. Royal Commonwealth Society Collection, British Association of Malaya (BAM). Nathan, J. E. (1922) The Census of British Malaya 1921, British Malaya: Malayan Civil Service. Seow, Eu-Jin (1972) Architectural Development in Singapore, PhD Dissertation, University of Melbourne. Shaw, Tan Sri Dr Runme (1981) Transcripts of interview conducted by the Oral History Department, National Archives of Singapore, 4 December. Shaw Organization (2001) ‘The Shaw Story’, Http://www.shaw.com.sg/shawstory/shawstory2a.htm. Siddique, Sharon and Nirmal Shotam-Gore (eds.) (1983) Serangoon Road: A Pictorial History, Singapore: Education Publications Bureau. Singapore Free Press (1935) Centenary Number, 8 October, Section 2. Singapore and Malaya Directory for 1922 (1922) Singapore: Fraser & Neave, Limited. Song, Ong Siang (1984) One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore, Singapore: Oxford University Press. Sorkin. Michael (ed.) (1992) Variations on a Theme Park: The New American City and the End of Public Space, New York: Hill and Wang. The Straits Times (1980) ‘$300million Complex Planned at the New World’, 8 February. Tan, Sooi Beng (1984) ‘Ko-Tai: a new form of Chinese urban street theatre in Malaysia’, ISEAS Research Notes & Discussion Paper No.40. Tan, Sooi Beng (1993) Bangsawan: A Social and Stylistic History of Popular Malay Opera, Singapore: Oxford University Press. 304 Wong Yunn Chii and Tan Kar Lin Turnbull, C M. (1989) A History of Singapore 1819–1988, 2nd edn, Singapore: Oxford University Press. von Sternberg, Josef (1998) ‘Great World entertainment building’ in Barbara Baker (ed.) Shanghai: Electric and Lurid City, New York: Oxford University Press. Yeoh, Brenda, S. A. (1996) Contesting Space: Power Relations and the Urban Built Environment in Colonial Singapore, Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. Zubir bin Said (1984) Transcripts of interview conducted by the Oral History Department, National Archives of Singapore, 16 August, Acc#293. Author’s biography WONG Yunn Chii is a lecturer in architectural history in the Department of Architecture, National University of Singapore. His interest is in the study of modernity as process and as an idea in architecture. Recently, he has been examining the use of postcard views and images as material culture for the study of colonial architecture and modernity of British Malaya and the Straits Settlement. He is also an active member of mAAN — modern Architecture in Asia Network, a loosely associated clusters of researchers interested in the built environments of the recent past. Contact address: Department of Architecture, 4 Architecture Drive, Singapore 117566 TAN Kar Lin is an MA (Architecture) candidate at the Department of Architecture, National University of Singapore. She is currently writing her dissertation on Singapore’s early urban entertainment parks and their influence on urban development, urban culture, consumption and leisure in the colonial milieu. She was former Editor of the journal Singapore Architect, where her writings on architectural criticism and urban studies have also been published. She was also the co-writer of Building Dreams, an eight-episode info-documentary TV series on Singapore architecture and urbanism, aired in 2001–2002. Contact address: Highgate Crescent, Singapore 598783