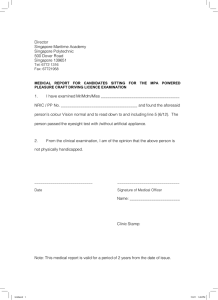

C Cambridge University Press 2011 Modern Asian Studies 46, 1 (2012) pp. 167–191. doi:10.1017/S0026749X11000618 ‘The Modern Magic Carpet’: Wireless radio in interwar colonial Singapore CHUA AI LIN Department of History, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, National University of Singapore, 11 Arts Link, Singapore 117570 Email: hiscal@nus.edu.sg Abstract Wireless radio broadcasting in colonial Singapore began with amateur organizations in the early 1920s, followed by commercial ventures and, finally, the establishment of a monopoly state broadcasting station. Listeners followed local broadcasting as well as international short wave radio. Both participants in and the content of radio reflected the multiracial, cosmopolitan make-up of a colonial port city which functioned through the lingua franca of English. The manner in which early broadcasting developed in Singapore sheds light on the creation of different imagined communities and the development of civil society. There was an increasing presence of non-Europeans, women, and youth, many of whom were drawn by the mystique of this new technology. Wireless radio also brought about a transformation in the public soundscape. These themes contribute to our understanding of the global history of radio as well as the nature of colonial societies within the British empire. Introduction Described as ‘the Clapham Junction of the Eastern Seas’,1 Singapore in the 1920s and 1930s was a highly modern place, and self-consciously so. New technologies such as motion pictures and gramophone records arrived in Singapore not long after they became commonplace in the West and were enthusiastically received by the population. Although radio broadcasting only became widely popular in the 1950s in Singapore, its early history is an important window on the social, 1 Frank Athelstane Swettenham, British Malaya: An Account of the Origin and Progress of British Influence in Malaya, revised edition (London: Allen & Unwin, 1948; reprint, 1955), p. 342. Swettenham served as Governor of the Straits Settlements (Singapore, Penang, and Malacca) from 1901 to 1904. 167 http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 168 CHUA AI LIN cultural, political, and economic processes taking place in a thriving, cosmopolitan port city under the British empire. This is a story that brings to the foreground individual, community, and commercial forces which operated alongside or in place of official action and administration, giving a more rounded understanding of colonial society. In contrast to the well-developed body of scholarly research on colonial administrations and political structures, cultural history—including the cultural and social history of everyday technologies—offers much that remains to be studied. While making a contribution to our understanding of how colonialism and empires functioned, the history of new technologies like wireless radio illuminates the way in which modernity and modern things precipitated changes at various levels. The potential of historical cultural studies has been demonstrated by the many works on the impact of the telephone, gramophone, radio, and television on American society in particular, but these approaches to modern technology and media have yet to be adopted for many parts of the non-Western world, including Singapore. A common approach to studying multiracial colonial societies is to focus on either the European, colonial sphere, using primary documents in the language of the colonizer, which are often of an official nature, or to focus on specific local, ethnic communities, using vernacular sources. However, a third angle is particularly useful for interwar Singapore. As a highly multi-ethnic society, with a critical mass of English-educated non-Europeans who came from a wide variety of ethnic backgrounds, applying the linguistic category of ‘Anglophones’ opens a window onto a vibrant contact zone whose lingua franca was English, where British, European, and American technology, individuals, and ideas interacted with the Chinese, Indian, Ceylonese, Eurasian, Malay, Japanese, and other diverse elements of this port city. Overall, the development of radio in interwar Singapore is a story of the creation of new communities on an everyday level. These audience communities operated at differing levels of geographical scope and took on a civic dimension which widened to include new participants among women and Asian listeners. While broadcast audiences formed a very public grouping, it was the ability of radio to penetrate the private realm of the home that enabled it to draw so many into these new listening communities. At this early stage in its history it was the novelty and mystique of this marvellous new technology that helped the radio to win a hold over the imagination and attention of its audiences. http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 RADIO IN INTERWAR SINGAPORE 169 Broadcast media and the creation of imagined communities The uneven and patchy development of wireless radio broadcasting in Singapore illustrates very clearly the process by which the mass media can create communities of listeners. Anderson focused on print culture in the forging of an imagined community of the nation,2 and broadcasting media functioned in a similar way but often in tension with established political entities. In her study of how broadcasting shaped the American imagination, Douglas points out that while it is commonplace to apply Anderson’s conclusion and assert that ‘radio built national unity’, at the same time, radio also allowed a multitude of regional and local identities to flourish, some in line with national ideologies and others contesting them.3 This kind of diversity was perhaps only to be expected in the United States, where the airwaves were filled by numerous private and commercial stations. In contrast, the British model of broadcasting instituted one governmentappointed monopoly broadcaster, which in the United Kingdom was the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). The intention was for colonial policy to follow the British model, but in practice state intervention was late in coming to British Malaya, of which Singapore was the infrastructural, administrative, and commercial centre. The relatively unregulated sphere of early broadcasting in Singapore thus reveals a trajectory quite different from the image of territorial or imperial unity implied by the policy of monopoly broadcasting. Looking closely at the process by which imagined communities were created and shaped, we might expect their creation to be a function of distance, starting with the closest and gradually expanding to include people and places increasingly far away. Even the newspapers discussed by Anderson had to be physically transported to readers, and circulation was a function of distance and time. However, the physical constraint of distance did not exist with wireless radio broadcasting and instead communities were dependent on radio technology and the emergence of broadcasters at various levels. Local broadcasting began in 1925, soon after the Amateur Wireless Society of Malaya was formed by a group of enthusiasts in Singapore. Among the various societies in Malaya formed to promote interest 2 Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1983). 3 Susan J. Douglas, Listening In: Radio and the American Imagination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004), pp. 23–24. http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 170 CHUA AI LIN in wireless radio, this society was the first to experiment with transmitting programmes.4 It was founded by European expatriates, most of whom worked in companies with an interest in wireless radio, such as General Electric, Marconi, and Standard Telephone, and from whom the society was able to receive support in terms of funding and equipment.5 Its station, which was called ‘1SE’ (1 Singapore Experimental) and transmitted on the medium wave band, was granted a temporary transmitting licence by the Straits Settlements government.6 However, by January 1928, facing declining financial support and interest from its members as well as technical problems with transmission and reception, the society ceased its transmissions. From 1928 to 1933, the only local broadcasting that existed comprised three amateur short wave stations run by individuals from the Amateur Wireless Society of Malaya, including the president, F. B. Sewell, and vice-president, R. E. Earle. Sewell’s station was rarely active, while Earle was once reported to have forgotten to put on his regular Wednesday evening transmission, indicating the infrequent and unreliable nature of private stations run by individual amateurs.7 During this period radio listeners in Singapore were not limited to these local stations. Listeners were more likely instead to tune into literally an entire world of broadcasting via their short wave receivers. The daily radio schedules published in the newspapers show that in 1931, the Singapore listener’s daily options included stations from Saigon in French Vietnam, and Bandoeng, Tanjong Priok, Batavia, Sourabaya, Medan, and Djokjakarta from the Dutch East Indies, as well as stations further afield in Melbourne, Sydney, Paris, Rome, Eindhoven, Zessen, Nairobi, New York City, and Moscow.8 With poor offerings in terms of local broadcasting, international short wave transmissions formed the bulk of a Singapore resident’s listening. 4 ‘Listening-in’, Straits Times, 7 May 1925, p. 9. Fred Keller, ‘Work of the Pioneers in Malaya’, Omba Pende, September 1931, p. 2; ‘Programme of Singapore Amateurs’, Straits Times, 8 April 1925, p. 1. 6 ‘Wireless in Malaya’, Straits Times, 28 December 1925, p. 11; ‘Bancam’, ‘Work of the Pioneers in Malaya. I – History of the A.W.S.M.’, Omba Pende, August 1931, pp. 16–17; Drew O. McDaniel, Broadcasting in the Malay World: Radio, Television, and Video in Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore (Norwood, New Jersey: Ablex Publishing, 1994), p. 24. 7 ‘What’s on the Ether?’, Omba Pende, July 1931, p. 16; ‘Singapore’s Experimental Station’, Malayan Radio Review, 20 June 1932, pp. 3–4; ‘Z.H.I. Singapore Calling’, Radio Magazine of Malaya, 1 February 1936, pp. 9–10. 8 ‘What’s on the Ether?’, pp. 16–17. Reception reports were also published in the Malaya Tribune’s daily column ‘To-day’s Radio’. 5 http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 RADIO IN INTERWAR SINGAPORE 171 However, powerful short wave receiver sets were expensive and few people could afford them. Foreign programming also did not fulfil the need for local content, not only in terms of entertainment but also for news and market reports, and in a language that listeners could understand. In the opinion of the Amateur Wireless Society of Malaya, ‘broadcasting is not a luxury but a necessity to a civilised country’ and official involvement in broadcasting was necessary—whether at the level of a short wave empire-wide service, or at the local level—in order to ensure a reliable service.9 In 1931, the society was re-formed with the aim of petitioning the government on broadcasting matters. At this time, the BBC was also making plans for its Empire Service, which began operating on 19 December 1932. Correspondingly, a reliable radio schedule of ‘Empire Radio To-Night’ was published in the Singapore daily press, a vast improvement compared to pre-Empire Service days when the Malaya Tribune relied on its readers to submit reception reports and schedules of ‘likely transmissions’. The role of wireless radio in shaping and bolstering an imperial identity had been widely recognized from very early on. In early 1924, advertisements by the newly incorporated Malaya Broadcasting Company read: The printed word has had an effect, the potency of which does not need emphasis today, but the appeal of the human voice, reaching hundreds of thousands – nay, millions – of people, simultaneously, opens out vistas that stagger the imagination. . . words fail to express the effect that will be produced throughout Great Britain, when on the occasion of the opening of ceremony of the British Empire Exhibition, on the 23rd inst., His Majesty the King speaks to his subjects. . . It will be more difficult to imagine the overwhelming effect that will be produced throughout the King’s Dominions, when His Majesty the King-Emperor, for the first time, speaks to his subjects overseas. . . and when the King speaks, will you in British Malaya want to hear his voice? Are you ready to listen-in to His Majesty the King?10 Despite the formation of the Malaya Broadcasting Company in Singapore as early as 1924, the failure of the Straits Settlements government to live up to its promise to issue a transmitting licence resulted in the company lying dormant.11 On another level, an awareness of the empire impacted on everyday life through the marking of dual time—the local time as well as Greenwich Mean Time, sounded by the chimes of Big Ben on the Empire Service. A 9 ‘Five dollars for nothing’, Omba Pende, July 1931, p. 3. Quoted in a letter by Powell Robinson of the Malaya Broadcasting Company Ltd., to Omba Pende, August 1931, p. 24. 11 ‘Broadcasting’, Straits Times, 29 June 1931, p. 18. 10 http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 172 CHUA AI LIN Malaya Tribune editorial entitled ‘Big Ben links Empire’ emphasized this, saying: ‘remember that to us out here, it is the day’s worst disappointment when someone is allowed to talk through the time for Big Ben to strike’.12 Over time, the regular chimes of Big Ben would have taken on a warm familiarity for Malayans, associated with a steady reliability and the pleasures of radio listening. Not long after the introduction of the Empire Service in Singapore in mid-1933, listeners were finally able to enjoy reliable, professional, domestic broadcasting on a daily basis with the launch of Radio ZHI, a commercial station owned by the Radio Service Company of Malaya.13 ZHI was broadcast on the 49 metre short wave band which, unlike other short wave bands, could also be received by crystal receiver sets. Simple and affordable, crystal receivers were often constructed at home by amateurs during the early days of radio. The 13, 16 and 19 metre short wave bands used by the BBC required more sophisticated and expensive valve receivers.14 The ZHI short wave signal was clearly received by listeners not only in Singapore but across Malaya, who appreciated the strong and reliable radio signals compared to those of the more distant stations. The thrice-weekly ZHI programme line-up featured mostly European gramophone music, talks in English, and live music relayed from local dance halls, as well as occasional Chinese, Malay, and Indian music. By February 1935 ZHI began making plans to increase the amount of Asian content, and a year later even faced the problem of which Chinese dialect to give prominence to in its vernacular music programming.15 However, at the end of December 1936 ZHI was closed down, despite unhappiness from faithful listeners across the peninsula. The reason was that the Straits Settlements government had always intended to organize broadcasting along British lines, with a transmission licence awarded to a single monopoly broadcaster for the whole of British Malaya. The official policy was finally drawn up in 1934, and the licence awarded in July 1935 to a new enterprise, the British Malaya Broadcasting Corporation (BMBC). At the same time, Radio ZHI’s 12 ‘Big Ben links Empire’, Malaya Tribune, 24 June 1933, p. 15. Advertisement for the Radio Service Co. of Malaya, Omba Pende, August 1931, p. 17; Singapore and Malayan Directory (Singapore: Singapor Printers Ltd., 1936), sub voce ‘Radio Service Co. of Malaya’. 14 Details of broadcast frequencies were published regularly in the radio programme listings in the daily newspapers. 15 ‘First News of New Features for Malayan Broadcasting’, Straits Times, 6 February 1935, p. 5; ‘Chinese Music on the Air’, Straits Times, 9 June 1936, p. 12. 13 http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 RADIO IN INTERWAR SINGAPORE 173 transmission licence terminated.16 The thinking of policy-makers was that the British Malaya Broadcasting Corporation was to be the first local broadcaster to serve the masses across the entire Malayan peninsula. Transmissions would be in the medium wave band, which did not require expensive short wave sets, and powerful transmitters would ensure that signals could be received across the country. However, these grand plans were very far from the situation that faced Malayan listeners in 1937. The first British Malaya Broadcasting Corporation broadcasts, using the call-sign ZHL, were only accessible to listeners in Singapore and Johore, the southernmost state on the peninsular mainland. It was only in July 1938 that the British Malaya Broadcasting Corporation finally started short wave transmissions that could be received across the peninsula.17 In March 1940, with the approach of war, the colonial government realized the potential of broadcasting as a propaganda medium and decided to buy the British Malaya Broadcasting Corporation, reorganizing the company as the Malayan Broadcasting Corporation (MBC). The government planned for the Malayan Broadcasting Corporation to be the most impressive station outside of Europe, and the intended Far Eastern Radio Service was to have broadcast regularly in 26 languages and dialects. However, these grand plans were forestalled by the Japanese invasion of Singapore in February 1942.18 This brief account of Singapore’s radio history reveals a complex landscape of broadcasting at different levels—international and local—which in turn was a function of the transmission distances of different frequencies. The broadcasting mass medium initially did little to create a local community of listeners. Instead, a diverse range of international short wave stations grabbed the imagination of audiences who were amazed at the ability to connect with distant places, cultures, and languages. In the world of radio, the listeners’ abstract knowledge of world geography was put into practice and made tangible, albeit transposed into the form of megahertz, international time zones, incomprehensible tongues, and a smorgasbord of musical styles. As one Philips advertisement emphasized, radio was ‘the key to 16 ‘Radio Listener’s Disappointment’, Straits Times, 18 December 1936, p. 3; ‘Closure of ZHI: The Reason’, Straits Times, 19 December 1936, p. 12; ‘Listeners’ Protest at Closing of ZHI’, Straits Times, Radio supplement, 23 December 1935, p. 1. 17 ‘All-Malaya to Hear ZHL’, Straits Times, 17 July 1938, p. 2. 18 McDaniel, Broadcasting, p.45. http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 174 CHUA AI LIN the world’.19 At the beginning of the 1930s, Singapore listeners had no daily local broadcasts, and were unable to receive any British stations, even though they could listen to the news in French, Dutch or Russian and in English from America. The most obvious communities of listeners with common interests and cultural references—Singapore itself, the Malayan peninsula, and a British imperial network—were glaringly absent. As broadcasting developed, this open global outlook was overtaken by more circumscribed identities along the lines of existing political and geographical lines, which subsequent communities of listeners mirrored. At the end of 1932 the first of these was a British imperial identity, fulfilling the raison d’être of the Empire Service, followed in 1933 by a Malaya-wide identity facilitated by the Singapore station Radio ZHI. A Singapore-specific listening community came about in 1937 with the first local medium wave broadcasts from the newly set-up British Malaya Broadcasting Corporation. With a clear intention to reach out to the vernacular masses through nonEnglish programming, Radio ZHL took on a more obvious local character, and when the British Malaya Broadcasting Corporation took its programming onto the short wave band as well, the listening community was once again extended to a Malaya-wide one. Rather than a progressive development based on distance— from local to regional to imperial to global—it was a haphazard trajectory dependent on a combination of broadcasting technology, commercial factors, and state regulation. In terms of using mass media to create imagined communities of audiences, broadcast technology reconfigured the process, making it much more diverse, unpredictable, fluid, and ultimately contingent on both the available technology and the provision of radio programmes. Technological citizens and civil society At the most active end of the spectrum of these radio communities were those who organized, promoted, and participated in the work of broadcasting itself. As with the history of motoring in Singapore, in the field of wireless radio the very earliest interest came from 19 Malayan Radio Times, 24 May 1936, front cover. http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 RADIO IN INTERWAR SINGAPORE 175 amateur enthusiasts.20 In fact, the first association in Singapore was the Singapore Radio Society, established in October 1923, a year-anda-half before the Amateur Wireless Society of Malaya began.21 The history of the Singapore Radio Society illustrates the close connection between associational life, commercial interests, and the blurring of dividing lines between the state and civil society during the mid1920s. The prime mover behind the Singapore Radio Society was Powell Robinson, who later became the Managing Director of the first local broadcasting company, the Malaya Broadcasting Company Ltd., incorporated in April 1924. The society’s meetings were held at the address of the company and prominent investors in the company spoke at the society’s meetings.22 By the time the society held a large public meeting in March 1925, it had won the support of the Governor of the Straits Settlements, Sir Laurence Guillemard, who agreed to be its patron. At this early stage, when broadcasting had not yet become part of the state’s activities, there was no conflict between the Governor’s support for the society and his official position. However, nothing more was heard of the Singapore Radio Society after March 1925. The motivation of its members was very likely to have been closely tied to the progress of the Malaya Broadcasting Company, and their energies refocused on establishing professional broadcasting. A proposal was presented to the Straits Settlements government for the introduction of receiver licence fees to fund radio stations in Singapore, Penang, and Malacca, and this was followed in 1926 by a government promise to give the Malaya Broadcasting Company a broadcasting licence. However, this never materialized, thus exposing deep divisions between the society and its official patron, the Governor.23 The company eventually fell into abeyance, and in terms of associational life, the Amateur Wireless Society of Malaya, with its amateur broadcasting efforts, had taken over the lead from the Singapore Radio Society. The Amateur Wireless Society of Malaya encountered the same issues regarding the relationship between the society, commercial interests, and the state. It changed in character from being a small 20 Automobile Association of Singapore, Motoring Beyond 100: Celebrating 100 Years of the Automobile Association of Singapore (Singapore: Automobile Association of Singapore, 2007). 21 ‘Singapore Radio Society’, Straits Times, 3 October 1923, p. 10. 22 ‘Malaya Broadcasting Company’, Straits Times, 5 April 1924, p. 8. 23 ‘Mr P. Robinson “Broadcasts”’, Straits Times, 25 November 1931, p. 2. http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 176 CHUA AI LIN group of enthusiastic amateurs dabbling in a common pastime in 1925 to a larger society which, by the time of its revival in 1931, saw lobbying the government as one of its primary functions. Unlike the Singapore Radio Society, which was intimately connected to the Malaya Broadcasting Company, the re-formed Amateur Wireless Society of Malaya initially attempted to keep commercial vested interests out of the society’s affairs by disallowing members of the wireless trade from joining the society’s committee; only when this was found to be impractical did the society alter its constitution.24 During initial discussions in 1930 on the matter of reviving a wireless society, it was decided that the Governor, Sir Cecil Clementi, and the Chairman of the Singapore Harbour Board, G. W. A. Trimmer, would be invited to be the society’s patron and president respectively.25 However, these officials never did take up a position in the society, and it would not be surprising if this was a result of the realization that it would be best to avoid a repeat of the problems caused by the Singapore Radio Society having the Governor as its patron yet finding itself at odds with the state. The potential for conflict between state and public opinion was far greater for the new Amateur Wireless Society of Malaya in 1931. Changing conditions signalled that the time was ripe for the association to become active once again. The society’s newsletter Omba Pende reported an increase in the purchase of radio equipment, greater press coverage of radio matters, and an intensification of public demands for the broadcasting of British programmes, both locally and from the metropole.26 Lobbying the state for reliable broadcasting of programmes tailored to the Malayan listeners was one of the key functions of the society. Significantly, participants in the revived Amateur Wireless Society of Malaya were a far more diverse group than the original set of European technical professionals who had formed the society’s committee in the 1920s. Nearly 100 people submitted their names to join the society prior to the inaugural meeting and ‘most of them are Europeans, Eurasians or Chinese, but others are represented—Indians, Ceylonese, Malays and Japanese’.27 The first committee comprised European names familiar in local radio: R. E. Earle, F. E. A. B. Sewell, C. H. Stanley Jones, and D. W. Mortlock, 24 ‘Wireless in Malaya’, Straits Times, 19 February 1932, p. 16. ‘Radio Society’, Straits Times, 10 November 1930, p. 12. 26 ‘Five Dollars for Nothing’, Omba Pende, July 1931, p. 1. 27 ‘First meeting of Society’, Malaya Tribune, 31 October 1930, p. 10. 25 http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 RADIO IN INTERWAR SINGAPORE 177 but it also included an equal number of non-Europeans: Eurasians, O. E. Hogan and C. P. M. Martinus; an Indian, I. M. Nagalingam; and a Chinese, Kwah Siew Tee.28 Even the venue of the society’s meetings, the café at G. H. Sweet Shop in Battery Road, was courtesy of the hospitality of the owner, J. Sarkies, an Armenian member of the society.29 Even prior to this, non-Europeans demonstrated a significant interest in radio. When the Singapore Radio Society organized the first large-scale public meeting on the subject of wireless in 1925, it was standing room only at the Singapore’s premier venue, the Victoria Theatre. ‘The audience consisted of all nationalities, Chinese ladies occupied the boxes and some of the circle seats, whilst Arabs, Indian, Malays, Chinese, Eurasians and Europeans were there in goodly number,’ reported the Malayan Saturday Post.30 At the same meeting it was announced that several prominent Chinese had pledged their support to the Malaya Broadcasting Company: Tan Kah Kee, Song Ong Siang, Lim Nee Soon, See Tiong Wah, and Li Sing Yu, who represented both the English-educated and Chinese-educated sectors of the community. Tan Kah Kee, who had founded the Nanyang ) Chinese-language newspaper two years earlier, Siang Pau ( also requested the paper’s management to help actively promote radio in Malaya.31 These individuals represented community leaders and entrepreneurs whose influence and financing would promote the wireless radio in the mid-1920s. Soon after, non-Europeans began making their mark as enthusiasts with an interest in technical practicalities of radio in their membership of the Amateur Wireless Society of Malaya. The Amateur Wireless Society of Malaya also understood the importance of increasing the size of the listening public. A critical mass of listeners was needed to strengthen the society’s appeal to the authorities responsible for the official provision of broadcasting services. The Asian presence among empire radio listeners was conveyed to the BBC and Colonial Office by the society, which asserted that ‘we Britishers and English-speaking Asiatic races in this part of the world feel keenly the absence of regular British programmes and 28 ‘Radio Society Revived’, Malaya Tribune, 10 November 1930, p. 9. ‘First Meeting of Society’; advertisement for G.H. Sweet Shop, Omba Pende, July 1931, p. 4. 30 ‘The Singapore Radio Society’, Malayan Saturday Post, 14 March 1925, p. 9. 31 Ibid. 29 http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 178 CHUA AI LIN would greatly appreciate efforts to speed up the process of bringing the life and music of Britain to our imaginary firesides’.32 In 1933, the society discussed lowering its annual fee from $12 to $2, and noted that ‘should the proposition go through the Society looks for a big increase in membership, especially amongst the Asiatic members of the community’.33 In the society’s official organ, the Malayan Radio Review and Gramophone Gazette (the successor to Omba Pende), the inaugural editorial of June 1933 opined, At the moment the bulk of radio enthusiasts come from the European community and most of these people hold executive positions. Tact and enterprise should enable each one of us to introduce the subject of radio to the senior members of our non-European staff. It will be found that their interest in radio matters is soon roused and needs but little guidance to develop a healthy movement which will benefit us all. As long as radio enjoyment is confined to Europeans and a few members of other communities, Malaya will not occupy the position in radio to which it is entitled.34 What is clear is that Singapore residents were participating in a movement concerning an area of technology in which the state had little interest at this stage, and that non-Europeans too were being drawn into a wider civil society. The role of the press was a key factor in the growing interest of Asians in wireless radio. As mentioned earlier, the Singapore Radio Society had sought the support of a major Chinese newspaper, the ). Among English-language dailies, the Nanyang Siang Pau ( Malaya Tribune was the prime mover behind the revival of the Amateur Wireless Society of Malaya in 1930. The Tribune was known as the ‘krani’s paper’ (the clerk’s paper), with a wide readership in the Asian community and a history of lobbying the government on various issues, from municipal matters to political rights for Asians. Starting out with sporadic articles in the late 1920s, the Tribune moved on to running a weekly Friday column on wireless radio. The writer of the radio articles and column was ‘Radiofan’, whose true identity was almost certainly C. H. Stanley Jones, the assistant editor of the Malaya Tribune. He became a committee member of the revived Amateur Wireless Society of Malaya and was the editor of Omba Pende which began publishing in July 32 ‘Five Dollars for Nothing’, p. 4. Malayan Radio Review and Gramophone Gazette, July 1933, p. 33. 34 ‘The Dawn’, Malayan Radio Review and Gramophone Gazette, June 1933, p. 1. 33 http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 179 RADIO IN INTERWAR SINGAPORE 1931. Omba Pende was even printed at the Malaya Tribune press.35 Soon, the other English-language newspapers in Singapore—the Singapore Free Press and the Straits Times—also began giving more coverage to wireless radio news and became firm supporters of radio. The character of associational life changed as new technologies became part of everyday life for a significant proportion of the population. They were no longer clubs where gadget-obsessed eccentrics found companionship with like-minded souls, but platforms for citizens in the wider community to make their voices heard by the colonial administration. Associations became instruments of democracy for civic interests, and were a particularly important avenue of expression under conditions that gave little room to imperial subjects to participate in politics per se. In terms of political development, the Straits Settlements ranked very low compared to other Crown colonies. Until the formation of the Straits Settlements Legislative Service in 1932, there was a ‘colour bar’ which prevented non-Europeans from being appointed to higher civil service posts. Despite reforms in the Legislative Council and Executive Council, in 1924 and 1932 respectively, to include more Asian and nongovernmental representation, the resulting changes were extremely limited: in the Legislative Council of 26 seats, there were only six non-Europeans.36 Along with Hong Kong, the Straits Settlements were the only two Crown colonies that did not have an unofficial majority in the Legislative Council. New mass technologies created spheres of activity where ordinary citizens found they could engage the state to convey their needs and opinions, and this acted as a training ground for democracy well before mass politics in the post-war era of decolonization. Widening participation: Asians, women, and youth As a sphere for civic activism wireless radio broadcasting was made even more significant by the way in which it was able to draw new publics into its fold, beyond the European men who dominated the Singapore scene. As we have seen, Asians were active promoters of 35 Malaya Tribune, 19 December 1930, p. 12; Omba Pende, July 1931, p. 1, back cover; and November 1931, p. 1. 36 C. M. Turnbull, A History of Singapore, 1819–1975 (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1977), pp. 157–58. http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 180 CHUA AI LIN radio from the earliest days and participants in public engagement with the state. They also played a part in the radio industry as technical staff and broadcasting talent. The consumer aspect of radio, which gave it a presence in homes, schools, associational clubhouses, in shops and amusement parks, brought more Asians, women, and youths into the sphere of those with an interest in wireless radio broadcasting. By dint of race, gender or age, these groups were much less visible in public life, but their role as part of radio’s listening communities gained them recognition as sections of society that had to be directly catered for. Asians were present behind the scenes from the very beginning of wireless radio in Singapore, providing technical services as well as programming content. When the Amateur Wireless Society of Malaya started experimental broadcasting in 1924, the ‘Society’s Chinese staff, Ah Swee and “Batchi”’ were acknowledged for helping to solve the technical difficulties encountered.37 Radio magazines carried advertisements for radio engineering services from Chinese shops such as Soo Ban Soon, Chung Wah Radio Service, and Kee Huat Radio Company, as well as the Indian radio engineer behind S. P. Shotam and Co.38 or the Japanese Mitsuboshi Electric Company which boasted of providing ‘repairs under the personal supervision of a diplomaed [sic] engineer of the Nagoya Wireless School’.39 Commercial directories reveal that a fair proportion of radio and gramophone shops in Singapore during the 1930s were owned or run by non-Europeans. The performing arts also gave opportunities for non-Europeans to be heard on the airwaves. Unlike the cinema, which was entirely dependent on foreign content, the simpler demands of radio programme production allowed people in Singapore to become active producers, and not simply consumers, in this new sound technology. The earliest transmissions by the Amateur Wireless Society of Malaya included performances by a Eurasian, Mr Eber, as well as an Indian, Roy Minjoot, and his band.40 In the 1930s, the amateur orchestra of the European-run Singapore Musical Society included a fair number of Asians and 37 ‘Bancam’, ‘Work of the pioneers in Malaya. I – History of the A.W.S.M.’, pp. 16–17. 38 Denyse Tessensohn, Elvis Still Lives in Katong (Singapore: Dagmar Books, 2003), p. 166. 39 Advertisement for Mitsuboshi Electric Company, Omba Pende, July 1931, p. 21. 40 ‘Bancam’, ‘Work of the pioneers in Malaya. I – History of the A.W.S.M.’, pp. 16–17. http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 RADIO IN INTERWAR SINGAPORE 181 performed regularly on Radio ZHI.41 One notable performing group, ‘believed to be the only all-Chinese choir singing in English in Asia today’, attracted many admirers among ZHI listeners across Malaya.42 Regular broadcasts from Singapore dance halls, especially those at the Worlds entertainment parks, featured professional dance bands most of which boasted Goanese or Filipino talents, such as the ‘Victor Celeste Trio’ who performed on Radio ZHL in 1938.43 During the mid-1930s the number of radio listeners suddenly increased, reflecting changes in receiver technology and creating a greater diversity of listeners. In 1934, 931 licences were issued, more than double the 353 licences issued in 1933.44 Improvements in receiver technology resulted in off-the-shelf units that could receive a clear signal without requiring much technical skill or knowledge to operate and so encouraged the average person to become a regular listener. A sign of the changing manner of radio listening was the disappearance of technical articles from radio magazines of the mid1930s, which were replaced by reports on programming content. Two fortnightly periodicals in Singapore also pointed to important shifts. While earlier radio magazines functioned as the official organ of the Amateur Wireless Society of Malaya, the Malayan Radio Times (1935) and the Radio Magazine of Malaya (1936) were commercial publications aimed at a mass readership. The latter was produced by the Radio Service Company of Malaya, the owners of Radio ZHI. With its radio supplies retail shops in Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Penang, Seremban, Malacca, and Ipoh, the Radio ZHI station in Singapore, and now the Radio Magazine of Malaya, the company had a comprehensive marketing strategy, and its high profile also helped to boost public awareness of radio in Malaya.45 Broadcasting content had to take into account the diverse backgrounds and specific interests of the expanded range of radio listeners. From 1935, Radio ZHI included regular Chinese, Indian, and Malay music in its broadcasts,46 and from the inception of Radio ZHL by the British Malaya Broadcasting Corporation in 1937, it had 41 Paul Abisheganaden, Notes Across the Years: Anecdotes from a Musical Life (Singapore: Unipress, 2005), pp. 56–58. 42 ‘Unique Chinese Choir’, Straits Times, 19 November 1933, p. 10. 43 Abisheganaden, Notes Across the Years, pp. 8–9, 74; Malayan Radio Times, 11 September 1938, p. 32. 44 McDaniel, Broadcasting, p. 42. 45 Radio Magazine of Malaya, 1 February 1936, p. 2. 46 McDaniel, Broadcasting, p. 37; Malayan Radio Times, 16 February 1936, pp. 30–40. http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 182 CHUA AI LIN about two hours’ worth of non-English programming each day, mostly in the form of Malay and Chinese music gramophone recordings and children’s shows in Cantonese and Mandarin. In order to put on these programmes, non-European staff must have been employed by Radio ZHI and ZHL as early as 1935. At the very end of the interwar period, the Malayan Broadcasting Corporation introduced a major change in Singapore broadcasting in the scale of its vernacular content, and trained Asians in a full-range of broadcasting-related jobs.47 According to Malayan Broadcasting Corporation producer, Giles Playfair, who was brought in from London, during the short time that the corporation was operational, it ‘recruited and trained locally a staff of 290 individuals, mostly Asiatics’.48 These included lowend support staff such as drivers and messengers, control engineers who managed operations in all the studios, as well as announcers and producers for the vernacular-language services. There were numerous female employees working in supporting positions as secretaries and ‘switchboard telephonists’—mostly Eurasians and some Chinese, as well as high-profile announcers, such as Zamroude Za’ba and Barbara Lee.49 The fact that many of the local staff returned to work in Radio Malaya after the Japanese Occupation, indicates the fundamental role of the Malayan Broadcasting Corporation in creating a localized broadcasting industry staffed by non-Europeans. As broadcasting in Singapore became more sophisticated, programmes were offered that specifically catered to women and children, following the pattern in Britain where the BBC had separate advisory committees for women’s and children’s programmes. In June 1932 the Malayan Radio Review commented that ‘most radio enthusiasts get a pretty tough time from their wives, wireless widows they call themselves’, and yet one year later, when the magazine was relaunched as the Malayan Radio Review and Gramophone Gazette—with twice as many pages, more advertising, and at half the price—signs of the female reader-listener were clearly evident. A ‘Women’s Page’ was introduced and there were advertisements targeted at women, such as one for Elizabeth Arden beauty treatments. Radio ZHL appealed to the female listener with its weekly 15-minute ‘Talks for Women’ 47 For a detailed personal account of work of the Malayan Broadcasting Corporation from December 1941 to February 1942, see Giles Playfair, Singapore Goes Off the Air (London: Jarrolds Publishers, 1944). 48 Ibid, p. 143. 49 Ibid, pp. 55, 69, 98, 123; Barbara Lee, oral history interview, Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore, reel 1. http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 RADIO IN INTERWAR SINGAPORE 183 at 7.30 pm on Thursdays; and wartime propaganda from the Malayan Broadcasting Corporation in 1940 included a play about Florence Nightingale ‘designed to rouse the courage of the women of Malaya’.50 According to an editorial in the Malayan Radio Review and Gramophone Gazette’s ‘Women’s Page’, women listeners were a more serious radio audience than men: A woman’s interest in wireless is pre-eminently that of a listener. She wants a good programme which will interest and amuse her and she is more exacting and discriminating in her demands than the average man. His interest, if he is an enthusiast, is more mechanical; he likes tuning in and getting obscure and varied stations and seems more concerned with the quality of reproduction, volume of tone and clarity than with the subject of the broadcast. . . But the man who is not an enthusiast takes less interest in wireless than the average woman.51 This analysis implied that women’s cultural interests led to a deeper engagement with the transformative potential of modern mass media than did men’s fascination with the mechanics of technology. The different approaches of men and women to radio were echoed in other forms of new mass media. The cinema was widely seen as attracting a large female audience, who in turn were more obviously influenced by what they saw on screen than were men. In comparison with the cinema, radio had the potential to have an even greater impact on women than men because it could be enjoyed within the confines of the home, thus reaching out to many housewives. As the ‘Women’s Page’ put it, ‘she has more time to listen in than her menfolk, for where her work lies in the home, she can listen while she is doing her daily jobs’.52 With the increasing technical simplicity and general popularity of radio, listening to the wireless became one of the hobbies encouraged in young people. In 1934, The Monitor, a ‘weekly newspaper for young people of Malaya’, began a radio section focusing primarily on addressing technical problems. By 1936, Radio ZHL was broadcasting a short ‘Children’s Programme’ on four days of the week in English, Cantonese, and Mandarin. Learning to build rudimentary crystal receiver sets was also a good science lesson for students, and, with the introduction of medium wave broadcasts in Singapore in 1937, there were even programmes on frequencies that crystal sets were 51 Playfair, Singapore, p. 58. ‘Women’s Page’, Malayan Radio Review and Gramophone Gazette, June 1933, p. 25. 52 Ibid. 51 http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 184 CHUA AI LIN capable of receiving. The educational potential of radio was most evident in the learning of the English language, which was one of the aims of the BBC. In 1926, the Advisory Committee on Spoken English was formed to decide on the usage and pronunciation of both English and foreign words. Even in Britain itself concerted effort was required in the endeavour to standardize spoken English; radio and recorded speech became particularly important tools in the pursuit of the same goals in the colonies where English was learned as a foreign language.53 Many Anglophone Asians who read the English daily newspapers or did clerical work in European merchant houses or government offices did not come from English-speaking homes themselves. Their fluency was acquired through a primary and secondary education in English-medium schools. English textbooks could be supplemented by recorded sound to improve spoken English, in programmes such as the Radio ZHL ‘Children’s Programme’, as well as those in ‘Received Pronunciation’ broadcast on the Empire Service. The latter also functioned as a counter to the spread of American slang and pronunciation through Hollywood movies, which was critically noted by several contemporary observers. The urban soundscape Radio also made its presence felt in the daily life of Singapore’s streets and contributed to the identity of Singapore as a modern city. The growing presence of radio was important in expanding the listening communities that this paper has focused on. During the early years of the twentieth century there was a general ‘aural awakening’ because of the existence of more sound, as well as a greater variety of sound, as the media studies scholar, Biocca, has noted.54 Beside the explosion of music in society, with the advent of electrically amplified sounds from radios and gramophones, the increased aural stimulation of the modern city arose from the sounds of urban congestion, mechanization, and machines.55 Observers’ descriptions of Singapore in the interwar period also began to pay attention to 53 Robert McCrum, Robert MacNeil and William Cran, The Story of English, 3rd edition (London: Faber & Faber and BBC Books, 2002), pp. 16–19. 54 Frank Biocca, ‘Media and Perceptual Shifts: Early Radio and the Clash of Musical Cultures’, Journal of Popular Culture, 24 (2), 1990, pp. 1–15. 55 See the discussion of noise in Emily Thompson, The Soundscape of Modernity: Architectural Acoustics and the Culture of Listening in America, 1900–1933 (Cambridge, http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 RADIO IN INTERWAR SINGAPORE 185 these distinctly modern soundscapes of the city. The rapidly growing motor vehicle population on the island resulted not only in traffic congestion, but also in ‘brakes grinding harshly and horns making incessant pandemonium’.56 Recorded music and radio broadcasts became common sounds on Singapore’s streets during the 1930s. In public spaces they could be enjoyed for free as they filled shops in the city centre and spilled out onto the adjacent streets. Stores selling radio and gramophone equipment, records, sheet music, and merchandise related to popular music had a direct commercial interest in playing gramophone music or turning on the radio to attract potential customers. Advertisements for the Radio Service Company read: ‘Open every evening up to 10 o’clock/Come in and hear what’s on the air’.57 Even shops and businesses unconnected to the radio trade installed wireless sets to attract customers. Prior to the Second World War, there were about 30 barber shops in the South Bridge Road area, with eight of them on Smith Street alone. Two or three of the Smith Street barbers aimed to outdo their competitors by placing radio-sets at their front entrances.58 A similar strategy was used at the Worlds entertainment parks, where, for example, in January 1931, The New World News advertised a new amusement feature: wireless radio broadcasts nightly from 7 pm to 10 pm with ‘Music! Songs! Speeches!’ from ‘Saigon, Bandoeng, Manila, Soerabaya and Singapore’s Amateur Station, California (if on) on an All British built Set’.59 Another way of enjoying what was on the airwaves would have been to pay a visit to a neighbour’s home to listen to their set. Particularly in rural areas, kampong-dwellers would have crowded round the sole radio in the village, and radio listening took the form of a communal activity. Organized sound pervaded not just the spaces of the city, but also its horological cycles. Broadcasts could be tuned into at all hours of the night from the other side of the globe, and those who owned a radio or gramophone were no longer tied to the opening hours of public venues to enjoy music or catch up on international news. This Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2002), Chapter 4 ‘Noise and Modern Culture, 1900– 1933’. 56 ‘Spark-Plug’, ‘Motoring in Malaya: The Craze for Power and Speed’, The Christmas Herald of Malaya, 1929, p. 32. 57 Omba Pende, August 1931, p. 17. 58 Tang She Choon, oral history interview, Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore, reel 7. 59 The New World News, 31 January 1931, p. 14. http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 186 CHUA AI LIN provoked a public debate on the ‘noise’ in urban centres like Penang and Singapore: ‘In our Singapore suburbs, with their open houses and different nationalities, the gramophone, especially the electrical type, can be a very real nuisance.’ This was particularly said to be the case for Muslims whose prayer times were thereby disrupted.60 Eventually, the problem had to be dealt with by law, and in 1934 the Minor Offences Ordinance, in relation to ‘post-midnight noises in the Colony’, was amended to prohibit the playing of gramophone and radio music after midnight except with the written permission of the police, in addition to the original categories of ‘any drum or tom-tom, or blows [of] any horn or trumpet, or beats or sounds [of] any brass or other metal instrument or utensil’.61 This new legislation was part of a long history of attempts by colonial authorities to maintain order in the urban environment. For example, large Chinese religious festivals, such as the Chingay procession, were restricted by the 1867 Peace Preservation Act, an ordinance primarily concerned with controlling rioting, but which also effectively contained loud and colourful social events.62 The mystique of wireless radio Juxtaposed with the development of radio as an increasingly commonplace and quotidian phenomenon was the impression of wireless broadcasting as something intangible and mysterious. But, instead of being at odds with its increasingly everyday existence, the novelty of wireless radio transmissions was an important factor in capturing the attention and imagination of the masses. Of all the new communications technologies of this period, radio was perhaps the most conceptually astounding for the average person. Radio transmissions crossed immense distances without any lag in time and with no visible means of transmission. For many people, it seemed almost mystical. ‘Through the medium of the ether the radio enthusiast ranges far over continents and oceans, and is in touch 60 Bumiputera, 14 July 1934, quoted in Tan Sooi Beng, ‘The 78 rpm Record Industry in Malaya Prior to World War II’, Asian Music, 28 (1), 1996–97, p. 14. 61 Ibid, pp. 14–15. 62 Song Ong Siang, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore (1923; reprinted Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984), pp. 146–47; Victor Purcell, The Chinese in Malaya (1948; reprinted Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1975), p. 125; Edwin Lee, The British as Rulers: Governing Multiracial Singapore, 1867–1914 (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1991), pp. 57–60. http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 RADIO IN INTERWAR SINGAPORE 187 with one of the greatest and most mysterious phenomena revealed by science,’ wrote A. W. Jansen in the school magazine of St. Joseph’s Institution.63 Jansen continued, Many a time could I be seen sitting in front of my receiver with headphones firmly clapped on to my ears, my inscrutable eyes resting impassively on the tuning dial like those of an ancient Egyptian priest meditating before the shrine of Osiris.64 Radio and psychic powers were forms of communication where the means and method of contact was intangible and inexplicable to most. Both provided privileged access to certain kinds of information and required the intermediary of a wireless set—or medium. An advertisement for RCA Victor radio receivers expressed this technosupernatural relationship by describing the radio as a ‘Magic Brain’ with ‘Magic Eye’, words which invoked mystical powers.65 There seems to have been a general attraction to the fantastical during this era, whether in the form of modern science or the supernatural. Recent historical studies have begun to emphasize the ‘enchantment’ of modernity, in contrast to the long-standing view that the science, secularism, bureaucracy, and rationalism of the modern age stamped out spirituality and a belief in ‘wonders and marvels’. Modern enchantments appeared in Europe and America in the form of fin-de-siècle German occultism, the freak shows of P. T. Barnum, and the illusionist performances of magician, Jean-Robert Houdin, among others. Each of these examples also established a close link between modern marvels, popular culture, mass media, and consumerism.66 The same phenomenon has been observed in the Dutch East Indies by Rudolf Mrázek, who sees parallels between the practice of the occult and that of radio. The Indisch Spiritisch Tijdschrift (Indies Spiritist Journal) was as popular as the Orgaan van de Ned. Ind. Radio Amateurs 63 A. W. Jansen, ‘Radio as a Hobby’, St. Joseph’s Magazine, 1931–32, p. 40. Jansen was probably an old boy of the school, as the magazine included writings from students and teachers as well as the school’s alumni. 64 Ibid. 65 Malayan Radio Times, 7 June 1936, inside front cover. 66 Michael Saler, ‘Modernity and Enchantment: A Historiographic Review’, American Historical Review, 111 (3), 2006, <http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/ ahr/111.3/saler.html>, [accessed 8 October 2011]. Among the works discussed by Saler are Corinna Treitel, A Science for the Soul: Occultism and the Genesis of the German Modern (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004); James W. Cook, The Arts of Deception: Playing with Fraud in the Age of Barnum (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2001); Simon During, Modern Enchantments: The Cultural Power of Secular Magic (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2002). http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 188 CHUA AI LIN Vereeniging (Journal of the Association of Netherlands Indies Radio Amateurs), which sold at least 5,000 copies monthly.67 In Singapore, Sripaty’s Magazine, ‘A Monthly Devoted to Astral Mental and Occult Sciences’, first published in 1908, was revived in 1925 and was still going strong in the early 1930s. Another Indian-run periodical from Singapore, The Orient Gong, contained a substantial number of advertisements and articles on spiritualism, such as ‘Occult Ethnology’ and ‘What is Radiant Energy?’.68 For the urban public in Singapore it seemed that an eclectic combination of esoteric spiritualism from around the world came together in their city, easily incorporating a vocabulary of scientific rationalism and academic qualifications. Within the city, the mystical also sat comfortably in the heart of the fashionable downtown, in Capitol Building itself, which was the home of the premier luxury cinema. As advertised in the Singapore-based Hollywood News Magazine, here was to be found ‘Guru Max’, representative of the ‘The Ancient and Mystical Brotherhood of Applied-Psychologists of the “Yoga Method”’, who offered to teach ‘this uncanny and super-natural OCCULT SCIENCE!’ such that one could ‘Know the Manifestations of The Great BEJONG! Live again in a New Spirit! Conquer The Word “FEAR”! Have a MASTER MIND & A DOMINATION WILL! BE A MASTER OF MEN.’69 With the technological and supernatural combined, it was a short step to science fiction in the popular imagination. The link to radio was most directly expressed in the cover design of the Amateur Wireless Society of Malaya’s official organ from 1933, the Malayan Radio Review and Gramophone Gazette (see Figure 1). It illustrated sound waves travelling upwards from a man at a radio console towards a picture of the entire globe at the top of the page, with the world map centred on Asia and the Malayan peninsula. Scenes from around the world were depicted, from American-style skyscrapers, to snow-capped mountains to minarets and Islamic domes, to Chinese roofs and palm trees. In the same vein, the word ‘universal’ was a popular choice at the time for Singapore businesses, particularly those associated with new technologies and modern industries, for example, Universal Cars Ltd.; Universal Motor and Accessory Co.; the Singapore branch 67 Rudolf Mrázek, Engineers of Happy Land: Technology and Nationalism in a Colony (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), pp. 172–73. 68 The Orient Gong, August 1936, pp. 464–66, 490–91. 69 Hollywood News Magazine, 1 May 1935. http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 189 RADIO IN INTERWAR SINGAPORE Figure 1. Cover of the Malayan Radio Review and Gramophone Gazette, July 1933. Source: British Library. of the Hollywood firm, Universal Pictures; and The Universal Trade Co.70 70 Singapore and Malayan Directory, 1936, sub voce ‘Universal Cars Ltd.’, ‘Universal Motor & Accessory Co.’, ‘Universal Pictures’, ‘The Universal Trade Co.’. http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 190 CHUA AI LIN Conclusion The modern technology of wireless radio paved the way for many changes in colonial society in Singapore. At the broadest level, wireless radio created various levels of communities of listeners, drawing in a wide range of social groups. In so doing, radio empowered more sectors of society—non-Europeans, women, and young people—in a pattern parallel to the growing spread of education. It did so not only in direct ways through information dissemination, but also more indirectly by opening up imaginative possibilities through access to broadcasting from around the world. The relationship of Singapore residents to wireless radio was more than a practical one of technological skill: it was also about cultural exposure and cognitive shifts in understanding the world in terms of time, space, science, and magic. Even the fundamental auditory, lived experience of the city was deeply altered by the allure of broadcasting combined with the phenomenon of electrically amplified sound. One key facet of this history of wireless radio in Singapore before the Second World War is the passive role of the colonial state until a very late stage. It loomed large only as a major obstacle to the development of radio, especially through failing to develop and execute an official policy for regulating the broadcasting industry. Instead, the impetus for taking up this new technology and seeing the revolutionary imaginative possibilities it offered came from members of the public— amateur enthusiasts as well as entrepreneurs, supported by the press. The field of wireless radio provided an important space for the flourishing of civil society, functioning independently of the state, as well a site from which to agitate for the authorities to play a larger role in expanding broadcasting. This helps us to understand important factors beyond the state and to locate agency in colonial society more precisely. We need no longer be blinded by a narrow focus on the slow pace of constitutional development in the Straits Settlements when it comes to tracing the roots of democratic participation, and we can begin to locate those roots in the interwar era, well before the independence movement of the 1950s. The sphere of radio also illustrated the opportunities for multiracial interaction in colonial society. It was a combination of European expertise and Chinese financing that lay behind the first broadcasting venture, the Malaya Broadcasting Company in 1924. Subsequent radio organizations all included non-European participants and had to make active provision for the Asian listeners who formed the bulk http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69 RADIO IN INTERWAR SINGAPORE 191 of the population. More than a simple classification of European and Asian, the sources show the immense diversity of the Asian ethnic communities involved. The Chinese were the dominant ethnic group in Singapore and were prominent as businessmen as well as in technical services, but they were by no means the only Asian group present in the history of Singapore radio. The full cosmopolitan range of Singapore society was represented, and the lingua franca of English was where the interaction and engagement was concentrated. That cosmopolitanism was reflected in the truly international scope of short wave radio. This challenged the dominance of British cultural influence in its colonies, just as the popularity of Hollywood films introduced widespread American influence across the British empire during the same era. Although British programming became a staple on the Singapore airwaves after the establishment of the BBC’s Empire Service, there were many other reliable stations from around the world that Singapore listeners were familiar with and whose schedules were reported in the daily newspapers and the radio magazines. The cultural landscape of the city was deeply and diversely cosmopolitan, with the international scope of wireless radio being a modern, mass-mediated extension of the mix of ethnicities, cultures, languages, and religions that made up Singapore. The island had always been a regional and global trading emporium in which diverse peoples, ideas, and commodities were to be found, and even under British rule, a much more international range of extra-British influences existed. Hence, even though Singapore had a clear identity as a British colony, it is important not to overstate the ‘Britishness’ of the place and to recognize the full range of its external influences. http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 12 Jan 2014 IP address: 137.132.123.69