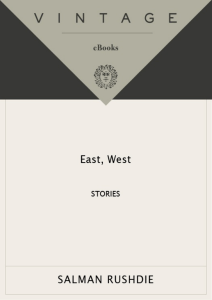

WRITERS AND THEIR WORK I SOBEL A RMSTRONG General Editor SALMAN RUSHDIE SALMAN RUSHDIE Damian Grant Second Edition # Copyright 1999 & 2012 by Damian Grant First published in 1999 by Northcote House Publishers Ltd, Horndon, Tavistock, Devon, PL19 9NQ, United Kingdom. Tel: +44 (0) 1822 810066 Fax: +44 (0) 1822 810034. Reprinted 2007 Second edition 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or stored in an information retrieval system (other than short extracts for the purposes of review) without the express permission of the Publishers given in writing. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-0-7463-1162-2 Typeset by PDQ Typesetting, Newcastle-under-Lyme Printed and bound in the United Kingdom For Fiona, Fergus, and Marcus; and, this time, for Madeleine Contents Acknowledgements viii Biographical Outline ix Abbreviations xi 1 Introduction 1 2 Grimus 27 3 Midnight’s Children 38 4 Shame 57 5 The Satanic Verses 71 6 Haroun and the Sea of Stories and East, West 94 7 The Moor’s Last Sigh 107 8 Interchapter 123 9 The Ground Beneath Her Feet 126 10 Three Novels for the New Millennium 147 11 Conclusion 175 Notes 185 Select Bibliography 202 Index 214 vii Acknowledgements I am grateful to the University of Manchester for the grant of sabbatical leave during 1997. Also to the universities of Burgundy and Lille, York, and again Manchester, for invitations to conferences at which some of the material included here was proposed and discussed. I would also like to express my thanks for the conversation and encouragement of Madeleine Descargues. She knows what we both owe to Sterne and Rushdie; resembling Padma in nothing else, she has talked this project forwards. viii Biographical Outline 1947 1954 1961 1964 1965 1968 1969 1970 1974 1975 1976 1979 1981 1983 1984 1986 Salman Rushdie born in Bombay, the only son of Anis Ahmed Rushdie, a businessman who had received his education in Cambridge, and his wife, Negin. There are three sisters in the family. Rushdie attends an English Mission school in Bombay. Rushdie sent to England for his secondary education, at Rugby School. The family moves to Pakistan: Karachi. Goes to Cambridge (King’s College) to read history. No longer a believer, develops a historical interest in Islam. Becomes involved in acting with the Cambridge Footlights, and addicted to the cinema. Returns to Pakistan; works briefly in television before returning to London, where he joins a company of actors. Works as a copywriter for advertising agencies, taking time out to write a first (unpublished) novel on Indian themes. Meets Clarissa Luard. Five-month trip to India and Pakistan. February: first published novel Grimus. Political involvement with black and Asian groups in London. April: Marries Clarissa Luard. June: son Zafar born. Gives up copywriting job to write fiction full-time. February: Midnight’s Children published to critical acclaim. October: wins the Booker Prize. September: third novel Shame published. Begins work on what was to become The Satanic Verses. Travels to Australia with the writer Bruce Chatwin. Meets Robyn Davidson. Travels to Nicaragua at the invitation of the Sandinista ix BIOGRAPHICAL OUTLINE 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 Association of Cultural Workers. Meets the American novelist Marianne Wiggins. January: The Jaguar Smile: A Nicaraguan Journey published. Divorced from his first wife. Marries Marianne Wiggins. September: The Satanic Verses published. The novel is denounced in India and Pakistan, and burnt in the street in Bradford. 14 February: announcement of the fatwa against Rushdie by the Ayatollah Homeini, and offer of a reward by the State of Iran for his murder. Rushdie goes into hiding, under the protection of the British Government with Special Branch police bodyguards. The ‘Rushdie Affair’ attracts international attention, stimulating anti-Islamic feeling in the west. Formation of Rushdie support groups in England, France, and elsewhere. The British Government makes representations to Iran without success. Separation from Marianne Wiggins. Publication of several books on the Rushdie Affair. September: Haroun and the Sea of Stories published. March: Imaginary Homelands: Essays 1981–1991 published; includes a last section devoted to essays and addresses which provide Rushdie’s own perspective on his situation. March: The Wizard of Oz published by the British Film Institute. October: collection of stories East, West published. September: The Moor’s Last Sigh published. Writes introduction to Burning Your Boats, the collected short stories of his friend Angela Carter, who had died in 1992. Publication of anthology The Vintage Book of Indian Writing 1947–97, edited with Elizabeth West. Marries Elizabeth West. July: second son Milan born. September: writes controversial article in The New Yorker on the death of Princess Diana in a car accident, linking this event with David Cronenberg’s film of J. G. Ballard’s novel Crash. February: on the ninth anniversary of the fatwa, which is reasserted in Iran, Rushdie meets Tony Blair to discuss diplomatic moves. Speaking on BBC television, declares his belief in the absolute right of free speech. September: the Iranian Government officially distances itself from the fatwa. Rushdie says: ‘It looks like it ’s over. It means everything. It means freedom.’ x BIOGRAPHICAL OUTLINE 1999 2000 2001 2003 2004 2005 2007 2008 2010 2011 Publication of The Ground Beneath Her Feet. Meets Padma Lakshmi, at the launch party for Talk magazine in New York. (April) Travels with his son Zafar to India. Moves to New York, expressing his frustration with literary London. Publication of Fury, weeks before the September 11 attacks on the Twin Towers. Publication of Step Across This Line, essays and other pieces from the previous ten years, including many from the New York Times and the New Yorker. Divorces Elizabeth West; marries Padma Lakshmi. Publication of Shalimar the Clown. (June) Rushdie is offered and ’humbly accepts’ a knighthood ’for services to literature.’ Divorce from Padma Lakshmi (July). Takes up a five-year appointment at Emory University, Atlanta, which had bought his archive in 2006. Publication of The Enchantress of Florence. Wins an injunction against one of his former bodyguards, who was publishing a tendentious account of his ’lost years’ in a tabloid newspaper. Midnight’s Children is selected as the best Booker prizewinner over forty years, repeating the selection in 1993 for the Booker’s 25th anniversary. Publication of Luka and the Fire of Life, written for his second son Milan. Rushdie reveals that he is writing a memoir of his ten ‘lost years’. Collaboration with director Deepa Mehta on a film of Midnight’s Children, to be called Winds of Change. (May) After the death of Osama bin Laden, Rushdie writes an article suggesting that it is time for Pakistan to be declared ’a terrorist state’ and ’excluded from the comity of nations’. (June) Announces he is to write a TV series, to be called The Next People, which will ’deal with the fast pace of change in modern life’. Thus: ’for the first time in my writing life, I don’t have a novel on the go, but I have a movie and a memoir and a TV series’. xi Abbreviations EF EW F. G. GBF HSS IH JS LFL MC MLS S. SAL SC SV WO The Enchantress of Florence (London: Jonathan Cape, 2008) East, West (London: Jonathan Cape, 1994) Fury (London: Jonathan Cape, 2001) Grimus (London: Paladin, 1989) The Ground Beneath Her Feet (London: Jonathan Cape, 1999) Haroun and the Sea of Stories (London: Granta Books/ Penguin, 1990) Imaginary Homelands: Essays and Criticism 1981–1991 (London: Granta Books, 1991) The Jaguar Smile: A Nicaraguan Journey (London: Picador, 1987) Luka and the Fire of Life (London: Jonathan Cape, 2010) Midnight’s Children (London: Jonathan Cape, 1981) The Moor’s Last Sigh (London: Jonathan Cape, 1995) Shame (London: Picador, 1984) Step Across This Line: Collected Non-Fiction 1992-2002 (London: Vintage, 2003) Shalimar the Clown (London: Jonathan Cape, 2003) The Satanic Verses (London: Viking, 1988) The Wizard of Oz (London: BFI, 1992) xii . . . some incredibly important things were being fought for here: being important to me, the art of the novel; beyond that, the freedom of the imagination, the great overwhelming, overarching issue of the freedom of speech and the right of human beings to walk down the streets of their own country without fear. Salman Rushdie, Guardian, 26 September 1998 xiii 1 Introduction IMAGINATION AND THE NOVEL Near the beginning of the nineteenth century, at a time not unlike our own of international tension and political uncertainty that entailed threats to personal liberty and freedom of thought, and when he himself had been victimized for atheism, the poet Shelley wrote a Defence of Poetry, which has become celebrated for its definition of the role of the imagination in the discovery and direction of our lives. Laws and conventions deriving from ‘ethical science’ may be necessary, he concedes, for the conduct of ‘civil and domestic life’, but it is the imagination that unlocks our full humanity. ‘A man, to be greatly good, must imagine intensely and comprehensively’, divining a more profound morality beyond the scope of rational requirement. ‘The great instrument of moral good is the imagination; and poetry administers to the effect by acting upon the cause.’1 And at the end of the twentieth century, many wars, revolutions, and anathemas later, we are if anything even more aware that the active exercise of the imagination is indispensable to the realization, establishment, and defence of those values which define us and according to which we try to live our lives. In what amounts to a near paraphrase of Shelley, the subject of this study, Salman Rushdie, insists that the imagination, ‘the process by which we make pictures of the world . . . is one of the keys to our humanity’ (IH 143). It is also true that the appeal to the imagination, then as now, invites rather than evades argument. In that extraordinarily modern document from the early eighteenth century, A Tale of a Tub, Swift identified the imagination as that which gives access to the whole spectrum of human potential, leading us ‘into both 1 SALMAN RUSHDIE extreams of High and Low, of Good and Evil‘. As if to prove Swift’s point, what Dr Johnson reproves as a ‘licentious and vagrant faculty’ is later enshrined as a principle of perception and expression by the romantics: Coleridge’s ‘shaping spirit of Imagination’.2 But, from the start, apologists for the novel had invested less heavily in the imagination, relying more on observation and documentation – though Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, with its focus on ‘what passes in a man’s own mind’, provides an important qualifying instance. Emile Zola specifically ejected the imagination from his theory of the novel, arguing that a properly scientific method had no use for it.3 In the present century, all the claims and counter-claims for and against the role of the imagination in fiction have become simultaneously available, from Henry James’s sacramental views in The Art of the Novel (1934) through the liberties of the sciencefiction writer, fantasist, or ‘magic realist’, to Samuel Beckett’s paradoxical vision of the cessation of all mental activity in Imagination Dead Imagine (1965). And those writers sometimes described as ‘from elsewhere’, typically those with a postcolonial background, have a specially difficult negotiation to make in this respect. One thinks of the strenuous theorizing of the Guyanian writer Wilson Harris, who has argued that ‘a philosophy of history may well lie buried in the arts of the imagination’, and believes that the dynamism of cultural admixture ‘lies in the evolutionary thrust it restores to the orders of the imagination’. Harris has both sponsored (in his essays) and exemplified (in his novels) that ‘counter-culture of the imagination’ which he sees as the most positive and creative response to the colonial experience, in what is to be understood as a ‘quest for new values’.4 And it is here, in this contested space, that we must locate the work of Salman Rushdie. Rushdie’s own formulations of his project most often involve reference to the imagination as the agent of synthesis or transformation. It is the imagination that liberates us from the crude ‘facts’ of history (other people’s history), and that may even absolve us from the unredeemed diary of our own lives. It will be worthwhile, therefore, to consider what Rushdie has to say in his essays about the presiding power of the imagination, and then to see how this might help us in our approach to the novels. One of the things that we learn from these essays is that 2 INTRODUCTION for Rushdie, as a postmodern writer, there is no such thing as an unqualified fact, nor an absolute fiction; the two categories necessarily overlap and leak into each other. He quotes an apposite observation from Graham Greene in this respect: novelists and journalists are antagonistic, today, because ‘novelists are trying to write the truth and journalists are trying to write fiction’ (IH 217). Rushdie sees Julian Barnes’s History of the 1 World in 10 2 Chapters as ‘the novel as footnote to history’, ‘not a history but a fiction about what history might be’ (IH 241). Calvino’s Sister Theodora (in The Non-Existent Knight) writes her chivalric story from the protected ignorance of her convent, ‘inventing the unknown, making it seem truer than the truth’, while the Marquez whom Rushdie refers to as ‘Angel Gabriel’ has the ability, through the extraordinary power of his imagination, to ‘make the real world behave in precisely the improbably hyperbolic fashion of a Marquez story’ (IH 257, 300). Pynchon’s novels represent for Rushdie ‘a rich metaphorical framework in which two opposed groups of ideas [pessimistic entropy and optimistic paranoia] struggle for textual and global supremacy’, and this novelist has the capacity to let these differently sponsored worlds inform each other; ‘his awareness of genuinely suppressed histories . . . always informed his treatment of even his most lunatic fictional conspiracies’ (IH 269). The novelist’s mistrust of history is pervasive; but it is not only novelists who can challenge official versions of the truth. ‘In the aftermath of the Kennedy assassination,’ suggests Rushdie in the essay just quoted (on Eco), ‘the notion that ‘‘visible’’ history was a fiction created by the powerful, and that . . . ‘‘invisible’’ or subterranean histories contained the ‘‘real’’ truths of the age, had become fairly generally plausible’. But the novelist is the one explicitly dedicated to that form which ‘allows the miraculous and the mundane to co-exist at the same level’, in which ‘notions of the sacred and the profane’ can be simultaneously explored (IH 376, 417). And this is the basis of his own defence of The Satanic Verses: I genuinely believed that my overt use of fabulation would make it clear to any reader that I was not attempting to falsify history, but to allow fiction to take off from history . . . the use of fiction was a way of creating the sort of distance from actuality that I felt would prevent offence from being taken. (IH 409) 3 SALMAN RUSHDIE Rushdie tersely adds here: ‘I was wrong.’ But whatever the risks involved in attempting a synthesis of fact and fiction, the separation of the two offers an even bleaker prospect. Facts by themselves will get the writer nowhere: ‘where the strength for fiction fails the writer, what remains is autobiography.’ The trouble with another writer’s work, Rushdie protests, is that he ‘will not let it take off . . . he scarcely ever lets the fiction rip’; and ‘the distrust of the narrative . . .undermines all the intelligence, all the image-making, all the evocative anecdotes’ (IH 150, 290). By the corresponding argument, fiction by itself – without the ballast of real history, the gravitas of real experience – will tend to float off into triviality. ‘There is a difference between invention and imagination,’ he maintains in another context; the first provides (even in a war reporter) ‘make-believe’, where the second will offer ‘reliable accounts of the horrific, metamorphosed reality of our age’ (IH 204). One thinks of the criticism of surrealism made by Wallace Stevens, that it ‘invents without discovering’5 – playing unserious games, conducting hypotheses with no control and therefore ultimately no interest. It is the imagination that negotiates between the two categories, and Rushdie’s cumulative account of the role and function of the imagination – in writers and film-makers alike – is almost always positive. The real frontiers of fiction ‘are neither political nor linguistic but imaginative’ (IH 69): the imagination knows how to transcend boundaries, in the way Wilson Harris argues it must if the new voices in the new literatures are to be heard in the world. It is only through an exercise of imagination that we can take part in the project of what is now a global culture, write the ‘books that draw new and better maps of reality, and make new languages with which we can understand the world’ (IH 100). The recurrent metaphor of the map reminds us just how territorial the imagination may be. In an important essay from 1985 entitled ‘The Location of Brazil’ (IH 118–25), on Terry Gilliam’s futuristic film, Rushdie explains: ‘It is not easy . . . to be precise about the location of the world of the imagination. . . . But if I believe (as I do) that the imagined world is, must be, connected to the observable one, then I should be able, should I not, to locate it; to say how you get from here to there.’ The problem is, ‘the more highly imagined a piece of work, the more ticklish the problem of location becomes’. Where is Oz, 4 INTRODUCTION where is Wonderland? Where is Apocalypse Now set? Where, for that matter, should we locate Swift’s Lilliput, or Samuel Butler’s Erewhon: where are all those ‘secondary worlds’, as Tolkien called the fictional creations of the artist.6 The spatial metaphor will obtain only so far; then there is a collision, a war between these worlds that will gravitate towards each other. Gilliam’s film tells us ‘something very strange about the world of the imagination – that it is in fact at war with the ‘‘real’’ world, the world in which things inevitably get worse and in which centres cannot hold’. And this war is what literature is really about; whether in terms of the real wars of War and Peace and The Red Badge of Courage or the metaphorical wars of Milton and Blake: the war and peace in heaven and hell. Elsewhere, Rushdie quotes Richard Wright as saying that ‘black and white Americans were engaged in a war over the nature of reality’ (IH 13), and this is the war he sees himself as fighting in this essay. The compulsion of the artist tells him: ‘Play. Invent the world.’ But the ‘play’ is serious: ‘the power of the playful imagination . . . to change forever our perception of how things are’ has been demonstrated, he argues, by Tristram Shandy as well as by Monty Python. (It is an exemplary case that the novelist Sterne contended with the philosopher Locke precisely over the nature of the imagination, and the capacity of language to represent its processes.) For Rushdie, the modern world is ‘as much the creation of Kafka . . . as it is of Freud, Marx, or Einstein’. And it is at this point in his essay that Rushdie links the idea of change to that of the new ‘migrant sensibility’: ‘the effect of mass migrations has been the creation of radically new types of human beings: people who root themselves in ideas rather than in places.’ Virginia Woolf proposed that ‘human character changed’ in 1910;7 Rushdie implies that 1947 would be a better date – or, the decade preceding this that saw such enforced migrations on a world scale. But this is, after all, a film review, and Rushdie concludes that the cinema itself is perhaps the place where the new may germinate: ‘And for the plural, hybrid, metropolitan result of such imaginings, the cinema, in which peculiar fusions have always been legitimate . . . may well be the ideal location.’ If new sensibilities require new forms (as they do), then Rushdie is an enthusiastic proponent of these: not only film, but also radio, the gramophone, television, video . . . all find 5 SALMAN RUSHDIE their place as both narrative material, structural device, and metaphor in his fiction. And in the late twentieth century, this is indeed the location of culture. As Steven Connor remarks, if Rushdie exploits the media in his fiction it is because ‘such forms are the evidence of a fundamentally new relationship between public and private life’.8 The argument of this essay lies at the heart of Rushdie’s understanding and practice; as we shall see, all the significant critical disagreements can be referred back here, at least for clarification. It provides the argument to back his earlier assertion that ‘Writers and politicians are natural rivals. Both groups try to make the world in their own images; they fight for the same territory’ (IH 14). It also links Rushdie to the mainstream of post-colonial culture, where the spatial metaphor has a particular appositeness. Many writers within this tradition see the imagination as defining a ‘space’ which is more metaphorical than actual. Homi Bhabha quotes Wilson Harris on the need to face up to the ‘void’, the ‘wilderness’ of realities denied, in proposing his own idea of a ‘Third Space’, not hemmed in by simple dualities, where hybridity might truly thrive.9 One might also compare the fertile idea of the ‘Fifth Province of the Imagination’ which has been proposed as the space in which to think our way beyond the categorical politics rooted in the four provinces of ancient Ireland.10 Benedict Anderson’s influential book Imagined Communities provides an elaborated model for how this imagination has been materialized in the very structure and self-identity of modern societies.11 A good practical example of these tensions in action is provided by Rushdie’s account of the ideological struggle in Nicaragua, which he observed on a visit in 1986 and wrote about in The Jaguar Smile: A Nicaraguan Journey (1987). This is much more than just a travel book. While providing, certainly, a vivid descriptive account of the precarious situation in Nicaragua in June 1986, when the triumphant but beleaguered Sandinistas, in government under Daniel Ortez, were bracing themselves for the American invasion that never came, Rushdie’s book is also a meditation on the process that goes into the making of a nation: and on how this process may (or may not) be compared to the ‘making’ of fiction. After the terror of the Somoza years, including the terror of ‘nonentity’ in the 6 INTRODUCTION Blakeian sense, when the country simply ‘wasn’t there’ (JS 157), the liberated people of Nicaragua ‘were inventing their country, and, more than that, themselves’. ‘At the Enrique Acuña cooperative . . . I had seen a people trying hard to construct for themselves a new identity, a new reality, a reality that external pressure might crush before construction work had even been completed’ (JS 86, 96). The creative process reaches through all levels of society: agrarian, administrative, cultural, political; but, somehow, it is focused by the fact that so many of the politicians are also themselves artists: poets, novelists, painters, musicians. Rushdie is particularly struck by the proliferation of poets in Nicaragua, and even finds himself described at one point as ‘hindú . . . poeta’ (JS 25). It may be appropriate to recall at this point another optimistic formulation from Shelley’s Defence of Poetry: where he says that in ‘the infancy of society every author is necessarily a poet . . . ’.12 It is almost as if the newly born Nicaragua is being created by its citizens as a work of art, like Morris’s socialist Utopia or Yeats’s mythical Byzantium. And, indeed, Rushdie does allow what Coleridge called the ‘shaping spirit of Imagination’ to direct his own discourse. ‘It is impossible’, he says after the 1972 earthquake and the Somoza ravages, ‘not to see [the city of Managua] in symbolic terms’. Meanwhile the legendary Sandino, founder of the libertarian movement, has become ‘a cluster of metaphors’; a priest delivers a homily which is ‘an extended metaphor’ of the political situation, made over in biblical and other parallels (JS 17, 22). Even the mountain range to the north of the country derives a ‘mythic, archetypal force’ from its association with the Sandinista rebels (JS 74). Five years on from Midnight’s Children, Rushdie reminds us at the beginning of this book that ‘I’ve always had a weakness for synchronicity’ (JS 11), and it is not surprising that these aspects are foregrounded in the account that follows. But (as in that novel) the patternless retributions of the real world are not to be avoided here. History is unlike fiction because (he quotes from C. V. Wedgwood) it ‘is lived forward but it is written in retrospect’. And Nicaragua likewise has to face the future: The act of living a real life differed, I mused, from the act of making a fictional one, too, because you were stuck with your mistakes. No revisions, no second drafts. To visit Nicaragua was to be shown that 7 SALMAN RUSHDIE the world was not television, or history, or fiction. The world was real, and this was its actual, unmediated reality. (JS 168) This is in stark contrast to the American perception of Nicaragua, as interpreted by an American film producer Rushdie meets: ‘You’ve got to understand that for Americans, Nicaragua has no reality. . . . To them it’s just another TV show. That’s all it is.’ This meeting takes place in the Somocista country club in Managua, where Rushdie also has a conversation with an elderly gentleman (he ‘was, of course, a poet’) who praises the Indian Writer Tagore – obstinately pronounced Tagoré – precisely for his realism. Rushdie responds: ‘ ‘‘Many people think of Latin America as the home of anti-realism,’’ I said. He looked disgusted. ‘‘Fantasy?’’ he cried. ‘‘No, sir. You must not write fantasy. It is the worst thing. Take a tip from your great Tagoré. Realism, realism, that is the only thing.’’ ’ (JS 56) You must not write fantasy: realism is the only thing. The anonymous old man’s advice faces Rushdie the novelist with his own bifurcating (or proliferating) options; and takes us back as readers to the critical alternatives in considering Rushdie’s art. And here, even if it is hidden away from the front line of conflict, there is still a war on. There are antagonists as well as allies engaged with equal passion over the disputed territory of the imagination, and everything that it represents, or comes to represent, in the real world. The most bitter and dangerous ‘battle of the books’ has been (and is still being) fought over The Satanic Verses. The ramifications and repercussions of the infamous fatwa are not the primary concern of this study, except in so far as this situation dramatizes issues that normally take a more muted form in criticism. Documents gathered in The Rushdie File (1989) remind us how central arguments over the imagination are to this debate. Ben Okri warns that ‘we are in danger of passing a death sentence on the imagination’; and Carlos Fuentes underlines the double-edged importance accorded to ‘the uses of the literary imagination’: ‘By making the imagination so dangerous that it deserves capital punishment, the sectarians have made people everywhere wonder what it is that literature can say that can be so powerful.’13 And in For Rushdie, a parallel collection of articles by Arab, African, and French writers, Edward Said says simply: ‘Rushdie is the intifada of the imagination’, the focus of the imagination’s holy 8 INTRODUCTION war.14 Although Rushdie has defended The Satanic Verses as a work of fiction, seeing the charges against the novel as a ‘category mistake’, he has also admitted that the novel has been caught up in ‘an argument about who should have power over the grand narrative, the Story of Islam’ (IH 432); and Sardar and Davies’s combatively entitled Distorted Imagination: Lessons from the Rushdie Affair attacks Rushdie on precisely these grounds.15 In what is one of the most deeply considered contributions to the debate, A Brief History of Blasphemy, Richard Webster reminds us that we need to exercise our own responsibility in these matters: ‘We need to take back our imaginative powers from the artists, novelists and poets to whom we have delegated them. For there is a danger in delegating imaginative powers just as there is a danger in delegating any powers. We need our own imaginations.’16 Rushdie is, in fact, well aware of the double-edged quality of the powers which he exercises as an author, of what happens when ‘we first construct pictures of the world and then . . . step inside the frames ’ (IH 378). But, while the process of argumentation is necessary, it is also true that it will never in itself resolve anything; and that, for a writer, in any case, ‘the real risks . . . are taken in the work’ (IH 15), in the complex and precarious navigation between real and fictional worlds. Rushdie has suggested that a book is a kind of passport, that gives us ‘permission to travel’ in the imagination (IH 276). Pursuing this metaphor, one might indeed suggest that Rushdie’s novels are navigations not so much through space (though there are journeys and destinations) nor even through time (though this is their author’s preferred dimension), but rather through levels of reality, dimensions in a more metaphysical sense – as perceived by the shifting sands of human consciousness. This is not to say that the imagination itself is either innocent or infallible. As Rushdie said of Midnight’s Children: ‘I tried to make it as imaginatively true as I could, but imaginative truth is simultaneously honourable and suspect’ (IH 10). In an excess of fervour or from the wrong kind of commitment, it may generate delusions as well as visions; and Rushdie is therefore prepared to stand in as prosecutor too. In the same essay where he proposes the imagination as the ‘key to our humanity’, he also 9 SALMAN RUSHDIE concedes that ‘the imagination can falsify, demean, ridicule, caricature and wound as effectively as it can clarify, intensify and unveil’ (IH 143). He cites the notion of ‘commonwealth literature’ itself as an instance of imaginative perversity: the category is a ‘chimera’, a ‘monstrous creature of the imagination . . . composed of elements which could not possibly be joined together in the real world’ (IH 63). The British general election of 1983 was, in Rushdie’s view, ‘a dark fantasy, a fiction so outrageously improbable that any novelist would be ridiculed if he dreamed it up’ (IH 159). The 1986 essay ‘Debrett Goes to Hollywood’ even betrays Rushdie’s disenchantment, on this score, with the cinema. In the old days he says we allowed the stars to determine our reality for us: ‘Banality made our lives unreal; they were the ones who were fully alive. So we munched our popcorn and grew confused about reality.’ But the situation has now got out of hand: ‘When murderers start becoming stars, you know something has gone badly wrong. . . . And when the techniques of starmaking, or image and illusion, become the staple of politics, you understand . . . ’(IH 328); you understand, that is, that the imagination has been enlisted for corrupt or at best for futile purposes. Recalling the critique of media images made in Nicaragua, Rushdie quotes approvingly Michael Herr’s castigation of the Vietnam represented on television and in film as a dangerous phenomenon. The media, says Herr, are guilty of deflecting the American public ‘from any true meditation about what happened there’, and so from any ‘collective act of understanding’. The movies have provided a substitute experience for the war, but ‘the war was not a movie. It was real’ (IH 334–5). Even Saul Bellow is accused of ‘investing his fiction with the absolute authority of reality’, an instance of hubris in a writer; Naipaul likewise with purveying ‘a novelist’s truth masquerading as objective reality’ (IH 351, 374). This represents perhaps a curious reversal of priorities; but it is also a useful reminder of the limitations which must be placed on the freedom of the imagination – which Rushdie is later prepared to theorize with reference to his own case. In the 1990 essay ‘Is Nothing Sacred?’ Rushdie asks himself whether his own instinctive belief in the ‘absolute freedom of the imagination’ might not represent a ‘secular fundamentalism’ with dangers of its own, ‘as likely to lead to excesses, abuses and oppressions as the canons of 10 INTRODUCTION religious faith’ (IH 418). He comes back to argue that of all the art forms ‘literature can still be the most free’, and to assert that ‘the interior space of the imagination is a theatre that can never be closed down’ (IH 424, 426); but at the end of the essay he concedes that there is no privileged category: ‘The only privilege literature deserves – and this privilege it requires in order to exist – is the privilege of being the arena of discourse, the place where the struggle of languages can be acted out.’ (IH 427). It is not only in the essays but in the novels themselves that Rushdie pursues the critique of the imagination – a theme we shall return to in the chapters that follow. Rushdie’s first published novel Grimus is an exploration of the function of the imagination itself, an allegorical narrative of how the imagination can seek to detach itself from reality and create a ‘world’ of its own, outside time and accident, but immune also to the rhythm of creation in birth and death, and the love that embraces them. It is Rushdie’s version of the familiar romantic myth of a space created by the imagination as a refuge from the responsibilities of the real world. This responsibility is fully assumed in Midnight’s Children, where the imagination is enlisted to participate in the birth of a nation, macroscopically, and at the microscopic birth of one child (and his thousand magical siblings). The story of Saleem Sinai’s first thirty years is synchronized with the first thirty years of independent India, with optimistic moments and dramatic reversals carefully crossstitched in the narrative. But even here we are not to believe everything we are told. Saleem’s father Ahmed Sinai is a victim of fantasy in his own life; his longing for ‘fictional ancestors’ leads him to ‘invent a family pedigree that . . . would obliterate all traces of reality’, and the narrator Saleem himself confesses at one point to telling self-protective lies: ‘I fell victim to the temptation of every autobiographer . . . to create past events simply by saying they occurred’ (MC 109–10, 427). The lesson to be drawn from this is that history is not only made, by events, but also made up, narrated, like the story of a life or the anecdotes within it. ‘History is always ambiguous. Facts are hard to establish, and capable of being given many meanings. . . . The reading of Saleem’s unreliable narration might be . . . a useful analogy for the way in which we all, every day, attempt to ‘‘read’’ the world’ (IH 25). It is this creative combination that falls 11 SALMAN RUSHDIE apart in Shame. Pakistan, we are told, is a country that has been ‘insufficiently imagined’, and Rushdie’s novel of near-Pakistan wrestles with a series of irreconcilable polarities: the two ‘halves’ of Pakistan itself, the deadlocked Harappa/Hyder families, and what Rushdie identifies as the competing male and female plots. Here, it may be suggested, there is no reconciling metaphor, no resolution back into history (where ‘art dies back to life’, in a phrase from a poem by D. J. Enright17); there is only the coruscation of shame itself, and the dubious promise of the novel’s apocalyptic ending. The operations of the mind itself, in its imaginative capacity, are brought into sharp focus again in The Satanic Verses, this time in a novel which is also densely realized in terms of both contemporary–historical and mythical–religious contexts. The imaginative threads and coherences that compose identity; the pivotal, polymorphous energies of the imagination producing both good and evil; the degrees of imaginative assent that constitute faith (and doubt) – all these interact in the novel, interrogating each other through different personalities (grouped around Gibreel Farishta and Saladin Chamcha), different locations (Bombay, London, ‘Jahilia’), different historical periods, contrasted states of consciousness (waking/dreaming, sane/insane, ecstatic/suicidal). Caught at one moment in these currents, Gibreel exclaims ‘if I was God, I’d cut the imagination right out of people’ (SV 122): this is where all our dilemmas are identified. How to live our lives imaginatively but free of illusion? The novel elaborates on this theme in complex counterpoint and delivers what are in effect two endings, reflecting success or failure in this very negotiation. Haroun and the Sea of Stories provides a lighter but no less illuminating account of these proceedings. The imagination can be threatened by personal unhappiness and arbitrary power, but by the same token it possesses the resources to fight back against and overcome these tyrannies. And (to take a more optimistic view of the tension between generations), the comic dimension of this fairy tale for adults is endorsed by the fact that it is a son who frees his father on the troubled sea of stories, blessing the biological ‘narrative’ with the restoration of the gift of narrative itself. The stories in East, West provide their own versions of this imaginative enterprise, introducing us to multiple selves, 12 INTRODUCTION alternative futures, instances of the problematic ‘permeation of the real world by the fictional’ (EW 94) which ask and hesitate to answer the familiar personal and cultural questions. In The Moor’s Last Sigh Rushdie returns to the materials – and to some of the methods and motifs – of Midnight’s Children, but with a very different imaginative as well as geographical perspective. There is once again a macro- and micro-narrative: this time, the greater history of the Spanish/Portuguese colonizing of Goa, and the smaller history of the Zogoiby family and firm, working the spice trade in Cochin. But what is different here is that Rushdie offers us a bifocal view of this twinned narrative, a developed metaphor for the imaginative assumption of experience. First there is the story itself, narrated in the first person by Moraes Zogoiby (‘Moor’); then there is the visual record of some of these events, in the series of paintings made by his mother Aurora over many years, which are described in great detail in the text. These reflect both the history of modern India and her own anguished family story, offering at the same time a history and a critique of artistic representation itself – from the transformations of myth through social documentary and domestic drama to the imposition of a hard, ideological overlay. So that, when a character says ‘I blame fiction’ for the problems we bring on ourselves (MLS 351), we recall that the novels mean to engage us in a continuous discussion of the subject. And, although the imagination is the ‘prime mover’ in Rushdie’s fiction, and in a sense always part of the subject itself, the novels contain their own critique of the fiction-making process, and a permanent reminder of our responsibility to the ‘real world’ – however this is to be recognized. As Steven Connor has remarked, ‘At the heart of Midnight’s Children is a curiously moralistic mistrust of the modes of the fabulous which it indulges with such zest’.18 Making our own navigation from the novels to a theory that might underpin them, we note that the arts of the imagination have to be identified and brought under discussion in formal terms – according to relevant conventions and expectations. One of the characters in Grimus expresses a preference for stories which are ‘like life, slightly frayed at the edges, full of loose ends and lives juxtaposed by accident’, over those stories which are ‘neat’, ‘tight’, and governed by ‘some grand design’ (G. 141). The 13 SALMAN RUSHDIE alternatives set out here provide a useful grounding for the formal discussion of Rushdie’s work – not least, because they expose what looks like a contradiction. On the one hand, there is the familiar breaking down of formal categories, the endorsement of multiformity: the author proposes that the form of Midnight’s Children, ‘multitudinous, hinting at the infinite possibilities of the country’, should be understood as ‘the optimistic counterweight to Saleem’s personal tragedy’ (IH 16). Likewise, if Saleem’s own vision is fragmentary, a ‘broken mirror’, nevertheless ‘the broken mirror may actually be as valuable as the one which is supposedly unflawed’ (IH 10). He suggests (in this same essay) that it is the mode of fantasy, ‘or the mingling of fantasy and realism’, that can best represent Indian reality, providing the necessary ‘double perspective’: ‘this stereoscopic vision is perhaps what we can offer in the place of ‘‘whole sight’’ ’ (IH 19) – the ‘whole sight’ which is disowned as the delusive promise of omniscient Western realism. It is significant that Rushdie’s defence of The Satanic Verses is also made primarily in formal rather than ideological terms. The novel – at least in the view of its author – ‘celebrates hybridity, impurity, intermingling, the transformation that comes of new and unexpected combinations of human beings, cultures, ideas, politics, movies, songs’; it is (he says) ‘a love-song to our mongrel selves’ (IH 394). This becomes in a later essay (‘Is Nothing Sacred?’) a defence of the novel itself: ‘the most freakish, hybrid and metamorphic of forms’, which was ‘created to discuss the fragmentation of truth’, a form which realizes its true potential in ‘challenging absolutes of all kinds’ (IH 422–5). One is reminded of D. H. Lawrence, and the advocacy by another exiled and beleaguered writer of a form which he valued precisely for its being ‘incapable of the absolute’.19 But our experience as readers of Rushdie’s fiction insists that there is another principle at work within this centrifugal fragmentation. There is also a centripetal counter-movement which seeks to bring all these miscellaneous fragments into significant relation with each other. The obtrusive coincidences, synchronicities, the anticipations and recapitulations, all those elements which even the battered Saleem sees as part of the ‘national desire for form’, are the work of an organizing intelligence, and are as essential to the arts of the imagination 14 INTRODUCTION as any other quality. Receptiveness and responsiveness, curiosity, have to be balanced, activated, by desire and design; as Coleridge reminds us, the imagination coordinates and subordinates as part of its task of invoking and celebrating.20 Rushdie’s own valuation of the ‘centripetal’ principle is clear not only from his own practice but also from comments made about other novelists. His debt to Sterne’s Tristram Shandy is as significant as it is well documented,21 because Sterne’s objective in that novel is to mask order (art) with disorder (life), to be as he says ‘digressive, and . . . progressive too, – and at the same time’,22 in effect reconciling two contrary principles. Rushdie’s own version has it: ‘to write in a form which appears to be formless’ (IH 179). Rushdie has confessed to being ‘very keen on the eighteenth century in general, not just in literature’, and his comment on another eighteenth-century masterpiece, Fielding’s Tom Jones, provides a useful sight into the writerly qualities he most admires: the thing that’s very impressive about Tom Jones is the plot, you have this enormous edifice which seems to be so freewheeling, rambling – and actually everything is there for a purpose. It’s the most extraordinary piece of organization which at the same time seems quite relaxed and not straitjacketed by its plot. I think that’s why the book is so wonderful.23 Rushdie makes another instructive parallel between his own novelistic practice and that of Fielding and Sterne in a later interview when he observes, ‘I spend much more time on the architecture of my books than on their writing. It takes me a very, very long time to understand the book . . .what connects with what and what the machine is. That’s why it takes me five or six years to write one of those big books.‘24 One has to conclude that the formal principles at work in Rushdie’s fiction are more complex than might at first be supposed. Not only is there the endorsement of hybridity (the mixture of Western and Eastern forms, of written and oral modes; the mixture of ‘fantasy and naturalism’; the mixture of genres and styles, of media and languages – all associating in an aleatory, linear time), but also the simultaneous appeal to order; to the structure of coincidence, to pattern, control; to the symmetry of biology, the purity of mathematical logic or geometric design – these having their fulfilment in the 15 SALMAN RUSHDIE complementary idea of time as cyclic and recurrent. This opposition, with its ethical and political as well as aesthetic coordinates, lies at the very heart of Rushdie’s fiction, to be revolved in different ways in each of the novels. And it is also a theme that helps conduct the critical debate. CRITICAL RESPONSES Provocativeness is not without its perils, and it will surprise no one that the critical response to Rushdie’s work includes all shades of opinion, delivered from a wide variety of viewpoints. Even if we set aside (as I shall do) the merely expletive attacks from those who have never actually read the work, there is still a body of informed opinion that takes objection to Rushdie’s work on general, ideological grounds; and it might be useful to consider the nature of these objections before proceeding further. This will involve returning to Rushdie’s claims for the imagination, which are contested by those who argue that the individual imagination is conditioned by other, underlying factors that need to be entered in the cultural equation before this faculty is allowed ‘free play’. In what was the first important book on Rushdie, Salman Rushdie and the Third World: Myths of the Nation (1989), Timothy Brennan develops a critique of the kind of imaginative investment made (or not made) by Rushdie, Vargas Llosa, and other ‘cosmopolitan writers of the Third World’ whose attitude to the national myth exhibits what he calls a ‘creative duplicity’.25 With them, argues Brennan, the familiar figures of ‘allusion, metaphor, allegorical parable are all like nationalism itself, ‘‘janus-faced’’ ’, with one face looking west. He quotes Gabriel Marquez’s definition of the imagination against both Marquez himself and Rushdie: if Marquez believes that ‘the imagination is nothing more than an instrument for elaborating reality’, then it should be used more responsibly. ‘Their shockingly inappropriate juxtaposition of humorous matter-offactness and appallingly accurate violence, both ironically alludes to the blasé reporting of contemporary news and the preventable horrors of current events.’26 Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children may, he says, have put ‘the Indo-English imagination on the map’, but only through being parasitic on earlier developments. Writing of 16 INTRODUCTION the Pakistan we meet in Shame, Brennan accuses Rushdie of destroying ‘any coherence his imagination may have given the country by adopting a formal attitude that makes every statement capable of being at the same time withdrawn’,27 a revealing criticism (picking up the ‘janus’ image) which disallows – or simply fails to understand – the inherent duplicity of the imagination, as defined by Swift, developed by Sterne, and inherited by Rushdie from this and other traditions of storytelling. As Milan Kundera has argued, in fiction ‘the unique truth is powerless’, since the ‘satanic ambiguity’ which is the novel’s privilege ‘turns every certainty into enigma’.28 It is significant that Brennan also objects to Rushdie’s irony, endorsing Gramsci’s preference for ‘impassioned sarcasm’ as ‘the appropriate stylistic element for historical-political action’.29 Aijaz Ahmad certainly seems to have schooled himself on sarcasm for his follow-up attack on Rushdie in In Theory (1992). The chapter on Shame in this book is a systematic attempt to disqualify Rushdie’s writing through a closely argued but nevertheless tendentious analysis of his imaginative formation. ‘How very enchanting’, he reflects, ‘Rushdie’s kind of imagination must be’ for readers brought up on a certain kind of modernist universalism. ‘One did not have to belong, one could simply float, effortlessly, through a supermarket of packaged and commodified cultures, ready to be consumed’.30 Ahmad challenges what he calls the ‘grid of predispositions which have gone into the making of such an imagination’, on the way to rejecting ‘the whole imaginative topography of modernism’.31 Ahmad’s own ‘predispositions’ are clearly otherwise, as is revealed in this summary of the situation in the attending novel, Shame: For so wedded is Rushdie’s imagination to imageries of wholesale degradation and unrelieved social wreckage, so little is he able to conceive of a real possibility of regenerative projects on the part of those who actually exist within our contemporary social reality, that even when he attempts, towards the end of the novel, to open up a regenerative possibility, in the form of Sufiya’s flight . . . the powers which he, as author, bestows upon her in the moment of her triumph are powers only of destruction. Ahmad too is wrongfooted by Rushdie’s ambivalence, protesting at the ‘linguistic quicksand’ in this novel, ‘as if the truth of each utterance were conditioned by the existence of its opposite’32 – a 17 SALMAN RUSHDIE valuable insight, were it not offered ironically. (As Oscar Wilde reminded us, ‘a Truth in art is that whose contradictory is also true’.)33 The work of Brennan and Ahmad may be taken as sufficiently representative of the denigration of Rushdie’s work by certain ‘post-colonial’ critics – those who would tie in the novel form deterministically to Western ideological formations, and read individual novels for signs of their authors’ ignorance, fallibility, or opportunism. Brennan challenges not only the critical reception but the very authenticity of writers such as Rushdie, Vargas Llosa, Carlos Fuentes, and Isabelle Allende, and what he reads as their implicit claim to ‘represent’ Third World realities. Drawing on Gramsci’s analysis of the unaffiliated intellectual in Italy in the 1930s, who becomes ‘cosmopolitan’ because of the political fragmentation of that country, and also the adoption of the term by Frantz Fanon to describe the parasitic middle class in emergent African states, Brennan develops his own notion of the ‘Third World cosmopolitan’ as someone (whether politician, writer, or global industrialist) whose cultural allegiance is to a First World order, severed from any national, collective, or democratic reference. As a result, these values will tend to appear only in parodic or otherwise distorted forms. Rushdie has been selected by this critic as an example of a cultural and political argument of his own, and his criticism is heavily conditioned by a set of beliefs which perceive literature as ‘politicized in the prescriptive sense’, and functioning as ‘a social institution with interventionary powers’.34 Ahmad meanwhile blames Rushdie’s descent from modernism for his ‘bleak vision’, his ‘aesthetic of despair ’. The ‘highly pressuring perspective of modernism’, he suggests, ‘uses the condition of exile as the basic metaphor for modernity and even for the human condition itself’, preventing any real engagement with history. Reading Shame, he objects, ‘one is in danger of forgetting that Bhutto and Zia were in reality no buffoons, but highly capable and calculating men whose cruelties were entirely methodical’.35 This puts one in mind of the blank objections raised against storytelling by Mr Sengupta in Haroun and the Sea of Stories: ‘What’s the use of stories that aren’t even true?’ (HSS 20). Mr Sengupta would have been ill-advised to become a literary critic. Taking up a similar post-colonial perspective in an 18 INTRODUCTION essay called ‘From Politics to Poetics’, Tim Parnell likewise criticizes the way Rushdie’s novels operate on the ‘boundaries between the fictional and the historical ’. For him, the novels’ complexity reflects the ‘labyrinth cunningly constructed by an imperial past’, and thereby ‘does appear to deny the peoples of India and Pakistan the possibility of escaping’ from it. Somehow it becomes the fault of fiction that, for all its imaginative exploration, ‘the established structures of power remain undisturbed’. And so Parnell concludes that the ‘waning of Saleem’s magic powers’ in Midnight’s Children ‘might be read as a metaphor for the political limitations of Rushdie’s attempts to harness postmodern poetics to a postcolonial political agenda’.36 It is worth recalling at this point James Harrison’s very reasonable question: ‘upon what compulsion . . . must Rushdie meet the criteria for salvation specified by some post-colonial catechism?’37 One is surely entitled to suspect criticism that fails to see what is actually there in a writer’s work, and compounds that failure by lamenting the absence of something derived from its own prescription. Keith Wilson is a more reliable guide when he suggests that ‘what Rushdie presumes in his reader, and what he makes the base of his narrative strategy, is an ability to read a text as literature, with an instinctive understanding of the nature of the process that is under way’.38 It is only when we can read literature disinterestedly, with an awareness of this process, that we can safely negotiate between it and other discourses. Malise Ruthven provides the model for such a negotiation in the chapter ‘Satanic Fictions’ in his A Satanic Affair (1990). Ruthven begins from the position that, though Rushdie, while being a novelist, is also both journalist and activist, his fictional critique ‘contains an ambivalence’ that sets it apart, makes it something qualitatively different from the social intervention. It is the nature of novelistic discourse that ‘form rather than content becomes the vehicle of dissent’.39 He quotes a review by Brad Leithauser from the New Yorker, which argued that The Satanic Verses ‘is so dense a layering of dreams and hallucinations that any attempt to extract an unalloyed line of argument is false to is intention’. He also cites Gayatri Spivak’s view that there is ‘no clear boundary between religion and fiction as products of the imagination’ in the novel, on the way to arguing on his own account that the novel should be seen as ‘a kind of ‘‘anti- 19 SALMAN RUSHDIE Qur’an’’ which challenges the original by substituting for the latter’s absolutist certainties a theology of doubt.’40 And this takes us into the formal heart of the ideological argument. ‘For the novel as a genre has an ideology – it is an ideology – of its own, one that lives by attacking the tendency of ideology itself to abandon ‘‘the wisdom of uncertainty’’ in the pursuit of a totalizing system.’ Thus Michael Gorra in After Empire.41 And, although this implies potential conflict with a whole range of ideologies, it is inevitably the dramatic conflict with militant Islam that has occasioned most commentary. One may cite Milan Kundera again: ‘theocracy goes to war against the Modern Era and targets its most representative creation: the novel’.42 The fundamentalist response to what Brennan calls the ‘provocation’ to Islam is documented in The Rushdie File, and developed in the extensive literature on the ‘Rushdie Affair’.43 But, if one is trying to defend a space for fiction, not just in theory but in conflictual praxis, one must acknowledge the intervention of those Islamic scholars who have themselves spoken up in Rushdie’s defence. First published in French (with many articles translated from Arabic) in 1993, the volume For Rushdie: Essays by Arab and Muslim Writers in Defense of Free Speech is an impressive collection of nearly a hundred articles written from what the editors refer to as ‘the currently devastated city that is Islam today’ towards that fictional place where ‘the prophetic gesture has been opened up to the four winds of the imaginary’.44 It is from a similar perspective that Sadik Al-Azm defends Rushdie against the ‘archaism’ of Islam, linking him to a long tradition of writers and film-makers (from Rabelais to Scorsese) whose work represents a necessary challenge to repressive authority both religious and secular.45 And in the course of an excellent, clarifying article on the issues surrounding The Satanic Verses, which relocates these in the discourse of satire itself, Srinivas Aravamudan asks the pertinent question: must there not be ‘a polytheistic blasphemy lurking under every resolute monotheism?’ It is significant that Aravamudan cites the authorial duplicities of Swift here, and the model of the anarchic imagination we have already referred to, in A Tale of a Tub.46 The satirist is never innocent; but we must ask ourselves, of what exactly is he guilty? It is strange – almost perverse, in this context – that Stephanie Newell should suggest in her article 20 INTRODUCTION ‘The Other God: Salman Rushdie’s ‘‘New’’ Aesthetic’, that Rushdie sets up in The Satanic Verses a text which is to be read as a dogmatic alternative to the Koran itself; that Rushdie’s ‘allcontrolling creative Ego’, functioning as ‘arbiter of reality’, imposes a ‘quasi-theological new Truth’ upon the reader. This essay, often cited, is a good example of how a perverse reading can turn the text against itself, making a ‘prison’ (the term is actually used in the argument) of what is offered as an imaginative adventure.47 A second ideological construction that we need to consider is that of gender politics. The subject of gender represents, as we know, one of the most sensitive critical issues of our time, and it has to be said that Rushdie’s work has sustained a good deal of adverse response in this connection. The narrator of Shame tells us that the ambiguous hero Omar Khayyam ‘developed pronounced misogynistic tendencies at an early age’ (S. 40), and it has become almost a critical reflex to pass on the charge to Rushdie himself (relating this, often, to the Islamic culture which provided him with his own formative experience). Catherine Cundy, in her otherwise even-handed treatment of Rushdie, is consistently critical of this aspect of his work. His ‘tendency to demonize female sexuality’, his ‘ambivalence if not outright confusion’, are, she says, declared in Grimus, repeated in Midnight’s Children (where she defends even Indira Gandhi against presentation ‘in such relentlessly misogynist terms’), and confirmed in Shame, where the ‘blend of confusion, frustration, and even outright hostility’ to women is ‘more evident . . . than anywhere else’.48 Which does not, however, spare the later novels. Cundy rests her case with the proposition that the treatment of women in Rushdie’s novels ‘serves more as a revelation (albeit involuntary) of Rushdie’s psychology’ than it contributes to the fiction.49 The shallower side of this argument is exemplified by Inderpal Grewal, who decides for herself that ‘what Rushdie writes for’ is ‘the improvement in the lot of Pakistani women’, and then accuses him of failing to deliver. It is characteristic of such criticism that she goes on to prescribe the novel Rushdie should have written: ‘If Rushdie had drawn upon a history of struggle instead of a history of subjection, his novel could have provided a myth of struggle and liberation that would have helped present and future struggles’.50 Anuradha 21 SALMAN RUSHDIE Dingwaney Needham, on the other hand, is prepared to look beyond the declared and dramatized positions of Rushdie and his characters to the field of discourse within which these occur: ‘We do not . . . find a unitary, monolithic identity in Rushdie; rather, his work reflects a conception of post-colonial identity that is fluid, multiple, shifting, and responsive to varied situations and varied audiences.’ For her, Rushdie does not create an ’utopian or visionary space’ for women; he seeks rather ‘to expose the particular and horrifying conditions of their oppression’. Needham concludes her essay with an account of her experience as reader and teacher of Rushdie’s fiction. This has revealed that ‘Rushdie’s construction of post-colonial identities . . . is particularly enabling’, and his two novels Midnight’s Children and Shame ‘have turned out to be wonderful texts with which to begin and end a course on ‘‘Third World’’ literature in English’.51 It should be easier to characterize the response to Rushdie’s fiction from a formal point of view, if only by default, in that even the adverse ideological criticism concedes the formal originality of his work. And there is indeed a consensus that, if Rushdie has ‘put the Indo-English imagination on the map’, it is substantially due to his mastery of the eclectic modes of fiction. But the very fact of Rushdie’s eclecticism has actually made it difficult for critics to interpret Rushdie’s formal project. In the introduction to his substantial collection of essays Reading Rushdie, M. D. Fletcher sets up a battery of formal terms, hesitating in his attribution between different categories as well as forms and styles: the postmodern and the post-colonial, metafictional strategies of various kinds (including parody), oral tradition and magic realism, forms of satire, polyphony, metamorphosis, and the grotesque.52 And the essays themselves do not provide a more coherent picture. Grimus defeats critical ingenuity, Ib Johansen proposing it is ‘a strange blend of mythical or allegorical narrative, fantasy, science fiction, and Menippean satire’, while Catherine Cundy settles here for the formula ‘chaotic fantasy’.53 Peter Brigg sees Midnight’s Children as a ‘mixture of comedy, grotesque, and intellectual puzzle’,54 while The Satanic Verses is variously described as comic burlesque, an intermingling of fabulism and surrealism, encyclopaedic, carnivalesque, an example of ‘enantiomorphism’ (that is, characterized 22 INTRODUCTION by oppositional structure), a ‘Wo/manichaean novel’, a Manichaean allegory, the apotheosis of gossip (‘an underrated medium’), an epiphanic tragedy, and the first postmodern Islamic novel.55 For all the ingenuity sometimes displayed in these formal identifications, there is little critical insight or real orientation offered to the reader. The more illuminating descriptions are provided by those critics who are less concerned to label the novels (like Saleem’s pickle jars) but remain alert to their distinctive flavours, however these may be communicated. Sometimes this will be by impressionistic comparison, as when Uma Parameswaran compares the structure of Grimus to a Rubik cube, or when Keith Wilson finds the technique of ‘literary pointillism’ in Midnight’s Children; with Patricia Merivale’s ‘comic zeugmas’ and ‘grotesque shifts of perspective’ in the same novel;56 with those critics elsewhere who have noted Rushdie’s characteristic use of repetition, recapitulation, and prolepsis, as well as the distinctive palinode;57 and those who have drawn attention to his debt to the art of cinema.58 Academic criticism has found Rushdie’s fiction fertile ground for the study of influences and intertextual reference – much of it interesting and informative within the limited terms accepted by such an exercise. Rushdie’s declared debts to Cervantes, Sterne, Joyce, Grass, and Marquez have been extensively (if not exhaustively) explored. However, the less obvious but no less pervasive influence of other writers deserves further study. One thinks not only of Shakespeare, and the exemplary eighteenthcentury writers (other than Sterne) – that is to say, Defoe, Swift, and Fielding; but also of Blake and Dickens; Kafka and Bulgakov; Yeats, Beckett, and Ted Hughes: from all of these Rushdie has derived perspectives that are deeply set at thematic and even structural levels, as well as traceable verbally in the work. There has so far been no specific or extended treatment of Rushdie’s interplay with any of these authors, which would certainly add to our appreciation and understanding. Meanwhile, it is that criticism that has been able to relate Rushdie’s work to its Eastern as well as its Western sources which has proved a useful corrective to the kinds of cultural appropriation occasionally described above. Uma Parameswaran’s 1988 collection of her own essays, The Perforated Sheet, is one valuable contribution here; as are the two pieces on Rushdie in Sara 23 SALMAN RUSHDIE Suleri’s The Rhetoric of English India (1992). Both these authors feature in Fletcher’s collection, alongside others (Aravamudan, Bharucha, Sadik Al-Azm) who represent Indian and Arabic traditions. The Novels of Salman Rushdie (edited by G. R. Taneja and Rajinder Kuman Dhawan, New Delhi, 1992) contains two dozen essays by mainly Indian critics, reprinted from two issues of the Commonwealth Review in 1990. One should also draw attention to articles which have appeared since 1980 in journals such as ARIEL, The Journal of Commonwealth Literature, The Journal of Indian Writing in English, Kunapipi, Wasafiri, World Literature Today, and World Literature Written in English. LANGUAGE All these critical explorations have to do in some measure with the recognition of Salman Rushdie’s originality as a writer, whether this is defined in formal terms or according to Ashis Nandy’s deep-field formula – the ‘reinterpretation of tradition to create new traditions’.59 But we cannot consider the nature of Rushdie’s originality without finally making some reference to language itself, the writer ’s immediate and conditioning medium. The question proposed in The Satanic Verses – ‘How does newness enter the world?’ – presents itself first of all in linguistic terms. From Grimus onwards, Rushdie was in the business of inventing not just worlds but languages; the languages of groups, trades, professions, cliques, as well as the distinctive Dickensian idiolects of individuals. And language also makes itself available as metaphor for the creative process, when the midnight child is in the womb: ‘What had been (at the beginning) no bigger than a full stop had expanded into a comma, a word, a sentence, a paragraph, a chapter; now it was bursting into more complex developments, becoming, one might say, a book – perhaps an encyclopaedia – even a whole language . . .’(MC 100). According to Rushdie, it is the migrant writer who is best placed to act as midwife as language itself is new-delivered; the migrant who has experienced the double loss of being ‘out-of-country and out-of-language’ and ‘enters into an alien language’ where he is ‘obliged to find new ways of describing himself, new ways of being human’ (IH 12, 278). 24 INTRODUCTION Intriguingly, Rushdie proposes Joyce as the honourable antecedent to this tradition;60 one could perhaps add Conrad, before passing on to the familiar roll-call of ‘writers from elsewhere’ who have remade English for their own purposes. ‘To conquer English may be to complete the process of making ourselves free’ (IH 17). And English, as it happens, has proved easily accessible. In the essay ‘Commonwealth Literature’ Rushdie argues that if ‘those peoples who were once colonized by the language are now rapidly remaking it’, this is partly due to ‘the English language’s enormous flexibility and size’, which allow newcomers to reverse the colonial process by ‘carving out large territories for themselves within its frontiers’ (IH 64). The ‘territory’ of language shares a dimension here with the contested space of the imagination. This idea is repeated in the formulation whereby books provide us with ‘new and better maps of reality’, ‘new descriptions of the world, new maps for old’ (IH 100, 202). And, if English is the world language, we should be prepared to forgo academic (or political) categorizations and recognize the novel as its world literature. ‘I think that if all English literatures could be studied together, a shape would emerge which would truly reflect the new shape of the language in the world’ (IH 70). But it is not simply a matter of the English language. Rushdie celebrates what he calls the ‘polyglot family tree’ of the novel, citing Gogol, Cervantes, Kafka, Melville, and Machado de Assis (IH 21); and his references to Grass, Llosa, Fuentes, and Kundera remind us that it is the novel’s engagement with language as such, mingling discourse within and between cultures, that is its distinguishing feature – both rhetorically and ideologically. Rushdie quotes Fuentes: ‘Impose a unitary language: you kill the novel’; and in his own person he insists that the novels he values are those ‘which attempt radical reformulations of language, form and ideas’ – fulfilling the novel ’s brief ‘to see the world anew’ (IH 420, 393). All this is consistent with his own purpose, which has been ‘to create a literary language and literary forms in which the experience of formerly colonized, still-disadvantaged peoples might find full expression’ (IH 394). Rushdie’s own criticism of other writers is very alert to their qualities of language,61 and in the case of G. V. Desani (with his 1947 novel All About H. Hatterr) he acknowledges a direct 25 SALMAN RUSHDIE influence. Desani’s ‘dazzling, puzzling, leaping prose is the first genuine effort to go beyond the Englishness of the English language’ – not surprising, then, the admission that ‘my own writing . . . learned a trick or two from him’.62 It seems appropriate, therefore, that there are critics who have devoted their attention to this aspect of his work. Rustom Bharucha’s essay ‘Rushdie’s Whale’ offers an enthusiastic commentary on Rushdie’s linguistic energy and inventiveness, the way he has ‘bastardized . . . hybridized . . . and cinematized’ the English language for his own special purposes; to stock the ‘gargantuan storehouse of words’ that is Midnight’s Children, to work the subtly embroidered lexis for Rani Harappa’s shawls in Shame. It is Bharucha’s close focus on Rushdie’s language that allows him to claim that ‘there is a stronger emphasis [in Shame] on the elemental than on the political, the inexplicable rather than the rational’, and to identify the imaginative world-swallowing required of the reader by Saleem Sinai as essentially a verbal exercise. ‘Rarely in literature has a writer displayed a greater hunger for words, an almost frightening openness to the history of his universe’.63 Jacqueline Bardolph’s ‘Language is Courage’ likewise proposes that ‘the courage to conceive certain thoughts, the courage of the imagination’ is inherently a linguistic phenomenon.64 One may take a useful critical cue (again) from James Harrison here, when he remarks that ‘almost everything one can say about Rushdie’s novels is exemplified in his prose style’.65 It is to this linguistic phenomenon, this prose style, as well as to the exciting ideas and structures that they mediate, that the present study of Rushdie is addressed. And, after these necessary preliminaries, we may now return to Rushdie’s own ‘preliminary’ novel, Grimus, which (reviewed as it was alongside David Lodge’s Changing Places) set such a puzzle for his first unsuspecting readers. 26 2 Grimus Rushdie’s first attempt at fiction was a novel on Indian themes (called ‘The Book of the Pir’), which remains unpublished; though some of the abandoned material may have found its way later into Midnight’s Children.1 Grimus represents a radically different departure. It was conceived as a contender for the Science Fiction Prize offered annually by Victor Gollancz, who published the novel; but it is hardly surprising that it was not selected as a specially successful example of the genre. Although it does have the authentic intellectual excitement associated with such fiction, and is constructed with great ingenuity, there are too many other things going on, too many other interests being served, for it to have the distinctive science-fiction polish. As we have already noted, the transgression of genre categories has remained a consistent feature of Rushdie’s fiction, and this is due both to the eclectic traditions from which he has drawn and the desire – traceable to the novel’s origins – to make something new in the world. Like his admired Fielding, Rushdie thinks of the novel (still) as a ‘new province of writing’,2 and we will better understand his experimentation, the rules broken, the risks taken, and the demands made on the reader, if we share a sense of the urgency with which he persuades the novel to ‘forge . . . the uncreated conscience’ of the reader, as Joyce had proposed to do in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man – one of the modern novels to which Rushdie most frequently alludes.3 Grimus is a novel about knowledge and power; about mortality and immortality; about static forms and metamorphic engines; above all, it is about the use and abuse of the human imagination. As such it engages immediately with Rushdie’s major themes, perhaps prematurely and therefore in a way that cannot yet do them justice: but it has nevertheless the virtues of 27 SALMAN RUSHDIE a young writer’s confidence, daring, and uninhibited experimentation. The narrative that carries the theme echoes one of the primal fictions: the arrival of a lone man on an island, his perilous adventures among its inhabitants, his moral crisis and apotheosis. It also follows one of the elementary structural patterns, divided as it is into three parts (like Dickens’s Hard Times and Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse; and, incidentally, Rushdie’s own Midnight’s Children): Times Past, Times Present, and Grimus. But the individual in question is no industrious Robinson Crusoe, constructing an identity as he works at his survival. Rushdie’s first hero ‘Flapping Eagle’ is a fictional confection for our own postmodern times, a walking paradox – a white American Indian of ambivalent sexual status who has drunk an elixir of life condemning him to immortality, and who finds his way to Calf Island, somewhere in what was once the Mediterranean, in consequence of a futile suicide attempt. He has simply ‘fallen through a hole in the sea’ (G. 14) to this other half-place. We are told about Flapping Eagle’s previous history in a twenty-page flashback (chapters 2–7), which details his intense relationship with a sister ‘Bird-Dog’ and their mutual enslavement to the magician Mr Sispy, who gives them two elixirs: ‘yellow for the sun and brightness and life and blue for infinity and calm and release when I want it. Life in a yellow bottle, death blue as the sky.’ Bird-Dog drinks the yellow bottle and smashes the blue one: ‘Death to death.’ Flapping Eagle drinks the one and keeps the other (G. 20–4). He becomes the lover of Livia Cramm, who tells him ‘where you walk, walks Death’ (G. 27); the contents of the blue bottle are his strength, his secret. At her death (or murder, in the complexities of the plot: they will meet again on Calf island), Flapping Eagle sets off on a symbolic voyage in her yacht – and in italics, as if to underline the elementary, pre-personal nature of his journey. He was Chameleon, changeling, all things to all men and nothing to any man. He had become his enemies and eaten his friends. He was all of them and none of them. He was the eagle, prince of birds; and he was also the albatross. She clung round his neck and died, and the mariner became the albatross . . . these were the paradoxes that swallowed him. A man rehearsing voices on a cliff top. . . I am looking for a suitable voice to speak in. 28 GRIMUS And after a while, he realized he had learnt nothing at all. The many, many experiences, the multitude of people and the myriad crimes had left him empty; a grin without a face. . . . He lived the same physiological day over and over again. (G. 31–3) This is clearly to be read as a kind of proto-fiction. The impacted literary references (to Coleridge’s ‘Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ and Hughes’s Crow as well as to Rushdie’s main bird-inspiration, Farid-ud-din ’Attar’s The Conference of the Birds) along with the prodigality of unrealized incident prevent any real engagement in the narrative. But then Rushdie’s technique is typically more demonstrative than affective. Flapping Eagle is being invested here as the first of Rushdie’s mental travellers, his voyagers through remote regions of the mind, navigators of the destructive element; and the process if not the personality does therefore command our interest. This is the mode of epic rather than of psychological fiction, to which we will become attuned as we read further in Rushdie’s work. Flapping Eagle has lost the death-dealing blue bottle as Sinbad might have done, ’down a monster’s throat’; and hence the failed suicide attempt that delivers him up on the island. Calf Island, as we might expect, is no ordinary desert island either. It is a high-tech, sci-fi time zone which has more in common with Swift’s Flying Island of Laputa or Blake’s Island in the Moon – or any such fantastic mental structure – than with the painstaking reality of Crusoe’s island with its fragile pots and precariously harvested corn. It is associated with purgatory, the medieval escape hatch from heaven and hell, via a system of references to Dante; more specifically, it has something of the Catholic theologians’ consolation prize of limbo, that sterile heaven for unbaptized souls. It also has curious affinities with the mysterious mountain in Spielberg’s film Close Encounters of the Third Kind, released the same year Grimus was published. Book and film share the same seventies taste for high-tech mysticism, and the kind of synthetic mythology that had been popularized by Herman Hesse in The Glass Bead Game and other ‘anthropological’ novels around this time. The novel does, therefore, as Brennan complains, ‘lack a habitus’,4 but whether this entails failure as a fiction is another matter. It presents us deliberately with a country of the mind, the collective fiction of those who have betrayed their full and 29 SALMAN RUSHDIE frail humanity, an ‘island of immortals who had found their longevity too burdensome in the outside world, yet had been unwilling to give it up’ (G. 41). Fittingly, the centre of its power, and the symbol of its petrification, is the Stone Rose, conceived and created by the bird-man Grimus, Flapping Eagle’s ultimate antagonist, whose name is an anagram of Simurg, the creatorbird from the Persian Book of Kings. Grimus himself, whom we meet only in Part Three, is part bird-man, part Prospero, part Pozzo/Hamm: first of those composite figures of questionable authority that Rushdie has refashioned from a ‘tradition’ (if it can even be called that) beginning with the oral epics and coming down to Kafka and Beckett. But we are to meet Grimus only later. Flapping Eagle is introduced to the island by Virgil Jones, a decayed Beckettian migrant with his rocking chair and bicycle, who ironically administers the ‘kiss of life’ to the would-have-been suicide, recognizing in him (and revealing in himself) not so much a person as a series of literary allusions. It is Virgil Jones who gives Flapping Eagle his first lesson in plural realities, the terms of which will immediately catch the attention of readers of Rushdie’s later work. Is it not a conceptual possibility that here, in our midst, permeating all of us and all that surrounds us, is a completely other world. . .? In a word, another dimension . . . . If you concede that conceptual possibility . . . you must also concede that there may well be more than one. In fact, that an infinity of dimensions might exist, as palimpsests, upon and within and around our own . . .’ (G. 52–3) Even Flapping Eagle protests here that he does not see the relevance of Jones’s ideas to his search for his sister (which is how he himself understands his quest at this stage), anticipating the impatience of certain readers with what will appear to others as one of Rushdie’s more engaging habits as a writer – his willingness to be distracted from the narrative by any stray idea that seems to offer discursive possibilities. Virgil Jones persists, introducing him to the Spiral Dancers, who had ‘elevated a branch of physics until it became a high symbolist religion’, and found at the heart of matter ‘the pure, beautiful dance of life’ – which may possibly be the first celebration in fiction of the structure of DNA (G. 75). It is Virgil Jones who has gone as far as 30 GRIMUS possible, through his discipleship of Grimus himself, in creating by imaginative synthesis a viable, hospitable reality: ‘With sufficient imagination, Virgil Jones had found, one could create worlds, physical, external worlds, neither aspects of oneself nor a palimpsest-universe. Fictions where a man could live. In those days, Mr Jones had been a highly imaginative man’ (G. 75). It is Virgil Jones, Sancho Panza to his Don Quixote, who leads Flapping Eagle to the city of K, and to the eventual crisis of his conflict with Grimus in Part Three. Like any mythical contender facing ‘his own particular set of monsters’ (G. 84), Flapping Eagle has to prove himself by surviving other encounters first. He has already destroyed Khallit and Mallit (G. 77–9), two paralysing ‘extrapolations of himself ’ who seem with their coin-tossing ritual to have migrated from Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead; he has destroyed an alter-ego constructed of his own selfdoubt, and been offered ironic advice by Jones: ‘You really must do something about your imagination, you know. It’s so awfully lurid’ (G. 88–9). Now, like Homer’s Odysseus, or Bunyan’s Christian, he must survive the temptations and distractions of the road. He must meet those who have come voluntarily, if for their different reasons to Calf Island, to follow the ‘Way of K’: where they ‘like to think of [themselves] as complete’ (G. 123), beyond change, beyond question. There is the beautiful Elfrida Gribb, who when suffering insomnia will ‘ride through K on a small velvet donkey’ (G. 108), locked in improbable love of her gnomelike husband Ignatius Quasimodo Gribb, one-time university professor and now author of The All-Purpose Quotable Philosophy. The moment Flapping Eagle meets her synchronizes with a ‘blink’, a malfunction in the intellectual system that keeps the island in being – as theologians propose that our universe depends, second by second, on God’s continuous creative vigilance. The nature of the ‘blink’ has all the neatness of one of the technical ideas invented by Kurt Vonnegut to make his fictions work, and Rushdie handles it very cleverly – just as he juggles expertly with the different dimensions, his plural worlds themselves. He meets the ‘drinking community of K’ in O’Toole’s bar, the Elbaroom. There is Flann Napoleon O’Toole himself (‘An Irish Napoleon was a concept so grotesque it had to end up like O’Toole’ (G. 111) ), who lives in a ‘haze of obscenity and vomit’, 31 SALMAN RUSHDIE revelling in threats of violence, ‘a masturbation of power’ (G. 123). And there are his two most regular customers, One-Track Peckenpaw and Anthony StClair Peregritte-Hunte, otherwise known as The Two-Time Kid. He meets Madame Jocasta, and the distinctive girls who work in her brothel The Rising Son (sic); and ‘the most beautiful man in the world’, Gilles Priape. The description (and the punning name) make us observe that, among other things, Grimus familiarizes us with a regular feature of Rushdie’s style, his addiction to what we might call the ‘narrative superlative’, the gratuitous hyperbole, a feature which consciously looks across to folk tale, fairy tale (and their parodic forms), rather than to the tradition of realist fiction. Indeed, the play of verbal and grammatical functions – such as the puns and anagrams indulged in here (the Gorfs actually live on anagrams) – are not to be dismissed as juvenile tricks, but recognized as a permanent and important aspect of Rushdie’s stylistic address. But the narrative must take its course. After a fight in the bar, where Jones is assaulted by O’Toole, Flapping Eagle goes to stay at the Gribbs’ house, where he learns of his host’s determination to return philosophy to the people in popular forms: ‘it’s all there to use, in old wives’ tales, in tall stories, and most of all . . . in the cliché’ (G. 129). Another strand is here caught from contemporary media culture: McLuhan’s From Cliché to Archetype had appeared in 1970. But Gribb is unwilling to enlighten Flapping Eagle about Grimus, leaving him even more determined to find out for himself ‘whether he was fact or fiction’ (G. 132). He is introduced to the Cherkassovs (G. 137), Aleksandr and Irina, self-exiled Russian aristocrats who are still living the revolution: ‘What were we, after all, but dogs who had had their day? Night and the executioner awaited us all’ (G. 139). Irina confides in Flapping Eagle that she was frozen in time when three months pregnant, her foetus ‘as frozen within me as the lovers on the grecian urn’ (G. 146). This prompts Jones’s observation that ‘Obsessionalism, ‘‘single-mindedness’’, the process of turning human beings into the petrified, Simplified Men of K, was a defence against the Effect’ – that is, against the play of relativities that constitutes real existence (G. 149). Meanwhile, her idiot son (in another parodic Beckettian image) plays draughts with chess pieces, locked in a shed at the bottom of the garden. All these people are voluntarily trapped. They have surrendered their complexity to the Island, 32 GRIMUS and must now deny there is any other reality; or that there is a Grimus to superintend it. Only Virgil Jones and Flapping Eagle know better; only they can move about in the Dimensions. And also the sinister Nick Deggle, previously exiled from the Island (specifically to recruit Flapping Eagle: we have met him earlier, in chapter 5), but now returned, with a piece he has snapped off the Stone Rose, causing a malfunction in the reality system which is registered by the recurrent ‘blink’ in the narrative. Flapping Eagle’s temptation by the two women represents his own ‘obsession’. It is not for nothing that he is known as ‘Death’, because when both Irina and Elfrida fall in love with him their own fixed reality system begins to break down. As it turns out, there are to be four funerals but no wedding in this novel; and this reference to Mike Newell’s popular film (from 1994) is not inappropriate, since the ‘flavour of . . . old films’ is another element deliberately fed into the novel as part of its informed cultural perspective. As Ignatius Gribb reflects at one point, ‘If he was to be in a bad Western, he might as well wear the full uniform’ (G. 183, 185). It is at this point, in Part Three, that Flapping Eagle goes in quest of Grimus himself, accompanied by Media, a whore from Jocasta’s brothel with a suitably updated name who replaces Virgil Jones in the series of allusions – now playing Beatrice to his Dante. The crisis in the novel is reached when he finally meets Grimus, in the two last (and longest) chapters. In the first of these (chapter 54) the terms of the confrontation are set up – to the effect that as Flapping Eagle he is Grimus’s double, with whom conflict is therefore inevitable. We learn also (from Virgil Jones’s Diary) of the discovery of the Stone Rose itself, the ‘geometric rose’ (G. 208), by Jones and Deggle, and Grimus’s dominance through his superior handling of its powers. It is Grimus who has led the other two on their ‘Conceptual Travels’ to the planet Thera (a transparent anagram of earth), and who names and colonizes Calf Island itself; leaving them, however, with an ontological uncertainty: ‘Impossible to say whether we found the island or made it’ (G. 210–11). But, if the Rose is a metaphor for the imagination, then this frozen world is an abuse of the imagination – a case of the sterile ‘invention without discovery’ considered in the introduction. This intellectually compromised and morally corrupt proceeding was allegorized 33 SALMAN RUSHDIE for the nineteenth century in Tennyson’s poem ‘The Palace of Art’; and, as in that poem, things here start to go wrong. Deggle tries to smash Grimus’s ‘infernal machine’, while Jones is assailed by ‘an army of terrors from the recesses of my own imagination’ – which Grimus puts down to ‘Dimension-fever’ (G. 216). It remains only for Liv to humiliate Flapping Eagle sexually (‘breaking down the last barrier . . . his sexuality’) before he is ready to meet Grimus on the same plane: ‘he has moved from a state of what I should call self-consciousness to a state of what I would humbly term Grimus-consciousness’ (G. 222). The meeting takes place in Grimus’s house at the top of the mountain – a mountain which is ‘a model for the structure and workings of the human brain’ (G. 232). Mountains feature regularly in Rushdie’s fiction, where they are associated both with danger and with spiritual enlightenment. This association derives among other sources from the landscape of the poem The Conference of the Birds, and also from the story of the prophet Muhammed ascending the mountain to hear the word of God – an image that is, of course, central to The Satanic Verses. The house itself is an ideal construction, a ‘rough triangular labyrinth’ with mirrors for windows (G. 224–5), overtopped by the ash tree Yggdrasil (re-transplanted from Joyce’s epic). Grimus has built it ‘to enshrine my favourite things’, especially birds: live birds, dead birds, ‘an audubon proliferation of feathered heads, some real, some imaginary’, centring on an image of ‘the Roc of Sinbad, the Phoenix of myth: Simurg himself’ (G. 229, 226). Alongside its function as a symbolic aviary, the house serves as a metaphor of Grimus’s dissociation from the world – again, much like the situation in Tennyson’s ‘Palace of Art’ (as Calf Island itself ‘where time stood still’ (G. 138) recalls the companion poem of withdrawal ‘The Lotus Eaters’); and the moral of both poems is played out in what follows. Grimus has decided he is complete in power and wisdom and has therefore chosen to die. But, as the ‘blink’ reminds us, the continuing existence of the island depends, moment by moment, on his conceptualizing; and therefore he can only die like the Phoenix, which ‘passes its selfhood on to its successors’ (G. 233), to be instantly reborn in another identity. And Flapping Eagle has been selected to play this role: ‘by shaping you to my grand design I remade you as completely as if you had been unmade clay’(G. 34 GRIMUS 233). Flapping Eagle now recalls the delirious psychic voyage through alternative selves from earlier in the novel, when he was assailed by ‘the memory of a man searching for a voice in which to speak’ (G. 236); this was the time of his wanderings (like the Wandering Jew Ahuserius), explained now as part of Grimus’s ‘grand design’. But, aided by the simple presence of Media (the fearful but faithful female), Flapping Eagle resists the nomination, making the central moral accusation against Grimus for what he has done to his world, to his kind – and to himself: The Stone Rose has warped you, Grimus; its knowledge has made you as twisted, as eaten away by power-lust, as its effect has stunted and deformed the lives of the people you brought here. . . . An infinity of continua, of possibilities both present and future, the freeplay of time itself, bent and shaped into a zoo for your personal enjoyment. (G. 236) Grimus alludes in the course of their conversation to his own past, one that includes wars, prison camps, torture, and execution – sufficiently emblematic of twentieth-century history; this is what he has turned aside from, as Flapping Eagle perceives, ‘away from the world, into books and philosophies and mythologies, until these became his realities . . . and the world was just an awful nightmare’ (G. 243). But even this is no excuse for abandoning his humanity. ‘You are so far removed from the pains and torments of the world you left and the world you made that you can even see death as an academic exercise’ (G. 236). As part of the prepared ritual of his death, Grimus (now ‘the ancient infant’, in an imagined process of continuous reversal that recalls Blake’s poem ‘The Mental Traveller’) and Flapping Eagle are fused into one identity. The passage is rendered in Rushdie’s most dense philosophic style: Self. My self. Myself and he alone. Myself and his self in the glowing bowl. Yes, it was like that. Myself and himself pouring out of ourselves into the glowing bowl. . . . My son. The mind of Grimus rushing to me. You are my son, I give you my life. I have become you, I have become you are me. . . .The mandarin monk released into me in an orgasm of thinking. . . . Like a beating of wings his self flying in. My son, my son, what father fathered a son like this, as I do in my sterility. (G. 242–3) One answer to Grimus’s rhetorical question might be Victor Frankenstein, who fathered his own ‘son’ in the sterility of his 35 SALMAN RUSHDIE scientific ambition. Immortality and sterility go together on Calf Island, and the perversion of the procreative process – Mary Shelley’s own nightmare theme – is part of Grimus’s dehumanizing programme. Assuming his new powers, Flapping Eagle travels to Thera, to be instructed by the Gorf, Dota (whose comments on Grimus’s abuse of the Rose puncture any excessive solemnity: ‘It is a flagrant distortion of Conceptual Technology to use the Rose to Conceptualize . . . coffee’ (G. 245) ). Grimus is brutally murdered by O’Toole’s gang (again as part of his own design), and his body burnt along with the symbolic ash tree and its complement of mythological birds. It remains to be seen how the new composite self of ‘I-Eagle’ will react. But, in the final moment of crisis, he maintains his resistance to the sterilizing, simplifying ideas of his mentor/maker: ‘The combined force of unlimited power, unlimited learning, and a rarefied, abstract attitude to life which exalted these two into the greatest goals of humanity, was a force I-Eagle could not bring himself to life’ (G. 251). He eliminates the Stone Rose (‘No, I-Eagle thought, the Rose is not the supreme gift’), and Calf Mountain unmakes itself, ‘its molecules and atoms breaking, dissolving, quietly vanishing into primal, unmade energy. The raw material of being was claiming its own’ (G. 251–3). And one of these primal energies is sexual. Significantly, the overthrow of Grimus is celebrated by the eventual coupling of Flapping Eagle and Media, the ‘orgasm of thinking’ replaced by sexual orgasm, our own ordinary (but also extraordinary) means of access to the other, to the future, and to our own true fulfilment: to all we know, and all we need to know on earth (perhaps) of transcendence. There is some doubt as to how one might interpret the end of the novel. The sexual solution with Media has a strongly positive note, as if his and her identity are salvaged in human terms. But we might equally understand that Flapping Eagle dissolves along with Calf Island itself as a result of his encounter with Grimus; as the price of his ‘human’ victory. (After all, we might risk the simple question: where would he have to go?) It is instructive to compare this ambiguous situation with the ‘dissolution’ of the narrator Saleem Sinai at the end of Midnight’s Children: is this a metaphor or is it a ‘real’ fictional death? The very terms in which one puts the question reveal that it makes no difference to the resolution 36 GRIMUS of the theme. But even here, one should note that the ‘relation’ between Grimus and Flapping Eagle is itself ambiguous. On the one hand, Grimus is the author of Eagle’s metamorphoses, his immortality, his access to an infinite number of alternative selves: like a beneficent creator. But, on the other hand, he has only put him through this ‘apprenticeship’ in order to prepare him for the assumption of Grimus’s own role, as the tyrant of being, the One, the Overmind (or over-artist). So the benefits of plural being are offset by the threat (the certainty) of the petrification of his humanity through the power of the Stone Rose. This makes Grimus the first of Rushdie’s allegorical representations of the recurrent opposition between the many and the one; and, clearly enough, a dress rehearsal for the more recognizable materials lined up against each other – inside each other – in The Satanic Verses. (There is even an elision of angel/devil to ponder on: G. 31.) Grimus is a secular Imam; Grimus’s frozen time is the equivalent of the ‘untime of the Imam’ in the later novel, the establishment of a fixed, sacral eternity over the flexibility and fallibility of human time. Grimus is a young man’s novel; it is ambitious, over-literary, philosophically overheated; a ‘novel of ideas’ in the doubtful sense that it is the ideas that run the show. It is in this sense that it may be considered ‘premature’. But it is also brilliant in its design and successful in many of its devices; and if the ideas run the show they are at least absorbing ideas.5 Rushdie himself did the novel a disservice by conceding in one early interview that it was ‘too clever for its own good’; better a book that is too clever than one that is not clever enough. Reviewing his fiction to date in a later interview, however, as a ‘body of work’, he is prepared to allow Grimus its proper place: ‘I also see my first novel . . . as part of this. Metaphysical concerns were present in a different way in the first novel.’6 It is not so much unfortunate as inappropriate, therefore, that some of Rushdie’s critics have chosen to denounce the novel gravely as a failure. Brennan’s schoolmasterly tone (‘this parable of crude acculturation’ . . . ’the stance of complacent philosophical scepticism’), and Catherine Cundy’s description of a ’chaotic fantasy with no immediately discernible arguments of any import’ both choose to ignore the novel’s essential humanism and high spirits.7 But the unprejudiced reader will stand a good chance of finding these out for him or herself. 37 3 Midnight’s Children One thousand and one, Rushdie reminds us halfway through Midnight’s Children, is ‘the number of night, of magic, of alternative realities’ (MC 212). And the novel is a modern odyssey, an epic navigation through these alternative realities: myth and history, memory and document, moonlight and daylight; the refractions of art, the centripetal and centrifugal dynamics of the self; the babel of languages, the alternating (and competing) religious and political understandings of the world. The challenge of Rushdie’s project is to create a fiction that does justice to these multiple realities, bringing them together in a way that allows each strand a voice, a presence, without obliterating the others. Saleem Sinai refers at one point to the ‘two threads’ of his narrative, ‘the thread that leads to the ghetto of the magicians; and the thread that tells the story of Nadir the rhymeless, verbless poet’ (MC 46), but, although these are indeed central strands, the weave is much richer and more various than this phrase would suggest. The basic narrative strategy is simple: the juxtaposition of the public and the private, the historical and the biographical – in what is, after all, a time-honoured technique, to be found in Plutarch, Shakespeare and Walter Scott as well as in Rushdie’s modern exemplars. And so the ‘birth-of-a-nation’ theme in the novel is parallelled by the strictly synchronized birth of the central character (and first-person narrator) Saleem Sinai, representative as he is of the 1,001 magical children supposed to have been born in that historical hour after the declaration of independence by Jarwhal Nehru at the midnight before 15 August 1947. (Rushdie has since calculated that, in demographical fact, at two births per second, around 7,000 children would actually have been born during this time; so his magical number 38 MIDNIGHT’S CHILDREN turns out to be ‘a little on the low side’ (IH 26).) And the mode of narration is (or appears to be) equally straightforward and well tried: Saleem tells his story to a simple woman, Padma, as they work together in the pickle factory that provides both a refuge for them at the end of the narrative and a metaphor for the fictional process itself. It is worth recalling, therefore, that the novel began as a third-person ‘omniscient’ narrative, and threatened to become engulfed in its materials until Rushdie hit upon the idea of the narrator/narratee, which had the effect of both lightening and focusing these same materials.1 It was a fortunate solution; as many readers have testified, it is the relationship between Padma and Saleem, made up of her interruptive comments and his evasions, that provides our point of entry into the novel, and sustains our interest through its many complications. (Although it should be said the relationship has been read more critically from a post-colonial standpoint, as exemplifying the patronizing exploitation of the indigenous working class by a condescending cosmopolitan author.)2 The relationship between the written and the spoken word is a matter of ancient debate, and one question that arises within it is how the novel can ever encompass orality: how much sense it makes for Sterne to claim, for example, that writing is ‘but a different name for conversation’.3 This has been the focus of much of the commentary on Midnight’s Children. But, whatever view we take of the evident artificiality of the conversation between Saleem and Padma, it does allow Rushdie to develop a narrative inflection which becomes characteristic – almost a signature – from this point on. This is a process we might call ‘tessellation’, after the way tiles are laid to overlap on a roof, whereby the narrative is always looping back in recapitulation, and also looking forward (‘proleptically’) in anticipation. The effect is to bring a depth of field to the present moment, creating an impression of simultaneity and temporal suspension – as the fluid present, the elusive now, is always pressed on by the past and foreshadowed, drawn forward into the future. Saleem describes himself at one point as writing at the apex of an isosceles triangle, where past and present meet (MC 191); but the projection into the future is also part of the fictional geometry. One wonders, indeed, whether this is one reason that the thirty chapters are not numbered – almost as if they could be 39 SALMAN RUSHDIE shuffled around and read in any order (as is the design of Julio Cortazar’s novel Hopscotch4) – so self-contained and interwoven is each of them, reproducing (like the genetic code) the essential information of the novel. Thus, perched in the middle of his novel at the ‘Alpha and Omega’ chapter [16], Saleem announces ‘my story’s half-way point’, looking both back and forwards: ‘there are beginnings here, and all manner of ends’ (MC 218). And, just as we have already visited the end of the story (‘It is morning at the pickle-factory; they have brought my son to see me . . . Someone speaks anxiously, trying to force her way into my story ahead of time’(MC 205) ), so when we approach the actual conclusion the earlier scenes are recycled. The first two pages of ‘A Wedding’ [chapter 28] are a good example; Saleem can explain to Padma his marriage to Parvati-the-Witch only by linking this back to the story of all the women in his life, beginning (again) in ‘a blind landowner’s house on the shores of a Kashmiri lake’, with Naseem Aziz his unmarried grandmother (MC 391–2). ‘Once upon a time’; ‘I have told this story before’ (MC 209, 212, 354); the phrases borrowed from oral narrative recur like a refrain through the novel, animating its texture. Let us return to the structure of juxtapositions. Saleem is born at midnight on 15 August 1947 – ‘at the precise instant of India’s arrival at independence, I tumbled forth into the world’ (MC 11) – and throughout the novel the threads are carefully crossstitched. In the chapter [14] ‘My Tenth Birthday’, ‘freak weather – storms, floods, hailstones from a cloudless sky – . . . managed to wreck the second Five Year Plan;’ – this on the very day Saleem founds ‘my very own M.C.C. . . . the new Midnight Children’s Conference’ (MC 202–3). He uses newspaper cuttings from the year 1960 to compose the fatal communication to Commander Sabarmati revealing his wife’s affair, and confesses to this as ‘my first attempt at rearranging history’ (MC 252–3). The underlying principle, or logic, is restated several times in the conversational ebb and flow of the address, but nowhere more explicitly than at the beginning of [chapter 17] ‘The Kolynos Kid’. Here Saleem offers to ‘amplify, in the manner and with the proper solemnity of a man of science, my claim to a place at the centre of things’ (MC 232). In a historical character the claim would be preposterous; for a fictional narrator it is a truism, a condition of his being at all. ‘I was linked to history both literally and 40 MIDNIGHT’S CHILDREN metaphorically, both actively and passively, in what our (admirably modern) scientists might term ‘‘modes of connection’’ composed of ‘‘dualistically-combined configurations’’ of the two pairs of opposed adverbs given above’ (MC 232). Without agreeing with his position (which is typically exclusive), one can see what Timothy Brennan means when he says that Rushdie is ‘best seen as a critic’ rather than as a novelist at all, since his novels are so uncompromisingly metafictional; they are not so much (he says) novels in themselves as ‘novels about Third-World novels’.5 But the irony of Saleem’s ‘claims’ need not have such a distancing or alienating effect. Indeed, this is how Rushdie conducts the delicate negotiation between fact and fiction in the novel, which has been well described by Andrzej Gasiorek: Midnight’s Children is . . . a double-voiced narrative in which a personal discourse of self-discovery interacts with, and is constrained by, a public discourse of history and politics. . . . [it] persistently admonishes those who either succumb to private fantasies about the world or distort it for political purposes. . . . Rushdie’s narrative mode does not seek to do away with the distinction between fantasy and reality but shows how strange and unstable was the political reality of the time.6 It is in these terms that we have to read the chapter [21] ‘Drainage and Desert’, as an elaborate but also ironic correspondence between Saleem’s own life story so far and the progress of the Indo-Chinese border war of 1962 (MC 286–7). Likewise, we are invited to believe that ‘the hidden purpose of the Indo-Pakistani war of 1965 was nothing more nor less than the elimination of my benighted family from the face of the earth’ (MC 327). Saleem is drawn to conflict: ‘the belligerent events of 1971’, the civil war in Pakistan, deliver him up as a guide in the Pakistani army; prompting his disappearance in to the Sundarbans and his reappearance seven months later into ‘the world of armies and dates’ (MC 356). India’s first nuclear explosion in May 1974 coincides pointedly with the return of the warlike Shiva (Saleem’s anti-self) into the narrative, while the painfully protracted labour of Parvati to deliver her child Aadam parallels the period of thirteen days in June 1975 between the returning of the guilty verdict on Mrs Gandhi and her seizure of emergency powers (MC 420–4). Saleem himself becomes a victim of the compulsory sterilization programme adopted 41 SALMAN RUSHDIE under these powers, providing a final metaphor for the expunging of the hope of the Indian people – ‘sperectomy’ – at the hands of certain Indian politicians. The problematic terms of the relationship between history and lived experience are deliberately brought into question by Rushdie through the factual errors introduced into the narrative – which may be understood as a kind of immunization, for the reader, against too uncritical a reading. Rushdie’s own essay ‘Unreliable Narration in Midnight’s Children’ considers this very question: how, ‘using memory as our tool . . . we remake the past to suit our present purposes’. His hero’s story is in this sense exemplary: ‘The reading of Saleem’s unreliable narration might be . . . a useful analogy for the way in which we all, every day, attempt to ‘‘read’’ the world’ (IH 24–5). In the novel itself he confesses that ‘re-reading my work, I have discovered an error in chronology. The assassination of Mahatma Gandhi occurs, in these pages, on the wrong date.’ And this cannot now be corrected: ‘in my India, Gandhi will continue to die at the wrong time’ (MC 164). Of course, in a sense the assassination will always have been ‘at the wrong time’, and the reader is expected to pick up on this; but the error prompts the narrator’s question: ‘Does one error invalidate the entire fabric? Am I so far gone, in my desperate need for meaning, that I’m prepared to distort everything – to rewrite the whole history of my times purely in order to place myself in a central role?’ (MC 164). It is left for the reader to judge – this is his right and his ‘responsibility’, to use the term from Keith Wilson’s essay.7 But the implicit answer is no, because there is always more to history than the facts. (‘Some legends make reality, and become more useful than the facts’ (MC 47).) We do have to ‘build reality’ from scraps of information (MC 412), and Midnight‘s Children is solidly built of facts and figures, dates and events, that are incontrovertible: from Amritsar, Bangladesh, and Bhopal to Queen Victoria, two world wars and General Zia. But the story we end up with will always be conditional, ‘open at both ends’. If ‘reality is question of perspective’ (MC 164) – an axiom that also galvanizes Gulliver’s Travels – then the perspective of a living observer (and participant) will always be changing, switching between the two poles of a supposedly subjective or ostensibly objective 42 MIDNIGHT’S CHILDREN standpoint. This, we should remember, is how the imagination works; and we have been warned against its capacity for error and distortion. The subjective view is unreliable for two reasons: owing to the fallibility of both our perceptions and our memories. Our perceptions to start with are subject to the moment-by-moment fluctuations of consciousness. Although Rushdie is not to be described as a psychological novelist in the manner of Joyce or Virginia Woolf, in that his own narrative point of view is typically epic and externalized (‘must we look’, asks Saleem, ‘beyond psychology’ (MC 143) ), he is nevertheless acutely aware of the unpredictability of our cognitive processes and the fragility of ‘the mind’s divisions between fantasy and reality’ (MC 165). We have seen how this was a central theme of Grimus, and it will provide a major preoccupation of The Satanic Verses; but (as the quotation just given indicates) it is a minor theme of Midnight’s Children as well. The macro-scale of history is always related back to the micro-scale of the individual. ‘Religion was the glue of Pakistan,’ we are told in [chapter 24] ‘The Buddha’, ‘holding the halves together’; and then the analogy is immediately made with consciousness: ‘just as consciousness, the awareness of oneself as a homogeneous entity in time, a blend of past and present, is the glue of personality, holding together our then and our now’ (MC 341). The historical epic scene must always contain the personal lyric self. The deposit of perception and experience in the memory introduces another variable, because the memory has its own transforming function: it ‘selects, eliminates, alters, exaggerates, minimizes, glorifies, and vilifies’, and in so doing it ‘creates its own reality, its heterogeneous but usually coherent version of events’ (MC 207). Coherent within its own terms, we may notice, rather than reliably correspondent to any external scheme of things; we might reasonably invoke the philosophers’ use of precisely these terms to describe alternative epistemological systems. It is worth noting, also, the closeness of this description of the memory to that Rushdie gives of the imagination in an essay quoted above, in Chapter 1 (p. 10). It is the powerful but unpredictable functioning of these faculties that makes us human beings, with all our dangerous potential for good and evil, rather than behavioural automata or cyberpets. The aggregation of these subjectivities on the demographic scale 43 SALMAN RUSHDIE introduces another level of unreality, beyond the memorial grasp of any individual. ‘Futility of statistics: during 1971, ten million refugees fled across the borders of East Pakistan– Bangladesh into India – but ten million (like all numbers larger than one thousand and one) refuses to be understood’ (MC 346). What Rushdie refers to elsewhere as ‘all this cold history’ (MC 186) means nothing unless warmed, brought to life, by the individual consciousness. The conclusion that is borne in upon us is that a history is put together, invented, by a people, just as a person is invented by circumstance (and as a character is invented in a novel). The creation of India itself, celebrated in the chapter [8] ‘Tick, Tock’, its coming into being at a designated moment in time, is a ‘mass fantasy’, a ‘new myth’, a ‘collective fiction’: because a nation which had never previously existed was about to win its freedom, catapulting us into a world which, although it had five thousand years of history, although it had invented the game of chess and traded with Middle Kingdom Egypt, was nevertheless quite imaginary; into a mythical land, a country which would never exist except by the efforts of a phenomenal collective will – except in a dream we all agreed to dream . . . (MC 111) And if we draw the focus back further, from historical time to mythical time, we achieve yet another dislocation in our perspective. Talking to Saleem’s grandfather Aadam Aziz, Tai the boatman claims ‘an antiquity so immense it defied numbering’; his ‘magical talk’ derives from ‘the most remote Himalayas of the past’: ‘I have watched the mountains being born; I have seen Emperors die’ (MC 16–17). The prehistorical Bombay of the fishermen is invoked ‘at the dawn of time . . . in this primeval world before clocktowers’ (MC 92). And even as Saleem recalls the moment of his birth, made so significant by its coincidence with that of his country, he then locates this moment in the ‘long time’ of Hindu myth to provide a vertiginous sense of ‘the dark backward and abysm of time’:8 Think of this: history, in my version, entered a new phase on August 15th, 1947 – but in another version, that inescapable date is no more than one fleeting instant in the Age of Darkness, Kali-Yuga . . . [which] began on Friday, February 18th, 3102 B.C; and will last a mere 432,000 years! Already feeling somewhat dwarfed, I should add nevertheless that the Age of Darkness is only the fourth phase of the 44 MIDNIGHT’S CHILDREN present Maha-Yuga cycle which is, in total, ten times as long; and when you consider that it takes a thousand Maha-Yugas to make just one Day of Brahma, you’ll see what I mean about proportion. (MC 191) Now: the ambivalent status of this ‘collective fantasy’ will obviously reflect on the ability of the artist (as well as the historian) to represent it. And this is where we can move on from an account of the parallel structure of Midnight’s Children to consider the nature of the fictional discourse itself. Interestingly (and – as is made clear from reading his later work – typically), Rushdie provides several surrogate portraits of the artist within the novel, each of whom contributes in some way to the metafictional level; that is, the commentary within the text on artistic problems and procedures. The first of these is Tai the boatman (who has been introduced above), a kind of Charon figure, also described as a ‘watery Caliban, rather too fond of cheap Kashmiri brandy’ (MC 16). Tai will not be taxed as to his real age, any more than Haroun’s father (later) will tell only true stories; that is not the point. And he is, of course, illiterate: ‘literature crumbled beneath the rage of his sweeping hand’ (MC 17). From his ‘magical words’ Aadam Aziz learns ‘the secrets of the lake’ (MC 18), and much else besides. A demotic Tiresias, Tai is as old as memory itself – the embodiment of the oral tradition, and the source of all storytelling. But where there is no claim, no provocation, there is no artistic hubris, no transgression; Tai is as innocent in this exchange as at his death (significantly, at the hands of partitionist fanatics). But we soon hear of a painter with more questionable aims, ‘whose paintings had grown larger and larger as he tried to get the whole of life into his art’ (MC 48) – and who commits suicide out of disappointment. Later on, Lifafa Das the peep-show man presents a similar case. He has his promotional patter: ‘ ‘‘Come see everything, come see everything, come see! Come see Delhi, come see India, come see’’ . . . ‘‘see the whole world, come see everything!’’ ’ Das reminds Saleem of Nadir Khan’s friend the painter, and he asks himself ‘is this an Indian disease, this urge to encapsulate the whole of reality? Worse: am I infected, too?’ (MC 73–5). His scriptwriter uncle Hanif provides another example, as he turns his back on myth and fantasy in favour of social realism. 45 SALMAN RUSHDIE ‘Sonny Jim,’ he informed me, ‘this damn country has been dreaming for five thousand years. It’s about time it started waking up.’ Hanif was fond of railing against princes and demons, gods and heroes, against, in fact, the entire iconography of the Bombay film; in the temple of illusions, he had become the high priest of reality . . . (MC 237) Hanif’s realism is no less questionable than any other representation; and there is an ironic self-reference in that Hanif’s latest script concerns ‘the Ordinary Life of a Pickle Factory’ (MC 236), guying the very metaphoric locus where Rushdie’s novel will end. Even Saleem’s old friend Picture Singh, the snake-charmer from the magicians’ ghetto, is humbled by a heckler’s gibe during his performance ‘which had questioned the hold on reality which was his greatest pride’ (MC 399). In each case, the artist here has tried to claim a franchise on reality which is untenable. The limitless ‘real’ may be enticed by the ‘true’, but it can never be contained by it. Tai the boatman would have known better. Saleem-as-author has himself confessed to these irreverent imaginings. He succumbs to the belief that ‘I was somehow creating a world’, where real people ‘acted at my command’: ‘which is to say, I had entered into the illusion of the artist, and thought of the multitudinous realities of the land as the raw unshaped material of my gift’ (MC 172). He does have some excuse for his ‘self-aggrandizement’ here, in that, ‘if I had not believed myself in control of the flooding multitudes, their massed identities would have annihilated mine.’ The fact that this is precisely what happens at the end of the novel establishes another self-reflexive commentary: the artist cannot, in the end, stand against either the tide or the dust of history. And so what are presented as Saleem’s ‘problems with reality’ (MC 421) approximate to Rushdie’s own. In the last chapter, as ‘an infinity of new endings clusters round my head’ – including Padma’s conventional happy ending – he has to resist the seductions of fantasy, of mere imagining. More insistent even than Padma, ‘reality is nagging at me’. And, because of his response to this, his thirty picklejar chapters preserve ‘the authentic taste of truth’ (MC 428, 444). The taste of truth: it is an interesting formula. A formula for fiction, where (as Saleem remarks earlier) ‘what’s real and what’s true aren’t necessarily the same’: ‘True, for me, was from my earliest days something hidden inside the 46 MIDNIGHT’S CHILDREN stories Mary Pereira told me’ (MC 79). We cannot ‘produce’ reality to order, but we can recognize the truth, in what is a complex act of moral and imaginative recognition. This is a truth which neither requires ‘evidence’, nor is undermined by the discourse of ‘magic realism’ into which the narrative frequently switches. This gives us blood that falls as rubies, tears as diamonds; and the whole chapter ([14] ‘My Tenth Birthday’) on the miraculous qualities of the midnight children themselves. ‘To anyone whose personal cast of mind is too inflexible to accept these facts, I have this to say: That’s how it was; there can be no retreat from the truth’ (MC 194). And this is in the end how the novel defends itself, and establishes its own integrity. Not by protestation: there can be ‘no proof’ of the fact that Naseem ‘eavesdropped on her daughters’ dreams’ (MC 56), nor of the sterilization of the midnight children: the evidence ‘went up in smoke’ (MC 424). Rushdie could repeat Sidney’s celebrated axiom: ‘for the poet, he nothing affirms, and therefore never lieth.’9 And in a sense he does so, when he claims that literature is ‘self-validating’ (IH 14); validated by what Wordsworth appealed to in his ‘Preface to the Lyrical Ballads’ as that ‘truth which is its own testimony’, the internal evidence of art itself.’10 And this ‘evidence’ is provided by the confidence with which, in Midnight’s Children, the different discourses are allowed to play alongside and against each other, the wonderful free-style of the narration – more cursive than coercive – that draws as it needs from a miscellany of styles and modes. It is this confidence that allows Rushdie to use the double-sided, reversible formula from oral tradition – ‘I was in the basket, but also not in the basket’ (MC 368) – which is more systematically invoked as the imaginative axis of The Satanic Verses, but plays its relevant part here. It is the formula that asserts nothing, that leaves everything suspended in the light wind of fictional hypothesis; that can build on sand, on water (like Dr Narlikar’s tetrapods), or maintain itself in the air. It is this confidence that gives Rushdie access to that fictive plenitude, that generosity of vision and prodigality of incarnation that is best described (in its generic aspect) by Mikhail Bakhtin, and by critics who operate on a Bakhtinian wavelength.11 The very metaphor of the ‘wavelength’ reminds us of a specially important means of access to fictive plenitude in the 47 SALMAN RUSHDIE novel: not just the radio itself, key though it is to the operation of the Midnight Children’s Conference, but telecommunications generally, both as instrument and image. The instrumentality of telecommunications is underlined by the narrator himself, as Saleem recommends his ‘future exegetes’ to consider the intervention of ‘a single unifying force. I refer to telecommunications. Telegrams, and after telegrams, telephones, were my undoing’ (MC 287). Not only Saleem’s undoing, we may add. The telephone plays a sinister part in many of Rushdie’s fictions: ‘squat at the ear of Eve, familiar toad’, in the Miltonic phrase, it replaces the serpent as the contemporary tempter, equivocator, and general conduit of evil. Edenic possibilities in both The Satanic Verses and The Moor’s Last Sigh are also destroyed by it. In Midnight’s Children it is over the telephone that Saleem’s mother gives away the secret of her meetings with ex-husband Nadir, and that Lila Sabarmati betrays her adulterous liaison – bringing about three deaths. The mass media play their part as well. Saleem’s birth is announced in the newspaper, and many of the historical events in the novel are brought to us over the radio. Disdaining old-fashioned omniscience, this narrator prefers to use more modern forms of mediation; a feature that adds to the plurality of voices through which the novel is articulated. And this exploitation of the media is on reflection unsurprising, when we think, for example, of how Marshall McLuhan welcomed them in the 1960s as ‘the extensions of man’, the elaboration of our very nervous system – bringing with them a new definition of consciousness. (The fact that McLuhan makes a parodic appearance in Grimus – as he did, in person, in Woody Allen’s film Annie Hall – underlines the convergence of ideas.) Dickens, we know, turned newspapers to good account in the middle of the previous century: what more refractions of his world might he not have offered us via radio and television? And it was Kipling, another celebrated journalist, who was one of the first to bring the modern media into fiction, with his stories ‘Mrs Bathhurst’ (where the plot centres on a fragment of remembered film) and ‘Wireless’ (on the quasi-mystical seductions of early, pre-regulation radio broadcasts).12 Does this represent another debt owed by Rushdie to those he has already acknowledged to the author of Kim? As the chapter [12] ‘AllIndia Radio’ explains, the telepathic radio also functions as the 48 MIDNIGHT’S CHILDREN main line of communication between the midnight children – with Saleem as the sensitive receiver. To begin with, the voices assail him as ‘a headful of gabbling tongues, like an untuned radio’, but he soon learns to use the new instrument: By sunrise, I had discovered that the voices could be controlled – I was a radio receiver, and could turn the volume down or up; I could select individual voices; I could even, by an effort of will, switch off my newly-discovered inner ear. It was astonishing how soon fear left me; by morning, I was thinking, ‘Man, this is better than All-lndia Radio, man; better than Radio Ceylon!’ (MC 161–2) He even goes so far, later, as to complain that he seems to be ‘stuck with this radio metaphor’ (MC 221); as indeed he is, until the untimely sinus operation deprives him of his special gift. But, as we might expect, in a verbal art form that aspires to the pictorial; that strains, as Joseph Conrad urged it should, to make us see, it is the visual media that offer themselves most readily for metaphoric elaboration. Early on, Saleem plays such variations on his ‘memory of a mildewed photograph’ of his father Aadam Aziz shaking hands with Mian Abdullah (the Hummingbird), with the formidable Rani of Cooch Naheen in the background. The photograph is not simply ‘described’; it is milked of its visuality to provide a soundtrack (‘there is a conversation going on in the photograph’), an interpretation of a key phase in Indian politics of the 1930s (‘Beyond the door, history calls’ (MC 45) ). Photography is used elsewhere; we meet a ‘Times of India staff photographer, who was full of sharp tales and scurrilous stories’ (MC 240), and it is an Eastman-Kodak portrait that provides ‘Picture Singh’ with his nickname (MC 368). But it is film that provides more dynamic images for the novel. It was not just for effect that Rushdie once claimed in an interview that the films of Buñuel had had more influence on him as a writer than the work of James Joyce; and it is the cinema above all that provides him with a reference point, an adaptable metaphor for the manipulation of point of view. This is how he describes his spying through the window on the meetings of his mother, Amina, and her one-time husband Nadir Khan in the Pioneer Cafe: ‘what I’m watching here on my dirty glass cinema-screen is, after all, an Indian movie . . . ’ (MC 212–13). And (in an often-quoted passage), the processes of 49 SALMAN RUSHDIE perception and retrospection themselves are interpreted via the cinema screen. Reality is a question of perspective; the further you get from the past, the more concrete and plausible it seems – but as you approach the present, it inevitably seems more and more incredible. Suppose yourself in a large cinema, sitting at first in the back row, and gradually moving up, row by row, until your nose is almost pressed against the screen. Gradually the stars’ faces dissolve into dancing grain; tiny details assume grotesque proportions; the illusion dissolves – or rather, it becomes clear that the illusion itself is reality . . . (MC 164) Rushdie quotes the passage in his essay ‘Imaginary Homelands’ to make the point that we cannot hope to see the present clearly, as a ‘whole picture’; there will be inevitable distortion (IH 13). One might remark here that there is an unhappy irony in the fact that Rushdie and other interested parties have encountered insuperable difficulties in attempting to bring this most filmable of novels to the screen. The governments of both India and Sri Lanka have refused to provide locations for the film, allegedly for fear of alienating Muslim communities. And as Rushdie has observed: you cannot construct Bombay in a studio.13 It is curious, in this connection, that Timothy Brennan chooses to take Rushdie to task for his use of the media, suggesting that this is another instance of ideological compromise, a sell-out to Western values – as defined by ‘the media and the market’. Rushdie is accused of ‘historicizing events without processing them . . . in the manner of the media’, and of responding to events according to ‘the way in which the news and media desensitise our response’. He is seen by this critic as being complicit in the process whereby ‘ ‘‘native’’ or local culture seems to be rendered meaningless by a communications network that effortlessly crosses borders and keeps an infinite stock of past artistic styles’; and – finally – as investing in that ‘crossbreeding of market and media’ which ‘produces an inhuman blob, as faceless as it is powerful.’14 Andrzej Gasiorek, by contrast, argues that Rushdie stands outside the frame of his media references, offering a critique of rather than a collaboration with their operations (which is surely the case: one has only to think of the savage satire of the news media in chapter [23] ‘How Saleem Achieved Purity’; the ‘divorce between news 50 MIDNIGHT’S CHILDREN and reality’, the ‘mirages and lies’ (MC 323-4) ); and Steven Connor goes so far as to propose that it is the interface of prose fiction with the electronic media which provides the very grain and substance/quality of Rushdie’s vision. ‘Rushdie exploits the forms and resources of the medium of radio, along with those of film and, in later novels . . . of television and video, because such forms are the evidence of a fundamentally new relationship between public and private life.’ If the realist novel, says Connor, explored the differentiation of public and private, ‘by contrast the forms of contemporary mass culture bring about a mutual permeation of the private and public, such that the integrity of both is dissolved and a relationship of difference is no longer possible between them’.15 This is McLuhan’s prophecy restated as cultural fact, and as such the observation offers a valuable comment on how Rushdie’s fiction actually works. But there is another important theme which we have touched on only glancingly so far, which requires further consideration at the end of this chapter. This is the theme of birth itself – announced in the very first sentence – which functions as the central metaphor of the novel, generating everything else. It is, after all, and axiomatically, through birth that newness enters the world; and it is through a complex and elaborated system of metaphors of birth and rebirth that Rushdie moves from merely physical propagation outwards to psychological, cultural, and political formations. It is also worth remarking that this is the most relevant context of his debt to Sterne, because it is the generative, obstetrical, and pediatric imagery in Tristram Shandy that provides a model for Rushdie’s own exploration of these ideas. A good deal of critical attention has been lavished on the theme of problematic parentage in Rushdie,16 which is understandable, since it recurs in all his novels and is (he himself reminds us) an important circumstance in both the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, the founding epics of India. But the fact of birth itself – what cannot occur, we remember, on Calf Island – is for Rushdie a much more powerful and pervasive idea, providing the ground for metaphors of rebirth also, which may actually be invested with greater symbolic power (as Robinson Crusoe’s rebirth onto his desert island, when he is delivered up by a wave from ‘deep in its own body’,17 is more eloquent than the bald birth announcement in the novel’s first sentence). 51 SALMAN RUSHDIE Midnight’s Children is unambiguously a nativity novel. It begins with Saleem Sinai’s own birth announcement, and ends not with a death (or even a marriage) but with the dissolution of that single citizen of India and his unique identity into the mass, the undifferentiated energies of the new and always renewable nation. Rushdie has commented on this ending: ‘The story of Saleem does indeed lead him to despair. But the story is told in a manner designed to echo, as closely as my abilities allowed, the Indian talent for non-stop regeneration’ (IH 16). The actual moment of Saleem’s birth, in the countdown chapter [8] ‘Tick, Tock’, is related as a lyrical counterpoint between Amina’s accelerating contractions and the birth of India itself: ‘The monster in the streets has already begun to celebrate; the new myth courses through its veins, replacing its blood with corpuscles of saffron and green’ (MC 114). It is significant that this scene and its attendant circumstances are revisited throughout the novel: Dr Narlikar’s Bombay Nursing Home is one of its key locations. Not the least reason for this, of course, is that it is here that Mary Pereira switches the two newborn boys, so that Saleem (who is actually the child of the serving-woman Vanita and the Englishman William Methwold) is brought up to a life of privilege by Shiva’s biological parents, Amina and Ahmed Sinai; meanwhile, Shiva becomes the street-bred criminal and militarist, Saleem’s ordained opposite.18 And there are also other births recorded: not only the ‘collective birth’ of the midnight children themselves, but the births of parents, siblings, cousins, children, in a kind of fertility ritual that serves to contradict the infamous sterilization programme of the ‘Green Witch’ Indira Gandhi, and to suggest the adoption of one sentence from the novel as its epigraph: ‘no new place is real until it has seen a birth’ (MC 102). One filament of the birth theme is taken up in the metaphor of the perforated sheet that appears at the end of the first chapter, where Dr Aziz is invited to examine his future wife through ‘a crude circle about seven inches in diameter’ cut in a sheet held by two women (MC 23). The hole in the sheet develops into a complex metaphor for our access via the perforated hymen to the place of conception and the avenue of birth, and eventually through life to death, via the last exit of the pyre or the tomb. But the sheet also suggests the circumscription of our perceptions themselves (as it functioned 52 MIDNIGHT’S CHILDREN literally for Dr Aziz); and the ‘pointillist’, accumulative process necessary to build these into a coherent vision and narrative. As such, it provides a central point (or gap?) of reference, to which Rushdie frequently recurs: as when his sister Jamila Singer performs in public behind a perforated veil (MC 304), or where Saleem’s grandmother appears to him, ‘staring down through the hole in a perforated cloud, waiting for my death so that she could weep a monsoon for forty days’ (MC 444). But it is possible to locate a more specific reference even to the moment of conception itself, lodged at the centre of the most mysterious chapter in Midnight’s Children: [25] ‘In the Sundarbans’. This chapter is in some respects the key to the novel, in that it homes in on the principle of transformability/metamorphosis – performing a function not unlike the visit to the Cave of Spleen in book IV of Pope’s Rape of the Lock: another Ovidian excursus from the social–historical plane. Rushdie made some very interesting comments on this section of the novel in his interview with John Haffenden: if you are going to write an epic, even a comic epic, you need a descent into hell. That chapter is the inferno chapter, so it was written to be different in texture from what was around it. Those were among my favourite ten or twelve pages to write, and I was amazed at how they divided people so extremely.19 In this chapter the man-dog Saleem (known at this stage as ‘Buddha’ because of his taciturnity) deserts from the Pakistani army into which he has been recruited as a tracker, along with the three young soldiers he is meant to be guiding, ‘into the historyless anonymity of rain-forests’ (MC 349), effectively deserting the historical surface of the fiction for another, atavistic plane: ‘an overdose of reality gave birth to a miasmic longing for flight into the safety of dreams.’ Not that dreams are necessarily safe places in Rushdie’s fiction, and indeed this amorphous world yields Saleem ‘both less and more . . . than he had expected’. Time falls away (‘hours or days or weeks’), scale becomes distorted (‘the jungle was gaining in size’), they surrender to ‘the logic of the jungle . . . the insanity of the jungle . . . the turbid, miasmic state of mind which the jungle induced’ (MC 350–l). The difference of texture has to do with the depth of reference in the passage. We are made to think not so 53 SALMAN RUSHDIE much of Swift’s disoriented Gulliver as of Conrad’s Marlow from Heart of Darkness (‘Going up that river was like travelling back to the earliest beginnings of the world . . . ’); perhaps of the characters in J. G. Ballard’s The Drowned World, driven back in their dreams to an archaic, antediluvian existence. 20 The soldiers’ project, ‘which had begun far away in the real world’, has acquired ‘in the altered light of the Sundarbans a quality of absurd fantasy which enabled them to dismiss it once and for all’. History has not forgotten them, in that they are haunted by the ghosts of those they have killed (‘each night [the forest] sent them new punishments’). And when they have done penance enough, they begin to regress towards infancy, before being brought again to themselves: ‘so it seemed that the magic jungle, having tormented them with their misdeeds, was leading them by the hand towards a new adulthood’ (MC 351–3). Saleem, however, has to undergo a more complex process of renewal, involving not only rebirth but ‘reconception’; and it is here that we have the last twist of the metaphor. ‘But finally the forest found a way through to him; one afternoon, when rain pounded down on the trees and boiled off them as steam, Ayooba Shaheed Farooq saw the buddha sitting under his tree while a blind, translucent serpent bit, and poured venom into, his heel’ (MC 353). Whereas Sterne’s Tristram Shandy begins with the actual conception of Tristram, Midnight’s Children appears not to include this detail (we focus exclusively on his birth). But what Rushdie has actually done, it seems, is to ‘delay’ Saleem’s real conception until this moment later in his life. The blind snakes of the Sundarbans are as it were spermatozoa; the bite in the heel (mythologically a vulnerable part) is the decisive moment where life takes hold. This provides an unusually complete, elaborated, and satisfying version of the metaphor of rebirth, which imitates ‘all the myriad complex processes that go to make a man’, linking him to the evolutionary chain of DNA as well as to his own personal history (‘I was rejoined to the past . . . ’). But Saleem, though reconceived, is not yet reborn; significantly, he cannot yet remember his birthright, his name. The dislocations of the magical journey continue, as the four move (again like Conrad’s Marlow) ‘ever further into the dense uncertainty of the jungle’ and come upon a ‘monumental Hindu temple’ appropriately decorated with ‘friezes of men and 54 MIDNIGHT’S CHILDREN women . . . coupling in postures of unsurpassable athleticism and . . . of highly comic absurdity’ (MC 354–5). The temple is a shrine to the ‘fecund and awful’ goddess Kali – a reminder that the Sundarbans episode functions first and foremost as an erotic fantasy; the descent into hell is also a recovery of our repressed, elemental selves. The rebirth motifs in this section prepare Saleem for his deliverance from Pakistan in Parvati’s basket and his return to India – where, as the narrative hurries self-consciously and precipitously towards its conclusion, the last five chapters feature the rise of Indira Gandhi’s Congress Party (with herself as the ‘Black Widow’, the wicked witch to balance Parvati); the symbolic destruction by Sanjay’s troops of the magicians’ ghetto, and the persecution and elimination of the children of midnight themselves in the grotesque episode of the vasectomists. This reflects the scandalous abuse of the mass sterilization programme of 1975, a genocidal crime against the Indian people that has had other reverberations in Rushdie’s work. The fulfilment of the symmetrical intention of the plot is reached when the unmanned Saleem marries his true midnight sister, Parvati-the-Witch, who is pregnant with Shiva’s child: thus ensuring that their son Aadam Sinai – the son to all three of them – is actually the true great-grandchild of the couple who glimpsed each other through the perforated sheet in the first chapter of the novel. Parvati is killed in the ghetto; her sickly child suffers in sympathy with ‘the larger, macrocosmic disease’, recovering after the emergency thanks to the ministrations of ‘a certain washerwoman, Durga by name, who had wet-nursed him through his sickness, giving him the daily benefit of her inexhaustibly colossal breasts’ (MC 408, 429). Shiva has played his destructive part in the suppression of the midnight children, provoking Saleem even to lie about his death; but, unlike the errors in the narrative (deliberate and unintentional), which stand their dubious ground, this lie is retracted (MC 425–7). And so Saleem can move towards his summation with a clear conscience. ‘Shiva and Saleem, victor and victim; understand our rivalry, and you will gain an understanding of the age in which you live. (The reverse of this statement is also true.)’ (MC 416–7). In fact both sets of terms are reversible here, which is presumably Rushdie’s intention – reminding us once again of the licence of fiction to 55 SALMAN RUSHDIE equivocate, to have it both ways. It remains only for Saleem to marry the strong-armed Padma, and for Rushdie/Saleem to leave us drowsed with the fume of the pickle factory where the fiction is being confected; surrendering himself, his multiple selves (it seems, willingly enough), to the numbers marching in millions, to the multitudinous identity of the new and always renewable nation. And surrendering his novel, it might be added, to the multiplicity of its possible readings. 56 4 Shame Published only two years after Midnight’s Children, which had enjoyed such extraordinary success, Rushdie’s third novel Shame brought disappointment. First to the reviewers, who were generally unenthusiastic; then to Rushdie himself, when it failed to win the Booker Prize that year. (The author’s public displeasure on this occasion was the beginning of a soured relationship with the ‘literary world’ – or, at least, its gossip columnists.1) Finally, it has to be said that Rushdie’s critics have tended to line up against the novel, treating it as the weak twin or dark shadow of Midnight’s Children. Timothy Brennan finds it ‘simply meaner, seedier, a bad joke’; Aijaz Ahmad ‘bleak and claustrophobic’, deformed by racism and sexism; Catherine Cundy ‘a model of closed construction’.2 Malise Ruthven suggested that ‘the whole novel recalls nothing so much as the crude drawings of Steve Bell, the British radical cartoonist’. James Harrison observes that ‘Midnight’s Children is a Hindu novel and Shame a Muslim one’, stressing the continuity but also the essential difference between them; an implicit judgement which is spelt out by Keith Booker, reflecting on ‘why Islam so often surfaces in Rushdie’s fiction as a symbol of monologic thought. Time and again, Rushdie emphasizes the fact that Islam is the religion of one God, a monotheism that forms a particularly striking symbol in the context of heteroglossic, polytheistic India.’3 Rushdie has protested that this is a misreading (‘it’s . . .wrong to see Midnight’s Children as the India book and Shame as the Pakistan book’), but the conclusion is hard to resist – especially when in the same interview quoted here he refers to the two novels in comparative terms: Shame is, he concedes, ‘nastier than Midnight’s Children, or at least the nastiness goes on in a more sustained way . . . it’s not written so affectionately . . . it’s a harder and darker book.’4 57 SALMAN RUSHDIE As has been suggested in Chapter 1, one of the recurrent problems in Shame is the instability of its fictional discourse, which in turn has something to do with the instability of Pakistan itself and Rushdie’s own ambivalent feelings towards it. What kind of book is this, about what kind of place, and inhabited by what kind of characters? These questions cannot be avoided because Rushdie raises them within the text, in a series of anecdotes which are relevant to the subject and genesis of the novel. The most important of these concerns the creation of Pakistan itself, the political entity and the name. It is well known that the term ‘Pakistan’, an acronym, was originally thought up in England by a group of Muslim intellectuals. P for the Punjabis, A for the Afghans, K for the Kashmiris, S for Sind and the ‘tan’, they say, for Baluchistan. . . . A palimpsest obscures what lies beneath. To build Pakistan it was necessary to cover up Indian history, to deny that Indian centuries lay just beneath the surface of Pakistani Standard Time. (S. 87) Unlike the creation of modern India, endorsed in all its miscellaneousness in Midnight’s Children, the creation of Pakistan is presented as an unnatural birth, ‘a duel between two layers of time, the obscured world forcing its way back through what-had-been-imposed’. The palimpsest peels and fragments; perhaps, Rushdie concludes, ‘the place was just insufficiently imagined . . . a miracle that went wrong’. The critical temptation is to respond that Rushdie’s novel of Pakistan is contaminated with the same failure of imagination: the layers of discourse peel, the fiction fails to cohere. It may be thought disconcerting, for example, that the Rushdie who understands ‘the importance of escaping from autobiography’5 should wander into the text in carpet slippers to tell us how he ‘returned home, to visit my parents and sisters and to show off my firstborn son’ (S. 26), and that he should derisively mimic the arguments of those native Pakistanis who would deny him a voice: ‘Poacher! Pirate! We reject your authority. We know you, with your foreign language wrapped around you like a flag: speaking about us in your forked tongue, what can you tell but lies?‘ (S. 28). These gestures have the effect of undermining Rushdie’s attempt to provide an imaginative location for his story. ‘The country in this story is not Pakistan, or not quite. There are two countries, real and fictional, occupying the same space, or 58 SHAME almost the same space. My story, my fictional country exist, like myself, at a slight angle to reality’ (S. 29). Rushdie has legitimately claimed, in an essay, that the only ‘frontiers’ in fiction are ‘neither political nor imaginative but linguistic’ (IH 69). It is unnerving, therefore, that he should describe himself at one moment as ‘inventing what never happened to me’ (S. 28), with all the confidence of fiction, and yet insisting at another that ‘I have not made this up’ (S. 241). The distinction becomes precarious when Rushdie switches to the discourse of the ‘realistic novel ’, inserting a two-page dossier of ‘real-life material’ from contemporary Pakistan (which includes details of a contested mark in ‘my youngest sister’s geography essay’), alongside incriminating evidence relating to state censorship, industrial production, Ayub Khan’s alleged Swiss bank account, and the execution of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto – whose fictional standin, Iskander Harappa, awaits the same fate later in the novel. Rushdie assures us at this point that he prefers the form of what he disingenuously calls his ‘modern fairy-tale’ because realism ‘can break a writer’s heart’ (S. 69–70); but this kind of prevarication can try a reader’s patience. On the same terms, one might also question the strategy of citing within the text a tragic anecdote from London (concerning a Pakistani father who killed his daughter for a sexual transgression) as the basis for his central character: ‘Sufiya Zenobia grew out of the corpse of that murdered girl.’ Rushdie readily confides to us the story of his story: All stories are haunted by the ghosts of the stories they might have been. Anna Muhammad haunts this book; I’ll never write about her now. And other phantoms are here as well, earlier and now ectoplasmic images connecting shame and violence. These ghosts, like Anna, inhabit a country that is entirely unghostly: no spectral ‘Peccavistan’, but Proper London. (S. 116–17) And predictably enough, two other instances from ‘Proper London’ follow – instances that might (as in a way they do) find their way more appropriately into The Satanic Verses. In the later novel, these fictional frames and postmodern juxtapositioning serve a larger and wonderfully realized aesthetic purpose. But the trouble with these passages (and others like them) in Shame is that the ribs of Rushdie’s intention show too uncomfortably through the structure. Some critics have tried to defend these 59 SALMAN RUSHDIE discordant elements with the argument that Rushdie is making a deliberate experiment in Shame with the ‘new journalism’ in the genre of the non-fiction novel;6 but the elements themselves remain too oddly assorted, miscellaneous, for the reader to be quite convinced. The uncertainty of tone identifiable here is reflected in the handling of the central narrative, concerning the rivalry of two dynastic families. Whereas Midnight’s Children had come to life with the discovery of Saleem’s first-person voice, Rushdie retreats to the third person in Shame. And he distances himself still further from the story he has to tell with the framing device of an observer (or voyeur) through whose perspective, and as it were involuntary participation, we gain access to the narrative. This is Omar Khayyam Shakil, the ‘peripheral’ hero of the novel, whom we meet in the first of the novel’s five sections, entitled ‘Escapes from the Mother Country’ – a phrase which relevantly runs together allusions to both birth and exile. In his role as marginal man, voyeur, ‘living at the edge of the world’, Omar is in some sense a surrogate for Rushdie as author (who has been described by Homi Bhabha as a writer ‘living at the edge of the Enlightenment’7); ‘at least he has a vivid imagination’, we are told, and he reads all the right books (S. 32–3). But Omar is fully realized as an independent and autonomous character, passive though he may be, and convincingly projected into the role of the recognizable Rushdie hero from the bizarre circumstances of his birth and upbringing. He is the child of three mothers, the formidable Shakil sisters, whose grasping father has died on the first page of the novel leaving them in doubtful control of their decaying fortunes. The shared pregnancy occurs after a scandalous party, leaving the identity of his mother as well as his father a mystery. (Rushdie resists allegorical readings, but, if we were to follow up the Methwold hint from Midnight’s Children, the father would be the departing Raj and the three mothers India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.) Omar is left free to wander the ramshackle Shakil mansion, Nishapur, itself a metaphor of postcolonial Pakistan; it is here that he acquaints himself with the long history of his birthplace, acquiring the essential, identifying information that Aadam Aziz had gained in the earlier novel from Tai the boatman: ‘he explored beyond history into what seemed the positively archaeological antiquity of ‘‘Nishapur’’. . . . On one 60 SHAME occasion he lost his way completely and ran wildly about like a time-traveller who has lost his magic capsule and fears he will never emerge from the disintegrating history of his race’ (S. 31). There are traces here, too, of Flapping Eagle’s radical disorientation in Grimus. But Omar’s main role is as vantage point, voyeur: as he confesses to himself at the end, during a dream of interrogation in the police cells, ‘I am a peripheral man. . . . Other persons have been the principal actors in my life-story; Hyder and Harappa, my leading men. Immigrant and native, Godly and profane, military and civilian. And several leading ladies. I watched from the wings, not knowing how to act’ (S. 283). For a moment he sounds almost like Jane Austen’s Fanny Price paralysed at Mansfield Park (‘I cannot act’8), the victim of others’ plots and her own diminished affectivity; and indeed this is his role, exercising no volition of his own but providing the moral dimension of other characters’ experience. The novel really begins (or begins again) with the second section, ‘The Duellists’, and the formal announcement in the first paragraph here (which reads like the exordium of an eighteenth-century novel) of key elements in the plot. This is a novel about Sufiya Zinobia, elder daughter of Raza Hyder and his wife Bilquis, about what happened between her father and Chairman Iskander Harappa, formerly Prime Minister, now defunct, and about her surprising marriage to a certain Omar Khayyam Shakil, physician, fat man, and for a time the intimate crony of that same Isky Harappa . . . (S. 59) The note of detachment, ironic demonstration, could not be more decisively sounded; and Rushdie is prepared to discharge the traditional responsibilities of dynastic fiction. We need a family tree (and the interlaced family tree is duly provided at the beginning of the novel). We have to be introduced to Sufiya’s mother, Bilquis, and Bilquis’s father, Mahmoud Kemal, who also runs an Empire: ‘the Empire Talkies, a fleapit of a picture theatre in the old quarter of the town.’ The town is Delhi; this is still India before Independence, and before ‘the famous moth-eaten partition that chopped up the old country and handed Al-Lah a few insect-nibbled slices of it’ (S. 60–1). But fathers are quickly dispatched in this novel, as we have already observed from the 61 SALMAN RUSHDIE sudden departure of Mr Shakil – part of Rushdie’s design being to illustrate the way women are the victims of masculine ambition, lust, fanaticism, cruelty, and incompetence. And so Mahmoud is killed by a bomb that destroys his cinema when he tries to show films that cross the religious divide – ‘even going to the pictures had become a political act’ (S. 61): a bomb that also lights a fuse, anticipating the novel’s apocalyptic ending. Bilquis wanders dazed and naked in the streets, providing one of Rushdie’s most memorable images of the dislocated and dispossessed: O Bilquis. Naked and eyebrowless beneath the golden knight. . . . All migrants leave their pasts behind, although some try to pack it into bundles and boxes – but on the journey something seeps out of the treasured mementoes and old photographs, until even their owners fail to recognize them, because it is the fate of migrants to be stripped of history, to stand naked amidst the scorn of strangers upon whom they see the rich clothing, the brocades of continuity and the eyebrows of belonging. (S. 63–4) Bilquis is rescued by Raza Hyder, and her marriage introduces her to the dynastic Hyder family, with the bizarre mating rituals and complex social interaction described in chapter 5, ‘The Wrong Miracle’; and also to the family stories, ‘because the stories, such stories, were the glue that held the clan together, binding the generations in webs of whispered secrets’. It also projects her into the story, ‘the juiciest and goriest of all the juicygory sagas’, in which like it or not she has to play her part (S. 76–7). Bilquis’s part is to give birth to Sufiya Zinobia, herself the ‘wrong miracle’, in that she is a daughter rather than Raza’s expected son; and as such she is destined to serve as an image of Pakistan itself, which has been described a few pages earlier as ‘the miracle that went wrong’ (S. 89, 87). Sufiya’s birth has been preceded by the symbolic stillbirth of a son, who was strangled by the umbilical cord in the womb; a son whose ghostly unhappened life, jointly fantasized by the parents, ironically suggests an alternative and (who knows) happier history for Pakistan. The stillborn son may also be seen as part of the system of imaginative insufficiency alluded to above: the people of new Pakistan ‘had been given a bad shock by independence, by being told to think of themselves, as well as the country itself, as new. Well, their imaginations simply weren’t up to the job.’ 62 SHAME ‘History was old and rusted’ (S. 81–2), and even Raza Hyder is unable to move it. The narrator of Midnight’s Children confessed to a weakness for symmetry, that obtrusive patterning of events that is characteristic of the comic vision; and this quality is equally foregrounded in the black comedy of Shame. Timothy Brennan draws attention to the no doubt ironic repetition of the mystical number three in the structure: three mothers, three families, three countries, three religions, three capitals.9 The ‘duellists’ themselves, Raza and Iskander, are ushered into battle (first, over a woman) on the same page that sees Bilquis and Rani consigned to their parallel fates: ‘Meanwhile, two wives are abandoned in their separate exiles, each with a daughter who should have been a son’ (S. 104). Iskander’s wife Rani has given birth to Arjumand, whose fiercely denied femaleness will earn her the nickname ‘the Virgin Ironpants’. (As we shall see, Rani’s other function is to weave her allegorical shawls.) Meanwhile, Sufiya has been stricken with a brain disease that dislocates her time sense, further underlining her association with a Pakistan progressively unable (or unwilling) to take its place in history. Two months after Raza Hyder departed into the wilderness to do battle with the gas-field dacoits, his only child Sufiya Zinobia contracted a case of brain fever that turned her into an idiot. . . . Despairing of military and civilian doctors [Bilquis] turned to a local Hakim who prepared an expensive liquid distilled from cactus roots, ivory dust and parrot feathers, which saved the girl’s life but which (as the medicine man had warned) had the effect of slowing her down for the rest of her years, because the side-effect of a potion so filled with the elements of longevity was to retard the progress of time inside the body of anyone to whom it was given. (S. 100) Dislocation from historical time features in all Rushdie’s fictions, from Grimus to The Moor’s Last Sigh, and in each case it is a curse, an unwelcome distinction that deprives the afflicted person of the possibility of interacting with others. Here, as later in The Satanic Verses, it also symbolizes the ideological war on history, on (Western) time, conducted by militarized Islamic absolutism, invoking for its own purposes the incontrovertible and claustrophobic simultaneity of the Koran. In section III (‘Shame, Good News and the Virgin’) the duellists are brought closer to the crisis of their confrontation. 63 SALMAN RUSHDIE Isky Harappa abandons the hedonistic life he has shared with Omar Shakil and takes a new mistress, history, as part of a ‘process of remaking himself’ that leads to his becoming Prime Minister (S. 125, 172); while Raza Hyder frets in his shadow, conscious of Harappa’s greater political astuteness. But, if the comic perspective Rushdie imposes on his materials requires symmetry, symmetry also requires weddings, and the families are further (dis)united by the failure of the proposed alliance between Isky’s nephew Haroun Harappa and Ryder’s younger daughter Naveed – who ditches Haroun in preference for a polo-playing policeman the day before the ceremony; which is nevertheless carried out, to everyone’s consternation, with the substitute groom. This passage (S. 162–72) is one of the comic triumphs of the novel; including the shocking scene where Sufiya, overcome by shame, a ‘pouring-in to her too-sensitive spirit of the great abundance of shame in that tormented tent’, physically attacks her sister’s new husband, burying her teeth in his neck. Ryder’s unexpected son-in-law Tulvar Ulhaq does turn out to have his uses, however, as his magic-realist clairvoyancy enables him to detect crimes even before they are committed. Meanwhile the disreputable but indispensable hero Omar has also ‘fallen for his destiny’ by marrying the afflicted daughter Sufiya, whom he has treated in his profession as a doctor during one of her seizures. These take the form of her succumbing (as at her sister’s wedding) to a ‘plague of shame’, and it is her embodiment of the moral theme of the novel, the scarcely translatable sharam, that identifies her as a secular saint. It is this role that provides the mysterious centre of the novel, her encounter with evil that leaves the limiting paradigms of the ‘new journalism’ behind. ‘What is a saint?’ the novel asks us, proposing the answer: ‘A saint is a person who suffers in our stead’ (S. 141). And even the bemused Raza perceives ‘a kind of symmetry here’ (S. 161). The third section concludes with a summary of the action so far. ‘Once upon a time there were two families, their destinies inseparable even by death’ (S. 173); the note of tragic fate is deliberately sounded. But, as is often the case in drama – in Greek drama, and in Shakespeare – despite the men’s fantastic political tricks before high heaven it is the female roles that somehow come to typify this fate. Here, the recurring contrast 64 SHAME between the two Hyder sisters Sufiya and Naveed (‘What contrasts in these girls!’ (S. 137) ) and the two sequestered wives Bilquis Hyder and Rani Harappa assumes greater significance. As Rushdie observes: I had thought, before l began, that what l had on my hands was an almost excessively masculine tale, a saga of sexual rivalry, ambition, power, patronage, betrayal, death, revenge. But the women seem to have taken over; they marched in from the peripheries of the story to demand the inclusion of their own tragedies, histories, and comedies, obliging me to couch my narrative in all manner of sinuous complexities, to see my ‘male’ plot refracted, so to speak, through the prisms of its reverse and ‘female’ side. It occurs to me that the women knew precisely what they were up to – that their stories explain, and even subsume, the men’s. (S. 173) Not only is this the clearest insight into Rushdie’s handling of gender politics in the novel;10 the comment is significant, also, as it reflects on Rushdie’s conscious deployment of different genres. Does one not catch an echo, in this parodic formal categorizing, of Polonius’ pedantic recommendation of the players in Hamlet? If so, it is entirely appropriate, given the theatrical denouement that is in preparation, with its references to this play. The fourth and longest section of Shame (‘In the Fifteenth Century’, with allusion to the Hegiran calendar) takes us further into the fantastic politics of this fantasy Pakistan. And each of its four chapters is fantastic in a different way. The first (ironically titled ‘Alexander the Great’) provides a deliberately de-synchronized history of Isky Harappa’s years in power, partly through low-voltage gossip and media refraction but mainly through the highly charged and contradictory recollections of his daughter, Arjumand, and his wife Rani – which show that ‘no two sets of memories ever match, even when their subject is the same’ (S. 191). Arjumand’s self-imposed function is to sanctify her father’s memory, ‘to transmute the preserved fragments of the past into the gold of myth’ (S. 181). But Rani assumes a more sibylline role. Her eighteen embroidered shawls are a central metaphor in the novel (and anticipate, incidentally, the analogous device of Aurora Zogoiby’s paintings in The Moor’s Last Sigh). Not only do they provide, in four pages (S. 191–5), a terrifying, telescoped account of corruption and 65 SALMAN RUSHDIE cruelty, an object lesson in the perversions of power; they also remind us that it is the female vision that has understood and registered this. The badminton shawl, the slapping shawl, the kicking shawl, the hissing shawl; ‘in silver thread she revealed the arachnid terror of those days’. The torture shawl, the obliterating white shawl, the swearing shawl; the shawls of international shame and the election shawls, culminating in the ‘carnage’ of the seventeenth shawl, the shawl of hell, and the final unsparing shawl depicting the murder of Little Mir Harappa: ‘she had delineated his body with an accuracy that stopped the heart.’ It is not only (as the narrator concedes) that women have taken over the plot; the moral and imaginative vision of Shame is articulated from a female standpoint. This is another reason, perhaps, why the awkward formal gestures referred to earlier seem so inappropriate. The second chapter returns to Sufiya Zinobia, and her operations as ‘one of those supernatural beings, those exterminating or avenging angels, or werewolves, or vampires, about whom we are happy to read in stories’ (S. 197). The inventory of styles is more productive than the abstract gesticulations of form. Rushdie has confirmed that Stevenson’s paradigmatic Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde lie behind the complementary conceptions of the doctor Omar Shakil and Raza Hyder; but the beast Hyde also inhabits the retarded Sufiya, as an image both of her saintly scapegoat ’shame’ and also the correlative sexual violence in which it issues. Like other writers who have meditated on the consequences in daily life of the brutal events and revolutions of our times (one thinks of the poetry of Tony Harrison, who wrote The Blasphemers’ Banquet in solidarity with Rushdie in 1989), Rushdie has made it clear that he sees an intimate connection between public life and sexual behaviour – especially in the context of Shame: ‘the book is set in Pakistan and it deals, centrally, with the way in which the sexual repressions of that country are connected to the political repressions.’11 There is an excellent, moving passage in this chapter that presents the uncomprehending consciousness of an innocent: There is a thing called the world that makes a hollow noise when you knock your knuckles on it or sometimes it’s flat and divided up in books. She knows it is really a picture of a much bigger place called everywhere but it isn’t a good picture because she can’t see herself in 66 SHAME it, even with a magnifying glass. She puts a much better world into her head, she can see everyone she wants to there. . . .There is a thing that women do at night with their husbands. She does not do it, Shahbanou does it for her. I hate fish. . . . But she is a wife. She has a husband. She can’t work this out. The horrible thing and the horrible not-doing-the-thing. She squeezes her eyelids shut with her fingers and makes the babies play. There is no ocean but there is a feeling of sinking. It makes her sick. There is an ocean. She feels its tide. And, somewhere in its depths, a Beast, stirring. (S. 213–5) The use of a restricted consciousness for the paradoxical purpose of clarification is a strategy often used by the postcolonial writer, a technique of altered perspective and estrangement that looks back to Swift. The passage quoted establishes Sufiya in this role, in that what she cannot work out forces us to reflect and reconsider our own assumptions about the domestication of the beast. It is followed shortly afterwards by a chilling account of the sexual murders of four young men, for which the possessed Sufiya is responsible: ‘the Beast bursting forth to wreak its havoc on the world’ (S. 219). She too is the reversible victor/victim: as it were, the lust-crazed Yahoo girl from Gulliver ’s Travels as well as the flayed woman from the ‘Digression on Madness’ in A Tale of a Tub.12 As the receptacle of their shame, Sufiya becomes also ‘the collective fantasy of a stifled people, a dream born of their rage’ (S. 263); she too carries her dead brother within her, and the lost hope he represented. But the preordained plot of history drives the male plot of the novel, and the chapter on the fall of Harappa at Hyder’s hands returns us to the problem of the fictional discourse in Shame, discussed above. On the one hand, we have the powerful image of Iskander in the death cell, ‘death’s baby’, with the noose tightening around his neck a clear reference back to his strangled son: ‘Yes, I am being unmade’ (S. 231). It is the full reversal of the birth motif in Midnight’s Children; and here the fiction maintains its own imaginative parabola. But then Rushdie grasps again at the handrails of history in order to ‘verify’ his story. Of the trial of Harappa we are told: ‘All this is on the record’, ‘All this is well known’; baldly, even the proverbial ‘facts are facts’ (S. 228, 231, 233). Even if it could be argued that the last of these asseverations is ironic, it certainly confuses the reader to have different criteria 67 SALMAN RUSHDIE of ‘truth’ applied as it were simultaneously – as if Rushdie were somehow reinsuring his fiction with documentary evidence. There is a danger of our finding ourselves in that dubious fictional space where, as Henry James remarked, details have ceased to be things of fact and yet not become things of truth.13 This fatal hesitation also affects the last chapter of section IV (‘Stability’), which follows the establishment of Hyder’s fundamentalist power. It begins with a two-page discussion of a performance in London of Buchner’s play Danton’s Death, and the implications of the drama for Pakistani politics (S. 240–2). Then there is a distinctly awkward intervention on the new fundamentalism, which is introduced with an apology (‘May I interpose a few words here on the subject of the Islamic revival? It won’t take long’), and then pursued in an uncompromisingly journalistic manner: ‘So-called Islamic ‘‘fundamentalism’’ does not spring, in Pakistan, from the people. It is imposed on them from above’ (S. 250–1). Such lapses of judgement recall Timothy Brennan’s not unreasonable comment, that Rushdie’s journalism lacks the ‘bipartisan’ dimension of his fiction;14 furthermore, the two categories certainly seem to trip over each other here. Alternative fictions may happily coexist, but competing truth claims tend to cancel each other out. Within this chapter, nevertheless, the novel is concentrating its imaginative energies in preparation for the fifth and last section ‘Judgment Day’ – which, significantly, allows no authorial intervention to diffuse the gathering conviction of its climax. Omar has a vision of the ‘two selves’ of his wife, Sufiya, a familiar Rushdie trope, and begins to recognize (and to fear) the ‘smouldering fire of the Beast’ which he recognizes in her (S. 235). When she escapes the confinement of her husband and father to begin a reign of terror as the white panther, Omar asks himself whether ‘human beings are capable of discovering their nobility in their savagery’ (S. 254), and the ghost of Iskander suggests to him that his daughter has become a natural force, like a river in flood, that will destroy our human constructions, whether physical or imaginative: ‘everything yields to its fury . . . no dykes or barriers have been made to hold her’ (S. 256). It is not surprising that Rushdie has confessed that he became afraid of his own creation in Sufiya; what she meant, how she fitted into the accelerating vision of ‘the nature of evil’.15 68 SHAME The last section is played out at this high pitch: back where the novel began, at Nishapur on the altar of the high hills of the city of Q, and in sight of the Impossible Mountains. (Responsiveness to the moral geography of the subcontinent was something Rushdie learnt from Kipling, and the last stages of the journey of Kim and his lama are surely not forgotten here.) Judgement is to fall on Raza Hyder, brought to their house by Omar to be impaled on the blades of the Shakil sisters’ lethal contraption, constructed in earlier years – the curiously apposite ‘dumb waiter’ that works like an Iron Maiden. Raza’s wife, Bilquis, dies of a fever, and eventually Omar gives himself up, a willing sacrifice, to the retributive fury of the Beast. But before this apotheosis it is he who must conduct the epilogue, as he featured in the prologue to the novel. It is he who negotiates the dizzying levels of reality that press in at the end, within the old house that is alternately shrinking and expanding, unsure in his own fever ‘whether things were happening or not’ (S. 273–5); there are shades of the Sundarbans here. It is he who is given access to a vision of the future (as at the end of each cycle of Shakespeare’s history plays), ‘of what would happen after the end . . . arrests, retribution, trials, hangings, blood, a new cycle of shamelessness and shame’ (S. 276–7). And it is Omar who finally understands and interiorizes this shame, sharing in full consciousness the symbolic possession of his wife. ‘The Beast has many faces. It can take any shape it chooses. He felt it crawl into his belly and begin to feed’ (S. 279). Omar becomes, one might even suggest, a kind of Hamlet, ‘crawling between heaven and earth’, consumed by the end with self-disgust at what is rotten in the state of Peccavistan. This suggestion is reinforced by Omar’s sense of the ‘gaping mouth of the void’, of the ‘supernatural frontier’ he is approaching (S. 268), and also by his mothers’ retelling of a shameful family secret, ‘the worst tale in history’, involving a fratricidal sexual betrayal: ‘this is a family in which brothers have done the worst of things to brothers’. In Chunni’s perverse taunt to Omar, concerning his paternity, we can even hear a clear echo of Hamlet’s reproach to his mother. Omar is told, ‘Your brother’s father was an archangel. . . . But you, your maker was a devil out of hell’ (S. 277–8). On first arriving back at Nishapur Omar perceived that his mothers had set up what is described as a ‘demented theatre’ for 69 SALMAN RUSHDIE the novel’s last scene, and so these dramatic parallels are perhaps authorized – continuing a pattern of Shakespearian intertext that becomes a more pronounced feature in Rushdie’s later novels. The three sisters themselves, called hags and witches by Raza, are clearly kin to the Weird Sisters, as Raza himself is a version of the usurping Macbeth. But the last scene belongs emphatically to fiction, where ‘all the stories ha[ve] to end together’, since ‘the power of the Beast of shame cannot be held for long within any one frame of flesh and blood’. And the stories do end together, after Omar has surrendered to the terrible, murderous embrace of his inspired wife, in an explosion that begins in the house, starting a fireball ‘rolling outwards to the horizon like the sea’, becoming a silent cloud, a cloud ‘in the shape of a giant, grey, and headless man’ (S. 286): a cloud much like the apocalyptic nuclear cloud that casts its shadow more than once in Rushdie’s novels. The rest was silence, for the next five years at least, while Rushdie was working on his own explosive device: The Satanic Verses. 70 5 The Satanic Verses The Satanic Verses is a novel bristling with difficulty. This is due not so much to the cloud of controversy that has settled over it, as to the complexity of the novel itself, which makes the most disinterested reading a challenge. This complexity is no mere provocative, postmodernist ‘top dressing’ but arises from the nature and intensity of the metaphysical speculation that lies at the heart of the work. There is a dense, nuclear fusion of ideas, grouped around the nature of modern identity, personal and national/ethnic; the relationship between our instinct for good and evil; the implications of this for our understanding of human disposition and potentialities; the nature of the ‘reality’ within which we are required to live out our lives. These ideas are galvanized by what may even be described as a dangerous experiment with the limits of imagination, which involves testing to destruction the coherences we ordinarily rely upon, via discontinuity, dream, fantasy, and psychosis; and exploring – by living through it – the nature and authority of ‘inspiration’, including religious revelation. But let us remember, as Rushdie himself and some of his more perceptive critics have reminded us, that despite the seriousness of these preoccupations, we are dealing with a novel – even, a comic novel – which, while it engages with other ideological discourses, does so (or at least attempts to do so) on its own terms. Rushdie presented his own formal defence in the essay ‘In Good Faith’ (1990: IH 393–414), and the position outlined here has been supported by many other novelists and critics.1 One of the difficulties has to do with the extreme formal complexity generated by Rushdie’s fictional scheme. As he conceded in a newspaper interview that coincided with the publication of the novel in September 1988: 71 SALMAN RUSHDIE The Satanic Verses is very big. There are certain kinds of architecture that are dispensed with. Midnight’s Children had history as a scaffolding on which to hang the book; this one doesn’t. And since it’s so much about transformation I wanted to write it in such a way that the book itself was metamorphosing all the time. Obviously the danger is that the book falls apart.2 Well: the book has ‘fallen apart’ in one sense, or been torn apart, dismembered by faction and misrepresentation, from which it can hardly recover. But Rushdie put his ‘big’ novel together with ingenuity as well as creative energy. The structure and the writing of the Verses are as intricate as the conception is complex, and we should begin by trying to describe how the fiction is used to articulate and illuminate the governing ideas. Engaging at the most summary level, we could say that the novel is about two friends, their intense, often antagonistic relationship with each other, with their sexual partners, and with the society around them – which is subjected to radical criticism. In the end, one of them commits suicide, while the other survives with a degree of salvaged optimism and a new perspective on love. This description as it happens also fits Lawrence’s Women in Love – a novel to which The Satanic Verses does indeed have intriguing resemblances, not least in the nature of the disintegration against which the characters are forced to struggle in order to survive, and the disconcerting ‘doubleness’ and reversibility of the discourse. But this comparison also highlights the uniqueness of Rushdie’s novel, which, however many allusions, references, and parallels may be found within it, cannot be reduced to the sum of its influences. No more than can Joyce’s Ulysses. These influences include, it must be said, the Bible and the Koran, the Indian epics, Sufi texts, Virgil, Dante, Shakespeare, Blake, Dickens, Bulgakov, Beckett – and of course Joyce himself. Not to mention the cinematic tradition of three continents, and a representative swathe of contemporary (that is to say, 1980s) British, Indian, and other cultures. One needs to ‘home in’ on the specificity of Rushdie’s text, and the specific strategies and solutions he has employed to deliver it. The two friends, Gibreel Farishta and Saladin Chamcha, are (specifically) Indians; more specifically, they are living (most of the time) in modern Britain; more specifically still, they are media people (one in film, one in radio); and most specifically of 72 THE SATANIC VERSES all, they have arrived in Britain as the miraculous survivors of an Air India jet bombed by terrorists high over London. We are introduced to them, on the first page, literally ‘flying’ to earth. This is not realist discourse – though what are later called ‘the polluted waters of the real’ (SV 309) flow freely enough through the novel. As in Auden’s poem ‘Musée des Beaux Arts’, we have seen ‘something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky’; and the fiction that follows will more than maintain that extraordinary trajectory. What happens is that the two ‘fall’ not only literally into a decaying Britain but also by the novelist’s sleight of hand into each other; and with the help of his well-practised timetravelling gifts into several parallel narratives: unravelling in contemporary London, seventh-century Arabia, twentieth-century Pakistan; diversified with excursions to Buenos Aires and Bombay, memories of the voyages of Vasco da Gama, the execution of Charles I, and the Battle of Hastings. We learn through flashback of the film career of Gibreel Farishta (cinema itself serving again as the modern metamorphic form par excellence), and the loss of faith that brings ‘a terrible isolation’ upon him; the tragic end of one affair (in the death of Rekha Merchant) and the beginning of another (with a symbolic woman mountaineer named Alleluia Cone). Simultaneously – and simultaneity is one of the novel’s jewelled levers – we are told of the English education and marriage of Saladin Chamcha, and his success as a radio ‘voice’: ‘he ruled the airwaves of Britain’ (SV 60). All this helps him to achieve his denial of Bombay, represented by his ageing father and his one-time mistress Zeeny Vakil – who speaks up, appositely enough, in protest at such perverse ‘purity’, for ‘the eclectic, hybridized nature of the Indian artistic tradition’ (SV 70). But, since section II delivers the unsuspecting reader along with Gibreel himself into the Arabian desert in the seventh century, we need at this point to address the structure of the novel, in its nine sections, and Gibreel’s role as ‘time traveller’ (and something more) between them. It has been observed3 that this novel about disintegration and reintegration is itself divided via its odd-and-even-numbered sections. The first four of the ‘odd’ sections, I to VII (which take up much the longer part, some 400 of the novel’s 547 pages), take place in London, while the last, IX, is set in Bombay. The four ‘even’ sections (each, 73 SALMAN RUSHDIE curiously, 38 pages) contain the magical or dream material. Section II (‘Mahound’) tells the story of the original revelation to the prophet (including the notorious episode of the ‘satanic verses’ themselves); section IV, (‘Ayesha’) begins with a brief encounter with a sinister Imam who resembles Khomeini in exile, before moving on to the story of the girl Ayesha, who lives on butterflies and proposes a pilgrimage from Pakistan to Mecca (simply walking into the sea); section Vl (‘Return to Jahilia’) relates the story of the establishment of Islam itself, and the power-broking that goes on in the interests of the ‘Idea’; while section VIII, (‘The Parting of the Arabian Sea’) recapitulates the outcome of Ayesha’s pilgrimage. The key structural (and psychological) feature is that it is Gibreel, as archangel – specifically, angel of the recitation, he who dictates the word of God to the prophet – who ‘dreams’ the other, magical narratives. And the handling of the interface between the ‘two’ texts, two levels of reality, is the supreme test of Rushdie’s skill as a narrator. These ‘serial dreams’ begin when Gibreel and Saladin are held hostage in the hijacked aircraft (for a symmetrical 111 days), ‘marooned on a shining runway around which there crashed the quiet sand-waves of the desert’ (SV 77). Gibreel was sweating from fear: ‘ . . . every time I go to sleep the dream starts up from where it stopped. Same dream in the same place. As if somebody just paused the video while I went out of the room. Or, or. As if he’s the guy who’s awake and this is the bloody nightmare. His bloody dream: us. Here. All of it.’ (SV 83) As if to confirm that reading can be dangerous, these dreams begin after Gibreel has been reading a creationist pamphlet given to him by a crank about ‘a supreme entity controlling all creation’ (SV 81–2). The strategy of the dream is revealed where Gibreel dreams the Fall (‘Shaitan cast down from the sky’), dreams dreaming: ‘Sometimes when he sleeps Gibreel becomes aware, without the dream, of himself sleeping, of himself dreaming his own awareness of his dream’ (SV 91–2). This is where for him ‘panic begins’, the fear of insanity, as he is forced to question the ground of his own being; but where for us as readers the fun begins, the intriguing play of levels, the skilful and subtle framing of successive fictions within each other. 74 THE SATANIC VERSES But when he has rested he enters a different sort of sleep, a sort of not-sleep, the condition that he calls his listening, and he feels a dragging pain in the gut, like something trying to be born, and now Gibreel, who has been hovering-above-looking-down, feels a confusion, who am I, in these moments it begins to seem that the archangel is actually inside the prophet, I am the dragging in the gut, I am the angel being extruded from the sleeper’s navel, I emerge, Gibreel Farishta, while my other self, Mahound, lies listening, entranced, I am bound to him, navel by navel, by a shining cord of light, not possible to say which of us is dreaming the other. We flow in both directions along the umbilical cord. (SV 110) There is a dizzying play of fictional perspectives at work here. If Mahound questions his own identity, referring upwards to Gibreel; and Gibreel questions his identity, referring upwards to the author-God, then where exactly are we? If they cannot tell ‘which of us is dreaming the other’, then what is the point of origin of Rushdie’s fiction? It is not unlike the situation in Hamlet, where Hamlet (the character in Shakespeare’s play) challenges the authenticity of the sentiments uttered by the actor in the play-within-the play – ‘What’s Hecuba to him or he to Hecuba, / That he should weep for her?’4 – when the same argument applies by domino effect to Hamlet himself. Fiction collapses into discourse; into what Beckett has most unremittingly analysed as the migrant voice, migrant in an ultimate sense, that travels with its supply of words through all the categories of culture: human individuals as well as texts, documents as well as institutions. Steven Connor has rightly suggested that ‘the question of identity’ in The Satanic Verses is ‘closely implicated with the possibilities of fiction’,5 and this is how the imbrication takes place. We need to be able to ‘ride the thermals’ in this novel, to respond appropriately to the currents of discourse, the different registers engaged, the light verbal signals given. And Rushdie is prepared to provide alternative metaphors for this process of creation, exchange, interpretation – metaphors often derived (as in previous novels) from the media. Thus Gibreel’s point of view is identified as ‘sometimes that of the camera and at other moments, spectator. When he’s a camera the pee oh vee is always on the move, he hates static shots . . . But as the dream shifts, it’s always changing form, he, Gibreel, is no longer a mere 75 SALMAN RUSHDIE spectator but the central player, the star’ (SV 108). We recall what Rushdie said about the form of the novel ‘metamorphosing all the time’, and here we see exactly what he means. This makes for demanding reading, but, once the principle of the double narration has been grasped, it does make sense – and actually provides some of the novel’s most spectacular imaginative effects. We become accustomed to being in two places at once; thus, when in section III Gibreel is held spellbound by Rosa Diamond’s stories, we are explicitly reminded of his inextricable involvement with the prophet Mahound (SV 150); when in section V he endures a week’s tormented sleep in Allie Cone’s flat, muttering ‘Jahilia, Al-Lat, Hind’, and later sleeptalks in Arabic (SV 301, 340), he is understood to be labouring at the articulation of the new religion, the new Idea. When in section VII Gibreel recites the names of the teenage prostitutes at King’s Cross, the names are the same as those of the prophet’s wives, usurped by the prostitutes in Jahilia (SV 460, 382); and when at the end of this chapter Gibreel calls out the name ‘Mishal’, it is not the distraught Mishal from the Shaandaar Café he is addressing but Mirza’s wife Mishal, from the Ayesha story, who is about to be drowned beneath the waters of the Red Sea (SV 469, 503). There is even a remarkable paragraph, in the same section [VII], where Gibreel is identified as passing through no fewer than five narratives simultaneously: he understands now something of what omnipresence must be like, because he is moving through several stories at once, there is a Gibreel who mourns his betrayal by Alleluia Cone, and a Gibreel hovering over the death-bed of a Prophet, and a Gibreel watching in secret over the progress of a pilgrimage to the sea, waiting for the moment at which he will reveal himself, and a Gibreel who feels, more powerfully every day, the will of the adversary, drawing him ever closer, leading him towards their final embrace: the subtle, deceiving adversary, who has taken the face of his friend, of Saladin his truest friend, in order to lull him into lowering his guard. And there is a Gibreel who walks down the streets of London, trying to understand the will of God. (SV 457) This is a triumph of narrative art, and one that even goes a trick or two, in the treatment of narrative time, beyond Sterne.6 But the novel is not simply a postmodern puzzle for the reader to solve, although there are enough clues to keep the curious 76 THE SATANIC VERSES reader happy: in the numerological references (666 the Number of the Beast, 420 a section in the Indian criminal code), and reversible dates such as 1961 that read the same upside down – as (apparently) turning a watch upside down in Bombay will give you the time in London. Then there are the self-descriptive names (Alleluia Cone, Jumpy Joshi) and indeed the whole system of doubled names (Hind/Hind, Mishal/Mishal), that link the levels of the plot; and indicate an indebtedness to both Joyce and Freud.7 We may now return from the structure to consider the line of the narrative itself (what is actually witnessed and recorded by this flexible point of view); and then on, as it were out at the other side, to reconsider Rushdie’s articulation of his themes. As will have become clear by now, it is no simple matter to do even this, since the ‘waking’ narrative of the odd-numbered chapters likewise has its fissures and gaps, its equivocations and aporias. Not only does Gibreel live between two worlds, fearing the ‘leakage’ of one into the other, but Saladin also inhabits an unstable universe, by contagion – both as the satanic half of Gibreel’s angel (‘the two men, Gibreelsaladin Farishtachamcha, condemned to their endless but also ending angeldevilish fall’ (SV 5) ), forced to share and replicate some of Gibreel’s dreams and visions – and also – in his ‘own’ person – as the metamorphosed victim of a racist society. Section III has delivered the reborn pair into the care of Rosa Diamond, a mysterious woman with a memory as archaic as that of Tai the boatman,8 and an equally seductive gift for magic-realist narrative. (Critics who have objected to this passage as selfindulgent or superfluous seem not to appreciate its importance in establishing the protocol of the ‘hinged’ narrative, the jewelled lever of simultaneity referred to earlier.) But only Gibreel is exposed to this, Rosa’s stories ‘winding round him like a web’ (SV 146), since Chamcha has meanwhile been arrested by the police as an illegal immigrant – Gibreel’s evasion of this treatment, partly because of the appearance of a halo which confounds the law, making him a ‘traitor’ in Chamcha’s eyes. The supernatural level of the narrative reasserts itself as Chamcha gradually turns into a goat, complete with horns, hooves, and tail. The allusion to Lucian’s metamorphic Golden Ass (its author later identified as colonial subject of an earlier 77 SALMAN RUSHDIE empire (SV 243) ), foregrounds the real, social significance of this transformation: ‘they have the power of description’ (explains a friendly manticore), ‘and we succumb to the pictures they construct’ (SV 168). And it is in this disadvantaged condition that Saladin sees ‘his’ Britain with new eyes: including his wife, Pamela, who, believing him dead, has started an affair with his old friend Jumpy Joshi. She dreams of him confiding in her his new vision of terminal decline: ‘ ‘‘Things are ending,’’ he told her. ‘‘This civilization; things are closing in on it. It has been quite a culture, brilliant and foul, cannibal and Christian, the glory of the world. We should celebrate it while we can; until night falls’’ ’ (SV 184). Meanwhile Gibreel has also made his way (with his halo) to ‘Ellowen Deeowen’ London, pursued by ‘the fear that God had decided to punish him for his loss of faith by driving him insane’, by ‘the terror of losing his mind to a paradox, of being unmade by what he no longer believed existed, of turning in his madness into the avatar of a chimerical archangel’ (SV 189). He is pursued also by the ghost of Rekha Merchant, who transforms ‘Proper London’ into ‘that most protean and chameleon of cities’, the underground into a ‘subterranean world’ out of Virgil or Dante ‘in which the laws of time and space had ceased to operate’, into a ‘hellish maze’, a ‘labyrinth without a solution’ where he must continue his ‘epic flight’; and where he is rescued by the reappearance of Allie Cone (SV 201). Section V (‘A City Visible but Unseen’) is the longest in the novel. It is divided into two chapters, each subdivided into some twenty shorter sections. This episodic structure helps to achieve the effect of dislocation intended here – rather like the ‘Wandering Rocks’ section in Ulysses. The first chapter follows Saladin through Thatcher’s Britain. These pages (SV 243–94) are the satirical centre of the novel, switching between passages of low realist description and high cultural analysis. The low realism is associated with the Shaandaar Café, where the transformed Chamcha takes refuge, with its improbable proprietor Mr Sufyan, his unforgiving wife Hind (a crossover name), and two teenage daughters, Mishal and Anahita, who are living London to the full. The ‘high culture’ is represented by Mimi Mamoulian and her playboy friend, Billy Battuta, and the grotesque Hal Valance, whose energetic exploitation of 78 THE SATANIC VERSES ‘adland’ draws on Rushdie’s own experience of that world. Mimi is well able to defend her jingles against Chamcha’s analysis: ‘I am an intelligent female. I have read Finnegans Wake and am conversant with post-modernist critiques of the West, e.g. that we have here a society capable only of pastiche: a ‘‘flattened’’ world. When I become the voice of a bubble bath, I am entering Flatland knowingly . . . ’. It is Hal who refers to ‘Mrs Torture’, and understands the kind of newness she wants to bring into the world: ‘In with the hungry guys with the wrong education. New professors, new painters, the lot. It’s a bloody revolution. Newness coming into this country that’s stuffed full of fucking old corpses’ (SV 261, 270). The Hot Wax nightclub, with its subversive ‘meltdown’ ritual of wax effigies, floats somewhere between the two categories as it awaits the fire that will conclude this section; as does Jumpy’s jealous critique of Hanif Johnson, right-on lover of the tempting Mishal. ‘Hanif was in perfect control of the languages that mattered: sociological, socialistic, black-radical, anti-anti-anti-racist, demagogic, oratorical, sermonic: the vocabularies of power. . . . But . . . his envy of Hanif was as much as anything rooted in the other’s greater control of the languages of desire.’ This makes him painfully aware that ‘language is courage: the ability to conceive a thought, to speak it, and by doing so to make it true’. At the same time, Jumpy has a more profound perception which is more to do with language as consciousness than language as power. ‘The real language problem: how to bend it shape it, how to let it be our freedom, how to repossess its poisoned wells, how to master the river of words of time of blood: about all that you haven’t got a clue’ (SV 281). At the end of this chapter, Saladin is returned to human shape, partly ‘by the fearsome concentration of his hate’ for Gibreel, who now haunts his dreams; as Saladin will symmetrically appear ‘on the screen of [Gibreel’s] mind’ at the end of the next (SV 294, 355). The sixty pages of section V.2 are the most complex and therefore the most tightly organized in the novel. Allie Cone’s father provides a prelude, the ‘short story’ of his life featuring like the interpolated tale in an eighteenth-century novel. Born a Jew in Poland, he has (like Grimus) experienced the extreme horrors of the camps, and denied his past in order to survive: ‘he wanted to wipe the slate clean’; ‘ ‘‘l am English now’’ he would say proudly in his thick East-European accent’ (SV 297–8). As 79 SALMAN RUSHDIE such he is one of the spokesmen for the discontinuous, disintegrative spirit in the novel. For him, ‘this most beautiful and most evil of planets’ is beyond redemption, beyond understanding: ‘The world is incompatible . . . Ghosts, Nazis, saints, all alive at the same time; in one spot, blissful happiness, while down the road, the inferno’ (SV 295). And T. S. Eliot’s ‘unreal city’ from The Waste Land is the most visible aspect of this; for him ’the modern city . . . is the locus classicus of incompatible realities’ (SV 314). But his philosophy does not save him: ‘Otto Cone as a man of seventy-plus jumped into an empty lift-shaft and died’ (SV 298). (It is possible that Rushdie may have been thinking here of Auschwitz survivor Primo Levi, who committed suicide in 1987.) The rest of the chapter follows Gibreel’s own fight against disintegration and the will-to-suicide, alongside an Allie Cone who has had to fight her battles too. She tells Gibreel that she went up the mountain ‘to escape good and evil . . . because that’s where all the truth went’, deserting the cities where it is ‘all made up, a lie’. She is fearful especially of love, ‘that archetypal, capitalized djinn’, and ‘the blurring of the boundaries of the self’ (SV 314). But Gibreel’s jealousy breaks first, blurring other, more catastrophic boundaries: ‘the boundaries of the earth broke . . . and as the spirits of the world of dreams flooded through the breach into the universe of the quotidian, Gibreel Farishta saw God’ (SV 318). In the extraordinarily risky, exposed, and comic passage that follows we perceive that the ‘God’ Gibreel sees is none other than the ‘myopic scrivener’ Salman Rushdie himself: ‘the apparition was balding, seemed to suffer from dandruff and wore glasses.’ More vulnerable than the John Fowles who puts in an appearance in his own The French Lieutenant’s Woman, Rushdie offers himself as a ‘hinge’ here. It is as if the actor playing Hamlet (to return to the example suggested above) should arraign Shakespeare on stage: who is this guy responsible for so much commotion? Why doesn’t he leave us in peace? (And indeed the exhausted Gibreel has protested earlier in just such terms: ‘If I was God I’d cut the imagination right out of people and then maybe poor bastards like me could get a good night’s rest’ (SV 122).) But the author-God invoked here will not answer the ultimate question: ‘Whether We be multiform, plural, representing the union-by-hybridization of such opposites as Oopar and Neechay, or whether We be pure, stark, 80 THE SATANIC VERSES extreme, will not be resolved here’ (SV 319). If God exists, he is the supreme equivocator. Gibreel leaves the relative security of Allie’s flat for a renewed assault by a London that has ‘grown unstable once again’. There is no defence now from vision (‘When you looked through an angel’s eyes you saw essences instead of surfaces’), no hiding from the angel’s memory of the Fall, no choice in the simple alternative: ‘the infernal love of the daughters of men, or the celestial adoration of God’ (SV 320–1). The comic mode reasserts itself as Blake’s prophetic ‘map’ of London is replaced with the humble A to Z. With this Gibreel sets out to save the city from itself (‘the atlas in his pocket was his master plan’), but he finds that ‘the city in its corruption refused to submit to the dominion of the cartographers’ (SV 326–7) – as is proved by his farcical attempt to intervene in a lovers’ quarrel at the Angel tube station. The ghost of Rekha Merchant appears to read Gibreel a lecture on comparative religion. The ‘separation of functions, light versus dark, evil versus good, may be straightforward enough in Islam’, she observes, but Deuteronomy provides a more archaic and possibly truer formulation: ’I form the light, and create darkness; I make peace and create evil; I the Lord do all these things’ (SV 323). The fundamental principle of equivocation, reversible values, and significances is never far from the surface. But Gibreel is by this time too far gone in schizophrenia to take heed, and the precise moment of his splitting into two is presented as a cultural phenomenon, via Beckett and Stevenson. ‘He had begun to characterize his ‘‘possessed’’, ‘‘angel’’ self as another person: in the Beckettian formula, Not I. He. His very own Mr Hyde’ (SV 340). The media world returns as the stammering film-maker Sisodia proposes that Gabriel should make a comeback in a ‘theological’, playing none other than the Angel Gibreel – the argument being that if, for once, ‘those stories were clearly placed in the artificial, fabricated world of the cinema, it ought to become easier for Gibreel to see them as fantasies, too’ (SV 347). But Rushdie’s design requires that the experiment fails, precipitating Gibreel instead over the edge into psychosis. The sure sign of this is that he sees the split as occurring ‘not in him, but in the universe’; there are now ‘two realities, this world and another that was also right there, visible but unseen’. This decomposed vision makes everything simple: 81 SALMAN RUSHDIE No more of these England-induced ambiguities, these BiblicalSatanic confusions! . . . Forget those son-of-the-morning fictions . . . How much more straightforward this version was! How much more practical, down-to-earth, comprehensible! – Iblis/Shaitan standing for the darkness, Gibreel for the light. – Out, out with these sentimentalities: joining, locking together, love. Seek and destroy: that was all. (SV 351–3) The last of the London sections, ‘The Angel Azraeel’, brings all these tensions to fulfilment – and provocatively poses the formal problem at the same time. ‘What follows is tragedy’: or, since tragedy is ‘unavailable to modern men and women’, at least a ‘burlesque for our degraded, imitative times’. But no formal inflection can avoid the underlying question: ‘which is, the nature of evil, how it’s born, why it grows, how it takes unilateral possession of a many-sided human soul’ (SV 424). ‘It all boiled down to love’, reflects Saladin at the beginning, and he tries to implant this principle, celebrating ‘the protean, inexhaustible culture of the English-speaking peoples’, and even the ‘faded splendours’ of London itself. ‘Resurrection it was then’, he concludes, ‘roll back that boulder from the cave’s dark mouth’ (SV 397–401). Even overexposure to the ‘fast-forward’ culture of TV and the scavenging tabloids brings him the image of a grafted tree that reminds him of (and redeems) a tree cut down in anger in his father’s garden. But Saladin too is assailed at this point with ‘double vision, seeming to look into two worlds at once’, when he sees/feels Gibreel bearing down on him, ‘the icy shadow of a pair of gigantic wings’ (SV 416). The media party at Shepperton Studios (a brilliant ten-page set-piece: SV 411–21) brings the two into collision. Saladin becomes Iago to Gibreel’s Othello, with Allie Cone the innocent victim of his customized ‘satanic verses’ recited over the telephone; provoking Gibreel to seek vengeance – armed, appropriately enough for this black comedy of communications, with a trumpet rather than a sword. The crisis of the London plot involves a racially motivated murder enquiry, with a media essay on what the TV camera sees – and (like Lear’s ‘scurvy politician’) does not see, including a police cover up that involves the deaths of both Pamela and Jumpy Joshi and their unborn child. London disintegrates in Gibreel’s vision into its destructive elements, its competing cultural descriptions: ‘This is no Proper London: not this 82 THE SATANIC VERSES improper city. Airstrip One, Mahogonny, Alphaville. He wanders through a confusion of languages. Babel . . . ‘‘The gate of God.’’ Babylondon’ (SV 459). The novel veers at this point (deliberately, confusingly) between the low mimetic of ‘derelict kitchen units, deflated bicycle tyres, shards of broken doors, dolls’ legs, vegetable refuse’, the moralization of these details in ‘shattered job prospects, abandoned hopes, lost illusions, expended angers, accumulated bitterness, and a rusting bath’, and Blakeian vision, where a ‘rotting pile of envy’ blossoms into bushes on the concrete, ‘needing neither combustible materials nor roots’, creating an ‘impenetrable . . . garden of dense intertwined chimeras’, like ‘the thornwood that sprang up around the palace of the sleeping beauty in another fairy-tale, long ago’ (SV 461–2). These formal strands are woven together in the burning of the Shaandaar Café, where Gibreel spontaneously rescues Saladin – his evil adversary: ‘the fire parting before them like the red sea it has become’ (SV 468) – the scene also weaving together Rushdie’s two fictional worlds, as Ayesha and her pilgrims set out on their journey. There is less need to comment in detail on the visionary sections, partly because the narrative substance has already been placed within the overall structure and partly because much of the criticism of the novel has focused almost exclusively on this aspect. (Steven Connor has justly remarked that the emphasis on imagined Islam has tended to ‘ship the novel safely abroad’, away from its intended audience.9 ) But a brief consideration of the principal elements will help to clarify Rushdie’s overall design. It is in section II that we are brought closest to the moment of revelation itself (SV 112), and the true terror of uncertainty as to the origin of the ‘voice’. (Srinivas Aravamudan’s essay offers the best commentary on this passage and its implications.10) It is here, also, that Mahound is tempted (like Christ in the wilderness) by the ‘satanic verses’ that would compromise Islam into recognizing the three goddesses Al-Lat, Manat, and Uzza as ‘worthy of devotion’: verses that he first accepts – in the wake of his uncertainty – and then rejects, partly prompted by Hind, who warns him that ‘between Allah and the Three there can be no peace’ (SV 121). But the unidentified voice has the last unsettling word: ‘it was me both times, baba, me first and second also me. From my mouth, both the statement and the repudiation, verses and 83 SALMAN RUSHDIE converses, universes and reverses, the whole thing, and we all know how my mouth got worked’ (SV 123). Or perhaps we do not. The closest we get to interrogating the voice is in section IV, where Gibreel turns on his tormentor/ narrator and tries to ask the fundamental question: where do the words come from? They are ‘not his; never his original material. Then whose? Who is whispering in their ears, enabling them to move mountains, halt clocks, diagnose disease? He can’t work it out’ (SV 234). Some critics have argued that we are meant to understand the devil to be the under-narrator of The Satanic Verses.11 And we do need to keep in mind the epigraph Rushdie puts to the novel, taken from Defoe’s History of the Devil. This presents as it were a curriculum vitae for the fallen angel, which at least allows his nomination for the post. Satan, being thus confined to a vagabond, wandering, unsettled condition, is without any certain abode; for though he has, in consequence of his angelic nature, a kind of empire in the liquid waste or air, yet this is certainly part of his punishment, that he is . . . without any fixed place, or space, allowed him to rest the sole of his foot upon. There is also, I suggest, in Rushdie’s textual self-interrogation, a reference to Hughes’s bird-devil from Crow, who according to the Manichaean myth refashioned by Hughes takes over the work of creation when God falls asleep; and Crow’s vision is God’s nightmare, as Gibreel’s visions may plausibly be. But it would be false, reductive, to seek to ground a reading of The Satanic Verses in exclusively theological terms. The devil we may meet in Rushdie is Blake’s devil, or Bulgakov’s; and the voice is ultimately Beckett’s voice, the furthest we can go in reaching back for the origins of consciousness, the grounding of being in the ‘unformulable groping of the mind’,12 the grammatical fiction attached to one pronoun or another. The voice finds a different route in section VI, associated as it is here with the satirist Baal who has parodied the sacred revelation, and who claims (blasphemously but scrupulously), ‘I recognize no jurisdiction except that of my Muse; or, to be exact, my dozen Muses’ – that is, the twelve favoured prostitutes in the brothel. The reward of his honesty is execution by Mahound: ’Writers and whores. I see no difference here’ (SV 391–2). Each of the 84 THE SATANIC VERSES seven scenes or sequences in this section is introduced with the phrase ‘Gibreel dreamed . . . ’, floating the narrative off into its ambiguous space. And the last is the dream of the death of Mahound himself, to be lamented by Ayesha with her unambiguous faith. ‘But Ayesha wiped her eyes, and said: ‘‘If there be any here who worshipped the Messenger, let them grieve, for Mahound is dead; but if there be any here who worship God, then let them rejoice, for He is surely alive’’ ’ (SV 394). The significance of the ‘Untime of the Imam’ was briefly considered in Chapter 1. The story of Ayesha dramatizes the clash between philosophies of time, in that her faith and visions stand outside time – as the banyan tree with its half-mile span is a magical space under which her village nestles. She is unmoved by Mirza Saeed’s protest that ‘this is the modern world’ (SV 232), and leads the villagers off on their pilgrimage – including Mirza’s wife, Mishal, who has been converted. Section VIII follows the fortunes of the pilgrimage, tacking between two worlds, to the moment when the pilgrims walk into the sea and disappear. We should pay careful attention to the last two pages of this section (SV 505–7) – the sequel to the ‘failed’ pilgrimage, as the sceptical Mirza, whose wife has been drowned along with the others, comes to terms with his experience. He alone among the survivors claims not to have seen the parting of the Arabian Sea: ‘My wife has drowned. Don’t come hammering with your questions.’ He goes home to Peristan, where the great tree under which Ayesha preached her pilgrimage is dead, ‘or close to death’, the fields ‘barren as the desert’, and the gardens ‘in which, long ago, he first saw a beautiful young girl, had long ago yellowed into ugliness’. He takes to his rocking chair and prepares for death. Then on ‘the last night of his life’ he realizes that the tree is burning: ‘He saw the tree explode into a thousand fragments, and the trunk crack, like a heart.’ He himself falls in ‘the withered dust’, but as he does so he feels something brushing his lips and sees ‘the little cluster of butterflies struggling to enter his mouth’ – butterflies, the symbols of resurrection that have fed and clothed Ayesha from her first appearance. Then the sea poured over him, and he was in the water beside Ayesha, who had stepped miraculously out of his wife’s body . . . ‘Open,’ she was crying. ‘Open wide!’ Tentacles of light were flowing 85 SALMAN RUSHDIE from her navel and he chopped at them, chopped, using the side of his hand. ‘Open,’ she screamed. ‘You’ve come this far, now do the rest.’ He does the rest: ‘His body split open from his adam’s-apple to his groin’ (exactly the image Allie Cone had used, we recall, to express her fear of love: the fear of being opened ‘from your adam’s apple to your crotch’ (SV 314) ), ‘so that she could reach deep within him, and now she was open, they all were, and at the moment of their opening the waters parted, and they walked to Mecca across the bed of the Arabian Sea’. It is an extraordinary, concentrated image of birth, death, and resurrection, with the fact of human love and sexuality as the hinge that attaches us to these ultimate things – things that we can never ‘understand’, but only perceive as mysteries. And it is to religion, revelation, as well as to art, that we may look for a witness to their significance. The reader who has come so far may well wonder that the charge of blasphemy should be laid against such writing, and might rather share the view put cogently by Fawzia Afzal-Khan: the point of view that emerges is not anti-Islam but anti-closure, opposed, in principle, to any dualistic, fixed way of looking at things. Framed in this way, Rushdie’s impulse towards blasphemy becomes really an impulse towards regeneration: renewal born of a destruction of old, fixed ways of seeing and understanding.13 How to come down from such exaltation to the ubiquitous ‘real world’? Joyce manages this with the switch from the epiphanies to sombre realism in the Portrait; and Rushdie does it here to provide his own real-world conclusion. We switch from London – and from the Arabian Sea – to Bombay, eighteen months later, where both Gibreel Farishta and Saladin Chamcha have separately returned. Gibreel has come back to resume his film career, Saladin to be with his dying father; in fact, to ‘fall in love with [his] father’ again, and to recover ‘many old, rejected selves’ (SV 523). Then Allie Cone arrives en route for a mountaineering expedition, and Saladin becomes uneasy. He has a strange sense of being haunted, again; a feeling that ‘the shades of his imagination were stepping out into the real world, that destiny was acquiring the slow, fatal logic of a dream’ (SV 540). Allie dies in a fall from Gibreel’s apartment, just as Rekha 86 THE SATANIC VERSES Merchant had done. Gibreel arrives at Chamcha’s house in a distracted state to tell his story – which begins with a familiar formula: ‘Kan ma kan / Fi qadim azzaman . . . It was so it was not in a time long forgot’ (SV 544), the take-it-and-leave-it palinode on which all story floats – whether as enchanted sea or miasmal ocean. The substance of Gibreel’s ravings is a series of snatches from earlier in the novel, including of course Saladin’s own obscene ‘satanic verses’ multi-voiced over the telephone that drove him out of his mind. In the logic of the novel, one of them has to die; and it is Gibreel who pulls a pistol from the magic lamp and puts it in his mouth. All that is left is for Saladin to look out, from this side, at the Arabian Sea, on which the full moon makes a pathway ‘like a parting in the water’s shining hair, like a road to miraculous lands’. His own story, however, needs no miracle. His father is dead; but his woman, Zeeny Vakil, is at his elbow: ‘he was getting another chance.’ And, as in Joyce’s last novel, The Satanic Verses then puts its own tail in its mouth: ‘If the old refused to die, the new could not be born’ (SV 546–7). The Satanic Verses is a big novel in every sense: geographically (it has been called ‘a tale of three cities’), temporally (ranging from the seventh century to the twentieth), philosophically (the sophisticated but unaffected engagement with an encyclopaedia of ideas), culturally (in the different traditions with which it interacts), linguistically (there are six languages used in its composition). But it is as an exploration of the alternatives of faith and doubt that it has made the greatest impact – if these are actually alternatives. St Augustine said, credo quia impossible est: I believe because it is impossible to believe. This is the Augustine whose Confessions are one of the permanent tributaries of fiction; who is acknowledged as one of the architects of modern consciousness. And perhaps we should understand Rushdie’s troublesome novel (like Henry II ’s troublesome priest, Thomas Becket, prime mover of another pilgrimage) as a pilgrimage into the imagination in search of the source of religious feeling – however ambivalent its findings are. From first page to last, this is its true trajectory. No novel so obsessed by the temptation of faith can be judged as ‘blasphemous’. The only worlds that are seriously called into question in Rushdie’s fiction are the flattened, value-free world of contemporary culture, wherever 87 SALMAN RUSHDIE this may be found in its various conditions of exhaustion; and also the world of terror, whether this serves a secular ideology or whether (as often) it conceals itself behind a religious imagination that has been perverted and usurped in the pursuit of political power. APPENDIX: THE RUSHDIE AFFAIR Occasional reference only has been made in this study to the wider political response to The Satanic Verses, as this has intersected with legitimate criticism of the novel. But the wider response is also part of the story, and I will attempt to provide here an outline of the complicated events and issues that have become known as the Rushdie Affair. (For references and further reading, see the relevant section of the Select Bibliography.) The Satanic Verses was published in London by Viking on 26 September 1988. There were immediate protests in India against what was understood from reports (and from an interview with Rushdie published in India Today on 15 September under the heading ‘My Theme is Fanaticism’) to be a work that offered insult to Islam, and the novel was banned in India in October. Bans followed in South Africa (October), Bangladesh and Sudan (November), Sri Lanka (December), and Pakistan (February 1989); very soon it was proscribed throughout the Islamic world. In the UK an Action Committee on Islamic Affairs was founded to mobilize public opinion against the novel; there was a protest rally in London, followed by demonstrations in other British cities. On 14 January a copy of The Satanic Verses was burnt on the streets of Bradford, attracting widespread media attention. On 12 February six people were killed during anti-Rushdie riots in Islamabad. The climax to the protests occurred on 14 February 1989, when the Ayatollah Homeini of Iran (whose period in exile during the reign of the Shah is referred to in the novel: see pp. 205–15) issued a fatwa or religious edict, sentencing Salman Rushdie to death for blasphemy, under Islamic law; enjoining Muslims everywhere to carry out the sentence, offering the double incentive of martyrdom and a large material reward. With little choice, Rushdie accepted the offer of police protection, and went into hiding. Homeini himself died four 88 THE SATANIC VERSES months later, but hardliners seized on this fact to insist that the fatwa was irreversible; and indeed it was reiterated at intervals from Tehran. For ten years, until the peacemaking statement by the Iranian Government in September 1998, Salman Rushdie remained a fugitive from an archaic system of arbitrary punishment; a situation which, as he conceded during that time, seemed uncannily to have entangled him in his own fictions: ‘It is hard to express how it feels to have attempted to portray an objective reality and then to have become its subject’ (IH 404).14 The Committee for the Defence of Salman Rushdie and his Publishers was set up one week after the fatwa, to organize resistance, and has maintained a detailed chronology of events from ‘Day 1’, published under the title ‘Fiction, fact and the fatwa’ in The Rushdie Letters (1993).15 Here are listed the most significant events: including, alarmingly, the violence. The six deaths in Islamabad, already mentioned; the deaths of twelve Muslim rioters, shot by police in Bombay on 24 February 1989; the death of a security guard, killed in a bomb attack on the British Council library in Karachi four days later; another death and more injuries as a result of confrontations in Dhaka and Kharachi in March. Later the same month, two Muslim leaders who had spoken in Rushdie’s defence are shot and killed in Belgium. Naguib Mahfouz receives death threats; there are attacks on bookshops in England and abroad. Two years on, on 3 July 1991, the Italian translator of The Satanic Verses, Ettore Capriolo, is stabbed by an Iranian in Milan. A week later, the Japanese translator Hitoshi Igarashi is stabbed to death in Tokyo. There is no let-up. In September 1993 the Norwegian publisher of the novel, Wilhelm Nygaard, is shot and severely wounded. Despite this terroristic atmosphere – indeed, fuelled by a general revulsion at the idea of a death sentence being passed on a British citizen, as it were urbi et orbi, by a foreign power – there is a growing platform of support. First official support, from the UK Government, the governments of all the EC countries, the UN, and UNESCO, whose Director-General, Federico Mayor, identifies ‘a sense of loss whenever the human imagination is condemned to silence’. The American Senate passes a resolution condemning the threats against Rushdie, and there are statements of support from other American sources. Sir Sridath Ramphal, Secretary-General of the 89 SALMAN RUSHDIE Commonwealth Secretariat, reminds Iran of the boundaries of diplomatic behaviour: ‘Even countries that have banned the book’s publication draw the line at incitement to the author’s assassination.’ European writers, journals, newspapers, keep the matter in the forefront of debate; France is especially active. Wole Soyinka defends ‘the creative world’ against censorship; it has ‘the will and the resources and the imagination’ to resist. Developing out of an ICA conference in London in March, The Rushdie File is published in September; this catalogues worldwide support for Rushdie and his novel from writers and intellectuals – though not without some questioning and some dissenting voices. On the first anniversary of the fatwa, Harold Pinter reads Rushdie’s lecture ‘Is Nothing Sacred?’ to the ICA in London. On 30 September 1990 Rushdie is interviewed by Melvyn Bragg on BBC Television’s prime-time South Bank Show. On ‘Day 1,000’, American PEN organizes a demonstration in New York. On the third anniversary, Rushdie makes an appearance at an event in London hosted by the Friends of Salman Rushdie, attended by Günther Grass, Tom Stoppard, and Martin Amis, with videoed statements from Edward Said, Nadine Gordimer, Seamus Heaney, and Derek Walcott. One of the most problematic episodes was Rushdie’s decision, in December 1990, to ‘embrace Islam’ – announced in an article in The Times on 28 December. Here he professed ‘an intellectual understanding of religion’, and offered some concessions (including the suspension of plans for a paperback edition of his novel). This decision had been taken on the advice of Islamic scholars who had suggested such a move might defuse the international tension. But no such reciprocation occurred (as the July 1991 attacks illustrated), and Rushdie was forced to realize he had made a mistake – incurring criticism on both sides. Almost inevitably, he had to renege on this ‘conversion’, which he did in an address at Colombia University on 12 December 1991, concluding with the defiant assertion: ‘Free speech is life itself.’16 The much-disputed paperback edition was eventually published (by an anonymous ‘Consortium’) on 24 March 1992. Inevitably, discussion of the Rushdie Affair over the last ten years has provided the opportunity for much airing of prejudice, self-righteous moralizing, and even the settling of personal scores; which are no doubt best ignored. But some arguments 90 THE SATANIC VERSES need to be rehearsed. One thinks particularly of the attitude of those who, focusing on that part of the novel (the larger part) set in Britain, questioned the right of an immigrant author like Rushdie to criticize his adopted society in such uncompromising terms. This parallels the doubts expressed earlier by some critics as to his legitimacy as a commentator on those societies (India and Pakistan) he had left behind – doubts that have been considered in earlier chapters of this study. Both arguments are based upon the mistaken, mechanical assumption that a writer must be a paid-up member of a religion, group, or nation – complicit, accommodated – in order to earn the right to testify. Such an idea, one reflects, would disqualify many other twentieth-century writers: Conrad, Joyce, Lawrence (abroad), Hemingway, Orwell (in Spain), Kundera (in France), and so on. In fact, almost the opposite of this defensive reflex is true. Paradoxically perhaps, betrayal (in the conventional sense – that is, the exposure of one’s own inherited pieties to criticism, even to ridicule) is almost a writer’s duty. As Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus puts it: ‘You talk to me of nationality, language, religion. I shall try to fly by those nets.’17 The more significant debate has focused on the issue of free speech. Rushdie has declared himself a free-speech absolutist, and this is consistent with Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: ‘Everyone has the right of freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.’ But, as has been pointed out, this article is always quoted, misleadingly, out of any relevant context (even without the qualifying Article 20 that follows). Simon Lee has argued in The Cost of Free Speech, a book prompted by the Rushdie Affair among other issues, that the free-speech argument is usually mishandled by those who are unwilling to ponder its real complexities and contradictions – which are not helped by imprecise and inconsistent provisions in law. (‘The law . . . has been exposed as hopelessly confused by the Rushdie affair.’)18 This relates especially to the present law of blasphemy in Britain, which only protects the Christian religion – a reasonable cause for grievance in the Muslim community. (A private prosecution of the novel was rejected on precisely these grounds 91 SALMAN RUSHDIE in March 1989.19) This is a theme also of Richard Webster’s A Brief History of Blasphemy, subtitled Liberalism, Censorship, and ‘The Satanic Verses’.20 It is significant that both Lee and Webster are consistently critical of the one-sided way in which the freespeech issue has been used by Rushdie’s supporters, to the disadvantage of minority groups. But the law can only try to create the level playing field; it cannot dictate the rules of the game. The problem remains the cultural one of mutual incomprehension. Lee suggests that the ‘final lesson of the Rushdie affair for our debate on free speech is that it is bound up in our understanding of the differences between various modes of discourse’.21 Religious, cultural, and political discourses simply do not interface in the global village. Rhetoric and realpolitik – or fiction and fact; imagination and material conditions – are programmed for conflict on a whole range of issues.22 And so, whereas Rushdie and his supporters (of whom I count myself one) have the right and duty to argue their case, this must include a recognition that the very terms of the argument will make their conclusions unacceptable, even incomprehensible, to others. Which brings us back to blasphemy: one of those archaic, untranslatable words. The perception of blasphemy arises at the fault-lines of discourse, where one system of values and beliefs conflicts with another outside the tolerance levels normally observed. (Malise Ruthven alludes in his sympathetic study of the case to ‘the gulf between Islamic and Christian values’.23) Reading The Satanic Verses on its own terms, as I have tried to do in the foregoing chapter, it is hard to understand the grounds for real offence. But, like the retina, the imagination itself has its blind spots. Trying to compensate for these, it should not be impossible to understand how a different structure of consciousness might find such a radical exercise in scepticism as the novel conducts to be intolerable, even repugnant. Ruthven identifies ‘religious doubt’ as ‘the central condition of modernity’;24 it should be no surprise that many will resist the condition. The communications problem is real, and must be admitted as such; there may be good faith (as well as the other kind) on both sides of the question. But what cannot be admitted, ever, as a consequence of this, is the right of anyone to short-circuit the argument by threatening the life of an antagonist. In an 92 THE SATANIC VERSES observation cited by Lee, a Supreme Court judge argued in a censorship case from 1927 that ‘the remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence’.25 More speech, more evidence, more argument, more criticism; more activity, that is to say, in what Rushdie has called ‘the arena of discourse . . .where the struggle of languages can be acted out’ (IH 427). Now that the Iranian Government has dissociated itself from the infamous fatwa, we can hope not only that Salman Rushdie may be returned to his life, but that the novel at the epicentre of the Affair may be returned to this arena of discourse.26 93 6 Haroun and the Sea of Stories and East, West HAROUN AND THE SEA OF STORIES Like many a fairy tale, Rushdie’s Haroun and the Sea of Stories explores complex moral and philosophical questions in a simple way: via the elementary emblematic of narrative. The misfortunes of Haroun’s father, Rashid, who loses his storytelling gift when challenged by literal questions, and the adventures of Haroun himself among mythological beasts, evil demons, supernatural seas, and magical landscapes, are a fictive reflection of real problems in the real world. It is not surprising, therefore, that the novel may be read at one level as a coded account of Rushdie’s personal predicament after the fatwa – a reading encouraged by the acrostic reference to his son Zafar that appears as dedication: Zembla, Zenda, Xanadu, All our dream-worlds may come true. Fairy lands are fearsome too. As I wander far from view Read, and bring me home to you. Rushdie told James Fenton, in interview, that he had promised his son ‘the next book I wrote would be one he might enjoy reading’.l The details of the coded reading may easily be sketched out: the separation of the family, the attack on free speech (‘the greatest Power of all ’ (HSS 119) ) by Khattam-Shud, the embodiment of silence and negation; the sinister power of Bezaban, the idol of black ice. A glossary lists names that ‘have been derived from Hindustani words’, and Bezaban is given as ‘Without-a-Tongue’ (HSS 217). But obviously this reading, while legitimate (even inevitable), risks being reductive.2 Haroun is also 94 HAROUN AND THE SEA OF STORIES AND EAST, WEST a story about story itself, about the need and the capacity of human beings to communicate with each other, across time and across cultures – and despite whatever other obstacles may be put in their way. In this respect, Haroun may also be compared with Gulliver’s Travels, a fiction which is both available to a contextualized, ‘local’ decoding in terms of eighteenth-century political personalities and events but also floats free of this encumbrance on a sea of its own, a mythical, magical, and dehistoricized account of human behaviour that retains nevertheless an important moral dimension. It will be interesting, therefore, to consider how Haroun offers its own simplified version of Rushdie’s recurrent themes. To begin with, the novel provides us with an elementary theory of narrative, communicated in terms of the central metaphor of the ‘sea of stories’. This sea is located, we discover, on the invisible, elliptical moon Kahani, the orbit of the imagination (the word simply means ‘story’), and is fed by a wellspring that constitutes a powerfully positive image: ‘a huge underwater fountain of shining white light’ (HSS 167). This fountain has immediate analogies in the romantic imagery of Blake and Coleridge (who is quoted in the text); but there are more archaic sources, first in the Sanskrit Kathasaritsagara or ‘ocean of the stream of stories’ referred to in Midnight’s Children and then to Ganga, the queen among rivers, in the Ramayana, which is invoked for its healing properties by Ansurmat near the beginning of the poem. This magical sea is the source of all story, as Haroun’s father assures him, introducing his son to the metaphor that will be literalized in the narrative that follows. Sailing on the sea later, Haroun is able to observe for himself its emblematic qualities: He looked into the water and saw that it was made up of a thousand thousand thousand and one different currents, each one a different colour, weaving in and out of one another like a liquid tapestry of breathtaking complexity; and Iff explained that these were the Streams of Story, that each coloured strand represented and contained a single tale. Different parts of the Ocean contained different sorts of stories, and as all the stories that had ever been told and many that were still in the process of being invented could be found here, the Ocean of the Streams of Story was in fact the biggest library in the universe. (HSS 72) The beauty of stories is that they are (like water itself) recyclable. 95 SALMAN RUSHDIE As his guide Iff the Water-Genie tells Haroun – in what is a very creditable version of the origins of narrative, and a good summary of what Rushdie has argued in discursive contexts elsewhere – ‘Nothing comes from nothing . . . no story comes from nowhere; new stories are born from old – it is the new combinations that make them new.’ And it is the success of Rushdie’s recycling that it can retain fidelity to its ancient sources, the pristine quality, while at the same time incorporating contemporary references: as here, to Borges’s story ‘The Library of Babel’.3 In answer to Haroun’s question about turbulence, Butt the Hoopoe contributes his own narratological formula: ‘Any story that is worth its salt can handle a little shaking up’ (HSS 86, 79); and it is up to the Floating Gardeners (one of the more delightful inventions in the book) to ensure that the strands do not get too tangled. These principles are enough to justify the wholesale recasting of ‘half-familiar stories’ by the entertaining (and, as it turns out, cross-dressed) page-boy Blabbermouth.4 However, the sea of stories and its subscribers, professional storytellers like Rashid, have more to worry about than turbulence. There is a plot abroad systematically to poison the sea, and even to plug the wellspring itself. The author of this plot is the sinister Khattam-Shud, introduced as ‘the ArchEnemy of all Stories, even of Language itself . . . the Prince of Silence and the Foe of Speech’, and later revealed to be none other than the Cultmaster himself, high priest of the idol Bezaban (HSS 39, 101). He is the principle of negation, announcing that ‘for every story there is an anti-story’: ‘There he sits at the heart of darkness . . . and he eats light, eats it raw with his bare hands’ (HSS 160, 145). Khattam-Shud’s hostility to stories is for reasons that would be described in the real world as ideological – as he explains in response to Haroun’s question as to why he hates stories so much, since for him they are ‘fun’: ‘The world, however, is not for Fun,’ Khattam-Shud replied. ‘The world is for Controlling.’ ‘Which world?’ Haroun made himself ask. ‘Your world, my world, all worlds,’ came the reply. ‘They are all there to be Ruled. And inside every single story, inside every Stream in the Ocean, there lies a world, a story-world, that I cannot Rule at all. And that is the reason why.’ (HSS 161) Rushdie’s metaphor lends itself to ecological elaboration, as 96 HAROUN AND THE SEA OF STORIES AND EAST, WEST with Haroun’s analysis of the polluted waters around KhattamShud’s shadow-ship, the huge black ‘ark’ (like a rogue oil tanker) that actually manufactures poison: The thick, dark poison was everywhere now, obliterating the colours of the Streams of Story, which Haroun could no longer tell apart. A cold, clammy feeling rose up from the water, which was near freezing point, ‘as cold as death’, Haroun found himself thinking. Iff’s grief began to overflow. ‘It’s our own fault,’ he wept. ‘We are the Guardians of the Ocean, and we didn’t guard it. Look at the Ocean, look at it! The oldest stories ever made, and look at them now. We let them rot, we abandoned them, long before this poisoning. We lost touch with our beginnings, with our roots, our Wellspring, our Source . . . .’ (HSS 146) They are alerted to this situation by Haroun’s nightmare, a perverted version of ‘Princess Rescue Story Number S/1001/ ZHT/420/41(r)xi’, which he endures after drinking polluted water from the sea. ‘ ‘‘It’s pollution,’’ said the Water-Genie gravely. ‘‘Don’t you understand? Something, or somebody, has been putting filth into the Ocean. And obviously if filth gets into the stories, they go wrong’’ ’ (HSS 73–5). The celebratory and confirmatory tone of Haroun requires that Khattam-Shud should ultimately be perceived as a comic grotesque, a pantomime figure. This outcome is cleverly plotted, in that he is identified at the end with the contemptible clerk Mr Sengupta, whose distinguishing feature is that he has ‘no imagination at all’, whose mean-minded literalism temporarily disrupts the happy Khalifa family, but who is finally sent packing: ‘What a skinny, scrawny, snivelling, drivelling, mingy, stingy, measly, weaselly clerk! As far as I’m concerned he’s finished with, done for, gone for good’ (HSS 210). However, he does also function as a potent reminder of real evil in the real world, the kind of fanaticism that begins in division and ends in cruelty and terror. It is in the principle of division itself, the rigorous and destructive separating out of what should be complementary qualities, that Rushdie locates the real ‘poison’, here as elsewhere in his fiction. At one point Haroun observes the warrior Mudra ‘fighting against his own shadow’, a memorable image of disintegration, the negation of the true multidimensionality of experience – variously realized here in terms of bright versus dark, warm versus freezing, sociability, chatter, 97 SALMAN RUSHDIE and noise versus isolation, silence, and shadow. ‘It was a war between Love (of the Ocean, or the Princess) and Death (which was what the Cultmaster Khattam-Shud had in mind for the Ocean, and for the Princess, too).’ Mudra explains that KhattamShud has taken this division to its extreme: ‘he has separated himself from his Shadow!’, and can therefore be in two places at once’ (HSS 123, 125, 133). This is a more concrete example of the schizoid metaphysics of Gibreel Farishta in The Satanic Verses, who comes to believe (we may recall) that good and evil are not compounded together but entirely separate, the fruit of ‘two different trees’. But Haroun’s reflections take him beyond this bifurcated image to a vision of reintegration which is again consistent with Rushdie’s own mature thinking on the subject. ‘But it’s not as simple as that,’ he told himself, because the dance of the Shadow Warrior showed him that silence had its own grace and beauty (just as speech could be graceless and ugly); and that Action could be as noble as Words; and that creatures of darkness could be as lovely as the children of the light. ‘If Guppees and Chupwalas didn’t hate each other so,’ he thought, ’they might actually find each other pretty interesting. Opposites attract, as they say.’ (HSS 125) And this is exactly what is allowed to happen at the end. When the sun rises for the first time over Gup City, it destroys the ‘super-computers and gigantic gyroscopes that had controlled the behaviour of the Moon, in order to preserve the Eternal Daylight and the Perpetual Darkness and the Twilight Strip in between’; Kahani becomes ‘a sensible Moon . . . with sensible days and nights’ (HSS 172, 176). And, when ‘Peace [breaks] out’, it is marked by a series of reunions – of Night and Day, Speech and Silence, which ‘would no longer be separated into Zones by Twilight Strips and Walls of Force’; and of course, by the reunion of the Khalifa family itself (HSS 191, 210). The question that destabilized the ‘happy beginning’ of Haroun was Mr Sengupta’s querulous complaint, ‘What’s the use of stories that aren’t even true?’: which is first swallowed by Soraya, Rashid’s wife, and then fatally repeated to Rashid by his son Haroun. Haroun cannot ‘get the terrible question out of his head’, and is perplexed by his own reflections on truth and lies: 98 HAROUN AND THE SEA OF STORIES AND EAST, WEST Nobody ever believed anything a politico said, even though they pretended as hard as they could that they were telling the truth. (In fact, this was how everyone knew they were lying.) But everyone had complete faith in Rashid, because he always admitted that everything he told them was completely untrue and made up out of his own head. (HSS 20) The trouble is that Rashid loses faith in himself. One of Haroun’s favourites among his father’s stories is that of Moody Land: ‘the story of a magical country that changed constantly, according to the moods of its inhabitants. In Moody Land, the sun would shine all night if there were enough joyful people around . . . when people got angry the ground would shake; and when people were muddled or uncertain about things the Moody Land got confused as well.’ Moody Land sounds like the natural habitat of the ‘pathetic fallacy’, whereby we project our emotions onto our environment. But in the chill mist of the Dull Lake, Rashid is suddenly made to see it as fallacious. ‘ ‘‘The Moody Land was only a story, Haroun,’’ Rashid replied. ‘‘Here we’re somewhere real.’’ When Haroun heard his father say only a story, he understood that the Shah of Blah was very depressed indeed, because only deep despair could have made him say such a terrible thing’. (HSS 48). Rushdie’s own fairy tale provides, in its own terms, an answer to Mr Sengupta’s blank, banal, and reductive question. The answer is that truth and falsehood, reality and fiction – ‘the Frontiers of Height and Depth,’ as Swift has it – ‘border upon each other’,5 and cannot be simply lined up in opposition like the black and white pieces on a chessboard – the chessboard, we may remember, that is rejected as too simple a metaphor for human experience in Midnight’s Children; and that turns up again here in Haroun’s polluted dream.6 The positive and optimistic formula that first enables Haroun to take issue with his father’s depression, and his capitulation to the ‘real world’ of the Dull Lake, is what the reader carries back from Kahani, as Haroun himself brings back as talisman the model of his magical bird: ‘the real world was full of magic, so magical worlds could easily be real’ (HSS 50). Which takes us, via the Land of Oz, to Rushdie’s collection of short stories. 99 SALMAN RUSHDIE EAST, WEST Of the nine stories included in the collection East, West, the first six had been published previously in a number of different journals (the earliest in 1981). One can hardly expect the same degree of coherence from this collection, therefore, as from a novel – even a Rushdie novel. But the arrangement of the stories into three groups of three – East; West; and East, West (the three unpublished stories) – addresses directly the facts (and fictions) of cultural difference, misunderstanding, and antagonism; and it is under this aspect that the stories will first be considered here.7 The title is one half of an English proverbial saying – ‘East, West, Home’s Best’ – on which this collection (indeed, a good part of Rushdie’s work) is an ironic commentary. The proverb itself can be interpreted in at least two ways: ‘whether you travel to the east or the west, home (back in England) is best’: this is the nineteenth-century imperialist xenophobic reading. Or (the twentieth-century post-colonial, culturally pluralist reading): ‘whether you live in the east or the west, your home there is the best place to be.’ But there is a third reading – we might I suppose call this the postmodern or post-fatwah version – which is articulated by Rushdie at the end of his booklet on the film The Wizard of Oz (written for the British Film Institute in 1992). Rushdie loves the film but hates the ending, where Dorothy accepts the Good Witch Glinda’s suggestion that ‘there’s no place like home’: How does it come about, at the close of this radical and enabling film . . . that we are given this conservative little homily? Are we to believe that Dorothy has learned no more on her journey than that she didn’t need to make such a journey in the first place? Must we accept that she now accepts the limitations of her home life, and agrees that the things she doesn’t have there are no loss to her? ‘Is that right?’ Well, excuse me, Glinda, but is it hell. Rushdie offers us, in his conclusion, his own ‘little homily’ instead, premised on the interesting fact that, in the sixth of the thirteen Oz books that Frank Baum wrote following the success of the Wizard, Dorothy actually goes back to Oz with Auntie Em and Uncle Henry and becomes a princess (as all little girls should, given the right circumstances). 100 HAROUN AND THE SEA OF STORIES AND EAST, WEST So Oz finally became home; the imagined world became the actual world, as it does for us all, because the truth is that once we have left our childhood places and started out to make up our lives, armed only with what we have and are, we understand that the real secret of the ruby slippers is not that ‘there’s no place like home’, but rather that there is no longer any such place as home: except, of course, for the home we make, or the homes that are made for us, in Oz: which is anywhere, and everywhere, except the place from which we began. (WO 56–7) The themes of homelessness and making a home are explored in East, West in several different ways. First through the number of ‘displaced persons’, otherwise migrants, who actually feature in the stories. Everybody seems to live anywhere else except where they were born. Indians and Pakistanis are self-exiled in London; alongside them is a retired Grand Master from Hungary. ‘Exiles, displaced persons of all sorts, even homeless tramps have turned up for a glimpse of the impossible’ in ‘At the Auction of the Ruby Slippers’. Nor is this exclusively a contemporary experience; in the third of the ‘West’ stories, for example, Columbus languishes in exile at the court of Queen Isabella of Spain, her ‘invisible man‘, the exotic foreigner who lends her court ’a certain cosmopolitan tone’; meanwhile he has to console himself with those dreams and ‘possibilities’ that only ‘the harsh . . . ties of history’ will eventually cause to materialize (EW 107–19). The migrants’ difficulty with language itself underlines this alienation – a feature which is strongly marked in the last group of three stories, ‘East, West’, where cultures blend and clash. In ‘The Courter ’, the ayah is known as ‘Certainly-Mary’ and her Hungarian admirer as ‘Mixed-Up’ for precisely this reason; they are adrift in a tongue foreign to both of them. Though this does have its advantages: English was hard for Certainly-Mary, and this was a part of what drew damaged old Mixed-Up towards her. The letter p was a particular problem, often turning into an f or a c; when she proceeded through the lobby with a wheeled wicker shopping basket, she would say, ‘Going shocking,’ and when, on her return, he offered to help lift the basket up the front ghats, she would answer, ‘Yes, fleas.’ (EW 176) It is by this logic that the porter becomes the courter, and their relationship is adventitiously defined. The narrator’s more 101 SALMAN RUSHDIE shadowy father has his own problems, too; on one occasion he is slapped by an assistant in a chemist’s shop when he asks for ‘nipples’ rather than teats (EW 176, 184). The characters in ‘Chekov and Zulu’ have come by their nicknames likewise through an accident of language, mishearing the name ‘Sulu’ from Star Trek; not even from Star Trek direct, but from the series recycled on the radio from ‘cheap paperback novelizations’: ‘No TV to see it on, you see. The whole thing was just a legend wafting its way from the US and UK to our lovely hill-station of Dehra Dun’ (EW 165). The conversation in Zulu’s house in Wembley is hardly North London patois, either. But despite these displacements, in only one story does anyone actually follow Dorothy and go back home. This consolation is reserved for the 70-year-old ayah we have met as Certainly-Mary, whose life has been used up anyway in service abroad. And even here, the ‘culturally plural’ narrator (who has just been issued with his British passport) undercuts her decision, by refusing to choose between the cultural offerings available. the passport did, in many ways, set me free. It allowed me to come and go, to make choices that were not the ones my father would have wished. But I, too, have ropes around my neck, I have them to this day, pulling me this way and that, East and West, the nooses tightening, commanding, choose, choose. I buck, I snort, I whinny, I rear, I kick. Ropes, I do not choose between you, Lassoes, lariats, I choose neither of you, and both. Do you hear? I refuse to choose. (EW 211) The cultural question remains unanswered – on what is, significantly enough, the last page of the last story, with the strands left deliberately untied. A second theme that unites these stories is that developed in Chapter 1 of this study, and conveniently summarized in Rushdie’s critique of Oz: how ‘the imagined world [becomes] the actual world’, how the self is constructed out of the confrontation with circumstance. Six of the stories will furnish examples here – often, as we shall see, of relative failure in the task of self-making. Ramani the rickshaw-wallah in ‘Free Radio’ has ‘the rare quality of total belief in his dreams’, but this only makes him vulnerable to the persuasion of the ‘thief’s widow’ he lives with (another fictional embodiment of Mrs Gandhi) to accept the free radio in exchange for his right of reproduction. 102 HAROUN AND THE SEA OF STORIES AND EAST, WEST As the narrator tells him, ‘My idiot child, you have let that woman deprive you of your manhood! ’ Ramani never even gets his radio, but goes to Bombay, from where he writes letters full of fantasy about a new career in the movies, persisting with ‘the huge mad energy which he had poured into the act of conjuring reality’, and with which he has conspired (ironically) to cheat himself of his own future (EW 19–32). ‘The Prophet’s Hair’ is another fiction about how fiction – this time, in the form of superstitious belief – can ravage ordinary human life. The circumstances surrounding the theft, finding, and restealing of a relic destroy a merchant’s family: in a single catastrophic paragraph, he stabs his daughter (by mistake) and falls on his sword in remorse, for his wife to be ‘driven mad by the general carnage’ and committed to an asylum. But the relic is returned and authenticated: ‘It sits to this day in a closely guarded vault by the shores of the loveliest of lakes in the heart of the valley which was once closer than any other place on earth to Paradise’ (EW 55–7). The discrepancy between the untroubled, pellucid prose in which this story is narrated (suggested by the phrase that describes the family before their misadventure, enjoying a ‘life of porcelain delicacy and alabaster sensibilities’) and the savagery of its subject matter makes its own formal comment. The best-known story in the collection, ‘At the Auction of the Ruby Slippers’, is especially interesting in this connection because it derives from a real circumstance and then spirals off to make its point about imaginative excess. The real circumstance was the auction by MGM in May 1990 of the ruby slippers worn by Judy Garland in the Wizard of Oz film. The slippers went, Rushdie tells us, for ‘the amazing sum of $15,000. The buyer was, and has remained, anonymous. Who was it who wished so profoundly to possess, perhaps even to wear, Dorothy’s magic shoes? Was it, dear reader, you? Was it I?’ (WO 46). The question generates the story (first printed along with Rushdie’s essay), which explores the permeable boundaries between fact and fantasy, desire and its fulfilment. Among the people coming to bid for the slippers are fictional characters: from paintings, novels, and other films, all seeking to make their bids for power – or is it immortality? This permeation of the real world by the fictional is a symptom of the moral decay of our post-millennial culture. Heroes step down off 103 SALMAN RUSHDIE cinema screens and marry members of the audience. Will there be no end to it? Should there be more rigorous controls? Is the State employing insufficient violence? We debate such questions often. There can be little doubt that a large majority of us opposes the free, unrestricted migration of imaginary beings into an already damaged reality, whose resources diminish day by day. After all, few of us would choose to travel in the opposite direction (though there are persuasive reports of an increase in such migrations latterly). (EW 94–5)8 The slippers are magical currency; they can provide access to everything, the fulfillment of all our wishes and dreams. The narrator is bidding for the slippers himself; he wants their power to win a woman’s love. But, as the tension mounts in the saleroom, and the bids themselves spiral away from reality, the narrator is suddenly overtaken by another power: the detachment of pure contemplation, the ‘lightness of being’ characteristic of fiction itself. ‘There is a loss of gravity, a reduction in weight, a floating in the capsule of the struggle. The ultimate goal crosses a delirious frontier. Its achievement and our own survival become – yes! – fictions. And fictions, as I have come close to suggesting before, are dangerous.’ Dangerous because they may persuade us to accept the ‘damaged reality’ described above, or even contribute to it in ways that are suggested in the next paragraph. In fiction’s grip, we may mortgage our homes, sell our children, to have whatever it is we crave. Alternatively, in that miasmal ocean, we may simply float away from our desires, and see them anew, from a distance, so that they seem weightless, trivial. We let them go. Like men dying in a blizzard, we lie down in the snow to rest. (EW 102) This story fulfils, therefore, some of the anxieties about fiction expressed in the essays, how TV and the cinema may impair rather than enhance our sense of reality, how books themselves, and theatre, may distract us with false – which in the order of art means inadequately imagined – ideologies. There is another health warning against fiction in the first story in the final group, ‘Harmony of the Spheres’ – a story whose aptly named suicide hero Eliot Crane is a cousin-german of Gibreel Farishta. Crane is a cut-down Faust figure whose ‘immersion in the dark arts was more than scholarly’: ‘Pentangles, illuminati, Maharishi, Gandalf: necromancy was 104 HAROUN AND THE SEA OF STORIES AND EAST, WEST part of the zeitgeist, the private language of the counter-culture.’ He has met a demon. The impressionable Indian narrator Khan has been initiated by him: ‘I was taught the verses that conjured up the Devil, Shaitan, and how to draw the shape that would keep the Beast 666 confined.’ An immigrant at Cambridge, Khan believes Eliot can help him relocate and reinvent himself. in Eliot’s enormous, generously shared mental storehouse of the varieties of ‘forbidden knowledge’ I thought I’d found another way of making a bridge between here-and-there, between my two othernesses, my double unbelonging. In that world of magic and power there seemed to exist the kind of fusion of world-views, European Amerindian Oriental Levantine, in which I desperately wanted to believe. But Eliot turns out to be a paranoid schizophrenic, slave not master: ‘He couldn’t help anyone, the poor sap; couldn’t even save himself. In the end his demons came for him’, and he blows his brains out (EW 125–46). The two Indian diplomats in ‘Chekov and Zulu’ likewise never manage to disentangle the reality of their own lives as husbands and fathers from the fiction among which they grew up: the misapplied names from Star Trek are an index of a more profound (and yes: dangerous) misapprehension. It is an ironic comment on the mediatization of experience that, when he is fated to be in Rajiv Gandhi’s entourage at the moment of his assassination, Chekov steps into eternity aboard Captain Kirk’s spacecraft: ‘The scene around him vanished, dissolving in a pool of light, and was replaced by the bridge of the Starship Enterprise’ (EW 170). It is just another episode: a ‘virtual’ death rather than a real one. Finally, in the last and longest story, ‘The Courter’, for all the imaginative defences that may be set up, the real world reasserts itself unambiguously. The young Indian narrator grows up in recognizable London, but still at one remove from social reality not only because of the language barrier (that affects his family rather than himself) but once again because of the mediatized world he constructs for himself, composed of pop songs, hair styles, fashion, and The Flintstones. But history 1960s style irrupts into this story more decisively, with the assassination of Kennedy and the race-hate speeches of Enoch Powell on television (‘a vulpine Englishman with a thin moustache and mad eyes’), and finally the racial attack on his mother and sister that comes like an awakening slap from the outside world. 105 SALMAN RUSHDIE Fictions are dangerous. It is as if the regenerative sea of Haroun has degenerated here to the ‘miasmal ocean’ referred to in the ‘Ruby Slippers’; as if Khattam-Shud has had his way after all, and poisoned the Sea of Stories. And, if the inference to be drawn from the stories in East, West is, therefore, in some respects a negative one, then this may have something to do with the form of the short story itself, which is perhaps not the most congenial means of expression for Rushdie. It does not allow sufficient room for his ideas to stretch and develop, for the tentacular connections to establish themselves. Walter Benjamin remarked that the short story is alien to the oral tradition in that it does not allow ‘that slow piling one on top of the other of thin, transparent layers’, which image, he suggests, provides ‘the most appropriate picture of the way in which the perfect narrative is revealed through the layers of a variety of retellings’.9 Rushdie has himself observed that, if he has written relatively few short stories, this is because the material that might make a story tends to get swallowed up in the larger system of the novels, which he sees as ‘everything books’ made up of ‘a jostle of stories’; ‘and so there’s nothing left over for short stories’.10 And perhaps this is as it should be – as one last instance might confirm. In ‘Yorick’, a Shakespearean variation which is generally felt to be one of the less successful stories in the collection, the narrator breaks off at one point to remark, ‘it’s true my history differs from Master CHACKPAW’s . . . so let the versions of the story co-exist, for there’s no need to choose’ (EW 81). The point is, the writer of short stories has to choose, given the constraints of the form. Is this not a case of the novel-asgenie struggling to get out of the short-story-as-bottle? Out into the wider world where faith, hope, and fiction may carry us through; and the greatest of these may after all turn out to be fiction. Which is a possible reading of Rushdie’s next novel. 106 7 The Moor’s Last Sigh Rushdie’s first big novel since The Satanic Verses, seven years on, was awaited with cautious expectation. His readers had willed Rushdie to carry on writing, to triumph over the adversity of his circumstances, but at the same time there was some doubt expressed as to whether he could possibly recapture the imaginative liberty of his earlier work. And in the event The Moor’s Last Sigh was published to sympathetic rather than enthusiastic reviews.1 In the first book to include a section on the novel, Catherine Cundy offers what is (she concedes) a ‘largely negative assessment’. The novel has been marked, she feels, by the fact of Rushdie’s incarceration, and breathes a stifled, exhausted air as a result; it is in her view ‘strangely flat – with the two-dimensionality of a largely cerebral reconstitution of ‘‘reality’’ ’.2 (What work of art, one reflects, is not ‘cerebral’?) But it may be that there is something preconditioned about these judgements, as if the novel could not possibly be allowed to succeed, whatever its qualities, since that would somehow contradict the comfortable, common-sense idea we have of the continuity between the writer and the work. (One might note in passing that Cundy’s book frequently invokes biographical ‘facts’ to underpin critical judgements.) It should be possible to respond to the novel on its own terms, without such a reflex. It is an assumption of the present account that Rushdie was able to draw on all his resources as a writer for The Moor’s Last Sigh; and the argument, that, though it is deliberately refracted through the mirror of art, the novel is as ambitious, as demanding, and as fine as anything he has previously written. One should first note the continuities with Rushdie’s earlier work. The Moor’s Last Sigh returns to India, but to a different India from that of Midnight’s Children (or The Satanic Verses). This 107 SALMAN RUSHDIE is Spanish/Portuguese India, with a different colonial history; the echoes here are not of The East lndia Company, Amritsar, Mountbatten, and the Raj, but of Vasco da Gama, the Alhambra, and multicultural Goa with its Jewish and Christian communities. The title alludes to El ultimo suspiro del Moro, a hill in southern Spain so named because it was the place from which Boabdil, the last Moorish king of Granada, looked back at the city before going into exile in Africa; while two paintings contend for the same title within the novel as well, reflecting Rushdie’s obsession with the idea of the palimpsest, the work of art that overlays another. From Cochin we move to Bombay, which takes over as the city centre of the novel; and, after the Indian plot has run its course, we end up back in southern Spain, as if by a process of imaginative restitution, or recentring; like the rebalancing of a wheel. The novel is once again a family saga, the story this time of the doomed Zogoiby family. As with Shame, the text is once again prefaced with a family tree. It is a story of sexual infatuation and betrayal; of conquest, trade, and political intrigue; of religion and religious conflict; of generosity and understanding deformed by intolerance; of spiritual values corrupted by commerce. A story, significantly, that creates within itself (like a pearl) the opaque metaphor of its own making. J. M. Coetzee’s review perceptively identifies the specialized figure of ekphrasis as central to Rushdie’s project: ‘the conduct of narrative through the description of imaginary works of art.’3 The function of Rani Harappa’s eighteen shawls from Shame, reflecting the history of her husband and her times, is fulfilled here by the paintings of Aurora Zogoiby, Moor’s mother, which represent not only the micro-narrative of her family within the macro-narrative of her Indian world, but also the narrative of representation itself – the different styles and genres of painting that an evolving consciousness will come to utilize. And it is not only these paintings that operate in this way. There is a series of ancient blue tiles in the synagogue tended by Moor’s Jewish grandmother, ‘metamorphic tiles’ which themselves have narrative and prophetic qualities. ‘Some said that if you explored for long enough you’d find your own story in one of the blue-and-white squares, because the pictures on the tiles could change, were changing, generation by generation, to tell the story of the Cochin Jews’ (MLS 75–6). It 108 THE MOOR’S LAST SIGH is a novel, finally, that explores (with all the courage of selfinterrogation – a process that has, no doubt, been matured by Rushdie’s predicament) the ambivalence of our values in all these interlocking spheres. The first-person narrative by the main character, Moraes Zogioby, known as ‘Moor’, is itself (as we would expect) foregrounded in its technique. The ‘last sigh’ of the title implies the first cry at birth, Beckett’s vagitus, as well as the expiration. ‘I am what breathes. I am what began long ago with an exhaled cry, what will conclude when a glass held to my lips remains clear.’ It is also the breath with which we articulate words. ‘A sigh isn’t just a sigh. We inhale the world and breathe out meaning. While we can’ (MLS 53–4).4 A natural storyteller, Moor as it were breathes narrative. But his story is actually written under compulsion. The ‘story of [his] story’, as Henry James puts it,5 is that at the last stage of his life, in Spain, Moor is imprisoned by the demented painter Vasco Miranda, one of his mother’s former lovers and a jealous rival in art, who forces him to write his narrative. ‘Every day . . . he brought me pencil and paper. He had made a Scheherazade of me. As long as my tale held his interest he would let me live’ (MLS 421). A graphological Scheherazade, one should add, according to the Beckettian model: Molloy is provided with paper for the same purpose by ‘this man who . . . gives me money and takes away the pages’.6 And so Moor recreates in his cell the complex story of his family. He is the fourth child (and only son) of a prosperous mixed family from Cochin in (then) Portuguese Goa. The genetic admixture is important: Moor describes himself as ‘a high-born cross-breed‘, ‘a jewholic-anonymous, a cathjew nut, a stewpot, a mongrel cur . . . a real Bombay mix’. ‘Bastard’, he concludes; ‘I like the sound of the word’ (MLS 5, 104). The family fortune derives on the side of his mother, Aurora da Gama, a Christian, from generations in the spice trade; and on the side of his Jewish father, Abraham Zogoiby, from the illicit sequestration and secret sale of jewels housed in the blue-tiled synagogue. These jewels derive ultimately from Boabdil, king of Granada, who had given them to his Jewish mistress, from whom they have passed down through the Zogoiby family. It is the sale of these jewels that saves the firm from bankruptcy when it is threatened by destructive family feuding and the blockade during the 109 SALMAN RUSHDIE Second World War; but the jewels are handed over by Abraham’s mother only at a price. Rumpelstiltskin’s price: the life of Abraham’s first son, which is therefore surrendered to an intertextual bargain before he is born. The conduct of trade (which may be taken to include this sinister fairy-tale contract) is a major preoccupation in the novel, and the progressive compromises from the vision and energy of the early traders from Vasco da Gama onwards to the corrupt practices of Abraham Zogoiby himself – which eventually involve moneylaundering, drugs, prostitution, and arms dealing – are part of the overall theme of degeneration and betrayal. Moor is born in 1957, and his narrative takes us up to 1993, as he prepares for death: literally lying out on his tombstone, having nailed the sheets of his stolen narrative to doors and gateposts after his escape from Miranda’s madhouse, in an allusion to the publication of Martin Luther’s testament. What associates him with the authentic family tree of Rushdie’s fictional creations is that he is cursed to be a ‘magic child, a timetraveller’ (MLS 219), who grows and ages at exactly twice the normal speed. Thus he is born only four-and-a-half months after conception (though Rushdie also teases us, as elsewhere, with alternative parental possibilities), and his personal narrative of thirty-six years delivers him up a saddened and wizened septuagenarian. Moor learns about the earlier events in his dynastic story through oral tradition: by listening to the stories of his family and their friends and servants. His parents themselves, his three sisters (Ina, Minnie, and Mynah: to prepare for Moor), his uncle Aires and aunt Carmen, his mother’s lover Vasco Miranda, and the one-legged servant Lambajan, all piece together the earlier episodes. And there is, of course, the privileged evidence of his mother’s paintings, which provide a commentary on important events in the narrative – and have a further significance for the theory of representation, to which we shall return. Inevitably, for a trading family, the family fortunes are closely involved with public events. The novel includes episodes from the First and Second World Wars, from the political unrest in India during the 1930s, and later in the narrative we encounter again events that featured in Midnight’s Children: the tempestuous time of independence itself, partition, the language riots, Mrs Gandhi’s infamous 110 THE MOOR’S LAST SIGH emergency. But, although the Zogoiby family is therefore ‘handcuffed to history’ in a similar way to Saleem, and although Rushdie occasionally uses the same devices to achieve the parallelism (thus one of Moor’s sisters dies in the Bhopal disaster, and when Sanjay Gandhi is killed in a plane crash Moor tells us ‘I, too, was plunged towards catastrophe’ (MLS 274–6)), the historical details are sketched in much more incidentally here than in the earlier novel: history is not used as ‘scaffolding’ in the same way.7 In Midnight’s Children there was a genuine effect of ’split screen’ or double focus, whereas in The Moor’s Last Sigh Moor’s own story and the technique of his telling of it retain our attention much more continuously. The background is a more resonant one, composed of fairytale and folktale, epic and myth; literature and art and philosophy as well as history. It is ‘an Indian yarn’ (MLS 87), and Rushdie expects us to make all the formal concessions implied here. Once again, in the syncretist spirit, there are significant Shakespearian intertexts in the novel, this time mainly The Merchant of Venice and Othello. And, like the latter play, the novel is much more domestic in focus than any of Rushdie’s earlier works. It is this intimacy that generates an intensity of emotion that is also, perhaps, uncharacteristic. Elsewhere in Rushdie the macronarrative tends to put personal feeling into perspective, but here it is personal feeling that establishes the perspective according to which other things are judged.8 At the tormented centre of this personal feeling is Moor himself, the ‘magic child’ who has been singled out for spectacular disappointments in life: a series of exemplary betrayals that explain the regular references to himself as a Christ figure (he presents his story as a crucifixion from the first page). The first betrayal might be seen as that of nature itself, in his handicap, because not only is he condemned by his abnormal growth-rate to be a ‘time-traveller’ – which is as bad for living, as it is good for storytelling – but he is also born with a deformed left hand: fingers webbed and bunched into an ugly fist that serves him well in his days with Mainduck’s thugs in the Bombay underworld. The next betrayal is that by his ‘one true love’, Uma Sarasvati, an enigmatic figure who first reciprocates Moor’s love and then betrays him: to his friends, and ultimately to his parents. The final and most painful betrayal is that by his 111 SALMAN RUSHDIE parents themselves, who disavow him as a result of Uma’s destructive plot and refuse to see him from this point on: his mother, above all, ‘who never spoke to me, never made confession, never gave me back what I needed, the certainty of her love’ (MLS 432). The complicated detective-story plot takes over from this point, complete with hired snoops and contract killers; the note of parody is never far below the surface.9 Aurora is killed in a fall from the high terrace of her Bombay house, where each year on her birthday she has danced a defiant, secular ‘dance against the gods’ (MLS 315). Or was she pushed? And if so, by whom? Only at the end do we learn that her husband, Abraham Zogoiby, was responsible, Moor’s own father, who turns out with typical Rushdie hyperbole to be ‘the most evil man that ever lived’ (MLS 417). As the truth of the picture emerges, Moor is employed by his father’s business rival Mainduck in a campaign of violent reprisal (reminiscent more of Shame than Midnight’s Children) which reveals that corruption extends further than was ever imagined, implicating the very structures of government. But a familiar Rushdian apocalypse awaits the big players in this dubious game. There is an explosion that destroys whole buildings in the centre of Bombay, and in the confusion that follows Moor takes off for Spain to avoid arrest. Here, as if sleepwalking into the further ramifications of his own plot, he stumbles into Vasco Miranda’s mad world of art – from which he is only saved, at the end, by the fairy-tale splinter of glass that has been lodged in Miranda’s murderous heart. The narrative is deliberately pushed over the edge with parodic reworkings of other plots, constellated with allusions, and refracted through a series of stylistic variations. For Rushdie, this is how narrative works: by accretion, complication, parallelism, inversion. This is his architecture. But at the same time the narrative is intended to deliver something else. The Moor’s Last Sigh is powered by a nucleus of related ethical ideas, each of which bears closely on the other, and which may be said to subtend the moral preoccupations of the patriarch Francisco da Gama and his son (Moor’s uncle) Camoens. These relate to the nature of identity, both racial and personal; to the competition between ideas of singularity and multiplicity; and beyond this to the nature and truth of artistic representation. It 112 THE MOOR’S LAST SIGH is the engagement with identity, the shifting boundaries of the self, that gives the most direct access to these, associated as it is (here as in The Satanic Verses) with the fiction-making process itself. Underneath Rushdie’s narrative of Spanish India there runs a passionate desire for love and harmony: the transcendence of the single, isolated self in a love that, while being personal and sexual, is also imaginative and inclusive, passing out into the infinite. This ethical dimension is introduced by Francisco da Gama via a scientific theory explicitly derived from Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist: a science-fiction version of Stephen Dedalus’s forge for creating the conscience of his race, whereby a magnetic ‘Field of Conscience’ is maintained in the atmosphere in response to people’s behaviour on earth. Rather like an ethical ozone layer – though it has to be said big holes are blown in this before the end. And, just as Shelley reminded us that ethical behaviour begins with the ability to ‘put [oneself] in the place of another and of many others’,10 so too for Rushdie it is in the going beyond the self that we may discover our full human value. The extreme instance of this is in the idea of being flayed: literally, losing the distinguishing and separating skin in a ‘naked unity of the flesh’ (MLS 414). The image is introduced by Francisco’s daughter-in-law Carmen as an expression of sexual guilt that longs for ablation: ‘flay me flay my skin from my body whole entire and let me start again let me be of no race no name no sex’ (MLS 47). But it is taken over by Moor himself, associated with an anatomical illustration he has seen as a child: ‘When I was young I used to dream . . . of peeling off my skin plaintain-fashion, of going forth naked into the world, like an anatomy illustration from Encyclopaedia Britannica, all ganglions, ligaments, nervous pathways and veins, set free from the otherwise inescapable jails of colour, race and clan.’ This fantasy of self-forgetting is taken even further, he recalls, in ‘another version of the dream’ in which he would be able to peel away more than skin, and float free of the body altogether, becoming ‘simply an intelligence or a feeling set loose in the world, at play in its fields, like a science-fiction glow which needed no physical form’ (MLS 136). So far, so good; this reads positively, like a psychedelic trip. But there are bad trips too. A terrifying, negative version of the image occurs during Moor’s incarceration: ‘As roaches crawled and mosquitoes stung, so I felt that my skin was indeed 113 SALMAN RUSHDIE coming away from my body, as I had dreamed so long ago that it would. But in this version of the dream, my peeling skin took with it all elements of my personality.’ And here in the prison, forced to reflect, he perceives that the source of this annihilation is identical with the source of life: his mother. Hers is the real, psychological violence he translates into such physical terms: ‘And when he is flayed, when he is a shape without frontiers, a self without walls, then your hands close about his neck . . . he is farting out his life, just as once you, his mother, farted him into it’ (MLS 288). But the image returns in its positive form right at the end, in the lyrical culmination to the novel, a passage that reads almost like an epilogue, where Moor has ‘scrambled over rough ground ’ to sit on his own tombstone and reflect on the sum of experience that has brought him here: ’Thorns, branches and stones tore at my skin. I paid no attention to these wounds; if my skin was falling from me at last, I was happy to shed that load.’ The terms used here clearly refer to the narrative of Christ’s passion and death (immediately before this, the written sheets of Moor’s story are ‘nailed to the landscape in my wake’), just as Joyce alludes to this in the last paragraph of his story ‘The Dead’. The figure of the flayed man is also Christ whipped with thorns in the temple before his crucifixion, fulfilling this other system of reference. And, from his vantage point on the tombstone (which is both spatial and temporal), Moor looks out across the valley to the symbolic Alhambra, where the personal image is taken up in a broader, cross-cultural vision: the glory of the Moors, their triumphant masterpiece and their last redoubt. The Alhambra, Europe’s red fort, sister to Delhi’s and Agra’s – the palace of interlocking forms and secret wisdom, of pleasure-courts and water-gardens, that monument to a lost possibility that nevertheless has gone on standing, long after its conquerors have fallen; like a testament to lost but sweetest love, to the love that endures beyond defeat, beyond annihilation, beyond despair; to the defeated love that is greater than what defeats it, to that most profound of our needs, to our need for flowing together, for putting an end to frontiers, for the dropping of the boundaries of the self. (MLS 433) The intensely concrete and physical image of flaying (which may contain a reference to Swift’s livid image of the woman flayed from A Tale of a Tub, as well as to Beckett’s character Lemuel who is ‘flayed alive by memory’ in Malone Dies11) intersects with the idea of the plurality and malleability of the 114 THE MOOR’S LAST SIGH personality that we have met elsewhere in Rushdie, and which is treated if anything more systematically in this novel. Early on, the personality of his grandfather provides Moor with an example: ‘To me, the doublenesses in Grandfather Camoens reveal his beauty; his willingness to permit the coexistence within himself of conflicting impulses is the source of his full, gentle humanness’ (MLS 32). Francisco’s ‘Fields of Conscience’ have at least forged his son’s moral vision; a realization through fictional character of the notion of ‘negative capability’ which Keats identified in Shakespeare; ‘when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.’12 The desire for transcendence associated with this image is felt both personally (in love) and politically, in a vision of culture. Moor provides the relevant meditation on love whilst in prison, still suffering from the trauma of Uma Sarasvati’s death and his mother’s betrayal. I wanted to cling to the image of love as a blending of spirits, as mélange, as the triumph of the impure, mongrel, conjoining best of us over what there is in us of the solitary, the isolated, the austere, the dogmatic, the pure; of love as democracy, as the victory of the no-man-is-an-island, two’s company Many over the clean, mean, apartheiding Ones. (MLS 289) The terminology used here clearly moves beyond personal love to a more comprehensive vision of understanding. This vision has been articulated earlier by the idealistic Camoens to his daughter Belle. He invites her to imagine, and to help create, ‘a new world, Belle, a free country, Belle, above religion because secular, above class because socialist, above caste because enlightened, above hatred because loving, above vengeance because forgiving, above tribe because unifying, above language because many-tongued, above colour because multi-coloured . . . ’(MLS 51). Not surprisingly, Camoens’s new world has so far failed to materialize. But it is symbolically represented in Rushdie’s novel by the culture of the fabulous Alhambra, where Europe met Africa, Christianity and Judaism met Islam, in pluralist embrace, a rare instance of racial and religious tolerance. The Moor’s Last Sigh is partly an elegy for that culture, and for the very ideals it represented – the more movingly so for the sense the novel conveys of the impssibility of 115 SALMAN RUSHDIE recreating anything resembling it in twentieth-century India; or, for that matter, of rediscovering its rare virtues anywhere else in the modern world. Such virtues depend upon a philosophical preference for the plural over the singular, the dialectical over the monologic; a preference that is most consistently expressed through Aurora’s paintings. It is the ‘torrential reality of India’ (MLS 45) that awakens her art in the first place, and when Camoens sees the murals she has painted during her solitary confinement he exclaims: ‘But it is the great swarm of being itself.’ Figures from ancient and modern history consort with hybrids from her own imagination, ‘half-woman half-tiger, half-man half-snake . . . seamonsters and mountain ghouls’. Vasco da Gama is there, claimed as an ancestor: Aurora had composed her giant work in such a way that the images of her own family had to fight their way through this hyperabundance of imagery, she was suggesting that the privacy of Cabral Island was an illusion and this mountain, this hive, this endlessly metamorphic line of humanity was the truth . . . (MLS 59–60) Whatever political and personal distractions intervene (and many do), this is the dominant form of her art: ‘the mythic– romantic mode in which history, family, politics and fantasy jostled each other like the great crowds at V.T. or Churchgate Stations’ (MLS 203–4). This is what we might call the Bombay Alhambra, which can only be represented in a mode that includes but goes beyond realism; as Vasco Miranda succinctly declares at one point, ‘a canvas is not a mirror’ (MLS 158). And the principles of Aurora’s painting are intended to reflect Rushdie’s own practice as a writer. The rich invocation of the Spanish and Portuguese past in the novel, the documentation of the political instability of the inter-war years in India, and the description of modern Bombay (‘that super-epic motion picture of a city’ (MLS 129) ) match the detailed description of the paintings, words aspiring to iconicity, within the figure of ekphrasis previously identified. The paintings at this stage, in her mid-career, are devoted to the effacement of dividing lines: ‘the dividing lines between two worlds, became in many of these pictures the main focus’; water, land, and air are allowed to merge as Aurora proposes her 116 THE MOOR’S LAST SIGH own ‘political’ version of this blending: ‘Call it Mooristan . . . Call it Palimpstine.’ And the political significance is underlined, as Rushdie develops and exploits the possibilities of his selfreflexive commentary: ‘In a way these were polemical pictures, in a way they were an attempt to create a romantic myth of the plural, hybrid nation; she was using Arab Spain to re-imagine India’ (MLS 226–7). As is implied here, the idea of the palimpsest provides a key to the novel: both the literal palimpsest (exampled by Aurora’s painting ‘The Moor’s Last Sigh’, and also, as it happens, by an actual portrait of Rushdie’s mother13) and the metaphorical palimpsest, as a ‘layering’ or re-presentation or disguise of any other kind. Rushdie makes use of this metaphor to describe the corrupt commercial practices of Abraham Zogoiby in a passage which has a more general epistemological bearing – recalling as it does the ‘permeation of the real world by the fictional’ in the earlier ‘Ruby Slippers’ story from East, West. The city itself, perhaps the whole country, was a palimpsest, Under World beneath Over World, black market beneath white; when the whole of life was like this, when an invisible reality moved phantomwise beneath a visible fiction, subverting all its meanings, how then could Abraham’s career have been any different? How could any of us have escaped that deadly layering? How, trapped as we were in the hundred per cent fakery of the real, in the fancydress, weeping-Arab kitsch of the superficial, could we have penetrated to the full, sensual truth of the lost mother below? How could we have lived authentic lives? (MLS 184–5). It is one of the remarkable features of The Moor ’s Last Sigh that these moral ideas are not only entertained but tested to destruction in the novel. This trial of the limits is conducted through the agency of Uma Sarasvati, the novel’s contradictory and equivocating angel–devil. It is Uma whom Moor falls in love with, and who teaches him love’s transcendent value; only here can he perceive that love overbalances truth, only here are his belief systems fundamentally (and creatively) challenged: ‘I do not believe it; I believe it; I do not believe; I believe; I do not, I do not; I do’ (MLS 251–2). But having established her power Uma betrays him in the cruellest way possible – sending his parents a tape-recording of their lovemaking, during which she has tempted him to say unforgiveable things. In the sequel she 117 SALMAN RUSHDIE actually tries to kill him, in a trick suicide pact which is bizarrely bungled and results in her own death when two tablets are swapped after a clash of heads (MLS 281): one thinks of the switched swords in the last scene of Hamlet. And following up Rushdie’s own references to Keats, one might suggest that Uma is more chilling than ‘La Belle Dame Sans Merci’, the classic femme fatale, being more a kind of postmodern Lamia – the snake disguised as a woman. She herself has ‘no ‘‘authentic’’ identity’ (MLS 266), and so, like a cold window distilling vapour, is able to drain other people of theirs. It is significant that when the Zogoiby family meets her at the racecourse ‘every one of us had a fiercely held opinion about her, and many of these opinions contradicted each other utterly and were incapable of being reconciled’ (MLS 243). As such, her very embodiment of plural identity reverses its value – a perception Moor records as a ‘bitter parable’ in which ‘the polarities of good and evil were reversed’: ‘For in the matter of Uma Sarasvati it had been the pluralist Uma, with her multiple selves, her highly inventive commitment to the infinite malleability of the real, her modernistically provisional sense of truth, who had turned out to be the bad egg; and Aurora had fried her . . . ’(MLS 272). For Moor–Othello chaos has come again; his intellectual as well as his emotional world is turned upside-down. Uma ‘showed me the truth’, he says, but it is the kind of truth that is worse than lies – or which confuses these categories in a more powerful drug: ‘Whoever and whatever she had been, good or evil or neither or both, it is undeniable that I had loved her’ (MLS 241, 281). And for Aurora too there is a convulsion, in her art as well as her politics. From this point on she abandons her hybrid forms, and comes under the influence of the Hindu activist Minto with his dangerous separatist ideas: ‘Aurora, that lifelong advocate of the many against the one, had with Minto’s help discovered some fundamental verities’ (MLS 272). In her earlier paintings, her son Moraes has served for Aurora as a symbol for India itself; he has been the centre of her pictorial narrative. ‘And I was happy to be there, because the story unfolding on her canvases seemed more like my autobiography than the real story of my life’ (MLS 227). But this very symbol is now invalidated and reversed, in the ‘Moor in Exile’ sequence; the personal and the political have been simultaneously betrayed in art. 118 THE MOOR’S LAST SIGH And the Moor-figure: alone now, motherless, he sank into immorality, and was shown as a creature of shadows, degraded in tableaux of debauchery and crime. He appeared to lose, in these last pictures, his previous metaphorical rôle as a unifier of opposites, a standard-bearer of pluralism, ceasing to stand as a symbol – however approximate – of the new nation, and being transformed, instead, into a semi-allegorical figure of decay. The philosophical conclusion comes in what follows, proof of a dismaying contamination of cultural ideals by personal jealousy and disappointment. ‘Aurora had apparently decided that the ideas of impurity, cultural admixture and mélange which had been, for most of her creative life, the closest things she had found to a notion of the Good, were in fact capable of distortion, and contained a potential for darkness as well as for light.’ We are returned to the perilous depths of The Satanic Verses, where human behaviour becomes frighteningly unreliable and ambiguous, as different motives come into view. Her son now appears to Aurora as a fleur du mal; and we have a quotation from Baudelaire to make the point (MLS 303). The renegade painter Vasco Miranda also plays his part in this process of destruction from within. Destroyed by his jealousy of Aurora’s talent, he has sold out his own art to commerce, producing a readily consumable ‘airport art’ that mischievously alludes to Salvador Dali’s facile surrealism. But he takes his surname, after all, from Shakespeare’s wide-eyed heroine in The Tempest, with her wonderment at the promise of new worlds; and, true to this suggestion, he promises on his removal to Spain to recreate ‘in his ‘‘Little Alhambra’’, the fabulous multiple culture of ancient al-Andalus’ (MLS 398). But his ‘new society’ turns out to be a megalomaniac’s prison; and he it is, in the novel’s extraordinary penultimate scene, who shoots the lost portrait through the heart for it to bleed with the life blood of the Japanese artist whom he has employed to work on its restoration. She herself plays a symbolic role, both as the disbelieving auditor and innocent victim of Moor’s story, and also, through her very name, as a kind of good angel – the spirit of art, and the binding powers of language. ‘Her name was a miracle of vowels. Aoi Uë: the five enabling sounds of language . . . constructed her’ (MLS 423). So both Uma and Vasco contribute to the novel’s real tragedy, ‘the tragedy of multiplicity destroyed by singularity, the defeat of the Many by the One’ (MLS 408). 119 SALMAN RUSHDIE But there is another, more undermining level of scepticism loose in the novel. It is not only Aurora herself, but her critics (including her son) who are entitled to a judgement of her paintings; and so Moor’s developing awareness of the potential for falsity in his mother’s pictures – reciprocating her judgement of him – opens up another series of intriguing questions. Although Moor feels at one point, as we have seen, that her pictorial narrative ‘seemed more like [his] autobiography than the real story of [his] life’, he comes to realize, later, that those of his mother’s paintings which are motivated by her jealousy of Uma are themselves perverse, and ‘did not necessarily bear the slightest connection to events and feelings and people in the real world’ (MLS 247). This is a disabling realization for him, as the subject of these paintings, but also for us, as readers of Rushdie’s novel; because the question is intended to destabilize the paintings’ frame-text in the novel itself. If the paintings can tell lies, then so can any art; and this may explain why at several points in the novel Moor is careful himself to question the truth of elements included in his own narrative. ‘I have grave doubts about the literal truth of the story’ of the painting The Moor’s Last Sigh, he tells us; and, whereas he goes on to assure his reader that ‘of the truth of these further stories there can be no doubt whatsoever’, he adds, in deference to the omnipotent reader, ‘it is not for me to judge, but for you’ (MLS 79, 85). We have to set alongside this the deliberate provocation whereby Rushdie mixes in historical materials with his fiction: as when he implies that Aurora might have had an affair with Nehru – quoting in his text from published letters between Nehru and Mrs Gandhi, which are duly cited in the Acknowledgements; and when he makes a knowing allusion to the critic Homi Bhabha in the name of a purchaser of one of Aurora’s paintings (MLS 117–18, 435; 419). We also have to consider the implications of inviting characters from his other novels into this one – a manœuvre that might be considered either intriguingly self-reflexive or simply self-indulgent. (In either case, Rushdie would be familiar with such textual migration in the work of the eighteenth-century novelists: we find examples in both Fielding and Smollett). Aadam Sinai turns up from Midnight’s Children to be adopted by Abraham Zogoiby in preference to his own son, Moor; and Zeeny Vakil from The Satanic Verses appears in her role as critic of 120 THE MOOR’S LAST SIGH Aurora’s paintings – and gets killed for her pains, in the cataclysmic explosion at the end. This intertextual trespass poses a curious question: are we meant to wonder what effect this death might have on the Saladin Chamcha in whose company she was left at the end of the earlier novel? It is not only the discourse of art but the ‘ordinary’ narrative discourse within the novel that is hedged around with doubts and hesitations and uncertainties. ‘It is difficult for me, after all these years, to know what to believe,’ Moor confesses as he writes out his story – a sentiment shared by Aoi Uë as she listens to him. It is ‘the old biographer’s problem: even when people are telling their own life stories, they are invariably improving on the facts’ (MLS 135). Ironically, Zeeny Vakil says ‘I blame fiction’ for the return of religious tensions: ‘the followers of one fiction knock down another popular piece of make-believe, and bingo! It’s war’ (MLS 351). Moor himself, unable to make sense of the revelation that it was his own father who killed his mother – a revelation made immediately before Miranda’s shooting of Uë – admits, ‘I was lost in fictions, and murder was all around’ (MLS 418). Moor has retained his truth claim to this point, almost like a fetish. ‘I must peel off history, the prism of the past,’ we find him saying one-third of the way through the novel. ‘It is time for a sort of ending, for the truth about myself to struggle out from under my parents’ stifling power’ (MLS 136). Later, as he faces up to Uma’s instability, he forces himself to realize: ‘This is not a game. This is happening. It is my life, our life, and this its shape. This its true shape, the shape behind all shapes, the shape that reveals itself only at the moment of truth.’ But later still there are still darker truths to acknowledge. But now I knew everything. No more benefits of doubts. Uma, my beloved traitor, you were ready to play the game to the end; to murder me and watch my death while hallucinogens blew your mind. . . . It must be the plain truth; everything about Uma and Aurora, Aurora and me, me and Uma Sarasvati, my witch. I would set it all down, and surrender myself to his sentence. (MLS 280, 321–2) Even as he is ‘writing for his life’ at Miranda’s direction – awaiting his captor’s ‘sentence’ – his obsession with the truth of his narration invites us to look over the novelist’s shoulder, responsible as he is for his character’s act of writing. We are 121 SALMAN RUSHDIE invited to review the novel we have been reading: ‘On my little table in that death-cell young Abraham Zogoiby wooed his spice-heiress and aligned himself with love and beauty against the forces of ugliness and hate; and was that true, or was I putting Aoi’s words into my father’s thought-bubble?’ Carmen da Gama is just ‘a creature of my mind’: as are all the characters, ‘as they must be, having no means of being other than through my words’ (MLS 425). We accompany the writer as he sails close to the wind of his intention, confiding in what he deferentially calls ‘my omnipotent reader’ his authorial uncertainties, and asking for our understanding (MLS 145).14 Miranda’s accomplices the Ramirez sisters tell Moor, on his predestined arrival at Benengeli, ‘You have come on a great pilgrimage. . . . A son in search of his lost mother’s treasures’ (MLS 400). He never finds or, at least, never retrieves the lost painting; no more did Rushdie himself, in the actual family incident on which this episode is also based. But he does find the greater treasure of himself, as has been promised from the outset: ‘the story which points to me. On the run, I have turned the world into my pirate map, complete with clues, leading X-marks-the-spottily to the treasure of myself’ (MLS 3). Walter Benjamin observed, ‘Not only a man’s knowledge or wisdom, but above all his real life – and this is the stuff that stories are made of – first assumes transmissible form at the moment of his death.’15 Moor writes his story at the point of Vasco Miranda’s gun, and takes the pages, literally, to his grave: ‘I have used the last of my strength to make this pilgrimage’ (MLS 422–3). It is a pilgrimage that ends with a positive vision, with the promise of resurrection and renewed hope – addressed appropriately enough, we may feel, through its carefully chosen cross-cultural references, to Rushdie’s expectant, worldwide audience. The world is full of sleepers waiting for their moment of return: Arthur sleeps in Avalon, Barbarossa in his cave. Finn MacCool lies in the Irish hillsides and the Worm Ouroboros on the bed of the Sundering Sea. Australia’s ancestors, the Wandjina, take their ease underground, and somewhere, in a tangle of thorns, a beauty in a glass coffin awaits a prince’s kiss. See: here is my flask. I’ll drink some wine; and then, like a latter-day Van Winkle, I’ll lay me down upon this graven stone . . . and hope to awaken, renewed and joyful, into a better time. (MLS 433–4) 122 8 Interchapter: Twelve years later... This book on Rushdie’s fiction, first published in 1999, borrows a device from fiction itself to bring the story (or the commentary on the stories) up to date. It is now 2011; by which time the author has celebrated his 60th birthday, published four further novels, moved to his third continent, and seen other significant changes in his life – not least, becoming in 2007 Sir Salman Rushdie, thus lining himself up beside the fictional father-figure from The Ground Beneath Her Feet, the ennobled anglophile Sir Darius Cama. One is sure Sir Darius would have been pleased (and we overlook the fact that in the novel itself Sir Darius is later disgraced, and returns the citation for his knighthood). Meanwhile this novel, anticipated at the end of the last chapter, The Ground Beneath Her Feet, was published in 1999, and partly because of its upfront subject matter – rock music – and partly because of its relocation – via Bombay and London to America – enjoyed a somewhat mixed critical reception. (More on that in a moment; I must not get ahead of myself.) Later that same year Rushdie met the actress and model Padma Lakshmi. In 2000, having eventually been granted a visa, he travelled with his son Zafar to India, for a kind of reconciliation with the country ‘after a gap of twelve-and-a-half years’.1 At the end of the same year he expressed his frustration with life in London and moved to New York.2 The novel Fury was published in 2001, with the Empire State Building impaling bright clouds on the cover; just weeks before the Twin Towers come tumbling down in Manhattan. This time, the novel was greeted in some quarters with frank hostility. One reviewer went so far as to say it was time for Rushdie to be ‘relegated’ to a second division of 123 SALMAN RUSHDIE novelists, prompting a spirited defence by John Sutherland of a Rushdie who had been unfairly victimized by the press.3 2003 sees a second collection of Rushdie’s essays, Step Across This Line. These essays are from the previous ten years, and include many written towards the end of this decade for the New York Times and the New Yorker, which together give some idea of Rushdie’s increasing identification with his newly-adopted country and its values. (It is not for nothing that the volume is dedicated to Christopher Hitchens.) Again, critics underline the ideological shift from the earlier direct criticism of America (most explicit in The Jaguar Smile) to that of an essay such as ‘Anti-Americanism’, where he turns on his earlier self, criticizing the ‘hypocrisy’ of the rest of the world, ‘hating most what it desires most’, and arguing that ‘we need the United States to exercise its power and economic might responsibly’ (SAL 399–400). Anshuman Mondal traces this fault-line in his essay ‘The Ground Beneath Her Feet and Fury: The reinvention of location’, remarking: In an ironic instance of the hyperreality that he elsewhere critiques, Rushdie’s later ‘writing self’ seems to have merged with that simulacrum of him that had been deployed in polarised debates about the ‘Rushdie affair’. Writing from within the celebrity glasshouse, his work is now as much written from the American centre as about it, as much a reinforcement of his own celebrity as an indictment of the culture that sustains it, as much an articulation of globalisation as a critique of it. The result is a chronic ambivalence.4 In 2004, his marriage to Elizabeth West (mother of his second son Milan) being previously dissolved, Rushdie marries Padma Lakshmi, an actress and model half his age. There is the inevitable glare of publicity; there are invitations to the White House, presentations, parties. Rushdie appears as himself in a film; his life starts to resemble what he has often described, life as a performance of itself.5 Shalimar the Clown is published in 2005, the novel turning out to be not just about the trials of Kashmir but also exposing the uneasy dialogue between India and America. Two years later, Rushdie is offered and ‘humbly accepts’ a knighthood; this episode prompts some tart articles in the press and contributions online, and marks a further shift in how Rushdie is now perceived by his readers, with an increasing polarization between the view that he is still our greatest novelist (a view seemingly confirmed by the ‘Best of Booker’ 124 INTERCHAPTER award for Midnight’s Children in 2008), and a frankly defamatory assessment which sees Rushdie as a spent force, his writing mired in self-regard, equivocation and complicity. Priyamvada Gopal for example laments that whereas Salman Rushdie was motivated by an ‘uncompromising ethical vision’, Sir Salman has now ‘abdicated his own understanding of the novelist’s task as ‘‘giving the lie to official facts’’’ and so his recent fiction has deservedly ‘disappeared into a critical wasteland’.6 The next month, Rushdie’s marriage to Padma Lakshmi ends in divorce, and he declares in an interview that ‘marriage is no longer necessary’. In 2008 he publishes The Enchantress of Florence, fruit of Rushdie’s long-standing interest in the city and its more celebrated sons (and daughters). Then in 2010 there is a second children’s story, Luka and the Fire of Life, written, Rushdie tells us, because his eleven-year-old son Milan felt that he should have his own story, just as Haroun had been dedicated to Zafar ten years previously. Finally, there seem to be some signs of a shift away from prose fiction altogether, as Rushdie engages to write a TV series, ‘in the belief that quality TV drama has taken over from film and the novel as the best way of communicating ideas and stories’.7 Now read on. 125 9 The Ground Beneath Her Feet The Ground Beneath Her Feet is that paradoxical thing, a novel about music and photography. Framed, filmed, and with full surround sound, it issues directly from – enacts, and tries to be part of – that thunderous, subversive, sexual, and heteroglossic musical scene that began in the late 1950s, rode the waves for two or three decades, and still keeps us afloat on its diversifying currents. Rushdie has said it is ‘the sound-track of my life’.1 In order to keep up with its subject, and its characters, the novel is written in a style that James Wood has unkindly but not unfairly described as ‘hysterical realism’,2 a development from Rushdie’s earlier and still recognizable style, but ratcheted up by several degrees of hyperbole. It is louder, more gesticulatory, more high-pitched, more vulgar, and more omnivorous. Five pages into the first chapter, we are told by the excitable narrator Rai that ‘the legendary popular singer Vina Apsara’ (whom we have met in the first sentence) ‘looked stretched, unstable, too bright, as if she were on the point of flying apart like an exploding lightbulb, like a supernova, like the universe’ (GBF 7). The dilating scale is proclaimed unashamedly, and indeed this first proleptic chapter functions as an all-action ‘trailer’ to the novel which follows, introducing characters and themes with a clashing of symbols, an earthquake, and other big brassy notes. Newspapers ‘with their shrieking ink’ attend on ‘the whole appalling menagerie of the rock world’, written up by Rai in Rushdie’s familiar ‘Hug-me, Hindu Urdu Gujarati Marathi English: Bombayites like me were people who spoke five languages badly and no language well’ (GBF 4,11,7). 126 THE GROUND BENEATH HER FEET But though he evidently frets here within its archaic limitations,3 Rushdie has not quite forgotten that he is writing a novel; and there is plenty of literary superstructure to remind us of the fact. We are in Mexico, and it is Lawrence’s plumed serpent Quetzalcoatl that writhes in the first paragraph. Vina’s death deprives her ‘of the right to follow her life’s verses to the final, fulfilling rhyme’ (GBF 5). Her deceased one-night stand, we are told, was speaking Orcish, ‘the infernal speech devised for the servants of the Dark Lord Sauron by the writer Tolkien’; whose own rhyme, ‘One ring to rule them all . . . ’ is then dutifully quoted (GBF 5,6). Gluck’s Orfeo is appellated in Rai’s appalling pizza-register (’Happy it up, ja! – Sure, Herr Gluck, don’t get so agitato’). We are told of Vina’s own reading: Enid Blyton’s Faraway Tree series (GBF 12,16). And then we get the real thing, as Rai descends with trepidation (and with Virgil) into ‘this underworld of ink and lies’; ‘at the gate of the inferno of language, there’s a barking dog and a ferryman waiting and a coin under my tongue for the fare’. It hardly seems to be the same Rai who asks us, ‘Do you know the Fourth Georgic of . . . P. Virgilius Maro?’ and who then goes on to inform us about Aristaeus the beekeeper, who tells the story of Orpheus and Eurydice in Virgil’s poem (GBF 21). The superstructure is in place; Rai’s own name is made of the first three letters of Aristarchus;4 this chapter is called ‘The Keeper of Bees’, and the bees are identified with photographs. Drawing back further, we can appreciate that the structuring of the novel into eighteen chapters is no doubt a homage to Joyce and the structure of Ulysses, with the first chapter as prologue, and the last three chapters (after the death of Vina) serving as a sort of epilogue; and also in some ways as a decompression chamber, setting us down in the ordinary, recognizable world. Another Joycean reflex; though it must be said this is hardly typical of the novel as a whole, which reverberates to other rhythms. But at the level of presentation, we can perceive that the multilayeredness of the narrative, with its recurrence of phrases, refrains, motifs, and its network of allusions, suggests an updating of the celebrated Joycean mosaic to register late twentieth-century culture. And when we remember that Joyce himself was fascinated by the early cinema, and that what were long read as newspaper headlines in the Aeolus chapter are now better understood as 127 SALMAN RUSHDIE screen captions, then we can concede that the mosaic was ready to be reassembled. As is implicit in these introductory remarks, one cannot possibly do justice to the scale and complexity of Rushdie’s narrative without providing a summary of some kind, and I will attempt to provide this, with a light critical commentary, before passing on in the second part of the chapter to a more developed engagement with critical questions prompted by the novel. We need at the outset to be formally introduced to Rushdie’s narrator, ‘me, Mr Umeed Merchant, photographer, a.k.a ‘‘Rai’’’ (GBF 5). His is the perspective we have to rely upon for our access to the story, and (though Rushdie sits on his shoulder) his is the style in which it is garrulously and uninhibitedly delivered. Whatever we ourselves may think, Rushdie has confessed that for him, ‘one of the things that was most pleasurable in writing the book was having him come alive on the page and begin to speak. I loved his voice’.5 Not least, at some points – especially towards the end – he shoulders himself forward as a participant in the events he is describing and even makes off with his own happy ending. Rai is, as he has told us, a photographer, a ‘shutterbug ’, an ‘image stealer’, and his profession provides Rushdie very conveniently with a whole range of visual images and metaphors that frame the novel and are used for the articulation of its themes. What Rai is entrusted with is the story of two Indian rock stars, Ormus Cama and Vina Apsara, who – we are invited to believe, in a provocative gesture of historical and cultural inversion – have themselves magically anticipated western popular music, in a kind of unlikely acoustic prequel. They are the best, the brightest, the most unforgettable; everyone loves them, and (in their way) they love each other. But their way is the modern way of celebrity, cursed with a self-destructiveness that expresses itself first in India, then in Europe, and finally in America, where they both meet their deaths: she in an earthquake in Mexico whose seismic foreshocks – and aftershocks – are felt throughout the novel, and he later shot, John Lennon-like, in New York by a woman who could well be the ghost of Vina herself, inviting Ormus to join her in the other world he has so long hungered for. This late- and larger-thanlife picaresque narrative (because if we replace the picaro with 128 THE GROUND BENEATH HER FEET the celebrity, the episodic journey structure is much the same) is grafted onto the Orpheus myth, whose fatal example functions as another leitmotiv; and whose many versions, ancient and modern, poetic and operatic, allow Rushdie to play his own variations on the theme. But it is a measure of Rushdie’s ambition in this long novel (at 575 pages, it is longer even than the expansive Satanic Verses) that this is only one in a complex series of references, allusions and parallels, explicit and oblique, from literature, music, film, photography, and of course the ground of these art forms in history itself: especially modern history – we are singed here with ‘the white heat of the present tense’ (GBF 291). It is through this high-powered and multilayered narrative that Rushdie aims to encapsulate and deliver our modern world in all its seductive and degenerate splendour. The first proleptic chapter ended with Rai bracing and telling himself: ‘Begin’ (GBF 22). And at the beginning proper we are introduced to two Bombay families, both alike in dignity; Rai’s own parents, the Merchants, and the Camas, Sir Darius (an ennobled anglophile) and Lady Spenta. The Merchants first meet each other, and the two couples are introduced, on the day of Ormus Cama’s birth, which is announced with a familiar gesture: Ormus Cama was born in Bombay, India, in the early hours of May 27, 1937, and within moments of his birth began making the strange, rapid finger movements with both hands which any guitarist could have identified as chord progressions. (GBF 23) His hours-older twin brother Gayomart dies in the same childbed. Symmetry insists that the Camas ‘already had a fiveyear-old pair of dizygotic male twins, Khusro and Ardaviraf, known to one and all as ‘‘Cyrus and Virus’’’, who feature along with dead Gayo in their brother’s story. Virus as a child is struck by a cricket ball driven by his father and deprived of speech, retreating into ‘the mystery of inner space’, while the repentant Darius gives up cricket (and conversation) for studious application to ‘the relationships between the Homeric and the Indian mythological traditions’ (GBF 41). The trials of this unhappy family continue when Cyrus tries to suffocate his baby brother Ormus (whom he blames for the cricketing accident), and spends the rest of his strange life in custody, until he escapes 129 SALMAN RUSHDIE and murders his father; while Ormus is shadowed by Gayomart, as if in preparation for his own career. It is at this point – as it happens, in September 1939 – that a sheet of newspaper blows into Darius’s window, bringing with it ‘the stink of the real world’ (GBF 44). The narrator is not even born yet, and so his role has not really begun; we are temporarily in the hands of an omniscient narrator, and the device is typical of how Rushdie takes us back into the toils of history, which will condition his characters’ lives. Rai is ten years younger than Ormus, making him as old as new India, and as one Saleem Sinai, whom we remember from Midnight’s Children; and coincidentally as old as Rushdie himself. He claims his own role in the narrative when as a small boy he meets and falls in love with the teenage Vina Apsara on Bombay’s Juhu Beach. This is in the context of a confrontation with Piloo Doodhwala, a devious businessman (who is destined for satirical analysis later in the novel) and Rai’s upright father, in consequence of which Vina comes to live with Rai’s parents. Young Rai sees Vina as a kind of ‘Cinderella of Troy’ – his system of reference coming from Hawthorne’s Tanglewood Tales, among other sources – and from this moment he is captivated by her, setting her up as his absolute standard of value. ‘When I met Vina at the beach, I knew for the first time how to measure my worth. I would look for my answers in her eyes’ (GBF 69,75).6 There are other devices on display as the narrative unfolds; Rai/Rushdie’s advice to himself not to get ‘too far ahead of my tale’, repeated proleptic gestures (’Ormus Cama did not sing again for fourteen years’) and simple resolutions confided to the reader: ‘I must briefly halt my runaway bus of a narrative’ (GBF 36,47,86). These are familiar to any reader of Rushdie, as reflexes of his storytelling. More elaborate are the two paragraphs that conclude chapter 3, ‘Legends of Thrace’, where, the day after Ormus has arrived at his parents’ door in pursuit of Vina, Rai bids farewell to his childhood happiness and anticipates trials to come: It was the beginning of the end of my days of joy, spent with those Thracian deities, my parents, amid legends of the city’s past and visions of its future. After a childhood of being loved, of believing in the safety of our little world, things would begin to crumble for me, my parents would quarrel horribly and die before their time. 130 THE GROUND BENEATH HER FEET But Rai’s anticipation does not stop there. In a surprising move which leaps to the very end of the novel, dilating the adverb ‘now’ and as it were short-circuiting the story, he continues: Now there is at last a new flowering of happiness in my life. (This, too, will be told at the proper time.) Perhaps this is why I can face the horror of the past. It’s tough to speak of the beauty of the world when one has lost one’s sight . . . hard to write about love, even harder to write lovingly, when one has a broken heart. (GBF 84–5) Chapter 4, ‘The Invention of Music’, sets the narrative on its adult trajectory, and moves back into the hyperbolic register which is the verbal parallel to Ormus’s career. It is here that Rai as acolyte makes his bid to establish Ormus’s genius; and the paragraph in which he does so is deliberately pitched to an extreme, as if to silence any doubts. If I say that Ormus Cama was the greatest popular singer of all, the one whose genius exceeded all others, who was never caught by the pursuing pack, then I am confident that even my toughest-minded reader will concede the point. He was a musical sorcerer whose melodies could make the city streets begin to dance and high buildings sway to their rhythm, a golden troubadour the jouncy poetry of whose lyrics could unlock the very gates of Hell; he incarnated the singer and songwriter as shaman and spokesman, and became the age’s unholy unfool. There are immediately problems here as the reader (toughminded or not) recognizes the narrator’s irony at the same time as being required to accept his claims – otherwise, the story of an Indian Orpheus is simply not going to work. And this irony is underlined by a dismissive reference further down the same page to ‘the fame of a young truck-driver from Tupelo, Miss., born in a shotgun shack with a dead twin by his side’: one Jesse Garon Parker, who will become none other than Elvis Presley; though it is the rule of Rushdie’s alternative world that this obliterating name cannot be mentioned, for fear of collapsing the fiction.7 Rai can at least protest that he is not making all this up, since he has Ormus’s own word to go on: But by his own account he was more than that; for he claimed to be nothing less than the secret originator, the prime innovator, of the music that courses in our blood, that possesses and moves us, wherever we may be, the music that speaks the secret language of all 131 SALMAN RUSHDIE humanity, our common heritage, whatever mother tongue we speak, whatever dances we first learned to dance. (GBF 89) Of course, there is no such music, nor could there be; but never let it be said that Rushdie understates his case. This introduction is followed by an account of the first meeting of Ormus and Vina in the Rhythm Center music shop; an account which later commentators are allowed to have challenged as apocryphal, though we have it given in some detail here (GBF 92–4). And once Ormus and Vina are an ‘item’, Rai has to switch into a new series of superlatives. Sometimes I thought of Ormus and Vina as worshippers at the altar of their own love, which they spoke of in the most elevated language. Never were there such lovers, never had feelings of such depth, such magnificence, been felt by other mortals . . . But mortals they are not; it is the condition of all such descriptions, as they occur throughout the novel, that they lean on identification with the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. And this is a further dimension of the problem noted above; we as readers are stranded somewhere between Mount Olympus and Tin Pan Alley, not knowing at what value to take the claims to which the narrative is committed. Fortunately for the lovers themselves (and for their future career), Vina herself has no such qualms: From the beginning, Vina accepted Ormus’s prophetic status without question. He claimed to be the true author of some of the most celebrated songs of the day, and he did so with such uncontrolled intensity that she found she had no option but to believe him. (GBF 93,94) As we don’t, either, if we wish to continue reading. This is the nature of the contract that Rushdie requires of us in this novel: a suspension of disbelief so total, that anything goes; everything between heaven and hell (that is, on earth) may be reinvented. Ormus and Vina invent themselves; they are ‘two bespoke identities, tailored for the wearers by themselves’; we are simply expected to assist, admiringly, at the ritual. Nor is this the limit of the provocation. Because in order to maintain his fiction, Rushdie requires us also to accept, and ‘remember’, an alternative history of popular music over the last forty years. 132 THE GROUND BENEATH HER FEET ‘It was an amazing proposition: that the music came to Ormus before it ever visited the Sun Records studio or the Brill Building or the Cavern Club’ (GBF 95–6). ‘Now my story begins to strain in opposite directions’ confesses Rai at this point, forwards into the fatal relationship and backwards into Vina’s past in Chickaboom, in small-town America. She was born during the Second World War, daughter of a Greek-American called Helen and a ‘sweet-talking Indian’ who abandons the family ‘after Nagasaki’ (wars stalk this Helen too) and because he had ‘revised his sexual practices’ (GBF 101– 2). Helen is taken up by a kindly American, John Poe, who raises her family with his own; but the narrative is not kind to him in return. One day the fated Helen murders him and all the children except Nessy/Vina, before committing suicide; this ‘because of’ the Vietnam war. Nessy moves, changes her name, becomes a woman; ‘and wherever she went, there was war. Men fought over her. In her own way, she was a Helen too’ (GBF 108,110). She is eventually retrieved by her father and packed off to India, where she arrives primed to play her part in the novel.8 Of course it is a subversive part. ‘She was a rag-bag of selves, torn fragments of people she might have become’ (GBF 122); and this wilful admixture, matched with Ormus’s visionary complex; wrought up by their joint dedication to the love of each other, and to music, provides the destructive energy that links their story with the central metaphor of seismic disturbance. ‘Later, entering that world of ruined selves, music’s world, they will already have learned that such damage is the normal condition of life, as is the closeness to the crumbling edge, as is the fissured ground. In that inferno, they will feel at home’ (GBF 148). The first song Ormus writes for Vina is ‘The Ground Beneath Her Feet’ (GBF 142), the song that haunts the novel. The full text only appears later still, on page 475, by which time Vina is dead and Ormus demented; when he admits to Rai that he is jealous of his dead twin, Gayomart, who communicated the song in the first place and now enjoys Vina in ‘her underworld, her other reality’ (GBF 476).9 One surmises that this is the one lyric quoted in the novel that Rushdie really believes in, the one that has been successfully grafted from the Orphic root; and it is no doubt appropriate that this has actually become a song, with the collaboration of the actual Bono from the real band U2. 133 SALMAN RUSHDIE Rushdie glosses the title of chapter 6, ‘Disorientations’, with mock etymology as ‘loss of the East’, and the narrative does begin to shut down its Indian operation here, as Rai’s parents’ ‘bitter quarrel’ erupts and their house (Villa Thracia) burns down (GBF 175,168) – one of several such conflagrations in the novel; Rushdie is fond of incendiary departures. Their premature deaths will follow shortly (GBF 204,6). Vina leaves, abruptly; deprived of her, Ormus becomes more and more dislocated, seeking her substitute frantically in other women (GBF 175–80). He will leave too, and Rai himself will follow: Vina was the first of us to do it. Ormus jumped second, and I, as usual, brought up the rear. And we can argue all night about why, did we jump or were we pushed, but you can’t deny we all did it. We three kings of disorient were. (GBF 177) But the disorientations are more general, and the narrative struggles to contain them; or is it the reader who is made to struggle? ‘It was the year of divisions, 1960’: Everything starts shifting, changing, getting partitioned, separated by frontiers, splitting, re-splitting, coming apart. Centrifugal forces begin to pull harder than their centripetal opposites. Gravity dies. People fly off into space. (GBF 163–4) The seismological metaphor looms larger, becomes more threatening; in preparation for the real Bombay earthquake of 1971 (GBF 217). Sir Darius goes on about cultural decline; ironically, before his own humiliation (for claiming fraudulent legal qualifications) on his last journey to England (GBF 150–4). And Rai’s representation of Ormus continues on its unrestrained trajectory. ‘What a figure he cut in public! He glittered, he shone . . . He spread his erotic gospel with a kind of innocence, a kind of messianic purity’ (181). But the private Ormus is taking another journey, a more profound disorientation from reality itself; he is coming nearer and nearer to ‘the dangerous edge of things’ (GBF 181,189). He no longer spoke much of Gayomart, but I knew his dead twin was in there, fleeing endlessly down some descending labyrinth of the mind, at the end of which not only music waited, but also danger, monsters, death. (GBF 182) 134 THE GROUND BENEATH HER FEET The historical narrative ‘out there’ also starts to do strange things. John F. Kennedy has a narrow escape from an assassination attempt in Dallas in November 1963; one Oswald is overpowered by ‘a middle-aged amateur cameraman called Zapruder, who saw the killer’s gun and hit him over the head with an 8mm cine camera’ (GBF 185). This is Rushdie having ‘fun’ in his parallel world; as we are reminded towards the end of the novel, ‘the spirals of postmodern irony twist tight and fast’ (GBF 525). But some historical facts remain immutable. The Indo-Pakistan war still takes place in 1965; though the reference to Mrs Gandhi’s triumph is another kind of irony, with ‘Geology as metaphor’ giving us both ‘Mrs Mover-and-Shaker’ and then ‘Dark Rumbles Shake Gandhi Administration’ (203). The allusion to the death of Nehru (in 1964), coincident with the murder of Darius Cama by his son Cyrus, underlines one consistent orientation in the novel: that towards death itself. We are never far from eschatology, Orphism, the four last things. ‘I am writing here about the end of something’ says Rai; and just before this, he proposes these conflicting formulae: ‘Death is more than love or is it. Art is more than love or is it. Love is more than death and art, or not. This is the subject. This is the subject. This is it’ (GBF 202–3). Whereas Midnight’s Children was a nativity novel, celebrating birth itself and the new reality created by the birth process, The Ground Beneath Her Feet is by contrast a novel half in love with death; even if the pull towards death is tempered (as it is in Keats) with the Orphic theme of the immortality conferred by art. Significantly, Rai is soon to tell us that Vina’s fourth abortion ‘had left her barren’ (GBF 226), like the dead women in Calf Island in Grimus; sometimes, the price paid by art is indeed a high one. Indeed, in human terms the price is everything. The three chapters (9, 10, and 11) in England are only a staging-post for Ormus on his way to America. The narrator Rai somehow disappears from these chapters, leaving the authorial voice to take over; and the author relishes the opportunity to indulge some vigorous satire, in the style of The Satanic Verses. The excesses of contemporary culture are a favourite theme of Rushdie’s (and of a Rushdie who remains, as his critics frustratedly observe, unchastened by the flagrant fact of his own investment in it); and the vagaries of sixties London afford him plenty of material. But the narrative advances on other 135 SALMAN RUSHDIE fronts. The American owner of a pirate radio station, Mull Standish (another name purposefully borrowed from Longfellow) is a key figure in the musical culture, who provides Ormus with his first big recording break; it is he who launches Ormus and Vina on their career, detonates ‘their almost totemic celebrity’ (GBF 303). He is also the father of two sons in a grotesquely dysfunctional family, hated by his ex-wife Antoinette Corinth (lest we miss the point) with a Greek intensity. ‘There will be a tragedy’ we are warned, and indeed there is: she tries to murder her two sons in a staged road accident, in which Ormus himself is nearly killed (GBF 298, 307). Ormus’s prolonged convalescence from his injuries gives time for several new narrative features: among them, the rivalry for Ormus between Vina and Maria, a woman who comes unsummoned from the ‘otherworld’ to minister to him; and the parallel which is developed between the ‘Ormus absconditus’ of these years and Rushdie’s own enforced public disappearance after February 1989. It is also during this time in London that Ormus’s identity starts to fragment, in a movement which parallels that we have observed all along in Vina. ‘There are too many people inside Ormus’ (GBF 299); there are also, it must be said, too many parallels with Gibreel Farishta from The Satanic Verses, as the paragraph which then follows makes only too obvious. Their removal to America in chapter 12 (to stay with the musical metaphor) takes the novel into a new key. But the key turns out to be visual, as the return of Rai to his narrative duties brings a return of the visual mode. The deepening divisions in Ormus’s psyche are now delivered in visual images. He actually starts to see different worlds in his two eyes, and describes this phenomenon to Vina as like seeing a movie screen with gashes in it; and perhaps there is another film showing behind, ‘and there are people in that movie looking the other way through the rips and maybe seeing us’ (GBF 347–8).10 Vina asks him if he hears voices; but no – it was of course Gibreel in the earlier novel who heard voices. Ormus is a victim of visual hallucinations, and (in what might do well in a comic strip version of the novel) decides to wear an eye-patch in defence against them. His different universes are ‘like parallel bars, or tv channels’; he can switch between them. ‘All that is solid melts into fucking air. What am I supposed to do?’ (GBF 349–51). What he does is write 136 THE GROUND BENEATH HER FEET a song about contradictions, ‘Everything you thought you knew: it’s not true’ (GBF 353), which doubles as caption to a two-page journalistic summary of recent historical events.11 Once arrived they submit to the hospitality of Yul Singh, at whose harbour house the weekend provides a comic interlude, including another couple who are ‘an admonitory pair of Vargas caricatures of themselves’. But by now it’s difficult to tell the caricature from the real thing. Or Vina from Maria, who has also made it across the Atlantic: ‘she has become part of his vision, of his seeing, he can control her appearances’ (GBF 359, 365). But at the end of this chapter, Ormus in desperation proposes marriage to Vina; she frivolously says yes – in ten years, and so for him ten years it is: ‘For ten years, until she is thirty-seven years old and he is forty-four, he will not touch or be touched by her body’ (GBF 370). The trouble is, this grand mythic gesture simply doesn’t fit with the relentless presentation of the contemporary. After all, Jane Fonda only made Ted Turner wait six months when he proposed to her straight after her split with Tom Hayden (and the reference is not unwarranted here, since Vina’s merchandising best-seller ‘diet book and her health and fitness regime’ (GBF 394) are later stolen from Jane Fonda herself). Reviewing The Ground Beneath Her Feet on its first appearance, a French critic remarked that America has not been kind to novelists not born there; somehow, they just don’t get it.12 This judgement is confirmed by the passage on ‘Sam’s Pleasure Island’, where Rai/Rushdie’s fascination with the excesses of New York’s hedonistic lifestyle can only be registered by a Swiftian, indeed Juvenalian disgust that is imported from another moral continent. Here are penis-ironers, testicle-boilers, shit-eaters, penis-boilers, testicle-eaters. Over there is the world Spermathon Queen, who encountered one hundred and one men, four at a time, in a non-stop seven-and-a-half hour megafuck. (GBF 377) Another feature of the novel’s emigration to America is that it puts a further strain on the narrative structure. True, Rai provides the ground of the visual metaphors; but he himself becomes a much more shadowy figure, in this world of ghosts and visions; indeed, he becomes a shadow of Ormus himself, a 137 SALMAN RUSHDIE kind of substitute, which is underlined by his own love affair with Vina. ‘I’m his true Other, his living shadow self. I have shared his girl’. (GBF 386) Especially when we think of the aspect of parabasis here – the author speaking through his characters – this sexual blending of the three has something vaguely incestuous, even onanistic about it (Rai is not associated with Narcissus for nothing). At this point the novel becomes homesick and needs a trip to India, which is prompted by the reappearance of Mull Standish and a contestation with Yul Singh for a deal with the rock stars. During this episode, India itself is described as ‘that country without a middle register, that continuum composed entirely of extremes’ (GBF 416), and one pauses once again to remark how apposite such a description is of the novel we are reading; which contains within itself, as it were, the seeds of its own identity, as well as the terms of a negative critique. The eventual marriage of Ormus and Vina, after their ten-year wait is described via a series of transparent references to John Lennon and Yoko Ono; and also, with a casualness that amounts almost to indifference, to the models that should ennoble them: ‘Like mythical lovers, Cupid and Psyche, Orpheus and Eurydice, Venus and Adonis. Or a modern pair.’ When Rai, their friend and narrator, and the custodian of their image in the novel, can add ‘So their wet dreams had got them through ten years’ (GBF 422), we sense not so much a geological as a stylistic fissure between the novel’s grand design and its verbal execution, page by page. Rai then remembers himself, and his PR role; ‘Love made them irresistible, unforgettable . . . When they walked into rooms, hand in hand and glowing, people fell silent, in awe‘; and yet, ‘Their music was their real lovemaking’. There is nothing more to say about them; they have vanished off the scale of the human. ‘In a way, they had ceased to be real’ (GBF 424–6). This attenuation of reality poses a more general problem for the novelist; as Rai disarmingly concedes, a little later: ‘Realism isn’t a set of rules, it’s an intention . . . The world isn’t realistic any more, what are we going to do about that?’ (GBF 449). This must be one of the weaker definitions of realism in the history of that abused term; disappearing straight into the intentional fallacy. And the fact that Rushdie is half-quoting a Norman Mailer quip here does not get him out of the difficulty. 138 THE GROUND BENEATH HER FEET Nor do the recurrent sections where Rai ‘catches up on’ history with a journalistic catalogue of events; more ‘current events collage’ (GBF 439). In Midnight’s Children, one remembers, we had the image of the ‘chutneyfication of history’ to suggest the way Rushdie creatively reprocessed real events for the purposes of his fiction; the dense imagining of the Sundarbans chapter, for example. But here in The Ground Beneath Her Feet we have only a thin journalistic wash, where events are sprinkled like condiments at table, and the novelist’s transformative power is suggested by such trivial examples as the conflation of Slaughterhouse Five and Catch-22 to give us Slaughterhouse 22; or by the fact that Elton John’s song ‘Candle in the Wind’ – already somewhat scandalously recycled by him for Princess Diana’s funeral – is then thoroughly pedestrianized as a song by Ormus, ‘There’s a Candle in my Window’: a song the memory of which is supposedly ‘pulling at your emotions’ (GBF 373,131). It is at this point that Rai makes the reckless assertion, ‘The god of the imagination is the imagination. The law of the imagination is whatever works . . . the work’s truth, fought for and won’ (GBF 446). Well, yes; no one would dispute this digest of romantic theory, with all the authority of Blake and Coleridge and Yeats behind it. But the assertion risks rebounding on Rai/ Rushdie here, since what may be fought for and won may also be fumbled and lost. One gets the distinct sense that the author knows, by this point in the novel, that he has (to use that vulgar metaphor from fiction) lost the plot, as he relies increasingly on extra-diegetic assertion rather than demonstration for his claims to quality and significance. Rai has another go, boxing foolishly above his weight: ‘Our creations can go the distance with Creation; more than that, our imagining – our image-making – is an indispensable part of making real’ (GBF 466).13 The narrative takes its course. We return to the devastation of the first chapter for Vina’s death, which is finely described in Rai’s studied cinematic slow-motion. ‘The earth closes over her body, bites, chews, swallows, and she’s gone.’ The quotation from King Lear which follows is curious, since one would have thought Vina, even in death, is at the furthest possible remove from Cordelia (whose ‘voice was ever soft,/Gentle and low, an excellent thing in woman’: V iii 274–5). The lines on Eurydice quoted from Virgil are more appropriate; and then Rai returns 139 SALMAN RUSHDIE to his recognizable idiom: ‘the human race offers the earth god its greatest prize, Vina!!’ (GBF 472; the double exclamation marks are his own). But whatever rhetorical excess Rai/Rushdie has practised on us so far, the chapter which follows on from Vina’s death scales the very heights of hyperbole. And the clue to this is that Rushdie, writing in the aftermath of the sudden death of Princess Diana in September 1997 (on which event he had written an excitable piece in the New Yorker),14 catches onto the tailwind of this, and fills his phrases with the hysteria. The two-page ‘statement’ in italic (GBF 478–9) could – does – refer as much to the dead princess, arrested in all her glamour, as to Rushdie’s own ‘rock goddess of the golden age’. ‘Dying when the world shook’, we are assured, ‘by her death she shook the world’. It is difficult to know how to take the author’s loss of judgement and control in the pages that follow. Not only are they extremely tasteless, as Rushdie piratically rewrites the grief for Diana as the grief for his fictional heroine – it is a kind of High Plagiarism – but the pitch of the prose is pushed into the realm of the actually absurd. The lords of information have been caught napping by the unexpected gigantism of the death and after-death of Vina Apsara, but within hours the greatest media operation of the century is under way . . . Meaning itself is the prize. Overnight, the meaning of Vina’s death has become the most important subject on earth. Vina significat humanitatem. (GBF 482) Light-headed from breathing this thin air, the reader at least knows he is on the last lap. But at this point, a curious thing happens; there is a rebalancing of the energies of the novel, a redirecting of its imaginative power. It is as if Rushdie wrests back control of the novel from his reckless narrator, Rai, who has all but run it aground with his coarse humour and his reductive instincts. And this happens with the introduction of Mira Celano, who ‘replaces’ Vina as lead singer in the relaunched VTO band. Because the wayward Rai now falls for Mira, and can concentrate on contriving his own happy ending; while Ormus is finally brought to accept the fact of Vina’s death, and prepares himself, through a purification in music, for his passage to the real other world. And we ourselves can now follow the ‘forking path’ to the two interweaved endings, which manage not to 140 THE GROUND BENEATH HER FEET interfere too much with each other – though Rai’s compulsive jealousy reminds us to the end of his baser metal. Let us dispatch Rai first. He and Mira (we note the pun) are made for each other; they inhabit the same discourse. And Mira herself knows clearly enough she is only playing a part with Ormus, through music: ‘I brought him back from Hell but that doesn’t mean I’ve got to burn in the fire instead’ (GBF 544). Rai and she become lovers; he meets her daughter Tara (from an earlier relationship which is lightly sketched in) and the happy family is all set up. There is a blip as the clay-footed Rai still manages to be jealous of Mira’s stage performances with Ormus, but even he fully realizes by the end the qualitative difference between them: So I admit also that Ormus’s love for Vina Apsara was greater than mine, for while I had mourned Vina as I had never mourned any loss I had, after all, begun to love again. But his was a love which no other love could replace, and after Vina’s three deaths he had finally entered his last celibacy, from which only the carnal embrace of death would set him free. Death was the only lover he would now accept, the only lover he would share with Vina, because that lover would reunite them forever, in the wormwood forest of the forever dead. For shutterbug Rai, that’s quite a poetic way of putting it; though he returns to his familiar idiom to describe his own situation here: ‘I was too stupid to believe it, but at the end of this long sad-luck saga, I was the jackpot boy’ (GBF 563). Meanwhile Ormus is able to attend to his own last things. The success of the relaunched band only serves to detach him more decisively from the world around him. There is a fleeting birth image for the band itself (’This is the sound of a baby being born. This is the rhythm of new life. We’ve got a band’ (GBF 546)), but this incongruous image does not indicate Ormus’s own direction. For him, ‘having lost all joy in life he began to look for death’. Rai has told us that ‘Ormus’s plan is to make the new show an exploration of the ourworld/otherworld duality with which he’s wrestled most of his life’ (GBF 557, 547), and here at last the power of the fiction, in Ormus’s invention of his other world, becomes real to us; because it balances with and is rooted in this one. 141 SALMAN RUSHDIE Having created his fiction he plunged into it and did not come out for two years. The fictional universe of the show gave the impression of floating free of the real world, of being a separate reality that made contact with the earth every so often, for a night or two at a time, so that people could visit it and shake their pretty things . . . He stood on his imagination, on what he had conjured out of nowhere, what did not, could not, would not exist without him. Now that it had been made, he existed only within it. Having created this territory, he trusted no other ground. (GBF 558–9) The scenario has been prepared for Ormus’s death, and here again one feels that Rushdie succeeds with his ‘remake’ of John Lennon’s death by shooting outside his New York apartment. The ‘tall dark-skinned woman with red hair gathered above her head like a fountain’ does seem to walk in from another world, not just the newspaper reports, and the fittingness of this conclusion – one ending – does seem to justify the means. ‘I think she came and got him because she knew how much he wanted to die.’ Not even Rai can reduce this image (GBF 569– 71). But even the genuine uplift of this ending, where Rushdie’s vision is allowed to come into its own, does not alter the fact that The Ground Beneath Her Feet remains a seriously flawed novel; flawed in its conception, with its meandering creative directions, its incoherences, and its inconsequential passages; and also in its execution, with its unfortunate admixture of studio talk and slangy street-speech (from three cities). And then the novel’s opportunistic top-dressing – using the hysteria surrounding Diana’s death as a launch pad – leaves a bad taste in the mouth. As for the detail of the execution, the actual writing, I have perhaps said enough already about the delivery of the text, chapter by chapter; but it may be useful to draw some of these dispersed observations together. The first problem is one to which I referred at the beginning of this chapter, and which has become increasingly apparent in my commentary on the narrative: namely, the consequences for the novel of Rushdie’s choice of narrator. It was finding the narrator, let us remember, that released the genie for Midnight’s Children. Rushdie entrusted no intermediary with the difficult task of narrating The Satanic Verses; the complex narrative strategies could only be carried out by an omniscient and untrammelled 142 THE GROUND BENEATH HER FEET third person. Moraes Zogoiby serves his own purpose in The Moor’s Last Sigh, adapting his register from lyric to satiric to elegiac as required. But here Rushdie has pitched upon a vulgar, coarse-grained photographer – fresh as he says from ‘pussyheaven’ (GBF 343) – to deliver his story about his larger-than-life lovers and artists, and the result cannot but be discordant. Either we have a discourse which comes straight from Hello! magazine and the latest celebrity hagiography, or we have Rai in more resentful mood descending to cheap jokes (the ageing Ormus is ‘more hip-replacement than hip’) or scabrous sexual references (as to Ormus and Vina’s ‘ten years of wet dreams’). In either case, the effect is horribly reductive, and sells the novel short. Not only does Rai steal Ormus’s woman, but he almost makes off with Rushdie’s novel. It is as if Iago were left to be the narrator of the novel Othello; there would not be much left of the Othello music either. The form of a play can accommodate such disjunctions, such a clashing of discourse and perspective (think of the Porter in Macbeth, or the Fool in King Lear; or of the contrast, more appositely, between the debased view of sexuality expressed by Thersites, and the exalted ideas of the lovers themselves, in Troilus and Cressida). But a novel hardly can, because so much is in the hands of the narrator. The result for The Ground Beneath Her Feet is a kind of creative equivocation, as if Rushdie can’t make up his mind which version of the story he is committed to: the full-blooded, lyrical, mythic and tragic version, with all the feeling, or the cut-down, cynical, comicstrip version, with all the jokes. No doubt a writer wants to have it both ways, and one can well believe this was Rushdie’s intention; but all one can say is that this double perspective doesn’t work – no more than does Ormus’s double vision, with the prop of his ridiculous eye-patch. Another aspect we can usefully consider here – as a further instance of the author’s symptomatic equivocation – is the way Rushdie actually allows some significant criticism of his project to find articulation within the novel itself. Sometimes this can be picked up from contemptuous references by Rai himself, to the music scene and its hangers-on. But the developed critique is supplied by the pair of composite cultural gurus Marco Sangria and Remy Auxerre, whom Rushdie keeps in the wings for this purpose. Composite is the right word: Sangria is described as 143 SALMAN RUSHDIE Italian-American, and Auxerre (a curious French-theoretical mixture of Barthes, Baudrillard and Foucault), as Francophone Martinican. To begin with, Sangria and Auxerre vie with each other to extol the significance of the singer/songwriter act; Rai concedes that ‘even by the gushing standards of music journalism . . . Marco and Remy are extreme’ (and we are given extreme examples to prove it: (GBF 392)). But later, both of them turn their acerbic analysis against the pair: To Auxerre and Sangria, they had become little more than signs of the times, lacking true autonomy, to be decoded according to one’s own inclination and need. Marco Sangria . . . announced that the VTO super-phenomenon was now too one-dimensionally overt, too vulgarly apparent. Their success was therefore a metaphor for the flatness, the one-dimensionality, of the culture. (GBF 426) But one is forced to reflect: isn’t Rushdie himself investing in this very culture? Isn’t the novel we are reading being fed, page by page, into the same ‘flatness’, the same bewildering undifferentiation? One might agree that it is astute on the author’s part to include this criticism, as if it might somehow ‘immunize’ the novel with negative antibodies against more trenchant criticism coming from outside; but response doesn’t work like that. We know what we know, and Rushdie has helped us (like it or not) to express it. To venture a bad pun on a level with some of his own: you cannot both have your ‘cold soup’ (GBF 504) and heat it. I am uncomfortably aware that I asserted in the first edition of this work – in the context of The Satanic Verses – that ‘the only worlds that are seriously called into question in Rushdie’s fiction are the flattened, value-free world of contemporary culture’ (see above, page 87). It is a troubling symptom of the sea-change in Rushdie’s writing, twelve years on, and the fundamental shift of perspective in his work, that this confident positive judgement no longer applies. The tsunami of contemporary culture has swept away such reference points as there once were. The presentation of the music itself is a different problem. As noted above, this is not a matter of the lyrics Ormus and Vina perform through the novel, many of which are printed in full in the text – including the lyric ‘The Ground Beneath Her Feet’, famously set to music and performed by Bono himself with U2. 144 THE GROUND BENEATH HER FEET But the novel does not include a CD; there is no ‘surround sound’; the music is left to Rushdie’s description and to our imagination. As Rai confesses at one point, ‘to me, set down on the page without their music, they seem kind of spavined, even hamstrung’ (GBF 354). This is surely a conclusive argument. And yet somehow it is assumed ‘[y]ou remember it’ (GBF 55); we are told that we remember songs that we have never heard, and that we are moved by the recollection. Now, it is true that Keats wrote in ‘The Grecian Urn’, ‘Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard/Are sweeter’; but this was in a poem that provides, in its verbal structure, an adequate equivalent both to the urn itself and to the music which is played, unheard, on its stringless instruments. The music which is played in The Ground Beneath Her Feet is certainly costlier and intentionally louder (Ormus has to be protected from the volume in a bubble) but the writing never manages to mix a fictional skein of sound. Even at the end when Ormus himself is transported and Mira is singing and Rai is consumed with jealousy (’Ormus was playing his guitar as if it were sex itself and Mira was pouring herself over him like a free drink . . . I had to fucking leave’ (GBF 562)), the cut-price phrasing leaves us quite indifferent. We are told, of Ormus and Vina, that their music creates meaning, that it articulates what it means to be human in our times (GBF 482). But if there is no music, nothing at the centre where this ‘meaning’ is supposed to be found, then we are left with something like Macbeth’s bleak reflections on life itself, once voided by absence: ‘It is a tale/Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,/Signifying nothing.’15 We remember E. M. Forster’s attempt to describe the effect of listening to Beethoven’s fifth symphony, in Howards End; ‘the music started with a goblin walking quietly over the universe, from end to end’, which impression is then interrupted by ‘elephants dancing’.16 Such attempts are always hazardous; we are not so far here from the unfortunate visual effects of Walt Disney’s Fantasia. It takes all the analytical, imaginative, and synthetic skills of a Thomas Mann to approach the experience of music, as he does in a late chapter of The Magic Mountain;17 to attempt, as he does there with infinite patience and delicacy and determination, successfully to describe the subtle links that exist between musical sound and human feeling; to understand why (as Shakespeare’s 145 SALMAN RUSHDIE Benedick puts it), ‘sheep’s guts should hale souls out of men’s bodies’.18 A similar argument may be developed on the visual plane, with respect to Rai’s photography. Whereas in the denser, more worked world of The Moor’s Last Sigh Rushdie was able to make much of Aurora’s paintings (as we have seen) by ekphrasis, weaving them into the narrative texture, creating depth and emotional colour and generating feeling, Rai’s photographs – even his supposedly ‘iconic’ photographs of Vina – are never effectively seen. Which is to say that the visual metaphors on which such a process would depend never take root in the novel; the frenetic movement of the all-action narrative never allows this to happen. It is all very well for a critic to argue, as does Carmen Concilio in her article on Rushdie’s narrator, that Rai ‘conjugates the complementary roles of narrator and photographer, of an oral art and a visual art’; but the visual can only be refracted by the verbal, in fiction, through an imaginative rather than chemical transformation; and this the novel fails to achieve. Concilio quotes (and seems to endorse) Rai’s claims that ‘a camera can see beyond the surface’, that photography can give access to ‘the metaphoric beyond the actual’ (GBF 80, 449), but this is just to repeat what is Rai’s protestation rather than Rushdie’s performance.19 We can conclude that both the metaphors of creativity in the novel – the novel as rock music, and the novel as photograph – founder on the inadequacy of the verbal medium to authorize or sustain them. For all the superlatives which are freely dispensed to its characters and their qualities, and for all the credit which we are expected to give them, this is a fatal weakness that leaves the novel a series of unrealized intentions. 146 10 Three Novels for the New Millennium Quite apart from the constraints of space dictated for a work in this series, there are several reasons for writing about Rushdie’s three most recent novels in a single chapter. First of all, these novels are inevitably linked by their historical moment: as millennial optimism is shattered by the attacks in New York of September 2001, and we have the subsequent – ongoing – ’war on terror’, with its attendant exacerbation of sectarian hostility and mistrust worldwide; as we see the loosening of some ties, and the establishment of others, with progressive globalization; the shifts of economic power and the realignment of other power bases on the planet, underlined by the credit crisis of autumn 2008; this in turn entailing the rise in food prices, which provides the context for the ‘Arab revolution’ (or the ‘Arab spring’) across north Africa in 2011. These forces are at work, implicitly and explicitly, in the novels we are to review here. And in the case of Rushdie, with the Indian subcontinent still looming large in his work, we have to add the terrorist attack on Mumbai in June 2008 by an Islamist group based in Pakistan, which caused serious destabilization between the two countries; and also the shooting dead of Osama bin Laden by American forces on Pakistani territory in May 2011. This latter event prompted a combative intervention by Rushdie in the online press, where he argued that unless Pakistan could provide an adequate explanation for the five-year presence of bin Laden and his entourage in a fortified residence near Islamabad, ‘then perhaps the time has come to declare it a terrorist state and expel it from the comity of nations’.1 147 SALMAN RUSHDIE But the feature which I think really identifies these later novels (and I include The Ground Beneath Her Feet retrospectively in this), is what I would describe as a thinning out of the verbal texture. It is as if Rushdie has developed a kind of shorthand, a technique of passing more rapidly and cursorily over events, dealing with ideas also in a more perfunctory manner (as if to say we have, and we know we have, been here before), and conceiving of characters in bold – or indistinct – outline, rather than in sympathetic or engaging depth. Of course it may be argued that this is deliberate; such a skimming shorthand is best suited to our superficial times, and there is no point looking for depth in a depthless world. But even as such a parallel is proposed, we know it to be specious. It is the hollow argument firmly castigated by Yvor Winters years ago, as ‘the fallacy of imitative form’. Sir Epicure Mammon is spectacularly superficial, but Ben Jonson cuts the verbal section deep to let him strut and fret his hour on the stage. Not many of Proust’s characters are noted for their profundity, but Proust still puts them through his slow and patient process of verbal creation. What we are talking about here is the danger of distraction; anecdotalized and mediatized distraction from what criticism used to invoke as ‘the actual quality of experience’. Once a novelist lets this quality slip through his fingers, the fictional fabric becomes attenuated, uninteresting. And this is immediately perceptible in the use of language. I would like to focus on one feature here: Rushdie’s (increasing) use of what I referred to earlier in this study as the ‘narrative superlative’. Of course this has always been a feature of his style, and magic realist style generally. (It also can be traced back to Dickens.) But may one not ask, in the end, does not the author protest too much? Cannot some woman, somewhere, be just beautiful (or ugly), rather than the most beautiful (or ugliest) woman in the world? Cannot some man be more or less in love, rather than torn up by the roots and devastated by passion? Another man moderately talented, averagely intelligent, occasionally brave, conventionally loyal? Isn’t there a law of diminishing returns with such rhetoric, as the gesture ‘claims’, verbally, what nothing in the narrative can possibly corroborate or sustain? What the reader neither believes in nor cares about? We end up with a devalued verbal currency 148 THREE NOVELS FOR THE NEW MILLENNIUM which is only able to deal in extremes, extreme qualities and their diametric opposites. Because Rushdie’s fiction habitually generates these extreme pairings as well, which revolve about each other like two stars in an alien universe. Creativity involves the manipulation of a rich and varied resource, not the permanent creaming off of the top layer. The obvious danger of doing everything on the high wire is that the referential function of language, which requires an immersion in the real world, becomes nullified, inverted, and turns instead – this is the natural revenge of an abused medium – into parody. The temptation to self-parody in Rushdie’s writing has often been noted; it has even been suggested that he breathes the air of self-parody quite comfortably at these exalted altitudes, and that once the convention has been recognized and accepted the reader has nothing to lose. But this is another specious argument. The writer-on-stilts (W. B. Yeats once declared, ‘Malachi Stiltjack am I’) loses the sensitivity and subtlety that can only be retained by contact with the common ground of discourse (Seamus Heaney’s earth-bound Antaeus, rather). It is a frustrating state of affairs for the long-time admirer of Rushdie’s writing that he seems so willing to underplay his own gift, and sell himself and the reader short. Valentine Cunningham remarks in a review on the ‘magnificent riffs’ in Fury, and he is right to do so.2 In all of Rushdie’s novels, whatever their vagaries and inconsistencies, there are magnificent passages (a paragraph, a page, several pages) which have the stamp of his imaginative and linguistic mastery. But then the pressure gauge falls again, and we find ourselves running on economy setting, with the worn-out gestures from the familiar toolbox of tricks. In the great, commanding novels, Midnight’s Children and The Satanic Verses, there is a scale and scope, a coherence of vision, which keeps the reader enthralled, surprised and entranced as the narrative does its work on him. We know, infallibly, that we are discovering something ‘rich and strange’, something new in the world, that we are sharing with the author in a profound and moving voyage of discovery. Whereas in the later novels – from The Ground Beneath Her Feet on – what we have only too often is more of a demonstration; not a voyage, but a tourist trip, with a guide who is evidently an expert in his field but seems curiously absent, disengaged. The tension and the expectation have 149 SALMAN RUSHDIE somehow evaporated; we know we have seen it all done better, by the same person, before. But let us take confidence from the fact that the admixture is still there; the real Rushdie can still be glimpsed, behind his stand-in simulacra; and it is in the hope of finding him that we will embark on these three later novels. FURY Fury, published just weeks before the fatal date of 11 September 2001, is the most personal and the most intimately detailed of Rushdie’s novels. The central character Malik Solanka is Rushdie’s age (at the time), and answers to his physical description; he was born in Bombay, educated at King’s College Cambridge and worked in the media before becoming a wildly successful . . . dollmaker. ‘Salman’ may even be recovered anagrammatically from his name (although it is unlikely that the complete anagram ‘lika Salman OK’ is intentional). There are tense relationships with ex-wives, and the pain of a severed relationship with a young son – the treatment of which, one has to say, drifts dangerously towards sentimentality. There is the recent move to New York, and the encounter with Neela Mahendra, ‘the most beautiful Indian woman – the most beautiful woman – he had ever seen’ (F. 61), who coincides with the dedicatee of the novel, and Rushdie’s future fourth wife, Padma Lakshmi. A Rushdie novel, like a beehive, always has a queen; and once she has displaced the prefiguring Mila Milo, Padma/Neela is the undisputed queen of Fury; even assuming the role of one of the Furies themselves, before she sacrifices herself (and the new relationship) to a misdirected political cause. There are even well-known features from Rushdie’s social life, such as his notorious argumentativeness; and a public attempt at vicarious expiation for this, in ‘The Collected Apologies of Malik Solanka’ (anybody who has ever been offended by the author could well start here). At one moment, Solanka is struck by the discourse of a loud-mouthed New York taxi-driver, and Rushdie writes: ‘Solanka recognized himself in the foolish young Ali Majnu’ (F. 67) and indeed, one can read the novel – as many unsympathetic critics have done – as a sustained exercise in self-exposure. 3 150 THREE NOVELS FOR THE NEW MILLENNIUM And yet. Though all this is true, it is also true that Rushdie looks beyond simple identification (which would soon be exhausted in the telling) and uses the exacerbated consciousness of his dollmaking double to make what develops into a devastating and in the end unpitying analysis of the complacent strategies of the self; one is not spared by the satire, or protected by the sentimentality here. It is not surprising that these passages occur not in ‘domestic’ New York (where the plot involving the sexually motivated murders of three young women is patent top-dressing, borrowed from Kubrick’s film Eyes Wide Shut – which is mentioned, along with many other films, in the text (F. 203))4 but in the free-floating, fantasy world of Lilliput-Blefuscu, where Rushdie has to rely on his own imagination to keep the story going. And the imagination, once left to its own devices, tends to cut through the outer integuments, leading us into the claustrophobic circle of the self, where our weaknesses are mercilessly exposed. We are beyond autobiography here, and those critics who have accused Rushdie of self-indulgence in this context have simply stopped short of an intelligent reading. (Sarah Brouillette by contrast suggests that ‘the novel’s more significant solipsism is its paranoia about the way mass media make cultural products available for highly politicized forms of appropriation or interpretation that betray the controlling intentions of their authors’, and this takes the argument in another direction.)5 The personal trap has been primed by Solanka’s own creative success. His second series of dolls – the pretentious ‘Puppet Kings’ – has become so big, so ubiquitous in the American media that the characters/cyborgs cross over into real life and intervene in the political struggle in Lilliput-Blefuscu. This, with its announced Swiftian pedigree, is a fictional island functioning as a kind of post-colonial composite in the South Seas, constructed with the (then) recent history of Fiji in mind. Neela Mahendra has gone there, to support a would-be revolutionary named Babu, and Solanka makes the journey in pursuit of her. But by the time he arrives, Babu has turned into a kind of toy despot to whom Neela is enslaved; and Solanka is shut in a cell where he befouls himself. The process of humiliation is only beginning, and the passage that follows is excavated from deep in the damned self. 151 SALMAN RUSHDIE It was hard not to fall into solipsism, hard not to see these degradations as a punishment for a clumsy, hurtful life. LilliputBlefuscu had reinvented itself in his image. Its streets were his biography, patrolled by figments of his imagination and altered versions of people he had known . . . The masks of his life circled him sternly, judging him. He closed his eyes and the masks were still there, whirling. He bowed his head before their verdict. He had wished to be a good man, to lead a good man’s life, but the truth was he hadn’t been able to hack it. As Eleanor had said, he had betrayed those whose only crime was to have loved him. When he had attempted to retreat from his darker self, the self of his dangerous fury, hoping to overcome his faults by a process of renunciation, of giving up, he had merely fallen into new, more grievous error. Seeking his redemption in creation, offering up an imagined world, he had seen its denizens move out into the world and grow monstrous; and the greatest monster of them all wore his own guilty face. (F. 245–6) This is to jump into the deep end of the novel; but I think it is useful to do so, since the depth that Rushdie offers us here takes the form of an intense critique of the creative faculty itself, which cannot fail to hold our attention. This I believe is the true ‘ground’ of the novel, its submerged subject, waiting (like the fabled Kraken) to be brought to the surface; and it is well to be reassured of the ultimate seriousness of the quest before retracing our steps to see just how the irritable dollmaker has been brought to this pass, to this moment of clear and uncompromising vision. We can then re-examine this vision, as it deserves, more thoroughly, which will take us into the very heart of Rushdie’s long-term fictional enterprise. The real quest in this novel, then, a quest in which Malik Solanka is driven by Furies he can no longer contain, is not for some cybernetic fictional utopia,6 and still less for the life in the United States for which Salman Rushdie himself has apparently settled. Both of these directions are abandoned in the novel itself. The quest is for the discovery of the self, or rather for the ‘unselfing of the self’ (F. 79), as Solanka seeks, through a painful process of confession and expiation, to recognize and admit to the kind of person he is, the forces that drive him, and the experiences which have made him so. It is the latest in the line of pilgrimages which Rushdie designs for his central characters, and which I have treated as such in this book. This time it 152 THREE NOVELS FOR THE NEW MILLENNIUM involves not only the physical pilgrimage, first to ‘real’ America and then to imagined Lilliput-Blefuscu, but also the difficult psychological journey into the processes of the creative imagination itself; a theme which has preoccupied Rushdie throughout his writing career, and which receives in Fury its most persistent and unsparing analysis. But we must first attend to Solanka’s social self, before exploring this other dimension. The revelation of this self requires first the resurfacing of memories (what Solanka calls ‘the back-story’), and this process is delineated very persuasively in the novel, as from his uncomfortable cockpit in New York (where he is persecuted outdoors by the city’s unrelenting noise and indoors by his Polish cleaning lady) Solanka introduces us first to his second wife Eleanor, their child Asmaan, and his doll ‘Little Brain’, whose mediatized success is the mainspring of the plot. He then goes further back to his Cambridge days, with more detail of his obsession with dolls, and early defining friendships; this in turn leading on to recollections of his first wife Sara Lear, with her abandoned thesis on Joyce and the nouveau roman and her rooted hatred of her husband’s dolls. Further anecdotes from his past surface at intervals, but it is not until Part Two (95) that we get more detail concerning the reasons for Solanka’s sudden flight from his wife and child in London, as told to a new woman friend Mila Milo. This has involved a battle between the doll and the child, and especially when we recall Rushdie’s frequent quotation from W. B. Yeats this opposition between artistic activity and the responsibilities of ordinary life irresistibly calls to mind his poem ‘The Dolls’7 – which might even have played some part in the gestation of the novel. (The fact that Mila Milo herself then takes on the qualities of a doll presents a further complication.) It is not until he has met Neela Mahendra that Solanka has the courage to recall his very earliest memories: the destruction of his childhood happiness by his parents’ separation, and the sexual molestation by his stepfather, a trauma which, we finally understand, fuels the fury that the adult visits compulsively on his world: and which, significantly, has dolls at its centre, ‘the dolls who crowded round him in bed, like guardian angels, like blood kin: the only family he could bring himself to trust’ (F. 223). But even before he tracks it to its source in his own 153 SALMAN RUSHDIE damaged life, Solanka realizes that this very turbulent complex of feelings is responsible for the best as well as the worst in our natures. This reflection occurs after a terminal argument with his first wife: Life is fury, he’d thought. Fury – sexual, Oedipal, political, magical, brutal – drives us to our finest heights and coarsest depths. Out of furia comes creation, inspiration, originality, passion, but also violence, pain, pure unafraid destruction . . . (F. 30–1) For Solanka, it is the creation of his dolls that best defines his personality, and it is this fact that has produced his wife’s outburst. ‘Your trouble is . . . that you’re really only in love with those fucking dolls. The world in inanimate miniature is just about all you can handle. The world you can make, unmake and manipulate, filled with women who don’t answer back’ (30). The creation of the dolls is a metaphor, in Fury, for creativity in whatever form; the voluntary intervention of the self and its motives in the larger processes that contain it, what is described elsewhere as the imposition of culture on nature, cybernetics on biology. And so the novel follows the career of ‘Little Brain’ on two planes; one external, charting the detail of the doll’s exponential media success, with the ineluctable commercialization of her character as product (Solanka has no control over this, and indeed laments it: now, ‘he hated Little Brain’ (F. 100), but still shamefacedly pockets the royalties); and the second internal, as the index of Solanka’s progressive moral isolation, and deepening guilt – the negative effects of his creativity – are borne in upon him. He is like Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner, except that instead of the albatross that the mariner has killed, he has the doll that he has given life tied round his neck; or like the fanatical Frankenstein, who comes to repent of the monster whom he has given life. What Solanka is brought to realize is that the same voluntariness that went into the creation of his dolls has leaked into the management of his human relationships, especially those with women; he has no defence against the charge of manipulation. His incapacity here may be understood as part of a generalized breakdown in trust between men and women: ‘Between the sexes the trouble was worst of all’; but this affords scant consolation. The fact that Mila Milo is instrumental too (’I renovate people’, she says (F. 115, 118)) only 154 THREE NOVELS FOR THE NEW MILLENNIUM sentences them to a mutually destructive encounter. Their relationship is symptomatic. When this lovely greeneyed girl introduces herself as a fan of Little Brain, Solanka is delighted; and he soon begins to ‘allow himself to see her as his creation’ (F. 124), she becomes for him simply another doll. But unbeknown to him, Mila has a lurid back-story involving an incestuous relationship with her widowed (writer) father, which has given her a sinister power and project of her own; and so she and Solanka fantasize each other, creating a guilt-ridden masturbatory complicity. Mila Milo is a vampire, a Lamia; she feeds off the same voracious fury as his own. It is significant that out of this complicity comes Solanka’s idea for ‘The Puppet Kings’, his ‘Empire of the Dolls’ that will put even Little Brain in the shade; and the fact that Mila becomes the producer of this show only underlines the perversity of the enterprise. By this time however Neela Mahendra is waiting in the wings (the Mila/Neela name-game is a typical Rushdie device), and she saves Solanka from being engulfed sexually by Mila. Rushdie’s lightly fictionalized ‘love letter’ to Padma/Neela extends over the next couple of chapters, and the author’s exhibition of his ‘trophy’ is rather embarrassing; but this is only a self-indulgent distraction from the fulfilment of Solanka’s sentence. Because even Neela cannot save him from himself, and his fatal investment in the Puppet Kings. She is caught up in the ensuing narrative from one side (through her personal involvement with Lilliput-Blefuscu), he from the other, through his manipulation of (and by) the fiction. Because it is a central proposition, by this stage, that Solanka has lost control of the fiction, as he has lost control of his own life; mazed in his imagination, and with no moral or ethical guidance, he has lost the capacity to distinguish between the two. And it is the complicated vortex of adventures in the Rijk civilization that lead Solanka to the solitary cell where we found him at the beginning of this chapter. And where we can resume our examination of the central theme of the novel, what Dr Johnson identified a couple of centuries ago as ‘that hunger of imagination which preys incessantly upon life.’8 As Solanka engages with his Puppet Kings, in what Mila Milo calls ‘serious play’, he finds that his ‘imagined world engaged him more and more’; 155 SALMAN RUSHDIE Fiction had him in its grip . . . He, who had been so dubious about the coming of the new electronic world, was swept off his feet by the possibilities offered by the new technology, with its formal preference for lateral leaps and its relative uninterest in linear progression, a bias that had already bred in its users a greater interest in variation than in chronology . . . Links were electronic now, not narrative. Everything existed at once. This was, Solanka realized, an exact mirror of the divine experience of time. (F. 186–7) The phrase ‘fiction had him in its grip’ recalls exactly the phrase from the minatory story ‘At the Auction of the Ruby Slippers’, which I have commented on in an earlier chapter (pages 103–4). ‘In fiction’s grip’, we were warned there, ‘we may mortgage our homes, sell our children, to have whatever it is we crave’, or alternatively, ‘in that miasmal ocean, we may simply float away from our desires’, withdrawing into contemplation of ourselves and the world. Solanka does neither of these things, exactly, but his investment in his fictions leads him by other routes to a profound insight into the paralysing ambivalence and equivocalness of the free-wheeling imagination. ‘[E]ntranced by the shadow-play possibilities’ of his doubled and reversible virtual world, he experiences ‘the dissolution of the frontiers between the categories’ of reality, that is to say all categories that would maintain a secure foothold in experience. And such an experience takes us inevitably on the route to the dissolution of the self, the self as discriminating moral being. The vertiginous appeal of ambivalence leads him to another unsettling question: ‘How far, in the pursuit of the right, could we go before we crossed a line, arrived at the antipodes of ourselves, and became wrong?’ (F. 187– 8). This is very close to Swift’s formulation from A Tale of a Tub, cited on the first page of this study, where Swift’s reckless author claims that the imagination is capable of leading us ‘into both extreams of High and Low, of Good and Evil’, an experiment of which the consequences cannot be foretold; and as we know, Rushdie has already conducted a full-blown version of the experiment in The Satanic Verses. Solanka himself pursues the experiment here in a shorthand form, via the opposition between his Puppet Kings and their rivals the Baburians, who have ‘a long dispute . . . on the nature of life itself – life as created by biological act, and life as brought into being by the imagination and skill of the living’ (F. 188). 156 THREE NOVELS FOR THE NEW MILLENNIUM An earlier rumination, on the condition of life in America, has led Solanka to recognize our human investment in mutability. ‘But our nature is our nature and uncertainty is at the heart of what we are . . . nothing is written in stone, everything crumbles . . . all that is solid melts into air’, a realization that comes in the form of a half-quotation from Prospero’s famous summary of being at the brink: Our revels now are ended; these our actors As I foretold you, were all spirits, and Are melted into air, into thin air . . . (The Tempest IV 1 148–50) It is this very ‘brinkmanship’ that makes us susceptible to fiction; just as our cellular structure is transforming us physically moment by moment, so we are always in movement, mentally, between our sense of ourselves as we are in the world and what we might become. And it only takes a certain pull or pressure, a release of energy, to put this process into overdrive. This is what Mila Milo provides; ‘Mila as Fury, the world-swallower, the self as pure transformative energy’. She it is who recruits Solanka, as she tells him, for the ‘fight to the death between the counterfeit and the real’, she who sets him loose in ‘the laws of your imagined universe’ (F. 177–8). And so by the end of the novel, we can say it is not so much the man as the ‘maker’ who has been on trial, and if he has mismanaged his life, it is precisely through what he has made – in it and of it, forgetting to distinguish between the dialectical, relational approach to truth and the imposition of one’s own truth on the order of the human. As we have seen, technology represents an hubristic temptation here at least as perilous for Dr Solanka as were Dr Faustus’s magic spells. From this point, having written the most intense and revealing scene in the novel, Rushdie can only provide an exit strategy, some kind of salvage operation. Rather as in the old suspense series (on the radio or in cinema shorts), Solanka escapes redoubtably from his self-made fictional trap; but of course Neela has to be sacrificed in the operation. (This is no James Bond film, after all; nor is one invited to think what Mila and Co must think of all this, back at the production desk.) All that remains for Solanka is to abandon his failed New York 157 SALMAN RUSHDIE experiment and go back to London and to his son Asmaan; with whom there is a richly sentimental ending set up on the bouncy castle. If not exactly a castle in the air, this is a castle outside of time, and well defended against Solanka’s own disturbing memories; here, for a moment, father and son are allowed to share the as-yet-uncontaminated eternity of childhood. SHALIMAR THE CLOWN Especially after the switchback ride of Fury, with its plunge through levels of reality and its teasing intersection with details of the author’s life, Shalimar the Clown returns to a more recognizable fictional formula for Rushdie, with a mixture of myth, magic, documentary record and historical concoction (including imaginary conversations with historical figures) served up with some postmodern panache in order to portray the ‘rape of Kashmir’ in the second half of the twentieth century. It is a downbeat novel for a terminal time; as a main character reflects in the last pages, ‘The century was ending, badly, of course . . . like the whole goddamn millennium’ (SC 395). The mood is fatalistic, weighed down by the future; tolerant and sunlit Kashmir – only fleetingly invoked here – is entering a time where ‘all certainty was lost, and the darkening began, ushering in the time of horrors’ (SC 82). Partition, parturition. It is not their fault that the two starcrossed lovers in the story, Shalimar and Boonyi, are born in the village of Pachigam on the same day in divisive 1947, not so much handcuffed to history as pilloried by it, and play out in their doomed and demented relationship all the violence and hatred of the times. They are not just star-crossed either, but stars-and-stripes crossed, as the person who later steals Boonyi from Shalimar is none other than the American ambassador, visiting Kashmir for the first time in the troubled 1960s (’America didn’t know what to do about India’ (SC 178)). And this provides another pull from outside which helps destroy the harmony of the high mountains (an image formed as such in Rushdie’s childhood, when the family took their holidays with the grandparents in Kashmir; the grandparents who are the dedicatees of the novel). This overlaying of ancient Kashmir 158 THREE NOVELS FOR THE NEW MILLENNIUM with modern America allows Rushdie to juxtapose a world of wooden huts and tents and the first TV in town with the world of luxury apartments, Bentleys and TV studios; and the further flashback to Max Ophuls’ past in war-torn Europe links the Nazi experiment and the concentration camps to the madrasa, the terrorist training camps across the Kashmiri border. The leaps of ten and twenty years in the narrative do create some problems of continuity, coherence (’And all of a sudden he was forty years old, battle hardened’ (SC 274) is how Rushdie transports Shalimar into the 1980s); and geographically, it is remarkable that a novel inspired by the towering Himalayas should begin and end claustrophobically in a Los Angeles bedroom; the first time with a dream of Kashmir, ‘like paradise . . . in a time before memory’ (SC 4), and second time with a living nightmare resurfaced from the fouling of that paradise. The sad fact (for the reader) is that Rushdie’s own imagination seems to get caught in the downward spiral he is narrating, and though his heart may be in Kashmir it is never invested in this narrative. The devil is in the detail, and the demons get into the ink here; the writing is frequently slack and formulaic, even perfunctory, as if the author just wants to get it over with. ‘Imagine it yourself’ we are told at one point; ‘What happened that day in Pachigam need not be set down here in full detail, because brutality is brutality and excess is excess and that’s all there is to it’ (SC 309). This is not normally part of a novelist’s contract with his reader; we expect to be accompanied with more patience and pertinacity, even on fiction’s darker pages; and the lists of atrocities (with dates supplied) that we get elsewhere do not fulfil the function any better. It is almost as if the author has contracted the anamnesia of his Indian colonel Hammirdev, who is afflicted by this mental disorder which allows a person to remember everything but without the capacity to understand or communicate it. Rushdie organizes this material with a classic modernist timescheme, beginning (almost) at the end with the murder of Max Ophuls by Shalimar and then going back to provide all the relevant (and less relevant) antecedent detail, in three long chapters, before returning in the last chapter to the dramatic culmination of the story. In order to provide a commentary here I will ‘flatten out’ this scheme, not oblivious of the fact that 159 SALMAN RUSHDIE Rushdie relies for many of his effects on the familiar proleptic gesture (Shalimar is referred to as ‘the assassin’ from his innocent youth, and Boonyi we are told would die before her time, etc). The unavoidable future is always looming oppressively over people who are simply trying to live their ordinary lives. Not only that, but several of the older Kashmiri women have the gift of second sight, foreseeing a future so bleak that they dare not even articulate it: ‘’’The age of prophecy is at an end,’’ Nazarébaddoor whispered, ‘‘because what’s coming is so terrible that no prophet will have the words to foretell it’’’ (SC 68). But nevertheless, this is the story that Rushdie has engaged to tell us. And so: in a paradisal Kashmiri village named Pachigam, washed by the waters of the Muskadoon, inhabited by families of circus people (one stop from Dickens) and genial cooks, Hindu and Muslim have lived in harmony for generations. Here, a young Muslim boy named Shalimar, son of the village headman Abdullah Noman, star of the circus for his tightrope walking (and who is of course ‘the most beautiful boy in the world’ (SC 54)) falls in love with the Hindu girl Boonyi Kaul, dancer and daughter of pandit Pyarelal Kaul; and she more than willingly accepts his advances. We don’t need to have read the epigraph to know that this is a Romeo and Juliet situation; however, the difference is that the tolerant community of Pachigam accepts and indeed promotes the match, which seems to confirm their neighbourliness. ‘We are all brothers and sisters here,’ said Abdullah. ‘There is no Hindu-Muslim issue. Two Kashmiri – two Pachigami – youngsters wish to marry, that’s all. A love match is acceptable to both families and so a marriage there will be; both Hindu and Muslim customs will be observed.’ Pyarelal added, when his turn came, ‘To defend their love is to defend what is best in ourselves.’ (SC 110) But we are not taken in; the epigraph Rushdie has chosen is actually Mercutio’s curse: A plague on both your houses. We know that the stakes here are too high. The girl Boonyi turns out to be trouble: more Cressida than Juliet, in fact. Even before her marriage she has caught the eye of the formidable Colonel Hammirdev Suryavans Kachhwaha of the Indian army, whom she has dangerously offended by telling him (in whatever words this would actually have been said) to ‘Fuck off’; whereupon he 160 THREE NOVELS FOR THE NEW MILLENNIUM resolves, ‘Pachigam would suffer for Boonyi Kaul’s insulting behaviour’ (SC 101). It is actually Boonyi’s friend Zoon Misri who suffers first, raped by the three Gegroo brothers, ‘a trio of disaffected, layabout young rodents’ (SC 126) who then take refuge in the mosque. Undermining the hopes of both Abdullah and Pyarelal, this rape is of course across the religious divide, and coincides with the 1965 war between India and Pakistan over Kashmir; which may last only 25 days but leaves behind ‘peace with more hatred, peace with greater embitterment, peace with deeper mutual contempt’ (SC 129). It is not long after this that Boonyi dances for the visiting American ambassador, Max Ophuls, setting up her own seduction and a scandalous public relationship with this fifty-year-old married man, which destroys the peace of Pachigam long before its physical destruction. And that peace, as so often in Rushdie, was maintained by stories. Abdullah Noman’s memory was a library of tales, fabulous and inexhaustible, and whenever he finished one the children would scream for more . . . Every family in Pachigam had its store of such narratives, and because all the stories of all the families were told to all the children it was as though everyone belonged to everyone else. That was the magic circle which had been broken forever when Boonyi ran away to Delhi to become the American ambassador’s whore. (SC 236) It is also the decisive moment that drives her deserted husband, Shalimar the clown, into what he welcomes as ‘the world of men’ (SC 251), turning him into a terrorist and assassin. But the treatment of Boonyi and Shalimar in the chapters that follow undermines the narrative, suggesting as it does a serious misjudgement on Rushdie’s part – a loss of control over the tone, and flow of sympathy – which risks alienating the reader. Let us take the case of Boonyi first. No sooner is she established as ‘the American ambassador’s whore’ (this we notice is the narrator’s word) in Delhi, than she begins to degenerate physically, and with startling speed. ‘She became addicted to chewing tobacco’, and a houseboy ‘led Boonyi deeper into the psychotropical jungle, teaching her about afim: opium . . . But her narcotic of choice turned out to be food . . . If her world would not expand, her body could. She took to gluttony with the same bottomless enthusiasm she had once had for sex . . . She ate seven times a 161 SALMAN RUSHDIE day’. It is curious, to say the least, that Rushdie seems to think the situation calls for comedy – and comedy which travesties his own serious themes: Her appetite had grown to subcontinental size. It crossed all frontiers of language and custom. She was vegetarian and nonvegetarian, fish- and meat-eating, Hindu, Christian and Muslim, a democratic, secularist omnivore. (SC 201–2) The pitiless dismantling of the dancing-girl continues: ‘Inevitably her beauty dimmed. Her hair lost its lustre, her skin coarsened, her teeth rotted, her body odour soured, and her bulk . . . increased steadily, week by week, day by day, almost hour by hour’ (SC 203). It is an extraordinary tableau, most resembling one of Swift’s late misogynist poems, such as ‘The Beautiful Young Nymph Going to Bed’. The portrait of Boonyi is positively vindictive, and one is left to wonder what is the source or purpose of this vindictiveness, which exceeds even the requirements of the heavily-symbolic plot. One can only conclude that there is an element of Rushdie’s own misogyny released here (like the deadly Bhopal gas cloud), the same the author was charged with after the publication of Shame; the novel which Shalimar most resembles, in this respect and others. Of course the ambassador soon abandons his bad bargain; but by this time the devious Boonyi is pregnant, and finds herself delivered of a daughter she names Kashmira in an orphanage for street girls. The baby girl is then taken from her by the embittered wife of the ambassador (who actually identifies herself as Rumpelstiltskin; the fairy-tale element is also present here, if in one of its more malignant manifestations). The abused Boonyi is returned to Pachigam, where she discovers she has been formally declared dead by her friends and family; it only remains for her to live out her frugal years in a hut above the village like her own ghost, waiting for her husband to fulfil his vow of revenge. When Ursula K. Guin writes that Rushdie is ‘never unkind to his female characters’,9 she must have forgotten poor Boonyi, laid down under her layers of fat, frozen in the snow, starved in her hut, slaughtered, and her corpse eventually made to stand for ‘the putrescent, flyblown reality of the world’ (SC 366). Thomas Hardy was kinder to his fallen woman Tess; but then he only had Victorian morality to contend 162 THREE NOVELS FOR THE NEW MILLENNIUM with, not the questionable and contorted gender politics of our own enlightened times. The novel is at one level less cruel to Shalimar himself, in that he is allowed more human dignity; but he turns out to be a clown nevertheless, in the disparaging sense of the term as well; he has no will, intelligence, or character, all his actions being rigidly determined by the plot – which requires as much: the iron mullah tells the terrorist recruits, ‘human nature was an illusion also, and human desires and human intelligence, human character and human will’ (SC 266); there is not much left for fiction to work on. We are assured that Shalimar had the ‘sweetest and gentlest nature of any person in Pachigam’, but this means strictly nothing, because immediately after he has made love with Boonyi for the first time the atmosphere of violence is ventriloquized upon him in this way: ‘Don’t leave me now, or I’ll never forgive you, and I’ll have my revenge, I’ll kill you and if you have any children by another man I’ll kill the children also’ (SC 61). Rushdie has confessed in interview that he always has problems with his plots,10 but this is surely a desperate manoeuvre. And his character puts up little resistance: ‘Shalimar the clown had stopped loving Boonyi the instant he learned of her infidelity, stopped dead like an unplugged automaton, and the immense crater left behind by the destruction of that love had at once been filled by a sea of bile-yellow hatred’ (SC 236). This novel is certainly better at hatred and violence than at peace and love, and Shalimar is in this sense a worthy recruit. As he is the perfect recruit in the training camp run by the iron mullah, Bulbul Fakh. ‘Before he was ready to embark on the great work in hand his consciousness had to be altered . . . Everything they thought they knew about the nature of reality, about how things worked and what things were, was wrong, the iron mullah said.’ ‘The new recruits listening to the iron mullah felt their old lives shrivel in the flame of his certainty’ (SC 265–6). Shalimar is carried off by this ideological avalanche, surrendering everything except his hatred, which he still keeps to himself; and it overlaps so conveniently with the mullah’s teachings. Boonyi, in her mountain hut, knows telepathically what is happening: ‘she knew only that the old Shalimar was dead. In his place, bearing his name, was this new creature, bathed in strangeness, and all that was left 163 SALMAN RUSHDIE of Shalimar the clown was a murderous desire’ (SC 273). The lovers are simply helpless indices of what is happening in the world at large; ‘An age of fury was dawning and only the enraged could shape it’ (SC 272). Revisiting the title and keyword from his previous novel, Rushdie certainly seems to qualify as one of the shapers. In the last chapter of the novel, when Shalimar is under sentence of death in St Quentin prison for the murder of Max (having already fulfilled his vow by killing Boonyi), an attorney lodges an appeal based on the argument that his client’s ‘free will was subverted by mind-control techniques’, that he was ‘a death zombie, programmed to kill’ (SC 383). If so, it was Rushdie’s iron plot that got to him, even before the iron mullah did. Whatever may be argued about the author’s attempt to link the personal and the political in this novel, no service is done on either plane by such flagrant (and explicit) manipulation. As we will see, even the elusive Max Ophuls is caught by the end in the same trap. It is presumably in order to probe the implications of American foreign policy in South Asia in the 1960s, as represented by this unlikely ambassador, that Rushdie tracks Ophuls back to his privileged childhood in the city of Strasbourg, ‘in a family of highly cultured Ashkenazi Jews’. This gives him the opportunity to sketch in the nineteen-thirties, when ‘history stopped being theoretical and musty and became personal and malodorous instead’ (SC 137–8), especially for Ophuls’ mild-mannered parents, who die in the camps as a result of Nazi medical experiments: ‘They never made it to the gas chamber. Scholarship killed them first’ (SC 157). The section which describes young Max’s adventures in the Resistance in France are almost extraneous to the novel, except insofar as they serve as his very flamboyant farewell to Europe – and allow Rushdie to enjoy himself, rather recklessly, and in a very different narrative style. Within twenty pages, Max becomes an expert forger of documents (’he felt he was also forging a new self’ (SC 148)), learns to fly, and becomes ‘one of the great romantic heroes of the Resistance: the Flying Jew’, after an improbable escapade with a rare Bugatti aeroplane – whereupon the ‘ungenerous reader’ is warned against confusing this story with that of Antoine de St Exupéry (SC 155, 160);11 seduces German spies to order (’perhaps the greatest contribution Max 164 THREE NOVELS FOR THE NEW MILLENNIUM Ophuls made to the Resistance was sexual’ (SC 163)); and finally makes a ‘run’ to Britain with fellow resister ‘Grey Rat’ Peggy Rhodes, who will become his disappointing but useful wife: ‘The run was successful: terrifying, with close shaves so bizarre as to feel almost fictional, but they made it’ (SC 169). This represents a close shave with novelistic decorum, as well. In London he incurs the dislike of General de Gaulle (a less difficult proposition one imagines than some of his other exploits), before deciding to move to New York, ‘where the Ophulses began their American married life’ (SC 174). And where the American political plot clicks into action. For the purposes of perspective, Rushdie frequently quotes from Max’s later ‘memoir’, and one such recollection refers back to his wartime forging of documents, ‘the creation of false identities. ‘‘The reinvention of the self, that classic American theme . . . began for me in the nightmare of old Europe’s conquest by evil. That the self can be remade is a dangerous, narcotic discovery’’’ (SC 162). And it is this same education which leads Ophuls first into an academic career, and then into the US diplomatic service; in which elevated capacity we meet up with him again in India. By this time he, and his America, have long surrendered resistance for complicity, and idealism for self-interest; and all of this we are meant to read into the squalid sequence which follows. But nevertheless, it suggests a remarkable realignment, a change not just of gear but of vehicle, for Rushdie to let Max be perceived by his daughter Kashmira, after his death, as ‘the occult servant of American geopolitical interest . . . the invisible robotic servant of his adopted country’s overweening amoral might’. The robot Max and the zombie Shalimar are well matched, as representatives of their respective political systems; and as Kashmira herself reflects here, perhaps justice had after all been ‘done to Max’ for ‘his unknown unlisted unseen crimes of power’ (SC 335–6). Whether justice has been done to Kashmir – or to the category of fiction about such things – is another matter. This reader finds the attempt to be bungled. If ‘America did not know what to do about India’, nor in this novel does Rushdie himself know what to do with his feelings about Kashmir. Serious negotiations are reduced to a farce of acronyms; atrocities are framed as statistics, or used as the basis for rhetorical riffs: the ‘Why was that?’ 165 SALMAN RUSHDIE sequence, and the ‘Who did this?’ sequence (SC 296, 308). When the Gegroo brothers are finally hunted down by her father, twenty years later, for their rape of Zoon Misri, their deaths are narrated as a cartoon animation; and when the iron mullah meets his fate, the description comes straight out of Dickens. ‘Inside the garments of Maulana Bulbul Fakh no human body was discovered. However, a substantial quantity of disassembled machine parts was found, pulverized beyond hope of repair’ (SC 298, 316). And for the last scene, the structurally determined one-to-one confrontation between Shalimar and Kashmira, Rushdie switches disconcertingly to a full-blown cinematic narrative style. The assassin prowling in the dark, the resolute quarry with her night-vision goggles, the tension that is wound up (with Kashmira’s archaic bow) and never quite released, are borrowed from a recognizable film genre that cannot pretend to provide a plausible or satisfying conclusion to a novel; least of all to one conceived with the pretensions to scale, and seriousness, of Shalimar the Clown. THE ENCHANTRESS OF FLORENCE Rushdie announced in an address to the University of Turin, in 1999, giving a clue to his ‘unwritten future’, that ‘I have for a long time been engaged and fascinated by the Florence of the High Renaissance in general, and by the character of Niccolò Machiavelli in particular’ (SAL 76). There is a further clue in a passage from the rock music novel published that same year, where the narrator Rai exhibits a surprisingly detailed knowledge of the musical entertainment of that period (GBF 54–8); and again in Fury, where the beleaguered Malik Solanka tries to sell to a sceptical studio his idea of a ‘claymation life of Niccolò Machiavelli’ and ‘the golden age of Florence’ (F. 101).12 So we should not perhaps be surprised that when The Enchantress of Florence appeared in 2008, it featured a bibliography of 85 items and 8 websites, which still represent (the author insists) ‘not a complete list of the works I have consulted’. So we can certainly not accuse Rushdie of skimping his homework. For good measure, the front endpapers of the book reproduce a detail from the building of the Fatehpur Sikri Palace, in the V&A, and 166 THREE NOVELS FOR THE NEW MILLENNIUM the back endpapers a beautiful panorama of Florence from the Carta della Catena, in the Museo di Firenze Com’era. And the novel is indeed a tale of two cities; the fleeting eastern city of Sikri, with its godlike emperor, exercising absolute power over life and death, and the western city of Florence, more solidly realized in its river, its streets, bridges and squares; and especially in the behaviour of its rulers and citizens in the early sixteenth century: ‘the drink-sodden daily life and sex-crazed nocturnal culture’, ‘the excessive hedonistic celebrations for which the city was renowned’ (EF 200, 273). Part of Rushdie’s project is to bring these two distant cities together, by means of travellers and travellers’ tales; love-lorn travellers and tales of sexual intrigue, so that they may end up as mirror images of each other – the mirror serving as a significant metaphor throughout the narrative. The action of the novel is conducted, therefore, at one remove (or at several removes), by the telling of tales, interruptive and interlocking tales which create a narrative structure of great complexity, which demands unusual attentiveness on the part of the reader. This is no ‘pageturner’; miss so much as a paragraph and you are likely to find yourself adrift in somebody else’s dream. In this floating world, the same character goes by several different names and is perceived in different terms by different people; dreams intersect with realities; alliances and oppositions form and reform, fuelled by the uncontrollable force of love and hatred. Though we are somewhere in the early sixteenth century, actual dates are few and far between, and recapitulative and proleptic gestures create a kind of narrative vertigo. So we must pick our way carefully over the stepping-stones provided. We can begin with the childhood friendship of three Florentine boys, Ago Vespucci (cousin of the famous Amerigo), Niccolò il Machia (the fictionalized Machiavelli) and the rootless Arcalia (whose name is taken, significantly, from Rushdie’s reading of Italian romantic-epic poetry). Like most boys of their time – of all times?–they are obsessed by sexuality, and one of their objectives is to locate the mandrake root which will, they hope, give them magical power over women. This episode is often recalled in their revisiting of the past; it functions as a reference point or refrain. Arcalia it is who breaks the triangle, and launches the narrative proper, by deciding at an early age to 167 SALMAN RUSHDIE go to sea and seek his fortune in the service of the Genoese admiral Andrea Doria. Rushdie’s research enables him to give a convincing account of maritime action in the Mediterranean of the time, in consequence of which Arcalia finds himself captured by the Turks. But this captivity allows him to shine in the service of the sultan (service which includes cutting off the head of Vlad the Impaler), and Arcalia is given a new name and a new identity as Argalia of the Enchanted Lance; in which role, and as lover of the mysterious Mughal princess Qara Köz, he makes a fair challenge to be the hero of the novel. Back in Florence, Ago and Il Machia hear nothing of Arcalia for twenty years, until a French woman, Angélique (nicknamed ‘The Memory Palace’) arrives at a brothel in a petrified condition, and under Il Machia’s caresses tells Argalia’s tale. The pages relating this episode are strangely moving; Rushdie has struck a rich vein here, as often when he explores the workings of memory. When she has discharged this function, her memory comes full circle; and assailed by the recollection of her own capture and rape, she commits suicide by leaping through a window. Il Machia regards Argalia’s service with the Turk as a betrayal, as becomes clear when the former friends meet later in Florence. All this the reader gleans from the overarching tale in the novel, which is the tale told by the traveller whom we meet in the first chapter (and who runs through several names before settling on Mogor dell’Amore) to the Mughal emperor Akbar. Mogor is under a dual compulsion: one the impulse within him, which obliges him (like the Ancient Mariner) to tell his tale, and the second from without, the instruction of the emperor, to whose presence he gained access in the first place by promising a wondrous tale; a tale which undertakes to prove by the end that the said Mogor, narrator, is no other than the emperor’s nephew. Needless to say, the emperor and his sceptical entourage are ready to exact the ultimate penalty if Mogor’s tale falls flat, or fails to convince. Not since Scheherazade has a narrator been so put upon – a parallel which is implicitly alluded to. The curious Akbar is sympathetic to Mogor’s project, remarking perceptively at one point that ‘he wants to step into the tale he is telling and begin a new life inside it’ (EF 203). The tale is therefore an exemplary metaphor of the universal process of 168 THREE NOVELS FOR THE NEW MILLENNIUM self-creation, delineated with unusual lucidity (’he was not only himself but a performance of himself’ (EF 6)).13 Finding oneself anonymous – or with a sheaf of names – in an alien culture, one simply has to self-invent; and Mogor dell’Amore, an emissary of love, carries the clue to himself in the love story of those whom he believes to be his parents. It is part of the (rewarding) intricacy of Rushdie’s narrative that as Mogor proceeds with his story at the Mughal court, Akbar’s mother and his aunt occasionally intervene to question or confirm or elaborate certain details, even revealing some things that have been kept – like the ‘hidden princess’ – from the emperor himself; and so the story is convincingly constructed, like tapestry, by several hands. Back in the narrated story, Argalia’s reward for another battle won (this time against the Shah of Persia, enemy of Akbar’s ancestor) is the sight of his captive, the princess Qara Köz; and the language of medieval romance is immediately allowed to take over. The princess Qara Köz turned to face him, making no attempt to shield the nakedness of her features from his gaze, and from that moment on they could only see each other and were lost to the rest of the world. (EF 223) Jane Austen we know parodied such stuff in her early novels (’no sooner did I first behold him, than I felt that on him the happiness or Misery of my future Life must depend’),14 but Rushdie has always been prepared to run with the romantic hare and hunt with the rational hounds, and so the discourses are allowed to jostle and accommodate each other – as they do not always, in the Aladdin’s cave of the author’s stylistic transformations. Somehow the theme of geographical juxtapositioning makes it work. The rest of the world however remains turbulent, refusing to leave the lovers to enjoy their idyll, and Argalia has to return to Italy, where he is more than happy to display his prize; as is Rushdie to write about the travelling circus of the beautiful Qara Köz and the dazzling companion who is known as her Mirror. (This is Aladdin in the narrative superlative; and any reader of Fury will recognize that the princess is Padma/Neela in another manifestation). Andrea Doria’s man Ceva is the first to clap eyes on Argalia and his women: 169 SALMAN RUSHDIE . . . standing beside him, appearing to draw all sunlight towards themselves so that the rest of the world seemed dark and cold, were the two most beautiful women Ceva had ever seen, their beauty unveiled for all to behold, their loose black locks blowing like the tresses of goddesses in the breeze. (EF 230) Gaglioffo the woodcutter is allowed to be more down-to-earth: ‘When you lay your eye on the pair of witches the desire to fuck them comes upon you like swine-fever’ (EF 239). The Mughal princess troubles Giuliano de Medici himself, as she appears in the magic mirror that displays to the reigning Duke of Florence ‘the image of the most desirable woman in the world’ (EF 267); and poor Ago Vespucci, hopelessly desirous of several women of the town, has suddenly to revise his standards, because the women coming down towards him were more beautiful than beauty itself, so beautiful that they redefined the term, and banished what men had previously thought beautiful into the ranks of dull ordinariness. A fragrance preceded them down the stairs and wrapped itself around his heart. He exclaims involuntarily, ‘I think I just discovered the meaning of human life’ (EF 260). The appearance of Qara Köz among the impressionable Florentines soon starts a cult; ‘the time of the ammaliatrice began’ (EF 268). People fall to their knees at the sight of her, miracles are claimed (EF 272, 278). Within moments of her coming she had been taken to the city’s heart as its special face, its new symbol of itself, the incarnation in human form of that unsurpassable loveliness which the city itself possessed. Argalia can even argue politically that she ‘comes here of her own free will, in the hope of forging a union between the great cultures of Europe and the East’ (EF 275–6). ‘It was the bright time of the enchantress.’ This is the novel’s apogee, in Qara Köz’s entitlement; and it is a relief that Rushdie sets aside his flashing superlatives for a moment to observe, ‘The truth was that Qara Köz was overdoing it’: one has to say, not unlike her author (EF 281). The mood then changes. We have already been told: ‘But the darkness would come soon enough’ (EF 278). The darkness comes in the form of Lorenzo de Medici, who lusts after Qara Köz and plots against Argalia in order to possess her; cynically observing to the cornered princess, when he does so, ‘You know how the world works’. When Lorenzo dies of syphilis 170 THREE NOVELS FOR THE NEW MILLENNIUM shortly afterwards she falls under suspicion, and the world turns against her (’What a short journey from enchantress to witch’ (EF 293, 297)), and with the death of Argalia himself, through the treachery of one of his followers, she only escapes from Florence – and into a fanciful future – thanks to the faithful offices of his friend Ago Vespucci. This sets up the last and longest chapter, where the egregious Mogor strains Akbar’s (and the reader’s) suspension of disbelief with the last loops of his story of the fugitive princess; though the emperor plunges even more irrevocably in love with her fleeing image. Where is Qara Köz to go, with the Mediterranean infested with pirates to the east? To the New World, suggests Andrea Doria, putting in a last appearance as a distinguished old man of the sea; where he also is moved to fall to his knees before her, seeing in her the figure of Christ in Gethsemane (EF 334). And so she ‘begins her journey westwards’ (a quotation from Joyce’s ‘The Dead’ that Rushdie does not employ); accompanied by the cousin of Amerigo himself, she and her Mirror go to America. Here (continues Mogor, unabashed), in this as-yet-uninvented continent, time is ‘completely out of control’ and other taboos are strangely suspended (EF 328), which is convenient enough for the events which are supposed to follow. A daughter is born – not to Qara Köz herself, but to her Mirror (‘We are yours’, she had after all said to her companion Ago). That daughter then conceives of her father a son; and that son – mistaking his mother – is the very Mogor dell’Amore who, travelling back some fifty years later from the new world to the old, has been telling us this story. Not surprisingly, Akbar does not quite believe it; palace plots hatch during his hesitation, and Mogor has to beat a hasty retreat – with his inevitable ladies – as the city of Sikri dries up and dies around them. But the last scene is managed by the ghost of Qara Köz herself, reigning unchallenged in Akbar’s imagination; ‘she had crossed the liquid years and returned to command his dreams . . . his godlike, omnipotent fancy’ (EF 349). In one sense, then, we can say that the declared project of the novel is a failure. East returns to the imaginative east where it originated, and west remains west with all its rational limitations. Worse still, just before Qara Köz’s final appearance, Akbar has a bleak vision of the future which allows Rushdie to visit our 171 SALMAN RUSHDIE own time, plunging mythic time back (or forwards) into history. The future would not be what he had hoped for, but a dry hostile antagonistic place where people would survive as best they could and hate their neighbours and smash their places of worship and kill one another once again in the renewed heat of the great quarrel he had sought to end for ever, the quarrel over God. (EF 347) Even Akbar’s erotic dreams are small compensation for this. But it is the art of storytelling that counts in fiction, not the delivery of some abstractable moral or symmetrical conclusion; and here one can surely say that Rushdie’s precarious narrative project has worked successfully. The complex narrative is anchored to the moment when we are introduced to the three Florentine boys: ‘In the beginning there were three friends’ (EF 134); the formula is repeated like a refrain through the novel, putting down the roots of reference and memory without which such a narrative could not cohere (it is significant that the last time we hear the refrain it is used by Akbar himself, caught up as he is in the trance of Mogor’s story (EF 339)). And so the web is wound out from Florence, and wound in in Sikri, with the magical strand that floats in also from the new world. The beginning in medias res, with Mogor trying out his tale on Hauksbank’s ship, the digressions, the seductive dreams and the fencing with the future are all part of the act, the dextrous performance that wins Rushdie his ‘silver medal’ (after Sterne’s gold), for ‘keeping all tight together in the reader’s fancy’.15 Rushdie makes no attempt to disguise the fact that this novel is a very literary exercise, emerging from his reading of Italian romantic epic as well as Florentine history; and it is intriguing, in this connection, that two of the main characters are as it were re-assumed into literature at the end. As Qara Köz sets out on her last journey to the new world, Andrea Doria thinks of her as ‘entering the book, moving out of the world of earth, air, and water and entering a universe of paper and ink’; and likewise when ‘Niccolò Vespucci the Mughal of love was gone for good’ from Sikri, his story having been concluded, he is located in that intriguing somewhere between the categories, having ‘crossed over into the empty page after the last page, beyond the illuminated borders of the existing world’ (EF 334, 343). It is even possible for us, by looking over Akbar’s shoulder, to 172 THREE NOVELS FOR THE NEW MILLENNIUM intercept one of those intriguing novelistic side-glances, where as the emperor confesses his shifting reactions to Mogor’s tale, we can glean some idea of the novelist’s view of his own performance: The emperor had experienced many feelings concerning this individual: amusement, interest, disappointment, disillusion, surprise, amazement, fascination, irritation, pleasure, perplexity, suspicion, affection, boredom, and increasingly, it was necessary to admit it, fondness and admiration. (EF 311) It is for each reader to decide how many of these reactions they experience in reading Rushdie’s novel; but it does at least provide us with a useful list of boxes to tick. The character of Rushdie’s disreputable narrator even affords us another insight, into the need to narrate; the very human impulse to tell stories. Akbar, we are told early on, has ‘dreamed up’ his non-existent queen Jodha ‘in the way that lonely children dream up imaginary friends’ (EF 27); the impulse explored by Beckett in his short but influential novel Company. And Akbar maintains this relationship until Qara Köz displaces her at the end – providing, incidentally, some of the novel’s most entertaining, light-fingered touches. But Mogor has to create a whole world around him wherever he goes and convince people of its existence. The most memorable image of this condition occurs shortly after his arrival in Sikri, when after falling unconscious as he embarks upon his dangerous story, Mogor is confined in one of Akbar’s dungeons. In the dark of the dungeon his chains weighed on him like his unfinished story . . . He would die without finishing his story . . . all men needed to hear their stories told . . . The dungeon did not understand the idea of a story. The dungeon was static, eternal, black, and a story needed motion and time and light . . . He felt his story slipping away from him. (EF 91) Not only does this recall analogous scenes in other novels by Rushdie – Solanka shut in the cell of himself in Fury, Moor Vasco Miranda’s captive in Spain, compelled to compose the narrative we are reading – but it also brings to mind the author’s own observation, in an interview, about how the traveller, the migrant, the pilgrim, must reinvent himself at every landfall, simply in order to survive: 173 SALMAN RUSHDIE I’ve always had the sense that people like me who arrive as strangers in other parts of the world more or less literally have to make up the ground we stand on . . . we have to imagine the world into being around ourselves because nothing can be taken for granted . . . So, voyaging, migration, whatever you want to call it, is a creative act. 16 The novelist, of course, counts on more than simple survival; the world he imagines is offered, like a gift, in exchange for what he receives. This is an idea to which I shall return in my Conclusion. 174 11 Conclusion In the Conclusion to the first edition of this book I invoked the idea of Salman Rushdie as a ‘pilgrim of the imagination’, contrasting the commitments of fiction to other kinds of commitment in the world. I reproduce one page of this argument here. But the engagement of fiction belongs to another order – to our imaginative conditioning rather than to our actual conditions, to what Shelley called ‘the primary laws of our nature’ rather than to the law of the land (or the laws of another land). And here Rushdie’s accomplishment is both more perplexing and more profound, and of more enduring value. In everything he has written, from Grimus to The Moor’s Last Sigh, Rushdie has explored on our behalf the hazards of being human, the limits of our human nature, as far as fiction can fathom it; and then beyond, into the intimations that lie beyond story itself in the very ground of our mental activity, among the archetypal prefigurings of being. As Ayesha led her pilgrims to Mecca, through the waters of the Arabian Sea (was it to death, or resurrection?), we should perhaps regard Salman Rushdie himself as a pilgrim of the imagination, and reach each of his novels as a stage in that pilgrimage. Flapping Eagle is a pilgrim through the levels of reality he encounters on Calf Island; Saleem Sinai leads the imaginative pilgrimage of the midnight children into modern India; Omar Khayyam Shakil is a peripheral pilgrim on the penitential journey of Pakistan. The Satanic Verses is an over-determined pilgrimage: from the vision of the founding of Islam to the literal pilgrimage of Ayesha, from the freefall metamorphosis ‘even unto death’ of Gibreel Farishta to the painful process of personal change that has to be endured by Saladin Chamcha before he can return to life, everything in this novel confirms that the transformation of life can be achieved only through travail. In the same spirit, Haroun takes his father on the healing voyage to the spring of storytelling. Rushdie’s short stories involve 175 SALMAN RUSHDIE several pilgrims, from Columbus as pilgrim-in-waiting in Spain to modern migrants making (or failing to make) their difficult way in different corners of the world. And Moraes Zogoiby, as we have seen, makes the reverse pilgrimage to that of Columbus, in search of his mother – from the real corruption of modern India to the fabled possibilities of medieval Spain. By forcing the evidence a bit, one can continue this argument to include Rushdie’s later novels, which have been the subject of the last two chapters. Ormus Cama does make a kind of pilgrimage to Europe and America, and even thinks of himself and the other passengers on his flight to England as ‘the Pilgrim Children’: ‘Welcome aboard the Mayflower, he greets them, seizing their hands as they pass his seat’ (GBF 250–1).1 But Ormus is more travelling Messiah than anyone’s disciple, with his image of America pre-packaged; and so this particular continuity breaks down; and one can hardly recognize the essentially opportunist narrator Rai as a pilgrim, either. I have already remarked how Malik Solanka, by contrast, can be seen as a very plausible pilgrim to the new world, and even thinks of his own saving adventure as such; though he is indeed a pilgrim travelling first class and with plenty of ill-will in his baggage. One draws a complete blank with Shalimar in this respect; Max Ophuls the ambassador is no kind of pilgrim (on the original Mayflower, he would surely have walked the plank) and Shalimar the assassin, with his mind closed to everything but murder, certainly doesn’t qualify. There is an obvious candidate for pilgrim in The Enchantress, that is to say Mogor dell’Amore himself, who has made the reverse journey (like Moraes Zogoiby) from the new world to the old, to convince that world about his parentage; so let us include him in the list. But what of the faculty of imagination itself, through which these ‘pilgrims’ were to discover the larger, more complex truths about themselves and the world? And here I need to take up the argument posed in the Introduction to this work, and encountered in differing terms – but always with a central role – in each of the novels. Because just as the imagination is the clue to our freedom and therefore to our humanity, for this very reason its function is equivocal, standing like a luminous but ambiguous signpost at the various forking paths of our lives. The imagination can be identified with our free will, our voluntariness, the energy 176 CONCLUSION with which we confront our experience: to whatever effect or consequence. And what explains the apparent moral neutrality of this function is that such effects and consequences are precisely not contained within our intentions; so the same motive or impulse can turn out positively in one case and negatively in another. We are creatures of circumstance, and our limited range of choices does not in itself determine our contribution, or even the nature of it, in human affairs. This bewildering, even demoralizing fact is part of the novelist’s art (and privilege) to interrogate; and we can see how, time and again, Rushdie places his characters in situations of precarious ambiguity. Gibreel Farishta experiences this ambiguity as a threat, and reacts punitively; in his developing paranoia he is even prepared to say, ‘if I was God I’d cut the imagination right out of people’ (SV 122). The imagination creates too much of a risk; just as we have also been told, ‘fictions are dangerous’. Moraes Zogoiby lives out the contradictions and reversals in his own life more patiently, in the case of his deception by both his parents and his lover Uma Sarasvati; his only too willing and cooperative imagination has not been able to protect him from fatal errors of judgement in each circumstance. Morally, he is left with some kind of uncertainty principle; and the fact that he ‘dies into his tale,’ telling it on his own tombstone (the ending is itself ambiguous and has been differently interpreted) reinscribes this uncertainty in the art of storytelling itself. But what seems to happen in Rushdie’s later work, in line with the general cultivation of the spectacular and the superficial, is that the imagination is treated as more of a toy than a moral quality; something than can be played with and then put away in its box, but which has lost its Shelleyan seriousness. We have seen how in The Ground Beneath Her Feet the principal characters have, like the demented Kurtz in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, ‘kicked . . . loose of the earth’2 (though Vina is eventually to be engulfed by it); their extravagant, unbridled imaginations have led them beyond the realm of the recognizably human; and Rai is no Marlow, to provide a gravitational pull the other way. Indeed, the reckless assertions of Rai/ Rushdie, such as that ‘the god of the imagination is the imagination’, show that the author is actually complicit in the elevation. Rai at one point even reflects, ‘if we could cut 177 SALMAN RUSHDIE ourselves loose, then so could everything else, so could events in space and time and description and fact, so could reality itself’: nothing more irresponsible in a writer than this, to suggest that reality is some kind of game, a take-it-or-leave-it, double-or-quits gamble. With which Ormus of course concurs; ‘If things get much worse the entire fabric of reality could collapse’ (GBF 343, 347).3 But not, surely, the stock market? It does seem to be the case that in Fury, Solanka/Rushdie is made to do penance (like the humbled poet in Tennyson’s ‘Palace of Art’) for his pretensions; but even so, as we have seen, a large part of the novel is devoted to illustrating and developing those pretensions, and so the evidence here is at best equivocal. Shalimar represents a different kind of imaginative failure, where the novelist under-reaches rather than over-reaches himself, allowing his fiction to become buried in unleavened historical detail. The insufferable Max Ophuls even delivers a stern lecture to his daughter India/Kashmira on the dangers of (film) fiction which seems to underpin this defeated aesthetic: ‘Be so good . . . as to cease to cast yourself in fictions. . . . understand, please, that you are nonfictional, and this is real life.’ Her obedient reaction to this is ‘a new-found reverence for the British documentarists John Grierson and Jill Craigie’, and a ‘determination to turn away from the dangers of the imagination and make a career in the world of the nonfictional’ (SC 352–3). One may read this as an oblique apology on Rushdie’s part for the failure of his own fictional mechanisms in the novel. But finally, in The Enchantress, we can say that the imagination is salvaged, if not entirely vindicated. The narrative here, as I have argued above, is beautifully constructed, and this allows Rushdie actually to achieve effects only gestured at in the preceding novels. Mogor is a truly captivating narrator, and the curious and tolerant Akbar his ideal auditor; this exchange gives us an illustration of what the novel should be able to offer us – when ‘the entire fabric of reality’ does not depend on the throw of a dice. And in this latest novel, whose historical setting makes it proof against the numbing noise, the jostling names, the journalistic inventories and the visual distractions of the twenty-first century, Rushdie seems to have rediscovered some of the innocence, and the delight, of storytelling. It is almost as if he has himself made the journey, with Haroun, to its healing springs. 178 CONCLUSION A BRIEF LOOK AT LUKA AND THE FIRE OF LIFE The mention of Haroun turns our attention, finally, to the companion novel that Rushdie published in 2010 for his second son Milan, Luka and the Fire of Life. And one would like to continue with the upbeat note of the last paragraph, to complete our survey; but for all the good intention that this novel for children and adults must have issued from, it sadly lacks both the fire and the life Haroun and the Sea of Stories. The two are set up in direct comparison by Rushdie himself, because the Luka of the new story is actually Haroun’s kid brother; we revisit here the household of the ‘Shah of Blah’ Rashid Khalifa and his longsuffering wife Soraya, as the fictive family faces up to a new problem. With Haroun we remember (and if not, we are reminded) that it was the Sea of Stories that was becoming corrupt and the battle was with the formidable Khattam-Shud for the survival of fiction itself; a bracing theme, which brought out all Rushdie’s inventiveness. But this time it is Luka’s father Rashid himself who is the problem; he has fallen asleep and can’t be woken, and the sinister figure of Nobodaddy sidles up as a kind of angel of death, waiting for his moment. Only if Luka can bring back the Fire of Life from the Magical World will the Shah of Blah be saved. There is inevitably a certain awkwardness here, as Rashid/ Rushdie becomes if not the active hero then at least the ‘sleeping hero’ of his story, and poor Luka has the unenviable role of PR for his father. The Magical World, he boasts, has been ‘made available to the general public by Rashid Khalifa in many celebrated tales’; it is, insists Luka to the Old Man of the River, ‘the one my father created’ (LFL 9, 54). Luka is sustained moment by moment on his quest by ‘his father’s voice’ (one cannot but think of the famous HMV icon), by ‘my father’s endless supply of bedtime stories’ (LFL 153–5). ‘Luka remembered his father’s words’ and again, ‘Luka remembered his big brother Haroun’ (LFL 161–2); so much so, that his own adventure reads like some kind of hand-me-down. At the crisis of the quest, when Luka has to defend the Magical World against the superannuated gods, he stands again four-square behind his father. 179 SALMAN RUSHDIE You see, I know something you don’t about this World of Magic . . . it isn’t your World! It doesn’t even belong to the Aalim, whoever they are, wherever they might be lurking right now. This is my father’s World. I’m sure there are other other Magic Worlds dreamed up by other people, Wonderlands and Narnias and Middle-Earths and whatnot . . . but this one, gods and goddesses, ogres and bats, monsters and slimy things, is the World of Rashid Khalifa, the well-known Ocean of Notions, the fabulous Shah of Blah. (LFL 180) Luka has earlier got one over the Old Man of the River with Oedipus’s answer to the Sphinx’s riddle (LFL 57), but one reflects that young Luka is soon going to have to confront Oedipus’s own more problematic dilemma, as he fights to extricate himself from Freud’s famous Family Romance. It’s curious that Luka should even claim the ‘gods and goddesses’ for Rashid Khalifa here, because in fact one of the things that weighs this story down is that rather than invent (as he did in Haroun, which was animated by original characters and contraptions of Heath Robinson singularity) Rushdie imports a whole pantheon of these superannuated deities, ‘Egyptian, Assyrian, Norse, Greek, Roman, Aztec, Inca and the rest’, to the point where Luka himself cries ‘Stop, please stop’ as he is assailed with yet another list (LFL 169, 205). It’s a wonder that Soraya’s magic carpet (surely, another threadbare device) can take off at all. Some of the goddesses while away their time here with the age-old competition, challenging the mirror on the wall as to who is the loveliest of them all, and there are the predictable sulks and scenes. I have to confess that when reading this I seemed to hear another overriding voice, participant in another competition, asking: ‘Mirror, mirror, on the wall,/Who is the novelist of them all?’ and found myself distinctly reluctant to come up with the expected answer. This sombre, solipsist, and second-hand tale does nothing new for Rushdie’s readers, of whatever age. But there is one last, intriguing idea that might inflect this view. In the very first chapter, Luka discovers his own magical power by putting a curse on Captain Aag’s tyrannical circus: ‘May your animals stop obeying your command and your rings of fire eat up your stupid tent.’ Miraculously, these words prove effective (‘Luka’s words were still out there in the air, doing their secret business’) and next day, when Grandmaster Flame 180 CONCLUSION (the same Captain Aag) cracks his whip and gives his orders, the animals rebel: when he saw all the animals beginning to walk calmly and slowly towards him, in step, as if they were an army, closing in on him from all directions until they formed an animal circle of rage, his nerve cracked and he fell to his knees, weeping and whimpering and begging for his life. (LFL 3–4) It impossible to read these pages in 2011 without thinking about the momentous events since spring this year in the Arab world; the ‘days of rage’ that have toppled tyrants in Tunisia and Egypt and Libya, and gone some way to achieve the same objective in Syria, the Yemen, and Bahrain. One cannot resist the thought that this is Rashid Khalifa up to his prophetic tricks again; in which case, though some of Luka is hard (or at least slow) going, we do after all have something to thank Rushdie and his MilanMuse for. LAST WORDS ON RUSHDIE CRITICISM It is inevitable with a writer of Rushdie’s visibility – and productivity: nine big novels, two children’s books and a collection of short stories, besides all the extraneous material – that the criticism of his work will be both very extensive, and also various, representing a multiplicity of views and purposes. I do not pretend to offer more than a bird’s eye view here, as some kind of commentary perhaps on the Select Bibliography, which is intended to serve as a guide for the reader into other directions. One can begin by suggesting that in general there are three layers or levels of criticism, which interact between them to create a prevailing view. First (in time) there are the reviews of novels in newspapers and journals, now readily accessible in most cases, and to most readers, via an online archive. These I compare to the second hand (of an analogue watch), busily ticking away and suggesting ideas that may or may not catch on and be developed in public opinion. As we know, and as is certainly the case with Rushdie, these reviews can veer between the overgenerous and the vindictive; but a sampling of several will tend to sort out the eccentric and help to keep the critical discourse on an even keel. Then we have the articles in learned journals. These are the 181 SALMAN RUSHDIE minute hand of criticism, marking a more gradual evolution in the consideration of a writer’s work; looking for parallels, influences, contexts; proposing new perspectives; sometimes (though this is less typical) attending to the intimate detail and the formal intricacy of this work or that. Here, often, we notice that personal response and ready valuation are as it were suspended, in the interests of objectivity or scholarly enquiry. The journal article is nothing if not serious. Finally we have the books; and I count about thirty books so far devoted exclusively to Rushdie’s work, with more than twice that number that contain chapters or significant sections on it. These are the hour hand of criticism, which tries to review and argue different positions in order to arrive at a measured judgement, taking everything as far as possible into account. These books will argue contrary things, but we should be able by consulting them to distinguish between what solid sense and evidence can supply and what derives from wit and whimsicality. The impression I have received from reviewing some of the criticism of Rushdie from each of these levels is that whereas the contexts and preconditions of his work have been very well and illuminatingly interrogated – the postmodern, the postcolonial, the migrant, hybrid, heteroglossic and the autobiographical Rushdies have been thoroughly investigated; his ideological positions attacked and defended; his life-style freely commented upon – the actual writing, the words on the page, seems very often to have escaped close analysis. It is as if once something has been written (and published), it is ‘written’ like a sacred or at least integral text, to be revered or refused but not analysed for its local detail and weighed in the critical balance. Felicities and flaws are alike irrelevant; they are not so much above or beneath critical notice but simply out of focus. The reason for this is that a displacement occurred early on; a displacement which means that the major critical debate over Rushdie almost always has to do with his ideological positioning. This debate was started by Timothy Brennan with his book Salman Rushdie and the Third World in 1989 and joined by Aijaz Ahmad in 1992 with his influential (but tendentious) In Theory. Most critics since that time have felt obliged to agree or take issue with Brennan and/or Ahmad, as a trawl through any book index will demonstrate. This debate then acts as a cage within which the 182 CONCLUSION novels themselves are confined, unable to engage with the real world on their own terms – as verbal fictions. They are estimated for how they play or do not play the ideological game (whichever is being proposed or vilified at the time). Whereas the ‘great game’ for the novelist as for the poet, is language, language unfettered by theoretical orientations, and only by the complex rules of this game will he succeed or fail; will his work take its place, or not, on the plane of the imagination; where different discourses blend and clash. The study of Rushdie by Andrew Teverson published in 2007 is not untypical in this respect and will serve as an illustration here. Teverson’s book is extremely thorough and informative on Rushdie’s various contexts, biographical, intellectual, linguistic – though we note that it is only the politics of language which he chooses to discuss, rather than its rhetorical features. But then his critical account of the novels remains curiously noncommittal, discovering other loops and circles to play around them rather than engaging with the verbal objects that they are. (Thus we have an eight-page long comparison with Walter Scott to help determine what kind of historical fiction is Midnight’s Children). He refers dismissively to one reviewer’s ‘gripes’ about Rushdie’s later style, but makes no attempt to explain or answer these gripes; which are actually quite justifiable, and raise serious questions about Rushdie’s ongoing fictional enterprise. When Teverson describes Shalimar the Clown as ‘a powerful novel’, it is the lack of any evidence to support this judgement that surprises us. He quotes two long paragraphs that ask a series of questions about atrocities in Kashmir, offering no suggestion as to how they interface with the fiction; ‘[s]uch question asking,’ he comments, ‘is characteristic of Rushdie’s fictional response to political events’ which he then goes on to consider in directly political terms, for its ‘constructive political functions’. 4 Likewise, one could question the critical function of the volume of essays previously cited, the proceedings of a conference at the University of Pisa devoted entirely to one of Rushdie’s novels. The title of the volume is itself arresting: The Great Work of Making Real: Salman Rushdie’s The Ground Beneath Her Feet.5 This is of course a quotation from one of Rai’s more provocative statements in the novel, where he claims to be doing just that; I have discussed the passage above, in chapter 9 (pages 183 SALMAN RUSHDIE 139, 146). But nowhere in the dozen essays that compose this volume is this central aesthetic issue directly addressed. The collection represents a formidable (indeed intimidating) display of scholarship, devoted to the literary allusions, the musical references, register, idiolect, etc, but all seemingly based on the premise that Rushdie’s claims for his novel are self-evidently justified: which is far from being the case. This is the true task of criticism to decide; and whatever their other merits, books of this kind do not help us in the act of discrimination. The kind of hands-on criticism I am thinking of is that singled out in the first chapter of this study (see above, pages 24–6); that practised by a critic like James Wood, in his excellent and exemplary How Fiction Works (2009).6 Fiction works by turning words; and unless you pay attention to how the words are turned, you are simply looking at maps of the country you wish to visit, not walking over the terrain. Or to change the metaphor, as Wood does in his epigraph, taken from Henry James: ‘There is only one recipe – to care a great deal for the cookery.’ Rushdie cared a great deal for the cookery in Midnight’s Children, and his ‘chutneyfication of history’ produced a work that earned and has deservedly kept the admiration and affection of its readers. This process was as much a matter of language – the choice of words, the structure of sentences; rhythm, balance; image and metaphor – as it was of vision and overall design; or of ‘constructive political function’. As much, that is to say, of text as context. Critics address themselves, no doubt, mainly to readers; but even by this indirect method, they can perhaps remind an author that it is by the best of his own work, the work that lives on and does its work in the imagination, that he will fairly and finally be judged. 184 Notes CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1. Shelley’s Prose, ed. David Lee Clark (London: Fourth Estate, 1988), 282– 3. 2. Jonathan Swift, A Tale of a Tub, sect. VIII; ed. A. C. Guthkelch and D. Nichol Smith (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1958), 157; Samuel Johnson, Rambler, no. 125 (28 May 1751); S. T. Coleridge, ‘Dejection: An Ode’, Selected Poetry and Prose, ed. Stephen Potter (London: Nonesuch Press, 1962), 107. 3. Laurence Sterne, Tristram Shandy, vol. II, ch. ii; ed. Ian Campbell Ross (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983), 170. Emile Zola’s relegation of the role of the imagination for the novelist is argued in his essay ‘Le sens du réel’, from Le Roman expérimental (Paris, 1880). A brief account will be found in my Realism (London: Methuen, 1970), 29–31. 4. See the account of Wilson Harris’s work in Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin, The Empire Writes Back: Theory and Practice in Post-Colonial Literatures (London: Routledge, 1989), 34–6, 149–54; and extracts in Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin (eds.), The Post-Colonial Studies Reader (London: Routledge, 1995), 188, 200–1. 5. Wallace Stevens, Opus Posthumous (London: Faber, 1954), 177. 6. J. R. R. Tolkien, Tree and Leaf (London: Unwin Hyman, 1964), 36–7. 7. Virginia Woolf, Collected Essays, ed. Leonard Woolf (London: Chatto, 1966), i. 320. 8. Steven Connor, The English Novel in History, 1950–1995 (London: Macmillan, 1996), 31. 9. Ashcroft et al. (eds.), The Post-Colonial Studies Reader, 209. 10. The phrase was coined (or adopted) in an editorial from The Crane Bag reprinted in Mark Hederman and Richard Kearney (eds.), The Crane Bag Book of Irish Studies (Dublin: Blackwater Press, 1982). See David Cairns and Shaun Richards, Writing Ireland (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1988), 149. 11. Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1991). Rushdie makes generous 185 NOTES acknowledgement in his essays to the importance of Anderson’s book to his own thinking; it contains, he says, ‘important stuff for the novelist’ (IH 382). 12. Shelley’s Prose, 279. 13. Lisa Appignanesi and Sara Maitland (eds.), The Rushdie File (London: ICA/ Fourth Estate, 1989), 181, 142. 14. For Rushdie: Essays by Arab and Muslim Writers in Defense of Free Speech (New York: George Braziller, 1994), 261. 15. Ziauddin Sardar and Meryl Wyn Davies, Distorted Imagination: Lessons from the Rushdie Affair (London: Grey Seal, 1990). Sardar writes: ‘[Rushdie’s] perspective as it unfolds through the entire course of his writing is best described as an angle of attack formed by the Orientalist view of Islam’ (p. 127). 16. Richard Webster, A Brief History of Blasphemy: Liberalism, Censorship, and ‘The Satanic Verses’ (Southwold: Orwell, 1990), 148. 17. D. J. Enright, ‘The Old Man Comes to his Senses’, Selected Poems (London: Chatto, 1968), 33. 18. Connor, The English Novel in History, 33. See also the assessment by Andrzej Gasiorek in Post-War British Fiction: Realism and After (London: Arnold, 1995), 167. 19. D. H. Lawrence, ‘The Novel’, in Bruce Steele (ed.), Study of Thomas Hardy and Other Essays (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 155. 20. S. T. Coleridge, Biographia Literaria, ch. 14; ed. George Watson (London Dent, 1965), 174. 21. See the articles on Midnight’s Children by Keith Wilson, Nancy E. Batty, and Patricia Merivale in M. D. Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie: Perspectives on the Fiction of Salman Rushdie (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1994), and also the further references in the section on the novel in the Annotated Bibliography (pp. 362–71). See also Walter Göbel and Damian Grant, ‘Salman Rushdie’s Silver Medal’, in David Pierce and Peter de Voogd (eds.), Laurence Sterne in Modernism and Postmodernism (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1996), 87–98. 22. Laurence Sterne, Tristram Shandy, vol. I, ch. xxii, ed. Ross, p. 58. 23. Una Chaudhuri, ‘Imaginative Maps: Excerpts from a Conversation with Salman Rushdie’, Turnstile, 2/1 (1990), 36–47. The text of this interview may be accessed at website http://www.crl.com/~subir/ rushdie/uc_maps.html. 24. ‘Salman Rushdie talks to Alastair Niven’, Wasafiri, 26 (1997), 55. 25. Timothy Brennan, Salman Rushdie and the Third World: Myths of the Nation (London: Macmillan, 1989), 30–1. Brennan’s book also takes up Benedict Anderson’s idea of the novel as being, along with the newspaper, a crucial ingredient in the formation of the ‘imagined community’. 186 NOTES 26. Ibid. 34, 69. 27. Ibid. 134. 28. Milan Kundera, Testaments Betrayed (London: Faber, 1995), 26. 29. Brennan, Salman Rushdie and the Third World, 135, 49. 30. Aijaz Ahmad, In Theory: Classes, Nations, Literatures (London: Verso, 1992), 128. 31. Ibid. 131, 134. 32. Ibid. 149–50, 135. 33. Oscar Wilde, ‘The Truth of Masks’, in Intentions and The Soul of Man (London: Methuen, 1969), 269. 34. Brennan, Salman Rushdie and the Third World, 43. 35. Ahmad, In Theory, 154–5, 134, 141. 36. Tim Parnell, ‘Salman Rushdie: From Colonial Politics to Postmodern Politics’, in Bart Moore-Gilbert (ed.), Writing India 1757–1900: The Literature of British India (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1996), 254–7. 37. James Harrison, Salman Rushdie (New York: Twayne, 1992), 128. 38. Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 66. 39. Malise Ruthven, A Satanic Affair: Salman Rushdie and the Wrath of Islam (London: Chatto, 1991), 13. (First published as A Satanic Affair: Salman Rushdie and the Rage of Islam (1990).) 40. Ibid. 15–18. 41. Michael Gorra, After Empire: Scott, Naipaul, Rushdie (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1997), 127. 42. Kundera, Testaments Betrayed, 26. 43. See the Appendix on ‘The Rushdie Affair’, pp. 88–93. 44. For Rushdie, 6, 10. 45. Sadik Al-Azm, ‘The Importance of Being Earnest about Salman Rushdie’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 258–77. 46. Srinivias Aravamudan, ‘Being God’s Postman is no Fun, Yaar’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 197–8. 47. Stephanie Newell, ‘The Other God: Salman Rushdie’s ‘‘New’’ Aesthetic’, Literature and History, 3rd ser., 1/2 (1992), 67–87. 48. Catherine Cundy, Salman Rushdie (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997), 22, 37, 52–3. 49. Ibid. 55. For Cundy’s consideration of this aspect in the later novels, see ibid. 78–9, 116. 50. Inderpal Grewal, ‘Salman Rushdie: Marginality, Women, and Shame’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 123–4, 143. 51. Anuradha Dingwaney Needham, ‘The Politics of Post-Colonial Identity in Salman Rushdie’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 149, 153, 157. 52. M. D. Fletcher, ‘Introduction’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 1–20. Likewise, Fletcher’s own essay, ‘Rushdie’s Shame as Apologue’ (pp. 97– 187 NOTES 108), proposes this unfamiliar formal category (supplemented with ridicule, satire, farce, and fairy tale), which is unlikely to inspire the reader. 53. Ib Johansen, ‘The Flight from the Enchanter: Reflections on Salman Rushdie’s Grimus’, in ibid. 25; Catherine Cundy, ‘ ‘‘Rehearsing Voices’’: Salman Rushdie’s Grimus’, in ibid. 48. 54. Peter Brigg, ‘Salman Rushdie’s Novels: The Disorder in Fantastic Order’, in ibid. 181. 55. These descriptions are taken from the section on The Satanic Verses in the Annotated Bibliography in ibid. 381–95. 56. Uma Parameswaran, ‘New Dimensions Courtesy of the Whirling Demons: Word-Play in Grimus’, in ibid. 42; Keith Wilson, ‘Midnight’s Children and Reader Responsibility’, in ibid. 62; Patricia Merivale, ‘Saleem Fathered by Oscar: Intertextual Strategies in Midnight’s Children and The Tin Drum’, in ibid. 84, 94. 57. See Aravamudan, ‘Being God’s Postman’; Kundera, Testaments Betrayed; and Feroza Jussawalla, ‘Rushdie’s Dastan-e-Dilruba: The Satanic Verses as Rushdie’s Love Letter to Islam’, Diacritics, 26 (1996), 50–73. 58. See Nancy E. Batty, ‘The Art of Suspense: Rushdie’s 1001 (Mid-)Nights,’ in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 69–82; Connor, The English Novel in History, 30–3, 112–27; Michael M. Fischer and Mehdi Abedi, ‘Bombay Talkies, the Word and the World: Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses’, Cultural Anthropology, 5/2 (1990), 107–59; N. Rombes Jr., ‘The Satanic Verses as Cinematic Narrative’, Literature/Film Quarterly, 11/1 (1993), 47–53. 59. Ashis Nandy, The Intimate Enemy: Loss and Recovery of Self under Colonialism (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1983), pp. xvii–xviii. 60. ‘Salman Rushdie Talks to Alastair Niven’, Wasafiri, 26 (1997), 53. 61. A selection from the essays in Imaginary Homelands: Rushdie praises Rudyard Kipling’s ‘invented Indiaspeak’, and the ‘demotic voice of black Afrikaner South Africa’ in Rian Malan (IH 77, 198); he notes Gunther Grass’s contribution to the reconstruction of the German language after the war, and the way Gabriel Marquez’s grandmother functioned as a ‘linguistic lodestone’ for him (IH 279, 300); he appreciates E. L. Doctorow’s ‘great rush of language’, and Thomas Pynchon’s ‘brilliant way with names’ (IH 300, 355). At the same time, he deplores the ‘rotten writing’ of Benazir Bhutto’s autobiography, and regrets the ‘dead language’ of Handsworth Songs (IH 57, 115). Even Kurt Vonnegut fails in this respect, with Hocus Pocus; in this novel, ‘that old hocus-pocus, language, just isn’t working’ (IH 360). 62. Salman Rushdie and Elizabeth West (eds.), The Vintage Book of Indian Writing 1947–1997 (London: Vintage, 1997), p. xviii. 63. Rustom Bharucha, ‘Rushdie’s Whale’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading 188 NOTES Rushdie, 162, 165, 169–70. 64 Jacqueline Bardolph, ‘Language is Courage’, in ibid. 212. 65. Harrison, Salman Rushdie, 127. See also the appreciation of Rushdie’s language in the Introduction by Anita Desai to the Everyman edition of Midnight’s Children (1995), pp. ix–x, xviii-xix. CHAPTER 2. GRIMUS 1. Rushdie himself recalls, ‘I had one novel rejected, [and] abandoned two others’ before Grimus (IH 1). According to Ian Hamilton, there was an early novel about Rugby called ‘Terminal Report’, and also (after Grimus) another Indian novel with more political edge, called ‘Madame Rama’, which was ‘plundered’ for Midnight’s Children (‘The First Life of Salman Rushdie’, New Yorker, 71/42 (25 Dec. 1995), 96, 100, 102). 2. Henry Fielding, Tom Jones, bk. II, ch. 1; ed. R. P. Mutter (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966), 88. 3. James Joyce, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1968), 253. One of the characters in The Moor’s Last Sigh elaborates a social philosophy based upon Joyce’s phrase, which he has supposedly picked up from the serial publication of the novel in The Egoist; and which he attempts to promulgate in a paper called Towards a Provisional Theory of the Transformational Fields of Conscience (MLS 20). 4. Timothy Brennan, Salman Rushdie and the Third World: Myths of the Nation (London: Macmillan, 1989), 70. 5. Liz Calder’s original assessment is worth recalling here: ‘although it was barmy in some ways, all over the place, I thought it was amazing,’ she says, particularly for its ‘extraordinary use of language’ (Hamilton, ‘The First Life of Salman Rushdie’, 101). 6. Lisa Appignanesi and Sara Maitland (eds.), The Rushdie File (London: ICA/Fourth Estate, 1989), 30. 7. Brennan, Salman Rushdie and the Third World, 72, 74; Catherine Cundy, Salman Rushdie (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997), 16. CHAPTER 3. MIDNIGHT’S CHILDREN 1. See John Haffenden, Novelists in Interview (London: Methuen, 1985), 237–8. 2. See Charu Verma, ‘Padma’s Tragedy: A Feminist Deconstruction of Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children’, in Sushila Singh (ed.), Feminism and Recent Fiction in English (New Delhi: Prestige, 1991), 154–62. 189 NOTES 3. Laurence Sterne, Tristram Shandy, vol. II, ch. xi; ed. Ian Campbell Ross (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983), 87. 4. Published in the original Spanish as Rayuela in 1963; translated as Hopscotch in 1966. 5. Timothy Brennan, Salman Rushdie and the Third World: Myths of the Nation (London: Macmillan, 1989), 85. 6. Andrzej Gasiorek, Post-War British Fiction: Realism and After (London: Arnold, 1995), 167. 7. Keith Wilson, ‘Midnight’s Children and Reader Responsibility’, in M. D. Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie: Perspectives on the Fiction of Salman Rushdie (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1994), 55–68. 8. The Tempest, I. ii. 49. 9. Sir Philip Sidney, An Apology for Poetry, ed. Geoffrey Shepherd (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1973), 123. 10. Wordsworth and Coleridge, Lyrical Ballads, ed. Derek Roper (London: Collins, 1968), 33. 11. See e.g. Philip Engblom, ‘A Multitude of Voices: Carnivalization and Dialogicality in the Novels of Salman Rushdie’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 293–304. 12. Published in 1904 and 1902 respectively. Both stories appear in Kipling’s Mrs Bathurst and Other Stories (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991). 13. See the interview with Steve Crawshaw in the Independent on Sunday, 8 Feb. 1998, pp. 29–31. 14. Brennan, Salman Rushdie and the Third World, 38, 69, 140, 159. 15. Steven Connor, The English Novel in History, 1950–1995 (London: Macmillan, 1996), 31–2. 16. See e.g. Patricia Merivale, ‘Saleem Fathered by Oscar: Intertextual Strategies in Midnight’s Children and The Tin Drum’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 83–96. 17. Daniel Defoe, Robinson Crusoe, ed. J. Donald Crowley (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972), 45. 18. See the article by Clement Hawes, ‘Leading History by the Nose: The Turn to the Eighteenth Century in Midnight’s Children’, Modern Fiction Studies, 39/1 (1993), 147–68. Hawes argues that the ‘logic of the babyswap is precisely against the grain of conventional ‘‘birth mysteries’’ ’, which, elsewhere, were used to authorize essentialist and ultimately racist attitudes. 19. Haffenden, Novelists in Interview, 239. 20. Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness, ed. Paul O’Prey (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983), 66; J. G. Ballard, The Drowned World (London: Berkley, 1962). There may also be a recollection here of Angela Carter’s story ‘Master’, from her 1974 collection Fireworks. 190 NOTES CHAPTER 4. SHAME 1. See Ian Hamilton, ‘The First Life of Salman Rushdie’, New Yorker, 71/42 (25 Dec. 1995), 105 (‘This Booker night of ‘‘Shame’’ has now passed into legend, by means of a Rushdiesque process of telling and retelling’). 2. Timothy Brennan, Salman Rushdie and the Third World: Myths of the Nation (London: Macmillan, 1989), 123; Aijaz Ahmad, In Theory: Classes, Nations, Literatures (London: Verso, 1992), 139; Catherine Cundy, Salman Rushdie (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997), 44. 3. Malise Ruthven, A Satanic Affair: Salman Rushdie and the Wrath of Islam (London: Chatto, 1991), 14; James Harrison, Salman Rushdie (New York: Twayne, 1992), 24; Keith Booker, ‘Beauty and the Beast: Dualism as Despotism in the fiction of Salman Rushdie’, in M. D. Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie: Perspectives in the fiction of Salman Rushdie (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1994), 249. 4. John Haffenden, Novelists in Interview (London: Methuen, 1985), 240– 3. 5. Ibid. 237. 6. See e.g. Ashutosh Banerjee, ‘A Critical Study of Shame’, and Suresh Chandra, ‘The Metaphor of Shame: Rushdie’s Fact-Fiction’. Both these articles, originally published in the Commonwealth Review, are reprinted in G. R. Taneja and R.K. Dhawan (eds.), The Novels of Salman Rushdie (New Delhi: Prestige, 1992). 7. Homi Bhabha, ‘Unpacking my Library . . . Again’, in Iain Chambers and Linda Curti (eds.), The Post-Colonial Question (London: Routledge, 1996), 208. 8. Jane Austen, Mansfield Park, ch. 15; ed. Kathryn Sutherland (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1996), 122. 9. Timothy Brennan, ‘Shame’s Holy Book’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 112. 10. Rushdie comments: ‘The book is partly about the way in which women are socially repressed . . . .Omar Khayyam’s mothers are another instance of female solidarity, which is really brought about by the way in which they are obliged to live in the male-dominated society’ (Haffenden, Novelists in Interview), 256. 11. Salman Rushdie, ‘Midnight’s Children and Shame’, Kunapipi 7/1 (1985), 13. 12. Jonathan Swift, Gulliver’s Travels, vol. IV, ch. viii; ed. Paul Turner (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971), 270. For the reference to A Tale of a Tub, see Ch. 7, n. 11 below. 13. Henry James, The Art of the Novel (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1934), 231. 191 NOTES 14. Timothy Brennan, ‘Shame’s Holy Book’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 119. 15. Haffenden, Novelists in Interview, 254–5. CHAPTER 5. THE SATANIC VERSES 1. See especially Malise Ruthven, A Satanic Affair: Salman Rushdie and the Wrath of Islam (London: Chatto, 1991), ch. 1, and Milan Kundera, ‘The Day Panurge No Longer Makes People Laugh’, in Testaments Betrayed (London: Faber, 1995), 1–33. Also the contributions by D. J. Enright, Homi Bhabha, Naguib Mahfouz, Carlos Fuentes, Michael Ignatieff, and others to Lisa Appignanesi and Sara Maitland (eds.), The Rushdie File (London: ICA/Fourth Estate, 1989); and the general tenor of contributions to For Rushdie: Essays by Arab and Muslim Writers in Defense of Free Speech (New York: George Braziller, 1994). 2. Appignanesi and Maitland (eds.), The Rushdie File, 6–7. 3. See Pierre François, ‘Salman Rushdie’s Philosophical Materialism in The Satanic Verses’, in M. D. Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie: Perspectives on the Fiction of Salman Rushdie (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1994), 305–20, at 305. Milan Kundera also has interesting observations on how the structure of the novel serves its meaning, in Testaments Betrayed, 21–3. 4. Hamlet, II. ii. 594–5. 5. Steven Connor, The English Novel in History, 1950–1995 (London: Macmillan, 1996), 124. 6. For a further consideration of this question, see Walter Göbel and Damian Grant, ‘Salman Rushdie’s Silver Medal’, in David Pierce and Peter de Voogd (eds.), Laurence Sterne in Modernism and Postmodernism (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1996), 87–98. 7. See Ruthven, A Satanic Affair, 24–5. 8. Walter Benjamin proposes that ‘memory is the epic faculty par excellence’ (Illuminations (London: Fontana, 1973), 96). 9. Connor, The English Novel in History, 113. 10. Srinivas Aravamudan, ‘Being God’s Postman is no Fun, Yaar’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 187–208. 11. Ibid. 199–203. Aravamudan notes: ‘The precise linguistic, indeed palindromic, opposite of muhammad ‘‘the glorified’’ or ‘‘the praised’’ in Arabic, is mudhammam, meaning ‘‘reprobate’’ or ‘‘apostate’’ ’ (p. 202). 12. Samuel Beckett, Company (London: Faber, 1980), 30. 13. Fawzia Afzal-Khan, Cultural Imperialism and the Indo-English Novel (Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press, 1993), 168–9. See also Feroza Jussawalla, ‘Rushdie’s Dastan-e-Dilruba: The Satanic Verses as Rushdie’s Love-Letter to Islam’, Diacritics, 26 (1996), 50–73. 192 NOTES 14. In an author’s note to a leaflet published by The Book Trust in conjunction with the British Council in 1987, Rushdie remarks: ‘First the writer invents the books; then, perhaps, the books invent the writer.’ 15. Steve McDonogh (ed.), The Rushdie Letters: Freedom to Speak, Freedom to Write (Dingle, Co. Derry: Brandon, 1993), 125–83. All facts and quotations in the next three paragraphs are taken from this source. 16. Rushdie’s own account of this episode may be found in the essay ‘One Thousand Days in a Balloon’ (IH 434–7). 17. James Joyce, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1960), 203. 18. Simon Lee, The Cost of Free Speech (London: Faber, 1990), 88. 19. The Rushdie Letters, 141. 20. Richard Webster, A Brief History of Blasphemy: Liberalism, Censorship, and ‘The Satanic Verses’ (Southwold: Orwell, 1990). 21. Lee, The Cost of Free Speech, 103. 22. See, for a detailed study of this aspect, Joel Kuortti, Place of the Sacred: The Rhetoric of the Satanic Verses Affair (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1997). 23. Ruthven, A Satanic Affair, 48. 24. Ibid. 47. 25. Lee, The Cost of Free Speech, 47. 26. In an interview published in 1996, Rushdie welcomed the fact that The Satanic Verses ‘is gradually getting off the news pages and getting back into the world of books’ (Colin McCabe et al., ‘Salman Rushdie Talks to the London Consortium about The Satanic Verses’, Critical Quarterly, 38/ 2 (1996), 66). This process should now be accelerated; and not only in books. The Satanic Verses clearly provided part of the inspiration for David Cronenberg’s 1999 film eXistenZ, both through the ‘reality loops’ that enrich and destabilize Rushdie’s plot and through the predicament of the author in the aftermath of publication. The film concerns an artist, a creator of games, who becomes embroiled in and victim of his/her own creation (it being part of the game that we are never sure who is the ultimate game-master: is God a man or a woman?). The game contends for reality. At various points in the film, where the narrative is cornered and rational argument breaks down, there is only a slogan (‘Death to the Demoness Allegra Geller . . . ‘Death to Realism’ . . . ‘Death to Yevgeni Nourish . . . for Deformation of Reality’), followed by an act of violence which projects us to another level. But the levels never resolve or stabilize, and we are left at the end of the film – after another dramatic reversal – with a rhetorical question: ’Are we still in the game?’ Intriguingly, it seems that Rushdie has returned Cronenberg’s compliment, drawing on the director’s ingenious treatment of games in this film for the rebellious gameworld in his later novel Fury; see chapter 10, below. 193 NOTES CHAPTER 6. HAROUN AND THE SEA OF STORIES AND EAST, WEST 1. James Fenton,‘ Keeping Up with Salman Rushdie’, New York Review of Books, 28 Mar. 1991, p. 31. 2. Several of the critical articles on Haroun draw parallels with Rushdie’s personal situation. See the relevant entries in the Annotated Bibliography in M. D. Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie: Perspectives on the Fiction of Salman Rushdie (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1994), 395–6. 3. In Jorge Luis Borges, Labyrinths (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970). 4. One critic suggests that Rushdie’s smuggling in of this female narrator is a gesture of solidarity with the woman novelist: see Marlene S. Barr ‘Haroun and Seeing Women’s Stories: Salman Rushdie and Marianne Wiggins’, in Barr (ed.), Lost in Space: Probing Feminist Science Fiction and Beyond (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1993). 5. Jonathan Swift, A Tale of a Tub, sect. VIII; ed. A. C. Guthkelch and D. Nichol Smith (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1958), 158. 6. There is probably a reference in both these instances to Lewis Carroll’s use of the chessboard to represent regulation in the Alice stories. 7. Rushdie has remarked that it was when he realized there was a story to be made of the stories, which taken together represent ‘a step by step journey’, that he decided to ‘put them together in a book’: ‘Salman Rushdie Talks to Alastair Niven’, Wasafiri, 26 (1997), 54. Catherine Cundy has actually suggested that the interlocking of the stories is intended to produce a parallel to the Mahabharata; but, although she cites what she sees as specific allusions (as where the unwinding of the ayah’s sari by the escalator in ‘The Courter’ parallels the disrobing of Drapaudi), the idea of a systematic counterpoint seems implausible (Salman Rushdie (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997), 3–4). 8. It is possible that Rushdie took the idea of a congregation of fictional characters from Christine Brooke-Rose’s novel Textermination (Manchester: Carcanet, 1991). In this intriguing work, hundreds of characters from fiction, film, and television attend a conference in San Francisco to ‘compete for being’ in the world of their readers and viewers. If so, it is only a compliment returned, since among the characters convoked by Brooke-Rose is Gibreel Farishta himself, from The Satanic Verses. 9. Walter Benjamin, ‘The Storyteller’, in Illuminations (London: Fontana, 1973), 93. 10. ‘Salman Rushdie talks to Alastair Niven’, 54. 194 NOTES CHAPTER 7. THE MOOR’S LAST SIGH 1. See e.g. the reviews by Peter Kemp (Sunday Times, 3 Sept. 1995), Michael Wood (London Review of Books, 7 Sept. 1995), Orhan Pamuk (TLS, 8 Sept. 1995), James Wood (Guardian, 8 Sept, 1995), J. M. Coetzee (New York Review of Books, 21 Mar. 1996). 2. Catherine Cundy, Salman Rushdie (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997), 116, 110. 3. J. M. Coetzee, New York Review of Books, 21 Mar. 1996, p. 14. 4. There may well be an allusion here to Adrian Mitchell’s lines on Charlie Parker: ‘He breathed in air, he breathed out light / Charlie Parker was my delight’ (‘Goodbye’, For Beauty Douglas (Alison & Busby, 1982). Especially when the next phrase reads: ‘– We breathe light – the trees pipe up.’ 5. Henry James, The Art of the Novel (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1934), 313. 6. Samuel Beckett, Molloy: Malone Dies: The Unnamable (London: John Calder, 1959), 7. 7. ‘Midnight’s Children had history as a scaffolding on which to hang the book; this one [The Satanic Verses] doesn’t’ (Rushdie in interview with Sean French, in Lisa Appignanesi and Sara Maitland (eds.), The Rushdie File (London: ICA/Fourth Estate, 1989), 8). 8. The personal feeling may be authorized by the fact that the novel with its palimpsest metaphor relates to a Rushdie family anecdote concerning an actual portrait of his mother, lost in all probability through being overpainted (see 13 below). 9. Orhan Pamuk remarks on the danger (just avoided here) of lapsing into an ‘old-style Indian melodrama’, and suggests that the ‘overabundance of fame, money, sex, and glamour gives the book an aura of a grotesque jet-set novel set in Bombay’ (TLS, 8 Sept. 1995, p. 3). 10. Shelley’s Prose, ed. David Lee Clark (London: Fourth Estate, 1988), 283. 11. ‘Last Week I saw a Woman flay’d, and you will hardly believe, how much it altered her Person for the worse’ (Jonathan Swift, A Tale of a Tub, sect. IX; ed. A. C. Guthkelch and D. Nichol Smith (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1958), 173; Beckett, Molloy: Malone Dies: The Unnamable, 268–9. 12. John Keats, letter to George and Thomas Keats, 21 Dec. 1817, in Letters of John Keats, ed. Frederick Page (London: Oxford University Press, 1954), 53. 13. This anecdote from Rushdie’s family was explored in the programme, ‘The Lost Portrait’ (transmitted by BBC 2 on 11 Sept. 1995), describing Rushdie’s visit to India in search of a portrait of his mother. Rushdie found the artist, but the canvas had been reused and the painting was therefore untraceable. 195 NOTES 14. J. M. Coetzee is, however, not impressed by this gesture, which he describes as part of a ‘postmodern textual romp’. As he sees it, there is a ready solution to the Moor’s problem: ‘If as self-narrator he wants to escape the inessential determinants of his life, he need only storytell his way out of them’ (New York Review of Books, 21 Mar. 1996, p. 15). 15. Walter Benjamin, ‘The Storyteller’, in Illuminations (London: Fontana, 1973), 94. CHAPTER 8. INTERCHAPTER 1. See the essay ‘A Dream of Glorious Return’ (SAL 195–227). 2. See the article ‘Manhattan Transfer’ by D. T. Max, reprinted from the New York Times in The Observer, 24 Sept. 2000. 3. It was Matt Thorne in The Independent who proposed Rushdie’s ‘relegation’; (‘Rich Man’s Blues’ 26 Aug. 2001); John Sutherland’s defence (‘Suddenly, Rushdie’s a Second Division Dud’) appeared in The Guardian, 3 Sept. 2001. 4. The Cambridge Companion to Salman Rushdie, ed. Abdulrazak Gurnah (Cambridge: Cambridge UP 2007), 169–83; 173–4. 5. The film was Bridget Jones’s Diary, directed by Sharon Maguire, (2001). For the idea of performance, see note 13 to chapter 10 below. 6. ‘Sir Salman’s long journey’, The Guardian, 18 June 2007. 7. See the interview in The Observer (12 June 2011). CHAPTER 9. THE GROUND BENEATH HER FEET 1. Interview with Sara Rance, in Chauhan (2001), 259. Several critics have reacted favourably to Rushdie’s attempt to write a ‘pop’ novel: see Teverson (2007) ch. 10, ‘The pop novel in the age of globalisation’. 2. The essay so titled appears in James Wood (2004), 167–83. Wood identifies Rushdie among others as writers (descended from Dickens, ‘an easy model’) who have developed hyperbolic excrescences of style to keep pace with the modern world; also, a ‘cinematic vulgarity’ deriving from the prestige of the seventh art. The phrase is used again in Wood’s highly critical essay on Fury, ‘Salman Rushdie’s Nobu Novel’ which appears in the same collection (210–22). 3. Rushdie once said (under whatever levels of irony), ‘If you offer me a movie to direct I’ll never write a book again’ (Chauhan 2001, 104). The irony is peeled off somewhat by his recent statement (see Interchapter) about the superiority of TV drama to both fiction and film. 4. A point made by Carmen Concilio in her article ‘‘‘Worthy of the World’’: The Narrator/Photographer in Salman Rushdie’s The Ground 196 NOTES Beneath Her Feet’, in The Great Work of Making Real: Salman Rushdie’s ‘The Ground Beneath Her Feet’, eds. Else Linguanti and Viktoria Tchernikova (Pisa: Edizioni Ets, 2003) 117–27; 118. 5. Interview with Charlie Rose, in Chauhan (2001), 257. 6. This formulation owes more to Shakespeare’s Berowne, in his celebrated valuation of women in Love’s Labour’s Lost: ‘From women’s eyes this doctrine I derive;/They are the books, the arts, the academes,/ That show, contain, and nourish all the world’ (IV. iii. 290–2). 7. Several critics have commented (approvingly and otherwise) on the device of the ‘parallel world’ that Rushdie sets up in this novel. Rushdie himself commented, in interview, on the ‘outrageous fictional proposition’ he was making with Ormus and Vina: ‘I said, ‘‘OK, well, what I’m obviously doing is making a slightly variant form of the real world.’’ And then I . . . just had fun with that idea.’ (Interview with Charlie Rose; Chauhan 2001, 260) 8. In the chapter ‘Salman Rushdie’s American Idyll,’ from his book Race, Immigration and American Identity (2008), 23–49, Randy Boyagoda accuses Rushdie of playing fast and loose with American history and culture in order to construct ‘something of a virtual America’ (34), which is effectively the immigrants’ version of the American Dream: get American ground beneath your feet, make your pile on it, and nobody will ask questions. Vina is his main target. ‘Vina is always Rai’s main index of American life’ (38). Vina is ‘redefined as a global Gatsby: she goes from being from nowhere and possessing nothing, to . . . being from everywhere and having everything’ (39). Her experience of the American south is ‘altogether unhinged from real history’ (43). Boyagoda then identifies ‘the inadequacy of Rushdie’s extraterritorial prose’ (a phrase he quotes from Nico Israel) ‘to engage even a modicum of the deep history of this particular American region’ (41). He goes on to demonstrate that Rai with his happy ending is ‘the beneficiary of these fruits . . . blind (like any good American) to his complicity in the nation’s predations’, the interest here being ‘his proximate relationship to Rushdie himself’ (47–8). Boyagoda concludes with the observation that ‘[w]hile Brennan, writing in 1989, balanced critique and esteem in his evaluation of Rushdie, the author’s more recent fiction demands a more exacting judgement’, a judgement unimpressed by ‘the immigrant-led merriments of money-making, mobility, and newness’ (48–9). 9. The idea of such communication may well have been suggested by the assertion of William Blake relative to his own dead brother, that ‘I hear his advice & even now write from his Dictate’ (letter to W. Haley, 6 May 1800; Blake: Complete Writings, ed. Geoffrey Keynes; OUP (1966). 797). 10. We remember that the image of the cinema screen as mediator of 197 NOTES reality/realities is used to good effect in both Midnight’s Children and The Satanic Verses. Not surprisingly, therefore, we have a sense here of déjà vu. 11. Timothy Brennan has referred to this feature in Rushdie’s recent work as ‘current events collage’, and the phrase is apposite enough (quoted by Stephen Morton, Fictions of Postcolonial Modernity (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2008), 149). 12. ‘On remarquera . . . que l ’Amérique n’est pas tendre pour les romanciers auxquels elle n’a pas donné le jour,’ ‘Salman Rushdie entre rock’n’roll et mythologie,’ Le Monde interactif, Feb. 2001. 13. This phrase is used in the title of the volume of essays cited in note 4 above (Pisa, 2003). The fact that Rai/Rushdie’s claim is not interrogated in the volume is typical of the uncritical stance taken by some dutiful scholarship towards Rushdie’s work. (I return to this argument in my conclusion.) 14. SAL, 118–21. The article begins; ‘It has all been so disturbingly novelistic’, referring of course to J. G. Ballard’s novel Crash, which had recently been filmed by David Cronenberg. Justyna Deszcz has a chapter on Rushdie’s use of Diana in her book Rushdie in Wonderland (2004), where she is surprisingly uncritical of the strategy. It is also curious that Anshuman Mondal, writing on the novel in The Cambridge Companion to Salman Rushdie (ed. Abdulrazak Gurnah, Cambridge, 2007; 169–83), while being very exercised by the ‘hyperbole that surrounds Vina’s death’ and the ‘rather bizarre manner in which celebrity has come to acquire an importance much greater than is warranted’ (176), makes no mention of the Diana parallel. 15. Macbeth, V. v. 25–7. 16. Howards End (1910, ch. 5; Vintage (New York, 1989), 34 ). 17. The Magic Mountain (1924), VII: ‘Fullness of Harmony’. 18. Much Ado About Nothing, II. iii. 58–9. 19. Further assertions as to ‘the superiority of the art of photography’, dubiously reinforced (’According to Roland Barthes, narration is always false and deceitful, while photography is always referential and truthful’ (126)) expose rather than evidence her argument. And the essay concludes with the weak observation that Rai faces up in the end to ‘the complexity of life’. CHAPTER 10. THREE NOVELS FOR THE NEW MILLENNIUM 1. ‘Pakistan’s Deadly Game’, The Daily Beast, 2 May 2011. Ruvani Ranasinha’s essay ‘The fatwa and its aftermath’ (in Gurnah, 2007; 45–59) provides a useful perspective on the development of Rushdie’s ideas since 1989. 198 NOTES 2. Literature Matters [emagazine published by the British Council], 32; 2001. 3. On the reception of Fury, see note 3 to the Interchapter, above. James Wood criticizes the novel from another aspect; what he sees as its relentless commodification and superficiality (’Salman Rushdie’s Nobu Novel’, in The Irresponsible Self; On Laughter and the Novel (London: Pimlico, 2005; 210–22). 4. References to the cinema are as usual important in the novel; to Kieslowski and Spielberg among others. Of particular importance is Tarkovsky’s SF film Solaris (1972), which provides Solanka with a model for his own thinking (and indeed Rushdie with a version of his plot); see the paragraph on page 220, concluding ‘ . . . we are left with the image of the mighty, seductive ocean of memory, imagination and dream, where nothing dies, where what you need is always waiting for you on a porch, or running towards you across a vivid lawn with childish cries and happy, open arms’. 5. ‘Authorship as Crisis: Salman Rushdie’s Fury’, Journal of Commonwealth Literature 40:1 (2005), 137–56. Brouillette’s article offers an intriguing study of the politics of authorship, and of the way larger contexts – including the media – dispossess an author of his text; or at least of its meaning. Thus understood, Fury represents an important commentary on the global sequel to The Satanic Verses. 6. As is suggested by Justyna Deszcz in her article ‘Solaris, America, Disneyworld and Cyberspace: Salman Rushdie’s Fairy-Tale Utopianism in Fury’, Reconstruction: A Culture Studies eJournal 2:3 (Summer 2002), 47 paragraphs; http://reconstruction.eserver.org/023/deszcz. htm 7. A doll in the doll-maker’s house Looks at the cradle and bawls: ’That is an insult to us.’ But the oldest of all the dolls, Who had seen, being kept for show, Generations of his sort, Outscreams the whole shelf: ‘Although There’s not a man can report Evil of this place, The man and the woman bring Hither, to our disgrace, A noisy and filthy thing.’ . . . The Collected Poems of W. B. Yeats (London: Methuen, 1961), 141–2. 8. Rasselas (1759; Oxford: OUP, 1988), 78. 9. Ursula le Guin, reviewing The Enchantress of Florence in The Guardian, 29 March 2008. 10. ‘I have always been described as a storytelling writer, but actually the 199 NOTES thing that’s hardest is the plot. I’m fine at bits and pieces, but a plot that actually works often comes last.’ (Interview with Sara Rance, (Chauhan 2001, 107)). 11. We are more likely to confuse him with the Wandering Jew, Ahuserius. 12. In addition, we may note the references to the emperor Akbar in the essay in SAL where Rushdie also confesses his enthusiasm for Akbar’s ancestor, the Mughal ruler Babur, and his famous book, the Baburana (SAL 188–94). Significantly, Rushdie compares Babur here to Machiavelli (193). 13. This aspect of ‘performing’ oneself – which we meet often in Rushdie’s characters – is illuminated by a comment made by the author in an interview with Sara Rance. ‘Performance – the idea of acting in society, especially to people who have had to change themselves dramatically from their original selves in order to live in the world – is very important in the book [The Satanic Verses], the way it is in Indian art.’ (Chauhan 2001, 106). 14. ‘Love and Friendship’ [sic], in The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Jane Austen, ed. Peter Sabor (Cambridge: CUP, 2006), 107. 15. See Note 6 to Chapter 5 (The Satanic Verses) above. 16. Interview with Terry Gross, 21 April 1999 (Chauhan 2001, 276). CHAPTER 11. CONCLUSION 1. Randy Boyogoda takes Rushdie to task for the trivializing effect of this allusion (Boyagoda 2008, 35). 2. Heart of Darkness (1902; Harmondsworth: Penguin (1983), 107). Conrad’s Kurtz is a model of destructive obsession, crazed egotism; and though his presence is much more palpable in the dense undergrowth of Conrad’s language, one finds oneself thinking of him as a progenitor of Rushdie’s rock stars. Marlow’s description of Kurtz continues here suggestively: ‘He was alone, and I before him did not know whether I stood on the ground or floated in the air.’ 3. Rai/Rushdie could well listen to the reprimand made by Soraya to her son Luka in LFL, when he starts to play around with ‘parallel realities’: ‘In the real world there are no levels, only difficulties . . . Life is tougher than video games’ (11–13). Perhaps it is time for the selfeffacing Mrs Khalifa to try her hand at fiction? 4. Teverson (2007), 128–35, 224–5. See in this respect the whole chapter (’Afterword’) on Shalimar, 217–26. 5. See Note 4 to Chapter 9 above. 6. London: Jonathan Cape, 2008; Vintage, 2009. Wood explains in his Introduction: ‘I have tried to give the most detailed accounts of the 200 NOTES technique of that artifice – of how fiction works – in order to reconnect that technique to the world, as Ruskin wanted to connect Tintoretto’s work to how we look at a leaf’ (2–3). It is true that Wood finds against Rushdie in the chapter on Fury in his earlier work The Irresponsible Self: On Laughter and the Novel, but I would counter-argue here that Wood’s address to the language in this novel is unduly (indeed irritably) selective. Which is also to say that responsible, verbal criticism can always lead us in different directions. But meanwhile the detail, the ‘facts’ that we are adducing from the text are real facts, even if not – as the critical use of them never can be – the ‘whole truth.’ 201 Select Bibliography WORKS BY SALMAN RUSHDIE Novels Grimus (London: Victor Gollancz, 1975; Grafton, 1977). Midnight’s Children (London: Jonathan Cape, 1981; Picador, 1983; Everyman’s Library, 1995, with an introduction by Anita Desai). Shame (London: Jonathan Cape, 1983; Picador, 1984). The Satanic Verses (London: Viking, 1988; Delaware: The Consortium, 1992). The Moor’s Last Sigh (London: Jonathan Cape, 1995). The Ground Beneath Her Feet (London: Jonathan Cape, 1999). Fury (London: Jonathan Cape, 2001). Shalimar the Clown (London: Jonathan Cape, 2005). The Enchantress of Florence (London: Jonathan Cape, 2008). Short Stories East, West (London: Jonathan Cape, 1994). ‘The Firebird’s Nest’, The New Yorker (23/30 June 1997, 122–7); reprinted in Telling Tales, ed. Nadine Gordimer (New York: Picador, 2004), 45– 64. Children’s Stories Haroun and the Sea of Stories (London: Granta Books/Penguin, 1990). Luka and the Fire of Life (London: Jonathan Cape, 2010). Poems ‘6 March 1989’, Granta, 28 (Aug. 1989), 28–9. ‘Crusoe’, Granta 31 (Sept. 1990), 128. Screenplay The Screenplay of Midnight’s Children (London: Vintage, 1999). 202 SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY Film and Television ‘The Painter and the Pest’, (Channel 4, 2 Dec. 1985; text in Imaginary Homelands, 152–6). ‘The Riddle of Midnight: India, August 1987 ’ (Channel 4, 27 Mar. 1988: text in Imaginary Homelands, 26–33). ‘The Lost Portrait’ (BBC 2, 11 Sept. 1995). Non-Fiction The Jaguar Smile: A Nicaraguan Journey (London: Viking, 1987; Picador, 1987). Imaginary Homelands: Essays and Criticism 1981–1991 (London: Granta Books, 1991). The Wizard of Oz: A Short Text about Magic (BFI Film Classics; London: BFI, 1992). Introduction to Rudyard Kipling, Soldiers Three and In Black and White (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1993), p. ix–xv. Introduction to Angela Carter, Burning Your Boats: Collected Short Stories (London: Vintage, 1996), pp. ix–xiv. Edited (with Elizabeth West), The Vintage Book of Indian Writing 1947–97 (London: Vintage, 1997); Introduction by Rushdie, pp. ix–xxii. Step Across This Line: Collected Non-Fiction 1992–2002 (London: Vintage, 2003). Edited (with Heidi Pitlor), The Best American Short Stories (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2008). SELECTED INTERVIEWS There are two collections of the more important interviews with Rushdie; the first, edited by Michael Reder, Conversations with Salman Rushdie (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2000); and the second, edited by Pradyumna S. Chauhan, Salman Rushdie Interviews: a Sourcebook of his Ideas (Westport: Greenwood, 2001). Interviews continue to appear, and many may be accessed online. For example, the Wikipedia entry on Salman Rushdie provides links to a dozen recent interviews. BIBLIOGRAPHY Kuortti, Joel, The Salman Rushdie Bibliography (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1997). See also the bibliographical appendix (353–9) and annotated bibliography (361–96) in M. D. Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie (Amsterdam: 203 SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY Rodopi, 1994). Among works listed below, those by Abdulrazak Gurnah (ed. 2007) and Stephen Morton (2008) contain very full, updated bibliographies. In the former, the bibliography is usefully subdivided into sections. BIOGRAPHY Hamilton, Ian, ‘The First Life of Salman Rushdie’, The New Yorker, 71/42 (25 Dec. 1995), 90–113. Repr. in Ian Hamilton, The Trouble with Money and Other Essays (London: Bloomsbury, 1998). This biographical essay draws on many personal and published sources, not least from Rushdie himself. Hamilton acknowledges Rushdie’s ‘generous help’ with the essay, which was given on one condition: ‘provided that I did not pursue my researches beyond what was for him the final day of his first life: Valentine’s Day, 1989.’ Weatherby, William J., Salman Rushdie: Sentenced to Death (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1990). The two collections of interviews listed above (ed. Reder 2000, and ed. Chauhan 2001) contain a good deal of (auto) biographical material. Among recent studies, that by Andrew Teverson (2007; details below) contains a substantial chapter on biographical contexts (67– 107). Again, online sources provide further material: not all of it always reliable. CRITICAL STUDIES Books on Rushdie Blake, Andrew, Salman Rushdie (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 2001). Bloom, Harold (ed.), Bloom’s Modern Critical Views: Salman Rushdie (Philadelphia: Chelsea House, 2002). Booker, Keith (ed.), Critical Essays on Salman Rushdie (New York: G. K. Hall, 1999). Brennan, Timothy, Salman Rushdie and the Third World: Myths of the Nation (London: Macmillan, 1989). A sustained critique of Rushdie’s ideological position, working through an analysis of the novels from Grimus to The Satanic Verses. Clark, Roger Y., Stranger Gods: Salman Rushdie’s Other Worlds (Montreal: McGill UP, 2001). Cundy, Catherine, Salman Rushdie (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997). A novel-by-novel account of Rushdie’s fiction, including a ‘Postscript’ on The Moor’s Last Sigh, with emphasis on contexts 204 SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY and intertexts; the feminist perspective finds unfavourably for the author. Deszcz, Justyna, Rushdie in Wonderland: Fairytaleness in Rushdie’s fiction (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2004). Fletcher, M. D. (ed.), Reading Rushdie: Perspectives on the Fiction of Salman Rushdie (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1994). A collection of twenty-two essays from different sources, focusing on each of the novels in turn. Contains a very useful annotated bibliography and ‘Some Books and Articles about the Rushdie Affair’. Freigang, Lisa, Formations of Identity in Salman Rushdie’s Fictions (Marburg: Tectum-Verlag, 2009). Goonetilleke, D. C. R. A., Salman Rushdie (London: Macmillan, 1998; 2nd ed., 2009). A loosely structured commentary on the novels, linking them to Rushdie’s biography. Gupta, Meenu, Salman Rushdie: Re-telling History through Fiction (New Delhi: Prestige, 2009). Gurnah, Abdulrazak, The Cambridge Companion to Salman Rushdie (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2007). The bibliography, pp. 187–96, is extremely thorough and discriminating on individual novels, themes, etc. Harrison, James, Salman Rushdie (New York: Twayne, 1992). Considers each of the novels (to The Satanic Verses) in the context of Rushdie’s complex background and influence; corrective to some postcolonial theory. Hassumani, Sabrina, Salman Rushdie: A Postmodern Reading of his Major Works (Madison: Fairley Dickinson UP, 2002). Kimmich, Matt, Offspring Fictions: Salman Rushdie’s Family Novels (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2008). Kortenaar, Neil, Self, Nation, Text in Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children (Montreal: McGill UP, 2004). Linguanti, Elsa and Tchernichova, Viktoria (eds.), The Great Work of Making Real: Salman Rushdie’s The Ground Beneath Her Feet (Pisa: Edizioni Ets, 2003). Mittapalli, R. and Kuortti, J. (eds.), Salman Rushdie: New Critical Insights (New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers, 2003). Morton, Stephen, Salman Rushdie: The Fictions of Postcolonial Modernity (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2008). Parameswaran, Uma, The Perforated Sheet: Essays on Salman Rushdie’s Art (New Delhi: Affiliated, 1988). A collection of seven previously published articles. Petersson, Margareta, Unending Metamorphoses: Myth, Satire, and Religion in Salman Rushdie’s Novels (Lund, Sweden: Lund University Press, 1996). A rich study of the influence of alchemical and other transformative ideas on Rushdie’s work. 205 SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY Rao, M. Madhusan, Salman Rushdie’s Fiction: A Study: The Satanic Verses Excluded (New Delhi: Sterling, 1992). A study of the relation between ‘timelessness’ and history in Rushdie’s first three novels. Reynolds, Margaret/Noakes, Jonathan, Salman Rushdie: The Essential Guide (London: Vintage, 2003). Sanga, Jaina C., Salman Rushdie’s Postcolonial Metaphors: Migration, Translation, Hybridity, Blasphemy, and Globalization (Westport: Greenwood, 2001). Seminck, Hans, A Novel Visible but Unseen: A Thematic Analysis of Salman Rushdie’s ‘The Satanic Verses’ (Gent: Studia Germanica Gandensia, 1993). Taneja, G. R., and Dhawan, R. K. (eds.), The Novels of Salman Rushdie (New Delhi: Prestige, 1992). A collection of twenty-four essays mainly by Indian writers, previously published in the Journal for Commonwealth Studies. Grouped around the novels, the essays, and ‘Themes and Techniques.’ Teverson, Andrew, Salman Rushdie (Manchester: MUP, 2007). See the Conclusion for a description of and critical response to this work. Thiara, Nicole, Salman Rushdie and Indian Historiography: Writing the Nation into Being (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2009). Books with chapters, sections, or essays on Rushdie Acheson, James (ed.), The British and Irish Novel since 1960 (Houndmills: Macmillan, 1991). Adam, Ian, and Tiffin, Helen (eds.), Past the Last Post: Theorizing PostColonialism and Postmodernism (New York: Harvester, 1991). Afzal-Khan, Fawzia, Cultural Imperialism and the Indo-English Novel: Genre and Ideology in the Novels of R. K. Narayan, Anita Desai, Kamala Markandaya, and Salman Rushdie (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993). Ahmad, Aijaz, In Theory: Classes, Nations, Literatures (London: Verso, 1992). Aldama, Frederick Luis, Postethnic Narrative Criticism (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003). Alexander, Maguerite, Flights from Realism: Themes and Strategies in Postmodernist British and American Fiction (London: Arnold, 1990). Ashcroft, Bill, Griffiths, Gareth, and Tiffin, Helen, The Empire Writes Back: Theory and Practice in Post-Colonial Literatures (London: Routledge, 1989). Ashcroft, Bill, Griffiths, Gareth, and Tiffin, Helen, (eds.), The PostColonial Studies Reader (London: Routledge, 1995). Ball, John Clement, Satire and the Postcolonial Novel: V. S. Naipaul, Chinua Achebe, Salman Rushdie (New York and London: Routledge, 2003). 206 SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY Banerjee, Mita, The Chutneyfication of History: Salman Rushdie, Michael Ondaatje, Bharati Mukherjee and the Postcolonial Debate (Heidelberg: Universitatsverlag C.Winter, 2002). Becker, Carol, The Subversive Imagination: Artists, Society, and Responsibility (New York: Routledge, 1994). Benson, Eugene, and Conolly, L. W. (eds.), Encyclopaedia of Post-Colonial Literatures in English (London: Routledge, 1994). Benson, Stephen (ed.), Contemporary Fiction and the Fairy Tale (Detroit: Wayne State UP, 2008). Bertens, Hans, The Idea of the Postmodern: A History (London: Routledge, 1995). Bevan, David, Literature and Exile (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1990). Bhabha, Homi (ed.), Nation and Narration (London: Routledge, 1990). _____ The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994). Boehmer, Elleke, Colonial and Postcolonial Literature: Migrant Metaphors (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995). Boyagoda, Randy, Race, Immigration and American Identity in Salman Rushdie, Ralph Ellison, and William Faulkner (London: Routledge, 2008). Bradbury, Malcolm, The Modern British Novel (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1993). Brooke-Rose, Christine, Stories, Theories, and Things (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991). Brouillette, Sarah, Postcolonial Writers in the Global Literary Marketplace (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2007). Burningham, Bruce, Tilting Cervantes: Baroque Reflections on Contemporary Culture (Nashville: Vanderbilt UP, 2008). Chambers, Iain, and Curti, Linda (eds.), The Post-Colonial Question (London: Routledge, 1996). Connor, Steven, The English Novel in History: 1950–95 (London: Macmillan, 1996). Cornwell, Neil, The Literary Fantastic: From Gothic to Postmodernism (New York: Harvester, 1990). Cronin, Richard, Imagining India (London: Macmillan, 1989). Dawson, Ashley, Mongrel Nation: Diasporic Culture and the Making of Postcolonial Britain (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2007). Dhawan, R. J. (ed.), Three Contemporary Novelists: Khrishwant Singh, Chaman Nahal, Salman Rushdie (New Delhi: Classical, 1985). Doherty, Thomas (ed.), Postmodernism: A Reader (New York: Harvester, 1993). Gasiorek, Andrzej, Post-War British Fiction: Realism and After (London: Arnold, 1995). Gauthier, Tim S., Narrative Desire and Historical Reparations: A. S. Byatt, Ian McEwan, Salman Rushdie (London: Routledge, 2006). 207 SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY Gorra, Michael, After Empire: Scott, Naipaul, Rushdie (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1997). Hanne, Michael, The Power of the Story: Fiction and Political Change (Providence: Beghahn, 1994). Jackson, Rosemary, Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion (London: Methuen, 1981). Israel, Nico, Outlandish: Writing Between Exile and Diaspora (Stanford: Stanford UP, 2000). King, Bruce, (ed.), The Commonwealth Novel since 1960 (Houndmills: Macmillan, 1991). Kirpal, Viney, The Third World Novel of Expatriation (New Delhi: Sterling, 1989). _____ The New Indian Novel in English (New Delhi: Allied, 1990). Kundera, Milan, Testaments Betrayed (London: Faber, 1995). Lane, Richard J., The Postcolonial Novel (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2006). Lee, Alison, Realism and Power: Postmodern British Fiction (London: Routledge, 1990). Leigh, David J., Apocalyptic Patterns in Twentieth-Century Fiction (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2008). Massie, Alan, The Novel Today (London: Longman, 1990). McHale, Brian, Postmodernist Fiction (London: Methuen, 1987). _____ Constructing Postmodernism (London: Routledge, 1992). Mehrotra, Arvin Krishna (ed.), A Concise History of Indian Literature in English (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2009). Moore-Gilbert, Bart (ed.), Writing India 1757–90: The Literature of British India (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1996). Onega, Susana (ed.), Telling Histories: Narrativizing History, Historicizing Literature (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1995). Price, David W., History Made, History Imagined: Contemporary Literature, Poiesis, and the Past (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999). Rai, Sudha, Homeless by Choice: Naipaul, Jhabvala, Rushdie, and India (Jaipur: Printwell, 1992). Richetti, John (ed.), The Columbia History of the British Novel (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994). Riemenschneider, Dieter (ed.), Critical Approaches to the New Literatures in English (Essen: Blaue Eule, 1989). Rubinson, Gregory, The Fiction of Rushdie, Barnes, Winterson, and Carter (Jefferson, NC: London: McFarland, 2005). Scanlan, Margaret, Traces of Another Time: History and Politics in Postwar British Fiction (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990). Shaffer, Brian W. (ed.), A Companion to the British and Irish Novel 1945– 2000 (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005). Sharma, Govind Narain (ed.), Literature and Commitment (Toronto: TSAR with the Canadian Association of Commonwealth Literature, 1988). 208 SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY Simpson, Peter (ed.), The Given Condition: Essays in Post-Colonial Literature (Christchurch, NZ: 1995). Singh, R. K. (ed.), Indian English Writing: 1981–5 (New Delhi, Bahri, 1987). Singh, Sushila (ed.), Feminism and Recent Fiction in English (New Delhi: Prestige, 1991). Smyth, Edward (ed.), Postmodernism and Contemporary Fiction (London: Batsford, 1991). Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty, Outside in the Teaching Machine (London: Routledge, 1993). Suleri, Sara, The Rhetoric of English India (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1992). Taylor, D. J., After the War: Novel and English Society since 1945 (London: Chatto & Windus, 1993). Tiffin, Chris, and Lawson, Alan (eds.), De-Scribing Empire: Postcolonialism and Textuality (London: Routledge, 1994). Upstone, Sara Joanne, Chaos and Spatial Politics in the Novels of Wilson Harris, Toni Morrison, and Salman Rushdie (London: University of London Press, 2004). Walsh, William, Indian Literature in English (London: Longman, 1990). Waugh, Patricia, Metafiction: The Theory and Practice of Self-Conscious Fiction (London: Methuen, 1984). _____ Practising Postmodernism (London: Edward Arnold, 1992). Wheale, Nigel (ed.), Postmodern Arts (London: Routledge, 1995). White, Hayden, The Content of the Form: Narrative Discourse and Historical Representation (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987). Williams, Patrick, and Chrisman, Laura, Colonial Discourse and Postcolonial Theory (Hemel Hempstead: Harvester, 1993). Wood, James, The Irresponsible Self: On Laughter and the Novel (London: Jonathan Cape, 2004). Young, Robert, Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture, and Race (London: Routledge, 1995). Zamora, Lois Parkinson, and Faris, Wendy B. (eds.), Magical Realism: Theory, History, Community (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995). Articles This selection lists only a small number of articles on Rushdie; mainly, those referred to in the present study. See Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie (pp. 361–96), for an Annotated Bibliography of some 200 Englishlanguage articles, divided into sections on the different novels. Joel Kuortti’s Salman Rushdie Bibliography lists over 2,000 articles of different kinds, more than half of which refer to the Rushdie Affair: see below. 209 SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY Articles on Rushdie appear in a wide variety of journals, those focusing on law, religion, politics, and race as well as those concerned with literature, history, and cultural studies. Al-Azm, Sadik, ‘The Importance of Being Earnest about Salman Rushdie’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 255–92. Aravamudan, Srinivas, ‘The Novels of Salman Rushdie: Mediated Reality as Fantasy’, World Literature Today, 63/1 (1989), 42–5. _____ ‘ ‘‘Being God’s Postman is no Fun, Yaar’’ ’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 187–208. Bader, Rudolf, ‘The Satanic Verses: An Intercultural Experiment by Salman Rushdie’, International Fiction Review, 19 (1992), 65–75. Balasubramanian, Radha, ‘The Similarities between Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margareta and Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses’, International Fiction Review, 22 (1995), 37–46. Bardolph, Jacqueline, ‘Language is Courage’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 209–20. Batty, Nancy E., ‘The Art of Suspense: Rushdie’s 1001 (Mid-)Nights’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 69–82. Bharucha, Rustom, ‘Rushdie’s Whale’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 159–72. Booker, M. Keith, ‘Beauty and the Beast: Dualism as Despotism in the Fiction of Salman Rushdie’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 237–54. Brennan, Timothy, ‘Shame’s Holy Book, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 109–22. Brigg, Peter, ‘Salman Rushdie’s Novels: The Disorder in Fantastic Order’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 173–86. Brouillette, Sarah, ‘Authorship as crisis in Salman Rushdie’s Fury’, Journal of Commonwealth Literature (40:1, 2005; 137–56). Cook, Rufus, ‘Place and Displacement in Salman Rushdie’s Work’, World Literature Today, 68/1 (1994), 23–8. Cronin, Richard, ‘The Indian English Novel: Kim and Midnight’s Children’, Modern Fiction Studies, 33/2 (1987), 201–13. Cundy, Catherine, ‘ ‘‘Rehearsing Voices’’: Salman Rushdie’s Grimus’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 45–54. Engblom, Philip, ‘A Multitude of Voices: Carnivalization and Dialogicality in the Novels of Salman Rushdie’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 295–305. Fischer, Michael M., and Abedi, Mehdi, ‘Bombay Talkies, the Word and the World: Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses’, Cultural Anthropology, 5/ 2 (1990), 107–59. Fletcher, M. D., ‘Rushdie’s Shame as Apologue’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 97–108. François, Pierre, ‘Salman Rushdie’s Philosophical Materialism in The 210 SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY Satanic Verses’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 305–20. Grewal, Inderpal, ‘Salman Rushdie: Marginality, Women, and Shame’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 123–44. Hawes, Clement, ‘Leading History by the Nose: The Turn to the Eighteenth Century in Midnight’s Children’, Modern Fiction Studies, 39/1 (1993), 147–68. Johansen, Ib, ‘The Flight from the Enchanter: Reflections on Salman Rushdie’s Grimus’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 23–34. Jones, Peter, ‘The Satanic Verses and the Politics of Identity’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 321–34. Jussawalla, Feroza, ‘Resurrecting the Prophet: the Case of Salman, the Otherwise’, Public Culture, 2/1 (1989), 106–17. _____ ‘Rushdie’s Dastan-e-Dilruba: The Satanic Verses as Rushdie’s Love Letter to Islam’, Diacritics, 26 (1996), 50–73. Kane, Jean, M., ‘The Migrant Intellectual and the Body of History: Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children’, Contemporary Literature, 37/1 (1996), 94–118. Merivale, Patricia, ‘Saleem Fathered by Oscar: Intertextual Strategies in Midnight’s Children and The Tin Drum’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 83–96. Moss, Laura, ‘‘‘Forget those damnfool realists!’’ Salman Rushdie’s SelfParody as the Magic Realist’s ‘‘Last Sigh’’’ Ariel: A Review of International English Literature (29:4, 1998; 121–39). Needham, Anuradha Dingwaney, ‘The Politics of Post-Colonial Identity in Salman Rushdie’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 145–58. Newell, Stephanie, ‘The Other God: Salman Rushdie’s ‘‘New’’ Aesthetic’, Literature in History, 3rd ser., 1/2 (1992), 67–87. Parameswaran, Uma, ‘New Dimensions Courtesy of the Whirling Demons: Word-Play in Grimus’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 35–44. Price, David, ‘Salman Rushdie’s ‘‘Use and Abuse of History’’ in Midnight’s Children’, Ariel, 25/2 (1994). Rhombes, N., Jr., ‘The Satanic Verses as Cinematic Narrative’, Literature/ Film Quarterly, 11/1 (1993), 47–53. Spivak, Gayatri, ‘Reading The Satanic Verses’, Public Culture, 2/1 (1989), 79–99. Suleri, Sara, ‘Contraband Histories: Salman Rushdie and the Embodiment of Blasphemy’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 221–36. Syed, Mujeebuddin, ‘Warped Mythologies in Salman Rushdie’s Grimus’, Ariel, 25/4 (1994), 135–52. _____ ‘Midnight’s Children and its Indian Con-Texts’, Journal of Commonwealth Literature, 29/2 (1994), 95–108. Wilson, Keith, ‘Midnight’s Children and Reader Responsibility’, in Fletcher (ed.), Reading Rushdie, 55–68. 211 SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY THE RUSHDIE AFFAIR Collections of essays, letters, and documents Appignanesi, Lisa, and Maitland, Sara (eds.), The Rushdie File (London: ICA/ Fourth Estate, 1989). Cohn-Sherbok, Dan (ed.), The Salman Rushdie Controversy in InterReligious Perspective (Lewiston, NY, and Lampeter: Edward Mellen, 1990). For Rushdie: Essays by Arab and Muslim Writers in Defense of Free Speech [no editor(s) identified] (New York: George Braziller, 1994). First published as Pour Rushdie: Cent intellectuels arabes et musulmans pour la liberté d’expression (Paris: Éditions la Découverte, 1993). Horton, John (ed.), Liberalism, Multiculturalism and Toleration (London: Macmillan, 1993). MacDonogh, Steven (ed.), in association with Article 19, The Rushdie Letters: Freedom to Speak, Freedom to Write (Dingle, Co. Derry: Brandon, 1993). This book includes a section ‘Fiction, Fact, and the Fatwa’ (pp. 125–83), an ongoing chronicle of events since the fatwa maintained by Carmel Bedford on behalf of the International Committee for the Defence of Salman Rushdie and his Publishers. Three reports relating to the issue have been published by the Commission for Racial Equality and the Inter-Faith Network of the United Kingdom. These are: Law, Blasphemy and the Multi-Faith Society: Seminar Report, ed. Simon Lee et al. (1990); Free Speech: Seminar Report, ed. Susan Mendus et al. (1990); Britain: A Plural Society, ed. Sebastian Poulter et al. (1990). The continuing series Contemporary Literary Criticism (Detroit: Gale) published two substantial entries on ‘The Satanic Verses Controversy’ in volumes for 1989 (pp. 214–63), and 1990 (pp. 404–56). See also the relevant sections in books by Alexander, Connor, Cornwell, Goonetilleke, Gurnah, Kundera, Spivak, Teverson and Wheale, listed above. Among journals to have dedicated special issues to the affair are: American Atheist, 31/9 (1989). Index on Censorship, 18/5 (May 89), and 19/4 (Apr. 90). Index on Censorship maintains a continuing watch on the affair in its regular feature ‘Index Index’, reviewing censorship issues and events worldwide. Public Culture, 2/1 (Fall 1989). Third Text, 11 (Summer 1990): ‘Beyond the Rushdie Affair’. See also: Tariq Modood, ‘British Asian Muslims and the Rushdie Affair’, Political Quarterly, 61/2 (Apr. 1990), 143–60. 212 SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY Relevant monographs include: Akhtar, Shabbir, Be Careful With Muhammad! The Salman Rushdie Affair (London: Bellew, 1989). Easterman, Daniel, New Jerusalems: Reflections on Islam, Fundamentalism, and the Rushdie Affair (London: Grafton, 1992). Kuortti, Joel, Place of the Sacred: The Rhetoric of the Satanic Verses Affair (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1997). Lee, Simon, The Cost of Free Speech (London: Faber, 1990). Pipes, Daniel, The Rushdie Affair: The Novel, The Ayatollah, and the West (New York: Carol/Birch Lane, 1990). Ruthven, Malise, A Satanic Affair: Salman Rushdie and the Rage of Islam (London: Chatto, 1990; republished as A Satanic Affair: Salman Rushdie and the Wrath of Islam, 1991). Sardar, Ziauddin, and Davies, Meryl Wyn, Distorted Imagination: Lessons from the Rushdie Affair (London: Grey Seal, 1990). Weatherby, William, J., Salman Rushdie: Sentenced to Death (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1990). Webster, Richard, A Brief History of Blasphemy: Liberalism, Censorship, and ‘The Satanic Verses’ (Southwold: Orwell, 1990). See also the relevant sections in books by Alexander, Connor, Cornwell, Goonetilleke, Kundera, Spivak, and Wheale, listed above. 213 Index Afzal-Khan, Fawzia, 86 Ahmad, Aijaz, 17, 18, 57, 182 Al-Azm, Sadik, 20, 24 Allen, Woody, 48 Allende, Isabelle, 18 Amis, Martin, 90 Anderson, Benedict, 6 Aravamudan, Srinivas, 20, 23, 83 Attar, Farid-ud-din, 20 Auden, W. H., 73 Augustine, St., 87 Austen, Jane, 61, 169 Bakhtin, Mikhail, 47 Ballard, J. G., 54 Bardolph, Jacqueline, 26 Barnes, Julian, 3 Barthes, Roland, 141 Baudrillard, Jean, 141 Baum, Frank, 100 Becket, Thomas, 87 Beckett, Samuel, 2, 23, 30, 32, 72, 75, 81, 84, 109, 114, 173 Beethoven, Ludwig van, 145 Bell, Steve, 57 Bellow, Saul, 10 Benjamin, Walter, 106, 122 Bhabha, Homi, 6, 60, 120 Bharucha, Rustom, 24, 26 Bhutto, Zulfikar Ali, 18, 59 Blake, William, 5, 7, 23, 29, 35, 72, 81, 83, 84, 95, 125, 139 Blyton, Enid, 127 Boabdil, King, 108, 109 Bono, 133, 144 Booker, Keith, 57 Borges, Jorge Luis, 96 Bragg, Melvyn, 90 Brennan, Timothy, 16–17, 18, 20, 29, 41, 50, 57, 63, 68, 182 Brigg, Peter, 22 Brouillette, Sarah, 151 Buchner, Georg, 68 Bulgakov, Mikhail, 23, 72, 84 Bunyan, John, 31 Buñuel, Luis, 49 Butler, Samuel, 5 Calvino, Italo, 3 Capriolo, Ettore, 89 Cervantes, Miguel de, 23, 25 Charles I, 73 Christ, 83, 111, 114, 171 Coleridge, S. T., 2, 7, 15, 29, 95, 139, 154 Concilio, Carmen, 146 Connor, Steven, 6, 13, 51, 75, 83 Conrad, Joseph, 24, 49, 54, 91, 177 Cortazar, Julio, 40 Craigie, Jill, 178 Cundy, Catherine, 21, 22, 57, 107 Cunningham, Valentine, 149 Dali, Salvador, 119 Dante Alighieri, 29, 33, 72, 78 Davies, Meryl Wyn, 9 Defoe, Daniel, 23, 84 Desani, G. V., 25–6 Diana, Princess of Wales, 139, 140, 142 Dickens, Charles, 23, 24, 28, 48, 72, 148, 160, 166 Disney, Walt, 145 214 INDEX Doria, Andrea, 168, 169, 171, 172 Eco, Umberto, 3 Einstein, Albert, 5 Enright, D. J., 12 Eliot, T. S., 80 Herr, Michael, 10 Hesse, Hermann, 29 Hitchens, Christopher, 124 Homer, 31, 129 Hughes, Ted, 23, 29, 84 Igarashi, Hitoshi, 89 Fanon, Frantz, 18 Fenton, James, 94 Fielding, Henry, 15, 23, 27, 120 Fonda, Jane, 137 Forster, E M, 145 Foucault, Michel, 141 Fowles, John, 80 Freud, Sigmund, 5, 77, 180 Fuentes, Carlos, 8, 18, 25 da Gama, Vasco, 73, 108, 110 de Gaulle, Général Charles, 165 Gandhi, Indira, 22, 41, 52, 55, 102, 110, 120, 134 Gandhi, Mahatma, 42 Gandhi, Rajiv, 105 Gandhi, Sanjay, 111 Garland, Judy, 103 Gasiorek, Andrzej, 41, 42, 50 Gilliam, Terry, 4, 5 Gluck, Christophe, 127 Gogol, Nikolai, 25 Gopal, Priyamvada, 125 Gordimer, Nadine, 90 Gorra, Michael, 20 Gramsci, Antonio, 17, 18 Grass, Günther, 23, 25, 90 Greene, Graham, 3 Grierson, John, 178 le Guin, Ursula, 162 Grewal, Inderpal, 21 Hardy, Thomas, 162 Harris, Wilson, 2, 4, 6 Harrison, James, 19, 26, 57 Harrison, Tony, 66 Hawthorne, Nathanael, 130 Hayden, Tom, 137 Heaney, Seamus, 90, 149 Hemingway, Ernest, 91 Henry II, 87 James, Henry, 2, 69, 109, 184 Johansen, Ib, 22 John, Elton, 139 Johnson, Samuel, 2, 155 Jonson, Ben, 148 Joyce, James, 23, 25, 27, 34, 43, 49, 72, 77, 86, 87, 91, 113, 114, 127, 153, 171 Kafka, Franz, 5, 23, 25, 30 Keats, John, 115, 118, 135, 145 Kennedy, J. F., 3, 105, 134 Khan, Ayub, 59 Khomeini, Ayatollah Ruhollah, 74, 88 Kipling, Rudyard, 48, 69 Kubrick, Stanley, 151 Kundera, Milan, 17, 20, 25, 91 bin Laden, Osama, 147 Lakshmi, Padma, 123, 124, 125, 150, 151, 169 Lawrence, D. H., 14, 72, 91, 127 Lee, Simon, 91–3 Leithauser, Brad, 19 Lennon, John, 128, 138, 142 Levi, Primo, 80 Locke, John, 5 Lodge, David, 26 Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth, 136 Lucian, 78 Macchiavelli, Niccolò, 166, 167 Machado de Assis, 25 Mahfouz, Naguib, 89 Mailer, Norman, 138 Mann, Thomas, 145 Marquez, Gabriel Garcia, 3, 16, 23 215 INDEX The Jaguar Smile, 6–8, 124 Luka and the Fire of Life, 125, 179–81 Midnight’s Children, 7, 9, 11, 13, 14, 16, 19, 21–4, 26–7, 36, 38–56, 57–8, 60, 63, 67, 72, 95, 99, 107, 110–12, 120, 125, 130, 135, 139, 142, 149, 175, 182, 183 The Moor’s Last Sigh, 13, 48, 63, 65, 107–22, 143, 146, 175, 176 The Satanic Verses, 3, 8, 9, 12, 14, 19–22, 24, 34, 37, 47–8, 59, 63, 70, 71–93, 98, 107, 113, 119, 121, 135, 136, 142, 144, 149, 156, 175, 177 Shalimar the Clown, 124, 158– 66, 176, 178, 183 Shame, 12, 17, 21–2, 26, 57–70, 112, 162, 175 Step Across This Line, 124 Rushdie, Zafar, 94, 123, 125 Ruthven, Malise, 19, 57, 92 Marx, Karl, 5 de Medici, Giuliano, 170 de Medici, Lorenzo, 170 Melville, Herman, 25 Merivale, Patricia, 23 Morris, William, 7 Mountbatten, 1st Earl, 108 Naipaul, V. S., 10 Nandy, Ashis, 24 Needham, Anuradha Dingwaney, 22 Nehru, Jawaharlal, 120, 134 Newell, Mike, 33 Newell, Stephanie, 20–1 Nygaard, Wilhelm, 89 Okri, Ben, 8 Ono, Yoko, 138 Ortez, Daniel, 6 Orwell, George, 91 Parameswaran, Uma, 23 Parker, Jesse Garron (Elvis Presley), 131 Parnell, Tim, 19 Powell, Enoch, 105 Proust, Marcel, 148 Pynchon, Thomas, 3 Rabelais, Francois, 20 Robinson, William Heath, 180 Rushdie, Milan, 124, 125, 179, 184 Rushdie, Salman East, West, 12, 100–06, 117, 175–6 The Enchantress of Florence, 125, 166–74, 176, 177 Fury, 123, 124, 150–8, 173, 178 Grimus, 11, 13, 21–4, 27–37, 61, 63, 135, 175 The Ground Beneath her Feet, 123, 124, 126–46, 148, 149, 175, 177, 183 Haroun and the Sea of Stories, 12, 18, 94–99, 106, 125, 175, 178 Said, Edward, 8, 90 Sandino, Augusto, 7 Sardar, Ziauddin, 9 Scorsese, Martin, 20 Scott, Walter, 38, 183 Shakespeare, William, 38, 64, 69– 70, 72, 80, 106, 111, 115, 119, 143, 145, 160 Shelley, P. B., 1, 7, 118, 175 Shelley, Mary, 26 Sidney, Sir Philip, 47 Smollett, Tobias, 120 Somoza, 6, 7 Spielberg, Steven, 29 Spivak, Gayatri, 19 St Exupéry, Antoine de, 164 Stoppard, Tom, 90 Sterne, Laurence, 2, 5, 15, 17, 23, 39, 51, 54, 76, 172 Stevens, Wallace, 4 Stevenson, R. L., 81 Suleri, Sara, 23–4 Sutherland, John, 124 216 INDEX Swift, Jonathan, 1–2, 5, 17, 20, 23, 29, 54, 67, 99, 114, 137, 151, 156, 162 Tagore, Rabindranath, 8 Tennyson, Alfred Lord, 34 Teverson, Andrew, 183 Thatcher, Margaret, 78 Tolkien, J. R. R., 5, 127 Turner, Ted, 137 Vespucci, Amerigo, 167 Victoria, Queen, 42 Virgil, 72, 78, 127, 139 Vlad the Impaler, 168 Vonnegut, Kurt, 31 Walcott, Derek, 90 Webster, Richard, 9, 92 Wedgwood, C. V., 7 West, Elizabeth, 124 Wilde, Oscar, 18 Wilson, Keith, 19, 23, 42 Winters, Yvor, 148 Wood, James, 126, 184 Wordsworth, William, 47 Woolf, Virginia, 5, 28, 43 Wright, Richard, 5 Yeats, W. B., 7, 23, 139, 149, 153 Zia Ul-Haq, General Mohammed, 18, 42 Zola, Emile, 2 217